Abstract

Background: Children with moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) are often treated with fortified blended flours, most commonly a corn-soy blend (CSB). However, recovery rates remain <75%, lower than the rate achieved with peanut paste–based ready-to-use supplementary foods (RUSFs). To bridge this gap, a novel CSB recipe fortified with oil and dry skim milk, “CSB++,” has been developed.

Objective: In this trial we compared CSB++ with 2 RUSF products for the treatment of MAM to test the hypothesis that the recovery rate achieved with CSB++ will not be >5% worse than that achieved with either RUSF.

Design: We conducted a prospective, randomized, investigator-blinded, controlled noninferiority trial involving rural Malawian children aged 6–59 mo with MAM. Children received 75 kcal CSB++ · kg−1 · d−1, locally produced soy RUSF, or an imported soy/whey RUSF for ≤12 wk.

Results: The recovery rate for CSB++ (n = 763 of 888; 85.9%) was similar to that for soy RUSF (795 of 806, 87.7%; risk difference: −1.82%; 95% CI: −4.95%, 1.30%) and soy/whey RUSF (807 of 918, 87.9%; risk difference: −1.99%; 95% CI: −5.10%, 1.13%). On average, children who received CSB++ required 2 d longer to recover, and the rate of weight gain was less than that with either RUSF, although height gain was the same among all 3 foods studied.

Conclusions: A novel, locally produced, fortified blended flour (CSB++) was not inferior to a locally produced soy RUSF and an imported soy/whey RUSF in facilitating recovery from MAM. The recovery rate observed for CSB++ was higher than that for any other fortified blended flour tested previously. This trial is registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT00998517.

INTRODUCTION

Worldwide, ∼10% of children are wasted and children with MAM6, defined as a weight-for-height z score (WHZ) between −2 and −3 have an excess mortality risk ∼3 times that of children with even mild malnutrition (1). Children with MAM also experience a greater burden of infectious diseases, delayed cognitive development, and decreased adult stature and productivity (2–4).

Fortified blended flours, specifically CSB, are the most commonly used supplementary foods for MAM (5–7). CSB can often be made from locally available, low-cost ingredients and are culturally and organoleptically acceptable in many settings. However, concerns exist that a low micronutrient content and bioavailability, low energy density, high fiber and antinutrient content, and ration sharing (8) may contribute to recovery rates, which are as low as 24% in operational emergency settings (6) and <75% in controlled research trials (9).

After the 2007 international joint statement recommending the use of ready-to-use therapeutic food for the treatment of SAM (10), similar peanut paste–based RUSF have been developed that are effective for the treatment of MAM (9, 11, 12). RUSF are energy dense, are much less likely to support the growth of bacteria because of their low moisture content, do not require cooking, and have led to greater recovery rates than CSB in direct comparisons (9).

Currently, the estimated 35 million children who suffer from MAM are left with a largely ineffective but affordable therapy, CSB, whereas far fewer children receive a highly effective but costly intervention, RUSF. The World Food Program has recently attempted to bridge this gap with a revised CSB recipe, “CSB++”—which includes dry skim milk and is more energy dense—and a revised micronutrient profile. CSB++ is designed for targeted therapy of children with MAM and for feeding vulnerable children 6 mo to 2 y of age (13).

In this prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial we compared CSB++ with 2 RUSF products in the treatment of MAM to test the hypothesis that the proportion of children who recover after receiving CSB++ will not be >5% worse than children who receive either RUSF. In addition to a locally produced soy RUSF (9, 12), an imported commercially available soy/whey RUSF was chosen as a comparator because it is available commercially and contains animal source food.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Subjects and setting

Children aged 6–59 mo with MAM (WHZ <−2 and ≥−3 without bipedal edema) were recruited at 18 rural therapeutic feeding clinics in southern Malawi. Children were excluded if they were simultaneously involved in another research trial or supplementary feeding program, had a chronic debilitating illness (not including HIV or tuberculosis), or had a history of peanut allergy. Children were also excluded if they had received therapy for acute malnutrition within 1 mo before presentation so as to focus the study primarily on the initial treatment of MAM.

Participants came from families of subsistence farmers; the staple crop in this region, maize, is gathered from household-level gardens during a single annual harvest (14). Animal products constitute only a small portion of the diet, contributing 2–7% of the energy intake of infants (15). An estimated 10–23% of rural pregnant Malawians are HIV-positive (16–18). Considering rates of vertical transmission of HIV, the projected childhood HIV prevalence is 0.2–2% (16, 19). Stunting is found in 53% of Malawian children aged <5 y (20). The study was approved by the College of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee at the University of Malawi and the Human Research Protection Office at Washington University in St Louis.

Study design

This was a randomized, investigator-blinded, controlled clinical noninferiority trial that assessed the treatment of MAM with CSB++, for a period of ≤12 wk, using the 2 RUSF products as active comparators. Children were defined as having recovered when they reached a WHZ ≥−2; otherwise, they were categorized as having continued MAM despite 12 wk of therapy, had developed SAM (WHZ <−3 and/or pedal edema), were transferred to inpatient care, died, or defaulted (did not return for 3 consecutive visits). Secondary outcomes included time to recovery, rate of adverse events (allergic reactions, vomiting, and diarrhea), and rates of gain in weight, length, and MUAC. If the child was a twin, an additional supply of food was given to the caretaker to ensure that the child received a full ration and to limit sharing between the twins. If 2 study participants were from the same household, both children were given the same type of food to reduce the likelihood of confounding study foods.

