Abstract

Objective

To understand the complex effects of interruption in healthcare.

Materials and methods

As interruptions have been well studied in other domains, the authors undertook a systematic review of experimental studies in psychology and human–computer interaction to identify the task types and variables influencing interruption effects.

Results

63 studies were identified from 812 articles retrieved by systematic searches. On the basis of interruption profiles for generic tasks, it was found that clinical tasks can be distinguished into three broad types: procedural, problem-solving, and decision-making. Twelve experimental variables that influence interruption effects were identified. Of these, six are the most important, based on the number of studies and because of their centrality to interruption effects, including working memory load, interruption position, similarity, modality, handling strategies, and practice effect. The variables are explained by three main theoretical frameworks: the activation-based goal memory model, prospective memory, and multiple resource theory.

Discussion

This review provides a useful starting point for a more comprehensive examination of interruptions potentially leading to an improved understanding about the impact of this phenomenon on patient safety and task efficiency. The authors provide some recommendations to counter interruption effects.

Conclusion

The effects of interruption are the outcome of a complex set of variables and should not be considered as uniformly predictable or bad. The task types, variables, and theories should help us better to identify which clinical tasks and contexts are most susceptible and assist in the design of information systems and processes that are resilient to interruption.

Keywords: Human error, interruption, human computer interaction, cognitive psychology, usability, patient safety, incident reporting, communication, decision support, safety

Introduction

Interruptions seem inherent in the way work is undertaken in many clinical settings.1 2 Numerous studies have characterized this phenomenon over the last decade, and have examined the extent to which healthcare workers are interrupted while undertaking routine tasks. Hospital doctors and nurses are interrupted anywhere from once every 2 h to 23 times every hour in emergency, intensive care, and surgery.3 In certain types of clinical tasks, interruptions may pose a substantial risk to patient safety.4

While there is solid evidence from psychology about the disruptive effects of interruption on human cognition,5 6 few studies have quantified the effects on clinical tasks. In the emergency department, doctors failed to return to 19% of interrupted tasks.7 Interruptions and distractions have been reported as a factor contributing up to 11% of medication-dispensing errors.8 On hospital wards, interruption to nurses administering medications was associated with a 12% increase in procedural failure and a 13% increase in clinical error.9 Interruptions also have a time cost. In one study, clinical staff in an emergency department spent 24% of their time dealing with interruptions.10

Yet interruption is a complex phenomenon where multiple variables including characteristics of the primary task, interruption, and environment may influence patient safety and workflow outcomes.11 As interruptions are not all bad, it is necessary to understand the specific circumstances under which they are likely to be harmful.12 13 Recent reviews of the literature in healthcare have found that most studies were observational, describing the frequency, duration, and types of interruptions.3 13 The reviews conclude that it is currently not possible to be certain about the causal links between interruptions and errors in healthcare—although more recent studies are now showing evidence of that causality.7 9

As interruptions have been well studied in non-healthcare domains such as psychology and human–computer interaction (HCI),14 this literature provides a starting point. In this paper, we sought to review experimental studies to systematically identify the task types and variables influencing the effects of interruption on patient safety and task efficiency.

Definitions and theoretical frameworks

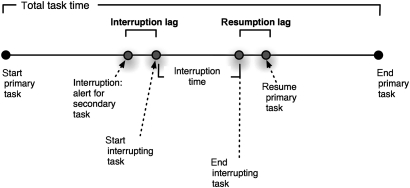

A primary task is defined as the main activity that is interrupted (figure 1). An interruption is a secondary activity that requires one's attention and stops interaction with the primary task. Interruption effects are typically quantified by examining time costs and errors using measures such as:

Figure 1.

Time-course of an interruption (adapted from Trafton et al15).

Resumption lag: the time taken to re-orient and restart the primary task after interruption.15

Interruption lag: the time taken between acknowledging a pending interruption and disengaging from the primary task to respond to the interruption measures responsiveness.

Total time on task: the time taken to complete a primary task (task completion time) less the resumption lag, interruption lag, and interruption task time.

Task accuracy: measured by error occurrences. A normalized error rate—ratio of number of errors to number of opportunities for that error—is used to compare effects across tasks.6 16

Three frameworks most relevant to understanding interruption effects in healthcare are the following.

The activation-based goal memory (AGM) model which has been applied to investigate the disruptiveness in a range of tasks including tactical decision-making,15 problem-solving,17 18 and procedural tasks.6 19 The model's basic premise is that goals have associated activation levels, just like other memory elements in the cognitive system, and cognition is directed by the most active goal retrieved at any given time. The amount of activation associated with a memory item is subject to decay, and this decay process is time-based and gradual. If the cognitive system needs to refocus attention to (or resume) an old goal, then this old goal needs to undergo a priming process to become active again. The priming process is possible through associative links between retrieval cues and the to-be-resumed goal. A retrieval cue can be internal, residing in the cognitive system; a procedural task step can act as a cue for the subsequent step. The execution of task steps in a procedural task can be viewed as a sequence of associative links, each action step acting as a retrieval cue for the next step. On the other hand, a retrieval cue can also be external, residing in the environment; for example, a loud beeping signal in a ticket machine when it returns change can prime the action of collecting the change provided that the relationship between the cue (the beep) and the action (collection of change) is learned.

