Abstract

Biodegradability can be incorporated into cationic polymers via use of disulfide linkages that are degraded in the reducing environment of the cell cytosol. In this work, N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide (HPMA) and methacrylamido-functionalized oligo-L-lysine peptide monomers with either a non-reducible 6-aminohexanoic acid (AHX) linker or a reducible 3-[(2-aminoethyl)dithiol]propionic acid (AEDP) linker were copolymerized via reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization. Both of the copolymers and a 1:1 (w/w) mixture of copolymers with reducible and non-reducible peptides were complexed with DNA to form polyplexes. The polyplexes were tested for salt stability, transfection efficiency, and cytotoxicity. The HPMA-oligolysine copolymer containing the reducible AEDP linkers was less efficient at transfection than the non-reducible polymer and was prone to flocculation in saline and serum-containing conditions, but was also not cytotoxic at charge ratios tested. Optimal transfection efficiency and toxicity was attained with mixed formulation of copolymers. Flow cytometry uptake studies indicated that blocking extracellular thiols did not restore transfection efficiency and that the decreased transfection of the reducible polyplex is therefore not primarily caused by extracellular polymer reduction by free thiols. The decrease in transfection efficiency of the reducible polymers could be partially mitigated by the addition of low concentrations of EDTA to prevent metal-catalyzed oxidation of reduced polymers.

Keywords: N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide, oligolysine peptide, RAFT polymerization, reducible polymer, plasmid delivery

1. Introduction

Biodegradability is an important attribute of polycations used in nucleic acid delivery formulations for in vivo applications. Polyplexes (polycation and nucleic acid complexes) formed from higher molecular weight polycations are more stable in the extracellular environment (Tang et al., 2010) while intracellular nucleic acid release typically occurs by competitive displacement and therefore occurs more readily when shorter polycations are used (Schaffer et al., 2000). In addition, polycation cytotoxicity has been shown to be reduced with decreasing polymer molecular weight (de Wolf et al., 2007; Fischer et al., 2003; Hwang and Davis, 2001). To meet these two seemingly opposing material requirements, polycations that undergo triggered intracellular degradation have been employed. The two most commonly used strategies employed in design of degradable polycations are acid-labile bonds, such as hydrazones and esters, and reducible disulfide linkages (Bauhuber et al., 2009; Ganta et al., 2008; Ouyang et al., 2009). The latter approach is particularly attractive because the disulfide bonds are stable in the oxidizing extracellular environment while the reducing environment of the cell cytoplasm triggers intracellular degradation.

Three major approaches have been used to incorporate reducible bonds in polyplex formulations: (1) crosslinking polyplexes using reactive thiols or disulfide-containing crosslinkers, (2) crosslinking low molecular weight polycations using the same approach, or (3) synthesizing cationic polymers with internal disulfide linkages. Disulfide bonds were first introduced to polyplex formulations by crosslinking preformed polyplexes to increase stability of polyplexes for in vivo applications (McKenzie et al., 2000a; McKenzie et al., 2000b; Trubetskoy et al., 1999). In these examples, crosslinked polyplexes were shown to be more resistant to DNA release and colloidal aggregation. The second approach has been primarily applied to polyethylenimine (PEI); crosslinking of PEI has been shown to increase transfection efficiency of low molecular weight PEI while providing reduced toxicity compared with high molecular weight, non-degradable PEI in several reports (Breunig et al., 2007; Choi and Lee, 2008; Deng et al., 2009; Gosselin et al., 2001; Kloeckner et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2010; Neu et al., 2006; Peng et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2006). Finally, reducible polymers, such as reducible poly(amidoamines) have been synthesized by using monomers containing an internal disulfide bond (Burke and Pun, 2010; Chen et al., 2009; Dai et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2006; Ou et al., 2008). One major advantage of this approach is better control over final polymer architecture that may improve the reproducibility of polyplex formulations.

We previously synthesized HPMA-oligolysine copolymers that contain a reducible disulfide linker, 3-[(2-aminoethyl)dithio] propionic acid (AEDP), between the HPMA backbone and the oligolysine peptide via free radical polymerization (Burke and Pun, 2010). Additionally, we recently demonstrated that the HPMA-oligolysine copolymers can be synthesized via reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization, resulting in narrowly-disperse and well-defined polymers, as well as stoichiometric incorporation of peptide monomers. The oligolysine length, oligolysine content and polymer molecular weight for this class of polymers was optimized for polymer’s ability to transfect cultured cells (Johnson et al., 2010; Johnson et al., 2011). Polymers composed of oligolysines with ten lysines (K10) incorporated at 20 mole % showed comparable transfection efficiencies to that of polyethylenimine (PEI), but with reduced toxicity.

The goal of this work is to synthesize reducible HPMA-oligolysine polymers via controlled RAFT polymerization and to evaluate transfection efficiency and toxicity of these materials in several cultured cell lines. Because HPMA-oligolysine molecular weight and peptide loading can be well controlled using this approach, the effect of a reducible versus stable architecture can be studied directly by keeping these other factors, known to affect transfection efficiency, constant. Although the backbone of these HPMA-oligolysine polymers is not readily degradable, reduction results in release of oligolysine peptides from the main chain. Since the oligolysine component of the copolymers represents a majority of the mass ratio of the copolymer, complete reduction of disulfide linkers by releasing the oligolysine component from the polymer would result in a significantly diminished polymer molecular weight. Thus, polymers were designed to have molecular weights above the renal filtration threshold to promote polyplex stability during circulation but to degrade into fragments that can be easily excreted after disulfide reduction.

In this work we report the synthesis and evaluation of HPMA-oligolysine copolymers for the delivery of plasmid DNA. Copolymers of HPMA and oligolysine with either a nonreducible or a reducible linker were synthesized via RAFT polymerization. Polyplexes with these copolymers were evaluated for salt stability, and transfection efficiency and cytotoxicity various cell lines. Finally, flow cytometry and transfection studies with 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) assess the effect of free extracellular thiols on uptake and transfection efficiency using these copolymers.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylate (HPMA) was purchased from Polysciences (Warrington, PA). The initiator VA-044 was purchased from Wako Chemicals USA (Richmond, VA). Chain transfer agent ethyl cyanovaleric trithiocarbonate (ECT) was a generous gift from Dr. Anthony Convertine (University of Washington). Rink amide resin was purchased from Merck Chemical Int. (Darmstadt, Germany). HBTU and Fmoc-protected lysine were purchased from Aapptec (Louisville, KY). N-succinimidyl methacrylate was purchased from TCI America (Portland, OR). Maleimide-functionalized Alexa Fluor 488 was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). All cell culture reagents were purchased from Cellgro/Mediatech (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). All other materials, including poly(ethylenimine) (PEI, 25,000 g/mol, branched) and poly(L-lysine) (PLL, 12,000 – 24,000 g/mol), were reagent grade or better and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated. Endotoxin-free plasmid pCMV-Luc2 was prepared by using the pGL4.10 vector (Promega, Madison, WI) and inserting the CMV promoter/intron region from the gWiz Luciferase (Aldevron, Madison, WI). The plasmid was isolated and produced with the Qiagen Plasmid Giga kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.2. Synthesis of peptide monomers

N-(9-Fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl)-protected 3-[(2-aminoethyl)dithio] propionic acid (Fmoc-Aedp) was synthesized as previously described, but with some improvements (Burke and Pun, 2010). Briefly, 616 mg (1.83 mmol, 2 eq.) of 9-fluorenylmethyl N-succinimidyl carbonate (Fmoc-OSu) was dissolved in 6 mL of dimethoxyethane (DME). An AEDP solution (2 eq. at 90 g/L in aqueous sodium bicarbonate) was then added dropwise to the Fmoc-OSu solution while stirring. The reaction mixture was allowed to proceed for 3 h at room temperature with vigorous stirring in the dark after which the solution was filtered through a 0.2 μm pore size PVDF filter and solvent removed in vacuo. The desired product was then extracted in chloroform as described previously. Crude material was then dissolved in minimum amount of dichloromethane and reprecipitated in cold hexane to give an off-white solid in quantitative yield.

