Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The advent of percutaneous aortic valve implantation has increased interest in the outcomes of conventional aortic valve replacement in elderly patients. The current study critically evaluates the short-term and long-term outcomes of elderly (≥80 years) Australian patients undergoing isolated aortic valve replacement.

METHODS

Data obtained prospectively between June 2001 and December 2009 by the Australasian Society of Cardiac and Thoracic Surgeons National Cardiac Surgery Database Program were retrospectively analysed. Isolated aortic valve replacement was performed in 2791 patients; of these, 531 (19%) were at least 80 years old (group 1). The patient characteristics, morbidity and short-term mortality of these patients were compared with those of patients who were <80 years old (group 2). The long-term outcomes in elderly patients were compared with the age-adjusted Australian population.

RESULTS

Group 1 patients were more likely to be female (58.6% vs 38.0%, p < 0.001) and presented more often with co-morbidities including hypertension, cerebrovascular disease and peripheral vascular disease (all p < 0.05). The 30-day mortality rate was not independently higher in group 1 patients (4.0% vs 2.0%, p = 0.144). Group 1 patients had an independently increased risk of complications including new renal failure (11.7% vs 4.2%, p < 0.001), prolonged (≥24 h) ventilation (12.4% vs 7.2%, p = 0.003), gastrointestinal complications (3.0% vs 1.3%, p = 0.012) and had a longer mean length of intensive care unit stay (64 h vs 47 h, p < 0.001). The 5-year survival post-aortic valve replacement was 72%, which is comparable to that of the age-matched Australian population.

CONCLUSION

Conventional aortic valve replacement in elderly patients achieves excellent outcomes with long-term survival comparable to that of an age-adjusted Australian population. In an era of percutaneous aortic valve implantation, it should still be regarded as the gold standard in the management of aortic stenosis.

Keywords: Cardiac surgery, Aortic valve replacement, Octogenarian, Mortality, Morbidity, Survival

INTRODUCTION

The continually rising global life expectancy has resulted in a significantly increased population over the age of 80 years. People aged 85 years and above are predicted to make up 5–7% of the Australian population, as compared with the existing 1.6%, within the next few decades [1]. Aortic stenosis (AS) is the most common valvular lesion amongst the elderly in Western populations. As an age-progressive disease, prevalence of AS has been found to increase from 2.5% at 75 years to 8.1% at 85 years [2].

Despite recent advances of trans-catheter aortic valve replacement as a potential treatment option, conventional open heart aortic valve replacement (AVR) remains the only definite treatment for AS which improves long-term survival [3]. The operative risk of AVR has constantly improved over the recent years, with large studies showing in-hospital mortality rates as low as 0.5% [4]. Contemporary data have demonstrated that the survival of appropriately selected octogenarians is comparable to that of younger patients. However, up to one-third of octogenarian patients with symptomatic AS continue to be denied surgery solely based on their age [5]. This is likely as a consequence of inconsistent survival data amongst octogenarians reported in past studies, with perioperative mortality rates varying from 0% to 11.7% [4,6,7]. Large-cohort studies investigating long-term outcomes post AVR are also scarce.

We examined the short-and long-term outcomes of AVR in a cohort of 2790 consecutive patients, comparing the morbidity and mortality rates between octogenarians and non-octogenarians.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The inclusion criterion for the study was all patients undergoing isolated AVR between 1 June 2001 and 31 December 2009 at hospitals in Australia participating in the Australasian Society of Cardiac and Thoracic Surgeons (ASCTS) National Cardiac Surgery Database Program. Patients having concomitant coronary artery bypass graft surgery or other concurrent cardiac surgical procedures were excluded from this study. All six Victorian public hospitals that perform adult cardiac surgery – The Royal Melbourne Hospital, The Alfred Hospital, Monash Medical Centre, The Geelong Hospital, Austin Hospital, and St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne – were involved in the prospective data collection during the entire period. In addition, 14 cardiac surgical units from South Australia, New South Wales, and Queensland have entered the database project in the last 30 months of the study period and contributed 32% of the total patient numbers.

