Abstract

Background

The outcome after a repeat hepatectomy for recurrent colorectal liver metastases (CLM) is not well defined. The present study examined the morbidity, mortality and long-term survivals after a repeat hepatectomy for recurrent CLM.

Methods

Data on patients who underwent surgery for recurrent CLM between 1993 and 2009 were retrospectively evaluated. Patients who underwent radiofrequency ablation at the time of first treatment or at recurrence of CLM were excluded.

Results

Forty-three patients underwent a repeat hepatectomy for recurrent CLM. At the time of recurrence, patients had a median of 1 (1–3) lesions and the median tumour size was 2 (0.5–8.7) cm. The post-operative morbidity and mortality rates were 12% and 0%, respectively. After a median follow-up of 33 months from a repeat hepatectomy, 5-year overall and progression-free survival rates were 73% and 22%, respectively. Using multivariate analysis, the largest initial CLM ≥5 cm and positive surgical margins at initial resection were independently associated with a worse survival after surgery for recurrent CLM. Positive surgical margins at repeat hepatectomy were a predictive factor for an increased risk of further recurrence.

Discussion

A repeat hepatectomy for recurrent CLM was associated with excellent survival, low morbidity and no mortality. Surgeon-controlled variables, including margin-negative resection at first and repeat hepatectomy, contribute to good oncological outcome.

Keywords: hepatic metastases, liver resection, surgical margins

Introduction

Liver resection has been shown to effectively prolong survival in patients with colorectal liver metastases (CLM) and is widely accepted as the best treatment option in patients with resectable disease.1,2 Although 5-year overall survival rates can reach 58%,1,2 up to 57% of patients develop recurrence after resection of CLM.3 The liver is the most common site of recurrence after resection of CLM; most recurrences present as new lesions, whereas local recurrences at the surgical margin are uncommon even in cases of microscopic invasion at the margin.4–6 In selected patients with liver-only recurrence, a repeat hepatectomy has been reported to be feasible and associated with good outcomes.7–12 In particular, a repeat hepatectomy can be associated with prolonged survival, with 5-year survival rates as high as 85%.9,10,13 However, although previous studies have evaluated factors associated with favourable outcome after a repeat hepatectomy,12 it is still not well defined whether prolonged survival is the result of oncological factors only or of surgeon-controlled factors such as completeness of resection.14

The present study examined the post-operative and oncological outcomes of patients who underwent a repeat hepatectomy for recurrent CLM. Predictive factors associated with overall and progression-free survival in patients who underwent surgical treatment of recurrent CLM were investigated.

Patients and methods

Study inclusion criteria

Data on 115 consecutive patients who underwent a laparotomy for recurrent CLM after initial resection or radiofrequency ablation (RFA) at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center between December 1993 and December 2009 were retrospectively evaluated. For the present study, only patients who underwent a repeat hepatectomy were selected. Patients who had RFA at the time of first surgery or as a treatment of recurrent CLM were excluded. All patients had pathologically proven initial and recurrent CLM. The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Diagnosis of recurrent CLM and pre-operative assessment

