Abstract

While female protection from cardiovascular diseases declines with the fall in circulating sex hormones experienced during menopause, clinical trials in older women fail to demonstrate beneficial effects for hormone replacement therapy. The recent discovery of GPR30, a membrane-bound estrogen receptor which is structurally and functionally unique from the steroid receptors ERα and ERβ, has unveiled additional signaling pathways by which estrogen may influence cardiovascular health. This review takes an organ-based approach to assess the expression and function of GPR30 in the cardiovascular system. We conclude that while the current literature indeed suggests a cardiovascular role for GPR30, additional exploration is necessary to fully elucidate the estrogenic actions mediated by this novel receptor.

Keywords: GPR30, estrogen receptors, cardiovascular, blood pressure, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease continues to be the leading cause of death for women in the United States.1 Female protection from cardiovascular diseases steeply declines after menopause, suggesting that a decrease in endogenous sex hormones may contribute to cardiovascular mortality in older women. Although “loss of protection” was construed as an argument for the beneficial actions of estrogen, hormone replacement trials in older women well past menopause do not provide strong clinical support. Indeed, large trials such as the Women’s Health Initiative utilizing non-human estrogen (premarin) with or without synthetic progestins (medroxyprogesterone acetate) invariably report a significant increase in the incidence of stroke, heart attack, and dementia.2,3 One issue in these studies is the initiation of estrogen replacement many years following the onset of menopause into the physiological milieu that has adapted to little or no estrogen for many years. Hormone replacement may portend for quite different responses in women with declining but still significant endogenous levels of the hormone and the full complement of estrogen receptors. Indeed, the complex and at times contradictory actions of estrogen may reflect differential activation of estrogen receptors and downstream signaling pathways.

The effects of estrogen binding to its nuclear hormone receptors ERα and ERβ are well-characterized and include receptor translocation to the nucleus to produce genomic actions through transcriptional activation. In 1977, Pietras and Szego discovered that estrogen also binds to a cell surface receptor, introducing the possibility that estrogenic signaling may involve non-transcriptional mechanisms or indirect actions to influence gene expression.4 Although several studies suggest that membrane-bound forms of the classical estrogen receptors exist, the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor GPR30 (or GPER) has been the focus of a surge of studies over the past fifteen years.5 Initial characterization of GPR30 revealed ubiquitous expression of the receptor in human tissues, and subsequent studies discovered a role for this receptor in estrogen-sensitive tumor growth in the absence of ERα/β.6,7 While it is well-established that the non-genomic or acute actions of estrogen such as vasorelaxation and nitric oxide production influence blood pressure, the role of the seven-transmembrane estrogen receptor GPR30 in cardiovascular regulation remains to be determined.

Previous studies from this laboratory and others clearly support an important role for estrogen in the regulation of blood pressure.8–11 In the hypertensive mRen2.Lewis congenic female, removal of circulating estrogen via ovariectomy results in an early and significant increase in blood pressure.8 The exacerbation of hypertension is associated with activation of the ACE-angiotensin II (Ang II)-aldosterone-AT1 receptor axis of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). The mRen2.Lewis congenic strain is an Ang II-dependent model with increased circulating and tissue renin/prorenin that exhibits marked sex differences in the degree of hypertension, cardiac and renal injury, as well as activation of the circulating and tissue RAAS.12 Moreover, chronic 17β-estradiol replacement in the female mRen2.Lewis reverses the increase in blood pressure to the same extent as treatment with the angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptor antagonist olmesartan.8,13 Estradiol treatment also reverses activation of the circulating RAAS in the mRen2.Lewis and increases plasma levels of Ang-(1–7), an alternative product of the RAAS that exhibits vasorelaxant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-fibrotic properties to functionally oppose Ang II-AT1 receptor actions.14 Our recent report shows that chronic treatment with the selective GPR30 agonist G-1 reduces blood pressure in estrogen-depleted mRen2.Lewis females but not male hypertensive littermates, suggesting that this membrane receptor may contribute to the cardiovascular actions of estrogen particularly in a hypertensive setting.15 In lieu of these findings, the current review examines the existing literature for the potential role of GPR30 in mediating the cardiovascular actions of estrogen.

VASCULATURE

The ability of estrogen to induce vasorelaxation has long been considered an important component of its beneficial cardiovascular actions. Sublingual administration of estradiol decreases blood pressure and peripheral vascular resistance in hypertensive postmenopausal women within minutes, and long term hormone replacement enhances the response to vasodilators such as nitric oxide.16–18 In rodents, estradiol elicits dose-dependent relaxation even in arterial rings from ERα and ERβ knockout mice.19–21 In fact, aortic rings from ERβ knockout mice show a greater vasodilatory response to estradiol.22 Similarly, the protective effects of estrogen on vascular injury are evident in both ERα and ERβ knockout mice.23,24 Moreover, estrogenic effects in the vasculature are dependent on GTP binding and independent of protein and RNA synthesis, suggesting activation of a receptor that is distinct from the classical steroid receptors.25,26

In humans, GPR30 gene expression is similar in internal mammary arteries and saphenous veins and is comparable to ERα although 10-fold lower than ERβ.27 In the first cardiovascular characterization of GPR30 knockout mice, Martensson and colleagues localize GPR30 mRNA in second-order mesenteric vessels.28 GPR30 gene deletion revealed a difference in blood pressure (~10 mm Hg) in 9 month-old mice. While there were no changes in media thickness, knockout mice showed a decrease in resistance artery lumen circumference without alterations in the response to nitric oxide or prostacyclin inhibition.28 Haas et al. were the first to demonstrate that the selective GPR30 agonist G-1 acutely lowers pressure in anesthetized normotensive male Sprague-Dawley rats and relaxes pressurized rodent and human vessels.29 In mouse carotid and human internal mammary arteries, G-1 vasorelaxation is significantly greater than estradiol, differentiating the collective effect of estrogen receptor stimulation from selective GPR30 activation.29 Importantly, these authors also show that GPR30 gene deletion attenuates G-1 vasorelaxation, but unfortunately the estradiol response was not assessed in knockout mice.29 Subsequently, we reported that G-1 chronically lowers blood pressure in ovariectomized mRen2.Lewis females, as well as acutely dilates aortic rings through an endothelium-dependent mechanism.15 Vascular GPR30 protein is clearly evident in both endothelial and smooth muscle cells of the aorta, and immunoblots of aortic tissue reveal a single band of approximately 50 kDa that is identical to that in brain.15 Broughton et al. report more intense immunostaining for GPR30 in endothelial versus smooth muscle cells in rat carotid and cerebral arteries and also show that G-1 vasorelaxation is endothelium- and nitric oxide-dependent.30 Similarly, relaxation of epicardial porcine coronary arteries is dependent on both an intact endothelium and nitric oxide production.31

