Abstract

Using data from a national family survey, the authors describe the adult lives (i.e., residence, employment, level of assistance needed with everyday life, friendships, and leisure activities) of 328 adults with the full mutation of the FMR1 gene and identify characteristics related to independence in these domains. Level of functional skills was the strongest predictor of independence in adult life for men, whereas ability to interact appropriately was the strongest predictor for women. Co-occurring mental health conditions influenced independence in adult life for men and women, in particular, autism spectrum disorders for men and affect problems for women. Services for adults with fragile X syndrome should not only target functional skills but interpersonal skills and co-occurring mental health conditions.

Fragile X syndrome is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by an expansion to 200 or more repetitions of the CGG sequence of nucleotides composing the 5′ untranslated region of the FMR1 gene located on the X chromosome (Brown, 2002). Individuals who have 55 to 200 CGG repeats in the FMR1 gene are said to carry the premutation. The full mutation of the FMR1 gene is the leading inherited cause of intellectual disability, and researchers estimate that fragile X syndrome associated with intellectual disability occurs in 1 in 3,600 individuals in the general population (Crawford, Acuna, & Sherman, 2001; Hagerman et al., 2009). Researchers have described the fragile X syndrome profile of cognitive and communication impairments and co-occurring conditions, including attention problems, hyperactivity, anxiety, and autistic symptoms (e.g., Abbeduto, Brady, & Kover, 2007; Bailey, Raspa, Olmsted, & Holiday, 2008; Cornish, Turk, & Hagerman, 2008; Hagerman & Hagerman, 2002). Most of these studies focused on children or adolescents. Very little research has examined what this profile means for the everyday lives of adults with fragile X syndrome.

There is no single definition of what constitutes success in adult life for individuals with intellectual disability. However, several common goals for adult life have been articulated by organizations, government agencies, and in legislation (Luckasson et al., 2002; Rehabilitation Act Amendment of 1998 [P.L. 105–200]; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000; World Health Organization [WHO], 2001). These goals include living independently, gaining employment, developing proficiency in activities of everyday life, developing friendships, and participating in a variety of leisure activities. Virtually nothing is known about the extent to which men and women with the full mutation of the FMR1 gene are able to reach these levels of independence in adult life. In this study, we explored the adult life of men and women with the full mutation of the FMR1 gene, as reported by parents in a large national survey. In an additional goal, we focused on identifying factors related to achieving independence in the adult life of men and women with fragile X syndrome. This information is critical for understanding the needs of adults with fragile X syndrome and tailoring services and public policy to enhance their quality of life.

Although the full mutation of the FMR1 gene is associated with a general pattern of impairment, considerable variability exists across individuals. Whereas males with fragile X syndrome generally have moderate to severe intellectual disability (Hall, Burns, Lightbody, & Reiss, 2008), one third to one half of females with fragile X syndrome have average intellectual functioning (Loesch et al., 2002). This sex-related disparity in intellectual functioning is due to the fact that females have two X chromosomes (only one of which is affected), whereas males only have one. In addition, X inactivation in females results in a mosaic pattern of affectedness (Tassone, Hagerman, Chamberlain, & Hagerman, 2000). Given this more mild presentation, some adult women with the full mutation of the FMR1 gene may have very normative adult lives, including living independently, and often with a spouse or romantic partner; pursuing higher education; holding full-time jobs; having friends; and participating in a range of leisure activities. Adult men with fragile X syndrome are more likely to have much more limited independence in terms of their residence, employment, ability to perform tasks of everyday life, friendships, and leisure activities. However, there is also likely to be considerable within-sex heterogeneity in the adult lives of men and women with fragile X syndrome.

Children and adults with fragile X syndrome often have impairments in functional skills (e.g., a lack of or limited skills for dressing, eating, communication; Bailey et al., 2009). Functional level has repeatedly been shown to be a strong correlate of a range of outcomes for adults with intellectual disability, including employment success (e.g., Braddock, Rizzolo, & Hemp, 2004) and friendships (e.g., Emerson & McVilly, 2004; Robertson et al., 2001). Well-developed interpersonal skills are also required in adult life. Fragile X syndrome is associated with deficits in social perception (Aziz et al., 2003; Cornish et al., 2008), elevations in social anxiety (Bregman, Lackman, & Ort, 1988; Mazzocco, Baumgardner, Freund, & Reiss, 1998), and autism symptoms, including poor social relatedness (Bailey, Hatton, Tessone, Skinner, & Taylor, 2001; Bailey et al., 1998). Therefore, the degree to which adults with fragile X syndrome are able to interact with others may be critical to their independence in the roles that define adult life (e.g., employment, friendships).

Children and adults with fragile X syndrome have a heightened rate of co-occurring mental health problems. Affect problems, including anxiety and depression, have been found to occur in one half to more than two thirds of males and females (ages 4–59 years) with the full mutation of the FMR1 gene (Bailey et al., 2008). Attention problems and/or hyperactivity have also been found to be significant problems for approximately 80% of children and adults with fragile X syndrome (Bailey et al., 2008; Sullivan et al., 2006). Moreover, self-injurious behavior and aggression are common and significant problems for more than 50% of children and adolescents with fragile X syndrome (Hagerman & Hagerman, 2002; Symons, Clark, Hatton, Skinner, & Bailey, 2003). The extent to which these co-occurring mental health conditions impact independence in adult life specifically for men and women with fragile X syndrome has not been investigated. However, studies using heterogeneous samples of adults with intellectual disability or other genetic disorders associated with intellectual disability have shown that such co-occurring mental health conditions are often important predictors of outcomes, such as unemployment (e.g., Martorell, Gutierrez-Recacha, Pereda, & Ayuso-Mateos, 2008) and less independent residential placement (e.g., Black, Molaison, & Smull, 1990; Heller & Factor, 1991).

Perhaps the strongest predictor of outcomes in adult life for individuals with fragile X syndrome may be the presence of an autism spectrum disorder. Researchers have estimated that 25% to 44% of children and adolescents with fragile X syndrome also meet criteria for an autism spectrum disorder diagnosis (Bailey et al., 1998; Philofsky, Hepburn, Hayes, Hagerman, & Rogers, 2004; Reiss & Freund, 1990; Rogers, Wehner, & Hagerman, 2001). These individuals tend to have lower IQ scores, poorer adaptive skills, and less advanced language skills than individuals with fragile X syndrome only (Bailey et al., 1998; Philofsky et al., 2004). Autism symptoms, themselves, can be stressful and challenging for families, and, thus, adults with autism spectrum disorder are less likely to co-reside with family and more likely to be living in group home or other community placements than are adults with intellectual disability, due to other etiologies (Krauss, Seltzer, & Jacobson, 2005). Adults with autism spectrum disorder also have been shown to have marked difficulties in adult life, including employment, social relationships, and residential independence (Howlin, Goode, Hutton, & Rutter, 2004). Adults with fragile X syndrome who also have an autism spectrum disorder diagnosis may, thus, have more limited independence in adult life than those with fragile X syndrome only.

The primary purpose of this study was to describe five dimensions of adult life (residence, employment, assistance needed in activities of daily living, friendship, and leisure activities) for men and women with the full mutation of the FMR1 gene, drawing on data from a national survey. Given the descriptive nature of this goal, hypotheses regarding outcomes in adult life were not made. The second purpose of this study was to investigate the extent to which four individual characteristics were associated with independence in adult life: sex, functional skills, ability to interact appropriately, and co-occurring mental health conditions. We examined three hypotheses based on past research: (a) Consistent with sex-related profiles in childhood, we expected that men with fragile X syndrome would have more limited independence in adult life than women. (b) We expected functional skills and ability to interact appropriately to be strong predictors of independence in adult life. (c) We expected the presence of co-occurring mental health conditions, particularly autism spectrum disorder, to be related to more limited independence in adult life.

