Abstract

Background

Guidelines for the management of patients with suspected coronary artery disease (CAD) rely on the age, sex, and angina typicality-based pre-test probabilities of angiographically significant CAD derived from invasive coronary angiography (“Guideline Probabilities”). Reliability of Guideline Probabilities has not been investigated in patients referred to noninvasive CAD testing.

Methods and Results

We identified 14048 consecutive patients with suspected CAD who underwent coronary computed tomographic angiography (CTA) Angina typicality was recorded using accepted criteria. Pre-test likelihoods of CAD with ≥50% diameter stenosis (CAD50) and ≥70% diameter stenosis (CAD70) were calculated using Guideline Probabilities. CTA images were evaluated by ≥1 expert reader to determine presence of CAD50 and CAD70. Typical angina was associated with the highest prevalence of CAD50 (40% in men, 19% in women) and CAD70 (27% men, 11% women) when compared to other symptom categories (p<0.001 for all). Observed CAD50 and CAD70 prevalence were substantially lower than that predicted by Guideline Probabilities in the overall population (18% vs. 51% for CAD50, 10% vs. 42% for CAD70, p<0.001), driven by pronounced differences in patients with atypical angina (15% vs. 47% for CAD50, 7% vs. 37% for CAD70) and typical angina (29% vs. 86% for CAD50, 19% vs. 71% for CAD70). Marked overestimation of disease prevalence by Guideline Probabilities was found at all participating centers and across all sex and age subgroups.

Conclusion

In this multinational study of patients referred for coronary CTA, determination of pre-test likelihood of angiographically significant CAD by the invasive angiography-based Guideline Probabilities greatly overestimates the actual prevalence of disease.

Keywords: angina, coronary artery disease, computed tomography angiography, imaging, pre-test probability, stenosis

Estimating the pre-test likelihood of angiographically significant coronary artery disease (CAD) is a fundamental component in the initial evaluation of symptomatic patients presenting with suspected CAD. This determination directly influences subsequent decisions for noninvasive diagnostic testing and treatment.1 To assist the clinician in this task, vital reports from Diamond and Forrester, the Coronary Artery Surgery Study (CASS) Registry, and Pryor and colleagues have convincingly shown that prevalence of angiographically significant CAD depends on age, sex, and angina typicality.2-5 The American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) have since recognized these 3 characteristics as chief pre-test predictors of ≥50% diameter stenotic CAD, and the resultant reference probabilities (Table 1) have been adopted for use in the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Chronic Stable Angina and, more recently, in Appropriate Use Criteria for echocardiography, radionuclide imaging, magnetic resonance imaging, and coronary computed tomographic angiography (CTA).1,6-9

Table 1. Pre-test probabilities of ≥50% diameter stenotic coronary artery disease (CAD50) in patients with chest pain, as shown in the American College of Cardiology / American Heart Association guidelines for management of chronic stable angina.

| Nonanginal Chest Pain | Atypical Angina | Typical Angina | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women |

| 30-39 | 4% | 2% | 34% | 12% | 76% | 26% |

| 40-49 | 13% | 3% | 51% | 22% | 87% | 55% |

| 50-59 | 20% | 7% | 65% | 31% | 93% | 73% |

| 60-69 | 27% | 14% | 72% | 51% | 94% | 86% |

Importantly, prevalence of angiographically significant CAD in the Diamond-Forrester Classification, CASS Registry, and similar studies were derived from patient referred for invasive coronary angiography for clinical indications.2-5,10 These rates have not been tested in other populations. Recently, coronary CTA employing scanners with 64-detector rows has emerged as an accurate first-line method for noninvasively diagnosing angiographically significant CAD.11-14 Accordingly, we conducted a multicenter, multinational study to examine whether the reference values for pre-test probability as put forth by the ACC/AHA Clinical Practice Guidelines and Appropriate Use Criteria accurately predict the presence of angiographically significant CAD in patients referred for noninvasive imaging by coronary CTA.

Methods

Study Participants

CONFIRM (Coronary CT Angiography Evaluation For Clinical Outcomes: An International Multicenter Registry) is a dynamic multinational registry of consecutive patients enrolled at the time of clinically-indicated coronary CTA. Design of CONFIRM has been described.15 All patients gave informed consent for study participation, and each participating center obtained approval from an institutional review board or similar governing body (for centers outside of the United States) for study execution. Of the initial 12 participating centers in CONFIRM, 3 were excluded from this study due to absence of information necessary for categorizing angina typicality. The present study thus included patients from 9 centers in 6 countries: 1 each in Canada, Italy, South Korea, Switzerland, and Germany, and 4 in the United States. Of 19703 consecutive adult patients at these centers, we excluded, in sequential order, those with known coronary artery disease or suspected acute coronary syndrome at time of CTA (1994 patients), missing age information (7 patients), age < 30 years (286 patients), and incomplete symptom information (3368 patients). The remaining 14048 patients (71% of available population) were analyzed. All patients had standard CAD risk factor profile (presence of hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, active cigarette smoking, and family CAD history) and chest pain symptoms recorded at time of CTA.16

Chest pain categorization

Chest pain was categorized according to the classic criteria for angina pectoris.3,17,18 Patients with typical angina (TypAng) experienced: 1) substernal, jaw, and/or arm pressure-like pain that 2) consistently occurs with exertion and 3) consistently resolves within 15 minutes of rest and/or use of nitroglycerin. Patients with atypical angina (AtypAng) experienced 2 of these characteristics. Patients with nonanginal chest pain (NonAng) experienced 1 or none of these characteristics. Dyspneic patients whose primary symptom was chest pain were categorized as TypAng, AtypAng, or NonAng; otherwise, they were separately categorized as having dyspnea without chest pain (Dysp).19 Asymptomatic patients (Asymp) had neither chest pain nor dyspnea. At each site, symptom category was prospectively ascertained through written questionnaire or interview by a physician or allied health professional.

Determining Expected Probability of Angiographically Significant CAD

Age, sex, and angina typicality for each patient were used to determine the expected probability of CAD with ≥50% luminal diameter stenosis (CAD50) from the table of probabilities within the ACC/AHA Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Patients with Stable Angina (“Guideline Probabilities”, see Table 1).1 Patients >69 years old, whose pre-test CAD50 probability cannot be established from Guideline Probabilities, were assigned the pre-test probability for the corresponding 60-69 year-old group. We further accounted for presence of diabetes, smoking, and dyslipidemia by determining the expected probability of CAD with ≥70% luminal diameter stenosis (CAD70) using the algorithm developed by Pryor, et al.,4,5 assuming that all patients had normal resting electrocardiograms (data not available in CONFIRM). Patients >70 years old were assigned the expected pre-test CAD70 probability of a 70 year-old (maximum age in the algorithm by Pryor, et al.) with identical symptom category and CAD risk factor profile.