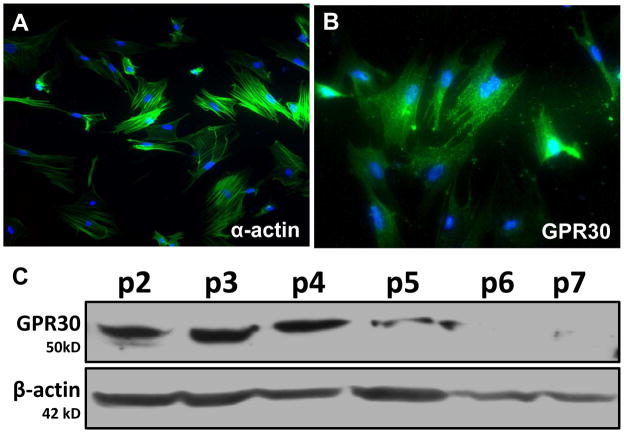

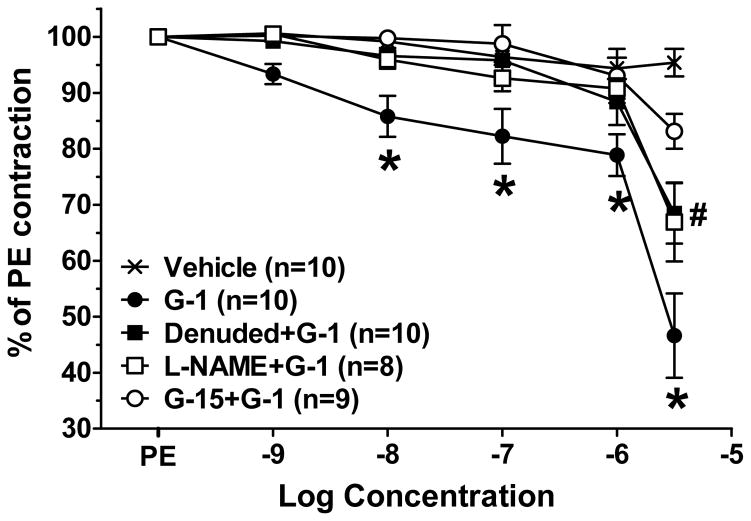

In addition to evidence that the vasodilatory actions of GPR30 occur through activation of endothelial cell receptors, GPR30 is expressed in smooth muscle cells of rat aorta, cerebral, and carotid arteries.15,30,32,33 We and others also detect GPR30 expression in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells, although GPR30 protein significantly declines with increasing passage such that the cellular actions of the receptor may not be apparent after prolonged cell culture (Figure 1).21,29,32–34 While some have shown GPR30-induced increases in MAP kinase signaling and cell proliferation in vascular smooth muscle cells, Haas et al. demonstrate inhibition of serum-stimulated growth by G-1 in vascular smooth muscle cells lacking ERα and ERβ.29,32,33 G-1 also attenuates the fura-2 calcium response to serotonin in human aortic smooth muscle cells, suggesting that GPR30 activation in smooth muscle may influence vascular tone. In isolated mesenteric arteries from intact and ovariectomized mRen2.Lewis females, significant vasodilation to G-1 is evident in both endothelium-denuded vessels and vessels pretreated with L-NAME, indicating a smooth muscle component to the vasodilatory GPR30 response that is independent of nitric oxide (Figure 2).21 We also show that the GPR30 antagonist G15 abolishes the vasorelaxant effects of both G-1 (Figure 2) and estradiol.21 Finally, our recent studies reveal that the vasodilatory responses to G-1 and estradiol in isolated mesenteric vessels are attenuated in intact mRen2.Lewis females maintained on a high salt diet; however, the acetylcholine response is not altered.35 In addition to estrogen-sensitive increases in blood pressure, female mRen2.Lewis exhibit a robust exacerbation in systolic blood pressure (~60 mm Hg) in response to a chronic high salt diet.13,35 The reduced vasodilatory response to GPR30 in resistance vessels may contribute to this sustained salt-dependent increase in blood pressure and may imply an important role for this receptor in salt-sensitive hypertension.

Figure 1.

GPR30 expression in cultured mesenteric smooth muscle cells from an intact mRen2.Lewis female. A, Smooth muscle-specific α-actin (green); Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). B, GPR30 (green; LS-A4272, MBL International, Woburn, MA); DAPI (blue). C, Immunoblot of mesenteric smooth muscle cell lysates (50 μg). Cells were cultured for seven passages, and GPR30 expression was detected at ~50 kD using the same antibody as in immunostaining. β-actin was used as a loading control. Adapted from Lindsey et al.21

Figure 2.

Concentration-dependent relaxation in response to the GPR30 agonist G-1 in isolated mesenteric arteries from intact mRen2.Lewis congenic females. *P < 0.05 G-1 vs. Vehicle and G15+G-1, #P < 0.05 G-1 vs. L-NAME+G-1 and Denuded+G-1. Adapted from Lindsey et al.21

HEART

In comparison to men, women are diagnosed with heart failure later in life and survive longer after diagnosis.36 Women also exhibit diastolic dysfunction rather than the systolic abnormalities typically observed in males, and short-term hormone replacement therapy improves cardiac function in postmenopausal women.37,38 In the mRen2.Lewis congenic rat model, Groban and colleagues demonstrate that ovariectomized females exhibit diastolic dysfunction and cardiac fibrosis in comparison to estrogen-intact littermates.39 Ovariectomy is also detrimental in animal models of chronic volume overload, ischemia-reperfusion, and myocardial infarction, while estrogen replacement provides cardioprotection.40–42 In vitro studies also establish a role for estradiol in reducing both cardiomyocyte apoptosis and cardiofibroblast proliferation.43,44