Method

Participants

The present analyses were based on data from a larger survey assessing the characteristics and needs of families who had at least one child who had the premutation or full mutation of the FMR1 gene (Bailey et al., 2008, 2009). Families were recruited through foundations (National Fragile X Foundation, FRAXA Research Foundation, and Conquer Fragile X Foundation), researchers, and clinicians. A total of 1,250 families enrolled in the study, and 1,075 families completed the survey. The subset of 259 families who had a total of 328 adult children ages 22 years or more with the full mutation of the FMR1 gene constituted the sample for the present analyses.

The majority of respondents in the present analysis were mothers (89.0%), but a small number were fathers (9.1%) or other family members (1.8%). Respondents were predominately Caucasian (95.7%). Families lived in the United States: 37 (14.3%) lived in the northeast, 79 (30.5%) lived in the Midwest, 81 (31.3%) lived in the south, and 63 (24.3%) lived in the west. The majority of families (54.1%) had an annual income of at least $75,000. The majority of mothers were well educated: 113 (43.6%) had at least a 4-year college degree, whereas 80 (30.9%) had some college or technical school, 32 (12.4%) had a high school degree or general education diploma (GED; tests taken to indicate that person has high school–level skills), and 5 (1.9%) had less than a high school education. Maternal education was not reported for 29 (11.2%) members of the sample. Of the adults with fragile X syndrome, 89 (27.1%) were female and 239 (72.9%) were male. They ranged in age from 22.1 to 63.5 years, with the following breakdown of ages for males and females respectively: 22–30 years, 59.8% and 64.0%; 31–40 years, 25.2% and 28.1%; 41–50 years, 12.1% and 6.7%; 51–60 years, 2.5% and 0%; and ≥61 years, 0.4% and 1.1%.

Procedures

Families were sent a letter and brochure inviting them to enroll in the study during the summer and fall of 2007. Families who enrolled in the study were then asked to participate in a comprehensive survey regarding their family characteristics and needs. The majority of families chose to enroll and completed the survey online (73.8%), whereas the remainder completed enrollment and the survey over the phone with a trained interviewer. The survey, online or via the phone, took approximately 1.0 to 1.5 hr to complete.

Measures

Independence in adult life

Families indicated the residential setting of their child with fragile X syndrome as living in a hospital, residential treatment center, or mental health facility; living in a community group home; co-residing with parents; or living independently (i.e., alone or with a roommate or partner). In 57 (17.38%) families, the adult with fragile X syndrome either lived in an unspecified alternative location or parents did not report residential setting of their adult son or daughter. Therefore, these families were not included in analyses regarding residential setting. Only 3 (1.51%) of adults with fragile X syndrome, all men, lived in a hospital, residential treatment center, or mental health facility. Given this small number, this category was also excluded from further analyses. The remaining categories were recoded as follows: 0 = living in a group home, 1 = co-residing with parents, and 2 = living independently.

Families were also asked about their adult son or daughter’s employment. The following ratings were assigned: 0 = unemployed, 1 = employed part time, and 2 = employed full time. Families were also asked whether their adult son or daughter’s with fragile X syndrome had a job coach, the type of job their son or daughter had, and if their son or daughter received any benefits such as insurance–vacation–retirement from their employer.

Families rated the level of assistance their adult son or daughter needed with everyday life using a 4-point scale (0–3), corresponding to the labels of no assistance, minimal amount of assistance, moderate amount of assistance, and considerable amount of assistance needed. To be consistent with the other dimensions of adult life, which were rated on a 3-point scale and for which higher scores denoted a higher level of independence, this item was reverse scored and the response options moderate amount of assistance and considerable amount of assistance were combined. The resulting codes for assistance needed with everyday life were as follows: 0 = moderate or considerable amount of assistance, 1 = minimal assistance, and 2 = no assistance.

Families were asked to indicate the number of friends their adult son or daughter with fragile X syndrome had and whether their son or daughter regularly visited or talked to friends on the phone. A total friendship score was created by combining responses on these items: 0 = no (no friends), 1 = some (1 or 2 friends, or 3 or more friends but do not visit or talk to friends on the phone), and 2 = considerable (≥3 friends and visit and/or talk to these friends on phone).

Leisure activity was assessed by asking families to indicate whether their adult son or daughter with fragile X syndrome engaged in the following leisure activities: visiting family; reading, writing, or going to the library; working around the house; painting, drawing, or other art activities; playing on the computer, surfing the Internet, or e-mailing; watching television or playing video games; listening to music; exercising or spending time outdoors; shopping; going to the movies, concerts, or sporting events; going to church or other religious activities; or other leisure activities. These items were based on activities commonly included in measures of leisure activity (e.g., Passmore & French, 2001). The total number of leisure activities participated in was then coded as 0 = 0–2 activities, 1 = 3–5 activities, and 2 = ≥6 activities.

A composite measure of independence in adult life was created by summing the scores for residence, employment, assistance with everyday life, friendship, and leisure. Five categories of overall independence were created: 0–2 = very low independence, 3–4 = low independence, 5–6 = moderate independence, 7–8 = high independence, and 9–10 = very high independence.

Predictors of independence

Demographic information about the family (e.g., maternal education) and each child in the family (e.g., date of birth, sex, and genetic status) was obtained. Overall health of the adult son or daughter with fragile X syndrome was assessed using five response options: 1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, and 5 = excellent. Number of co-occurring mental health conditions was assessed by asking families to indicate whether their son or daughter with fragile X syndrome had been diagnosed or treated for the following six conditions: attention problems, hyperactivity, aggressiveness, self-injury, anxiety, depression, and/or an autism spectrum disorder. For the present analyses, depression and anxiety problems were combined into one item and are referred to as affect problems. The total number of co-occurring mental health conditions endorsed was used in some analyses.

Families rated their adult son or daughter’s functional skills with respect to 37 items assessing eating, dressing, toileting, bathing and hygiene, communication, articulation, and reading skills (Bailey et al., 2009). These items were based on items included in standardized assessments of adaptive living skills (e.g., Harrison & Oakland, 2006; Simeonsson & Bailey, 1991; Sparrow, Cicchetti, & Balla, 2005). The following four response options were used to rate items: 0 = does not perform this task, 1 = does this task but not well, 2 = does this task fairly well, or 3 = does this task very well. A total functional skill score was created by summing scores on all items. Mean score imputation was used to calculate the functional skills score if 25% or fewer of the items were missing. Although functional skills may seem to overlap with one of the other analytic variables in this study, namely, assistance needed in everyday life, the correlation among these variables (r = .54, p < .001) was moderate, indicating that individuals required assistance in everyday life for reasons such as co-occurring mental health problems or poor interpersonal skills, in addition to low functional skills. Parents were also asked to rate their adult son or daughter’s ability to interact appropriately with others using the following scale: 1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, and 4 = very good.

Education of the adult with fragile X syndrome was rated using a 4 point scale: 0 = high school completion certificate (i.e., finished high school but did not qualify for a high school diploma), 1 = high school diploma or GED, 2 = vocational/trade school certificate or community college degree, and 3 = bachelor’s or graduate degree. Seventy-seven families (23.48%) did not report on their son or daughter’s highest education degree. In many of these cases, the adult son or daughter with fragile X syndrome had fairly low functional skills and the missing data may have stemmed from confusion regarding whether they received a high school completion certificate. This amount of missing data made it impossible to include education in some analyses. There were also missing data (ranging from 1.52% for problems with aggression to 10.98% for maternal education) for the other characteristic variables, although to a much lesser extent.

