Abstract

Background: Protein is an indispensable component within the human diet. It is unclear, however, whether behavioral strategies exist to avoid shortages.

Objective: The objective was to investigate the effect of a low protein status compared with a high protein status on food intake and food preferences.

Design: We used a randomized crossover design that consisted of a 14-d fully controlled dietary intervention involving 37 subjects [mean ± SD age: 21 ± 2 y; BMI (in kg/m2): 21.9 ± 1.5] who consumed individualized, isoenergetic diets that were either low in protein [0.5 g protein · kg body weight (BW)−1 · d−1] or high in protein (2.0 g protein · kg BW−1 · d−1). The diets were followed by an ad libitum phase of 2.5 d, during which a large array of food items was available, and protein and energy intakes were measured.

Results: We showed that in the ad libitum phase protein intake was 13% higher after the low-protein diet than after the high-protein diet (253 ± 70 compared with 225 ± 63 g, P < 0.001), whereas total energy intake was not different. The higher intake of protein was evident throughout the ad libitum phase of 2.5 d. In addition, after the low-protein diet, food preferences for savory high-protein foods were enhanced.

Conclusions: After a protein deficit, food intake and food preferences show adaptive changes that suggest that compensatory mechanisms are induced to restore adequate protein status. This indicates that there are human behavioral strategies present to avoid protein shortage and that these involve selection of savory high-protein foods. This trial was registered with the Dutch Trial register at http://www.trialregister.nl as NTR2491.

INTRODUCTION

Protein is an indispensable component within the human diet. It provides the body with nitrogen and amino acids, including the 9 amino acids classified as indispensable that are of crucial importance in preserving and maintaining bodily functions and life (1). Both in animals (2) and in humans (3–5) it has been shown that energy and macronutrient balance are regulated over time, and it has been posed that specifically protein intake is tightly regulated (5–8). Accordingly, animal studies have shown that rodents have several behavioral strategies for regulating the ingestion of indispensable amino acids, including meal termination, altered food choice, foraging for foods that will complement or correct for deficiency, development of learned aversion to a deficient or imbalanced food to avoid that food in the future, and memory for the taste, smell, or place associated with protein-containing foods (9–13). In humans, the range of protein intake has remained relatively constant over time and across populations, both as a percentage of energy in the diet (∼10–25%) and in terms of absolute amount eaten (∼40–100 g), but it is less clear whether behavioral strategies exist to avoid shortages (5–7). Several studies have shown that hungry subjects show a preference for high-protein foods (eg, 14–16), but the causal short-term relation between protein content, food choice, and satiety remains unclear (17), because there are many contradictory findings (eg, 18–20). The objective of this study was to investigate the effect of a low protein status compared with a high protein status on food intake and food preferences.

Our approach consisted of measuring the effect of 2 different diets that varied in protein content (a low-protein diet compared with a high-protein diet). To achieve differences in protein status, the dietary intervention lasted for 14 d. Afterward, ad libitum food intake was measured for 2.5 d.

We hypothesized that when protein status is low, after 14 d of consuming a low-protein diet, food preferences will shift to high-protein foods, resulting in a higher protein intake than after consuming a high-protein diet.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Subjects

Thirty-seven subjects (12 men, 25 women) with a mean (±SD) age of 21 ± 2 y and a mean (±SD) BMI (in kg/m2) of 21.9 ± 1.5 completed the study. Of the 41 participants enrolled in the study, 4 dropped out during the first week (2 from each treatment). A supplemental flow diagram of the progress through the phases of the study is available online (see Supplemental Figure 1 under ‘Supplemental data’ in the online issue). We recruited healthy, normal-weight subjects aged 18–35 y. Exclusion criteria were as follows: restrained eating [Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire: men, score of >2.25; women, score of >2.80 (21)], lack of appetite, an energy-restricted diet during the past 2 mo, change in body weight >5 kg during the past 2 mo, stomach or bowel diseases, diabetes, thyroid disease or any other endocrine disorder, prevalent cardiovascular disease, use of daily medication other than birth control pills, having difficulties with swallowing/eating, hypersensitivity for the foods used in the study, being a vegetarian, and, for women, being pregnant or lactating. Potential participants filled out an inclusion questionnaire including a medical history questionnaire. They then attended a screening session, which included measurement of weight and height. In addition, the procedures were explained and an FFQ4 was filled out. Results of the FFQ showed that the mean (±SD) daily energy intake reported by the subjects was 11.3 ± 3.8 MJ, and protein intake 93 ± 31 g.

Subjects were unaware of the exact aim of the study and were informed that we were investigating the effect of specific diets, which varied in macronutrient content, on food preferences. Subjects were naive to the fact that we specifically varied the protein and carbohydrate content of the diets.

