Abstract

Background

Studies published in general and specialty medical journals have the potential to improve emergency medicine (EM) practice, but there can be delayed awareness of this evidence because emergency physicians (EPs) are unlikely to read most of these journals. Also, not all published studies are intended for or ready for clinical practice application. The authors developed “Best Evidence in Emergency Medicine” (BEEM) to ameliorate these problems by searching for, identifying, appraising, and translating potentially practice-changing studies for EPs. An initial step in the BEEM process is the BEEM rater scale, a novel tool for EPs to collectively evaluate the relative clinical relevance of EM-related studies found in more than 120 journals. The BEEM rater process was designed to serve as a clinical relevance filter to identify those studies with the greatest potential to affect EM practice. Therefore, only those studies identified by BEEM raters as having the highest clinical relevance are selected for the subsequent critical appraisal process and, if found methodologically sound, are promoted as the best evidence in EM.

Objectives

The primary objective was to measure inter-rater reliability (IRR) of the BEEM rater scale. Secondary objectives were to determine the minimum number of EP raters needed for the BEEM rater scale to achieve acceptable reliability and to compare performance of the scale against a previously published evidence rating system, the McMaster Online Rating of Evidence (MORE), in an EP population.

Methods

The authors electronically distributed the title, conclusion, and a PubMed link for 23 recently published studies related to EM to a volunteer group of 134 EPs. The volunteers answered two demographic questions and rated the articles using one of two randomly assigned seven-point Likert scales, the BEEM rater scale (n = 68) or the MORE scale (n = 66), over two separate administrations. The IRR of each scale was measured using generalizability theory.

Results

The IRR of the BEEM rater scale ranged between 0.90 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.86 to 0.93) to 0.92 (95% CI = 0.89 to 0.94) across administrations. Decision studies showed a minimum of 12 raters is required for acceptable reliability of the BEEM rater scale. The IRR of the MORE scale was 0.82 to 0.84.

Conclusions

The BEEM rater scale is a highly reliable, single-question tool for a small number of EPs to collectively rate the relative clinical relevance within the specialty of EM of recently published studies from a variety of medical journals. It compares favorably with the MORE system because it achieves a high IRR despite simply requiring raters to read each article’s title and conclusion.

Physicians, their licensing bodies, and professional colleges all recognize that clinical competence is not static and must be maintained.1 A crucial component of the maintenance of clinical competence is improving one’s medical knowledge, by learning of and then incorporating new knowledge into one’s clinical practice. Unfortunately, the delay between publication of information that changes practices, and the incorporation of this knowledge into widespread clinical practice from the original clinical research findings, can exceed a decade.2 The Institute of Medicine, the American Board of Medical Specialties, and the American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM) have, therefore, mandated a continuing medical education process improvement plan by which physicians can maintain clinical practice that is contemporaneous with current research findings.3–5 Many organizations, including ABEM, require their member physicians to demonstrate maintenance of current knowledge by reading and demonstrating some level of comprehension about a selection of current journal articles or textbook chapters.3,6

Periodical medical journals are the most current source of medical information and are typically directed toward physicians according to specialty.7,8 The challenge faced by emergency physicians (EPs) trying to stay current is, in part, due to the wide scope of emergency medicine (EM) practice. To that end, multiple EM-specific journals have emerged over the years to meet the knowledge needs of EPs. While most EM journals report original research, many of these articles may not be immediately applicable to direct clinical practice. McKibbon et al.8 coined the term “number needed to read” (NNR) as a measure of the ratio of number of relevant articles (abstracted or combined abstracted or listed) divided into the total number of articles for each journal title. The NNR to find one clinically relevant study published in Annals of Emergency Medicine is 26.7. Also, EM, unlike most other specialties, broadly spans all areas of acute medicine and surgery. Therefore, many of the articles clinically relevant to the practice of EM are published in non-EM medical journals, further increasing the NNR for EPs. Finally, not all clinician-directed studies are practice-changing.

