Abstract

Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease comprises a heterogeneous group of peripheral neuropathies characterized by muscle weakness and wasting, and impaired sensation in the extremities. Four genes encoding an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (ARS) have been implicated in CMT disease. ARSs are ubiquitously expressed, essential enzymes that ligate amino acids to cognate tRNA molecules. Recently, a p.Arg329His variant in the alanyl-tRNA synthetase (AARS) gene was found to segregate with dominant axonal CMT type 2N (CMT2N) in two French families; however, the functional consequence of this mutation has not been determined. To investigate the role of AARS in CMT, we performed a mutation screen of the AARS gene in patients with peripheral neuropathy. Our results showed that p.Arg329His AARS also segregated with CMT disease in a large Australian family. Aminoacylation and yeast viability assays showed that p.Arg329His AARS severely reduces enzyme activity. Genotyping analysis indicated that this mutation arose on three distinct haplotypes, and the results of bisulfite sequencing suggested that methylation-mediated deamination of a CpG dinucleotide gives rise to the recurrent p.Arg329His AARS mutation. Together, our data suggest that impaired tRNA charging plays a role in the molecular pathology of CMT2N, and that patients with CMT should be directly tested for the p.Arg329His AARS mutation.

Keywords: AARS, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, CMT2N, Peripheral Neuropathy, Axonopathy

Introduction

Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease is a clinically and genetically heterogeneous disorder of the peripheral nerve characterized by distal symmetric polyneuropathy (DSP) (England, et al., 2009a; England, et al., 2009b), muscle weakness and wasting, diminished deep tendon reflexes, impaired sensation in the extremities, pes cavus, and steppage gait (Dyck and Lambert, 1968; Murakami, et al., 1996). CMT disease is a frequent cause of inherited peripheral neuropathy with an estimated frequency of 1 in 2,500 individuals worldwide (Skre, 1974). According to electrophysiological criteria, CMT disease is divided into three major subtypes (Dyck and Lambert, 1968; Nicholson and Myers, 2006). In CMT1, patients exhibit defects in myelinating Schwann cells that lead to reduced motor nerve conduction velocities (MNCVs). In CMT2, MNCV values are normal and patients exhibit axonal loss accompanied by decreased amplitudes in evoked motor nerve responses. Finally, intermediate CMT is considered when individual families contain both patients with normal MNCVs and those with reduced MNCVs (Nicholson and Myers, 2006).

Mutations in four genes encoding an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (ARS) have been implicated in CMT disease with an axonal pathogenesis: glycyl-tRNA synthetase (GARS; MIM# 600287) in CMT type 2D (CMT2D; MIM# 601472), tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase (YARS; MIM# 603623) in dominant intermediate CMT type C (CMTDIC; MIM# 608323), alanyl-tRNA synthetase (AARS; MIM# 601065) in CMT type 2N (CMT2N; MIM# 613287), and lysyl-tRNA synthetase (KARS; MIM# 601421) in CMT intermediate recessive type B (CMTIRB; MIM# 613641) (Antonellis, et al., 2003; Jordanova, et al., 2006; Latour, et al., 2010; McLaughlin, et al., 2010). ARSs are ubiquitously expressed, essential enzymes that attach amino acids to their cognate tRNA molecules in the cytoplasm and mitochondria, thus completing the first essential step of protein translation (Antonellis and Green, 2008). The extent of involvement of ARS genes in CMT and the exact pathogenic mechanism by which ARS mutations lead to peripheral neuropathy remain unclear.

In a recent study, a single AARS mutation (p.Arg329His) was found to segregate with dominant CMT disease in two French families, and haplotype analysis excluded a founder effect (Latour, et al., 2010). Interestingly, mutagenesis of the analogous amino acid in E. coli (p.Arg314Ala alaS) resulted in a ~700-fold reduction in aminoacylation activity (Ribas de Pouplana, et al., 1998). However, histidine was not tested at this amino-acid position, and the human p.Arg329His mutation has not been functionally evaluated. Furthermore, the prevalence and mutagenic mechanism of the p.Arg329His AARS mutation remain unknown. Here, we show that p.Arg329His AARS represents a recurrent, loss-of-function mutation that arises due to methylation-mediated deamination of a CpG dinucleotide.

Materials and Methods

ARS Mutation Screen

DNA samples were isolated from 363 patients diagnosed with peripheral neuropathy by collaborating physicians. DNA samples from the ClinSeq™ cohort were collected as previously described (Biesecker, et al., 2009). The appropriate review boards of each participating institution approved these studies. The AARS gene was assessed for mutations at the NIH Intramural Sequencing Center (NISC) as previously described (McLaughlin, et al., 2010). Each AARS variant was independently confirmed via PCR amplification followed by DNA sequencing analysis. Nucleotide positions are relative to the open reading frame from GenBank Accession No. NM_001605.2. Nucleotide numbering reflects cDNA position with +1 corresponding to the A of the ATG translation initiation codon in the reference sequence. Codon numbering for the AARS protein was based on the reported amino acid sequence (NCBI accession no. NP_001596.2). The initiation codon is codon 1.

NINDS Control Genotyping

A total of 576 DNA samples isolated from neurologically normal controls were obtained from the National Institute of Neurological Disease (NINDS) and Coriell Institute for Medical Research (Panel numbers NDPT079, NDPT082, NDPT084, NDPT090, NDPT093, and NDPT094) and genotyped for each AARS variant using MassARRAY® iPLEX® Gold technology (Sequenom). Briefly, multiplex locus-specific PCR reactions were performed (primer sequences available upon request) followed by primer extension assays using mass-modified dideoxynucleotide terminators. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry was used to determine the genotype for each individual using SpectroTYPER software (Sequenom).

Comparative sequence analysis

To perform comparative protein sequence analysis, we first employed the NCBI BLAST tool (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) to collect AARS protein orthologs from the indicated species. Multiple-species amino-acid sequence alignments were then generated using Clustal W2 software (Larkin, et al., 2007) and the following accession numbers: human (Homo sapiens, NP_001596.2), chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes, XP_001169474.1), mouse (Mus musculus, NP_666329.2), frog (Xenopus laevis, NP_001121342.1), zebrafish (Danio rerio, NP_001037775.1), fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster, NP_523511.2), baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae, NP_014980.1), and bacteria (Escherichia coli IAI39, YP_002408816.1).

AARS and ALA1 expression constructs

DNA constructs for aminoacylation and yeast complementation assays were generated using Gateway cloning technology (Invitrogen). The human AARS open reading frame and the Saccharomyces cerevisiae ALA1 locus (including the open reading frame and 630 base pairs of proximal promoter sequence) were PCR amplified using human cDNA and Saccharomyces cerevisiae genomic DNA, respectively. Each primer was designed to include flanking Gateway attB1 (forward) and attB2 (reverse) sequences (primers for both genes available upon request). Subsequently, purified PCR products containing each gene were recombined into the pDONR221 vector (according to the manufacturer’s instructions) to yield appropriate entry clones; the insert of each selected entry clone was sequenced to identify a clone containing each allele with no PCR-induced mutations. Mutagenesis of AARS and ALA1 was performed using the QuikChange II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) and appropriate mutation-bearing oligonucleotides. Subsequently, plasmid DNA purified from each entry clone was recombined with either a Gateway-compatible pSMT3 destination vector (for aminoacylation assays), a gateway-compatible DsRed vector (for localization studies), or a gateway-compatible pRS315 or pRS316 destination vector (for yeast complementation assays) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each resulting expression construct was analyzed by restriction enzyme digestion with BsrGI (New England Biosystems) to confirm the presence of an appropriately-sized insert.

