Abstract

Great strides have been made in reducing morbidity and mortality following spinal cord injury (SCI), and improving long-term health and community participation; however, this progress has not been uniform across the globe. This review highlights differences in global epidemiology of SCI and the ongoing challenges in meeting the needs of individuals with SCI in the developing world, including post-disaster. Significant disparities persist, with life expectancies of 2 years or less not uncommon for persons living with paraplegia in many developing countries. The international community has an important role in improving access to appropriate care following SCI worldwide.

Keywords: Developing countries, Disasters, Earthquake, Disability, Rehabilitation, International cooperation, Spinal cord injuries, Paraplegia, Tetraplegia, Wheelchair, Pressure ulcer, World health, Armenia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Haiti, Iran, Sierra Leone, India

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a devastating, life-altering injury, and a challenge for clinicians to treat under ideal circumstances. Until World War II, persons with severe SCI routinely died within the first couple of years of injury.1 While outcomes have improved considerably for individuals with SCI in many developed, industrialized nations, the reality is very different in the majority of the world. Managing acute SCI, providing comprehensive rehabilitation, and ensuring adequate supports to allow community reintegration are resource-intensive endeavors. We discuss how the epidemiology of SCI differs between high- and low-resource nations, the challenges associated with providing comprehensive care in low-resource environments, and the obstacles faced when disasters occur in such settings. SCI experts have a critical role in addressing and eliminating the persistent gap between developing and developed nations. Meeting this challenge will require a concentrated and conscious effort, incorporating creativity, and dedication, in order to adapt current approaches to the global reality.

Differences in the demographics of SCI worldwide

Reliable information on the epidemiology for traumatic SCI is unavailable for much of the globe. Despite this, it is clear that incidence, prevalence, and injury etiology vary considerably from region to region, and some trends are apparent. Cripps et al2 recently performed a comprehensive review of global epidemiology for traumatic SCI and noted prevalence rates ranging from 236 to 1009 per million. Data on incidence are predominantly from developed regions, including North America (39 per million), Western Europe (16 per million), and Australia (15 per million), where four-wheeled motor vehicle accidents are the leading etiology. In comparison, two-wheeled accidents (e.g. motorcycles) predominate in Southeast Asia and falls from rooftops and trees are the most common injury etiology in Southern Asia and Oceania. Falls on level ground are an important injury etiology in regions with older populations, such as Japan (42%) and Western Europe (37%). Traumatic SCI due to violence is more common in the developing regions of sub-Saharan Africa (38%), north Africa/Middle East (24%), and Latin America (22%), with North America (15%) having relatively high rates when compared with similar resource-rich, developed regions. In general, traffic accidents are the leading cause of injury in developed nations, while falls are the leading cause in developing countries.3 The World Health Organization (WHO) has previously predicted that SCIs due to motorized vehicles will increase in the foreseeable future for developing countries, as usage increases in urban and rural areas.4 Men are more prone to SCI in all countries, although the reported gender ratios vary considerably – 1.73 in China to 7.55 in Pakistan.3 In resource-rich countries, the majority of individuals survive the first year post-injury; however, there is a large discrepancy in observed mortality between resource-rich and resource-poor environments. In one study of 24 subjects from Sierra Leone, 7 individuals died during the initial hospitalization, 8 individuals were dead at follow-up (average 17.4 months), and 4 were lost to follow-up.5 Of the five survivors, two had incomplete injuries and were ambulatory. A recent review reported a two-fold difference between the highest-reported mortality rate in a developing country (17.5 annual deaths attributable to SCI per million people in Nigeria) vs. that in a developed country (8 annual deaths attributable to SCI per million people in Canada).3

