Abstract

Background

There is a trend toward decreasing length of hospital stay (LOS) after TKA although it is unclear whether this trend is detrimental to the overall postoperative course. Such information is important for future decisions related to cost containment.

Questions/purposes

We determined whether decreases in LOS after TKA are associated with increases in readmission rates.

Patients and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the rates and reasons for readmission and LOS for 4057 Medicare TKA patients from 2002 to 2007. We abstracted data from the Medicare Patient Safety Monitoring System. Hierarchical generalized linear modeling was used to assess the odds of changing readmission rates and LOS over time, controlling for changes in patient demographic and clinical variables.

Results

The overall readmission rate in the 30 days after discharge was 228/4057 (5.6%). The 10 most common reasons for readmission were congestive heart failure (20.4%), chronic ischemic heart disease (13.9%), cardiac dysrhythmias (12.5%), pneumonia (10.8%), osteoarthrosis (9.4%), general symptoms (7.4%), acute myocardial infarction (7.0%), care involving other specified rehabilitation procedure (6.3%), diabetes mellitus (6.3%), and disorders of fluid, electrolyte, and acid-base balance (5.9%); the top 10 causes did not include venous thromboembolism syndromes. We found no difference in the readmission rate between the periods 2002–2004 (5.5%) and 2005–2007 (5.8%) but a reduction in LOS between the periods 2002–2004 (4.1 ± 2.0 days) and 2005–2007 (3.8 ± 1.7 days).

Conclusions

The most common causes for readmission were cardiac-related. A reduction in LOS was not associated with an increase in the readmission rate in this sample. Optimization of cardiac status before discharge and routine primary care physician followup may lead to lower readmission rates.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis of the knee is a debilitating and increasingly common affliction. Recent estimates suggest the prevalence of doctor-diagnosed arthritis among adults in the United States will reach 96 million by 2050, a projected 1.6-fold increase from 2005 [4]. TKA is a cost-effective and increasingly common procedure used to treat arthritis of the knee [15, 18]. Demand for primary TKA is increasing and projected to grow by 673% by 2030 [14].

Despite the ability of TKA to reduce pain and improve function in patients with arthritis, it is a costly procedure. Thus, it is important to find ways of reducing costs while ensuring patients receive adequate operative and postoperative care. The equipment, personnel, and facilities needed for TKA comprise some of the costs, but the length of the postoperative hospital stay (LOS) is a major contributor. Factors contributing to LOS include preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative variables. Some of the causes of increased postoperative LOS are modifiable while others are not. Previous studies of risk factors associated with prolonged LOS after arthroplasty describe female gender, increasing age, comorbidities, obesity, higher American Society of Anesthesiologists-Physical Status scores, longer incisions, longer operative time, the need for transfusion, and postoperative complications as being associated with increased LOS [2, 3, 5, 7, 10–12].

LOS is decreasing for a broad variety of operative procedures. The causes are likely multifactorial and may include the introduction of less invasive procedures, the implementation of rigid perioperative protocols governing medications and perioperative procedures, and the streamlining of postoperative care by the implementation of evidence-based practices [13, 17]. Some suggest reductions in postoperative LOS in TKA are an effective cost reducer and do not increase postoperative adverse events (AEs) [9]. However, there are concerns that reductions in LOS may affect other postoperative outcomes, possibly causing prolonged stays in rehabilitation units, increasing adverse events after discharge, or increasing the need for readmission [6, 22].

We therefore asked whether reduced LOS is associated with an increase in the rate of readmission. We also sought to describe the most common causes for readmission.

Patients and Methods

We collected data as part of the Medicare Patient Safety Monitoring System (MPSMS), a nationwide surveillance project aimed at identifying the rates of specific AEs in Medicare beneficiaries by identifying AEs in inpatient medical records and administrative claims data [8]. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the Department of Health and Human Services Patient Safety Task Force led the coordination and development of the MPSMS. The MPSMS sample is a subset of the Hospital Payment Monitoring Program (HPMP) record sample. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services randomly selects the HPMP sample each month, using the Medicare National Claims History (NCH), from a pool of approximately 1 million Medicare beneficiary hospital discharges across 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands.