GPR30 is expressed in both the rodent and human heart, as well as in isolated rat cardiomyocytes.45–47 The GPR30-mediated decrease in contractility in the Langendorff-perfused rat heart is associated with increased phosphorylation of ERK and eNOS.46 In isolated hearts from mice and Sprague Dawley rats exposed to ischemia-reperfusion, G-1 pretreatment reduces infarct size and preserves cardiac function, perhaps through activation of ERK and a reduction in inflammation.45,48,49 ERK signaling also mediates the upregulation of GPR30 induced by hypoxia in cardiac myocytes, which may provide cardioprotection through inhibition of cellular apoptosis in these conditions.50 In the estrogen-replete mRen2.Lewis female, we report increased cardiac GPR30 expression in response to a high salt diet.51 Moreover, chronic treatment with the agonist G-1 attenuates salt-induced diastolic dysfunction and myocyte hypertrophy in the absence of significant changes in blood pressure. While male GPR30 knockout mice exhibit both systolic and diastolic impairments, female mice have normal cardiac function, suggesting that other estrogen receptor subtypes may compensate for the loss of GPR30 in the female heart.52 Although others clearly show the importance of both ERα and ERβ in the acute cardioprotective effects of estrogen, the current evidence suggests a role for GPR30 as well.53–55

KIDNEY

Clinical data from the World Health Organization suggests that salt-sensitive increases in blood pressure are augmented after menopause.56 Schulman and colleagues report that ovariectomy in younger women increases the incidence of salt-dependent hypertension.57 Moreover, chronic transdermal treatment with estradiol blunts the blood pressure response to salt-loading in postmenopausal women.58 Similarly, ovariectomy exacerbates salt-sensitive hypertension in the mRen2.Lewis female rats and other animal models.9,10,13,59,60 It is not known whether estrogen directly alters sodium transport within the kidney or influences other systems such as the cyclooxygenase, nitric oxide, or RAAS that contribute to salt-sensitivity. Estradiol is also renoprotective in renal wrap hypertension, diabetes, and following acute cardiac arrest; however, at least a portion of these protective effects are evident in ER knockout mice or in the presence of the ER antagonist ICI 182,780.61–63

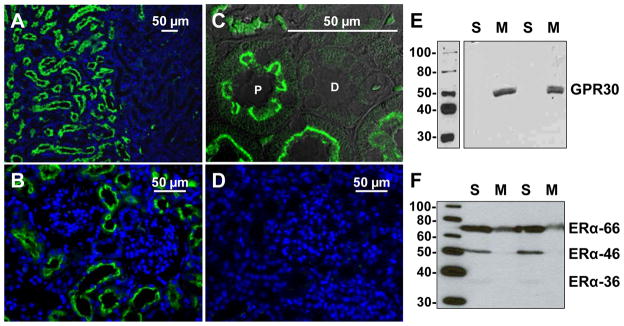

There are few but conflicting studies on GPR30 expression and function within the kidney. In male and female Sprague-Dawley rats, Hazell et al. report GPR30 immunoreactivity and mRNA primarily in the renal pelvis, with less immunostaining in the medulla and variable staining in the cortical region.64 In contrast, Cheng et al. localize GPR30 in the rat renal cortex, primarily on the basolateral surface of proximal tubules, with less staining in the medulla and renal pelvis.65 We demonstrate predominant localization of GPR30 in the renal cortex of mRen2.Lewis female rats, with minimal staining in the medulla.35 As shown in Figure 3, fluorescent GPR30 immunostaining is localized specifically to the brush border of proximal tubules, with no apparent staining in distal tubules or glomeruli. Competition with the antigenic peptide abolishes all cortical immunostaining for GPR30 (Figure 3D). Similar to the results in the heart, a high salt diet significantly increases cortical GPR30 mRNA and protein but does not influence ERα expression. Cortical GPR30 protein is found exclusively in the 100,000 x g membrane fraction (Figure 3E), while ERα is present in the soluble fraction (Figure 3F). In addition, the purported membrane-bound isoform ERα-36 is a minor component in the cytosolic fraction and is undetectable in the membrane fraction of the rat kidney. Given the salt-induced increase in cortical GPR30 expression, we further assessed the effect of chronic treatment with the GPR30 agonist in the intact mRen2.Lewis females fed high salt. Although two-week treatment with G-1 does not reduce the salt-dependent increase in blood pressure, the agonist significantly attenuates proteinuria and oxidative stress within the proximal tubules, consistent with the local epithelial expression of GPR30. Moreover, G-1 reverses the salt-induced downregulation of the protein transporter megalin within the tubules, which may contribute to the reduction in proteinuria through increased uptake and metabolism of filtered proteins. To our knowledge, this is the first study to reveal renoprotective actions of the GPR30 agonist in an experimental model of salt-dependent hypertension. The mechanism for the salt-dependent increase in GPR30 within proximal tubules is not known; however, local increases in oxidative stress may influence receptor expression and serve as a compensatory response to limit tubular injury in the female mRen2.Lewis kidney.

Figure 3.

A, In the kidneys of high salt (HS) fed mRen2 females, fluorescent GPR30 immunostaining (green; LS-A4272, MBL International) was evident in the cortex (left) but not the medulla (right). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). B, Staining in the renal cortex was primarily localized to the luminal surface of proximal tubules, with less staining in glomeruli and distal tubules. C, A higher magnification confocal image confirms GPR30 staining specifically in the brush border of proximal (P) tubules, with no apparent staining in distal (D) tubules. D, Immunostaining was attenuated by preabsorption of the primary antibody with the antigenic peptide. E, A full length immunoblot of kidney cortex homogenates probed for GPR30 (50 kDa) reveals expression in the 100,000 x g membrane fraction (M) but not soluble fraction (S). F, The ERα antibody, which was directed against amino acid residues 247–261 in the DNA binding domain, shows ERα expression in the soluble fraction. ERα-66 and ERα-46 isoforms are predominant, with minimal signal for ERα-36. Adapted from Lindsey et al.35

BRAIN

In comparison to men, premenopausal women have lower circulating catecholamines and ganglionic blockade produces a smaller decrease in pressure.66 After menopause, vagal activity decreases while sympathetic activity increases, and hormone replacement abrogates these changes.67,68 Baroreflex sensitivity changes throughout the menstrual cycle in both humans and rodents, with greater sensitivity in the presence of higher circulating levels of estrogen.67–69 Moreover, microinjection of estradiol into central autonomic nuclei including the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) and rostral ventrolateral medulla improves baroreflex function.70 Hay and colleagues find that central administration of estradiol also blunts Ang II-dependent hypertension in mice, perhaps through a reduction in oxidative stress.71

