Abstract

Objectives

Main objectives were to familiarize the reader with a theoretical framework for modifying evidence-based interventions for cultural groups, and to provide an example of one method, Formative Method for Adapting Psychotherapies (FMAP), in the adaptation of an evidence-based intervention for a cultural group notorious for refusing mental health treatment.

Methods

Provider and client stakeholder input combined with an iterative testing process within the FMAP framework was utilized to create the Problem Solving Therapy—Chinese Older Adult (PST-COA) manual for depression. Data from pilot-testing the intervention with a clinically depressed Chinese elderly woman are reported.

Results

PST-COA is categorized as a ‘culturally-adapted’ treatment, where core mediating mechanisms of PST were preserved, but cultural themes of measurement methodology, stigma, hierarchical provider-client relationship expectations, and acculturation enhanced core components to make PST more understandable and relevant for Chinese elderly. Modifications also encompassed therapeutic framework and peripheral elements affecting engagement and retention. PST-COA applied with a depressed Chinese older adult indicated remission of clinical depression and improvement in mood. Fidelity with and acceptability of the treatment was sufficient as the client completed and reported high satisfaction with PST-COA.

Conclusions

PST, as a non-emotion-focused, evidence-based intervention, is a good fit for depressed Chinese elderly. Through an iterative stakeholder process of cultural adaptation, several culturally-specific modifications were applied to PST to create the PST-COA manual. PST-COA preserves core therapeutic PST elements but includes cultural adaptations in therapeutic framework and key administration and content areas that ensure greater applicability and effectiveness for the Chinese elderly community.

Keywords: Chinese, cultural adaptation, depression, evidence-based practice, gerontology, psychotherapy

Introduction

Amidst increasing global diversification, a debate questioning the effectiveness of evidence-based interventions (EBIs) with diverse communities has risen to the forefront of clinical psychology (Bernal, 2006; McKleroy et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2008; Streiker, 2008; Sue et al., 2009). In response, many have developed culturally-adapted treatments, or psychotherapy options tailored to the specific needs of a cultural minority population (Hall, 2001; Gil et al., 2004; Hinton et al., 2006; Gone, 2009). Recent data have found that these culturally-adapted treatments are effective (Griner and Smith, 2006), supporting that there is a growing need for such adapted treatments (Castro et al., 2010). The present study aims to culturally adapt an EBI for depression in Chinese older adults, a cultural minority population notorious for low utilization of mental health services.

A core controversy in this relatively new field of cultural treatment adaptations is that of treatment fidelity versus cultural validity. Arguments favoring treatment fidelity posit that EBIs should be delivered to all diverse individuals as originally tested and manualized (Perepletchikova et al., 2007), whereas cultural validity promotes the idea that treatment must be culturally modified to enhance treatment response, engagement, and availability for diverse populations (Bernal and Scharron-del-Rio, 2001; Castro et al., 2004; Falicov, 2009). This debate has illuminated three main issues to be considered in deciding when, how, and how much to adapt EBIs.

Justification for adaptation: when to adapt

One criticism of the cultural adaptation approach is that adapting individual EBIs for different cultural groups is inefficient and costly, and should be justified before pursued (Elliot and Mihalic, 2004; Lau, 2006). Utilizing a theory- and data-driven model, Lau (2006) proposed that ineffective engagement of underserved populations with a treatment justifies the need for cultural adaptations to increase accessibility of that EBI. Chinese elderly are a group who are underserved by and ineffectively engage with EBIs. Despite studies showing more Chinese elderly experience depression symptoms than the general elderly population (Stokes et al., 2001) and that depression in this group is underreported and poorly understood (Mui et al., 2001), few Chinese elderly seek help for their mental health problems. The mental health literature has consistently reported low mental health service utilization by Asian Americans at various stages of the help-seeking process including initial unwillingness to seek treatment, poor attendance of first appointments, and low completion of treatment (e.g., Akutsu et al., 2006; Lin, 1998; Zhang et al., 1998; U.S. DHHS, 2001). One important explanation for this low service utilization has been a lack of culturally congruent treatments (Chin, 1998; Hall, 2001; Miranda et al., 2003). Consistent with guidelines outlined by Lau (2006), these low levels of clinical engagement indicate a need for culturally-adapted EBIs to provide viable treatment options for Chinese elderly.

Methods of adaptation: how to adapt

Recently, several models for the cultural adaptation process have been offered, with most involving different variations around four basic adaptation phases: information gathering, development of initial adaptation design, pilot testing, and additional refinement (Barrera and Castro, 2006).The Formative Method for Adapting Psychotherapy (FMAP; Hwang, 2009), for example, includes these four adaptation phases and is a community-based, bottom-up approach which combines collaboration with mental health providers and consumer stakeholders. The FMAP consists of generating knowledge and collaborating with stakeholders, integrating generated information with theory, empirical, and clinical knowledge, reviewing and revising the adapted intervention, testing, and finalizing the culturally-adapted intervention.

