Non-technical summary

Circulating angiogenic cells (CACs) repair and maintain the vascular endothelium. CACs are responsive to lifestyle factors such as diet and physical activity. For example, their capacity to regenerate the endothelium is impaired in cardiovascular disease patients, whereas exercise training can improve CAC function. In this study, we examined the effects of a high-fat meal with and without prior endurance exercise on several molecular aspects of CAC function, including levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), nitric oxide (NO), intracellular lipids, and gene expression. Our results indicated that the high-fat meal induced significant oxidative stress (i.e. ROS production) in the CACs that expressed the cell surface protein CD31. However, when subjects performed a single bout of exercise on the prior day, the meal had no effect on ROS in CD31+ cells. Therefore, we concluded that prior exercise prevents the oxidative stress induced by a high-fat meal in CD31+ CACs.

Abstract

Abstract

We hypothesized that prior exercise would prevent postprandial lipaemia (PPL)-induced increases in intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) in three distinct circulating angiogenic cell (CAC) subpopulations. CD34+, CD31+/CD14−/CD34−, and CD31+/CD14+/CD34− CACs were isolated from blood samples obtained from 10 healthy men before and 4 h after ingesting a high fat meal with or without ∼50 min of prior endurance exercise. Significant PPL-induced increases in ROS production in both sets of CD31+ cells were abolished by prior exercise. Experimental ex vivo inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity and mitochondrial ROS production indicated that mitochondria were the primary source of PPL-induced oxidative stress. The attenuated increases in ROS with prior exercise were associated with increased antioxidant gene expression in CD31+/CD14−/CD34− cells and reduced intracellular lipid uptake in CD31+/CD14+/CD34− cells. These findings were associated with systemic cardiovascular benefits of exercise, as serum triglyceride, oxidized low density lipoprotein-cholesterol, and plasma endothelial microparticle concentrations were lower in the prior exercise trial than the control trial. In conclusion, prior exercise completely prevents PPL-induced increases in ROS in CD31+/CD14−/CD34− and CD31+/CD14+/CD34− cells. The mechanisms underlying the effects of exercise on CAC function appear to vary among specific CAC types.

Introduction

Ingestion of a high-fat meal increases serum triglyceride concentrations (TG), induces systemic oxidative stress, and impairs vascular endothelial function (Vogel et al. 1997; Tushuizen et al. 2006). As the majority of individuals in Western society are in a postprandial state most of the time (Sies et al. 2005), routine exposure to postprandial lipaemia (PPL) and the associated endothelial dysfunction may affect the development of cardiovascular (CV) disease (Anderson et al. 2001). PPL-induced vascular endothelial dysfunction is thought to be mediated by oxidative stress resulting from an increased lipid load within the cell, in turn leading to increased oxidative metabolism and excess production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Bae et al. 2001; Wallace et al. 2010). The primary consequences of increased ROS production are nitric oxide (NO) scavenging and uncoupling of the endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) enzyme (Pacher et al. 2007), ultimately resulting in reduced NO bioavailability, impaired NO-dependent vasodilatory function, and, with chronic exposure, a pro-atherogenic cellular environment within the vessel wall (Wallace et al. 2010).

Prior exercise effectively reduces PPL (Petitt & Cureton, 2003; Wallace et al. 2010) and the accompanying endothelial dysfunction (Padilla et al. 2006; Tyldum et al. 2009). The mechanisms underlying the protective effects of exercise involve up-regulation of systemic (Tyldum et al. 2009) and intracellular (Bae et al. 2001; Brownlee, 2005; Wallace et al. 2010) antioxidant defences that enable the preservation of NO bioavailability and vascular function in the face of a high-fat challenge. However, it is unknown whether these mechanisms are uniform among all CV cells and tissues.

Circulating angiogenic cells (CACs) are important for the maintenance of a healthy endothelium. CAC number is associated with CV disease incidence and risk factors, such as obesity, physical inactivity and diabetes (Thijssen et al. 2006; Fadini et al. 2007, 2009; MacEneaney et al. 2009; Witkowski et al. 2010). However, there are few published data on the functional responses of CACs to lifestyle factors. The CAC populations that have received the most attention are bone marrow-derived CD34+ progenitor cells that co-express endothelial markers (Asahara et al. 1997, 1999). There is also evidence that cells expressing the endothelial antigen CD31 (Crosby et al. 2000; Kim et al. 2010a,b) and/or the monocyte antigen CD14 (Fernandez Pujol et al. 2000; Harraz et al. 2001; Schatteman & Awad, 2003; Romagnani et al. 2005; Awad et al. 2006; Mayer et al. 2010) represent important CAC subpopulations. However, the effects of exercise and other lifestyle factors on functional aspects of these cell populations have not been studied. Finally, several studies have shown that PPL causes inflammation and ROS production in leukocytes (Hyson et al. 2002; Alipour et al. 2008; Gower et al. 2011; Varela et al. 2011), but whether these effects are uniform among leukocyte subsets (including CACs) or could be attenuated by exercise is not known.

In the present study, we tested the effect of a high fat meal with or without a bout of prior endurance exercise on ROS and NO production in CD34+, CD31+/CD14−/CD34−, and CD31+/CD14+/CD34− CACs. We also attempted to gain mechanistic insight into the molecular source of PPL-induced ROS using pharmacological inhibition of NADPH oxidase and mitochondrial oxidative activity. We hypothesized that PPL would reduce intracellular NO levels and increase the production of ROS by NADPH oxidase and/or mitochondria, and that these effects would be attenuated by a single bout of exercise performed on the prior day. We also assessed concentrations of serum TG, serum oxidized LDL-cholesterol (OxLDL), and plasma endothelial microparticles (EMPs) to determine if exercise reduces systemic PPL-induced oxidative stress and endothelial damage in conjunction with any effects on CACs.

Methods

Screening

Ten healthy, non-smoking, recreationally to highly active (endurance exercise ≥4 h week−1) men aged 18–35 years with no history of CV or metabolic disease were recruited for this study. Potential subjects were initially screened by telephone or email, and reported to the laboratory following an overnight fast for a screening visit to verify eligibility. Exclusion criteria were as follows: systolic blood pressure ≥130 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, serum total cholesterol ≥200 mg dl−1; low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol ≥130 mg dl−1; high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol ≤35 mg dl−1; fasting glucose ≥100 mg dl−1). The University of Maryland College Park Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures and the subjects provided written informed consent.

A screening blood sample was obtained for assessment of fasting serum TG, lipoprotein lipids, and glucose (Quest Diagnostics, Baltimore, MD, USA). Height, weight, and body mass index were measured, and body composition was assessed using the seven-site skinfold procedure (Jackson & Pollock, 1978). Maximal oxygen uptake ( ) was determined using a stationary cycling test to exhaustion (Life Cycle, Schiller Park, IL, USA). Subjects began cycling at 200 W, and the work rate increased by 25 W every 2 min until the subject was unable to maintain a cadence of ≥50 revolutions min−1.

) was determined using a stationary cycling test to exhaustion (Life Cycle, Schiller Park, IL, USA). Subjects began cycling at 200 W, and the work rate increased by 25 W every 2 min until the subject was unable to maintain a cadence of ≥50 revolutions min−1.  was measured continuously via an automated indirect calorimetry system (Oxycon Pro; Carefusion Respiratory Care, Yorba Linda, CA, USA). All subjects achieved a valid

was measured continuously via an automated indirect calorimetry system (Oxycon Pro; Carefusion Respiratory Care, Yorba Linda, CA, USA). All subjects achieved a valid  as indicated by the plateau criteria (≤200 ml min−1 increase in

as indicated by the plateau criteria (≤200 ml min−1 increase in  with increase in work rate).

with increase in work rate).