The ASCTS database contains detailed information on patient demographics, preoperative risk factors, operative details, postoperative hospital course and morbidity and mortality outcomes. These data were collected prospectively using a standardised data set and definitions. Data collection and audit methods have been previously described. In the State of Victoria, the collection and reporting of cardiac surgery data is mandated by the State Government; hence, it is all inclusive. Data validation has been a major focus since the establishment of the ASCTS database. The data are subjected to both local validation and an external data-quality audit program, which is performed on site to evaluate the completeness (defined as <1% missing data for any variable) and accuracy (97.4%) of the data held in the combined database. Audit outcomes are used to assist in further development of appropriate standards. The Ethics Committee of each participating hospital had previously approved the use of deidentified patient data contained within the database for research and waived the need for individual patient consent.

For the purpose of this study, patients were divided into two groups: those undergoing isolated AVR who were ≥80 years of age and those undergoing isolated AVR who were <80 years of age. Preoperative characteristics, early outcomes and long-term survival were compared between the two groups.

Eleven early postoperative outcomes were analysed. These were: (1) 30-day mortality, defined as death within 30 days of operation; (2) permanent stroke, defined as a new central neurologic deficit persisting for >72 h; (3) postoperative acute myocardial infarction (AMI), defined as at least two of the following: enzyme level elevation, new cardiac wall motion abnormalities, or new Q waves on serial electrocardiograms; (4) new renal failure, defined as at least two of the following – serum creatinine increased to more than 200 μmol l−1, doubling or greater increase in creatinine versus preoperative value, or new requirement for dialysis or haemofiltration; (5) prolonged ventilation (>24 h); (6) multi-system failure, defined as concurrent failure of two or more of the cardiac, respiratory, or renal systems for at least 48 h; (7) septicaemia, defined as positive blood cultures supported by at least two of the following indices of clinical infection – fever, elevated granulocyte cell counts, elevated and increased CRP and elevated and increased ESR, postoperatively; (8) gastrointestinal (GI) complications, defined as postoperative occurrence of any GI complication; (9) deep sternal wound infection involving muscle and bone, as demonstrated by the need for surgical exploration and one of the following – positive cultures or treatment with antibiotics; (10) return to the operating theatre for any cause; and (11) return to the operating theatre for bleeding. The diagnosis of stroke was made clinically and usually confirmed by neurology review and supported by imaging, as dictated by the institution.

To assess the role of octogenarian status as a predictor for each early outcome, logistic regression analysis was used to adjust for 17 preoperative patient variables, with the outcome as the dependent variable (variables in Table 4). Long-term survival status was obtained from the National Death Index. The closing date was 18 March 2010. A Kaplan–Meier estimate of survival was obtained. Survival was compared with age- and sex-matched population life estimates from the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Differences in long-term survival were assessed by the log-rank test. The role of octogenarian status in long-term survival was assessed by constructing a Cox proportional hazards model using octogenarian status and other preoperative patient characteristics as variables. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± one standard deviation. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare two groups of continuous variables. The Fisher exact test or the chi-square test was used to compare groups of categorical variables. All calculated values of p were two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS®) for Windows version 17.0 (SPSS, Munich, Germany).

Table 4:

Predictors for 30-day and late mortality

| Preoperative variables | 30–day mortality | Late mortality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age >80 | 1.58 (0.86–2.90) | 0.144 | 2.48 (1.91–3.23) | <0.001 |

| Female | 1.16 (0.66–2.05) | 0.605 | 1.04 (0.81–1.33) | 0.768 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 2.04 (1.12–3.72) | 0.019 | 1.43 (1.09–1.89) | 0.011 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.99 (1.10–3.62) | 0.023 | 1.75 (1.34–2.29) | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 1.37 (0.75–2.50) | 0.308 | 1.05 (0.82–1.35) | 0.700 |

| Hypertension | 0.79 (0.42–1.49) | 0.468 | 1.05 (0.80–1.37) | 0.752 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.94 (0.98–3.87) | 0.059 | 1.71 (1.23–2.37) | 0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.21 (0.52–2.86) | 0.658 | 1.09 (0.71–1.67) | 0.695 |