We drew our study sample from the MPSMS database, which included more than 180,000 hospital discharges between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2007. An equal number of charts was selected from each state. From within this larger sample, we selected the records of all 4063 patients who had TKA for degenerative arthritis during their hospitalization. We excluded six patients who died during their hospitalization or within the 30-day followup period. Thus, our sample consists of abstracted data from the medical records of 4057 Medicare patients. We recorded demographic and comorbidity characteristics of the study population (Table 1) and noted the changes in characteristics of the study population between 2002 and 2007. Comparing patients who underwent TKA in 2002 to 2004 and those who had the procedure in 2005 to 2007, the rate of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease decreased while the rates of obesity and diabetes mellitus increased.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries receiving TKA from 2002 to 2007

| Characteristic | 2002–2004 | 2005–2007 | p Value | Overall | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | Rate (%) | Number of patients | Rate (%) | Number of patients | Rate (%) | ||

| Total | 2033 | 100.0 | 2030 | 100.0 | 4,063 | 100.0 | |

| Demographics | |||||||

| Mean age (years) (SD) | 72.8 (7.4) | 72.8 (7.6) | 0.65 | 72.8 (7.5) | |||

| Age group | 0.89 | ||||||

| < 65 years | 151 | 7.4 | 159 | 7.8 | 310 | 7.6 | |

| 65–74 years | 1036 | 51.0 | 1034 | 50.9 | 2070 | 50.9 | |

| 75–84 years | 754 | 37.1 | 738 | 36.4 | 1492 | 36.7 | |

| > 84 years | 92 | 4.5 | 99 | 4.9 | 191 | 4.7 | |

| White | 1881 | 92.5 | 1851 | 91.2 | 0.12 | 3732 | 91.9 |

| Female | 1316 | 64.7 | 1322 | 65.1 | 0.79 | 2638 | 64.9 |

| Comorbidity | |||||||

| Cancer | 335 | 16.5 | 344 | 16.9 | 0.69 | 679 | 16.7 |

| Congestive heart failure | 146 | 7.2 | 120 | 5.9 | 0.10 | 266 | 6.5 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 340 | 16.7 | 271 | 13.3 | 0.002 | 611 | 15.0 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 153 | 7.5 | 151 | 7.4 | 0.92 | 304 | 7.5 |

| Diabetes | 379 | 18.6 | 447 | 22.0 | 0.008 | 826 | 20.3 |

| Corticosteroids | 68 | 3.3 | 55 | 2.7 | 0.24 | 123 | 3.0 |

| Obese | 292 | 14.4 | 347 | 17.1 | 0.017 | 639 | 15.7 |

| Smoking | 135 | 6.6 | 126 | 6.2 | 0.57 | 261 | 6.4 |

Our primary outcomes of interest were total LOS and 30-day readmission rate. We calculated LOS as a difference between dates of discharge and admission. If a patient was discharged at the same date as admission, we defined their LOS as 1 day. We calculated the rate of all-cause 30-day readmission from the NCH database by counting the total number of first rehospitalizations per 100 discharges within 30 days after discharge from a hospitalization that included a TKA, excluding patients who died during the index admission or within 30 days of discharge. We noted the recorded causes for the readmissions by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) code. We also reported the top 10 causes for 30-day readmission in our sample of 4057 patients receiving TKA.

We divided the sample into two subperiods, 2002 to 2004 and 2005 to 2007, to compare the outcomes of interest. We conducted descriptive and bivariate analyses to compare patient characteristics, LOS, and readmission rates between the two periods. We used the chi square test to compare dichotomous and categorical variables and the t test to compare continuous variables. Using these tests, we were able to generate 95% confidence intervals (CIs), p values, and odds ratios (ORs). We used the hierarchical generalized linear modeling (HGLM) approach to assess the odds of changing readmission rate and LOS over time, controlling for changes in patient demographic and clinical variables. All HGLMs were fitted with a random state-specific effect to account for within-state correlation of the outcomes and separate within-state variation from between-state variation. All statistical analyses were conducted with SAS® Version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and HGLMs were estimated using the GLIMMIX macro in SAS®.

