Abstract

Background: Vitamin D receptor (VDR) and the megalin gene polymorphism's link with longitudinal cognitive change remains unclear.

Objective: The associations of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for VDR [rs11568820 (CdX-2:T/C), rs1544410 (BsmI:G/A), rs7975232 (ApaI:A/C), rs731236 (TaqI:G/A)], and Megalin (rs3755166:G/A; rs2075252:C/T; rs4668123:C/T) genes with longitudinal cognitive performance changes were examined.

Design: Data from 702 non-Hispanic white participants in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging were used. Longitudinal annual rates of cognitive change (LARCCs) between age 50 y and the individual mean follow-up age were predicted with linear mixed models by using all cognitive score time points (prediction I) or time points before dementia onset (prediction II). Latent class, haplotype, and ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analyses were conducted.

Results: Among key findings, in OLS models with SNP latent classes as predictors for LARCCs, Megalin2 [rs3755166(–)/rs2075252(TT)/rs4668123(T−)] compared with Megalin1 [rs3755166(–)/rs2075252(CC)/rs4668123(–)] was associated with greater decline among men for verbal memory (prediction II). Significant sex differences were also found for SNP haplotype (SNPHAP). In women, VDR1 [BsmI(G−)/ApaI(C−)/TaqI(A−); baT] was linked to a greater decline in category fluency (prediction I: β = −0.031, P = 0.012). The Megalin1 SNPHAP (GCC) was related to greater decline among women for verbal memory, immediate recall [California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT), List A; prediction II: β = −0.043, P = 0.006) but to slower decline among men for delayed recall (CVLT-DR: β > 0, P < 0.0125; both predictions). In women, the Megalin2 SNPHAP (ACC) was associated with slower decline in category fluency (prediction II: β = +0.026, P = 0.005). Another finding was that Megalin SNP rs3755166:G/A was associated with greater decline in global cognition in both sexes combined and in verbal memory in men.

Conclusion: Sex-specific VDR and Megalin gene variations can modify age-related cognitive decline among US adults.

INTRODUCTION

Vitamin D's biological effect on the brain function was shown in recent studies, specifically in terms of neuroprotection (mainly mediated by calcium, nerve growth factor, and neurotrophin 3), immunomodulation, and detoxification (1–9). A few receptors and binding proteins mediate vitamin D functions in both animals and humans. VDR4, a part of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily, is expressed in many organs. Whereas vitamin D deficiency in animals was associated with changes in brain morphology (10), locomotion (11, 12), learning, and memory (13), a dysfunctional VDR was linked to anxiety-like behavior in mice (14, 15). Among humans, vitamin D deficiency was related to mood disorders and poor cognitive functioning (16, 17). However, only a handful of recent studies have examined VDR gene polymorphisms in relation to cognition among older adults (18, 19), and none so far have examined longitudinal change in cognitive abilities.

Another endocytic vitamin D binding receptor, known as megalin or LRP2, is expressed in many epithelial cells including those of the choroid plexus (ie, blood-brain barrier) and belongs to the LDL receptor family (20, 21). Megalin also binds apoE (22), a protein involved in redistribution of cholesterol for nerve repair (23). In fact, the ApoE genotype was associated with cognitive impairment, decline, and dementia, particularly AD (24, 25), as well as a number of neurobiological factors implicated in dementia: β-amyloid deposition, tangle formation, oxidative stress, lipid homeostasis dysregulation, synaptic plasticity loss, and cholinergic dysfunction (26). Importantly, megalin in choroid plexus directly participates in clearance of β-amyloids (27–30) and is involved in neuroprotection by binding and transcytosis of insulin-like growth factor I (30). The expression of megalin is regulated by serum vitamin D and vitamin A (31). Vitamin D requires another protein, namely vitamin D binding protein, to bind to megalin and enter cells (32–35). Despite the biologically plausible involvement of megalin in AD pathogenesis, only 2 recent studies thus far have examined the relation between megalin gene polymorphisms and incident AD (20, 36).

To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study to test the associations of VDR and megalin SNP, SNP LCs, and SNPHAPs with longitudinal changes in cognitive function with the use of a large long-term study in US adults.

METHODS

Database and study participants

Data from the BLSA were used. The BLSA, initiated in 1958, is an ongoing prospective open-cohort study in community-dwelling, generally highly educated, upper to middle class adults aged 17–97 y at baseline (60.1% men) with a total enrollment of 3005 (37); exclusionary criteria are summarized elsewhere (38). Medical history was determined, and physical, neurological, and neuropsychological examinations were conducted in the BLSA's protocol, which has continued approval from the institutional review board of Medstar Research Institute.

In the present study, eligible participants (n = 2321) had at least one visit at or later than age 50 y and were at risk of dementia; 1917 of whom were non-Hispanic whites. Complete genetic, anthropometric, and other covariate data in eligible participants were available for 702 BLSA participants; data on cognitive function were available for n = 459 for the Trails A and B (megalin gene) and up to n = 616 for the BVRT (VDR gene).

Clinical evaluation of dementia

Annual follow-ups were conducted in all participants, and a consensus conference review was carried out if their Blessed Information Memory Concentration score (39) was ≥4, if their informant or subject Clinical Dementia Rating (40) score was ≥0.5, or if their Dementia Questionnaire (41) was abnormal. By using DSM-III-R (42) criteria, dementia diagnosis was determined and the age of onset was estimated on the basis of consecutive case conference findings. When participants had either single domain cognitive impairment (usually memory) or cognitive impairment in multiple domains without any significant functional loss in activities of daily living, a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment was made following the Petersen algorithm (43). In our present analysis, mild cognitive impairment cases were retained. However, 2 sets of analyses were conducted taking into account year of onset of dementia.

Cognitive assessment

A battery of 6 selected cognitive tests was used: the MMSE (44); BVRT (45); CVLT, List A (summation score across 5 learning trials) and delayed free recall score (DR) (46); verbal fluency tests, both letter (VFT-L) (47–49) and category (VFT-C) (50); Trails A and B (51); and DS-F and DS-B (52) (see Supplemental Material 1 under “Supplemental data” in the online issue). Linear mixed models with a quadratic age term (to allow for nonlinear age effects) were applied to predict cognitive score values at specific ages, particularly the mean individual age at follow-up, taking all time points until the end of follow-up (prediction I) or time points before the onset of dementia (prediction II), and to predict the slope for annual cognitive change at that particular age. The latter, which is termed LARCC was the main outcome of interest. It can be interpreted as the annual rate of change in the cognitive score between age 50 y and the mean age of follow-up per individual and cognitive test. After this estimation, LARCCs for each cognitive test score were entered into a factor analysis model as measured variables (53) in which a number of common factors were extracted on the basis of common variance, factor loadings estimated, and the residual variance labeled as uniqueness for each LARCC. The common factor model can be summarized as follows:

|

where LARCCi is the standardized z score for each cognitive test LARCC, λij is the factor loading for each LARCC and each factor, domainj is the standardized z score for each factor j, and φi is the residual error, the squared value of which is the uniqueness. The sum of squared factor loadings for each LARCCi is the communality or the common variance that is accounted for by the extracted factors. An eigenvalue >1 rule was used and the scree plot was observed to determine the adequate number of extracted factors that would produce the best model fit. The factor loadings were then rotated by using varimax orthogonal rotation, and the factors were interpreted and cognitive domains labeled accordingly, with a cutoff of ≥0.40 for significant loading. The factor scores (z scores) were predicted and used as markers of LARCC for specific cognitive domains. Domains were labeled on the basis of the combination of significantly high factor loadings and the corresponding measured variables or LARCCi as follows: domain 1, “Memory and executive function: earlier decline”; domain 2, “Verbal fluency and attention: later decline.” With the exception of Trails B, all LARCCi factor loadings were significant for only 1 of the 2 domains, creating a relatively simple structure that was easy to label and interpret. The labels were determined on the basis of the nature of the cognitive test and the timing that decline in those domains is usually observed during the life course (earlier compared with later). (See Supplemental Material 2 under “Supplemental data” in the online issue for results of the factor analysis.)

VDR and megalin SNPs, SNP LCs, and SNPHAPs

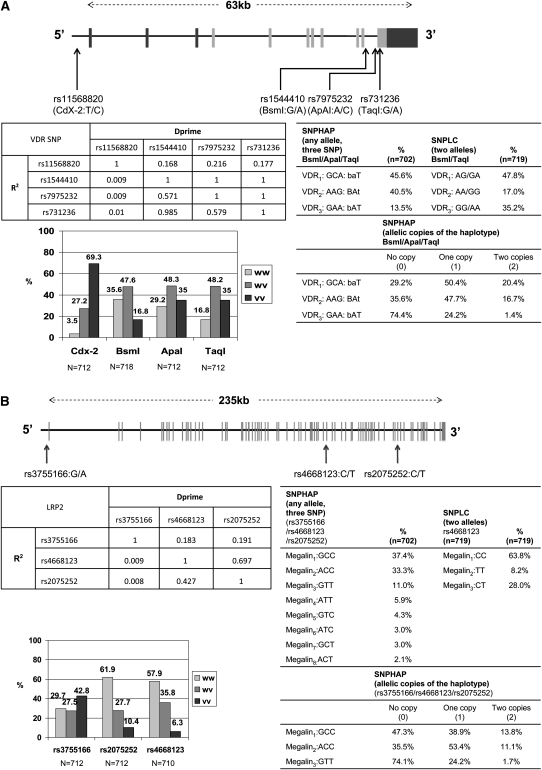

Blood samples were collected for DNA extraction, and genomewide genotyping was completed for 1231 subjects by using Illumina 550K. EIGENSTRAT (http://genepath.med.harvard.edu/∼reich/Software.htm) analysis using ∼10,000 randomly selected SNPs from the 550K SNP panel was used to select the subjects of European descent using HapMap CEU (http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) [Utah residents with northern and western European ancestry from the CEPH (Council on Education for Public Health) collection] as the reference population (54). In addition, part of our main analyses was adjusted for the top 2 principal components to control for any residual effects of population structure (54). Moreover, the HapMap CEU sample (build 36) was used as a reference to impute ∼2.5 million SNPs using MACH (http://www.sph.umich.edu/csg/abecasis/MACH/tour/imputation.html) (55). Imputed SNPs with an imputation quality r2 < 0.3 or minor allele frequency of <1% were excluded from the analysis. The selection of SNPs of interest was solely based on those selected in previous confirmatory studies, many of which were identified by genomewide association studies, relating cognitive function, decline, or dementia to VDR (18, 19) and megalin (20, 36) gene polymorphisms. Most of those selected SNPs were available in our database, with few exceptions (eg, VDR SNP rs10735810, FokI: G/A). Note that some VDR SNPs were also studied in relation to other phenotypes, including body composition in old age, obesity, bone mineral density, the metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and coronary artery disease (56–62). Consequently, 4 VDR SNPs [rs11568820 (CdX-2:T/C), rs1544410 (BsmI:G/A), rs7975232 (ApaI:A/C), and rs731236 (TaqI:G/A)] and 3 megalin SNPs (rs3755166: G/A; rs2075252: C/T; rs4668123: C/T) were chosen as long as they had reliable values. Those SNPs and their locations on each gene and their distributions are shown in .

