Abstract

Background

Coronal malalignment occurs frequently in TKA and may affect implant durability and knee function. Designed to improve alignment accuracy and precision, the patient-specific positioning guide is predicated on restoration of the overall mechanical axis and is a multifaceted new tool in achieving traditional goals of TKA.

Questions/purposes

We compared the effectiveness of patient-specific positioning guides to manual instrumentation with intramedullary femoral and extramedullary tibial guides in restoring the mechanical axis of the extremity and achieving neutral coronal alignment of the femoral and tibial components.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 569 TKAs performed with patient-specific positioning guides and 155 with manual instrumentation by two surgeons using postoperative long-leg radiographs. For all patients, we assessed the zone in which the overall mechanical axis passed through the knee, and for one surgeon’s cases (105 patient-specific positioning guide, 55 manual instrumentation), we also measured the hip-knee-ankle angle and the individual component angles with respect to their mechanical axes.

Results

The overall mechanical axis passed through the central third of the knee more often with patient-specific positioning guides (88%) than with manual instrumentation (78%). The overall mean hip-knee-ankle angle for patient-specific positioning guides (180.6°) was similar to manual instrumentation (181.1°), but there were fewer ± 3° hip-knee-ankle angle outliers with patient-specific positioning guides (9%) than with manual instrumentation (22%). The overall mean tibial (89.9° versus 90.4°) and femoral (90.7° versus 91.3°) component angles were closer to neutral with patient-specific positioning guides than with manual instrumentation, but the rate of ± 2° outliers was similar for both the tibia (10% versus 7%) and femur (22% versus 18%).

Conclusions

Patient-specific positioning guides can assist in achieving a neutral mechanical axis with reduction in outliers.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

The long-held tenet in TKA of restoration of a neutral overall mechanical axis (OMA) is supported by numerous biomechanical [28], finite element [2, 44], and clinical studies [5, 17, 27, 35, 47, 48, 52, 70, 84], both historical and contemporary, demonstrating increased strain, higher failure rates, and, in many cases, lower functional scores with coronal malalignment. Recently, three-dimensional imaging and custom manufacturing have enabled the development of patient-specific positioning guides (PSPGs). Designed primarily to improve alignment accuracy and precision, PSPG technology harnesses the power of computer templating yet promotes greater surgical simplicity by eliminating the intraoperative presence of the computer.

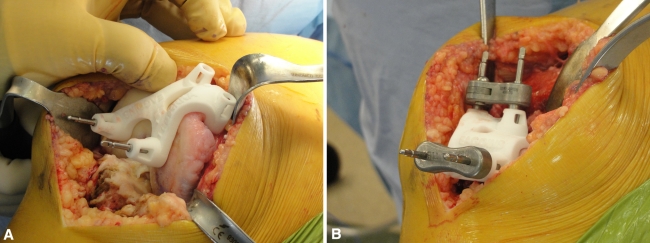

Unlike manual instrumentation (MI) with intramedullary and extramedullary alignment rods, PSPG technology uses preoperative MRI or CT to design custom shape-fitting jigs (Fig. 1) that conform to the articular surface of the proximal tibia and distal femur to facilitate pin placement for traditional cutting blocks. Some designs incorporate cutting slots into the guide.

Fig. 1 A–B.

The photograph displays the PSPG and its use intraoperatively to facilitate accurate pin placement on the (A) femur and (B) tibia for standard cutting blocks.

Even in the hands of experienced surgeons, MI results in overall coronal malalignment (> 3° from neutral) in approximately 28% of patients (Table 1). Although computer-assisted navigation (CAN) reduces the number of outliers by approximately threefold (Table 1), it requires additional operative time compared to MI [11] and may increase the rate of complications, such as postoperative stress fracture [10, 55]. PSPGs purportedly eliminate many of the disadvantages of CAN, including surgical prolongation and fiducial pin complications [33, 81], while enabling individualized bone resections that match the measured mechanical axis.

Table 1.

Percent of coronal alignment outliers in conventional (manual) instrumentation and computer navigation in prior studies

| Study | Year | Number of navigated TKAs | Navigated outliers > ± 3° | Percentage of navigation outliers | Number of conventional TKAs | Conventional outliers > ± 3° | Percentage of conventional outliers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stulberg et al. [82] | 2000 | 15 | 0 | 0.0% | 15 | 5 | 33.3% |

