Abstract

Synapse formation is driven by precisely orchestrated intercellular communication between the presynaptic and the postsynaptic cell, involving a cascade of anterograde and retrograde signals. At the neuromuscular junction (NMJ), both neuron and muscle secrete signals into the heavily glycosylated synaptic cleft matrix sandwiched between the two synapsing cells. These signals must necessarily traverse and interact with the extracellular environment, for the ligand-receptor interactions mediating communication to occur. This complex synaptomatrix, rich in glycoproteins and proteoglycans, comprises heterogeneous, compartmentalized domains where specialized glycans modulate trans-synaptic signaling during synaptogenesis and subsequent synapse modulation. The general importance of glycans during development, homeostasis and disease is well established, but this important molecular class has received less study in the nervous system. Glycan modifications are now understood to play functional and modulatory roles as ligands and co-receptors in numerous model systems; however roles in synapse formation and modulation are less well understood. We highlight here properties of synaptomatrix glycans and glycan-interacting proteins with key roles in synaptogenesis, with a particular focus on recent advances made in the Drosophila NMJ genetic system. We discuss open questions and interesting new findings driving the current investigations of the complex, diverse and largely understudied glycan mechanisms. Keywords: Extracellular Matrix, Glycan, Synaptic Cleft, Neuromuscular Junction, Drosophila

INTRODUCTION

Electrically excitable cells (neurons and muscles) are precisely connected via chemical synapses to form functional networks. Study of the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) synapse between motor neuron and muscle cell has been instrumental in elucidating molecular mechanisms that drive synaptogenesis, both in vertebrate and invertebrate models (Sanes and Lichtman, 2001; Marques, 2005; Kummer et al., 2006; Collins and DiAntonio, 2007; Korkut and Budnik, 2009). Secreted glycoproteins (GPs) and proteoglycans (PGs) are instrumental in directing the organization of apposing presynaptic and postsynaptic cell surfaces. These bidirectional signals must traverse the synaptic cleft and/or adjacent perisynaptic domains. These highly compartmentalized extracellular environments harbor heavily glycosylated extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, glycosylated transmembrane receptors and outer-leaflet glycolipids which together form the synaptomatrix (Dityatev et al., 2010; Vautrin, 2010). All of these components interact with glycosylated trans-synaptic signals to induce and mediate synaptic development, homeostasis, plasticity and disease (Akins and Biederer, 2006; Margeta and Shen, 2010; Shen and Cowan, 2010; Wu et al., 2010). Recent studies have begun to reveal the importance of glycans in enabling and directing intercellular signaling in a wide variety of cellular contexts (Hynes, 2009; Dityatev et al., 2010).

To date, the function of glycosylated ECM components has primarily been studied in non-neuronal cells (Kalluri, 2003; Nelson and Bissell, 2006; Hynes, 2009; Sorokin, 2010), however their function is increasingly being appreciated at vertebrate and invertebrate synapses (Dityatev et al., 2010; Dityatev et al., 2010). We know that the synaptomatrix is rich in glycan modifications (Vautrin, 2010), but are only now beginning to understand the function of glycans during synaptogenesis and synaptic modulation. Glycan modifications such as glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) have well established roles in differentiation, tissue morphogenesis and organogenesis (Kramer, 2010). Genetic studies in mice, Drosophila and C. elegans have also revealed developmental requirements for numerous specific monosaccharide and polysaccharide sugar modifications including O-fucose, O-mannose, mucin-type O-glycans and N-glycans (Haltiwanger and Lowe, 2004). A true testament to the importance of glycans arises from the growing list of human diseases attributed to mutations in glycan biosynthetic genes (Jaeken and Matthijs, 2007; Schachter and Freeze, 2009), homologs of which are actively being studied in genetic model organisms (Altmann et al., 2001; Hewitt, 2009). For example, N-glycan biosynthesis defects induce disease states collectively categorized as congenital diseases of glycosylation (CDGs), with common disorders such as metabolic syndrome and autoimmunity also tied to this glycan class (Dennis et al., 2009). Similarly, O-linked glycosylation defects give rise to numerous diseases that include the muscular dystrophy class of neuromuscular disorders (Wopereis et al., 2006; Nakamura et al., 2010). Mechanistically, these glycan modifications feature prominently in intercellular signaling, with cell surface organization and receptor clustering dependent on specific glycans recognized and organized by glycan-binding lectin proteins (Martin, 2002; Yamaguchi, 2002; Kleene and Schachner, 2004; Patnaik et al., 2006). These precedents warrant scrutiny of these molecules during the physiological processes of synaptogenesis and synaptic modulation, as well as in synaptic disease states, which are all highly dependent on intercellular signaling.

One way forward is use of the genetically-tractable Drosophila NMJ model system, which has reduced genome redundancy for the inherently complex glycan modification pathways (Hagen et al., 2009). Mammalian glycan modifications including hybrid and sialylated N-glycans are found in Drosophila, albeit at low concentrations with the majority of modifications being high- or paucimannosidic glycans (Koles et al., 2007). Further, Drosophila and mammalian orthologs of the glycan biosynthetic galactosaminyltransferases enzymes show similar substrate preferences and share preferred sites of O-linked N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) sugar modifications on target proteins (Ten Hagen et al., 2003). Unbiased forward genetic Drosophila screens have already contributed to understanding of heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG) biosynthetic pathways, which have subsequently been shown to be important for cell-signaling, morphogenesis, metabolism and tissue repair in mammals (Bishop et al., 2007). Based on the confidence of conserved glycan pathways, investigation using the Drosophila NMJ is now poised to make significant contributions to the systematic study of glycan functions involved in synapse formation and modulation. The aim of this review article is to highlight synaptomatrix glycans, glycan-interacting proteins, glycosylated ligands and their receptors, and to focus on their recently discovered roles in synapse assembly at the Drosophila NMJ. Such studies should be of interest not only to synapse biologists, but also to other types of neuroscientists and developmental biologists, as insights derived from glycan roles in synaptogenesis are likely to be directly relevant to other arenas of intercellular communication in the nervous system as well as global development.

THE GLYCOSYLATED SYNAPTOMATRIX AT THE NEUROMUSCULAR JUNCTION

Architecture of the NMJ synaptomatrix

At the vertebrate NMJ, the primary (1°) synaptic cleft is the space between the motor neuron and the muscle that is continuous with secondary (2°) synaptic clefts formed by muscle cell membrane invaginations that lie apposed to the innervating motor neuron (Patton, 2003). The Drosophila NMJ clefts have a similar architecture, however the postsynaptic muscle folds form the sub-synaptic reticulum (SSR) that opens into the synaptic junctional cleft adjacent to presynaptic active zones (AZ) (Prokop, 2006). The vertebrate cholinergic NMJ 1° cleft is 40–50nm wide and contains a clearly-defined synaptic basal lamina that also occupies the 2° clefts and is continuous with the ensheathing muscle lamina (Patton, 2003). In comparison, the Drosophila glutamatergic NMJ 1° cleft is only 15–20 nm wide, and in place of a synaptic lamina there is an electron-dense specialization found only between the apposing presynaptic AZ and postsynaptic density (Prokop, 2006). In cross-section, this synaptic cleft domain contains periodic densities, and in freeze-fracture displays a highly-ordered honeycomb pattern (Prokop, 1999). At the vertebrate NMJ, the synaptic basal lamina provides mechanical support, harbors signaling factors and serves as a substratum during synaptogenesis (Patton, 2003). At the Drosophila NMJ, loss of the cleft synaptomatrix causes catastrophic failure of postsynaptic assembly and a near complete silencing of functional synapses during embryonic synaptogenesis (Rohrbough et al., 2007).

Synaptomatrix contains glycosylated ECM protein isoforms

Long-term evidence of glycosylation at the vertebrate NMJ comes from studies using fluorescently-conjugated lectins (Ribera et al., 1987; Scott et al., 1988; Crnefinderle and Sketelj, 1993), which bind specific carbohydrates, and to a lesser extent, anti-carbohydrate monoclonal antibodies that detect, for example, β-linked GalNAc (Martin et al., 1999) and cytotoxic T cell (CT) carbohydrate antigens (Lefrancois and Bevan, 1985). Both approaches reveal restriction of synaptic carbohydrate modifications to different presynaptic (e.g. CT1) and postsynaptic (e.g. CT2) compartments, suggesting localized requirements for specific glycan modifications (Martin et al., 1999). Likewise, anti–heparan sulfate antibodies that recognize HSPG GAG modifications show clearly distinguishable synaptic and extrasynaptic (on the muscle away from the synapse) glycans (Jenniskens et al., 2000). Plant and fungal lectins has been especially useful for revealing localized sugar modifications at the vertebrate NMJ. For example, Wheat Germ Agglutinin (WGA), Soy bean agglutinin (SBA), Concanavilin A (ConA), Griffonia simplicifolia 1 isolectin B-4 (GS-1), Limax flavus agglutinin (LFA), Peanut agglutinin (PNA) and Dolichos biflorus agglutinin (DBA) lectins all show strong labeling of NMJ synaptic regions compared to low labeling of extrasynaptic regions (Iglesias et al., 1992). In addition to highlighting spatially localized glycan modifications, these studies provide insight into specialization of the ECM associated with the NMJ (Lis and Sharon, 1986; Iglesias et al., 1992).