Results

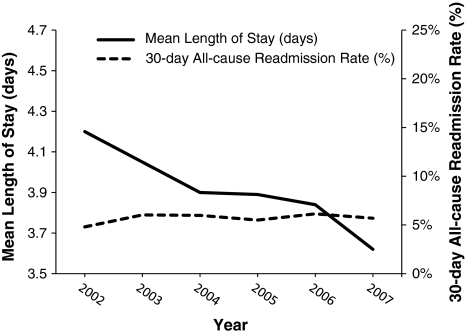

We observed a reduction (OR = 1.27; 95% CI = 1.25–1.29; p < 0.0001) in LOS between the 2002 to 2004 period (4.1 ± 2.0 days) and the 2005 to 2007 period (3.8 ± 1.7 days) (Fig. 1). The overall mean LOS from 2002 to 2007 was 3.9 ± 1.9 days. The overall rate of readmission in the 30 days after discharge was 228 of 4057 (5.6%). The HGLM supported a decrease (p < 0.001) in LOS and no increase in readmission rate from 2002 to 2007 (Table 2). There was no difference in the rate of readmission between the 2002 to 2004 period (5.5%) and the 2005 to 2007 period (5.8%) (OR = 1.08; 95% CI = 0.88–1.32; p = 0.46).

Fig. 1.

A graph shows the mean LOS and 30-day all-cause readmission rate in our sample of Medicare beneficiaries receiving TKA between 2002 and 2007. The LOS decreases while readmission rates remain stable. LOS = length of stay

Table 2.

Trend analysis for all-cause 30 day readmission and length of stay by year*

| Year | 30-day all-cause readmission† | Length of stay‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 95% confidence interval | p Value | Estimate | 95% confidence interval | p Value | |

| 2002 | 1.00 | 1.37 | 1.34–1.40 | |||

| 2003 | 1.09 | 0.77–1.55 | 0.626 | 1.33 | 1.29–1.36 | 0.029 |

| 2004 | 1.17 | 0.83–1.64 | 0.379 | 1.30 | 1.27–1.33 | < 0.001 |

| 2005 | 1.17 | 0.83–1.64 | 0.367 | 1.30 | 1.27–1.34 | < 0.001 |

| 2006 | 1.16 | 0.84–1.64 | 0.363 | 1.27 | 1.24–1.30 | < 0.001 |

| 2007 | 1.15 | 0.82–1.59 | 0.419 | 1.23 | 1.20–1.26 | < 0.001 |

* Estimates were drawn from a hierarchical generalized linear model; all estimates were adjusted for patient characteristics (age, gender, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, corticosteroids, smoking status, coronary artery disease, and renal failure; †for readmission, the estimate is odds ratio referenced to year 2002; ‡for length of stay, the estimate is the mean length of stay at log score.

The top 10 causes accounted for 31.1% of all causes for admission. Causes for readmission varied, and multiple causes were often listed per admission (Table 3). The top 10 causes for readmission did not include venous thromboembolic syndromes. Three of the top 10 causes for readmission were cardiac in nature, making up 53.9% of the top 10 readmission causes. Acute myocardial infarction alone made up 2.2% of all causes of readmission after TKA.

Table 3.

Top 10 readmission diagnoses*

| Admitting diagnosis | Admissions (number of patients) | Absolute rate (%) | Rate among top 10 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Congestive heart failure | 258 | 6.3 | 20.4 |

| Chronic ischemic heart disease | 176 | 4.3 | 13.9 |

| Cardiac dysrhythmias | 158 | 3.9 | 12.5 |

| Pneumonia | 136 | 3.3 | 10.8 |

| Osteoarthritis | 118 | 2.9 | 9.4 |

| General symptoms | 94 | 2.3 | 7.4 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 88 | 2.2 | 7.0 |

| Care involving specified rehabilitation procedure | 80 | 2.0 | 6.3 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 79 | 1.9 | 6.3 |

| Disorders of fluid, electrolyte, and acid-base balance | 75 | 1.8 | 5.9 |

* Reported are total number of readmissions with these diagnoses in the sample, rate among all readmissions, and rate among the top 10; a patient could be readmitted with more than one diagnosis within 30 days of initial discharge.

