Abstract

Background

Surface replacement arthroplasties are commonly performed in young, active patients who desire return to high-impact activities including heavy manual labor and recreational sports. Femoral neck fracture is an arthroplasty-related complication unique to surface replacement arthroplasty. However, it is unclear regarding whether patients are at lower risk for fracture after a certain postoperative time.

Questions/purposes

We therefore raised the following questions: (1) does stress shielding occur after surface replacement arthroplasty, and (2) when does bone mineral density return to normal so patients can return to high-impact activities without excessive risk of fracture?

Patients and Methods

We prospectively enrolled 90 patients (96 hips) with either surface replacement arthroplasty or THA, and performed dual energy x-ray absorptiometry scans at 6 weeks, 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years. We analyzed bone density by Gruen zone in both groups, and six femoral neck zones in the patients who had surface replacement arthroplasties. We calculated 6-month, 1-year, and 2-year ratios for the change in bone density compared with baseline.

Results

Bone density was greater in patients who had surface replacement arthroplasties than for patients who had THAs at 6 months and 1 year in Gruen Zones 1, 2, 6, and 7, with the largest increase in femoral neck bone density on the tension side at 6 months in Zone L1. We saw no decrease in bone density in patients who had surface replacement arthroplasties in any Gruen zone at any time, and observed no decrease in bone density in female patients.

Conclusions

Increased bone density at 6 months postoperatively in patients who had surface replacement arthroplasties provides evidence that clinically relevant stress shielding does not occur after surface replacement arthroplasty. Owing to the increased bone mineral density at 6 months, we believe patients who underwent surface replacement arthroplasties may to return to high-impact activities at that time without increased risk of fracture.

Introduction

A surface replacement arthroplasty (SRA) is considered an alternative for younger patients wishing to remain active or return to heavy labor, and for whom the longevity of a THA is a concern [15]. Some of its proposed advantages include: maintenance of more normal anatomy [16], preservation of native proximal femoral bone [3, 27], and fewer dislocations [4, 27, 36]. It is postulated that SRA allows a more physiologic transfer of force [26], leading to less stress shielding and improved maintenance of bone mineral density (BMD) [20, 26]. Several studies using finite element analyses predict stress shielding still occurs in the femoral head and neck [33, 34, 42], leading to a decrease in BMD.

Loss of bone density in the proximal femur may be associated with two common complications seen with SRA: femoral neck fractures [4, 12, 27, 32, 36, 38] and aseptic loosening [1, 4, 9, 11, 40]. Femoral neck fractures reportedly occur in 0% to 4.7% of patients who undergo SRA [4, 12, 27, 32, 36, 38]; numerous surgical [2, 6, 7, 38] and patient-related factors [2, 6, 13, 14, 38] are thought to contribute to the risk of fracture. Patients typically decrease the cumulative forces transferred to the proximal femur during the initial postoperative period, owing to relative inactivity and, if additional stress shielding occurs, a premature return to high-impact activity might contribute to the risk of femoral neck fracture [12]. Although other factors such as pain, hip ROM, and muscle strength are important factors in restoring function, it is unclear when a patient who underwent SRA and is pain free, with good ROM and muscle strength, can resume high-impact activity without increased risk of femoral neck fracture. Numerous authors have reported that they allow patients to return to sports or heavy labor anywhere from 3 months to 1 year postoperatively [10, 12, 24, 30, 36]. This appears to be based solely on surgeon preference and, to our knowledge, there are no guidelines incorporating objective data to define an appropriate time for patients to return to high-impact sports or heavy manual labor.

The purposes of this study therefore were to: (1) determine the effect of SRA compared with THA on the BMD of the proximal femur postoperatively in a larger group of young, active patients, and (2) determine the time we can allow patients who underwent SRA to return to sports activities and heavy labor, based on changes in BMD.