The FMAP was chosen in the current study because it presents several important advantages for underserved populations like the Chinese elderly over previous approaches toward cultural adaption. First, the FMAP occurs in the community where treatment is provided, thereby increasing ecological validity and stakeholder involvement. Second, the FMAP provides systematic guidelines for incorporating empirical, clinical, and field knowledge. Because of its recent introduction to the field, none have demonstrated this iterative stakeholder model with an older adult ethnic minority population.

Areas of adaptation: how much to adapt

The cultural modification process can result in EBIs that remain unchanged to EBIs needing substantial modifications to achieve cultural fit. Most culturally-adapted EBIs are situated in the middle of this continuum. Two categorizations prove helpful in characterizing patterns of treatment components that may be targeted in the modification process. First, Falicov (2009) delineated three categories representing varying extents of cultural alterations to EBIs. ‘Culturally-attuned’ treatments are modified the least and focus on treatment delivery components like engagement and retention rather than treatment content such as skill acquisition. ‘Culturally-adapted’ treatments preserve core mediating treatment mechanisms but add cultural content throughout the treatment to enhance cultural relevance. ‘Culturally-informed’ treatments incorporate cultural needs to the greatest extent and presumably involve the highest levels of modification, though few studies have discussed this distinction.

Not only are there differing extents to which an EBI can be adapted, but different categories of treatment components can also be modified. Surface structure or peripheral components, for example, refer to observable elements of an intervention that are similar to face validity of an assessment measure (Resnicow et al., 2000). Changes to peripheral components might increase how receptive or understandable a treatment seems to a person (Simons-Morton et al., 1997). Deep structure or core components, in contrast, reflect primary therapeutic elements mediating symptom change that may be affected by core cultural values (Resnicow et al., 2000).

Because the science of cultural modifications is relatively new, few studies delineate extent, category, and components of cultural modification when presenting a newly altered EBI. This level of specification is needed to understand patterns of cultural modification and establish next steps in the innovation of adaptation science.

Problem Solving Therapy (PST) as a depression treatment for Chinese elderly

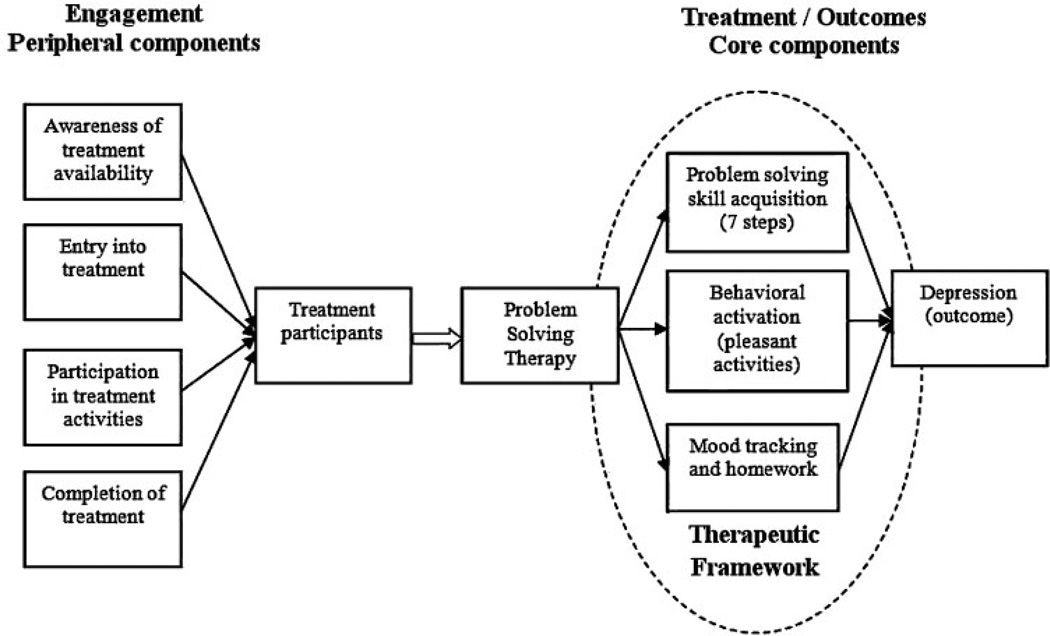

Problem-solving therapy (PST) is an evidence-based cognitive behavioral approach used to effectively treat late-life depression by teaching skills to address problems in a systematic way (Nezu, 1986; Dowrick et al., 2000; Alexopoulos et al., 2003). The problem-solving skill acquisition method includes seven stages: defining a problem, setting a goal, generating or brainstorming solutions, evaluating pros and cons of solutions, choosing a solution, implementing the solution, and evaluating the outcome (Hegel et al., 2000; Haverkamp et al., 2004). Figure 1 maps PST onto an enhanced version of a heuristic model for cultural adaptation initially presented by Barrera and Castro (2006). This theoretical framework shows peripheral components related to treatment engagement and core therapeutic components that mediate PST’s therapeutic effects on depression. One important addition to Barrera and Castro’s (2006) original model is the therapeutic framework which includes the provider/client relationship, session structure, and expectations. Core therapeutic components of PST operate within a therapeutic framework that is collaborative and structured.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework for cultural modification of PST