Coronary CTA Acquisition and Interpretation

CTA's were performed on a single-source 64-slice scanner (Lightspeed VCT, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI; SOMATOM Sensation 64, Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany) or a dual-source scanner (Definition or Flash, Siemens Medical Systems). Prior to imaging, in patients without contraindications, oral and/or intravenous metoprolol was administered in attempt to achieve a target heart rate ≤ 65 bpm for single-source scanners or ≤75 bpm for dual-source scanners. Whenever possible, 0.4 mg of sublingual nitroglycerin was administered 3-5 minutes prior to image acquisition. Timing bolus or automated bolus tracking at the proximal ascending aorta was used to determine time from contrast injection to optimal coronary artery enhancement. Eighty to 140 ml of contrast (depending on site) followed by 50 ml of saline flush was power-injected at 5-6 ml per second (rates > 6 ml/second was reserved for very obese patients or patients with very thick chests), and whole-volume image acquisition was completed in a single breath-hold. In 11727 patients (83% of total population) a noncontrast CT was also performed to quantify coronary calcium score, according to the method described by Agatston.20

Acquired image data were initially reconstructed in mid-diastole (always) and end-systole (if data were available). When image quality was suboptimal on initial reconstruction, multisector reconstruction algorithm and/or manual ECG editing were employed to improve image quality. Reconstructed data were then sent to a workstation, where a minimum of 1 highly experienced reader (who has interpreted ≥1000 prior coronary CTAs) employed all necessary post-processing techniques to determine the presence of CAD50 and CAD70 in any visible segment ≥1.5mm in diameter. CTA interpretation was performed in an intent-to-diagnose manner: any uninterpretable segment was scored the same stenosis severity as the most adjacent proximal evaluable segment, in accordance with standard protocols from prior multicenter studies.12,13 A 16-segment American Heart Association coronary artery tree model was employed.21 The severity of total detected CAD on each study was further categorized using a modified version of the Duke CAD Prognostic Index Score, as previously described.22,23 This “CAD Severity Score” ranged from 0 to 7: 0 = No visible coronary atherosclerosis; 1 = At least 1 segment with <50% stenosis; 2 = At least 2 segments (including a proximal segment) with <50% stenosis; 3 = At least 1 segment with 50-69% stenosis; 4 = At least 2 segments with 50-69% stenosis or at least 1 segment (not proximal LAD) with ≥70% stenosis; 5 = At least 3 segments with 50-69% stenosis or at least 2 segments (not proximal LAD) with ≥70% stenosis or proximal LAD with ≥70% stenosis; 6 = At least 3 segments with ≥70% stenosis or at least 2 segments (including proximal LAD) with ≥70% stenosis; 7 = left main coronary artery with ≥50% stenosis. Scores ≥5 represented high-risk disease.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were described as mean ± standard deviation or median with interquartile range. Frequencies of binary, categorical, and ordinal variables were described as percentages. Continuous variables with normal and non-normal distributions were compared using standard analysis-of-variance or the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test, respectively. To evaluate differences in prevalence of CAD50, prevalence of CAD70, rates of high-risk CAD (CAD Severity Score ≥5), and CAD Severity Scores between specific subpopulations, patients were stratified by sex, age, and symptom category in identical fashion to Guideline Probabilities. Asymp and NonAng served as references for other symptom categories. Comparisons of prevalence were performed with the chi-squared test. Comparisons of CAD Severity Scores were performed using the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test. Stepwise multivariable logistic regression analysis including age, sex, and presence of typical angina was performed to determine the association between each of these 3 variables and CAD50, CAD70 and high-risk CAD; these relationships were expressed as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). A p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

While prior studies have shown a general tendency for overestimating CAD stenosis severity by coronary CTA, it remained theoretically possible that for this study CTA underestimated prevalence of angiographically significant CAD due to nondiagnostic segments, severe coronary calcification, and general limitations in predictive value. In order to estimate the potential impact of these factors, we performed additional sensitivity analyses. To estimate the maximum potential difference in prevalence of angiographically significant CAD caused by nondiagnostic segments, we used results from 2 recent meta-analyses that showed a pooled false negative CAD50 rate of 4%.11,14 To estimate the maximum potential impact from coronary calcification, we evaluated data from the subset of 11727 patients for whom coronary calcium scores were available to calculate the maximum number of patients with missed CAD50, assuming that all patients with calcium scores >1000 possessed CAD50. We further repeated these analyses by assuming that all patients with a calcium scores >600 possessed CAD50. To estimate the impact of variations in coronary CTA predictive value, we calculated “true” CAD50 prevalence in scenarios where PPV ranged from 55% to 85% and NPV ranged from 85% to 95%. These calculations are summarized in Results, and details are shown in Supplemental Methods.

Results

There were 7719 men (mean age 57±11 years) and 6329 women (mean age 60±11 years) in the study population; of these, 4605 (60%) of the men and 4752 (75%) of the women were symptomatic. Characteristics of the study population are detailed in Table 2. The most common symptom type was AtypAng, reported by 57% of symptomatic men and 55% of symptomatic women. Multiple risk factors were present in just over half of the total population. For both sexes, patients with TypAng and Dysp were older and had higher rates of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and multiple risk factors.

Table 2.

| Table 2a. Demographic characteristics of men in the study population, categorized by angina typicality* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Total population n=7719 | Asymptomatic n=3114 | Nonanginal chest pain n=582 | Atypical angina n=2612 | Typical angina n=805 | Dyspnea only n=606 | p-value |

| Age (years) | 57 ± 11 | 57 ± 11 | 56 ± 12 | 55 ± 11 | 59 ± 12 | 60 ± 11 | <0.001 |

| Median age (interquartile) | 57 (49,65) | 58 (50,65) | 56 (47,65) | 55 (47,63) | 59 (51,67) | 60 (53,68) | <0.001 |

| 30-39 years-old | 513 (7%) | 160 (5%) | 44 (8%) | 248 (9%) | 40 (5%) | 21 (3%) | - |

| 40-49 years-old | 1583 (21%) | 584 (19%) | 147 (25%) | 627 (24%) | 137 (17%) | 88 (15%) | - |

| 50-59 years-old | 2410 (31%) | 1040 (33%) | 157 (27%) | 818 (31%) | 226 (28%) | 169 (28%) | - |

| 60-69 years-old | 2189 (28%) | 916 (29%) | 149 (26%) | 662 (25%) | 253 (31%) | 209 (34%) | - |

| 70+ years-old | 1024 (13%) | 414 (13%) | 85 (15%) | 257 (10%) | 149 (19%) | 119 (20%) | - |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.4 ± 4.5 | 27.0 ± 4.1 | 28.0 ± 4.7 | 27.1 ± 4.4 | 27.6 ± 4.6 | 29.2 ± 5.7 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 13% | 12% | 13% | 13% | 15% | 18% | 0.002 |

| Hypertension | 47% | 42% | 48% | 47% | 57% | 57% | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 58% | 58% | 52% | 57% | 63% | 58% | 0.003 |

| Active Smoking | 18% | 14% | 25% | 19% | 21% | 17% | <0.001 |

| Family CAD history | 29% | 29% | 35% | 26% | 32% | 30% | <0.001 |

| 2 or more risk factors | 53% | 49% | 57% | 52% | 62% | 58% | <0.001 |

| Table 2B. Demographic characteristics of women in the study population, categorized by angina typicality* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Total population n=6329 | Asymptomatic n=1577 | Nonanginal chest pain n=671 | Atypical angina n=2611 | Typical angina n=825 | Dyspnea only n=645 | p-value |