The planned sample size for the study was 900 children in each study arm. This sample size would be sufficient to detect a recovery rate difference of ≥5% between CSB++ and either RUSF, at a significance level of 0.05 with 80% power, assuming a recovery rate with RUSF of 85%. Given the lower cost and increased local production capacity for CSB++ compared with RUSF, a difference in recovery rates of ≤5% was considered to be sufficiently noninferior for this common condition.

A block randomization list was created by using a computer random number generator. Allocation was performed by caregivers drawing opaque envelopes containing 1 of 9 coded letters corresponding to 1 of the 3 supplementary foods. This code was accessible only to the food distribution personnel, who did not assess participant outcomes or eligibility. The investigators who performed the clinical assessments were blinded to the child's assigned food group. The children and caregivers could not be blinded because the 3 supplementary foods differed in taste, appearance, and preparation required.

Participation

Children presenting to a clinic site were evaluated for acute malnutrition by trained nutrition researchers and senior pediatric research nurses. Standard methods for anthropometric measurements were used (21): weight was measured with an electronic scale to the nearest 5 g, length was measured in triplicate to the nearest 0.5 cm with a canvas mat or to the nearest 0.2 cm with a rigid length board, and MUAC was measured with a standard insertion tape to the nearest 0.2 cm. After extensive training by one of the physicians supervising the study (IT or MJM), field nutrition researchers also evaluated the children for edematous malnutrition (kwashiorkor) by assessing for bilateral pitting edema. The caregivers of children who met enrollment criteria gave verbal and written consent before randomization.

On enrollment, caregivers were interviewed regarding the child's demographic characteristics, appetite, infectious symptoms, gross motor development, and antibiotic use during the prior 2 wk. Caregivers were also administered the 9-item HFIAS, a tool used to assess household access to food, which was developed by the Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project (22, 23). Nutrition and general health counseling was also provided to all caretakers.

A ration of supplementary food sufficient for 2 wk was distributed at each visit. Children returned every 2 wk for follow-up for up to 6 follow-up visits, at which time caretakers reported on the child's clinical symptoms and tolerance of the study food, anthropometric measurements were repeated, and additional supplementary food was distributed for those who remained wasted. Children who developed SAM during the study and/or remained malnourished at the end of 12 wk of follow-up were considered to have failed therapy for MAM and were treated with ready-to-use therapeutic food as outpatients (10) or transferred to inpatient care, as clinically appropriate in each case. Children who missed the biweekly visits were sought by village health workers at their homes.

Food products and distribution

Participants received ∼75 kcal (314 kJ) CSB++ · kg−1 · d−1, soy RUSF, or soy/whey RUSF. CSB++ is less energy dense, has more protein per dose, and has less fat per dose than the RUSF products (Table 1). No matter which food a child was randomly assigned to receive, the study nurses gave the caregivers identical information about the illness of their children, the benefits of supplementary feeding, feeding the supplement only to the enrolled child and not to share it, feeding the supplement in addition to the usual diet, how to store unfinished portions of the supplement, and spacing out the use of the daily portions to last until the next biweekly distribution. Additional instructions were given to caregivers of children in the CSB++ arm about how to prepare the supplement properly, ie, using a ratio of ∼5 parts water to 1 part dry flour.

TABLE 1.

Nutrient composition of the supplementary foods per daily ration for a 7.5-kg child1

| CSB++ | Soy RUSF | Soy/whey RUSF | Dietary ReferenceIntake for 1–3-y-old children (26) | |

| Dry mass of supplementary food (g) | 143 | 104 | 103 | — |

| Energy (kcal) | 563 | 563 | 563 | — |

| Protein (g) | 21 | 17 | 15 | 13 |

| Fat (g) | 13 | 40 | 38 | — |

| Calcium (mg) | 579 | 332 | 324 | 500 |

| Copper (mg) | 0.7 | 3.0 | 1.9 | 0.3 |

| Iodine (μg) | 57 | 135 | 108 | 90 |

| Iron (mg) | 15 | 19 | 12 | 7 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 190 | 179 | 99 | 80 |

| Phosphorus (mg) | 396 | 233 | 324 | 460 |

| Potassium (mg) | 1426 | 1601 | 1198 | 3000 |

| Selenium (μg) | 21 | 46 | 32 | 20 |

| Zing (mg) | 11 | 19 | 15 | 3 |

| Folic acid (μg) | 171 | 430 | 237 | 150 |

| Vitamin A (μg) | 714 | 1406 | 981 | 300 |

| Thiamine (mg) | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.5 |

| Riboflavin (mg) | 1.2 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 0.5 |

| Niacin (mg) | 11 | 8.7 | 5.7 | 6 |

| Pantothenic acid (mg) | 11 | 5.2 | 3.3 | 2 |

| Vitamin B-6 (mg) | 3.1 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| Biotin (mg) | — | 93.6 | 70 | 8 |

| Vitamin B-12 (μg) | 3.3 | 2.9 | 2.0 | 0.9 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 145 | 76 | 95 | 15 |

| Vitamin D (μg) | 8.1 | 23 | 20 | 5 |

| Vitamin E (mg) | 12 | 32 | 23 | 6 |

| Vitamin K (μg) | 161 | 48 | 24 | 30 |

CSB++, corn-soy blend “plus-plus”; RUSF, ready-to-use supplementary food.