The challenges of SCI in developing and resource-poor environments

Acute injury and evaluation

Disparities between the developing and developed worlds capacity to deliver emergency and acute care are evident immediately following a SCI. In many low-resource regions, it is rare for an individual with an acute SCI to be immobilized in the field and transported by trained personnel (e.g. ambulance).6–9 In the setting of an unstable spine, this can lead to further neurological compromise. In one study of 83 subjects from Pakistan, none were immobilized at the accident site and only 18 were transported by ambulance.10 Delays are common between the initial injury and presentation for specialized care, even when it is available. One study from India found an average 45-day delay between injury and presentation to a spinal unit, primarily due to a lack of knowledge by health care providers that such units existed.8 In the Sierra Leone study, 5/7 patients who died in hospital had been referred from other hospitals with an average delay of 17 days (range 3–42 days) post-injury.5

While persons with thoracic and lumbar injuries in developing countries have poorer first year survival than those with similar injuries in developed countries, persons with cervical SCI are even less likely to survive the initial injury and/or hospitalization in developing and resource poor regions.6,7,11 This is reflected in few surviving individuals presenting with cervical SCI, compared to the number in resource-rich regions. A Pakistan study reported that 49 of 83 persons (71.1%) initially treated at a rehabilitation center were paraplegic, and only 4 (4.8%) had complete tetraplegia.10

Medical management and secondary complications

Pressure ulcers are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in resource-poor environments. In the Pakistani study above, 33 (39.7%) of 83 individuals had pressure ulcers at rehabilitation admission10. Twenty-six of 42 earthquake victims admitted to a spinal injuries unit following the 1998 Armenian earthquake had stage 3–4 pressure ulcers.12 In a Nigerian study, 60% of individuals with SCI developed pressure ulcers during their initial hospitalization.13 Even more concerning is what often occurs following community reintergration. In the study from Sierra Leone, one of Africa's poorest countries, 17 of 24 individuals survived to hospital discharge, after which an additional 8 persons died in the community (four individuals were lost to follow-up).5 All eight persons who died in the community had wounds described as ‘big’ and/or ‘deep’. In comparison with these observations from developing nations, a study utilizing data from the U.S. National Spinal Cord Injury Database revealed a pressure ulcer prevalence of 11.5% 1 year post-injury increasing to 21% 15 years post-injury.14

Fortunately, experience following the 2010 earthquake in Haiti has shown that even the most severe wounds do not require expensive, technology-driven treatments, but can heal with meticulous attention to nutrition, hygiene, and attentive wound care.15 Stage IV pressure ulcers and surgical wounds with exposed hardware healed with regular gauze dressing changes with normal saline, judicious application of diluted povidine–iodine to exposed metal, and the provision of balanced, protein-rich meals. Antibiotics were not required.

Strategies for bowel and bladder management utilized in developed nations often have to be adapted in developing nations. This includes alternative methods (e.g. diluted bleach) for cleaning and reusing urinary catheters, which are expensive and cannot be readily or routinely obtained and replaced. Intermittent catheterization remains the preferred management of neurogenic bladder dysfunction; however, in some cultures individuals can be extremely resistant to this technique.7 Practices that have fallen out of favor in developed nations, such as Crede's maneuver, persist in developing nations (e.g. Pakistan).16

The realities of daily living preclude a structured bowel program in many parts of the world. In rural regions, able-bodied individuals may simply go into the fields to attend to bowel needs.16 Even when toileting facilities are present they are often inappropriate for individuals with SCI. An example would be fixed in-ground commodes (squat toilets) common in many parts of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa; these require the individual to squat on bent knees over an opening level with the ground.16 Social beliefs, such as an expectation by family members to care for the individual with impairment, can discourage independence.16,17 Under these circumstances, chronic fecal incontinence is quite common – 86% of individuals reported regular or occasional incontinence in a study from Pakistan.16