To help EPs with these challenges and their need to maintain current knowledge, a group of North American EP researchers and educators at McMaster and Washington Universities created BEEM (Best Evidence in Emergency Medicine). BEEM is based on the work of the Health Information Research Unit (HIRU) at McMaster University, which “conducts research in the field of health information science and is dedicated to the generation of new knowledge about the nature of health and clinical information problems, the development of new information resources to support evidence-based health care, and the evaluation of various innovations in overcoming health care information problems.”9 In short, the HIRU continuously searches more than 120 top clinical journals for research and review articles of all specialties. Because not all published studies are intended for clinicians and not all clinician-directed studies are potentially practice changing, minimum inclusion criteria are applied during a screening process to select “the very best literature, consistent with a reasonable number of articles making it through the filter.”10 Through their work on second-order peer review, Haynes et al.11,12 also created the McMaster Online Rating of Evidence (MORE), a unique medical literature-rating service applicable to clinicians of all specialties. The MORE system uses the HIRU to search for articles and categorizes those that pass the method quality filters according to applicable specialty. It then assigns qualifying articles to registered raters according to specialty and records their online ratings of the complete articles using a seven-point Likert scale for relevance and another for newsworthiness (defined as useful new information for physicians). The details of the HIRU and related projects such as MORE are explained in full online.13

