Abstract

Background

Proteus syndrome is a rare overgrowth disorder that almost always affects the skin.

Objective

Our purpose was to evaluate progression of skin lesions in patients with Proteus syndrome.

Methods

Skin findings were documented in 36 patients with Proteus syndrome. Progression of skin lesions in 16 of these patients was assessed by comparing photographs obtained on repeat visits for an average total duration of 53 months.

Results

The skin lesion most characteristic of Proteus syndrome, the cerebriform connective tissue nevus showed progression in 13 children but not in 3 adults. The cerebriform connective tissue nevus progressed by expansion into previously uninvolved skin, increased thickness, and development of new lesions. Lipomas increased in size and/or number in 8/10 children with lipomas. In contrast, epidermal nevi and vascular malformations generally did not spread or increase in number.

Limitations

Only 3 adults with Proteus syndrome were evaluated longitudinally.

Conclusion

The cerebriform connective tissue nevus in Proteus syndrome grows throughout childhood but tends to remain stable in adulthood.

Keywords: Proteus syndrome, cerebriform connective tissue nevus, overgrowth, progression

INTRODUCTION

Proteus syndrome is a rare overgrowth disorder affecting multiple tissues including bone, soft tissue, and skin. The syndrome was described by Cohen and Hayden in 19791 and given its current name by Wiedemann et al2 in 1983. As of October 2004, there were fewer than 100 published cases fulfilling current diagnostic criteria world-wide3. Diagnosis is made by evidence of three mandatory general criteria, including sporadic occurrence, mosaic distribution of lesions and progressive course. These must be accompanied by specific criteria, several of which comprise skin lesions4. The cerebriform connective tissue nevus (CCTN) is one of the most characteristic skin findings. It commonly occurs on the soles of the feet, and frequently causes problems because of pain, pruritus, infection, bleeding, exudation, odor, and walking impairment.5 Patients without a CCTN may be diagnosed based on the presence of other specific features, but it is typical for a patient to have a CCTN and one or more additional skin findings, such as linear verrucous epidermal nevus, dysregulated adipose tissue (lipomas and/or lipohypoplasia), and/or vascular malformations (capillary, venous, lymphatic, and mixed). Other skin abnormalities, not part of the diagnostic criteria but nonetheless associated with Proteus syndrome, include hyper- or hypopigmented macules, patches of dermal hypoplasia, localized hypertrichosis, thick or thin nails, and patches of lighter scalp hair color.6

Progression is a mandatory feature for the diagnosis of Proteus syndrome, but little is known about the natural history of the skin lesions, whether different lesions progress at different rates, and whether the rate of progression is affected by age. In an earlier study, we assessed the progression of skin lesions using a questionnaire. Most patients or their caregivers reported progressive growth in the CCTN and subcutaneous lipomas, whereas the linear verrucous epidermal nevus and vascular malformations tended not to spread to new areas.5 In the current study we used serial photographs in order to study changes in the extent of skin lesions.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Thirty-six patients were evaluated at the National Institutes of Health after enrolling in protocol 94-HG-0132. They met diagnostic criteria for Proteus syndrome as listed in Table 1. Each patient had a complete skin examination and documentation of lesions by photography. Skin manifestations of some patients were reported previously.5, 6 Sixteen patients were included in the longitudinal study as they had two or more visits at least 6 months apart with repeat photographs. Photographs were evaluated retrospectively for interval changes, using a semi-quantitative scale for the connective tissue nevus (Table 2). Change in the CCTN score over time was estimated using a mixed linear regression model with patient-specific random intercepts. The age and status (adult or child) and their interaction were included in the model as fixed effects. The Mixed Model Analysis module in SPSS software version 14 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL) was used to estimate the model.

Table 1.