| Renal failure | 5.18 (1.74–15.45) | 0.003 | 3.38 (1.99–5.72) | <0.001 |

| Critical preoperative state | 0.73 (0.46–1.15) | 0.176 | 1.16 (0.66–2.05) | 0.600 |

| Coronary artery disease | 0.55 (0.21–1.44) | 0.221 | 1.02 (0.68–1.53) | 0.937 |

| Body mass index (mean) | 0.96 (0.91–1.01) | 0.130 | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 0.011 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 2.22 (1.06–4.62) | 0.034 | 1.27 (0.87–1.84) | 0.214 |

| History of congestive heart failure (%) | 2.03 (1.11–3.71) | 0.022 | 1.52 (1.19–1.96) | 0.001 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction <0.45 | 1.71 (0.92–3.17) | 0.088 | 1.35 (1.01–1.82) | 0.042 |

| New York Heart Association classification III or IV | 1.52 (0.83–2.77) | 0.177 | 1.40 (1.09–1.80) | 0.008 |

| Non-elective procedure | 1.95 (1.08–3.53) | 0.028 | 1.06 (0.79–1.42) | 0.681 |

RESULTS

Patient demographics and preoperative variables

Of 2790 patients who met the study inclusion criteria, 531 (19.0%) were aged 80 years and over (group 1), whereas 2259 (81.0%) were aged <80 years (group 2). The mean age in group 1 was 83.39 ± 2.96 years compared with 64.93 ± 12.05 in group 2. Group 1 patients were more likely to be female (59.6% vs 38.0%, p < 0.001). Preoperative and demographic characteristics of the two groups are provided in Table 1.

Table 1:

Preoperative characteristics and patient demographics, stratified by age

| Preoperative variables | Age <80 years | ≥80 years | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients (%) | 2259 (80.97) | 531 (19.03) | – |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 64.93 (12.05) | 83.39 (2.96) | <0.001 |

| Male (%) | 1401 (62.0) | 220 (41.4) | <0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (%) | 319 (14.1) | 87 (16.4) | 0.183 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 508 (22.5) | 103 (19.4) | 0.120 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia (%) | 1115 (49.5) | 265 (50) | 0.840 |

| Hypertension (%) | 1455 (64.4) | 384 (72.3) | 0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease (%) | 208 (9.2) | 73 (13.8) | 0.002 |

| Peripheral vascular disease (%) | 128 (5.7) | 45 (8.5) | 0.016 |

| Renal failure (%) | 84 (3.7) | 7 (1.3) | 0.005 |

| Previous percutaneous coronary intervention (%) (744) | 79 (13.4) | 29 (18.6) | 0.124 |

| Previous myocardial infarction (%) | 161 (7.1) | 61 (11.5) | 0.001 |

| History of congestive heart failure (%) | 834 (36.9) | 215 (40.5) | 0.135 |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 184 (8.3) | 69 (13.1) | 0.001 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (n = 2705) | – | – | 0.538 |