Prospective memory (PM) is the ability to remember to execute an intention in the future,3 ‘… interrupting an ongoing task intrinsically creates a prospective memory task: the individual must remember to resume the interrupted task without explicit prompt, a defining characteristic of prospective memory tasks.’ (Dodhia and Dismukes,20 2009, p74).

Multiple resource theory (MRT)21 is primarily concerned with predicting and explaining multi-tasking performance—that is, performing two tasks concurrently. The basic tenet of MRT is that, when two tasks compete for the same processing resource within any of the four dichotomous task dimensions (stages of processing, codes of processing, modalities, and visual channels), performance is likely to be hampered. The most relevant dimension in the current context is modalities; this dimension indicates that different processing resources are used by the auditory and visual senses. Interruption manifests itself in MRT through the notion of cognitive resource allocation. In a multi-tasking situation when one task consumes all the processing resources leaving no resources for another task, execution of the other task is abandoned. This situation can be interpreted as interruption, as the concurrent task processing is suspended.

Methods

Four searches of the literature were carried out between June and August 2009 (online appendix A). The first search for review articles in PsycInfo, Ergonomics Abstracts, Compendex, and Inspec from 1989 to 2009 yielded 82 articles, of which two were relevant.22 23 The only systematic review was retrieved by hand search.3 A second citation search of these articles3 17 18 using Scopus and ISI Web of Science identified eight articles. The third search for experimental studies on interruption from psychology and HCI using PsycInfo, Ergonomics Abstracts, Compendex, and Inspec from 2002 onwards identified 63 articles. A fourth manual search of the ‘Interruptions in HCI’ website found five articles.24 Two authors (SYWL, FM) reviewed the titles and abstracts, and resolved disagreements by discussion.

Studies that met the following criteria were included: (i) controlled experiments; (ii) examining ‘real world’, computer-based, or artificial tasks such as games with routine procedures, problem solving, or decision-making components. Theoretical papers on interruption were also included. Studies with (i) highly abstract or micro-scale tasks (for example, interruption to finger-tapping task25), (ii) examining effects of ageing, or (iii) primarily concerned with tool building in engineering26 27 were excluded. Our analyses focused on primary task characteristics, independent variables, and underpinning theories.

Findings

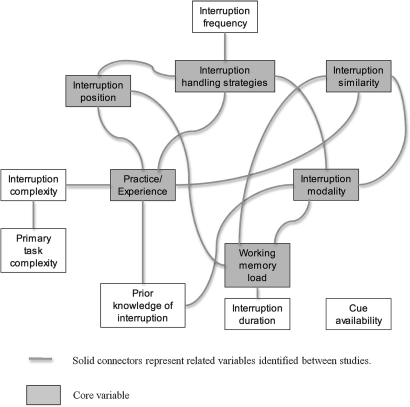

Among the 79 papers, 63 experimental studies (online appendix B1 and B2) were analyzed. We identified three primary task types (procedural, problem-solving, and decision-making) and 12 independent variables associated with interruption effects (figure 2). Overall, interruption has a negative effect on task completion time,28 29 resumption lag,30 work strategy,31 decision-making process,32 and error.33 34 However, interruptions may sometimes result in faster task completion time,31 but at the expense of increased perceived workload and stress.

Figure 2.

Network of interruption variables' relations. Gray squares indicate variables central to the network.

Primary task types

Our analysis revealed that clinical tasks can be abstracted into the generic task types of procedural, problem-solving, and decision-making. This task classification scheme has long been used in experimental psychology to study human behavior35 36 and is also supported by studies of human error and interruption.6 15 16 37

Procedural task performance relies on procedural knowledge obtained through training, and execution is usually automatic rather than requiring conscious calculation. Examples include document editing and web searching,38 fictional game tasks6 16 to routine tasks, such as coffee making.39 In clinical settings, procedural tasks can range from electronic order entry or medication administration to surgical tasks such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Problem-solving tasks usually require active mental processing involving conscious calculations. Examples include crossword puzzles,40 mathematical problems,41 and psychological tasks such as the Tower of London task.17 18 42 Examples of clinical problem-solving tasks can be found in the emergency department, where doctors are routinely confronted with novel situations: their clinical knowledge might not offer them a direct solution, but provides the basis to work out an appropriate solution.