| Age (years) | 60 ± 11 | 60 ± 11 | 60 ± 12 | 59 ± 11 | 61 ± 11 | 62 ± 12 | <0.001 |

| Median age (interquartile) | 60 (52,67) | 60 (53,67) | 60 (51,69) | 59 (51,66) | 61 (54,70) | 63 (54,70) | <0.001 |

| 30-39 years-old | 247 (4%) | 47 (3%) | 35 (5%) | 125 (5%) | 21 (3%) | 19 (3%) | |

| 40-49 years-old | 915 (14%) | 211 (13%) | 111 (17%) | 424 (16%) | 99 (12%) | 70 (11%) | |

| 50-59 years-old | 1885 (30%) | 497 (32%) | 168 (25%) | 813 (31%) | 239 (29%) | 168 (26%) | |

| 60-69 years-old | 2035 (32%) | 527 (33%) | 201 (30%) | 836 (32%) | 254 (31%) | 217 (34%) | |

| 70+ years-old | 1247 (20%) | 295 (19%) | 156 (23%) | 413 (16%) | 212 (26%) | 171 (27%) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.2 ± 6.1 | 26.2 ± 5.4 | 28.2 ± 7.0 | 27.2 ± 5.8 | 27.3 ± 5.8 | 28.9 ± 7.3 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 14% | 13% | 13% | 14% | 15% | 16% | 0.162 |

| Hypertension | 53% | 49% | 53% | 53% | 58% | 60% | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 58% | 56% | 54% | 58% | 64% | 59% | <0.001 |

| Active Smoking | 12% | 11% | 16% | 12% | 12% | 11% | 0.004 |

| Family CAD history | 32% | 27% | 45% | 29% | 40% | 33% | <0.001 |

| 2 or more risk factors | 54% | 49% | 60% | 53% | 62% | 57% | <0.001 |

CAD = coronary artery disease

In each main column, the left sub-column shows count or mean value, and right sub-column shows corresponding percentage (in parentheses) or standard deviation (after ±)

Prevalence of Angiographically Significant CAD

The overall prevalence of CAD50 in our study population was 18% (23% in men, 13% in women), and 10% of patients had CAD70 (12% of men, 6% of women). Of the 3368 ≥30 year-old patients without prior CAD excluded from analysis due to incomplete symptom data, stenosis information was available in 2576 patients; prevalence of CAD50 and CAD70 in this group were 20% (24% in men, 14% in women) and 9% (12% in men, 5% in women), respectively.

For all symptom categories, prevalence of CAD50 and CAD70 were significantly higher in men than in women (p<0.001 for all comparisons, Table 3). In both men and women, the highest prevalence were found in patients with TypAng (p<0.001 when compared to all other symptom categories).

Table 3. Observed prevalence and severity of angiographically significant CAD according to symptom category.

| MEN | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Asymptomatic | Nonanginal chest pain | Atypical angina | Typical angina | Dyspnea | p-value† | |

| Number of patients | 7719 | 3114 | 582 | 2612 | 805 | 604 | |

| CAD50* | 23% | 21% | 25% | 19% | 40% | 29% | <0.001 |

| CAD70* | 12% | 10% | 17% | 9% | 27% | 16% | <0.001 |

| Mean CAD Severity Score* | 1.7±1.8 | 1.6±1.6 | 1.8±1.9 | 1.4±1.7 | 2.4±2.1 | 2.1±1.8 | <0.001 |

| CAD Severity Score ≥5* | 10% | 7% | 13% | 8% | 21% | 12% | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| WOMEN | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Overall | Asymptomatic | Nonanginal chest pain | Atypical angina | Typical angina | Dyspnea | p-value† | |

| Number of patients | 6329 | 1577 | 671 | 2611 | 825 | 645 | |

| CAD50 | 13% | 13% | 12% | 11% | 19% | 13% | <0.001 |

| CAD70 | 6% | 6% | 7% | 5% | 11% | 6% | <0.001 |

| Mean CAD Severity Score* | 1.0±1.5 | 1.1±1.5 | 1.1±1.5 | 0.9±1.4 | 1.3±1.7 | 1.2±1.4 | <0.001 |

| CAD Severity Score ≥5* | 4% | 5% | 4% | 3% | 8% | 4% | <0.001 |

CAD50 = ≥50% diameter diameter stenotic coronary artery disease; CAD70 = ≥70% diameter diameter stenotic coronary artery disease

CAD50 prevalence, CAD70 prevalence, mean CAD Severity Score, and frequency of CAD Severity Score ≥5 in men were higher than in women for every symptom category (all p's<0.001)

Compares trend in observed stenotic CAD prevalence and measures of CAD severity across all symptom categories

Table 4 shows prevalence of CAD50 and CAD70 in subgroups determined by age, sex, and symptom category, employing the same stratification scheme as Guideline Probabilities. Prevalence for every symptom category increased with age. In ≥40 years-olds (both men and women), only patients with TypAng exhibited higher prevalence of CAD50 and CAD70 than patients with Asymp and NonAng for each increasing age decade. The highest observed CAD50 prevalence was 53%, in men ≥70 years of age with TypAng. In patients <40 years old, symptom category showed no relationship to the prevalence of CAD50 or CAD70. Stepwise multivariable logistic regression confirmed that age, male sex, and prevalence of TypAng were all independently associated with CAD50 and CAD 70 (per increase in decade age: OR 1.82, 95%CI 1.74-1.91 for CAD50, OR 1.81, 95%CI 1.71-1.92 for CAD70; male sex, OR 2.62, 95%CI 2.38-2.89 for CAD50, OR 2.63, 95%CI 2.36-3.05 for CAD70; presence of TypAng, OR 1.95, 95%CI 1.73-2.21 for CAD50, OR 2.55 95%CI 2.21-2.95 for CAD70).

Table 4. Observed prevalence of CAD50 and CAD70 in the study population, stratified by sex, age, and symptom category.

| MEN | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAD50 | CAD70 | |||||||||||

| Age (y) | Asymptomatic | Non-anginal | Atypical angina | Typical angina | Dyspnea | p-value* | Asymptomatic | Non-anginal | Atypical angina | Typical angina | Dyspnea | p-value* |

| 30-39 | 1% | 5% | 4% | 3% | 0% | 0.312 | 0% | 5% | 1% | 3% | 0% | 0.134 |

| 40-49 | 8% | 7% | 10% | 23% | 14% | <0.001 | 3% | 3% | 5% | 16% | 8% | <0.001 |

| 50-59 | 20% | 22% | 18% | 38% | 22% | <0.001 | 8% | 13% | 7% | 28% | 11% | <0.001 |

| 60-69 | 27% | 43% | 28% | 48% | 34% | <0.001 | 13% | 30% | 13% | 31% | 15% | <0.001 |

| 70+ | 36% | 44% | 39% | 53% | 45% | 0.005 | 19% | 29% | 21% | 35% | 31% | 0.001 |

| p-value† | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| WOMEN | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| CAD50 | CAD70 | |||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Age (y) | Asymptomatic | Non-anginal | Atypical angina | Typical angina | Dyspnea | p-value* | Asymptomatic | Non-anginal | Atypical angina | Typical angina | Dyspnea | p-value* |

| 30-39 | 4% | 3% | 3% | 5% | 5% | 0.983 | 0% | 0% | 2% | 0% | 5% | 0.404 |

| 40-49 | 2% | 5% | 6% | 10% | 4% | 0.077 | 1% | 2% | 2% | 7% | 4% | 0.008 |

| 50-59 | 9% | 9% | 7% | 15% | 10% | 0.004 | 3% | 7% | 3% | 10% | 3% | <0.001 |

| 60-69 | 13% | 13% | 12% | 19% | 16% | 0.095 | 6% | 7% | 5% | 9% | 6% | 0.240 |

| 70+ | 28% | 21% | 23% | 29% | 19% | 0.086 | 14% | 12% | 13% | 19% | 11% | 0.148 |

| p-value† | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.012 | <0.001 | 0.013 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.029 | ||