| Normal (EF > 0.60) (%) | 1397 (63.7) | 310 (60.5) | |

| Mild (EF > 0.45) (%) | 499 (22.8) | 122 (23.8) | – |

| Moderate (EF 0.30–0.45) (%) | 202 (9.2) | 55 (10.7) | – |

| Severe (EF < 0.30) (%) | 95 (4.3) | 25 (4.9) | – |

| Body mass index (mean ± SD) | 29.2 | 26.8 | <0.001 |

| New York Heart Association classification (n = 2722) | – | – | <0.001 |

| Class 1 (%) | 401 (18.2) | 69 (13.2) | – |

| Class II (%) | 853 (38.8) | 173 (33.1) | – |

| Class III (%) | 785 (35.7) | 238 (45.6) | – |

| Class IV (%) | 161 (7.3) | 43 (8.2) | – |

| Status | – | – | 0.113 |

| Elective (%) | 1884 (83.4) | 427 (80.4) | – |

| Emergency/salvage (%) | 27 (1.2) | 4 (0.75) | – |

| Urgent (%) | 348 (15.4) | 100 (18.8) | – |

| Critical preoperative state (%) | 90 (4.0) | 4 (0.7) | <0.001 |

Intraoperative data

There were some differences in intraoperative variables between the two groups (Table 2). The duration of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) support and aortic cross-clamping were generally shorter in group 1 patients (p < 0.001). Group 1 patients were more likely to receive a bioprosthetic valve compared with group 2 patients (92.7% vs 59.9%, p < 0.001). The mean size of the implanted valve was smaller in group 1 patients (22.40 ± 2.23 mm vs 23.44 ± 2.38 mm, p < 0.001). The mean size of the implanted valve was also significantly smaller in group 1 women compared with men (21.20 ± 1.75 mm vs 23.60 ± 1.81 mm, p < 0.001). Consultant surgeons were observed to perform surgery more in group 1 patients compared with group 2, but this was not statistically significant (87.7% vs 84.9%, p = 0.064).

Table 2:

Intraoperative characteristics, stratified by age

| Preoperative variables | Age <80 years | Age ≥80 years | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients (%) | 2259 (80.97) | 531 (19.03) | - |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass time (min) | – | – | 0.008 |

| ≤ 80 | 610 (27) | 172 (32.4) | – |

| 81–120 | 1160 (51.3) | 271 (51.0) | – |

| > 120 | 488 (21.6) | 88 (16.6) | – |

| Aortic cross-clamp time (min) | – | – | 0.002 |

| ≤ 60 | 642 (28.4) | 188 (35.4) | – |

| 61–90 | 1088 (48.2) | 244 (46.0) | – |

| > 90 | 529 (23.4) | 98 (18.5) | – |

| Type of prosthesis | – | – | <0.001 |

| Bioprosthesis | 1352 (59.9) | 492 (92.7) | – |

| Mechanical valve | 831 (36.8) | 14 (2.6) | – |

| Homograft | 20 (0.9) | 2 (0.4) | – |

| Valve size (mean ± SD) | 23.44 (2.23) | 22.40 (2.38) | <0.001 |

Early outcomes

Significant differences between the groups were documented in early postoperative outcomes (Table 3). Overall 30-day mortality was 2.3%, and the 30-day mortality was 4.0% in group 1 and 2.0% in group 2. After adjustment for differences in patient variables, elderly status was not a predictor for 30-day mortality (odds ratio (OR), 1.58; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.86–2.90, p = 0.144). Elderly status was associated with new renal failure (odds ratio (OR), 2.88; 95% CI, 1.98–4.19, p < 0.001), prolonged ventilation (OR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.19–2.36, p = 0.003) and GI complications (OR, 2.48; 95% CI, 1.22–5.05, p = 0.012). The logistic regression model predicting 30-day mortality is shown in Table 4. Group 1 patients had a significantly higher mean postoperative length of stay (11.7 ± 9.6 days vs 9.6 ± 9.3 days, p < 0.001) and intensive care unit stay (63.6 ± 90.9 h vs 46.8 ± 82.6 h, p < 0.001) compared with group 2 patients.

Table 3:

Early outcomes, stratified by age

| Outcome | Age <80 years | Age >80 years | P | Age >80 years Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permanent stroke (%) | 22 (1.0) | 12 (2.3) | 0.285 | 1.59 (0.68-3.70) |

| Postoperative myocardial infarction (%) | 9 (0.4) | 3 (0.6) | 0.964 | 0.97 (0.21-4.39) |

| New renal failure (%) | 95 (4.2) | 62 (11.7) | <0.001 | 2.88 (1.98-4.19) |

| Deep sternal wound infection (%) | 5 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | 0.696 | 1.43 (0.24-8.72) |

| Septicaemia (%) | 25 (1.1) | 8 (1.5) | 0.481 | 1.40 (0.55-3.52) |

| Multi-system failure (%) | 24 (1.1) | 9 (1.7) | 0.180 | 1.79 (0.76-4.20) |

| Permanent pacemaker (%) | 27 (1.2) | 21 (4.0) | <0.001 | 3.26 (1.77-6.02) |

| Prolonged ventilation (%) | 161 (7.1) | 66 (12.4) | 0.003 | 1.68 (1.19-2.36) |

| Gastrointestinal complications (%) | 29 (1.3) | 16 (3.0) | 0.012 | 2.48 (1.22-5.05) |

| Return to theatre (%) | 173 (7.7) | 54 (10.2) | 0.206 | 1.25 (0.88-1.78) |

| Return to theatre for bleeding (%) | 91 (4.0) | 19 (3.6) | 0.340 | 0.77 (0.45-1.32) |

