Abstract

Australia is a very large country with a relatively small, diverse population. Palliative care is delivered by a range of professionals, from general (family) practitioners and community care nurses to large tertiary referral palliative care services. A national strategy provides a service development framework that informs the provision of these services. The National Palliative Care Program has provided extensive service improvement in the past decade. Challenges to improving the delivery of palliative care center around meeting the requirements of people with nonmalignant life-limiting illnesses; growing the specialist workforce; maintaining the skills of the primary care workforce; and providing palliative care to special populations such as the aged, indigenous Australians, non–English-speaking Australians, and children.

Keywords: Australia, health policy, health service organization, palliative care, primary care

A THUMBNAIL SKETCH OF AUSTRALIA

Australia, a country of 22 million people, is the sixth largest country by area on earth.1 Approximately 80% of the population occupies the coastal fringes, particularly around the eastern and southeastern quarters of the country. The remainder of the country comprises agricultural land ranging from rich grain- and produce-growing areas, to semiarid grazing country. Approximately half of the country is desert and unsuitable for settlement. The population is highly concentrated further around 7 capital cities with as many as 3-4 million people.2 Several larger regional centers have up to 500,000 inhabitants. The populations of inland towns range from a few hundred to several thousand people. These towns can be hundreds of miles apart, and reliance on communications and transport technology is essential.

Australia is one of the most multicultural countries on earth. As well as being descendants of the indigenous Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island population, its citizens have migrated from or are descendents of migrants from more than 200 countries. In the past 60 years, planned migration has brought 6.5 million people to Australia. Waves of migrants followed crises in various parts of the world in the past 150 years, bringing Anglo-Celtic peoples in the 19th and early to mid 20th centuries, southern and eastern Europeans after World War II, Vietnamese in the late 1960s, and now refugees from western Asia and Saharan Africa. In addition, economic migrations from China, India, and Southeast Asia reflect a recent trend. Approximately one-quarter of the current population was born overseas.3 Immigration contributed 57% of the country's population growth from 2009 to 2010.4

In 2010, Australians had the 10th highest per capita income in the world (US$ 39,699)5 and the second highest life expectancy in the world, behind Japan.6 However, the Australian indigenous population has not shared these benefits. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have a life expectancy 19 years lower than that of other Australians, with a much lower quality of life as well.6

Hence, the health system in Australia must serve a hugely diverse population across a wide array of geographical settings. The system must be flexible in delivery and take into account the relatively small population base that supports it.

THE AUSTRALIAN HEALTH SYSTEM

Australia is a federation of autonomous states, with a federal government that collects taxes and distributes these to the states. Broadly speaking, the federal government funds community-based services, especially general (family) practice and aged care. States are responsible for public hospitals and ancillary services.

Funding of health in Australia follows a mixed model.7 A universal health insurance scheme (Medicare) funds individual consultations with doctors and partially funds the public hospital system. Elective private health insurance supports private hospitals and associated costs. Approximately 45% of Australians hold private health insurance, and coverage is encouraged by a tax rebate on premiums. In addition, a government-subsidized pharmaceutical benefits scheme partially subsidizes the cost of essential pharmaceuticals. Above an annual cost limit, the government subsidy rises, thereby ensuring that pharmaceuticals do not provide an inordinate drain on individual resources.

Access to the Australian health system is through the primary healthcare system. General practitioners (GPs) provide first-line services to all patients, and access to Medicare-subsidized specialists comes via referral from a patient's GP. This referral system ensures that the patient is directed to the most appropriate service. The vast majority of healthcare across the board is thus delivered by general practice/primary care, and 80% of the population sees their GP at least once a year.8

PALLIATIVE CARE IN AUSTRALIA

Palliative care is defined as an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification, impeccable assessment, and treatment of pain and other problems—physical, psychosocial, and spiritual.9

Palliative care in Australia is delivered in different ways depending on the geographic location and available resources. Different levels of palliative care services are categorized according to their resourcing.10 Palliative care services include consultations to larger hospitals with or without dedicated palliative care beds or to standalone palliative care services providing community-based care, and consultations to general practice, palliative care beds, or a combination.