CAD50 = ≥50% diameter stenotic coronary artery disease; CAD70 = ≥70% diameter stenotic coronary artery disease

Compares trend in observed prevalence of CAD50 and CAD70 across all symptom categories

Compares trend in observed prevalence across all decades of age

CAD Severity

As shown in Table 3, CAD Severity Scores were higher in men than women for every symptom category. The highest scores for both sexes were found in patients with TypAng. Mean CAD Severity Scores and rates of high-risk CAD (score ≥5) increased with age decade (all p values for trend <0.001; see Table 5). Patients ≥70 years of age with TypAng had the highest subgroup CAD Severity Score and prevalence of high-risk CAD (3.2±2.1 and 30%, respectively for men; 2.0±1.8 and 13%, respectively for women). Stepwise multivariable logistic regression confirmed that age (per increase in decade: OR 1.82, 95%CI 1.70-1.94), male sex (OR 2.98, 95%CI 2.57-3.45), and presence of TypAng (OR 2.45, 95%CI 2.08-2.88) were independently associated with high-risk CAD.

Table 5. Observed mean CAD Severity Score and prevalence of severe CAD, defined as a Score≥5, stratified by sex, age, and symptom category.

| MEN | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asymptomatic | Nonanginal chest pain | Atypical angina | Typical angina | Dyspnea | p-value* | |||||||

| Age (y) | Mean Score | Score≥5 | Mean Score | Score≥5 | Mean Score | Score≥5 | Mean Score | Score≥5 | Mean Score | Score≥5 | Mean Score | Score≥5 |

| 30-39 | 0.2±0.6 | 0% | 0.5±1.3 | 5% | 0.3±0.8 | 1% | 0.4±0.9 | 3% | 0.3±0.6 | 0% | 0.795 | 0.071 |

| 40-49 | 0.8±1.2 | 2% | 0.8±1.2 | 2% | 0.8±1.4 | 4% | 1.4±2.1 | 13% | 1.1±1.5 | 5% | 0.102 | <0.001 |

| 50-59 | 1.5±1.5 | 6% | 1.8±1.7 | 8% | 1.4±1.6 | 6% | 2.3±2.2 | 22% | 1.9±1.8 | 11% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 60-69 | 2.0±1.6 | 9% | 2.7±1.9 | 21% | 2.0±1.8 | 13% | 2.7±2.0 | 22% | 2.4±1.6 | 12% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 70+ | 2.4±1.7 | 15% | 2.8±2.1 | 28% | 2.6±1.9 | 20% | 3.2±2.1 | 30% | 2.8±1.7 | 20% | 0.003 | 0.001 |

| p-value† | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.004 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| WOMEN | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Asymptomatic | Nonanginal chest pain | Atypical angina | Typical angina | Dyspnea | p-value* | |||||||

| Age (y) | Mean Score | Score≥5 | Mean Score | Score≥5 | Mean Score | Score≥5 | Mean Score | Score≥5 | Mean Score | Score≥5 | Mean Score | Score≥5 |

| 30-39 | 0.2±0.7 | 0% | 0.2±0.6 | 0% | 0.2±0.9 | 2% | 0.2±0.9 | 0% | 0.3±1.2 | 5% | 0.952 | 0.404 |

| 40-49 | 0.3±0.8 | 0% | 0.4±0.9 | 0% | 0.4±1.0 | 1% | 0.7±1.5 | 6% | 0.5±1.2 | 3% | 0.442 | <0.001 |

| 50-59 | 0.7±1.2 | 2% | 0.9±1.4 | 5% | 0.6±1.1 | 1% | 1.1±1.7 | 6% | 0.8±1.3 | 3% | 0.012 | <0.001 |

| 60-69 | 1.2±1.6 | 6% | 1.2±1.4 | 3% | 1.1±1.5 | 4% | 1.3±1.6 | 7% | 1.3±1.5 | 3% | 0.008 | 0.115 |

| 70+ | 2.0±1.7 | 11% | 1.8±1.7 | 10% | 1.8±1.6 | 7% | 2.0±1.8 | 13% | 1.7±1.5 | 5% | 0.212 | 0.018 |

| p-value† | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.033 | <0.001 | 0.891 | ||

Compares trend in observed values across all symptom categories

Compares trend in observed values across all age categories

Comparisons of Observed Angiographically Significant CAD Prevalence to Expected Prevalence by Guideline Probabilities