Oligo-L-lysine (K10) was synthesized on a solid support containing the Rink amide linker (100–200 mesh) using standard Fmoc/tBu chemistry on an automated PS3 peptide synthesizer (Protein Technologies, Phoenix, AZ). Prior to peptide cleavage from the resin, the N-terminus of the peptide was deprotected and modified with either Fmoc-protected 6-aminohexanoic acid (AHX) or Fmoc-AEDP. The N-terminus was then subsequently deprotected and reacted with N-succinimidyl methacrylate to provide a methacrylamido functionality on the peptide. The functionalized peptide monomers are referred to as MaAhxK10 and MaAedpK10. Synthesized peptides were cleaved from the resin by treating the solid support with a solution of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)/dimethoxybenzene (DMB)/triisopropylsilane (TIS) (92.5:5:2.5 v/v/v) for 1.5 h with gentle mixing. Cleaved peptide monomers were then precipitated in cold ether, dissolved in methanol, and re-precipitated in cold ether. The peptide monomers were then frozen, lyophilized, and stored at −20 °C until polymer synthesis. If needed, peptide monomers were purified via reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) using acetonitrile as the mobile phase and dH2O (0.1 μm filtered) as the stationary phase. The peptide monomers were analyzed by RP-HPLC and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (MS) and were shown to have greater than 95% purity. The products were confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS. MALDI-TOF MS calculated for MaAhxK10 (MH+), [1479.98]; found, [1480.02]. MALDI-TOF MS calculated for MaAedpK10 (MH+), [1530.09]; found, [1530.09].

2.3. Synthesis of HPMA-co-AhxK10 via free radical polymerization

A copolymer of HPMA-co-AhxK10 was synthesized via free radical polymerization as previously described (Burke and Pun, 2010), with some modifications. Briefly, 20 mol % of MaAhxK10 (0.027 mmol, or 40 mg) and 80 mol % of HPMA (0.108 mmol, or 15.5 mg) were dissolved in reaction buffer (6 M guanidine hydrochloride, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5 M Tris-base, buffered to pH 8.3 with HCl) to give a final monomer concentration of 85 mg/mL. The weight of the initiator (I) 2,2′-azobis[2-(2-imidazolin-2-yl)propane]dihydrochloride (VA-044) used for the polymerization was calculated as 5% of the total mmole of the monomer (to give a theoretical degree of polymerization, or DP, of 190). The reaction mixture was added to an oven-dried 5 mL pear-shaped reaction vessel, purged with N2 gas for 15 min, and then sealed and heated to 44 ºC for 48 h to generate 27 mg of copolymer after dialysis.

2.4. Synthesis of HPMA-co-AhxK10 and HPMA-co-AedpK10 via RAFT polymerization

Copolymers of HPMA-co-AhxK10 and HPMA-co-AedpK10 were synthesized via reversible-addition fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization as previously described (Johnson et al., 2010), using ethyl cyanovaleric trithiocarbonate (ECT, MW 263.4 g/mol) (Convertine et al., 2009) as the chain transfer agent (CTA) and VA-044 as the initiator (I). Briefly, 20 mol % of either MaAhxK10 or MaAedpK10 (0.176 mmol, or 270.0 mg) and 80 mol % of HPMA (0.705 mmol, or 100.98 mg) were dissolved and sonicated in acetate buffer (1 M in dH2O, pH 5.1) such that the final monomer concentration was 0.7 M. The molar ratio of CTA/I was 10, and the DP used was 190. The reaction mixture was added to a 5 mL reaction vessel in the following order: ECT (100 mg/mL in ethanol), 100% ethanol (10% of the final reaction volume), peptide monomer/HPMA mixture, and VA-044 (10 mg/mL in acetate buffer). The reaction vessels were then sealed with a rubber septum and purged with N2 gas for 10 min prior to incubation in an oil bath (44 °C) for 24 h. The copolymer solution was then dissolved in water, dialyzed against dH2O to remove unreacted monomers and buffer salts, lyophilized, and stored at −20 °C. The final yield after dialysis was 58% of the theoretical yield.

2.5. Polymer characterization and degradation studies

Molecular weight analysis of the copolymers was carried out by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) as previously described, using a miniDAWN TREOS light scattering detector (Wyatt, Santa Barbara, CA) and an Optilab rEX refractive index detector (Wyatt). Absolute molecular weight averages (Mn and Mw) and dn/dc values were calculated using ASTRA software (Wyatt). The dn/dc value for each copolymer was 0.133 mL/g. The content of K10 peptide within the HPMA copolymers were determined by amino acid analysis, as previously described (Johnson et al., 2011).

Reduction of HPMA-MaAedpK10 copolymers was carried out by dissolving the copolymers at a concentration of 10 mg/mL in acetate buffer (150 mM, pH 4.4) with 1 mM EDTA. Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine) (TCEP) was added to the solution to a final concentration of 25 mM. The progress of the reaction was followed by GPC using methods described above.

2.6. Polyplex formulation and characterization

Stock solutions of polymers were prepared at 10 mg/mL in 0.1X phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and the pH was adjusted to 6.5 by adding 0.1 N HCl. Polymer solutions were used within 2 weeks of preparation. To formulate polyplexes, pCMV-Luc2 plasmid DNA was diluted to 0.1 mg/mL in DNase/RNase-free H2O and mixed with an equal volume of polymer at desired lysine to DNA phosphate (N/P) ratios. Polyplexes were then allowed to incubate for 10 min at room temperature. For in vitro transfections, 20 μL of the polyplex solution (containing 1 μg DNA) was mixed with 180 μL of Opti-MEM medium (Invitrogen). The particle size of the polyplexes was determined by mixing 20 μL of the polyplex solution with either 20 μL of 0.2 μm-filtered dH2O or 20 μL of 2X PBS. The polyplex solutions were incubated for 15 min at room temperature prior to particle sizing by dynamic light scattering (DLS) (ZetaPALS, Brookhaven Instruments Corp.).

For serum degradation studies, pCMV-Luc2 plasmid DNA was pre-stained with YOYO-1 iodide (Invitrogen), a known bis-intercalating dye, to yield a DNA concentration of 0.1 mg/mL at a ratio of 5:1, DNA base pairs to dye molecules. The DNA-dye solution was allowed to incubate for 1 h at room temperature. Polyplexes were prepared by adding 10 μL of polymer solution to 10 μL of pDNA-dye solution (containing 1 μg DNA) at N/P of 5. Equal volumes (20 μL) of various fetal bovine serum (FBS) concentrations were added to the polyplex solution to give serum final concentrations of 50%, 25%, and 10%, and the polyplexes were allowed to incubate for 30 min. 20 μL aliquot samples, mixed with 1 μL of loading buffer, were then loaded onto a 0.8% agarose gel containing TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-acetate, 1 mM EDTA) and electrophoresed in the dark at 100 V. pDNA was then visualized using an UV transilluminator (laser-excited fluorescence gel scanner, Kodak, Rochester, NY).

2.7. Cell culture

HeLa (human cervical carcinoma), NIH/3T3 (mouse embryonic fibroblast), and CHO-K1 (Chinese hamster ovary) cells were grown in minimum essential medium (MEM), Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM), and F-12K medium, respectively, supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 IU penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin B. Cells were passaged when they reached ~80% confluency.

2.8. In vitro transfection

HeLa, NIH/3T3, and CHO-K1 cells were seeded overnight in 24-well plates at a density of 3 × 104 cells per well (1 mL/well) at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Polyplexes were formed as described above. After the polyplexes were formed, 20 μL (containing 1 μg DNA) was mixed with 180 μL of Opti-MEM medium (Invitrogen) or complete cell medium (containing 10% FBS) for serum transfections. Seeded cells were washed once with PBS and then treated with 200 μL of polyplexes in Opti-MEM or complete medium, which was added dropwise on top of the cells. After a 4 h incubation at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in a humidified environment, the cells were washed once again with PBS and incubated in 1 mL of fresh complete medium for an additional 44 h. For studies with DTNB, the cells were pre-incubated with 500 μL DTNB (5 mM in Opti-MEM) for 1 h, washed with PBS, and then incubated with polyplexes in Opti-MEM containing 5 mM DTNB for 4 h. For studies with EDTA, cells were treated with polyplexes in Opti-MEM containing 1 mM EDTA for 4 h; cells were collected, washed with PBS, pelleted, resuspended in complete media, and added back into the well for an additional 44 h. In all experiments cells were harvested and assayed for luciferase expression at 48 h. This was done by washing cells once with PBS, adding of 200 μL reporter lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI), and then performing one freeze-thaw cycle to complete the lysis of cells. Lysates were collected and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min. Luminescence was carried out following the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). Luciferase activity is reported in relative light units (RLU) normalized by mg protein (RLU/mg), as measured by a microBCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce).

2.9. Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity of the polymers was evaluated in vitro using the MTS assay. HeLa, NIH/3T3, and CHO-K1 cells were plated overnight in 96-well plates at a density of 3 × 103 cells per well per 0.1 mL. Polymers were prepared in serial dilutions in dH2O and then diluted 10-fold in Opti-MEM medium (Invitrogen). The cells were rinsed once with PBS and incubated with 40 μL of the polymer solution for 4 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Cells were rinsed once with PBS and the medium was replaced with 100 μL complete growth medium. At 48 h, 20 μL of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) (Promega) were added to each well. Cells were then incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 4 h. The absorbance of each well was measured at 490 nm using a microplate reader (TECAN Safire2). IC50 values were computed using a nonlinear fit (four-parameter variable slope) in GraphPad Prism v.5 (San Diego, CA).