Cell culture and differentiation

The mouse motor neuron cell line MN-1 (Salazar-Grueso, et al., 1991) was cultured in DMEM growth medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, and 2mM L-glutamine and grown at 37°C in 5% CO2. For cell differentiation, transfection studies, and antibody staining, cultured cells were counted using the Countess Automated Cell Counter (Invitrogen) and ~1.25 × 105 cells were placed into each well of a four-well polystyrene tissue culture treated glass slide (BD Biosciences). MN-1 cells were differentiated by the addition of 2 nM glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) and 833 pM GDNF receptor α-1 (GFR α-1; both from R&D Systems) to the culture medium and incubation for 48 h (Paratcha et al., 2001).

Antibody Staining

Mouse MN-1 cells were cultured at 37°C for 48 hours in differentiation medium (see above). Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100 in 1X PBS for 5 min, washed in 1X PBS, and incubated in blocking solution containing 10% normal goat serum in 1X PBS with 0.1% sodium azide (Invitrogen) for 30 min. Cells were then incubated in 10 μg/ml anti-AlaRS (B23) (sc-130683, Santa Cruz) in blocking solution for 60 min. After three washes in 1X PBS, cells were incubated in 1:200 Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti—rabbit IgG (Invitrogen) for 60 minutes. Cells were washed three times in 1X PBS, the well apparatus was removed, and slides were coated with ProLong anti-fade reagent (Invitrogen), covered, and sealed. All incubation and wash steps were performed at room temperature.

MN-1 transfection studies

Constructs expressing either wild-type or mutant AARS tagged with DsRed (described above) were transfected into MN-1 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen). For each transfection reaction, 6 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 and 250 μl of OptiMEM I minimal growth medium (Invitrogen) were combined and and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Purified plasmid DNA (4 μg) was diluted in 500 μl of OptiMEM I, combined with the above Lipofectamine–OptiMEM I mixture, and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. The entire transfection cocktail was then added to ~1.25 × 105 MN-1 cells in a 15 ml conical tube. After a 2 h incubation at 37°C, the transfection reaction was centrifuged at 2000 r.p.m. for 2 minutes and the cells were resuspended in 250 μl normal growth medium (see above) and allowed to recover for 24 h at 37°C. Cells were then washed with 1X PBS and subsequently incubated with differentiation medium (see above). After 48 h, cells were fixed as described above.

Microscopy and Image Analysis

Microscopic images were obtained using the Olympus FluoView FV500/IXLaser Scanning Confocal Microscope using Olympus Fluoview image software at the University of Michigan Microscopy and Image Analysis Core.

AARS aminoacylation assays

Wild-type and all mutant enzymes of human AARS were constructed with the SMT3 protein fused to the N-terminus to improve solubility for expression in E. coli (Mossessova and Lima, 2000). Control experiments showed that the presence of the SMT3 protein has no effect on the aminoacylation activity of these enzymes. Wild-type and mutant enzymes of human AARS were also expressed with a His-tag in the C-terminus to allow for affinity purification through a metal resin. Protein expression was achieved in E. coli strain Rosetta 2 (DE3) pLysS and purification with the nickel affinity resin was achieved according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Novagen). The T7 transcript of human tRNAAla was prepared and purified as previously described (Hou, et al., 1993), and was heat-denatured at 85°C for 3 min and annealed at 37°C for 20 min before use. Steady-state aminoacylation assays were monitored at 37°C in 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 20 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 4 mM DTT, 2 mM ATP, and 50 μM alanine with a trace of [3H]-alanine (Perkin Elmer) at a specific activity of 3693 dpm/pmole. The reaction was initiated by mixing an AARS enzyme (20–600 nM) with varying concentrations of tRNA (0.3–20 μM). Aliquots of a reaction mixture were spotted on filter papers, quenched by 5% TCA, washed, and measured for radioactivity by a liquid scintillation counter (Beckman LS6000SC). The amount of radioactivity retained on filter pads was corrected for quenching effects to reveal the amount of synthesis of Ala-tRNAAla. Steady-state kinetics was determined by fitting the initial rate of aminoacylation as a function of tRNA concentration to the Michaelis-Menten equation.

AARS editing assays

The substrate Ser-tRNAAla for analysis of post-transfer editing was prepared by 32P-labeling of the A76 nucleotide in the transcript of human tRNAAla with the CCA enzyme (Shitivelband and Hou, 2005), followed by aminoacylation with chemically synthesized Ser-DBE, using the dFx flexizyme (Murakami, et al., 2006). Deacylation assays were performed at 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 20 mM KCl, 4 mM DTT, and 10 mM MgCl2 at 37 °C, using 5 nM of an AARS enzyme and 20 μM of Ser-tRNAAla. At the indicated time points, aliquots of a deacylation reaction were removed and mixed with S1 nuclease for 30 min to digest the tRNA in the aliquots to 5′-phosphate mononucleotide. The aliquots were then run on a TLC in 0.55 M acetic acid/0.1 M NH4Cl for 30 min to separate [32P]-seryl-AMP from [32P]-AMP. Quantification of the two products by a phosphorimager and analysis of the ratio of [Ser-AMP] versus [AMP] determined the extent of Ser-tRNAAla remained after the editing reaction.

Yeast viability assays

A commercially-available diploid heterozygous ala1Δ yeast strain (MATa/α, his3Δ1/his3Δ1, leu2Δ0/leu2Δ0, LYS2/lys2Δ0, met15Δ0/MET15, ura3Δ0/ura3Δ0; Open Biosystems) was transformed with a URA3-bearing pRS316 vector containing wild-type ALA1 (see above). Lithium acetate transformations were performed at 30°C using 200 ng of plasmid DNA, as previously described (Green, et al., 1999). Transformation reactions were grown on yeast medium lacking uracil. Subsequently, sporulation and tetrad dissections were performed to obtain a haploid ala1Δ strain that also contains the wild-type ALA1 pRS316 maintenance vector. Briefly, the transformed diploid ala1Δ strain was patched twice onto pre-sporulation plates [(5% D-glucose (Fisher Scientific), 3% nutrient broth (Becton, Dickinson and Company), 1% yeast extract (Acros Organics), and 2% agar (Teknova)]. One μl of cells was then transferred into 2 mLs of supplemented liquid sporulation medium [(1% potassium acetate (Fisher Scientific), 0.005% zinc acetate (Fisher Scientific), 1X ura supplement (MP Biomedicals), 1X his supplement (MP Biomedicals), and 1X leu supplement (MP Biomedicals)] and incubated for 5 days at 25°C followed by 3 days at 30°C. Sporulated strains were dissected using a MSM 400 dissection microscope (Singer Instruments), and plated on yeast extract, peptone, and dextrose (YPD) plates (Becton, Dickinson and Company).