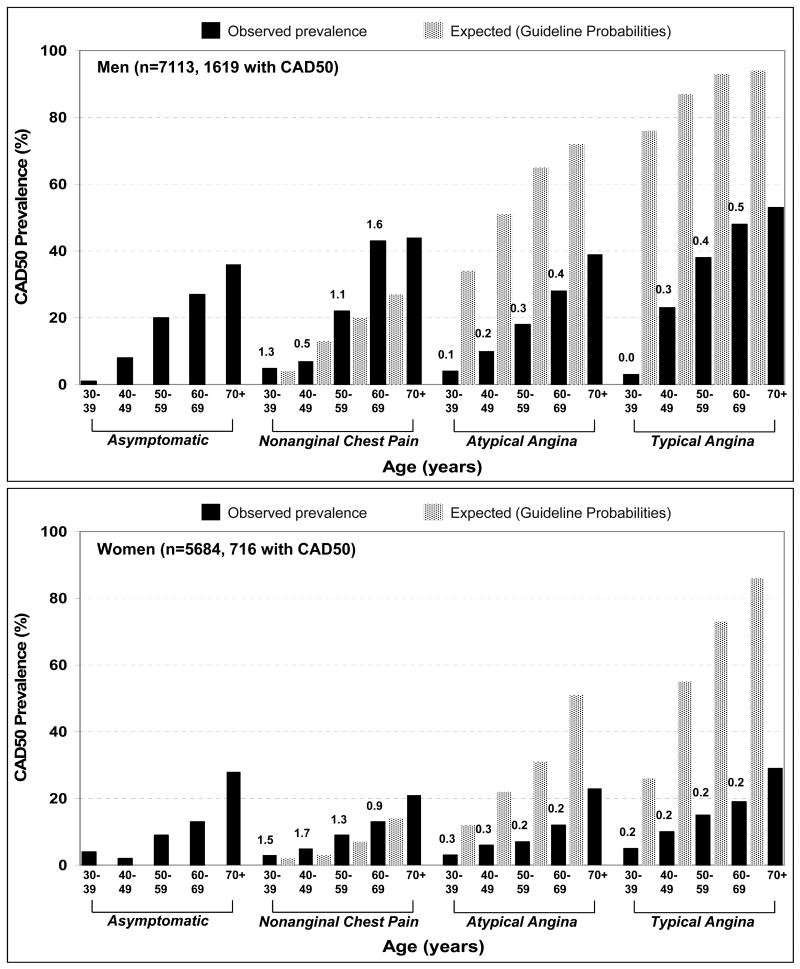

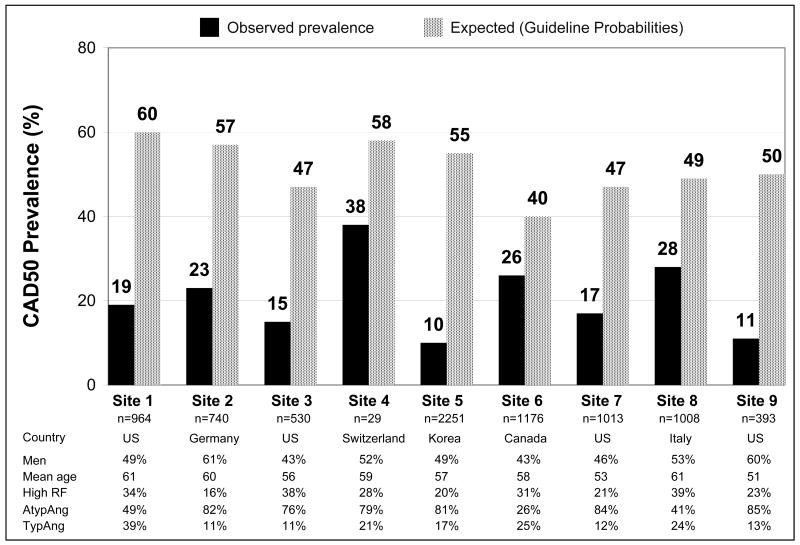

Comparisons of observed and expected CAD50 and CAD70 prevalence were made for the 8106 patients who reported NonAng, AtypAng, and TypAng. For CAD50, overall observed prevalence was substantially lower than expected (18% vs, 51%, p<0.001). This difference was present for both men (24% vs. 61%, p<0.001) and women (13% vs. 41%, p<0.001). For both sexes, the differences in observed and expected CAD50 prevalence were most marked in patients with AtypAng and TypAng, across all age groups (Figure 1). Within the AtypAng and TypAng populations, observed-to-expected ratios increased with age in men (p<0.001 for both) but not in women. As shown in Figure 2, observed CAD50 prevalence was lower than expected prevalence at every participating site (range of observed-to-expected ratio: 0.18 to 0.66).

Figure 1.

Observed prevalence (black bars) and expected prevalence (spotted bars) of angiographically ≥50% stenotic coronary artery disease (CAD50) in study men (top graph) and women (bottom graph) with no symptoms, nonanginal chest pain, atypical angina, and typical angina. Note that the total sample sizes shown are smaller than those in Table 1 because patients reporting only dyspnea are not included. The 4 collections of bars in each graph are grouped by symptom category and stratified by age decade. Within each symptom group, each black bar should be compared to the spotted bar to its immediate right (asymptomatic patients have no direct comparison). The value above each black bar is the ratio of observed-to-expected CAD50 prevalence. Expected prevalence in patients with atypical angina and typical angina were dramatically higher than observed prevalence, regardless of age. With increasing age, observed-to-expected ratios increased in men with atypical angina (p<0.001) and typical angina (p<0.001) but stayed unchanged in women.

Figure 2.

Overall observed prevalence (black bars) of angiographically ≥50% stenotic coronary artery disease (CAD50) was substantially lower than expected prevalence (spotted bars) at every participating center. The observed-to-expected ratios ranged from 0.18 (Site 5) to 0.66 (Site 4), and absolute differences between observed and expected prevalence ranged from 14% to 45%. The 2 sites with the lowest observed-to-expected ratios were Site 5 and Site 9. Site 5 was in South Korea, the only center outside of North America and Europe. Patients at Site 9 were substantially younger than patients at other sites. The 2 sites with the highest observed-to-expected ratios were Site 6 and Site 8 (Site 4 discounted due to very small sample size). Populations at both sites had relatively low rates of atypical angina and relatively high rates of typical angina. Site 8 patients also had the highest rate of patients with high risk factor burden (diabetes or ≥3 non-diabetes risk factors). RF = risk factor.

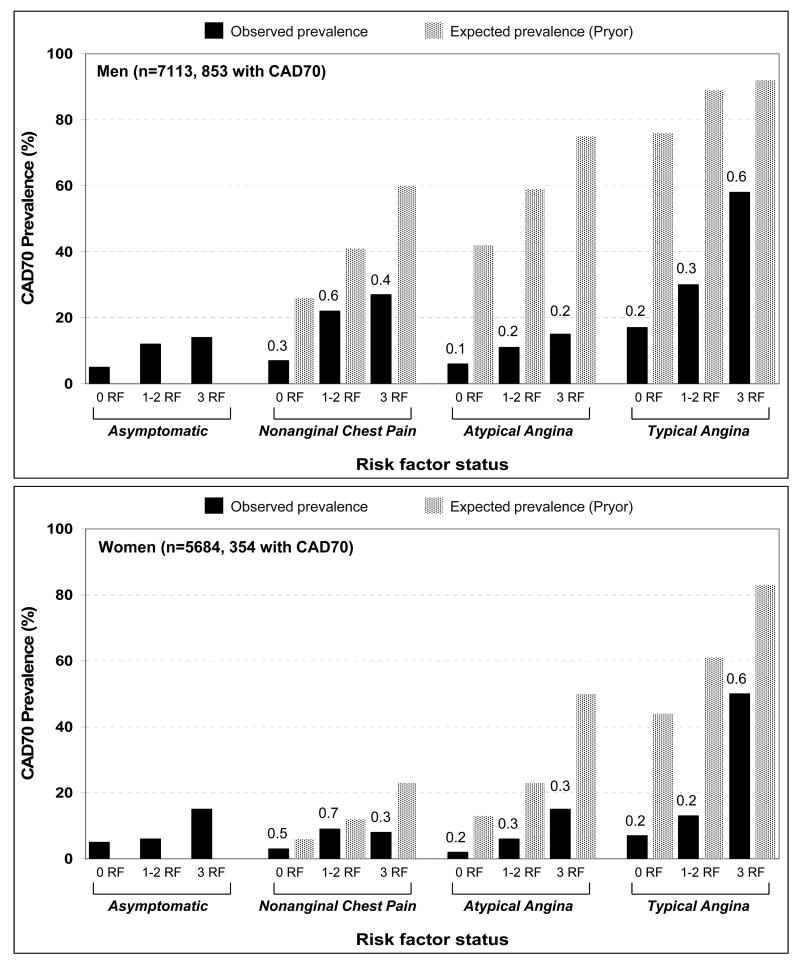

Observed CAD70 prevalence was also substantially lower than expected (overall 10% vs. 42%, men 14% vs. 58%, women 6% vs. 26%, all p values <0.001). As shown in Figure 3, this difference was present regardless of number of risk factors and, similar to CAD50, were most pronounced in patients with AtypAng and TypAng.