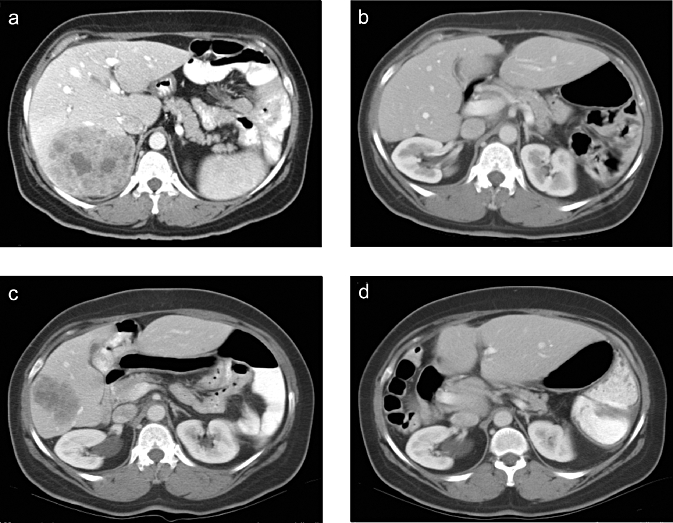

The diagnosis of recurrent CLM was made using helical-computed tomography (CT) with liver protocol (rapid injection of 150 ml of intravenous contrast material with image reconstruction of 2.5–5 mm through the liver) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Figure 1 shows abdominal CT images of a patient before and after the first hepatectomy for CLM and a repeat hepatectomy for recurrent CLM. Recurrent CLM was defined as local recurrence when it occurred at the surgical margin of a prior resection,4 while all other relapses in the liver were defined as new lesions. Beginning in 1998, 9-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) was used in the majority of patients to rule out extrahepatic disease and to confirm the metastatic nature of atypical lesions.15 When recurrent CLM was suspected but not confirmed after the initial imaging work-up, a new evaluation including CT and FDG-PET was generally repeated approximately 1 month later to detect additional changes. A tumour biopsy was performed when indicated to secure the diagnosis of recurrence. When the diagnosis of recurrence was confirmed, the patient's physical status was carefully evaluated. In most patients, the decision whether surgery for recurrent CLM was indicated was made during a multidisciplinary meeting that included hepatobiliary surgeons, imaging radiologists, interventional radiologists and medical oncologists. The decision whether to administer pre-operative chemotherapy was based on the extent of recurrent CLM, the presence of extrahepatic disease, and previous response to and toxic effects of chemotherapy, at the multidisciplinary team's discretion.

Figure 1.

Large solitary colorectal liver metastasis (CLM) involving segments VI, VII and VIII (a) at diagnosis, (b) 3 months after resection (right hepatectomy), (c) at the time of recurrence and (d) 20 months after a repeat hepatectomy, showing no evidence of disease

Surgical procedure

Liver resections were performed only with curative intent, i.e. only if it was believed that all tumour deposits could be completely resected. During a laparotomy, the peritoneal cavity was inspected to rule out extrahepatic recurrence. Palpation and intra-operative ultrasonography were carried out in all patients to better define the location of the metastases in the liver and their relationship with portal pedicles and hepatic veins. A parenchymal transection was performed using an ultrasonic dissector, and haemostasis was achieved with a saline-linked cautery as previously described.16,17 A major hepatectomy was defined as a liver resection comprising three or more contiguous liver segments. Consequently, a minor hepatectomy was defined as resection of less than three liver segments.

Post-operative period

Post-operative morbidity and 30-day and 90-day mortality rates were studied. Major post-operative complications were defined as complications of grade 3 or higher in the Clavien–Dindo classification (i.e. necessitating a surgical, endoscopic or radiological procedure).18 Post-operative liver insufficiency was defined as a post-operative bilirubin peak level ≥7 mg/dl.19 All resection specimens were histologically evaluated and the surgical margins were examined for tumour cell invasion. The margin width was defined as the distance between the tumour and the closest inked section as previously described.4 R0 resection was defined as a complete tumour resection with surgical margins microscopically negative for tumour cells.

After a hepatectomy, the use of post-operative chemotherapy was considered by the multidisciplinary team of oncologists and surgeons; factors taken into account included the completeness of the resection, the morphological and pathological response to pre-operative chemotherapy, the extent and the toxicity of previous chemotherapy, if any. In patients with a further liver recurrence after a repeat hepatectomy, the feasibility of a third liver resection versus the utility of other interventions was determined on the basis of the extent of prior resections, extent of recurrent disease, and the volume and function of the remnant liver. No fixed number or size criteria were used to determine resectability at the first or any subsequent liver resection.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative and qualitative variables were expressed as median (range) and frequency. Comparisons between groups were analysed with the χ2- or Fisher's exact test for proportions and the Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables as appropriate. Overall and progression-free survival rates were calculated from the time of a repeat hepatectomy to the date of last follow-up and date of recurrence, respectively; they were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using log-rank tests. For detection of factors associated with survival in patients who underwent a repeat hepatectomy for recurrent CLM, univariate analysis was used to examine the relationship between survival and the following variables: location of the primary tumour (colon vs. rectum); status of regional lymph nodes at the time of diagnosis of the primary tumour (positive vs. negative); status of the surgical margins on microscopic analysis at the initial and repeat hepatectomy (positive for tumour cells vs. negative); timing of the detection of the initial CLM (synchronous [present at the time of resection of the primary tumour] vs. metachronous); the number of initial CLM (single vs. multiple); size of the largest initial CLM (<5 vs. ≥5 cm); time to recurrence (≥12 vs. <12 months); type of recurrence (local vs. new lesion); carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) plasma level at the time of the resection of the recurrent CLM (≤5 vs. >5 ng/ml); number of recurrent CLM (single vs. multiple); size of the largest recurrent CLM (<3 vs. ≥3 cm); extent of the resection (major vs. minor); extension of the CLM resection to an adjacent organ (yes vs. no); intra-operative blood transfusion (required vs. not); post-operative complications (present vs. absent); and post-operative chemotherapy for the recurrent CLM (administered vs. not). All variables associated with survival with a P-value less than 0.15 in univariate proportional hazards models were subsequently entered into a Cox multivariate regression model with backward elimination. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical software package SPSS version 17.2 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