Plan for Analysis

In the following sections, we provide descriptive data for men and women with fragile X syndrome with respect to demographic characteristics (age, race, and maternal education) as well as their health, education, functional skills, ability to interact, and co-occurring mental health problems. Then, we examine the five domains of adult life (residence, employment, assistance needed with everyday life, friendships, and leisure activity), categorizing the men and women with respect to level of independence in each domain, and we describe the intercorrelations of level of independence across these domains. Next, we examine, again within each domain, how men and women at various levels of independence differed in their characteristics and abilities. Last, we combine all of the preceding analyses in regression models that predict overall independence in adult life, separately for men and women. Our overarching goal is to provide both a rich description of adult life for men and women with fragile X syndrome and to identify factors that can inform interventions for increasing independence. Although these successive analyses are overlapping, they each provide a distinct perspective on adult life for men and women with fragile X syndrome.

Results

Characteristics of Adults With Fragile X Syndrome

Prior to describing results for each dimension of adult life, we report on the characteristics of the men and women with fragile X syndrome, as presented in Table 1. As expected, women with fragile X syndrome had significantly more education than the men in this category. Women also had significantly higher functional skills and a greater ability to interact appropriately than men. Co-occurring mental health conditions were common, particularly for men, who had a significantly higher number of co-occurring mental health conditions than women. Problems with inattention–hyperactivity and affect were reported for the large majority of men (84.68% and 71.74%, respectively) and more than half of women (65.48% and 58.82%, respectively). More than one third of men also had been diagnosed with or treated for problems with aggression (43.04%), self-injury (47.26%), and autism spectrum disorder (37.28%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants

| Characteristic | Women (n = 89) | Men (n = 239) | χ2/t value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years; M [SD]) | 30.27 (7.76) | 31.46 (8.20) | t(326) = 1.18 |

| Caucasian (n [%]) | 87 (97.75) | 226 (94.56) | χ2(1, N = 327) = 1.51 |

| Maternal education (n [%]) | |||

| College degree or higher | 40 (54.05) | 113 (52.07) | χ2(1, N = 290) = 0.87 |

| Health (M [SD]) | 3.80 (1.11) | 3.88 (0.98) | t(323) = 0.63 |

| Education (M [SD]) | 1.36 (0.91) | 0.47 (0.57) | t(249) = 9.18*** |

| Functional skills (M [SD]) | 137.00 (12.78) | 117.84 (18.85) | t(301) = 8.29*** |

| Ability to interact (M [SD]) | 2.30 (0.91) | 1.92 (0.88) | t(323) = 3.46*** |

| Number of co-occurring | |||

| mental health problems (M [SD]) | 1.61 (1.21) | 2.80 (1.49) | t(307) = 6.50*** |

| Inattention (n [%]) | 57 (66.28) | 197 (82.77) | χ2(1, N = 318) = 14.07*** |

| Hyperactivity (n [%]) | 21 (27.71) | 151 (64.26) | χ2(1, N = 318) = 13.67*** |

| Affect problems (n [%]) | 50 (58.82) | 167 (71.74) | χ2(1, N = 317) = 4.75* |

| Aggression (n [%]) | 11 (12.79) | 102 (43.04) | χ2(1, N = 322) = 25.38*** |

| Self-injury (n [%]) | 14 (16.67) | 112 (47.26) | χ2(1, N = 320) = 24.34*** |

| ASD (n [%]) | 8 (9.64) | 88 (37.28) | χ2(1, N = 319) = 20.71*** |

Note. ASD = autism spectrum disorder. χ2/t value = results of independent samples t test or chi-square test. % = column percentages.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001. Boldfaced numbers also denote statistical significance.

Independence in Adult Life

Table 2 presents the number and percentage of men and women at various levels of independence in each dimension of adult life as well as for the overall composite measure of independence. As expected, there was a significant difference by sex in all dimensions of adult life and in the overall composite measure of independence. Most men had moderate to low levels of independence in adult life on the measure of overall independence, and only 1 man had the highest level of independence. In contrast, women were more evenly distributed among the level of independent categories with about one third having a moderate level of independence in adult life, almost one quarter having a high level of independence, and almost one fifth achieving the highest level of independence.

Table 2.

Number and Percentage of Men and Women With Fragile X Syndrome in Various Outcomes

| Outcome | Women (n = 89): n (%) | Men (n = 239): n (%) | χ2/t value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residence | |||

| 2 = Independenta | 32 (43.84) | 20 (10.26) | |

| 1 = Co-reside with parents | 37 (50.68) | 137 (70.26) | |

| 0 = Group home | 4 (5.48) | 38 (19.49) | χ2(2, N = 266) = 40.65*** |

| Employment | |||

| 2 = Full time | 38 (47.50) | 46 (20.44) | |

| 1 = Part time | 20 (25.00) | 90 (40.00) | |

| 0 = Not working | 22 (27.50) | 89 (39.56) | χ2(2, N = 303) = 33.07*** |

| Assistance needed in everyday life | |||

| 2 = No assistance | 30 (37.50) | 11 (4.87) | |

| 1 = Minimal assistance | 35 (43.75) | 86 (38.05) | |

| 0 = Moderate/considerable | 15 (18.75) | 129 (57.08) | χ2(2, N = 305) = 54.23*** |

| Friendships | |||

| 2 = Considerable | 48 (60.00) | 65 (29.41) | |

| 1 = Some | 25 (31.25) | 114 (51.58) | |

| 0 = None | 7 (8.75) | 42 (19.00) | χ2(2, N = 300) = 23.69*** |

| Leisure | |||

| 2 = ≥6 activities | 58 (72.50) | 113 (50.00) | |

| 1 = 3–5 activities | 19 (23.75) | 83 (36.73) | |

| 0 = 0–2 activities | 3 (3.75) | 30 (13.27) | χ2(2, N = 304) = 7.42** |

| Overall independence | |||

| Very high level of independence (9–10) | 15 (20.55) | 1 (0.53) | |

| High level of independence (7–8) | 17 (23.29) | 16 (8.56) | |

| Moderate level of independence (5–6) | 24 (32.88) | 64 (34.22) | |

| Low level of independence (3–4) | 15 (20.55) | 70 (37.43) | |

| Very low level of independence (0–2) | 2 (2.74) | 36 (19.25) | t(322) = 8.78*** |

Note. χ2/t value = results of independent samples t-test or chi-square test.

p <.05.

p <.01.

p <.001. Boldfaced numbers also denote statistical significance.

Of these adults, 15 women and 1 man lived with a spouse/partner and the rest lived alone or with a roommate/partner.

Examination of each dimension that composed the composite measure of independence in adult life revealed that women were significantly more likely to live independently and less likely to live with family or in a group home than men. They were significantly more likely to be employed full time and less likely to be employed part time or unemployed than men. They were significantly more likely to need no assistance and less likely to need moderate–considerable assistance with everyday life than men. They had significantly more friendships than men. Women were also significantly more likely to participate in six or more leisure activities and less likely to participate in two or fewer leisure activities than men.

There were several significant associations among the dimensions of adult life for men. Employment was significantly correlated with assistance needed with everyday life (r = .13, p = .03), friendships (r = .15, p = .02), and leisure activities (r = .13, p = .03). The strongest association, however, was the significant association between leisure activities and friendships (r = .37, p < .001). A somewhat different pattern of associations among the dimensions of adult life emerged for women. Notably, friendship and leisure were not associated significantly for women, whereas this was the strongest association among the dimensions of adult life for men. In addition, residence was significantly correlated with assistance needed with everyday life (r = .40, p = .01) and friendship (r = .30, p < .01) for women but not men. Friendship was also significantly correlated with employment (r = .36, p < .001) for women but not men.