While multiple studies demonstrate GPR30 localization in brain areas important for cardiovascular function, relatively few assess the functional aspects of central GPR30 receptors. Brailoiu et al. thoroughly characterize GPR30 expression in adult male and female Sprague-Dawley brains and show significant immunostaining in brainstem areas typically associated with cardiovascular function including the paraventricular nucleus (PVN), NTS, the nucleus ambiguous, and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus.72 GPR30 immunostaining exhibits a similar pattern in male and female mice, suggesting that expression in these autonomic areas is conserved among rodent species.64 Central GPR30 expression is also evident in rat spinal cord areas including the nodose and dorsal root ganglia.73 In the NTS, GPR30 immunostaining is predominantly localized to neurons that co-express ERα, while in the PVN GPR30 shows moderate co-localization with nitric oxide synthase.74 In regards to GPR30 function in the central control of the cardiovascular system, Qiao et al. show that ovariectomy reduces while estradiol and G-1 restore membrane excitability of isolated vagal afferent neurons which extend to aortic baroreceptors.75 Despite this potential effect on cardiovascular function, no studies to date ascertain the effects of central administration of GPR30-specific ligands on blood pressure, heart rate, or baroreflex sensitivity.

ESTROGEN AND THE RAAS

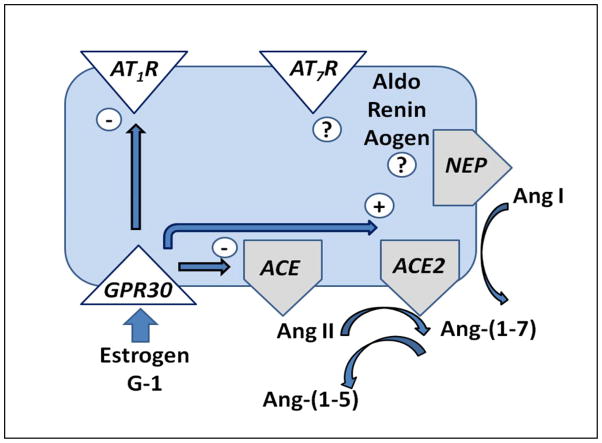

The relationship between estrogen and the RAAS is complex and at times contradictory which may explain the ongoing controversy regarding the beneficial influence of estrogen on the cardiovascular system. In postmenopausal females, hormone replacement therapy stimulates angiotensinogen but suppresses renin.76 Experimental studies reveal that estrogen stimulates the expression of angiotensinogen from the liver and increases renin activity, all of which promote the formation of the vasoconstrictor and pro-inflammatory peptide Ang II.77,78 However, estrogen reduces the expression of ACE and the AT1 receptor subtype and upregulates ACE2, potentially altering the balance of the RAAS to favor the formation and signaling of Ang-(1–7) over that of Ang II.79–81 We previously showed that ACE is the major enzyme for the metabolism of circulating and proximal tubular Ang-(1–7) and that reduced ACE favors the direct processing of Ang I to Ang-(1–7) via endopeptidases such as neprilysin and thimet oligopeptidase.14,82,83 Sandberg and colleagues report that estrogen replacement increases ACE2 expression in the injured kidney, which would promote the processing of Ang II directly to Ang-(1–7).84 Interestingly, the female mRen2.Lewis exhibits 5–10 fold higher expression of neprilysin activity and protein expression in the renal cortex in comparison to male littermates.12 Preliminary data in the brush border fraction of the renal cortex also reveals higher neprilysin in female BL/6 mice in comparison to males.85 Neprilysin may contribute to reduced Ang II content as well through the direct metabolism of the peptide to Ang-(1–4).82 Indeed, we propose that estrogen-dependent regulation of these key processing enzymes within the kidney and other tissues would enhance the ratio of Ang-(1–7) to Ang II (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Proposed scheme for the influence of GPR30 activation on the components of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). Estrogen-dependent activation may reduce expression of the Ang II AT1 receptor (AT1R) and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), but increase expression of ACE2. ACE forms Ang II and metabolizes Ang-(1–7) to the fragment Ang-(1–5) while ACE2 and neprilysin form Ang-(1–7) from Ang II and Ang I, respectively. Alterations in ACE and ACE2 may lead to an increase in the ratio of Ang-(1–7) to Ang II in tissues, leading to a reduction in pressure and/or reduced tissue injury. The actions of GPR30 on other RAAS components including renin, angiotensinogen (Aogen), aldosterone (Aldo), the Ang-(1–7) receptor (AT7R) and neprilysin (NEP) remain to be determined. Adapted from Chappell.14

Although the extent that estrogen receptor subtypes contribute to the regulation of the RAAS components in various tissues has not been thoroughly elucidated, chronic G-1 administration in the estrogen-depleted mRen2.Lewis reduces aortic gene expression of both the AT1 receptor and ACE and increases ACE2 mRNA with no changes in the AT2 receptor or eNOS.15 Experimental studies in a model of brain ischemia reveal ERα-dependent regulation of ACE2 but ERα-independent alterations in AT1 and AT2 receptors, which may reflect an active role for GPR30.86 These data suggest tissue-specific regulation of RAAS components by estrogen through GPR30 and ERα receptors. GPR30 may contribute at least in part to estrogen-dependent regulation of the RAAS, particularly under pathological conditions of hypertension and/or an activated RAAS. Further investigation is clearly required to establish the influence of GPR30 on the various enzyme and receptor components of the RAAS that are expressed in multiple tissues and cell types.