Figure 3.

Observed prevalence (black bars) and expected prevalence (spotted bars) of angiographically ≥70% stenotic coronary artery disease (CAD70) in study men (top graph) and women (bottom graph). Expected prevalence was calculated using the algorithm described by Pryor and colleagues, which incorporates sex, age, angina typicality, history of prior myocardial infarction, presence of Q-waves on resting ECG, and presence of 3 risk factors: diabetes, dyslipidemia, and active smoking.4 Study patients were assumed to have no Q-waves on resting ECG. Within each symptom category, patients were subgrouped by number of risk factors. The value above each black bar is the ratio of observed-to-expected prevalence. In all groups, expected prevalence was higher than observed prevalence. The differences were particularly dramatic in patients with atypical angina or typical angina and <3 risk factors, where observed-to-expected ratios were <0.4. RF = risk factor.

Impact of Nondiagnostic Segments, Coronary Calcification, and Variations in CTA Predictive Value on Observed Prevalence of Angiographically Significant CAD

Additional models were constructed to determine the potential impact of known factors that may affect coronary CTA diagnostic accuracy, including non-diagnostic coronary segments, severe coronary calcification, and from potential differences in “real world” predictive values as compared to those previously reported in prospective multicenter trials. Simulation of the “worst-case scenarios” based on these factors estimated the minimum and maximum potential CAD50 prevalence at 14% and 28%. Details of these models and corresponding calculations are shown in Supplemental Methods.

Discussion

In this large prospective multinational study of asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with suspected CAD undergoing noninvasive evaluation by coronary CTA, expected prevalence of angiographically significant CAD based on Guideline Probabilities significantly exceeded actual observed prevalence. Predicted rates of were approximately 3-fold higher than actual observed prevalence for CAD50 (51% vs. 18%) and 4-fold higher for CAD70 (42% vs. 10%), with consistent overestimation of CAD prevalence whether using the method of Diamond-Forrester and CASS (restricting pre-test probability determination to age, gender and angina typicality) or the method of Pryor (additionally accounting for CAD risk factors).2-5 The differences were most pronounced for men and women across all age groups presenting with AtypAng and TypAng, with TypAng as the only chest pain categorization that reliably predicted greater prevalence of angiographically significant CAD.

The present results are in accordance with three contemporary studies that have identified a systematic overestimation of angiographically significant CAD among patients referred for invasive angiography. Hoilund-Carlsen, et al. found absence of CAD50 in 97 (52%) of 187 men and women with TypAng and a mean age of 58 years.24 Guideline Probabilities predicted >80% prevalence in this population, leading the authors to conclude that clinical prediction was unreliable. Patel, et al., in over 130,000 patients with TypAng from the American College of Cardiology National Cardiovascular Data Registry, observed an overall CAD50 prevalence of 50%. In the same study, in over 145,000 patients with NonAng and AtypAng, CAD50 prevalence was only 25%.25 A recent multicenter effort by Genders, et al. found overestimation of CAD50 by the Diamond-Forrester Classification in patients with TypAng, especially women.26 Our work extends the results of these studies by directly demonstrating that the application of data from invasive angiography dramatically overestimates the pre-test likelihood of angiographically significant CAD in symptomatic patients referred for noninvasive CAD evaluation.

Of the multiple potential explanations for the extent to which Guideline Probabilities overestimated actual prevalence of angiographically significant CAD in study patients with chest pain, three emerge as particularly strong candidates. First, Guideline Probabilities were developed from historical studies that evaluated patients undergoing clinically-indicated invasive angiography, frequently after abnormal results from stress testing.2,27-34 Bayesian principles dictate that the population being referred for invasive angiography will have higher disease prevalence when compared to populations referred for de novo noninvasive testing. Indeed, in the present study, coronary CTA was generally employed for patients at low-to-intermediate pre-test likelihood of angiographic-significant CAD, in accordance with recommendation of societal practice guidelines and appropriate use criteria.8 For patients with a very high pre-test likelihood, clinicians may have opted for referral to invasive angiography in lieu of noninvasive testing. Second, the technique of determining chest pain quality and angina typicality differed between the present study and the source data for Guideline Probabilities. In the present study, angina typicality was assessed in rank order fashion using responses to several fixed questions designed to replicate the criteria used by Guideline Probabilities. However, multiple source studies for Guideline Probabilities used physician-conducted interviews or detailed chart reviews.2,27-34 Ascertainment of angina typicality by the latter approach may have been influenced by presence of other potentially relevant features, such as chest pain frequency, severity, associated degree of functional impairment, and competing diagnoses. Finally, an increasing emphasis in developed countries by media, physicians, and insurers on preventive care for CAD over the past 2 decades has increased awareness of the potential hazards of CAD; these efforts may be prompting lower-risk symptomatic patients to seek earlier diagnostic evaluation for CAD.

Several additional findings in the present study are worthy of discussion. Ratios of observed-to-expected CAD50 prevalence increased with age in men but not in women, highlighting the overall reduced performance of Guideline Probabilities in women and the need for sex-specific prediction models. The lowest observed-to-expected ratio was found at the South Korean site, suggesting that the relationship between angina typicality and angiographically significant CAD may be influenced by ethnicity or local interpretation of chest pain characteristics. Differences in prevalence among asymptomatic patients and patients with nonanginal chest pain and atypical angina were generally small, echoing a phenomenon recently reported by Patel and colleagues, who found that patients with “atypical chest pain” actually exhibited lower rates of angiographically significant CAD than patients with no chest pain.25 In the present study, this finding may have been due to referral pattern, as fewer asymptomatic patients were <50 years old (Table 2). Compared to asymptomatic patients and patients with atypical angina, patients with nonanginal chest pain had the highest absolute prevalence of CAD50, CAD70, and high-risk CAD. This may have been related to differences in underlying risk factor burden, as patients with nonanginal chest pain in our population also reported higher rates of active smoking, family CAD history, and multiple concurrent risk factors.

The results from the present study carry significant clinical implications. An estimated 10 million noninvasive cardiac imaging tests are performed annually in the United States.35 This volume accounts for a large portion of national healthcare expenditure and has raised concerns regarding the overuse and economic efficiency of noninvasive imaging. Due to the absence of updated prediction models for first-line evaluation of symptomatic patients with suspected CAD, professional societal recommendations that guide referral to noninvasive testing have depended on Guideline Probabilities. Our analyses uniformly illustrate that the utility of Guideline Probabilities is limited by overestimation of pre-test probability. This limitation is likely magnified in populations for whom noninvasive testing is the next preferred diagnostic step. Findings from our study suggest that successfully updating pre-test probability estimates of CAD in populations similar to CONFIRM may identify a large percentage of low- or intermediate-likelihood patients in whom additional testing may not be warranted.