| Saragaglia et al. [72] | 2001 | 25 | 4 | 16.0% | 25 | 6 | 24.0% |

| Jenny and Boeri [36] | 2001 | 30 | 5 | 16.7% | 30 | 9 | 30.0% |

| Sparmann et al. [80] | 2003 | 120 | 0 | 0.0% | 120 | 16 | 13.3% |

| Oberst et al. [64] | 2003 | 12 | 0 | 0.0% | 13 | 5 | 38.5% |

| Bathis et al. [3] | 2004 | 50 | 2 | 4.0% | 50 | 12 | 24.0% |

| Bathis et al. [4] | 2004 | 80 | 3 | 3.8% | 80 | 18 | 22.5% |

| Chauhan et al. [14] | 2004 | 35 | 2 | 5.7% | 35 | 10 | 28.6% |

| Matsumoto et al. [56] | 2004 | 30 | 2 | 6.7% | 30 | 10 | 33.3% |

| Perlick et al. [68] | 2004 | 40 | 3 | 7.5% | 40 | 11 | 27.5% |

| Perlick et al. [69] | 2004 | 50 | 4 | 8.0% | 50 | 12 | 24.0% |

| Victor and Hoste [86] | 2004 | 48 | 0 | 0.0% | 49 | 13 | 26.5% |

| Anderson et al. [1] | 2005 | 116 | 6 | 5.2% | 51 | 8 | 15.7% |

| Böhling et al. [9] | 2005 | 50 | 3 | 6.0% | 50 | 27 | 54.0% |

| Chin et al. [16] | 2005 | 30 | 3 | 10.0% | 60 | 22 | 36.7% |

| Confalonieri et al. [20] | 2005 | 38 | 5 | 13.2% | 77 | 21 | 27.3% |

| Daubresse et al. [21] | 2005 | 50 | 0 | 0.0% | 50 | 14 | 28.0% |

| Haaker et al. [29] | 2005 | 100 | 21 | 21.0% | 100 | 72 | 72.0% |

| Jenny et al. [37] | 2005 | 235 | 18 | 7.7% | 235 | 65 | 27.7% |

| Kim et al. [39] | 2005 | 69 | 4 | 5.8% | 78 | 21 | 26.9% |

| Skowronski et al. [78] | 2005 | 100 | 21 | 21.0% | 100 | 44 | 44.0% |

| Zorman et al. [89] | 2005 | 71 | 0 | 0.0% | 64 | 19 | 29.7% |

| Chang and Yang [13] | 2006 | 48 | 9 | 18.8% | 29 | 12 | 41.4% |

| Macule-Beneyto et al. [51] | 2006 | 102 | 53 | 52.0% | 84 | 59 | 70.2% |

| Seon and Song [75] | 2006 | 49 | 3 | 6.1% | 53 | 6 | 11.3% |

| Bertsch et al. [7] | 2007 | 34 | 2 | 5.9% | 35 | 7 | 20.0% |

| Ensini et al. [26] | 2007 | 60 | 1 | 1.7% | 60 | 12 | 20.0% |

| Kim et al. [41] | 2007 | 100 | 28 | 28.0% | 100 | 35 | 35.0% |

| Martin et al. [53] | 2007 | 100 | 8 | 8.0% | 100 | 24 | 24.0% |

| Matziolis et al. [58] | 2007 | 32 | 1 | 3.1% | 28 | 7 | 25.0% |

| Mullaji et al. [61] | 2007 | 282 | 29 | 10.3% | 185 | 40 | 21.6% |

| Park and Lee [66] | 2007 | 32 | 3 | 9.4% | 30 | 9 | 30.0% |

| Seon et al. [76] | 2007 | 42 | 2 | 4.8% | 42 | 8 | 19.0% |

| Bonutti et al. [12] | 2008 | 50 | 3 | 6.0% | 50 | 1 | 2.0% |

| Chotanaphuti et al. [18] | 2008 | 90 | 5 | 5.6% | 90 | 12 | 13.3% |

| Dutton et al. [23] | 2008 | 52 | 4 | 7.7% | 56 | 18 | 32.1% |

| Ek et al. [24] | 2008 | 50 | 11 | 22.0% | 50 | 19 | 38.0% |

| Lüring et al. [49] | 2008 | 30 | 0 | 0.0% | 60 | 5 | 8.3% |

| Lützner et al. [50] | 2008 | 40 | 5 | 12.5% | 40 | 7 | 17.5% |

| Mizu-uchi et al. [59] | 2008 | 37 | 3 | 8.1% | 39 | 9 | 23.1% |

| Oberst et al. [63] | 2008 | 34 | 2 | 5.9% | 35 | 7 | 20.0% |

| Rosenberger et al. [71] | 2008 | 50 | 5 | 10.0% | 50 | 21 | 42.0% |

| Tingart et al. [85] | 2008 | 500 | 26 | 5.2% | 500 | 128 | 25.6% |

| Yau et al. [87] | 2008 | 52 | 15 | 28.8% | 52 | 13 | 25.0% |

| Biasca et al. [8] | 2009 | 20 | 0 | 0.0% | 20 | 0 | 0.0% |

| Cheung and Chiu [15] | 2009 | 47 | 10 | 21.3% | 47 | 27 | 57.4% |

| Kim et al. [40] | 2009 | 160 | 20 | 12.5% | 160 | 30 | 18.8% |

| Pang et al. [65] | 2009 | 35 | 2 | 5.7% | 35 | 9 | 25.7% |

| Seon et al. [74] | 2009 | 43 | 2 | 4.7% | 42 | 9 | 21.4% |

| Hernández-Vaquero et al. [32] | 2010 | 40 | 2 | 5.0% | 40 | 21 | 52.5% |

| Lee et al. [43] | 2010 | 60 | 5 | 8.3% | 56 | 16 | 28.6% |

| Hasagawa et al. [31] | 2011 | 50 | 3 | 6.0% | 50 | 11 | 22.0% |

| Ishida et al. [34] | 2011 | 26 | 5 | 19.2% | 27 | 10 | 37.0% |

| Schmitt et al. [73] | 2011 | 57 | 15 | 26.3% | 30 | 6 | 20.0% |

| Total | 3798 | 388 | 10.2% | 3677 | 1038 | 28.2% | |

| Ng et al. | 2011 | 569 (PSPG) | 82 (PSPG) | 14.4% (PSPG) | 155 (MI) | 43 (MI) | 27.7% (MI) |

PSPG = patient-specific positioning guide; MI = manual instrumentation.

