Abstract

Background

Pregnancy loss is a common event but its significance is often minimized by family, friends, and community, leaving bereaved parents with unmet need for support. This study sought to describe demographics, usage patterns, and perceived benefits for women participating in internet pregnancy loss support groups.

Methods

We requested permission to post an anonymous internet survey on large and active United States internet message boards for women with miscarriages and stillbirths. The study purposefully oversampled stillbirth sites and included both closed and open-ended questions. The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board approved the study. Closed-ended questions were summarized and evaluated with bivariable analysis. We performed a qualitative analysis of open-ended data using an iterative coding process to identify key themes.

Results

Of 62 sites queried, 15 granted permission to post the survey on 18 different message boards. We collected 1039 surveys of which 1006 were complete and eligible for analysis. Women were typically white, well-educated, and frequent users. They noted message boards helped them feel less isolated in their loss and grief and they appreciated unique aspects of internet communication such as convenience, access, anonymity, and privacy. Pregnancy loss message boards are an important aspect of support for many bereaved mothers. African-Americans women appear to be substantially underrepresented on-line despite being at higher risk for stillbirth.

Conclusions

Internet message boards serve a unique function in providing support for women with miscarriage and stillbirth and the benefits are often significantly different from those encountered in traditional face-to-face bereavement support.

Introduction

Pregnancy loss is a common event in the United States with approximately 15% of recognized pregnancies ending in miscarriage (loss in the first half of pregnancy) and another 1% ending in stillbirth (loss in the second half of pregnancy) (Gabbe, Niebyl, & Simpson, 2002; NCHS, 2007). Many parents cope well with loss, but some struggle with subsequent anxiety, depression, trauma, and prolonged grief (Vance, Boyle, Najman, Thearle, 2002; Mann, McKeown, Bacon, Vesselinov, & Bush, 2008; Lok and Neugebauer 2007). While a loss is often devastating to a bereaved mother, such losses are frequently minimized or unacknowledged by friends, families, and communities, leaving parents with greater need for support than others may recognize (Leon, 2009). In addition, women often feel a stigma with pregnancy loss, other people may be uncomfortable talking about death. Parents may encounter few people in their daily life who have sustained a similar loss.

Face-to-face support groups for parents who have experienced pregnancy loss are perceived by participants to be valuable sources of support (Côté-Arsenault & Freije, 2004; Cacciatore, 2007). More recently, internet support groups have offered a novel mechanism for social and emotional support by connecting participants through on-line “message boards,” also referred to as on-line “groups,” “forums,” or “communities.” Such groups have proliferated in the last decade, and exist for virtually every imaginable health issue. A recent search of the Google groups category turned up more than 33,000 groups in the health category (www.google.com).

Despite the large number of support sites available, little research has described typical usage or user characteristics and the role of the boards in grief support, generally, or in pregnancy loss, specifically. A systematic review from 2004 identified 37 studies of peer-to-peer communities of all types (Eysenbach, Powell, Englesakis, Rizo, & Stern, 2004). Studies on depression and social support showed mixed results with some trials demonstrating significant improvements some showing no benefit. A recent review of on-line groups specific to cancer support noted positive psychosocial benefits from the groups (Hoey, Ieropoli, White & Jefford, 2008). Qualitative studies have examined the culture of on-line perinatal loss groups and have noted a strong sense of community and support. (Capitulo 2004; Herrmann-Traulsen & Götz, 2006).

There are no large studies detailing the demographics, use, and perceptions of mothers using on-line pregnancy or infant loss groups. It is unknown whether board participants reflect the demographic population of women with pregnancy loss or women using online health sites generally, their preferences about board structure, and what aspects of the message boards women perceive as most helpful. This study used both quantitative and qualitative approaches to understand perceived benefits for a sample of women who utilize on-line pregnancy loss support groups.