Resulting spores were individually patched onto solid growth medium containing Geneticin (G418) or 0.1% 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA), or media lacking uracil (Teknova). Two spores that grew on G418 and yeast medium lacking uracil yet did not grow on 5-FOA medium were selected for use in the yeast viability assays. Two resulting haploid ala1Δ strains bearing a wild-type ALA1 pRS316 maintenance vector were then transformed with LEU2-containing pRS315 constructs containing wild-type or mutant ALA1 (described above) and grown on medium lacking uracil and leucine (Teknova). For each transformation, five colonies were selected for additional analysis. Each colony was diluted in 100 μl H2O, then further diluted 1:10 and spotted on growth medium containing 0.1% 5-FOA (Teknova), incubated for 3 days at 30°C, and growth was assessed by visual inspection. Because 5-FOA is toxic to yeast cells bearing a functional URA3 allele, only cells that lost the URA3 maintenance plasmid and for which the LEU2 test plasmid could complement the chromosomal ala1Δ allele were expected to grow.

Haplotype analysis

Microsatellite markers D16S3050, D16S397 and D16S3106 were genotyped in CMT243 and three CEPH Controls: 102-1, 1331-1, and 1332-1 (Coriell). Primer information for these markers was obtained from the UCSC Genome Browser. The forward primers were 5′ labeled with the 6-FAM fluorochrome. Microsatellite markers were amplified using touchdown PCR protocols in 10-uL reactions containing 10 ng DNA, 1X Immomix (Bioline), 8 pmol primer, and 1X PCR enhancer (Invitrogen). The markers were sent to the Australian Cancer Research Foundation (ACRF) Facility, Garvan Institute of Medical Research (New South Wales, Australia) for size fractionation using the GeneScan LIZ 600 size standard. Genotypes were analyzed using GeneMarker version 5.1 software (SoftGenetics LLC).

CpG dinucleotide evaluation and sodium bisulfite sequencing

The CpG dinucleotide content of the AARS locus (GenBank accession number NM_001605.2) was evaluated using EMBOSS CpG Plot (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/emboss/cpgplot/) (Rice, et al., 2000) using the follwing criteria: Observed/Expected ratio > 0.60, percent G + percent C > 50.00, and Length >100. Two genomic DNA samples from unaffected individuals were treated with sodium bisulfite using the EpiTect Bisulfite Kit, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen). Briefly, 2μg of genomic DNA was treated with sodium bisulfite. Bisulfite-treated DNA was bound to the membrane of an EpiTect spin column, washed, desulfonated, washed, and eluted. JumpStart Taq DNA polymerase (Sigma) along with PCR primers compatible with sodium bisulfite-converted sequence for AARS exon 7: [Fwd (5′-aagtttgttttttaaagggttgtttt-3′) and Rev (5′-ccatcaaccaataccacaataataat-3′)], AARS exon 8: [Fwd (5′-ttaagataaaatttttagttgggaa-3′) and Rev (5′-aaaaataaacctaccaaaaactaaac-3′)], AARS exon 9: [Fwd (5′-tgaagaaggatttagatatggtgaag-3′) and Rev (5′-aaaaacataaaaacccacaatcaat-3′)], and a region at SOX3: [Fwd: (5′-agggagtatttattttttttgagtag-3′) and Rev (5′-aaaaaccccaaaatacacaattcta-3′)] were used to amplify a 162 base pair product encompassing AARS exon 7, a 177 base pair product encompassing AARS exon 8, a 230 bp product encompassing AARS exon 9, and a 197 base pair product amplifying a CpG island in SOX3. The PCR products were electrophoresed through a 1% agarose gel strained with ethidium bromide. Subsequently, PCR products were excised from the gel and DNA was isolated using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Amplicons were cloned into the pCR4-TOPO TA vector using the TOPO TA Cloning Kit for Sequencing (Invitrogen). Twenty resulting clones from each control DNA sample were selected for sequencing at each locus. Bisulfite sequencing data was analyzed using Sequencher DNA Sequence Assembly software (Gene Codes) and BiQ Analyzer software (Bock, et al., 2005).

Results

Identification of AARS Variants

To further evaluate the role of AARS mutations in CMT disease, we performed PCR-based DNA sequencing analysis of each AARS coding exon in DNA samples isolated from 363 patients with CMT and no known disease-causing mutation. This investigation revealed six missense AARS variants: p.Arg329His (R329H), p.Thr562Ile (T562I), p.Arg729Trp (R729W), p.Glu778Ala (E778A), p.Gly931Ser (G931S), and p.Lys967Met (K967M) (Table 1). To determine the frequency of each variant, we genotyped DNA samples isolated from neurologically unaffected individuals of European decent (NINDS/Coriell). The R329H and E778A AARS variants were not identified in 1,086 and 954 chromosomes tested, respectively. Neither variant was detected in 802 chromosomes tested from the ClinSeq™ cohort (Biesecker, et al., 2009). Conversely, T562I, R729W, and G931S AARS were detected in 8 out of 1,088 (frequency= 0.0073), 2 out of 1,090 (frequency= 0.0018), and 11 out of 1,106 chromosomes (frequency= 0.0099), respectively (Table 1). The K967M variant is present in dbSNP (rs35744709). Each of the AARS variants found in the neurologically normal controls were also identified in the ClinSeq™ cohort (Table 1) (Biesecker, et al., 2009). Together, these data indicate that R329H and E778A are not common polymorphisms.

Table 1.

Identification of AARS variants in patients with CMT

| cDNA Change1 | Amino-Acid Change2 | dbSNP Accession No. | NINDS Control Chromosomes | ClinSeq™ Chromosomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.986G>A | R329H | NP | 0/1086 | 0/802 |

| c.1685C>T | T562I | NP | 8/1088 | 4/802 |

| c.2185C>T | R729W | NP | 2/1090 | 1/788 |

| c.2333A>C | E778A | NP | 0/954 | 0/802 |

| c.2791G>A | G931S | NP | 11/1106 | 12/802 |

| c.2900A>T | K967M | rs35744709 | ND | 12/752 |

Nucleotide positions are relative to the open reading frame from GenBank Accession No. NM_001605.2. Nucleotide numbering reflects cDNA numbering with +1 corresponding to the A of the ATG translation initiation codon in the reference sequence, according to journal guidelines.

Amino-acid positions are relative to GenBank Accession No. NP_001596.2. The initiation codon is codon 1.

