Abstract

Background

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) is a pro-inflammatory cytokine upstream of many inflammatory cytokines. MIF is implicated in several acute and chronic inflammatory conditions. MIF's promoter region has functional single nucleotide polymorphisms that controls MIF expression and protein levels. Since increased plasma MIF levels are associated with cancer, studies have examined the association between Mif promoter polymorphisms and cancer. This study is a meta-analysis of the available studies on such an association.

Results

A total of 5 studies were included in this meta-analysis to include 1116 cases (cancer patients) and 1728 controls (no cancer). Carrying any C allele in the Mif -173 G/C promoter polymorphism resulted in a significantly greater risk for developing cancer [OR = 1.89 (1.15-3.11), p = 0.012)] when compared to the (G/G) genotype. Subgroup analysis revealed that this association was significant only for "solid" tumors (including gastric and prostate cancers) [OR = 2.67 (1.26-5.65), p = 0.010] but not for "non-solid" tumors (leukemia) [OR = 1.21 (0.95-1.55), p = 0.122]. Furthermore, when only prostate tumor studies were included in the analysis, the association became even stronger [OR = 3.72 (2.55-5.41), p < 0.0001].

Conclusions

Meta-analysis suggests there is an association between any C allele in the Mif -173 G/C promoter polymorphism and an increased risk of cancer, particularly for solid tumors. The association appeared stronger for prostate cancer, specifically. Future studies that include different types of cancers are needed to support and extend these observations.

Background

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) was the first cytokine identified nearly 50 years ago. At that time its described activity was as a soluble factor produced by T-lymphocytes that inhibited the directed migration of macrophages [1]. Since then, MIF is documented to be expressed by a broad variety of cells and tissues, including immune and non-immune cells [2,3]. Presently, MIF is considered a pleiotropic cytokine that is a central regulator of innate immunity and a regulator of inflammation since it is constitutively expressed and acts as an upstream regulator of many other inflammatory cytokines [4]. Experimental evidence has shown that MIF plays a critical role in immune and inflammatory diseases including sepsis [5], rheumatoid arthritis [6], delayed-type hypersensitivity [7], Crohn's disease [8] and gastric ulcer formation [9].

Because MIF is an important regulator of inflammation and given the established link between chronic inflammation and cancer [10], recent studies have examined the link between Mif mRNA expression and/or MIF protein levels and cancer [11]. Increased Mif mRNA expression in prostate tissue [12] and increased serum MIF protein levels [13] were first documented for prostate cancer patients. Other investigations corroborated these findings for prostate cancer [14,15] and extended the association between increased Mif mRNA and/or protein expression to other types of cancer [16-19]. Therefore, strong evidence has accumulated suggesting that MIF is an important link between inflammation and cancer [11]. Two regions within the Mif promoter contain functional polymorphisms that result in variable Mif mRNA amounts and subsequent protein production and high expressing promoter polymorphism genotypes are associated with increased risk of inflammatory disease [20,21]. A -173 G/C transversion results in a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) that was first described with higher frequency in arthritis patients [22,23]. Another functional promoter polymorphism was identified at position -794, where increasing copies of a CATT tetranucleotide repeat (5 to 8 copies, -794 CATT(5-8)) were also associated with increased disease severity in arthritis [20]. The association between these polymorphisms and disease has been extended to other inflammatory conditions including ulcerative colitis [24], peptic ulcer disease [25] and increased morbidity due to sepsis [26]. These studies thus suggest that an association exists between Mif promoter genotypes that result in increased MIF protein production and an increased risk of inflammatory disease. Similarly, studies examining the association between Mif promoter polymorphisms and cancer have reported an increased risk of cancer for patients with higher MIF protein producing promoter genotypes [3,27-30] while others have reported a lack of association [31]. The aim of this study is to conduct a meta-analysis of all available studies that examine the association between Mif promoter polymorphism and the incidence of cancer.

Results

Studies Eligibility

After a literature search and selection based on inclusion criteria as described in the methods, five studies were identified for meta-analysis [27-31]. Table 1 lists these studies and their characteristics. The data for the meta-analysis included 1,116 cancer cases and 1,728 controls (no cancer). Mif -173 G/C polymorphism groups were divided as G/G (control comparison) and any C/X (i.e. G/C or C/C). All studies were published between 2005 and June 2011. Two studies were conducted on leukemia patients and were thus classified as "non-solid tumors" whereas the remaining three studies examined either gastrointestinal or prostate tumors and thus were classified as "solid tumors".