Medical equipment

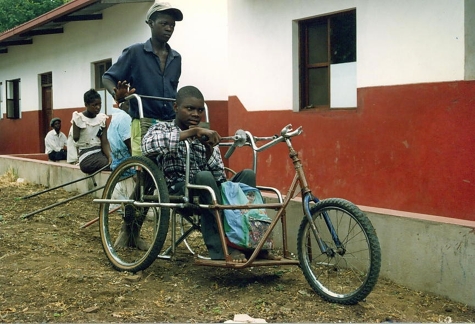

Prescribed equipment needs to be practical, durable, and reparable; ideally by the injured individual or family. If self-repair of equipment is not practical, the injured individual should have an identified local resource to access for equipment-related issues, otherwise it is not uncommon for still-useful equipment to be discarded. Individuals and local communities often devise their own adaptive aids and mobility devices from available resources (Fig. 1). Wheelchairs are particularly problematic, as designs utilized in developed nations are typically not appropriate for rugged, unpaved rural environments.7 In the aftermath of the 2010 Haiti earthquake, wheelchairs were successfully dispensed that were specifically designed for such environments (e.g. RoughRider wheelchair, Whirlwind Wheelchair International, San Francisco, CA, USA).18 Technology-intensive equipment can be prone to damage as well as difficult to repair and maintain, and therefore should be minimized when possible. In Iran, few of the patients who received Roho cushions knew how to inflate them properly.17

Figure 1.

Hand-cycle wheelchair in Mozambique. A young man with paraplegia had to stop attending school after the chain in the arm cycle broke, and replacement parts were unavailable.

Cost of equipment is also important. Low-cost options for vital equipment (e.g. pressure-relieving wheelchair cushions) can potentially offer comparable performance and durability to high-cost alternatives.19,20 Unfortunately, awareness of and access to these alternatives are limited. In collaboration with national governments, non-profit local and international organizations must take ownership and lead such initiatives, as there is little motivation for private industry involvement given the low profit margins.

Cultural issues, community reintegration, and follow-up

Depending on the cultural setting, counseling injured individuals about the nature of their injury and the accompanying prognosis can be very challenging.18 This is particularly true in the absence of local and culturally relevant supportive counseling and psychological services. There is often reluctance to accept the permanence of severe injuries,10 and many individuals seek alternative treatments such as spiritual and faith healers.10,21

Following hospitalization and rehabilitation, individuals with SCI are often confronted with harsh terrains, and inaccessible homes and communities. This can be complicated further by societal attitudes which devalue individuals with significant disabilities. In many developing countries, individuals rely on their physical abilities to provide for self and family, often through manual labor such as farming. A physical disability significantly reduces one's survival advantage, and a person with a disability can be seen as another mouth to feed, while not contributing to the sustenance of the family. These circumstances can render the affected individual a virtual prisoner in his or her home, with complete reliance on family and friends. Achieving adequate follow-up can also be challenging. Following the 2003 earthquake in Bam, Iran, Raissi et al17 were able to successfully locate 61 of 121 individuals 8 months post-event. In a report from Nigeria, only 3% of wheelchair-bound individuals kept their initial follow-up appointment after discharge, and by the second appointment, the rate had dropped further to 1.5%.21

When accessibility and transportation are significant barriers (Fig. 2), mobile teams can play an important role in ensuring proper follow-up and maintaining long-term health.11,22 These teams can visit individuals in their homes and communities, and are being utilized in Haiti following the January 2010 earthquake. Prabhaka and Thakker22 described an effort to reach people in rural villages in India, which they called the Paraplegia Safari. Despite this, patients lost to follow-up remained high – 282 of 787 (35.8%). Encouraging and facilitating the development of peer support networks and groups might also improve community reintegration and long-term well-being, by fostering a sense of community and preventing isolation.

Figure 2.

Hilly terrain in a wheelchair inaccessible community in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Courtesy of Fiona Stephenson.

Some developing nations have developed specialized facilities. The Armed Forces Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine (AFIRM) in Rawalpindi, Pakistan is a 100-bed tertiary care referral institute.10 AFIRM is managed by specialists in physical medicine and rehabilitation along with teams of allied health professionals. Although it caters to armed forces personnel, services are available to civilians for a nominal charge. Establishing dedicated rehabilitation facilities can clearly make a difference. In Zimbabwe, where 90% of individuals with tetraplegia or paraplegia died within 1 year of discharge, half of individuals survived 1 year following the establishment of a National Rehabilitation Centre.7 Part of this success could be contributed to the inclusion of family members in the rehabilitation process. The facility made available short-term housing for patients' families, so that they could be trained and educated about caring for their injured relatives.