NP—Not Present

ND—Not Done

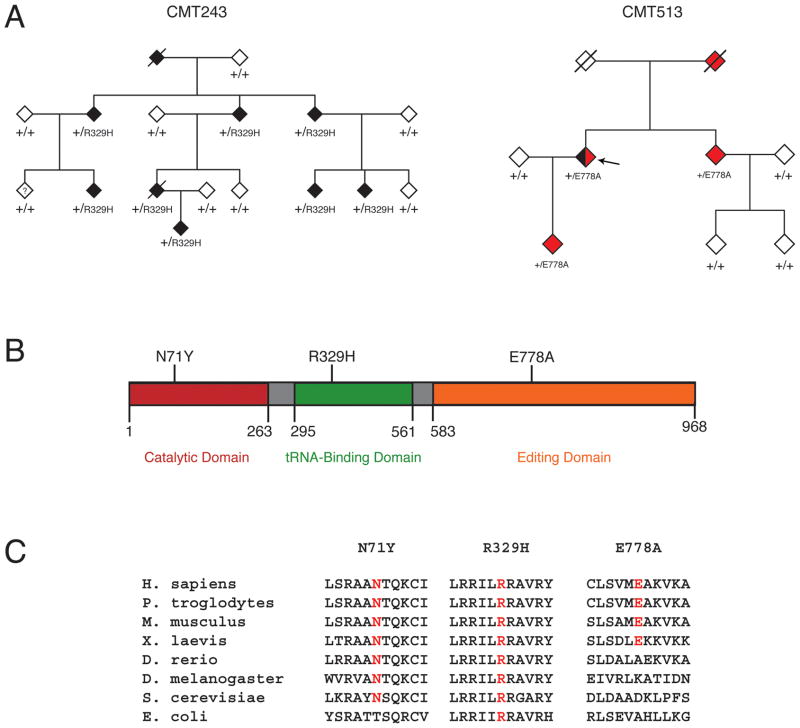

The R329H variant (c.986G>A) was identified in family CMT243, a large Australian kindred including 9 individuals affected with CMT disease (Fig. 1A and Supp. Fig. S1). Affected individuals exhibited early-onset axonal neuropathy with variable sensorineural deafness. Progressive gait difficulty, foot drop, pes cavus, and hammer toes were also reported. Nerve conduction velocities were within the intermediate range and audiology showed mild to moderate high frequency sensory neural loss. Importantly, samples from affected individuals in CMT243 were negative for mutations in other genes previously implicated in CMT disease, including PMP22 (MIM# 601097), MFN2 (MIM# 608507), GDAP1 (MIM# 606598), and EGR2 (MIM# 129010).

Figure 1.

Segregation, localization, and conservation of AARS variants. A: Genotyping was performed to determine the segregation of AARS variants with disease in families with CMT. Filled symbols represent affected individuals, with black indicating a diagnosis of CMT and red indicating a diagnosis of rippling muscles and cramps. Empty symbols indicate unaffected individuals. Where applicable, the individual’s genotype is indicated with the amino-acid change or + (for a wild-type allele). Slashes indicate deceased individuals, the question mark indicates an unknown diagnosis, and the arrow indicates the proband in family CMT513. All individuals have been designated with a diamond symbol to protect identities. B: Each variant was mapped to the known functional domains of the AARS protein indicated in red (catalytic domain), green (tRNAAla binding domain), and orange (editing domain). The position of each domain along the protein is indicated below the cartoon. C: Multiple-species protein alignments were generated to assess the conservation of each affected amino-acid position. For each of the three detected variants, the affected amino acid is shown along with the flanking AARS protein sequence in multiple, evolutionarily diverse species (indicated on the left). Note that each specific amino-acid change is given at the top, with conservation indicated in red for each protein sequence.

The E778A variant (c.2333 A>C) was identified in CMT513, an Australian family that includes a proband with sporadic axonal CMT, rippling muscles, and cramps, and three additional individuals affected only with rippling muscles and cramps (Fig. 1A and Supp. Fig. S1). Affected individuals exhibited cramps at night with rippling and twitching muscles at rest. Conduction studies in the proband (Fig. 1A; arrow) showed a motor and sensory axonal neuropathy. Clinical examination revealed absent reflexes, wasting of the feet, and mild distal sensory loss in the lower limbs. DNA samples from affected individuals from family CMT513 tested negative for PMP22 gene mutations. Furthermore, the proband from this family tested negative for mutations in CAV3 (MIM# 601253), which is commonly mutated in patients with rippling muscle disease (Betz, et al., 2001).

In addition to the above-mentioned variants, a third AARS variant [p.Asn71Tyr (N71Y)] was recently identified in a Taiwanese family with axonal CMT disease (Lee, et al., 2011). Thus, we also included N71Y AARS in our functional analyses (see below).

N71Y and R329H AARS affect highly-conserved amino-acid residues

To determine if the identified AARS variants reside at amino acid residues important for enzyme function, we mapped each affected AARS residue onto the protein. Asparagine 71 is located within the catalytic domain of the enzyme, arginine 329 resides within the tRNA-binding domain, and glutamic acid 778 is located in the editing domain of the protein, which ensures the fidelity of tRNAALA charging (Fig. 1B). The evolutionary conservation of each affected AARS residue was assessed by aligning AARS protein orthologs from multiple species. Asparagine 71 is conserved among all eight species analyzed with the exception of bacteria (Fig. 1C). Arginine 329 is conserved in all eight species analyzed, including yeast and bacteria (Fig. 1C). In contrast, glutamic acid 778 is not conserved among vertebrate species; note that an alanine is permissive in the zebrafish ortholog of AARS (Fig. 1C). Thus, the N71Y and R329H AARS variants alter amino-acid residues that are conserved between humans and single-celled organisms, and that reside within critical functional domains, suggesting that these variants may impair enzyme function.

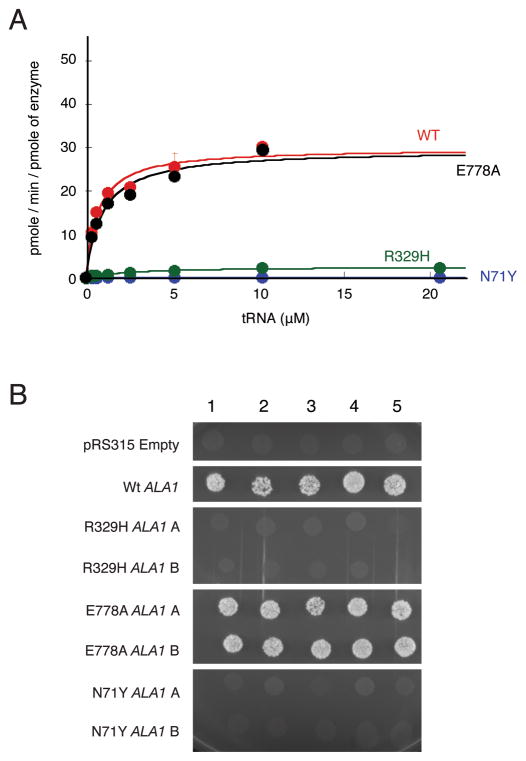

N71Y and R329H AARS display impaired enzyme activity in vitro

AARS catalyzes the aminoacylation of tRNAAla in the cytoplasm via a two-step aminoacylation reaction (Antonellis and Green, 2008). Previous aminoacylation analyses performed using disease-associated GARS, YARS, and KARS mutations showed that the majority show impaired aminoacylation activity (Cader, et al., 2007; Jordanova, et al., 2006; McLaughlin, et al., 2010; Nangle, et al., 2007; Storkebaum, et al., 2009; Xie, et al., 2007). However, the AARS mutations described above have not been tested for an effect on aminoacylation activity. We therefore tested the ability of each human AARS protein variant to catalyze aminoacylation in vitro. Human cytoplasmic tRNAAla was synthesized via in vitro transcription and used as a substrate for aminoacylation in the presence of tritium-labeled alanine. Analyses of the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) of aminoacylation showed that N71Y and R329H AARS severely impaired enzyme activity, resulting in a 4,130-fold and 50-fold decrease in catalytic efficiency compared to wild-type AARS, respectively (Fig. 2A and Table 2). In contrast, E778A AARS showed catalytic activity similar to the wild-type enzyme (Fig. 2A), and the non-pathogenic T562I AARS enzyme that results from an AARS polymorphism was not associated with decreased enzyme activity (data not shown). In addition, analysis of the editing activity of E778A AARS showed that this variant enzyme had similar editing activity as the wild-type enzyme (Supp. Fig. S2). Thus, the N71Y and R329H AARS alleles encode enzyme subunits with severely reduced charging capacity in vitro.