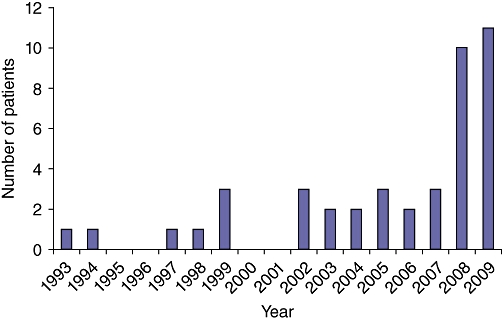

Among the 115 patients who had surgical treatment of recurrent CLM between 1993 and 2009, 43 underwent a repeat hepatectomy for recurrent CLM after an initial liver resection and fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The number of patients who were treated with a repeat hepatectomy increased over time. Most repeat hepatectomies were performed in 2008 and 2009 (Fig. 2). Pre-operative characteristics of these 43 patients are summarized in Table 1. Nineteen patients were older than 55 years and 31 patients were male. At the time of initial diagnosis of CLM, 19 patients had multiple CLM and 7 patients had tumours larger than or equal to 5 cm. At first treatment of CLM, 24 patients underwent a major hepatectomy and 19 patients were treated with minor liver resection. The majority of patients (24/43) developed recurrent CLM within 12 months after the first hepatectomy for CLM. At the time of recurrence, patients had limited recurrent disease in the liver: 36 patients had solitary liver recurrence and 31 patients had a maximum tumour size <3 cm. Initially treated and recurrent CLM had similar median sizes (2 [0.5–13] vs. 2 [0.5–8.7] cm, respectively; P = 0.243), but the number of recurrent lesions was lower than the number of CLM resected at the initial hepatectomy (1 [1–3] vs. 1 [1–10], respectively; P = 0.002).

Figure 2.

Time evolution of the number of patients undergoing a repeat hepatectomy for recurrent colorectal liver metastasis (CLM) at the MD Anderson Cancer Center

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics and outcomes of patients who underwent a repeat hepatectomy for recurrent colorectal liver metastasis (CLM)

| Characteristic | Number (%) of patients (n = 43) |

|---|---|

| Initial diagnosis of CLM | |

| Median age (range) | 55 (32–74) years |

| Gender (M/F) | 31/12 |

| Median body mass index (range) | 27 (19–37) kg/m2 |

| Rectal primary tumour | 17 (40) |

| Node-positive primary tumour | 36 (84) |

| Positive surgical margin | 4 (9) |

| Liver metastases | |

| Synchronous (vs. metachronous) | 24 (56) |

| Median number of CLM (range) | 1 (1–10) |

| Median maximum CLM diameter (range) | 2 (0.5–13) cm |

| Recurrent CLM | |

| Median time to recurrence after first hepatectomy (range) | 11 (1–147) months |

| Liver metastases | |

| Median number of CLM (range) | 1 (1–3) |

| Median maximum CLM diameter (range) | 2 (0.5–8.7) cm |

| New lesions | 42 (98) |

| Local recurrence | 1 (2) |

| Pre-operative chemotherapy | 19 (44) |

| Post-operative chemotherapy | 27 (63) |

| Type of resection | |

| Major liver resection (≥3 liver segments) | 5 (12) |

| Resection of CLM extension to adjacent organ(s) | 2 (5) |

| Positive surgical margin | 6 (14) |

| Median CEA before a repeat hepatectomy | 2 (1−63) ng/ml |

| Median estimated blood loss (range) | 250 (50–1100) ml |

| Transfusion requirement | 2 (5) |

| Median operating time (range) | 183 (63–546) min |

| Post-operative mortality | 0 |

| Post-operative morbidity | 5 (12) |

| Major complication ratea | 0 |

| Median length of hospital stay (range) | 6 (3–10) days |

Values in the table are the number of patients (percentage) unless otherwise indicated.

Major complication was defined as requiring surgical, endoscopical or radiological intervention.

CLM, colorectal liver metastasis: CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen.

Intra-operative and post-operative characteristics

Intra-operative and post-operative characteristics for a repeat hepatectomy are summarized in Table 1. Five patients had a major liver resection, including two extended left hepatectomies, two right hepatectomies and one extended right hepatectomy. All other patients had minor resections. Five patients developed post-operative complications after a repeat hepatectomy including pleuropulmonary complications (2), superficial wound infections (2), and atrial fibrillation (1); none had a post-operative liver insufficiency or a major complication requiring re-operation or percutaneous drain placement. Post-operative 30-day and 90-day mortality rates were both 0%.