Methods

An on-line internet survey to evaluate use of internet pregnancy loss sites by women was developed and pilot tested among bereaved mothers and the internet site was pilot tested by research assistants. The 57-question survey was presented over 14 screens; participants could go back to change answers and the only mandatory asked about gender. We collected demographic information as well as preferences about message board structure, use, and experiences. Questions were designed to identify general use of the internet, attitudes and experiences with pregnancy loss message boards, social support, and depression. One open-ended question asked: “For you, what do you think is the most helpful thing about internet pregnancy loss support sites?” We searched for potential message boards on which to post the voluntary survey by referencing lists provided on popular internet information sites for pregnancy loss (many of which provided general grief information but no interactive message board) and by doing internet searches using Yahoo.com and Google.com in order to identify the largest and most active boards. Sixty-two potential sites with pregnancy loss message boards were identified which met our criteria: being primarily U.S.-based and having large and active message boards (defined as having multiple postings per day). As we had a particular interest in use of the boards by women with later losses (stillbirths at or after 20 weeks gestational age), we only included sites which served women with stillbirth only or women with either stillbirth or miscarriage (rather than sites limited to miscarriages). We did not post on sites which required individuals to provide details about a specific loss in order to obtain a sign-on for participation.

We queried the 62 eligible sites asking permission to post a link to the survey. We posted an on-going link to the survey for up to four months if permitted by the participating message board administrator. If on-going posting was not permitted, we posted the link to the survey twice (one month apart) in a message on the board. We kept the entire survey open until we gathered a minimum of 1000 responses to ensure an adequate range of experiences. The survey was anonymous and did not collect IP addresses, cookies, or referring site in order to protect confidentiality. At the end of the survey we asked if users would be interested in follow-up surveys and collected email addresses from those who volunteered. There was no incentive for participation. The survey was maintained on Surveymonkey.com and data was electronically recorded on that site. The study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and by all participating internet sites on which it was posted. The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) was used to guide reporting of the methods and results of this study (Eysenbach, 2004).

We performed summary descriptive analysis on the quantitative data and used bivariable analysis to look at answers among subgroups. Information from the open-ended question was separately reviewed and coded using a qualitative approach. Three authors reviewed the comments independently and met to develop preliminary codes which were documented in a qualitative codebook. Two reviewers (--- and ---) applied these codes to a subset of the data and repeated this process through several iterations until agreement was reached on 19 final codes and their definitions (Table 2). Using the finalized codebook, both reviewers then separately coded all 775 comments. Each comment was tagged with all relevant codes so that more than one code could be applied to a single comment. When there was dissent, a third author (---) provided a recommendation and the first two reviewers discussed this suggestion and decided upon the final coding by consensus. We met regularly to review coding and to identify and discuss emerging themes from the data. We verified these themes by going back to the data and exploring it repeatedly to look for disconfirming evidence. The two independent reviewers had an 84% initial match rate overall in applying the 19 codes to the sample. Kappa scores were calculated for each code to evaluate inter-reviewer agreement; of 19 codes, 8 had kappa scores of 0.9 or higher, 6 had scores between 0.8 and 0.899, and 5 had kappa scores between 0.7 and 0.799.

Table 2. Themes and codes for qualitative analysis (n=775).

More than one code could be used for each comment. Four additional codes were used but are not listed here as they were systematically assessed in the quantitative part of the survey and infrequently mentioned in the comments: stillbirth, infant death, termination, loss beyond the first year.

| Code | Theme | Comments with code | n | 2-coder Kappa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: “I’m not alone” | ||||

| A | I’m not alone/others with similar experiences | 78% | 601 | 0.867 |

| B | Support, friendship, community | 16% | 121 | 0.820 |

| C | Enjoy sharing and reading other people’s stories | 12% | 95 | 0.883 |

| Theme 2: Validation and Safety | ||||

| D | Validating environment, normalizes grief | 13% | 100 | 0.922 |

| E | Non-judgmental, people share true feelings | 11% | 82 | 0.806 |

| F | Private and anonymous | 5% | 36 | 0.924 |

| Theme 3: Internet Ease and Convenience | ||||

| G | Access to people not available in “real” life | 10% | 75 | 0.737 |

| H | Physically accessible and convenient | 8% | 63 | 0.956 |

| I | Easier to communicate on internet | 6% | 47 | 0.911 |

| J | Therapeutic to write | 5% | 38 | 0.730 |

| Theme 4: Moving Forward | ||||

| K | Learning how I and others can cope and grieve and knowing other people got through | 9% | 67 | 0.798 |