The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of Wageningen University. This trial has been registered with the Dutch Trial register (registration no. NTR2491). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Design

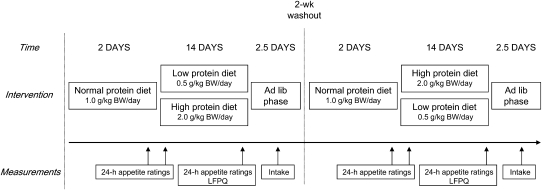

The study consisted of a 14-d fully controlled dietary intervention involving subjects who consumed isoenergetic diets that were either low in protein (containing 0.5 g protein · kg BW−1 · d−1; ∼5% of energy derived from protein) or high in protein (containing 2.0 g protein · kg BW−1 · d−1; ∼21% of energy) in a randomized, crossover design (Figure 1). The amount of protein in the low-protein diet was below the average daily recommendation and was considered to be inadequate (22). Both diets were preceded by 2 d during which subjects ate a normal-protein diet containing 1.0 g protein · kg BW−1 · d−1 (∼11% of energy), which is the average consumption of the Dutch population within this age group (23). These 2 d were used to adapt subjects to the procedure and to ensure energy balance. To assess the effect of protein status on food intake and food preferences, the intervention was followed by an ad libitum phase of 2.5 d during which a large array of food items was available. During the dietary intervention, appetite was assessed during 3 single 24-h periods: on day 2 of the normal-protein diet (baseline rating) and on days 1 and 14 of the low- and high-protein diets. In addition, the LFPQ (24–26) was completed on day 14 of each dietary condition, before the first ad libitum lunch. The 2 dietary conditions were separated by a 2-wk washout period, and during this time subjects were instructed to consume their habitual diet.

FIGURE 1.

Design of the study. Subjects received a normal-protein diet for 2 d. Afterward, they were divided into 2 groups: one group received a low-protein diet for 14 d and one group received a high-protein diet for 14 d. The diets were followed by an ad libitum phase of 2.5 d during which a large array of food items was available, and intake was measured. Appetite was measured during 3 single 24-h periods: on day 2 of the normal-protein diet and on days 1 and 14 of the low- and high-protein diets (24-h appetite ratings). On day 14, the LFPQ was completed. After a 2-wk washout, the intervention was repeated and subjects switched groups. BW, body weight; LFPQ, Leeds Food Preference Questionnaire; lib, libitum.

Protein in the diets was exchanged for carbohydrates, and the amount of fat was kept similar (Table 1). Protein manipulation was achieved by varying commercially available foods in the diets and by changing protein contents within foods (eg, low-protein bread). In addition, whey protein isolate powder (Nectar, pink grapefruit flavor; Syntrax) was added to drinks, desserts, or both, which were consumed during the hot meal to enable the variations in required individual protein amounts.

TABLE 1.

Nutritional composition (energy content and macronutrient composition) of the daily low- and high-protein diets for a participant with an energy intake of 11 MJ/d and a body weight of 68 kg1

| Low-protein diet | High-protein diet | |

| Energy (MJ) | 10.7 | 11.4 |

| Protein (g/kg body weight) | 0.5 | 1.9 |

| Protein [g (% of energy)] | 31 (5) | 127 (19) |

| Carbohydrates [g (% of energy)] | 353 (56) | 303 (45) |

| Fat [g (% of energy)] | 108 (37) | 106 (34) |

| Alcohol [g (% of energy)] | 5 (1) | 6 (2) |

| Fiber (g) | 30 | 31 |

Duplicate portions of the provided diets were collected every day for an imaginary participant, stored at −20°C, and analyzed for energy and macronutrient composition after the experiment. Nitrogen was determined by the Kjeldahl method (27; method 920.87), and the amount of protein was calculated by using a conversion factor of 6.25. Fat was determined by the acid hydrolysis method (27; method 14.019), and available carbohydrate was calculated by subtracting moisture, ash, protein, dietary fiber, and fat from total weight. Energy content was calculated from the macronutrient composition by using the following energy conversion factors: protein, 17 kJ/g; fat, 37 kJ/g; carbohydrate, 17 kJ/g; alcohol, 29 kJ/g. The average of the calculated composition of the free-choice items (10%), which were recorded in a diary by all participants (n = 37), was added.

Procedure

During the dietary intervention, we provided the subjects with foods and beverages, except for water, coffee, and tea (ad libitum intake without milk and sugar), which covered ∼90% of their estimated daily energy requirement. Subjects chose the remaining 10% of energy from a list of items that included virtually protein-free and fat-free foods (common procedure within our division with regard to long-term controlled dietary intervention studies, see reference 28). Their choice was recorded in a diary. Each subject's total energy requirement was estimated by using the results of the FFQ, which was filled out during screening, and by means of the Schofield equation, taking into account age, weight, height, sex, and a physical activity level of 1.6 (29).

During weekdays at lunch, the participants visited the division and consumed their hot meals. All other foods were supplied daily as a meal package and consumed at home. The home meal package contained 2 bread meals with toppings for dinner and breakfast and beverages, fruits, and snacks. On Fridays, subjects received a home meal package with foods and beverages for the entire weekend plus instructions for the preparation of these foods. Subjects were instructed to eat all of the foods that were provided. They were allowed to use seasoning and table salt. During weekdays, palatability of the hot meals was rated by using a 10-point Likert scale (mean ± SD results: low-protein diet, 8 ± 2; high-protein diet, 7 ± 2). Palatability of the home meal packages was measured 3 times for both dietary conditions (day 1, day 8, day 14; mean ± SD results: low-protein diet, 7 ± 1; high-protein diet, 8 ± 1).