Late outcomes

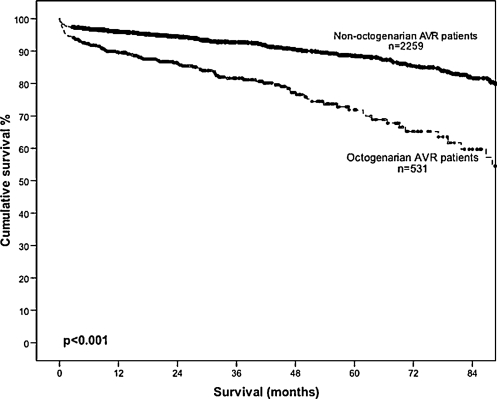

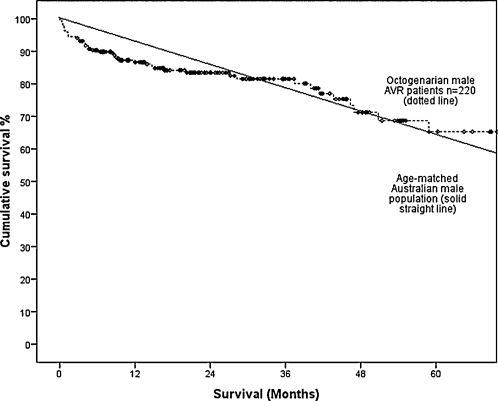

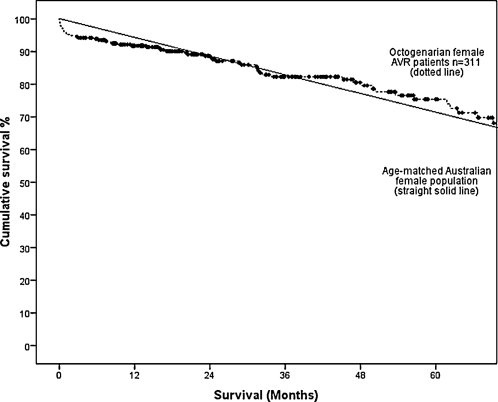

Long-term survival at 1, 3, 5 and 7 years postoperatively was lower in group 1 compared with group 2 (89.7% vs 95.9%, 81.6% vs 92.8%, 71.9% vs 88.6% and 59.7% vs 81.6%; Fig. 1). This difference persisted after adjusting for difference in patient variables (OR, 2.48; 95% CI, 1.91–3.23; p < 0.001). However, the survival of elderly patients post AVR is comparable survival to an age- and sex-adjusted Australian population data. The 5-year survival of male elderly patients undergoing AVR (mean age, 83.4 years) at 65% is comparable to the expect survival of age-matched Australian males (mean age, 83 years) at 64.3% (Fig. 2). Similarly, the 5-year survival of female elderly patients undergoing AVR (mean age, 83.4 years) at 75.4% is comparable to the age-adjusted survival of age-matched Australian females (mean age, 83 years) at 72.3% (Fig. 3). A Cox regression model predicting late mortality is summarised in Table 4. Apart from age, other factors associated with survival included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (OR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.09–1.89), diabetes mellitus (OR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.34–2.29), cerebrovascular disease (OR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.23–2.37), renal failure (OR, 3.38; 95% CI, 1.99–5.72), congestive heart failure (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.19–1.96), left ventricular ejection fraction <0.45 (OR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.01–1.82) and New York Heart Association classification III or IV (OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.09–1.80).

Figure 1:

Overall survival in patients undergoing isolated AVR, stratified by age.