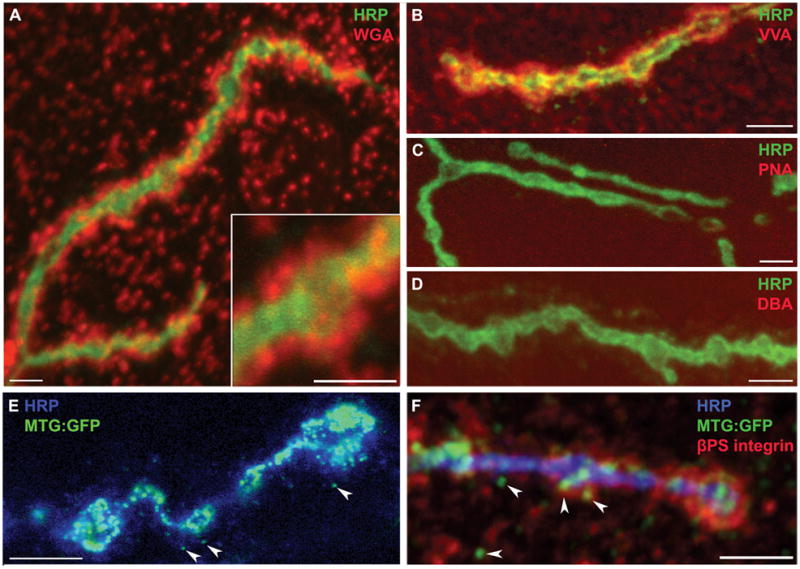

Similar localized carbohydrate distribution is also seen in Drosophila. Studies show that embryonic neuronal somata bind ConA and Limulus polyphemus agglutinin (LPA); central and peripheral neuronal processes bind WGA, PNA, Ulex Europeus agglutinin 1 (UEA-1) and Bauhina purpura agglutinin (BPA) lectins; and SBA labeling is completely excluded from the nervous system (Fredieu and Mahowald, 1994; Damico and Jacobs, 1995). At the Drosophila NMJ, WGA and Vicia villosa agglutinin (VVA) lectins show clearly enriched synaptic labeling (Fig. 1) (Haines et al., 2007; Rushton et al., 2009). WGA labels clearly defined extracellular punctae that are widely distributed over the muscle surface, but much more intense, densely-spaced and organized immediately adjacent to presynaptic boutons (Fig. 1A). These WGA domains clearly indicate that the extracellular space is compartmentalized into glycan-specialized regions. VVA labeling is almost wholly restricted to the NMJ, with little or no labeling in extrasynaptic domains (Fig. 1B). In clear contrast to WGA, VVA labels a more contiguous synaptomatrix domain closely associated with NMJ boutons. Importantly, the NMJ synaptomatrix is defined as much by the absence of carbohydrates as their presence. PNA (Fig. 1C) and DBA (Fig. 1D) lectins clearly and intensely label non-synaptic areas but are effectively excluded from the NMJ. This is in contrast to vertebrate NMJ lectin labeling, where DBA exclusively stains rat synaptic domains (Iglesias et al., 1992), indicating some species-specific differences. DBA recognizes trisaccharide-linked GalNAc, and does label other Drosophila neuronal tissues such as the omatidia in the developing eye (Yano et al., 2009). The lack of DBA staining at the Drosophila NMJ indicates the presence of a regulated and controlled synaptic environment that expresses specific arrangement of sugars. These studies indicate conservation of glycan modifications, as well as the fact that differences exist in glycan expression between vertebrate and invertebrate NMJs.

Figure 1. Glycan and glycan-interacting lectin expression domains at the Drosophila NMJ.

The Drosophila wandering third instar NMJ probed with a range of lectins and antibodies in detergent-free conditions to maintain synaptomatrix integrity. A) NMJ probed with WGA lectin (red) and anti-HRP (green), which recognizes glycans associated exclusively with the presynaptic neuronal membrane. The inset shows WGA domains in the synaptomatrix surrounding a single NMJ bouton. B) VVA lectin (red) and HRP (green). The VVA labeling occupies a different domain than WGA labeling, and is very highly enriched in the NMJ synaptomatrix. C) PNA lectin (red); HRP (green). D) DBA lectin (red); HRP (green). Note that both PNA and DBA lectins do not detectably label the NMJ synaptomatrix, although strong labeling is present in adjacent tissues (not shown). E) The MTG:GFP fusion protein (green) co-labeled with anti-HRP (blue). The MTG lectin localizes to synaptomatrix punctae (arrows) surround NMJ synaptic boutons. F) Triple labeling of MTG:GFP (green), βPS integrins (red) and HRP (blue). Note the three overlapping domains in the synaptomatrix. Scale bars = 5 μm.

Besides charting the NMJ glycan landscape, lectins have been used to determine direct glycan modifications on synaptic proteins. In vitro studies show that purified synaptic laminin (s-laminin) binds WGA, ConA, Maackia amurensis agglutinin (MAA), Ricinus communis agglutinin (RCA120), Datura stramonium agglutinin (DSA) and Aleuria aurantia agglutinin (AAA) lectins, without binding PNA (Chiu et al., 1992). These findings illustrate the specific but heterogeneous nature of glycan modifications present on just a single synaptomatrix molecule required for NMJ development (Table 1A) (Maselli et al., 2009). Lectin staining also has helped to visualize sugar modifications on dystroglycan, an ECM receptor found both at vertebrate and Drosophila NMJs; VVA lectin co-localizes with dystroglycan staining (Haines et al., 2007). More recently, lectins such as Galanthus rivalis agglutinin (GNA), Nicotiana tabacum (Nictaba) and Rhizoctoni solani agglutinin (RSA) have been utilized in lectin-affinity chromatography coupled to Mass spectrophotometric analysis to elucidate N- and O- linked glycosylation of large number of Drosophila synaptomatrix components such as laminin B2, Laminin A, terribly reduced optic lobes (homolog of vertebrate perlecan) and the HSPG division abnormally delayed (dally) (Vandenborre et al., 2010). Lectins are a powerful tool for glycan investigation with enormous scope for increased use in future Drosophila NMJ studies.

Table I. NMJ synaptomatrix components.

A) The vertebrate NMJ. The table summarizes only the major symptomatic components discussed in this review B) The Drosophila NMJ. Synaptomatrix components are listed in the same order as for the vertebrate NMJ; including ECM, ECM receptors and secreted trans-synaptic signals

| A. Vertebrate NMJ | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycomatrix component | Functions | Sample References | |

| ECM | Laminins | ||

| β2 | presynaptic active zone formation, synaptic vesicle organization, postsynaptic fold formation, NMJ α (7B) integrin expression, clustering of voltage gated Ca2+ channels | (Noakes et al., 1995; Nishimune et al., 2004) | |

| α2 | postsynaptic fold formation, NMJ α (7A) integrin receptor expression | (Martin et al., 1996) | |

| α4 | apposition of presynaptic active zones and postsynaptic junctional folds | (Patton et al., 2001) | |

| Collagen | |||

| α2(IV), α3(IV), α6(IV) | synaptic vesicle clustering, prevention of excessive neural outgrowth | (Fox et al., 2007) | |

| Col XIII | neuron and muscle apposition, active zone formation, postsynaptic AChR clustering | (Latvanlehto et al., 2010) | |

| ECM Receptors | Dystroglycan | postsynaptic clustering and anchoring of AChRs, cytoskeletal link to ECM | (Bewick et al., 1996) |

| Integrins | |||

| α7 | postsynaptic AChR clustering | (Burkin et al., 2000) | |

| β1 | postsynaptic AChR clustering; directing presynaptic axon growth and arborization | (Schwander et al., 2004) | |

| Secreted signals | Agrin | postsynaptic AChR clustering | (Sanes and Lichtman, 2001) |

| Perlecan | localization of acetylcholinesterase | (Peng et al., 1998; Arikawa-Hirasawa et al., 2002) | |

| s-entactin | maintenance of NMJ morphology | (Fox et al., 2008) | |

| WNT (3a) | postsynaptic AChR clustering | (Henriquez et al., 2008) | |

| TGF-β2 | amplification of postsynaptic spontaneous transmission, decrease in number of presynaptic vesicles used per stimulation | (Fong et al., 2010) | |

| acetylcholine | neurotransmission, negative regulator of postsynaptic AChR clustering | (Misgeld et al., 2002) (Brandon et al., 2003) | |

| B. Drosophila NMJ | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycomatrix component | Functions | Sample References | |

| ECM | Laminin A | formation of appropriate contact area between neuron and muscle | (Prokop et al., 1998) |

| ECM Receptors | Dystroglycan | regulation of postsynaptic GluR subunit composition, decrease in presynaptic release of glutamate neurotransmitter, postsynaptic protein assembly | (Bogdanik et al., 2008) |

| Integrins | |||

| βPS | synaptic bouton formation, NMJ synapse specification, localization of postsynaptic proteins, postsynaptic assembly | (Beumer et al., 1999; Beumer et al., 2002) | |

| αPS1, αPS2 | formation of appropriate contact sites between nerve and muscle | (Prokop et al., 1998) | |

| αPS3 | NMJ synapse specification, synaptic bouton formation, regulation of neurotransmission strength and activity-dependent modulation | (Prokop et al., 1998; Rohrbough et al., 2000) | |

| Fasciclins | |||

| Fas I | presynaptic arborization control, neurotransmission strength | (Zhong and Shanley, 1995) | |