Experimental protocol

For the prior exercise trial, subjects reported to the laboratory at 15.00 h, and performed stationary cycling at 70% of  until a total energy expenditure of 2.5 MJ (598 kcal) was reached. This exercise protocol was chosen because exercise of this intensity and energy expenditure have been shown to consistently reduce PPL in response to high fat meals (Petitt & Cureton, 2003). Exercise intensity was verified by measurement of

until a total energy expenditure of 2.5 MJ (598 kcal) was reached. This exercise protocol was chosen because exercise of this intensity and energy expenditure have been shown to consistently reduce PPL in response to high fat meals (Petitt & Cureton, 2003). Exercise intensity was verified by measurement of  via indirect calorimetry every 10 min during exercise. The exact work rate and duration of exercise for each subject are presented in Table 1. For the control trial without prior exercise, subjects remained sedentary for the 24 h prior to the PPL test. Subjects were instructed to maintain the same dietary habits for 72 h preceding each PPL test, which was verified by dietary logs.

via indirect calorimetry every 10 min during exercise. The exact work rate and duration of exercise for each subject are presented in Table 1. For the control trial without prior exercise, subjects remained sedentary for the 24 h prior to the PPL test. Subjects were instructed to maintain the same dietary habits for 72 h preceding each PPL test, which was verified by dietary logs.

Table 1.

Duration of submaximal exercise at 70%

| Subject no. | Body mass (kg) |

(ml kg−1 min−1) (ml kg−1 min−1) |

70% (ml kg−1 min−1) (ml kg−1 min−1) |

70% (l min−1) (l min−1) |

Work rate (W)* | Duration (min)** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 78.4 | 50.0 | 35.0 | 2.74 | 203 | 43.5 |

| 02 | 63.4 | 61.1 | 42.8 | 2.71 | 210 | 44.1 |

| 03 | 72.6 | 54.5 | 38.2 | 2.77 | 209 | 43.2 |

| 04 | 97.0 | 50.5 | 35.4 | 3.43 | 255 | 34.9 |

| 05 | 64.0 | 42.1 | 29.5 | 1.89 | 133 | 63.3 |

| 06 | 87.5 | 52.2 | 36.5 | 3.20 | 239 | 37.4 |

| 07 | 83.2 | 47.0 | 32.9 | 2.74 | 199 | 43.7 |

| 08 | 87.5 | 41.6 | 29.1 | 2.55 | 179 | 46.9 |

| 09 | 81.1 | 42.0 | 29.4 | 2.38 | 168 | 50.1 |

| 10 | 68.6 | 38.9 | 27.2 | 1.87 | 129 | 63.9 |

| Mean | 78.3 | 48.0 | 33.6 | 2.6 | 193 | 47.1 |

| SD | 11.1 | 7.0 | 4.9 | 0.5 | 41 | 9.7 |

| SEM | 3.5 | 2.2 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 13 | 3.1 |

Calculated using the American College of Sports Medicine formula for gross  during cycle ergometry (American College of Sports Medicine, 2000):

during cycle ergometry (American College of Sports Medicine, 2000):  (ml kg−1 min−1) = watts/Mass × 10.8 + 7.

(ml kg−1 min−1) = watts/Mass × 10.8 + 7.

Computed time to reach an energy expenditure of 2.5 MJ (598 kcal) using assumption that 1 litre O2 consumed = 5 kcal energy expended.

Because the effect of exercise on PPL is influenced by the timing, caloric content and composition of meals ingested following exercise (Harrison et al. 2009), participants consumed a meal of fixed macronutrient composition (40% carbohydrate, 30% fat and 30% protein) between 19.00 and 20.00 h, as described previously (Singhal et al. 2009). This meal consisted of commercially available Zone Perfect bars (Abbott Nutrition, Columbus, OH, USA). The number of bars eaten by each participant was calculated and portioned by weight to provide 0.5 g of carbohydrate (kg BW)−1 and 20.9 kJ (kg BW)−1. Subjects were asked to sleep for at least 8 h prior to PPL testing.

PPL tests began at 06.00 h on the morning following each treatment and were performed as described by our laboratory previously (Weiss et al. 2007). The test meal contained heavy whipping cream, sugar, chocolate syrup and non-fat powdered milk. The size of the test meal was normalized to each subject's body surface area (386 g per 2 m2 body surface area). A 386 g serving of the meal provided 1362 kcal (84% fat). All subjects consumed their test meals within 5 min and the meals were well tolerated. Blood samples of 30 ml (K2EDTA Vacutainer Tubes, Becton Dickinson) were obtained at baseline (0 min) and 240 min for isolation of CD34+, CD31+/CD14−/CD34−, and CD31+/CD14+/CD34− CACs. Plasma and serum samples were obtained before the meal and at 1, 2, 3, and 4 h postprandial for assessment of serum triglyceride and oxidized LDL (OxLDL) concentrations and plasma endothelial microparticle (EMP) concentrations.

Immunomagnetic cell separation

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from 0 and 4 h samples using density gradient centrifugation (Ficoll, GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). The CD34+, CD31+/CD14−/CD34− and CD31+/CD14+/CD34− fractions were purified using multiple rounds of immunomagnetic cell separation according to the manufacturer's instructions (EasySep Immunomagnetic Cell Separation Kits, Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada). The different surface antigen combinations were chosen on the basis of previous research indicating the involvement of stem/progenitor (i.e. CD34+), monocytic (i.e. CD14+), and/or endothelial antigen-expressing (i.e. CD31+) PBMC subsets originating from bone marrow or the vessel wall in the maintenance and repair of the vascular endothelium (Crosby et al. 2000; Dimmeler et al. 2001; Harraz et al. 2001; Schatteman & Awad, 2003; Sivan-Loukianova et al. 2003; Romagnani et al. 2005; Awad et al. 2006; Kim et al. 2010a,b). The validity of the CD34+ PBMC immunomagnetic selection procedure has been previously confirmed in our laboratory (Jenkins et al. 2011). For validation of the CD14 and CD31 selection procedures, CD14−, CD14+, CD31+ and CD31− selected fractions were analysed by RT-PCR. RNA was isolated and converted to cDNA as described below and cDNA was assessed for CD31 and CD14 gene products using PCR followed by electrophoresis on ethidium bromide-stained 1.5% agarose gels (CD31 forward primer: 5′-CCCAGGAGCACCTCCAGCC-3′; CD31 reverse primer: GGACCTCATCCACCGGGGCT-3′; CD14 forward primer: 5′-GGGCGCCTGAGTCATCAGGACAC-3′; CD14 reverse primer: 5′-CAAGGTTCTGGCGTGGTCGCA-3′). 18S was used as the reference gene (primer sequences were published previously; Jenkins et al. 2009). For both selection antibodies, positively selected cells displayed strong expression of the target antigens, while CD31 and CD14 mRNAs were not detectable in the negatively selected fractions (data not shown).