SCI in the context of a disaster

The challenges associated with providing care in resource-poor environments have been highlighted above. Unfortunately, these challenges are magnified several fold when developing nations are confronted with the immediate and long-term aftermath of a natural disaster.

Extrication and initial presentation

Prolonged extrication times and delays in appropriate medical evaluation are common. Following the May 12, 2008 8.0-magnitude earthquake in the Sichuan region of southwestern China, the mean extrication time for people with spinal injuries trapped under rubble was 12.2 hours, and the time to hospital referral was 3.6 days.23 Spinal immobilization is rare in the post-disaster setting, and victims are typically pulled from rubble by family, friends, and neighbors.18

The majority of observed injuries in the aftermath of earthquakes involve the low thoracic or lumbar spine.17,18,23–25 Cervical injuries are uncommon. Although the precise reasons are unclear, it has been theorized that this may reflect poor initial survival. Contributing factors could include a requirement for ventilator support (even transient), and associated upper-body and chest injuries. After the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, 10.9% of spinal injuries presenting to a hospital for initial care were cervical.23 In a report following the 2005 Kashmir, Pakistan earthquake, only 3% of SCIs involved cervical levels.24 Forty-two earthquake victims were admitted to a newly established spinal injuries unit following the 1988 earthquake in Armenia, all with paraplegia.12 In the aftermath of the 2010 Haiti earthquake, only 1 of 19 individuals cared for at a facility in northern Haiti had a cervical SCI.18 High thoracic injuries are also encountered less due to accompanying internal injuries that can impact on survival.18

Multi-level spinal injuries are also seen with greater frequency, along with other injuries. Twenty-nine percent of spinal injuries were multi-level following the 2008 Sichuan China earthquake,23 and extremity fractures, pelvic fractures, head trauma, and internal trauma were commonplace.

For individuals who survive the acute period with a cervical SCI, long-term survival is dismal. A follow-up study of individuals from the October 2005 Pakistani earthquake reported that few, if any, individuals with tetraplegia had survived.26 Another study assessed outcomes following the 2003 earthquake in Bam, Iran. Of the 103 subjects located for follow-up (2005–2006), only 2 (1.9%) had cervical injuries.25

In comparison with the typical male predominance, a relatively large proportion of injuries have affected women following some disasters. Greater than 50% of the injuries evaluated from the 2003 Bam, Iran earthquake affected women.11 Approximately 60–75% of patients following the 2005 Kashmir, Pakistan earthquake were women.24,27 It has been suggested that this might be due to the fact that many injuries occur in poorly constructed homes that collapse, as opposed to behavioral and occupational risk factors that disproportionately affect men.28

Cohorting and establishing systems of care

Cohorting individuals at identified centers can facilitate staff training, which otherwise can be fragmented, and help procure required resources since there is an identifiable entity.27 SCI centers have been successfully established following disasters such as the 1988 Armenian earthquake,12 the 2005 Pakistan earthquake,27 and 2010 Haitian earthquake.18

In some instances the attention brought to SCI, in the context of a natural disaster, has led to positive and persistent changes in capacity. The 1988 earthquake in Armenian led to the establishment of a permanent spinal injuries unit in 1992.12 Two spinal units were established in Pakistan following the 2005 earthquake – National Institute for Handicapped and Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences Satellite Hospital at National Institute of Health.26 The 2010 Haiti earthquake has led to the establishment of three main facilities providing inpatient SCI care and rehabilitation – Haiti Hospital Appeal in Cap Haitien (northern Haiti), Project Medishare in Port-au-Prince (central Haiti), and St Boniface Hospital in Fond-des-Blancs (southern Haiti).18 Interestingly, more individuals are now surviving in Haiti with SCI from other causes such as traffic accidents and falls, resulting in the need for long-term capacity development including dedicated resources for SCI.