Adult Characteristics by Dimension of Adult Life: Residential Setting

We examined differences among men and women with fragile X syndrome who lived independently, who co-resided with parents, and who lived in a group home with respect to their functional skills, ability to interact appropriately, and number of co-occurring mental health conditions. We also examined how adults in these three residential categories differed with respect to maternal education, age, race, health, and education. Table 3 presents the results of the one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and chi-square tests examining differences in characteristics of men and women with fragile X syndrome by residential setting.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Adults by Dimension of Adult Life: Residence

| Variable | Men

|

Women

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent (n = 20) | Co-reside w/parents (n = 137) | Group home (n = 38) | F/χ2 value | Independent (n = 32) | Co-reside w/parents (n = 37) | Group home (n = 4) | F/χ2 value | |

| Age in years (M [SD]) | 33.22 (6.80)b | 28.75 (6.57) | 36.85 (8.64)a,b | F(2, 304) = 21.06** | 31.71 (6.93)b | 26.74 (5.48) | 29.60 (6.76) | χ2(2, N = 71) = 5.49** |

| Caucasian (n [%]) | 19 (95.0) | 126 (92.0) | 38 (100.0) | χ2(2, N =303) = 3.37 | 31 (96.9%) | 36 (97.3) | 4 (100.0) | χ2(2, N = 71) = 0.13 |

| Maternal college+ (n [%]) | 11 (55.0) | 62 (50.0) | 22 (66.7) | χ2(2, N =175) = 2.93 | 12 (42.9%) | 21 (67.7) | 1 (25.0) | χ2(2, N = 61) = 5.11 |

| Health (M [SD]) | 4.00 (1.08) | 3.99 (0.85) | 3.73 (1.07) | F(2, 192) = 1.18 | 3.56 (0.95) | 4.14 (1.18) | 4.25 (0.96) | F(2, 71) = 2.67 |

| Education (M [SD]) | 0.39 (0.61) | 0.55 (0.59) | 0.33 (0.48) | F(2, 162) = 1.83 | 1.64 (0.95)c | 1.13 (0.73) | 0.33 (0.58) | F(2, 59) =4.92** |

| Functional skills (M [SD]) | 126.20 (14.81)c | 118.50 (18.70)c | 112.01 (17.90) | F(2, 191) = 4.08* | 141.13 (8.40)c | 134.11 (3.69)c | 118.75 (7.91) | F(2, 68) =27.37** |

| Ability to interact (M [SD]) | 2.17 (0.92) | 1.89 (0.86) | 1.68 (0.78) | F(2, 191) = 2.06 | 2.63 (1.01)c | 2.05 (0.82) | 1.25 (0.50) | F(2, 71) = 6.18** |

| Mental health problems (M [SD]) | 2.35 (1.66) | 2.64 (1.42) | 3.24 (1.42)a | F(2, 191) = 3.03* | 1.53 (1.20) | 1.54 (1.09) | 3.75 (0.96)a | F(2, 71) = 7.18** |

Note. F/χ2 values = results of one-way analysis of variance or chi-square test. % = column percentages; w/= with.

p <.05.

p <.01. Boldfaced numbers also denote statistical significance.

Higher than “Independent” at p <.05.

Higher than “Co-reside with parents” at p <.05.

Higher than “Group home” at p <.05.

There was a significant difference across residential setting categories in age, functional skills, and number of co-occurring mental health conditions for men and women. Men living in group homes were oldest, followed by those living independently, whereas men co-residing with parents were the youngest. Similarly, women co-residing with parents were younger than women living independently. Men and women living independently had higher functional skills and a smaller number of co-occurring mental health conditions than those living in group homes, with men and women co-residing with parents generally in the middle on these characteristics. There was also a significant difference by residential setting in education and ability to interact appropriately for women. Women living independently had more education and a greater ability to interact appropriately than women living in group homes. The absence of race and maternal education effects suggest that socioeconomic status is not a critical factor in living arrangements of adults with fragile X syndrome, at least within this sample.

Adult Characteristics by Dimension of Adult Life: Employment

Figure 1 presents the percentage of men and women with fragile X syndrome in various types of jobs. The most common jobs for men were production or assembly jobs (34.5%), food preparation or service jobs (21.8%), and cleaning or maintenance jobs (11.3%). The most common jobs for women were education, training, or library work (12.3%); clerical or office work (7.8%); and cashier, clerk, or retail work (5.5%). Of those who were employed, 83 (61.3%) men and 14 (24.6%) women had a job coach. Only 32.9% of the men (n = 92) received benefits from their job such as vacation, insurance, or retirement compared with 56.1% of the women (n = 32).

Figure 1.

Percentage of men and women with fragile X syndrome employed in various types of jobs.

Table 4 displays the results of the one-way ANOVAs and chi-square tests examining differences in characteristics of men and women with fragile X syndrome by employment status (employed full time, employed part time, and unemployed). There was a significant difference by employment status in health and ability to interact appropriately for both men and women. Men and women who were employed full time had a greater ability to interact appropriately and had better health than those who were unemployed or employed only part time. In addition, there was a significant difference by employment status in functional skills and number of co-occurring mental health problems for men. Men who were employed full time had higher functional skills and a smaller number of co-occurring mental health conditions than men who were unemployed, with men who were employed part time falling in the middle.

Table 4.

Characteristics of Adults by Dimension of Adult Life: Employment Status

| Variable | Men

|

Women

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full time (n = 46) | Part time (n = 90) | Unemployed (n = 89) | F/χ2 value | Full time (n = 38) | Part time (n = 20) | Unemployed (n = 22) | F/χ2 value | |

| Age in years (M [SD]) | 32.57 (8.86) | 29.87 (6.40) | 32.11 (9.10) | F(2, 223) = 2.52 | 29.55 (6.16) | 30.27 (7.46) | 28.30 (7.32) | F(2, 78) = 0.46 |

| Caucasian (n [%]) | 45 (97.8%)c | 88 (97.8)c | 79 (88.8) | χ2(2, N = 223) = 8.06* | 37 (97.4) | 19 (95.0) | 22 (100.0) | χ2(2, N = 75) = 1.08 |

| Maternal college+ (n [%]) | 20 (47.9%) | 50 (64.1) | 36 (44.8) | χ2(2, N = 203) = 3.48 | 15 (48.4) | 16 (84.2)a,c | 7 (38.0) | χ2(2, N = 66) = 9.00** |

| Health (M [SD]) | 3.93 (0.90) | 4.09 (0.93)c | 3.70 (0.97) | F(2, 222) = 3.94* | 4.13 (0.94)c | 4.00 (0.97)c | 3.18 (1.18) | F(2, 78) = 5.83* |

| Education (M [SD]) | 0.43 (0.59) | 0.48 (0.61) | 0.49 (0.50) | F(2, 181) = 2.52 | 1.53 (1.03) | 1.23 (0.82) | 1.08 (0.49) | F(2, 64) = 1.43 |

| Functional skills (M [SD]) | 125.06 (15.51)c | 122.74 (13.68)c | 109.42 (21.69) | F(2, 222) = 17.42* | 140.48 (9.33) | 135.06 (13.55) | 132.52 (15.69) | F(2, 74) = 2.95 |

| Ability to interact (M [SD]) | 2.07 (0.85)c | 1.98 (0.83) | 1.82 (1.92) | F(2, 221) = 1.43* | 2.61 (0.97)c | 2.25 (1.02) | 1.86 (0.83) | F(2, 78) = 4.31* |

| Mental health problems (M [SD]) | 2.43 (1.48) | 2.64 (1.42) | 3.18 (1.51)a | F(2, 215) = 4.69** | 1.50 (1.08) | 1.60 (1.35) | 1.95 (1.35) | F(2, 74) = 0.84 |

Note. F/χ2 values = results of one-way analysis of variance or chi-square test. % = column percentages.

p <.05.

p <.01. Boldfaced numbers also denote statistical significance.

Higher than “Full time” at p <.05.

Higher than “Part time” at p <.05.

Higher than “Unemployed” at p <.05.

Socioeconomic factors were associated with employment outcomes; a greater percentage of unemployed men were of minority status than was true of men who were employed and a greater percentage of women who were employed part time had mothers with at least a college education compared with women who were employed full time or unemployed.