CSB++ was produced by Rab Processors in Blantyre, Malawi, according to specifications from the World Food Program. CSB++ contains corn flour, soy flour, soy oil, dried skim milk, and concentrated minerals and vitamins (DSM). CSB++ contains 0.5 g protein from milk per average daily ration. CSB++ costs US$1.10/kg, or US$0.16 for an average daily ration (one-half of a sealed plastic bag weighing 250 g).

Soy RUSF was produced by Project Peanut Butter in Blantyre, Malawi (24), by using extruded soy flour, peanut paste, sugar, soy oil, a premix containing concentrated minerals and vitamins (Nutriset), and dicalcium phosphate or calcium carbonate (Roche). Soy RUSF has no protein from animal sources. Soy RUSF cost US$2.13/kg, or US$0.22 for an average daily ration (1 sachet weighing 92 g).

Soy/whey RUSF (Plumpy'Sup; Nutriset) contains peanut paste, sugar, vegetable fat, whey, soy protein isolates, maltodextrin, and cocoa and is enriched with a mineral and vitamin complex. Soy/whey RUSF contains 2 g protein from whey (an animal source food) per average daily ration. Soy/whey RUSF costs US$3.59/kg, or US$0.38 for an average daily ration (1 sachet weighing 92 g).

The 2 locally produced products underwent quality assurance and safety testing for aflatoxin and microbial contamination at the Malawi Bureau of Standards and Eurofins Scientific Inc. Soy/whey RUSF underwent quality and safety testing at Nutriset and at the Laboratoire de Rouen (Rouen, France).

Data analyses

Anthropometric indexes were based on the WHO's 2006 Child Growth Standards (25), calculated by using Anthro v 3.1 (WHO). Weight gain (in g · kg−1 · d−1), relative to the enrollment weight, was calculated for graduates over the first 4 wk (or less if they graduated earlier) of enrollment. Length and MUAC gain (in mm/d) were calculated over the entire duration of study participation. Comparisons of outcomes between types of supplementary foods were made by using Fisher's exact test for dichotomous variables and Student's t test for continuous variable. The log-rank test was used to compare the graduation rates over time between the 3 foods. P values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Binary logistic regression (IBM SPSS Statistics 16.0) was used to identify risk factors for failure to recover that could be identified at the time of enrollment. Independent variables used in the model were enrollment WHZ and HAZ, history of testing for HIV and known HIV infection in both the children and their mothers, current treatment of tuberculosis, current treatment with antibiotics, whether the mother was the primary caretaker, whether the caretaker reported the child was eating well at the time of enrollment, season of enrollment, HFIAS score, the ability to stand without assistance (as a marker of gross motor development), and the number of days of fever, vomiting, cough, and diarrhea within the 2 wk before enrollment.

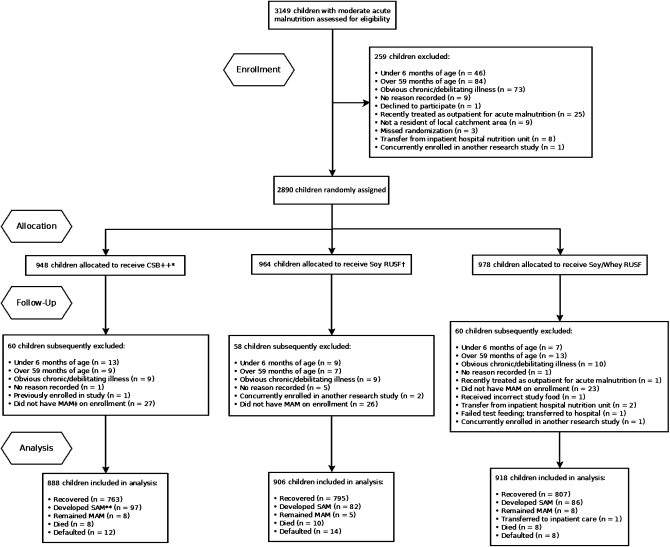

RESULTS

A total of 2712 children were enrolled in the study from October 2009 to December 2010 (Figure 1, Table 2). No adverse reactions to any of the study foods were reported. The proportion of children who recovered was similar for all 3 supplementary foods: 85.9% for CSB++ (95% CI: 83.5%, 88.1%), 87.7% for soy RUSF (95% CI:85.5%, 89.8%), and 87.9% for soy/whey RUSF (95% CI: 85.7%, 89.9%) (P > 0.3) (Table 3). The risk difference for recovery for CSB++ compared with soy RUSF was −1.82% (95% CI: −4.95%, 1.30%) and was −1.99% (95% CI: −5.10%, 1.13%) compared with soy/whey RUSF. The risk difference for soy RUSF compared with soy/whey RUSF was −0.16% (95% CI: −3.16%, 2.84%). Soy/whey RUSF showed superior rates of weight and MUAC gain compared with CSB++ and a superior rate of MUAC gain compared with soy RUSF. Children who received CSB++, soy RUSF, or soy/whey RUSF developed kwashiorkor with similar frequency (4.3%; 95% CI: 3.9%, 5.1%; P > 0.4). Children who received CSB++ developed severe wasting (WHZ < −3) more frequently than did those who received soy/whey RUSF (6.6% compared with 4.2%; P < 0.03).