The ad libitum phase of 2.5 d that followed the dietary intervention started with a hot lunch; participants could select foods themselves and eat until comfortably satiated. Large meal packages were provided for consumption at home and contained ≥200% of the estimated energy requirements. The home meal packages consisted of foods that were not available during the intervention and included buns with toppings for dinner and breakfast and beverages, fruits, and snacks. The foods were provided in unusual portion sizes to prevent habitual intake. In addition, many foods were offered in both a low- and high-protein version to enable selective protein intake (Table 2). In total, the ad libitum phase comprised 3 lunches and 2 home meal packages. Individual food intake was measured by weighing the remainder of food on the plate (during lunch) and the home meal packages the next day. Ad libitum energy intake and macronutrient selection were calculated by using Dutch food composition tables (30).

TABLE 2.

Mean total intake of foods and beverages during the 2.5-d ad libitum phase (n = 37)

| Foods | After low-protein diet |

After high-protein diet |

Difference in intake1 | ||

| Lunch items | kJ | g2 | kJ | g2 | % |

| Neutral taste | 2667 ± 9723 | 1010 | 2679 ± 1090 | 1029 | 0 |

| Starch, 2 kinds | 1874 ± 864 | 425 | 1777 ± 735 | 399 | 5 |

| Vegetables, 2 kinds | 645 ± 291 | 500 | 709 ± 424 | 521 | −9 |

| Salad and dressing | 148 ± 169 | 85 | 193 ± 205 | 109 | −24 |

| Savory taste | 4050 ± 1497 | 600 | 3728 ± 1917 | 555 | 9 |

| Sauce, 2 kinds | 1682 ± 944 | 302 | 1588 ± 1095 | 286 | 6 |

| Meat, high-protein version | 1248 ± 655 | 161 | 948 ± 829 | 119 | 32 |

| Meat, low-protein version | 1120 ± 762 | 136 | 1192 ± 802 | 151 | −6 |

| Sweet taste | 3835 ± 1769 | 534 | 4181 ± 1746 | 558 | −8 |

| Dessert, high-protein version | 385 ± 581 | 108 | 254 ± 528 | 73 | 51 |

| Dessert, low-protein version | 3450 ± 1642 | 427 | 3926 ± 1789 | 485 | −12 |

| Home package items | |||||

| Neutral taste | 5105 ± 1620 | 421 | 4736 ± 1635 | 401 | 8 |

| Buns | 3829 ± 1448 | 378 | 3709 ± 1498 | 366 | 3 |

| Margarine | 1276 ± 683 | 43 | 1028 ± 775 | 35 | 24 |

| Savory taste, high protein | 2791 ± 1677 | 203 | 2087 ± 1156 | 149 | 344 |

| Egg | 548 ± 417 | 89 | 382 ± 365 | 62 | 44 |

| Sandwich fillings | 1175 ± 1042 | 68 | 825 ± 779 | 49 | 42 |

| Snacks | 1068 ± 1150 | 46 | 880 ± 994 | 38 | 21 |

| Savory taste, low protein | 2256 ± 1281 | 158 | 2200 ± 1210 | 155 | 3 |

| Sandwich fillings | 569 ± 477 | 82 | 558 ± 479 | 81 | 2 |

| Snack | 1687 ± 1204 | 75 | 1643 ± 1183 | 73 | 3 |

| Sweet taste, high protein | 6329 ± 2908 | 1018 | 6237 ± 2621 | 949 | 1 |

| Sandwich fillings | 1114 ± 906 | 59 | 1365 ± 1158 | 71 | −18 |

| Snack | 791 ± 977 | 37 | 622 ± 722 | 29 | 27 |

| Cookie | 1660 ± 1740 | 94 | 1772 ± 1565 | 101 | −6 |

| Fruit drinks | 2763 ± 1452 | 828 | 2478 ± 1368 | 748 | 11 |

| Sweet taste, low protein | 5659 ± 2197 | 1610 | 6039 ± 2406 | 1713 | -6 |

| Sandwich fillings | 221 ± 490 | 22 | 181 ± 220 | 18 | 22 |

| Sweet snack | 1696 ± 1159 | 83 | 1852 ± 1146 | 91 | −8 |

| Cookie | 746 ± 719 | 58 | 816 ± 763 | 63 | −9 |

| Fruit drinks | 1865 ± 853 | 997 | 1837 ± 983 | 982 | 2 |

| Fruit | 1131 ± 696 | 451 | 1354 ± 830 | 559 | −16 |

Intake (kJ) after the low-protein diet divided by intake after the high-protein diet, multiplied by 100%, minus 100%.

Values are means.

Mean ± SD (all such values).

P < 0.01 (paired t test).