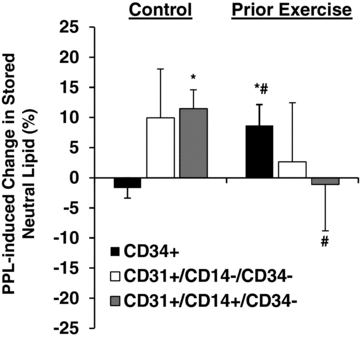

Pharmacological treatments and measurement of intracellular NO and ROS

These experiments were performed in duplicate as we have described previously (Jenkins et al. 2009; Jenkins et al. 2011), with minor modifications. Briefly, 1.5 × 105 cells were stained with 10 μm 4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′-difluorofluorescein (DAF-FM) diacetate for determination of intracellular NO levels or 2 μm 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) for determination of intracellular ROS levels (Molecular Probes). 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 750 ng ml−1) was used to label cell nuclei (Molecular Probes). Cells were also incubated with or without 250 μm apocynin (a pharmacological NADPH oxidase inhibitor) and/or 1 μm rotenone (an inhibitor of mitochondrial complex I) to determine the contribution of NADPH oxidase- and mitochondrial-derived ROS to any observed effects of PPL and/or prior exercise on intracellular ROS and NO levels. Rotenone treatments were performed on cells from a subset of subjects (n = 5), and, owing to limiting cell yields, were only performed on cells that were analysed for intracellular ROS levels. Cells were incubated with fluorescent dyes and drug or vehicle treatments in a final volume of 150 μl serum-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 60 min at 37°C. NO and ROS fluorescence were quantified using a fluorescent plate reader (Wallac Victor2 1400, Perkin Elmer) using excitation and emission filters of 488 and 535 nm, respectively. DAPI fluorescence was measured using excitation and emission filters of 355 and 460 nm, respectively. NO and ROS fluorescence values were divided by DAPI fluorescence values to normalize for cell number, and data are expressed relative to the mean for the 0 min value during the control trial without prior exercise. Intra-assay coefficients of variation for NO and ROS were both 5%.

Intracellular neutral lipid storage assay

In cells from a subset of subjects (n = 5), intracellular lipids were measured with 1 μm BODIPY 493/503 (Molecular Probes), a stain for intracellular non-polar lipids, using excitation and emission filters of 488 and 535 nm, respectively. Stored neutral lipid fluorescence values were divided by DAPI fluorescence for normalization to cell number. Data are expressed as the percentage change from 0 to 240 min within each experimental condition.

Assessment of gene expression by RT-PCR

RNA was isolated using the TRI reagent and reversed transcribed to cDNA. mRNA levels of angiogenic (endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)), pro-oxidant (inducible NOS (iNOS), oxLDL receptor (LOX-1), and NADPH oxidase subunits gp91phox and p47phox), and antioxidant genes (SOD1 and SOD2) were assessed using RT-PCR. Primer sequences and PCR conditions have been published previously (Jenkins et al. 2009; Jenkins et al. 2011). Data were normalized to 18S as a reference gene, and are presented relative to the normalized value for the 0 h time point for the control trial (set at 100%).

Serum triglyceride and oxidized LDL-cholesterol concentrations

Serum TG concentrations were examined using a standard colorimetric assay (Sigma), as described by our laboratory previously (Weiss et al. 2007). Total areas under the TG curves (TG AUC) were calculated using the trapezoidal principle (Matthews et al. 1990). The TG intra-assay coefficient of variation was 6.5%, and the inter-assay coefficient of variation was 8.5%. Serum levels of oxidized LDL cholesterol (OxLDL) were determined using a sandwich ELISA (Mercodia, Winston-Salem, NC, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Serum OxLDL was measured at 0 and 4 h only. The OxLDL assay intra-assay coefficient of variation was 4%. All samples were analysed in the same batch to eliminate inter-assay variability.

Plasma endothelial microparticles (EMPs)

Preparation of plasma

Plasma samples were thawed at room temperature and centrifuged at 1500 g for 20 min at room temperature to obtain platelet poor plasma (PPP). The top two-thirds volume of PPP was further centrifuged at 1500 g for 20 min at room temperature to obtain cell free plasma (Shah et al. 2008). The supernatant was used for microparticle analysis (Feng et al. 2010). A volume of 100 μl supernatant was incubated with the different fluorochrome-labelled antibodies for 20 min at room temperature in the dark. Two different antibody combinations were used: CD31-phycoerythrin (PE, 20 μl per sample) with CD42b-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC, 20 μl per sample), CD62E-PE (15 μl per sample). All antibodies were obtained from BD Biosciences. Samples were diluted with 500 ml of 0.22 μm double-filtered PBS before flow cytometric analysis.

Detection of endothelial microparticles using flow cytometry

Samples were analysed using a BD LSRII flow cytometer and BD FACSDIVA software. EMPs were defined as CD31+CD42b− or CD62E+ events smaller than 1.0 μm. A logarithmic scale was implemented for forward scatter signal, side scatter signal and each fluorescent channel; size calibration was done with 0.9 μm standard precision NIST Traceable polystyrene particle beads (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA) and forward scatter signal. Fluorescence minus one controls and non-stained samples were used to discriminate true events from noise, and to increase the specificity for microparticle detection for each sample. The flow rate was set on medium on LSRII and all samples were run for 180 s. Using beads, we calculated that, on medium flow rate, a mean sample volume of 101 μl per 180 s was processed. EMP counts per microlitre plasma were determined using the following formula:

|

Where the total sample volume equals 100 μl PPP stained with 20 μl CD42b-FITC and 20 μl of CD31-PE diluted with 500 μl PBS, 93 μl formaldehyde (733 μl for CD31+ CD42− and 713 μl for CD 62E), the volume of the sample analysed by the flow cytometer in 180 s equals 101 μl; and the amount of PPP used for the analysis is 100 μl (van Ierssel et al. 2010).

Statistics

Assumptions of homoscedasticity and normality were verified for all outcome measures. Data were analysed using two-factor (condition × time) or three-factor (condition × time × drug) repeated measures ANOVA, where appropriate. Analyses of simple effects were used to determine differences between control and exercise treatments at specific time points. Total TG areas under the lipaemia curves (TG AUC) were calculated using the trapezoid rule (Matthews et al. 1990) and compared between control and exercise treatments using paired t tests. Statistical significance was accepted at P≤ 0.05.

Results

Subject characteristics

Anthropometric and clinical characteristics of the study subjects are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Subject characteristics

| Mean | SEM | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 27 | 0.9 |

| BMI (kg m−2) | 24.6 | 0.7 |

| Body fat (%) | 15.1 | 1.2 |

| Glucose (mg dl−1) | 82 | 2.2 |

| Cholesterol (mg dl−1) | 163 | 5.8 |

| HDL-C (mg dl−1) | 54 | 3.2 |

| LDL-C (mg dl−1) | 93 | 3.7 |

| VLDL-C (mg dl−1) | 16 | 1.7 |

| TG (mg dl−1) | 78 | 8.1 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 120 | 3.0 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 75 | 1.8 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 90 | 1.8 |

|

||

| l min−1 | 3.75 | 0.2 |

| ml kg−1 min−1 | 48.0 | 2.2 |

Intracellular ROS and NO Levels

Reactive oxygen species

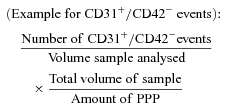

In CD31+/CD14−/CD34− cells, there was a ∼30% increase in ROS with PPL in the control condition (P < 0.05), and this effect of PPL was completely absent in the prior exercise trial (Fig. 1A). Apocynin increased ROS levels at both 0 and 4 h time points in both trials (P < 0.05), but the magnitudes of these increases were significantly greater in the control trial compared to the trial with prior exercise (P < 0.05). The apocynin-induced increase in ROS levels in these and the two other cell types (presented below) was a surprising finding, given the hypothesis of the study that NADPH oxidase inhibition would experimentally demonstrate that the PPL-induced increase in ROS would be driven by NADPH oxidase. When we observed that these findings were consistent and statistically significant after testing the first five subjects of the study, we attempted to determine if another cellular source of pro-oxidant activity could have compensated for NADPH oxidase inhibition by increasing ROS production. Thus, before testing the remaining participants, we examined the effects of allopurinol (a xanthine oxidase inhibitor), rotenone (a mitochondrial complex I inhibitor), and antimycin (a mitochondrial complex III inhibitor) in combination with apocynin (n = 3 pilot subjects). It was found that the most consistent inhibitor of the apocynin-induced increase in ROS was rotenone, i.e. ∼60–100% of the increase could be eliminated by rotenone compared to ∼20% by allopurinol and <10% by antimycin (data not shown). Therefore, rotenone was included in the experiments for the remaining subjects. The apocynin-induced increases in ROS in CD31+/CD14−/CD34− cells were completely reversed by rotenone in both the control and prior exercise trials (P < 0.05). ROS levels were lower in the prior exercise trial compared to the control trial under all experimental conditions (P < 0.05).