| L | Gaining hope from subsequent pregnancy success stories | 3% | 26 | 0.871 |

| M | Like being able to help others | 3% | 23 | 0.906 |

| N | Learning new information | 6% | 50 | 0.853 |

| O | Knowing others that have it worse than me | 1% | 6 | 0.799 |

Results

After multiple queries to each of the 62 eligible boards, 15 sites agreed to post a link to the survey on a total of 18 message boards (some had separate pages for different sub-topics related to pregnancy loss). Among the sites not posting the survey, most were boards which did not respond to repeated emails, had specific prohibitions against conducting research on their sites, or had been discontinued or were no longer active. The final set of 18 boards included twelve general sites for women with miscarriage and stillbirth, two boards for women pregnant or trying to conceive after a loss, one board for women with recurrent losses, one board for women with elective termination of pregnancy, one board for women with loss due to a common medical cause, a board for bereaved teens after pregnancy loss, and one blog site which was considered similar to a message board as it included extensive response and discussion. The final set represented a broad snapshot of available pregnancy loss internet groups with oversampling for boards geared toward women with stillbirth. We chose to include women with termination of pregnancy because many of the issues of loss and bereavement are common to all women with pregnancy loss, whether or not they made a choice to terminate the pregnancy electively or due to medical complications.

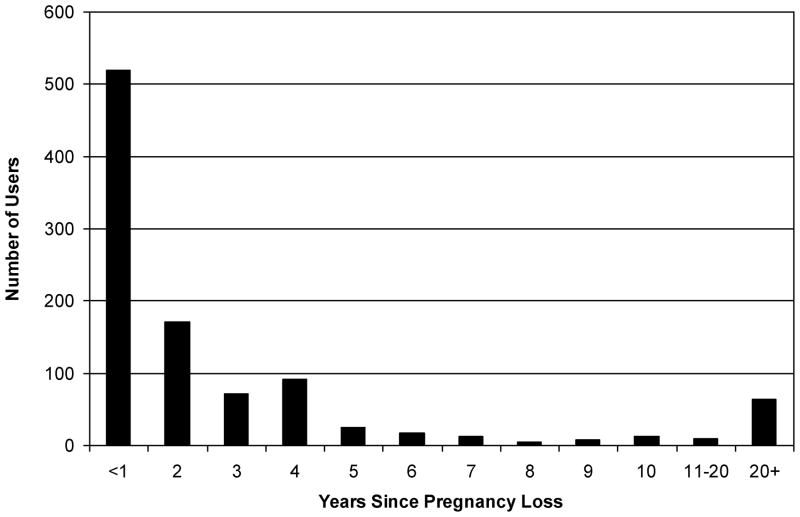

Over an 8-month period from November 2008 to June 2009, 1039 users entered the internet survey site and 1007 completed the survey. One completed survey was eliminated as most of the responses were inconsistent or nonsensical leaving a total usable sample of 1006. Demographics of participating users are described in Table 1. Most respondents lived in the United States and identified English as their first language, but 18 countries total were represented. Respondents were overwhelmingly white, well-educated, and well-insured, and these numbers changed very little whether we examined the full set of respondents or limited to respondents living in the United States. More than half of losses reported (54%) were stillbirths or losses after 20 weeks gestation age with the other 46% being miscarriages or losses before 20 weeks. Only half of women were in the first year after their loss, and the rest had losses ranging from one year to decades prior. (Figure 1.) While women with miscarriages and stillbirths were similar in terms of demographics, women with miscarriage were significantly more likely to be in the first year out from their loss (mean 59% versus 48%, p<0.0005). Most women reported posting on the board frequently (53% once a week or more) and few (8%) reported they had never written a message for a board. 262 mothers (26%) reported they were told the baby might not survive because of a medical condition OR that they were aware that the baby would not survive because they were terminating the pregnancy. We did not separately ask how many respondents had electively terminated their pregnancy although some women volunteered this information in their comments. As this was an anonymous survey, we did not track which web page the subject used to enter our survey.

Table 1.

Demographics of Survey Respondents (Users of Pregnancy Loss Message Boards) (n=1006)

| Number (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | Median: 32 (range 15–71) | |

| Country of Origin | ||

| • United States | 886 (88) | |

| • Canada | 51 (5) | |

| • U.K and Europe | 28 (3) | |

| • Other (12 countries) | 37 (4) | |

| English is First Language | 953 (95) | |

| Race | • White | 929 (92) |

| • Black | 19 (2) | |

| • Asian | 22 (2) | |

| • Native American/Alaskan Native | 8 (1) | |

| • Missing | 28 (3) | |

| Education | • High school or less | 93 (9) |

| • At least some college | 899 (91) | |

| Currently Pregnant | 164 (16) | |

| Loss Type | • Miscarriage | 427 (46) |

| • Stillbirth | 499 (54) | |

| Access to home internet | 911 (91) | |

Figure 1.