Adult Characteristics by Dimension of Adult Life: Assistance Needed With Everyday Life

Table 5 presents a parallel set of analyses focusing on level of assistance needed with everyday life. There was a significant difference among the categories of level of assistance needed with everyday life with respect to education, functional skills, ability to interact appropriately, and number of co-occurring mental health conditions for both men and women. Men and women who required no assistance with everyday life had more education, higher functional skills, a greater ability to interact, and a smaller number of co-occurring mental health conditions than those who required a moderate to a considerable amount of assistance, with adults requiring a minimal amount of assistance falling in the middle. In addition, there was a significant difference by level of assistance needed with everyday life with respect to age for women and health for men. Women who required no assistance with everyday life were older than women who required a minimal amount of assistance. Men who required no assistance with everyday life were in better health and had more education and higher functional skills than men who needed a moderate to a considerable amount of assistance, with men requiring a minimal amount of assistance scoring in the middle on these characteristics.

Table 5.

Characteristics of Adults by Dimension of Adult Life: Level of Assistance Needed With Everyday Life

| Variable | Men

|

Women

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 11) | Minimal (n = 86) | Moderate/considerable (n = 129) | F/χ2 value | No (n = 30) | Minimal (n = 35) | Moderate/considerable (n = 15) | F/χ2 value | |

| Age in years (M [SD]) | 31.66 (6.37) | 31.84 (7.89) | 31.12 (8.60) | F(2, 224) = 0.20 | 31.83 (7.41)b | 27.59 (5.79) | 28.69 (6.54) | F(2, 78) = 3.47* |

| Caucasian (n [%]) | 11 (100.0) | 82 (95.3) | 121 (93.8) | χ2(2, N = 224) = 0.89 | 29 (96.7) | 34 (97.1) | 15 (100.0) | χ2(2, N = 78) = 0.49 |

| Maternal college+ (n [%]) | 4 (40.0) | 43 (53.1) | 59 (51.3) | χ2(2, N = 204) = 0.61 | 16 (66.1) | 14 (48.3) | 8 (53.3) | χ2(2, N = 66) = 1.85 |

| Health (M [SD]) | 4.55 (0.69)c | 4.08 (0.88) | 3.73 (0.98) | F(2, 223) = 6.49** | 3.90 (1.13) | 3.77 (1.09) | 3.87 (1.30) | F(2, 78) = 0.11 |

| Education (M [SD]) | 0.91 (0.71)b,c | 0.51 (0.56) | 0.41 (0.55) | F(2, 182) = 3.72* | 1.78 (0.97)b,c | 1.18 (0.72) | 0.82 (0.75) | F(2, 64) = 6.29** |

| Functional skills (M [SD]) | 135.55 (10.31)b,c | 125.92 (14.08)c | 110.90 (19.20) | F(2, 223) = 26.12** | 144.30 (7.91)b,c | 135.71 (11.40)c | 126.03 (14.83) | F(2, 74) = 13.39** |

| Ability to interact (M [SD]) | 2.45 (0.04)c | 2.19 (0.88)c | 1.72 (0.80) | F(2, 222) = 10.27** | 3.07 (0.91)b,c | 2.03 (0.71)c | 1.47 (0.64) | F(2, 78) = 25.31** |

| Mental health problems (M [SD]) | 2.09 (1.30) | 2.41 (1.51) | 3.16 (1.40)a | F(2, 217) = 8.14** | 1.31 (1.07) | 1.84 (1.11)a | 2.31 (1.44)a | F(2, 74) = 5.53** |

Note. F/χ2 values = results of one-way analysis of variance or chi-square test. % = column percentages.

p <.05.

p <.01. Boldfaced numbers also denote statistical significance.

Higher than “No” at p <.05.

Higher than “Minimal” at p <.05.

Higher than “Moderate/considerable” at p < .05.

Adult Characteristics by Dimension of Adult Life: Friendships

Table 6 presents the results of the similar analyses focusing on friendships. There was a significant difference with respect to friendships in ability to interact appropriately and education for men and women. For both men and women, those with a considerable number of friendships had a greater ability to interact appropriately than those with no or only some friendships. However, men and women showed an opposite pattern of results for education. Women with no friendships had less education than women with some or a considerable number of friendships, whereas men with no friendships had more education than men with at least some friendships. In addition, there was a significant difference by friendships in functional skills for men and in age and number of co-occurring mental health conditions for women. Men who had a considerable number of friendships had higher functional skills than men who had no friends, with those who had some friendships in the middle. Women with a considerable number of friendships were older and had a smaller number of co-occurring mental health conditions than women with no or only some friendships.

Table 6.

Characteristics of Adults by Dimension of Adult Life: Friendships

| Variable | Men

|

Women

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Considerable (n = 65) | Some (n = 114) | None (n = 42) | F/χ2 value | Considerable (n = 48) | Some (n = 25) | None (n = 7) | F/χ2 value | |

| Age in years (M [SD]) | 30.63 (7.84) | 31.65 (7.87) | 30.41 (8.56) | F(2, 219) = 0.54 | 30.56 (7.19)c | 28.82 (5.98)c | 23.31 (1.42) | F(2, 78) = 3.89* |

| Caucasian (n [%]) | 63 (96.9) | 108 (94.7) | 37 (88.1) | χ2(2, N = 219) = 3.75 | 46 (95.8) | 25 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | χ2(2, N = 78) = 1.37 |

| Maternal college+ (n [%]) | 28 (47.5) | 53 (51.0) | 24 (58.5) | χ2(2, N = 202) = 1.21 | 24 (57.1) | 11 (50.0) | 3 (75.0) | χ2(2, N = 66) = 0.93 |

| Health (M [SD]) | 4.08 (0.94) | 3.82 (0.99) | 3.93 (0.87) | F(2, 218) = 1.46 | 3.96 (1.05) | 3.84 (1.07) | 3.00 (1.63) | F(2, 78) = 2.27 |

| Education (M [SD]) | 0.51 (0.57) | 0.39 (0.57)c | 0.70 (0.65) | F(2, 180) = 3.53* | 1.57 (0.99)b,c | 1.11 (0.57) | 0.60 (0.55) | F(2, 64) = 3.40* |

| Functional skills (M [SD]) | 125.58 (13.83)b,c | 117.65 (17.81)c | 108.26 (27.73) | F(2, 218) = 12.14** | 138.41 (13.39) | 135.23 (12.01) | 132.86 (11.84) | F(2, 74) = 0.86 |

| Ability to interact (M [SD]) | 2.45 (0.04)c | 2.19 (0.88)c | 1.72 (0.80) | F(2, 222) = 10.27** | 2.63 (1.04)b,c | 1.92 (0.70) | 1.57 (0.54) | F(2, 78) = 7.36** |

| Mental health problems (M [SD]) | 2.61 (1.52) | 2.86 (1.45) | 2.93 (1.51) | F(2, 214) = 0.78 | 1.28 (1.28) | 2.09 (0.90)a | 2.67 (0.82)a | F(2, 74) = 6.40** |

Note. F/χ2 values = results of one-way analysis of variance or chi-square test. % = column percentages.

p <.05.

p <.01. Boldfaced numbers also denote statistical significance.

Higher than “Considerable” at p <.05.

Higher than “Some” at p <.05.

Higher than “None” at p <.05.