Discussion

Given the increasing need for TKA and the budget constraints of the Medicare system, it is in the interest of patients, payers, and providers to find ways of reducing costs while minimizing complications and still achieving the goals of the procedure. We sought to use a large Medicare data set to evaluate concurrent trends in LOS and readmission rates, in hopes that it would inform policy decisions by showing the consequences, or lack thereof, associated with decreasing LOS.

Our study was subject to limitations. First, we used administrative claims data to determine AEs after hospitalization, including 30-day causes of readmission. ICD-9 and Current Procedural Terminology codes can be ambiguous and may have overestimated or underestimated the prevalence of events, depending on the coding practices of the individual or the institution. Thus, we could only consider our conclusions to be associations and could not prove causation because of the possibility of omitted variable bias. However, using a database provided a relatively large study population. Second, we abstracted the chart outcomes, such as comorbidities, directly from the hospital charts as opposed to claims data. As this is a time-consuming process, nonphysicians completed the chart reviews using algorithms developed by physicians. While this could have led to inaccurate data, this method was far less costly than physician review, and it was likely it allowed for more sensitive detection of more AEs and comorbidities than if using inpatient claims data alone. Third, we observed some differences in demographics and comorbidities over the time period studied. Though we controlled for the comorbidities and demographics, there may have been other unmeasured characteristics of the TKA population that affected LOS and readmission rates, thereby potentially introducing bias into our results. Fourth, the MPSMS is a random sample from a set of all-cause hospitalizations. It was from this sample that we selected all TKA patients. Though the initial sample was designed to be nationally representative of all discharges, it was not designed to be nationally representative specifically for TKA patients. Further, an equal number of charts was abstracted from each state rather than selecting a number proportional to the population in each state. This may have introduced bias in the sample.

Over the time period studied, we found a decrease in overall postoperative LOS and no change in the 30-day readmission rate, indicating no association with decreasing hospital LOS and increases in readmission rate. Though the mean decrease in LOS over the time period studied was less than 1 day, it is important to note this indicates more patients were discharged on Postoperative Day 3 rather than Postoperative Day 4, as our unit of measure for LOS was entire calendar days. Though the decrease in LOS that we show may seem inconsequential to an individual patient, it likely represents a substantial difference in aggregate Medicare hospital costs, and the fact that readmission rates were stable in this time period suggests cutting costs by decreasing hospital stays could occur without increasing AEs requiring hospitalization. Given the projected rise in need for TKA and the projected rise in Medicare costs, these findings are timely and their policy implications should be carefully considered.

We chose to tabulate all-cause readmission as opposed to attempting to associate readmissions with the initial surgery. As the mechanisms that cause medical risk in the postoperative period were not completely elucidated, we believed the conservative decision to assess all-cause readmission was the appropriate approach. There was a large body of literature assessing LOS after arthroplasty and some studies attempted to test its relationship to readmission rates (Table 4) [1, 12, 16]. Unfortunately, comparing results between these studies was difficult as methodologies, study populations, and surgical practice settings differed. At the time of this study, there was no other study that specifically considered all-cause readmission after primary TKA in the Medicare population. A recent Danish study [12] used a slightly different methodology to assess LOS and readmission rates after TKA in a population-based study. They observed 784 patients who received TKA from 2004 to 2008, during which total LOS decreased from a mean of 4.6 day to 3.1 days, as a result of the implementation of a “fast-track” perioperative program. During the same time period, they noted the 90-day readmission rate increased from 12.9% to 20.4%. Readmission rates were much higher in the Danish study than in ours, despite the fact that the Danish study attempted to only count those readmissions that were attributable in some way to the initial operative procedure. However, the study had longer followup than ours, creating the potential to capture more readmissions. They also observed an increasing trend in the rate of readmission after TKA, which did not coincide with our study. This may be due to differences between thresholds for hospital admission in Denmark and the United States. They noted thresholds for readmission for diagnoses of deep venous thrombosis, infection, dislocation, and decreased ROM were lower in Denmark than in other settings, possibly accounting for more admissions. In fact, suspicion of deep venous thrombosis accounted for more than ½ of all readmissions in the Danish study.

Table 4.