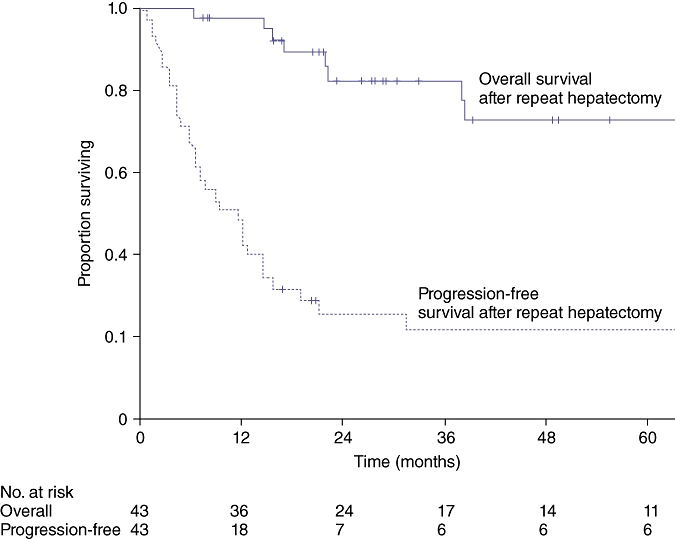

Survival

At a median (range) follow-up interval of 33 (6–149) months after a repeat hepatectomy, 3- and 5-year overall survival rates were 82% and 73%, respectively. Three- and 5-year progression-free survival rates were 22% and 22%, respectively (Fig. 3). Thirty patients developed further recurrence, and the median time to recurrence after a repeat hepatectomy was 7 (1–32) months. Recurrent lesions were identified in the liver (15), lung (9), peritoneum (4), lymph nodes (3), and bones (1). Two patients had simultaneous recurrences in the liver and lung. Ten patients received local therapy for their further recurrence: five were treated with a third hepatectomy, three with RFA, and two with resection of lung metastases.

Figure 3.

Overall and progression-free survival in 43 patients who underwent a repeat hepatectomy for recurrent colorectal liver metastasis (CLM)

Predictors of outcome

In univariate analysis, the largest initial CLM ≥5 cm (P = 0.004) and positive surgical margins at initial resection (P = 0.039) were associated with worse overall survival after resection of recurrent CLM. In multivariate analysis, both the largest initial CLM ≥5 cm (hazard ratio [HR] = 12.36, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.12–72.03, P = 0.005) and positive surgical margins at initial resection (HR = 9.55, 95% CI = 1.59–57.38, P = 0.014) were independently associated with worse survival after surgery for recurrent CLM (Table 2). Positive surgical margins at repeat hepatectomy predicted progression-free survival in univariate analysis (P = 0.018) and was the only factor identified in multivariate analysis to be independently associated with an increased risk of further recurrence (HR = 3.00, 95% CI = 1.15–7.86, P = 0.025) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with overall survival in patients who underwent a repeat hepatectomy for recurrent CLM

| Predictor of overall survival | n (%) | 5-year survival (%) | Univariate analysis P-value | Multivariate analysisa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | HR (95% CI)b | ||||

