Abstract

Objective

Cognitive impairments among older adults are commonly linked to poor medical and psychiatric treatment adherence, increased disability, and poor health outcomes. Recent investigations suggest that cognitive impairments are frequently not recognized by healthcare providers and are often poorly documented in medical records. Older adults utilizing services at community mental health centers have numerous risk factors for developing cognitive impairment. Few studies have explored the incidence and documentation of cognitive impairments in this patient population.

Methods

Data were collected from 52 ethnically diverse older adults with severe mental illness who were participating in treatment at a large community mental health center. Cognitive impairment was diagnosed by neuropsychologists utilizing the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale-2 (DRS). Measures of depression severity and substance abuse history were also obtained. An age and education corrected DRS total score falling at or below the tenth percentile was used as the criteria for diagnosing cognitive impairment. A medical chart review was subsequently conducted to determine the documentation of cognitive impairments among this patient population.

Results

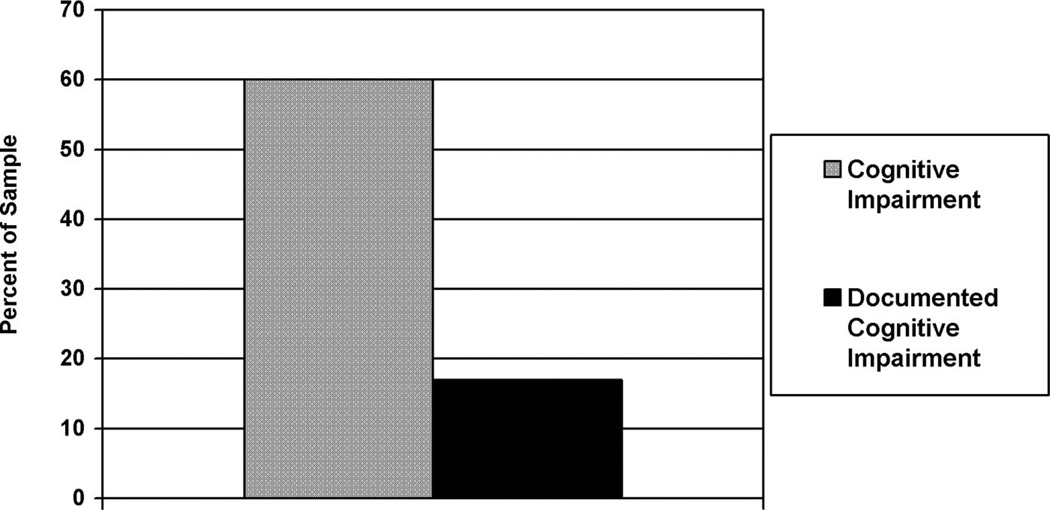

Cognitive impairment was exhibited by 60% of participants and documented in medical charts for 17% of the sample.

Conclusions

Preliminary data suggests that cognitive impairment is common in individuals with severe mental illness treated at community mental health centers, but these cognitive impairments are not well recognized or documented. The impact of cognitive impairment on psychiatric treatment and case management among community mental health patients is therefore poorly understood.

Keywords: Cognitive impairment, severe mental illness, depression, documentation, community mental health

Cognitive impairment can include both dementia and milder cognitive deficits that do not meet criteria for dementia.1,2 Estimates of the prevalence of dementia among community dwelling adults over the age of 65 range from 3%–6% with prevalence rates increasing with age.3–5 Mild cognitive deficits have been estimated to be approximately two to four times as common as dementia6 with prevalence rates among older adults in community samples ranging from 3%–20%.6,7 Cognitive impairment among older adults can be caused by a number of factors, including neurological disorders,7,8 psychiatric disorders,9–11 substance abuse,12,13 medical illness,14,15 and medication side effects.16 Cognitive impairment in older adults has been linked to poor medical and psychiatric treatment adherence,17–20 increased disability,21–23 and increased mortality.21,24 Additionally, cognitive impairment has been linked to decreased effectiveness of psychiatric interventions25–27 and poor utilization of outpatient mental health services.28