Measurements

During the dietary intervention, appetite was assessed during 3 single 24-h periods: on day 2 of the normal-protein diet (baseline rating) and on days 1 and 14 of the low- and high-protein diets. Each subject completed an appetite questionnaire hourly during waking hours over the 24-h period by using a Personal Digital Assistant (HP iPAQ with EyeQuestion version 3.8.3 software; Logic8 B.V.) starting after lunch from 1400 until 1200 the next day. The questionnaire consisted of 7 dimensions: hunger, fullness, prospective consumption, desire to eat, appetite for something sweet, appetite for something savory, and thirst. The 10-point Likert scale was anchored with “not at all” to “extremely.”

The LFPQ was completed on day 14 of each dietary condition, before the first ad libitum lunch. The LFPQ is a computerized hedonic analysis platform that measures explicit and implicit components of food reward and included photographs of 16 foods varying in 2 dimensions: protein (low and high) and taste (sweet and savory). These 4 categories were matched on energy density, fat content, and type of food (each category contained one sandwich, one snack, one cookie, and one meal item). For explicit measures, each food was shown and subjects had to rate their liking (“How pleasant would you find the taste of this food right now?”) and their wanting (“How much do you want to eat this food right now?”) on a visual analog scale (100 mm). In addition, foods were presented in randomized pairs, and subjects had to select their most wanted food (“select the food that you most want to eat right now”) as quickly and accurately as possible. During the latter procedure, both frequency of preferred choice (relative food preference) and reaction time were measured. Because participants were not informed about the measurement of their reaction time for each choice and were unable to monitor their responses, this measure provided a nonverbal, implicit assay of their motivation (implicit wanting). Reaction times were transformed to a standardized d score by using a validated algorithm (31): the smaller the d score, the greater the implicit wanting for that food category relative to other categories in the task.

BW, urine nitrogen excretion, and analytic methods

BW was measured twice a week before subjects ate their hot meal while subjects were wearing no shoes or heavy clothing. If a subject's weight fluctuated >0.2 kg from baseline, the research dietitian decided whether energy intake needed to be adjusted for weight maintenance.

As an independent, objective marker of dietary compliance, total urine nitrogen excretion was measured from two 24-h urine collections made during day 14 of each dietary condition. Results showed that total urine nitrogen excretion decreased with low dietary protein intake (low-protein diet: 84 ± 17 mg · kg BW−1 · d−1; high-protein diet: 248 ± 38 mg · kg BW−1 · d−1). These data confirm that the low-protein diet was inadequate and contained protein amounts below the average daily recommendation (equivalent to 105 mg nitrogen · kg BW−1 · d−1) (22). Completeness of the two 24-h urine samples was verified by recovery of three 80-mg doses of paraaminobenzoic acid given with the meals (32). Analyses showed an average recovery rate of 96.5%. Nitrogen in urine was determined colorimetrically according to the Kjeldahl method (27) (method 920.87) on a Vitros 250 Chemistry System (Ortho-clinical Diagnostics).

Although we relied primarily on the total nitrogen excretion data as an independent, objective marker of dietary compliance, we also used other means to promote compliance. These included instructing participants to keep a diary to record any deviations from the diet, illness, and use of drugs. Subjects were urged not to change their smoking habits and their physical activities. The latter was also monitored by assessing the number of steps taken each weekday with pedometers (Yamax Digi-walker SW-200).

Statistical analyses

Comparisons of appetite ratings between the low- and high-protein diet were made by calculating the AUC for all ratings (trapezoidal method), and these were compared by means of ANOVA (mixed-model procedure). Because baseline ratings did not differ between the 2 diets, these were not incorporated in the analyses.

Intakes during the ad libitum phase were compared by means of ANOVA (mixed-model procedure). Analyses were performed on protein intake (g) and total intake (MJ) for the total 2.5 d, and separate analyses were performed with days (3 d), lunches (3 lunches), and home meal packages (2 packages) as factors in the model. Intake of the different food categories were compared by means of a paired t test. The results of the LFPQ were analyzed by using ANOVA (General Linear Model procedure).

In all analyses, both main effects and interactions were analyzed. In addition, participants were included in all models as random factors. Post hoc comparisons were made by using Tukey's correction. Analyses were conducted by using SAS, version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc). Data are presented as means ± SDs unless otherwise specified.

RESULTS

Appetite ratings during the low- and high-protein diets

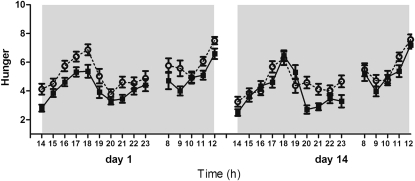

During the low-protein diet, subjects reported significantly more hunger than during the high-protein diet (P < 0.0001) on both days 1 and 14 (Figure 2); the magnitude of this difference did not change (diet × day interaction: P = 0.52). These results were similar for fullness (P < 0.001), prospective consumption (P < 0.0001), desire to eat (P < 0.0001), and appetite for something savory (P < 0.0001). On day 1 during the low-protein diet, subjects experienced more appetite for something sweet than during the high-protein diet (P < 0.05). On day 14, however, the difference was no longer evident (P = 0.85). The diets had no differential effects on ratings of thirst.