Figure 1. Effects of PPL with and without prior endurance exercise (left panels) and apocynin and rotenone treatments (right panels) on intracellular reactive oxygen species in CD31+/CD14−/CD34− (A), CD31+/CD14+/CD34− (B) and CD34+ (C) CACs.

Horizontal dashed line at 100% indicates control (vehicle) condition. *Statistically significant difference from 0 h control (vehicle) condition (P < 0.05). #Magnitude of change from 0 h control (untreated) condition is significantly different between control and prior exercise trials (P < 0.05). †Statistically significant difference between rotenone and apocynin-treated cells (P < 0.05).

In CD31+/CD14+/CD34− cells, PPL increased ROS by ∼25% in the control trial (P < 0.05), and this increase was absent in the trial with prior exercise (Fig. 1B). Apocynin substantially increased ROS levels at both time points during both trials (P < 0.05), and again this was completely reversed by rotenone treatment (P < 0.05). The magnitude of the increase in ROS levels with apocynin treatments and the degree of reduction by rotenone treatments were similar between control and exercise trials.

In CD34+ cells, PPL induced a small (∼10%), but statistically significant, increase in ROS in the trial with prior exercise (P < 0.05), but no change was observed in the control trial (Fig. 1C). NADPH oxidase inhibition with apocynin induced ∼2- to 2.5-fold increases in ROS levels at 0 h and 4 h in both the control and prior exercise trials (P < 0.05), which was completely attenuated by co-incubation with rotenone (P < 0.05).

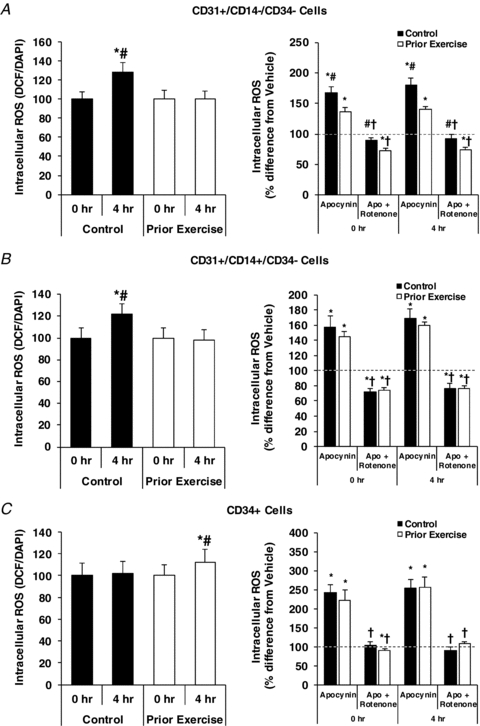

Nitric oxide

There were no effects of PPL or apocynin on NO levels in either the prior exercise or control trial in CD34+/CD14−/CD34− cells (Fig. 2A). In CD34+/CD14+/CD34− cells, PPL increased NO levels both with and without apocynin treatments by ∼10–15% in the control trial (P < 0.05), but there were no effects of PPL or apocynin in the prior exercise trial (Fig. 2B). PPL had no effect on NO in CD34+ cells during the control trial, but induced a ∼10% decrease in NO during the trial with prior exercise (P < 0.05). This 10% reduction in NO was reversed upon treatment with apocynin (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. Effects of PPL and apocynin treatment with and without prior endurance exercise on intracellular nitric oxide in CD31+/CD14−/CD34− (A), CD31+/CD14+/CD34− (B) and CD34+ (C) circulating angiogenic cells.

*Statistically significant difference from 0 h control (vehicle) condition (P < 0.05). #Change from 0 h control (untreated) condition is significantly different between trials (P < 0.05).

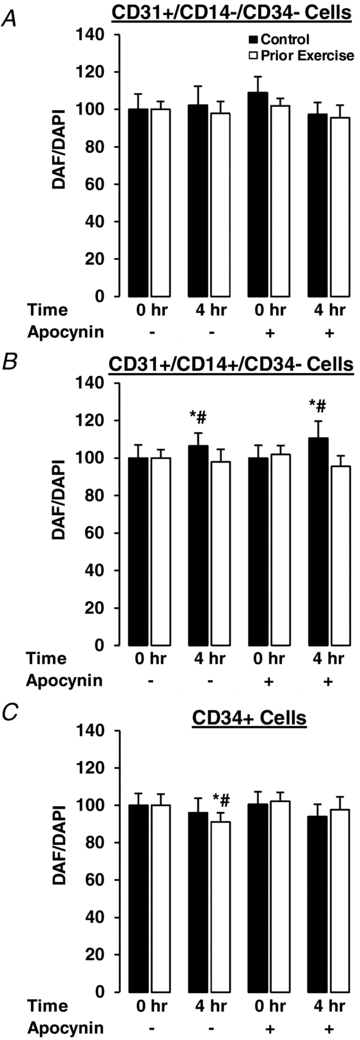

Intracellular neutral lipid storage

Within the CD34+ cells, PPL caused a significant increase in stored neutral lipids during the prior exercise trial (P < 0.05), but there was no change during the control trial (Fig. 3). There were no significant PPL-induced changes in stored neutral lipids in CD31+/CD14−/CD34− cells in either trial. In CD31+/CD14+/CD34− cells, intracellular lipids increased significantly in the control trial (P < 0.05), but there was no effect of PPL in the prior exercise trial. There were no differences in basal (0 h) stored neutral lipid levels between the control and prior exercise trials (data not shown).

Figure 3. PPL-induced changes in stored neutral lipid in circulating angiogenic cells with and without prior endurance exercise.

*Statistically significant change within trial (i.e. the percentage change is different from zero; P < 0.05). #Magnitude of change is significantly different between trials (P < 0.05).

Circulating TG, OxLDL and EMP concentrations

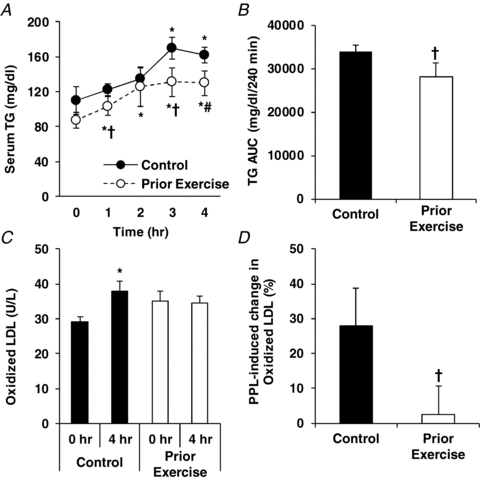

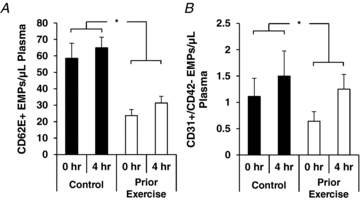

Fasting (i.e. 0 h) serum concentrations of TG and OxLDL were not different between trials (P > 0.05; Fig. 4). Serum TG concentrations increased significantly throughout the sampling period in both the control and prior exercise trials (P < 0.05), but the concentrations were lower (P < 0.05) at 1 and 3 h, and tended to be lower at 4 h (P = 0.06), during the prior exercise trial compared to the control trial (Fig. 4A). TG AUC was significantly lower in the prior exercise trial compared to the control trial (Fig. 4B, P < 0.05). There was a 28% increase in serum oxLDL concentration in the control trial (P < 0.05), and there was no change in oxLDL concentration in response to the high-fat meal with exercise performed on the prior day (Fig. 4C and D). Plasma EMP markers of endothelial activation (Fig. 5A) and endothelial apoptosis (Fig. 5B) were lower in the prior exercise trial compared to the control trial (55% and 30%, respectively; both P < 0.05), but were unaffected by the high-fat meal in either trial.