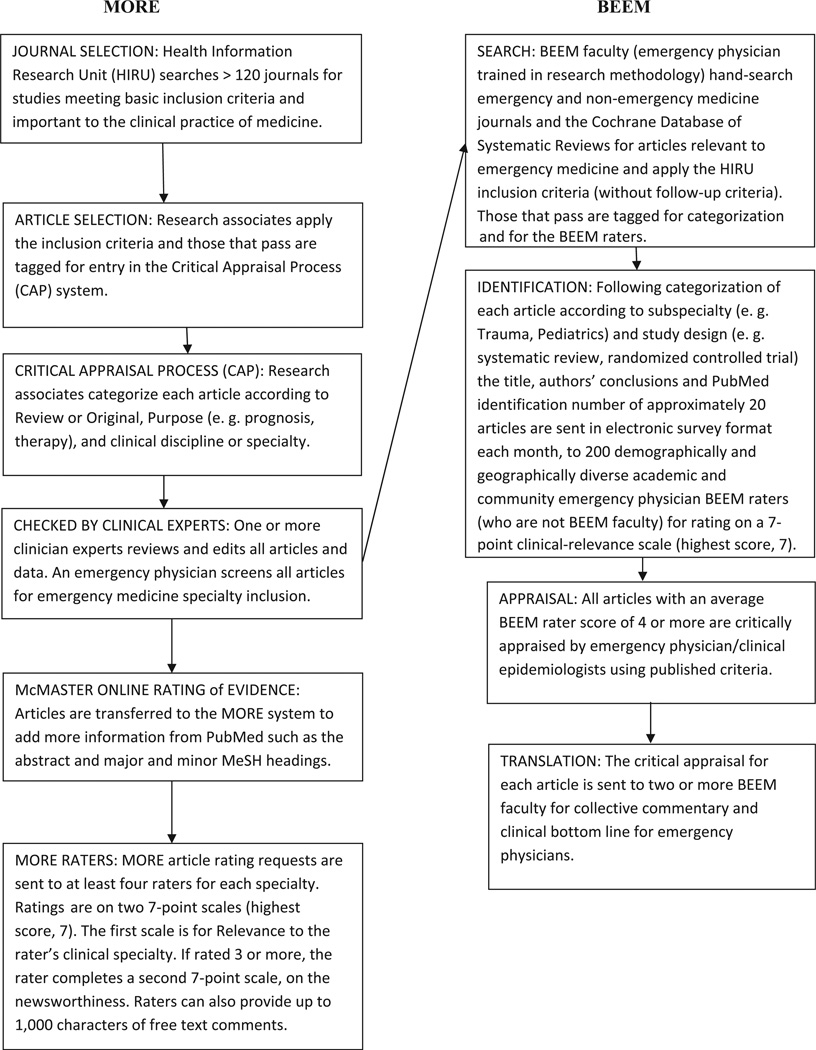

BEEM distinguishes itself from MORE by being an academic collaboration of EPs who collectively search for, identify, appraise, and translate current, potentially practice-changing studies for EPs. To that end, BEEM faculty regularly hand search the current high-impact EM, general medicine, pediatric, and surgical journals and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) for studies related to EM. The results are combined with those of the HIRU using all of the same inclusion criteria except the follow-up thresholds (Figure 1). Follow-up thresholds describe the proportion of patients in a study that do not complete the protocol, including all downstream measurements after enrollment. Because of the inclusion of more EM journals and no follow-up thresholds, the BEEM process finds articles not identified for EM by the HIRU.

Figure 1.

MORE and BEEM manuscript filtering, appraisal, and selection processes.

To identify which articles, including guidelines and reviews, EPs would find the most clinically relevant, BEEM created a clinical relevance–rating tool, the BEEM rater scale. Also, given that EPs would be unlikely to read multiple articles or even abstracts as part of a screening process, we sought to present the minimum amount of information needed to determine an article’s clinical relevance to EM, with the aim of optimizing EP participation in screening multiple articles.14,15 Specifically, the EP BEEM raters are presented only the titles and conclusions of the articles. The Pub-Med ID is also provided as an option for learning more about the study as needed. In addition to being very time-consuming, there was concern that presentation of the complete article might introduce bias, as some BEEM raters might tend to rate the article on domains other than clinical relevance to EM, such as the journal impact, author, or study design. The BEEM raters are sent an e-mail each month with a hyperlink to access a Web-based survey with the titles and conclusions of each article and are asked to rate each article using a single item with a Likert scale.

The primary objective of this study was to measure the inter-rater reliability (IRR) of the BEEM rater scale. The IRR is a measure of the consistency with which different raters agree beyond chance alone.16 A secondary objective was to determine the minimum number of BEEM raters needed to achieve acceptable reliability.

The MORE rating system, although different from the BEEM rater scale in purpose and function, is the only known medical literature–rating tool and so was used as the reference standard for the BEEM rater scale’s performance. Hence, a third objective of this study was also to compare the IRR of the BEEM rater scale to the MORE scale.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

This was an online survey of volunteer EPs conducted from October to December 2009. The McMaster University/Hamilton Health Sciences Research Ethics Board approved this study.

Participants were practicing, postresidency, English-speaking EPs from the United States, Canada, Great Britain, and Australia. These physicians were recruited from several sources including prior continuing medical education courses during the years 2005–2009, non–peer-reviewed publications, and professional conferences and through volunteers contacting BEEM directly.17,18 Although participants had the opportunity to win a complementary 1-year subscription to a PDA-based product (PEPID, LLC, Evanston, IL) and free registration to a BEEM course, they were not paid or otherwise compensated for their efforts. The BEEM rater e-mails are sent to the entire list of volunteers monthly, but the current study reports on 2 months’ results.

Survey Content and Administration

Using a random number generator, all raters were randomly assigned to use one of two rating methods: BEEM (Table 1) or MORE (Table 2).19,20 Raters were unaware of group assignment until after they consented to participate by clicking on the hyperlink to the survey at SurveyMonkey (http://www.surveymonkey.com). They were also unaware of the objectives for the duration of the study and were free to withdraw from the study at any time by not completing the survey or by contacting the BEEM administrator and requesting to withdraw.

Table 1.

BEEM Rater Scale

“Assuming that the results of this article are valid, how much does this article impact on EM clinical practice?”

|

BEEM = Best Evidence in Emergency Medicine.

Table 2.