FIGURE 1.

Flow of participants throughout the study. *CSB++, corn-soy blend “plus-plus.” †RUSF, ready-to-use supplementary food. ‡MAM, moderate acute malnutrition. **SAM, severe acute malnutrition.

TABLE 2.

Enrollment characteristics of children treated for moderate acute malnutrition1

| CSB++(n = 888) | Soy RUSF(n = 906) | Soy/whey RUSF(n = 918) | |

| Female sex [n (%)] | 539 (61) | 562 (62) | 583 (64) |

| Age [n (%)] | 19.6 ± 11.02 | 19.5 ± 10.8 | 19.3 ± 11.0 |

| 6–11 mo | 245 (28) | 258 (28) | 275 (30) |

| 12–17 mo | 230 (26) | 246 (27) | 248 (27) |

| 18–23 mo | 175 (20) | 168 (19) | 164 (18) |

| 24–35 mo | 164 (19) | 162 (18) | 143 (16) |

| 36–59 mo | 71 (8) | 72 (8) | 86 (9) |

| Weight (kg) | 7.38 ± 1.62 | 7.36 ± 1.57 | 7.35 ± 1.55 |

| MUAC (cm) | 12.1 ± 1.0 | 12.2 ± 1.0 | 12.2 ± 1.0 |

| WHZ [n (%)] | −2.31 ± 0.38 | −2.28 ± 0.38 | −2.30 ± 0.38 |

| HAZ [n (%)] | −2.83 ± 1.40 | −2.86 ± 1.33 | −2.74 ± 1.33 |

| HAZ ≤−2 [n (%)] | 655 (74) | 682 (75) | 662 (72) |

| HAZ ≤−3 [n (%)] | 381 (43) | 386 (43) | 387 (42) |

| Mother alive [n (%)] | 868/887 (98) | 893/905 (99) | 899/918 (98) |

| Father alive [n (%)] | 857/886 (97) | 880/904 (97) | 886/917 (97) |

| Breastfeeding [n (%)] | 572/888 (64) | 597/906 (66) | 601/918 (65) |

| Mother known to be HIV+ [n (%)] | 94/888 (11) | 83/906 (9) | 77/918 (8) |

| Outpatient health center visit during prior 2 wk [n (%)] | 349/816 (43) | 356/829 (43) | 375/828 (45) |

| Known to have received antibiotics during prior 2 wk [n (%)] | 97/888 (11) | 88/906 (10) | 105/918 (11) |

| Reported to have good appetite [n (%)] | 761/881 (86) | 762/899 (85) | 757/906 (84) |

| Twin [n (%)] | 32/887 (4) | 57/902 (6) | 57/916 (6) |

| HFIAS score | 6.3 ± 5.3 | 6.1 ± 5.0 | 6.3 ± 5.2 |

| HFIAS category (23) [n/N (%)] | |||

| Food secure | 156/888 (18) | 164/905 (18) | 170/917 (19) |

| Mild food insecurity | 73/888 (8) | 61/905 (7) | 70/917 (8) |

| Moderate food insecurity | 200/888 (23) | 215/905 (24) | 198/917 (22) |

| Severe food insecurity | 459/888 (52) | 465/905 (51) | 479/917 (52) |

| Fever in prior 2 wk [n (%)] | 538 (61) | 545 (60) | 549 (60) |

| Cough in prior 2 wk [n (%)] | 461 (52) | 490 (54) | 488 (53) |

| Diarrhea in prior 2 wk [n (%)] | 397 (45) | 400 (44) | 419 (46) |

| Vomiting in prior 2 wk [n (%)] | 213 (24) | 190 (21) | 241 (26) |

CSB++, corn-soy blend “plus-plus”; HAZ, height-for-age z score; HFIAS, Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (a higher score indicates more food insecurity, maximum 27); MUAC, midupper arm circumference; RUSF, ready-to-use supplementary food; WHZ, weight-for-age z score.

Mean ± SD (all such values).

TABLE 3.

Outcomes of moderately wasted Malawian children who received ∼75 kcal · kg−1 · d−1 of supplementary food1