Limited, and sometimes conflicting, data exist regarding a related PSPG technology that sets alignment based on criteria different from the mechanical axis of the lower limb [33, 42, 81]. More recent PSPG systems rely on the principle of classic cuts and neutrally aligning each component to its respective mechanical axis. A paired cadaveric study performed by one coauthor (AVL) using postoperative supine CT for analysis demonstrated no outliers for tibial component alignment and 11% (one of nine) versus 33% (three of nine) outliers for the femoral component comparing PSPGs to MI [45, 46].

We examined the relative effectiveness of PSPGs and MI in achieving neutral mechanical axis alignment of the lower extremity and of the femoral and tibial components.

Patients and Methods

Between January 2009 and December 2010, one of the authors (AVL) performed primary TKA in 310 patients using PSPGs (Signature™ Personalized Patient Care System; Biomet Inc, Warsaw, IN) and 875 patients using MI (extramedullary tibial and intramedullary femoral jigs). In addition, another author (JHD) performed primary TKA using PSPGs and MI in 507 and 872 patients, respectively, between June 2008 and December 2009. We considered all patients who had disabling knee arthritis, were at an acceptable medical risk, and failed nonoperative management to be candidates for TKA and evaluated them for applicability of PSPGs. The indications for PSPGs were (1) the ability and willingness to undergo preoperative MRI, (2) the willingness to wait 4 to 6 weeks before surgery, and (3) the acceptance of the relatively new technology. Exclusion criteria for PSPGs were (1) metallic hardware within 10 cm of the knee or prior THA and (2) a prior MRI performed by their primary care physician. At the time of the study, the currently available CT option for preoperative imaging in patients with metallic hardware was not ready. An MRI performed by an outside physician typically was not adequate for PSPG technology since it did not include the knee or hip, and a repeat MRI was not performed. Patients who did not fit the PSPG criteria underwent TKA with MI. The capability for standing AP long-leg radiographs (LLRs) was acquired in January 2010, and the first 105 PSPG patients (January 2010 to December 2010) and 55 MI patients (February 2010 to September 2010) who returned for followup were imaged and included for retrospective analysis. For surgeon JHD, the capability had been established for longer. LLRs from 464 PSPG TKAs (June 2008 to December 2009) and from 100 consecutive MI TKAs (March 2008 to May 2008) were included. We excluded patients with lower limb fractures after TKA or poor-quality LLRs. Both groups were highly representative of each surgeon’s overall patient population. Proceedings were in accordance with the Western Institutional Review Board (Olympia, WA), Protocol Number 20041825, Study Number 1063398.

The surgeons used the PSPG system according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A preoperative MRI was performed and the data sent to Biomet, Inc, which forwarded it to Materialise (Leuven, Belgium), where it was uploaded onto a proprietary software planner. After the surgeons reviewed the templating and alignment of components in multiple planes and approved the plan, rapid-prototyping computer-assisted design/computer-assisted manufacturing technology created PSPG jigs. After exposure of the knee, we carefully positioned PSPG jigs over the articular surfaces, ensuring an accurate fit. Then, guided by the PSPG jig, we placed drill holes and pins in the periarticular bone, which then determined the orientation of standard cutting guides. We then carried out the remainder of the TKA procedure as usual. In all cases, the PSPG could be used, and in no patient was it necessary to convert from PSPG to MI intraoperatively.

Two independent reviewers evaluated LLRs using digital tools. In all patients, we analyzed the relationship of the center of the knee to the OMA of the lower limb. In the subset of patients for AVL, we recorded the additional following measurements: (1) the angle between the tibial (TMA) and femoral mechanical axis (FMA), (2) the angle between the tibial component and the TMA, (3) the angle between the femoral component and the FMA, and (4) the angle between the femoral anatomic axis (FAA) and the FMA. In addition, we used preoperative standard AP weightbearing films of the knee to estimate original anatomic alignment. Both groups were similar in alignment and amount of flexion contracture (Table 2). We randomly selected 20 LLRs for repeat analysis to assess intra- and interobserver reliability, which demonstrated Pearson correlation coefficients of 0.67 to 0.96 and 0.64 to 0.95, respectively.

Table 2.

Summary of preoperative knee measurements*

| Measurement parameter | Patient-specific positioning guides | Manual instrumentation | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of TKAs | 105 | 55 | |

| 5°–10° valgus† | 19 (18%) | 16 (29%) | 0.11 |

| > 10° valgus† | 12 (11%) | 6 (11%) | 1 |

| < 5° valgus† | 74 (71%) | 33 (60%) | 0.18 |

| Outliers ≥ 15° valgus or ≥ 5° varus | 18 (17%) | 11 (20%) | 0.66 |

| Flexion contracture > 10° | 7 (7%) | 5 (9%) | 0.58 |

* For TKAs performed by coauthor AVL; †anatomic alignment of the knee.

The center of the femoral head was determined using digital circles. We defined the center of the ankle as the center of the proximal surface of the talar dome and the OMA as a line connecting these two points. The mediolateral width of the tibial tray was divided into three equal zones and the OMA was assessed as to whether it passed medial to, lateral to, or through the central third. We defined the center of the knee as midway across the proximal resected surface of the tibia and determined the FMA and TMA by connecting this point to the center of the femoral head and the center of the ankle, respectively [60]. The position of the femoral component was defined as a line tangent to the distal aspects of the medial and lateral femoral condyles, and the tibial component as a line along the surface of the tibial tray. The FAA was defined as a line connecting the mediolateral midpoint of the femur at the midshaft and at 10 cm proximal to the knee [60].