Decision-making tasks involve conscious mental calculation to choose from a set of options—for example, military tactical assessment,15 stock trading,43 and project management.44 Assessment of treatment options for a geriatric patient with cancer is a clinical example. The surgeons involved in the decision-making process need to consider factors such as post-surgery life expectancy and quality, which often involves the patient's and family's preferences.

As interruption effects vary by task type, the categorization serves as a useful conceptual tool for researchers to deconstruct potential effects in disparate clinical tasks. For example, interruption to decision-making is associated with different information-processing abilities32 resulting in more risk-taking behaviors and less sensitivity to options with extra costs. The effectiveness of practice to mitigate disruption also depends on task type. While practice on a procedural task may minimize disruption, it may not work on decision-making.

Experimental variables

Of the 12 variables, we identified six that are most important based on the number of studies (each core variable was examined in six or more studies) and the number of connections between variables (table 1). The connections between the variables were identified by our interpretation of the links between the studies' findings and/or methodologies. The six core variables have more connections with each other than with the other variables. We report on the six: working memory load, interruption position, similarity, modality, handling strategies, and practice effect.

Table 1.

Studies linking interruption variables

| Association* | Description of the variables' association | Studies† |

| Primary task complexity—interruption complexity | Disruptiveness increases with complexity of the primary task and interruption | 44–47 |

| Practice/experience—interruption complexity | Practice can counter disruptiveness from complex interruptions | 48 |

| Practice/experience—interruption position | Practice can make certain task positions less susceptible to disruption | 6 |

| Practice/experience—interruption-handling strategies | Practice on handling interruption rather than just on the primary task is beneficial | 49 |

| Practice/experience—interruption similarity | Practice dampens disruptive effects of an interruption that is similar to the primary task | 41 48–50 |

| Practice/experience—prior knowledge of interruption | Prior knowledge of an interruption may not provide extra beneficial effects over practice | 15 |

| Interruption position—interruption-handling strategies | Control over when to handle an interruption may reduce disruption | 40 51 |

| Interruption position—working memory load | Working memory load varies by interruption position | 14 19 43 52 53 |

| Interruption-handling strategies—interruption frequency | Interruption-handling strategies are affected by frequency of interruption | 49 |

| Interruption-handling strategies—interruption modality | Interruption-handling strategies are dependent on the modality or cognitive mechanism of a primary task | 54 55 |

| Interruption similarity—working memory load | Interruption involving a high working memory demand task that is highly similar to the primary task hampers task performance | 41 |

| Interruption modality—interruption similarity | Interruptions involving the same modalities or cognitive mechanisms as the primary task are particularly disruptive | 54 55 |

| Interruption modality—working memory load | Interruption to a different modality from the primary task impacts working memory load | 56 57 |

| Interruption modality—prior knowledge of interruption | Prior knowledge of an interruption's modality affects handling strategies | 54 55 58 |

| Working memory load—interruption duration | Longer interruptions are associated with higher working memory load | 59 |

Association between interruption variables.

Studies that identified associations between variables.

Working memory load

Interruption at high working memory load is usually associated with decreased primary task performance,37 60 although learning has been shown to improve efficiency in problem-solving tasks.61 Effects are dependent on the primary task type, whether an interruption is similar to the primary task (interruption similarity), and where in the primary task the interruption occurs (interruption position). Multi-tasking taxes working memory and is common in hospitals (eg, responding verbally to a question while using an e-prescribing system). Whether task performance is degraded depends on how similar the content of the verbal interruption is to the prescribing task and when the interruption occurs during execution of the prescribing task. In e-prescribing, potentially life-threatening prescribing errors can easily occur if the interruption is while a complex protocol for a cytotoxic medication in cancer therapy is being specified (ie, when working memory load is high).

Interruption similarity

An interruption that is similar to the primary task is more likely to disrupt task performance than a dissimilar interruption, resulting in poorer memory,50 62 task efficiency,37 and spatial memory upon task resumption.63 Interruptions that demand the same cognitive mechanism as the primary task produce interference-inhibiting task performance. The opposite or null effect observed in some studies is explained by disparity in task types and outcome measures.31 44 49 64

Interruption similarity is important in clinical environments. For example, if a nurse is carrying out a documentation task for patient A and is interrupted to complete the same type of document for patient B, patient A's document may be affected by patient B's information. Such documentation errors could potentially lead to inappropriate investigations or procedures resulting in serious consequences. However, if the nurse is interrupted by a very different task, such as a general request about ward policy, then the chances of the primary task being affected are lower.

According to the AGM model, disruption associated with similarity to the primary task is due to interference between similar goals, resulting in the wrong goal being retrieved. Upon task resumption, an old goal from the primary task needs to be retrieved correctly. However, when an interruption is very similar to the primary task, interference during the retrieval process results in a similar but incorrect goal. Therefore, the likelihood of errors upon task resumption increases with similarity to the primary task. When information is encoded from short-term working memory to long-term working memory, it becomes relatively immune to such effects.62 Based on the notion of associative cueing in the AGM model, disruptive effects can also be countered by strong memory associations in primary task elements,50 implying that practice or experience may be key to counter the disruption caused by interruption similarity or interruption in general.