| Fas II | synaptic patterning, specificity, growth, stabilization, presynaptic functional plasticity | (Davis et al., 1996; Schuster et al., 1996) | |

| Fas III | homophilic synaptic target recognition | (Kose et al., 1997) | |

| Syndecan | presynaptic terminal growth regulation | (Johnson et al., 2006) | |

| Dally-like protein (dlp) | presynaptic active zone morphology, synaptic transmission strength | (Johnson et al., 2006) | |

| Secreted signals | Mind-the-Gap (Mtg) | organization of synaptic cleft matrix, postsynaptic GluR localization, integrin localization, Jeb/Alk signaling regulation | (Rohrbough et al., 2007; Rushton et al., 2009; Rohrbough, 2010) |

| Jelly-belly (Jeb) | regulation of cell adhesion proteins, BMP signaling pathway interaction | (Englund et al., 2003; Rohrbough, 2010) | |

| Wingless (Wg) | presynaptic active zone formation, postsynaptic GluR distribution, activity dependent synaptic bouton formation, regulation of spontaneous release function | (Packard et al., 2002; Mathew et al., 2005; Ataman et al., 2008; Korkut et al., 2009) | |

| Glass Bottom Boat(Gbb) | localization of presynaptic active zones, regulation of cell adhesion molecules, regulation of spontaneous release function and neurotransmission strength | (Aberle et al., 2002; Haghighi et al., 2003; McCabe et al., 2003; Nahm et al., 2010) | |

| Glutamate | neurotransmission, negative regulator of postsynaptic GluR clustering | (Jan and Jan, 1976; Featherstone et al., 2000; Featherstone et al., 2002; Augustin et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2009) | |

In addition to the above mentioned glycan distributions, the specialization of NMJ synaptomatrix stems from the presence of specific isoforms of otherwise ubiquitous ECM glycoproteins and proteoglycans, including laminin, collagen (IV) and perlecan (Marshall et al., 1977). At the vertebrate NMJ, global basal lamina glycoproteins such as lamininα2/γ1, entactin, fibronectin and perlecan are present, along with synaptically-specialized isoforms such as laminin α4/α5/β2, collagen α3(IV)/α4(IV)/α5(IV), neuregulin α2, synaptic entactin (s-entactin), perlecan and agrin (Table 1A). Synaptic cleft specific proteins like laminin α4, β2 and α5 are N-glycosylated, and recently proteomic studies have established two galactosyltransferases involved in core glycosylation of s-collagen (Chen et al., 2009; Schegg et al., 2009; Tian et al., 2009). GalNAc sugar modification found exclusively in synaptic basal lamina further indicate the importance of glycosylation of NMJ synaptomatrix proteins (Hall and Sanes, 1993; Patton, 2003). In contrast, the molecular composition of the cleft material in the Drosophila NMJ is only very poorly characterized (Table 1B). Indirect evidence for vertebrate-like NMJ specialization comes from the a large number of orthologous proteins to laminin B2 (Montell and Goodman, 1989), collagen IV (Borchiellini et al., 1996), dystroglycan (Bogdanik et al., 2008) and perlecan (Voigt et al., 2002) which have been identified at the Drosophila NMJ. However, clear roles in Drosophila synaptogenesis have only been tested for few molecules such as laminin A (Prokop et al., 1998); mutations in which cause a decrease in the extent of interaction between the motor neuron and muscle (Table 1B). Clearly, there is enormous scope for further studies using the Drosophila genetic model.

Synaptomatrix bounding cell membranes bear glycosylated proteins

In addition to secreted ECM protein glycosylation, most of the transmembrane proteins involved in cell adhesion and signaling during synaptogenesis carry distinctive carbohydrate modifications. For example, Drosophila cell adhesion molecules (CAMs), such as fasciclins I–III (e.g. fasII homologue of vertebrate neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM)) and neuroglian (homologue of vertebrate L1), are developmentally-regulated glycoproteins involved in homophilic recognition, adhesion and maintenance functions during synaptogenesis (Table 1B) (Bastiani et al., 1987; Patel et al., 1987; Harrelson and Goodman, 1988; Bieber et al., 1989; Elkins et al., 1990; Halpern et al., 1991). NCAM and L1 are decorated with specific L2/HNK-1 carbohydrate moieties (Kruse et al., 1984), and their Drosophila homologs are similarly modified and recognized by an antibody against the horse radish peroxidase (HRP) epitope, a fucosylated N-glycan (Fig. 1) (Jan and Jan, 1982). Interestingly, fasciclins expressed outside developing neural tissue are not bound by HRP antibodies, indicating these are neural-specific glycosylation pathways (Snow et al., 1987). NCAM is also modified by polysialic acid (PSA) addition, which inhibits cell adhesive activities (Sadoul et al., 1983). Indeed, sialic acid modifications are particularly important in modulating the activities of membrane proteins involved in vertebrate intercellular signaling (Rutishauser, 2008), and similarly during Drosophila development (Roth et al., 1992). In vertebrate synapses, sialylated glycans are present in the synaptic cleft extracellular space, where they are involved in cell adhesion and intercellular communication (Varki and Varki, 2007; Rutishauser, 2008; Muhlenhoff et al., 2009), although the function of synaptic sialylation remains poorly characterized.

Conserved Drosophila sialylation biosynthetic pathways include sialic acid phosphate synthetase (Kim et al., 2002), CMP-sialic acid synthetase (Viswanathan et al., 2006) and Drosophila sialyltransferase (DSiaT) with homology to mammalian ST6Gal sialyltransferases (Koles et al., 2004). At the Drosophila NMJ, DSiaT plays pivotal roles in synaptogenesis that affects the development of locomotory behavior (Repnikova et al., 2010). One aspect of this requirement is that DSiaT modulates voltage-gated sodium channels. In vertebrates, similar regulation involves negative charge due to polysialylation, but in Drosophila the mechanism appears dependent on monosialylation (Koles et al., 2004). Sialic acid modifications also modulate synaptogenesis independently through regulation of CAM homophilic interactions. For example, addition of polysialic acid to NCAM attenuates adhesion and also interferes with other CAMs, such as L1 (Rutishauser et al., 1988). Recently, a screen for synaptic mutants in Drosophila uncovered fuseless (fusl), the putative homologue of the mammalian Sialin 8-pass transmembrane sialic acid transporter (Long et al., 2008). In vertebrates, the monosaccharide sialic acid cleaved from sialoglycoconjugates is exported across membranes by the Sialin transporter (Morin et al., 2004) (Wreden et al., 2005), and two inherited cognitive dysfunction disease occur in humans when the sialin gene is mutant (Verheijen et al., 1999). At the Drosophila NMJ, fusl mutants display >75% reduction in evoked synaptic transmission due to a presynaptic requirement in localizing Cacophony Ca2+ channels (Kawasaki et al., 2000; Xing et al., 2005). The homologous vertebrate Ca2+ channel (α-1 subunit) binds ECM laminins, to facilitate organization of presynaptic active zones (Table 1A) (Nishimune et al., 2004). At the Drosophila NMJ, the Bruchpilot protein stabilizes active zone formation by integrating Cacophony Ca2+ channels with intracellular components and, just like fusl mutants (Long et al., 2008), bruchpilot mutants show reduced Ca2+ channel clustering and impaired vesicular release (Kittel et al., 2006; Wagh et al., 2006). Since sialic acid modifications are typically added as the terminal residue of cell surface oligosaccharides, one attractive model is that such a carbohydrate addition to the extracellular domain of the presynaptic Ca2+ channel provides a critical link to the synaptic cleft ECM, driving active zone assembly during synaptogenesis.

Another important synaptomatrix component that is required to tether the muscle to the ECM is dystroglycan (Dg), which forms a complex called the dystrophin associated glycoprotein complex (DGC) (Pilgram et al., 2010). In addition to binding the intracellular cytoskeleton, the α-dystroglycan of the DGC binds multiple extracellular synaptomatrix components such as secreted agrin (Sugiyama et al., 1994) and perlecan (Talts et al., 1999), and transmembrane neurexin (Sugita et al., 2001). At the Drosophila NMJ, Dystroglycan reportedly facilitates the organization of glutamate receptor (GluR) clusters in the postsynaptic domain (Table 1B) (Bogdanik et al., 2008). In vertebrates, mutations in at least three glycan biosynthetic genes (POMT1 (de Bernabe et al., 2002), POMT2 (van Reeuwijk et al., 2005) and POMGnT1 (Yoshida et al., 2001)), produce hypoglycosylation of α-dystroglycan. When dysfunctional, these glycosyltransferases give rise to a range of diseases termed dystroglycanopathies, which include congenital muscular dystrophies (CGDs) and limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMD) (Martin, 2007). In vertebrates, the dystroglycan molecule serine/threonine residues are modified by Neu5Ac(α2–3)Gal(β1–4)GlcNAc(β1–2)Man(α1-O-S/T) and a core 1 O-linked structure Gal(β1–3)GalNAc(α1-O-S/T) (Endo, 1999). Other sugar modifications include CT carbohydrate antigen (Hoyte et al., 2002), HNK-1 antigen (Smalheiser and Kim, 1995) and Lewis-X antigen (Martin, 2003). At the Drosophila NMJ, mutation of the two mannosyltransferase enzymes that target dystroglycan for glycosylation (tw (POMT1) and rt (POMT2) (Nakamura et al., 2010)) recapitulate the synaptic phenotypes of reduced Dg function (Table 1B) (Haines and Stewart, 2007; Shcherbata et al., 2007; Wairkar et al., 2008). These studies highlight the utility of the Drosophila NMJ model for further study of the glycobiology at the synapse, and as a model system for human neuromuscular diseases arising from defects in glycan biosynthesis.