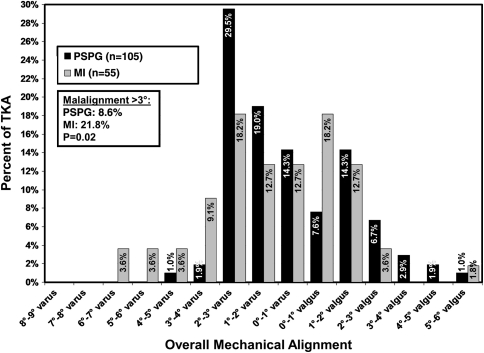

We deemed neutral alignment to be 90° for the individual components and their respective mechanical axes and 180° for the FMA-TMA or hip-knee-ankle (HKA) angle. We measured all angles on the lateral aspect of the intersecting lines, except the FAA-FMA angle, which we measured as the more acute angle. Angles greater than and less than neutral alignment were deemed varus and valgus, respectively. For the HKA angle and both components, we calculated the mean individual patient error from neutral alignment in addition to the all-patient mean angulation since varus and valgus errors offsetting one another would tend to neutralize the latter. The percent of cases in which the HKA angulation was different from neutral in increments of 1° was calculated (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The graph demonstrates the range of deviation from neutral alignment for the HKA angle for the PSPG and MI systems.

We integrated the data for AVL and JHD regarding the distance of OMA from the center of the knee. The overall mean angle and mean individual deviation angles for the tibial component, the femoral component, the HKA, and FAA-FMA between PSPGs and MI were analyzed according to a parametric distribution using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. The proportion of outliers and the relationship of the OMA to the center of the knee between PSPG and MI were analyzed using a chi square test.

Results

The OMA passed through the central third of the knee more often (p < 0.001) with PSPG (88%) than MI (78%). The overall mean HKA angle for PSPG (180.6°) was similar (p = 0.17) to MI (181.1°), but there were fewer (p = 0.018) ± 3° HKA angle outliers with PSPG (9%) than MI (22%). The overall mean tibial (89.9° versus 90.4°) and femoral (90.7° versus 91.3°) component angles were closer (p = 0.005, p < 0.001) to neutral with PSPG compared to MI, but the rate of outliers ± 2° was similar (p = 0.21, p = 0.14) for both the tibia (10% versus 7%) and femur (22% versus 18%). The mean FAA-FMA angles were similar in both groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Alignment of TKA

| Alignment parameter | Patient-specific positioning guides | Manual instrumentation | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central third* | 88% | 78% | < 0.001 |

| Tibial component-TMA angle† | 89.9° | 90.4° | 0.005 |

| Individual tibial component deviation from neutral† | 0.9° | 0.8° | 0.47 |

| Tibial component > 2° outlier† | 10% | 7% | 0.21 |

| Femoral component-FMA angle† | 90.7° | 91.3° | < 0.001 |

| Individual femoral component deviation from neutral† | 1.3° | 1.3° | 0.89 |

| Femoral component > 2° outlier† | 22% | 18% | 0.14 |

| HKA angle† | 180.6° | 181.1° | 0.17 |

| Individual HKA angle deviation from neutral† | 2.0° | 2.1° | 0.5 |

| HKA angle > 3° outlier† | 9% | 22% | 0.018 |

| FAA-FMA angle† | 5.6° | 5.3° | 0.1 |

Values are expressed as means; * includes patients of both JHD and AVL; †includes patients only of AVL; TMA = tibial mechanical axis; FMA = femoral mechanical axis; HKA = hip-knee-ankle; FAA = femoral anatomic axis.

Discussion

PSPG technology for TKA integrates the time-honored principle of mechanical alignment with computer templating and advanced imaging. The majority of literature supports the restoration of a neutral axis as a contributing factor in implant longevity [5, 27, 28, 35, 52, 70]. Intraoperative CAN improves precision and accuracy of alignment compared to MI [54] but is hindered by time-consuming landmark registration, increased operative length, greater cost, risk of pin loosening, and a substantial learning curve [45]. A necessary step in validating the usefulness of any new system such as the PSPG is to establish its equivalence or superiority to existing modalities. We sought to determine its ability to achieve neutral coronal mechanical alignment and compared it to both MI and published reports of CAN.