| CSB++(n = 888) | Soy RUSF(n = 906) | Soy/whey RUSF(n = 918) | |

| Clinical outcome | |||

| Recovered | |||

| n (%) | 763 (85.9) | 795 (87.7) | 807 (87.9) |

| 95% CI | (83.5, 88.1) | (85.5, 89.8) | (85.7, 89.9) |

| Developed severe acute malnutrition | |||

| Severe wasting, WHZ <−3 | |||

| n (%) | 59 (6.6)2 | 47 (5.2) | 39 (4.2) |

| 95% CI | (5.1, 8.4) | (3.9, 6.8) | (3.1, 5.7) |

| Kwashiorkor | |||

| n (%) | 38 (4.3) | 35 (3.9) | 47 (5.1) |

| 95% CI | (3.1, 5.8) | (2.8, 5.3) | (3.8, 6.7) |

| Continued moderate acute malnutrition despite 12 wk of therapy | |||

| n (%) | 8 (0.9) | 5 (0.6) | 8 (0.9) |

| 95% CI | (0.4, 1.7) | (0.2, 1.2) | (0.4, 1.6) |

| Died | |||

| n (%) | 8 (0.9) | 10 (1.1) | 8 (0.9) |

| 95% CI | (0.4, 1.7) | (0.6, 2.0) | (0.4, 1.6) |

| Defaulted | |||

| n (%) | 12 (1.4) | 14 (1.5) | 8 (0.9) |

| 95% CI | (0.7, 2.3) | (0.9, 2.5) | (0.4, 1.6) |

| Transferred to inpatient therapy | |||

| n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) |

| 95% CI | (0, 0.3) | (0, 0.3) | (0, 0.5) |

| Diarrhea during first 2 wk of therapy | 271 (31) | 303 (34) | 309 (34) |

| Vomiting during first 2 wk of therapy | 89 (10)2,3 | 127 (14)3 | 124 (14) |

| Good appetite at first follow-up visit | |||

| n/N (%) | 838/861 (97.3) | 837/868 (96.4) | 863/892 (96.7) |

| 95% CI | (96.1, 98.3) | (95.0, 97.5) | (95.4, 97.8) |

| WHZ on completion | −1.68 ± 0.674 | −1.61 ± 0.63 | −1.59 ± 0.60 |

| Weight gain (g · kg−1 · d−1) | 3.1 ± 2.45 | 3.4 ± 2.6 | 3.6 ± 2.8 |

| Length gain (mm/d) | 0.13 ± 0.46 | 0.13 ± 0.44 | 0.15 ± 0.47 |

| MUAC gain (mm/d) | 0.13 ± 0.405 | 0.13 ± 0.435 | 0.21 ± 0.44 |

| Time to recovery (d) | 24.9 ± 17.567 | 22.5 ± 14.2 | 22.6 ± 15.0 |

CSB++, corn-soy blend “plus-plus”; MUAC, midupper arm circumference; RUSF, ready-to-use supplementary food; WHZ, weight-for-height z score.

Significantly different from soy/whey RUSF, P < 0.03 (Fisher's exact test).

Significantly different from soy RUSF, P < 0.01 (Fisher's exact test).

Mean ± SD (all such values).

Significantly different from soy/whey RUSF (t test): 5P < 0.001, 6P < 0.006.

Significantly different from soy RUSF, P < 0.003 (t test).

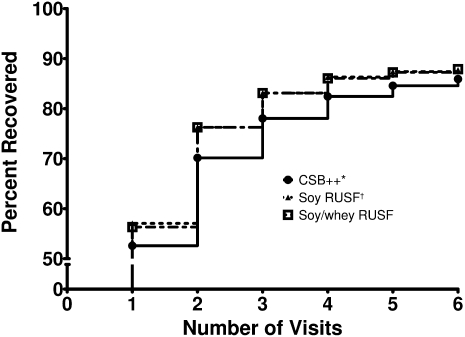

The mean duration of treatment required to achieve recovery was 23 d; children who received CSB++ took on average of 2 d longer to recover (ANOVA, P < 0.003). More than half of the children in each food group recovered within the first 2 wk of therapy (Figure 2). No significant difference in the primary outcome was observed on the basis of HFIAS category at enrollment. However, children in the HFIAS “Severe Food Insecurity” category required longer to graduate if they received CSB++, whereas children in less severe categories had similar times to recovery (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Recovery of children with moderate acute malnutrition treated with 1 of 3 supplementary foods. Log-rank test for trend, P ≈ 0.13. *CSB++, corn-soy blend “plus-plus”; †RUSF, ready-to-use supplementary food.

A total of 181 (6.7%) children missed a total of 198 visits. After these missed visits, 151 of 198 (76.3%) children had gained weight when they returned for follow-up after being off therapy for ≥7 d; 1.3% of children defaulted. Children who defaulted were less likely to have a good appetite reported by their caretakers on enrollment (68% compared with 85%; P < 0.02), had a lower MUAC-for-age z score on enrollment (−2.8 compared with −2.5; P < 0.02), and had more days of vomiting in the 2 wk before enrollment (1.8 compared with 0.7; P < 0.0001).

A comparison of children known to have HIV with those whose HIV status was negative or unknown showed that children with HIV recovered less frequently [53 of 84 (63%) compared with 2310 of 2628 (88%); P < 0.0001]. Of the failures, the rate of severe wasting was higher [19 of 31 (61%) compared with 126 of 318 (40%), P < 0.03] in those who were HIV-positive, whereas the development of kwashiorkor was less frequent [4 of 31 (13%) compared with 116 of 318 (36%); P < 0.01]. Of the children receiving ART, 19 of 24 (79.2%) recovered, whereas only 31 of 54 (57.4%) of those not receiving ART recovered (RR: 1.38; 95% CI: 1.01, 1.88). These results did not vary significantly on the basis of which supplementary food the child received.

Binary logistic regression modeling (Table 4) identified many factors as being predictive of recovery, including receiving antibiotics at the time of enrollment. HFIAS score and the type of food received (CSB++ compared with one of the RUSF formulations) were not significantly correlated with recovery or failure.

TABLE 4.