2.10. Flow cytometry and microscopy

HeLa and NIH/3T3 cells were seeded overnight in 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well (2 mL/well) at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Polyplexes were formulated with polymer and plasmid DNA labeled with TOTO-3 (1 dye per 25 base pairs). The polyplexes were then diluted 10-fold in Opti-MEM and the fluorescence of TOTO-3 were measured on a microplate reader (Tecan Safire2). Seeded cells were washed once with PBS and treated with 1 mL of DTNB (5 mM in Opti-MEM) or Opti-MEM (for non-treated samples) for 1 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Polyplexes were formulated with polymer and plasmid DNA labeled with TOTO-3 (1 dye per 25 base pairs). The cells were then incubated with 800 μL of Opti-MEM containing polyplexes (with 5 mM DTNB for treated samples) for 30 min at 37 °C, 5% CO2. The cells were washed once again with PBS and treated with CellScrub (Genlantis) for 15 min at room temperature to remove extracellularly-bound polyplexes. Cells were then trypsinized, pelleted at 1000 × g for 5 min. Cell were pelleted again, washed with complete medium, and resuspended in 0.3 mL complete medium for flow cytometry. Flow cytometry analysis was completed at the Cell Analysis Facility (BD FACS Canto, University of Washington). TOTO-3 was excited at 633 nm and the emission was detected using a 660/20-nm band-pass filter. A total of 10,000 events were collected per sample.

2.11. Statistical analysis

The data are represented as the mean and standard deviations. Differences were analyzed using the two-tailed Student’s t-test and a p-value of less than or equal to 0.05 was taken as significant.

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis of HPMA-co-AhxK10 and HPMA-co-AedpK10

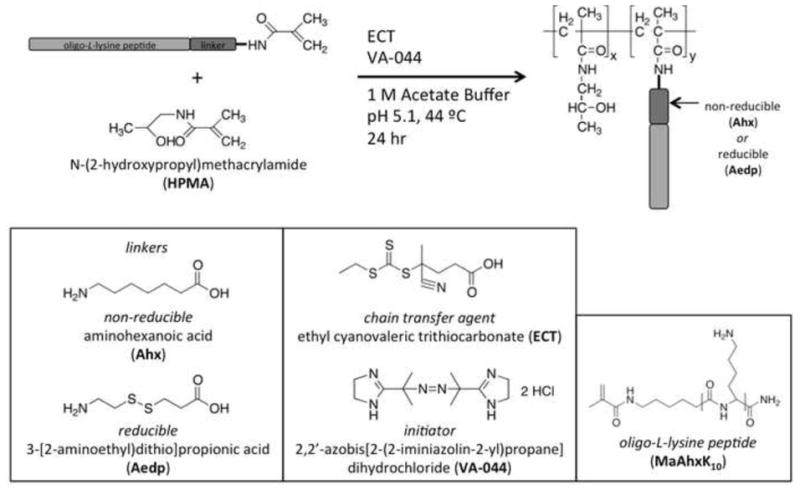

Synthesis of HPMA-co-MaAhxK10 and HPMA-co-MaAedpK10 copolymers was carried out by RAFT copolymerization of HPMA with oligolysine comonomers that contained either an AEDP or AHX linker. The principle difference between the two linkers is that AEDP contained an internal disulfide bond that can be degraded in reducing environments such as the cell cytosol. Copolymerization was carried out as illustrated in (Scheme 1). The resulting polymers displayed properties that were close to targeted values (Table 1). The number molecular weight average, Mn, of HPMA-co-MaAedpK10 was 80.2 kDa, which corresponded well to the targeted molecular weight of 79.5 kDa. Polydispersity of the copolymer was 1.11. Amino acid analysis of the HPMA-oligolysine copolymers demonstrated a near quantitative yield of the oligo-L-lysine peptide monomer in resulting copolymers (final mole %: 18.4). As a result, the concentration of lysine in each of the final copolymers In both copolymers the targeted degree of polymerization (DP) was 190; as a consequence, the number of monomers per copolymer chain was similar and the lysine weight ratio was identical despite some difference in the final Mn of the two copolymers.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of reducible HPMA-co-oligolysine copolymers via reversible-addition fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization. Statistical polymers of HPMA and oligolysine were synthesized via RAFT polymerization using ECT as the chain transfer agent and VA-044 as the initiator. A CTA to I ratio of 10 and a degree of polymerization (DP) of 190 was used in all polymerizations. A non-reducible (Ahx) or a reducible (Aedp) linker was used in the synthesis of the oligolysine (K10) peptide in order to introduce biodegradability into the polymer. Peptide monomers were functionalized with a methacrylamido group (Ma) for polymerization.

Table 1.

Properties of HPMA-oligolysine copolymers.

| Polymer | Targeted Mn (kD) | Determined Mn (kD)a | Mn/Mna | mol % K10 monomerb | mmol amine/g polymerb | IC50(μg lys/mL)c | IC50 (μg lys/mL)d | Ic50 (μg lys/mL)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer synthesized by free radical polymerization | ||||||||

| HPMA-AhxK10 | 78.0 | 168.4 | 2.24 | 12.0 | 0.00713 | 0.114* | 0.128* | 0.0901** |

|

| ||||||||

| Polymers synthesized by RAFT polymerization | ||||||||

| HPMA-AhxK10 | 78.0 | 77.6 | 1.18 | 19.6 | 4.83 | 9.67* | 8.23* | 12.16* |

| HPMA-AedpK10 | 79.5 | 80.2 | 1.11 | 19.4 | 4.79 | 13.03* | 14.10* | 20.18* |

| 1:1 (w/w) mixture | - | - | - | - | - | 12.24* | 10.54* | 12.25* |

|

| ||||||||

| bPEI (25 kD) | - | - | - | - | 23.22 | 1.85** | 1.57* | 1.45** |

| PLL (12–24 kD) | - | - | - | - | 4.51 | 0.70** | 0.72* | 0.75** |

Values determined by GPC coupled with laser light scattering, and dRI detection.

Mole % of oligo-L-lysine and mmol amine/g polymer determined by amino acid analysis.

IC50 values determined using NIH/3T3 cells.

IC50 values determined using CHO-K1 cells.

IC50 values determined using HeLa cells.

Values were adjusted to lysine equivalent.

Values were adjusted to amine equivalent and IC50 values are in μg amine/mL

To compare polymers synthesized via RAFT and free radical polymerization, a copolymer of HPMA-co-MaAhxK10 was also synthesized via free radical polymerization (Table 1). The parameters used in the synthesis were kept as similarly as possible to the synthesis of the RAFT polymers to generate a comparable material. However, despite a targeted DP of 190, the polymer synthesized via free radical polymerization had a very large Mn and also resulted in lower than expected incorporation of oligo-L-lysine peptide.

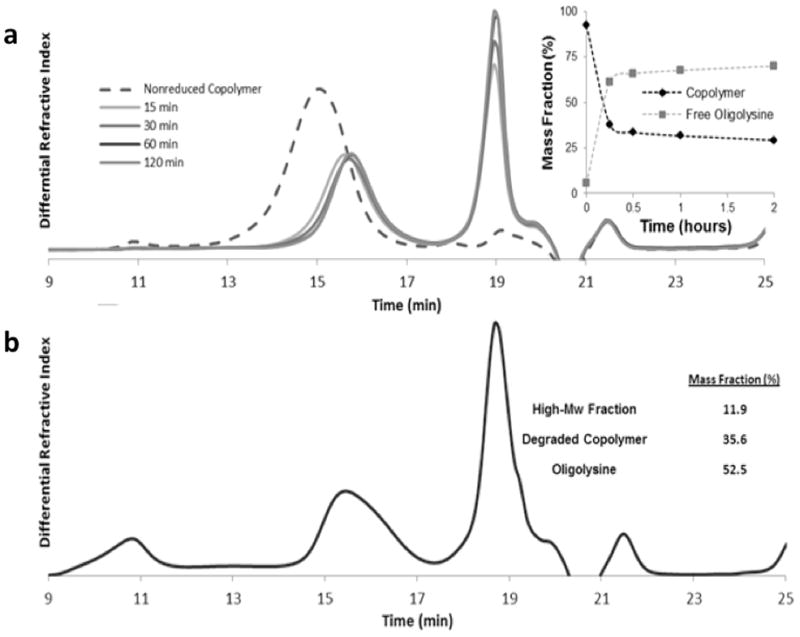

3.2. Polymer degradation with TCEP

The HPMA-co-MaAedpK10 copolymer was treated with tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) to reduce the disulfide bond contained in the MaAedpK10 component of the copolymers. Reduction was assessed by size exclusion chromatography. Degradation was done in the presence of EDTA (Fig. 1a) or without EDTA (Fig. 1b), a chelator that sequesters trace metals capable of oxidizing free sulfhydryls to disulfide bonds. The mass fraction of the degraded products was calculated by determining the area under the corresponding peaks. Figure 1a indicated that reduction of the disulfide bonds proceeded quickly. At 15 min, the copolymer was 80.2% degraded and by 2 h, the polymer was 99.3% degraded. When EDTA was present, treatment with TCEP resulted in the generation of degraded copolymer and free oligolysine. However, when EDTA was not present, a high molecular weight fraction was also generated, the degraded copolymer appeared less uniform, and at least a portion of oligolysine appeared to dimerize.