Given the numerous links between cognitive impairment and poor health outcomes, the need for early detection of cognitive impairment is typically not disputed. However, recent investigations suggest that cognitive impairment is frequently not recognized by healthcare providers and is poorly documented in medical records. In one recent study evaluating physician recognition and documentation of cognitive impairment in women over the age of 75, cognitive impairment was found to be correctly identified in 81% of patients with dementia and in 44% of patients with cognitive impairment not meeting criteria for dementia.29 Further, this study revealed that cognitive impairment was documented in medical records for 83% of the demented patients and for only 26% of individuals with cognitive impairments not meeting criteria for dementia. Similar rates of documentation of cognitive impairment are reported in other studies30–33 and suggest an increased need for accurate diagnosis and improved documentation in medical records.

Community mental health agencies typically offer psychological interventions and case management services to older individuals with severe mental illness. Individuals served at these facilities commonly have numerous chronic psychiatric illnesses, substance abuse histories, and significant medical comorbidities.34,35 Despite these risk factors for cognitive impairment, and the potential impact of cognitive impairment on psychiatric and substance abuse interventions, very little is known about the incidence of cognitive impairment in older adults receiving services in community mental health settings. Establishing the incidence of cognitive impairment among this vulnerable patient group is the first step in determining the impact of cognitive deficits on mental health interventions in these settings.

METHODS

Participants

This study represents a preliminary study conducted to determine the incidence and documentation of cognitive impairment in older adults with severe mental illness participating in treatment at a community mental health center. All study procedures received approval by an institutional review board for human research. Participants included older adults (ages 56 and older) recruited from a large community mental health agency in San Francisco. Of approximately 92 patients participating in day programming on a consistent basis, 52 participants volunteered to participate in this study. Twenty-five participants were men (48%); 64% were White, 14% were Asian, 14% were African American, 2% were Pacific Islanders, and 6% of participants identified as belonging to “other” ethnic groups. The mean age of the sample was 69.4 years (SD = 7.4) and the mean level of education was 13.4 years (SD = 3.1). Sixty-one percent of the sample lived independently, 28% lived in board and care facilities, and 12% lived in supportive senior centers.

Procedure

Study Design

Participation in this study was voluntary. Patients were provided information about the study by posting fliers in the lobby of the community mental health facility and through brief announcements given by community mental health center staff at the beginning of day programming. Interested individuals discussed the project with community mental health center staff members and assessment appointments with research staff were subsequently scheduled for individuals interested in participating in the study. All participants provided informed consent for their participation in this project. Neuropsychologists, psychologists, or trained research assistants administered an assessment battery including measures of cognitive functioning, depression, and substance abuse history. All assessments were conducted at the community mental health agency facility. Information obtained during research evaluations was not included in patients’ clinical record. Two identified staff members from the community mental health center conducted medical chart reviews for participants to obtain current psychiatric diagnoses and to determine if participants had documentation of cognitive impairments in their medical record. Not all participants completed all measures.

Measures

Mattis Dementia Rating Scale-2

The Mattis Dementia Rating Scale-2 (DRS)36 is a measure of overall cognitive functioning for older adults and has been shown to be a valid and sensitive indicator of cognitive impairments among older primary care patients.37 The DRS provides indices of cognitive functioning for the following cognitive domains: attention, initiation or perseveration (executive functioning), memory, construction (visuospatial processing), and conceptualization. The DRS has established psychometric properties for each cognitive domain scale referenced to age-matched peers.36 In addition, age and education corrected scaled scores for the DRS total score38 are also available and were utilized to calculate standard scores for the DRS total score for this study.

Clinical Dementia Rating Scale

The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale39 is a screening measure utilized to assess functional declines in older adults to classify stages of dementia. For this study, ratings of functional status in six major domains of the CDR (memory, orientation, judgment plus problem solving, community affairs, home plus hobbies, and personal care) were rated by research clinicians based on the report of case managers working with each participant. From these ratings a total CDR score is obtained. The CDR total score is a 5-point scale with “0” denoting no cognitive impairment and the remaining 4-points correspond to various stages of dementia (0.5 = very mild or questionable, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe).