VDR and megalin SNP LCs were obtained by using LC analysis (PROC LCA in SAS version 9.1; SAS Institute) (63, 64), in which sex and first-visit age were introduced as potential covariates and each selected SNP per gene was entered into that model (one gene per model) as a 3-level categorical variable. Model fit was determined on the basis of Akaike Information Criterion and Bayesian Information Criterion, which led to deciding the appropriate number of LCs. Posterior probabilities were estimated by using the Bayes theorem, and those were the same for all individuals with a specific SNP pattern per gene. On the basis of those posterior probabilities, each individual was labeled as belonging to a specific LC when the posterior probability for this class was >0.50, and the higher this probability the more the certainty of belonging to this class. In most cases, it is expected that this posterior probability is >0.90 (63). These SNPLCs, in terms of SNP combinations, are shown in more detail in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

A: Gene structure of the VDR gene. The SNP and gene coordinates are based on NCBI build 36 (hg18, March 2006) using RefSeq gene prediction. The VDR gene on chromosome 12 is composed of ≤11 exons spanning ∼63 kb. Note: More than 99% of eligible participants had well-defined SNPLCs that could be summarized by BsmI and TaqI SNP combinations. SNPHAPs were defined on the basis of 3 VDR SNP combinations (BsmI, ApaI, and TaqI) and were expressed as dosage (0 = none, 1 = one copy, 2 = 2 copies) in the main analysis. B: Gene structure of the megalin gene. The SNP and gene coordinates are based on NCBI build 36 (hg18, March 2006) using RefSeq gene prediction. The megalin (LRP2) gene on chromosome 2 has 79 exons and is ∼235 kb in size. Note: More than 96% of eligible participants had well-defined SNPLCs that could be summarized by the genotype of rs4668123. SNPHAPs were defined on the basis of all 3 megalin SNP combinations (rs3755166, rs4668123, and rs2075252) and were expressed as dosage (0 = none, 1 = one copy, 2 = 2 copies) in the main analysis. hg, human genome; LRP2, LDL receptor-related protein 2; NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information; RefSeq, reference sequence; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; SNPLC, single nucleotide polymorphism latent class; SNPHAP, single nucleotide polymorphism haplotype; VDR, vitamin D receptor gene; vv, variant-variant; wv, wild-type–variant; ww, wild-type–wild-type.

SNPHAPs were also considered as main predictors in our analysis for each of the 2 genes. For the VDR gene, the BsmI:G/A, ApaI:G/A, and TaqI:G/A SNPs were combined in that order to form SNPHAP, and their proportions in the population were found to be similar to those found in at least one previous study (18). As a result, 3 SNPHAPs were found in this population with one of the following SNP combinations for 1 or 2 alleles: VDR1, GCA (baT); VDR2, AAG (BAt); or VDR3, GAA (bAT). Participants were coded as 0 = having no VDRx haplotype, 1 = having one allele carrying the VDRx haplotype, 2 = having 2 alleles carrying the VDRx haplotype. This approach was also applied to the 3 megalin SNPs, and 8 haplotypes were found. However, only 3 of them were considered in the main analysis because their proportion in the population (with 1 or 2 copies) was >10% (see Figure 1 for more details).

Covariates

Three sets of covariates were considered as potential confounders in the main associations of interest: 1) sociodemographic factors, namely individual age at first visit and mean ages at follow-up (per individual and cognitive test), sex, educational attainment (years of schooling), and one lifestyle-related factor, namely smoking status (never, former or current smoker); 2) self-reported history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease (stroke, congestive heart failure, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or atrial fibrillation), and dyslipidemia at first visit; and 3) measured first-visit BMI (in kg/m2). Moreover, first-visit blood pressure (systolic and diastolic in mm Hg), plasma total and HDL cholesterol, and fasting blood glucose (in mg/dL) were analyzed only in relation to availability of genetic data for descriptive purposes, given their higher proportion with missing data compared with the self-reported conditions.

Statistical analysis

For each gene SNP that was included in our analyses, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was examined by using an exact test, and pairwise LD was calculated by using the Haploview version 4.2 package (65, 66). The LD map for all available SNPs of VDR and megalin genes are presented in Supplemental Material 3 under “Supplemental data” in the online issue. To describe the study participant characteristics and to compare them by genetic data availability, 1-factor ANOVA, t test, and chi-square test were used.

Furthermore, multiple OLS linear regression analysis was carried out to examine the association of VDR and megalin SNPs, SNPLCs, and SNPHAPs with predicted LARCCs for each cognitive test or domain and from each predictive model, after potential confounding variables including first-visit age, mean age of follow-up, sex, education, first-visit smoking status, self-reported comorbid conditions, and BMI were controlled for. SNPs (wild-type with variant v) were examined both in terms of genotype, comparing the 2 variant genotypes (wv, wild type-variant; vv, variant-variant) with the wild-type genotype (ww), and in terms of dosage of the variant allele (v). In the latter case, a P value for trend was computed. P values for trend were also computed when testing the association between each haplotype dosage (0, 1, and 2 copies) and the cognitive outcomes of interest.

To account for potential selection bias in OLS models (due to the nonrandom selection of participants with genetic data from the target study population), a 2-stage Heckman selection model was constructed (67) by using a probit model to obtain an inverse mills ratio at the first stage (derived from the predicted probability of being selected, conditional on the covariates in the probit model), as was done in an earlier study (24). The inverse mills ratio was then included into the main OLS models at a second stage to adjust for this selection bias. Stratification was made, and effect modification was tested (by adding interaction terms) by sex for the analysis when SNPs, SNPLCs, and SNPHAPs were the main predictors, particularly when the megalin SNP was included in the analysis. In fact, sex differences in the association between the megalin gene polymorphism and cognitive outcomes were hypothesized a priori, as discussed later (68–70).

A type I error of 0.05 was considered for all analyses, and P values between 0.05 and 0.10 were considered to be borderline significant for main effects, whereas a P < 0.10 was considered significant for interaction terms (71), before correction for multiple testing. Correction for multiple testing was performed by using a family-wise Bonferroni procedure whereby a family was defined by a cognitive test or a cognitive domain, with the assumption that the family was independent in content though not necessarily in its degree of correlation (72). Within each cognitive test, there were generally 2 test scores and 2 predictions to take into account for correction. This was the case for the CVLT-DR and CVLT-List A, Trails A and B, DS-F and DS-B, and VFT-C and VFT-L. For these cognitive tests, the significance criterion for P and P-trend was reduced to P = 0.05/4 = 0.0125 (marginal significance: P = 0.10/4 = 0.025). In the case of the MMSE (a measure of global cognition), BVRT, and cognitive domains (domains 1 and 2, produced by factor analysis of LARCCs with orthogonal rotation), only prediction was taken into account. In fact, they were deemed to be independent in content of other tests and of each other, while having only one score each, and thus the significance criterion was reduced to only P = 0.05/2 = 0.025 (marginal significance to P = 0.10/2 = 0.05). After correction for multiple testing, and due to their lower statistical power compared with main effects (71), interaction terms had their critical P values reduced to 0.05. All analyses (except for LCA) were performed by using Stata version 11.0 (73).

RESULTS

Study sample characteristics

Study sample characteristics are presented in Table 1, and the eligible group with genetic data available was compared with those without available genetic data. Generally, participants with complete genetic data were younger (mean age: 52.3 compared with 60.8 y), had higher proportion of women (47.8% compared with 26.9%), had higher educational attainment (mean education: 16.8 compared with 16.6 y), were less likely to be current smokers (18.5% compared with 25.3%), and were healthier in terms of continuous BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, fasting glucose concentration, and some comorbid conditions (type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease) (P < 0.05 on the basis of t test or chi-square test). By the end of follow-up, 50 participants developed dementia in the group with available genetic data (7.1%) as compared with 17.4% (n = 212) in the group with unavailable genetic data. Moreover, LARCCs were indicative of larger cognitive declines among participants with no genetic data available compared with those with genetic data for most cognitive tests (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Study sample characteristics by availability of gene SNP data: BLSA1

| Eligible study sample with visit at age ≥50 y |

Genetic data available |

Genetic data not available |

||||||||

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | P value2 | |

| Female (%) | 1917 | 32.7 | 702 | 47.85 | 1215 | 26.91 | <0.001 | |||

| Age at first visit (%) | 1901 | 57.7 | 16.37 | 702 | 52.34 | 16.7 | 1199 | 60.81 | 15.34 | <0.001 |

| ≤20 y | 1 | 0.05 | 1 | 0.14 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 21–29 y | 93 | 4.89 | 62 | 8.83 | 31 | 2.59 | ||||

| 30–39 y | 239 | 12.57 | 130 | 18.52 | 109 | 9.09 | ||||

| 40–49 y | 336 | 17.67 | 160 | 22.79 | 176 | 14.68 | ||||

| 50–59 y | 334 | 17.62 | 113 | 16.10 | 222 | 18.52 | ||||

| 60–69 y | 350 | 18.41 | 94 | 13.39 | 256 | 21.35 | ||||

| 70–79 y | 378 | 19.88 | 92 | 13.11 | 286 | 23.85 | ||||

| ≥80 y | 169 | 8.89 | 50 | 7.12 | 119 | 9.92 | ||||

| Education at first visit (y) | 1854 | 16.65 | 2.90 | 674 | 16.85 | 2.53 | 1180 | 16.55 | 3.09 | 0.0333 |

| Smoking status at first visit (%) | 1823 | 644 | 1179 | 0.004 | ||||||

| Never | 689 | 37.79 | 254 | 39.44 | 435 | 36.9 | ||||

| Former | 717 | 39.33 | 271 | 42.08 | 446 | 37.83 | ||||

| Current | 417 | 22.87 | 119 | 18.48 | 298 | 25.28 | ||||

| Type 2 diabetes at first visit (%) | 1901 | 2.89 | 702 | 1.28 | 1199 | 3.84 | 0.001 | |||

| Hypertension at first visit (%) | 1882 | 37.25 | 689 | 27.00 | 1193 | 43.17 | <0.001 | |||

| Cardiovascular disease at first visit (%)3 | 1917 | 7.25 | 702 | 3.85 | 1215 | 9.22 | <0.001 | |||

| Dyslipidemia at first visit (%) | 1901 | 5.84 | 702 | 6.70 | 1199 | 5.34 | 0.223 | |||

| BMI at first visit (kg/m2) | 1892 | 24.95 | 3.40 | 698 | 24.75 | 3.42 | 1194 | 25.07 | 3.39 | 0.0453 |

| Underweight [BMI (in kg/m2) ≤18.5] (%) | 25 | 1.32 | 10 | 1.43 | 15 | 1.26 | 0.192 | |||

| Normal weight (18.5 < BMI ≤ 24.9) (%) | 1015 | 53.65 | 396 | 56.73 | 619 | 51.84 | ||||

| Overweight (25.0 < BMI ≤ 29.9) (%) | 718 | 37.95 | 244 | 34.96 | 474 | 39.7 | ||||