Figure 2.

Functional characterization of AARS variants. A: Aminoacylation of tRNAAla with alanine by AARS enzymes. Analysis of the rate of aminoacylation (pmole/min/pmole of enzyme) as a function of tRNA concentration for the wild-type AARS enzyme (red) and the mutants N71Y (blue), and R329H (green), and E778A (black) after fitting the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation. Values represent the average of two independent experiments, and error bars indicate the standard deviation. B: Five representative cultures of each yeast strain (indicated along the top of the panel) were inoculated and grown on solid growth medium containing 5-FOA. Each strain was previously transfected with a vector containing no insert (pRS315 Empty), wild-type ALA1 (Wt ALA1), or the indicated mutant form of ALA1 that modeled a human AARS mutation (see Table 3). Two independently generated mutant-bearing constructs were analyzed (indicated as ‘A’ and ‘B’ on the left side of the panel). Before inoculating on 5-FOA-containing medium, each strain was resuspended in 100μL water, then diluted 1:10.

Table 2.

Aminoacylation kinetics of AARS protein variants

| Km (mM) | kcat(s−1) | kcat/Km (mM−1s−1) | Ratio to WT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 0.70 ± 0.21 | 0.54 ± 0.04 | 0.81 ± 0.19 | 1 |

| N71Y | 2.9 ± 0.7 | 0.0006 ± 0.0004 | 0.0002 ± 0.0001 | 1/4,130 |

| R329H | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 0.047 ± 0.0001 | 0.016 ± 0.001 | 1/50 |

| E778A | 0.89 ± 0.08 | 0.53 ± 0.001 | 0.60 ± 0.05 | 1/1.4 |

N71Y and R329H AARS do not complement deletion of the yeast ortholog

Many disease-associated GARS, YARS, and KARS mutations are unable to complement deletion of the corresponding yeast orthologs (Antonellis, et al., 2006; Jordanova, et al., 2006; McLaughlin, et al., 2010). To further assess for mutation-associated defects in AARS enzyme function, we modeled each AARS variant in the yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) ortholog ALA1 (Table 3) and determined the ability of each variant to complement the deletion of ALA1 compared to the wild-type yeast gene. A haploid yeast strain with endogenous ALA1 deleted (ala1Δ) was maintained via transformation of a wild-type copy of ALA1 on a URA3-bearing plasmid (pRS316). Experimental (wild-type and mutant) ALA1 alleles were generated on a LEU2-bearing vector (pRS315) and transformed into the strain described above. Viability was evaluated by analysis of growth on solid media containing 5-fluoroorotic acid. Two experimental vectors were prepared for each mutant and 5 colonies from each transfection assay were evaluated. An insert-free pRS315 construct was unable to rescue the ala1Δ allele, whereas wild-type ALA1 was able to fully complement the ala1Δ allele (Fig. 2B). These data are consistent with ALA1 being an essential gene, and the wild-type experimental ALA1 vector harboring a functional allele, respectively. The E778A ALA1 allele allowed growth in a manner consistent with wild-type ALA1. In contrast, N71Y and R329H ALA1 were unable to rescue the ala1Δ allele. Combined, these data indicate that N71Y and R329H AARS enzymes have strongly reduced functional activity.

Table 3.

Human AARS variants modeled in the yeast ortholog ALA1

Amino-acid coordinates correspond to GenBank accession number NP_001596.2

Amino-acid coordinates correspond to GenBank accession number NP_014980.1

Disease-associated YARS variants have a dominant-negative effect when modeled in the yeast ortholog TYS1 (Jordanova, et al., 2006). To test N71Y, R329H, and E778A ALA1 for a dominant-negative effect, we performed growth curve analysis on the haploid yeast strains (described above) before selection on 5-FOA (i.e., strains that harbor two ALA1 expression constructs: two wild-type, or one wild-type and one mutant). Similar experiments were performed on strains expressing each mutant ALA1 variant from a strong promoter (ADH1). In both experiments, no differences were seen in growth patterns between strains expressing a mutant ALA1 variant and those expressing wild-type ALA1 (data not shown). Therefore, AARS mutations do not appear to exert a dominant-negative effect when modeled in yeast.

E778A AARS does not mislocalize in vitro

Several mutant GARS and YARS proteins have been shown to mislocalize in vitro (Antonellis, et al., 2006; Jordanova, et al., 2006). Because the E778A variant does not impair AARS function in either aminoacylation or yeast viability assays, we sought to determine if the E778A AARS protein is mislocalized in neurons, We first examined the endogenous localization of the AARS protein in the mouse motor neuron cell line MN-1 after differentiation and staining against anti-AARS (Salazar-Grueso et al., 1991). Confocal microscopy revealed diffuse localization throughout the cell and nucleus, extending into the neurite projections (Supp. Fig. S3A–B). Notably, this localization pattern is in contrast to the distinct granular staining of the endogenous GARS and YARS proteins (Antonellis, et al., 2006; Jordanova, et al., 2006). Subsequently, we assessed the localization of E778A AARS by transfecting constructs expressing either wild-type or E778A AARS C-terminally-tagged with DsRed in MN-1 cells and examining the localization pattern after differentiation. Similar to wild-type AARS, E778A AARS was localized diffusely throughout the cell and neurite projections (Supp. Fig. S3C–D; arrows). These data indicate that E778A AARS is not grossly mislocalized in neurons at the resolution of confocal microscopy.

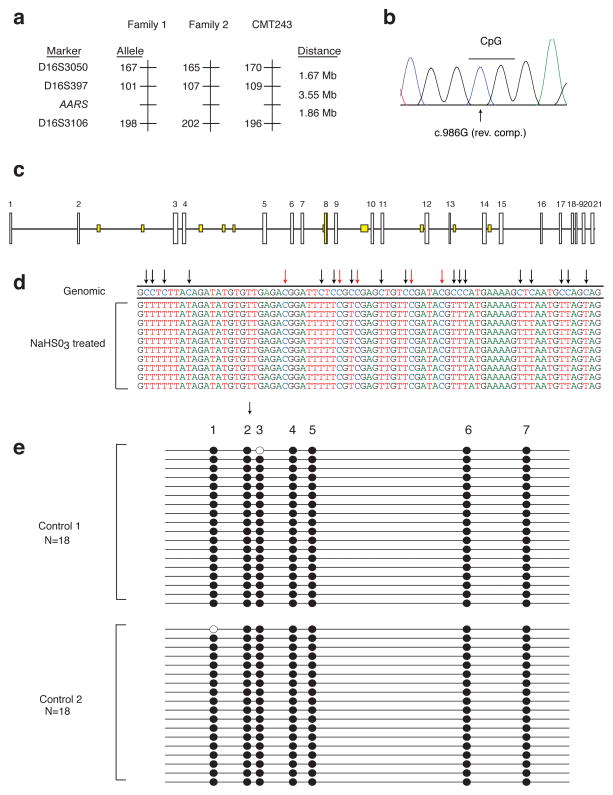

R329H AARS is a recurrent mutation

The R329H AARS variant has now been identified in three families with CMT disease from different world populations [(Latour, et al., 2010) and current study]. To determine if the Australian family described herein shares a haplotype with either of the two previously-reported French families, we performed haplotype analysis on individuals from family CMT243. These studies revealed that the R329H AARS mutation resides on three distinct haplotypes in each of the three families (Fig. 3A), consistent with this variant representing a recurrent mutation.