The role of the international community

A damning criticism in the aftermath of the 2005 Pakistan earthquake was the conspicuous absence of rehabilitation societies and western physicians in both the acute and rehabilitation phases.26 This was contrasted to the widespread international involvement of physical and occupational therapists.

International and professional organizations (e.g. Academy of Spinal Cord Injury Professionals (ASCIP), International Spinal Cord Society (ISCOS), International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (ISPRM), WHO, Handicap International, Red Cross, Medecins Sans Frontieres, etc.) and physicians, specifically, can make an invaluable contribution by providing training opportunities, both locally and internationally. Training opportunities are particularly important in the aftermath of a disaster, and efforts should focus on long-term capacity building. Local experts must be identified and then supported to both provide clinical care and institutional leadership. Regional workshops, such as those offered by ISCOS, have been rated as very helpful by participants.29 The international community can also contribute by providing advanced training opportunities and rotations at established SCI centers around the world, as well as financially supporting attendance at appropriate international conferences and meetings. Efforts such as this were central to the establishment of the Armenian center12 as well as centers in Haiti.18 In the aftermath of the Haiti earthquake, the ASCIP sponsored attendance for a Haitian physiatrist at the 2010 annual conference, and the Swiss Paraplegic Centre in Nottwil, Switzerland arranged site visits to their facility. Contributions like this are invaluable.

Long-term support and commitment, in partnership with local organizations and governments, are essential. Since 2003, Handicap International Belgium has been supporting the set-up of seven SCI units in Vietnam with the Vietnamese Ministry of Health.30 Healing Hands for Haiti administers a follow-up clinic for individuals with SCI in Port-au-Prince, organizes monthly peer support groups, provides SCI-specific literature in French and Creole, dispenses SCI-specific medications, and conducts ongoing staff training. Their focus remains on care being delivered by Haitian therapists, doctors, and nurses, with international experts assisting in providing ongoing training opportunities and financial support. ISCOS has established a disaster relief committee and partnered with the WHO for the stated goal of improving SCI management in low- and middle-income countries.31 In June 2011, the ISPRM held a Symposium on Rehabilitation Disaster Relief at their 6th World Congress in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Conclusion

Significant advances over the past 50 years have been made in decreasing morbidity and mortality following SCI and improving long-term health and quality-of-life outcomes for persons with SCI. Unfortunately, these advances have not impacted on the majority of persons affected by SCI – those living in low-resourced or developing regions of the world. Such disparities are compounded when disaster strikes. The international community has an important role to play in advancing the outcomes for all who sustain SCIs.