Length of stay and readmission rate comparisons

| Study | Time period | Population | Length of stay (days) | Readmission rate (%) | Followup (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Husted et al. [12] | 2004–2008 | Danish TKA patients (n = 784) | 4.6–3.1 | 12.9–20.4 | 90 |

| Bini et al. [1] | 2001–2004 | Kaiser Permanente TKA patients (n = 5718) | 3.6 | 3.5 | 90 |

| Mahomed et al. [16] | 2000 | Medicare TKA patients (n = 136,712) | Not reported | 4.7 | 90 |

| Vorhies et al. | 2002–2007 | Medicare TKA patients (n = 4057) | 4.1–3.8 | 5.5–5.8 | 30 |

A recent study of 5718 patients who underwent TKA in the Kaiser Permanente Southern California Hospital system between 2001 and 2004 reported an average LOS of 3.6 days and a 90-day readmission rate of 3.5% [1]. This study also suggested patients discharged to skilled nursing facilities had higher rates of 90-day readmission but found no independent relationship between LOS and readmission rates. The low readmission rates we reported in this study likely reflect the exclusion criteria of the study, which excluded patients with American Society of Anesthesiologists-Physical Status scores of 3 or greater and all patients experiencing surgical complications during their initial hospitalization.

A population study using Medicare claims data over the year 2000 found the mean 90-day readmission rate for acute myocardial infarction after primary TKA to be only 0.8% [16]. The direct reasons for this difference were not readily apparent and were especially remarkable since the followup period for this study was three times longer than our study, creating the potential to capture more readmissions. The reasons for the different results are likely multifactorial, potentially relating to differing baseline demographics, sample sizes, and preoperative comorbidities of the study population, as well as changing thresholds for hospital admission. Regardless of the cause, these results indicate readmission rates for myocardial infarction after TKA in the Medicare population may have increased since 2000.

Cardiac comorbidities are common among candidates for TKA and these results may indicate more caution should be taken during preoperative screening and postoperative followup. Research also suggests more TKA operative candidates are at greater risk for cardiac complications than our current preoperative screening protocols identify. In a recent prospective study of dobutamine stress echocardiography (DSE) involving 96 patients with no history of ischemic heart disease scheduled to undergo elective arthroplasty, seven (7.3%) had abnormal results and five (5.2%) developed postoperative cardiac events [19]. Other studies also suggest the risk of cardiac events after lower extremity arthroplasty is greater than after other orthopaedic procedures [20]. Our data and other reports in the literature seem to suggest our preoperative screening and postoperative followup are inadequate, necessitating a shift to a lower threshold for preoperative screening tests, such as DSE, evidence-based usage of perioperative beta blockade, and possibly a scheduled followup with a primary care physician in the acute postoperative period after discharge [21]. Though it seems likely the subset of patients receiving TKA at high risk for cardiac complications needs more postoperative care, it remains unclear whether they would benefit from more inpatient care or careful outpatient followup would suffice.

Our data suggest postoperative LOS after TKA declined from 2002 to 2007. The 30-day readmission rates have remained relatively stable over the same time period, indicating the decrease in LOS does not result in an increase in readmission rates. This may indicate improved efficiency and cost savings, accompanied by preserved quality of patient care. Cardiac complications are the most common readmission diagnoses. Future efforts to improve preoperative cardiac screening and optimize cardiac status before and after discharge may lead to lower rates of readmission in the future.

Footnotes

WJM receives royalties from Zimmer Inc (Warsaw, IN) and Wright Medical Technology, Inc (Arlington, TN). JIH receives research support from Biomet Inc (Warsaw, IN) and is a consultant to Zimmer Inc (Warsaw, IN), Biomet, Smith and Nephew Inc (Memphis, TN), and PorOsteon Inc (Menlo Park, CA). All other authors certify that they have no commercial associations that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

These data were generated by the US Department of Health and Human Services and thus review by our local institutional review board is not required.

Work performed at Qualidigm and Stanford University.