Patients and Materials

We prospectively studied the femoral BMD in a cohort of 90 patients (96 hips) from a larger prospective study comparing outcomes between THA and SRA in young, active patients (Table 1). We prospectively planned to enroll 100 patients meeting eligibility criteria for the larger prospective study in an optional study arm to monitor bone density. We enrolled subjects in this optional arm of the study on a first-come, first-serve basis until we reached enrollment. Of the 100 patients enrolled, 10 did not return for a second followup after their initial dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan at 6 weeks; therefore, the change in BMD with time could not be calculated for these 10 patients and they were excluded from the final study group. Originally, we intended to obtain DEXA scans at 2 years postoperatively for all patients. After analyzing the current data, we decided to stop this study early to avoid any additional radiation exposure to our patients, as we found no changes in BMD between 6 months and 1 year for patients who had SRA. Fifty-two patients (56 hips) underwent SRA and 38 (40 hips) underwent THA with uncemented components. We recorded their UCLA and Harris hip scores (Table 2). Between November 2007 and October 2009, three surgeons (RMN, JCC, RLB) at one institution performed all procedures after the learning curve period for SRA [14, 28, 32]; thus we presume there would be fewer technical errors and more consistent surgery between patients. Our Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics

| Demographics | THA | SRA | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (hips) | 38 (40) | 52 (56) | |

| Age at surgery; years (range) | 48.9 (28–62) | 50.3 (22–65) | 0.491 |

| Sex (men/women) | 22/18 | 46/10 | 0.006 |

| Body mass index; kg/m² (range) | 27.5 (20.1–35.0) | 26.7 (20.1–34.5) | 0.872 |

| Diagnosis (osteoarthritis/avascular necrosis) | 32/8 | 56/0 | 0.001 |

| Operative side (right/left) | 20/20 | 31/25 | 0.680 |

THA = total hip arthroplasty; SRA = surface replacement arthroplasty.

Table 2.

Preoperative and postoperative UCLA and Harris hip scores

| Scores | THA | SRA | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative UCLA score (range) | 7 (2–10) | 7.5 (2–10) | 0.923 |

| Postoperative UCLA score (range) | 7.9 (3–10) | 8.2 (5–10) | 1.000 |

| Preoperative Harris hip score (range) | 56.4 (40.2–77.7) | 60.4 (10.2–86.0) | 0.073 |

| Postoperative Harris hip score (range) | 94.2 (62.4–100) | 95.5 (65.7–100) | 0.646 |

THA = total hip arthroplasty; SRA = surface replacement arthroplasty.

We included patients if they were skeletally mature, undergoing primary hip surgery for noninflammatory arthritis, had a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or less, and had an increased activity level defined by a presymptomatic UCLA activity score of 6 (regularly participates in moderate activities) or greater. Owing to concerns regarding age-related issues, including decreases in BMD, medical comorbidities, overall functional activity level, and results reported in the Australian Registry [39], we included only men between 18- and 65-years-old and women between 18- and 55-years-old. The THA control group was comprised of young, active patients who met all of the same inclusion criteria for SRA and would have been offered SRA, except they were excluded owing to: a desire to become pregnant, inadequate or abnormal bone stock to support the SRA device, osteonecrosis with greater than 50% involvement of the femoral head, multiple cysts in the femoral head larger than 1 cm, symptomatic leg length discrepancy greater than 1 cm, metal allergies, or renal insufficiency. We excluded patients with morbid obesity (BMI > 35,) neuromuscular disease, vascular insufficiency, muscular atrophy, or other important medical comorbidities that would limit their activities postoperatively, from the SRA and THA groups.

The average age of the patients was similar (p = 0.49) in the two groups: 48.9 years in the THA group and 50.3 years in the SRA group. The average presymptomatic UCLA score was higher (p = 0.017) in the SRA group than in the THA group: 8.9 versus 7.9, respectively.

Surgeons performed all operations through the posterolateral approach. During the SRA approach, the surgeons were careful to preserve the soft tissue along the femoral neck to avoid vascular compromise and the potential development of avascular necrosis to the femoral head. We allowed all patients to be full weightbearing immediately.