Binary logistic regression model of factors associated with recovery from moderate acute malnutrition after supplementary feeding1

| Independent variable | HR2 (95% CI) |

| Child enrolled in season after harvest (April–July) | 2.07 (1.52, 2.81)3 |

| Child able to stand without assistance | 2.02 (1.58, 2.58)3 |

| Child taking antibiotics at time of enrollment | 1.75 (1.13, 2.70)3 |

| Mother as primary caretaker | 1.46 (0.85, 2.51) |

| Mother has had HIV test | 1.37 (1.03, 1.84)3 |

| Caretaker reports child eating well at time of enrollment | 1.25 (0.90, 1.73) |

| Child received either soy RUSF or soy/whey RUSF | 1.13 (0.88, 1.46) |

| Days of vomiting in 2 wk before enrollment | 1.10 (1.02,1.18)3 |

| Days of cough in 2 wk before enrollment | 1.00 (0.94, 1.05) |

| Days of diarrhea in 2 wk before enrollment | 0.99 (0.93, 1.04) |

| Household Food Insecurity Access Scale score | 0.98 (0.96, 1.01) |

| Days of fever in 2 wk before enrollment | 0.95 (0.90, 1.01) |

| Height-for-age z score | 0.90 (0.83, 0.99)3 |

| Mother known to be HIV-positive | 0.81 (0.52, 1.25) |

| Child has had HIV test | 0.57 (0.43, 0.76)3 |

| Child known to be HIV-positive | 0.46 (0.25, 0.83)3 |

| Weight-for-height z score | 0.43 (0.32, 0.59)3 |

| Child receiving TB treatment | 0.27 (0.08, 0.90)3 |

The model constant = 0.051; R2 = 0.065 by Cox and Snell, R2 = 0.121 by Nagelkerke, chi-square = 177. RUSF, ready-to-use supplementary food; TB, tuberculosis.

HR <1 indicates that as the independent variable increases, the risk of failure increases.

P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

In this clinical noninferiority trial, children with MAM who received CSB++ did not have significantly inferior recovery rates compared with those who received either RUSF product. Historically, children receiving fortified blended flours for MAM had recovery rates <75%, consistently lower than the recovery rate achieved in direct comparisons with RUSF (9). In this study, we have demonstrated that CSB++ is the first fortified blended flour to not be inferior to an RUSF product in the treatment of MAM.

The children enrolled in this study did not receive extra rations to accommodate for presumed sharing. This is in contrast with operational protocols for standard fortified blended flour, which distribute 1000–1200 kcal/d (130–160 kcal · kg−1 · d−1) for the average child with MAM. This study had an exceptionally low default rate of 1.3%, much lower than that of previous studies, which had default rates of 4% to ≥5% (9, 11, 12). This is a reflection of the investment in the education of caretakers and follow-up of enrolled children by research personnel. The default rate between the 3 foods groups was similar; the few children lost to follow-up are, therefore, were unlikely to bias the study's findings.

An important risk factor identified as being associated with treatment failure was known HIV infection in the children. Those children receiving ART had a significantly lower failure rate than did those not receiving ART, which highlights the need for HIV diagnostic and therapeutic services to be programmatically linked to malnutrition treatment programs in areas with a high prevalence of HIV infection.

Major differences between CSB++ and CSB (9) include the following: increased energy density from the added oil, sugar, and dried skim milk; increased phosphorus (28% greater), potassium (49%), vitamin B-6 (316%), vitamin B-12 (121%), zinc (43%), riboflavin (62%), vitamin C (141%), and vitamin D (115%); the addition of vitamin K and pantothenic acid; tighter specifications regarding aflatoxin and coliform contamination; and a reduced antinutrient content through the inclusion of less soy beans and maize and the dehulling of the soy beans. Animal-source foods, such as milk and meat supplements, have been associated with improved linear growth, lean body mass, micronutrient status, physical activity, and school performance when compared with supplements that do not contain animal-source foods (27–30). Fortified lipid spreads higher in animal-source foods have been shown to be more effective in the treatment of SAM (31) but not previously for moderate acute malnutrition (9). Any or all of these nutritional differences may have contributed to the recovery rate observed with CSB++ in this study compared with prior studies with CSB.

The cost of the 3 foods was as follows: US$0.03 for CSB++, US$0.04 for soy RUSF, and US$0.07 for soy/whey RUSF per 100 kcal (418 kJ). Fortified blended flours, including CSB++, have certain operational limitations. They require preparation and are similar in taste and appearance to staple foods, which may encourage sharing. This is consistent with our finding that children living in severely food-insecure homes who received CSB++ took longer to graduate than did children who were receiving either RUSF. Because of CSB++’s lower energy density and the large amount of water needed for preparation, children treated with CSB++ need to eat >8 times the mass of food as children treated with RUSF, although this did not prove limiting in this study. In many programs, CSB is typically scooped from 25- to 50-kg bags into open containers brought by caregivers. It is possible that the packages used in this study, which contained ration for only 1–2 d, decreased the rates of contamination and spillage, promoted the use of the supplement as a special medicinal food for the child with MAM, and discouraged sharing.

The outcomes achieved by children who received soy RUSF were better than those observed in previous studies (9, 12), possibly because of the improved soy flour source (extruded rather than roasted soybeans). Whereas the proportion of children who recovered was similar among the 3 food groups, children who received soy/whey RUSF had greater weight and MUAC gains (Table 3). About 5% of children enrolled in this trial did not respond to supplementary feeding, but continued to lose weight and developed severe wasting. These children most likely had an untreated chronic illness, likely HIV infection in our context, rather than simple food insecurity. This proportion was slightly higher among children who received CSB++, which suggested that fortified-blended flours in certain households may be vulnerable to greater spoilage or sharing.