References

- 1.Bini SA, Fithian DC, Paxton LW, Khatod MX, Inacio MC, Namba RS. Does discharge disposition after primary total joint arthroplasty affect readmission rates? J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:114–117. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dall GF, Ohly NE, Ballantyne JA, Brenkel IJ. The influence of pre-operative factors on the length of in-patient stay following primary total hip replacement for osteoarthritis: a multivariate analysis of 2302 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:434–440. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B4.21505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epps CD. Length stay, discharge disposition, and hospital charge predictors. AORN J. 2004;79:975–997. doi: 10.1016/S0001-2092(06)60729-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fontaine KR, Haaz S, Heo M. Projected prevalence of US adults with self-reported doctor-diagnosed arthritis, 2005 to 2050. Clin. Rheumatol. 2007;26:772–774. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0556-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foote J, Panchoo K, Blair P, Bannister G. Length of stay following primary total hip replacement. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91:500–504. doi: 10.1308/003588409X432356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forrest GP, Roque JM, Dawodu ST. Decreasing length of stay after total joint arthroplasty: effect on referrals to rehabilitation units. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:192–194. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9993(99)90120-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayes JH, Cleary R, Gillespie WJ, Pinder IM, Sher JL. Are clinical and patient assessed outcomes affected by reducing length of hospital stay for total hip arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:448–452. doi: 10.1054/arth.2000.4346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunt DR, Verzier N, Abend SL, Lyder C, Jaser LJ, Safer N, Davern P. Fundamentals of Medicare patient safety surveillance: intent, relevance, and transparency. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Marks ES, Lewin DI, editors. Advances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation. Vol 2. Concepts and Methodology. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Publication Number 05–0021-2; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Husni ME, Losina E, Fossel AH, Solomon DH, Mahomed NN, Katz JN. Decreasing medical complications for total knee arthroplasty: effect of critical pathways on outcomes. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:160. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Husted H, Hansen HC, Holm G, Bach-Dal C, Rud K, Andersen KL, Kehlet H. What determines length of stay after total hip and knee arthroplasty? A nationwide study in Denmark. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130:263–268. doi: 10.1007/s00402-009-0940-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Husted H, Holm G, Jacobsen S. Predictors of length of stay and patient satisfaction after hip and knee replacement surgery: fast-track experience in 712 patients. Acta Orthop. 2008;79:168–173. doi: 10.1080/17453670710014941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Husted H, Otte KS, Kristensen BB, Orsnes T, Kehlet H. Readmissions after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130:1185–1191. doi: 10.1007/s00402-010-1131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Evidence-based surgical care and the evolution of fast-track surgery. Ann. Surg. 2008;248:189–198. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31817f2c1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:780–785. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Losina E, Walensky RP, Kessler CL, Emrani PS, Reichmann WM, Wright EA, Holt HL, Solomon DH, Yelin E, Paltiel AD, Katz JN. Cost-effectiveness of total knee arthroplasty in the United States: patient risk and hospital volume. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1113–1121. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahomed NN, Barrett J, Katz JN, Baron JA, Wright J, Losina E. Epidemiology of total knee replacement in the United States Medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1222–1228. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Polk HC, Birkmeyer J, Hunt DR, Jones RS, Whittemore AD, Barraclough B. Quality and safety in surgical care. Ann. Surg. 2006;243:439–448. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000205820.57261.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Räsänen P, Paavolainen P, Sintonen H, Koivisto AM, Blom M, Ryynänen OP, Roine RP. Effectiveness of hip or knee replacement surgery in terms of quality-adjusted life years and costs. Acta Orthop. 2007;78:108–115. doi: 10.1080/17453670610013501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shetty VD, Nazare SP, Shitole BR, Jain SK, Kumar AV. Silent cardiac comorbidity in arthroplasty patients: an unusual suspect? J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:375–378. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Urban MK, Jules-Elysee K, Loughlin C, Kelsey W, Flynn E. The one year incidence of postoperative myocardial infarction in an orthopedic population. HSS J. 2008;4:76–80. doi: 10.1007/s11420-007-9070-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klei WA, Bryson GL, Yang H, Forster AJ. Effect of beta-blocker prescription on the incidence of postoperative myocardial infarction after hip and knee arthroplasty. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:717–724. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181b6a761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weingarten S, Riedinger MS, Sandhu M, Bowers C, Ellrodt AG, Nunn C, Hobson P, Greengold N. Can practice guidelines safely reduce hospital length of stay? Results from a multicenter interventional study. Am J Med. 1998;105:33–40. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(98)00129-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]