MORE Scale

Item 1: Relevance to clinical practice in your discipline

|

| If you have scored the article more than 2 on relevance, please continue to rate its importance: |

Item 2: Newsworthiness to clinical practice in your discipline

|

MORE = McMaster Online Rating of Evidence.

Outcome Measures

The first two survey questions asked about country of practice and certification in EM. These questions were followed by the title, conclusion, and a PubMed link to each of eight recently published studies related to EM practice on the first survey administration and 15 on the second survey administration 1 month later. Participants assigned to the BEEM group received the above information, along with the BEEM Rater Scale.21,22 They were asked to rate each manuscript using the scale. Participants assigned to the MORE group received the same information, but were asked to use the MORE scale of newsworthiness (Table 2, item 2) to rate the evidence. The final question of the survey asked: Of the studies that you just rated, for what proportion did you use the PubMed ID to view the abstract? Choices for answers were: 1) 0%, 2) 1% to 20%, 3) 21% to 40%, 4) 41% to 60%, 5) 61% to 80%, 6) 81% to 99%, and 7) 100%.

Data Analysis

We measured the IRR across each of the two tools using generalizability theory—an extension of classic psychometric approaches to reliability.21 The entire process was repeated 1 month later with different, more recently published articles as they became available and also so as not to burden the raters with too many articles to screen at one time.

For the first administration 38 BEEM raters rated eight articles and for the second administration 48 raters rated 15 articles. The first administration of MORE involved eight articles and 36 raters, and the second, 15 articles sent to 38 raters. Ratings from individual raters were used if they rated the majority of the studies, defined as six articles for the first administration and 13 for the second. The primary analysis was the determination of IRR separately for each administration of the BEEM scale and the MORE newsworthiness item (Table 2, item 2) using generalizability theory.

Generalizability studies (G-studies) have been used in the reliability assessment of clinical measurement tools for injury, quality of life, and physical capacity.23–25 Generalizability coefficients are mathematically equivalent to other reliability measures such as the intraclass correlation coefficient or the weighted kappa, and like these measures range from 0 to 1.16,25 However, generalizability coefficients have the added advantage of calculating reliability when there are multiple sources of variability as in this study, where items as well as the raters contribute to variability in the MORE scale. A typical study of reliability must assess inter-rater, internal consistency (the degree to which items correlate with one another), test–retest reliability, etc., separately.16 A G-study allows for the consideration of all these sources of variation (called facets of generalization in the parlance of psychometrics) in a single design. One of the most powerful aspects of G-studies is the follow-up decision, or D-study. The D-study is the logical extension of this approach for the maximization of reliability by considering the magnitude of variance caused by each source of variation in the study. Because reliability increases as the number of raters or items increases, D-studies can be used to determine the minimum number of raters or items required to achieve a given reliability. This allows for the most efficient use of resources to achieve acceptable reliability.25 A D-study was performed for the BEEM and MORE scale to determine the optimum number of raters needed for acceptable reliability. The sample formula for the G- and D-study of the BEEM tool is given in Appendix 1. The minimum acceptable reliability score is generally considered 0.7, although no fixed standard exists, and clinical scales are generally considered to have acceptable reliability in the range of 0.7 to 0.9. We chose 0.7 as our minimally acceptable reliability.16

The IRR of the MORE with both items was also calculated, along with Cronbach’s alpha for internal consistency for the first and second months. We conducted D-studies to determine the minimum number of raters required for the BEEM scale and MORE to achieve an acceptable IRR. Generalizability coefficients (G-coefficients) and D-studies were calculated using G_String III (Hamilton, Ontario, Canada). For the BEEM rater group, we averaged the proportions of articles that raters claimed to have used the PubMed ID to view the entire articles. Additional analyses of the scales examined if there were systematic differences between BEEM and MORE raters using independent-samples t-test. To check convergent validity (if raters were rating articles similarly), a Pearson correlation between ratings of BEEM and MORE is also reported.