GLYCOSYLATED SYNAPTOMATRIX INTERACTION WITH TRANS-SYNAPTIC SIGNALS

The most obvious signal that must transverse the glycosylated synaptomatrix is the neurotransmitter itself: acetylcholine (ACh) at the vertebrate NMJ and glutamate at the Drosophila NMJ. It was first shown in Drosophila that neurotransmitter release from the presynaptic terminal suppresses the surface presentation and postsynaptic clustering of neurotransmitter receptors, indicating that the neurotransmitter inhibits its own receptor during synapse formation and modulation (Featherstone et al., 2000; Featherstone et al., 2002; Augustin et al., 2007). Similar to this glutamate activity at the Drosophila NMJ, ACh at the vertebrate NMJ has the exact same effect, acting as a negative regulator of acetylcholine receptor (AChR) surface maintenance and clustering (Misgeld et al., 2002; Brandon et al., 2003). Recent evidence suggests that glycans like polysialic acid can interact directly with such neurotransmitters, indicating a putative modulatory role for these glycans with this classical trans-synaptic signaling (Sato et al., 2010). At the vertebrate NMJ, negative ACh function is counteracted by the action of the secreted signal agrin (Bezakova and Ruegg, 2003; Misgeld et al., 2005), a key player in synaptogensis and the founding example of secreted trans-synaptic signaling ligands.

HSPG trans-synaptic signaling

The HSPG Agrin is 50% sugar by weight due to glycan modifications that include heparan sulfate chains (Tsen et al., 1995), O-linked glycans (Parkhomovskiy et al., 2000) and N-linked glycans (Rupp et al., 1991). Agrin induces phosphorylation of the muscle-specific kinase (MuSK) receptor that can be inhibited by Gal(β1,4)GlcNAc and Gal(β1,3)GalNAc (Parkhomovskiy et al., 2000). MuSK also binds Gal(β1,4)GlcNAc, which suggests that this glycan modification is required for agrin mediated synaptogenic function (Table 1A) (Parkhomovskiy et al., 2000). Other glycans such as heparin, heparan sulfate and sialic acid show inhibitory effects that perturb agrin-mediated AChR clustering (Wallace, 1990; Grow and Gordon, 2000). Treatment with enzymes that cleave sugars, such as neuraminidase (exposes glycans Gal(β1,4)GlcNAc or Gal(β1,3)GalNAc) (Martin and Sanes, 1995) or α-galactosidase (removes α-galactose sugars to expose lactosamines or N-acetyllactosamines) (Parkhomovskiy and Martin, 2000), causes agrin-independent MuSK activation and AChR clustering (Grow et al., 1999). Besides regulation of synaptogenesis and associated signal transduction, other glycans attached to synaptomatrix components such as laminin-1 and -2 can bind to agrin by both heparan-sulfate (glycan)-dependent and -independent mechanisms (Table 1A) (Hall et al., 1997). Further, agrin not only presents glycan chains, but also binds to carbohydrates of other glycoconjugates through its lectin domain, extending its capacity to form an inter-connected compartmentalized meshwork at the synapse (Kleene and Schachner, 2004).

Agrin is not identifiable in the Drosophila genome. However, other secreted HSPGs such as syndecan, as well as the GPI-anchored HSPG dally-like protein (dlp), have been identified at the Drosophila NMJ (Table 1B) (Johnson et al., 2006; Ren et al., 2009) where they mediate axon guidance and synapse formation (Yamaguchi, 2001; Lee and Chien, 2004; Holt and Dickson, 2005; Van Vactor et al., 2006). The basic structure shared by HSPGs is a protein core to which heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan (HS) chains are attached (Bernfield et al., 1999). GAG chains are attached to serine/threonine residues on proteins via a linker (GlcA-Gal-Gal-Xyl) by alternate addition of glucuronic acid (GlcA) and N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) via 1,4- linkages (Lind et al., 1993). HS saccharides are further modified by addition of sulfate groups to diversify GAG chains to direct HSPG functions. These modifications are catalyzed by N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase (Ndst), which replaces the N-acetyl group of GlcNAc with a sulfate group (Aikawa and Esko, 1999), and then by substrate-specific iduronosyl 2-O-sulfotransferase (hs2st), glucosaminyl 6-O-sulfotransferase (hs6st) and glucosaminyl 3-O-sulfotransferase (hs3st) (Rosenberg et al., 1997; Habuchi et al., 2000). Along the GAG chains, sulfate modifications can be concentrated into highly sulfated domains (S domains) of 6–10 disaccharides that resemble heparin (Maccarana et al., 1996). Only 10% of the disaccharide units are S domains, indicating a possible spatial encoding of information by the sulfate positions on the HS (Nakato and Kimata, 2002). Once added, the sulfate groups can be cleaved by sulfatases (e.g. sulf1), which selectively removes sulfates attached to particular disaccharide units (Lamanna et al., 2007). The resultant GAG sulfation profiles dictate HSPG co-receptor functions that modulate ligand-receptor interactions (Dreyfuss et al., 2009). For example, FGF-ligand dimerization occurs on characteristically sulfated HS sequences of 10–14 sugars (Walker et al., 1994), and interaction of the dimerized ligand with its FGFR receptor is dependent on sulfated HS (Springer et al., 1994). Structural studies confirm HS GAG mediated stabilization in a 2:2 tetrameric assembly between the FGF1 and FGFR2 dimers associated with HS chains (Schlessinger et al., 2000). The role of such modifications in directing HSPG functions during synaptic development and modulation is a critical area for future investigation.

WNT-Wingless signaling

Large numbers of morphogens that are required during many phases of development are also found to play important roles at synapses, including the WNTs (Hall et al., 2000; Packard et al., 2002; Salinas, 2005; Henriquez et al., 2008), fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) (Umemori et al., 2004), and transforming growth factor/bone morphogenic proteins (TGF-β/BMPs) (Packard et al., 2003; Salinas, 2003). Glycan modifications share an intimate relationship with such classical morphogens, and there is great potential for HS modifications regulating trans-synaptic signaling. Drosophila forward genetic screens of WNT signaling pathways have identified genetic interactions with heparan sulfate (HS) biosynthetic enzymes (Hacker et al., 2005). For example, screens for mutants phenocopying the founding WNT wingless (Wg) mutant identified sugarless (sgl), a uridyl-diphosphate-6-glucose dehydrogenase (UDPG) that synthesizes glucuronic acid building blocks of HS chains, and tout-velu (ttv), a polymerase that extends these chains (Bellaiche et al., 1998). These findings indicate a link between HS sulfation and WNT-wingless signaling. At the Drosophila NMJ, trans-synaptic Wg plays an important role in synaptogenesis (Fig. 2), where it has recently been shown to mediate anterograde signaling via an unusual exosome delivery mechanism (Korkut et al., 2009). Phenotypes of loss-of-function mutations in this pathway include reduced number of synaptic boutons, disrupted organization of the postsynaptic scaffold protein Discs Large (DLG), a postsynaptic density 95 kDa (PSD-95) homolog, and glutamate receptor (GluR) mislocalization (Fig. 2) (Ataman et al., 2008). Likewise, WNT signaling in C. elegans regulates GluR-1 abundance in the ventral nerve cord (Juo and Kaplan, 2004). WNT signaling similarly operates at mammalian synapses, where Wnt7a enhances synapsin I clustering and branching in cultured granule cells and cerebellar synapses (Table 1A) (Lucas and Salinas, 1997). The cognate receptor for WNT-Wg is Frizzled 2 (Fz2), which is endocytosed upon ligand binding and then transported to the nuclear region where its cleaved C-terminal translocates into the nucleus to induce transcription (Fig. 2) (Mathew et al., 2005). WNT-Wg can also function as a retrograde signal by modulating futsch (Drosophila microtubule associated protein 1B, MAP1B) via inhibition of Shaggy (Drosophila homolog of GSK3β), hence affecting microtubule function modulating NMJ formation (Franco et al., 2004; Gogel et al., 2006; Franciscovich et al., 2008). WNT-Wg signaling also prevents ectopic synapse formation on non-target muscle cells hence directing appropriate synaptogenesis (Table 1B) (Inaki et al., 2007). The potential role of glycans in mediating such signaling stems from studies in Drosophila wing disc showing that WNT-Wg localization, as well as activation of the downstream signaling pathway, is dependent on the precise extent of HS sulfation (Reichsman et al., 1996). For example, sulf1 mutants that cannot cleave sulfate modifications show increased Wg expression along the dorso-ventral axis of the wing disc, supporting a role for sulfated HS GAG chains in regulating Wg signaling (Kleinschmit, 2010). By extension, HS GAGs at the Drosophila NMJ could bind Wg and other trans-synaptic signals, and present them as co-receptors to their transmembrane receptors to initiate downstream signaling processes driving synaptogenesis and subsequent synapse maturation (Fig. 2). In support of this hypothesis, quail sulfatase (Qsulf1) can positively influence the ability of WNT ligand to associate with its cognate receptor Frizzled (Dhoot et al., 2001; Ai et al., 2003). A high priority is to assay for similar glycan mechanisms regulating trans-synaptic signaling.