Figure 2:

Overall survival in male octogenarian patients undergoing isolated AVR compared to the age-matched Australian male population.

Figure 3:

Overall survival in female octogenarian patients undergoing isolated AVR compared to the age-matched Australian female population.

DISCUSSION

The natural course of disease progression of AS typically comprises a long asymptomatic phase lasting a few decades before a significantly shorter symptomatic phase resulting from severe narrowing of the aortic valve orifice. Patients with asymptomatic AS have comparable life expectancy as age- and sex-matched controls [8]. However, the onset of symptoms portends a poor prognosis, with a predicted 3-year survival for patients presenting with angina and syncope and only 1 year for patients who have developed left-ventricular failure [9,10]. Hence, the development of symptoms is a definite indication for AVR to be promptly performed.

The therapeutic benefits of AVR remain true for the extremes of age. Varadarajan and colleagues [15] revealed a dramatically improved 5-year survival in octogenarians who underwent AVR compared with conservative management (68% vs 22%). Despite the consensus regarding the survival benefits of AVR, there is reluctance in offering surgery to this high-risk population. This is likely due to previous studies reporting elevated operative mortality rates of up to 14% in elderly patients [11]. However, much effort has been invested over the past decade in advancing the surgical efficacy of AVR and lowering the operation-associated mortality.

Our findings revealed an overall 30-day mortality of 2.3% for the entire cohort, and 4.0% amongst the octogenarians. This compares favourably with the short-term mortality findings from other published studies and provides evidence that surgery is the best treatment option for AS, even in elderly patients. A study reviewing post-AVR outcomes in octogenarian patients conducted by Kolh and colleagues revealed a higher 30-day mortality of 10% [6]. More recently, Likosky and colleagues conducted a large registry study, comprising of 575 patients older than 80 years and a total cohort size of 7584 patients, which found a 6.7% and 11.7% 30-day mortality for the 80–84 years and ≥85 years’ age group, respectively. The results revealed a strong statistically significant relation between older age and increased 30-day mortality (p < 0.001) [7]. This, however, was not illustrated in our results, which showed no significant relation between age >80 years and 30-day mortality. Overall, the low 30-day mortality in the current study provides good evidence that surgical AVR should remain the gold standard in the treatment of AS.

Despite the encouraging short-term outcomes, it is undeniable that octogenarians more frequently encounter stormy recoveries postoperatively. Our results showed significantly greater incidence of renal failure, GI complications, and prolonged ventilation in elderly patients. Filsoufi and colleagues similarly encountered challenges with the delicate balance of maintaining respiratory function in the elderly population, revealing a much higher prevalence of postoperative respiratory failure amongst octogenarians as compared with non-octogenarians (12.6% vs 7.4%, p = 0.01) [12]. There is also an increased frequency of new renal failure in the elderly population. However, this renal insufficiency is likely transient. A similar study found that, despite the higher rate of developing renal failure, there was no increased risk of developing severe renal failure requiring dialysis, amongst octogenarians [4]. Octogenarians were also found to require longer intensive care and hospitalisation. This is a common finding in most existing literature [4,7,12], and are an anticipated sequelae considering the increased postoperative morbidity found in the elder cohort.

The long-term survivorship of a patient postoperatively is an important factor in determining whether an intervention should be performed. Our study findings revealed that post-AVR patients had life expectancies comparable to their age- and sex-matched Australian peers. Our 5-year survival rate of 71.9% amongst the older patients is in agreement with existing long-term survival analyses of octogenarians post AVR. Recent studies have also shown excellent outcomes with 5-year survival ranging between 54.7% and 75.7% [6,7,12–15]. These excellent data thereby provide strong evidence to suggest that conventional AVR is the ‘gold standard’ treatment option for AS.

Especially in an elderly population, preservation of quality of life is imperative. Kolh and colleagues assessed the quality of life in 130 patients on follow-up post AVR and found that 81% had New York Heart Association (NYHA) scores of II or less, and 54% were angina free [6]. Huber and colleagues similarly reviewed postoperative quality of life amongst octogenarians after cardiac surgery, and found that 93% of patients experienced improvements symptomatically and 97% remained capable of maintaining acceptable self-care [16].