Fig. 1.

Degradation of HPMA-AedpK10 with TCEP. HPMA-AedpK10 was degraded over time in the presence of 25 mM TCEP. Reduced copolymers were applied to a GPC column to track changes in molecular weight at degradation of the copolymer occurred. (a) Reduction was done in the presence of EDTA. The insert indicates the mass fraction of degraded copolymer and free oligolysine. Degraded copolymer eluted between 14 to 17 min, while free oligolysine eluted from 18 to 20 min. The insert shows the mass fraction of peptide and copolymer. Reduction done without EDTA (b) produced three eluted peaks in SEC. The first is a high molecular weight fraction (9 to 12 min), the second peak is degraded copolymer (14 to 17 min), and the third is oligolysine (18 to 20 min).

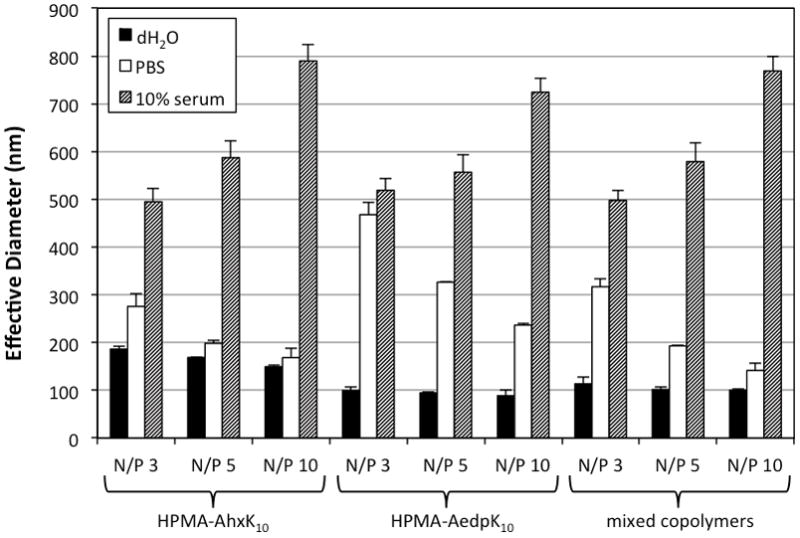

3.3. Polyplex stability

Dynamic light scattering was used to measure the effective hydrodynamic diameter of HPMA-AhxK10 and HPMA-AedpK10 polyplexes at N/P ratios of 3, 5, and 10 in water, 150 mM PBS, and complete cell medium (DMEM + 10% FBS). Polyplexes of HPMA-AhxK10 formed small particles in water (150–186 nm), and particle size at N/P of 5 and 10 remained stable against salt-induced aggregation in 150 mM PBS (Fig. 2). Polyplexes of HPMA-AedpK10 formed smaller particles in water (90–100 nm) compared to HPMA-AhxK10, but were not salt stable even in the presence of 1 mM EDTA (data not shown). Polyplexes of a 1:1 (w/w) mixture of the non-reducible and reducible polymer formed small particles in water, similar to that of HPMA-AedpK10, and were relatively salt stable like HPMA-AhxK10. All polyplex formulations increased in size to an average hydrodynamic diameter > 500 nm in 10% serum. These data suggest that although the reducible polymer does not form salt stable polyplexes, a mixture with non-reducible polymer increases polyplex salt stability. However, in the presence of 10% serum particles do not maintain their small size regardless of polymer composition.

Fig. 2.

Particle sizing of polyplexes by dynamic light scattering (DLS). The effective diameter of polyplexes formulated with HPMA-AhxK10, HPMA-AedpK10, or a 1:1 (w/w) mixture was determined by DLS in water, PBS with an ionic strength of 150 mM, and DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Data are presented as mean ± S.D., n = 3.

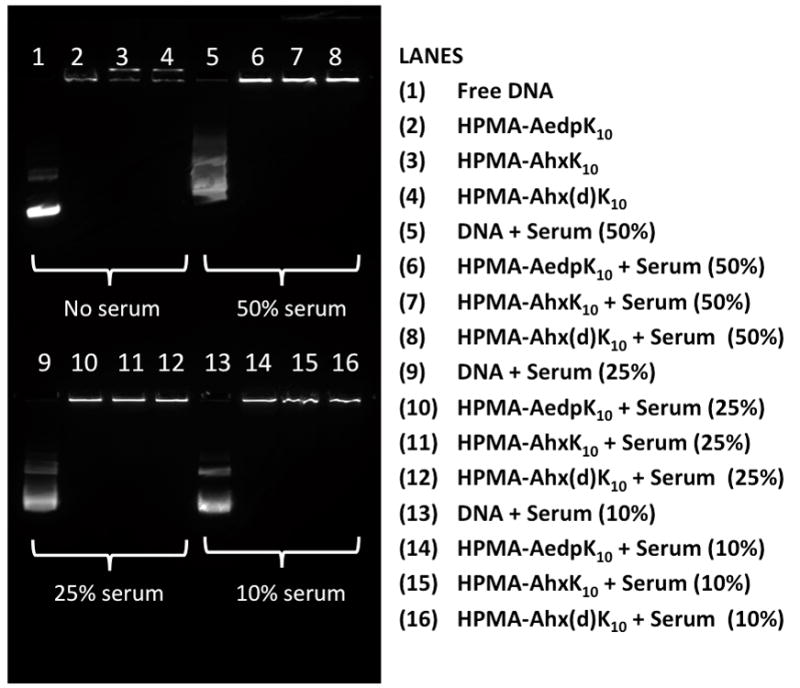

The stability of HPMA-AhxK10 and HPMA-AedpK10 polyplexes in the presence of serum was also assessed by an agarose gel retardation assay. Because serum shows an intrinsic band similar to free DNA in an agarose gel containing ethidium bromide (data not shown), a YOYO-1 pre-labeled DNA was used instead. Free DNA incubated with various concentrations of serum (lanes 1, 5, 9 and 13) show streaking as a result of DNA degradation (Figure 3). HPMA-AedpK10, HPMA-AhxK10 and a known protease-resistant copolymer, HPMA-Ahx(d)K10, in which all lysines are D-lysines, were able to fully complex plasmid DNA in the presence of various serum concentrations as shown by the absence of bands corresponding to free DNA.

Fig. 3.

Polyplex stability in serum via gel retardation assay. Polyplexes complexed with YOYO-1-labeled plasmid DNA and either HPMA-AedpK10, HPMA-AhxK10, or HPMA-Ahx(d)K10 were incubated with various concentrations of serum (50%, 25%, 10%). Free DNA (plasmid DNA not complexed with polymer) was used as a control.