There are several potential limitations of this study. First, coronal alignment and standing LLRs are the traditional gold standard for assessment of TKA [60]. However, with the recent widespread introduction of three-dimensional imaging and CAN, there is additional focus on sagittal and axial alignment [19, 30, 77, 88]. While postoperative CT is routinely acquired to evaluate component rotation in patients with patellar maltracking issues [6], the costly nature of routine postoperative scanning is prohibitive in large-scale studies. Although sagittal alignment is undoubtedly important in TKA as well, parameters of ideal orientation have been studied far less than in the coronal or axial planes [77]. Second, several recent studies challenged the premise of a coronal safe zone and associated durability. Parratte et al. [67] found mechanical alignment in 292 TKAs did not confer a significant advantage compared to malalignment (± 3°) in 106 cases in terms of survival. In a smaller study, Matziolis et al. [57] reported no difference in patient outcome between aligned TKA and a subset of varus outliers and no revisions in either group. Nevertheless, their findings implied not that coronal alignment was unimportant but rather that assessment of alignment as a dichotomous variable (aligned versus malaligned) was limited and could only serve as a general guideline. Additionally, there was no substantial evidence that any target other than neutral would lead to better results. Likely, the benefits of improved coronal alignment lie along a gradient, and other factors, such as soft tissue balance, if not optimized as well, can overshadow subtle perfections in alignment. Third, reimbursement schematics for TKA have become more parsimonious, and surgeons are challenged with balancing limited financial resources and the near-infinite potential for technologic advancement. The initial capital cost for CAN is approximately $150,000 to $300,000 and, for an even newer technology, robotics, is up to $800,000 [83]. A conservative estimate per procedure for CAN is $1500 [62]. As the number of TKAs performed in the hospital decreases, the expense of CAN substantially increases [62]. Because low- to intermediate-volume surgeons and hospitals perform a sizable proportion of TKAs [38, 79], the PSPG may offer a viable alternative to CAN since it does not incur a substantial initial investment. The costs of a preoperative MRI and a PSPG jig vary considerably by geographic location, and revenue generated by the MRI may offset the expense of PSPGs. While a cost-effective analysis of PSPGs is beyond the scope of this study, the potential savings from reduced instrument tray processing and implant inventory may offset a portion of the added expenses. Furthermore, the actual patient benefit of any technology directly correlates to the surgeon’s proficiency with MI and ability to achieve desired technical outcomes without additional tools. In this study, high-volume surgeons with extensive experience with both PSPGs and MI performed the TKAs. As with any instrumentation system, there is a learning curve with PSPGs, and whether less experienced surgeons are able to integrate its unfamiliar yet intuitive skill set into their armamentarium remains to be seen. Fourth, the objective of this study was not to examine parameters such as patient satisfaction, early functional scores, or length of hospitalization, but there was evidence that improved alignment was associated with better function and quality of life [17, 24, 47]. Indeed, the benchmark of new techniques and technology is not merely achieving a statistically significant difference but also producing a clinically important and tangible improvement in patient outcome. However, demonstrating these effects often requires lengthy followup. With the proliferation of PSPGs by multiple major manufacturers and its popularity among surgeons for several years, published validation of its performance is due. The extent of acceptance of this technology in principle is likely a reflection of not only its compatibility with existing TKA principles but also the recognition of a promising segue between the surgeon and the computer.

We found the use of PSPGs reduced the percentage of HKA outliers at rates superior to many previously reported CAN and nearly all MI rates including the coauthor’s own (Table 1). Outliers for the tibial and femoral component in this study for both PSPG (10%, 22%) and MI (7%, 18%) were lower than those in a meta-analysis for MI (20%, 34%) but higher than those using CAN (5%, 10%) [54]. The mean postoperative FAA-FMA angles for both PSPG and MI fell within the 5° to 7° range typically assumed for TKA performed using intramedullary guides and without preoperative LLRs [22, 25]. Further studies are necessary to examine the effect of compensatory or compounding effects of individual component malalignment on the overall lower limb alignment and on implant function.

While accurate and precise alignment guides are important tools in restoring the proper overall mechanical axis, they are not a substitute for careful preoperative planning, good clinical and intraoperative judgment, appropriate soft tissue balancing, and precise implantation technique. Indeed, there are many variables that affect TKA performance and patient satisfaction, and static coronal alignment is only one measure of technical success by the surgeon. Nevertheless, it is a cornerstone of TKA and carries a weighty import that is backed by an abundance of data. In concert with existing literature, the findings reported here demonstrate the PSPG is effective in achieving overall coronal alignment with accuracy and precision better than MI and, in select regard, comparable to CAN.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joanne B. Adams, BFA, CMI, for her assistance in preparing this manuscript.

Footnotes

One or more authors (JHD, AVL, KRB) are paid consultants for Biomet, Inc (Warsaw, IN). One or more authors (JHD, KRB) are paid consultants for Salient Surgical Technologies (Portsmouth, NH). One or more of the authors (AVL, KRB) receive royalties and institutional research support from Biomet. One author (KRB) receives institutional research support from Salient Surgical Technologies and Angiotech (Vancouver, BC, Canada). One author (AVL) receives royalties from Innomed, Inc (Savannah, GA).

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at The DeClaire Knee and Orthopaedic Institute and Joint Implant Surgeons, Inc.