FIGURE 2.

Mean (±SEM) hourly rated feelings of hunger during waking hours from 1400 until 1200 the next day on days 1 and 14 during the low-protein diet (○) and the high-protein diet (•) assessed on a 10-point Likert scale. Subjects reported more hunger during the low-protein diet than during the high-protein diet on both days (P < 0.0001). The magnitude of this difference did not change (diet × day interaction: P = 0.52). Analyses were performed on AUCs by means of ANOVA (mixed-model procedure).

Intake during the ad libitum phase after the low- and high-protein diets

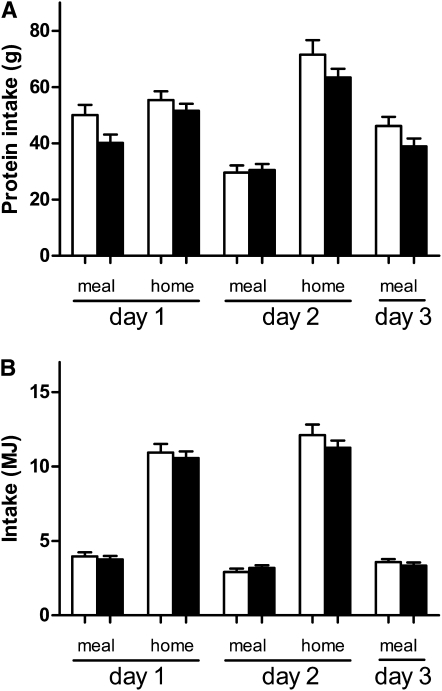

Total protein intake (g) during the ad libitum phase was 13% higher after the low-protein diet (253 ± 70 g) than after the high-protein diet (225 ± 63 g) (P < 0.001). This difference in protein intake was evident on all 3 days (P < 0.01): day 1, 105 ± 30 g (1.6 g · kg BW−1 · d−1) compared with 92 ± 25 g (1.4 g · kg BW−1 · d−1); day 2, 101 ± 41 g (1.5 g · kg BW−1 · d−1) compared with 94 ± 28 g (1.4 g · kg BW−1 · d−1); day 3, 46 ± 20 compared with 39 ± 17 g; and was evident both during the hot lunches (P < 0.01) and during consumption at home (P < 0.05) (Figure 3A). The proportion of energy derived from protein during the ad libitum phase was also significantly higher after the low-protein diet (12.9%) than after the high-protein diet (11.8%) (P < 0.001). The proportions of energy derived from carbohydrates and fat after the low- and high-protein diets, respectively, were 52.1% compared with 54.0% (P < 0.01) and 34.1% compared with 32.8% (P < 0.05).

FIGURE 3.

A: Total protein intake (g) of the lunch meals and of the home meal packages during the 3 d in the ad libitum phase after the low-protein diet (open bars) and high-protein diet (solid bars). Total protein intake (g) was higher after the low-protein diet than after the high-protein diet (P < 0.001). B: Total intake (MJ) of the lunch meals and home packages during the 3 d in the ad libitum phase after the low-protein diet (open bars) and after the high-protein diet (solid bars). Total energy intake (MJ) did not differ after the low-protein diet compared with after the high-protein diet (P = 0.14). Values are means ± SEMs (n = 37). The intake of protein (g) and energy (MJ) were compared by means of ANOVA (mixed-model procedure). home, home meal packages; meal, hot lunch meals.

Total energy intake (MJ) during the ad libitum phase after the low-protein diet (33.5 ± 9.3 MJ) did not differ from the intake after the high-protein diet (32.1 ± 7.0 MJ) (P = 0.20). On all 3 d and both during consumption of the hot lunches (P = 0.68) and during consumption at home (P = 0.12), there were no differences (Figure 3B) (day 1, 14.9 ± 4.3 compared with 14.3 ± 3.5 MJ; day 2, 15.0 ± 5.2 compared with 14.4 ± 3.3 MJ; day 3, 3.6 ± 1.2 compared with 3.3 ± 1.6 MJ; P = 0.20).

With comparison of the intake of foods during the ad libitum phase according to sensory and protein composition (ie, high- or low-protein foods with neutral, savory, or sweet taste), it was shown that subjects selectively consumed certain foods in response to the dietary intervention (Table 2). Specifically, after the low-protein diet, subjects had a higher intake of savory high-protein foods than after the high-protein diet (P < 0.01).

