Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The risk of thrombocytopenia in patients undergoing aortic valve replacement (AVR) with the Freedom Solo (FS) bioprosthesis is controversial. The aim of our study was to evaluate the postoperative evolution of platelet count and function after AVR in patients undergoing isolated biological AVR with FS.

METHODS

Between May 2005 and June 2010, 322 patients underwent isolated biological AVR. Of these, 116 patients received FS and were compared with 206 patients who received biological valves. Platelet count, mean platelet volume (MPV), and platelet distribution width (PDW) were evaluated at baseline (T0), first (T1), second (T2), and fifth (T3) postoperative days, respectively.

RESULTS

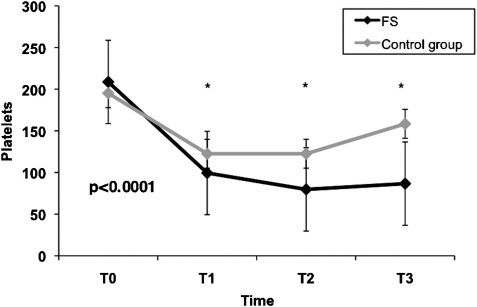

Overall in-hospital mortality was 1.5% with no difference between the two groups. Thirty-seven (11.5%) patients developed thrombocytopenia. FS implantation was associated with a higher incidence of thrombocytopenia compared with the control group (24.1% vs 4.4%, p < 0.0001). Patients in the FS group showed a lower platelet count than the control group at T1 (99.4 ± 38 × 103 μl−1 vs 122.5 ± 41.6 × 103 μl−1, p < 0.001), T2 (79.7 ± 36.3 × 103 μl−1 vs 122.5 ± 43.3 × 103 μl−1, p < 0.001) and T3 (86.6 ± 57.4 × 103 μl−1 vs 158.4 ± 55.8 × 103 μl−1, p < 0.001). Moreover, the FS group also had a higher MPV (11.6 ± 0.9 fl vs 11 ± 1 fl, p < 0.001) and higher PDW (15.1 ± 2.3 fl vs 13.9 ± 2.1 fl, p < 0.001) at T3. In a multivariable analysis, FS (p < 0.0001), body surface area (p < 0.0001), cardiopulmonary bypass time (p = 0.003), and lower preoperative platelet counts (p = 0.006) were independent predictors of thrombocytopenia.

CONCLUSIONS

The FS valve might increase the risk of thrombocytopenia and platelet activation, in the absence of adverse clinical events. Prospective randomized studies on platelet function need to confirm our data.

Keywords: Platelets, Aortic valve replacement, Stentless

INTRODUCTION

Freedom Solo (FS, Sorin Biomedica, Sallugia, Italy) is a new-generation stentless bioprosthesis valve, which has shown excellent early clinical and hemodynamic results after aortic valve replacement (AVR) [1–4]. Recently, small observational studies reported a higher incidence of thrombocytopenia and slower platelet count recovery associated with the implantation of FS, hypothesizing that it might induce a transient unspecific platelet activation [5–7]. However, these studies included patients receiving concomitant procedures, such as mitral valve surgery and coronary artery bypass grafting, which are known to increase cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) time, a potential risk factor for thrombocytopenia and platelet dysfunction [8,9]. Furthermore, van Straten et al., analyzing over 2000 patients undergoing AVR, found no differences between FS and other valve prostheses in terms of postoperative platelet-count reduction [10]. This phenomenon was not associated with any adverse clinical event. Consequently, the risk associated with FS on thrombocytopenia after AVR is still controversial.

Mean platelet volume (MPV) and platelet distribution width (PDW) have been described as simple markers of platelet function, which may increase during platelet activation; however, no studies conducted on FS have evaluated these indices [11]. The aim of our study was to evaluate the effect of FS in patients undergoing isolated AVR on postoperative thrombocytopenia and platelet function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective, observational, cohort study of prospectively collected data from consecutive patients, who underwent isolated biological AVR at our institution between May 2005 and June 2010. The study was approved by the local Ethical Committee and individual consent was waived. The data collection form is entered in a local database and includes three sections filled in by those – the anesthetists, cardiac surgeons, and perfusionists – involved in the care of the patients.

Exclusion criteria were active infective endocarditis, patients who received mechanical valve prosthesis, transcatheter aortic valve implantation, sutureless valves, and those in critical preoperative state defined as any one or more of the following: ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation, cardiac massage or aborted sudden death, ventilation before arrival in the anesthetic room, acute renal failure, and inotropic support. The sample consisted of 322 patients who underwent isolated biological AVR. Of these, 116 patients (36%) received FS and were compared with a control group of 206 patients who received stented valve bioprostheses (55.3% Carpentier Edwards Magna (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) and 8.7% Medtronic Mosaic (Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA)).