Figure 3.

R329H AARS is a recurrent mutation. A: Haplotype analysis was performed along chromosome 16 in family CMT243 and compared to the published data for the previously identified families with the R329H AARS mutation (Family 1 and Family 2). The three genotyped markers and AARS locus are indicated on the left, along with the alleles identified on each disease-associated haplotype (in base pairs). The distance between each locus is indicated in megabases (Mb). B: The codon affected by the R329H AARS variant harbors a CpG dinucleotide. A representative trace (in the reverse-complement) of the region surrounding the R329H codon is shown. The CpG is indicated with a line and the affected cytosine is indicated with an arrow. C: The AARS locus was computationally evaluated for CpG dinucleotide content (see methods). Each AARS exon number is indicated along the top of the panel, with vertical white boxes representing coding exons and horizontal lines representing introns. Areas with at least 100 base pairs containing an observed/expected CpG dinucleotide ratio > 60% and GC content >50% are indicated in yellow. Note that AARS exon 8 is the only coding region to meet these criteria. D: The methylation status of CpG dinucleotides in AARS exon 8 was evaluated via bisulfite (NaHSO3) treated DNA sequencing analysis. The DNA sequence from ten representative clones harboring AARS exon 8 after bisulfite treatment are shown, with the genomic consensus sequence (‘Genomic’) provide along the top. Converted cytosines are indicated with black arrows and non-converted cytosines are indicated with red arrows. Note that all non-CpG cytosines are converted to thymines, while all CpG cytosines remain unchanged indicating that they are methylated. E: AARS exon 8 harbors multiple, methylated cytosines in CpG dinucleotides. A representation of bisulfite sequencing products of the seven CpGs (indicated along the top of the panel) residing in AARS exon 8 is shown for two control individuals (Control 1 and Control 2). Eighteen clones were analyzed for each control. Filled circles indicate methylated CpGs. The arrow indicates the affected CpG giving rise to R329H AARS.

To assess the mechanism of the recurrent R329H AARS mutation, we examined the DNA sequence surrounding the c.986 G>A change. Interestingly, when the protein-coding DNA sequence is observed in the reverse-complemented state, the affected nucleotide (c.986G) is a cytosine within a CpG dinucleotide (Fig. 3B). It is estimated that ~80% of CpG cytosines are methylated to form 5-methylcytosine (5mC) in human cells (Ehrlich, et al., 1982). Importantly, 5mCs are known to be mutational “hotspots” (Cooper and Youssoufian, 1988; Coulondre, et al., 1978) that arise due to spontaneous deamination of the 5mC to form thymine (Selker and Stevens, 1985), and if this event were to occur at the CpG dinucleotide indicated in Figure 3B, this would result in the c.986 G>A change on the opposite, coding strand of AARS exon 8. To address this possibility, we evaluated the CpG dinucleotide content of the AARS locus using EMBOSS CpGPlot (Fig. 3C) (Rice, et al., 2000). Interestingly, in contrast to the remaining AARS coding exons, the exon encoding R329 (exon 8) has a high CpG dinucleotide content (6.48%; Fig. 3C).

Sodium bisulfite DNA sequencing is a common approach to identify 5mCs in genomic DNA. To determine if the R329H AARS variant might be generated via methylation-mediated deamination of the identified CpG dinucleotide, we PCR-amplified a genomic region surrounding AARS exon 8 from two independent human DNA samples treated with sodium bisulfite. Subsequently, each DNA sample was subjected to subcloning, and eighteen clones from each sample were selected for DNA sequence analysis. Visual examination of the DNA sequencing data showed that >99% of non-CpG cytosines (Fig. 3D, black arrows) were converted to thymidine. In contrast, cytosines residing in CpG dinucleotides were largely unconverted and remained cytosines (Fig. 3D, red arrows). To predict the methylation status of each cytosine in AARS exon 8, the sequence data from each clone was analyzed with BiQ Analyzer software (Bock, et al., 2005). A total of 28 cytosines were analyzed, including 7 cytosines residing in CpG dinucleotides. In 94% of the clones examined, all 7 CpG cytosines were methylated, including the mutated cytosine that gives rise to R329H AARS (Fig. 3E).

To ensure the validity of the above-mentioned data, we employed the BiQ Analyzer software to assess similar DNA sequencing data generated from PCR products encompassing AARS exon 7 and 9, as well as a third, unlinked and previously-characterized CpG island at the X-linked SOX3 locus (Cotton, et al., 2009). More than 90% of the CpGs in AARS exon 7 are methylated, 11% of CpGs in AARS exon 9 are methylated (Supp. Fig. S4A and S4B), and the SOX3 locus displayed the expected methylation patterns—DNA isolated from a female individual contained higher levels of methylation than DNA isolated from a male individual (Supp. Fig. S4C).

Finally, we predicted the consequences of deamination of each 5mC within AARS exon 8 to determine if C>T transitions could give rise to additional pathogenic amino-acid changes. Because the transition could occur on either stand, there are 14 possible deamination consequences. Of these, 11 are predicted to affect the AARS amino acid sequence, including 2 that would result in a stop codon (Table 4). Combined, these data support the notion that R329H AARS is a recurrent mutation generated via 5mC deamination of a CpG dinucleotide on the non-coding DNA strand. Furthermore, AARS exon 8 is predicted to be a highly mutable region with potentially detrimental consequences, and should be closely scrutinized for mutations in patients with dominant axonal CMT.

Table 4.

Predicted consequences for deaminated methyl-CpGs in AARS exon 8

| CpGa | Affected Amino Acid | Predicted Change |

|---|---|---|

| 1b | R326 | W |

| 1c | R326 | Q |

| 2b | R329 | C |

| 2c | R329 | H |

| 3b | R330 | * |

| 3c | R330 | Q |

| 4b | R333 | * |

| 4c | R333 | Q |

| 5c | A335 | T |

| 6b | T348 | M |

| 7c | V354 | I |

Numbers refer to the annotations presented in Figure 3E.