Figure 4. Effects of prior exercise on PPL as measured by serum TG concentrations (A), TG AUC (B) and oxLDL (C), and PPL-induced change (%) in OxLDL in control and prior exercise trials (D).

*Statistically significant difference from 0 h time point within trial (P < 0.05). †Statistically significant difference between trials (P < 0.05). #P = 0.06 for difference between trials in serum TG concentration at 4 h time point.

Figure 5. Effects of PPL with and without prior endurance exercise on plasma endothelial microparticles (EMPs).

A, EMP fragments of activated endothelium (CD62E+ EMPs); B, apoptotic endothelial CD31+/CD42− EMPs. *P < 0.05 for main effect of prior exercise.

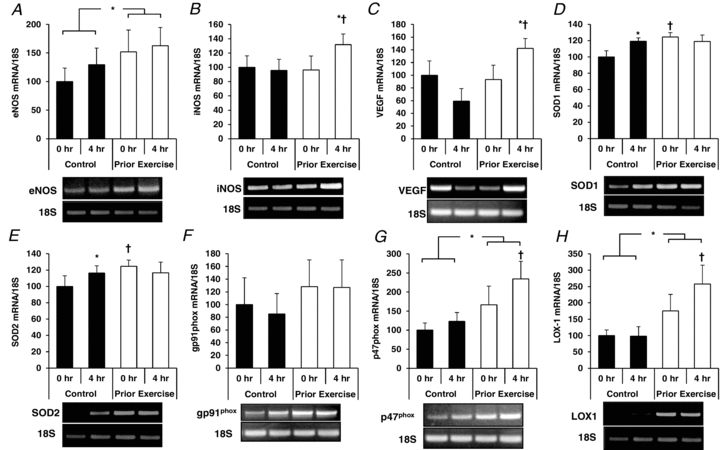

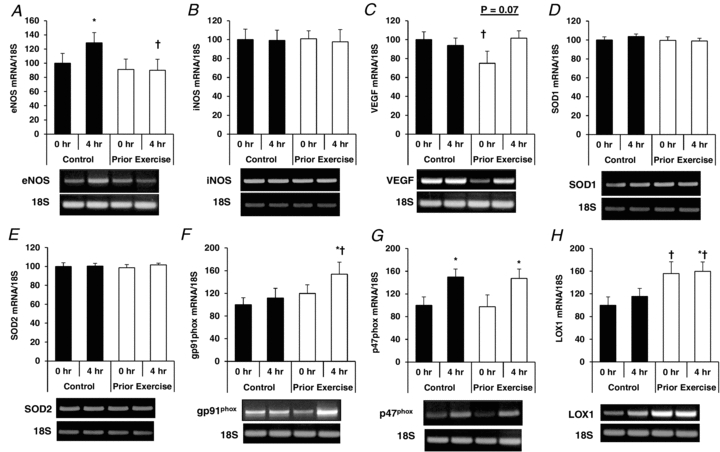

Gene expression

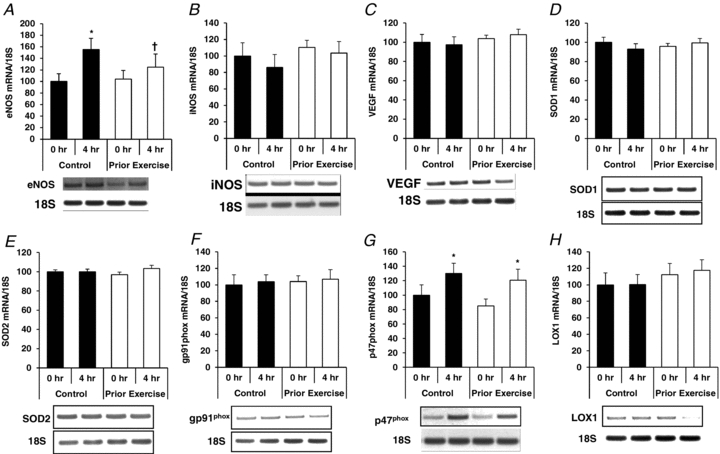

Overall, the pattern of gene expression varied considerably among the three cell types in response to PPL with and without prior endurance exercise. The major finding was that prior exercise increased expression of the antioxidant genes SOD1 and SOD2 in CD31+/CD14−/CD34− cells at both 0 h and 4 h time points (Fig. 6), while SOD1 and SOD2 gene mRNA levels were not affected by prior exercise in either CD31+/CD14−/CD34− (Fig. 7) or CD34+ (Fig. 8) cells. Additional data on mRNA levels of eNOS, iNOS, VEGF, NADPH oxidase subunits gp91phox and p47phox, and LOX1 are presented in Figs 6–8.

Figure 6. Effects of PPL with and without prior endurance exercise on eNOS (A), iNOS (B), VEGF (C), SOD1 (D), SOD2 (E), gp91phox (F), p47phox (G) and LOX1 (H) mRNA levels in CD31+/CD14−/CD34− cells.

*Statistically significant change from within-trial 0 h sample (P < 0.05). †Statistically significant difference from corresponding time point between trials (P < 0.05).

Figure 7. Effects of PPL with and without prior endurance exercise on eNOS (A), iNOS (B), VEGF (C), SOD1 (D), SOD2 (E), gp91phox (F), p47phox (G) and LOX1 (H) mRNA levels in CD31+/CD14+/CD34− cells.

*Statistically significant change from within-trial 0 h sample (P < 0.05). †Statistically significant difference from corresponding time point between trials (P < 0.05).

Figure 8. Effects of PPL with and without prior endurance exercise on eNOS (A), iNOS (B), VEGF (C), SOD1 (D), SOD2 (E), gp91phox (F), p47phox (G) and LOX1 (H) mRNA levels in CD34+ cells.

*Statistically significant change from within-trial 0 h sample (P < 0.05). †Statistically significant difference from corresponding time point between trials (P < 0.05).

Correlation analysis indicated no significant correlations between TG AUC and exercise/PPL-induced effects on any cell-based outcomes (ROS, NO, neutral lipid storage and gene expression) in the three different CAC types.

Discussion

The major finding of this study is that PPL increases intracellular ROS in CD31+/CD14−/CD34− and CD31+/CD14+/CD34− PBMCs, and this effect is prevented by performing endurance exercise on the prior day. Consistent with previous data indicating that postprandial oxidative stress is caused by an increase in mitochondria-derived ROS production (Brownlee, 2005; Wallace et al. 2010), our data implicate mitochondria as a possible source of PPL-induced increases in intracellular ROS in the CD31+ CAC subfractions. In addition, we observed beneficial effects of exercise on PPL-induced changes in intracellular storage of neutral lipids and expression of genes involved in the functional status of CACs; however, there were adverse effects of PPL on CD34+ cells (i.e. elevated ROS, reduced NO, and increased stored neutral lipid) in the prior exercise trial only. Therefore, our data suggest that the effects of exercise are not uniform among CAC subpopulations.