Primary care has a clear role in the delivery of palliative care.10 Cancer patients dominate most palliative care services. However, most people who die of diseases with predictable illness trajectories do not have cancer. These individuals suffer from organ failure or frailty. One of the great dilemmas of modern medicine is to determine how and when palliative and supportive care should be offered to individuals with these conditions.11

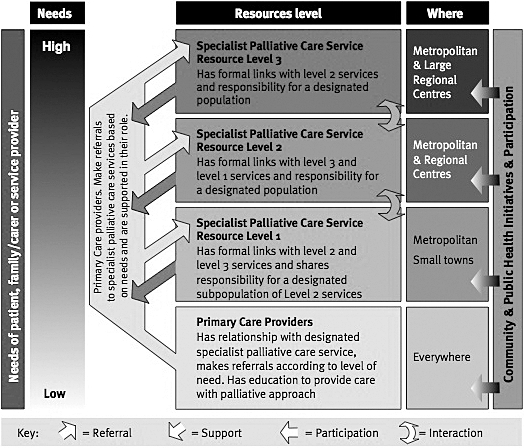

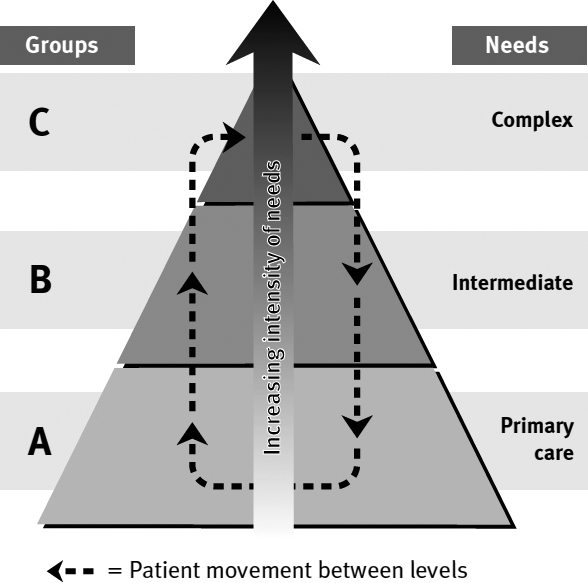

Australian patients receive palliative care on the basis of need, not of prognosis.12 Considerable work has been undertaken to ensure that patients with life-limiting illnesses are provided the level of care they need. Figures 1 and 2 show the conceptual model around which Australian palliative care is organized.10 Patients move between services depending on the complexity of their needs via services appropriate to the size of the population. Smaller services develop links with larger services that provide advice and receive referrals of patients with more complex needs. At all times, palliative care should be linked to the patient's GP so care is shared. A needs assessment tool for palliative care (the NAT-PC) was developed to help practitioners within the services and in nonspecialist palliative care settings assess the degree to which the needs of patients and families are being met and to provide a prompt for referral to a specialist palliative care service if required.13

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of level of care within the population of patients with a life-limiting illness. (Reprinted as is with permission from Palliative Care Australia.10)

Figure 2.

Australian Palliative Care service framework. (Reprinted as is with permission from Palliative Care Australia.10)

The national Australian government has long recognized the importance of providing high quality palliative care, both as a matter of equity but also of efficiency. Since 1999, the government has administered the Palliative Care Program that has delivered more than $100 million of quality enhancement benefits.14 These benefits have included national benchmarking; support for local service improvements; research into service delivery and clinical research; education of health professionals at the undergraduate and postgraduate levels; patient education and the promotion of advance health directives; and initiatives to special groups such Aboriginal people, residents of rural and remote locations, children, and people of diverse ethnic backgrounds. A central web-based repository of information and research resources (CareSearch—www.caresearch.com.au) is a core feature of this national endeavor.

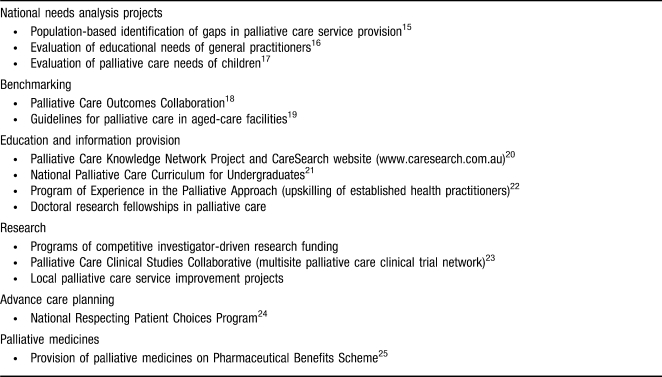

The Palliative Care Program has produced some world-class outcomes (Table).15-25 However, improvements have not been uniform across communities, and much must be done to continue service improvements. Improvements will become more challenging as the population ages and the palliative care workforce ages with it. There will not be enough specialist palliative care services to meet the need, and it is essential that primary care is primed to take an increasing share of the palliative care burden.26

Table.

Examples of Major Quality Advancement Initiatives in Australian Palliative Care 1999-2010

The areas of greatest challenge include providing palliative care to all people, particularly those with nonmalignant diseases27; developing an adequate specialist workforce28; encouraging people in primary care to provide high quality palliative care29; providing access to medicines when needed, particularly opioids; and developing better evidence for nonpain symptom management.30

CONCLUSION

Palliative care in Australia reflects the complexity of the health system and the diversity of its population and geography. It has largely succeeded in providing access to services to the vast majority of its population within its means.