Although technically seven-point Likert scales produce ordinal data, they can justifiably be analyzed using parametric methods.26 These methods have the advantage of being more powerful than their nonparametric counterparts in detecting differences that may be important in the first stage of psychometric assessment. Second, several analyses of ordinal scale data using both parametric and nonparametric methods have demonstrated that both classes of tests tend to give similar results, and that parametric tests are indeed robust for use with ordinal data.26,27 This may be in part because nonparametric tests, such as Spearman’s correlation, are mathematical extensions of their parametric counterparts (the Pearson correlation). Summary measures are reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) where applicable.

RESULTS

Of the participant raters in this study, 48% reported practicing in Canada, 48% in the United States, and 4% outside of North America. Most (82%) were certified in EM. The average rating for each article is listed for MORE item 2 and BEEM scales in Data Supplement S1 (available as supporting information in the online version of this paper). On average, raters claimed to have used the PubMed ID to view the abstract for 14% of articles.

The absolute IRR for the BEEM was determined for each administration separately, with the first month at 0.92 (95% CI = 0.89 to 0.94) and the second month at 0.90 (95% CI = 0.86 to 93). The absolute IRR for the MORE scale item 2 for the first month was 0.73 (95% CI = 0.60 to 0.83), and for the second month the IRR was 0.82 (95% CI = 0.75 to 0.87). The absolute IRR with both MORE items was 0.80 during the first month and 0.88 for the second month. The internal consistencies (Cronbach’s alpha) for the first and second months of MORE were 0.66 and 0.87, respectively.

The D-study for the BEEM and the MORE was conducted based on the second administration of 15 articles and is reported in Table 3. In this Table, the IRR for MORE is reported with inclusion of both items in the calculation, instead of just item 2.

Table 3.

Number of Raters Needed to Achieve Sufficient Reliability (D-study Results)

| Number of Raters |

Absolute IRR MORE |

Absolute IRR BEEM |

|---|---|---|

| 48 | 0.92 | 0.90 |

| 30 | 0.88 | 0.85 |

| 25 | 0.86 | 0.82 |

| 20 | 0.83 | 0.79 |

| 15 | 0.79 | 0.74 |

| 12 | 0.75 | 0.70 |

| 10 | 0.71 | 0.68 |

| 1 | 0.20 | 0.16 |

IRR = inter-rater reliability; BEEM = Best Evidence in Emergency Medicine; MORE = McMaster Online Rating of Evidence.

MORE raters did not differ significantly from BEEM raters for the first administration, but did for the second. Mean ratings (± standard error [SE]) for the first administration were 4.87 (±0.23) for MORE and 4.34 (±0.17) for BEEM (p > 0.05). The mean (±SE) ratings for the second administration were 4.50 (±0.16) for MORE and 3.97 (±0.16) for BEEM (p = 0.03), Cohen’s effect size of 0.8. MORE and BEEM ratings were positively correlated at 0.76 (p < 0.001). Use of nonparametric equivalents did not affect the interpretation of significance tests.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that the BEEM rater scale can achieve a high IRR for a small group of EPs to collectively rate the literature for clinical EM relevance and compares favorably with both the newsworthiness item of the MORE scale and the scale as a whole. This is a significant advantage of using the BEEM rater scale as raters with minimum information can reliably use the BEEM tool for screening publications. With the current number of raters, the BEEM rater scale exceeds the minimum criteria for reliability from most IRR standards and is comparable to the established MORE scale (the only other literature rating scale). The BEEM rater scale can also be used with sufficient reliability with a minimum of 12 to 15 raters. Although there is evidence from the second administration that BEEM raters on average tended to rate more conservatively than MORE raters, the actual magnitude of this difference is small. Further comparisons of the ratings of MORE and BEEM may be warranted to explore this effect. The strong positive correlation between MORE and BEEM ratings is preliminary evidence for convergent validation—raters in both scales tend to rate articles in a similar fashion. However, this type of validity is less useful than direct evidence that the BEEM rater scale can predict the future impact of published studies.