Diagnostic Criteria for Proteus Syndrome

| General Criteria: Mosaic distribution of lesions, sporadic occurrence, and progressive course Specific Criteria (either A, two from B, or three from C): | |||

| A. | Cerebriform connective tissue nevus | ||

| B. | 1. Linear epidermal nevus | ||

| 2. Asymmetric, disproportionate overgrowth (One or more) | |||

| a. Limbs | |||

| b. Hyperostosis of skull or external auditory canal | |||

| c. Megaspondylodysplasia | |||

| d. Viscera: spleen or thymus | |||

| 3. Specific tumors before 2nd decade: bilateral ovarian cystadenoma or parotid monomorphic adenoma | |||

| C. | 1. Dysregulated adipose tissue (One or both) | ||

| a. Lipomas | |||

| b. Regional lipohypoplasia | |||

| 2. Vascular malformation (One or more) | |||

| a. Capillary | |||

| b. Venous | |||

| c. Lymphatic | |||

| 3. Lung cysts | |||

| 4. Facial phenotype: dolichocephaly, long face, down slanting palpebral fissures and/or mild ptosis, low nasal bridge, wide or anteverted nares, and open mouth at rest | |||

Table 2.

Cerebriform Connective Tissue Nevus Scoring System*

| Palms and/or soles: | |

| None | 0 |

| <50% surface area | +1 |

| 50–75% surface area | +2 |

| >75% surface area | +3 |

| Additional involvement of: | |

| Digits | +1 (per extremity) |

| Lateral sole or palm | +1 (per extremity) |

| Other cutaneous surface | +1 |

| Progression (assessed on return visits) | |

| Spread | |

| Digits | +1 (per extremity) |

| Lateral sole or palm | +1 (per extremity) |

| Thickness | +1 (per extremity) |

Points were tallied for each extremity. Progression was measured by changes in area of involvement on palms and soles plus points for spread and increased thickness of the CCTN.

RESULTS

The patients included 14 females and 22 males with age of first visit ranging from 1 to 56 years (mean age 14 ± 13 years). Skin lesions associated with Proteus syndrome were observed in all patients (Table 3). The frequencies of these lesions were similar to those previously reported.6

Table 3.

Skin Findings in 36 patients with Proteus syndrome.

| Skin Lesion | Subtype or Location |

Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connective Tissue Nevus | Feet | 34 | 94% |