The Mini-Mental State Examination

The Mini-Mental State Examination40 is a commonly used screening measure of cognitive function and consists of 21 items that assess orientation, attention, short-term memory, constructional abilities, and ability to follow instructions; scores range from 0 to 30.

Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression

The Hamilton Rating scale for depression (HAM-D)41 is a 17-item instrument yielding scores from 0 to 34; high scores indicated greater severity of depression. The HAM-D has been shown to be a valid and reliable measure of depressive symptoms.42–44

CAGE Questionnaire

The CAGE questionnaire45 is derived from the phrasing of four questions about the need to “cut down on your drinking,” being “annoyed by people criticizing your drinking,” having “felt bad or guilty about your drinking,” and “ever having a drink first thing in the morning (eye-opener) to steady your nerves or get rid of a hangover.” A point is scored for each positive response. This screening instrument assesses lifetime prevalence of alcohol problems; history of alcohol problems and current alcohol problems are not differentiated. The CAGE questionnaire has been shown to be valid46 and has been demonstrated to have good sensitivity and specificity in detecting history of alcoholism among individuals with a variety of mental illnesses.47

Data Analytic Procedure

Cognitive impairment was defined as a total DRS score falling at or below the tenth percentile when referenced to age and education matched peers. DRS performance falling between the third and tenth percentile was classified as “mild cognitive impairment.” DRS performance falling at or below the second percentile was classified as “severe cognitive impairment.” Documentation of cognitive impairment was obtained through medical chart review by agency staff who did not know the results of participants’ cognitive test results. Any diagnosis of cognitive impairment (mild cognitive impairment, dementia) or reference to a patient exhibiting symptoms of cognitive impairment in the patient’s treatment summary was rated as “cognitive impairment documented in medical chart.” Multiple regression analyses were then conducted to determine if demographic variables (age, education, ethnicity), severity of depressive symptoms (HAM-D total score), and substance abuse histories (CAGE total score) were significant predictors of cognitive impairment. Logistic regression analyses were utilized to determine if ethnicity or psychiatric diagnosis were significant predictors of impaired performance on the DRS. To test for multicollinearity, we evaluated the tolerance of independent predictor variables. An alpha of 0.05 was used for all statistical tests.