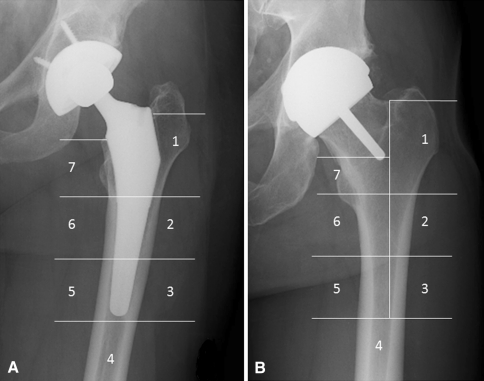

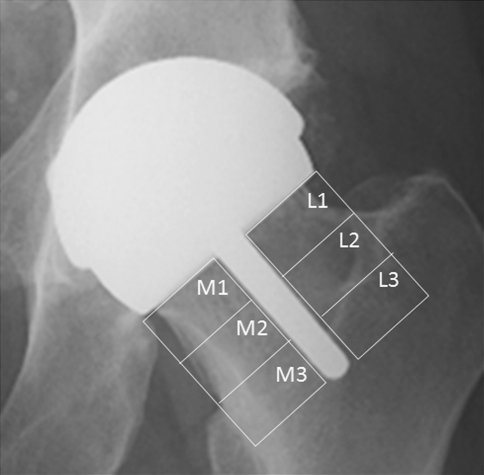

We obtained periprosthetic BMD using DEXA (Discovery A model; Hologic, Bedford, MA, USA). DEXA is a well-validated method to assess BMD in patients who have undergone hip resurfacing and THA [29, 43]. The same technician (CM) obtained scans and measurements at 6 weeks, 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years postoperatively, using the same template between each time for the patient, and standard foot and knee supports. We used prosthetic hip software (Hologic) to measure BMD in the seven Gruen zones [17] on the patients who had THAs and the regions corresponding to the seven Gruen zones in the patients who had SRAs (Fig. 1). In addition, we measured BMD in the femoral neck region in the patients who had SRAs (Fig. 2), as described previously [18, 22]; the femoral neck was divided into six equal regions of interest: three regions superolateral to the stem (L1-L3) and three regions inferomedial (M1-M3.) (Fig. 2) We used the 6-week BMD values as the baseline to calculate the percent change in BMD at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years for each patient, similar to a previously reported method [22, 31].

Fig. 1A–B.

The radiographs show (A) the seven Gruen zones in a patient undergoing THA, and (B) the Gruen zone template that was superimposed on the image from a patient undergoing surface replacement arthroplasty to allow comparison to the seven Gruen zones in a THA.

Fig. 2.

This radiograph shows the six regions of interest in the femoral neck; L1-L3 are lateral and M1-M3 are medial to the femoral neck stem.

To compare demographics and baseline clinical parameters between the THA and SRA groups, we used Student’s t-test for continuous variables, eg, age, BMI, and UCLA scores, and Pearson’s chi square test for sex and operation side. To examine the change of BMD during the study course (6-week, 6-month, 1-year, and 2-year), we constructed a mixed model with repeated measures, and we also compared the values between the surgically treated and the control hips. We chose compound symmetry covariance structure when taking into consideration with-subject correlations. Age, sex, BMI, and UCLA activity level were included in the model as important adjustment covariates. All tests were two sided. We used SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA) for all the statistical procedures.

Results

The percent change in BMD for the THA group compared with the SRA group at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years were associated with the greatest measured differences in the proximal femur in Gruen Zones 1, 2, 6, and 7 (Table 3). At 1 year, the differences between the THA group and SRA group persisted in Gruen Zones 1, 6, 7 (p < 0.0001), and Zone 2 (p = 0.0005), and at 2 years, in Zones 1 and 6 (p < 0.0001). In both groups, the BMD ratio in the distal femur in Gruen Zones 3, 4, and 5 stayed approximately 100% throughout all intervals. The percent of change in BMD in the THA and SRA groups at 6 weeks, 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years (Table 4) were decreased in the THA group in Gruen Zones 1, 2, and 7 (p < 0.0001), with the largest decrease in the medial calcar in Zone 7 (93.3%). There were no decreases in the SRA group at any time. There was no change in any Gruen zone in either group from 6 months to 1 year. There was no correlation in BMD with time associated with age, sex, preoperative UCLA activity score, or BMI in either group. In the SRA group there was no decrease in BMD in the femoral neck regions from 6 weeks to 6 months, 6 months to 1 year, and 1 year to 2 years (Table 5). The BMD on the lateral, tension side of the femoral neck increased to 109.8% at 1 year (p = 0.0165) and to 117.1% at 2 years (p = 0.0359). When divided into three lateral and three medial zones (Table 6), we found increases in BMD in L1 at 6 months (p = 0.0081) and at 1 year (p = 0.047), and in M3 at 1 year (p = 0.0052). The change in BMD with time (Tables 7, 8) was not associated with age, sex, preoperative UCLA activity score, or BMI.

Table 3.