References

- 1.Anderson KC, Buehler KC, Markel DC. Computer assisted navigation in total knee arthroplasty: comparison with conventional methods. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartel DL, Burstein AH, Santavicca EA, Insall JN. Performance of the tibial component in total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64:1026–1033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bathis H, Perlick L, Tingart M, Luring C, Grifka J. CT-free computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty versus the conventional technique: radiographic results of 100 cases. Orthopedics. 2004;27:476–480. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20040501-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bathis H, Perlick L, Tingart M, Luring C, Zurakowski D, Grifka J. Alignment in total knee arthroplasty: a comparison of computer-assisted surgery with the conventional technique. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:682–687. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B5.14927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berend ME, Ritter MA, Meding JB, Faris PM, Keating EM, Redelman R, Faris GW, Davis KE. Tibial component failure mechanisms in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;428:26–34. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000148578.22729.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger RA, Crossett LS. Determining rotation of the femoral and tibial components in total knee arthroplasty: a computer tomography technique. Operative Tech Orthop. 1998;8:128–133. doi: 10.1016/S1048-6666(98)80022-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertsch C, Holz U, Konrad G, Vakili A, Oberst M. Early clinical outcome after navigated total knee arthroplasty. Comparison with conventional implantation in TKA: a controlled and prospective analysis. Orthopade. 2007;36:739–745. doi: 10.1007/s00132-007-1122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biasca N, Wirth S, Bungartz M. Mechanical accuracy of navigated minimally invasive total knee arthroplasty (MIS TKA) Knee. 2009;16:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohling U, Schamberger H, Grittner U, Scholz J. Computerised and technical navigation in total knee-arthroplasty. J Orthop Traumatol. 2005;6:69–75. doi: 10.1007/s10195-005-0084-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonutti P, Dethmers D, Stiehl JB. Case report: femoral shaft fracture resulting from femoral tracker placement in navigated TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:1499–1502. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0150-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonutti PM, Dethmers D, Ulrich SD, Seyler TM, Mont MA. Computer navigation-assisted versus minimally invasive TKA: benefits and drawbacks. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2756–2762. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0429-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonutti PM, Dethmers DA, McGrath MS, Ulrich SD, Mont MA. Navigation did not improve the precision of minimally invasive knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2730–2735. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0359-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang CW, Yang CY. Kinematic navigation in total knee replacement-experience from the first 50 cases. J Formos Med Assoc. 2006;105:468–474. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60186-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chauhan S, Clark G, Lloyd S, Scott R, Breidahl W, Sikorski J. Computer-assisted total knee replacement: a controlled cadaver study using a multi-parameter quantitative CT assessment of alignment (the Perth CT protocol) J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:818–823. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B6.15456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheung KW, Chiu KH. Imageless computer navigation in total knee arthroplasty. Hong Kong Med J. 2009;15:353–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chin PL, Yang KY, Yeo SJ, Lo NN. Randomized control trial comparing radiographic total knee arthroplasty implant placement using computer navigation versus conventional technique. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:618–626. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choong PF, Dowsey MM, Stoney JD. Does accurate anatomical alignment result in better function and quality of life? Comparing conventional and computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:560–569. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chotanaphuti T, Ongnamthip P, Teeraleekul K, Kraturerk C. Comparative study between computer assisted-navigation and conventional technique in minimally invasive surgery total knee arthroplasty, prospective control study. J Med Assoc Thai. 2008;91:1382–1388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung BJ, Kang YG, Chang CB, Kim SJ, Kim TK. Differences between sagittal femoral mechanical and distal reference axes should be considered in navigated TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:2403–2413. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0762-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Confalonieri N, Manzotti A, Pullen C, Ragone V. Computer-assisted technique versus intramedullary and extramedullary alignment systems in total knee replacement: a radiological comparison. Acta Orthop Belg. 2005;71:703–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daubresse F, Vajeu C, Loquet J. Total knee arthroplasty with conventional or navigated technique: comparison of the learning curves in a community hospital. Acta Orthop Belg. 2005;71:710–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dennis DA, Channer M, Susman MH, Stringer EA. Intramedullary versus extramedullary tibial alignment systems in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1993;8:43–47. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(06)80106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dutton AQ, Yeo SJ, Yang KY, Lo NN, Chia KU, Chong HC. Computer-assisted minimally invasive total knee arthroplasty compared with standard total knee arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:2–9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ek ET, Dowsey MM, Tse LF, Riazi A, Love BR, Stoney JD, Choong PF. Comparison of functional and radiological outcomes after computer-assisted versus conventional total knee arthroplasty: a matched-control retrospective study. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2008;16:192–196. doi: 10.1177/230949900801600213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engh GA, Peterson TL. Comparative experience with intramedullary and extramedullary alignment in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1990;5:1–8. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(06)80002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ensini A, Catani F, Leardini A, Romagnoli M, Giannini S. Alignments and clinical results in conventional and navigated total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;457:156–162. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e3180316c92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fang DM, Ritter MA, Davis KE. Coronal alignment in total knee arthroplasty: just how important is it? J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Green GV, Berend KR, Berend ME, Glisson RR, Vail TP. The effects of varus tibial alignment on proximal tibial surface strain in total knee arthroplasty: the posteromedial hot spot. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17:1033–1039. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.35796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haaker RG, Stockheim M, Kamp M, Proff G, Breitenfelder J, Ottersbach A. Computer-assisted navigation increases precision of component placement in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;433:152–159. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000150564.31880.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han HS, Seong SC, Lee S, Lee MC. Rotational alignment of femoral components in total knee arthroplasty: nonimage-based navigation system versus conventional technique. Available at: https://www.orthosupersite.com/print.aspx?rid=18743. Accessed July 5, 2011. [PubMed]