PST was chosen in this study as an EBI that may be a good fit for Chinese older adults for several reasons. First, PST focuses on problem-solving rather than emotion expression and exploration which fits well with Chinese cultural practices of emotion moderation (e.g., Sue and Sue, 2003; Kim et al., 2005). In addition, studies have found Chinese individuals to prefer directive, goal-oriented, short-term treatments like PST (Root, 1985). Though the basic premise of PST appears to fit well for Chinese elderly, specific PST components may conflict with Chinese cultural practices and need modification to enhance engagement and treatment effects. For example, PST, like many EBIs, assumes a collaborative provider/client stance requiring clients to assert themselves in treatment tasks like self-generating solutions and action plans. These requirements assume the importance of independent agency and may not fit well with more collectivist Chinese cultures that expect health care providers to be expert and advice-giving (Sue and Zane, 1987; Markus and Kitayama, 1991).

The present study

Goals of the current study are to utilize an iterative stakeholder process, the FMAP, to adapt PST for treatment of depression in Chinese older adults and create the Problem Solving Therapy for Chinese Older Adults (PST-COA) manual. We incorporate distinctions in extent, category, and components of cultural modification to enhance the portability and general-izability of this method to other modification efforts. In particular, we hypothesize PST-COA will fall within the ‘culturally-adapted’ category of treatment, where core mediating mechanisms of PST are preserved but cultural themes are added to core components to make the treatment more understandable and relevant for Chinese older adults. We also expect changes in the therapeutic framework and peripheral components related to engagement and retention, making PST more applicable and effective for Chinese elderly.

Methods

Phase 1: stakeholder input in a community participatory approach

Focus groups and interviews with community providers and a depressed 60-year-old Chinese elderly client were conducted to assess the feasibility of and recommended cultural modifications to PST as an intervention for Chinese older adults. Community providers included 31 mental health paraprofessionals or doctoral or masters level clinicians or trainees who serve Chinese elderly clients at three community mental health organizations in Northern California. Ten providers provide care in Mandarin and eight in Cantonese.

Focus groups and interviews, 1.5–2 h each, included an in-depth presentation of the rationale, techniques, and steps of PST followed by semi-structured questions assessing participants’ reactions to PST as a fit for Chinese elderly clients. Participants shared recommendations about what to keep and change about the treatment. All interviews were qualitatively analyzed using a grounded theory approach (Glaser, 1992) for coding and detection of themes by two independent research investigators. Major themes regarding recommended modifications were elicited using standard qualitative techniques.

Phase 2: integration of stakeholder input with literature: creation of the PST-Chinese older adult (PST-COA) manual

Empirical literature relevant to treatment for Chinese elderly was reviewed and integrated with stakeholder feedback from Phase 1. Cultural modification themes consistent with both the literature and interviews were incorporated with PST-Primary Care (Areán et al., 2008) and PST-Case Management (Areán et al., 2010) manuals to create the Problem Solving Therapy-Chinese Older Adult (PST-COA) manual1.

Phase 3: refining PST-COA with a clinical case

This PST-COA manual was piloted with ‘Grace,’ a 61-year-old first generation Chinese elderly woman recruited from a primary care clinic and diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder (and no other comorbid Axis I or II diagnoses) via SCID interview. Grace is bilingual in Cantonese and English and immigrated to the US from Hong Kong at the age of 18. She received 12 weeks of PST-COA in English from a licensed psychologist, during which she did not take any psychotropic medications. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke and Spitzer, 2002), a well-validated and reliable instrument assessing for depression severity, was administered pre- and post-treatment, and mood severity ratings 1 to 10 (1 = ☹ and 10 = ☺) were assessed at each session. Both Grace and her PST-COA therapist were interviewed separately post-treatment to ascertain the feasibility of PST-COA and any additional changes needed to the treatment. This feedback informed further refinement to create the final PST-COA treatment.