This article meets the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and American Board of Medical Specialties Maintenance of Certification competencies for Patient Care, Medical Knowledge, and Systems-Based Practice.

Footnotes

The author has no financial or proprietary interest in the subject matter of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 2010. Australia in brief: Australia—an overview. http://www.dfat.gov.au/aib/overview.html. Accessed July 17, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 2010. Australia in brief—the island continent. http://www.dfat.gov.au/aib/island_continent.html. Accessed July 17, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 2010. Australia in brief—a diverse people. http://www.dfat.gov.au/aib/society.html. Accessed July 17, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2011. 3412.0 Migration, Australia, 2009-2010. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats. Accessed July 17, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Monetary Fund. 2011. Report for Selected Countries and Subjects. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2010/01/weodata/weorept.aspx?sy=2007&ey=2010&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=111&s=NGDPD%2CNGDPDPC%2CPPPGDP%2CPPPPC%2CLP&grp=0&a=&pr.x=40&pr.y=10. Accessed July 17, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's health 2008. Canberra, Australia: AIHW; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 2010. About Australia—Healthcare in Australia. http://www.dfat.gov.au/facts/healthcare.html. Accessed July 17, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pegram R, editor. General Practice in Australia: 2004. Canberra, Australia: Department of Health and Ageing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. 2004. WHO definition of palliative care. http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. Accessed July 17, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palliative Care Australia. A Guide to Palliative Care Service Development: A Population-Based Approach. Canberra, Australia: PCA; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell GK, Johnson CE, Thomas K, Murray SA. Palliative care beyond that for cancer in Australia. Med J Aust. 2010;193(2):124–126. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell G, Currow D. Palliative and supportative care. In: Robotin M, Olver I, Girgis A, editors. When Cancer Crosses Disciplines: A Physician's Handbook. Sydney, Australia: World Scientific Books; 2009. pp. 1022–1120. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waller A, Girgis A, Johnson C, et al. Facilitating needs based cancer care for people with a chronic disease: Evaluation of an intervention using a multi-centre interrupted time series design. BMC Palliat Care. 2010;9:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-9-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Department of Health and Ageing. The Australian Government National Palliative Care Program. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/palliativecare-program.htm. Accessed July 18, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McNamara B, Rosenwax L. Factors affecting place of death in Western Australia. Health Place. 2007;13(2):356–367. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reymond E, Mitchell G, MCGrath B, Welch D. Research into the Educational, Training, and Support Needs of General Practitioners in Palliative Care. Brisbane, Australia: Mt. Olivet Health Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Healthcare Management Advisors Ltd. Paediatric Palliative Care Service Model Review. Canberra, Australia: Department of Health and Ageing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eagar K, Watters P, Currow DC, Aoun SM, Yates P. The Australian Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration (PCOC)—measuring the quality and outcomes of palliative care on a routine basis. Aust Health Rev. 2010;34(2):186–192. doi: 10.1071/AH08718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kristjanson LJ. Guidelines for a Palliative Approach in Residential Aged Care. Canberra, Australia: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tieman JJ, Abernethy AP, Fazekas BS, Currow DC. CareSearch: finding and evaluating Australia's missing palliative care literature. BMC Palliat Care. 2005;4:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-4-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hegarty M, Currow D, Parker D, et al. Palliative care in undergraduate curricula: results of a national scoping study. Focus Health Prof Ed. 2010;12(2):97–109. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hegarty M. The dynamic of hope: hoping in the face of death. Prog Palliat Care. 2001;9(2):42–46. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flanders University of Australia. 2011. Palliative Care Clinical Studies Collaborative. http://www.caresearch.com.au/caresearch/tabid/97/Default.aspx. Accessed July 17, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Department of Health and Ageing. 2011. Pharmaceutical Benefits for Palliative Care. Australian Government Canberra. http://www.pbs.gov.au/browse/palliative-care. Accessed July 17, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitchell GK. Primary palliative care - facing twin challenges. Aust Fam Physician. 2011;40(7):517–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murray SA, Sheikh A. Palliative Care Beyond Cancer: care for all at the end of life. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):958–959. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39535.491238.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Department of Health and Ageing. Supporting Australians to Live Well at the End of Life. Draft National Palliative Care Strategy 2010. Canberra, Australia: Department of Health and Ageing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rhee JJ, Zwar N, Vagholkar S, Dennis S, Broadbent AM, Mitchell G. Attitudes and barriers to involvement in palliative care by Australian urban general practitioners. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(7):980–985. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nikles J, Mitchell G, Walters J, et al. Prioritising drugs for single patient (n-of-1) trials in palliative care. Palliat Med. 2009;23(7):623–634. doi: 10.1177/0269216309106461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]