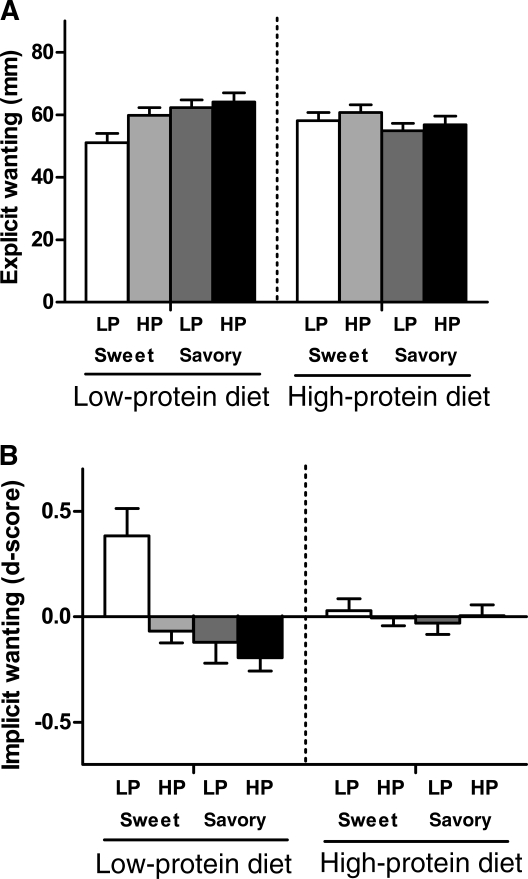

Results of the LFPQ after the low- and high-protein diets

The results from the LFPQ showed that the dietary condition significantly altered preference for foods according to their taste properties; after the low-protein diet, there was an enhanced preference for the savory foods compared with the sweet foods. No such preference was seen after the high-protein diet. This finding was observed in all 4 outputs: explicit liking, P < 0.0001; explicit wanting, P < 0.001 (Figure 4A); relative food preference, P < 0.01; implicit wanting, P < 0.05 (Figure 4B). In terms of effects on food preference according to the protein composition of the images, the dietary condition significantly interacted with implicit wanting according to the protein content of the foods. After the low-protein diet, greater implicit wanting was observed for high-protein foods than for low-protein foods (P < 0.05). No such preference was seen after the high-protein diet. This specific interaction was not evident in the other outputs (explicit liking, P = 0.20; explicit wanting, P = 0.31; relative food preference, P = 0.42).

FIGURE 4.

A: Explicit wanting for the LP and HP sweet and savory products after the LP and HP diets assessed on a visual analog scale (100 mm). After the LP diet, there was greater explicit wanting for savory foods than for sweet foods (P < 0.001). No preference was evident after the HP diet. Also, no preference was evident for HP or LP products after either of the diets. B: Implicit wanting for the LP and HP sweet and savory products after the LP and HP diets expressed as a standardized d score, which is a validated algorithm to transform reaction time (24). A smaller d score means a greater implicit wanting for that food category relative to other categories in the task. After the LP diet, there was a greater implicit wanting for savory foods than for sweet foods (P < 0.05) and a greater implicit wanting for HP foods than for LP foods (P < 0.05). No preference was evident after the HP diet. Values are means ± SEMs (n = 37). Results of the Leeds Food Preference Questionnaire were analyzed by using ANOVA (General Linear Model procedure). HP, high-protein; LP, low-protein.

DISCUSSION

This study investigated the effect of a low protein status compared with a high protein status on food intake and food preferences. The present results show that there was a spontaneous 13% higher intake of protein after a low-protein diet than after a high-protein diet, whereas total energy intake was not different. In addition, after a low-protein diet, preferences for savory high-protein food were enhanced. These results indicate that after a protein deficit, food intake and food preferences change to restore adequate protein status.

In animal studies it has long been determined that protein balance is achieved by behavioral strategies (9–13), whereas in humans it is less clear whether behavioral strategies exist to avoid protein shortages (5–7). Several studies have shown that hungry subjects show a preference for high-protein foods (eg, references 14–16). However, the role of the sensory qualities in the influence of protein on food intake and food choice requires further clarification. Within our food range, foods containing high amounts of protein are in general more savory tasting, whereas foods containing carbohydrates are generally sweeter (33) [“savory taste” refers to nonsweet taste, closely linked to the “umami taste,” which is also described as “broth-like” or “meaty” (34)]. Through consumption of foods during our lifetime we learn to estimate their satiating effects (35, 36), and it has been suggested that this plays a central role in the development of specific macronutrient appetites (37, 38). The intake of different foods observed during the ad libitum phase of our study indicates that sensory attributes play a role in selecting food for macronutrient balance. Indeed, after the low-protein diet, food choice was directed toward savory high-protein foods in comparison with after the high-protein diet. These findings were reinforced by the results of the LFPQ, which showed that after the low-protein diet, food preferences were enhanced and oriented toward savory foods, whereas after the high-protein diet preferences remained stable.

As shown in our data, the preference for high-protein foods was still present after 3 d (Figure 3). It appears, therefore, that protein appetite induced through 2 wk of selective reduction of dietary protein is not extinguished after 3 d of ad libitum intake. It might be that a longer period of time is needed to recover from the protein shortage that has been imposed. More research is needed to quantify the time needed for an organism to regain macronutrient balance.