Mean BMD ratios for THA compared with SRA

| Gruen zone | Procedure | 6 months (THA 37; SRA 50) | p value | 1 year (THA 37, SRA 50) | p value | 2 years (THA 7; SRA 23) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | THA | 93.7% | < 0.0001 | 91.9% | < 0.0001 | 95.9% | < 0.0001 |

| SRA | 100% | 101.4% | 104.7% | ||||

| 2 | THA | 96.7% | 0.0003 | 96.2% | 0.0005 | 97.7% | 0.1154 |

| SRA | 100.1% | 99.5% | 100.3% | ||||

| 3 | THA | 100.4% | 0.667 | 101.5% | 0.307 | 102.8% | 0.040 |

| SRA | 100.7% | 100.6% | 99.6% | ||||

| 4 | THA | 100.5% | 0.253 | 100.8% | 0.594 | 100.6% | 0.507 |

| SRA | 101.4% | 101.1% | 99.4% | ||||

| 5 | THA | 101.1% | 0.140 | 100.0% | 0.041 | 101.9% | 0.630 |

| SRA | 102.3% | 101.9% | 102.5% | ||||

| 6 | THA | 99.8% | < 0.0001 | 99.6% | < 0.0001 | 100% | < 0.0001 |

| SRA | 103.7% | 104.8% | 106.3% | ||||

| 7 | THA | 93.3% | < 0.0001 | 94.1% | < 0.0001 | 95.1% | 0.0006 |

| SRA | 101.8% | 104.1% | 105.8% |

BMD = bone mineral density; THA = total hip arthroplasty; SRA = surface replacement arthroplasty.

Table 4.

Mean BMD ratios in the proximal femur with time (THA versus THA and SRA versus SRA)

| Gruen zone | THA | SRA | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 weeks (n = 40) | 6 months (n = 37) | p value | 1 year (n = 37) | p value | 2 years (n = 7) | p value | 6 weeks (n = 56) | 6 months (n = 50) | p value | 1 year (n = 50) | p value | 2 years (n = 23) | p value | |

| 1 | 100% | 93.7% | < 0.0001 | 91.9% | 0.068 | 95.9% | 0.087 | 100% | 100.0% | 0.989 | 101.4% | 0.101 | 104.7% | 0.004 |

| 2 | 100% | 96.7% | < 0.0001 | 96.2% | 0.529 | 97.7% | 0.268 | 100% | 100.1% | 0.905 | 99.5% | 0.394 | 100.3% | 0.317 |

| 3 | 100% | 100.4% | 0.57 | 101.5% | 0.117 | 102.8% | 0.351 | 100% | 100.7% | 0.275 | 100.6% | 0.899 | 99.6% | 0.233 |

| 4 | 100% | 100.5% | 0.502 | 100.8% | 0.714 | 100.6% | 0.861 | 100% | 101.4% | 0.051 | 101.1% | 0.754 | 99.4% | 0.049 |

| 5 | 100% | 101.1% | 0.167 | 100.0% | 0.200 | 101.9% | 0.203 | 100% | 102.3% | 0.0007 | 101.9% | 0.512 | 102.5% | 0.464 |

| 6 | 100% | 99.8% | 0.767 | 99.6% | 0.818 | 100.0% | 0.777 | 100% | 103.7% | < 0.0001 | 104.8% | 0.121 | 106.3% | 0.086 |

| 7 | 100% | 93.3% | < 0.0001 | 94.1% | 0.563 | 95.1% | 0.712 | 100% | 101.8% | 0.154 | 104.1% | 0.086 | 105.8% | 0.311 |

BMD = bone mineral density; THA = total hip arthroplasty; SRA = surface replacement arthroplasty; n = number of hips.

Table 5.

Mean BMD ratios in the lateral and medial femoral neck with time

| Zone | 6 weeks | 6 months | p value | 1 year | p value | 2 years | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lateral | 100.0% | 103.5% | 0.215 | 109.8% | 0.017 | 117.1% | 0.036 |

| Medial | 100.0% | 99.1% | 0.799 | 104.2% | 0.135 | 107.0% | 0.526 |

BMD = bone mineral density.

Table 6.

Mean BMD ratios in the femoral neck in the SRA group

| Region of interest | 6 weeks (n = 56) | 6 months (n = 50) | p value | 1 year (n = 50) | p value | 2 years (n = 23) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | 100.0% | 104.3% | 0.008 | 107.6% | 0.047 | 111.6% | 0.055 |

| L2 | 100.0% | 100.8% | 0.486 | 102.8% | 0.130 | 105.8% | 0.066 |

| L3 | 100.0% | 100.7% | 0.550 | 102.6% | 0.100 | 104.2% | 0.285 |

| M1 | 100.0% | 99.7% | 0.721 | 100.9% | 0.235 | 101.0% | 0.592 |

| M2 | 100.0% | 99.9% | 0.877 | 101.6% | 0.050 | 101.0% | 0.592 |

| M3 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 0.975 | 102.0% | 0.005 | 102.5% | 0.597 |

BMD = bone mineral density; SRA = surface replacement arthroplasty.