Prior exercise protects against high-fat meal-induced increases in intracellular ROS of CD31+/CD14−/CD34− and CD31+/CD14+/CD34− cells

We hypothesized that NADPH oxidase would play a role in the effects of PPL-induced oxidative stress, as PPL has been shown to increase OxLDL (Tushuizen et al. 2006), and OxLDL increases NADPH oxidase expression in cultured CACs (Ma et al. 2006). However, in the present study apocynin treatment induced a dramatic increase in intracellular ROS levels in all three CAC types. We were able to determine that mitochondria up-regulate ROS production with acute apocynin treatments in all three cell types examined, as the apocynin-induced increase in ROS was completely reversed upon treatment with the complex I inhibitor rotenone. Further, and more importantly, the protective effects of exercise against PPL-induced ROS production in both CD31+ cell fractions appeared to be mitochondria dependent, as indicated by the return to 0 h ROS levels in rotenone-treated 4-h cells. However, we acknowledge that a limitation of our study is that we did not include a rotenone-only treatment condition. It would have been advantageous to have measured mitochondrial electron transport chain complex activity directly (e.g. complex I and IV). This would have confirmed that the PPL-induced ROS production and the reduction with prior exercise were indeed mitochondria dependent. Thus, our interpretation that mitochondria might account for the PPL-induced ROS increase must be taken with caution, and will require confirmation in further experiments designed a priori to examine the role of mitochondria. It is also important to mention that in our preliminary experiments, apocynin at the chosen concentration (250 μm) decreased basal ROS production as measured by dichlorodihydrofluorescein (DCF) fluorescence in unfractionated PBMCs (data not shown), and previous studies have used similar or greater concentrations of apocynin to investigate the NADPH oxidase-driven components of cultured endothelial cell ROS production (Monaghan-Benson et al. 2010) and vascular endothelial dysfunction (Durrant et al. 2009). Thus, the up-regulation of mitochondria-derived ROS by apocynin in our experiments appears to be a phenomenon specific to the CAC populations examined in the present study, and the biology of redox regulation does not appear to be uniform between vessel wall endothelial cells and CACs.

Furthermore, it is interesting that the degree of the mitochondria-mediated increase in ROS was blunted with prior exercise in the CD31+/CD14−/CD34− fraction, indicating that in these cells there was an attenuation of mitochondrial ROS production in response to the high-fat meal, or there may have been an up-regulation of intracellular antioxidant defences that resulted in enhanced scavenging of ROS. In line with the latter possibility, we also found increases in both SOD1 and SOD2 mRNA levels in CD31+/CD14−/CD34− cells with exercise (Fig. 6). In CD31+/CD14+/CD34− cells, on the other hand, the PPL-induced increase in ROS was similarly blunted by prior exercise, and yet there were no effects of exercise on antioxidant gene expression (Fig. 7). However, in these cells prior exercise caused a significant reduction in the degree of neutral lipid storage with PPL, which would be expected to result in attenuated ROS production (Wallace et al. 2010). Regardless, the critical finding of the present study is protection against PPL-induced oxidative stress in CD31+/CD14−/CD34− and CD31+/CD14+/CD34− angiogenic cells by prior exercise.

These findings are especially important in light of recent reports that CD31+ cells in bone marrow and peripheral blood are an important source of CACs for the maintenance of vascular endothelial integrity and are effective for cell-based regenerative medicine therapy (Kim et al. 2010a,b;). Our data suggest that exercise may enhance the ability of CD31+ CACs to cope with a physiological pro-oxidative challenge, and may therefore improve the efficacy of these cells for therapeutic treatment of CV diseases.

Exercise and PPL have minimal effects on intracellular NO in CACs

Surprisingly, there were few significant effects of PPL, exercise, or their interaction on intracellular NO levels in the three cell types examined in the present study. Given the critical role for NO in a number of CAC functions, we expected that NO would be reduced by PPL without prior exercise and that this reduction would be absent, or at least blunted, in the trial with prior exercise. Thus, the reduction in NO in CD34+ cells during the prior exercise trial was not anticipated. However, it was consistent with the gene expression data indicating that eNOS expression increased with PPL in the control but not the prior exercise trial. Similarly, there were no changes in NO levels in CD31+/CD14−/CD34− cells, although in these cells mRNA levels of both NOS isoforms were significantly increased during the prior exercise trial compared to the sedentary trial. These effects at the mRNA level were not associated with changes at the functional level (i.e. intracellular NO). In CD31+/CD14+/CD34− cells, conversely, PPL-induced increases in eNOS mRNA and in intracellular NO were observed both in the control trial, but not in the trial with prior exercise. However, it must be emphasized that the changes in NO in both CD34+ and CD31+/CD14+/CD14− cells, while statistically significant, were relatively small (∼10%), and therefore further research is needed to determine the physiological significance of these findings.

Role of lipid storage and gene expression: evidence for CAC subpopulation-specific mechanisms underlying effects of exercise

As mentioned above, we observed higher SOD1 and SOD2 mRNA levels in CD31+/CD14−/CD34− cells during the prior exercise trial, but there were no differences between trials in these antioxidant genes in CD31+/CD14+/CD34− cells. Conversely, there were no effects on lipid storage in CD31+/CD14−/CD34− cells, whereas in CD31+/CD14+/CD34− cells there was a significant reduction in the degree of PPL-induced lipid storage with prior exercise. Furthermore, the expression profile of the angiogenic, pro-oxidative, and antioxidant genes varied considerably in response to PPL and exercise among the three cell types (Figs 6–8). Therefore, it would appear that the mechanisms by which prior exercise and high-fat meal ingestion alter the phenotype of CACs are not uniform among specific CAC subpopulations.

Exercise blunts PPL-induced increases in serum TG and OxLDL and reduces EMPs in spite of PPL

Our finding of a reduction in TG AUC following ingestion of a high-fat meal with exercise performed on the prior day is consistent with numerous previous studies (for review, see Petitt & Cureton 2003). An increase in serum OxLDL has been observed in response to ingestion of a high-fat meal (Tushuizen et al. 2006), and to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report an absence of a PPL-induced increase in OxLDL with prior endurance exercise. As OxLDL has been previously reported to cause dysfunction of cultured CACs through increased intracellular oxidative stress (Ma et al. 2006), the mechanisms underlying our findings of reduced intracellular ROS may have involved the reduced exposure to circulating OxLDL after the high-fat meal with prior exercise. In addition, our data provide the first evidence that exercise can reduce circulating EMPs, a well-established marker of damaged vascular endothelium (Horstman et al. 2004). Specifically, EMP populations indicating the presence of endothelial activation and endothelial apoptosis were lower in the exercise trial compared to the sedentary trial, even in the face of the high-fat challenge, which has previously been shown to increase circulating EMPs (Ferreira et al. 2004; Tushuizen et al. 2006). Thus, our TG, OxLDL and EMP data are in line with (i) the known effects of a high-fat meal on TGs and on systemic oxidative stress, and (ii) the reduction in or prevention of PPL-induced vascular dysfunction (Padilla et al. 2006; Tyldum et al. 2009), which is mediated by oxidative stress (Plotnick et al. 1997, 2003; Wallace et al. 2010).