Risk evaluation using the logistic European System for Cardiac Operating Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE) has been found to overestimate the perioperative mortality amongst octogenarians undergoing AVR. It, however, proved to be a relatively efficient predictor of long-term survival [17]. Its prognostic performance has been found to be generally poor in AVR patients and progressively worsens with increased individual risk, such as for patients of older age [18]. Hence, a high EuroSCORE should not lead to indiscriminate denial of intervention to octogenarians.

In view of the significantly improved mortality rates associated with AVR, the approach of operating only on patients with severe symptomatic AS should be reassessed. This is especially crucial in light of emergency/urgent surgery being a well-recognised predictor of perioperative and long-term mortality [19,20]. Patients should be managed more promptly and aggressively at earlier stages of the disease to avoid acute deterioration, hence lessening the chances of requiring emergency intervention.

This is the largest AVR registry study in Australia till date. As one of the few studies comparing post-AVR outcomes between octogenarians and non-octogenarians, the findings provide insight into the viability of surgery for this specific group. This study also highlights the need for further investigation. For example, elderly patients were observed to have shorter CPB times compared with younger patients. Whilst this may be attributed to the fact that senior surgeons, who are generally quicker, are more likely to operate on elderly patients, our study suggests an unexplained cause for this disparity may exist. Further investigation is clearly necessary. The main limitation is that it is a retrospective review, and although capturing all surgical patients, there is potential selection bias that would have precluded a fair comparison between men and women.

Overall, the results in the current study are amongst the best reported in a large group of patients undergoing isolated AVR. They provide strong evidence, in an era of percutaneous AVR that conventional AVR should remain the ‘gold standard’ in the treatment of AS, even in selected elderly patients. In fact, our data suggest that the patient-selection process may therefore be too stringent, and a less restrictive approach may ensure that prompt intervention is provided for more elderly patients.

Funding

This work was supported by the Australasian Society of Cardiac and Thoracic Surgeons (ASCTS) National Cardiac Surgery Database Program is funded by the Department of Human Services, Victoria, and the Health Administration Corporation (GMCT) and the Clinical Excellence Commission (CEC), NSW.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The following investigators, data managers and institutions participated in the ASCTS Database: Alfred Hospital: Pick A, Duncan J; Austin Hospital: Seevanayagam S, Shaw M; Cabrini Health: Shardey G; Geelong Hospital: Morteza M, Bright C; Flinders Medical Centre: Knight J, Baker R, Helm J; Jessie McPherson Private Hospital: Smith J, Baxter H; Hospital: John Hunter Hospital: James A, Scaybrook S; Lake Macquarie Hospital: Dennett B, Jacobi M; Liverpool Hospital: French B, Hewitt N; Mater Health Service Hospital: Diqer AM, Archer J; Monash Medical Centre: Smith J, Baxter H; Prince of Wales Hospital: Wolfenden H, Weerasinge D; Royal Melbourne Hospital: Skillington P, Law S; Royal Prince Alfred Hospital: Wilson M, Turner L; St George Hospital: Fermanis G, Redmond C; St Vincent’s Hospital, VIC: Yii M, Newcomb A, Mack J, Duve K; St Vincent’s Hospital, NSW: Spratt P, Hunter T; The Canberra Hospital: Bissaker P, Butler K; Townsville Hospital: Tam R, Farley A; Westmead Hospital: Costa R, Halaka M.

REFERENCES

- 1. Australian Bureau of Statistics. One in four Australians aged 65 years and over by 2056: ABS. Population Projections, Australia, 2006 to 2101, 2008.