Only 14% of BEEM raters claimed to have used the PubMed ID to view the complete abstract. Previous research suggests that physicians do not understand biostatistical concepts.28,29 Because few want to be the first or the last to adopt research-based practice changes, busy clinicians face dual impediments to interpreting the medical literature: a continually decreasing signal-to-noise ratio because of an ever-expanding volume of research manuscripts and insufficient time, training, or expertise to critically appraise original scientific reports independently.30–34 Therefore, one would surmise that even fewer practicing EPs would be able to review a study in its entirety. BEEM was created in recognition of these challenges and is meeting its objective of helping EPs maintain current knowledge via a three-pronged approach, including continuing medical education, second-order peer- and non–peer-reviewed publications, and original educational research of this evidence-based approach to knowledge translation.17,35–42 The BEEM rater system is based on the informal hypothesis that EP BEEM raters can assess the clinical relevance of a study from only the title and the conclusion. We interpret the finding that only 14% of BEEM raters claimed to have used the PubMed ID to view the complete abstract as supportive of our hypothesis. To that end, this study demonstrates that EPs with limited information can collectively identify which EM-related articles are most clinically relevant. This is not surprising, given that EPs, regardless of certification, are experts on the topic of EM clinical relevance. Also, given that most BEEM raters are from western countries, there is likely a strong similarity in clinical practice.

BEEM does not apply follow-up thresholds as part of the filtering process, because they are included in the critical appraisal and can be interpreted accordingly, and this allows for more EM-related studies to be included from the search. For example, an EM study on procedural sedation would be expected to have 100% follow-up since the entire study is conducted during the ED visit. Any follow-up less than 100% would suggest the study suffers from quality issues that EPs might want to know about before applying the results to their own practices. Conversely, a study involving long follow-up, periods in younger adults, and especially known transient populations would be expected to have lower follow-up rates with time although these would not necessarily invalidate the study results. Application of the HIRU inclusion criteria during the search process would automatically include the first study if the follow-up rate were 80% or greater and exclude the second if the follow-up rate fell below 80%.

LIMITATIONS

MORE is a literature-rating tool of newly published articles that requires readers to consider a study’s methodology and the validity of the results. The BEEM rater scale, however, is a clinical relevance rating tool that only requires readers to read the titles of newly published manuscripts to make a decision. The BEEM rater scale was designed by a demographically and geographically diverse group of EPs in order to give greater generalizability to the results. It therefore serves as a filter through which articles, nominated by BEEM rater consensus based on clinical relevance, pass for critical appraisal and translation by EPs trained in research methodology. It is the consensus aspect of the filtering process that requires high IRR. The term “inter-rater reliability” can be misinterpreted as a fixed performance characteristic of the scale. In fact, “interrater reliability” is a dynamic measure that is strongly influenced by the number of articles and, to a lesser degree, by the number and nature of the raters. The BEEM rater scale was designed for use by a demographically and geographically diverse group of EPs to give greater generalizability to the results and not for use by a single physician or by non-EPs.

Because it is the only medical literature–rating tool of its kind, the MORE rating system was used as the reference standard for the BEEM rater scale’s performance. A study to directly compare the two would require that the MORE rating system method be used as originally developed, where raters are provided with the full text of the article and must declare no conflict of interest before rating an article.

The purpose of the randomization process was to minimize the imbalance of unknown response determinants between the two groups. We collected basic demographic information from each participant only to be able to describe the population of BEEM raters. We had no a priori hypothesis for differences in responses based on demographics and so we did not compare the demographics of the two groups. As such, the analysis was not adjusted based on demographic differences.

This study does not demonstrate that the BEEM rater scale is a valid tool for EPs to collectively identify the most clinically relevant, recently published studies. It only demonstrates the tool’s high IRR, the first step in psychometric evaluation and a necessary prerequisite for validity assessment.43

The selection of BEEM raters is subject to volunteer bias and varies in number and demographics each month according to which BEEM raters take the time to participate in the monthly BEEM rater process. Therefore, our results might not be truly representative of all EPs.