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30) (%) | 134 | 7.08 | 48 | 6.88 | 86 | 7.2 | ||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 1881 | 130.57 | 20.72 | 689 | 124.74 | 17.97 | 1192 | 133.94 | 21.45 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 1880 | 79.91 | 10.98 | 689 | 78.36 | 10.16 | 1191 | 80.8 | 11.34 | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol concentration (mg/dL) | 1443 | 221.67 | 41.54 | 616 | 213.59 | 39.14 | 827 | 227.68 | 42.28 | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 581 | 49.46 | 13.03 | 323 | 49.68 | 12.65 | 258 | 49.18 | 13.52 | 0.6465 |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mg/dL) | 951 | 98.34 | 12.75 | 459 | 96.84 | 12.62 | 492 | 99.74 | 12.73 | 0.0004 |

| Dementia (%) | 1916 | 13.67 | 701 | 7.13 | 1215 | 17.45 | <0.001 | |||

| Predicted annual rate of cognitive change between age 5 y and mean age at follow-up4 | ||||||||||

| MMSE | ||||||||||

| All time points: prediction I | 944 | 0.017 | 0.117 | 500 | 0.039 | 0.095 | 444 | −0.008 | 0.134 | <0.001 |

| Time points before dementia onset: prediction II | 888 | −0.007 | 0.055 | 492 | 0.001 | 0.052 | 396 | −0.017 | 0.058 | <0.001 |

| BVRT | ||||||||||

| All time points: prediction I | 1394 | 0.126 | 0.076 | 630 | 0.109 | 0.077 | 764 | 0.140 | 0.073 | <0.001 |

| Time points before dementia onset: prediction II | 1319 | 0.121 | 0.065 | 622 | 0.107 | 0.066 | 697 | 0.135 | 0.061 | <0.001 |

| CVLT-List A | ||||||||||

| All time points: prediction I | 920 | −0.306 | 0.242 | 620 | −0.274 | 0.239 | 300 | −0.371 | 0.236 | <0.001 |

| Time points before dementia onset: prediction II | 870 | −0.271 | 0.192 | 601 | −0.251 | 0.196 | 269 | −0.315 | 0.175 | <0.001 |

| CVLT-DR | ||||||||||

| All time points: prediction I | 920 | −0.087 | 0.061 | 620 | −0.080 | 0.059 | 300 | −0.103 | 0.062 | <0.001 |

| Time points before dementia onset: prediction II | 870 | −0.075 | 0.048 | 601 | −0.071 | 0.048 | 269 | −0.085 | 0.048 | <0.001 |

| VFT-C | ||||||||||

| All time points: prediction I | 1025 | −0.040 | 0.137 | 519 | −0.011 | 0.132 | 506 | −0.071 | 0.135 | <0.001 |

| Time points before dementia onset: prediction II | 961 | −0.055 | 0.089 | 511 | −0.040 | 0.091 | 450 | −0.071 | 0.083 | <0.001 |

| VFT-L | ||||||||||

| All time points: prediction I | 1023 | −0.002 | 0.115 | 519 | 0.020 | 0.116 | 504 | −0.024 | 0.110 | <0.001 |

| Time points before dementia onset: prediction II | 939 | −0.008 | 0.079 | 508 | 0.001 | 0.084 | 431 | −0.020 | 0.072 | <0.001 |

| Trails A | ||||||||||

| All time points: prediction I | 960 | 0.391 | 1.114 | 484 | 0.080 | 0.927 | 476 | 0.708 | 1.198 | <0.001 |

| Time points before dementia onset: prediction II | 882 | 0.309 | 0.641 | 473 | 0.132 | 0.558 | 409 | 0.513 | 0.670 | <0.001 |

| Trails B | ||||||||||

| All time points: prediction I | 955 | 0.466 | 1.990 | 484 | −0.134 | 1.693 | 471 | 1.083 | 2.082 | <0.001 |

| Time points before dementia onset: prediction II | 879 | 0.446 | 1.668 | 472 | 0.014 | 1.455 | 407 | 0.947 | 1.759 | <0.001 |

| DS-F | ||||||||||

| All time points: prediction I | 959 | −0.031 | 0.010 | 623 | −0.030 | 0.011 | 338 | −0.032 | 0.009 | 0.009 |

| Time points before dementia onset: prediction II | 904 | −0.029 | 0.010 | 607 | −0.029 | 0.010 | 297 | −0.030 | 0.008 | 0.316 |

| DS-B | ||||||||||

| All time points: prediction I | 961 | −0.046 | 0.016 | 623 | −0.046 | 0.017 | 338 | −0.046 | 0.013 | 0.673 |

| Time points before dementia onset: prediction II | 906 | −0.045 | 0.016 | 607 | −0.045 | 0.017 | 299 | −0.044 | 0.013 | 0.101 |

| Cognitive domain 1 | ||||||||||

| All time points: prediction I | 707 | −0.16 | 0.97 | 475 | 0.00 | 0.94 | 232 | −0.50 | 0.94 | <0.001 |

| Time points before dementia onset: prediction II | 649 | −0.13 | 0.94 | 453 | 0.00 | 0.93 | 196 | −0.43 | 0.89 | <0.001 |

| Cognitive domain 2 | ||||||||||

| All time points: prediction I | 707 | −0.07 | 0.86 | 475 | 0.00 | 0.86 | 232 | −0.22 | 0.84 | 0.001 |

| Time points before dementia onset: prediction II | 649 | −0.05 | 0.83 | 649 | 0.00 | 0.84 | 196 | −0.16 | 0.80 | 0.025 |

BLSA, Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging; BVRT, Benton Visual Retention Test; CVLT-List A, California Verbal Learning Test, List A; CVLT-DR, California Verbal Learning Test, Delayed Recall; DS-B, Digits Span Backward; DS-F, Digits Span Forward; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; Trails A, Trailmaking Test, part A; Trails B, Trailmaking Test, part B; VFT-C, Verbal Fluency Test-Categorical; VFT-L, Verbal Fluency Test-Letter.

P value for null hypothesis of no difference between those with and those without genetic data.

Reported any of the following conditions at first visit: stroke, congestive heart failure, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or atrial fibrillation.

Cognitive scores were predicted at mean age at follow-up before onset of dementia or for all time points by using a linear mixed model with control for sex, race-ethnicity, education (y), and smoking status, with age added among the fixed-effects variables to allow for quadratic nonlinear change. The slope or annual rate of change was predicted from these models at the mean age at follow-up (ie, between age 50 and the individual mean age of follow-up for each cognitive test). By using factor analysis, 2-factor scores were estimated and were labeled as Longitudinal Annual Rate of Cognitive Change in the following domains: domain 1, “Memory and executive function: earlier decline”; domain 2, “Verbal fluency and attention: later decline” (see Supplemental Material 2 under “Supplemental data” in the online issue for more details).

All of the SNPs examined were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P > 0.05). Within the VDR gene, 3 SNPs (BsmI, ApaI, TaqI) were in LD (r2 > 0.5), whereas the CdX-2 SNP was independent. In the megalin gene, rs4668123 and rs2075252 were in moderate LD (r2 = 0.42), whereas rs3755166 was independent (Figure 1). Genotypic frequencies indicated that, for each SNP, one genotype had a relative frequency >40% and thus was dominant compared with the other genotypes. The percentage distributions of VDR and megalin SNP LC as determined by LCA and SNPHAP (1 or 2 copies) are presented in Figure 1. Note that the SNPHAP distribution is presented in non–mutually exclusive fashion because it reflects allelic combinations for each individual. When each SNPHAP was cross-tabulated with the SNP LC per gene, they were found to be significantly associated (P < 0.001 on the basis of chi-square test). In particular, participants with 2 copies of an SNPHAP belonged exclusively to a single SNP LC.

VDR SNPs and LARCCs

The association between VDR SNPs (entered alternatively, models A–D) and LARCCs (predictions I and II), with the use of multiple OLS models, is shown in Supplemental Material 4 under “Supplemental data” in the online issue. After correction for multiple testing, none of the associations (main effects in the total population) remained significant. When effect modification by sex was tested in the association between VDR SNP dosage and LARCC, sex differences (P < 0.05 for null hypothesis sex × SNP interaction term = 0) emerged in many of those associations, indicating in some cases that there were significant associations in women only (BsmI, ApaI, and TaqI in relation to VFT-C LARCC, both predictions; ApaI and TaqI in relation to DS-F LARCC, both predictions).

Megalin SNPs and LARCCs: sex-stratified findings

Similarly, in OLS models that included only the megalin gene SNP (Table 2), significant associations were found between the rs3755166: G/A megalin SNP and LARCC on MMSE, whereby an increasing dose of the “A” nucleotide was associated with faster decline (prediction I) in both sexes combined (β = −0.011, P = 0.033), an association deemed only marginally significant after correction of main effects for multiple testing (P < 0.05). An examination of prediction I of LARCC in verbal memory resulted in a significant association between the rs3755166: G/A megalin SNP and faster decline on tests scores in men (CVLT-List A: β = −0.038, P = 0.008; CVLT-DR: β = −0.011, P = 0.003) but a slower decline in women (CVLT-List A: β = +0.038, P = 0.016; CVLT-DR: β = +0.006, P = 0.082), with a significant interaction with sex (P < 0.05). Those associations remained significant only in men after correction for multiple testing (P < 0.0125). The finding of a sex interaction (P < 0.05) was replicated for most of those associations in prediction II. Similarly, decline in cognitive domain 1 was faster in men but not in women among those with a higher dose of the rs3755166:G/A megalin SNP (ie, the “A” nucleotide), with a significant interaction by sex for both predictions. In particular, for prediction I, men declined in this domain by −0.16 SD faster with each “A” nucleotide (P = 0.009), an association deemed significant even after correction for multiple testing (P < 0.025).

TABLE 2.

Megalin gene SNP associations with predicted annual rate of cognitive change between age 50 y and mean age of follow-up: multiple OLS regression analysis, BLSA1

| Predicted annual rate of cognitive change between age 50 y and mean age of follow-up2 |

||||||||

| All time points: prediction I |

Time points before dementia onset: prediction II |

|||||||

| n | β3 | SEE | P-trend | n | β3 | SEE | P-trend | |

| MMSE | ||||||||

| Megalin: rs3755166: G/A | 484 | −0.011 | 0.005 | 0.0334 | 477 | −0.004 | 0.003 | 0.126 |

| Men | 312 | −0.014 | 0.007 | 0.0384 | 306 | −0.007 | 0.004 | 0.076 |

| Women | 172 | −0.008 | 0.007 | 0.282 | 171 | −0.001 | 0.003 | 0.856 |

| Megalin: rs2075252: C/T | 484 | −0.008 | 0.007 | 0.279 | 477 | −0.005 | 0.004 | 0.208 |

| Men | 312 | −0.009 | 0.010 | 0.384 | 306 | −0.006 | 0.006 | 0.264 |

| Women | 172 | −0.009 | 0.011 | 0.407 | 171 | −0.004 | 0.005 | 0.373 |

| Megalin: rs4668123: C/T | 484 | +0.005 | 0.008 | 0.540 | 477 | +0.006 | 0.004 | 0.191 |

| Men | 312 | +0.016 | 0.011 | 0.170 | 306 | +0.011 | 0.006 | 0.088 |

| Women | 172 | −0.009 | 0.012 | 0.456 | 171 | −0.001 | 0.005 | 0.875 |

| BVRT | ||||||||

| Megalin: rs3755166: G/A | 608 | +0.002 | 0.003 | 0.600 | 601 | +0.000 | 0.003 | 0.898 |

| Men | 364 | +0.003 | 0.004 | 0.390 | 357 | +0.002 | 0.004 | 0.647 |

| Women | 244 | −0.002 | 0.005 | 0.608 | 244 | −0.003 | 0.004 | 0.524 |

| Megalin: rs2075252: C/T | 608 | +0.003 | 0.005 | 0.580 | 601 | +0.005 | 0.004 | 0.229 |

| Men | 364 | +0.001 | 0.006 | 0.838 | 357 | +0.005 | 0.005 | 0.327 |

| Women | 244 | +0.006 | 0.008 | 0.467 | 244 | +0.006 | 0.006 | 0.364 |

| Megalin: rs4668123: C/T | 608 | +0.000 | 0.005 | 0.929 | 601 | −0.001 | 0.005 | 0.803 |

| Men | 364 | +0.006 | 0.007 | 0.326 | 357 | +0.003 | 0.006 | 0.587 |

| Women | 244 | −0.010 | 0.009 | 0.256 | 244 | −0.010 | 0.007 | 0.190 |

| CVLT-List A | ||||||||

| Megalin: rs3755166: G/A | 598 | −0.006 | 0.011 | 0.5625 | 580 | −0.000 | 0.009 | 0.9595 |

