Abstract

Background

The impulse oscillation system (IOS) offers significant value in the assessment of airway dynamics in persons with spinal cord injury (SCI) because of minimal patient effort but measurement reproducibility in SCI is unknown.

Objective

To evaluate between-day reproducibility and the effect of posture on airway resistance [respiratory resistances at 5 Hz (R5) and 20 Hz (R20)] in subjects with tetraplegia, paraplegia and able-bodied controls.

Methods

Ten subjects with tetraplegia, 10 subjects with paraplegia and 11 able-bodied individuals were evaluated using IOS. Three 30 second trials were obtained in each while in the seated and supine position on Day 1, and repeated on Day 2.

Results

The within-day coefficient of variation (CV%) for R5 and R20 were comparable in the 3 study groups in the seated and supine positions. Compared to controls, the between-day CV% for the combined data was higher in subjects with tetraplegia and paraplegia for R5 seated, and was higher in subjects with tetraplegia for R5 supine.

Conclusions

IOS has applicability to the study of within-day respiratory resistance in SCI. However, performing longer-term studies in subjects with tetraplegia and paraplegia may be problematic because of the greater variability for R5 when compared to able-bodied individuals.

Keywords: Spinal cord injuries, Paraplegia, Tetraplegia, Forced oscillation technique, Airway dynamics, Respiratory resistance, Airway obstruction, Spirometry, Plethysmography

Introduction

The forced oscillation technique (FOT) and a user-friendly commercial version known as the impulse oscillation system (IOS) have been shown to be reliable methods for the evaluation of airway function in healthy subjects and those with airway obstruction.1,2 Forced oscillation applies external pressures to the respiratory system to measure respiratory impedance, which is differentiated by computer-assisted methods to yield resistive and reactive components.1 The resistive component reflects resistance of the oropharynx, larynx, trachea, large and small airways, and lung and chest wall tissue.1 Impulse oscillation studies indicate that resistances at lower frequencies (<15 Hz) reflect capacitative properties of peripheral airways, whereas higher oscillation frequencies measure more prominently the inertial properties of larger central airways.3 The IOS assesses resistive and reactive components by use of an impulse-shaped, time-discrete external forcing signal, rather than by periodic pseudorandom noise oscillations as used with FOT, and by differences in data processing.2

There are distinct clinical advantages for using IOS technology in patients with spinal cord injury (SCI); the procedure is noninvasive, independent of effort, and requires minimal cooperation because forced oscillations are superimposed on tidal volume breaths. Additionally, airway dynamics may be difficult to assess by spirometry in SCI, because some subjects with tetraplegia fail to fulfill American Thoracic Society spirometry criteria due to excessive back extrapolated volumes and/or because exhalations are less than 6 seconds in duration.4,5 Also, assessment of airway resistance by whole-body plethysmography may be problematic because subjects with SCI may have difficulties transferring in and out of the body box.

In a previous study evaluating ipratropium-induced bronchodilation in SCI by spirometry, body plethysmography, and the IOS, we demonstrated using minimal difference as an index of intra-subject variability that baseline within-day intra-class correlation coefficients for IOS respiratory resistances measured at 5 and 20 Hz (R5 and R20, respectively) did not differ significantly among subjects with tetraplegia, high paraplegia, low paraplegia, and controls.6 However, day-to-day variability of R5 and R20 measurements among subjects with SCI has not been investigated. As such, it remains to be determined whether performing IOS is of value in assessing airway dynamics in long-term experiments. Accordingly, a primary goal of this study was to evaluate variability of between-day R5 and R20 values in subjects with tetraplegia and paraplegia compared to that in able-bodied individuals, who served as controls. A second goal was to assess variability of R5 and R20 measurements in the supine position, and as a correlate, determine if R5 and R20 values increase in the supine position among subjects with tetraplegia and paraplegia, as was previously demonstrated by forced oscillation studies among able-bodied individuals.7–11

Methods

Subjects

Thirty-one subjects were recruited from the Kessler Institute for Rehabilitation and consented to participate in the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and written consent was obtained for all subjects prior to participation. Subjects included 10 individuals with clinically stable chronic tetraplegia (>6 months) who were matched for age (±10 years), height (±2 cm), gender with 10 subjects with clinically stable chronic paraplegia (>6 months), and 11 able- bodied healthy control subjects. Subjects with a history of chronic respiratory diseases were excluded from enrollment in the study, as were subjects with recent acute respiratory illnesses.