CONCLUSION

The estrogen receptor GPR30 is ubiquitously expressed in various tissue types integral for cardiovascular function; however, relatively little is known about the exact functional role of the receptor regarding the long-term regulation of blood pressure and tissue injury. Perhaps too much emphasis is placed on the acute or non-genomic actions of GPR30 that typically define a G protein-coupled receptor and distinguishes this receptor from the classical nuclear steroid receptors. Indeed, G-protein coupled receptors and their associated signaling pathways clearly contribute to the genomic actions of multiple peptide hormones and transmitters.87 Although it is well appreciated that GPR30 influences vascular reactivity in hypertension and salt-sensitivity, the long-term regulation of RAAS components to differentially influence the ACE-Ang II-AT1 receptor and ACE2/NEP-Ang-(1–7)-AT7 receptor pathways may be of greater importance in the overall influence of estrogenic signaling. Moreover, it is unclear at this point as to the extent that GPR30 may contribute to sex differences in blood pressure and end organ damage in various models of hypertension. We previously showed that chronic GPR30 activation lowers blood pressure in the estrogen-depleted female mRen2.Lewis but did not reduce pressure in the male or intact female congenics despite the fact that RAAS blockade reduces blood pressure to a similar extent in both groups.15 Further studies are required to compare GPR30 expression and signaling pathways in females versus males and determine whether additional endogenous ligands for GPR30 are present in males. Additional studies are also needed to determine GPR30 signaling mechanisms in different cell types and pathologies, since current evidence suggest divergent pathways depending on the model and organ system. We conclude that the cardiovascular role of estrogen is now more complex and far from fully understood with the identification of GPR30. The continued evaluation of this receptor may portend for more selective therapies to emulate the beneficial actions of estrogen in the cardiovascular system.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING

Funding provided by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, NIH (HL56973, HL51952, HL103974), and the American Heart Association (25515E and 3080005) and unrestricted grants from the Unifi Corporation (Greensboro, NC) and the Farley-Hudson Foundation (Jacksonville, NC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Adams RJ, Berry JD, Brown TM, Carnethon MR, Dai S, de SG, Ford ES, Fox CS, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Greenlund KJ, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Ho PM, Howard VJ, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Makuc DM, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McDermott MM, Meigs JB, Moy CS, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Rosamond WD, Sorlie PD, Stafford RS, Turan TN, Turner MB, Wong ND, Wylie-Rosett J. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics--2011 Update: a Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:e18–e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, Jackson RD, Beresford SA, Howard BV, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM, Ockene J. Risks and Benefits of Estrogen Plus Progestin in Healthy Postmenopausal Women: Principal Results From the Women's Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, Bassford T, Beresford SA, Black H, Bonds D, Brunner R, Brzyski R, Caan B, Chlebowski R, Curb D, Gass M, Hays J, Heiss G, Hendrix S, Howard BV, Hsia J, Hubbell A, Jackson R, Johnson KC, Judd H, Kotchen JM, Kuller L, LaCroix AZ, Lane D, Langer RD, Lasser N, Lewis CE, Manson J, Margolis K, Ockene J, O'Sullivan MJ, Phillips L, Prentice RL, Ritenbaugh C, Robbins J, Rossouw JE, Sarto G, Stefanick ML, Van HL, Wactawski-Wende J, Wallace R, Wassertheil-Smoller S. Effects of Conjugated Equine Estrogen in Postmenopausal Women With Hysterectomy: the Women's Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1701–1712. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pietras RJ, Szego CM. Specific Binding Sites for Oestrogen at the Outer Surfaces of Isolated Endometrial Cells. Nature. 1977;265:69–72. doi: 10.1038/265069a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Z, Zhang X, Shen P, Loggie BW, Chang Y, Deuel TF. Identification, Cloning, and Expression of Human Estrogen Receptor-Alpha36, a Novel Variant of Human Estrogen Receptor-Alpha66. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;336:1023–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carmeci C, Thompson DA, Ring HZ, Francke U, Weigel RJ. Identification of a Gene (GPR30) With Homology to the G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Superfamily Associated With Estrogen Receptor Expression in Breast Cancer. Genomics. 1997;45:607–617. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang D, Hu L, Zhang G, Zhang L, Chen C. G Protein-Coupled Receptor 30 in Tumor Development. Endocrine. 2010;38:29–37. doi: 10.1007/s12020-010-9363-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chappell MC, Gallagher PE, Averill DB, Ferrario CM, Brosnihan KB. Estrogen or the AT1 Antagonist Olmesartan Reverses the Development of Profound Hypertension in the Congenic MRen(2). Lewis Rat. Hypertension. 2003;42:781–786. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000085210.66399.A3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crofton JT, Share L. Gonadal Hormones Modulate Deoxycorticosterone-Salt Hypertension in Male and Female Rats. Hypertension. 1997;29:494–499. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.29.1.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison-Bernard LM, Schulman IH, Raij L. Postovariectomy Hypertension Is Linked to Increased Renal AT1 Receptor and Salt Sensitivity. Hypertension. 2003;42:1157–1163. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000102180.13341.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brosnihan KB, Moriguchi A, Nakamoto H, Dean RH, Ganten D, Ferrario CM. Estrogen Augments the Contribution of Nitric Oxide to Blood Pressure Regulation in Transgenic Hypertensive Rats Expressing the Mouse Ren-2 Gene. Am J Hypertens. 1994;7:576–582. doi: 10.1093/ajh/7.7.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pendergrass KD, Westwood BM, Chappell MC. Differential Expression of Neprilysin and Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 May Contribute to the Gender Disparity in the Hypertensive MRen2. Lewis Strain. Hypertension. 2007;50:e75–e155. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chappell MC, Yamaleyeva LM, Westwood BM. Estrogen and Salt Sensitivity in the Female MRen(2). Lewis Rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R1557–R1563. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00051.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chappell MC. Emerging Evidence for a Functional Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2-Angiotensin-(1–7)-MAS Receptor Axis: More Than Regulation of Blood Pressure? Hypertension. 2007;50:596–599. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.076216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindsey SH, Cohen JA, Brosnihan KB, Gallagher PE, Chappell MC. Chronic Treatment With the G Protein-Coupled Receptor 30 Agonist G-1 Decreases Blood Pressure in Ovariectomized MRen2. Lewis Rats. Endocrinology. 2009;150:3753–3758. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pines A, Fisman EZ, Drory Y, Shapira I, Averbuch M, Eckstein N, Motro M, Levo Y, Ayalon D. The Effects of Sublingual Estradiol on Left Ventricular Function at Rest and Exercise in Postmenopausal Women: an Echocardiographic Assessment. Menopause. 1998;5:79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leonardo F, Medeirus C, Rosano GM, Pereira WI, Sheiban I, Gebara O, Bellotti G, Pileggi F, Chierchia SL. Effect of Acute Administration of Estradiol 17 Beta on Aortic Blood Flow in Menopausal Women. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:791–793. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00520-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perera M, Petrie JR, Hillier C, Small M, Sattar N, Connell JM, Lumsden MA. Hormone Replacement Therapy Can Augment Vascular Relaxation in Post-Menopausal Women With Type 2 Diabetes. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:497–502. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.2.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cruz MN, Douglas G, Gustafsson JA, Poston L, Kublickiene K. Dilatory Responses to Estrogenic Compounds in Small Femoral Arteries of Male and Female Estrogen Receptor-Beta Knockout Mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H823–H829. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00815.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubanyi GM, Freay AD, Kauser K, Sukovich D, Burton G, Lubahn DB, Couse JF, Curtis SW, Korach KS. Vascular Estrogen Receptors and Endothelium-Derived Nitric Oxide Production in the Mouse Aorta. Gender Difference and Effect of Estrogen Receptor Gene Disruption. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2429–2437. doi: 10.1172/JCI119426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindsey SH, Carver KA, Prossnitz ER, Chappell MC. Vasodilation in Response to the GPR30 Agonist G-1 Is Not Different From Estradiol in the MRen2. Lewis Female Rat. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2011;57:598–603. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3182135f1c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nilsson BO, Ekblad E, Heine T, Gustafsson JA. Increased Magnitude of Relaxation to Oestrogen in Aorta From Oestrogen Receptor Beta Knock-Out Mice. J Endocrinol. 2000;166:R5–R9. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.166r005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iafrati MD, Karas RH, Aronovitz M, Kim S, Sullivan TR, Jr, Lubahn DB, O'Donnell TF, Jr, Korach KS, Mendelsohn ME. Estrogen Inhibits the Vascular Injury Response in Estrogen Receptor Alpha-Deficient Mice. Nat Med. 1997;3:545–548. doi: 10.1038/nm0597-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karas RH, Hodgin JB, Kwoun M, Krege JH, Aronovitz M, Mackey W, Gustafsson JA, Korach KS, Smithies O, Mendelsohn ME. Estrogen Inhibits the Vascular Injury Response in Estrogen Receptor Beta-Deficient Female Mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:15133–15136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogata R, Inoue Y, Nakano H, Ito Y, Kitamura K. Oestradiol-Induced Relaxation of Rabbit Basilar Artery by Inhibition of Voltage-Dependent Ca Channels Through GTP-Binding Protein. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;117:351–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kitazawa T, Hamada E, Kitazawa K, Gaznabi AK. Non-Genomic Mechanism of 17 Beta-Oestradiol-Induced Inhibition of Contraction in Mammalian Vascular Smooth Muscle. J Physiol. 1997;499 ( Pt 2):497–511. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haas E, Meyer MR, Schurr U, Bhattacharya I, Minotti R, Nguyen HH, Heigl A, Lachat M, Genoni M, Barton M. Differential Effects of 17beta-Estradiol on Function and Expression of Estrogen Receptor Alpha, Estrogen Receptor Beta, and GPR30 in Arteries and Veins of Patients With Atherosclerosis. Hypertension. 2007;49:1358–1363. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.089995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martensson UE, Salehi SA, Windahl S, Gomez MF, Sward K, szkiewicz-Nilsson J, Wendt A, Andersson N, Hellstrand P, Grande PO, Owman C, Rosen CJ, Adamo ML, Lundquist I, Rorsman P, Nilsson BO, Ohlsson C, Olde B, Leeb-Lundberg LM. Deletion of the G Protein-Coupled Receptor GPR30 Impairs Glucose Tolerance, Reduces Bone Growth, Increases Blood Pressure, and Eliminates Estradiol-Stimulated Insulin Release in Female Mice. Endocrinology. 2008;150:687–98. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haas E, Bhattacharya I, Brailoiu E, Damjanovic M, Brailoiu GC, Gao X, Mueller-Guerre L, Marjon NA, Gut A, Minotti R, Meyer MR, Amann K, Ammann E, Perez-Dominguez A, Genoni M, Clegg DJ, Dun NJ, Resta TC, Prossnitz ER, Barton M. Regulatory Role of G Protein-Coupled Estrogen Receptor for Vascular Function and Obesity. Circ Res. 2009;104:288–291. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.190892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Broughton BR, Miller AA, Sobey CG. Endothelium-Dependent Relaxation by G Protein-Coupled Receptor 30 Agonists in Rat Carotid Arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H1055–H1061. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00878.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer MR, Baretella O, Prossnitz ER, Barton M. Dilation of Epicardial Coronary Arteries by the G Protein-Coupled Estrogen Receptor Agonists G-1 and ICI 182,780. Pharmacology. 2010;86:58–64. doi: 10.1159/000315497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ding Q, Gros R, Limbird LE, Chorazyczewski J, Feldman RD. Estradiol-Mediated ERK Phosphorylation and Apoptosis in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Requires GPR 30. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C1178–C1187. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00185.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gros R, Ding Q, Sklar LA, Prossnitz EE, Arterburn JB, Chorazyczewski J, Feldman RD. GPR30 Expression Is Required for the Mineralocorticoid Receptor-Independent Rapid Vascular Effects of Aldosterone. Hypertension. 2011;57:442–451. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.161653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma Y, Qiao X, Falone AE, Reslan OM, Sheppard SJ, Khalil RA. Gender-Specific Reduction in Contraction Is Associated With Increased Estrogen Receptor Expression in Single Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells of Female Rat. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2010;26:457–470. doi: 10.1159/000320569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindsey SH, Yamaleyeva LM, Brosnihan KB, Gallagher PE, Chappell MC. Estrogen Receptor GPR30 Reduces Oxidative Stress and Proteinuria in the Salt-Sensitive Female MRen2. Lewis Rat. Hypertension. 2011;58:665–671. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.175174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ho KK, Anderson KM, Kannel WB, Grossman W, Levy D. Survival After the Onset of Congestive Heart Failure in Framingham Heart Study Subjects. Circulation. 1993;88:107–115. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masoudi FA, Havranek EP, Smith G, Fish RH, Steiner JF, Ordin DL, Krumholz HM. Gender, Age, and Heart Failure With Preserved Left Ventricular Systolic Function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:217–223. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02696-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sites CK, Tischler MD, Blackman JA, Niggel J, Fairbank JT, O'Connell M, Ashikaga T. Effect of Short-Term Hormone Replacement Therapy on Left Ventricular Mass and Contractile Function. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00398-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Groban L, Yamaleyeva LM, Westwood BM, Houle TT, Lin M, Kitzman DW, Chappell MC. Progressive Diastolic Dysfunction in the Female MRen(2). Lewis Rat: Influence of Salt and Ovarian Hormones. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:3–11. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brower GL, Gardner JD, Janicki JS. Gender Mediated Cardiac Protection From Adverse Ventricular Remodeling Is Abolished by Ovariectomy. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;251:89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kolodgie FD, Farb A, Litovsky SH, Narula J, Jeffers LA, Lee SJ, Virmani R. Myocardial Protection of Contractile Function After Global Ischemia by Physiologic Estrogen Replacement in the Ovariectomized Rat. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:2403–2414. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cavasin MA, Sankey SS, Yu AL, Menon S, Yang XP. Estrogen and Testosterone Have Opposing Effects on Chronic Cardiac Remodeling and Function in Mice With Myocardial Infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H1560–H1569. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01087.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patten RD, Pourati I, Aronovitz MJ, Baur J, Celestin F, Chen X, Michael A, Haq S, Nuedling S, Grohe C, Force T, Mendelsohn ME, Karas RH. 17beta-Estradiol Reduces Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis in Vivo and in Vitro Via Activation of Phospho-Inositide-3 Kinase/Akt Signaling. Circ Res. 2004;95:692–699. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000144126.57786.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dubey RK, Gillespie DG, Jackson EK, Keller PJ. 17Beta-Estradiol, Its Metabolites, and Progesterone Inhibit Cardiac Fibroblast Growth. Hypertension. 1998;31:522–528. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.1.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deschamps AM, Murphy E. Activation of a Novel Estrogen Receptor, GPER, Is Cardioprotective in Male and Female Rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1806–H1813. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00283.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Filice E, Recchia AG, Pellegrino D, Angelone T, Maggiolini M, Cerra MC. A New Membrane G Protein-Coupled Receptor (GPR30) Is Involved in the Cardiac Effects of 17beta-Estradiol in the Male Rat. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;60:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patel VH, Chen J, Ramanjaneya M, Karteris E, Zachariades E, Thomas P, Been M, Randeva HS. G-Protein Coupled Estrogen Receptor 1 Expression in Rat and Human Heart: Protective Role During Ischaemic Stress. Int J Mol Med. 2010;26:193–199. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weil BR, Manukyan MC, Herrmann JL, Wang Y, Abarbanell AM, Poynter JA, Meldrum DR. Signaling Via GPR30 Protects the Myocardium From Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Surgery. 2010;148:436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bopassa JC, Eghbali M, Toro L, Stefani E. A Novel Estrogen Receptor GPER Inhibits Mitochondria Permeability Transition Pore Opening and Protects the Heart Against Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H16–H23. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00588.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Recchia AG, De Francesco EM, Vivacqua A, Sisci D, Panno ML, Ando S, Maggiolini M. The G Protein-Coupled Receptor 30 Is Up-Regulated by Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1alpha (HIF-1alpha) in Breast Cancer Cells and Cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:10773–10782. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.172247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jessup JA, Lindsey SH, Wang H, Chappell MC, Groban L. Attenuation of Salt-Induced Cardiac Remodeling and Diastolic Dysfunction by the GPER Agonist G-1 in Female MRen2. Lewis Rats. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Delbeck M, Golz S, Vonk R, Janssen W, Hucho T, Isensee J, Schafer S, Otto C. Impaired Left-Ventricular Cardiac Function in Male GPR30-Deficient Mice. Mol Med Report. 2011;4:37–40. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2010.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Booth EA, Obeid NR, Lucchesi BR. Activation of Estrogen Receptor-Alpha Protects the in Vivo Rabbit Heart From Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H2039–H2047. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00479.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fliegner D, Schubert C, Penkalla A, Witt H, Kararigas G, Dworatzek E, Staub E, Martus P, Ruiz NP, Kintscher U, Gustafsson JA, Regitz-Zagrosek V. Female Sex and Estrogen Receptor-Beta Attenuate Cardiac Remodeling and Apoptosis in Pressure Overload. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R1597–R1606. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00825.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Skavdahl M, Steenbergen C, Clark J, Myers P, Demianenko T, Mao L, Rockman HA, Korach KS, Murphy E. Estrogen Receptor-Beta Mediates Male-Female Differences in the Development of Pressure Overload Hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H469–H476. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00723.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamori Y, Liu L, Ikeda K, Mizushima S, Nara Y, Simpson FO. Different Associations of Blood Pressure With 24-Hour Urinary Sodium Excretion Among Pre- and Post-Menopausal Women. WHO Cardiovascular Diseases and Alimentary Comparison (WHO-CARDIAC) Study. J Hypertens. 2001;19:535–538. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200103001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schulman IH, Aranda P, Raij L, Veronesi M, Aranda FJ, Martin R. Surgical Menopause Increases Salt Sensitivity of Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2006;47:1168–1174. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000218857.67880.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scuteri A, Lakatta EG, Anderson DE, Fleg JL. Transdermal 17 Beta-Oestradiol Reduces Salt Sensitivity of Blood Pressure in Postmenopausal Women. J Hypertens. 2003;21:2419–2420. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200312000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cohen JA, Lindsey SH, Pirro NT, Brosnihan KB, Gallagher PE, Chappell MC. Influence of Estrogen Depletion and Salt Loading on Renal Angiotensinogen Expression in the MRen(2). Lewis Strain. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;299:F35–F42. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00138.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zheng W, Ji H, Maric C, Wu X, Sandberg K. Effect of Dietary Sodium on Estrogen Regulation of Blood Pressure in Dahl Salt-Sensitive Rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H1508–H1513. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01322.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mankhey RW, Bhatti F, Maric C. 17beta-Estradiol Replacement Improves Renal Function and Pathology Associated With Diabetic Nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F399–F405. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00195.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hutchens MP, Nakano T, Kosaka Y, Dunlap J, Zhang W, Herson PS, Murphy SJ, Anderson S, Hurn PD. Estrogen Is Renoprotective Via a Nonreceptor-Dependent Mechanism After Cardiac Arrest in Vivo. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:395–405. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181c98da9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ji H, Menini S, Mok K, Zheng W, Pesce C, Kim J, Mulroney S, Sandberg K. Gonadal Steroid Regulation of Renal Injury in Renal Wrap Hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F513–F520. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00032.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hazell GG, Yao ST, Roper JA, Prossnitz ER, O'Carroll AM, Lolait SJ. Localisation of GPR30, a Novel G Protein-Coupled Oestrogen Receptor, Suggests Multiple Functions in Rodent Brain and Peripheral Tissues. J Endocrinol. 2009;202:223–236. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheng SB, Graeber CT, Quinn JA, Filardo EJ. Retrograde Transport of the Transmembrane Estrogen Receptor, G-Protein-Coupled-Receptor-30 (GPR30/GPER) From the Plasma Membrane Towards the Nucleus. Steroids. 2011;76:892–896. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Christou DD, Jones PP, Jordan J, Diedrich A, Robertson D, Seals DR. Women Have Lower Tonic Autonomic Support of Arterial Blood Pressure and Less Effective Baroreflex Buffering Than Men. Circulation. 2005;111:494–498. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153864.24034.A6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hirshoren N, Tzoran I, Makrienko I, Edoute Y, Plawner MM, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Jacob G. Menstrual Cycle Effects on the Neurohumoral and Autonomic Nervous Systems Regulating the Cardiovascular System. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1569–1575. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.4.8406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Minson CT, Halliwill JR, Young TM, Joyner MJ. Influence of the Menstrual Cycle on Sympathetic Activity, Baroreflex Sensitivity, and Vascular Transduction in Young Women. Circulation. 2000;101:862–868. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.8.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goldman RK, Azar AS, Mulvaney JM, Hinojosa-Laborde C, Haywood JR, Brooks VL. Baroreflex Sensitivity Varies During the Rat Estrous Cycle: Role of Gonadal Steroids. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R1419–R1426. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.91030.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Saleh MC, Connell BJ, Saleh TM. Autonomic and Cardiovascular Reflex Responses to Central Estrogen Injection in Ovariectomized Female Rats. Brain Res. 2000;879:105–114. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02757-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xue B, Zhao Y, Johnson AK, Hay M. Central Estrogen Inhibition of Angiotensin II-Induced Hypertension in Male Mice and the Role of Reactive Oxygen Species. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H1025–H1032. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00021.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brailoiu E, Dun SL, Brailoiu GC, Mizuo K, Sklar LA, Oprea TI, Prossnitz ER, Dun NJ. Distribution and Characterization of Estrogen Receptor G Protein-Coupled Receptor 30 in the Rat Central Nervous System. J Endocrinol. 2007;193:311–321. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dun SL, Brailoiu GC, Gao X, Brailoiu E, Arterburn JB, Prossnitz ER, Oprea TI, Dun NJ. Expression of Estrogen Receptor GPR30 in the Rat Spinal Cord and in Autonomic and Sensory Ganglia. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:1610–1619. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Spary EJ, Maqbool A, Batten TF. Oestrogen Receptors in the Central Nervous System and Evidence for Their Role in the Control of Cardiovascular Function. J Chem Neuroanat. 2009;38:185–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Qiao GF, Li BY, Lu YJ, Fu YL, Schild JH. 17Beta-Estradiol Restores Excitability of a Sexually Dimorphic Subset of Myelinated Vagal Afferents in Ovariectomized Rats. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C654–C664. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00059.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schunkert H, Danser AH, Hense HW, Derkx FH, Kurzinger S, Riegger GA. Effects of Estrogen Replacement Therapy on the Renin-Angiotensin System in Postmenopausal Women. Circulation. 1997;95:39–45. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brosnihan KB, Weddle D, Anthony MS, Heise C, Li P, Ferrario CM. Effects of Chronic Hormone Replacement on the Renin-Angiotensin System in Cynomolgus Monkeys. J Hypertens. 1997;15:719–726. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715070-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Klett C, Ganten D, Hellmann W, Kaling M, Ryffel GU, Weimar-Ehl T, Hackenthal E. Regulation of Hepatic Angiotensinogen Synthesis and Secretion by Steroid Hormones. Endocrinology. 1992;130:3660–3668. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.6.1597163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gallagher PE, Li P, Lenhart JR, Chappell MC, Brosnihan KB. Estrogen Regulation of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme MRNA. Hypertension. 1999;33:323–328. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nickenig G, Baumer AT, Grohe C, Kahlert S, Strehlow K, Rosenkranz S, Stablein A, Beckers F, Smits JF, Daemen MJ, Vetter H, Bohm M. Estrogen Modulates AT1 Receptor Gene Expression in Vitro and in Vivo. Circulation. 1998;97:2197–2201. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.22.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brosnihan KB, Hodgin JB, Smithies O, Maeda N, Gallagher P. Tissue-Specific Regulation of ACE/ACE2 and AT1/AT2 Receptor Gene Expression by Oestrogen in Apolipoprotein E/Oestrogen Receptor-Alpha Knock-Out Mice. Exp Physiol. 2008;93:658–664. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.041806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Allred AJ, Diz DI, Ferrario CM, Chappell MC. Pathways for Angiotensin-(1–7) Metabolism in Pulmonary and Renal Tissues. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;279:F841–F850. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.5.F841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yamada K, Iyer SN, Chappell MC, Ganten D, Ferrario CM. Converting Enzyme Determines Plasma Clearance of Angiotensin-(1–7) Hypertension. 1998;32:496–502. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.3.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ji H, Menini S, Zheng W, Pesce C, Wu X, Sandberg K. Role of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 and Angiotensin(1–7) in 17beta-Oestradiol Regulation of Renal Pathology in Renal Wrap Hypertension in Rats. Exp Physiol. 2008;93:648–657. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.041392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Muller C, Shewale S, Gurley SB, Brosnihan KB, Pirro NT, Fiorino P, Chappell MC. Sex and Species Differences in ACE, ACE2 and Neprilysin of the Renal Brush Border [Abstract] Hypertension. 2011 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shimada K, Kitazato KT, Kinouchi T, Yagi K, Tada Y, Satomi J, Kageji T, Nagahiro S. Activation of Estrogen Receptor-Alpha and of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 Suppresses Ischemic Brain Damage in Oophorectomized Rats. Hypertension. 2011;57:1161–1166. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.167650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gobeil F, Fortier A, Zhu T, Bossolasco M, Leduc M, Grandbois M, Heveker N, Bkaily G, Chemtob S, Barbaz D. G-Protein-Coupled Receptors Signalling at the Cell Nucleus: an Emerging Paradigm. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;84:287–297. doi: 10.1139/y05-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]