- 2.Lung B, Baron G, Butchart EG, Delahaye F, Gohlke-Barwolf C, Levang OW, Tornos P, Vanoverschelde JL, Vermeer F, Boersma E, Ravaud P, Vahanian A. A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe: the Euro Heart Survey on valvular heart disease. European Heart Journal. 2003;24:1231–43. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00201-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association: Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease) Journal of American College of Cardiology. 1998;32:1486–588. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00454-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malaisrie SC, McCarthy PM, McGee EC, Lee R, Rigolin VH, Davidson CJ, Beohar N, Lapin B, Subacius H, Bonow RO. Contemporary perioperative results of isolated aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2010;89:751–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bach DS, Siao D, Girard SE, Duvernoy C, McCallister BDJ, Gualano SK. Evaluation of patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis who do not undergo aortic valve replacement: the potential role of subjectively overestimated operative risk. Circulation Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2009;2:533–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.848259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolh P, Kerzmann A, Honore C, Comte L, Limet R. Aortic valve surgery in octogenarians: predictive factors for operative and long-term results. European Journal of Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2007;31:600–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Likosky DS, Sorensen MJ, Dacey LJ, Baribeau YR, Leavitt BJ, DiScipio AW, Hernandez FJ, Cochran RP, Quinn R, Helm RE, Charlesworth DC, Clough RA, Malenka DJ, Sisto DA, Sardella G, Olmstead EM, Ross CS, O’Connor GT Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group. Long-term survival of the very elderly undergoing aortic valve surgery. Circulation. 2009;120(Suppl. 1):S127–33. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.842641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pellikka PA, Nishimura RA, Bailey KR, Tajik AJ. The natural history of adults with asymptomatic, hemodynamically significant aortic stenosis. Journal of American College of Cardiology. 1990;15:1012–7. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90234-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross J, Braunwald E. Aortic stenosis. Circulation. 1968;38:61–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.38.1s5.v-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aronow WS, Ahn C, Kronzon I, Nanna M. Prognosis of congestive heart failure in patients aged >62 years with unoperated severe valvular aortic stenosis. American Journal of Cardiology. 1993;72:846–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)91081-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsson M, Granstrom L, Lindblom D, Rosenqvist M, Ryden L. Aortic valve replacement in octogenarians with aortic stenosis: a case-control study. Journal of American College of Cardiology. 1992;20:1512–6. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90444-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filsoufi F, Rahmanian PB, Castillo JG, Chikwe J, Silvay G, Adams DH. Excellent early and late outcomes of aortic valve replacement in people aged 80 and older. Journal of American Geriatric Society. 2008;56:255–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boning A, Lutter G, Mrowczynski W, Attmann T, Bodeker RH, Scheibelhut C, Cremer J. Octogenarians undergoing combined aortic valve replacement and myocardial revascularization: perioperative mortality and medium-term survival. Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2010;58:159–63. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1240832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melby SJ, Zierer A, Kaiser SP, Guthrie TJ, Keune JD, Schuessler RB, Pasque MK, Lawton JS, Moazami N, Moon MR, Damiano RJR. Aortic valve replacement in octogenarians: risk factors for early and late mortality. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2007;83:1651–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varadarajan P, Kapoor N, Bansal RC, Pai RG. Survival in elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis is dramatically improved by aortic valve replacement: results from a cohort of 277 patients aged ≥ 80 years. European Journal of Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2006;30:722–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huber CH, Goeber V, Berdat P, Carrel T, Eckstein F. Benefits of cardiac surgery in octogenarians – a postoperative quality of life assessment. European Journal of Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2007;31:1099–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leontyev S, Walther T, Borger MA, Lehmann S, Funkat AK, Rastan A, Kempfert J, Falk V, Mohr FW. Aortic valve replacement in octogenarians: utility of risk stratification with EuroSCORE. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2009;87:1440–5. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalavrouziotis D, Li D, Buth KJ, Legare J-F. The European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE) is not appropriate for withholding surgery in high-risk patients with aortic stenosis: a retrospective cohort study. Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery. 2009;4:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-4-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rankin JS, Hammill BG, Ferguson TBJ, Glower DD, O’Brien SM, DeLong ER, Peterson ED, Edwards FH. Determinants of operative mortality in valvular heart surgery. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2006;131:547–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mistiaen W, Van Cauwelaert P, Muylaert P, Wuyts F, Harrisson F, Bortier H. Risk factors and survival after aortic valve replacement in octogenarians. Journal of Heart Valve Disease. 2004;13:538–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]