RESULTS

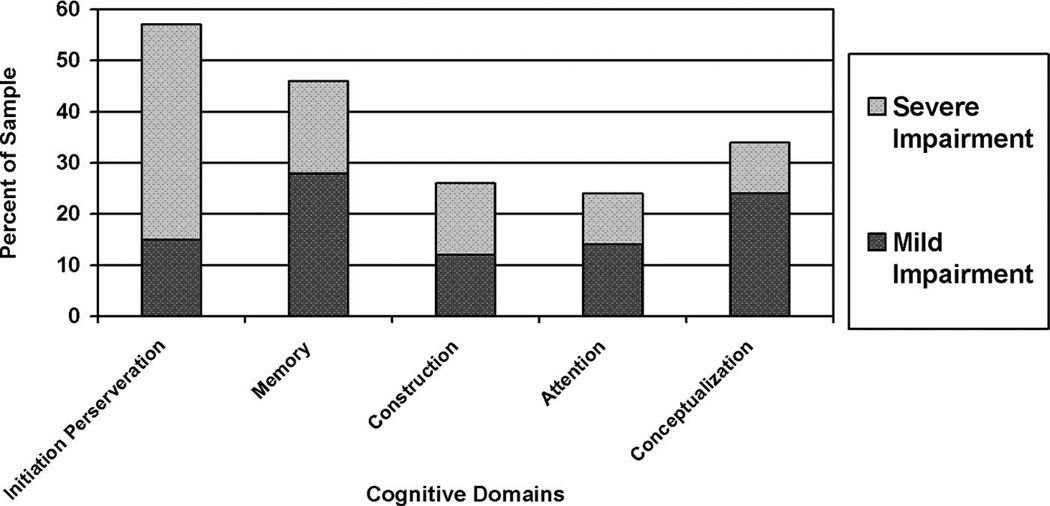

Table 1 provides the primary psychiatric diagnoses of the sample obtained through medical chart abstraction. The majority of patients in this sample were diagnosed with major depression, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder. Overall, 92% of the sample had a primary psychiatric diagnosis documented in their medical chart. The remaining 8% of the sample who did not have a primary psychiatric diagnosis specified utilized provisional psychiatric diagnoses or documentation of primary psychiatric diagnosis was unavailable. Table 2 provides the means and standard deviations for demographic variables and cognitive measures for the sample. Sixty percent (N = 31) of the sample demonstrated performance indicative of cognitive impairment based on the total DRS score. Of these, 35% demonstrated performance consistent with severe cognitive impairment and 25% demonstrated performance consistent with mild cognitive impairment. The proportion of the sample demonstrating mild and severe cognitive deficits on each subscale of the DRS is shown in Fig. 1. Seventeen percent (N = 9) of the total sample had documentation of cognitive impairment in their medical chart (Fig. 2). Twenty-six percent (N = 8) of cognitively impaired individuals had documentation of cognitive impairment in their medical record. Documentation of cognitive impairment among individuals with severe cognitive deficits was more common (32%) than documentation in individuals with milder deficits (17%). One cognitively normal individual had a diagnosis of cognitive impairment in their medical record.

TABLE 1.

Primary Psychiatric Diagnoses for the Sample Obtained by Medical Chart Abstraction (n = 52)

| % of Sample |

|

|---|---|

| Primary psychiatric diagnoses | |

| Major depressive disorder | 35 |

| Bipolar disorder | 12 |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 17 |

| Schizophrenia | 20 |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 2 |

| Delusional disorder | 6 |

| No primary psychiatric diagnosis specified | 8 |

| Total | 100 |

| Clinical dementia rating scale | |

| Normal (0) | 37 |

| Questionable (.5) | 34 |

| Mild (1.0) | 24 |

| Moderate (2.0) | 5 |

| Severe (3.0) | 0 |

| Total | 100 |

TABLE 2.

Mean Cognitive Performance, Depression Severity, and Substance Abuse History Ratings for the Sample (n = 52)

| n | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia rating scale performance (scaled scores) | 52 | ||

| Attention | 52 | 10.0 | 3.2 |

| Initiation/Perseveration | 52 | 6.3 | 3.6 |

| Construction | 52 | 8.5 | 2.8 |

| Conceptualization | 52 | 7.9 | 2.6 |

| Memory | 52 | 7.9 | 3.6 |

| Total DRS score | 52 | 6.6 | 3.8 |

| Mini-mental state examination | 51 | 26.1 | 3.2 |

| Hamilton depression scale | 51 | 11.6 | 9.2 |

| CAGE gateway questions | 51 | 1.5 | 1.9 |

| Clinical dementia rating scale | 43 | 0.69 | 1.54 |

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of Specific Cognitive Deficits on Dementia Rating Scale (DRS) Subscales (n = 52)

FIGURE 2.

Rates of Medical Chart Documentation of Cognitive Impairments Compared With Impairment on Neuropsychological Performance (n = 52)

The mean HAM-D score for the sample was 11.9 (SD = 9.3) and 22% of the sample reported experiencing significant depressive symptoms (HAM-D >19) at the time of the cognitive evaluation. Forty-nine percent of participants reported symptoms suggestive of past or present substance abuse histories (CAGE >2). The correlation between demographic variables, depressive symptoms, and substance abuse histories are provided in Table 3. After Bonferroni correction, age and total scores on the HAM-D and CAGE score were not significantly correlated with cognitive performance. Similarly, total score on the HAM-D, age, education, and CAGE scores were not significant predictors of cognitive impairment in this sample F (4,48) = 0.449, p = 0.772. Further, ethnicity and psychiatric diagnosis were not found to be significant predictors of cognitive impairment in logistical regression analyses, F (2,49) = 1.40, p = 0.264.