Study Limitations

Results in this study are predicated upon an accurate exclusion of CAD50 by coronary CTA. Compared to invasive angiography, 64-detector row coronary CTA has consistently exhibited very high negative predictive value (NPV) for exclusion of angiographically significant CAD. Two recent meta-analyses and two other recent rigorously-conducted multi-center studies all found ≥95% NPV on a per-patient basis.11-14 The major diagnostic limitation of CTA in individuals without known CAD has been positive predictive value (PPV), reported at 60-70% in recent multi-center studies.12,13 In models adjusting for the spectrum of plausible NPV (85-95%) and PPV (55-85%), the maximum potential CAD50 prevalence of our study population was 28% (range 14%-28%, Supplemental Methods). Even with these conservative assumptions, overestimation of CAD50 prevalence in the CONFIRM population by Guideline Probabilities remains quite striking.

We examined asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with suspected CAD to provide estimates of angiographically significant CAD prevalence. While our reported prevalence values may be useful starting points for considering the utility of noninvasive CAD testing, angina typicality was determined through questionnaire rather than physician interview in a large number cases, and other commonly-obtained clinical data, such as duration and severity of chest pain and resting ECG, were not available. In addition, reasons for coronary CTA in asymptomatic patients were not available, and referral patterns within the present study were likely biased against patients with symptoms severe enough to warrant direct referral to invasive coronary angiography. Thus, application of our findings to patients undergoing invasive evaluation must be performed with caution.

Interpretation of coronary CTA was not blinded to available clinical data. However, these studies were meticulously evaluated by Level III-equivalent readers with >1000 prior CTA interpretations and in direct accordance to Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography guidelines.36 While unlikely, the open-label nature of the present study may have theoretically biased readers towards overestimating CAD50 and CAD70 in patients with TypAng. Nevertheless, if true, this bias would naturally magnify the discrepancy we found between Guideline Probabilities and observed angiographic-significant CAD prevalence in patients with TypAng.

The intent-to-diagnose approach to CTA interpretation in CONFIRM did not account for potential inaccuracies from uninterpretable segments and coronary calcification. In all sensitivity analyses we performed to account for these factors, marked overestimation of angiographically significant CAD by Guideline Probabilities persisted (Supplemental Methods).

Conclusions

In this contemporary multinational study of patients with suspected CAD referred for noninvasive evaluation by coronary CTA, determination of pre-test likelihood of angiographically significant CAD by the invasive angiography-based Guideline Probabilities greatly overestimates the actual observed prevalence of disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Victor Y. Cheng receives funding from the National Institutes of Health (National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, 1K23HL107458-01).

Footnotes

Disclosures and Potential Conflicts of Interest: Stephan Achenbach has received grant support from Siemens and Bayer Schering. Matthew J. Budoff has received speaker honoraria from GE Healthcare. Filippo Cademartiri has received grant support from GE Healthcare and speaker honoraria from Bracco Diagnostics. Benjamin J.W. Chow has received research support from GE Healthcare, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca and educational support from TeraRecon. Jörg Hausleiter has received research grant support from Siemens. Philipp Kaufmann has received research support from GE Healthcare and grant support from the Swiss National Science Foundation. Erica Maffei has received grant support from GE Healthcare. Gilbert L. Raff has received grant support from Siemens, Blue Cross Blue Shield Blue Care (Michigan), and Bayer. Leslee J. Shaw has received research grant support from Bracco Diagnostics and CV Therapeutics. James K. Min has received speaker honoraria and research support from GE Healthcare and serves on the medical advisory board for GE Healthcare.