| Hands | 10 | 28% | |

| Other | 4 | 11% | |

| Total | 35 | 97% | |

| Epidermal Nevus | 25 | 69% | |

| Cutaneous Vascular Malformations | Capillary | 17 | 47% |

| Venous | 21 | 58% | |

| Lymphatic | 2 | 6% | |

| Cap/Ven | 6 | 17% | |

| Total | 32 | 89% | |

| Dysregulated Adipose Tissue | Lipoma | 28 | 78% |

| Lipohypoplasia | 9 | 25% | |

| Dermal Hypoplasia | 8 | 22% | |

| Localized Hypertrichosis | 14 | 39% | |

| Patchy light scalp hair | 4 | 11% | |

| Phylloid or Linear Hyperpigmented macules | 16 | 44% | |

| Gingival overgrowth | 7 | 19% |

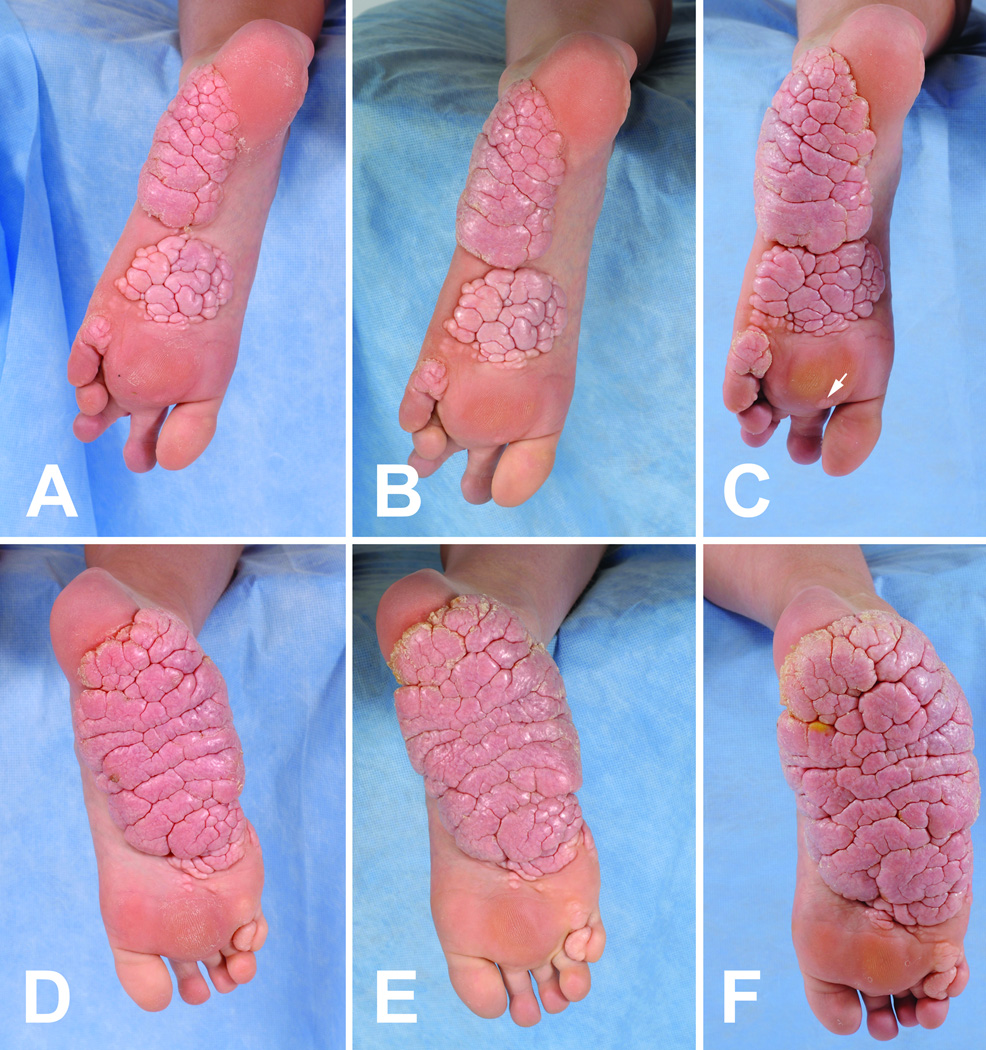

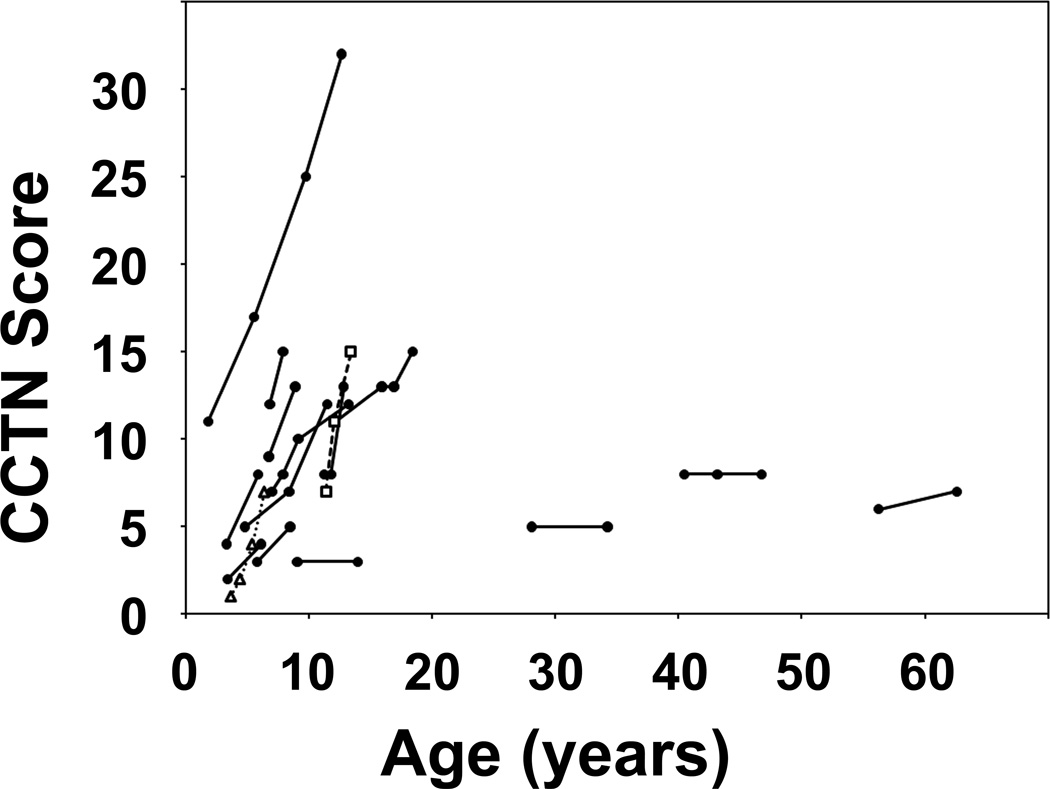

Sixteen patients were studied longitudinally for an average of 53 months. At presentation, the CCTN in 9 patients was a solitary plaque on one or both soles (4 with one or more separate papules or plaques on the toes) and 7 patients had multifocal plaques (4 with toe lesions). The CCTN grew by expansion and development of new lesions. Expansion was evident when a CCTN gradually overtook previously uninvolved skin of the sole, with the convoluted ridges of the CCTN increasing in size and number (Figures 1 and 2). Nearly all CCTNs in children showed expansion, and three children also developed apparently distinct lesions during the study period. New lesions appeared in areas that were previously uninvolved (Figure 1 E–H) or had barely detectable involvement (Figure 2C arrow). Discrete lesions also grew until they coalesced (Figure 2A–C). All patients less than 20 years of age showed progression of the CCTN. One child, who was unusual in that the CCTN involved the chest and abdomen, did not show an increase in the CCTN score during the study period, but progression was clearly evident in the first four years of his life.7 Little or no progression was observed in the three adults (Figure 3). Mixed model analysis indicated that the CCTN score increased on average by 1.24 points per year in those less than 20 years of age (p < 0.001). This rate of increase was significantly greater than in adult patients (p < 0.001), in whom lesions increased by 0.05 points per year (p=0.78).