CpG on coding strand

CpG on non-coding strand

Discussion

Here, we present genetic and functional data showing that R329H AARS is a recurrent, loss-of-function mutation that causes dominant axonal Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease. In addition, we present functional data indicating that the N71Y AARS variant also results in a loss of AARS enzyme function; these data are consistent with this allele being pathogenic in a Taiwanese family with dominant axonal CMT disease (Lee, et al., 2011). Importantly, these data provide key insight into the molecular pathology of CMT-related aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (ARS) gene mutations. To date, four aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases have been implicated in CMT disease characterized by an axonal pathology (Antonellis, et al., 2003; Jordanova, et al., 2006; Latour, et al., 2010; McLaughlin, et al., 2010). Each glycyl-tRNA synthetase (GARS) mutation tested causes impaired tRNA charging capacity and/or mislocalization in neurons compared to the wild-type enzyme (Antonellis, et al., 2006; Cader, et al., 2007; Nangle, et al., 2007; Xie, et al., 2007). Furthermore, all three disease-associated tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase (YARS) mutations impair the first or second step of the aminoacylation reaction, and also affect the proper localization of YARS in cultured neurons (Jordanova, et al., 2006; Storkebaum, et al., 2009). Finally, two lysyl-tRNA synthetase (KARS) mutations identified in a compound heterozygote patient with CMT disease result in a null allele and a hypomorphic allele, which would dramatically reduce the production of Lys-tRNALYS molecules (McLaughlin, et al., 2010). Importantly, these loss-of-function characteristics have not been observed upon analysis of non-pathogenic ARS variants [this study and reference (McLaughlin, et al., 2010)]; however, additional ARS variants in this class need to be evaluated. Combined with the R329H AARS data presented here, these observations strongly suggest that there is an impaired tRNA charging component to the pathophysiology of ARS-related CMT disease. One possibility is that the axonopathy phenotype is caused by a dominant-negative effect of ARS mutations that greatly reduces (e.g., more than 50%) tRNA charging capacity, which is supported by findings that: (1) The majority of ARS-related CMT phenotypes are dominant; (2) Most ARS mutations are missense amino-acid changes; (3) ARS enzymes implicated in CMT to date act as oligomers; and (4) Haploinsufficiency of Gars does not cause axonopathy in a mouse model. However, a toxic gain-of-function unrelated to tRNA charging cannot yet be ruled out and, moving forward, it will be important to study GARS, YARS, KARS, and AARS mutants to tease out the precise molecular pathology of ARS-related CMT disease.

Our mutation screen of the AARS gene also identified the E778A variant, which segregated with dominant rippling muscle disease in a family that included a proband with the additional phenotype of axonal CMT disease. Although E778A was absent in over 950 chromosomes from neurologically normal control individuals, family CMT513 is too small for linkage analysis and we were unable to identify any functional consequences of E778A AARS in aminoacylation, yeast complementation, or protein localization assays. However, this finding raises interesting questions about possible genotype/phenotype correlations associated with AARS mutations. For example, homozygosity for an A734E mutation in the editing domain of the mouse Aars gene causes ataxia and hair follicle degeneration in the sti mouse (Lee, et al., 2006). Biochemical analyses showed that the A734E AARS enzyme has tRNA charging activity consistent with wild-type AARS, however, the editing capacity of the enzyme was decreased (Lee, et al., 2006). The E778A AARS variant described here resides within the editing domain of the AARS enzyme, and while we were unable to detect an editing defect associated with the E778A enzyme, it will be important to determine if E778A AARS causes rippling muscle disease via another pathogenic mechanism (e.g., using animal models). One possibility is that E778A AARS affects some secondary, non-canonical function of the AARS enzyme in neuronal or muscle tissues. Indeed, ARSs are known to possess a wide variety of non-canonical functions in humans including: HIV virion packaging, RNA biogenesis, apoptotic inhibition, angiogenic signaling, and immune response stimulation (Antonellis and Green, 2008). However, at this point E778A AARS represents a rare variant whose potential pathogenicity remains to be established.

Our haplotype and bisulfite DNA sequence analyses indicate that R329H AARS is a recurrent mutation and suggest that the prevalence of this mutation in CMT disease should be further investigated. Recurrent, methylation-mediated and disease-associated mutations have been described in other genes including TP53 (MIM# 191170), PAH (MIM# 612349), and MECP2 (MIM# 300005) (Greenblatt, et al., 1994; Murphy, et al., 2006; Wan, et al., 1999). These findings often dictate mutation-specific screening of other, relevant patients with no known mutation. We also discovered that six additional CpGs in AARS exon 8 are methylated, suggesting that this exon has the capacity to be highly mutable. Combined, these data have important clinical implications. The recurrent nature of the R329H AARS mutation, and the fact that the affected CpG is constitutively methylated strongly suggest that all patients with axonal CMT disease and no known mutation should be screened for the R329H AARS mutation. Furthermore, it may be prudent to thoroughly assess each of the remaining methylated CpGs in AARS exon 8 in similar patients to fully evaluate the AARS gene for CMT-associated mutations.

The data presented here improve our understanding of the role of AARS mutations in CMT disease. Specifically, they indicate that AARS mutations may act via impaired enzyme function, that the AARS locus should be assessed for mutations in patients with CMT disease, and further support the notion that all 37 human genes encoding an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase can be considered candidate genes for neurodegenerative diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the patients and their families for participating in this study. We thank Suzanne Genik, Ellen Pederson, Bob Lyons, and the University of Michigan DNA Sequencing Core for sequencing and genotyping assistance; Chris Chou and Tom Glaser for advice on bisulfite sequencing and SOX3 primers; Miriam Meisler and her laboratory for thoughtful discussions; and Eric Green for assistance with patient DNA sequencing. This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke [R00NS060983 to A.A., U54NS065712 to S.Z., and R01NS052767 to S.Z.]; the Muscular Dystrophy Association [157681 to Y.-M.H.]; the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute (National Institutes of Health); the Rackham Merit Fellowship [to H.M.M.]; and the National Institutes of Health Genetics Training Grant [T32 GM007544-32 to H.M.M.].

Footnotes

Supporting Information for this preprint is available from the Human Mutation editorial office upon request (humu@wiley.com)