To be able to create a large difference in protein amounts between the 2 diets, some compromises were made with regard to the control for the sensory differences between the diets. To obtain more insight, we calculated a taste ratio of the low- and high-protein diets by classifying the offered foods as sweet tasting, savory tasting, or neutral tasting. Subsequently, the total amount of food (g) per taste was divided by the total amount of food (g) provided by the diet. The ratio of sweet:savory:neutral for the low-protein diet was 53:9:39 and for the high-protein diet was 54:15:31, indicating that the low-protein diet contained slightly fewer savory-tasting foods and more neutral-tasting foods. This might have affected the choice behavior during the ad libitum phase, because long-term sensory-specific satiety has been shown to affect food choice and intake (39). The intake of the different foods during the ad libitum phase, however, indicates that after the low-protein diet a specific selection for high-protein foods was present, and not just for savory foods in general (see Table 2). Because we offered foods during the ad libitum phase that were not offered during the intervention, we believe that this specific selection for savory high-protein foods is a result of compensatory mechanisms that are induced to restore adequate protein status. In future research, however, it would be preferable during the preparation phase of such a study to perform sensory tests on the foods that are included. This would enable a more specific characterization of the diets on a sensory level, facilitating an even better match.

The results from the LFPQ indicated that the changes in food preferences appear to involve both conscious (explicit) and subconscious (implicit) processes. It is recognized that both explicit and implicit processes are involved in human eating behavior (eg, references 40 and 41); the degree to which implicit processes are involved, however, is not clear. The results of the present study suggest that the role of implicit motivational processes in driving food choice is not static, but can vary. When the human body is in balance (eg, macronutrient balance), it appears that explicit and implicit hedonic responses to foods are similar (eg, after the high-protein diet, explicit and implicit outcomes showed similar results). However, when homeostasis is challenged (eg, prolonged macronutrient imbalance), implicit processes appear to play a stronger determining role in decisions about what to eat (eg, after the low-protein diet, subjects implicitly, but not explicitly, preferred high-protein foods). Results from intake in the ad libitum phase showed that subjects indeed ingested selectively more high-protein foods, even among savory foods. These data advocate the use of these kinds of advanced psychological tools in behavioral food research to help identify underlying mechanisms involved in human eating behavior.

