Abstract

Thrombotic microangiopathies (TMAs) represent a heterogeneous group of diseases characterized by a microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, peripheral thrombocytopenia, and organ failure of variable severity. TMAs encompass thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), typically characterized by fever, central nervous system manifestations and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), in which renal failure is the prominent abnormality. In patients with cancer TMAs may be related to various antineoplastic drugs or to the malignant disease itself. The reported series of patients with TMAs directly related to cancer are usually heterogeneous, retrospective, and encompass patients with hematologic malignancies with solid tumors or receiving chemotherapy, each of which may have distinct presentations and pathophysiological mechanisms. Patients with disseminated malignancy who present with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia may be misdiagnosed as thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) Only a few cases of TTP secondary to metastatic adenocarcinoma are known in the literature. We present a case of a 34-year-old man with TTP syndrome secondary to metastatic small-bowel adenocarcinoma. Patients with disseminated malignancy had a longer duration of symptoms, more frequent presence of respiratory symptoms, higher lactate dehydrogenase levels, and more often failed to respond to plasma exchange treatment. A search for systemic malignancy, including a bone marrow biopsy, is appropriate when patients with TTP have atypical clinical features or fail to respond to plasma exchange.

Key words: metastatic cancer, microangiopathic hemolysis, thrombocytopenia, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, ADAMTS13.

Introduction

The initial diagnosis of thrombotic thrombo-cytopenic purpura (TTP) may be uncertain because other disorders that can cause microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia, the principal diagnostic criteria, may not be initially apparent.1 Disseminated malignancy is an important consideration in the differential diagnosis of TTP since cancer has been well described for many years as a cause of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia.2–7 Although in most patients the disseminated malignancy that causes microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia is easily recognized, in some patients, the malignancy is not clinically apparent, and therefore TTP is diagnosed and plasma exchange treatment is begun. Failure to diagnose disseminated malignancy exposes the patient to the major risks of plasma exchange and causes delay of appropriate chemotherapy.8 However, failure to urgently initiate plasma exchange treatment in a patient with TTP may result in death. The thrombotic microangiopathies are a group of syndromes characterized by small-vessel thrombosis, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia and organ failure. The most common of these disorder, hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) and TTP, were once considered 2 distinct disease etiologies. In consideration of their extensive pathophysiologic overlap, they are now termed the HUS/TTP syndrome. The classic clinical pentad of TTP includes i) fever, ii) neurologic symptoms, iii) microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, iv) thrombocytopenic purpura, and v) the presence of thrombi in glomerular capillaries and afferent arterioles. Although hemolytic anemia is a universal feature, all 5 classic findings are present in only 40% of cases. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura is seen more often in women, with most of the patients younger than 40 years, the diagnosis rests on evidence of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia in the absence of DIC or other known causes of thrombotic microangiopathy. There are no clinical features or laboratory tests that can confirm the diagnosis of TTP-HUS; the most important diagnostic criterion, but also the most difficult, is the exclusion of alternative etiologies.9,10 ADAMTS13 (A Disintegrin And Metallo-protease with ThromboSpondin-1-like domains), an enzyme required for normal proteolytic processing of von Willebrand factor (VWF), is important in the pathophysiology of TTP, but patients may have characteristic presenting features and clinical courses without severe ADAMTS13 deficiency.11,12 Even after a diagnosis of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura is made, continuing evaluation is important. In the Oklahoma Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura-Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (TTP-HUS) Registry, 10 percent of patients with an initial diagnosis of idiopathic thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura were subsequently found to have sepsis or systemic cancer (Table 1).

Table 1. Clinical features that may suggest disseminated malignancy as an alternative diagnosis in patients with assumed TTP-HUS.