| Men | 356 | −0.038 | 0.014 | 0.0086 | 343 | −0.025 | 0.012 | 0.045 |

| Women | 242 | +0.038 | 0.016 | 0.0164 | 237 | +0.033 | 0.013 | 0.0134 |

| Megalin: rs2075252: C/T | 598 | −0.030 | 0.016 | 0.069 | 580 | −0.028 | 0.014 | 0.047 |

| Men | 356 | −0.042 | 0.022 | 0.053 | 343 | −0.042 | 0.019 | 0.026 |

| Women | 242 | −0.028 | 0.024 | 0.245 | 237 | −0.021 | 0.020 | 0.307 |

| Megalin: rs4668123: C/T | 598 | +0.026 | 0.018 | 0.157 | 580 | +0.020 | 0.015 | 0.190 |

| Men | 356 | +0.016 | 0.024 | 0.511 | 343 | +0.010 | 0.020 | 0.633 |

| Women | 242 | +0.054 | 0.028 | 0.053 | 237 | +0.045 | 0.023 | 0.052 |

| CVLT-DR | ||||||||

| Megalin: rs3755166: G/A | 598 | −0.003 | 0.003 | 0.1745 | 580 | −0.002 | 0.002 | 0.2985 |

| Men | 356 | −0.011 | 0.003 | 0.0036 | 343 | −0.008 | 0.003 | 0.0096 |

| Women | 242 | +0.006 | 0.004 | 0.082 | 237 | +0.005 | 0.003 | 0.075 |

| Megalin: rs2075252: C/T | 598 | −0.008 | 0.004 | 0.051 | 580 | −0.007 | 0.003 | 0.038 |

| Men | 356 | −0.011 | 0.005 | 0.045 | 343 | −0.010 | 0.005 | 0.026 |

| Women | 242 | −0.006 | 0.006 | 0.321 | 237 | −0.004 | 0.005 | 0.417 |

| Megalin: rs4668123: C/T | 598 | +0.007 | 0.004 | 0.135 | 580 | +0.005 | 0.004 | 0.166 |

| Men | 356 | +0.004 | 0.006 | 0.537 | 343 | +0.002 | 0.005 | 0.634 |

| Women | 242 | +0.012 | 0.006 | 0.076 | 237 | 0.010 | 0.005 | 0.078 |

| VFT-C | ||||||||

| Megalin: rs3755166: G/A | 504 | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.6555 | 497 | +0.006 | 0.004 | 0.139 |

| Men | 319 | −0.008 | 0.008 | 0.310 | 313 | −0.000 | 0.005 | 0.953 |

| Women | 185 | +0.017 | 0.010 | 0.104 | 184 | +0.015 | 0.007 | 0.037 |

| Megalin: rs2075252: C/T | 504 | −0.011 | 0.009 | 0.228 | 497 | −0.004 | 0.006 | 0.513 |

| Men | 319 | −0.010 | 0.012 | 0.381 | 313 | −0.002 | 0.008 | 0.832 |

| Women | 185 | −0.018 | 0.015 | 0.228 | 184 | −0.010 | 0.010 | 0.335 |

| Megalin: rs4668123: C/T | 504 | +0.014 | 0.010 | 0.167 | 497 | +0.007 | 0.007 | 0.313 |

| Men | 319 | +0.019 | 0.013 | 0.155 | 313 | +0.007 | 0.008 | 0.384 |

| Women | 185 | +0.012 | 0.017 | 0.501 | 184 | +0.008 | 0.011 | 0.465 |

| VFT-L | ||||||||

| Megalin: rs3755166: G/A | 507 | −0.007 | 0.006 | 0.206 | 494 | −0.004 | 0.004 | 0.298 |

| Men | 319 | −0.010 | 0.007 | 0.176 | 311 | −0.006 | 0.005 | 0.212 |

| Women | 185 | −0.006 | 0.009 | 0.524 | 183 | −0.002 | 0.007 | 0.728 |

| Megalin: rs2075252: C/T | 507 | −0.015 | 0.008 | 0.072 | 494 | −0.010 | 0.006 | 0.099 |

| Men | 319 | −0.029 | 0.011 | 0.0086 | 311 | −0.021 | 0.008 | 0.0066 |

| Women | 185 | +0.007 | 0.013 | 0.602 | 183 | +0.008 | 0.010 | 0.374 |

| Megalin: rs4668123: C/T | 507 | +0.010 | 0.011 | 0.271 | 494 | +0.006 | 0.006 | 0.354 |

| Men | 319 | +0.028 | 0.012 | 0.0194 | 311 | +0.017 | 0.008 | 0.037 |

| Women | 185 | −0.020 | 0.015 | 0.180 | 183 | −0.014 | 0.011 | 0.211 |

| Trails A | ||||||||

| Megalin: rs3755166: G/A | 469 | −0.002 | 0.052 | 0.971 | 459 | +0.008 | 0.031 | 0.803 |

| Men | 302 | +0.049 | 0.076 | 0.523 | 294 | +0.041 | 0.042 | 0.330 |

| Women | 167 | −0.062 | 0.053 | 0.241 | 165 | −0.039 | 0.041 | 0.337 |

| Megalin: rs2075252: C/T | 469 | +0.018 | 0.080 | 0.816 | 459 | +0.028 | 0.047 | 0.548 |

| Men | 302 | +0.062 | 0.115 | 0.589 | 294 | +0.074 | 0.064 | 0.250 |

| Women | 167 | +0.006 | 0.082 | 0.942 | 165 | −0.008 | 0.063 | 0.902 |

| Megalin: rs4668123: C/T | 469 | +0.076 | 0.086 | 0.379 | 459 | +0.053 | 0.051 | 0.292 |

| Men | 302 | +0.058 | 0.125 | 0.641 | 294 | +0.061 | 0.069 | 0.377 |

| Women | 167 | +0.062 | 0.092 | 0.502 | 165 | +0.022 | 0.070 | 0.749 |

| Trails B | ||||||||

| Megalin: rs3755166: G/A | 469 | +0.082 | 0.086 | 0.337 | 458 | +0.072 | 0.075 | 0.337 |

| Men | 302 | +0.151 | 0.111 | 0.180 | 294 | +0.122 | 0.095 | 0.199 |

| Women | 167 | 0.000 | 0.134 | 0.998 | 164 | +0.022 | 0.124 | 0.858 |

| Megalin: rs2075252: C/T | 469 | +0.046 | 0.130 | 0.720 | 458 | +0.063 | 0.113 | 0.579 |

| Men | 302 | +0.102 | 0.169 | 0.548 | 294 | +0.145 | 0.144 | 0.315 |

| Women | 167 | 0.071 | 0.207 | 0.730 | 164 | +0.017 | 0.190 | 0.928 |

| Megalin: rs4668123: C/T | 469 | +0.010 | 0.142 | 0.946 | 458 | +0.001 | 0.123 | 0.990 |

| Men | 302 | +0.065 | 0.184 | 0.726 | 294 | +0.091 | 0.155 | 0.559 |

| Women | 167 | −0.096 | 0.231 | 0.677 | 164 | −0.135 | 0.212 | 0.526 |

| DS-F | ||||||||

| Megalin: rs3755166: G/A | 600 | +0.000 | 0.000 | 0.886 | 585 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.840 |

| Men | 360 | +0.001 | 0.000 | 0.214 | 348 | +0.001 | 0.000 | 0.153 |

| Women | 240 | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.104 | 237 | −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.080 |

| Megalin: rs2075252: C/T | 600 | +0.000 | 0.000 | 0.373 | 585 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.202 |

| Men | 360 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.152 | 348 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.126 |

| Women | 240 | −0.000 | 0.001 | 0.828 | 237 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.760 |

| Megalin: rs4668123: C/T | 600 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.515 | 585 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.860 |

| Men | 360 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.376 | 348 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.533 |

| Women | 240 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.968 | 237 | −0.000 | 0.001 | 0.654 |

| DS-B | ||||||||

| Megalin: rs3755166: G/A | 600 | −0.000 | 0.001 | 0.678 | 585 | −0.000 | 0.001 | 0.607 |

| Men | 359 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.727 | 347 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.771 |

| Women | 241 | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.150 | 238 | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.150 |

| Megalin: rs2075252: C/T | 600 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.645 | 585 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.443 |

| Men | 359 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.459 | 347 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.338 |

| Women | 241 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.912 | 238 | +0.001 | 0.002 | 0.704 |

| Megalin: rs4668123: C/T | 600 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.785 | 585 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.953 |

| Men | 359 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.376 | 347 | +0.001 | +0.001 | 0.487 |

| Women | 241 | −0.001 | 0.002 | 0.422 | 238 | −0.002 | 0.002 | 0.344 |

| Cognitive domain 1 | ||||||||

| Megalin: rs3755166: G/A | 460 | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0.2605 | 439 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.5595 |

| Men | 295 | −0.16 | 0.06 | 0.0096 | 280 | −0.12 | 0.06 | 0.048 |

| Women | 165 | +0.12 | 0.08 | 0.114 | 159 | +0.13 | 0.08 | 0.105 |

| Megalin: rs2075252: C/T | 460 | −0.08 | 0.07 | 0.270 | 439 | −0.10 | 0.07 | 0.1895 |

| Men | 295 | −0.11 | 0.09 | 0.251 | 280 | −0.16 | 0.09 | 0.090 |

| Women | 165 | −0.11 | 0.12 | 0.366 | 159 | −0.07 | 0.12 | 0.541 |

| Megalin: rs4668123: C/T | 460 | +0.04 | 0.08 | 0.596 | 439 | +0.03 | 0.08 | 0.6985 |

| Men | 295 | −0.04 | 0.10 | 0.670 | 280 | −0.07 | 0.10 | 0.486 |

| Women | 165 | +0.22 | 0.13 | 0.104 | 159 | +0.22 | 0.13 | 0.101 |

| Cognitive domain 2 | ||||||||

| Megalin: rs3755166: G/A | 460 | −0.00 | 0.03 | 0.965 | 439 | +0.00 | 0.03 | 0.922 |

| Men | 295 | −0.00 | 0.05 | 0.928 | 280 | +0.01 | 0.04 | 0.819 |

| Women | 165 | −0.03 | 0.06 | 0.608 | 159 | −0.03 | 0.06 | 0.597 |

| Megalin: rs2075252: C/T | 460 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.804 | 439 | −0.00 | 0.05 | 0.964 |

| Men | 295 | −0.00 | 0.07 | 0.998 | 280 | −0.00 | 0.07 | 0.945 |

| Women | 165 | −0.05 | 0.08 | 0.594 | 159 | +0.00 | 0.09 | 0.995 |

| Megalin: rs4668123: C/T | 460 | +0.04 | 0.06 | 0.473 | 439 | +0.04 | 0.06 | 0.513 |

| Men | 295 | +0.09 | 0.07 | 0.239 | 280 | +0.07 | 0.07 | 0.355 |

| Women | 165 | −0.02 | 0.10 | 0.838 | 159 | −0.02 | 0.10 | 0.841 |

Note that each SNP is denoted by an rs number followed by the polymorphism in which one nucleotide is replaced by another (eg, C/T or G/A). BLSA, Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging; BVRT, Benton Visual Retention Test; CVLT-List A, California Verbal Learning Test, List A; CVLT-DR, California Verbal Learning Test, Delayed Recall; DS-B, Digits Span Backward; DS-F, Digits Span Forward; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; OLS, ordinary least squares; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; Trails A, Trailmaking Test, part A; Trails B, Trailmaking Test, part B; VFT-C, Verbal Fluency Test-Categorical; VFT-L, Verbal Fluency Test-Letter.