Results

Summary of modifications: The PST-COA manual

Analysis of stakeholder feedback, literature review, and pilot testing yielded five recurrent themes of cultural modifications for PST-COA, described below. The majority of cultural modifications were informed by stakeholder feedback and literature review; adaptations that were a result of feedback from client pilot-testing are indicated as such. Table 1 presents an alternative categorization of these PST-COA modifications according to steps in the PST process, compared to classic PST, and categorized by therapeutic framework, core, or peripheral PST components diagrammed in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Step-by-step guide of PST-COA cultural modifications

| PST task |

Classic PST |

PST-COA modification |

Corresponding cultural theme |

Category of modified treatment component |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Establish relationship between therapist and client | Collaborative approach | Consider establishing hierarchical relationship, such that PST therapist is the authority figure and client is the learner | Hierarchy, authority, and respect in provider/client relationships | Core components: therapeutic framework |

| Approach PST and the provider/client relationship with flexibility in structure, pace, content | Diverse psychosocial, socioeconomic, and linguistic needs of Chinese older adults may lead to varying needs of the client | |||

| Psychoeducation | The client is educated about depression as an illness linked to problems and mood or emotional problems | Use language consistent with client’s idiom of distress (e.g., refer to somatic rather than emotional symptoms) | Stigma and lack of familiarity with mental health heightens need for pre-therapy education and non-stigmatizing language | Peripheral components: Engagement, entry into and participation in treatment activities |

| Physical symptoms are attributed to client’s emotions | Familiarize and introduce the client to the process of psychotherapy (e.g., PST may require work at home, this is a collaborative relationship, we will meet on an ongoing basis) | |||

| Little mention of general education about the process of therapy, or inclusion of family members in the process | Provide family members with psychoeducation when appropriate | In collectivistic cultures, involving family in the therapy process can increase client engagement | ||

| Presenting the rationale for PST | Problems → deficient problem-solving skills → depressive symptoms → interference with problem-solving skills → more problems → worsened depression; | Problems → deficient problem-solving skills → deficiencies in health, wellness or low productivity | Stigma and lack of familiarity with mental health heightens need for pre-therapy education and non-stigmatizing language | Peripheral components: Engagement, entry into and participation in treatment activities |

| Therefore: Effective problem-solving skills → fewer problems → improved mood and depressive symptoms | Therefore: Effective problem-solving skills → fewer problems → improved health, wellness, or productivity | Chinese older adults more likely to be oriented toward physical health, overall wellness, or productivity rather than depression and mood | ||

| Teaching and applying the 7 steps of PST with clients | Emphasis on client’s self-identified problems and self-generated solutions | Therapist takes more directive approach, demonstrating how to solve a first problem, incorporating case management in initial stages of treatment, or offering specific suggestions for solutions | Cultural expectation of a more directive approach and hierarchical relationship with the therapist | Core components: Problem-solving skill acquisition |

| Client may need additional encouragement or even permission to self-generate solutions. Therapist may ask questions to stimulate ideas and solution generation | ||||

| Less acculturated clients may require therapist to teach them about locally accepted or feasible solutions | Less acculturated Chinese older adults may be less familiar with local systems and norms | |||

| Teach clients about pleasant activities | Emphasis on client’s self-generated pleasant activities | Therapist may guide client toward brainstorming and selecting pleasant activities if client is unfamiliar with local resources or norms | Cultural expectation of a more directive approach and hierarchical relationship with the therapist | Core components: Behavioral activation (pleasant activities) |

| Provide client with necessary paperwork to complete activities in session and as homework | After initially walking the client through the PST worksheet or materials, client is free to use the worksheet independently, as needed | Verbally present materials—walk clients through any written material | Chinese older adults may need visual aids and assistance in understanding worksheets that may contain unfamiliar wording | Peripheral components: Engagement, participation in treatment activities and completion of treatment |

| Provide client with worksheets organized in binder | ||||

| Use PST worksheets translated into Chinese as needed | Presenting materials up-front in an organized and concrete format will contribute to the legitimacy of the treatment | |||

| Client tracks mood on a Likert scale (e.g., mood scale 1 to 10) to track progress in PST | Rating scales are presented on a numerical scale | Rating scales are presented with pictures to accompany any words or numbers | Chinese older adults may need visual aids and assistance in understanding outcome measures that are structured with unfamiliar Likert scales | Core components: Mood tracking |

Note: PST-COA modifications are compared to classic PST and categorized by cultural theme and treatment component (therapeutic framework, core, or peripheral).

Theme 1: a need for flexibility

Providers indicated that when working with Chinese elderly, complex family relationships, medical comorbidities, language barriers, and resource needs require flexibility within the treatment framework. Though the classic PST therapeutic framework includes individual, structured weekly sessions, Chinese elderly with physical ailments (common in older adulthood) or close family relationships (a common Chinese cultural value) may require flexibility in this framework. For example, in working with a hearing-impaired Chinese elderly woman, one provider found it necessary to allow her client’s husband to join sessions to communicate on behalf of his wife. Other providers incorporated regular telephone calls with family members to increase treatment engagement and follow-through among their Chinese elderly clients.

Theme 2: psychoeducation and de-stigmatizing language

Chinese elderly have among the lowest rates of mental health service utilization (U.S. DHHS, 2001), deal with considerable stigma around mental illness (Yang et al., 2008), and therefore often know little about the process of psychotherapy. As such, providers suggested modifying PST’s psychoeducation to match Chinese older adults’ preferred terminology. For example, the first session of classic PST educates about ‘depression’ as a disease precipitated by poor problem-solving skills. Instead of clinical terminology like ‘depression’ that can activate fears around mental illness, providers suggested less stigmatizing language such as ‘wellness,’ ‘stress,’ or ‘productivity’ in PST-COA.