3.4. Delivery of plasmid DNA to cultured cells

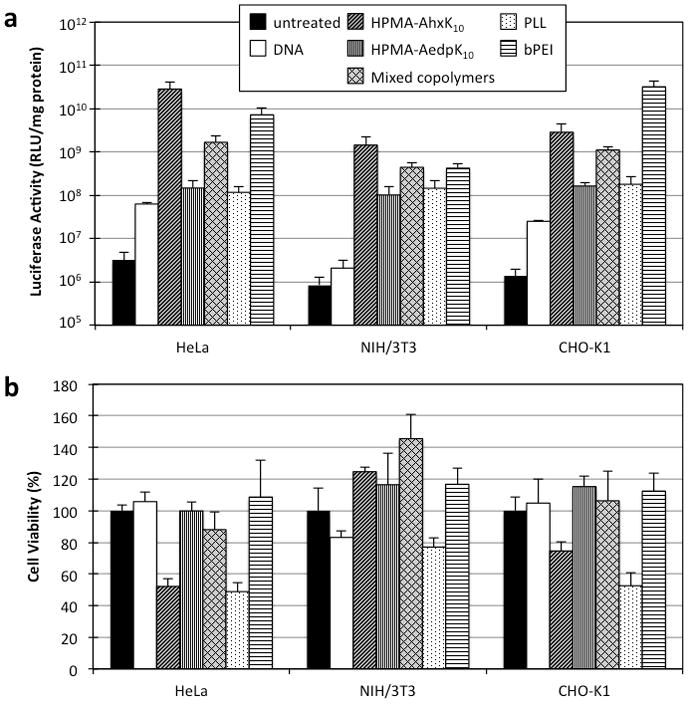

Polyplex transfection efficiency was determined by delivery of a luciferase plasmid, pCMV-Luc2, to cells in serum-free and serum-containing (10% FBS) conditions. For comparison against commonly used polymeric reagents, branched PEI (bPEI, 25 kD) and poly-L-lysine (PLL, 12–24 kD) polyplexes were also evaluated. Transfection was also conducted with HPMA-AhxK10 synthesized by free radical polymerization (Supplemental Fig. 1). Polyplexes were formed at N/P (nitrogen to phosphate) ratios of 3, 5, and 10, and evaluated for transfection efficiency under serum-free conditions in NIH/3T3, CHO-K1, and HeLa cells (Supplemental Fig. 2). N/P 5 was determined to be optimal for high transfection efficiency and low cytotoxicity; therefore, the rest of the studies were completed with polyplexes formulated at N/P 5. HPMA-AhxK10 transfected more efficiently than poly-L-lysine (PLL, 12–24 kD) in all cell lines (Fig. 4a). The luciferase activity of cells transfected with HPMA-AedpK10 was decreased by at least one order of magnitude compared to its non-reducible analog in all cell types and showed very similar activity to PLL. When the two polymers were mixed prior to polyplex formation and applied to cells, the resulting transfection efficiencies were intermediate between those of the individual polymers in all tested cell types. These results suggest that while HPMA-AedpK10 is poor at transfection, a 1:1 (w/w) mixture of HPMA-AhxK10 and HPMA-AedpK10 can improve transfection efficiency. The HPMA copolymers were also evaluated for transfection efficiency in the presence of 10% serum (Supplemental Fig. 3). Transfection efficiency of all polymer formulations was decreased under serum conditions. In addition, transfection of HPMA-AhxK10 synthesized via RAFT had very similar transfection efficiency to HPMA-AhxK10 synthesized by free radical polymerization.

Fig. 4.

(a) Transfection efficiency of HPMA copolymers in HeLa, NIH/3T3, and CHO-K1. Polyplexes (N/P 5) of copolymer and luciferase-encoding plasmid DNA were incubated with cells for 4 h in serum-free conditions. Luciferase activity was measured 48 h after transfection and normalized to total protein content in each sample. Cells: untreated controls; bPEI: branched polyethylenimine (25 kD); PLL: poly-L-lysine (12–24 kD); Mixed copolymers: 1:1 (v/v) mixture of HPMA-AhxK10 and HPMA-AedpK10. (b) Polyplex cytotoxicity in HeLa, NIH/3T3, and CHO-K1. Toxicity of the polyplexes was determined by measuring total protein content and designating untreated cells as 100% viable. Data are presented as mean ± S.D., n = 4, (*) p < 0.05, as determined by two-tailed Student’s t-test.

3.5. Polymer toxicity

Cytotoxicity of polyplexes and polymers was determined by the BCA and MTS assay, respectively. The BCA assay was conducted 48 h after transfection to determine the amount of total cellular protein in lysates of transfected cells. Untreated cells were used to determine 100% cell viability. Again, cytotoxicity of HPMA-AhxK10 synthesized by free radical polymerization was also determined as a comparison. Polyplexes of HPMA-AhxK10 and HPMA-AedpK10, formulated at N/P 5, were nontoxic to NIH/3T3 cells. HPMA-AhxK10 decreased cell viability to 74.6% in CHO-K1 cells and 52.1% in HeLa cells (Fig. 4b). A mixture of HPMA-AhxK10 and HPMA-AedpK10 reduced the toxicity of HPMA-AhxK10 alone. In comparison, PLL was very toxic to all cell types, decreasing cell viability to 43.8% in NIH/3T3 cells, 29.6% in CHO-K1 cells, and 48.8% in HeLa cells. PEI was relatively non-toxic for all cell types.

To determine the IC50 values of the polymers (concentration of polymers for 50% cell survival), cells were treated with a range of polymer concentrations in serum-free conditions to simulate transfection conditions. The MTS assay was used to assess the mitochondrial activity, an indicator of cell viability. Untreated cells were used to determine 100% cell viability. The IC50 values of both HPMA-AhxK10 and HPMA-AedpK10 copolymers were higher than both bPEI (IC50 = 1.45–1.85 μg amine/mL) and PLL (~0.7 μg amine/mL) for all cell types tested (NIH/3T3, CHO-K1, HeLa) (Table 1). HPMA-AedpK10 (13.0–20.2 μg lysine/mL) was slightly less toxic than HPMA-AhxK10 (8.2–12.2 μg lysine/mL) for all cell types, and a mixture of the two copolymers in a 1:1 (w/w) ratio resulted in decreased toxicity in NIH/3T3 (12.2 μg lysine/mL) and CHO-K1 (10.5 μg lysine/mL) cells, but not in HeLa cells (12.3 μg lysine/mL). HPMA-AhxK10 synthesized by free radical polymerization was more toxic than HPMA-AhxK10 synthesized by RAFT polymerization in all cell types.

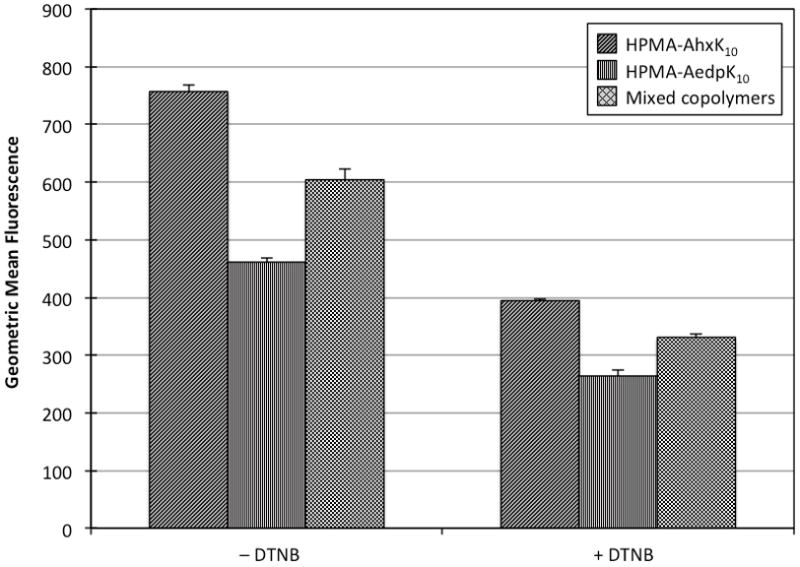

3.6. Cellular uptake and transfection of polyplexes incubated with DTNB

Redox proteins such as thioredoxin reductase and protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) can reduce thiols at the cell surface (Mandel et al., 1993; Rubartelli et al., 1992); additionally, some cell types such as HeLa cells have been found to secrete thiols into the extracellular space (Sun and Davis, 2010). To determine if the decrease in transfection efficiency in HeLa cells was due to the presence of extracellular thiols that may prematurely destabilize polyplexes, cells were pretreated with 5 mM 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), a cell-impermeable chemical that reacts with free thiols. Polyplexes of plasmid DNA labeled with TOTO-3 were then incubated with HeLa cells for 30 min with or without DTNB and cellular uptake was assessed by flow cytometry. Because the quantum yield of TOTO-3 in polyplexes is sensitive to the packaging state of the plasmid, the fluorescence of TOTO-3-labeled plasmid complexed with HPMA-AhxK10 and HPMA-AedpK10 was measured and confirmed to be similar in both formulations (Supplemental Fig. 4). Plasmid uptake was significantly lower from transfection with HPMA-AedpK10 polyplexes and mixed polyplexes compared to HPMA-AhxK10 polyplexes (Fig. 5) although nearly all cells (97–99%) were positive for fluorescence (data not shown). When cells were treated with polyplexes in the presence of 5 mM DTNB, uptake of HPMA-AedpK10 polyplexes was still significantly less than uptake of its non-reducible analog; however, the decreased uptake was less drastic. Polyplexes of a 1:1 (w/w) mixture of the two polymers were taken up by cells more efficiently than reducible polymer alone. To confirm these results, transfection efficiency PLL, PEI, HPMA-AhxK10 and HPMA-AedpK10 to NIH/3T3, CHO-K1 and HeLa cells was also evaluated in the presence of DTNB. With DTNB treatment, transfection with the reducible material remained less efficient than with the non-reducible material in all cell types tested (Supplemental Fig. 5), demonstrating that blocking extracellular thiols does not restore transfection efficiency of the reducible material.