Interruption position

As demands on cognitive resources are more intense during task execution than in between tasks, interruptions occurring during execution have been consistently shown to be more disruptive than those occurring in between.14 17 19 38 43 52 65 Decreased mental workload at task boundaries is supported by a study that used pupil size to measure workload changes during task performance.53 As with interruption similarity, the AGM model is useful in predicting the effects of interruption position.6 17 19 52 Based on this model, mid-task interruptions are associated with more competing goals for the cognitive system to encode at the point of task resumption than those occurring in between tasks.17 19 52 The model's associative cueing mechanism also suggests that omission errors, such as post-completion error, are more likely to occur immediately after the interruption because of disruption to associative links in procedural tasks.6

Consistent with effects associated with working memory demand, interruption at positions with high working memory demand are likely to be more disruptive than at low-demand positions. In clinical settings, working memory demand when an e-prescribing system is being used might vary during the prescribing process.66 Analyses of such tasks using techniques from cognitive engineering—for example, GOMS67—might be useful in predicting the impact of interruption at different points in the task based on working memory load.

The effect of interruption position also has implications for interruption-handling strategies.40 51 The ability to choose where in a primary task to handle an interruption can minimize disruption. For instance, experienced secretaries tend to delay responding to an interruption until they have completed what they set out to do in a primary task.49 Similarly in clinical settings, a nurse may choose to complete administering medications to patient A before responding to an inquiry from a junior nurse about discharge arrangements for patient B. In this example, errors in administering medication could involve the wrong dosage, route, time, frequency, or the medication itself, potentially leading to an adverse event.

Interruption modality

Interruptions presenting to a different modality from the primary task reduce disruption to task performance54–58 68 and have consequences for interruption-handling strategies. In healthcare, interruptions often involve a different handling modality. A phone call requires the auditory modality, whereas the electronic ordering of laboratory tests predominantly uses the visual modality. While a doctor may easily deal with a phone call while undertaking a visually oriented primary task, such as x-ray examination, an interruption involving an electronic ordering task could potentially lead to errors in interpreting the x-ray.

The effect of interruption modality can be related to interruption similarity, as interruptions that are similar to the primary task are likely to share the same cognitive mechanism and more likely to disrupt task performance than dissimilar interruptions.63 Based on MRT, cross-modality interruptions produce the least disruption because they utilize non-overlapping cognitive resources.54–58 68 Ratwani et al69 went further and contrasted predictions made from MRT and the AGM model, suggesting that the presence of cues about the primary task during interruption can sometimes be more effective in aiding task resumption than cross-modality presentation of the interruption.

Other studies have extended MRT to accommodate the tactile sensory modality54 55 and combine it with PM to show how tactile cues are better than auditory cues in alleviating memory demands in a monitoring situation. A similar approach has been used to show how tactile cues, as compared with visual cues, changed the nature of a notification detection task from a time-based (resource-intensive) to an event-based (less resource-intensive) monitoring task.56 57 A time-based PM task requires constant monitoring; for example, a patient trying to remember to take a medication at a certain hour must constantly keep track of the time. In contrast, in an event-based PM task, when setting an alarm to take the medication, the patient makes an association with the event (alarm) that prompts the PM action (medication), and therefore no constant monitoring is required. Time-based and event-based monitoring tasks have different demands on working memory, with a resource-intensive time-based monitoring task requiring more working memory capacity than the less resource-intensive event-based monitoring task.

Practice/experience

Studies on the effect of practice/experience identify two main findings. First, practice on the primary task can free up cognitive resources to better deal with interruptions.70 Practice can increase the memory associations of primary task elements, which in turn result in better defense against interruptions.6 50 Based on the notion of associative cueing in the AGM model, the associative links between task steps in a procedural task become strengthened with practice.6 50 70 The stronger the associative links the more immune they become to the disruptive effects of interruption.

Second, practice with interruption handling mitigates task disruption.15 41 71 In other words, practice in dealing with interruptions increases efficiency in primary task performance. As discussed above, to combat effectively against interruptions through practice, it is essential to understand the nature of the task being interrupted: practice should be placed on the primary task if it is a procedural task, whereas interruption handling should be practiced for a decision-making task. Practice on the primary task might be particularly relevant to procedural tasks, such as remembering to check the five rights of medication administration (right patient, right dose, right route, right time, and right medication), in which the same procedure is applied across different patients. Practice on interruption handling may be more applicable to primary tasks that involve decision-making. For example, a doctor may practice a range of strategies to handle interruptions during a primary care consultation that predominantly involves decision-making tasks. Finally, experience with interruption not only affects interruption handling strategies but also perception of the interruption, which has a direct impact on the affective state of a clinician dealing with the interruption.49

Interruption-handling strategies

Having some control over when to deal with interruptions is less disruptive to task performance than having no control.40 42 51 72 The beneficial effect is not limited to improved task performance, but also extends to better affective states73 74 and can also be achieved even by having a sense of control rather actual control.73 Clinicians use different strategies to handle interruptions. Consider a doctor prescribing medications who is interrupted by a phone call.