Psychoeducation is not eliminated altogether in PST-COA. In fact, qualitative feedback indicated that more attention is needed to orient Chinese elderly to the PST process. Compared to classic PST, a larger portion of the first PST-COA session addresses pre-therapy education about problems as related to distress, mood, and the body, the collaborative nature of the provider/client relationship, and the utility of take-home activities in-between sessions.

Theme 3: managing expectations of the provider-client relationship: hierarchy, respect, case management, and providing suggestions

Traditional PST operates under the premise that clients who develop their own solutions to problems will use them more often. Providers typically provide little input in the solution generation process. In contrast, Chinese cultures value hierarchy and respect, with establishing credibility an essential task for therapists working with Asian clients (Sue and Zane, 1987). Many Chinese clients take an advice-seeking approach to their health care providers and may see providers who ask ‘What ideas do you have for solving this problem?’ as ineffective. To account for this cultural issue, PST-COA therapists solve a first problem with their client, offering specific suggestions or resources.

Study data also showed that older Chinese clients may have difficulty brainstorming solutions to problems on their own. Feedback from client pilot-testing indicated the particular importance of using therapist-assisted questions to stimulate brainstorming: ‘If you didn’t have that problem anymore, what would life look like?’ or ‘Imagine that you didn’t have that problem: how did you get there?’ Alternatively, utilizing a strength-based perspective by inquiring about problems successfully solved in the past can facilitate solution generation.

Theme 4: visual aids and measurement

Qualitative data indicated that Chinese elderly clients, particularly first-generation immigrants, have difficulty comprehending Likert-type scales that lack a descriptor for each data point, have more than five data points, or use complicated language. Long questionnaires that query about abstract psychological concepts are also difficult to comprehend and need verbal explanation. Instead of numerical Likert-type scales in classic PST that rate depressed mood and satisfaction with problem-solving effort on scales of 1 to 10, PST-COA incorporates pictorial representations for such scales (e.g., ☺ and ☹). PST-COA also recommends that therapists assist clients in completing questionnaires and Likert-type scales. Finally, feedback from client pilot-testing indicated that PST-COA therapists should provide a binder containing visual aids (e.g., PST handouts and worksheets) to create a sense of legitimacy and increase engagement and follow-through with take-home tasks.

Theme 5: acculturative processes

In qualitative interviews, providers suggested that lower acculturated Chinese clients may generate solutions incongruent with their surrounding cultural context. In such cases, PST-COA therapists may need to highlight cultural conflicts and educate clients toward more culturally appropriate solutions. As an example of a cultural clash, one provider mentioned that for some of her elderly Chinese male clients, hitting their wives as a form of marital problem resolution is considered normal. Education about the cultural values in western countries, where this behavior is not acceptable and in some places illegal, is important in helping clients consider their solution choices.