Fig. 5.

Uptake of polyplexes in HeLa cells. Luciferase plasmid DNA was labeled with TOTO-3 prior to complexation with HPMA copolymers (HPMA-AhxK10, HPMA-AedpK10, or a 1:1 (w/w) mixture). HeLa cells pretreated with or without 5 mM DTNB in serum-free media for 1 h prior to transfection and then incubated with polyplexes for 30 min in serum-free media with or without 5 mM DTNB. Polyplex uptake was assessed by flow cytometry. DTNB stands for 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid). Data are presented as mean ± S.D., n = 3.

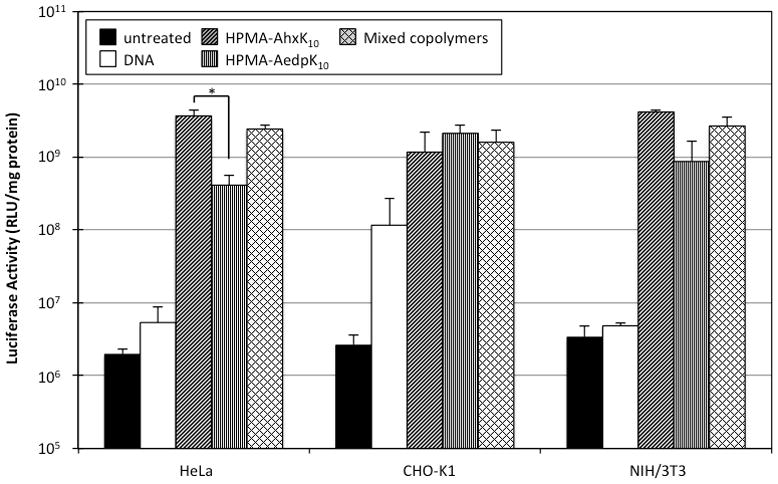

3.7. Delivery of plasmid DNA to cultured cells with EDTA treatment

Since reduced HPMA-AedpK10 was shown to crosslink in the absence of EDTA (Fig. 1b), we investigated the possibility that polymer oxidation by trace metals adversely affected transfection efficiency of these materials. To minimize metal-catalyzed redox/oxidation processes, cells were transfected with polyplexes in the presence of 1 mM EDTA. Again, HPMA-AedpK10 showed diminished ability to transfect NIH/3T3 and HeLa cells (Fig. 6). However, the difference in transfection efficiency between HPMA-AhxK10 and HPMA-AedpK10 was much less when transfections were conducted with 1 mM EDTA. In the absence of EDTA, luciferase expression in HPMA-AedpK10-transfected cells was 193-fold, 14-fold, and 17-fold lower than HPMA-AhxK10-transfected cells in HeLa, NIH/3T3, and CHO-K1 cells, respectively. However, with only 1 mM EDTA, luciferase expression in HPMA-AedpK10-transfected cells was 9-fold, 4.8-fold, and 0.6-fold lower than HPMA-AhxK10-transfected cells in HeLa, NIH/3T3, and CHO-K1 cells, respectively. In addition, the mixed copolymer formulation restored transfection efficiency to the efficiency levels of HPMA-AhxK10.

Fig. 6.

Transfection efficiency of HPMA copolymers in HeLa, CHO-K1, and NIH/3T3 in the presence of 1 mM EDTA. Polyplexes (N/P 5) of copolymer and luciferase-encoding plasmid DNA were incubated with cells for 4 h with 1 mM EDTA in serum-free conditions. Luciferase activity was measured 48 h after transfection and normalized to total protein content in each sample. Untreated: untreated controls; Mixed copolymers: 1:1 (w/w) mixture of HPMA-AhxK10 and HPMA-AedpK10. Data are presented as mean ± S.D., n = 3, (*) p < 0.05, as determined by two-tailed Student’s t-test.

4. Discussion

The incorporation of reducible moieties into cationic polymers for nucleic acid delivery has been shown as a viable method for introducing environmentally-responsive degradability. In particular, use of disulfide bonds is attractive because of their relative stability in the extracellular environment; however, disulfide bonds can be destabilized in the presence of high concentrations of reductive intracellular agents, e.g. glutathione, which is 50–1000 times (in human liver, up to 10 mM) more concentrated in the cytosol than in the extracellular space (Meister and Anderson, 1983). We hypothesized that incorporating a disulfide linkage between the pendant oligolysine peptides and the HPMA backbone would facilitate the release of DNA from polyplexes while also limiting toxicity of the cationic polymer. We have previously demonstrated that monomers of HPMA and oligolysine bearing an AEDP linker can be copolymerized via free radical polymerization, and that these copolymers were less toxic than their non-reducible counterpart (Burke and Pun, 2010). Here, reducible and non-reducible analogues of HPMA-oligolysine copolymers were synthesized by RAFT polymerization. The resulting two polymers had similar molecular weights and peptide compositions. Surprisingly, aside from reduced cytotoxicity, the reducible HPMA-AedpK10 polymer showed less attractive plasmid delivery properties compared to the non-reducible HPMA-AhxK10 polymer. Specifically, polyplexes formed from HPMA-AedpK10 were less salt stable, facilitated less plasmid uptake, and provided lower transfection efficiencies to three cultured cell lines.

First, HPMA-AhxK10 polymers synthesized by both free radical and RAFT polymerization were directly compared. RAFT polymerized polymers had controlled composition and molecular weight (19.6% K10 monomer incorporation, 77.6 kD) and were more homogenous, with polydispersities of 1.1–1.2 (Table 1). In contrast, HPMA-AhxK10 synthesized via free radical polymerization had low incorporation of K10 monomer (12%), high molecular weight (168.4 kD), and high polydispersity (2.2). Previous reports of polymers synthesized by free radical polymerization show similarly polydisperse materials (Burke and Pun, 2010; Layman, et al., 2009). The transfection efficiency of these polymers were evaluated at N/P 3, 5, and 10 in HeLa cells using the target mass to charge ratios to calculate N/P ratios (Supplemental Fig. 1). Both polymers had similar transfection efficiencies; however, the IC50 values for the free radical polymer were much lower than those for the RAFT polymer. We have previously shown that cytotoxicity of HPMA-co-oligolysine polymers increases with increasing molecular weight (Johnson et al., 2011). The high molecular weight fraction of the polydisperse HPMA-AhxK10 synthesized via free radical polymerization is likely responsible for the observed toxicity. Therefore, HPMA-AhxK10 synthesized by RAFT polymerization results in more controlled and well-defined polymers with reduced cytotoxicity.

The ability for polyplexes to remain stable in physiological salt conditions is an important attribute for systemic delivery. We showed both previously and in this manuscript that polyplexes formulated with HPMA-AhxK10 are salt stable (Fig. 2). Salt-induced increases in the particle size of polyplexes results from a disruption of the electrical double layer caused by the addition of counter ions. Several studies have demonstrated that incorporation of a hydrophilic but uncharged polymer, such as PEG, prevents flocculation through steric repulsion even after the electrical double layer has been disrupted by salts (Oupicky et al., 2002). In this context, HPMA monomers were included as the backbone of both HPMA-AedpK10 and HPMA-AhxK10 copolymers to stabilize polyplexes in physiological conditions. However, polyplexes formed in the presence of 10% serum increased in size to >500 nm regardless of polymer type and composition. Despite this increase in size, polyplexes in the presence of serum remain intact. Gel electrophoresis of polyplexes confirm that polyplexes were retained in the well, unlike free DNA that migrated and was degraded in the presence of serum (Fig 3). However, the fluorescence intensity of polplexes in the well increased with increasing serum content. Since the YOYO-1 intercalating dye is quenched by inter-molecular electronic interactions when plasmid DNA is condensed, this indicates that the polyplexes are loosened in the presence of serum. Interestingly, increasing N/P ratios resulted in the largest effective diameters, possibly due to interaction between excess polymer and serum proteins (Fig 2). Reduced transfection efficiency of these polymers in serum (Supplemental Fig. 3a–c) may be due to the inability of the excess polymer to mediate transfection, which has been shown to be important for efficient transfection (Thibault et al., 2011; Boeckle et al., 2004). Polyplex toxicity was also reduced under serum conditions (Supplemental Fig. 3d–f), which further suggests that free polymer may be neutralized by serum proteins.