| Initial diagnosis of CLM | |||||

| Primary tumour | 0.379 | ||||

| Colon | 26 (60) | 86 | |||

| Rectum | 17 (40) | 58 | |||

| Regional lymph nodes for the primary tumour | 0.996 | ||||

| Positive | 36 (84) | 72 | |||

| Negative | 7 (1) | 80 | |||

| Surgical margin | 0.039 | 0.014 | 9.55 (1.59−57.38) | ||

| Positive | 4 (9) | 38 | |||

| Negative | 39 (91) | 76 | |||

| Timing of detection of CLM | 0.732 | ||||

| Synchronous | 24 (56) | 75 | |||

| Metachronous | 19 (44) | 71 | |||

| Number of CLM | 0.321 | ||||

| Single | 24 (56) | 82 | |||

| Multiple | 19 (44) | 59 | |||

| Size of the largest CLM | 0.004 | 0.005 | 12.36 (2.12−72.03) | ||

| ≥5 cm | 7 (16) | 24 | |||

| <5 cm | 36 (84) | 84 | |||

| Recurrent CLM | |||||

| Time to recurrence after the first hepatectomy | 0.221 | ||||

| <12 months | 24 (56) | 66 | |||

| ≥12 months | 19 (44) | 82 | |||

| Type of recurrence | 0.398 | ||||

| Local | 1 (2) | 0 | |||

| New lesion | 42 (98) | 72 | |||

| CEA plasma level | 0.755 | ||||

| >5 ng/ml | 13 (30) | 74 | |||

| ≤5 ng/ml | 30 (70) | 68 | |||

| Number of CLM | 0.136 | 0.921 | 1.10 (0.18−6.74) | ||

| Single | 36 (84) | 79 | |||

| Multiple | 7 (16) | 48 | |||

| Size of the largest CLM | 0.890 | ||||

| ≥3 cm | 12 (28) | 72 | |||

| <3 cm | 31 (72) | 80 | |||

| Extent of resection | 0.318 | ||||

| Major | 5 (12) | 70 | |||

| Minor | 38 (88) | 100 | |||

| Resection of the CLM extension to adjacent organ(s) | 0.413 | ||||

| Yes | 2 (5) | 50 | |||

| No | 41 (95) | 74 | |||

| Blood transfusion | 0.230 | ||||

| Yes | 2 (5) | 0 | |||

| No | 41 (95) | 77 | |||

| Post-operative complication | 0.658 | ||||

| Yes | 5 (12) | 75 | |||

| No | 38 (88) | 74 | |||

| Surgical margin | 0.969 | ||||

| Positive | 6 (14) | 83 | |||

| Negative | 37 (86) | 73 | |||

| Post-operative chemotherapy | 0.453 | ||||

| Yes | 27 (63) | 57 | |||

| No | 16 (37) | 87 | |||

Cox's regression multivariate analysis included all variables with a P-value less than 0.15 in univariate analysis.

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

CLM, colorectal liver metastasis; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with progression-free survival in patients who underwent a repeat hepatectomy for recurrent CLM

| Predictor of overall survival | n (%) | 5-year survival (%) | Univariate analysis P-value | Multivariate analysisa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | HR (95% CI)b | ||||

| Initial diagnosis of CLM | |||||

| Primary tumour | 0.666 | ||||

| Colon | 26 (60) | 23 | |||

| Rectum | 17 (40) | 21 | |||

| Regional lymph nodes for the primary tumour | 0.912 | ||||

| Positive | 36 (84) | 22 | |||

| Negative | 7 (16) | 30 | |||

| Surgical margin | 0.583 | ||||

| Positive | 4 (9) | 0 | |||

| Negative | 39 (91) | 24 | |||

| Timing of CLM | 0.354 | ||||

| Synchronous | 24 (56) | 22 | |||

| Metachronous | 19 (44) | 25 | |||

| Number of CLM | 0.159 | ||||

| Single | 24 (56) | 25 | |||

| Multiple | 19 (44) | 17 | |||

| Size of the largest CLM | 0.597 | ||||

| ≥5 cm | 7 (16) | 29 | |||

| <5 cm | 36 (84) | 21 | |||

| Recurrent of CLM | |||||

| Time to recurrence after the first hepatectomy | 0.489 | ||||

| <12 months | 24 (56) | 22 | |||

| ≥12 months | 19 (44) | 22 | |||

| Type of recurrence | 0.689 | ||||

| Local | 1 (2) | 0 | |||

| New lesion | 42 (98) | 23 | |||

| CEA plasma level | 0.144 | 0.058 | 2.63 (0.97−7.13) | ||

| >5 ng/ml | 13 (30) | 1 | |||

| ≤5 ng/ml | 30 (70) | 31 | |||

| Number of CLM | 0.766 | ||||

| Single | 36 (84) | 22 | |||

| Multiple | 7 (16) | 18 | |||

| Size of the largest CLM | 0.561 | ||||

| ≥3 cm | 12 (28) | 25 | |||

| <3 cm | 31 (72) | 22 | |||

| Extent of resection | 0.443 | ||||

| Major | 5 (12) | 33 | |||

| Minor | 38 (88) | 20 | |||

| Resection of CLM extension to adjacent organ(s) | 0.549 | ||||

| Yes | 2 (5) | 50 | |||

| No | 41 (95) | 20 | |||

| Blood transfusion | 0.815 | ||||

| Yes | 2 (5) | 0 | |||

| No | 41 (95) | 22 | |||

| Post-operative complication | 0.531 | ||||

| Yes | 5 (12) | 40 | |||

| No | 38 (88) | 18 | |||

| Surgical margin | 0.018 | 0.025 | 3.00 (1.15−7.86) | ||

| Positive | 6 (14) | 0 | |||

| Negative | 37 (86) | 26 | |||

| Post-operative chemotherapy | 0.250 | ||||

| Yes | 27 (63) | 17 | |||

| No | 16 (37) | 33 | |||

Cox's regression multivariate analysis included all variables with a P-value less than 0.15 in univariate analysis.