Preliminary evidence for PST-COA with a single case

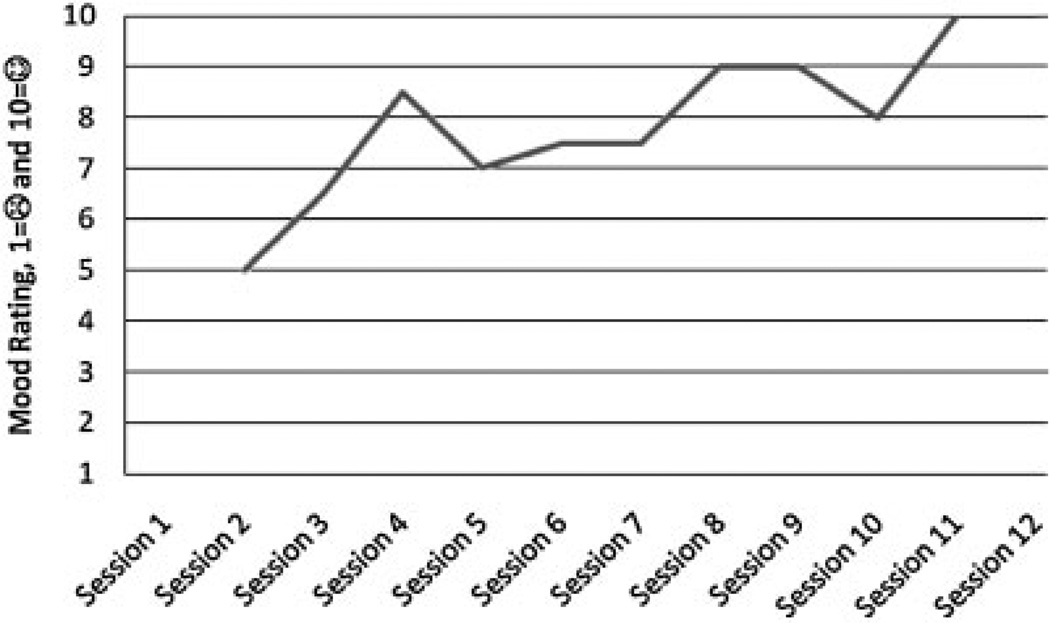

Twelve weeks of PST-COA was administered with ‘Grace,’ a 61-year-old first generation Chinese woman. Grace reported that she hasn’t been her ‘usual self’ since experiencing recent stressors including her mother’s passing, a minor car accident, assisting her aunt with a legal matter, and her father’s failing health. At SCID interview, Grace reported depressed mood, anhedonia, hypersomnia, daily fatigue, psychomotor retardation, worthlessness, and guilt, meeting criteria for Major Depressive Disorder. During treatment, Grace worked on dealing with her father’s need for caretaking in Hong Kong, communication problems with family, and her need for more physical activity. After her PST-COA treatment, Grace’s initial PHQ-9 score of 12 (a moderate level of depression) decreased to a 3, indicating remission and a subclinical level of depression. Similar to her PHQ-9 score, Grace’s initial depressed mood rating-a moderate score of 5 on scale of 1 = ☹ to 10 = ☺-improved steadily to a post-treatment mood rating of 10 (see Figure 2 for Grace’s mood progression chart).

Figure 2.

PST-COA client ‘Grace’, mood progression over 12 sessions

Feasibility of PST-COA

Consistent with expectations, community providers indicated that PST would be a good cultural fit with Chinese clients. Grace also gave positive feedback about her experience, indicating a general sense of satisfaction and effectiveness about her PST-COA treatment. Grace found the PST-COA forms useful and understood the PST skills and techniques well. Grace’s PST-COA therapist also indicated that PST-COA was feasible and palatable for her client.

Discussion

Since the advent of science-based practice, a cadre of EBIs has grown to treat a range of clinical disorders. As ethnic minority and elderly populations grow disproportionately, however, it is increasingly apparent that these EBIs are not reaching important (and often the most needy) segments of the population. In response, many scientists have called for culturally-adapted EBIs for underserved communities. The adaptation process has been commonly criticized for inefficiency, inconsistency in methodology, and lack of theoretical basis and justification of need.

Recent advances in the science of cultural modification have streamlined the adaptation process with guidelines for cultural modification and the suggestion of heuristic theoretical frameworks to guide cultural modification efforts. Given the recent nature of these advances, few studies have systematically applied these guidelines to create a culturally-modified EBI.

This study employed an iterative stakeholder process—the Formative Method for Adapting Psychotherapy (FMAP)—to demonstrate how an EBI like Problem Solving Therapy (PST) for Major Depression can be efficiently modified for an ethnic minority elderly population. Knowledge from clinical encounters, empirical literature, and stakeholder input was systematically integrated to inform the culturally-modified PST for Chinese Older Adults (PST-COA) manual.

In addition to demonstrating the utility of an iterative stakeholder modification algorithm, this study showed how a theoretical framework can be employed to categorize and communicate patterns in the modification process. We enhanced Barrera and Castro’s (2006) modification framework to present a theoretical model of PST categorized by peripheral engagement, core mediating therapeutic factors, and a therapeutic framework. Results supported the hypothesis that PST’s core mediating elements—7 steps of problem-solving skill acquisition, mood tracking, and behavioral activation—were preserved. Cultural themes, however, were applied to PST core elements to make them more understandable by Chinese elderly. Cultural themes of hierarchical provider-client relationships, for example, were integrated into problem-solving skill acquisition with demonstration of expertise by the PST-COA provider (e.g., by assisting with solution generation or solving an initial problem). PST-COA also recognizes that guidance regarding viable solutions to everyday problems may be needed for less-acculturated Chinese elderly clients.

The majority of PST alterations encompassed peripheral elements and the therapeutic framework which affect treatment acceptability and sustainability. Many of these changes such as education about the therapy process and mind-body connections, establishing credibility through active guidance, and utilizing non-stigmatizing language occur in the first session when it is important to engage clients and prevent premature attrition. Other modifications like visual aids organized into a binder and pictorial tracking scales focus on sustaining treatment engagement by making PST comprehensible for Chinese elderly.

Key changes in PST’s therapeutic framework are crucial for making PST-COA more culturally relevant. For example, whereas classic PST is predicated on a one-on-one, collaborative, structured session, PST-COA incorporates a hierarchical provider/patient relationship to enhance legitimacy and trust. PST-COA providers are also flexible with the therapeutic framework to accommodate complex psychosocial, language, and socioeconomic needs of Chinese older adults.