Cognitive scores were predicted at the mean age at follow-up before onset of dementia or for all time points by using a linear mixed model controlled for sex, race-ethnicity, education (y), and smoking status, with age added among the fixed-effects variables to allow for quadratic nonlinear change. The slope or annual rate of change was predicted from these models at the mean age at follow-up (ie, between age 50 and the individual mean age of follow-up for each cognitive test). By using factor analysis, 2-factor scores were estimated and were labeled as Longitudinal Annual Rate of Cognitive Change in the following domains: domain 1, “Memory and executive function: earlier decline”; domain 2, “Verbal fluency and attention: later decline” (see Supplemental Material 2 under “Supplemental data” in the online issue for more details).

On the basis of multiple OLS regression models with outcome being cognitive annual rate of change and main exposures being the 3 megalin SNPs. The model controlled for first-visit age, mean age at follow-up, education, first-visit smoking status, first-visit self-reported type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and BMI.

Marginally significant main effects after family-wise Bonferroni correction: P < 0.05 for MMSE or BVRT or cognitive domains and P < 0.025 for other cognitive tests.

P < 0.05 for the null hypothesis that sex × SNP interaction term = 0 in a model in which the main effect of sex was added.

Significant main effects after family-wise Bonferroni correction: P < 0.025 for MMSE and cognitive domains and P < 0.0125 for other cognitive tests.

When examining the association between rs2075252: C/T and cognitive outcomes, faster decline among men only was found on VFT-L (prediction I: β = −0.029, P = 0.008; prediction II: β = −0.021, P = 0.006), without significant sex differences in this main association.

In contrast, slower decline in VFT-L, deemed marginally significant after correction for multiple testing, was found among men with increasing dosage of the “T” nucleotide for the third megalin SNP (rs4668123: C/T) for prediction I (β = +0.028, P = 0.019). In this case, sex differences were also nonsignificant.

VDR and Megalin SNP LC associations with LARCC: sex-stratified findings

As shown in Table 3, OLS regression models were conducted for SNP LCs as exposures and LARCCs as outcomes, stratifying by sex. After correction for multiple testing, Megalin2 (compared with Megalin1) was linked to a greater rate of decline with the CVLT-DR in men only (prediction II: β = −0.025, P = 0.011; P < 0.05 for sex × SNP LC interaction). A similar pattern was noted whereby the Megalin2 SNP LC (compared with Megalin1) was associated with a greater rate of decline with the CVLT-List A (prediction II: β = −0.108, P = 0.008) and cognitive domain 1 (prediction II: β = −0.529, P = 0.012) in men only, although without any significant sex differences (P > 0.05 for sex × SNP LC interaction). None of the other sex-specific associations retained their significance after correction for multiple testing.

TABLE 3.

VDR and Megalin SNP LC associations with predicted annual rate of cognitive change between age 50 y and mean age of follow-up: multiple OLS regression analysis, BLSA1

| Predicted annual rate of cognitive change between age 50 y and mean age of follow-up2 |

||||||||||||||||

| All time points: prediction I |

Time points before dementia onset: prediction II |

|||||||||||||||

| Men |

Women |

Men |

Women |

|||||||||||||

| n | β3 | SEE | P | n | β3 | SEE | P | n | β3 | SEE | P | n | β3 | SEE | P | |

| MMSE | 315 | 179 | 309 | 178 | ||||||||||||

| VDR2 vs VDR1 | +0.019 | 0.016 | 0.241 | +0.024 | 0.016 | 0.125 | +0.014 | 0.009 | 0.118 | +0.006 | 0.007 | 0.435 | ||||

| VDR3 vs VDR1 | +0.004 | 0.013 | 0.742 | −0.009 | 0.013 | 0.504 | +0.006 | 0.007 | 0.381 | −0.003 | 0.006 | 0.543 | ||||

| Megalin2 vs Megalin1 | −0.000 | 0.023 | 0.985 | −0.015 | 0.021 | 0.493 | −0.003 | 0.013 | 0.833 | −0.011 | 0.010 | 0.244 | ||||

| Megalin3 vs Megalin1 | +0.010 | 0.013 | 0.432 | −0.025 | 0.013 | 0.060 | +0.004 | 0.007 | 0.566 | −0.003 | 0.006 | 0.641 | ||||

| BVRT | 368 | 254 | 361 | 254 | ||||||||||||

| VDR2 vs VDR1 | −0.007 | 0.009 | 0.441 | +0.011 | 0.011 | 0.316 | −0.002 | 0.008 | 0.799 | +0.007 | 0.010 | 0.485 | ||||

| VDR3 vs VDR1 | −0.008 | 0.007 | 0.280 | +0.009 | 0.009 | 0.320 | −0.007 | 0.007 | 0.305 | +0.007 | 0.008 | 0.383 | ||||

| Megalin2 vs Megalin1 | +0.011 | 0.013 | 0.408 | −0.002 | 0.014 | 0.874 | +0.014 | 0.012 | 0.233 | +0.000 | 0.012 | 0.969 | ||||

| Megalin3 vs Megalin1 | +0.007 | 0.007 | 0.327 | +0.003 | 0.009 | 0.738 | +0.008 | 0.007 | 0.221 | −0.000 | 0.008 | 0.949 | ||||

| CVLT-List A | 360 | 252 | 347 | 247 | ||||||||||||

| VDR2 vs VDR1 | +0.049 | 0.034 | 0.148 | −0.029 | 0.036 | 0.421 | +0.039 | 0.029 | 0.176 | −0.017 | 0.031 | 0.586 | ||||

| VDR3 vs VDR1 | +0.035 | 0.027 | 0.199 | −0.017 | 0.029 | 0.567 | +0.026 | 0.023 | 0.258 | −0.004 | 0.025 | 0.880 | ||||

| Megalin2 vs Megalin1 | −0.102 | 0.048 | 0.034 | +0.003 | 0.046 | 0.954 | −0.108 | 0.040 | 0.0084 | −0.008 | 0.038 | 0.829 | ||||

| Megalin3 vs Megalin1 | +0.002 | 0.027 | 0.930 | +0.007 | 0.030 | 0.827 | −0.002 | 0.002 | 0.915 | +0.025 | 0.026 | 0.325 | ||||

| CVLT-DR | 360 | 252 | 347 | 247 | ||||||||||||

| VDR2 vs VDR1 | +0.010 | 0.008 | 0.218 | +0.000 | 0.008 | 0.992 | +0.007 | 0.007 | 0.348 | +0.004 | 0.007 | 0.581 | ||||

| VDR3 vs VDR1 | +0.015 | 0.007 | 0.0195 | −0.001 | 0.007 | 0.915 | +0.012 | 0.006 | 0.029 | +0.002 | 0.006 | 0.643 | ||||

| Megalin2 vs Megalin1 | −0.026 | 0.012 | 0.026 | +0.001 | 0.011 | 0.922 | −0.025 | 0.010 | 0.01146 | −0.002 | 0.009 | 0.853 | ||||

| Megalin3 vs Megalin1 | −0.002 | 0.006 | 0.709 | +0.009 | 0.007 | 0.184 | −0.003 | 0.006 | 0.5426 | +0.014 | 0.006 | 0.0235 | ||||

| VFT-C | 322 | 192 | 316 | 191 | ||||||||||||

| VDR2 vs VDR1 | +0.006 | 0.018 | 0.758 | +0.033 | 0.023 | 0.155 | +0.004 | 0.012 | 0.729 | +0.022 | 0.016 | 0.165 | ||||

| VDR3 vs VDR1 | +0.022 | 0.015 | 0.161 | −0.021 | 0.019 | 0.284 | +0.012 | 0.010 | 0.192 | −0.012 | 0.013 | 0.340 | ||||

| Megalin2 vs Megalin1 | −0.002 | 0.026 | 0.929 | +0.010 | 0.030 | 0.729 | −0.007 | 0.017 | 0.684 | +0.005 | 0.020 | 0.812 | ||||

| Megalin3 vs Megalin1 | +0.019 | 0.015 | 0.205 | −0.010 | 0.030 | 0.435 | +0.013 | 0.017 | 0.169 | +0.000 | 0.013 | 0.978 | ||||

| VFT-L | 322 | 192 | 314 | 190 | ||||||||||||

| VDR2 vs VDR1 | −0.015 | 0.017 | 0.383 | −0.006 | 0.021 | 0.757 | −0.011 | 0.012 | 0.358 | −0.005 | 0.015 | 0.720 | ||||

| VDR3 vs VDR1 | −0.005 | 0.014 | 0.712 | −0.004 | 0.017 | 0.799 | −0.005 | 0.009 | 0.582 | +0.000 | 0.012 | 0.952 | ||||

| Megalin2 vs Megalin1 | −0.001 | 0.024 | 0.978 | −0.006 | 0.027 | 0.829 | −0.009 | 0.017 | 0.590 | −0.008 | 0.019 | 0.668 | ||||

| Megalin3 vs Megalin1 | −0.007 | 0.014 | 0.607 | +0.006 | 0.018 | 0.806 | −0.007 | 0.010 | 0.461 | +0.021 | 0.012 | 0.085 | ||||

| Trails A | 304 | 172 | 296 | 170 | ||||||||||||

| VDR2 vs VDR1 | −0.342 | 0.174 | 0.050 | +0.036 | 0.121 | 0.768 | −0.174 | 0.100 | 0.076 | +0.025 | 0.093 | 0.786 | ||||

| VDR3 vs VDR1 | −0.221 | 0.138 | 0.112 | +0.039 | 0.100 | 0.701 | −0.093 | 0.077 | 0.228 | +0.040 | 0.075 | 0.598 | ||||

| Megalin2 vs Megalin1 | +0.122 | 0.249 | 0.623 | +0.078 | 0.162 | 0.633 | +0.169 | 0.141 | 0.233 | −0.006 | 0.122 | 0.963 | ||||

| Megalin3 vs Megalin1 | +0.107 | 0.141 | 0.450 | +0.040 | 0.102 | 0.693 | +0.093 | 0.078 | 0.234 | −0.038 | 0.077 | 0.622 | ||||

| Trails B | 304 | 172 | 296 | 169 | ||||||||||||

| VDR2 vs VDR1 | −0.504 | 0.258 | 0.052 | −0.101 | 0.309 | 0.744 | −0.485 | 0.218 | 0.027 | −0.177 | 0.286 | 0.537 | ||||

| VDR3 vs VDR1 | −0.230 | 0.205 | 0.264 | +0.023 | 0.255 | 0.929 | −0.249 | 0.173 | 0.151 | −0.007 | 0.228 | 0.974 | ||||

| Megalin2 vs Megalin1 | +0.209 | 0.369 | 0.572 | −0.185 | 0.414 | 0.655 | +0.417 | 0.317 | 0.189 | −0.203 | 0.369 | 0.584 | ||||

| Megalin3 vs Megalin1 | +0.072 | 0.209 | 0.935 | +0.272 | 0.260 | 0.297 | +0.135 | 0.175 | 0.441 | −0.042 | 0.236 | 0.857 | ||||

| DS-F | 364 | 250 | 352 | 247 | ||||||||||||

| VDR2 vs VDR1 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.8696 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.739 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.7696 | −0.000 | 0.001 | 0.920 | ||||

| VDR3 vs VDR1 | +0.002 | 0.001 | 0.1456 | −0.002 | 0.001 | 0.062 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.1036 | −0.002 | 0.001 | 0.043 | ||||

| Megalin2 vs Megalin1 | +0.003 | 0.001 | 0.041 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.518 | +0.003 | 0.001 | 0.041 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.676 | ||||