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

CLM, colorectal liver metastasis; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen.

Discussion

The present study confirms that a repeat hepatectomy for recurrence of CLM after a first resection is feasible and safe and is associated with prolonged survival in selected patients. In this study, a 73% 5-year overall survival rate was observed. In addition there were no major complications or post-operative mortality. These excellent results were achieved in spite of the fact that 26 out of 43 patients had synchronous CLM, a factor associated with a high risk for poor outcome.20,21 Previous studies suggested the feasibility of this approach,8,10,12,22 but the reality is that a repeat hepatectomy creates a number of technical challenges10 combining the difficulties associated with surgery on the often fragile, regenerative liver and those of intra-abdominal adhesions between the liver and regional structures, including the diaphragm, that are related to first resection. During the past decade, however, the safety of a liver resection has improved and, an increasing number of patients with hepatic malignancies are treated surgically. In spite of this increase in re-resection over time, morbidity remains low, and major morbidity and mortality can be minimized in carefully selected patients. Improvements in surgical technique and peri-operative care probably contribute to these results.16,23 The wide use of pre-operative chemotherapy in the study patients (19/43), which has been previously associated with increased post-operative morbidity,24–26 did not have a negative impact on the surgical results, underlining the feasibility of this approach in this subset of patients.

This is a timely discussion, because RFA has been proposed as an alternative for the treatment of recurrent CLM27,28 because of its low morbidity and mortality rates. In the current series, the influence of post-operative morbidity on long-term outcome cannot be used as an argument to recommend RFA rather than resection as morbidity was low. Therefore re-resection should be considered for the treatment of recurrent CLM based on the established long-term results of liver resection1,29 and the excellent overall survival achieved in the present study. However, a more comprehensive comparison between RFA and surgery is required so that definitive conclusions regarding the local recurrence rate after treatment of recurrent CLM can be drawn.

Although excellent survival outcomes were observed in the 43 patients undergoing a repeat hepatectomy, further recurrence remains a major oncological challenge; in the present study, 30 of the patients developed further recurrence. Candidates for iterative resection of recurrent CLM have been selected by the sequence of treatments as patients with slowly progressing disease and favourable tumour biology, as those with extensive recurrence are not candidates for iterative intervention. The present study found the initial tumour size larger or equal to 5 cm and positive surgical margins at first resection of CLM to be predictive factors for shorter survival after a repeat hepatectomy. A large tumour size has been associated with shorter survival in patients undergoing a primary resection of CLM,20,30 and the finding that tumour size also affects outcome after a repeat hepatectomy suggests that it may be a surrogate factor for tumour dissemination in the liver that may remain undetected with current pre-operative and intra-operative imaging methods. Such residual, undetected disease may explain the high risk of developing new liver lesions, leading to a low rate of overall survival. However, patients were selected not on the basis of tumour-related factors such as size (or number) but rather on the potential for safe resection of all tumour deposits while leaving an adequate liver remnant. Indeed, tumour size, although it may be a prognostic factor, is not used to select patients for initial liver resection.31 In patients with recurrent CLM, the authors would not propose that initial or recurrent tumour size should be used to select patients for surgery for otherwise resectable tumours, as prolonged survival can be achieved.

The present study demonstrates that positive surgical margins at an initial hepatectomy, a known risk factor for recurrence after the index liver resection,30 is associated with poorer overall survival after a subsequent hepatectomy. Although prolonged survival has been reported in patients with positive surgical margins who received pre-operative chemotherapy,5,6 margins of resection, which are under the surgeon's control, have a strong impact on the ultimate post-surgical patient outcome. That being said, close or positive margins may occur as a result of extensive or infiltrative disease representing a surrogate factor of unfavourable tumour biology, yet this finding reiterates that, even in the era of modern and effective chemotherapy, the achievement of negative surgical margins remains a primary objective of the surgical therapy of CLM.