TABLE 3.

Correlations of Cognitive Performance to Psychiatric Measures and Demographic Variables (n = 52)

| Age | DRS Att | DRS Mem | DRS Concept | DRS Const | DRS I/P | DRS Total | HAM-D | CAGE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.0 | ||||||||

| DRS Att | 0.259 | 1.0 | |||||||

| DRS Mem | −0.220 | 0.247 | 1.0 | ||||||

| DRS Concept | −0.195 | 0.508a | 0.598a | 1.0 | |||||

| DRS Const | −0.064 | 0.329b | 0.330b | 0.491a | 1.0 | ||||

| DRS I/P | −0.161 | 0.279 | 0.551a | 0.461a | 0.217 | 1.0 | |||

| DRS total | −0.109 | 0.507a | −0.220 | 0.675a | 0.400a | 0.802a | 1.0 | ||

| HAM-D | −0.210 | −0.037 | −0.012 | −0.155 | 0.221 | −0.101 | −0.087 | 1.0 | |

| CAGE | −0.350b | −0.182 | −0.057 | 0.133 | −0.054 | 0.021 | −0.084 | 0.305b | 1.0 |

p <0.01.

p <0.05.

DRS: Dementia Rating Scale; Att: Attention scale; Mem: Memory scale; Concept: Conceptualization scale; Const: Construction scale; I/P: Initiation/Perseveration scale; HAM-D: Hamilton Depression Scale; CAGE: CAGE questionnaire.

CONCLUSIONS

This study was conducted as a preliminary study to determine the incidence and documentation of cognitive impairment among a sample of older adults with severe mental illness participating in treatment at a large community mental health center. The results of this study suggest that cognitive impairments in older adults receiving services at community mental health centers may be significantly higher than the rates found within community samples or among other medical populations. Further, these deficits are recognized and documented in less than a third of individuals with cognitive impairment. The poor documentation of cognitive impairments in our sample is largely consistent with the poor documentation of cognitive impairment in other clinical samples, particularly for individuals with cognitive impairment not meeting criteria for dementia.32,48 Nonetheless, given the significant medical and psychiatric treatment needs for this patient group, future studies conducted to determine the impact of cognitive impairment on mental health outcomes among community mental health patients are crucial.

Findings that deficits of executive functioning and memory were the most commonly observed deficits in our sample is not surprising given the well documented association of the types of cognitive deficits to depression, schizophrenia, and substance abuse. As even mild impairments of memory and executive dysfunction can have significant impact on mental health or substance abuse interventions, the incidence of these cognitive impairments further underscores the need to evaluate the impact of specific types of cognitive impairment on treatment outcomes in community mental health centers. Further, the variability in cognitive deficits manifested and the severity of cognitive impairments exhibited also suggests that neurodegenerative disorders, such as cerebrovascular disease and Alzheimer disease, are also likely contributing to the cognitive deficits identified. As such, the impact of neurodegenerative disease on community mental health outcomes should be explored in future studies.

This investigation was conducted to gather preliminary data for a larger study and several limitations of the present study should be highlighted with regard to our interpretation of this data. First, by design, our sample size was small and as such we may not have achieved a sample that was sufficient to generalize to the population. Additionally, our sample consisted of only one-half of the total number of individuals participating in day programming at the community mental health center. As such, our results may have been influenced by the participant self-selection biases, e.g., individuals aware of cognitive difficulties may have been less likely to participate in this study than cognitively intact individuals. However, because recruitment for this study was accomplished through announcements by community mental health center staff and posting of flyers in waiting rooms, we did not have contact with individuals who were not interested in participating in the study. As a result, we are not able to identify if there were significant clinical differences between volunteers and individuals who did not participate in the study. Further, our small sample may have obstructed our ability to identify specific factors predictive of cognitive impairment which could explain why our preliminary results did not establish an association between cognitive impairment and age, education, depressive symptoms, or substance abuse histories. Another significant limitation of this study was that we did not conduct a comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation, obtain a detailed medical history, or obtain an informant history of a decline in the patients’ functional ability. All of these would be required for a formal diagnosis of dementia or mild cognitive impairment. However, our intent for this preliminary study was to determine if further investigation evaluating the recognition and documentation of cognitive impairments in older adults receiving services at community mental health centers was warranted. As such, we utilized measures of cognitive and psychiatric status that have established psychometric properties that could be conducted in a relatively short period of time to minimize burden on volunteers for this study. The cognitive measure we selected for this preliminary evaluation has excellent normative data for age and education matched peers, a relatively short administration time, and has been shown to be less influenced by ethnicity than other commonly used measures of mental status.