Table 7.

Mean BMD for THA and SRA

| Gruen zone | Procedure | 6 weeks | 6 months | 1 year | 2 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | THA | 0.782 | 0.738 | 0.718 | 0.756 |

| SRA | 0.834 | 0.839 | 0.851 | 0.872 | |

| 2 | THA | 1.525 | 1.484 | 1.456 | 1.512 |

| SRA | 1.468 | 1.471 | 1.463 | 1.483 | |

| 3 | THA | 1.737 | 1.742 | 1.746 | 1.812 |

| SRA | 1.891 | 1.911 | 1.906 | 1.893 | |

| 4 | THA | 1.916 | 1.930 | 1.926 | 1.937 |

| SRA | 2.025 | 2.056 | 2.053 | 2.013 | |

| 5 | THA | 1.783 | 1.802 | 1.785 | 1.824 |

| SRA | 1.879 | 1.919 | 1.912 | 1.924 | |

| 6 | THA | 1.597 | 1.592 | 1.583 | 1.566 |

| SRA | 1.506 | 1.576 | 1.583 | 1.609 | |

| 7 | THA | 1.303 | 1.233 | 1.196 | 1.222 |

| SRA | 1.237 | 1.291 | 1.303 | 1.370 |

BMD = bone mineral density; THA = total hip arthroplasty; SRA = surface replacement arthroplasty.

Table 8.

Mean BMD in the femoral neck in the SRA group

| Region of interest | 6 weeks | 6 months | 1 year | 2 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total lateral region | 2.300 | 2.369 | 2.426 | 2.456 |

| Total medial region | 3.813 | 3.848 | 3.903 | 3.891 |

| L1 | 0.738 | 0.783 | 0.803 | 0.811 |

| L2 | 0.737 | 0.747 | 0.767 | 0.777 |

| L3 | 0.825 | 0.839 | 0.856 | 0.868 |

| M1 | 1.167 | 1.174 | 1.182 | 1.173 |

| M2 | 1.255 | 1.266 | 1.287 | 1.269 |

| M3 | 1.391 | 1.408 | 1.435 | 1.449 |

BMD = bone mineral density; SRA = surface replacement arthroplasty.

After obtaining all of our DEXA data showing that there is increased BMD by 6 months postoperatively in the patients who underwent SRA, we then changed our postoperative management to allow patients who showed acceptable improvement in ROM and strength testing to return to unlimited activity at that time. To date we have performed more than 420 SRAs at our institution with no femoral neck fractures and including the last 120 patients who underwent SRAs during the past 2 years in which we have allowed them unrestricted return to impact activities at the 6-month postoperative period. These observations suggest that patients undergoing SRA can return to high-impact activities 6 months after surgery and proper rehabilitation with no increased risk in fracture.

Discussion

SRA is commonly performed in young, active patients who desire the ability to return to recreational sports and physically demanding jobs after surgery. These high-impact activities place additional forces across the hip and have the potential to cause fractures of the femoral neck, a unique complication after hip resurfacing surgery. To date, there are no objective data to help surgeons determine when it is safe for patients who have had SRA to return to high-impact activities and avoid the potential of a femoral neck fracture. The purposes of this study were to: (1) determine the effect of SRA compared with THA on the BMD of the proximal femur postoperatively in a larger group of young, active patients, and (2) determine the time in which we can allow patients who underwent SRA to return to sports activities and heavy labor, based on changes in BMD.

Our study has some limitations. First are those inherent to using a DEXA scan to quantify BMD, especially in the bone adjacent to a metal implant [29]. DEXA scans around THA implants have been reported to have low variation between repeat measurements: BMD variation of 0.0035 within the same region of interest [29], and a low coefficient of variation (1.3%–6.1%) [29, 35, 43, 44]. We attempted to minimize this variability in our study by using the same DEXA scanner, the same technician to perform the scans, and the same template to measure bone density for all scans. Second, it is not possible to accurately compare preoperative BMD (before implant) with postoperative BMD owing to the inherent distortion that the metal implants create for the BMD-analysis software. We do not know, however, how much distortion might occur or what errors such distortion might introduce into our data. Third, we had a greater percentage of females in the THA group, and there were eight patients with avascular necrosis in the THA group compared with no patients with avascular necrosis in the SRA group. This difference is attributable to our patient selection process for determining if a young active patient is a good candidate for SRA. Owing to concerns regarding early failure of SRA in female patients with small component sizes and in patients with avascular necrosis involving greater than 50% of the femoral head, we avoided performing SRA in these patients who otherwise would be good candidates for SRA with their activity levels. Fourth, our study focused only on stress shielding and the changes in BMD after THA and SRA and did not focus on the clinical outcomes such as return to high-impact employment and return to sports for these patients. Further research is being conducted at our center and others to address this clinical question.