Limitations and future directions

There are at least three priorities for future research arising from issues that we did not address in our study: (i) to determine the mechanistic contribution of ROS to exercise and/or high fat meal-induced effects on functional aspects of CACs (e.g. angiogenic capacity), (ii) to determine the effect of long-term exercise training on molecular and functional responses of CACs to a high fat meal, and (iii) to further investigate whether the effects of exercise and/or high-fat meals vary among CAC subsets from specific sources (e.g. bone marrow or vessel wall).

Conclusions

In summary, we have shown that the PPL-induced increases in intracellular ROS production in CD31+ cells are prevented by prior endurance exercise. Our experiments suggested mitochondria as the source of the PPL-induced increase in ROS, although future studies designed a priori to determine the role of mitochondria in PPL-induced ROS production in CACs are required for confirmation. Nevertheless, our findings add to the strong and consistent evidence that the detrimental effects of PPL on the CV system are mediated by oxidative stress, and our direct measurements of the intracellular environment within human CACs indicate that these effects of PPL can be prevented by prior endurance exercise. Our data also provide novel insight into the understanding of how situations encountered in daily life, such as exercise and high-fat meal ingestion, might alter the endothelial repair capacity of CACs. These findings were linked to prior exercise-induced reductions in circulating TG, OxLDL and EMP concentrations during PPL, suggesting a systemic CV benefit of exercise even in the face of a high-fat challenge. Finally, our results could provide important information for the ongoing efforts to optimize the application of CACs for therapeutic treatment of CV disease patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank the volunteers for their time and commitment to this study. Arpit Singhal and Eric Freese are thanked for technical advice. Stephen Roth is thanked for generously allowing our use of resources in the UMCP Functional Genomics Laboratory. N.T.J. and R.Q.L. were supported by NIH Predoctoral Institutional Training Grant T32AG000268 (to J.M.H.). S.J.P. was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs (CDA-2-0039) and the Baltimore Veterans Affairs Medical Center Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center. This study was supported by grants from the American College of Sports Medicine Foundation (to N.T.J.), the University of Maryland Department of Kinesiology Graduate Research Initiative Fund (to N.T.J.), and the National Institutes of Health (R21 HL098810, to J.M.H., and RO1 HL085497, to M.D.B.).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CAC

circulating angiogenic cell

- CV

cardiovascular

- EMP

endothelial microparticle

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- LOX-1

oxidized LDL receptor-1

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- OxLDL

oxidized low density lipoprotein-cholesterol

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- PPL

postprandial lipaemia

- PPP

platelet poor plasma

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- TG

triglyceride

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Author contributions

Conception and design of experiments: N.T.J. and J.M.H. Collection of data: N.T.J., R.Q.L., S.R.T., X.F. and J.M.H. Analysis and interpretation of data: N.T.J., R.Q.L., S.R.T., M.D.B., S.J.P., E.E.S. and J.M.H. Drafting the paper/critical revision for important intellectual content: N.T.J., RQ.L., S.R.T., M.D.B., S.J.P., E.E.S. and J.M.H. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. Plasma endothelial microparticle measurements were performed at Temple University. All other work was done at the University of Maryland.