Table 1.

Studies included in meta-analysis

| Studies | Year | Cases (Cancer) | Controls (No cancer) | Tumor Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any C | G/G | Any C | G/G | |||

| Ziino | 2005 | 34 | 117 | 78 | 277 | Leukemia |

| Meyer-Siegler | 2007 | 76 | 55 | 29 | 99 | Prostate |

| Arisawa | 2008 | 106 | 123 | 167 | 261 | Gastric |

| Ding | 2008 | 93 | 166 | 45 | 256 | Prostate |

| Xue | 2010 | 110 | 228 | 147 | 369 | Leukemia |

Studies were selected from published articles gathered from a search of the literature using PubMed and meeting the selection criteria (as listed in Methods).

Meta-analysis results

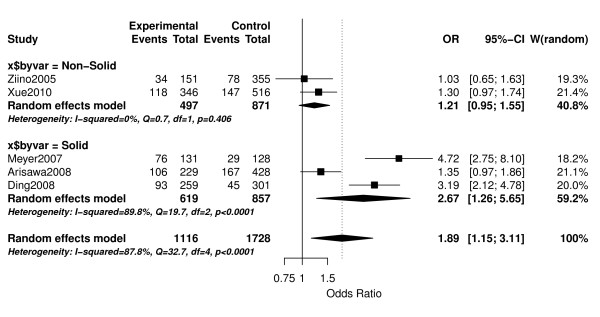

Meta-analysis of the 5 eligible studies showed that individuals that carry any C allele in the Mif promoter region at position -173 had a significantly higher risk for developing cancer when compared to those that had the G/G genotype [OR = 1.89 (1.15-3.11), p = 0.0116]. However, the heterogeneity was very large (I2 = 87.8%, p < 0.001; Figure 1). Subgroup analysis showed that in patients with "Non-solid" tumors, there was no significant association between the C/X genotype and cancer [OR = 1.21 (0.95-1.55), p = 0.122; Figure 1], while a significant association was still detected for patients with "Solid" tumors [OR = 2.67 (1.26-5.65), p = 0.0105; Figure 1]. Since even within the "Solid" tumor subgroup, heterogeneity was still very large (I2 = 89.8%, p < 0.001), further subgrouping to only those studies dealing with prostate cancer was carried out. When limiting the analysis to only prostate cancer studies, the heterogeneity decreased substantially to low levels (I2 = 22.7%, p = 0.250) and the association between the C genotype of the Mif promoter polymorphism and cancer was even greater [OR = 3.72 (2.55-5.41), p < 0.0001].

Figure 1.

Meta-analysis of Mif promoter region polymorphism (-173 G/C) and cancer. Point estimates of the Odds Ratio (OR) and accompanying 95% confidence intervals are shown for each study. Overall analysis using Random effects model and subgroup analyses for patients with "Non-Solid" vs. "Solid" tumors are shown.

Discussion

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor is a pro-inflammatory cytokine shown to be upstream of and able to upregulate the production of other inflammatory cytokines [4]. Consequently, MIF is a central modulator of inflammation and a possible link between chronic inflammation and cancer [10]. Several studies have examined the relationship between increased Mif mRNA expression and cancer [12-19]. Mif promoter polymorphisms that increase Mif mRNA expression also result in increased MIF protein production [21,27] and recent studies have established an association between increased MIF serum levels and increased risk for cancer [13,14,32]. The association between high expressing functional Mif promoter polymorphisms and prostate cancer appears biologically plausible in view of the documented association between elevated serum MIF protein levels and prostate cancer. MIF's ability to override p53 tumor suppressor activity, sustain MAP (ERK-1/2) kinase phosphorylation and induce the formation of other proinflammatory mediators within the tumor microenvironment [33-36] likely contribute to tumor promotion. The present meta-analysis study is the first, to our knowledge, to critically review published studies on the association between Mif promoter polymorphisms and the incidence of cancer. Our meta-analysis focused on the (-173 G/C) Mif promoter region polymorphism and cancer since very few studies have examined the association between the number of -794 CATT repeats and cancer. From the 5 studies included in our analysis, our results showed that there is a significant association between having any C allele at the -173 site within the Mif promoter and cancer. Because of large heterogeneity in the results, further sub-group analysis showed that there is a strong association between Mif promoter genotypes containing a C allele and the development of solid tumors [OR = 2.67 (1.26-5.65), p = 0.0105], while no association was observed in non-solid tumors [OR = 1.21 (0.95-1.55), p = 0.122]. Lastly, analysis of studies dealing only with prostate cancer patients showed the strongest association between cancer incidence and the C allele Mif promoter genotype [OR = 3.72 (2.55-5.41)]. Thus, Mif promoter genotype may serve as a useful prostate cancer risk marker.