Figure 1.

Progression of a cerebriform connective tissue nevus early in childhood. Pictures of the left sole (A–D) and right sole (E–H) of a patient with Proteus syndrome were taken at ages 3.7 (A, E), 4.5 (B, F), 5.5 (C, G), and 7.5 (D, H) years. A plaque on the left sole expanded and new plaques appeared near the ball of foot and instep of the right sole.

Figure 2.

Progression of a cerebriform connective tissue nevus later in childhood. Pictures of the left sole (A–C) and right sole (D–F) were taken of a patient with Proteus syndrome at ages 11.4 (A, D), 12.1 (B, E), and 13.4 (C, F) years.

Figure 3.

Graphical analysis of interval changes in CCTN. The total CCTN score at different ages are plotted for each patient in the longitudinal study. The CCTN scores for the patients in Figures 1 and 2 are represented by a dotted line with open triangles and a dashed line with open squares, respectively.

Lipomas increased in size and/or number in 8/10 children with lipomas. Linear verrucous epidermal nevi were stable in size but became darker over time in 4/10 children, and one child developed small new papules of an epidermal nevus between ages 3 and 6 years. Capillary vascular malformations remained stable in extent. Venous varicosities on the legs gradually became more prominent.

DISCUSSION

A mandatory criterion for the diagnosis of Proteus syndrome is a progressive course. This clinical diagnostic criterion refers primarily to the skeletal system, in which patients experience distorting and disproportionate overgrowth of bones.8 Here we show that progression throughout childhood is a consistent feature of the CCTN.