Procedures

Mass flow sensor calibration was performed daily in the morning and again before each subject was tested using a standard 3-liter volumetric syringe. The IOS measurements for R5 and R20 were performed while the subjects were seated upright and then again while lying supine on a hospital bed at the same time of the day on two separate visits within a 2-week period. All but three subjects were re-tested within 7 days. All SCI subjects were instructed to catheterize or empty their leg bags prior to conducting any IOS measurements. Blood pressure and symptoms of autonomic dysreflexia were monitored prior to performing IOS measurements in the seated and supine position.

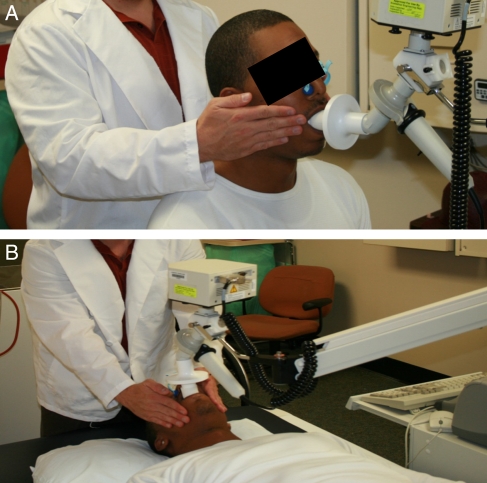

The subjects with paraplegia and the controls were instructed to place their hands on the buccinators muscles of the face to control for oscillation trapping inside the oral cavity. For individuals with tetraplegia a research assistant provided cheek support. In the seated position, subjects with paraplegia and controls were instructed to keep their back against the wheelchair or chair in order to replicate the seated position of those with tetraplegia. In the supine position, a pillow was placed under the head to align the spine. Subjects were placed on a mouthpiece and a nose clip was applied to prevent air leakage. In both positions subjects were instructed to breathe normally for 90 seconds per trial through a free-flow mouthpiece into a commercially available IOS (VIASYS, Healthcare Respiratory Technology, Yorba Linda, CA, USA). A visual example of a subject being tested is provided (Figs 1A and B).

Figure 1.

The use of the IOS in the seated (A) and supine (B) positions is shown. A staff member is shown providing hand support to the cheeks of the subject.

The IOS generated pressure pulses 5 times per second, and R5 and R20 were calculated from the pressure/flow relationship obtained from impulses applied at the mouth. A single trial recording of a 30-second sample was accepted if the coherence (signal-to-noise ratio) was ≥0.7 at 5 Hz and ≥0.9 at 20 Hz. The mouthpiece and nose clip were removed between trials. Each subject performed a minimal of three acceptable, 30-second trials while in the seated and supine positions on both test days. Any trial during which a subject deviated from the resting breathing pattern (i.e. cough, sigh, yawn, etc.) during data collection was deleted and the trial was repeated. Only three subjects had to perform more than three 30-second sampling trials. Testing was stopped once three acceptable values were obtained for the seated and supine position on both test days.

Statistical analyses

The dichotomous variables (completeness of lesion and gender) were tested by chi squared analysis for differences in distribution among the groups. Duration of injury (DOI) was compared between the two SCI groups by use of an unpaired t-test. All other demographic characteristics (age, height, weight, and body mass index) were compared among the groups by one-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA). The mean value of three acceptable trials was used for each position (seated and supine) for each test day in the data analysis. As such, three acceptable trials per day per position were recorded for each day and position (Day 1 seated, Day 1 supine, Day 2 seated, and Day 2 supine). The day-to-day reliability of R5 and R20 were determined using Pearson product moment correlation coefficients within each position of the Day 1 trials with the means of the Day 2 trials (seated: Day 1 versus Day 2; supine: Day 1 versus Day 2). Within each test day, the mean of three trials during the seated was compared to the mean of three trials during the supine position for differences by a paired t-test (Day 1: seated versus supine; Day 2: seated versus supine). Percent change from seated to supine (%ch seated to supine) was calculated for each subject ((supine– seated)/seated*100). The independent variable was group (tetraplegia, paraplegia, control), and the dependent variables consisted of the R5, R20, and %ch seated to supine. A two-factor repeated measures ANOVA was used to determine the main and interaction effects for group (tetraplegia, paraplegia, control) and position (seated, supine) on the mean values of three trials for R5, R20, and %ch seated to supine.