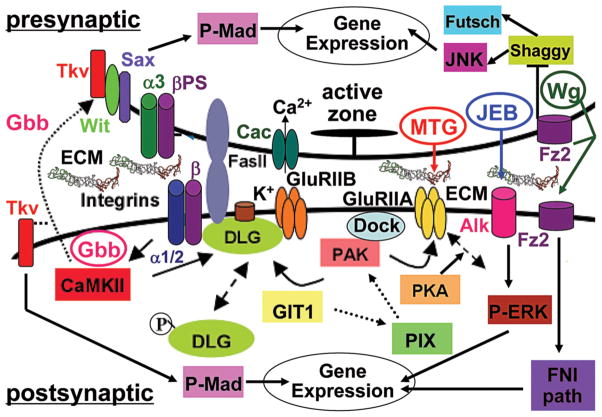

Figure 2. Diagram of trans-synaptic signaling pathways at the Drosophila NMJ.

Presynaptic: The active zone (AZ) is indicated by a T-bar. Cell membrane components include PS integrins (α3 and βPS subunits), homophilic CAM Fasciclin II (FasII) and cacophony calcium channels (Cac). Cytoplasmic proteins include kinases JNK and Shaggy, and the MAP1B Futsch. Postsynaptic: The glutamate receptor (GluR) domain includes two GluR classes (GluRIIA and B) and potassium channels (K+). Cell membrane components include PS integrins (α1/2 and βPS) and FasII. Membrane associated and cytoplasmic proteins include scaffolding proteins Discs large (DLG) and Dock, kinase PAK and regulators PIX and GIT1, and calmodulin kinase II (CamKII). Trans-synaptic pathways: Secreted signals Wingless (Wg), Glass bottom boat (Gbb) and Jelly belly (Jeb), and their respective membrane cognate receptors Frizzled 2 (Fz2), Thickveins (Tkv)/Wishful Thinking (Wit)/Saxophone (Sax) and Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (Alk). The Frizzled nuclear import pathway is indicated as FNI. The known downstream transcription factor for Gbb is Mothers against decapentaplegic (Mad; P-Mad indicating phosphorylated form), and for Jeb is ERK (P-ERK indicating phosphorylated form). Extracellular synaptomatrix components are indicated as ECM between the presynaptic neuron and postsynaptic muscle cells.

TGFβ/BMP signaling

TGFβ/BMP signaling is also modulated by heparan sulfate glycan modifications (Chen et al., 2006). In mammals, BMP proteins have roles in neural crest formation (Kishimoto et al., 1997; Dick et al., 2000; Nguyen et al., 2000) and migration (Graham et al., 1994; Shah et al., 1996; Marazzi et al., 1997; Sela-Donenfeld and Kalcheim, 2000), axon guidance (Augsburger et al., 1999; Butler and Dodd, 2003), neurite outgrowth and synaptogenesis (Meng et al., 2002; Endo et al., 2003). At the Drosophila NMJ, the retrograde BMP signal Glass Bottom Boat (Gbb) is similarly required for synapse stabilization (Fig. 2) (Eaton and Davis, 2005). Null gbb mutants, as well as mutations in its BMP receptors (type I receptors Thickveins (Tkv) and Saxophone (Sax), type II receptor Wishful thinking (Wit)) and BMP pathway regulators (e.g. the Cdc42 selective GAP Rich), produce gross synaptic defects that include distorted pre- and postsynaptic membranes, mislocalized presynaptic T-bars, reduced active zone number, and drastic decrease of synaptic transmission at the NMJ (Fig. 2) (Marques et al., 2002; McCabe et al., 2003; Rawson et al., 2003; McCabe et al., 2004; Nahm et al., 2010). As above, Sulf1 activity has an activating effect on BMP signaling, suggesting that HS modifications may have a role in this trans-synaptic signaling pathway as well. For example, Sulf1 regulates release of the BMP antagonist noggin, allowing BMP to interact with its cognate receptor (Viviano et al., 2004). It should be noted that glycan regulation of these signaling pathways are based mostly on in vitro data and are highly context specific; hence directly predicting stimulatory and/or inhibitor roles of glycan modifications at the synapse is not straightforward. In addition to binding, presenting and/or sequestering WNT-wingless and BMP molecules bound to HS, these signaling molecules can be released by the enzymatic activity of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (Kainulainen et al., 1998). Other glycosylated synaptic ECM components can similarly bind and present signaling factors. Thus, glycans in the synaptomatrix could potentially serve as a repository for trans-synaptic signaling molecules, and likely modulate known WNT and BMP signaling pathways by sequestering away or presenting signals to cognate receptors.

GLYCAN-BINDING LECTINS REGULATE TRANS-SYNAPTIC SIGNALING

Mind-the-gap: secreted lectin that organizes cell surface receptors

An exciting idea that has arisen in recent years is that endogenous animal lectins (glycan-binding proteins) play critical roles in development and intercellular signaling. At the Drosophila NMJ, a prime example is the GlcNAc-binding lectin encoded by mind-the-gap (mtg) (Rohrbough et al., 2007; Rushton et al., 2009; Rohrbough and Broadie, 2010). The MTG protein is secreted from the presynaptic terminal to reside within the synaptic cleft, and in perisynaptic extracellular domains, where it co-localizes with WGA (Fig. 1E, F) (Martin, 2003). Consistently, both proteins share binding affinity for GlcNAc sugar residues. Transgenic MTG-GFP is trafficked to synapses, where the secreted protein remains near the cell surface (Fig. 1E). Ultrastructural immunogold labeling shows secreted MTG adjacent to active zones in the presynaptic nerve cell, and in the extracellular lumen of the postsynaptic SSR (Rohrbough et al., 2007). During embryonic development, the dynamic mtg expression pattern correlates closely with key periods of NMJ synaptogenesis, with the expression peak coinciding with the presynaptic induction of postsynaptic GluR domain assembly (Broadie and Bate, 1993; Broadie and Bate, 1993; Broadie and Bate, 1993). Null mtg mutants exhibit severe abrogation of the glycosylated synaptomatrix between the presynaptic active zone and postsynaptic GluR domains, and greatly reduced GluR localization with a corresponding loss of GluR function (Table 1B) (Rohrbough et al., 2007). Moreover, all known postsynaptic signaling/scaffold proteins functioning upstream of GluR localization are grossly reduced or severely mislocalized in mtg mutants, including the dPix–dPak–Dock cascade (Parnas et al., 2001; Ang et al., 2003; Albin and Davis, 2004) and the Dlg/PSD-95 scaffold (Fig. 2) (Thomas et al., 2000; Ataman et al., 2006; Gorczyca et al., 2007). Neuronally-targeted mtg RNA-interference (RNAi) likewise reduces postsynaptic assembly, whereas postsynaptically-targeted RNAi has no effect (Rohrbough et al., 2007). Similarly, neuronally-targeted mtg in the null mutant rescues the postsynaptic assembly loss. These data conclusively indicate that presynaptic MTG is required for the induction of the postsynaptic pathways driving GluR domain formation; hence it serves as an anterograde trans-synaptic signal.

It was recently shown that direct loss of GlcNAc transferase alters Drosophila NMJ structure and function, as well as locomotory behavior (Haines and Stewart, 2007). This work independently demonstrates that GlcNAc-mediated interactions have key roles in synaptic maturation. Thus, together this recent work indicates that both the GlcNAc sugar itself and GlcNAc-binding lectins modulate synaptogenesis. Since GlcNAc is a repeating sugar unit of HS, it seems probable that MTG regulates localization of HS-carrying proteins and thereby any trans-synaptic signaling proteins bound to this lattice. With this mechanism, MTG could coordinately regulate multiple trans-synaptic pathways via binding GlcNAc moieties on both HSPGs and receptors such as integrins (Fig. 1F). The fact that null mtg mutants exhibit a gross reduction or complete absence of electron-dense synaptic matrix (Rohrbough et al., 2007) certainly suggests disorganization/loss of multiple synaptic ECM components and ECM-binding proteins. Consistent with this prediction, targeted presynaptic mtg knockdown strongly decreases the level of position specific (PS) integrin synaptic expression, present in both pre- and postsynaptic membranes (Fig. 2; Table 1B) (Beumer et al., 1999; Rohrbough et al., 2000), causing a loss of NMJ localization of this ECM binding receptor (Rushton et al., 2009). Thus, interaction between synaptic membranes and the ECM are weakened in the absence of MTG. Moreover, since PS integrin receptors exist in a physical complex with the DLG scaffold and control calcium/calmodulin dependent kinase II (CaMKII) activation (Beumer et al., 2002), this MTG-dependent pathway also provides a mechanism to regulate localization of postsynaptic proteins in the GluR domain during synaptogenesis (Fig. 2). Similarly in mammals, the endogenous lectin galectins bind lactosamine residues (Hirabayashi et al., 2002), such as those found in the extracellular domain of β1 integrin chains, to organize lattice signaling microdomains at the cell surface (Perillo et al., 1995; Chung et al., 2000; Brewer et al., 2002; Braccia et al., 2003). Although this mechanism has not been studied at the vertebrate NMJ, it supports the possibility of a conserved glycan-dependent organizing event.