Blood samples and definitions

Venous blood samples were collected using Vacutainer® blood collection tubes with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). Platelet counts, MPV, and PDW were evaluated at baseline (T0), first (T1), second (T2), and fifth (T3) postoperative days, respectively, in order to asses changes after surgery. If more than one measure per patient per day was available, the lowest measure was recorded. Postoperative thrombocytopenia was defined as a platelet count of less than 50 × 103 μl−1 within the first 5 postoperative days. Preoperative baseline characteristic definition has been reported elsewhere [12]. In-hospital mortality was defined as any death occurring within 30 days of operation. A diagnosis of stroke was made if there was evidence of new neurological deficit with morphologic substrate that was confirmed by computer tomography or nuclear magnetic resonance imaging.

Anesthetic, surgical technique, and postoperative management

Anesthesia was undertaken with propofol and fentanyl, and was supplemented with inhaled isofluorane. Neuromuscular blockade was done by pancuronium or vecuronium. Surgical technique for FS has been reported previously [13]. In brief, FS valves were implanted with a continuous supra-annular suture line technique using three 4/0 prolene monofilament running sutures starting at the base of each sinus Valsalva and proceeding to the top of the commissures. Carpentier Edward and Mosaic valves were rinsed with sterile saline solution for at least 3 min and then implanted using interrupted pledget mattress sutures. After CPB, valve function was checked by intra-operative echocardiography. At the end of surgery, patients were transferred to the intensive care unit and managed according to the unit protocol. All patients received acetylsalicylic acid at a dose of 100 mg daily since the first postoperative day.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and categorical data as percentages. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to check for normality of data in the two groups before further analysis. To evaluate differences over time of platelet counts, MPV, and PDW within each group, repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) by Bonferroni method was used. Differences between the two groups were compared with the use of chi-square test for categorical variables and t-test or Wilcoxon rank sum test, as appropriate for continuous variable. To reduce the effect of selection bias and potential confounding in this observational study, a propensity score was undertaken [14]. The propensity for FS was determined regardless of outcomes by the use of a nonparsimonious multiple logistic-regression analysis. All the variables listed in Table 1 were included in the analysis. Finally, adjusted-propensity multivariable logistic-regression model was performed to identify independent risk factors for thrombocytopenia and results are reported as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). All reported p-values are two-sided, and p-values of <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analysis was performed with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics

| FS group (n = 116) | Control group (n = 206) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 73.1 ± 11.8 | 69.1 ± 8.3 | <0.0001 |

| Female | 87 (75) | 76 (36.9) | <0.0001 |

| Smokers | 27 (23.3) | 80 (38.8) | 0.006 |

| Hypertension | 96 (82.2) | 137 (66.5) | <0.003 |

| Diabetes | 23 (19.8) | 37 (18) | 0.79 |

| BSA | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 0.003 |

| NYHA lll-IV | 53 (45.7) | 50 (24.3) | <0.0001 |

| Creatinine | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 1 ± 0.2 | 0.46 |

| COPD | 5 (4.3) | 8 (3.9) | 1 |

| Arteriopathy | 18 (15.5) | 16 (7.8) | 0.47 |

| Redo | 3 (2.6) | 8 (3.9) | 0.76 |

| Previous neur events | 3 (2.6) | 1 (0.5) | 0.26 |

| Previous AF | 19 (16.4) | 31 (15) | 0.87 |

| EF (%) | 56.8 ± 9 | 55.7 ± 9.4 | 0.27 |

| Aspirin | 19 (16.4) | 23 (11.2) | 0.25 |

| LMWHs | 27 (23.3) | 32 (15.6) | 0.12 |

| Valve size | <0.0001 | ||

| 19 | 8 (6.9) | 5 (2.4) | |

| 21 | 45 (38.8) | 29 (14.1) | |

| 23 | 39 (33.6) | 60 (29.1) | |

| 25 | 20 (17.2) | 76 (36.9) | |

| 27 | 4 (3.4) | 35 (17) | |

| 29 | 0 | 1 (0.5) | |

| CPB (min, mean ± SD) | 115 ± 36.5 | 120.2 ± 34.3 | 0.2 |

| ACC (min, mean ± SD) | 79.7 ± 23.8 | 85.4 ± 25.2 | 0.049 |

Values are expressed as n (%) unless specified otherwise.