To further characterize main and interaction effects, the Scheffe's post hoc test was used to determine differences between the groups. Within each group, %ch seated to supine was tested against the null by one-sample ANOVA. Coefficient of variation percent (CV%) was determined by the standard deviation divided by the mean of the three trials within a test day and by the mean of six trials across both test days for R5 and R20. An a priori level of significance was set at P ≤ 0.05. Statistical analyses were completed using Stat-View 5.0 (SAS Institute, Inc.). Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviations or as a proportion, as appropriate.

Results

Subjects in the three study groups did not differ significantly for age, height, weight, body mass index, and gender (Table 1). Subjects with tetraplegia had a significantly greater DOI than those with paraplegia; a comparable number of subjects in each of the two SCI groups had complete motor injury (Table 1). The level of injury for subjects with tetraplegia ranged from C2 to C7; 5 of 10 subjects previously had a tracheostomy. The injury for subjects with paraplegia ranged from T4 to L2; 3 of 10 previously had a tracheostomy.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study groups

| Tetra | Para | Control | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 10) | (n = 10) | (n = 11) | |

| Age (y) | 41 ± 10 | 36 ± 11 | 38 ± 13 |

| DOI (y) | 19 ± 13* | 8 ± 8 | N/A |

| Height (cm) | 173 ± 8 | 175 ± 8 | 172 ± 9 |

| Weight (kg) | 71.7 ± 16.2 | 80.4 ± 21.9 | 76.1 ± 11.0 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.8 ± 4.7 | 26.1 ± 5.8 | 25.8 ± 3.6 |

| Males/females | 7/3 | 7/3 | 8/3 |

| Complete/incomplete | 8/2 | 8/2 | N/A |

Tetra, tetraplegia; para, paraplegia; control, able-bodied subjects; y, years; cm, centimeters; kg, kilograms; DOI, duration of injury; BMI, body mass index; incomplete/complete, the degree of motor completeness of injury. Values are expressed as mean plus or minus standard deviations.

*P < 0.05 for tetra versus para.

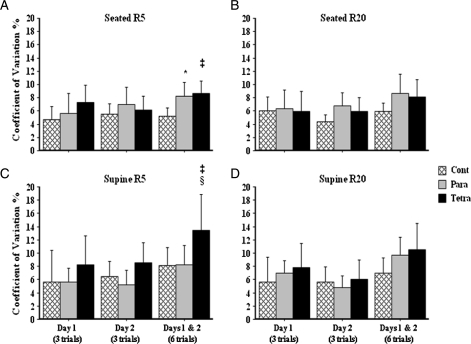

Baseline values and variability

Baseline values for R5 and R20 seated did not differ significantly among the three groups and were highly comparable within group on Day 1 versus Day 2. The same was found for R5 and R20 supine (Table 2). The coefficient of variations obtained on Day 1 and Day 2 was between 4.4 and 8.6% for R5 and R20 in the seated and supine positions, and did not differ significantly among the three groups (Table 2). The coefficient of variations for combined data from Day 1 and Day 2 was significantly higher for R5 in the seated position in subjects with paraplegia and tetraplegia (8.7 ± 2.6 and 8.1 ± 3.7, respectively) compared to that of controls (5.2 ± 1.8), and significantly higher for R5 in the supine position in subjects with tetraplegia (13.4 ± 7.5) compared to that of subjects with paraplegia (8.3 ± 4.0) and controls (8.1 ± 4.0) (Table 2 and Fig. 2). Regardless of position or resistances (e.g. R5 or R20), subjects with tetraplegia had greater variability between Days 1 and 2 compared to that of subjects with paraplegia or controls (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Table 2.