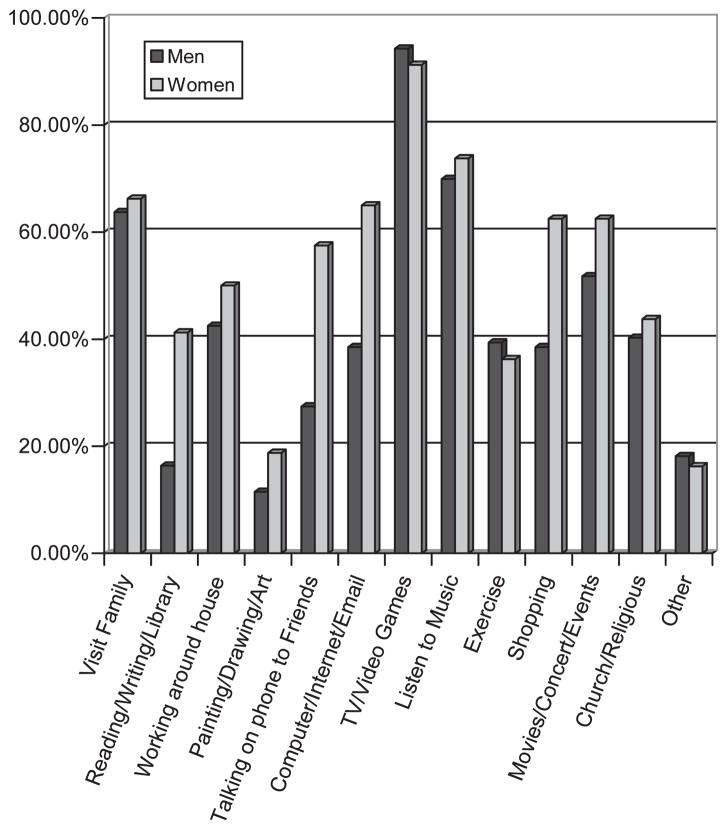

Adult Characteristics by Dimension of Adult Life: Leisure Activity

Figure 2 presents the percentage of men and women who participated in various types of leisure activities. The most common leisure activities for both men and women were watching TV or playing video games and listening to music. The least common leisure activity for both men and women was painting, drawing, or doing artwork. Women were more likely than men to participate in reading, writing, or going to the library, χ2(1, N = 303) = 3.43, p = .03; playing on the computer–Internet or e-mailing, χ2(1, N = 329) = 3.43, p = .03; and shopping, χ2(1, N = 303) = 6.43, p = .01.

Figure 2.

Percentage of men and women with fragile X syndrome participating in types of leisure activities.

Table 7 displays the results from the one-way ANOVAs and chi-square tests, which examined differences in characteristics of men and women by participation in leisure activities. In contrast to the extensive pattern of differences evident for the other dimensions of adult life, there were significant differences in only three characteristics by participation in leisure activities: age, functional skills, and ability to interact appropriately. Men who participated in six or more leisure activities had higher functional skills and a greater ability to interact appropriately than men who participated in fewer leisure activities. Women who participated in the fewest number of leisure activities (0–2 activities) were older than women who participated in three or more leisure activities.

Table 7.

Characteristics of Adults by Dimension of Adult Life: Leisure Activities

| Variable | Men

|

Women

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >6 activities (n = 113) | 3–5 activities (n = 83) | 0–2 activities (n = 30) | F/χ2 value | >6 activities (n = 58) | 3–5 activities (n = 19) | 0–2 activities (n = 3) | F/χ2 value | |

| Age in years (M [SD]) | 30.40 (7.17) | 32.35 (8.85) | 31.61 (9.17) | F(2, 224) = 1.41 | 29.55 (6.25) | 27.97 (5.95) | 48.23 (1.73)a,b | F(2, 78) = 10.44** |

| Caucasian (n [%]) | 98 (97.0) | 89 (92.7) | 26 (89.7) | χ2(2, N = 224) = 2.99 | 45 (97.8) | 31 (96.9) | 2 (100.0) | χ2(2, N = 78) = 0.12 |

| Maternal college+ (n [%]) | 54 (56.8) | 43 (50.0) | 9 (36.0) | χ2(2, N = 204) = 3.57 | 24 (58.5) | 12 (48.0) | 2 (100.0) | χ2(2, N = 66) = 2.33 |

| Health (M [SD]) | 4.00 (0.99) | 3.86 (0.90) | 3.72 (1.00) | F(2, 223) = 1.11 | 4.00 (1.08) | 3.66 (1.21) | 3.00 (0.00) | F(2, 78) = 1.45 |

| Education (M [SD]) | 0.42 (0.52) | 0.55 (0.64) | 0.39 (0.50) | F(2, 182) = 1.30 | 1.44 (0.97) | 1.25 (0.84) | 1.50 (0.71) | F(2, 64) = 0.38 |

| Functional skills (M [SD]) | 122.57 (14.71)c | 116.17 (18.71)c | 107.20 (26.34) | F(2, 223) = 8.66*** | 138.20 (13.69) | 134.38 (11.48) | 148.00 (0.00) | F(2, 74) = 1.62 |

| Ability to interact (M [SD]) | 2.20 (0.88)c | 1.72 (0.80)c | 1.69 (0.85) | F(2, 222) = 9.32*** | 2.43 (1.07) | 2.16 (0.85) | 2.00 (1.41) | F(2, 78) = 0.85 |

| Mental health problems (M [SD]) | 2.84 (1.31) | 2.77 (1.39) | 1.82 (1.62) | F(2, 216) = 0.30 | 1.44 (1.31) | 2.00 (1.02) | 1.00 (1.41) | F(2, 74) = 0.13 |

Note. F/χ2 values = results of one-way analysis of variance or chi-square test. % = column percentages.

p <.05.

p <.01. Boldfaced numbers also denote statistical significance.

Higher than “>6 activities” at p <.05.

Higher than “3–6 activities” at p <.05.

Higher than “0–2 activities” at p <.05.

Predictors of Independence in Adult Life

Hierarchical linear regressions were conducted to determine the relative strength of adult characteristics on the overall composite measure of independence. Given the relatively small number of women with complete data on our dimensions of adult life, only the key characteristics of interest (functional skills, ability to interact appropriately, and co-occurring mental health conditions) were included in the regression models. To determine the impact of specific co-occurring mental health conditions (inattention, hyperactivity, affect problems, aggression, self-injury, and autism spectrum disorder), each condition was separately entered into the regression models. Background characteristics were not included in the models. This decision was based on the large percentage (23.48%) of missing data for education and exploratory analyses showing that the remaining background characteristics (maternal education, age, race, and health) were not significantly related to the overall composite measure of independence after accounting for the other characteristics.

Table 8 presents the results of the regression models. For men, the strongest predictor of independence in adult life was functional skills, followed by ability to interact appropriately. The presence of autism spectrum disorder in addition to fragile X syndrome was also significantly negatively related to overall independence in adult life. The model accounted for 34% of the variance in independence in adult life for men. For women, the strongest predictor of independence in adult life was ability to interact appropriately. The presence of affect problems in addition to fragile X syndrome was also significantly negatively related to overall independence in adult life for women, and there was a trend for functional skills to predict overall independence. The model accounted for 37% of the variance in independence in adult life for women.

Table 8.

Regression Predicting the Overall Composite Measure of Independence in Adult Life

| Variable | Men (n = 181) | Women (n = 66) |

|---|---|---|

| Functional skills | .47*** | .25† |

| Ability to interact | .27*** | .40** |

| Inattention | .02 | .01 |

| Hyperactivity | −.02 | .19† |

| Affect problems | −.03 | −.32* |

| Aggression | −.11 | −.03 |

| Self-injury | .06 | .01 |

| Autism spectrum disorder | −.15* | .11 |

| F | 12.85*** | 5.81*** |

| R2 | .34 | .37 |

p <.10.

p <.05.

p <.01.

p <.001. Boldfaced numbers also denote statistical significance.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present study offers the first large-scale examination of the adult lives of men and women with the full mutation of the FMR1 gene. Findings from this study serve as the first benchmark of outcomes in adult life for these men and women that should inform the goals, programs, and policy of organizations (e.g., WHO) and government agencies (e.g., U.S. Department of Health and Human Services) that are responsible for improving the lives of adults with fragile X syndrome. Consistent with the genetic pattern of FXS (Tassone et al., 2000), women had a less impaired profile in adult life than men. More than one third of women with fragile X syndrome lived independently, often with a spouse or romantic partner, and required no assistance with activities of daily living. The large majority of women had at least a high school diploma, almost half had full-time jobs (and typically received benefits from their job), and the majority had many friends and participated in many (≥6) leisure activities. In contrast, only 10.10% of men with fragile X syndrome lived independently, only 1 (0.34%) lived with a spouse or romantic partner, and the majority needed moderate to considerable assistance with activities of daily living and did not have a high school diploma. Only one fifth of men had full-time jobs, most did not receive benefits from their job, less than one third had developed many friends, and only half participated in many leisure activities. Overall, 43.8% of women with fragile X syndrome, but only 9.1% of men, achieved a high or very high level of independence in adult life.