| Clinical feature | Comment |

|---|---|

| History of cancer | Even when the clinical evaluation and results of imaging studies are normal metastatic cancer must be suspected |

| Pulmonary infiltrates | Rare in TTP-HUS |

| Respiratory failure | Acute respiratory symptoms are rare in TTP-HUS. |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) | Although DIC is commonly associated with metastatic carcinoma, coagulation tests may be normal. |

| Nucleated red blood cells and immature Myeloid cells on peripheral blood smear | These abnormalities may accompany the marrow response to severe hemolysis, but they commonly indicate marrow infiltration by tumor. |

| Extreme elevation of lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) level | Although an elevated LDH level, caused by hemolysis and tissue ischemia, is characteristic of TTP-HUS, levels exceeding 5,000 U/L are more commonly cause by tumor lysis |

| No response to plasma exchange therapy | Patients with TTP-HUS typically respond promptly to plasma exchange. No response should cause concern about the diagnosis. |

| Extreme elevations of D-dimer | D-dimers were found severely increased in all cases of disseminated cancer presenting as TTP |

| ADAMTS13 activity | ADAMTS13 activity may be normal or lower than normal in cancer-associated TTP. |

Case Report

A 34-yer-old man without significant past medical history was found lethargic in bed early morning and sudden onset of respiratory failure. The patient was on no medications and had no drug allergies. He did not smoke or use drugs. There was no family history of major medical problems. The patient was transferred to the emergency department (ED) by ambulance. Upon arrival at the ED his consciousness level was rated on the Glasgow Coma Scale as 6/15, (E2V1M3), he was somnolent and unable to follow commands. His mental status worsened, and the trachea was intubated for airway protection with use of rapid-sequence induction. Physical examination revealed an obese white male in acute distress. His vital signs were: temperature, 38,5°C; pulse, 125 beats/min; respirations, 24 breaths/min; and blood pressure 90/50 mmHg. Head examination found no signs of trauma. Pupils were equal and reactive to light. The neck examination revealed jugular and supraclavicular lymphadenopathies with a firm and rubbery consistency. The abdomen was soft and tender with a 3 cm hepatomegaly. Tachypnea and use of accessory muscles were present. Cardiac examination revealed tachycardia but regular rhythm without murmurs, rubs, or gallops. The skin was mottled, without petechiae; the extremities were cool and clammy, with acral cyanosis. The patient was sedated and mechanically ventilated with an inspiratory oxygen concentration of 60 percent. Results of laboratory tests on admission were as follows; leukocyte, 6400/mL; hematocrit, 23.6%, hemoglobin, 7.7 g/dL; peripheral smear showed moderate-to-severe schistocytosis and marked red cell fragmentation ; platelet 60,000/mL, serum glucose 123 mg/dL, serum urea 86 mg/dL, serum creatinine 2.86 mg/dL , serum sodium 139 mg/dL, serum potassium 6.2 mg/dL, total bilirubin 6.8 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase, 5318 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 1947 U/L, lactate dehydrogenase 19,758 U/L. Blood coagulation tests; prothrombin time, 23,1 sec, activated partial thromboplastin time 53.2 sec. ; Fibrinogen 3.9 g/L (2.0–6.0) all within normal values; D-dimer 5250 ng/dL. A Coomb’s tests showed a negative result. Toxicologic screening of serum was negative for ethanol, acetaminophen, and salicylates, and toxicologic screening of urine was also negative. Blood cultures failed to grow any organism. Antibody titer for human immunod-eficiency virus was normal. A chest radiograph was normal, and a bedside echocardiogram showed no pericardial fluid. Specimens of blood and urine were taken for bacterial and viral cultures and testing for viral antigens. Toraco-abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed enlarged esophageal and paracardiac lymph nodes, bilateral posterobasal lung consolidations, hepatosplenomegaly, multiple enlarged retroperitoneal and paraaortic lymph nodes (Figure 1).

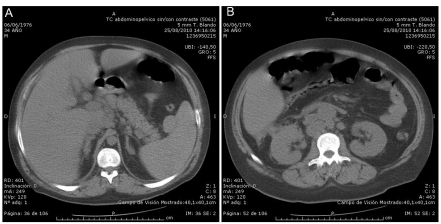

Figure 1.

Abdominal CT scan demonstrates A) pathological hepatic lymph nodes and B) retroperitoneal lymph nodes.