R5 and R20 test–retest and seated to supine comparisons within each group

| Day 1 (three trials) | Day 2 (three trials) | Corr coef (R) | P value | CV% (six trials) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetraplegia | R5 seated | 3.29 ± 0.23 | 3.31 ± 0.21 | 0.60 | 0.06 | |

| R5 seated CV% | 7.3 ± 3.6 | 6.1 ± 3.0 | 8.7 ± 2.6 | |||

| R5 supine | 4.74 ± 0.38 | 5.28 ± 0.43 | 0.62 | 0.05 | ||

| R5 supine CV% | 8.3 ± 6.1 | 8.6 ± 34.2 | 13.4 ± 7.5 | |||

| R5 seated to supine (%ch) | 44 ± 28 | 63 ± 40 | ||||

| R5 seated versus supine (P value) | 0.0007 | 0.0007 | ||||

| R20 seated | 3.20 ± 0.19 | 3.27 ± 0.19 | 0.67 | 0.03 | ||

| R20 seated CV% | 5.9 ± 4.3 | 5.9 ± 3.0 | 8.1 ± 3.7 | |||

| R20 supine | 4.22 ± 0.32 | 4.66 ± 0.27 | 0.60 | 0.06 | ||

| R20 supine CV% | 7.8 ± 5.1 | 6.1 ± 4.0 | 10.6 ± 5.5 | |||

| R20 seated to supine (%ch) | 32 ± 14 | 44 ± 19 | ||||

| R20 seated versus supine (P value) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Paraplegia | R5 seated | 3.74 ± 0.21 | 3.61 ± 0.25 | 0.77 | 0.006 | |

| R5 seated CV% | 5.6 ± 34.3 | 7.0 ± 3.7 | 8.2 ± 3.0 | |||

| R5 supine | 4.51 ± 0.25 | 4.50 ± 0.26 | 0.92 | <0.0001 | ||

| R5 supine CV% | 5.6 ± 32.9 | 5.2 ± 3.1 | 8.3 ± 4.0 | |||

| R5 seated to supine (%ch) | 19 ± 22 | 24 ± 28 | ||||

| R5 seated versus supine (P value) | 0.0244 | 0.0204 | ||||

| R20 seated | 3.37 ± 0.22 | 3.19 ± 0.23 | 0.86 | 0.0007 | ||

| R20 seated CV% | 6.3 ± 4.0 | 6.8 ± 2.8 | 8.6 ± 4.1 | |||

| R20 supine | 4.07 ± 0.27 | 4.03 ± 0.21 | 0.90 | <0.0001 | ||

| R20 supine CV% | 6.9 ± 2.6 | 4.8 ± 2.5 | 9.7 ± 3.8 | |||

| R20 seated to supine (%ch) | 20 ± 22 | 27 ± 26 | ||||

| R20 seated versus supine (P value) | 0.0179 | 0.0094 | ||||

| Control | R5 seated | 3.77 ± 0.17 | 3.75 ± 0.20 | 0.82 | 0.001 | |

| R5 seated CV% | 4.7 ± 2.9 | 5.5 ± 2.4 | 5.2 ± 1.8 | |||

| R5 supine | 4.84 ± 0.25 | 4.72 ± 0.32 | 0.96 | <0.0001 | ||

| R5 supine CV% | 5.7 ± 7.1 | 6.5 ± 3.3 | 8.1 ± 4.0 | |||

| R5 seated to supine (%ch) | 28 ± 21 | 25 ± 18 | ||||

| R5 seated versus supine (P value) | 0.0012 | 0.0010 | ||||

| R20 seated | 3.42 ± 0.21 | 3.41 ± 0.15 | 0.96 | <0.0001 | ||

| R20 seated CV% | 6.0 ± 3.2 | 4.4 ± 1.6 | 5.9 ± 1.9 | |||

| R20 supine | 4.11 ± 0.23 | 4.06 ± 0.23 | 0.95 | <0.0001 | ||

| R20 supine CV% | 5.6 ± 5.5 | 5.6 ± 3.4 | 7.0 ± 3.5 | |||

| R20 seated to supine (%ch) | 22 ± 18 | 20 ± 17 | ||||

| R20 seated versus supine (P value) | 0.0029 | 0.0022 |

R5 and R20, airway resistances at 5 and 20 Hz (cmH2O/l/second); R, correlation coefficient (corr coef) reliability (R) estimate between the means of Days 1 and 2; %ch, percent change seated to supine; CV (%), coefficient of variation expressed as a percent for all six trials from Days 1 and 2. Values are expressed as mean plus or minus standard deviations.