Multiple groups have reported that the incorporation of disulfide linkages does not affect polyplex stability in salt (Ouyang et al., 2009). However, unlike HPMA-AhxK10 polyplexes, polyplexes formed with HPMA-AedpK10 were not salt stable. Particle size of the polyplexes increased from relatively small particles that were below 100 nm in water to particles with much larger effective diameters (Fig. 2). Differences in stability between HPMA-AedpK10 and HPMA-AhxK10 polyplexes may be attributed to the increased concentration of disulfide bonds (Miyata et al., 2004). The more hydrophobic HPMA-AedpK10 polymers may render the resulting polyplex more prone to flocculation from van der Waals attraction forces. Salt-induced flocculation of polyplexes formulated with HPMA-AedpK10 copolymers may also indicate premature degradation of disulfide bonds in the AEDP linkers leading to intermolecular crosslinking or even loss of HPMA from the polyplex surface. Degradation of disulfide bonds can spontaneously occur through direct attack of the disulfide bond by hydroxyl anions or by α- and β-elimination reactions at neutral and basic conditions (Trivedi et al., 2009). Also, it has been shown that spontaneous reduction of a single disulfide bond in proteins with several disulfide bonds can trigger other intermolecular reducing reactions, disrupting protein stability (Kelly and Zydney, 1994; Tous et al., 2005). In a similar manner, degradation of a disulfide bond in a polyplex formulated with HPMA-AedpK10 copolymers could potentially lead to a chain-reduction of proximal disulfide bonds, which would have high local concentrations within a polyplex. Pichon and coworkers showed by TEM using their disulfide bond-containing poly[Lys-AEDTP] materials that particle fusion, hypothesized to result from intermolecular crosslinking, occurs quickly after polymer reduction followed by polyplex decomplexation. However, it should be noted that with our materials, particle flocculation in salt was not mitigated by addition of EDTA to prevent metal-catalyzed oxidation.

Polyplexes of the reducible polymer HPMA-AedpK10 did not transfect cells as well as its non-reducible analog, HPMA-AhxK10, but transfected similarly to PLL (Fig. 4a). However, the reducible polymer was relatively non-toxic compared to the non-reducible polymer in HeLa and CHO-K1 cells, and PLL in all cell types tested (Fig. 4b). These results show that the toxicity profile of the HPMA-oligolysine is improved by incorporating a disulfide linkage. At higher N/P ratios transfection efficiency with HPMA-AedpK10 materials can approach that of HPMA-AhxK10 (Supplemental Fig. 2). Increases of transfection at elevated charge ratios have been attributed to increased concentrations of free cationic polymer by promoting release of polyplexes from the endosomes and lysosomes (Thibault et al., 2011).

Previous reports have identified that extracellular reduction can affect the uptake of disulfide-containing cationic peptides (Aubry et al., 2009) or polymers (Sun and Davis, 2010). To investigate if decreased transfection efficiency of HPMA-AedpK10 was due to premature extracellular reduction, cellular uptake of HPMA-AhxK10 and HPMA-AedpK10 polyplexes in HeLa cells in the presence of the cell-impermeable reagent DTNB was assessed by flow cytometry. DTNB has been used previously to block reductive effects of free extracellular thiols (Bauhuber et al., 2009). Cellular uptake of polyplexes formulated with HPMA-AhxK10, HPMA-AedpK10, or a 1:1 (w/w) mixture of both copolymers reflected similar trends to those observed in transfection studies (Fig. 5). DTNB treatment reduced uptake of all polyplexes, but showed similar trends as the uptake study completed without DTNB. Similarly, transfection with HPMA-AedpK10 polyplexes did not improve with DTNB (Supplemental Fig. 5). These results suggest that extracellular reduction of HPMA-AedpK10 by free thiols is not the major cause of decreased cellular uptake of the reducible polyplexes, and decreased cellular uptake may be caused by an alternative mechanism.

In instances where HPMA-AedpK10 was dissolved as a stock solution and then stored at 4 °C for longer than 2 weeks, a higher molecular weight fraction was observed by GPC analysis (data not shown). A similar observation was also made when degradation studies using 25 mM TCEP to reduce HPMA-AedpK10 copolymer was done without EDTA. These observations indicate that metal-catalyzed oxidation of free sulfhydryls influences the material properties through nonspecific crosslinking of HPMA-AedpK10 copolymers. To control the effects of metal-catalyzed oxidation of free sulhydryl groups, transfections were done with fresh stock solutions of HMPA-AedpK10 and transfections were also done in the presence of EDTA. Treatment of cells with EDTA increased transfections in some instances (Fig. 6). One possible explanation is that oxidation of degraded HPMA-AedpK10 copolymers could effectively cage proximal DNA, preventing its release from the polyplex and thereby limit the transfection efficiency of the materials. A study by Christensen and coworkers also demonstrated that diminished transfection efficiency of poly(amido ethyleneamine) that correlated with increased branching and disulfide content (Christensen et al., 2006). Furthermore, Miyata and coworkers also demonstrated that diminished transfection efficiency was observed at elevated disulfide crosslinkers in reducible PLL-PEI materials (Miyata et al., 2004). It may also be possible to achieve higher transfection efficiencies at higher N/P ratios. Wang and coworkers show that reducible linear cationic polymers prepared by click chemistry transfected better than their non-reducible counterparts, but at N/P ratios of 15 and higher (Wang, et al. 2011). Similar trends were observed for other polymer systems (Ou, et al., 2008; Son, et al., 2010). For most practical applications in nucleic acid delivery, use of reducible materials requires greater stability that that presented by HPMA-AedpK10. Improvements in polyplex stability were observed when mixtures of reducing and non-reducing HPMA-oligolysine copolymers were used. The polyplexes demonstrated improved salt stability, increased transfection efficiency, and were non-toxic at charge ratios tested. This formulation may prevent premature reduction of disulfide bonds and limit unwanted oxidation from occurring by spatial separation and/or steric hindrance. Alternatively, disulfide linkages have been stabilized by adding methyl groups (Kellogg et al., 2011) and/or benzene rings (Sun et al., 2009) around the disulfide bond in order to sterically hinder premature reduction before reaching the cytosol.