Time Since Pregnancy Loss Among Message Board Users

In general, women expressed great satisfaction with the pregnancy loss boards in terms of learning new information and endorsing the board for others with a loss. Since boards vary widely in terms of how they function and whether or not they are moderated, we queried women about their preferences. 75% of women (n=681 of 909 responding) agreed or strongly agreed that boards should have a leader, moderator, or facilitator. 89% (n=806 of 907) agreed or strongly agreed a professional health worker should participate on the boards and 86% (n=774 of 905) felt similarly about a mental health professional participating. Presence or absence of health professionals on the site may be an important question since 82% (n=761 out of 908 who responded to this question) reported they had learned new medical information from the board.

While feeling more safe or secure on-line emerged as an important theme in the qualitative data, the quantitative questions revealed conflicting results Twenty-seven percent of respondents reported that they agreed or strongly agreed with the statement: “I worry about whether someone could identify me from my messages.” But in contrast, 34% of women reported they had disclosed personal information such as a full name, street address, or email to other members on a message board.

775 participants provided a response to the open-ended question about most helpful aspects of internet groups. Table 2 lists the final codes, the number and percent of comments and individual kappa scores for coders. From the data and these codes, four recurrent themes characterized women’s perceptions of the benefits of on-line message boards.

Theme 1: “I’m not alone”

By far, the most common theme identified was that the message boards helped mothers recognize they were not alone in their loss and grief. In fact, 78% (n=601) of participants referred to the idea that internet support groups helped women realize they were not alone, and that other parents had been there and had similar experiences and emotions (Code A). Many of the women noted that they felt only someone who had been through the experience of losing a baby could really understand what it felt like. As one respondent described,

“The fact that I am not the only one this has happened to and that I am not alone in this horrible nightmare.”

Women also described a strong sense of support, comfort, and community from the message boards. Women identified peers on the support group as friends and people who were like family, and reported a sense of close community with others they had met on-line (Code B). A small number of women even reported meeting people in-person whom they had first encountered via the on-line support group. Women also noted enjoyment in sharing their own stories and reading those of other parents (Code C)

Theme 2: Validation and Safety

Another common theme was that the boards were a validating environment where it was acceptable to talk about a deceased baby and where grief could be normalized (Code D). A number of women discussed feeling like the boards helped them understand that their emotions, that grief reactions were normal and common, and that the sadness might last for a long time.

“I felt like I was crazy with the things that were going through my head and the women that had more time dealing with a loss told me that it was normal and gave me a heads up on some things to expect.”

Participants also felt validated by having a site to talk openly about their babies and their birth experiences since in real life this often led to awkward or uncomfortable situations. On-line it was safe to talk about their pregnancies and infants and even when it was perceived as socially unacceptable off-line. Women noted that they had a need to tell their stories and that internet support sites were one of the few or only places they could freely discuss this information. As one women remarked,

“Being able to talk openly about my babies (twin girls) without people looking at me like I m crazy… To my family and most friends, the twins have been gone for nearly a year and are entirely a subject for the past.”

Another wrote,

“Sharing baby stuff--women who have not gone through a stillbirth don t want to hear about my birth, or what my daughter looked like, or anything about my experience.”

The internet was also seen as different from in-person groups or interactions because people could feel free to post their true feelings and have a non-judgmental audience. This was often linked with the themes of privacy and anonymity, particularly for women who had terminated a pregnancy due to fetal anomaly or maternal health (Codes E, F).

“I had to terminate my pregnancy for due (sic) to medical issues that were harmful to both the baby and me. This is not the sort of thing one brings up casually and it is safer and easier to find people with similar experiences via the internet than it is locally.”

Theme 3: Internet Ease and Convenience

Multiple codes (Codes G, H, I, J) reflected aspects of the internet which are different from the type of help women might receive in person or in local support groups. These included the convenience and physical ease of being able to use the internet from home or work any time, day or night and the sense of privacy and confidentiality.

“It is accessible, and you can receive feedback, 24 hours a day, seven days a week. My support group met only twice a month.”