References

- 1.Gibbons RJ, Abrams J, Chatterjee K, Daley J, Deedwania PC, Douglas JS, Ferguson TB, Jr, Fihn SD, Fraker TD, Jr, Gardin JM, O'Rourke RA, Pasternak RC, Williams SV, Gibbons RJ, Alpert JS, Antman EM, Hiratzka LF, Fuster V, Faxon DP, Gregoratos G, Jacobs AK, Smith SC., Jr ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for the management of patients with chronic stable angina--summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients With Chronic Stable Angina) Circulation. 2003;107:149–58. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000047041.66447.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaitman BR, Bourassa MG, Davis K, Rogers WJ, Tyras DH, Berger R, Kennedy JW, Fisher L, Judkins MP, Mock MB, Killip T. Angiographic prevalence of high-risk coronary artery disease in patient subsets (CASS) Circulation. 1981;64:360–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.64.2.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diamond GA, Forrester JS. Analysis of probability as an aid in the clinical diagnosis of coronary-artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1350–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197906143002402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pryor DB, Harrell FE, Jr, Lee KL, Califf RM, Rosati RA. Estimating the likelihood of significant coronary artery disease. Am J Med. 1983;75:771–80. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)90406-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pryor DB, Shaw L, McCants CB, Lee KL, Mark DB, Harrell FE, Jr, Muhlbaier LH, Califf RM. Value of the history and physical in identifying patients at increased risk for coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:81–90. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-2-199301150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hendel RC, Patel MR, Kramer CM, Poon M, Hendel RC, Carr JC, Gerstad NA, Gillam LD, Hodgson JM, Kim RJ, Kramer CM, Lesser JR, Martin ET, Messer JV, Redberg RF, Rubin GD, Rumsfeld JS, Taylor AJ, Weigold WG, Woodard PK, Brindis RG, Hendel RC, Douglas PS, Peterson ED, Wolk MJ, Allen JM, Patel MR. ACCF/ACR/SCCT/SCMR/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SIR 2006 appropriateness criteria for cardiac computed tomography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Quality Strategic Directions Committee Appropriateness Criteria Working Group, American College of Radiology, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, North American Society for Cardiac Imaging, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Interventional Radiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1475–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hendel RC, Berman DS, Di Carli MF, Heidenreich PA, Henkin RE, Pellikka PA, Pohost GM, Williams KA. ACCF/ASNC/ACR/AHA/ASE/SCCT/SCMR/SNM 2009 Appropriate Use Criteria for Cardiac Radionuclide Imaging: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the American College of Radiology, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and the Society of Nuclear Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:2201–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor AJ, Cerqueira M, Hodgson JM, Mark D, Min J, O'Gara P, Rubin GD, Kramer CM, Berman D, Brown A, Chaudhry FA, Cury RC, Desai MY, Einstein AJ, Gomes AS, Harrington R, Hoffmann U, Khare R, Lesser J, McGann C, Rosenberg A, Schwartz R, Shelton M, Smetana GW, Smith SC., Jr ACCF/SCCT/ACR/AHA/ASE/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SCMR 2010 appropriate use criteria for cardiac computed tomography: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, the American College of Radiology, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1864–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douglas PS, Garcia MJ, Haines DE, Lai WW, Manning WJ, Patel AR, Picard MH, Polk DM, Ragosta M, Ward RP, Weiner RB. ACCF/ASE/AHA/ASNC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCM/SCCT/SCMR 2011 Appropriate Use Criteria for Echocardiography A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Society of Echocardiography, American Heart Association, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Endorsed by the American College of Chest Physicians. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1126–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pryor DB, Shaw L, Harrell FE, Jr, Lee KL, Hlatky MA, Mark DB, Muhlbaier LH, Califf RM. Estimating the likelihood of severe coronary artery disease. Am J Med. 1991;90:553–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdulla J, Abildstrom SZ, Gotzsche O, Christensen E, Kober L, Torp-Pedersen C. 64-multislice detector computed tomography coronary angiography as potential alternative to conventional coronary angiography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:3042–50. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Budoff MJ, Dowe D, Jollis JG, Gitter M, Sutherland J, Halamert E, Scherer M, Bellinger R, Martin A, Benton R, Delago A, Min JK. Diagnostic performance of 64-multidetector row coronary computed tomographic angiography for evaluation of coronary artery stenosis in individuals without known coronary artery disease: results from the prospective multicenter ACCURACY (Assessment by Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography of Individuals Undergoing Invasive Coronary Angiography) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1724–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meijboom WB, Meijs MF, Schuijf JD, Cramer MJ, Mollet NR, van Mieghem CA, Nieman K, van Werkhoven JM, Pundziute G, Weustink AC, de Vos AM, Pugliese F, Rensing B, Jukema JW, Bax JJ, Prokop M, Doevendans PA, Hunink MG, Krestin GP, de Feyter PJ. Diagnostic accuracy of 64-slice computed tomography coronary angiography: a prospective, multicenter, multivendor study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:2135–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun Z, Lin C, Davidson R, Dong C, Liao Y. Diagnostic value of 64-slice CT angiography in coronary artery disease: a systematic review. Eur J Radiol. 2008;67:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Min JK, Dunning A, Lin FY, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah MH, Berman DS, Budoff MJ, Cademartiri F, Callister TQ, Chang HJ, Cheng V, Chinnaiyan KM, Chow B, Delago A, Hadamitzky M, Hausleiter J, Karlsberg RP, Kaufmann P, Maffei E, Nasir K, Pencina MJ, Raff GL, Shaw LJ, Villines TC. Rationale and design of the CONFIRM (COronary CT Angiography EvaluatioN For Clinical Outcomes: An InteRnational Multicenter) Registry. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2011;5:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Jama. 2001;285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Detrano R, Yiannikas J, Salcedo EE, Rincon G, Go RT, Williams G, Leatherman J. Bayesian probability analysis: a prospective demonstration of its clinical utility in diagnosing coronary disease. Circulation. 1984;69:541–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.69.3.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sangareddi V, Chockalingam A, Gnanavelu G, Subramaniam T, Jagannathan V, Elangovan S. Canadian Cardiovascular Society classification of effort angina: an angiographic correlation. Coron Artery Dis. 2004;15:111–4. doi: 10.1097/00019501-200403000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abidov A, Rozanski A, Hachamovitch R, Hayes SW, Aboul-Enein F, Cohen I, Friedman JD, Germano G, Berman DS. Prognostic significance of dyspnea in patients referred for cardiac stress testing. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1889–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M, Jr, Detrano R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:827–32. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Austen WG, Edwards JE, Frye RL, Gensini GG, Gott VL, Griffith LS, McGoon DC, Murphy ML, Roe BB. A reporting system on patients evaluated for coronary artery disease. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee for Grading of Coronary Artery Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1975;51:5–40. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.51.4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mark DB, Nelson CL, Califf RM, Harrell FE, Jr, Lee KL, Jones RH, Fortin DF, Stack RS, Glower DD, Smith LR. Continuing evolution of therapy for coronary artery disease. Initial results from the era of coronary angioplasty. Circulation. 1994;89:2015–25. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.5.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Min JK, Shaw LJ, Devereux RB, Okin PM, Weinsaft JW, Russo DJ, Lippolis NJ, Berman DS, Callister TQ. Prognostic value of multidetector coronary computed tomographic angiography for prediction of all-cause mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1161–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoilund-Carlsen PF, Johansen A, Vach W, Christensen HW, Moldrup M, Haghfelt T. High probability of disease in angina pectoris patients: is clinical estimation reliable? Can J Cardiol. 2007;23:641–7. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(07)70226-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel MR, Peterson ED, Dai D, Brennan JM, Redberg RF, Anderson HV, Brindis RG, Douglas PS. Low diagnostic yield of elective coronary angiography. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:886–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Genders TS, Steyerberg EW, Alkadhi H, Leschka S, Desbiolles L, Nieman K, Galema TW, Meijboom WB, Mollet NR, de Feyter PJ, Cademartiri F, Maffei E, Dewey M, Zimmermann E, Laule M, Pugliese F, Barbagallo R, Sinitsyn V, Bogaert J, Goetschalckx K, Schoepf UJ, Rowe GW, Schuijf JD, Bax JJ, de Graaf FR, Knuuti J, Kajander S, van Mieghem CA, Meijs MF, Cramer MJ, Gopalan D, Feuchtner G, Friedrich G, Krestin GP, Hunink MG. A clinical prediction rule for the diagnosis of coronary artery disease: validation, updating, and extension. Eur Heart J. 2011 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartel AG, Behar VS, Peter RH, Orgain ES, Kong Y. Graded exercise stress tests in angiographically documented coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1974;49:348–56. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.49.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campeau L, Bourassa MG, Bois MA, Saltiel J, Lesperance J, Rico O, Delcan JL, Telleria M. Clinical significance of selective coronary cinearteriography. Can Med Assoc J. 1968;99:1063–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Detry JM, Kapita BM, Cosyns J, Sottiaux B, Brasseur LA, Rousseau MF. Diagnostic value of history and maximal exercise electrocardiography in men and women suspected of coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1977;56:756–61. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.56.5.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Humphries JO, Kuller L, Ross RS, Friesinger GC, Page EE. Natural history of ischemic heart disease in relation to arteriographic findings: a twelve year study of 224 patients. Circulation. 1974;49:489–97. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.49.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelemen MH, Gillilan RE, Bouchard RJ, Heppner RL, Warbasse JR. Diagnosis of obstructive coronary disease by maximal exercise and atrial pacing. Circulation. 1973;48:1127–33. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.48.6.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Linhart JW, Turnoff HB. Maximum treadmill exercise test in patients with abnormal control electrocardiograms. Circulation. 1974;49:667–72. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.49.4.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mason RE, Likar I, Biern RO, Ross RS. Multiple-lead exercise electrocardiography. Experience in 107 normal subjects and 67 patients with angina pectoris, and comparison with coronary cinearteriography in 84 patients. Circulation. 1967;36:517–25. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.36.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Proudfit WL, Shirey EK, Sones FM., Jr Selective cine coronary arteriography. Correlation with clinical findings in 1,000 patients. Circulation. 1966;33:901–10. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.33.6.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.2008 Echocardiography and Nuclear Medicine Census Market Summary Report. IMV Online Publishing. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raff GL, Abidov A, Achenbach S, Berman DS, Boxt LM, Budoff MJ, Cheng V, DeFrance T, Hellinger JC, Karlsberg RP. SCCT guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of coronary computed tomographic angiography. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2009;3:122–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.