Mind-the-gap: modulator of trans-synaptic signaling

Integrins are just one component of MTG-regulated trans-synaptic signaling. The working hypothesis is that secreted MTG organizes a GlcNAc glycomatrix that coordinately regulates the multiple bidirectional signals that traverse the synaptic cleft between neuron and muscle (Fig. 2). For example, it was just recently shown that MTG strongly modulates the secreted signaling ligand Jelly Belly (Jeb) and its receptor tyrosine kinase Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (Alk), an anterograde signaling pathway from neuron to muscle (Bazigou et al., 2007; Palmer et al., 2009; Rohrbough and Broadie, 2010). In the Drosophila nervous system, this Jeb-Alk signaling activates transcription of downstream genes, including cell adhesion proteins and the TGFβ/BMP signal Dpp (Loren et al., 2001; Englund et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2003; Shirinian et al., 2007). At the Drosophila NMJ, Jeb is presynaptically secreted to reside in punctate domains closely associated with presynaptic boutons, while its Alk receptor exhibits a more uniform expression in the postsynaptic domain (Fig. 2) (Rohrbough and Broadie, 2010). This signaling array is set up during embryonic synaptogenesis and maintained throughout postembryonic development. In mtg null synapses, the Jeb signal is grossly over-expressed, with elevated levels, increased size of extracellular domains and an increased number of these domains throughout the synaptomatrix (Rohrbough and Broadie, 2010). Conversely, the postsynaptic Alk receptor expression is decreased, albeit to a lesser degree, potentially a reflection of the general postsynaptic misorganization (Table 1B). Although direct mutation of the Jeb-Alk pathway has not, as yet, been demonstrated to cause overt synaptogenesis defects, it is predicted that this pathway must regulate transcription modulating synapse formation and/or maintenance. Consistent with this hypothesis, Alk receptor signaling regulates TGFβ/BMP-dependent transcription in C. elegans (Reiner et al., 2008). By extension, at the Drosophila NMJ Jeb-Alk signaling could potentially regulate the TGFβ/BMP Gbb retrograde pathway involved in synaptic modulation (Aberle et al., 2002; Haghighi et al., 2003; McCabe et al., 2003; McCabe et al., 2004). Of course, such a mechanism would be in addition to the prediction that MTG directly regulates WNT-Wg and Gbb trans-synaptic signals as they navigate the synaptomatrix. Putative interactions with these signaling pathways have yet to be tested.

UNANSWERED QUESTIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The extracellular synaptomatrix is densely packed with glycoproteins and proteoglycans in highly compartmentalized domains (Figs. 1 and 2). Given the slender breadth of the synaptic cleft, even at the relatively spacious vertebrate NMJ, the size of synaptomatrix-resident molecules along with their numerous glycan modifications seems prohibitively large. How are these molecules packed into such a constrained space? One possibility is that we are underestimating the area based on classical ultrastructural analyses. Molecules loaded with negative charges, such as polysialic acid, can bind large amounts of water and the separation between synaptic partners may expand with the hydration volume of these molecules (Rutishauser, 1998). We also may be over-estimating the size of synaptomatrix molecules, based on predicted sites of glycosylation. This consideration raises the question of whether all predicted glycosylation sites are all occupied in mature synaptomatrix molecules. If not, what dictates the selective posttranslational modification of glycans on a particular synaptomatrix protein? Possibly the three dimensional structure of proteins effectively masks potential glycosylation sites, allowing only certain exposed domains to be modified. Further we know glycan modifications can be degraded by glycosidases or modified further by sulfation events, which indicates that glycan modifications are likely highly dynamic. Is the glycosylation status of synaptomatrix proteins locally regulated within the synaptic cleft? If so, what is the nature of these modifications, and what mechanisms control such dynamic shifts? Such mechanisms could lead to differential glycosylation of identical isoforms of synaptomatrix proteins in a spatial and/or temporal manner. Such mechanisms could also affect the signaling mediated by synaptomatrix localized glycoproteins and proteoglycans, and their interactions with trans-synaptic signaling molecules.

With increasing use of sophisticated chromatography and mass spectrophotometer techniques, the elucidation of complete glycan structures and the proteins to which they are bound are now being identified. In fact, the complete N-glycan profile was recently determined for Drosophila, which has helped enormously to determine similarities and differences with vertebrate glycomes (Koles et al., 2007). Similar future studies will be important to determine homologous structures that can then be targeted for further study in synaptic model systems amenable to genetic manipulation, such as Drosophila and C. elegans. In particular, the genetically-tractable Drosophila NMJ provides numerous means to study synaptic formation and function that could be systematically applied to the study of synaptomatrix glycobiology. Numerous specific glycans have been shown to localize to both vertebrate and Drosophila NMJs, albeit with some clear differences and many unknowns. For example, for the most part, it is not known whether a particular sugar modification plays a homologous function in both vertebrate and Drosophila systems. This may be difficult to determine as glycan modifications can form very diverse linear chains and branched combinations of different monosaccharides. Further, we cannot rule out the possibility of functionally similar, but structurally different, glycan modifications operating across different species. Comparative glycomic studies of specific neuron classes would help determine conserved roles of glycans in synaptogenesis across different synaptic types and in different model systems. Moreover, it must be remembered that glycosylation of proteins in the membrane and synaptic cleft is likely only part of the story, as membrane lipid molecules are also heavily glycosylated. For example, two Drosophila genes, egghead (egh) and braniac (brn) (Goode et al., 1996), encode enzymes responsible for glycosphingolipid biosynthesis, and mutation of both genes causes clear behavioral phenotypes (Chen et al., 2007). These glycosylated synaptomatrix bounding lipid molecules may have important roles in modulating trans-synaptic signaling akin to the more established glycoproteins and proteoglycans that regulate synapse formation.

Another interesting question is to determine the extent to which glycosylation, or glycan modification, is an absolute requirement for function of known synaptogenic proteins. This may well depend on the particular molecule or molecular function under consideration. For example, certain ionotropic glutamate receptors do not need glycan modifications to form a functional ligand binding site, but glycosylation affects trafficking and susceptibility to allosteric modification (Standley and Baudry, 2000). Moreover, glycans have been shown to play important roles in ligand dimerization or optimization of ligand-receptor interactions for many classes of transmembrane channels and receptors (Pellegrini et al., 2000; Schlessinger et al., 2000). Nevertheless, there are only a few types of glycan modification that have been shown to serve in this capacity; heparan sulfate being the best-studied example (Dreyfuss et al., 2009). The current data set is simply too limited to make any reasonable extrapolations. A great deal more study is required on the in vivo role of different classes of glycans, or glycan modifications, directing synaptogenic processes. The Drosophila NMJ is likely to remain the premier forward genetic system for pursuing these mechanisms. In addition to any variability in glycan identities, identical glycan modifications could be added post-translationally onto different proteins. This could be a mechanism to ensure molecular co-operativity, or to compartmentalize signaling reactions within specified sub-domains of the synaptomatrix. Given the roles of glycans mediating trans-synaptic signaling, such a flexible mechanism could ensure that robust signaling proceeds during crucial developmental processes of synaptogenesis and synaptic modulation.

Broadly during development, much intercellular communication is carried by signaling molecules of the WNT and TGF-β/BMP classes and received by Receptor Tyrosine Kinases (RTKs) (Gerhart, 1999; Kramer and Yost, 2003). Both ligands and RTKs are regulated by heparan sulfate glycan modifications (Hacker et al., 1997; Jackson et al., 1997; Lin et al., 1999). At the Drosophila NMJ, WNT (Wg) and TGF-β/BMP (Gbb) trans-synaptic signals navigate through the heavily glycosylated synaptomatrix to bind their respective receptors (Fig. 2). We propose here that the glycan-rich environment in the synaptomatrix likely directly modulates these trans-synaptic pathways during synaptogenesis, as has been clearly demonstrated in other arenas of development. For example, the HSPG Dlp that binds WNT-wingless to regulate its extracellular distribution in the developing Drosophila wing disc (Han et al., 2005). Dlp is enriched at the NMJ, along with another HSPG syndecan, where they control NMJ growth and presynaptic active zone assembly (Table 1) (Johnson et al., 2006). Thus, HSPGs through their glycan modifications are here hypothesized to modulate WNT signals, likely jointly with TGF-β/BMP signals (Rider, 2006) suggesting significant intersection between these pathways within the synaptomatrix. In this scenario, glycan structures could bind and modulate multiple trans-synaptic signals simultaneously to coordinately regulate interactions with their cognate receptors. These signals which could be stimulatory or inhibitory to the process of synaptogenesis, and therefore glycans may serve as platforms for signal integration that allow only the net effect of bound signaling molecules to determine synapse formation and modulation.