Overall, PST-COA incorporates a moderate level of alterations to classic PST encompassing therapeutic framework, treatment delivery components like engagement and retention, and cultural content throughout the treatment to enhance cultural relevance. According to Falicov’s (2009) suggested classification system for culturally altered EBIs, PST-COA is a ‘culturally-adapted’ rather than a ‘culturally-attuned’ or ‘culturally-informed’ treatment. In the final two stages of FMAP—testing the intervention to finalize the intervention—pilot testing of PST-COA with a depressed Chinese elderly client indicated high satisfaction with, feasibility, and acceptability of the treatment. Promising pilot-study data included remission of clinical depression and improvement in mood.

Limitations

It is important to recognize that the current study only represents a part of the overall cultural treatment modification process. Utilizing an iterative stakeholder process mapped onto a theoretical framework for PST, this study identified PST components that needed adaptation for Chinese elderly and established initial evidence of PST-COA’s feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness with one client. Further research is needed to extend next steps of the cultural modification process, which may include: (a) a single case experiment where outcomes like treatment retention and symptom improvement are linked with specific components of the PST-COA treatment process, or (b) more widespread testing of PST-COA to establish its efficacy with larger study samples and its generalization to Chinese elderly with different age, gender, language proficiency, or acculturation backgrounds. In this study, PST-COA was pilot-tested with a 61-year old Chinese woman proficient in English; this treatment should also be examined with older geriatric clients who are less acculturated or monolingual Chinese speakers. These follow-up studies should also quantitatively examine the culturally modified elements of PST-COA as moderators of treatment outcome among Chinese older adults.

Conclusions

Current results hold important implications for mental health care disparities and culturally-adapted EBIs in ethnic minority geriatric populations. First, particular attention should be directed toward modification of peripheral elements and therapeutic frameworks that will increase understanding of and engagement with EBIs. Core therapeutic elements that treat psychopathology symptoms may need integration with cultural themes, but otherwise remain relatively intact. Results also confirmed the viability of mapping EBIs onto a theoretical framework to guide the cultural modification process. Further research should investigate whether this recommended pattern and theoretical modification framework generalizes to other EBIs and diverse populations. This study is the first to modify a well-established depression treatment for Chinese older adults.

Key points.

The iterative stakeholder method (based on FMAP—the Formative Method for Adapting Psychotherapies) is a relatively efficient process for culturally modifying and testing an evidence-based intervention that can be imported to other cultural groups.

A theoretical model based on peripheral engagement, core mediating therapeutic factors, and a therapeutic framework can effectively guide the treatment cultural modification process to succinctly categorize adaptation patterns for portability and generalization to other modification efforts.

Particular attention should be directed toward modifications of peripheral elements and therapeutic frameworks of EBIs that will increase the likelihood for underserved communities to engage positively and understand evidence-based interventions.

Problem Solving Therapy modified for Chinese Older Adults (PST-COA) is a feasible and acceptable treatment for depression in Chinese older adults that incorporates modifications based on cultural themes of measurement methodology, stigma, hierarchical provider-client relationship expectations, and acculturation.

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful to Eliseo Perez-Stable, M.D., for his guidance and input on this project. This paper was funded by grant no. P30-AG15272 for the Center for Aging in Diverse Communities (CADC) under the Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research program by the National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

A copy of the Problem Solving Therapy for Chinese Older Adult Manual or Chinese-translated PST worksheet materials can be requested from the primary author.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- Akutsu PD, Tsuru GK, Chu JP. Prioritized assignment to intake appointments for Asian Americans at an ethnic-specific mental health program. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(6):1108–1115. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos G, Raue P, Areán PA. Problem-solving therapy versus supportive therapy in geriatric major depression with executive dysfunction. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11(1):46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Areán PA, Hegel M, Vannoy S, Fan MY, Unuzter J. Effectiveness of problem-solving therapy for older, primary care patients with depression: results from the IMPACT project. The Gerontologist. 2008;48(3):311–323. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Areán PA, Mackin RS, Vargas-Dwyer E, Raue P, Sirey JA, Kanellopolos D, Alexopoulos GS. Treating depression in disabled, low-income elderly: a conceptual model and recommendations for care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(8):765–769. doi: 10.1002/gps.2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Castro FG. A heuristic framework for the cultural adaptation of interventions. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2006;13(4):311–316. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G. Intervention development and cultural adaptation research with diverse families. Fam Process. 2006;45(2):143–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00087.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Scharron-del-Rio MR. Are empirically supported treatments valid for ethnic minorities? Toward an alternative approach for treatment research. Cult Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2001;7:238–342. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.7.4.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M, Martinez CR. The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prev Sci. 2004;5:41–45. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000013980.12412.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FP, Barrera M, Holleran Steiker LK. Issues and challenges in the design of culturally adapted evidence-based interventions. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:213–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-033109-132032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen EC, Kakkad D, Balzano J. Multicultural competence and evidence-based practice in group therapy. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64(11):1261–1278. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin JL. Mental health services and treatment. In: Lee LC, Zane NWS, editors. Handbook of Asian American psychology. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1998. pp. 485–504. [Google Scholar]