In summary, we describe the controlled synthesis of a reducible HPMA-oligolysine copolymer and evaluate the transfection efficiency of this polymer and its non-reducible counterpart in multiple cell lines. The reducible polymer was tolerated better than the non-reducible polymer but also showed lower transfection efficiency in cultured cells. Elimination of extracellular thiols did not restore transfection efficiency, indicating that premature extracellular reduction is not the primary cause of decreased transfection. However, stability of the reducible polymer was improved with the addition of EDTA. In addition, a mixed formulation of reducible and non-reducible copolymers was able to partially restore transfection efficiency over that of the reducible polymer alone and maintain low toxicity. Chemical modifications to stabilize the disulfide bond may be explored to apply this polymer system in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by NIH 1R01NS064404, NSF DMR 0706647 and the Center for Intracellular Delivery of Biologics through the Washington State Life Sciences Discovery Fund Grant No. 2496490. Julie Shi is supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE-0718124. We gratefully thank Profs. Anthony Convertine and Patrick Stayton for generously providing the ECT chain transfer agent and Dr. Ester Kwon for preparing the pCMV-Luc2 plasmid.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aubry S, Burlina F, Dupont E, Delaroche D, Joliot A, Lavielle S, Chassaing G, Sagan S. Cell-surface thiols affect cell entry of disulfide-conjugated peptides. FASEB J. 2009;23:2956–2967. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-127563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauhuber S, Hozsa C, Breunig M, Gopferich A. Delivery of Nucleic Acids via Disulfide-Based Carrier Systems. Advanced Materials. 2009;21:3286–3306. doi: 10.1002/adma.200802453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeckle S, on Gersdorff C, van der Piepen S, Culmsee C, Wagner E, Ogris M. Purification of polyethylenimine polyplexes highlights the role of free polycations in gene transfer. Journal of Gene Medicine. 2004;6(10):1102–1111. doi: 10.1002/jgm.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breunig M, Lungwitz U, Liebl R, Goepferich A. Breaking up the correlation between efficacy and toxicity for nonviral gene delivery. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:14454–14459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703882104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke RS, Pun SH. Synthesis and Characterization of Biodegradable HPMA-Oligolysine Copolymers for Improved Gene Delivery. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2010;21:140–150. doi: 10.1021/bc9003662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Wu C, Oupicky D. Bioreducible Hyperbranched Poly(amido amine)s for Gene Delivery. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:2921–2927. doi: 10.1021/bm900724c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Lee KD. Enhanced gene delivery using disulfide-crosslinked low molecular weight polyethylenimine with listeriolysin o-polyethylenimine disulfide conjugate. J Control Release. 2008;131:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen LV, Chang CW, Kim WJ, Kim SW, Zhong Z, Lin C, Engbersen JF, Feijen J. Reducible poly(amido ethylenimine)s designed for triggers intracellular gene delivery. Bioconjug Chem. 2006;17:1233–1240. doi: 10.1021/bc0602026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Convertine AJ, Benoit DSW, Duvall CL, Hoffman AS, Stayton PS. Development of a novel endosomolytic diblock copolymer for siRNA delivery. J Control Release. 2009;133:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai FY, Sun P, Liu YJ, Liu WG. Redox-cleavable star cationic PDMAEMA by arm-first approach of ATRP as a nonviral vector for gene delivery. Biomaterials. 2010;31:559–569. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wolf HK, de Raad M, Snel C, van Steenbergen MJ, Fens M, Storm G, Hennink WE. Biodegradable poly(2-dimethylamino ethylamino)phosphazene for in vivo gene delivery to tumor cells. Effect of polymer molecular weight. Pharm Res. 2007;24:1572–1580. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9299-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng R, Yue Y, Jin F, Chen YC, Kung HF, Lin MCM, Wu C. Revisit the complexation of PEI and DNA - How to make low cytotoxic and highly efficient PEI gene transfection non-viral vectors with a controllable chain length and structure? J Control Release. 2009;140:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer D, Li YX, Ahlemeyer B, Krieglstein J, Kissel T. In vitro cytotoxicity testing of polycations: influence of polymer structure on cell viability and hemolysis. Biomaterials. 2003;24:1121–1131. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00445-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganta S, Devalapally H, Shahiwala A, Amiji M. A review of stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug and gene delivery. J Control Release. 2008;126:187–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin MA, Guo WJ, Lee RJ. Efficient gene transfer using reversibly cross-linked low molecular weight polyethylenimine. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2001;12:989–994. doi: 10.1021/bc0100455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang S, Davis M. Cationic polymers for gene delivery: Designs for overcoming barriers to systemic administration. Curr Op in Mol Ther. 2001;3:183–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RN, Burke RS, Convertine AJ, Hoffman AS, Stayton PS, Pun SH. Synthesis of statistical copolymers containing multiple functional peptides for nucleic acid delivery. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:3007–3013. doi: 10.1021/bm100806h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RN, Chu DS, Shi J, Schellinger JG, Carlson PM, Pun SH. HPMA-oligolysine copolymers for gene delivery: optimization of oligolysine length and polymer molecular weight. J Control Release. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.07.009. accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly ST, Zydney AL. Effects of intermolecular thiol-disulfide interchange reactions on bsa fouling during microfiltration. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1994;44:972–982. doi: 10.1002/bit.260440814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloeckner J, Wagner E, Ogris M. Degradable gene carriers based on oligomerized polyamines. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2006;29:414–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layman JM, Ramirez SM, Green MD, Long TE. Influence of polycation molecular weight on poly(2-dimethylaminoethylmethacrylate)-mediated DNA delivery in vitro. Biomacrolmol. 2009;10:1244–1252. doi: 10.1021/bm9000124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Zhong ZY, Lok MC, Jiang XL, Hennink WE, Feijen J, Engbersen JFJ. Linear poly(amido amine)s with secondary and tertiary amino groups and variable amounts of disulfide linkages: Synthesis and in vitro gene transfer properties. J Control Release. 2006;116:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Jiang XL, Xu L, Wang XM, Hennink WE, Zhuo RX. Novel Reduction-Responsive Cross-Linked Polyethylenimine Derivatives by Click Chemistry for Nonviral Gene Delivery. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2010;21:1827–1835. doi: 10.1021/bc100191r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lungwitz U, Breunig M, Blunk T, Gopferich A. Polyethylenimine-based non-viral gene delivery systems. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2005;60:247–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel R, Ryser HJ, Ghani F, Wu MDP. Inhibition of a reductive function of the plasma membrane by bacitracin and antibodies against protein disulfide-isomerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:904112–904116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.4112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie DL, Kwok KY, Rice KG. A potent new class of reductively activated peptide gene delivery agents. J Biol Chem. 2000a;275:9970–9977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.9970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie DL, Smiley E, Kwok KY, Rice KG. Low molecular weight disulfide cross-linking peptides as nonviral gene delivery carriers. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2000b;11:901–909. doi: 10.1021/bc000056i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister A, Anderson ME. Glutathione. Annu Rev Biochem. 1983;57:711–760. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata K, Kakizawa Y, Nishiyama N, Harada A, Yamasaki Y, Koyama H, Kataoka K. Block catiomer polyplexes with regulated densities of charge and disulfide cross-linking directed to enhance gene expression. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:2355–2361. doi: 10.1021/ja0379666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neu M, Sitterberg J, Bakowsky U, Kissel T. Stabilized nanocarriers for plasmids based upon cross-linked poly(ethylene imine) Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:3428–3438. doi: 10.1021/bm060788z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou M, Wang XL, Xu RZ, Chang CW, Bull DA, Kim SW. Novel biodegradable poly(disulfide amine)s for gene delivery with high efficiency and low cytotoxicity. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2008;19:626–633. doi: 10.1021/bc700397x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oupicky D, Ogris M, Howard KA, Dash PR, Ulbrich K, Seymour LW. Importance of lateral and steric stabilization of polyelectrolyte gene delivery vectors for extended systemic circulation. Mol Ther. 2002;5:463–472. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang D, Shah N, Zhang H, Smith SC, Parekh HS. Reducible disulfide-based non-viral gene delivery systems. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2009;9:1242–1250. doi: 10.2174/138955709789055225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Q, Zhong ZL, Zhuo RX. Disulfide cross-linked polyethylenimines (PEI) prepared via thiolation of low molecular weight PEI as highly efficient gene vectors. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2008;19:499–506. doi: 10.1021/bc7003236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubartelli A, Bajetto A, Allavena G, Wollman E, Sitia R. Secretion of thioredoxin by normal and neoplastic cells through a leaderless secretory pathway. J Chem Biol. 1992;267:24161–24164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer D, Fidelman N, Dan N, Lauffenburger D. Vector Unpacking as a Potential Barrier for Receptor-Mediated Polyplex Gene Delivery. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2000;67:598–606. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(20000305)67:5<598::aid-bit10>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son S, Singa K, Kim WJ. Bioreducible bPEI-SS-PEG-cNGR polymer as a tumor targeted nonnviral gene carrier. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6344–6354. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun WC, Davis PB. Reducible DNA nanoparticles enhance in vitro gene transfer via an extracellular mechanism. J Control Release. 2010;146:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang RP, Palumbo RN, Nagarajan L, Krogstad E, Wang C. Well-defined block copolymers for gene delivery to dendritic cells: Probing the effect of polycation chain-length. J Control Release. 2010;142:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibault M, Astolfi M, Tran-Khanh N, Lavertu M, Darras V, Merzouki A, Buschmann MD. Excess polycation mediates efficient chitosan-based gene transfer by promoting lysosomal release of the polyplexes. Biomaterials. 2011;32:4639–4646. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tous GI, Wei Z, Feng J, Bilbulian S, Bowen S, Smith J, Strouse R, McGeehan P, Casas-Finet J, Schenerman MA. Characterization of a novel modification to monoclonal antibodies: thioether cross-link of heavy and light chains. Anal Chem. 2005;77:2675–2682. doi: 10.1021/ac0500582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi MV, Laurence JS, Siahaan TJ. The role of thiols and disulfides on protein stability. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2009;10:614–625. doi: 10.2174/138920309789630534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trubetskoy V, Loomis A, Slattum P, Hagstrom J, Budker V, Wolff J. Caged DNA Does Not Aggregate in High Ionic Strength Solutions. Bioconjugate Chem. 1999;10:624–628. doi: 10.1021/bc9801530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YX, Chen P, Shen JC. The development and characterization of a glutathione-sensitive cross-linked polyethylenimine gene vector. Biomaterials. 2006;27:5292–5298. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang R, Xu N, Du F-S, Wang Y-L, Tan Y-X, Ji S-P, Liang D-H, Li Z-C. Reduction-degradable linear cationic polymers as gene carriers prepared by Cu(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition. Biomacromol. 2011;12:66–74. doi: 10.1021/bm101005j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You YZ, Manickam DS, Zhou QH, Oupicky D. A versatile approach to reducible vinyl polymers via oxidation of telechelic polymers prepared by reversible addition fragmentation chain transfer polymerization. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8:2038–2044. doi: 10.1021/bm0702049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.