NYHA: New York Heart Association; BSA: body surface area; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; AF: atrial fibrillation; EF: ejection fraction; LMWHs: low molecular weight heparins; CPB: cardiopulmonary bypass; and ACC: aortic cross-clamping.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Compared with the control group, the patients receiving FS were older, had a smaller body surface area (BSA), and higher prevalence of female sex; they were more likely to have a higher prevalence of hypertension, greater New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, and smaller valve prosthesis size. Finally, FS group also had a higher platelet count and a shorter aortic cross-clamping time. Overall in-hospital mortality was 1.5% with no difference between the two groups (three patients, 2.6% in FS group vs two patients, 1% in control group, p = 0.5). No differences were found in terms of stroke (two patients, 1.7% vs one patient, 0.5%, p = 0.26) and need of re-exploration for bleeding (seven patients, 6% vs eight patients, 3.9%, p = 0.5).

Platelet counts and MPV and PDW measurements

The platelet counts and MPV and PDW measurement are shown in Table 2. Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed that differences in platelet counts, MPV, and PDW were significant over time within groups compared with the baseline values (p < 0.0001). All patients experienced a reduction of platelet counts after AVR replacement. Compared with the initial values, platelet count had a negative peak at T2 and increased at T3; however, a significant lower platelet count was found in patients receiving FS than the control group at T1 (p < 0.0001), T2 (p < 0.0001) and T3 (p < 0.0001), respectively (Fig. 1, Table 2).

Table 2:

Platelet counts, mean platelet volume and platelet distribution width

| FS group (n = 116) | Control group (n = 206) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLTO (103 μl−1) | 208.7 ± 56.7 | 195.2 ± 58.4 | 0.045 |

| PLT1 (103 μl−1) | 99.4 ± 38.3 | 122.5 ± 41.6 | <0.0001 |

| PLT2 (103 μl−1) | 79.7 ± 36.3 | 122.5 ± 43.3 | <0.0001 |

| PLT3 (103 μl−1) | 86.6 ± 57.4 | 158.4 ± 55.8 | <0.0001 |

| MPVO (fl) | 10.9 ± 0.8 | 10.9 ± 1 | 0.8 |

| MPV1 (fl) | 11.5 ± 0.9 | 11.3 ± 0.9 | 0.22 |

| MPV2 (fl) | 11.7 ± 0.8 | 11.5 ± 0.9 | 0.07 |

| MPV3 (fl) | 11.6 ± 0.9 | 11 ± 1 | <0.0001 |

| PDWO (fl) | 13.3 ± 1.7 | 13.6 ± 1.9 | 0.17 |

| PDW1 (fl) | 14.2 ± 1.9 | 14.3 ± 2.1 | 0.91 |

| PDW2 (fl) | 15.4 ± 2.4 | 14.7 ± 2.3 | 0.03 |

| PDW3 (fl) | 15.1 ± 2.3 | 13.9 ± 2.1 | <0.0001 |

PLT: platelets; MPV: mean platelet volume; and PDW: platelet distribution width.

Figure 1:

Platelet count during different times between FS and control group.

An increase of MPV and PDW was observed in both the groups as well (p < 0.0001, respectively). Analysis between the groups showed that MPV was significantly higher at T3 (p < 0.0001) and PDW was significantly higher at T2 (p = 0.03) and T3 (p < 0.0001) in the FS group compared with the control group (Table 2).

Thrombocytopenia

A total of 37 (11.5%) of the 322 patients had thrombocytopenia after AVR. FS implantation was associated with a higher incidence of thrombocytopenia compared with the control group (28/116 patients, 24.1% vs 9/206 patients, 4.4%, p < 0.0001). Moreover, patients who developed thrombocytopenia were older, had lower BSA, smaller valve size, and longer CPB time. In an adjusted-propensity multivariable analysis, CPB time (OR 1.02, 95%CI: 1.006–1.028, p < 0.003), preoperative platelet count (OR 0.98, 95%CI: 0.97–0.99, p = 0.006), BSA (OR 0.01, 95%CI: 0.001–0.11, p < 0.0001), and FS valve (OR 9.5, 95%CI: 3.5–25.7, p < 0.0001) were independent predictors of postoperative thrombocytopenia after AVR (Table 3).

Table 3:

Propensity-adjusted multivariable analysis of thrombocytopenia

| Variable | OR | 95%CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| FS valve | 9.5 | 3.5–25.7 | <0.0001 |

| Preoperative platelet count (103 μl−1) | 0.98 | 0.97–0.99 | 0.006 |

| BSA | 0.1 | 0.001–0.11 | <0.0001 |

| CPB time (min) | 1.02 | 1.006–1.028 | 0.003 |

FS: Freedom Solo; BSA: body surface area; and CPB: cardiopulmonary bypass.