- Dowrick C, Dunn G, Ayuso-Mateos JL, et al. Problem solving treatment and group psychoeducation for depression: multicentre randomized controlled trial. Br Med J. 2000;321(7274):1450–1455. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7274.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot DS, Mihalic S. Issues in disseminating and replicating effective prevention programs. Prev Sci. 2004;5:47–53. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000013981.28071.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falicov CJ. Commentary: on the wisdom and challenges of culturally attuned treatments for Latinos. Fam Process. 2009;48:292–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Wagner EF, Tubman JG. Culturally sensitive substance abuse intervention for Hispanic and African American adolescents: empirical examples from the Alcohol Treatment Targeting Adolescents in Need (ATTAIN) Project. Addiction. 2004;99(2):140–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG. Basics of grounded theory analysis: emergence vs. forcing. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP. A community-based treatment for Native American historical trauma: prospects for evidence-based practice. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(4):751–762. doi: 10.1037/a0015390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griner D, Smith TB. Culturally adapted mental health interventions: a metaanalytic review. Psychother Theory Res Pract Training. 2006;43:531–548. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall GCN. Psychotherapy research with ethnic minorities: empirical, ethical, and conceptual issues. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(3):502–510. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haverkamp R, Arean PA, Hegel M, et al. Problem-solving treatment for complicated depression in late life: a case study in primary care. Perspect Psychiatr C. 2004;40(2):45–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2004.00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegel M, Barrett JE, Oxman TE. Training therapists in problem-solving treatment of depressive disorders in primary care: lessons learned from the ’Treatment Effectiveness Project’. Fam Syst Health. 2000;18(4):423–435. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Safren SA, Pollack MH, et al. Cognitive-behavior therapy for Vietnamese refugees with PTSD and comorbid panic attacks. Cogn Behav Pract. 2006;13(4):271–281. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang WC. The Formative Method for Adapting Psychotherapy (FMAP): a community-based development approach to culturally adapting therapy. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2009;40(4):369–377. doi: 10.1037/a0016240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BSK, Li LC, Ng GF. Asian American Values Scale—Multidimensional: development, reliability, and validity. Cult Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2005;11(3):187–201. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.11.3.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. A new depression and diagnostic severity measure. Psychiat Ann. 2002;32:509–521. [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS. Making a case for selective and directed cultural adaptations of evidence-based treatments: examples from parent training. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2006;13:295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Lin JCH. Descriptive characteristics and length of psychotherapy of Chinese American clients seen in private practice. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 1998;29(6):571–573. [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol Rev. 1991;98:224–253. [Google Scholar]

- McKleroy VS, Galbraith JS, Cummings B, et al. Adapting evidence-based behavioral interventions for new settings and target populations. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18 Suppl. A:59–73. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Duan N, Sherbourne C, et al. Improving care for minorities: results of a randomized, controlled trial. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:613–630. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mui AC, Burnette D, Chen LM. Cross-cultural assessment of geriatric depression: a review of the CES-D and the GDS. J Ment Health Aging. 2001;7(1):137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Nezu AM. Efficacy of social problem-solving therapy approach for unipolar depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;52(2):196–202. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perepletchikova F, Treat TA, Kazdin AE. Treatment integrity in psychotherapy research: analysis of the studies and examination of the associated factors. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(6):829–841. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Soler R, Braithwait RL, et al. Cultural sensitivity in substance abuse prevention. J Community Psychol. 2000;28:271–290. [Google Scholar]

- Root M. Guidelines for facilitating therapy with Asian American clients. Psychotherapy. 1985;22:349–356. [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG, Donohew L, Crump AD. Health communication in the prevention of alcohol, tobacco, and drug use. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24(5):544–554. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes SC, Thompson LW, Murphy S, et al. Screening for depression in immigrant Chinese-American elders: results of a pilot study. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2001;36(1–2):27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Streiker LKH. Making drug and alcohol prevention relevant: adapting evidence-based curricula to unique adolescent cultures. Fam Community Health. 2008;31(1):S52–S60. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000304018.13255.f6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Sue D. Counseling the Culturally Different: Theory and Practice. 4th edn. New York: Wiley; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sue S, Zane N. The role of culture and cultural techniques in psychotherapy: a critique and reformulation. Am Psychol. 1987;42:37–45. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.42.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue S, Zane N, Hall GCN, et al. The case for cultural competency in psychotherapeutic interventions. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:525–548. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: Culture, Race and Ethnicity—A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville: Public Health Service, Office of Surgeon General; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Yang LH, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma and beliefs of efficacy toward traditional Chinese medicine and Western psychiatric treatment among Chinese-Americans. Cult Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2008;14:10–18. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang AY, Snowden LR, Sue S. Differences between Asian- and White-Americans’ help-seeking and utilization patterns in the Los Angeles area. J Community Psychol. 1998;26:317–326. [Google Scholar]