Periprosthetic bone loss secondary to stress shielding in the proximal femur is well-documented in patients undergoing THAs [20], occurring primarily in Gruen Zones 1 and 7 [8, 31, 41, 44], largely during the first postoperative year [22, 31, 41]. Two previous DEXA studies of small patient cohorts [19, 22] compare BMD in patients undergoing THA and SRA using a baseline BMD from 3 weeks postoperatively. Patients who underwent SRA experienced minimal stress shielding, whereas patients who underwent THA had a decrease of approximately 15%. In comparison, our observations with a much larger, prospective cohort show no evidence of stress shielding in patients who underwent SRA. One possible reason for the difference might be the more stringent selection of young, active patients for our study.

Bone quality in the femoral neck is of particular importance in patients undergoing SRA as it might be related to femoral neck fractures [4, 12, 27, 32, 36, 38] and aseptic loosening [1, 4, 9, 11, 40]. Based on finite element analysis of a SRA, one study reported that SRA-implanted hips experience stress and strain in the femoral neck that is near normal and produce less stress shielding and bone remodeling than with THA [26]. Although other finite element analyses predict stress shielding occurring in patients undergoing SRA in the superolateral portion of the femoral neck [33, 34, 42], we did not detect stress shielding in any of the three superolateral or three inferomedial zones. On the contrary, we observed an increase in BMD in the L1 region at 6 months and 1 year, in the M3 region at 1 year, and in the lateral region as a whole (L1-L3) at 1 year and 2 years; we believe these increases are clinically important in the SRA group as they occur on the tension side of the bone where any potential femoral neck fractures would likely be initiated, especially during high-impact activities. Cooke et al. [10] observed a decrease in BMD in the superolateral zone of the femoral neck of 9% at 6 weeks and 8% at 3 months. In contrast, we found no decrease in the lateral region and did not find as large of an absolute change between 6 weeks and 1 year. Some of the differences in these findings may be attributed to the fact that they measured preoperative BMD. We believe an early postoperative baseline measurement is more accurate, given the sensitivity of the DEXA-analysis software to changes in the template area to be measured. We found it is unreliable when comparing DEXA images from before and after implantation owing to loss of some of the preoperative bony landmarks for template standardization. The metal implant in the postoperative scans, especially the femoral stem for the SRA inside the femoral neck, distorts the actual quantity of bone to be measured. Last, using a preoperative BMD measurement as the baseline instead of a postoperative BMD measurement overestimates the change in BMD and stress shielding [23].

Femoral neck fracture is a common indication for SRA revision [4, 37, 39]. In the literature, the mean time to fracture ranges from 9 weeks to 15.4 weeks, with the majority of the fractures occurring during the first year [4, 14, 25, 38]. We observed no change in BMD in the femoral neck during the first postoperative year that provides evidence that stress shielding after SRA contributes to the incidence of femoral neck fracture in those studies. In addition, female sex and loosening reportedly are associated with an increased revision rate for fracture [1, 14, 21, 38]. However, several analyses reported that when the size of the femoral head component is controlled for, female sex no longer is associated with an increased fracture risk [5, 37]. Correspondingly, we did not find a difference in the change in BMD between male and female patients who underwent SRA.

We found a lack of stress shielding and rather preservation of BMD in the femoral neck and proximal femur of patients undergoing SRA compared with patients undergoing THA. Six months after hip resurfacing we detected no stress shielding, and we found no difference in BMD between 6 months and 1 year for these patients. Therefore, we have changed our management of patients undergoing SRA to allow them to return to full, unrestricted sport activity and heavy labor at 6 months. However, if technical factors such as femoral neck notching or varus placement of the femoral stem occur, the surgeon should use caution when deciding the appropriate time to allow the patient to return to sports activity or heavy labor.

Acknowledgements

We thank our DEXA technician, Cheryl Mueller, for assistance and dedication.