References

- 1.Bedbrook GM. The development and care of spinal cord paralysis (1918 to 1986). Paraplegia 1987;25(3):172–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cripps RA, Lee BB, Wing P, Weerts E, Mackay J, Brown D. A global map for traumatic spinal cord injury epidemiology: towards a living data repository for injury prevention. Spinal Cord 2011;49(4):493–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiu W, Lin H, Lam C, Chu S, Chiang Y, Tsai S. Review paper: epidemiology of traumatic spinal cord injury: comparisons between developed and developing countries. Asia Pac J Public Health 2010;22(1):9–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization World report on road traffic injury prevention. Geneva Switzerland: WHO Publications; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gosselin RA, Coppotelli C. A follow-up study of patients with spinal cord injury in Sierra Leone. Int Orthop 2005;29(5):330–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwegbu CG. Traumatic paraplegia in Zaria, Nigeria: the case for a centre for injuries of the spine. Paraplegia 1983;21:81–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy LF, Makarawo S, Madzivire D, Bhebhe E, Verbeek N, Parry O. Problems, struggles and some success with spinal cord injury in Zimbabwe. Spinal Cord 1998;36(3):213–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pandey VK, Nigam V, Goyal TD, Chhabra HS. Care of post-traumatic spinal cord injury patients in India: an analysis. Indian J Orthop 2007;41(4):295–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahidjo KA, Olayinka SA, Ayokunle O, Mustapha AF, Sulaiman GAA, Gbolahan AT. Prehospital transport of patients with spinal cord injury in Nigeria. J Spinal Cord Med 2011;34(3):308–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rathore MF, Hanif S, Farooq F, Ahmad N, Mansoor SN. Traumatic spinal cord injuries at a tertiary care rehabilitation institute in Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc 2008;58(2):53–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raissi GR. Earthquake and rehabilitation needs: experiences from Bam, Iran. J Spinal Cord Med 2007;30(4):369–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke DC, Brown D, Hill V, Balian K, Araratian A, Vartanian C. The development of a spinal injuries unit in Armenia. Paraplegia 1993;31:168–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obalum DC, Giwa SO, Adekoya-Cole TO, Enweluzo GO. Profile of spinal injuries in Lagos, Nigeria. Spinal Cord 2009;47(2):134–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y, DeVivo MJ, Jackson AB. Pressure ulcer prevalence in people with spinal cord injury: age-period-duration effects. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005;86:1208–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stephenson FJ. Simple wound care facilitates full healing in post-earthquake Haiti. J Wound Care 2011;20(1):5–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yasmeen R, Rathore FA, Ashraf K, Butt AW. How do patients with chronic spinal injury in Pakistan manage their bowels? A cross-sectional survey of patients. Spinal Cord 2010;48(12):872–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raissi GR, Mokhtari A, Mansouri K. Reports from spinal cord injury patients eight months after the 2003 earthquake in Bam, Iran. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2007;86(11):912–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burns AS, O'Connell C, Landry MD. Spinal cord injury in postearthquake Haiti: lessons learned and future needs. PM R 2010;2(8):695–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guimaraes E, Mann WC. Evaluation of pressure and durability of a low-cost wheelchair cushion designed for developing countries. Int J Rehabil Res, 2003;26(2):141–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ooi AL, Julia PE. The use of unconventional pressure redistributing cushion in spinal cord injured individuals. Spinal Cord 2011. (advance online publication) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nwadinigwe CU, Iloabuchi TC, Nwabude IA. Traumatic spinal cord injuries (SCI): a study of 104 cases. Niger J Med 2004;13(2):161–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prabhaka MM, Thakker TH. A follow-up program in India for patients with spinal cord injury: paraplegia safari. J Spinal Cord Med 2004;27(3):260–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen R, Song Y, Kong Q, Zhou C, Liu L. Analysis of 78 patients with spinal injuries in the 2008 Sichuan, China, earthquake. Orthopedics 2009;32(5):322–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tauqir SF, Mirza S, Gul S, Ghaffar H, Zafar A. Complications in patients with spinal cord injuries sustained in an earthquake in Northern Pakistan. J Spinal Cord Med 2007;30:373–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karamouzian S, Saeed A, Ashraf-Ganjouei K, Ebrahiminejad A, Dehghani MR, Asadi AR. The neurological outcome of spinal cord injured victims of the Bam earthquake, Kerman, Iran. Arch Iran Med 2010;13(4):351–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rathore MF, Farooq F, Butt AW, Gill ZA. An update on spinal injuries in October 2005 earthquake in Pakistan. Spinal Cord 2008b;46(6):461–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butt BA, Bhatti JA, Manzoor MS, Malik KS, Shafi MS. Experience of makeshift spinal cord injury rehabilitation center established after the 2005 earthquake in Pakistan. Disaster Med Public Health Preparedness 2010;4(1):8–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Priebe MM. Spinal cord injuries as a result of earthquakes: lessons from Iran and Pakistan. J Spinal Cord Med 2007;30(4):367–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kovindha A, Dollfus P. Workshop on spinal cord injuries (SCI) management: the Chiang Mai experience. Spinal Cord 1999;37(3):218–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weerts E, Wyndaele JJ. Accessibility to spinal cord injury care worldwide: the need for poverty reduction. Spinal Cord 2011;49(7):767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.International Spinal Cord Society History of the international spinal cord society. Topics Spinal Cord Rehabil 2011;16(suppl 1):foreword [Google Scholar]