In spite of the good survival outcome, a high recurrence rate after a repeat hepatectomy was observed. The relative discrepancy between the high overall survival rate and significant risk for further recurrence may be explained by the fact that a third of the patients who developed further recurrence after a repeat hepatectomy were treated with surgery or local therapy including RFA. Again, as these patients are likely to recur, the use of an aggressive oncosurgical approach probably contributes to prolonged survival. Among prognostic factors related to the second hepatectomy, only negative surgical margins were associated with a decreased risk of further recurrence. To date and in the absence of other significant variables, the ability to achieve negative margins is probably the main factor that should be taken into account when selecting patients for re-resection; oncological outcomes for patients with positive surgical margins at re-resection are dismal (0% 5-year progression-free survival). Moreover, just as the liver is the most common site of recurrence after primary resection of CLM,3 the liver is a very common site of relapse after a repeat hepatectomy for recurrent CLM as well (15/30). The present finding reinforces the difficulty of completely eradicating the disease using a combination of surgery and systemic treatment. Thirty out of 43 patients re-recurred after a repeat hepatectomy in spite of the fact that 20 out of these 30 patients received post-operative chemotherapy. Adjuvant, liver-directed therapy, including hepatic artery infusion and radioembolization, have not been evaluated and may be tested to better control occult disease progression in the liver in this cohort. An unstudied alternative could be more intensive systemic chemotherapy, including monoclonal antibodies targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor (bevacizumab) or the epidermal growth factor receptor (cetuximab, panitumumab), in spite of the paucity of evidence that these agents reduce recurrence rates compared with chemotherapy without targeted agents in stage III colorectal cancer.32

This retrospective analysis of a prospective database has limitations, as the treated cohort may represent a selection of patients with favourable tumour biology; patients who developed unresectable recurrence after an initial resection were not included. However, the comparison with non-operated patients may not be appropriate, as the study aim was not to propose this approach in all patients with recurrent CLM but to provide tools to help in the selection of candidates for a repeat hepatectomy.