“The anonymity and fact that you aren t alone. Also the instant access. You don t have to wait for a date for a live meeting. You can post at 2am if needed.”

“… I like the fact that I can communicate with these people (my friends) in the privacy of my own home and don t have to get dressed up to meet with people who understand. Because sometimes you just have those days where you don t feel like getting out of your pj s and those are usually the days when the ladies on the forum help me get moving and on with life.”

Women with stillbirth frequently commented that they hadn’t met anyone in their “real life” with a late loss. Other women reported that they lived in rural areas and didn’t have access to support groups or services in the area where they resided.

An interesting finding was the frequent reflection that writing and posting on a message board was sometimes an easier way to communicate on emotional subjects. Multiple women noted that they felt more comfortable on the message board because people could not see them if they were upset or crying and that the board format gave them time and space to compose their thoughts if they became emotional.

“I cry when I talk to a real person so it was easier to talk to someone online, less emotional.”

“I like the fact that you can talk without the pitying stares one can get face to face.”

Theme 4: Moving forward

A smaller number of users raised issues related to hope and coping skills learned from the message board (Codes K, L, M, N, O). For example, women discussed ways in which the internet message boards provided reassurance that they could survive their grief because other people had done so or that others like them were able to have good pregnancy outcomes in the future. Participants also commented that the internet was valuable because they learned new information about medical conditions, learned more about how to manage labor, delivery, and postpartum concerns after a loss, and gathered ideas from others about how to memorialize their baby. A minor theme which several women brought up was the idea that they could put their loss in some perspective from knowing others had more difficult situations than they had experienced.

Discussion

This study provides a snapshot view of women using internet pregnancy loss message boards and suggests users differ dramatically from the epidemiological distribution of women with pregnancy loss. First, the racial distribution on-line is much different than one would expect based either on the distribution of pregnancy loss or the distribution of internet users overall. Researchers have estimated that 75% of whites and 59% of African-Americans in the United States are on-line, so it would not be surprising to find slight overrepresentation of whites in our survey (Fox & Vitak, 2008). Since African-American women have twice the risk of stillbirth compared with white women, and our study was designed to over-sample women with stillbirth (54% of respondents) we would expect a fairly high number of African-American users on line based on epidemiologic data alone (CDC, 2005). Our finding that only 2% of women on this diverse set of internet boards were African-American is astounding.

Although most psychosocial research on perinatal grief has focused on white women, a few studies on African-American women suggest comparable grief experiences to whites including similar need for and voids in social support after a loss (Kavanaugh & Hershberger, 2005; Van & Meleis, 2003). The lack of African-American users on pregnancy loss message boards does raise questions not only about access but about whether preferences for types of bereavement support vary by race, and whether non-white users feel comfortable participating in message boards primarily populated by white users. Studies of online support groups typically report very low levels of participation by African-Americans for reasons which are not entirely understood (Fox & Vitak, 2008; Bacon, Condon & Fernsler, 2000; Miller, West, and Wasserman, 2007). Although no site that we studied listed race as part of the person’s profile, some allowed users to post avatars, a photos or cartoon representations of themselves, which frequently suggest an individual’s race or ethnicity. In addition, since African-Americans also have been noted to have more distrust of medical research, this could have reduced response rates to this research survey by this group (Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 2003).

Our participants represented a surprisingly well-educated population, with 91% reporting more than a high school education. This is in contrast to a nationwide survey of women reporting a single pregnancy loss, in which just 52% overall reported having more than a high school education (Price, 2006). However, this may be more reflective of internet use than pregnancy loss since a recent U.S. study noted 71% of users of internet health sites had more than a high school education (Atkinson, Saperstein & Pleis, 2009).).

Parents in our study endorsed internet support groups because they served to reduce isolation and demonstrated that mothers were not alone in their grief. The death of a child is uncommon, outside of the “natural order” of life, and is often shocking news. Many people minimize the impact of an early miscarriage despite the fact that parents can have profound and disabling grief and depression responses to such losses (Lok and Neugebauer). Friends and family who hear of these losses may not know what to say and may avoid the topic entirely which unfortunately leaves parents feeling more stigmatized and isolated (Leon, 2009; Field & Behrman, 2003). For perinatal losses, networks on the internet may fill critical gaps in social support for bereaved parents.