These limitations notwithstanding, the results of this study suggest that cognitive impairments are common in older adults with severe mental illness receiving services at community mental health centers. Further, these cognitive deficits are likely under-recognized based on the rates of documentation in medical charts that we documented. Given the relationship of cognitive impairments and poor health outcomes in other patient populations, there is a need for further investigation on the impact of cognitive impairments on mental health interventions provided at community mental health centers.

Footnotes

Presented at the 20th annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, New Orleans, LA.

References

- 1.Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Brien JT, Erkinjuntti T, Reisberg B, et al. Vascular cognitive impairment. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:89–98. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00305-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans DA, Funkenstein HH, Albert MS, et al. Prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in a community population of older persons. Higher than previously reported. JAMA. 1989;262:2551–2556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoenberg BS, Kokmen E, Okazaki H. Alzheimer’s disease and other dementing illnesses in a defined United States population: incidence rates and clinical features. Ann Neurol. 1987;22:724–729. doi: 10.1002/ana.410220608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green RC, Cupples LA, Kurz A, et al. Depression as a risk factor for Alzheimer disease: the MIRAGE study. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:753–759. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.5.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham JE, Rockwood K, Beattie BL, et al. Prevalence and severity of cognitive impairment with and without dementia in an elderly population. Lancet. 1997;349:1793–1796. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)01007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petersen RC, Doody R, Kurz A, et al. Current concepts in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1985–1992. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.12.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huber SJ, Shuttleworth EC, Freidenberg DL. Neuropsychological differences between the dementias of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Arch Neurol. 1989;46:1287–1291. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520480029015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lockwood KA, Alexopoulos GS, van Gorp WG. Executive dysfunction in geriatric depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1119–1126. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heinrichs RW, Zakzanis KK. Neurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology. 1998;12:426–445. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.12.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Depp CA, Lindamer LA, Folsom DP, et al. Differences in clinical features and mental health service use in bipolar disorder across the lifespan. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:290–298. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.4.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo Z, Wills P, Viitanen M, et al. Cognitive impairment, drug use, the risk of hip fracture in persons over 75 years old: a community-based prospective study. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:887–892. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jovanovski D, Erb S, Zakzanis KK. Neurocognitive deficits in cocaine users: a quantitative review of the evidence. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2005;27:189–204. doi: 10.1080/13803390490515694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tervo S, Kivipelto M, Hänninena T, et al. Incidence and risk factors for mild cognitive impairment: a population-based three-year follow-up study of cognitively healthy elderly subjects. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17:196–203. doi: 10.1159/000076356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sinclair AJ, Girling AJ, Bayer AJ. Cognitive dysfunction in older subjects with diabetes mellitus: impact on diabetes self-management and use of care services. All Wales Research into Elderly (AWARE) study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2000;50:203–212. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(00)00195-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wonodi I, Hong LE, Thaker GK. Psychopathological and cognitive cognitive correlates of tardive dyskinesia in patients treated with neuroleptics. Adv Neurol. 2005;96:336–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeste SD, Patterson TL, Palmer BW, et al. Cognitive predictors of medication adherence among middle-aged and older outpatients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2003;63(1–2):49–58. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okuno J, Yanagi H, Tomura S. Is cognitive impairment a risk factor for poor compliance among Japanese elderly in the community? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;57:589–594. doi: 10.1007/s002280100347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maidment R, Livingston G, Katona C. Just keep taking the tablets: adherence to antidepressant treatment in older people in primary care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17:752–757. doi: 10.1002/gps.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spriet A, Beiler D, Dechorgnat J, et al. Adherence of elderly patients to treatment with pentoxifylline. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1980;27:1–8. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1980.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGuire LC, Ford ES, Ajani UA. The impact of cognitive functioning on mortality and the development of functional disability in older adults with diabetes: the second longitudinal study on aging. BMC Geriatr. 