The 3 foods used in this study vary in ≥4 major characteristics: taste, energy density, animal source food content, and preparation required. Soy/whey RUSF contains cocoa, which makes it more palatable than soy RUSF. Soy/whey RUSF, like soy RUSF, has a higher energy density than CSB++. Soy/whey RUSF contains 4 times the quantity of animal-source protein in CSB++, whereas soy RUSF contains no animal-source protein, which perhaps suggests that animal-source foods are not essential in this context. Both RUSF products differ in taste, appearance, and preparation from local staples, which may decrease sharing compared with CSB++. Despite all of these differences, the observed outcomes were generally of minor clinical significance, particularly when considering that soy/whey RUSF costs more than twice as much as CSB++. Long-term assessment of length gain, cognitive and motor development, infectious morbidity, rates of recurrence of acute malnutrition, and mortality will better inform whether the RUSF products are associated with clinically meaningful differences.

Variations in the recovery rates among the operational programs treating MAM with CSB varied widely, primarily because of differences in the default rate (6). In addition to the use of effective supplementary foods, decreasing the global morbidity and mortality from MAM is contingent on operational methods that optimize compliance. In this study, we believe that this was aided by pairing supplementary food distribution with health education, which reinforced MAM as an illness treatable with the “medicine” of supplementary food. Investigating the contribution of health education practices (32), within-household behaviors, food packaging and distribution, and other operational factors may reveal further opportunities to improve the clinical effectiveness of CSB++ and other supplementary foods now that efficacy has been demonstrated in this research context.

Stunting contributes a similar global burden of childhood mortality worldwide as wasting (1). Supplementary feeding with a fortified blended flour has been ineffective at ameliorating or preventing stunting (33, 34). More rapid linear growth in nutritionally vulnerable children is associated with milk consumption (35). The promising results of CSB++ in the treatment of MAM allows us to speculate whether it may play any role in reducing stunting, which should be investigated.

It is encouraging that this new fortified blended flour, CSB++, is associated with a recovery rate in children with MAM similar to that of 2 different RUSF products, because these flours are substantially less expensive and the infrastructure for their production may be more available. These results may signal the beginning of an informed shift from the use of ineffective flours or costly pastes to the implementation of a cost-effective flour for the treatment of MAM.

Acknowledgments

We thank Eleanor Chipofya, Rosemary Godwa, Lydia Kamenya, Jeanne Mbawa, Nester Mwase, Horris Chikwiri, Jackson Makwinja, and Vegas Riscado for their dedicated and tenacious service to the children of Malawi and Abbas Mukadam and Shrikant Mistry for their technical assistance in the production of soy RUSF. All authors have declared that they have no relevant personal, financial, or professional conflict of interests to report.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—LNL, IT, GJM, CT, KM, and MJM: designed the study; LNL, IT, GJM, RJW, and MJM: enrolled the patients and conducted the study; LNL, IT, and MJM: analyzed the data; LNL and IT: wrote the first draft of the manuscript; and MJM: had primary responsibility for the study's final content. All authors edited the manuscript and approved its final contents. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. All authors declared that they had no relevant personal, financial, or professional conflict of interests to report.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: ART, antiretroviral therapy; CSB, corn-soy blend; CSB++, corn-soy blend “plus-plus”; HAZ, height-for-age z score; HFIAS, Household Food Insecurity Access Scale; MAM, moderate acute malnutrition; MUAC, midupper arm circumference; RUSF, ready-to-use supplementary food; SAM, severe acute malnutrition; WHZ, weight-for-height z score.

REFERENCES

- 1.Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, de Onis M, Ezzati M, Mathers C, Rivera J. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet 2008;371:243–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shankar AH. Nutritional modulation of malaria morbidity and mortality. J Infect Dis 2000;182(suppl 1):S37–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berkman DS, Lescano AG, Gilman RH, Lopez SL, Black MM. Effects of stunting, diarrhoeal disease, and parasitic infection during infancy on cognition in late childhood: a follow-up study. Lancet 2002;359:564–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fishman SCL, de Onis M, Blossner M, Mullany L, Black RE. Malnutrition and the global burden of disease: underweight. Cambridge, MA: World Health Organization/Harvard University Press, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marchione TJ. Foods provided through U.S. Government Emergency Food Aid Programs: policies and customs governing their formulation, selection and distribution. J Nutr 2002;132:2104S–11S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navarro-Colorado C. A retrospective study of emergency supplementary feeding programmes. Save the Children/ENN, June 2007. Available from: http://www.ennonline.net/pool/files/research/Retrospective_Study_of_Emergency_Supplementary_Feeding_Programmes_June%20 2007.pdf (cited 30 May 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Pee S, Bloem MW. Current and potential role of specially formulated foods and food supplements for preventing malnutrition among 6-23 months old and treating moderate malnutrition among 6-59 months old children. Food Nutr Bull 2009;30(suppl):S434–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wood J, Sibanda-Mulder F. Improvement of fortified blended foods CSB products and Unimix. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/supply/files/8._Improvement_of_Fortified_Blended_Foods_CSB_Products_and_Unimix.pdf (cited 8 August 2011)