| Megalin3 vs Megalin1 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.115 | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.199 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.146 | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.190 | ||||

| DS-B | 363 | 251 | 351 | 248 | ||||||||||||

| VDR2 vs VDR1 | −0.001 | 0.002 | 0.735 | +0.001 | 0.002 | 0.499 | −0.000 | 0.002 | 0.829 | +0.001 | 0.002 | 0.774 | ||||

| VDR3 vs VDR1 | +0.000 | 0.002 | 0.907 | −0.003 | 0.002 | 0.085 | +0.000 | 0.002 | 0.923 | −0.003 | 0.002 | 0.064 | ||||

| Megalin2 vs Megalin1 | +0.004 | 0.002 | 0.137 | +0.002 | 0.003 | 0.481 | +0.005 | 0.002 | 0.096 | +0.002 | 0.003 | 0.508 | ||||

| Megalin3 vs Megalin1 | +0.001 | 0.002 | 0.639 | −0.003 | 0.002 | 0.079 | +0.001 | 0.002 | 0.667 | −0.003 | 0.002 | 0.092 | ||||

| Cognitive domain 1 | 297 | 170 | 282 | 164 | ||||||||||||

| VDR2 vs VDR1 | +0.194 | 0.144 | 0.178 | −0.077 | 0.178 | 0.666 | +0.167 | 0.144 | 0.249 | +0.056 | 0.184 | 0.759 | ||||

| VDR3 vs VDR1 | +0.177 | 0.113 | 0.119 | −0.101 | 0.145 | 0.485 | +0.186 | 0.114 | 0.107 | −0.022 | 0.146 | 0.879 | ||||

| Megalin2 vs Megalin1 | −0.366 | 0.212 | 0.084 | +0.099 | 0.147 | 0.937 | −0.529 | 0.210 | 0.0124 | +0.047 | 0.233 | 0.841 | ||||

| Megalin3 vs Megalin1 | −0.008 | 0.115 | 0.947 | +0.11 | 0.147 | 0.937 | −0.07 | 0.116 | 0.558 | +0.246 | 0.153 | 0.109 | ||||

| Cognitive domain 2 | 297 | 170 | 282 | 164 | ||||||||||||

| VDR2 vs VDR1 | +0.072 | 0.107 | 0.501 | +0.153 | 0.128 | 0.235 | +0.090 | 0.105 | 0.390 | +0.094 | 0.133 | 0.481 | ||||

| VDR3 vs VDR1 | +0.066 | 0.084 | 0.433 | −0.038 | 0.105 | 0.718 | +0.073 | 0.083 | 0.380 | −0.051 | 0.106 | 0.630 | ||||

| Megalin2 vs Megalin1 | +0.172 | 0.157 | 0.274 | +0.049 | 0.169 | 0.774 | +0.143 | 0.152 | 0.348 | +0.052 | 0.168 | 0.757 | ||||

| Megalin3 vs Megalin1 | +0.040 | 0.086 | 0.641 | −0.102 | 0.106 | 0.338 | +0.024 | 0.084 | 0.773 | −0.007 | 0.110 | 0.946 | ||||

Note that VDR1, VDR2, and VDR3 denote VDR SNP LCs, whereas Megalin1, Megalin2, and Megalin3 denote Megalin SNP LCs. BLSA, Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging; BVRT, Benton Visual Retention Test; CVLT-List A, California Verbal Learning Test, List A; CVLT-DR, California Verbal Learning Test, Delayed Recall; DS-B, Digits Span Backward; DS-F, Digits Span Forward; LC, latent class; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; OLS, ordinary least squares; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; Trails A, Trailmaking Test, part A; Trails B, Trailmaking Test, part B; VDR, vitamin D receptor gene; VFT-C, Verbal Fluency Test-Categorical; VFT-L, Verbal Fluency Test-Letter.

Cognitive scores were predicted at mean age at follow-up before onset of dementia or for all time points by using a linear mixed model controlled for sex, race-ethnicity, education (y), and smoking status, with age added among the fixed-effects variables to allow for quadratic nonlinear change. The slope or annual rate of change was predicted from these models at the mean age at follow-up (ie, between age 50 y and the individual mean age of follow-up for each cognitive test). By using factor analysis, 2-factor scores were estimated and were labeled as Longitudinal Annual Rate of Cognitive Change in the following domains: domain 1, “Memory and executive function: earlier decline”; domain 2, “Verbal fluency and attention: later decline” (see Supplemental Material 2 under “Supplemental data” in the online issue for more details).

On the basis of multiple OLS regression models with outcome being cognitive annual rate of change and main exposures being the 3 megalin and VDR SNP LCs. See Figure 1 for more details on definition of the LCs. The model controlled for first-visit age, mean age at follow-up, education, first-visit smoking status, first-visit self-reported type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and BMI.

Significant main effects after family-wise Bonferroni correction: P < 0.025 for MMSE and cognitive domains and P < 0.0125 for other cognitive tests.

Marginally significant main effects after family-wise Bonferroni correction: P < 0.05 for MMSE or BVRT or cognitive domains and P < 0.025 for other cognitive tests.

P < 0.05 for the null hypothesis that sex × SNP LC interaction term = 0 in a model in which the main effect of sex was added.

VDR and Megalin SNPHAP associations with LARCC: sex-stratified findings

VDR SNPHAPs, consisting of [rs1544410 (BsmI:G/A), rs7975232 (ApaI:A/C), and rs731236 (TaqI:G/A)] SNP combinations, and megalin SNPHAPs, consisting of [rs3755166:G/A; rs2075252:C/T; and rs4668123:C/T] combinations were examined in terms of haplotype dosage in relation to LARCCs for each sex and each prediction (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

VDR and Megalin SNPHAP associations with predicted annual rate of cognitive change between age 50 y and mean age of follow-up: multiple OLS regression analysis, BLSA1

| Predicted annual rate of cognitive change between age 50 y and mean age of follow-up2 |

|||||||||||||||||

| All time points: prediction I |

Time points before dementia onset: prediction II |

||||||||||||||||

| Men |

Women |

Men |

Women |

||||||||||||||

| n | β3 | SEE | P | n | β3 | SEE | P | n | β3 | SEE | P | n | β3 | SEE | P | ||

| MMSE: models A–F | |||||||||||||||||

| VDR1: GCA (0, 1, 2) | 312 | −0.009 | 0.008 | 0.260 | 172 | −0.010 | 0.009 | 0.246 | 306 | −0.006 | 0.004 | 0.184 | 171 | −0.001 | 0.004 | 0.846 | |

| VDR2:AAG (0, 1, 2) | 312 | +0.005 | 0.009 | 0.527 | 172 | +0.017 | 0.008 | 0.0424 | 306 | +0.002 | 0.004 | 0.649 | 171 | +0.005 | 0.004 | 0.173 | |

| VDR3: GAA (0, 1, 2) | 312 | +0.017 | 0.012 | 0.163 | 172 | −0.017 | 0.012 | 0.169 | 306 | +0.014 | 0.007 | 0.04745 | 171 | −0.010 | 0.006 | 0.078 | |

| Megalin1: GCC (0, 1, 2) | 312 | +0.010 | 0.008 | 0.207 | 172 | +0.012 | 0.008 | 0.161 | 306 | +0.004 | 0.004 | 0.419 | 171 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 1.000 | |

| Megalin2: ACC (0, 1, 2) | 312 | −0.017 | 0.009 | 0.056 | 172 | +0.004 | 0.010 | 0.684 | 306 | −0.006 | 0.005 | 0.197 | 171 | +0.007 | 0.004 | 0.107 | |

| Megalin3: GTT (0, 1, 2) | 312 | +0.011 | 0.013 | 0.408 | 172 | −0.008 | 0.012 | 0.513 | 306 | +0.008 | 0.007 | 0.255 | 171 | −0.001 | 0.005 | 0.817 | |

| BVRT: models A–F | |||||||||||||||||

| VDR1: GCA (0, 1, 2) | 364 | −0.004 | 0.005 | 0.356 | 243 | −0.001 | 0.006 | 0.837 | 357 | −0.005 | 0.004 | 0.273 | 243 | −0.001 | 0.005 | 0.810 | |

| VDR2:AAG (0, 1, 2) | 364 | +0.001 | 0.005 | 0.797 | 243 | −0.001 | 0.006 | 0.914 | 357 | +0.003 | 0.004 | 0.550 | 243 | −0.001 | 0.005 | 0.772 | |

| VDR3: GAA (0, 1, 2) | 364 | +0.003 | 0.007 | 0.660 | 243 | +0.004 | 0.009 | 0.652 | 357 | +0.001 | 0.006 | 0.863 | 243 | +0.006 | 0.007 | 0.422 | |

| Megalin1: GCC (0, 1, 2) | 364 | −0.006 | 0.005 | 0.219 | 243 | +0.001 | 0.006 | 0.919 | 357 | −0.005 | 0.004 | 0.227 | 243 | +0.002 | 0.005 | 0.691 | |

| Megalin2: ACC (0, 1, 2) | 364 | +0.001 | 0.005 | 0.899 | 243 | +0.003 | 0.006 | 0.676 | 357 | −0.001 | 0.005 | 0.896 | 243 | +0.000 | 0.005 | 0.972 | |

| Megalin3: GTT (0, 1, 2) | 364 | +0.006 | 0.007 | 0.418 | 243 | −0.005 | 0.008 | 0.561 | 357 | +0.007 | 0.007 | 0.312 | 243 | −0.004 | 0.007 | 0.544 | |

| CVLT-List A:models A–F | |||||||||||||||||

| VDR1: GCA (0, 1, 2) | 356 | −0.019 | 0.018 | 0.270 | 241 | −0.006 | 0.019 | 0.735 | 343 | −0.019 | 0.015 | 0.217 | 236 | −0.001 | 0.016 | 0.934 | |

| VDR2:AAG (0, 1, 2) | 356 | −0.004 | 0.017 | 0.797 | 241 | +0.004 | 0.018 | 0.819 | 343 | −0.003 | 0.015 | 0.859 | 236 | +0.003 | 0.016 | 0.838 | |

| VDR3: GAA (0, 1, 2) | 356 | +0.059 | 0.026 | 0.0254 | 241 | +0.008 | 0.028 | 0.779 | 343 | +0.052 | 0.022 | 0.0194 | 236 | −0.001 | 0.023 | 0.953 | |

| Megalin1: GCC (0, 1, 2) | 356 | +0.039 | 0.018 | 0.0285 | 241 | −0.043 | 0.019 | 0.0224 | 343 | +0.033 | 0.015 | 0.02745 | 236 | −0.043 | 0.016 | 0.0066 | |

| Megalin2: ACC (0, 1, 2) | 356 | −0.023 | 0.019 | 0.2075 | 241 | +0.037 | 0.020 | 0.072 | 343 | −0.011 | 0.016 | 0.468 | 236 | +0.036 | 0.017 | 0.039 | |

| Megalin3: GTT (0, 1, 2) | 356 | −0.018 | 0.027 | 0.519 | 241 | −0.018 | 0.027 | 0.511 | 343 | −0.021 | 0.023 | 0.366 | 236 | +0.023 | 0.022 | 0.292 | |

| CVLT-DR: models A–F | |||||||||||||||||

| VDR1: GCA (0, 1, 2) | 356 | −0.000 | 0.004 | 0.990 | 241 | −0.002 | 0.004 | 0.717 | 343 | −0.000 | 0.004 | 0.930 | 236 | −0.000 | 0.004 | 0.958 | |