Footnotes

One author (RMN) is a paid consultant for and has received funding from Smith and Nephew Orthopaedics in support of this study. One author (RLB) has received royalties from Smith and Nephew Orthopaedics (Memphis, TN, USA). All of the remaining authors certify that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, and all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at Washington University, St Louis, Missouri.

References

- 1.Amstutz HC, Beaule PE, Dorey FJ, Le Duff MJ, Campbell PA, Gruen TA. Metal-on-metal hybrid surface arthroplasty: two to six-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:28–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amstutz HC, Campbell PA, Le Duff MJ. Fracture of the neck of the femur after surface arthroplasty of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:1874–1877. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200409000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amstutz HC, Grigoris P, Dorey FJ. Evolution and future of surface replacement of the hip. J Orthop Sci. 1998;3:169–186. doi: 10.1007/s007760050038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amstutz HC, Duff MJ. Eleven years of experience with metal-on-metal hybrid hip resurfacing: a review of 1000 conserve plus. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(6 suppl 1):36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amstutz HC, Wisk LE, Duff MJ. Sex as a patient selection criterion for metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:198–208. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anglin C, Masri BA, Tonetti J, Hodgson AJ, Greidanus NV. Hip resurfacing femoral neck fracture influenced by valgus placement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;465:71–79. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e318137a13f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaule PE, Dorey FJ, LeDuff MJ, Gruen T, Amstutz HC. Risk factors affecting outcome of metal-on-metal surface arthroplasty of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;418:87–93. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200401000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boden HS, Skoldenberg OG, Salemyr MO, Lundberg HJ, Adolphson PY. Continuous bone loss around a tapered uncemented femoral stem: a long-term evaluation with DEXA. Acta Orthop. 2006;77:877–885. doi: 10.1080/17453670610013169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell P, Mirra J, Amstutz HC. Viability of femoral heads treated with resurfacing arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:120–122. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(00)91415-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooke NJ, Rodgers L, Rawlings D, McCaskie AW, Holland JP. Bone density of the femoral neck following Birmingham hip resurfacing. Acta Orthop. 2009;80:660–665. doi: 10.3109/17453670903486992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corten K, MacDonald SJ. Hip resurfacing data from national joint registries: what do they tell us? What do they not tell us? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:351–357. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1157-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daniel J, Pynsent PB, McMinn DJ. Metal-on-metal resurfacing of the hip in patients under the age of 55 years with osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:177–184. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B2.14600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Smet KA. Belgium experience with metal-on-metal surface arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2005;36:203–213, ix. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Valle CJ, Nunley RM, Raterman SJ, Barrack RL. Initial American experience with hip resurfacing following FDA approval. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:72–78. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0563-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorr LD, Kane TJ, 3rd, Conaty JP. Long-term results of cemented total hip arthroplasty in patients 45 years old or younger: a 16-year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty. 1994;9:453–456. doi: 10.1016/0883-5403(94)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Girard J, Lavigne M, Vendittoli PA, Roy AG. Biomechanical reconstruction of the hip: a randomised study comparing total hip resurfacing and total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:721–726. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B6.17447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gruen TA, McNeice GM, Amstutz HC. “Modes of failure” of cemented stem-type femoral components: a radiographic analysis of loosening. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;141:17–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harty JA, Devitt B, Harty LC, Molloy M, McGuinness A. Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry analysis of peri-prosthetic stress shielding in the Birmingham resurfacing hip replacement. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2005;125:693–695. doi: 10.1007/s00402-005-0059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayaishi Y, Miki H, Nishii T, Hananouchi T, Yoshikawa H, Sugano N. Proximal femoral bone mineral density after resurfacing total hip arthroplasty and after standard stem-type cementless total hip arthroplasty, both having similar neck preservation and the same articulation type. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:1208–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huiskes R, Weinans H, Rietbergen B. The relationship between stress shielding and bone resorption around total hip stems and the effects of flexible materials. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;274:124–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jameson SS, Langton DJ, Natu S, Nargol TV. The influence of age and sex on early clinical results after hip resurfacing: an independent center analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(6 suppl 1):50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kishida Y, Sugano N, Nishii T, Miki H, Yamaguchi K, Yoshikawa H. Preservation of the bone mineral density of the femur after surface replacement of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:185–189. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B2.14338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroger H, Miettinen H, Arnala I, Koski E, Rushton N, Suomalainen O. Evaluation of periprosthetic bone using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry: precision of the method and effect of operation on bone mineral density. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11:1526–1530. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650111020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lavigne M, Therrien M, Nantel J, Roy A, Prince F, Vendittoli PA. The John Charnley Award: The functional outcome of hip resurfacing and large-head THA is the same: a randomized, double-blind study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:326–336. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0938-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Little CP, Ruiz AL, Harding IJ, McLardy-Smith P, Gundle R, Murray DW, Athanasou NA. Osteonecrosis in retrieved femoral heads after failed resurfacing arthroplasty of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:320–323. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Little JP, Taddei F, Viceconti M, Murray DW, Gill HS. Changes in femur stress after hip resurfacing arthroplasty: response to physiological loads. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2007;22:440–448. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McMinn D, Treacy R, Lin K, Pynsent P. Metal on metal surface replacement of the hip: experience of the McMinn prothesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;329(suppl):S89–S98. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199608001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mont MA, Seyler TM, Ulrich SD, Beaule PE, Boyd HS, Grecula MJ, Goldberg VM, Kennedy WR, Marker DR, Schmalzried TP, Sparling EA, Vail TP, Amstutz HC. Effect of changing indications and techniques on total hip resurfacing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;465:63–70. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e318159dd60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murray JR, Cooke NJ, Rawlings D, Holland JP, McCaskie AW. A reliable DEXA measurement technique for metal-on-metal hip resurfacing. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:177–181. doi: 10.1080/00016470510030544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Narvani AA, Tsiridis E, Nwaboku HC, Bajekal RA. Sporting activity following Birmingham hip resurfacing. Int J Sports Med. 2006;27:505–507. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishii T, Sugano N, Masuhara K, Shibuya T, Ochi T, Tamura S. Longitudinal evaluation of time related bone remodeling after cementless total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;339:121–131. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199706000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nunley RM, Zhu J, Brooks PJ, Engh CA, Jr, Raterman SJ, Rogerson JS, Barrack RL. The learning curve for adopting hip resurfacing among hip specialists. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:382–391. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1106-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ong KL, Day JS, Kurtz SM, Field RE, Manley MT. Role of surgical position on interface stress and initial bone remodeling stimulus around hip resurfacing arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:1137–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pal B, Gupta S, New AM. A numerical study of failure mechanisms in the cemented resurfaced femur: effects of interface characteristics and bone remodelling. Proc Inst Mech Eng H. 2009;223:471–484. doi: 10.1243/09544119JEIM488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Penny JO, Ovesen O, Brixen K, Varmarken JE, Overgaard S. Bone mineral density of the femoral neck in resurfacing hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2010;81:318–323. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2010.480935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pollard TC, Baker RP, Eastaugh-Waring SJ, Bannister GC. Treatment of the young active patient with osteoarthritis of the hip: a five- to seven-year comparison of hybrid total hip arthroplasty and metal-on-metal resurfacing. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:592–600. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B5.17354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prosser GH, Yates PJ, Wood DJ, Graves SE, Steiger RN, Miller LN. Outcome of primary resurfacing hip replacement: evaluation of risk factors for early revision. Acta Orthop. 2010;81:66–71. doi: 10.3109/17453671003685434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shimmin AJ, Back D. Femoral neck fractures following Birmingham hip resurfacing: a national review of 50 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:463–464. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B4.15498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shimmin AJ, Bare J, Back DL. Complications associated with hip resurfacing arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2005;36:187–193, ix. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Taylor M, Tanner KE. Fatigue failure of cancellous bone: a possible cause of implant migration and loosening. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79:181–182. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.79B2.7461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Venesmaa PK, Kroger HP, Miettinen HJ, Jurvelin JS, Suomalainen OT, Alhava EM. Monitoring of periprosthetic BMD after uncemented total hip arthroplasty with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry: a 3-year follow-up study. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:1056–1061. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.6.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watanabe Y, Shiba N, Matsuo S, Higuchi F, Tagawa Y, Inoue A. Biomechanical study of the resurfacing hip arthroplasty: finite element analysis of the femoral component. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:505–511. doi: 10.1054/arth.2000.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilkinson JM, Peel NF, Elson RA, Stockley I, Eastell R. Measuring bone mineral density of the pelvis and proximal femur after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:283–288. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B2.10562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamaguchi K, Masuhara K, Ohzono K, Sugano N, Nishii T, Ochi T. Evaluation of periprosthetic bone-remodeling after cementless total hip arthroplasty: the influence of the extent of porous coating. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:1426–1431. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200010000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]