Some limitations of this meta-analysis study should be considered. First, the number of studies included was low, reflecting the small number of published studies. Second, heterogeneity was large in the global analysis, which justified subgroup analysis but made the number of studies in each subgroup even smaller. Given these two limitations, the link between the C allele Mif promoter genotype and prostate cancer awaits validation by future studies. Similarly, whether this link also extends to other solid tumors needs to assessed by future studies. Third, the analysis was based on individual unadjusted OR from each of the studies included, while a better estimate may be obtained by adjusting for potentially contributing factors. For example, Arisawa et al [28] reported an association between the -173C Mif allele and gastric cancer only in patients older than 60 years. Therefore, the inclusion of other factors (such as age) may yield a more accurate estimate of the association. Finally, the focus of the current analysis was limited to the Mif -173 G/C promoter and did not include -794 CATT repeat polymorphisms due to the very small numbers of studies. Two recent studies described an association between higher MIF producing genotypes (greater number of CATT repeats) and gastric [28] and prostate cancer [27] respectively. These observations should be confirmed by additional studies and the relationship between the two functional Mif promoters and carcinogenesis remains to be investigated.

Conclusions

The current meta-analysis results suggest that the -173C Mif promoter polymorphism is associated with an increase in the risk of solid tumor cancer, particularly for prostate cancer. More studies that include a larger variety of cancers are needed to confirm the association of high expressing Mif promoter polymorphisms and prostate cancer.

Methods

Identification and selection of relevant studies

In order to identify all published articles that examined the association between Mif promoter polymorphisms and cancer, a literature search was conducted of the PubMed database through June 2011 using the following MeSH terms and Keywords: 'Macrophage migration inhibitory factor', 'polymorphism' and 'cancer' or 'neoplasm'. Studies were included in the meta-analysis if they met the following criteria: (a) case-control cancer study, (b) cancer diagnosis was confirmed pathologically, and (c) written in English.

Data extraction

The two investigators independently examined the list of studies for inclusion eligibility, extracted data and reached a consensus on all the items. Meta-analysis was restricted to examining the results of studies dealing with the -173 G/C SNP since few studies examined -794 CATT repeat. The following information was extracted from each eligible study: first author, year of publication, number of cases and controls, Mif polymorphisms divided as: GG, any C (CC and CG) for cases and controls, type of cancer: either solid tumor or non-solid tumor.

Statistical Analysis

The effect of association between Mif polymorphism (G/G vs any C; i.e. C/G, C/C) and cancer was calculated as odds ratio (OR) with the corresponding 95% confidence interval [37]. The summary effect was calculated using the Random Effects (RE; Dersimonian and Laird) model [38]. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the Q-test and the I2 test [39]. Heterogeneity was classified as: low heterogeneity (I2 < 25%); moderate (I2 = 25-50%) or large (I2 > 50%). Heterogeneity was considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. Sub-group analysis further examined the effects in studies investigating non-solid tumors vs. solid tumors. Statistical analysis was conducted using R (version 2.12; http://www.r-project.org) and the meta [40] and metafor [41] packages.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

PLV and KLMS conceived the study, selected the studies to be included, conducted the analysis and prepared the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Pedro L Vera, Email: pvera@health.usf.edu.

Katherine L Meyer-Siegler, Email: Katherine.Siegler@va.gov.

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development (R&D), Biomedical Laboratory R&D and the Bay Pines Foundation (PLV; KLMS).