Attend to interruption: the doctor may choose to take the call immediately or, with a momentary delay, to rehearse the name of the next medication to be prescribed. This can be effective in reducing interruption disruptiveness. When attending to the interruption, the doctor may either completely switch to the interrupting task (ie, suspend prescribing) or multi-task (ie, prescribe while on the phone).

Delay interruption: the doctor may choose to switch off the phone and check for a message after finishing the prescribing task.

Having a repertoire of interruption-handling strategies reduces the likelihood of making medication errors in a prescribing task.

Discussion

Understanding interruption effects

We reviewed experimental studies in psychology and HCI to systematically identify a network of 12 variables influencing the effects of interruption on patient safety and task efficiency. Of these, working memory load, interruption position, similarity, modality, handling strategies, and practice effect are the most important based on their centrality to the network of interruption variables and the number of studies identified. The variables and their connections illustrate the complex multidimensional nature of interruption. Based on the profile of interruption effects that we found in the literature, clinical tasks can be distinguished into three broad types: procedural, problem-solving, and decision-making. We have shown that theoretical frameworks such as the AGM model, PM and MRT are useful for explaining some of the important interruption effects in healthcare. The review gives health informatics researchers a useful starting point to examine and understand the effects of interruption. The variables, task types, and theories provide a framework for using appropriate methodologies, including observational studies, controlled experiments, and computational models to identify the situations where interruption is dangerous,11 and to design work processes and information systems that are resilient to interruption effects.

Dealing with interruptions

Based on our findings, we provide some recommendations to minimize the disruptive effects of interruption in clinical settings.

Interruptions at positions with high working memory demands within a task sequence should be minimized or avoided if possible. In clinical settings, it is possible to analyze tasks that are primarily procedural (eg, e-prescribing) by adopting task analysis techniques, such as GOMS,67 from cognitive engineering. Once task positions of high working memory demands are identified, procedures can be engineered or clinicians trained to avoid interruptions when engaged at those task points. Operationally, this knowledge is of particular importance to IT system designers who should aim to design systems with minimal cognitive load when they are intended for use in busy environments.

Use practice on tasks to minimize disruption. Repeated practice is associated with decreased disruption from interruptions, and consequently clinical staff can be trained on tasks that are particularly susceptible to interruption and interrupting tasks. Whether to place practice on the primary task or interruption handling should depend on the task type. If the primary task is highly procedural, then practicing the primary task should help reduce the impact of interruption because of strengthened associative memory of the task. If the primary task is a problem-solving or decision-making task, then practice should be focused on how to handle the interruption.

Train clinical staff in interruption-handling strategies. Improved sense of control over interruptions can lead to better affective states, such as reduced stress level, frustration, and annoyance and improved primary task performance. Clinical staff should be instilled with a sense of control over interruptions by teaching them different interruption-handling strategies—for example, immediate attendance to interruption, multi-task, or delayed attendance to interruption.

Provide environmental cues to aid recovery from interruptions. Recovery from interruption is enhanced if there are cues in the environment that provide reminders about a previous task and its state. When information systems are designed for use in interruptive environments, user interface features that allow users to rapidly review their current activity state can minimize negative effects from interruption. For example, a prolonged period of inactivity may suggest distraction from using an e-prescribing system, and this can trigger the system to automatically highlight the last action on screen. This highlighting function may serve as an explicit reminder of the previous action performed before the interruption.

Limitations of this review

While a range of methodologies are used to examine interruption effects,11 the scope of the current review was limited to experimental studies to enable the discovery of causal relationships between the interruption variables. Another limitation is our ability to directly translate its findings to the clinical domain. This is largely due to the inherent nature of experimental studies which are often laboratory based and cannot faithfully replicate the context of naturalistic clinical settings.

In addition, certain constructs in psychology tend to be ambiguous. For example, there is no consensus about how best to operationalize the complexity of primary tasks or interruptions. While some researchers66 rely on quantitative methods from cognitive engineering,67 others rely on subjective judgment.75 Finally, there appear to be inconsistencies in some experimental findings because of disparities in task paradigms and outcome measures. Consequently, it is difficult to generalize a finding across a set of studies using disparate experimental paradigms. This is even more problematic when generalizing to the clinical domain. Decomposing clinical tasks into procedural, problem-solving, and decision-making elements is not clear-cut. Moreover, effects of interruptions in the real world are likely to be influenced by a range of clinical, social, and organizational variables. For example, the importance and urgency of a primary patient care task in an emergency department may affect whether or not a clinician decides to suspend it or gives it extra focus following an interruption. Despite these difficulties in directly applying experimental findings to the clinical domain, the current review has identified six core variables and three generic task types that provide a map of the interruption landscape.