- 31.Hasegawa M, Yoshida K, Wakabayashi H, Sudo A. Minimally invasive total knee arthroplasty: comparison of jig-based technique versus computer navigation for clinical and alignment outcome. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19:904–910. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1253-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hernandez-Vaquero D, Suarez-Vazquez A, Sandoval-Garcia MA, Noriega-Fernandez A. Computer assistance increases precision of component placement in total knee arthroplasty with articular deformity. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:1237–1241. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1175-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howell SM, Kuznik K, Hull ML, Siston RA. Results of an initial experience with custom-fit positioning total knee arthroplasty in a series of 48 patients. Orthopedics. 2008;31:857–863. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20080901-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishida K, Matsumoto T, Tsumura N, Kubo S, Kitagawa A, Chin T, Iguchi T, Kurosaka M, Kuroda R. Mid-term outcomes of computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19:1107–1112. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1361-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeffery RS, Morris RW, Denham RA. Coronal alignment after total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:709–714. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B5.1894655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jenny JY, Boeri C. Computer-assisted implantation of total knee prostheses: a case-control comparative study with classical instrumentation. Comput Aided Surg. 2001;6:217–220. doi: 10.3109/10929080109146086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jenny JY, Clemens U, Kohler S, Kiefer H, Konermann W, Miehlke RK. Consistency of implantation of a total knee arthroplasty with a non-image-based navigation system: a case-control study of 235 cases compared with 235 conventionally implanted prostheses. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:832–839. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katz JN, Barrett J, Mahomed NN, Baron JA, Wright RJ, Losina E. Association between hospital and surgeon procedure volume and the outcomes of total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:1909–1916. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B7.14358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim SJ, MacDonald M, Hernandez J, Wixson RL. Computer assisted navigation in total knee arthroplasty: improved coronal alignment. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim YH, Kim JS, Choi Y, Kwon OR. Computer-assisted surgical navigation does not improve the alignment and orientation of the components in total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:14–19. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim YH, Kim JS, Yoon SH. Alignment and orientation of the components in total knee replacement with and without navigation support: a prospective, randomised study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:471–476. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B4.18878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klatt BA, Goyal N, Austin MS, Hozack WJ. Custom-fit total knee arthroplasty (OtisKnee) results in malalignment. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23:26–29. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee DH, Park JH, Song DI, Padhy D, Jeong WK, Han SB. Accuracy of soft tissue balancing in TKA: comparison between navigation-assisted gap balancing and conventional measured resection. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18:381–387. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0983-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liau JJ, Cheng CK, Huang CH, Lo WH. The effect of malalignment on stresses in polyethylene component of total knee prostheses––a finite element analysis. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2002;17:140–146. doi: 10.1016/S0268-0033(01)00109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lombardi AV, Jr, Berend KR, Adams JB. Patient-specific approach in total knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2008;31:927–930. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20080901-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lombardi AV Jr, Emerson RH Jr, Pietrzak WS. Signature Personalized Patient Care for total knee arthroplasty: a mechanical alignment cadaveric study. Internal Study. 2008:1–3.

- 47.Longstaff LM, Sloan K, Stamp N, Scaddan M, Beaver R. Good alignment after total knee arthroplasty leads to faster rehabilitation and better function. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:570–578. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lotke PA, Ecker ML. Influence of positioning of prosthesis in total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59:77–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luring C, Beckmann J, Haibock P, Perlick L, Grifka J, Tingart M. Minimal invasive and computer assisted total knee replacement compared with the conventional technique: a prospective, randomised trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16:928–934. doi: 10.1007/s00167-008-0582-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lutzner J, Krummenauer F, Wolf C, Gunther KP, Kirschner S. Computer-assisted and conventional total knee replacement: a comparative, prospective, randomised study with radiological and CT evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:1039–1044. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B8.20553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Macule-Beneyto F, Hernandez-Vaquero D, Segur-Vilalta JM, Colomina-Rodriguez R, Hinarejos-Gomez P, Garcia-Forcada I, Seral Garcia B. Navigation in total knee arthroplasty: a multicenter study. Int Orthop. 2006;30:536–540. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0126-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mahoney OM. The role of alignment in TKR survivorship. Presented at Orthopedics Today Hawaii 2010. January 10–13, 2010. Kohala Coast, HI.