| VDR2:AAG (0, 1, 2) | 356 | −0.005 | 0.004 | 0.216 | 241 | +0.002 | 0.004 | 0.619 | 343 | −0.005 | 0.004 | 0.193 | 236 | +0.002 | 0.004 | 0.533 | |

| VDR3: GAA (0, 1, 2) | 356 | +0.014 | 0.006 | 0.032 | 241 | −0.000 | 0.007 | 0.958 | 343 | +0.013 | 0.005 | 0.01845 | 236 | −0.004 | 0.005 | 0.500 | |

| Megalin1: GCC (0, 1, 2) | 356 | +0.011 | 0.004 | 0.00956 | 241 | −0.007 | 0.004 | 0.112 | 343 | +0.010 | 0.004 | 0.00756 | 236 | −0.007 | 0.004 | 0.052 | |

| Megalin2: ACC (0, 1, 2) | 356 | −0.007 | 0.005 | 0.132 | 241 | +0.005 | 0.005 | 0.322 | 343 | −0.005 | 0.004 | 0.207 | 236 | +0.004 | 0.004 | 0.276 | |

| Megalin3: GTT (0, 1, 2) | 356 | −0.003 | 0.07 | 0.657 | 241 | +0.009 | 0.006 | 0.145 | 343 | −0.004 | 0.006 | 0.478 | 236 | +0.007 | 0.005 | 0.192 | |

| VFT-C: models A–F | |||||||||||||||||

| VDR1: GCA (0, 1, 2) | 319 | +0.011 | 0.009 | 0.2585 | 184 | −0.031 | 0.012 | 0.0126 | 313 | +0.005 | 0.006 | 0.4195 | 183 | −0.019 | 0.009 | 0.0244 | |

| VDR2:AAG (0, 1, 2) | 319 | −0.012 | 0.009 | 0.2075 | 184 | +0.024 | 0.012 | 0.043 | 313 | −0.007 | 0.006 | 0.2495 | 183 | +0.015 | 0.008 | 0.067 | |

| VDR3: GAA (0, 1, 2) | 319 | +0.002 | 0.014 | 0.895 | 184 | +0.010 | 0.018 | 0.572 | 313 | +0.004 | 0.009 | 0.696 | 183 | +0.006 | 0.012 | 0.603 | |

| Megalin1: GCC (0, 1, 2) | 319 | −0.003 | 0.010 | 0.734 | 184 | −0.014 | 0.012 | 0.241 | 313 | −0.008 | 0.006 | 0.205 | 183 | −0.016 | 0.008 | 0.042 | |

| Megalin2: ACC (0, 1, 2) | 319 | −0.004 | 0.010 | 0.695 | 184 | +0.031 | 0.014 | 0.030 | 313 | +0.005 | 0.007 | 0.440 | 183 | +0.026 | 0.009 | 0.0056 | |

| Megalin3: GTT (0, 1, 2) | 319 | +0.009 | 0.015 | 0.542 | 184 | −0.001 | 0.017 | 0.945 | 313 | +0.006 | 0.010 | 0.525 | 183 | −0.001 | 0.011 | 0.926 | |

| VFT-L: models A–F | |||||||||||||||||

| VDR1: GCA (0, 1, 2) | 319 | +0.006 | 0.009 | 0.465 | 184 | −0.003 | 0.011 | 0.801 | 313 | +0.003 | 0.006 | 0.659 | 182 | −0.001 | 0.009 | 0.937 | |

| VDR2:AAG (0, 1, 2) | 319 | −0.003 | 0.009 | 0.698 | 184 | −0.001 | 0.011 | 0.872 | 311 | +0.005 | 0.009 | 0.562 | 182 | −0.004 | 0.008 | 0.567 | |

| VDR3: GAA (0, 1, 2) | 319 | −0.008 | 0.013 | 0.558 | 184 | +0.010 | 0.016 | 0.542 | 311 | −0.003 | 0.009 | 0.743 | 182 | +0.011 | 0.011 | 0.333 | |

| Megalin1: GCC (0, 1, 2) | 319 | +0.010 | 0.009 | 0.944 | 184 | +0.005 | 0.011 | 0.672 | 311 | +0.001 | 0.006 | 0.856 | 182 | −0.002 | 0.008 | 0.720 | |

| Megalin2: ACC (0, 1, 2) | 319 | −0.003 | 0.010 | 0.742 | 184 | +0.003 | 0.012 | 0.834 | 311 | +0.000 | 0.007 | 0.996 | 182 | +0.007 | 0.009 | 0.461 | |

| Megalin3: GTT (0, 1, 2) | 319 | +0.000 | 0.014 | 0.978 | 184 | −0.002 | 0.015 | 0.870 | 311 | −0.000 | 0.009 | 0.987 | 182 | +0.007 | 0.011 | 0.533 | |

| Trails A: models A–F | |||||||||||||||||

| VDR1: GCA (0, 1, 2) | 302 | +0.000 | 0.091 | 0.997 | 167 | +0.019 | 0.064 | 0.766 | 294 | +0.066 | 0.051 | 0.198 | 165 | +0.031 | 0.049 | 0.525 | |

| VDR2:AAG (0, 1, 2) | 302 | −0.018 | 0.090 | 0.845 | 167 | +0.001 | 0.061 | 0.991 | 294 | −0.022 | 0.051 | 0.659 | 165 | −0.001 | 0.047 | 0.973 | |

| VDR3: GAA (0, 1, 2) | 302 | +0.034 | 0.135 | 0.797 | 167 | −0.043 | 0.09 | 0.648 | 294 | −0.100 | 0.076 | 0.189 | 165 | −0.063 | 0.072 | 0.379 | |

| Megalin1: GCC (0, 1, 2) | 302 | −0.096 | 0.091 | 0.294 | 167 | −0.037 | 0.062 | 0.558 | 294 | −0.104 | 0.051 | 0.041 | 165 | −0.006 | 0.048 | 0.898 | |

| Megalin2: ACC (0, 1, 2) | 302 | +0.031 | 0.099 | 0.750 | 167 | −0.046 | 0.071 | 0.518 | 294 | +0.008 | 0.055 | 0.883 | 165 | −0.027 | 0.054 | 0.622 | |

| Megalin3: GTT (0, 1, 2) | 302 | +0.187 | 0.141 | 0.183 | 167 | +0.083 | 0.086 | 0.336 | 294 | +0.130 | 0.078 | 0.097 | 165 | +0.004 | 0.067 | 0.853 | |

| Trails B: models A–F | |||||||||||||||||

| VDR1: GCA (0, 1, 2) | 302 | +0.136 | 0.134 | 0.310 | 167 | +0.016 | 0.016 | 0.920 | 294 | +0.154 | 0.114 | 0.177 | 164 | +0.015 | 0.149 | 0.919 | |

| VDR2:AAG (0, 1, 2) | 302 | −0.067 | 0.133 | 0.618 | 167 | −0.047 | 0.153 | 0.757 | 294 | −0.054 | 0.114 | 0.635 | 164 | −0.053 | 0.144 | 0.713 | |

| VDR3: GAA (0, 1, 2) | 302 | −0.144 | 0.200 | 0.470 | 167 | −0.136 | 0.191 | 0.474 | 294 | −0.211 | 0.169 | 0.214 | 164 | +0.088 | 0.216 | 0.686 | |

| Megalin1: GCC (0, 1, 2) | 302 | −0.172 | 0.135 | 0.203 | 167 | −0.172 | 0.129 | 0.181 | 294 | −0.158 | 0.114 | 0.169 | 164 | +0.055 | 0.144 | 0.704 | |

| Megalin2: ACC (0, 1, 2) | 302 | +0.071 | 0.146 | 0.625 | 167 | −0.027 | 0.178 | 0.878 | 294 | +0.005 | 0.124 | 0.967 | 164 | +0.023 | 0.165 | 0.889 | |

| Megalin3: GTT (0, 1, 2) | 302 | +0.091 | 0.208 | 0.664 | 167 | −0.014 | 0.217 | 0.946 | 294 | +0.168 | 0.175 | 0.338 | 164 | +0.109 | 0.201 | 0.588 | |

| DS-F: models A–F | |||||||||||||||||

| VDR1: GCA (0, 1, 2) | 360 | +0.001 | 0.000 | 0.2595 | 240 | −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.045 | 348 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.2835 | 237 | −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.064 | |

| VDR2:AAG (0, 1, 2) | 360 | −0.000 | 0.000 | 0.2675 | 240 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.099 | 348 | −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.231 | 237 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.156 | |

| VDR3: GAA (0, 1, 2) | 360 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.838 | 240 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.848 | 348 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.685 | 237 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.769 | |

| Megalin1: GCC (0, 1, 2) | 360 | −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.0144 | 240 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.711 | 348 | −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.0204 | 237 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.766 | |

| Megalin2: ACC (0, 1, 2) | 360 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.634 | 240 | −0.000 | 0.001 | 0.413 | 348 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.582 | 237 | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.416 | |

| Megalin3: GTT (0, 1, 2) | 360 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.065 | 240 | −0.000 | 0.001 | 0.583 | 348 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.094 | 237 | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.525 | |

| DS-B: models A–F | |||||||||||||||||

| VDR1: GCA (0, 1, 2) | 359 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.4645 | 241 | −0.002 | 0.001 | 0.035 | 347 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.532 | 238 | −0.002 | 0.001 | 0.468 | |

| VDR2:AAG (0, 1, 2) | 359 | −0.000 | 0.001 | 0.640 | 241 | +0.002 | 0.001 | 0.054 | 347 | −0.000 | 0.001 | 0.687 | 238 | +0.002 | 0.001 | 0.091 | |

| VDR3: GAA (0, 1, 2) | 359 | −0.000 | 0.002 | 0.837 | 241 | −0.000 | 0.002 | 0.959 | 347 | −0.000 | 0.002 | 0.878 | 238 | +0.000 | 0.002 | 0.969 | |

| Megalin1: GCC (0, 1, 2) | 359 | −0.020 | 0.001 | 0.064 | 241 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.278 | 347 | −0.002 | 0.001 | 0.085 | 238 | +0.001 | 0.001 | 0.336 | |

| Megalin2: ACC (0, 1, 2) | 359 | +0.000 | 0.001 | 0.919 | 241 | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.538 | 347 | −0.000 | 0.001 | 0.980 | 238 | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.516 | |

| Megalin3: GTT (0, 1, 2) | 359 | +0.002 | 0.002 | 0.221 | 241 | −0.001 | 0.002 | 0.436 | 347 | +0.002 | 0.002 | 0.215 | 238 | −0.001 | 0.002 | 0.507 | |

| Cognitive domain 1: models A–F | |||||||||||||||||

| VDR1: GCA (0, 1, 2) | 295 | −0.02 | 0.07 | 0.742 | 165 | −0.07 | 0.09 | 0.461 | 280 | −0.05 | 0.08 | 0.504 | 159 | −0.04 | 0.10 | 0.693 | |

| VDR2:AAG (0, 1, 2) | 295 | −0.03 | 0.07 | 0.603 | 165 | +0.03 | 0.09 | 0.763 | 280 | −0.05 | 0.07 | 0.486 | 159 | +0.03 | 0.10 | 0.728 | |

| VDR3: GAA (0, 1, 2) | 295 | −0.16 | 0.08 | 0.061 | 165 | +0.08 | 0.14 | 0.538 | 280 | +0.22 | 0.11 | 0.052 | 159 | +0.01 | 0.14 | 0.966 | |

| Megalin1: GCC (0, 1, 2) | 295 | +0.16 | 0.74 | 0.02845 | 165 | −0.14 | 0.09 | 0.129 | 280 | +0.17 | 0.07 | 0.02156 | 159 | −0.18 | 0.09 | 0.052 | |