DISCUSSION

The present study shows that patients undergoing FS implantation may have more probability to develop postoperative thrombocytopenia, defined as a platelet count of less than 50 × 109 l−1 within the first 5 postoperative days. In addition, prolonged CPB time, preoperative platelet count, and BSA were independent predictors of low platelet count.

Thrombocytopenia after CPB is a transient and common event in cardiac surgery, mainly secondary to hemodilution, platelet consumption, and perioperative blood loss. It usually occurs between the second and third postoperative days, resulting in a reduction of platelet counts by 30–60% from baseline values [8,9,15,16]. We found that postoperative platelets declined in both the groups after AVR (Fig. 1); however, patients with FS showed a significant lower platelet count compared with the control group on the second and fifth postoperative days. Furthermore, MPV and PDW increased in all patients as well; however, MPV and PDW were statistically higher in the FS group on the fifth postoperative day, indicating that FS valve might induce platelet activation.

The FS is a new-generation bovine pericardium stentless bioprosthesis valve, implanted in a supra-annular position using a single running suture. As an evolution of the Pericarbon Freedom, FS has shown excellent early and hemodynamic results, resulting in a significant regression of the left hypertrophy and improvement in left ventricular systolic function [1–4]. Nevertheless, recent reports showed an increased risk in the incidence of postoperative thrombocytopenia after FS implantation. Yerebakan et al. and Hilker et al. described a lower platelet count between the second and third postoperative day in patients receiving FS valve compared with other bioprostheses [6,7]. Moreover, Piccardo et al., after matching for propensity score, found that more than 50% of patients receiving FS developed severe or moderate thrombocytopenia in the immediate postoperative period versus 24.1% in our experience [5]. The main limitation of these reports was the inclusion of patients undergoing combined surgery, such as mitral valve replacement or repair, coronary artery bypass grafting, and Maze procedures for atrial fibrillation, which increase CPB time.

The cause of thrombocytopenia is unknown and under investigation at our institution. An emergent hypothesis is a transitory direct toxic effect of FS on platelets, caused by the storage solution. Similar to other valves, FS is fixed in a glutaraldehyde but it does not require rinsing prior to implant because it is detoxified with homocysteic acid and stored in aldehyde-free solution. Homocysteic acid could activate several molecular mechanisms resulting in platelet activation and thrombocytopenia [17]; however, the same solution is used for other Sorin bioprostheses. To the best of our knowledge, no reports of thrombocytopenia have been described related to these valves. In a recent study, Santarpino et al. found that platelet count was significantly reduced in patients with FS but not in those with Sorin Freedom [18,19]. These results suggest a different mechanism than toxicity. Furthermore, it is important to underline that homocysteic acid is present in healthy humans as a product of the spontaneous oxidization of homocysteine (10–15 μl l−1 being the physiological concentration of homocysteine and its derivates in healthy adults) [20]. FS valves are detoxified with homocysteic acid but, after the treatment, are carefully washed with a homocysteic acid-free solution, having the same composition of the final storage liquid. The valve jars are then filled with a fresh aliquot of storage solution. As a consequence, the residual amount of homocysteic acid, which could be transferred to the patient during the valve implantation, is negligible and the resulting concentration in blood is extremely low, by far below normal physiological values. A second consideration could be the micro-hemodynamic effects of the prosthetic structure or the implant technique. However, a direct mechanical stress on platelets is improbable considering the superior hemodynamic properties of FS. In addition, the technique of implantation in the supra-annular position has been used for the O’Brien Cryolife porcine stentless (Cryolife Inc., Kennesaw, GA, USA) without any report of thrombocytopenia [21,22].

Le Guyader et al. observed that platelet activation, assessed by specific indices such as P-selectin, platelet–leukocyte conjugate formation, and platelet microparticles, may be induced by either bioprostheses or mechanical valves [23]. Contrary to these expensive and laborious markers, MPV and PDW have been described as simple indices of platelet function that increase during platelet activation [11]. Our study showed that MPV and PDW increased over time in all patients undergoing AVR. However, they were higher in patients with FS compared with the control group on the fifth postoperative day. This observation could lead to the conclusion that that FS may induce thrombocytopenia through platelet activation. However, it is difficult to understand if there is a real clinical significance, because the mean absolute difference between the two groups was very small.

This study has several limitations. It is based on the retrospective analysis of our institutional observational prospectively collected database and we are unable to account for the influence of any residual unmeasured factors that could affect thrombocytopenia. Although the number of patients is small, this is the largest study which evaluates the thrombocytopenia phenomenon. Finally, we did not investigate on heparin-induced thrombocytopenia as a possible cause of platelet-count reduction.