If trans-synaptic signals are modulated by glycans, then what modulates the glycans? We propose here that endogenous lectins are enormously important in shaping glycan distribution within the synaptomatrix environment. Mind-the-gap is one such lectin secreted into the Drosophila NMJ synaptomatrix, where it binds GlcNAc moieties (Rohrbough et al., 2007; Rushton et al., 2009). Interestingly, HS glycan modifications are abundant in GlcNAc residues, as this monosaccharide is repeated several times to form the final HS glycan chains (Lamanna et al., 2007). HS chains are also be modified by sulfate groups, with periodic highly sulfated regions (S-domains) interspersed by regions with almost no sulfation. We propose here that sulfation could provide an additional level of information processing to regulate trans-synaptic signaling (Lamanna et al., 2007). By binding GlcNAc-rich HS chains, Mtg is hypothesized to organize secreted and/or membrane-bound HSPGs in the synaptomatrix, to regulate synapse formation. Does Mtg interact directly with WNT and/or TGF-β/BMP trans-synaptic pathways through such a mechanism? Although this has not yet been tested, these pathway’s binding site preferences may be similar to other signaling molecules such as FGFs (Wu et al., 2002) and Antithrombin III (Kuberan et al., 2002) which bind sulfate rich domains. This leaves the GlcNAc moieties in non-sulfated regions open for recognition by Mtg, which could then drive organization of secreted or membrane anchored HSPGs. We have just recently shown that Mtg strongly modulates Jeb/Alk trans-synaptic signaling (Rohrbough and Broadie, 2010), in direct support of our core hypothesis. Clearly, the Jeb/Alk pathway could be regulated by similar mechanisms, perhaps in a combinatorial manner with other trans-synaptic pathways, and this possibility warrants further investigation.

It should be abundantly clear from the above discussion that glycan modification of the synaptomatrix plays critical roles in the formation of new synapses and the subsequent modulation of synaptic properties. This densely-packed extracellular compartment provides an interface environment where glycan-glycan and glycan-protein interactions occur in a restricted space, providing exciting scope for crosstalk between different trans-synaptic signaling pathways. The molecular mechanisms that govern synaptogenesis may very well intimately depend on the cumulative effects of integrated and intersecting intersections within the synaptic glycomatrix, where glycosylation determines ligand life-time and either facilitates or thwarts the presentation of ligand to receptor. Further studies of the synaptic glycomatrix in the context of synaptogenesis are expected to reveal mechanisms of cross-talk between established signaling pathways, and to yield insights into novel signaling mechanisms that direct synapse formation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jeffrey Rohrbough and Emma Rushton for figure 1 contributions and help with figure 1 construction, and for critical input on the manuscript. This work is supported by NIH R01 grant GM54544 to K.B.