Conclusion

The effects of interruption are best understood as the outcome of a complex set of variables and should not be considered as uniformly predictable or bad. In the context of understanding the effects of interruption on clinical work, and on the use of information technologies in the healthcare system, we have identified three main theories and a set of six core variables that seem most likely to predict outcome. We have also identified three main task types from the experimental studies with different interruption profiles—procedural, problem-solving, and decision-making tasks. The theories, task types, and variables should help us better identify which clinical tasks and contexts are most susceptible to the effect of interruption, and also assist in the design of information systems and processes that are resilient to interruption.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the reviewers for helpful suggestions for improvement. The review was carried out when SYWL was Research Associate at the Centre for Health Informatics, University of New South Wales. He is now at the Department of Sociology and Social Policy, Lingnan University, Hong Kong.

Footnotes

Funding: This research is supported in part by grants DP0772487 and LP0775532 from the Australian Research Council and by NHMRC Program Grant 568612.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Coiera E. Clinical communication: a new informatics paradigm. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp 1996:17–21 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coiera E, Tombs V. Communication behaviours in a hospital setting: an observational study. BMJ 1998;316:673–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grundgeiger T, Sanderson P. Interruptions in healthcare: theoretical views. Int J Med Inform 2009;78:293–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parker J, Coiera E. Improving clinical communication: a view from psychology. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2000;7:453–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altmann EM, Trafton JG. Timecourse of recovery from task interruption: data and a model. Psychon Bull Rev 2007;14:1079–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li SYW, Blandford A, Cairns P, et al. The effect of interruptions on postcompletion and other procedural errors: an account based on the activation-based goal memory model. J Exp Psychol Appl 2008;14:314–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Westbrook JI, Coiera E, Dunsmuir WT, et al. The impact of interruptions on clinical task completion. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:284–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashcroft DM, Quinlan P, Blenkinsopp A. Prospective study of the incidence, nature and causes of dispensing errors in community pharmacies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2005;14:327–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westbrook JI, Woods A, Rob MI, et al. Association of interruptions with an increased risk and severity of medication administration errors. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:683–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spencer R, Coiera E, Logan P. Variation in communication loads on clinical staff in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2004;44:268–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magrabi F, Li SY, Dunn AG, et al. Why is it so difficult to measure the effects of interruptions in healthcare? Stud Health Technol Inform 2010;160:784–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magrabi F, Li SY, Day RO, et al. Errors and electronic prescribing: a controlled laboratory study to examine task complexity and interruption effects. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2010;17:575–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rivera-Rodriguez AJ, Karsh BT. Interruptions and distractions in healthcare: review and reappraisal. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:304–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bailey BP, Konstan JA, Carlis JV. The effects of interruptions on task performance, annoyance, and anxiety in the user interface. In: Hirose M, ed. Human-Computer Interaction—INTERACT 2001 Conference Proceedings. Amsterdam: IOS Press, 2001:593–601 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trafton JG, Altmann EM, Brock DP, et al. Preparing to resume an interrupted task: effects of prospective goal encoding and retrospective rehearsal. Int J Hum Comput Stud 2003;58:583–603 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Byrne MD, Bovair S. A working memory model of a common procedural error. Cogn Sci 1997;21:31–61 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodgetts HM, Jones DM. Interruption of the Tower of London task: Support for a goal-activation approach. J Exp Psychol Gen 2006;135:103–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodgetts HM, Jones DM. Contextual cues aid recovery from interruption: the role of associative activation. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 2006;32:1120–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monk CA, Boehm-Davis DA, Trafton JG. The attentional costs of interrupting task performance at various stages. Bridging Fundamentals and New Opportunities Proceedings of the 46th Annual Meeting of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society; 30 September–4 October 2002, Baltimore, MD. Santa Monica, CA: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 2002:1824–8 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dodhia RM, Dismukes RK. Interruptions create prospective memory tasks. Appl Cogn Psychol 2009;23:73–89 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wickens CD. Multiple resources and performance prediction. Theor Issues Ergon Sci 2002;3:159–77 [Google Scholar]

- 22.McFarlane DC, Latorella KA. The scope and importance of human interruption in human-computer interaction design. Hum Comput Interact 2002;17:1–61 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jett QR, George JM. Work interrupted: a closer look at the role of interruptions in organizational life. Acad Manage Rev 2003;28:494–507 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Interruption.net http://interruptions.net/literature.htm (accessed Aug 2009).