2006;6:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-6-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orsitto G, Cascavilla L, Franceschi M, et al. Influence of cognitive impairment and comorbidity on disability in hospitalized elderly patients. J Nutr Health Aging. 2005;9:194–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stuck AE, Walthert JM, Nikolaus T, et al. Risk factors for functional status decline in community-living elderly people: a systematic literature review. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:445–469. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00370-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inouye SK, Peduzzi PN, Robison JT, et al. Importance of functional measures in predicting mortality among older hospitalized patients. JAMA. 1998;279:1187–1193. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.15.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohlman J, Gorman JM. The role of executive functioning in CBT: a pilot study with anxious older adults. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:447–465. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, et al. Executive dysfunction and long-term outcomes of geriatric depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:285–290. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexopoulos GS, Kiosses DN, Heo M, et al. Executive dysfunction and the course of geriatric depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Walling D, et al. Cognitive functioning predicts outpatient service utilization in schizophrenia. Ment Health Serv Res. 2004;6:185–188. doi: 10.1023/b:mhsr.0000036491.58918.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chodosh J, Petitti DB, Elliott M, et al. Physician recognition of cognitive impairment: evaluating the need for improvement. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1051–1059. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hustey FM, Meldon S, Palmer R. Prevalence and documentation of impaired mental status in elderly emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:1166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Souder E, O’Sullivan PS. Nursing documentation versus standardized assessment of cognitive status in hospitalized medical patients. Appl Nurs Res. 2000;13:29–36. doi: 10.1016/s0897-1897(00)80016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Callahan CM, Hendrie HC, Tierney WM. Documentation and evaluation of cognitive impairment in elderly primary care patients. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:422–429. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-6-199503150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gruber-Baldini AL, Boustani M, Sloane PD, et al. Behavioral symptoms in residential care/assisted living facilities: prevalence, risk factors, and medication management. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1610–1617. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Segal SP, Hardiman ER, Hodges JQ. Characteristics of new clients at self-help and community mental health agencies in geographic proximity. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:1145–1152. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.9.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Florio ER, Hendryx MS, Jensen JE, et al. A comparison of suicidal and nonsuicidal elders referred to a community mental health center program. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1997;27:182–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mattis S. Dementia Rating Scale-2: Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Green RC, Woodard JL, Green J. Validity of the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale for detection of cognitive impairment in the elderly. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1995;7:357–360. doi: 10.1176/jnp.7.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lucas JA, Ivnik RJ, Smith GE, et al. Normative data for the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1998;20:536–547. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.4.536.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leentjens AF, Verhey FRJ, Lousberg R, et al. The validity of the Hamilton and Montgomery-Asberg depression rating scales as screening and diagnostic tools for depression in Parkinson’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:644–649. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200007)15:7<644::aid-gps167>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rehm LP, O’Hara MW. Item characteristics of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. J Psychiatr Res. 1985;19:31–41. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(85)90066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Knesevich JW, Biggs JT, Clayton PJ, et al. Validity of the Hamilton Rating Scale for depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1977;131:49–52. doi: 10.1192/bjp.131.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252:1905–1907. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.14.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aertgeerts B, Buntinx F, Kester A. The value of the CAGE in screening for alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence in general clinical populations: a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:30–39. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dervaux A, Baylé FJ, Laqueille X, et al. Validity of the CAGE questionnaire in schizophrenic patients with alcohol abuse and dependence. Schizophr Res. 2006;81(2–3):151–155. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lopponen M, Räihä I, Isoaho R, et al. Diagnosing cognitive impairment and dementia in primary health care—a more active approach is needed. Age Ageing. 2003;32:606–612. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afg097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]