Findings from the present study reveal factors related to independence in adult life for men and women with fragile X syndrome that have important implications for designing interventions and services. Socioeconomic characteristics were generally not associated with independence in adult life with the exception of employment, which matched for the most part associations seen in the general population (i.e., minority status and lower maternal education related to less employment). However, age was predictive of a higher level of independence in several dimensions of adult life for women. This pattern suggests that women with fragile X syndrome may continue to enhance their independent skills from early to late adulthood. The one exception to this pattern was that older women with fragile X syndrome participated in fewer leisure activities than younger women. Neurodegeneration and health problems associated with aging in women with the premutation of the FMR1 gene, such as peripheral neuropathy and chronic muscle pain (e.g., Rodriguez-Revenga et al., 2009), may similarly affect women with the full mutation of the FMR1 gene and hinder participation in common leisure activities. This possibility should be the topic of future research. Services may be needed to find ways to modify leisure activities to fit the abilities of aging women with fragile X syndrome and facilitate engagement in these activities. The only dimension of adult life associated with age for men with fragile X syndrome was residential setting; men living in group homes were the oldest, followed by men living independently, with men co-residing with parents being the youngest. This age association may reflect changes in public policies focused on increasing independent living for adults with intellectual disability (versus group home living).

As predicted, independence in adult life was predicted by functional level for men with fragile X syndrome; level of functional skills was the strongest predictor of the overall composite measure of independence in our regression models. Functional skills have similarly been shown to be a strong correlate of a variety of outcomes in adult life using heterogeneous samples of adults with intellectual disability (e.g., Braddock et al., 2004; Emerson & McVilly, 2004; Robertson et al., 2001). This finding suggests that services for adult men with fragile X syndrome should focus on teaching functional skills (e.g., hygiene and grooming, everyday household living skills, communication skills) to foster independence in adult life. In contrast, level of functional skills was less important for predicting outcomes in adult life for women with fragile X syndrome. Instead, for women, ability to interact appropriately was the strongest predictor of the overall composite measure of independence for women in the regression models. Thus, for adult women with fragile X syndrome, services focused on enhancing interpersonal skills may be best, such as social perception and the ability to relate to others. Behind functional skills, ability to interact appropriately was also an important correlate of overall independence in adult life for men with fragile X syndrome and, thus, should also be targeted in services for this group.

Given the extent of limitations in interpersonal skills, it is not surprising that the most common leisure activities for both men and women with fragile X syndrome, watching television or playing video games and listening to music, were solitary and passive in nature. Thus, there appears to be a strong need for services to facilitate participation in social leisure activities. Interestingly, for men, friendships were most strongly related to leisure activities. Thus, a pathway to fostering friendships for men with fragile X syndrome may be to encourage involvement in social leisure activities with others, such as going on outings, shopping, or taking a walk. For women, friendships were most strongly related to employment, followed by residence. Thus, having a full-time job and living independently may be important avenues for building friendships for women with fragile X syndrome.

Education was positively related to independence in adult life for both men and women with fragile X syndrome. The one exception to this pattern was that having no friends was related to having more education for men with fragile X syndrome. Men who receive a high school diploma and/or pursue postsecondary vocational training or education may have difficulty relating to their typically developing peers but not quite fit in with their lower functioning peers with intellectual disabilities. Thus, services aimed at bridging the gap between these higher functioning men with fragile X syndrome and their peer groups may be needed. Such services could include finding commonalities in the interests and hobbies (e.g., joining a bowling or softball league) of higher functioning adults with fragile X syndrome and their peers.

The present study indicates that adulthood is marked by an alarmingly high prevalence of co-occurring mental health problems for both men and women with fragile X syndrome. Most of the men had been diagnosed with or treated for inattention (82.7%), hyperactivity (64.3%), and affect problems (71.7%). Many of the women also had these particular mental health problems (66.3%, 27.1%, and 58.8%, respectively). More than one third of men had also been treated for aggression (43.0%), self-injury (47.3%), and autism spectrum disorder (37.3%) problems. These findings highlight the critical need for continued mental health services for individuals with fragile X syndrome into adulthood. Although adults with fragile X syndrome evidence similar types of co-occurring mental health problems as children and adolescence with fragile X syndrome (Bailey et al., 2008; Symons et al., 2003), these problems may present differently in adulthood and require different interventions to address the unique tasks of adulthood (e.g., having a job or living in a group home). These issues should be the focus of future research.

As expected, men and women with fragile X syndrome who were diagnosed or treated with a larger number of co-occurring mental health conditions had less independence in adult life. The presence of autism spectrum disorder was an important predictor of overall independence in adult life for men, even after controlling for functional skills. Thus, consistent with previous findings (e.g., Howlin et al., 2004), autism symptoms are related to more limited independence in adult life for men with fragile X syndrome. In contrast, for women with fragile X syndrome, affect problems (depression and/or anxiety) were significant predictors of overall independence in adult life. These findings indicate that that it is critical for services for adults with fragile X syndrome to be aimed at co-occurring mental health conditions, as these are critical to their independence in adult life, with particular focus on autism symptoms for men and affect problems for women with fragile X syndrome.

There are several limitations to this study. Our sample of adults with fragile X syndrome came from a large national survey study of families with fragile X syndrome, and the families in this study were predominately Caucasian, highly educated, and had relatively high household incomes. The present study may have underestimated the level of independence of women with fragile X syndrome in adult life, as the families of high-functioning women may have been less likely to participate in this survey. Results from this study are based on parent report of their adult son or daughter’s functioning and abilities, and whether the son or daughter had been diagnosed or treated for various co-occurring mental health conditions, as opposed to clinician ratings. There was also a relatively large amount of missing data in the survey and, in particular, in the reporting of education for adults with fragile X syndrome and their mothers. Some of these missing data appear to be for lower functioning adults with fragile X syndrome and may have stemmed from confusion regarding whether the son or daughter received a high school completion certificate. Therefore, the few analyses including this information may not reflect the outcomes of these lower functioning adults with fragile X syndrome.

Furthermore, detailed information regarding each dimension of adult life was not obtained in the survey study. For example, the extent to which adults with fragile X syndrome were employed in sheltered workshops versus community jobs is unknown. In addition, parents may also have used different criteria when rating friendships. Some parents may have counted social acquaintances and/or family and caregivers as friends, whereas others may have only considered intimate relationships with people outside of the family or care providers. Last, in this study we assessed a limited array of dimensions of adult life. Important aspects of adult life, such as the extent to which men and women with fragile X syndrome were married or had children, were not addressed in this study. In our sample, 20.54% of women with fragile X syndrome lived with a spouse or partner, and, thus, it is likely that some of these women were married and may have had children of their own. Moreover, our composite measure of independence in adult life assumed an equal weighting of the five dimensions (i.e., residence, employment, assistance needed in everyday life, friendships, and leisure activities). Although this is a good starting point, future studies will need to consider the relative importance of these dimensions for understanding success in adult life.