The typical course for the Proteus CCTN is for one or a few lesions to appear on the sole(s) at about 2 years of age, although lesions may also appear in other areas of the body.6 These lesions slowly spread to previously uninvolved skin and grow thicker, becoming rubbery masses that tightly abut each other forming deep folds. It is these deep folds, resembling sulci, which led to the designation of the lesion as cerebriform. New lesions may develop elsewhere on the foot, eventually expanding to coalesce with other lesions. Once it reaches the sides of the foot, the CCTN may extend proximally around the foot, creating a progressively deeper fold between normal-appearing skin and the CCTN. When the lesions occur on the toes, they appear as pale firm nodules that grow and may distort the nail. This type of postnatal disproportionate growth is distinct from that observed in other overgrowth syndromes. In patients with hemihyperplasia-multiple lipomatosis syndrome9 or congenital lipomatous overgrowth, vascular malformations, and epidermal nevi (CLOVE syndrome)10, the plantar surfaces may be overgrown at birth, but they are softer and compressible, with wrinkles rather than deep folds, and tend to grow with the child rather than disproportionately as in patients with Proteus syndrome.

The scoring system we used provides strong evidence for progression of the CCTN in children with Proteus syndrome. It is only semi-quantitative, however, and should not be used to conclude that the rate of growth of the CCTNs was linear or that it was similar in all children. Also, it is not inevitable that all CCTNs progress to involve the entire sole, since the three adults in this study had stable areas of sparing. The adults tended to have lower CCTN scores than the children. This may reflect an overall lower disease severity for those who survive into adulthood.6 Further longitudinal studies with more accurate volume measurements and more adult patients are required to better predict the growth of the Proteus CCTN.

Currently, there is no medical therapy that slows the growth of the CCTN11, and surgery is discouraged because of recurrence and painful scarring that may make walking impossible.12 However, there is one report in the medical literature of a patient with bilateral plantar CCTN who underwent successful surgical removal of the CCTN with skin grafting.13 New treatments are urgently needed, as these lesions are disfiguring and cause functional impairment. Patients with Proteus Syndrome encounter difficulties with hygiene of these lesions, which can lead to odor and recurrent bacterial and fungal infections. Shoes may need to be modified and custom orthoses designed to help prevent blisters and skin breakdown.

One approach to medical therapy would be to target the abnormal cells that contribute to the growth of the CCTN. The CCTN of Proteus syndrome has decreased fibroblasts, variable thick collagen bundles in a disorganized pattern, sparse fragmented elastic fibrils, and increased fat and sweat glands in the deep dermis.14 It would appear that the plantar fibroblasts are defective, and investigations into fibroblasts grown from a CCTN in one patient documented decreased collagenase expression.13

The genetic basis for these cellular abnormalities in Proteus syndrome is unknown. Proteus syndrome appears to result from mosaicism,15 making it especially challenging to identify the mutation(s) that cause Proteus syndrome. Mutations in PTEN have been documented in several children with an overgrowth syndrome with features of Proteus syndrome,16 but the diagnosis of Proteus syndrome has been disputed.17, 18 Genetic analysis in such patients may have therapeutic implications, as one child with life-threatening overgrowth caused by a germline PTEN mutation showed decreased size of soft-tissue masses in the mediastinum and pelvis during treatment with oral rapamycin.19 This promising result needs to be confirmed for others with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome, and it provides hope that further investigations into the genetic and molecular abnormalities in patients with Proteus syndrome will provide clues leading to a targeted therapy.

Capsule Summary.

Proteus syndrome is a rare disorder characterized by postnatal disproportionate overgrowth of the skeletal system, tumor predisposition, and dermatological abnormalities.

The cerebriform connective tissue nevus is frequently observed in patients with Proteus syndrome and it is an important specific criterion for diagnosis.

The cerebriform connective tissue nevus may not be present at birth but grows throughout childhood. Periodic follow-up is needed to manage complications of pain, skin breakdown, and walking impairment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding Sources: Sulzberger Laboratory, and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, NHGRI.