In conclusion, FS valve seems to be associated with an increase in the risk of postoperative thrombocytopenia and platelet activation. However, as shown in other studies no adverse outcomes were related to FS valve. Prospective randomized studies with large sample size are required to confirm our data.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Repossini A, Kotelnikov I, Bouchikhi R, Torre T, Passaretti B, Parodi O, Arena V. Single-suture line placement of a pericardial stentless valve. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:1265–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beholz S, Repossini A, Livi U, Schepens M, Gabry M, Matschke, Trivedi U, Eckel L, Dapunt O, Zamorano JL. The Freedom SOLO valve for aortic valve replacement: clinical and hemodynamic results from a prospective multicenter trial. J Heart Valve Dis. 2010;19:115–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oses P, Guibaud JP, Elia N, Dubois G, Lebreton G, Pernot M, Roques X. Freedom Solo valve: early- and intermediate-term results of a single centre’s first 100 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;39:256–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aymard T, Eckstein F, Englberger L, Stalder M, Kadner A, Carrel T. The Sorin Freedom SOLO stentless aortic valve: technique of implantation and operative results in 109 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:775–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piccardo A, Rusinaru D, Petitprez B, Marticho P, Vaida I, Triboulloy C, Caus T. Thrombocytopenia after aortic valve replacement with freedom solo bioprosthesis: a propensity study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:1425–31. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hilker L, Wodny M, Ginesta M, Wollert HG, Eckel L. Differences in the recovery of platelet counts after biological aortic valve replacement. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2009;8:70–4. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2008.188524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yerebakan C, Kaminski A, Westphal B, Kundt G, Ugurlucan M, SteinhoffG, Liebold A. Thrombocytopenia after aortic valve replacement with freedom solo stentless bioprosthesis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2008;7:616–20. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2007.169326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weerasinghe A, Taylor KM. The platelets in cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:2145–52. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)00749-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawahito K, Kobayashi E, Iwasa H, Misawa Y, Fuse K. Platelet aggregation during cardiopulmonary bypass evaluated by a laser light scattering method. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:79–84. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)00821-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Straten AH, Hamad MA, Berreklouw E, Woorst JF, Martens EJ, Tan ME. Thrombocytopenia after aortic valve replacement: comparison between mechanical and biological valves. J Heart Valve Dis. 2010;19:394–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vagdatli E, Gounari E, Lazaridou E, Katsibourlia E, Tsikopoulou F, Labrianou I. Platelet distribution width: a simple, practical and specific marker of activation of coagulation. Hippokratia. 2010;14:28–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roques F, Nashef SAM, Micheal P, Gauducheau E, de Vincentiis C, Baudet E, Cortina J, David M, Faichney A, Gabrielle F, Gams E, Harjula A, Jones MT, Pintor PP, Salamon R, Thulin L. Risk factors and outcome in European cardiac surgery: analysis of the EuroSCORE multinational database of 19030 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;15:816–23. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(99)00106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glauber M, Solinas M, Karimov J. Technique for implant of the stentless aortic valve Freedom Solo. MMCTS. doi: 10.1510/mmcts.2007.002618. doi:10.1510/mmcts.2007.002618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blackstone EH. Comparing apples and oranges. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;123:8–15. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.120329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warkentin TE, Greinacher A. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:2121–31. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thielmann M, Bunschkowski M, Tossios P, Selleng S, Marggraf G, Greinacher A, Jacob H, Massoudy P. Perioperative thrombocytopenia in cardiac surgical patients—incidence of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, morbidities and mortality. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;37:1391–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albaker TB. Invited commentary. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:1430–1. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santarpino G, Fischlein T, Pfeiffer S. Thrombocytopenia after Sorin Freedom Solo valve implantation: is there a clinical relevance? Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;58:V83. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santarpino G, Fischlein T, Pfeiffer S. Thrombocytopenia after freedom solo: the mystery goes on. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:330. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boldyrev AA. Molecular mechanisms of homocysteine toxicity. Biochemistry. 2009;74:589–98. doi: 10.1134/s0006297909060017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Brien MF. The Cryolife-O’Brien stentless xenograft aortic valve: surgical technique of implantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60(2 Suppl.):S410–3. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00267-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Brien MF, Gardener MAH, Garlik B, Jalali H, Gordon JA, Whitehouse SL, Strugnell WE, Slaughter R. CryoLife-O’Brien stentless valve: 10-year results of 402 implants. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:757–66. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Guyader A, Watanabe R, Berbè J, Boumediene A, Cognè M, Laskar M. Platelet activation after aortic prosthetic valve surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2006;5:60–4. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2005.115733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]