Even given these limitations, this study provides the first large-scale examination of adult life for men and women with the full mutation of the FMR1 gene. Men and women with fragile X syndrome had very different adult lives. Level of functional skills was the strongest predictor of independence in adult life for men, and ability to interact was the strongest predictor of independence in adult life for women. Co-occurring mental health problems were strong factors associated with outcomes in adult life for both men and women. Co-occurring autism spectrum disorder in addition to fragile X syndrome was a critical determinant of outcomes in adult life for men, whereas affect problems influenced outcomes in adult life for women. Findings indicate that services for adults with fragile X syndrome should not only be focused on teaching functional skills but should target improving interpersonal skills and managing co-occurring mental health conditions.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported in part by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Association for Prevention Teaching and Research (APTR; Cooperative Agreement U50/CCU300860, Project TS-1380 to D. Bailey), and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD; P30 HD03352 to M. Seltzer; T32 HD07489 to L. Abbedduto). The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of CDC, APTR, or NICHD. We thank the research collaborators and organizations who supported the recruitment of study participants and the families who completed the survey.

Contributor Information

Sigan L. Hartley, University of Wisconsin—Madison

Marsha Mailick Seltzer, University of Wisconsin—Madison.

Melissa Raspa, RTI International (Research Triangle Park, NC).

Murrey Olmstead, RTI International (Research Triangle Park, NC).

Ellen Bishop, RTI International (Research Triangle Park, NC).

Donald B. Bailey, Jr., RTI International (Research Triangle Park, NC)

References

- Abbeduto L, Brady N, Kover ST. Language development and fragile X syndrome: Profiles, syndrome-specificity, and within-syndrome differences. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 2007;13:36–46. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz M, Stathopulu E, Callias M, Taylor C, Oostra B, Willemsen R, et al. Clinical features of boys with fragile X permutations and intermediate alleles. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B, Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2003;121B:119–127. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.20030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DB, Hatton DDD, Tassone F, Skinner M, Taylor AK. Variability in FMRP and early development in males with fragile X syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2001;106:16–27. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2001)106<0016:VIFAED>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DB, Mesibov GB, Hatton GD, Clark RD, Roberts JE, Mayhew L. Autistic behavior in young boys with fragile X syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1998;28:499–508. doi: 10.1023/a:1026048027397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DB, Raspa M, Bishop E, Holiday DB. No change in age of diagnosis for fragile X syndrome: Findings from a national parent survey. Pediatrics. 2009;124:527–533. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DB, Raspa M, Bishop E, Olmsted M. The functional skills of individuals with fragile X syndrome: A lifespan, cross-sectional analysis. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2009;114:289–303. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-114.4.289-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DB, Raspa M, Olmsted M, Holiday DB. Co-occurring conditions associated with FMR1 gene variations: Findings form a national parent survey. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2008;146A:2060–2069. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MM, Molaison VA, Smull MW. Families caring for a young adult with mental retardation: Service needs and urgency of community living requests. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 1990;95:32–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braddock D, Rizzolo MC, Hemp R. Most employment services growth in developmental disabilities during 1988–2002 was in segregated settings. Mental Retardation. 2004;42:317–320. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(2004)42<317:MESGID>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bregman JD, Leckman JF, Ort SI. Fragile X syndrome: Genetic predisposition to psychopathology. Journal of Autism and Development Disabilities. 1988;18:34–54. doi: 10.1007/BF02212191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown WT. The molecular biology of fragile X mutation. In: Hagerman R, Hagerman PJ, editors. Fragile X syndrome: Diagnosis, treatment, and research. 3. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press; 2002. pp. 110–135. [Google Scholar]

- Cornish KJ, Turk J, Hagerman RJ. Annotation: The fragile X continuum: New advances and perspectives. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2008;52:469–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford DC, Acuna JM, Sherman SL. FMR1 and the fragile X syndrome: Human genome epidemiology review. Genetics in Medicine. 2001;3:359–371. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200109000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson E, McVilly K. Friendship activities of adults with intellectual disabilities in supported accommodations in Northern England. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2004;17:191–197. [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman PJ. The fragile X prevalence paradox. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2008;45:498–499. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.059055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman PJ, Berry-Kravis E, Kaufmann WE, Ono MY, Tartaglia N, Lachiewicz A, et al. Advances in the treatment of fragile X syndrome. Pediatrics. 2009;123:378–390. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ. The fragile X permutation: Into the phenotypic fold. Current Opinion in Genetics and Development. 2002;12:278–283. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00299-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SS, Burns DD, Lightbody AA, Reiss AL. Longitudinal changes in intellectual development in children with fragile X syndrome. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:927–939. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9223-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison P, Oakland R. Adaptive Behavior Assessment System—Second Edition (ABAS-II) San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Heller T, Factor A. Permanency planning for adults with mental retardation living with family caregivers. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 1991;96:167–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P, Goode S, Hutton J, Rutter M. Adult outcome for children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:212–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauss MW, Seltzer MM, Jacobson HT. Adults with autism living at home or in non-family settings: Positive and negative aspects of residential status. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2005;49:111–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2004.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loesch DZ, Huggins RM, Bui QM, Epstein JR, Taylor AK, Hagerman RJ. Effects of the deficits of fragile x mental retardation protein on cognitive status of fragile X males and females assessed by robust pedigree analysis. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2002;23:416–423. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200212000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckasson R, Borthwick-Duffy S, Buntix W, Coulter D, Craig E, Reeve A, et al. Mental retardation: Definition, classification, and systems of supports. 10. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Martorell A, Gutierrez-Recacha P, Pereda A, Ayuso-Mateos JL. Identification of personal factors that determine work outcomes for adults with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2008;52:1091–1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzocco MM, Baumgardner T, Freund LS, AL, Reiss AL. Social functioning among girls with Fragile X or Turner syndrome and their sisters. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1998;28:509–517. doi: 10.1023/a:1026000111467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passmore A, French D. Development and administration of a measure to assess adolescents’ participation in leisure activities. Adolescence. 2001;36:68–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philofsky A, Hepburn SL, Hayes A, Hagerman R, Rogers SJ. Linguistic and cognitive functioning and autism symptoms in young children with Fragile X syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2004;109:208–218. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2004)109<208:LACFAA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss AL, Freund L. Behavioral phenotype of Fragile X syndrome: DSM-III R autistic behavior in male children. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1990;43:35–41. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320430106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson J, Emerson E, Gregory N, Hatton C, Kessissoglou S, Hallam A, et al. Social networks of people with mental retardation in residential settings. Mental Retardation. 2001;39:201–214. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(2001)039<0201:SNOPWM>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Revenga L, Madrigal I, Pagonabarraga J, Xuncla M, Badenas C, Kulisevksy J, et al. Penetrance of FMR1 premutation associated pathologies in fragile X syndrome families. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2009;17:1359–1362. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SJ, Wehner EA, Hagerman R. The behavioral phenotype of fragile X: Symptoms of autism in very young children with fragile X syndrome, idiopathic autism and other developmental disorders. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2001;22:409–508. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200112000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeonsson RJ, Bailey DB. The ABILITIES Index. Chapel Hill, NC: FPG Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow SS, Cicchetti DV, Balla DA. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. 2. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan K, Hatton D, Hammer J, Sideris J, Hooper S, Ornstein P, et al. ADHD symptoms in children with FXS. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2006;140A:2275–2288. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symons FJ, Clark RD, Hatton DD, Skinner M, Bailey DB. Self-injurious behavior in young boys with fragile X syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2003;118A:115–121. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.10078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassone F, Hagerman RJ, Chamberlain WD, Hagerman PJ. Transcription of the FMRI gene in individuals with fragile X syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2000;97:195–203. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(200023)97:3<195::AID-AJMG1037>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2010: Understanding and improving health. 2. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability, and health. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2001. [Google Scholar]