- 25.Horstmann G. Latency and duration of the action interruption in surprise. Cogn Emot 2006;20:242–73 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drugge M, Nilsson M, Liljedahl U, et al. Methods for interrupting a wearable computer user. Proceedings of the Eighth International Symposium on Wearable Computers; 31 October–3 November 2004, Arlington, VA. Los Alamitos, CA: IEEE Computer Society, 2004:150–7 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drugge M, Witt H, Parnes P, et al. Using the ‘HotWire’ to Study Interruptions in Wearable Computing Primary Tasks,. Proceedings of 10th IEEE International Symposium on WearableComputers (ISWC 2006). Los Alamitos: IEEE Computer Society, 2006:37–44 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kreifeldt JG, McCarthy ME. Interruption as a test of the user-computer interface. Proceedings of the 17th Annual Conference on Manual Control (California Institute of Technology, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Publication 81-95). National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), 1981:655–67 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Field G, Spence R. Now, where was I? New Zealand Journal of Computing 1994;5:35–43 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altmann EM, Trafton JG. Task interruption: resumption lag and the role of cues. In: Forbus K, Gentner D, Regier T, eds. Proceedings of the 26th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2004:43–8 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mark G, Gudith D, Klocke U. The Cost of Interrupted Work: More Speed and Stress. Florence, Italy: Association for Computing Machinery, 2008:107–10 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu W. Focusing on desirability: the effect of decision interruption and suspension on preferences. J Consum Res 2008;35:640–52 [Google Scholar]