Future research should first determine the predictive validity of the BEEM rater scale using multiple measures. Validation of the BEEM rater scale will aid the synthesis and translation of new published research that is of clinical relevance to EPs.

CONCLUSIONS

The Best Evidence in Emergency Medicine rater scale is a single-question tool that can achieve a high inter-rater reliability with a small group of EPs for collective identification of the clinical relevance of recently published studies using just the title and conclusions and is comparable in inter-rater reliability to the McMaster Online Rating of Evidence rating system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Divisions of Emergency Medicine at McMaster University and Washington University. Dr. Carpenter was supported by the Washington University Goldfarb Patient Safety award.

The authors thank the many BEEM raters who contributed their time and expertise to make this study possible and who continue to work to screen multiple articles each month to identify the most clinically relevant, EM-related articles as they are published.

APPENDIX 1

Formula for overall generalizability coefficient for BEEM:

where V(a) is the variance of articles, V(r) is the variance of raters, V(a × r) is the variance of article × rater interaction, and nr is the number of raters. For D-studies, the nr is changed to determine the effect on the generalizability coefficient.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest or other disclosures to declare.

Supporting Information:

The following supporting information is available in the online version of this paper:

Data Supplement S1. Average article ratings.

The document is in PDF format.

Please note: Wiley Periodicals Inc. is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- 1.Sherbino J, Upadhye S, Worster A. Self-reported priorities and resources of academic emergency physicians for the maintenance of clinical competence: a pilot study. CJEM. 2009;11:230–234. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500011246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2635–2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller SH. American Board of Medical Specialties and repositioning for excellence in lifelong learning: maintenance of certification. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2005;25:151–156. doi: 10.1002/chp.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Board of Emergency Medicine. Emergency Medicine Continuous Certification. [Accessed Aug 24, 2011]; Available at: http://abem.org/PUBLIC/portal/alias__Rainbow/lang__en-US/tabID__3421/DesktopDefault.aspx.