References

- Bloom BR, Bennett B. Mechanism of a reaction in vitro associated with delayed-type hypersensitivity. Science. 1966;153(731):80–2. doi: 10.1126/science.153.3731.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baugh JA, Bucala R. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(1 Supp):S27–S35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieb G, Merk M, Bernhagen J, Bucala R. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF): a promising biomarker. Drug News Perspect. 2010;23(4):257–264. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2010.23.4.1453629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami H, Akbar SM, Matsui H, Horiike N, Onji M. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor activates antigen-presenting dendritic cells and induces inflammatory cytokines in ulcerative colitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;128(3):504–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01838.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Abed Y, Dabideen D, Aljabari B, Valster A, Messmer D, Ochani M, Tanovic M, Ochani K, Bacher M, Nicoletti F, Metz C, Pavlov VA, Miller EJ, Tracey KJ. ISO-1 binding to the tautomerase active site of MIF inhibits its pro-inflammatory activity and increases survival in severe sepsis. JBC. 2005;280(44):36541–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500243200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leech M, Metz C, Hall P, Hutchinson P, Gianis K, Smith M, Weedon H, Holdsworth SR, Bucala R, Morand EF. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor in rheumatoid arthritis: evidence of proinflammatory function and regulation by glucocorticoids. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(8):1601–8. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199908)42:8<1601::AID-ANR6>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown FG, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Chadban SJ, Dowling J, Jose M, Metz CN, Bucala R, Atkins RC. Urine macrophage migration inhibitory factor concentrations as a diagnostic tool in human renal allograft rejection. Transplantation. 2001;71(12):1777–83. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200106270-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong YP, Abadia-Molina AC, Satoskar AR, Clarke K, Rietdijk ST, Faubion WA, Mizoguchi E, Metz CN, Alsahli M, ten Hove T, Keates AC, Lubetsky JB, Farrell RJ, Michetti P, van Deventer SJ, Lolis E, David JR, Bhan AK, Terhorst C. Development of chronic colitis is dependent on the cytokine MIF. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(11):1061–6. doi: 10.1038/ni720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang XR, Chun Hui CW, Chen YX, Wong BC, Fung PC, Metz C, Cho CH, Hui WM, Bucala R, Lam SK, Lan HY, Chun B, Wong Y. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor is an important mediator in the pathogenesis of gastric inflammation in rats. Gastroenterology. 2001;121(3):619–30. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.27205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Cancer and inflammation: implications for pharmacology and therapeutics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87(4):401–406. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy H, Mawhinney L, Donnelly SC. Inflammation and cancer: macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF)-the potential missing link. QJM. 2010;103(11):831–836. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcq148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Siegler K, Fattor RA, Hudson PB. Expression of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in the human prostate. Diagnostic molecular pathology: the American journal of surgical pathology, part B. 1998;7:44–50. doi: 10.1097/00019606-199802000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Siegler KL, Bellino MA, Tannenbaum M. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor evaluation compared with prostate specific antigen as a biomarker in patients with prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94:1449–56. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Siegler KL, Iczkowski KA, Vera PL. Further evidence for increased macrophage migration inhibitory factor expression in prostate cancer. BMC cancer. 2005;5:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-5-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Vecchio MT, Tripodi SA, Arcuri F, Pergola L, Hako L, Vatti R, Cintorino M. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor in prostatic adenocarcinoma: correlation with tumor grading and combination endocrine treatment-related changes. The Prostate. 2000;45:51–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0045(20000915)45:1<51::AID-PROS6>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendon BE, Roger T, Teneng I, Zhao M, Al-Abed Y, Calandra T, Mitchell RA. Regulation of human lung adenocarcinoma cell migration and invasion by macrophage migration inhibitory factor. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(41):29910–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704898200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verjans E, Noetzel E, Bektas N, Schutz AK, Lue H, Lennartz B, Hartmann A, Dahl E, Bernhagen J. Dual role of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) in human breast cancer. BMC cancer. 2009;9:230. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JM, Coletta PL, Cuthbert RJ, Scott N, MacLennan K, Hawcroft G, Leng L, Lubetsky JB, Jin KK, Lolis E, Medina F, Brieva JA, Poulsom R, Markham AF, Bucala R, Hull MA. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor promotes intestinal tumorigenesis. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(5):1485–503. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasasever V, Camlica H, Duranyildiz D, Oguz H, Tas F, Dalay N. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor in cancer. Cancer Invest. 2007;25(8):715–9. doi: 10.1080/07357900701560695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baugh JA, Chitnis S, Donnelly SC, Monteiro J, Lin X, Plant BJ, Wolfe F, Gregersen PK, Bucala R. A functional promoter polymorphism in the macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) gene associated with disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis. Genes and immunity. 