Women also noted that the internet is particularly well-suited for individuals who wish to anonymously discuss personal topics and is convenient and accessible. Although a minority of participants expressed concerns about privacy on-line, a larger percentage reported they had already disclosed personal information on internet message boards. In the qualitative analysis, an important theme emerged about anonymity and privacy of the internet helped many women feel safer discussing difficult or sensitive issues. Respondents also noted on-line support is sometimes less threatening than face-to-face support. For example, women liked having the time to compose their thoughts when they were feeling emotional, liked writing and “venting” as a way to express their ideas, and reported that they could post to a computer screen without feeling immediately judged by others. Pregnancy loss and bereavement are socially awkward topics for most people, and internet support groups may create a safe haven for people sensitive to the stigma or judgments encountered in face-to-face social situations.

Our finding that internet support group users overwhelmingly preferred to have a group moderator or facilitator and that they would support the inclusion of leaders with mental or physical health training is an important finding for current and future groups. The fact that so many women learned new medical information from the message board would imply that a moderator with some medical knowledge of pregnancy loss could be helpful to make sure accurate information is transmitted.

Finally, we were surprised to find that only half of respondents on-line were in their first year of bereavement and a significant proportion were 5, 10, 20, or even more years out from their loss. This was particularly true for women with stillbirths compared with miscarriages. Pregnancy loss can have profound and lasting effects, and a significant portion of mothers may have need for continued support lasting far past the first few weeks or months after loss.

The study has several limitations inherent in surveying existing internet sites. Since we could not identify who did and did not respond to the survey, we acknowledge that the convenience sample is not necessarily representative of all users and certainly does not reflect representative views of all women with pregnancy loss. Due to the substantial difficulty in obtaining permission from many sites and specific prohibitions against research participation on other sites, we were restricted from posting on many boards. In addition, unless a researcher has access to the log-on data from each site (which sites do not generally share), it is impossible to identify a random or even representative sample of users, and we had to rely on voluntary participation in the survey. All of these limitations introduce the possibility of respondent bias toward subgroups of women who use these particular 18 boards, sites which had a continuous posting rather than an intermittent posting, respondents who have strong feelings about the use of message boards, or frequent board users. These are all well-recognized limitations of internet survey research (van Selm & Jankowski, 2006).

To address these potential risks for bias, we tried to post on a broad variety of message boards, collect a large sample, and oversample women with stillbirth since the needs of women with early and later losses may differ. It is impossible to verify user identify or accuracy of responses, so theoretically a participant could make up survey answers or falsely pretend to be a bereaved mother. However, there was no incentive for completing the survey, so there was little gain for providing false responses. We identified only one survey where the answers appeared widely inconsistent and suggested fraudulent response. We recognize that we cannot assess true prevalence of use by individuals in different sociodemographic groups through a voluntary internet survey but given that half of reported losses were stillbirths, we believe the lack of African-American women responding to the survey to be of significant concern and a true finding. We are conducting a second study using questions from this survey to assess attitudes of bereaved mothers who attend in-person support groups; we will report on the similarities and differences between women seeking on-line versus in-person support groups in a future manuscript.

Bereaved mothers using pregnancy loss message boards on-line describe multiple benefits associated with using these sites. However, since this was not a randomized sample, it is impossible to determine from this data whether internet sites could serve as effective sources for intervention with bereaved parents to address issues such as social isolation or depression. The qualitative data we garnered suggests specific elements of on-line support which are unique to the internet and which might be utilized to assist parents, particularly those with more rare types of losses. We are currently conducting a similar study with a convenience sample of bereaved parents who attend in-person support groups in order to compare differences in user characteristics between internet and in-person support group users. We are particularly interested in whether these groups are similar in terms of demographic factors and level of depressive symptoms. We will report on those comparisons once the second study is complete.

In summary, this is the largest study to characterize users of internet message boards for pregnancy loss and demonstrates a significant disparity between the population of women with loss and those on-line who responded to our survey. The study suggests an important gap in virtual support for bereaved African-American parents, and additional research should explore the reasons for lack of participation. The possibility that message boards may offer long-term support to bereaved parents for years after a loss, particularly for women with stillbirth, is a new finding worth further exploration; such losses may be more profound and long-lasting for parents than currently recognized by health professionals. Internet message boards offer an attractive source of free, anonymous, and immediate peer support and feedback for bereaved parents and can potentially reach large populations of parents who might not use traditional services. The potential to use on-line support as part of structured perinatal grief bereavement programs is attractive, and the next step will be to develop high-quality randomized, controlled trials to evaluate such interventions. Our data may serve helpful to bereavement support sites to describe the population currently using these boards and their preferences about group moderation and participation.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study was supported by the University of Michigan Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology with salary support for Dr. Gold provided by an NIH K-12 BIRCWH grant (Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health). Funders had no role in study design, data collection or analysis, or interpretation of results. Dr. Gold had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Katherine J. Gold, Department of Family Medicine, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, University of Michigan.