- 53.Martin A, Wohlgenannt O, Prenn M, Oelsch C, Strempel A. Imageless navigation for TKA increases implantation accuracy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;460:178–184. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31804ea45f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mason JB, Fehring TK, Estok R, Banel D, Fahrbach K. Meta-analysis of alignment outcomes in computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty surgery. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:1097–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Massai F, Conteduca F, Vadala A, Iorio R, Basiglini L, Ferretti A. Tibial stress fracture after computer-navigated total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Traumatol. 2010;11:123–127. doi: 10.1007/s10195-010-0096-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matsumoto T, Tsumura N, Kurosaka M, Muratsu H, Kuroda R, Ishimoto K, Tsujimoto K, Shiba R, Yoshiya S. Prosthetic alignment and sizing in computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2004;28:282–285. doi: 10.1007/s00264-004-0562-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matziolis G, Adam J, Perka C. Varus malalignment has no influence on clinical outcome in midterm follow-up after total knee replacement. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130:1487–1491. doi: 10.1007/s00402-010-1064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matziolis G, Krocker D, Weiss U, Tohtz S, Perka C. A prospective, randomized study of computer-assisted and conventional total knee arthroplasty: three-dimensional evaluation of implant alignment and rotation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:236–243. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mizu-uchi H, Matsuda S, Miura H, Okazaki K, Akasaki Y, Iwamoto Y. The evaluation of post-operative alignment in total knee replacement using a CT-based navigation system. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:1025–1031. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B8.20265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moreland JR, Bassett LW, Hanker GJ. Radiographic analysis of the axial alignment of the lower extremity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69:745–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mullaji A, Kanna R, Marawar S, Kohli A, Sharma A. Comparison of limb and component alignment using computer-assisted navigation versus image intensifier-guided conventional total knee arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized, single-surgeon study of 467 knees. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:953–959. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Novak EJ, Silverstein MD, Bozic KJ. The cost-effectiveness of computer-assisted navigation in total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:2389–2397. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oberst M, Bertsch C, Konrad G, Lahm A, Holz U. CT analysis after navigated versus conventional implantation of TKA. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128:561–566. doi: 10.1007/s00402-007-0486-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oberst M, Bertsch C, Wurstlin S, Holz U. CT analysis of leg alignment after conventional vs. navigated knee prosthesis implantation: initial results of a controlled, prospective and randomized study [in German] Unfallchirurg. 2003;106:941–948. doi: 10.1007/s00113-003-0686-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pang CH, Chan WL, Yen CH, Cheng SC, Woo SB, Choi ST, Hui WK, Mak KH. Comparison of total knee arthroplasty using computer-assisted navigation versus conventional guiding systems: a prospective study. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2009;17:170–173. doi: 10.1177/230949900901700209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Park SE, Lee CT. Comparison of robotic-assisted and conventional manual implantation of a primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:1054–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Parratte S, Pagnano MW, Trousdale RT, Berry DJ. Effect of postoperative mechanical axis alignment on the fifteen-year survival of modern, cemented total knee replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2143–2149. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Perlick L, Bathis H, Lerch K, Luring C, Tingart M, Grifka J. [Navigated implantation of total knee endoprostheses in secondary knee osteoarthritis of rheumatoid arthritis patients as compared to conventional technique] [in German] Z Rheumatol. 2004;63:140–146. doi: 10.1007/s00393-004-0569-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Perlick L, Bathis H, Tingart M, Perlick C, Grifka J. Navigation in total-knee arthroplasty: CT-based implantation compared with the conventional technique. Acta Orthop Scand. 2004;75:464–470. doi: 10.1080/00016470410001259-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ritter MA, Faris PM, Keating EM, Meding JB. Postoperative alignment of total knee replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;299:153–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rosenberger R, Hoser C, Quirbach S, Attal R, Hennerbichler A, Fink C. Improved accuracy of component alignment with the implementation of image-free navigation in total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16:249–257. doi: 10.1007/s00167-007-0420-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Saragaglia D, Picard F, Chaussard C, Montbarbon E, Leitner F, Cinquin P. [Computer-assisted knee arthroplasty: comparison with a conventional procedure: results of 50 cases in a prospective randomized study] [in French] Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2001;87:18–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schmitt J, Hauk C, Kienapfel H, Pfeiffer M, Efe T, Fuchs-Winkelmann S, Heyse TJ. Navigation of total knee arthroplasty: rotation of components and clinical results in a prospectively randomized study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Seon JK, Park SJ, Lee KB, Li G, Kozanek M, Song EK. Functional comparison of total knee arthroplasty performed with and without a navigation system. Int Orthop. 2009;33:987–990. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0594-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Seon JK, Song EK. Navigation-assisted less invasive total knee arthroplasty compared with conventional total knee arthroplasty: a randomized prospective trial. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:777–782. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Seon JK, Song EK, Yoon TR, Park SJ, Bae BH, Cho SG. Comparison of functional results with navigation-assisted minimally invasive and conventional techniques in bilateral total knee arthroplasty. Comput Aided Surg. 2007;12:189–193. doi: 10.3109/10929080701311861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sikorski JM. Alignment in total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:1121–1127. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B9.20793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Skowronski J, Bielecki M, Hermanowicz K, Skowronski R. The radiological outcomes of total knee arthroplasty using computer assisted navigation ORTHOPILOT. Chir Narzadow Ruchu Ortop Pol. 2005;70:5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.SooHoo NF, Lieberman JR, Ko CY, Zingmond DS. Factors predicting complication rates following total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:480–485. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sparmann M, Wolke B, Czupalla H, Banzer D, Zink A. Positioning of total knee arthroplasty with and without navigation support: a prospective, randomised study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:830–835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Spencer BA, Mont MA, McGrath MS, Boyd B, Mitrick MF. Initial experience with custom-fit total knee replacement: intra-operative events and long-leg coronal alignment. Int Orthop. 2009;33:1571–1575. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0693-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stulberg SD, Picard F, Saragaglia D. Computer-assisted total knee replacement arthroplasty. Oper Tech Orthop. 2000;10:25–39. doi: 10.1016/S1048-6666(00)80040-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Swank ML, Alkire M, Conditt M, Lonner JH. Technology and cost-effectiveness in knee arthroplasty: computer navigation and robotics. Am J Orthop. 2009;38:32–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tew M, Waugh W. Tibiofemoral alignment and the results of knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1985;67:551–556. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.67B4.4030849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tingart M, Luring C, Bathis H, Beckmann J, Grifka J, Perlick L. Computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty versus the conventional technique: how precise is navigation in clinical routine? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16:44–50. doi: 10.1007/s00167-007-0399-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Victor J, Hoste D. Image-based computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty leads to lower variability in coronal alignment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;428:131–139. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000147710.69612.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yau WP, Chiu KY, Zuo JL, Tang WM, Ng TP. Computer navigation did not improve alignment in a lower-volume total knee practice. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:935–945. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0144-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yehyawi TM, Callaghan JJ, Pedersen DR, O’Rourke MR, Liu SS. Variances in sagittal femoral shaft bowing in patients undergoing TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;464:99–104. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e318157e4a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zorman D, Etuin P, Jennart H, Scipioni D, Devos S. Computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty: comparative results in a preliminary series of 72 cases. Acta Orthop Belg. 2005;71:602–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]