Author's present address

N. T. Jenkins: E102 Vet Med Bldg, Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA.

References

- Alipour A, van Oostrom AJ, Izraeljan A, Verseyden C, Collins JM, Frayn KN, Plokker TW, Elte JW, Castro Cabezas M. Leukocyte activation by triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:792–797. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.159749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RA, Evans ML, Ellis GR, Graham J, Morris K, Jackson SK, Lewis MJ, Rees A, Frenneaux MP. The relationships between post-prandial lipaemia, endothelial function and oxidative stress in healthy individuals and patients with type 2 diabetes. Atherosclerosis. 2001;154:475–483. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00499-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahara T, Masuda H, Takahashi T, Kalka C, Pastore C, Silver M, Kearne M, Magner M, Isner JM. Bone marrow origin of endothelial progenitor cells responsible for postnatal vasculogenesis in physiological and pathological neovascularization. Circ Res. 1999;85:221–228. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.3.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, Silver M, van der Zee R, Li T, Witzenbichler B, Schatteman G, Isner JM. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science. 1997;275:964–966. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad O, Dedkov EI, Jiao C, Bloomer S, Tomanek RJ, Schatteman GC. Differential healing activities of CD34+ and CD14+ endothelial cell progenitors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:758–764. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000203513.29227.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae JH, Bassenge E, Kim KB, Kim YN, Kim KS, Lee HJ, Moon KC, Lee MS, Park KY, Schwemmer M. Postprandial hypertriglyceridemia impairs endothelial function by enhanced oxidant stress. Atherosclerosis. 2001;155:517–523. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00601-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: a unifying mechanism. Diabetes. 2005;54:1615–1625. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby JR, Kaminski WE, Schatteman G, Martin PJ, Raines EW, Seifert RA, Bowen-Pope DF. Endothelial cells of hematopoietic origin make a significant contribution to adult blood vessel formation. Circ Res. 2000;87:728–730. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.9.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimmeler S, Aicher A, Vasa M, Mildner-Rihm C, Adler K, Tiemann M, Rutten H, Fichtlscherer S, Martin H, Zeiher AM. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) increase endothelial progenitor cells via the PI 3-kinase/Akt pathway. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:391–397. doi: 10.1172/JCI13152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant JR, Seals DR, Connell ML, Russell MJ, Lawson BR, Folian BJ, Donato AJ, Lesniewski LA. Voluntary wheel running restores endothelial function in conduit arteries of old mice: direct evidence for reduced oxidative stress, increased superoxide dismutase activity and down-regulation of NADPH oxidase. J Physiol. 2009;587:3271–3285. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.169771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadini G, Pucci L, Vanacore R, Baesso I, Penno G, Balbarini A, Di Stefano R, Miccoli R, de Kreutzenberg S, Coracina A, Tiengo A, Agostini C, Del Prato S, Avogaro A. Glucose tolerance is negatively associated with circulating progenitor cell levels. Diabetologia. 2007;50:2156–2163. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0732-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadini GP, de KS, Agostini C, Boscaro E, Tiengo A, Dimmeler S, Avogaro A. Low CD34+ cell count and metabolic syndrome synergistically increase the risk of adverse outcomes. Atherosclerosis. 2009;207:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng B, Chen Y, Luo Y, Chen M, Li X, Ni Y. Circulating level of microparticles and their correlation with arterial elasticity and endothelium-dependent dilation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Atherosclerosis. 2010;208:264–269. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez Pujol B, Lucibello FC, Gehling UM, Lindemann K, Weidner N, Zuzarte ML, Adamkiewicz J, Elsasser HP, Muller R, Havemann K. Endothelial-like cells derived from human CD14 positive monocytes. Differentiation. 2000;65:287–300. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2000.6550287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira AC, Peter AA, Mendez AJ, Jimenez JJ, Mauro LM, Chirinos JA, Ghany R, Virani S, Garcia S, Horstman LL, Purow J, Jy W, Ahn YS, de Marchena E. Postprandial hypertriglyceridemia increases circulating levels of endothelial cell microparticles. Circulation. 2004;110:3599–3603. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000148820.55611.6B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gower RM, Wu H, Foster GA, Devaraj S, Jialal I, Ballantyne CM, Knowlton AA, Simon SI. CD11c/CD18 expression is upregulated on blood monocytes during hypertriglyceridemia and enhances adhesion to vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:160–166. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.215434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harraz M, Jiao C, Hanlon HD, Hartley RS, Schatteman GC. CD34− blood-derived human endothelial cell progenitors. Stem Cells. 2001;19:304–312. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.19-4-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison M, O'Gorman DJ, McCaffrey N, Hamilton MT, Zderic TW, Carson BP, Moyna NM. Influence of acute exercise with and without carbohydrate replacement on postprandial lipid metabolism. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:943–949. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91367.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horstman LL, Jy W, Jimenez JJ, Ahn YS. Endothelial microparticles as markers of endothelial dysfunction. Front Biosci. 2004;9:1118–1135. doi: 10.2741/1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyson DA, Paglieroni TG, Wun T, Rutledge JC. Postprandial lipemia is associated with platelet and monocyte activation and increased monocyte cytokine expression in normolipemic men. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2002;8:147–155. doi: 10.1177/107602960200800211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AS, Pollock ML. Generalized equations for predicting body density of men. Br J Nutr. 1978;40:497–504. doi: 10.1079/bjn19780152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins NT, Landers RQ, Prior SJ, Soni N, Spangenburg EE, Hagberg JM. Effects of acute and chronic endurance exercise on intracellular nitric oxide and superoxide in CD34+ and CD34− cells. J Appl Physiol. 2011;111:929–937. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00541.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins NT, Witkowski S, Spangenburg EE, Hagberg JM. Effects of acute and chronic endurance exercise on intracellular nitric oxide in putative endothelial progenitor cells: role of NAPDH oxidase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1798–H1805. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00347.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Cho HJ, Kim SW, Liu B, Choi YJ, Lee J, Sohn YD, Lee MY, Houge MA, Yoon YS. CD31+ cells represent highly angiogenic and vasculogenic cells in bone marrow: novel role of nonendothelial CD31+ cells in neovascularization and their therapeutic effects on ischemic vascular disease. Circ Res. 2010a;107:602–614. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.218396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SW, Kim H, Cho HJ, Lee JU, Levit R, Yoon YS. Human peripheral blood-derived CD31+ cells have robust angiogenic and vasculogenic properties and are effective for treating ischemic vascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010b;56:593–607. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma FX, Zhou B, Chen Z, Ren Q, Lu SH, Sawamura T, Han ZC. Oxidized low density lipoprotein impairs endothelial progenitor cells by regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1227–1237. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500507-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacEneaney OJ, Kushner EJ, Van Guilder GP, Greiner JJ, Stauffer BL, DeSouza CA. Endothelial progenitor cell number and colony-forming capacity in overweight and obese adults. Int J Obes(Lond) 2009;33:219–225. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews JN, Altman DG, Campbell MJ, Royston P. Analysis of serial measurements in medical research. BMJ. 1990;300:230–235. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6719.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer A, Lee S, Jung F, Grutz G, Lendlein A, Hiebl B. CD14+ CD163+ IL-10+ monocytes/macrophages: Pro-angiogenic and non pro-inflammatory isolation, enrichment and long-term secretion profile. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2010;46:217–223. doi: 10.3233/CH-2010-1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan-Benson E, Hartmann J, Vendrov AE, Budd S, Byfield G, Parker A, Ahmad F, Huang W, Runge M, Burridge K, Madamanchi N, Hartnett ME. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor-induced activation of NADPH oxidase in choroidal endothelial cells and choroidal neovascularization. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:2091–2102. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacher P, Beckman JS, Liaudet L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:315–424. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla J, Harris RA, Fly AD, Rink LD, Wallace JP. The effect of acute exercise on endothelial function following a high-fat meal. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2006;98:256–262. doi: 10.1007/s00421-006-0272-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petitt DS, Cureton KJ. Effects of prior exercise on postprandial lipemia: A quantitative review. Metabolism. 2003;52:418–424. doi: 10.1053/meta.2003.50071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotnick GD, Corretti MC, Vogel RA. Effect of antioxidant vitamins on the transient impairment of endothelium-dependent brachial artery vasoactivity following a single high-fat meal. JAMA. 1997;278:1682–1686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotnick GD, Corretti MC, Vogel RA, Hesslink R, Jr, Wise JA. Effect of supplemental phytonutrients on impairment of the flow-mediated brachial artery vasoactivity after a single high-fat meal. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1744–1749. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00302-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romagnani P, Annunziato F, Liotta F, Lazzeri E, Mazzinghi B, Frosali F, Cosmi L, Maggi L, Lasagni L, Scheffold A, Kruger M, Dimmeler S, Marra F, Gensini G, Maggi E, Romagnani S. CD14+CD34low cells with stem cell phenotypic and functional features are the major source of circulating endothelial progenitors. Circ Res. 2005;97:314–322. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000177670.72216.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatteman GC, Awad O. In vivo and in vitro properties of CD34+ and CD14+ endothelial cell precursors. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;522:9–16. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0169-5_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah MD, Bergeron AL, Dong JF, Lopez JA. Flow cytometric measurement of microparticles: pitfalls and protocol modifications. Platelets. 2008;19:365–372. doi: 10.1080/09537100802054107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sies H, Stahl W, Sevanian A. Nutritional, dietary and postprandial oxidative stress. J Nutr. 2005;135:969–972. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.5.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal A, Trilk JL, Jenkins NT, Bigelman KA, Cureton KJ. Effect of intensity of resistance exercise on postprandial lipemia. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:823–829. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90726.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivan-Loukianova E, Awad OA, Stepanovic V, Bickenbach J, Schatteman GC. CD34+ blood cells accelerate vascularization and healing of diabetic mouse skin wounds. J Vasc Res. 2003;40:368–377. doi: 10.1159/000072701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thijssen DHJ, Vos JB, Verseyden C, van Zonneveld AJ, Smits P, Sweep FCGJ, Hopman MTE, de Boer HC. Haematopoietic stem cells and endothelial progenitor cells in healthy men: effect of aging and training. Aging Cell. 2006;5:495–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tushuizen ME, Nieuwland R, Scheffer PG, Sturk A, Heine RJ, Diamant M. Two consecutive high-fat meals affect endothelial-dependent vasodilation, oxidative stress and cellular microparticles in healthy men. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:1003–1010. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyldum GA, Schjerve IE, Tjonna AE, Kirkeby-Garstad I, Stolen TO, Richardson RS, Wisloff U. Endothelial dysfunction induced by post-prandial lipemia: complete protection afforded by high-intensity aerobic interval exercise. J Am CollCardiol. 2009;53:200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ierssel SH, Van Craenenbroeck EM, Conraads VM, Van Tendeloo VF, Vrints CJ, Jorens PG, Hoymans VY. Flow cytometric detection of endothelial microparticles (EMP): effects of centrifugation and storage alter with the phenotype studied. Thromb Res. 2010;125:332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varela LM, Ortega A, Bermudez B, Lopez S, Pacheco YM, Villar J, Abia R, Muriana FJ. A high-fat meal promotes lipid-load and apolipoprotein B-48 receptor transcriptional activity in circulating monocytes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:918–925. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.007765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel RA, Corretti MC, Plotnick GD. Effect of a single high-fat meal on endothelial function in healthy subjects. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:350–354. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00760-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JP, Johnson B, Padilla J, Mather K. Postprandial lipaemia, oxidative stress and endothelial function: a review. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64:389–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss EP, Brandauer J, Kulaputana O, Ghiu IA, Wohn CR, Phares DA, Hagberg JM. FABP2 Ala54Thr genotype is associated with glucoregulatory function and lipid oxidation after a high-fat meal in sedentary nondiabetic women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:102–108. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkowski S, Lockard MM, Jenkins NT, Obisesan TO, Spangenburg EE, Hagberg JM. Relationship between circulating progenitor cells, vascular function and oxidative stress with long-term training and short-term detraining in older men. Clin Sci (Lond) 2010;118:303–311. doi: 10.1042/CS20090253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]