Martha E. Boggs, Department of Family Medicine, University of Michigan.

Emeline Mugisha, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, University of Michigan.

Christie Lancaster Palladino, Education Discovery Institute, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Georgia Health Sciences University.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Atkinson NL, Saperstein SL, Pleis J. Using the internet for health-related activities: findings from a national probability sample. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11(1):e4. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon ES, Condon EH, Fernsler JI. Young widows’ experience with an internet self-help group. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2000;38(7):24–33. doi: 10.3928/0279-3695-20000701-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciatore J. Effects of support groups on post traumatic stress responses in women experiencing stillbirth. OMEGA. 2007;55(1):71–90. doi: 10.2190/M447-1X11-6566-8042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitulo KL. Perinatal grief online. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2004;29(5):305–11. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200409000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Infant Mortality—United States, 1995–2002. MMWR. 2005;54(22):553–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté-Arsenault D, Freije MM. Support groups helping women through pregnancies after loss. West J Nurs Res. 2004;26(6):650–70. doi: 10.1177/0193945904265817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet e-surveys (CHERRIES) J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):e34. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach G, Powell J, Englesakis M, Rizo C, Stern A. Health related virtual communities and electronic support groups: systematic review of the effects of online peer to peer interactions. BMJ. 2004;328(7449):1166. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7449.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field MJ, Behrman RE, editors. Committee on Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families, Board on Health Sciences Policy. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2003. When Children Die: Improving Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and their Families. [Google Scholar]

- Fogel J, Ribisl KM, Morgan PD, Humphreys K, Lyons EJ. The underrepresentation of African Americans in online cancer support groups. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(6):705–12. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31346-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox S, Vitak J. Degrees of Access. Pew Internet and American Life Project; 2008. [Accessed 9-15-09]. at http://www.pewinternet.org/Presentations/2008/Degrees-of-Access-(May-2008-data).aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL. Obstetrics: normal & problem pregnancies. 4. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann-Traulsen C, Götz T. Study of virtual self-help groups after prenatal loss: not being alone in the grief process(German) Pflege. 2006;59(7):418–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoey LM, Ieropoli SC, White VM, Jefford M. Systematic review of peer-support programs for people with cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70:315–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanaugh K, Hershberger P. Perinatal loss in low-income African American parents. JOGNN. 2005;34:595–605. doi: 10.1177/0884217505280000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon I. Helping Families Cope with Perinatal Loss. [Accessed 9-15-09];Glob Libr Women’s Med. at http://www.glowm.com/index.html?p=glowm.cml/section_view&articleid=417.

- Lok IH, Neugebauer R. Psychological morbidity following miscarriage. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;21(2):229–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JR, McKeown RE, Bacon J, Vesselinov R, Bush F. Predicting depressive symptoms and grief after pregnancy loss. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2008;29(4):274–9. doi: 10.1080/01674820802015366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EA, West DM, Wasserman M. Health information websites: characteristics of U.S. users by race and ethnicity. J Telemed Telecare. 2007;13(6):298–302. doi: 10.1258/135763307781644852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2007. Hyattsville, MD: 2007. [Accessed 10-16-09]. at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus07.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Price SK. Prevalence and correlates of pregnancy loss history in a national sample of children and families. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10(6):489–500. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van P, Meleis AI. Coping with grief after involuntary pregnancy loss: perspectives of African American women. JOGNN. 2003;32:28–39. doi: 10.1177/0884217502239798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Selm M, Jankowski NW. Conducting online surveys. Qual Quant. 2006;40:435–56. [Google Scholar]

- Vance JC, Boyle FM, Najman JM, Thearle MJ. Couple distress after sudden infant or perinatal death: a 30-month follow up. J Paediatr Child Health. 2002;38:368–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2002.00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]