- 9.Matilsky DK, Maleta K, Castleman T, Manary MJ. Supplementary feeding with fortified spreads results in higher recovery rates than with a corn/soy blend in moderately wasted children. J Nutr 2009;139:773–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization, World Food Programme, United Nation System Standing Committee on Nutrition, The United Nation's Children's Fund. Community-based management of severe acute malnutrition. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nackers F, Broillet F, Oumarou D, Djibo A, Gaboulaud V, Guerin PJ, Rusch B, Grais RF, Captier V. Effectiveness of ready-to-use therapeutic food compared to a corn/soy-blend-based pre-mix for the treatment of childhood moderate acute malnutrition in Niger. J Trop Pediatr 2010;56:407–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lagrone L, Cole S, Schondelmeyer A, Maleta K, Manary MJ. Locally produced ready-to-use supplementary food is an effective treatment of moderate acute malnutrition in an operational setting. Ann Trop Paediatr 2010;30:103–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization, United Nations Children's Fund, World Food Programme, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Follow-up meeting of the joint WHO/UNICEF/WFP/UNHCR consultation on the dietary management of moderate malnutrition. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin CA, Boslaugh S, Ciliberto HM, Maleta K, Ashorn P, Briend A, Manary MJ. A prospective assessment of food and nutrient intake in a population of Malawian children at risk for kwashiorkor. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2007;44:487–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hotz C, Gibson RS. Complementary feeding practices and dietary intakes from complementary foods amongst weanlings in rural Malawi. Eur J Clin Nutr 2001;55:841–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maleta K, Virtanen SM, Espo M, Kulmala T, Ashorn P. Childhood malnutrition and its predictors in rural Malawi. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2003;17:384–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmed SD, Cuevas LE, Brabin BJ, Kazembe P, Broadhead R, Verhoeff FH, Hart CA. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C and HIV in Malawian pregnant women. J Infect 1998;37:248–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muzyka BC, Kamwendo L, Mbweza E, Lopez NB, Glick M, Matheson PB, Kershbaumer R, Nyrienda T, Malamud D, Constantine NT, et al. Prevalence of HIV-1 and oral lesions in pregnant women in rural Malawi. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2001;92:56–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miotti PG, Taha TE, Kumwenda NI, Broadhead R, Mtimavalye LA, Van der Hoeven L, Chiphangwi JD, Liomba G, Biggar RJ. HIV transmission through breastfeeding: a study in Malawi. JAMA 1999;282:744–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization World health statistics. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cogill B. Anthropometric indicators measurement guide. Washington, DC: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knueppel D, Demment M, Kaiser L. Validation of the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale in rural Tanzania. Public Health Nutr 2010;13:360–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coates J, Swindale A, Bilinsky P. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for measurement of food access: indicator guide. Washington, DC: USAID, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manary MJ. Local production and provision of ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) spread for the treatment of severe childhood malnutrition. Food Nutr Bull 2006;27(suppl):S83–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization WHO child growth standards: methods and development: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine, National Academies Dietary reference intakes: recommended intakes for individuals. Internet: http://www.iom.edu/Activities/Nutrition/SummaryDRIs/~/media/Files/Activity Files/Nutrition/DRIs/New Material/5DRI Values SummaryTables 14.pdf (cited 8 August 2011)

- 27.Dagnelie PC, van Staveren WA. Macrobiotic nutrition and child health: results of a population-based, mixed-longitudinal cohort study in The Netherlands. Am J Clin Nutr 1994;59(suppl):1187S–96S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grillenberger M, Neumann CG, Murphy SP, Bwibo NO, van't Veer P, Hautvast JG, West CE. Food supplements have a positive impact on weight gain and the addition of animal source foods increases lean body mass of Kenyan schoolchildren. J Nutr 2003;133(suppl 2):3957S–64S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siekmann JH, Allen LH, Bwibo NO, Demment MW, Murphy SP, Neumann CG. Kenyan school children have multiple micronutrient deficiencies, but increased plasma vitamin B-12 is the only detectable micronutrient response to meat or milk supplementation. J Nutr 2003;133(Suppl 2):3972S–80S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neumann CG, Murphy SP, Gewa C, Grillenberger M, Bwibo NO. Meat supplementation improves growth, cognitive, and behavioral outcomes in Kenyan children. J Nutr 2007;137:1119–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oakley E, Reinking J, Sandige H, Trehan I, Kennedy G, Maleta K, Manary M. A ready-to-use therapeutic food containing 10% milk is less effective than one with 25% milk in the treatment of severely malnourished children. J Nutr 2010;140:2248–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashworth A. Dietary counseling in the management of moderate malnourishment in children. Food Nutr Bull 2009;30:S405–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phuka JC, Maleta K, Thakwalakwa C, Cheung YB, Briend A, Manary MJ, Ashorn P. Complementary feeding with fortified spread and incidence of severe stunting in 6- to 18-month-old rural Malawians. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2008;162:619–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phuka JC, Maleta K, Thakwalakwa C, Cheung YB, Briend A, Manary MJ, Ashorn P. Postintervention growth of Malawian children who received 12-mo dietary complementation with a lipid-based nutrient supplement or maize-soy flour. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89:382–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takahashi E. Secular trend in milk consumption and growth in Japan. Hum Biol 1984;56:427–37 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]