A definite diagnosis could not be determined on admission because of the complexity of signs and symptoms, the diagnosis of TTP was suggested based on the presence of fever, neurologic symptoms, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, renal failure, increased serum levels of lactate dehydrogenase and indirect-reacting bilirubin, and negative direct Coomb’s test. Plasma exchange therapy and supportive care was begun. It was critical to rule out disseminated cancer. The importance of prompt diagnosis of the systemic malignancy was to provide an opportunity for treatment with appropriate chemotherapy. In the Intensive Care Unit treatment with dopamine to maintain a systolic blood pressure of 140 was started, and aggressive fluid resuscitation was continued. Two hours later the blood pressure decreased to 90/45 mm Hg; Norepinephrine was added. After obtaining informed consent from his family bone marrow aspiration sample was obtained. Twenty-nine hours after presentation the axillary temperature was 40.4°C (104.8°F) and the blood pressure 82/55 mm Hg despite increasing doses of dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine. Laboratory evaluation demonstrated severe anemia (hematocrit 23%) despite blood transfusion, thrombocytopenia (platelet count 20,000/mL), coagulation tests (internationalized normalized ratio (INR), 1.2; activated partial prothrombin time, 25 s; fibrinogen concentration, 3.3 g/L (2.0–6.0) were normal. Results of Microbiologic and Serologic Tests were received, Blood culture negative, Urine culture negative, Cytomegalovirus antigenemia assay negative, Epstein-Barr virus anti-VCA IgG postive, Epstein-Barr virus anti-VCA IgM negative, Epstein-Barr virus early antigen negative, Epstein–Barr virus antinuclear antigen negative, Herpes simplex virus type 1 antibody IgG positive, Herpes simplex virus type 2 antibody IgG negative, Carcinoembryonic antigen (ng/mL) 1.4, Prostate-specific antigen (ng/mL) 4.6, CA-125 (U/mL) 36, CA 19-9 (U/mL) 6.1, Rheumatoid factor (IU/mL) <30, Antinuclear antibody negative, Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody Negative, Hepatitis B surface antigen Negative, Hepatitis C antibody negative, ADAMTS13 (< 20%) Thirty-one hours after presentation, bradycardia developed, followed rapidly by asystole, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation was initiated. The patient was pronounced dead 32 hours after arrival in the emergency room. The marrow aspirate results were received with occupation by neoplastic cells of large size and frequent syncytia. The autopsy revealed a tumor at the ileum 10 cm proximal from the ileocecal region. Peritoneal dissemination was recognized around the ileocecal region, pathological diagnosis of the specimen was adenocarcinoma with lymph nodes metastasis.

Discussion

Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia caused by systemic malignancies have been well described, but it is uncommon for microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia to be the predominant presenting clinical features in patients whose systemic malignancy is not initially apparent. Although occult malignancy causing microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia may be uncommon, it is an important consideration in the evaluation of patients for TTP. In the Oklahoma TTP-HUS Registry, 10 (3%) of 351 patients who were initially diagnosed as having TTP and treated with plasma exchange were subsequently and unexpectedly diagnosed with disseminated malignancy. Only systemic infections have been a more common cause of an incorrect initial diagnosis of TTP in the Oklahoma Registry. Many different malignancies may mimic TTP; the importance of prompt diagnosis of the systemic malignancy is to provide an opportunity for treatment with appropriate chemotherapy. Early recognition of cancer may not benefit many patients who present with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia since these patients often have widely disseminated cancer. Even though treatment success may be limited, prompt diagnosis is important for appropriate management. Prompt diagnosis of systemic malignancy is also important in avoiding unnecessary risks of plasma exchange treatment for TTP. The difficulty of diagnosing a systemic malignancy presenting with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia is evidence in literature.13 The diagnosis of disseminated malignancy excludes the diagnosis of TTP or HUS; these patients should not be considered to have cancer-associated TTP. Although multiple etiologies may contribute to the syndromes recognized as TTP and HUS, disseminated malignancy is a pathologically and clinically distinct disorder. Disseminated malignancy can cause microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia, in the absence of DIC, by microvascular tumor emboli. This has been most frequently observed with diffuse microscopic pulmonary involvement.14,15 ADAMTS13 activity is not severely deficient but may be lower than normal in some patients with disseminated malignancy due to high plasma levels of von Willebrand factor.16,17 Plasma exchange has no role in management when a malignant disorder is recognized. Clues that may suggest the presence of an occult systemic malignancy include presenting symptoms of dyspnea, cough, and pain other than abdominal pain. Although increased serum LDH is characteristic of patients with TTP, extreme elevations are not typical and may suggest tumor lysis. Median LDH level was 4.5 times upper the normal values (range, 3.2–8.9). D-dimers were found severely increased in all cases of disseminated cancer presenting as TTP in a recent report of several cases of disseminated cancer.18 Perhaps the most convincing clue that a patient with presumed TTP may have a disseminated malignancy is failure to respond to plasma exchange. If systematic malignancy is suspected, bone marrow biopsy is appropriate.19,20