In conclusion, these data reinforce the utility of a repeat hepatectomy for recurrent CLM, as a safe treatment associated with excellent long-term survival. The additional finding that negative surgical margins at both the initial and repeat hepatectomy are the predominant prognostic factors reinforces the critical contribution of careful surgical planning and precise tumour localization during resection to optimize oncological outcomes and reduce recurrence risk.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kathryn Hale and Ruth J. Haynes for their assistance with the manuscript preparation. This research is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson's Cancer Center Support Grant CA016672.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Abdalla EK, Vauthey JN, Ellis LM, Ellis V, Pollock R, Broglio KR, et al. Recurrence and outcomes following hepatic resection, radiofrequency ablation, and combined resection/ablation for colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg. 2004;239:818–825. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000128305.90650.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernandez FG, Drebin JA, Linehan DC, Dehdashti F, Siegel BA, Strasberg SM. Five-year survival after resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer in patients screened by positron emission tomography with F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG-PET) Ann Surg. 2004;240:438–447. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000138076.72547.b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Jong MC, Pulitano C, Ribero D, Strub J, Mentha G, Schulick RD, et al. Rates and patterns of recurrence following curative intent surgery for colorectal liver metastasis: an international multi-institutional analysis of 1669 patients. Ann Surg. 2009;250:440–448. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b4539b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pawlik TM, Scoggins CR, Zorzi D, Abdalla EK, Andres A, Eng C, et al. Effect of surgical margin status on survival and site of recurrence after hepatic resection for colorectal metastases. Ann Surg. 2005;241:715–724. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000160703.75808.7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodingbauer M, Tamandl D, Schmid K, Plank C, Schima W, Gruenberger T. Size of surgical margin does not influence recurrence rates after curative liver resection for colorectal cancer liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1133–1138. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Haas RJ, Wicherts DA, Flores E, Azoulay D, Castaing D, Adam R. R1 resection by necessity for colorectal liver metastases: is it still a contraindication to surgery? Ann Surg. 2008;248:626–637. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818a07f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nordlinger B, Vaillant JC, Guiguet M, Balladur P, Paris F, Bachellier P, et al. Survival benefit of repeat liver resections for recurrent colorectal metastases: 143 cases. Association Francaise de Chirurgie. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:1491–1496. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.7.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sa Cunha A, Laurent C, Rault A, Couderc P, Rullier E, Saric J. A second liver resection due to recurrent colorectal liver metastases. Arch Surg. 2007;142:1144–1149. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.12.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinson CW, Wright JK, Chapman WC, Garrard CL, Blair TK, Sawyers JL. Repeat hepatic surgery for colorectal cancer metastasis to the liver. Ann Surg. 1996;223:765–773. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199606000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adam R, Bismuth H, Castaing D, Waechter F, Navarro F, Abascal A, et al. Repeat hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg. 1997;225:51–60. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199701000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaw IM, Rees M, Welsh FK, Bygrave S, John TG. Repeat hepatic resection for recurrent colorectal liver metastases is associated with favourable long-term survival. Br J Surg. 2006;93:457–464. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petrowsky H, Gonen M, Jarnagin W, Lorenz M, DeMatteo R, Heinrich S, et al. Second liver resections are safe and effective treatment for recurrent hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: a bi-institutional analysis. Ann Surg. 2002;235:863–871. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200206000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pessaux P, Lermite E, Brehant O, Tuech JJ, Lorimier G, Arnaud JP. Repeat hepatectomy for recurrent colorectal liver metastases. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93:1–7. doi: 10.1002/jso.20384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farges O, Belghiti J. Repeat resection of liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2006;93:387–388. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Truant S, Huglo D, Hebbar M, Ernst O, Steinling M, Pruvot FR. Prospective evaluation of the impact of [18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography of resectable colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2005;92:362–369. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aloia TA, Zorzi D, Abdalla EK, Vauthey JN. Two-surgeon technique for hepatic parenchymal transection of the noncirrhotic liver using saline-linked cautery and ultrasonic dissection. Ann Surg. 2005;242:172–177. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000171300.62318.f4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palavecino M, Chun YS, Madoff DC, Zorzi D, Kishi Y, Kaseb AO, et al. Major hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma with or without portal vein embolization: perioperative outcome and survival. Surgery. 2009;145:399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mullen JT, Ribero D, Reddy SK, Donadon M, Zorzi D, Gautam S, et al. Hepatic insufficiency and mortality in 1,059 noncirrhotic patients undergoing major hepatectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:854–862. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nordlinger B, Guiguet M, Vaillant JC, Balladur P, Boudjema K, Bachellier P, et al. Surgical resection of colorectal carcinoma metastases to the liver. A prognostic scoring system to improve case selection, based on 1568 patients. Association Francaise de Chirurgie. Cancer. 1996;77:1254–1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanazawa A, Shiozawa M, Inagaki D, Morinaga S, Sugimasa Y, Oshima T, et al. Risk factors for intrahepatic recurrence after curative surgical treatment of colorectal liver metastases. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57:1183–1186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adam R, Pascal G, Azoulay D, Tanaka K, Castaing D, Bismuth H. Liver resection for colorectal metastases: the third hepatectomy. Ann Surg. 2003;238:871–883. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000098112.04758.4e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belghiti J, Guevara OA, Noun R, Saldinger PF, Kianmanesh R. Liver hanging maneuver: a safe approach to right hepatectomy without liver mobilization. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:109–111. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)00909-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zorzi D, Laurent A, Pawlik TM, Lauwers GY, Vauthey JN, Abdalla EK. Chemotherapy-associated hepatotoxicity and surgery for colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2007;94:274–286. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakano H, Oussoultzoglou E, Rosso E, Casnedi S, Chenard-Neu MP, Dufour P, et al. Sinusoidal injury increases morbidity after major hepatectomy in patients with colorectal liver metastases receiving preoperative chemotherapy. Ann Surg. 2008;247:118–124. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815774de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vauthey JN, Pawlik TM, Ribero D, Wu TT, Zorzi D, Hoff PM, et al. Chemotherapy regimen predicts steatohepatitis and an increase in 90-day mortality after surgery for hepatic colorectal metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2065–2072. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elias D, De Baere T, Smayra T, Ouellet JF, Roche A, Lasser P. Percutaneous radiofrequency thermoablation as an alternative to surgery for treatment of liver tumour recurrence after hepatectomy. Br J Surg. 2002;89:752–756. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schindera ST, Nelson RC, DeLong DM, Clary B. Intrahepatic tumor recurrence after partial hepatectomy: value of percutaneous radiofrequency ablation. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:1631–1637. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000239106.98853.B8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aloia TA, Vauthey JN, Loyer EM, Ribero D, Pawlik TM, Wei SH, et al. Solitary colorectal liver metastasis: resection determines outcome. Arch Surg. 2006;141:460–466. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.5.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fong Y, Fortner J, Sun RL, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 1999;230:309–318. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charnsangavej C, Clary B, Fong Y, Grothey A, Pawlik TM, Choti MA. Selection of patients for resection of hepatic colorectal metastases: expert consensus statement. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:1261–1268. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9023-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allegra CJ, Yothers G, O'Connell MJ, Sharif S, Colangelo LH, Lopa SH, et al. Initial safety report of NSABP C-08: a randomized phase III study of modified FOLFOX6 with or without bevacizumab for the adjuvant treatment of patients with stage II or III colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3385–3390. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.9220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]