In conclusion, after a protein deficit, food intake and food preferences show adaptive changes that suggest compensatory mechanisms that are induced to restore adequate protein status. Hence, it appears that human protein intake can be controlled in a very specific manner when allowed by the composition of the food available. This indicates that there are human behavioral strategies present to avoid protein shortage and that these involve selection of savory high-protein foods, made either consciously or unconsciously.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Wieke Altorf-van der Kuil, Karin Borgonjen, Anita Bruggink-Hoopman, Ingrid Heemels, Eva Hebing, Dorthe Klein, Inge van Rijn, Nika Schnek, Evren Sener, Elles Steggink, Betty van der Struijs, and Merel van Veen for their help in carrying out the study. We thank Frans J Kok, Gerry Jager, and Michael Müller for helpful comments on the manuscript.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—SG-R, MM, DT, and CdG: design of the study, SG-R and ES: collection of data; SG-R: analysis of the data and writing of the manuscript; and all authors: interpretation of the data and critical revision of the manuscript. None of the authors had a personal or financial conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: BW, body weight; FFQ, food-frequency questionnaire; LFPQ, Leeds Food Preference Questionnaire.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tome D. Protein, amino acids and the control of food intake. Br J Nutr 2004;92:S27–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bensaïd A, Tomé D, Gietzen D, Even P, Morens C, Gausseres N, Fromentin G. Protein is more potent than carbohydrate for reducing appetite in rats. Physiol Behav 2002;75:577–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apolzan JW, Carnell NS, Mattes RD, Campbell WW. Inadequate dietary protein increases hunger and desire to eat in younger and older men. J Nutr 2007;137:1478–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Castro JM. Prior day's intake has macronutrient-specific delayed negative feedback effects on the spontaneous food intake of free-living humans. J Nutr 1998;128:61–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simpson SJ, Raubenheimer D. Obesity: the protein leverage hypothesis. Obes Rev 2005;6:133–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metcalf PA, Scragg RRK, Schaaf D, Dyall L, Black PN, Jackson R. Dietary intakes of European, Māori, Pacific and Asian adults living in Auckland: the Diabetes, Heart and Health Study. Aust N Z J Public Health 2008;32:454–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simpson SJ, Batley R, Raubenheimer D. Geometric analysis of macronutrient intake in humans: the power of protein? Appetite 2003;41:123–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Long SJ, Jeffcoat AR, Millward DJ. Effect of habitual dietary-protein intake on appetite and satiety. Appetite 2000;35:79–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Booth DA, Simson PC. Food preferences acquired by association with variations in amino acid nutrition. Q J Exp Psychol 1971;23:135–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Booth DA. Food intake compensation for increase or decrease in the protein content of the diet. Behav Biol 1974;12:31–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibson EL, Booth DA. Acquired protein appetite in rats: dependence on a protein-specific need state. Experientia 1986;42:1003–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simpson SJ, White PR. Associative learning and locust feeding: evidence for a `learned hunger’ for protein. Anim Behav 1990;40:506–13 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gietzen DW, Hao S, Anthony TG. Mechanisms of Food Intake Repression in Indispensable Amino Acid Deficiency. Annu Rev Nutr 2007;27:63–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barkeling B, Rossner S, Bjorvell H. Effect of a high-protein meal (meat) and a high-carbohydrate meal (vegetarian) on satiety measured by automated computerized monitoring of subsequent food intake, motivation to eat and food preferences. Int J Obes (Lond) 1990;14:743–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill AJ, Blundell JE. Macronutrient and Satiety: The effects of a high-protein or high-carbohydrate meal on subjective motivation to eat and food preferences. Nutr Behav 1986;3:133–44 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vazquez M, Pearson PB, Beauchamp GK. Flavor preferences in malnourished mexican infants. Physiol Behav 1982;28:513–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA) Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to protein and increase in satiety leading to a reduction in energy intake (ID 414, 616, 730), contribution to the maintenance or achievement of a normal body weight (ID 414, 616, 730), maintenance of normal bone (ID 416) and growth or maintenance of muscle mass (ID 415, 417, 593, 594, 595, 715) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006. EFSA J 2010;8:1811 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blatt AD, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. Increasing the protein content of meals and its effect on daily energy intake. J Am Diet Assoc 2011;111:290–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Graaf C, Hulshof T, Weststrate JA, Jas P. Short-term effects of different amounts of protein, fats, and carbohydrates on satiety. Am J Clin Nutr 1992;55:33–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halton TL, Hu FB. The effects of high protein diets on thermogenesis, satiety and weight loss: a critical review. J Am Coll Nutr 2004;23:373–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Strien T. Nederlandse Vragenlijst voor eetgedrag Handleiding. [Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire manual.]. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Boom Test Publishers, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 22.WHO Protein and amino acid requirements in human nutrition. Report of a Joint WHO/FAO/UNU Expert Consultation. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hulshof K, Ocké M, Van Rossum C, Buurma-Rethans E, Brants H, Drijvers J. Results of the National Food Consumption Survey 2003. Bilthoven, Netherlands: RIVM (National Institute for Public Health and the Environment), 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finlayson G, King N, Blundell JE. Is it possible to dissociate ‘liking’ and ‘wanting’ for foods in humans? A novel experimental procedure. Physiol Behav 2007;90:36–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griffioen-Roose S, Finlayson G, Mars M, Blundell JE, de Graaf C. Measuring food reward and the transfer effect of sensory specific satiety. Appetite 2010;55:648–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffioen-Roose S, Mars M, Finlayson G, Blundell JE, de Graaf C. The effect of within-meal protein content and taste on subsequent food choice and satiety. Br J Nutr 2011;106:779–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Association of Official Analytical Chemists International Official methods of analysis of AOAC International. 16th ed Gaithersburg, MD: Association of Official Analytical Chemists International, 1997, revised 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siebelink E, Geelen A, de Vries JHM. Self-reported energy intake by FFQ compared with actual energy intake to maintain body weight in 516 adults. Br J Nutr 2011;106:274–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.WHO Principles for the estimation of energy requirements. Energy and protein requirements. Report of a Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation. 2nd ed Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1985:34–52 [Google Scholar]

- 30.NEVO Tabel. Dutch Nutrient Database 2006. Den Haag, Netherlands: Voedingscentrum, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greenwald AG, Nosek BA, Banaji MR. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. J Pers Soc Psychol 2003;85:197–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bingham S, Cummings JH. The use of 4-aminobenzoic acid as a marker to validate the completeness of 24 h urine collections in man. Clin Sci (Lond) 1983;64:629–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luscombe-Marsh ND, Smeets AJPG, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Taste sensitivity for monosodium glutamate and an increased liking of dietary protein. Br J Nutr 2008;99:904–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamaguchi S, Ninomiya K. Umami and food palatability. J Nutr 2000;130:921S–6S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Booth DA. Conditioned satiety in the rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol 1972;81:457–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Booth DA. Food-conditioned eating preferences and aversions with interoceptive elements—conditioned appetites and satieties. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1985;443:22–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baker BJ, Booth DA, Duggan JP, Gibson EL. Protein appetite demonstrated: Learned specificity of protein-cue preference to protein need in adult rats. Nutr Res 1987;7:481–7 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gibson EL, Wainwright CJ, Booth DA. Disguised protein in lunch after low-protein breakfast conditions food-flavor preferences dependent on recent lack of protein intake. Physiol Behav 1995;58:363–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rolls BJ, Rolls ET, Rowe EA, Sweeney K. Sensory specific satiety in man. Physiol Behav 1981;27:137–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berridge KC, Robinson TE, Aldridge JW. Dissecting components of reward: `liking’, `wanting’, and learning. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2009;9:65–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prestwich A, Hurling R, Baker S. Implicit shopping: attitudinal determinants of the purchasing of healthy and unhealthy foods. Psychol Health 2011;26:875–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.