- 33.LeGoullon MD. Spring ahead or fall back? Exploring the nature of resumption errors. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 50th Annual Meeting; 16–20 October 2006, San Francisco, CA. Santa Monica, CA: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 2006:363–7 Available in CD-ROM Format. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Latorella KA. Investigating interruptions: an example from the flightdeck. Proc of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 40th Annual Meeting. Santa Monica: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 1996:249–53 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newell A, Simon HA. Human Problem Solving. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1972 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kahneman D, Slovic P, Tversky A. Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics an Biases. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gillie T, Broadbent D. What makes interruptions disruptive? A study of length, similarity and complexity. Psychol Res 1989;50:243–50 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adamczyk PD, Bailey BP. If not now, when? the effects of interruption at different moments within task execution. In: Dykstra-Erickson E, Tscheligi M, eds. CHI 2004-CoNNECT Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 24–29 April 2004, Vienna, Austria. New York: ACM Press, 2004:271–8 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Botvinick MM, Bylsma LM. Distraction and action slips in an everyday task: evidence for a dynamic representation of task content. Psychon Bull Rev 2005;12:1011–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beeftink F, Van Eerde W, Rutte CG. The effect of interruptions and breaks on insight and impasses: do you need a break right now? Creat Res J 2008;20:358–64 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hess SM, Detweiler MC. Training to reduce the disruptive effects of interruptions. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 38th Annual Meeting; 1994. Santa Monica: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 1994:1173–7 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hodgetts HM, Jones DM. Interruptions in the tower of London task: can preparation minimise disruption? A Summit for People and Technology Proceedings of the 47th Annual Meeting of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society; 13–17 October 2003, Denver, CO. Santa Monica, CA: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 2003:1000–4 Available in CD-ROM Format. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bailey BP, Konstan JA. On the need for attention-aware systems: measuring effects of interruption on task performance, error rate, and affective state. Comput Human Behav 2006;22:685–708 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Speier C, Valacich JS, Vessey I. The influence of task interruption on individual decision making: an information overload perspective. Decis Sci 1999;30:337–60 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Speier C, Vessey I, Valacich JS. The effects of interruptions, task complexity, and information presentation on computer-supported decision-making performance. Decis Sci 2003;34:771–97 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cades DM, Trafton JG, Boehm-Davis DA, et al. Does the difficulty of an interruption affect our ability to resume? Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 51st Annual Meeting; 1–5 October 2007, Baltimore, MD. Santa Monica, CA: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 2007:234–8 Available in CD-ROM Format. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cades DM, Werner N, Trafton JG, et al. Dealing with interruptions can be complex, but does interruption complexity matter: a mental resources approach to quantifying disruptions. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 52nd Annual Meeting. Santa Monica: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 2008:398–402 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oulasvirta A, Saariluoma P. Surviving task interruptions: investigating the implications of long-term working memory theory. Int J Hum Comput Stud 2006;64:941–61 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zijlstra FRH, Roe RA, Leonova AB, et al. Temporal factors in mental work: effects of interrupted activities. J Occup Organ Psychol 1999;72:163–85 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Edwards MB, Gronlund SD. Task interruption and its effects on memory. Memory 1998;6:665–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weisband SP, Fadel KJ, Mattarelli E. An experiment on the effects of interruptions on individual work trajectories and performance in critical environments. Proceedings of the Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. Los Alamitos: IEEE Computer Society, 2007:138–47 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Monk CA, Boehm-Davis DA, Trafton JG. Recovering from interruptions: implications for driver distraction research. Hum Factors 2004;46:650–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bailey BP, Iqbal ST. Understanding changes in mental workload during execution of goal-directed tasks and its application for interruption management. ACM Trans Comput Hum Interact 2008;14:1–28 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ho CY, Nikolic MI, Sarter NB. Supporting timesharing and interruption management through multimodal information presentation. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 45th Annual Meeting. Santa Monica: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 2001:341–5 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ho CY, Nikolic MI, Waters MJ, et al. Not Now! Supporting interruption management by indicating the modality and urgency of pending tasks. Hum Factors 2004;46:399–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hopp PJ, Smith CAP, Clegg BA, et al. Interruption management: the use of attention-directing tactile cues. Hum Factors 2005;47:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hopp-Levine PJ, Smith CA, Clegg BA, et al. Tactile interruption management: tactile cues as task-switching reminders. Cogn Technol Work 2006;8:137–45 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hameed S, Ferris T, Jayaraman S, et al. Using informative peripheral visual and tactile cues to support task and interruption management. Hum Factors 2009;51:126–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Monk CA, Trafton JG, Boehm-Davis DA. The effect of interruption duration and demand on resuming suspended goals. J Exp Psychol Appl 2008;14:299–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Einstein GO, McDaniel MA, Williford CL, et al. Forgetting of intentions in demanding situations is rapid. J Exp Psychol Appl 2003;9:147–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Van Nimwegen C, Van Oostendorp H. Visual guidance and the impact of interruption during problem solving: interface issues embedded in cognitive load theory. In: Vosniadou S, Kayser D, Protopaps A, eds. EuroCogSci 07 The European Cognitive Science Conference 2007; 23–27 May 2007, Delphi, Greece. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2007:800–5 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oulasvirta A, Saariluoma P. Long-term working memory and interrrupting messages in human-computer interaction. Behav Inf Technol 2004;23:53–64 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ratwani RM, Trafton JG. Spatial memory guides task resumption. Vis cogn 2008;16:1001–10 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bailey BP, Konstan JA, Carlis JV. Measuring the effects of interruptions on task performance in the user interface. IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics 2000: Cybernetics Evolving to Systems, Humans, Organizations, and Their Complex Interactions. Piscataway: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, 2000:757–62 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Czerwinski M, Cutrell E, Horvitz E. Instant messaging: effects of relevance and time. People and Computers XIV: Proceedings of HCI 2000. London: Springer-Verlag, 2000:71–6 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Magrabi F. Using Cognitive Models to Evaluate Safety-Critical Interfaces in Healthcare. CHI '08 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Florence, Italy: ACM, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kieras DE. A guide to GOMS model usability evaluation using NGOMSL. In: Helander M, Landauer T, eds. The Handbook of Human-Computer Interaction. 2nd edn Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Latorella KA. Effects of modality on interrupted flight deck performance: implications for data link. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 42nd Annual Meeting. Santa Monica: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 1998:87–91 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ratwani RM, Andrews AE, Sousk JD, et al. The effect of interruption modality on primary task resumption. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 52nd Annual Meeting: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society. Santa Monica: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 2008:393–7 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hsu KE, Man FY, Gizicki RA, et al. Experienced surgeons can do more than one thing at a time: effect of distraction on performance of a simple laparoscopic and cognitive task by experienced and novice surgeons. Surg Endosc 2008;22:196–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cades DM, Trafton JG, Boehm-Davis DA. Mitigating disruptions: can resuming an interrupted task be trained? Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 50th Annual Meeting; 16–20 October 2006, San Francisco, CA. Santa Monica, CA: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 2006:368–71 Available in CD-ROM Format. [Google Scholar]

- 72.McFarlane DC. Comparison of four primary methods for coordinating the interruption of people in human-computer interaction. Hum Comput Interact 2002;17:63–139 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Carton AM, Aiello JR. Control and anticipation of social interruptions: reduced stress and improved task performance. J Appl Soc Psychol 2009;39:169–85 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gievska S, Sibert J. Using Task Context Variables for Selecting the Best Timing for Interrupting Users. Proceedings of the 2005 Joint Conference on Smart Objects and Ambient Intelligence: Innovative Context-Aware Services: Usages and Technologies. New York: ACM Press, 2005:171–6 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Czerwinski M, Cutrell E, Horvitz E. Instant messaging and interruption: influence of task type on performance. In: Paris C, Ozkan N, Howard S, et al., eds. Proceedings of OZCHI 2000: Interfacing Reality in the New Millennium. Australia: Computer Human Interaction Special Interest Group, 2000:356–61 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.