This study was supported by the Sulzberger Laboratory for Dermatologic Research and Intramural Research Funds of the National Human Genome Research Institute. We thank Cara Olsen for statistical analysis.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CCTN

cerebriform connective tissue nevus

- CLOVE

congenital lipomatous overgrowth, vascular malformations, and epidermal nevi

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cohen MM, Jr, Hayden PW. A newly recognized hamartomatous syndrome. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1979;15:291–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiedemann HR, Burgio GR, Aldenhoff P, Kunze J, Kaufmann HJ, Schirg E. The proteus syndrome. Partial gigantism of the hands and/or feet, nevi, hemihypertrophy, subcutaneous tumors, macrocephaly or other skull anomalies and possible accelerated growth and visceral affections. Eur J Pediatr. 1983;140:5–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00661895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner JT, Cohen MM, Jr, Biesecker LG. Reassessment of the Proteus syndrome literature: application of diagnostic criteria to published cases. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;130A:111–122. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biesecker LG, Happle R, Mulliken JB, Weksberg R, Graham JM, Jr, Viljoen DL, et al. Proteus syndrome: diagnostic criteria, differential diagnosis, and patient evaluation. Am J Med Genet. 1999;84:389–395. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19990611)84:5<389::aid-ajmg1>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Twede JV, Turner JT, Biesecker LG, Darling TN. Evolution of skin lesions in Proteus syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:834–838. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen D, Turner JT, Olsen C, Biesecker LG, Darling TN. Cutaneous manifestations of proteus syndrome: correlations with general clinical severity. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:947–953. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.8.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen MMJ. Proteus Syndrome. In: Michael Cohen JM, Neri G, Weksberg R, editors. Overgrowth Syndromes. New York City: Oxford University Press; 2002. p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biesecker L. The challenges of Proteus syndrome: diagnosis and management. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:1151–1157. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biesecker LG, Peters KF, Darling TN, Choyke P, Hill S, Schimke N, et al. Clinical differentiation between Proteus syndrome and hemihyperplasia: description of a distinct form of hemihyperplasia. Am J Med Genet. 1998;79:311–318. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19981002)79:4<311::aid-ajmg14>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sapp JC, Turner JT, van de Kamp JM, van Dijk FS, Lowry RB, Biesecker LG. Newly delineated syndrome of congenital lipomatous overgrowth, vascular malformations, and epidermal nevi (CLOVE syndrome) in seven patients. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:2944–2958. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yavuzer R, Uluoglu O, Sari A, Boyacioglu M, Sariguney Y, Latifoglu O, et al. Cerebriform fibrous proliferation vs. Proteus syndrome. Annals of Plastic Surgery. 2001;47:669–672. doi: 10.1097/00000637-200112000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guidera KJ, Brinker MR, Kousseff BG, Helal AA, Pugh LI, Ganey TM, et al. Overgrowth management in Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber and Proteus syndromes. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13:459–466. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199307000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uitto J, Bauer EA, Santa Cruz DJ, Holtmann B, Eisen AZ. Decreased collagenase production by regional fibroblasts cultured from skin of a patient with connective tissue nevi of the collagen type. J Invest Dermatol. 1982;78:136–140. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12506265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winik BC, Boente MC, Asial RA. Cerebriform plantar hyperplasia: ultrastructural study of two cases. European Journal of Dermatology. 2000;10:551–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brockmann K, Happle R, Oeffner F, Konig A. Monozygotic twins discordant for Proteus syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:2122–2125. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orloff MS, Eng C. Genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity in the PTEN hamartoma tumour syndrome. Oncogene. 2008;27:5387–5397. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen MM, Jr, Turner JT, Biesecker LG. Proteus syndrome: misdiagnosis with PTEN mutations. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;122A:323–324. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Happle R. Linear Cowden nevus: a new distinct epidermal nevus. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:133–136. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2007.0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marsh DJ, Trahair TN, Martin JL, Chee WY, Walker J, Kirk EP, et al. Rapamycin treatment for a child with germline PTEN mutation. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5:357–361. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]