Figure 2.

The coefficient of variation and 95% confidence intervals for within-day and between-day for (A) R5 seated (*P < 0.01 para versus control; ‡P < 0.005 tetra versus control), (B) R20 seated, (C) R5 supine (‡P < 0.05 tetra versus para and §P < 0.05 tetra versus control), and (D) R20 supine.  cont, able-bodied control subjects,

cont, able-bodied control subjects,  para, subjects with paraplegia, and

para, subjects with paraplegia, and  tetra, subjects with tetraplegia.

tetra, subjects with tetraplegia.

Day-to-day reliability

Subjects in the group with tetraplegia had the lowest day-to-day correlation coefficients for seated and supine R5 (R = 0.60, P = 0.06 and R = 0.62, P = 0.05) and R20 (R = 0.67, P = 0.03 and R = 0.60, P = 0.06) (Table 2). Compared to tetraplegia subjects, the paraplegia group had stronger day-to-day correlation coefficients for seated and supine R5 (R = 0.77, P = 0.006 and R = 0.92, P < 0.0001) and R20 (R = 0.86, P = 0.0007 and R = 0.90, P < 0.0001) (Table 2). Whereas, control subjects demonstrated the strongest correlations for seated and supine day-to-day R5 (R = 0.82, P = 0.001 and R = 0.96, P < 0.0001) and R20 (R = 0.96, P < 0.0001 and R = 0.95, P < 0.0001) (Table 2).

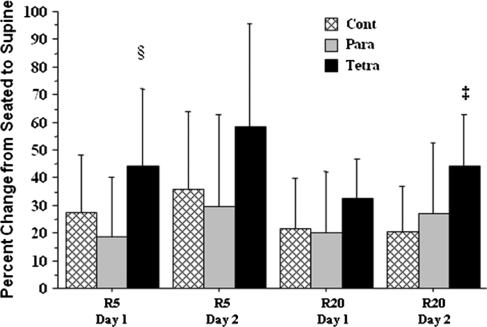

Change in body position

Values for R5 and R20 increased significantly for both test days in the three study groups in the supine position (Table 2). Increases were significantly greater on Day 1 for R5 and on Day 2 for R20 in subjects with tetraplegia compared to subjects with paraplegia and controls (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

The percent change from seated to supine position (mean ± standard deviation) for R5 (§P < 0.05 tetra versus para and controls) and R20 (‡P < 0.01 tetra versus para and controls).  cont, able-bodied control subjects,

cont, able-bodied control subjects,  para, subjects with paraplegia, and

para, subjects with paraplegia, and  tetra, subjects with tetraplegia.

tetra, subjects with tetraplegia.

Discussion

Baseline mean values for R5 and R20 in the seated position were comparable in the three study groups. The findings confirm previous observations and contrast with those obtained employing body plethysmography, which demonstrated that airway resistance was significantly higher in subjects with tetraplegia (i.e. presumably because of heightened vagal tone due to loss of sympathetic innervations of the lungs) compared to subjects with paraplegia or able-bodied controls.12 It is reasonable to assume that IOS lacks the sensitivity of body plethysmography in the assessment of airway caliber in tetraplegia; airway resistance as measured by forced oscillation techniques includes contributions from large and small airways, chest wall, and lung tissue,2 whereas airway resistance quantitated by body plethysmography primarily represents the dynamics of airway caliber. However, previous findings of significant decreases in R5 and R20 among subjects with tetraplegia following inhalation of ipratropium bromide demonstrated that the IOS was a sensitive method for evaluating changes in airway caliber experiments performed over a short period of time.6