Conclusions

The evaluation and management of patients who present with an acute onset of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia remain critical challenges for clinicians. Although the diagnosis of TTP and urgent treatment with plasma exchange must be considered in patients with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia, the possibility that all of the clinical features of TTP may be caused by an occult disseminated malignancy must be appreciated. With increased awareness of the possible diagnosis of disseminated malignancy, the diagnosis can be made sooner, avoiding unnecessary plasma exchange treatment and allowing appropriate chemotherapy treatment

References

- 1.George JN. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. New Eng J Med. 2006;354:1927–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp053024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.George JN, Vesely SK, Terrell DR. The Oklahoma Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura-Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome TTP-HUS) Registry: A community perspective of patients with clinically diagnosed TTP-HUS. Semin Hematol. 2004;41:60–7. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waugh TR. Hemolytic anemia in carcinomatosis of the bone marrow. Am J Med Sci. 1936;191:160–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brain MC, Dacie JV, Hourihane OB. Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia: The possible role of vascular lesions in pathogenesis. Br J Haematol. 1962;8:358–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1962.tb06541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forshaw J, Harwood L. Poikilocytosis associated with carcinoma. Arch Intern Med. 1966;117:203–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lohrmann HP, Adam W, Heymer B, et al. Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia in metastatic carcinoma. Ann Int Med. 1973;79:368–75. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-79-3-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antman KH, Skarin AT, Mayer RJ, et al. Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and cancer: A review. Medicine. 1979;58:377–84. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197909000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howard MA, Williams LA, Terrell DR, et al. Complications of plasma exchange in patients treated for clinically suspected thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpurahemolytic uremic syndrome. III. An additional study of 57 consecutive patients, 2002–5. Transfusion. 2006;46:154–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.George JN. How I treat patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpurahemolytic uremic syndrome. Blood. 2000;96:1223–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.George JN, Vesely SK, Terrell DR. The Oklahoma thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura-hemolytic uremic syndrome TTP-HUS) registry: a community perspective of patients with clinically diagnosed TTP-HUS. Semin Hematol. 2004;41:60–7. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moake JL. Thrombotic microangiopathies. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:589–600. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vesely SK, George JN, Lammle B, et al. ADAMTS13 activity in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura-hemolytic uremic syndrome: relation to presenting features and clinical outcomes in a prospective cohort of 142 patients. Blood. 2003;101:60–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furlan M, Robles R, Lämmle B. Partial purification and characterization of a protease from human plasma cleaving von Willebrand factor to fragments produced by in vivo proteolysis. Blood. 1996;87:4223–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Systrom DM, Mark EJ. Case records of the Massachusetts Hospital: A 55-year-old woman with acute respiratory failure and radiographically clear lungs. New Eng J Med. 1995;332:1700–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506223322508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kane RD, Hawkins HK, Miller JA, et al. Microscopic pulmonary tumor emboli associated with dyspnea. Cancer. 1975;36:1473–82. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197510)36:4<1473::aid-cncr2820360440>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fontana S, Gerritsen HE, Hovinga JK, et al. Microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia in metastasizing malignant tumours is not associated with a severe deficiency of the von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease. Br J Haematol. 2001;113:100–2. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mannucci PM, Capoferri C, Canciani MT. Plasma levels of von Willebrand factor regulate ADAMTS-13, its major cleaving protease. Br J Haematol. 2004;126:213–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oberic L., Buffet M., Schwarzinger M., et al. Cancer Awareness in Atypical Thrombotic Microangiopathies Oncologist. 2009;14:769–79. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Francis KK, Kalyanam N, Terrell DR, et al. Disseminated malignancy misdiagnosed as thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: A report of 10 patients and a systematic review of published cases. The Oncologist. 2007;12:11–9. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Francis Kristin K., Kojouri Kiarash, George James N. Occult systemic malignancy masquerading as thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura–hemolytic uremic syndrome 2005. Community Oncology. Volume 2:4330–4343. [Google Scholar]