| Megalin2: ACC (0, 1, 2) | 295 | −0.10 | 0.10 | 0.239 | 165 | +0.11 | 0.10 | 0.309 | 280 | −0.03 | 0.08 | 0.724 | 159 | +0.13 | 0.10 | 0.228 | |

| Megalin3: GTT (0, 1, 2) | 295 | −0.09 | 0.11 | 0.4385 | 165 | +0.15 | 0.13 | 0.221 | 280 | −0.13 | 0.11 | 0.2335 | 159 | +0.20 | 0.13 | 0.131 | |

| Cognitive domain 2: models A–F | |||||||||||||||||

| VDR1: GCA (0, 1, 2) | 295 | +0.03 | 0.06 | 0.630 | 165 | −0.090 | 0.067 | 0.181 | 280 | +0.00 | 0.06 | 0.985 | 159 | −0.07 | 0.07 | 0.326 | |

| VDR2:AAG (0, 1, 2) | 295 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.876 | 165 | +0.10 | 0.06 | 0.126 | 280 | −0.00 | 0.05 | 0.941 | 159 | +0.07 | 0.07 | 0.292 | |

| VDR3: GAA (0, 1, 2) | 295 | −0.04 | 0.08 | 0.619 | 165 | −0.04 | 0.10 | 0.712 | 280 | +0.02 | 0.08 | 0.795 | 159 | −0.02 | 0.10 | 0.868 | |

| Megalin1: GCC (0, 1, 2) | 295 | −0.07 | 0.06 | 0.193 | 165 | +0.00 | 0.06 | 0.959 | 280 | −0.07 | 0.05 | 0.223 | 159 | −0.03 | 0.07 | 0.619 | |

| Megalin2: ACC (0, 1, 2) | 295 | −0.00 | 0.06 | 0.966 | 165 | +0.04 | 0.07 | 0.587 | 280 | +0.02 | 0.06 | 0.738 | 159 | +0.04 | 0.07 | 0.553 | |

| Megalin3: GTT (0, 1, 2) | 295 | +0.06 | 0.08 | 0.505 | 165 | −0.06 | 0.09 | 0.495 | 280 | +0.05 | 0.08 | 0.556 | 159 | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.948 | |

Note that VDR1, VDR2, VDR3 denote VDR SNPHAPs, whereas Megalin1, Megalin2, and Megalin3 denote Megalin SNPHAPs. (0, 1, 2) refers to ordinal coding with 0, 1, and 2 copies of each haplotype. Three VDR SNPs were combined to form the haplotypes, namely BsmI, ApaI, and TaqI. Only haplotypes 1 through 3 were selected for megalin because their overall prevalence was >10%. BLSA, Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging; BVRT, Benton Visual Retention Test; CVLT-List A, California Verbal Learning Test, List A; CVLT-DR, California Verbal Learning Test, Delayed Recall; DS-B, Digits Span Backward; DS-F, Digits Span Forward; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; OLS, ordinary least squares; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; SNPHAP, single nucleotide polymorphism haplotype; Trails A, Trailmaking Test, part A; Trails B, Trailmaking Test, part B; VDR, vitamin D receptor gene; VFT-C, Verbal Fluency Test-Categorical; VFT-L, Verbal Fluency Test-Letter.

Cognitive scores were predicted at mean age at follow-up before the onset of dementia or for all time points by using a linear mixed model controlled for sex, race-ethnicity, education (y), and smoking status, with age added among the fixed-effects variables to allow for quadratic nonlinear change. The slope or annual rate of change was predicted from these models at the mean age at follow-up (ie, between age 50 y and the individual mean age of follow-up for each cognitive test). By using factor analysis, 2-factor scores were estimated and were labeled as Longitudinal Annual Rate of Cognitive Change in the following domains: domain 1, “Memory and executive function: earlier decline”; domain 2, “Verbal fluency and attention: later decline” (see Supplemental Material 2 under “Supplemental data” in the online issue for more details). See Figure 1 for more details on definition of the SNPHAPs.

On the basis of multiple OLS regression models with outcome being cognitive annual rate of change and main exposures being the 3 megalin and VDR SNP haplotypes. Each haplotype was entered separately in each of the six models per outcome (models A-F). The model controlled for first-visit age, mean age at follow-up, education, first-visit smoking status, first-visit self-reported type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and BMI.

Marginally significant main effects after family-wise Bonferroni correction: P < 0.05 for MMSE or BVRT or cognitive domains and P < 0.025 for other cognitive tests.

P < 0.05 for the null hypothesis that sex × SNPHAP interaction term = 0 in a model in which the main effect of sex was added.

Significant main effects after family-wise Bonferroni correction: P < 0.025 for MMSE and cognitive domains and P < 0.0125 for other cognitive tests.

Among women only, VDR1 (GCA) was associated with greater decline with the VFT-C (prediction I: β = −0.031, P = 0.012; P < 0.05 for sex × SNPHAP interaction). VDR2 (AAG), however, was associated with a marginally significant slower decline in women only (prediction I) with the MMSE (β = +0.017, P = 0.042). The third VDR SNPHAP (VDR3: GAA) was associated with marginally significant slower decline in men only with the MMSE (prediction II: β = +0.014, P = 0.047; P < 0.05 for sex × SNPHAP interaction), the CVLT-List A (prediction I: β = +0.059, P = 0.025; prediction II: β = +0.052, P = 0.019; P > 0.05 for sex × SNPHAP interaction), and the CVLT-DR (prediction II: β = +0.013, P = 0.018; P < 0.05 for sex × SNPHAP interaction).

When megalin SNPHAPs were examined in relation to LARCCs, several key findings emerged. Megalin1 (GCC) was associated with a significantly faster decline with the CVLT-List A among women (prediction II: β = −0.043, P = 0.006). For the CVLT-DR, however, a slower decline was found among men (prediction I: β = +0.011, P = 0.009; prediction II: β = +0.010, P = 0.007), although the associations were not significant among women. However, for both cognitive test scores and predictions, sex differences were significant (P < 0.05 for sex × SNPHAP interaction). Megalin1 (GCC) was also associated with slower decline for cognitive domain 1 among men only (prediction II: β = +0.17, P = 0.021; P < 0.05 for sex × SNPHAP interaction). To assess confounding effects of covariates included in the latter model (prediction II, cognitive domain 1), a change-in-estimate analysis was conducted with backward elimination of covariates. This analysis indicated that the strongest confounding effect was found for education (years) among men, whereas among women baseline age, smoking status, education, and sample selectivity were found to affect the estimate in an appreciable manner (>7% change in estimate; data not shown).

The Megalin2 (ACC) SNPHAP was associated with slower cognitive decline among women with the VFT-C (prediction II: β = +0.026, P = 0.005), without significant sex differences. There was no significant link between Megalin3 SNPHAP (GTT) and decline on any of the cognitive test scores. A sensitivity analysis was conducted in which the 2 principal components analysis factor scores were added to each model to address the issue of the residual effects of population structure within the sample. This adjustment did not alter any of our key findings, particularly the strong positive association between the Megalin1 SNPHAP (GCC) and LARCC in cognitive domain 1 (reflecting less decline) among men.

DISCUSSION

We examined associations of SNPs for VDR [rs11568820 (CdX-2:T/C), rs1544410 (BsmI:G/A), rs7975232 (ApaI:A/C), rs731236 (TaqI:G/A)] and Megalin [rs3755166:G/A; rs2075252:C/T; rs4668123:C/T] genes with longitudinal cognitive performance changes. Data from 702 non-Hispanic white BLSA participants were used. LARCCs between age 50 y and the age at individual mean follow-up were predicted with linear mixed models by using all cognitive score time points (prediction I) or time points before dementia onset (prediction II). LC, haplotype, and OLS regression analyses were conducted. Among many key findings, in OLS models with SNP LCs as predictors for LARCC, Megalin2 [rs3755166(–)/rs2075252(TT)/rs4668123(T−)] compared with Megalin1 [rs3755166(–)/rs2075252(CC)/rs4668123(–)] was associated with greater decline among men in verbal memory (prediction II), with significant sex differences (P < 0.05). When examining SNPHAPs, in women VDR1 [BsmI(G−)/ApaI(C−)/TaqI(A−); baT] was linked to greater decline in category fluency (prediction I: β = −0.031, P = 0.012). The Megalin1 SNPHAP (GCC) was related to greater decline among women in verbal memory, immediate recall (CVLT-List A; prediction II: β = −0.043, P = 0.006), but slower decline among men in delayed recall (CVLT-DR: β > 0, P < 0.0125; both predictions). In women, the Megalin2 SNPHAP (ACC) was associated with slower decline in category fluency (VFT-C; prediction II: β = +0.026, P = 0.005). Another finding was that Megalin SNP rs3755166:G/A was associated with greater decline in global cognition in both sexes combined and in verbal memory in men.

Four recent studies have examined Megalin (20, 36) and VDR (18, 19) genetic polymorphisms as potential risk markers for cognitive impairment or, more specifically, AD. Overall, cognitive impairment risk appears to be associated with various genetic SNPs and haplotypes pertaining to megalin and VDR. In a case-control study (1158 patients with sporadic AD compared with 1025 healthy controls), out of 3 megalin SNPs (rs3755166, rs2075252, rs4668123), only one (rs3755166:G/A) was found to be associated with apparent increased AD risk. Note that the rs3755166 “A” variant had 20% less transcriptional activity than did the “G” variant (20).

This finding was replicated by a recent case-control study in Chinese middle-aged and older adults (n = 361), in which cases were found to be 38% more likely than controls to have the “A” variant of that SNP (rs3755166 G/A: OR: 1.38; 95% CI: 1.02, 1.87; P = 0.039) (36). Similarly, in our study, we found a marginally significant inverse relation between rs3755166 G→A and MMSE LARCC, indicative of greater cognitive decline for the “A” variant SNP. Moreover, this SNP variant was associated with significantly greater decline in verbal memory among men only, even after correction for multiple testing. Whereas the previously described study (20) did not find a significant relation between rs2075252 or rs4668123 and AD, our present study found that the rs2075252 SNP LC (TT compared with CC) may be associated with greater decline in verbal memory (CVLT-DR), particularly before the onset of dementia and more so among men.

When testing VDR SNP associations with AD, a recent case-control study (104 patients with late-onset AD compared with 109 age-matched controls) found that heterozygous ApaI genotype (AC) was linked to an increased risk of AD, compared with homozygous AA genotype (19). In our study, we found only a marginally significant P-trend (P < 0.10), indicating that AA may be protective against cognitive decline compared with AC and CC, particularly for changes in global cognitive performance and verbal memory, when all time points were considered (ie, MMSE and CVLT-List A; prediction I). However, this association was deemed nonsignificant after correction for multiple testing. In a recent prospective population-based cohort study (Leiden 85-plus Study; n = 563) that examined 5 VDR SNPs in relation to cognitive functioning at follow-up, a number of key findings were reported (18). Three of 5 SNPs were associated with cognitive function, namely BsmI, ApaI, and TaqI. In contrast to the study by Gezen-Ak et al (19), ApaI (A/C) variant allele (ie, CC or AC compared with AA) was associated with better cognitive function at follow-up, particularly in immediate recall (18). In our present study, SNPHAPs combining BsmI, ApaI, and TaqI were associated with cognitive change. Specifically, after correction for multiple testing, the VDR1 SNPHAP (GCA or baT) was associated with greater decline with the VFT-C among women but not among men, a finding that was not replicated by Kuningas et al (18), who found that worse performance was, in fact, ascribed to the VDR2 SNPHAP (AAG), which they labeled as BAt.