- 5.Schrock JW, Cydulka RK. Lifelong learning. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2006;24:785–795. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Upadhye S, Carpenter CR, Diner B. Methodological quality of the American Board of Emergency Medicine lifelong self-assessment reading lists [abstract] Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:S131. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaughnessy AF, Slawson DC, Bennett JH. Becoming an information master: a guidebook to the medical information jungle. J Fam Pract. 1994;39:489–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKibbon KA, Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB. What do evidence-based secondary journals tell us about the publication of clinically important articles in primary healthcare journals? BMC Med. 2004;2:33. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-2-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMaster University. Health Information Research Unit. Homepage. [Accessed Aug 24, 2011]; Available at: http://hiru.mcmaster.ca/hiru/Default.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMaster University. HIRU Inclusion Criteria. [Accessed Aug 24, 2011]; Available at: http://hiru.mcmaster.ca/hiru/Inclusion-Criteria.html. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haynes RB, Cotoi C, Holland J, et al. Second-order peer review of the medical literature for clinical practitioners. JAMA. 2006;295:1801–1808. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.15.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMaster University. McMaster Online Rating of Evidence. [Accessed Aug 24, 2011]; Available at: http://hiru.mcmaster.ca/MORE/AboutMORE.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McMaster University. McMaster PLUS. [Accessed Aug 24, 2011]; Available at: http://hiru.mcmaster.ca/hiru/HIRU_McMaster_PLUS_Projects.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dillman DA. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dillman DA, Bowker DK. The web questionnaire challenge to survey methodologists. In: Reips UD, Bosnjak M, editors. Dimensions of Internet Science. Lengerich, Germany: Pabst Science; 2001. pp. 159–178. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carpenter CR, Kane BG, Carter M, et al. Incorporating evidence-based medicine into resident education: a CORD survey of faculty and resident expectations. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(Suppl 2):S54–S61. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00889.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emergency Physicians Monthly Inc. Homepage. [Accessed Oct 4, 2010]; Available at: http://www.epmonthly.com/the-literature/evidence-based-medicine/ [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zelen M. A new design for randomized clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1242–1245. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197905313002203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zelen M. Randomized consent designs for clinical trials: an update. Stat Med. 1990;9:645–656. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780090611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Likert RA. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch Psych. 1932;140:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dawes J. Do data characteristics change according to the number of scale points used? An experiment using 5-point, 7-point, and 10-point scales. Int J Market Res. 2008;50:61–77. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evans WJ, Cayten CG, Green PA. Determining the generalizability of rating scales in clinical settings. Med Care. 1981;19:1211–1219. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198112000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roebroek Me, Harlaar J, Lankhorst GJ. Application of generalizability theory to reliability assessment: an illustration using isometric force measurements. Phys Ther. 1993;73:386–395. doi: 10.1093/ptj/73.6.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norman G. Likert scales, levels of measurement, and the “laws” of statistics. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2010;15:625–632. doi: 10.1007/s10459-010-9222-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Havlicek LL, Peterson NL. Robustness of the Pearson correlation against violation of assumptions. Percept Mot Skills. 1976;43:1319–1334. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Windish DM, Huot SJ, Green ML. Medicine residents’ understanding of the biostatistics and results in the medical literature. JAMA. 2007;298:1010–1022. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.9.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hack JB, Bakhtiari P, O’Brien K. Emergency medicine residents and statistics: what is the confidence? J Emerg Med. 2009;37:313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berwick DM. Disseminating innovations in health care. JAMA. 2003;289:1969–1975. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.15.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cone DC, Lewis RJ. Should this study change my practice? Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:417–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb00621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grol R, Wensing M. What drives change? Barriers to and incentives for achieving evidence-based practice. Med J Aust. 2004;180(6Suppl):S57–S60. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb05948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th ed. New York, NY: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diner BM, Carpenter CR, O’Connell T, et al. Graduate medical education and knowledge translation: role models, information pipelines, and practice change thresholds. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:1008–1014. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.BEEM Best Evidence in Emergency Medicine. [Accessed June 16];Homepage. 2010 Available at: http://www.beemsite.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carpenter CR. The San Francisco Syncope Rule did not accurately predict serious short-term outcome in patients with syncope. Evid Based Med. 2009;14:25. doi: 10.1136/ebm.14.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carpenter CR. Review: adding dexamethasone to standard therapy reduces short-term relapse for acute migraine in the emergency department. Evid Based Med. 2009;14:121. doi: 10.1136/ebm.14.4.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carpenter CR, Keim SM, Crossley J, et al. Post-transient ischemic attack early stroke stratification: the ABCD(2) prognostic aid. J Emerg Med. 2009;36:194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carpenter CR, Keim SM, Seupaul RA, et al. Differentiating low-risk and no-risk PE patients: the PERC score. J Emerg Med. 2009;36:317–322. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carpenter CR, Keim SM, Upadhye S, et al. Risk stratification of the potentially septic patient in the emergency department: the Mortality in the Emergency Department Sepsis (MEDS) score. J Emerg Med. 2009;37:319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Worster A, Keim SM, Sahsi R, et al. Do either corticosteroids or antiviral agents reduce the risk of long-term facial paresis in patients with new-onset Bell’s palsy? J Emerg Med. 2010;38:518–523. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Milne WK, Worster A. Evidence-based emergency medicine/rational clinical examination abstract. Does the clinical examination predict lower exremity peripheral arterial disease? [comment] Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:748–750. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lokker C, McKibbon KA, McKinlay RJ, et al. Prediction of citation counts for clinical articles at two - years using data available within three weeks of publication: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336:655–657. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39482.526713.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.