2002;3(3):170–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donn R, Alourfi Z, Zeggini E, Lamb R, Jury F, Lunt M, Meazza C, De Benedetti F, Thomson W, Ray D. A functional promoter haplotype of macrophage migration inhibitory factor is linked and associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(5):1604–10. doi: 10.1002/art.20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donn RP, Shelley E, Ollier WE, Thomson W. A novel 5'-flanking region polymorphism of macrophage migration inhibitory factor is associated with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(8):1782–5. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200108)44:8<1782::AID-ART314>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donn R, Alourfi Z, De Benedetti F, Meazza C, Zeggini E, Lunt M, Stevens A, Shelley E, Lamb R, Ollier WE, Thomson W, Ray D. Mutation screening of the macrophage migration inhibitory factor gene: positive association of a functional polymorphism of macrophage migration inhibitory factor with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(9):2402–9. doi: 10.1002/art.10492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiroeda H, Tahara T, Nakamura M, Shibata T, Nomura T, Yamada H, Hayashi R, Saito T, Yamada M, Fukuyama T, Otsuka T, Yano H, Ozaki K, Tsuchishima M, Tsutsumi M, Arisawa T. Association between functional promoter polymorphisms of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) gene and ulcerative colitis in Japan. Cytokine. 2010;51(2):173–177. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiroeda H, Tahara T, Shibata T, Nakamura M, Yamada H, Nomura T, Hayashi R, Saito T, Fukuyama T, Otsuka T, Yano H, Ozaki K, Tsuchishima M, Tsutsumi M, Arisawa T. Functional promoter polymorphisms of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in peptic ulcer diseases. Int J Mol Med. 2010;26(5):707–711. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann LE, Book M, Hartmann W, Weber SU, Schewe JC, Klaschik S, Hoeft A, Stüber F. A MIF haplotype is associated with the outcome of patients with severe sepsis: a case control study. J Transl Med. 2009;7:100. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Siegler KL, Vera PL, Iczkowski KA, Bifulco C, Lee A, Gregersen PK, Leng L, Bucala R. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) gene polymorphisms are associated with increased prostate cancer incidence. Genes and immunity. 2007;8(8):646–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arisawa T, Tahara T, Shibata T, Nagasaka M, Nakamura M, Kamiya Y, Fujita H, Yoshioka D, Arima Y, Okubo M, Hirata I, Nakano H, De la Cruz V. Functional promoter polymorphisms of the macrophage migration inhibitory factor gene in gastric carcinogenesis. Oncology reports. 2008;19:223–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding GX, Zhou SQ, Xu Z, Feng NH, Song NH, Wang XJ, Yang J, Zhang W, Wu HF, Hua LX. The association between MIF-173 G¿C polymorphism and prostate cancer in southern Chinese. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100(2):106–110. doi: 10.1002/jso.21304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y, Xu H, Rong L, Lu Q, Li J, Tong N, Wang M, Zhang Z, Fang Y. The MIF -173G/C polymorphism and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a Chinese population. Leuk Res. 2010;34(10):1282–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2010.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziino O, D'Urbano LE, Benedetti FD, Conter V, Barisone E, Rossi GD, Basso G, Aricò M. The MIF-173G/C polymorphism does not contribute to prednisone poor response in vivo in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2005;19(12):2346–2347. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramaki M, Miyake H, Yamada Y, Hara I. Clinical utility of serum macrophage migration inhibitory factor in men with prostate cancer as a novel biomarker of detection and disease progression. Oncology reports. 2006;15:253–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerle-Rowson G, Petrenko O, Metz CN, Forsthuber TG, Mitchell R, Huss R, Moll U, Muller W, Bucala R. The p53-dependent effects of macrophage migration inhibitory factor revealed by gene targeting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(16):9354–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533295100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell RA, Metz CN, Peng T, Bucala R. Sustained mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 activation by macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF). Regulatory role in cell proliferation and glucocorticoid action. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(25):18100–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.18100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han I, Lee MR, Nam KW, Oh JH, Moon KC, Kim HS. Expression of macrophage migration inhibitory factor relates to survival in high-grade osteosarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(9):2107–2113. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0333-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salsman VS, Chow KKH, Shaffer DR, Kadikoy H, Li XN, Gerken C, Perlaky L, Metelitsa LS, Gao X, Bhattacharjee M, Hirschi K, Heslop HE, Gottschalk S, Ahmed N. Crosstalk between Medulloblastoma Cells and Endothelium Triggers a Strong Chemotactic Signal Recruiting T Lymphocytes to the Tumor Microenvironment. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e20267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf B. On estimating the relation between blood group and disease. Ann Hum Genet. 1955;19(4):251–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1955.tb01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau J, Ioannidis JP, Schmid CH. Quantitative synthesis in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(9):820–826. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-9-199711010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer G. meta: Meta-Analysis with R. 2010. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=meta [R package version 1.6-1]

- Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software. 2010;36(3):1–48. [Google Scholar]