Within the three groups, overall, there was fair to good between-day test, re-test reliability for both R5 and R20 with correlation coefficients approaching or being significant for the between-day resistance values for R5 and R20 in both the seated and supine positions for all three groups. Similarly, by assessment of intra-class correlation coefficients using minimal difference values we had found previously that variability of baseline R5 and R20 values was comparable among subjects with tetraplegia, paraplegia, and able-bodied controls.6 In the current study, by use of coefficient of variation, the within-day variability for R5 and R20 in the seated position did not differ significantly among subjects in the three study groups. The within-day coefficient of variation also demonstrates that IOS is more reliable seated than supine in the three study groups. Our current within-day CV findings among subjects in the three study groups are similar to a CV of 7.3 for R5 in clinically stable adolescent asthmatic subjects,13 to a CV of 6.0 for R5, and to 7.4 for R20 in able-bodied individuals.14 However, in the current study, CV for values that were combined Days 1 and 2 demonstrated that R5 in the seated position was significantly higher among subjects with paraplegia and tetraplegia compared to able-bodied controls, and that R5 in the supine position was significantly higher in subjects with tetraplegia compared to subjects with paraplegia or able-bodied controls. Our findings in able-bodied individuals were very similar to those reported by Houghton et al.14 (5.2 and 5.9 for R5 and R20, respectively). These studies demonstrate that variability of with-in day IOS parameters in subjects with SCI is comparable to that of able-bodied individuals, whereas greater variability of between-day R5 and R20 values suggests that IOS may be of more limited usefulness for long-term studies interventional studies in subjects with SCI.

To perform IOS requires minimal physical demands on the patient. However, the operator must review each test immediately to ensure adequate recording time that is free of artifacts, which may include swallowing, coughing, or discomfort from the mouthpiece or nose clip. The mouthpiece must be supported at a position to ensure maintenance of a relaxed head and neck posture. Additional attention is required for subjects with SCI to assure that they are comfortably relaxed in a constant-supported body position. During the course of the current study only three subjects, all of whom had high tetraplegia, needed to repeat a 90-second trial because of artifacts; among these three individuals, valid results were achieved during five 90-second trials, all of which were well tolerated by the subjects. We used coherence values of ≥0.7 for 5 Hz and ≥0.9 for 20 Hz for either five breaths or 30 seconds of recording time. The coherence function is defined as the square of the cross-power spectrum divided by the product of the auto-spectra of pressure and flow at the forcing frequency.2 Coherence value thresholds established for FOT are not applicable to IOS, because IOS commonly includes the average of over 100 separate analyses.2,15 Accordingly, less perfect coherence is required for IOS data to provide an estimated standard error of <10%.2 For clinical assessment of pulmonary resistance using IOS, a coherence value of ≥0.6 is recommended for R5 and ≥0.9 for frequencies greater than 10 Hz.

We observed a greater percentage increase in R5 and R20 in the supine position in subjects with tetraplegia as compared to subjects with paraplegia and able-bodied controls. The increase in airway resistance among supine able-bodied individuals has been attributed to a positional decrease in functional residual capacity (FRC).10,16,17 A similar explanation may be applicable to subjects with tetraplegia, who despite demonstrating an increase in forced vital capacity in the supine position, in contrast to a decrease among able-bodied individuals, demonstrated a decrease in FRC in the supine position comparable to that found about able-bodied individuals.18 Several studies have demonstrated that reductions in chest wall and lung compliance, both of which are associated with tetraplegia, do not affect respiratory resistance values.19–22 Additional factors that may contribute to heightened supine respiratory resistance in subjects with tetraplegia may include poor coordination between respiratory and pharyngeal dilator muscles,23 thickening of the oropharyngeal wall through unopposed parasympathetic stimulation of mucosal walls,24 and a decrease in upper airway patency due to an increase and/or redistribution of fat tissue and associated regional loss of lean tissue.25

Conclusion

In healthy subjects and those with airway obstruction, IOS is a reliable method for the evaluation of airway function. In persons with SCI, IOS appears to have applicability to the study of respiratory resistances that are performed on the same day (e.g. within day). However, interpretation of data obtained over several days or months (e.g. between day) may be more difficult because of greater variability of residual volume values compared to able-bodied individuals. Future prospective investigations in a larger cohort are needed to detect small differences that could not be detected in this study due to measurement variability. To account for differences in sympathetic tone and subsequent airway resistance, studies should stratify subjects by level of lesion as well as incorporate body box plethysmography measurements to validate the postural changes in airway resistance by IOS.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank The James J. Peters Medical Center, Bronx, NY, The Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development Service, and Kessler Institute for Rehabilitation for their support. This work was funded by a clinical SCI Grant (#208) from United Spinal Association.