References

- Antonellis A, Ellsworth RE, Sambuughin N, Puls I, Abel A, Lee-Lin SQ, Jordanova A, Kremensky I, Christodoulou K, Middleton LT, et al. Glycyl tRNA synthetase mutations in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2D and distal spinal muscular atrophy type V. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1293–9. doi: 10.1086/375039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonellis A, Green ED. The role of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases in genetic diseases. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2008;9:87–107. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonellis A, Lee-Lin SQ, Wasterlain A, Leo P, Quezado M, Goldfarb LG, Myung K, Burgess S, Fischbeck KH, Green ED. Functional analyses of glycyl-tRNA synthetase mutations suggest a key role for tRNA-charging enzymes in peripheral axons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10397–406. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1671-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz RC, Schoser BG, Kasper D, Ricker K, Ramirez A, Stein V, Torbergsen T, Lee YA, Nothen MM, Wienker TF, et al. Mutations in CAV3 cause mechanical hyperirritability of skeletal muscle in rippling muscle disease. Nat Genet. 2001;28:218–9. doi: 10.1038/90050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesecker LG, Mullikin JC, Facio FM, Turner C, Cherukuri PF, Blakesley RW, Bouffard GG, Chines PS, Cruz P, Hansen NF, et al. The ClinSeq Project: piloting large-scale genome sequencing for research in genomic medicine. Genome Res. 2009;19:1665–74. doi: 10.1101/gr.092841.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock C, Reither S, Mikeska T, Paulsen M, Walter J, Lengauer T. BiQ Analyzer: visualization and quality control for DNA methylation data from bisulfite sequencing. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:4067–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cader MZ, Ren J, James PA, Bird LE, Talbot K, Stammers DK. Crystal structure of human wildtype and S581L-mutant glycyl-tRNA synthetase, an enzyme underlying distal spinal muscular atrophy. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2959–64. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper DN, Youssoufian H. The CpG dinucleotide and human genetic disease. Hum Genet. 1988;78:151–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00278187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton AM, Avila L, Penaherrera MS, Affleck JG, Robinson WP, Brown CJ. Inactive X chromosome-specific reduction in placental DNA methylation. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3544–52. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulondre C, Miller JH, Farabaugh PJ, Gilbert W. Molecular basis of base substitution hotspots in Escherichia coli. Nature. 1978;274:775–80. doi: 10.1038/274775a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyck PJ, Lambert EH. Lower motor and primary sensory neuron diseases with peroneal muscular atrophy. II. Neurologic, genetic, and electrophysiologic findings in various neuronal degenerations. Arch Neurol. 1968;18:619–25. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1968.00470360041003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich M, Gama-Sosa MA, Huang LH, Midgett RM, Kuo KC, McCune RA, Gehrke C. Amount and distribution of 5-methylcytosine in human DNA from different types of tissues of cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:2709–21. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.8.2709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England JD, Gronseth GS, Franklin G, Carter GT, Kinsella LJ, Cohen JA, Asbury AK, Szigeti K, Lupski JR, Latov N, et al. Practice Parameter: evaluation of distal symmetric polyneuropathy: role of autonomic testing, nerve biopsy, and skin biopsy (an evidence-based review). Report of the American Academy of Neurology, American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine, and American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Neurology. 2009a;72:177–84. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000336345.70511.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England JD, Gronseth GS, Franklin G, Carter GT, Kinsella LJ, Cohen JA, Asbury AK, Szigeti K, Lupski JR, Latov N, et al. Practice Parameter: evaluation of distal symmetric polyneuropathy: role of laboratory and genetic testing (an evidence-based review). Report of the American Academy of Neurology, American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine, and American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Neurology. 2009b;72:185–92. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000336370.51010.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green ED, Birren B, Klapholz S, Myers RM, Riethman H, Roskams J. Genome analysis: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Greenblatt MS, Bennett WP, Hollstein M, Harris CC. Mutations in the p53 tumor suppressor gene: clues to cancer etiology and molecular pathogenesis. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4855–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou YM, Westhof E, Giege R. An unusual RNA tertiary interaction has a role for the specific aminoacylation of a transfer RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:6776–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordanova A, Irobi J, Thomas FP, Van Dijck P, Meerschaert K, Dewil M, Dierick I, Jacobs A, De Vriendt E, Guergueltcheva V, et al. Disrupted function and axonal distribution of mutant tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase in dominant intermediate Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy. Nat Genet. 2006;38:197–202. doi: 10.1038/ng1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latour P, Thauvin-Robinet C, Baudelet-Mery C, Soichot P, Cusin V, Faivre L, Locatelli MC, Mayencon M, Sarcey A, Broussolle E, et al. A major determinant for binding and aminoacylation of tRNA(Ala) in cytoplasmic Alanyl-tRNA synthetase is mutated in dominant axonal charcot-marie-tooth disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Beebe K, Nangle LA, Jang J, Longo-Guess CM, Cook SA, Davisson MT, Sundberg JP, Schimmel P, Ackerman SL. Editing-defective tRNA synthetase causes protein misfolding and neurodegeneration. Nature. 2006;443:50–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YC, Lin KP, Soong BW. The mutational spectrum of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type II in Chinese Population on Taiwan. Neurology. 2011;76:A220. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin HM, Sakaguchi R, Liu C, Igarashi T, Pehlivan D, Chu K, Iyer R, Cruz P, Cherukuri PF, Hansen NF, et al. Compound heterozygosity for loss-of-function lysyl-tRNA synthetase mutations in a patient with peripheral neuropathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:560–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossessova E, Lima CD. Ulp1-SUMO crystal structure and genetic analysis reveal conserved interactions and a regulatory element essential for cell growth in yeast. Mol Cell. 2000;5:865–76. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80326-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami H, Ohta A, Ashigai H, Suga H. A highly flexible tRNA acylation method for non-natural polypeptide synthesis. Nat Methods. 2006;3:357–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami T, Garcia CA, Reiter LT, Lupski JR. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and related inherited neuropathies. Medicine (Baltimore) 1996;75:233–50. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199609000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy BC, Scriver CR, Singh SM. CpG methylation accounts for a recurrent mutation (c.1222C>T) in the human PAH gene. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:975. doi: 10.1002/humu.9447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nangle LA, Zhang W, Xie W, Yang XL, Schimmel P. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease-associated mutant tRNA synthetases linked to altered dimer interface and neurite distribution defect. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11239–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705055104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson G, Myers S. Intermediate forms of Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy: a review. Neuromolecular Med. 2006;8:123–30. doi: 10.1385/nmm:8:1-2:123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paratcha G, Ledda F, Baars L, Coulpier M, Besset V, Anders J, Scott R, Ibanez CF. Released GFRalpha1 potentiates downstream signaling, neuronal survival, and differentiation via a novel mechanism of recruitment of c-Ret to lipid rafts. Neuron. 2001;29:171–84. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribas de Pouplana L, Buechter D, Sardesai NY, Schimmel P. Functional analysis of peptide motif for RNA microhelix binding suggests new family of RNA-binding domains. EMBO J. 1998;17:5449–57. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice P, Longden I, Bleasby A. EMBOSS: the European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet. 2000;16:276–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar-Grueso EF, Kim S, Kim H. Embryonic mouse spinal cord motor neuron hybrid cells. Neuroreport. 1991;2:505–8. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199109000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selker EU, Stevens JN. DNA methylation at asymmetric sites is associated with numerous transition mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:8114–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.8114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shitivelband S, Hou YM. Breaking the stereo barrier of amino acid attachment to tRNA by a single nucleotide. J Mol Biol. 2005;348:513–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skre H. Genetic and clinical aspects of Charcot-Marie-Tooth’s disease. Clin Genet. 1974;6:98–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1974.tb00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storkebaum E, Leitao-Goncalves R, Godenschwege T, Nangle L, Mejia M, Bosmans I, Ooms T, Jacobs A, Van Dijck P, Yang XL, et al. Dominant mutations in the tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase gene recapitulate in Drosophila features of human Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11782–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905339106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan M, Lee SS, Zhang X, Houwink-Manville I, Song HR, Amir RE, Budden S, Naidu S, Pereira JL, Lo IF, et al. Rett syndrome and beyond: recurrent spontaneous and familial MECP2 mutations at CpG hotspots. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:1520–9. doi: 10.1086/302690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W, Nangle LA, Zhang W, Schimmel P, Yang XL. Long-range structural effects of a Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease-causing mutation in human glycyl-tRNA synthetase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:9976–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703908104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.