References

- Aberle H, Haghighi AP, Fetter RD, McCabe BD, Magalhaes TR, Goodman CS. wishful thinking encodes a BMP type II receptor that regulates synaptic growth in Drosophila. Neuron. 2002;33:545–558. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00589-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ai XB, Do AT, Lozynska O, Kusche-Gullberg M, Lindahl U, Emerson CP. QSulf1 remodels the 6-O sulfation states of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans to promote Wnt signaling. Journal of Cell Biology. 2003;162:341–351. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aikawa J, Esko JD. Molecular cloning and expression of a third member of the heparan sulfate/heparin GlcNAc N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase family. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:2690–2695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akins MR, Biederer T. Cell-cell interactions in synaptogenesis. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2006;16:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albin SD, Davis GW. Coordinating structural and functional synapse development: Postsynaptic p21-activated kinase independently specifies glutamate receptor abundance and postsynaptic morphology. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:6871–6879. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1538-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmann F, Fabini G, Ahorn H, Wilson IBH. Genetic model organisms in the study of N-glycans. Biochimie. 2001;83:703–712. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(01)01297-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang LH, Kim J, Stepensky V, Hing H. Dock and Pak regulate olfactory axon pathfinding in Drosophila. Development. 2003;130:1307–1316. doi: 10.1242/dev.00356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arikawa-Hirasawa E, Rossi SG, Rotundo RL, Yamada Y. Absence of acetylcholinesterase at the neuromuscular junctions of perlecan-null mice. Nature Neuroscience. 2002;5:119–123. doi: 10.1038/nn801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ataman B, Ashley J, Gorczyca D, Gorczyca M, Mathew D, Wichmann C, Sigrist SJ, Budnik V. Nuclear trafficking of Drosophila Frizzled-2 during synapse development requires the PDZ protein dGRIP. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:7841–7846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600387103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ataman B, Ashley J, Gorczyca M, Ramachandran P, Fouquet W, Sigrist SJ, Budnik V. Rapid activity-dependent modifications in synaptic structure and function require bidirectional Wnt signaling. Neuron. 2008;57:705–718. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augsburger A, Schuchardt A, Hoskins S, Dodd J, Butler S. BMPs as mediators of roof plate repulsion of commissural neurons. Neuron. 1999;24:127–141. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80827-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustin H, Grosjean Y, Chen KY, Sheng Q, Featherstone DE. Nonvesicular release of glutamate by glial xCT transporters suppresses glutamate receptor clustering in vivo. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:111–123. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4770-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastiani MJ, Harrelson AL, Snow PM, Goodman CS. Expression of fasciclin-I and fasciclin-II glycoproteins on subsets of axon pathways during neurona development in the grasshopper. Cell. 1987;48:745–755. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazigou E, Apitz H, Johansson J, Loren CE, Hirst EMA, Chen PL, Palmer RH, Salecker I. Anterograde jelly belly and Alk receptor tyrosine kinase signaling mediates retinal axon targeting in Drosophila. Cell. 2007;128:961–975. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellaiche Y, The I, Perrimon N. Tout-velu is a Drosophila homologue of the putative tumour suppressor EXT-1 and is needed for Hh diffusion. Nature. 1998;394:85–88. doi: 10.1038/27932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernfield M, Gotte M, Park PW, Reizes O, Fitzgerald ML, Lincecum J, Zako M. Functions of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1999;68:729–777. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beumer K, Matthies HJG, Bradshaw A, Broadie K. Integrins regulate DLG/FAS2 via a CaM kinase II-dependent pathway to mediate synapse elaboration and stabilization during postembryonic development. Development. 2002;129:3381–3391. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.14.3381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beumer KJ, Rohrbough J, Prokop A, Broadie K. A role for PS integrins in morphological growth and synaptic function at the postembryonic neuromuscular junction of Drosophila. Development. 1999;126:5833–5846. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.24.5833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewick GS, Young C, Slater CR. Spatial relationships of utrophin, dystrophin, beta-dystroglycan and beta-spectrin to acetylcholine receptor clusters during postnatal maturation of the rat neuromuscular junction. Journal of Neurocytology. 1996;25:367–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezakova G, Ruegg MA. New insights into the roles of agrin. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2003;4:295–308. doi: 10.1038/nrm1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieber AJ, Snow PM, Hortsch M, Patel NH, Jacobs JR, Traquina ZR, Schilling J, Goodman CS. Drosophila neuroglian - a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily with extensive homology to the vertebrate neural adhesion molecule L1. Cell. 1989;59:447–460. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop JR, Schuksz M, Esko JD. Heparan sulphate proteoglycans fine-tune mammalian physiology. Nature. 2007;446:1030–1037. doi: 10.1038/nature05817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanik L, Framery B, Froelich A, Franco B, Mornet D, Bockaert J, Sigrist SJ, Grau Y, Parmentier ML. Muscle Dystroglycan Organizes the Postsynapse and Regulates Presynaptic Neurotransmitter Release at the Drosophila Neuromuscular Junction. Plos One. 2008:3. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchiellini C, Coulon J, LeParco Y. The function of type IV collagen during Drosophila muscle development. Mechanisms of Development. 1996;58:179–191. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(96)00574-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braccia A, Villani M, Immerdal L, Niels-Christiansen LL, Nystrom BT, Hansen GH, Danielsen EM. Microvillar membrane Microdomains exist at physiological temperature - Role of galectin-4 as lipid raft stabilizer revealed by “superrafts”. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:15679–15684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211228200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon EP, Lin WC, D’Amour KA, Pizzo DP, Dominguez B, Sugiura Y, Thode S, Ko CP, Thal LJ, Gage FH, Lee KF. Aberrant Patterning of neuromuscular synapses in choline acetyltransferase-deficient mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:539–549. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00539.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer CF, Miceli MC, Baum LG. Clusters, bundles, arrays and lattices: novel mechanisms for lectin-saccharide-mediated cellular interactions. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2002;12:616–623. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00364-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadie K, Bate M. Activity-dependent development of the neuromuscular synapse during embryogenesis. Neuron. 1993;11:607–619. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90073-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadie K, Bate M. Innervation directs receptor synthesis and localization in drosophila embryo synaptogenesis. Nature. 1993;361:350–353. doi: 10.1038/361350a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadie KS, Bate M. Development of the embryonic neuromuscular synapse of drosophila-melanogaster. Journal of Neuroscience. 1993;13:144–166. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-01-00144.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkin DJ, Kim JE, Gu MJ, Kaufman SJ. Laminin and alpha 7 beta 1 integrin regulate agrin-induced clustering of acetylcholine receptors. Journal of Cell Science. 2000;113:2877–2886. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.16.2877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler SJ, Dodd J. A role for BMP heterodimers in roof plate-mediated repulsion of commissural axons. Neuron. 2003;38:389–401. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CL, Huang SS, Huang JS. Cellular heparan sulfate negatively modulates transforming growth factor-beta(1) (TGF-beta(1)) responsiveness in epithelial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:11506–11514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KY, Augustin H, Featherstone D. Effect of ambient extracellular glutamate on Drosophila glutamate receptor trafficking and function. Journal of Comparative Physiology a-Neuroethology Sensory Neural and Behavioral Physiology. 2009;195:21–29. doi: 10.1007/s00359-008-0378-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Jiang XN, Sun DG, Han GH, Wang FJ, Ye ML, Wang LM, Zou HF. Glycoproteomics Analysis of Human Liver Tissue by Combination of Multiple Enzyme Digestion and Hydrazide Chemistry. Journal of Proteome Research. 2009;8:651–661. doi: 10.1021/pr8008012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YW, Pedersen JW, Wandall HH, Levery SB, Pizette S, Clausen H, Cohen SM. Glycosphingolipids with extended sugar chain have specialized functions in development and behavior of Drosophila. Developmental Biology. 2007;306:736–749. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu AY, Ugozolli M, Meiri K, Ko J. Purification and lectin-binding properties of s-laiminin, a synaptic isoform of the laminin-B1 chain. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1992;59:10–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb08869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CD, Patel VP, Moran M, Lewis LA, Miceli MC. Galectin-1 induces partial TCR zeta-chain phosphorylation and antagonizes processive TCR signal transduction. Journal of Immunology. 2000;165:3722–3729. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.3722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins CA, DiAntonio A. Synaptic development: insights from Drosophila. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2007;17:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crnefinderle N, Sketelj J. Congruity of acetylcholine-receptor, acetylcholinesterase and Dolichos-biflorus lectin binding glycoprotein in postsynaptic-like sarcolemmal specializations in noninnervated regenerating rat muscles. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 1993;34:67–78. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490340108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damico P, Jacobs JR. Lectin histochemistry of the Drosophla embryo. Tissue & Cell. 1995;27:23–30. doi: 10.1016/s0040-8166(95)80005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GW, Schuster CM, Goodman CS. Genetic dissection of structural and functional components of synaptic plasticity.3. CREB is necessary for presynaptic functional plasticity. Neuron. 1996;17:669–679. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bernabe DBV, Currier S, Steinbrecher A, Celli J, van Beusekom E, van der Zwaag B, Kayserili H, Merlini L, Chitayat D, Dobyns WB, Cormand B, Lehesjoki AE, Cruces J, Voit T, Walsh CA, van Bokhoven H, Brunner HG. Mutations in the O-mannosyltransferase gene POMT1 give rise to the severe neuronal migration disorder Walker-Warburg syndrome. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2002;71:1033–1043. doi: 10.1086/342975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis JW, Nabi IR, Demetriou M. Metabolism, Cell Surface Organization, and Disease. Cell. 2009;139:1229–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhoot GK, Gustafsson MK, Ai XB, Sun WT, Standiford DM, Emerson CP. Regulation of Wnt signaling and embryo patterning by an extracellular sulfatase. Science. 2001;293:1663–1666. doi: 10.1126/science.293.5535.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick A, Hild M, Bauer H, Imai Y, Maifeld H, Schier AF, Talbot WS, Bouwmeester T, Hammerschmidt M. Essential role of Bmp7 (snailhouse) and its prodomain in dorsoventral patterning of the zebrafish embryo. Development. 2000;127:343–354. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dityatev A, Schachner M, Sonderegger P. The dual role of the extracellular matrix in synaptic plasticity and homeostasis. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2010;11:735–746. doi: 10.1038/nrn2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dityatev A, Seidenbecher CI, Schachner M. Compartmentalization from the outside: the extracellular matrix and functional microdomains in the brain. Trends in Neurosciences. 2010;33:503–512. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfuss JL, Regatieri CV, Jarrouge TR, Cavalheiro RP, Sampaio LO, Nader HB. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans: structure, protein interactions and cell signaling. Anais Da Academia Brasileira De Ciencias. 2009;81:409–429. doi: 10.1590/s0001-37652009000300007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton BA, Davis GW. LIM Kinase1 controls synaptic stability downstream of the type IIBMP receptor. Neuron. 2005;47:695–708. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins T, Hortsch M, Bieber AJ, Snow PM, Goodman CS. Drosophila fasciclin-I is a novel homophilic adhesion molecule that along with fasciclin-III can mediate cell sorting. Journal of Cell Biology. 1990;110:1825–1832. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.5.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo M, Ohashi K, Sasaki Y, Goshima Y, Niwa R, Uemura T, Mizuno K. Control of growth cone motility and morphology by LIM kinase and slingshot via phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of cofilin. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:2527–2537. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02527.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T. O-mannosyl glycans in mammals. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-General Subjects. 1999;1473:237–246. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(99)00182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund C, Loren CE, Grabbe C, Varshney GK, Deleuil F, Hallberg B, Palmer RH. Jeb signals through the Alk receptor tyrosine kinase to drive visceral muscle fusion. Nature. 2003;425:512–516. doi: 10.1038/nature01950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone DE, Rushton E, Broadie K. Developmental regulation of glutamate receptor field size by nonvesicular glutamate release. Nature Neuroscience. 2002;5:141–146. doi: 10.1038/nn789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone DE, Rushton EM, Hilderbrand-Chae M, Phillips AM, Jackson FR, Broadie K. Presynaptic glutamic acid decarboxylase is required for induction of the postsynaptic receptor field at a glutamatergic synapse. Neuron. 2000;27:71–84. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong SW, McLennan IS, McIntyre A, Reid J, Shennan KIJ, Bewick GS. TGF-beta 2 alters the characteristics of the neuromuscular junction by regulating presynaptic quantal size. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:13515–13519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001695107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MA, Ho MSP, Smyth N, Sanes JR. A synaptic nidogen: Developmental regulation and role of nidogen-2 at the neuromuscular junction. Neural Development. 2008:3. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-3-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MA, Sanes JR, Borza DB, Eswarakumar VP, Fassler R, Hudson BG, John SWM, Ninomiya Y, Pedchenko V, Pfaff SL, Rheault MN, Sado Y, Segal Y, Werle MJ, Umemori H. Distinct target-derived signals organize formation, maturation, and maintenance of motor nerve terminals. Cell. 2007;129:179–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franciscovich AL, Mortimer AAV, Freeman AA, Gu J, Sanyal S. Overexpression Screen in Drosophila Identifies Neuronal Roles of GSK-3 beta/shaggy as a Regulator of AP-1-Dependent Developmental Plasticity. Genetics. 2008;180:2057–2071. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.085555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco B, Bogdanik L, Bobinnec Y, Debec A, Bockaert JRL, Parmentier ML, Grau Y. Shaggy, the homolog of glycogen synthase kinase 3, controls neuromuscular junction growth in Drosophila. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:6573–6577. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1580-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredieu JR, Mahowald AP. Glycoconjugate expression during drosophila embryogenesis. Acta Anatomica. 1994;149:89–99. doi: 10.1159/000147562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhart J. 1998 Warkany Lecture: Signaling pathways in development. Teratology. 1999;60:226–239. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199910)60:4<226::AID-TERA7>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogel S, Wakefield S, Tear G, Klambt C, Gordon-Weeks PR. The Drosophila microtubule associated protein Futsch is phosphorylated by Shaggy/Zeste-white 3 at an homologous GSK3 beta phosphorylation site in MAP1B. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience. 2006;33:188–199. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode S, Melnick M, Chou TB, Perrimon N. The neurogenic genes egghead and brainiac define a novel signalling pathway essential for epithelial morphogenesis during Drosophila oogenesis. Development. 1996;122:3863–3879. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.3863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorczyca D, Ashley J, Speese S, Gherbesi N, Thomas U, Gundelfinger E, Gramates LS, Budnik V. Postsynaptic membrane addition depends on the discs-large-interacting t-SNARE gtaxin. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:1033–1044. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3160-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham A, Franciswest P, Brickell P, Lumsden A. The signaling molecule BMP4 mediates apoptosis in the rhombencephalic neural crest. Nature. 1994;372:684–686. doi: 10.1038/372684a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grow WA, Ferns M, Gordon H. Agrin-independent activation of the agrin signal transduction pathway. Journal of Neurobiology. 1999;40:356–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grow WA, Gordon H. Sialic acid inhibits agrin signaling in C2 myotubes. Cell and Tissue Research. 2000;299:273–279. doi: 10.1007/s004419900146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habuchi H, Tanaka M, Habuchi O, Yoshida K, Suzuki H, Ban K, Kimata K. The occurrence of three isoforms of heparan sulfate 6-O-sulfotransferase having different specificities for hexuronic acid adjacent to the targeted N-sulfoglucosamine. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:2859–2868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker U, Lin XH, Perrimon N. The Drosophila sugarless gene modulates Wingless signaling and encodes an enzyme involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis. Development. 1997;124:3565–3573. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.18.3565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker U, Nybakken K, Perrimon N. Heparan sulphate proteoglycans: The sweet side of development. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2005;6:530–541. doi: 10.1038/nrm1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen KGT, Zhang LP, Tian E, Zhang Y. Glycobiology on the fly: Developmental and mechanistic insights from Drosophila. Glycobiology. 2009;19:102–111. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haghighi AP, McCabe BD, Fetter RD, Palmer JE, Hom S, Goodman CS. Retrograde control of synaptic transmission by postsynaptic CaMKII at Drosophila neuromuscular. Neuron. 2003;39:255–267. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00427-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines N, Seabrooke S, Stewart BA. Dystroglycan and protein O-mannosyltransferases 1 and 2 are required to maintain integrity of Drosophila larval muscles. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2007;18:4721–4730. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-01-0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines N, Stewart BA. Functional roles for beta 1,4-N-acetlygalactosaminyltransferase-A in Drosophila larval neurons and muscles. Genetics. 2007;175:671–679. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.065565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]