References

- 1.Oostveen E, MacLeod D, Lorino H, Farre R, Hantos Z, Desager K, et al. The forced oscillation technique in clinical practice: methodology, recommendations and future developments. Eur Respir J 2003;22(4):1026–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith HJ, Reinhold P, Goldman MD. Forced oscillation technique and impulse oscillometry. Eur Respir Monograph 2005;31(chapter 5):72–105 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldman MD, Saadeh C, Ross D. Clinical applications of forced oscillation to assess peripheral airway function. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2005;148(1–2):179–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashba J, Garshick E, Tun CG, Lieberman SL, Polakoff DF, Blanchard JD, et al. Spirometry-acceptability and reproducibility in spinal cord injured subjects. J Am Paraplegia Soc 1993;16(4):197–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelley A, Garshick E, Gross ER, Lieberman SL, Tun CG, Brown R. Spirometry testing standards in spinal cord injury. Chest 2003;123(3):725–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Radulovic M, Schilero GJ, Wecht JM, Weir JP, Spungen AM, Bauman WA, et al. Reversibility of airflow obstruction in spinal cord injury: evidence for functional sympathetic innervation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008;89(12):2349–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navajas D, Farre R, Rotger MM, Milic-Emili J, Sanchis J. Effect of body posture on respiratory impedance. J Appl Physiol 1988;64(1):194–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yap JCH, Watson RA, Gilbey S, Pride NB. Effects of posture on respiratory mechanics in obesity. J Appl Physiol 1995;79(4):1199–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson RA, Pride NB. Postural changes in lung volumes and respiratory resistance in subjects with obesity. J Appl Physiol 2005;98(2):512–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duggan CJ, Watson RA, Pride NB. Postural changes in nasal and pulmonary resistance in subjects with asthma. J Asthma 1994;41(7):695–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao J, Que C, Wang G, He B. Effect of posture on airway resistance in obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome by means of impulse oscillation. Respiration 2009;77(1):38–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schilero GJ, Grimm DR, Bauman WA, Lenner R, Lesser M. Assessment of airway caliber and bronchodilator responsiveness in subjects with spinal cord injury. Chest 2005;127(1):149–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldman MD, Carter R, Klein R, Fritz G, Carter B, Pachucki P. Within- and between-day variability of respiratory impedance, using impulse oscillometry in adolescent asthmatics. Pediatr Pulmonol 2002;34(4):312–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houghton CM, Woodcock AA, Singh D. A comparison of plethysmography, spirometry and oscillometry for assessing the pulmonary effects of inhaled ipratropium bromide in healthy subjects with patients with asthma. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2004;59(2):152–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hellinckx J, Cauberghs M, De Boeck K, Demedts M. Evaluation of impulse oscillation system: comparison with forced oscillation technique and body plethysmography. Eur Respir J 2001;18(3):564–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linderholm H. Lung mechanics in sitting and horizontal postures studies by body plethysmographic methods. Am J Physiol 1963;204:85–91 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van den Elshout FJJ, van de Woestijne KP, Folgering HTM. Variations of respiratory impedance with lung volume in bronchial hyperreactivity. Chest 1990;98(2):358–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCool FD, Brown R, Jayewski RJ, Hyde RW. Effects of posture on stimulated ventilation in quadriplegia. Am Rev Respir Dis 1988;138(1):101–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Estenne M, De Troyer A. The effects of tetraplegia on chest wall statics. Am Rev Respir Dis 1986;134(1):121–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scanlon PD. Respiratory mechanics in acute quadriplegia. Lung and chest wall compliance and dimensional changes during respiratory maneuvers. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989;139(3):615–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Noord JA, Van de Woestijne KP, Demedts M. Total respiratory resistance and reactance in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and kyphoscoliosis. Eur Respir J 1991;4(8):945–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van den Elshout FJJ, van Herwaarden CLA, Folgering HTM. Oscillatory respiratory impedance and lung tissue compliance. Respir Med 1994;88(5):343–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cahan C. Arterial oxygen saturation over time and sleep studies in quadriplegic patients. Paraplegia 1993;31(3):172–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wasicko MJ. The role of vascular tone in the control of upper airway collapsibility. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990;141(6):1569–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spungen AM, Wang J, Pierson RN, Jr, Bauman WA. Soft tissue body composition differences in monoozygotic twins discordant for spinal cord injury. J Appl Physiol 2000;88(4):1310–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]