Abstract

Background

Age mixing may explain differences in HIV prevalence across populations in sub-Saharan countries, but the validity of survey data on age mixing is unknown.

Methods

Age differences between partners are frequently estimated indirectly, by asking respondents to report their partner’s age. Partner age can also be assessed directly, by tracing partners and asking them to report their own age. We use data from 519 relationships, collected in Likoma (Malawi), in which both partners were interviewed and tested for HIV. In these relationships age differences were assessed both indirectly and directly, and estimates could thus be compared. We calculate the specificity and sensitivity of the indirect method in identifying age-homogenous/age-disparate relationships in which the male partner is less/more than 5 or 10 years older than the respondent.

Results

Women were accurate in identifying age-homogenous relationships, but not in identifying age-disparate relationships (specificity ≈ 90%, sensitivity = 24.3%). The sensitivity of the indirect method was even lower in detecting partners older than the respondent by 10 + years (9.6%). Among 43 relationships with an HIV-infected partner included in this study, there were close to 3 times more age-disparate relationships according to direct measures of partner age than according to women’s reports of their partner’s age (17% vs. 46%).

Conclusions

Survey reports of partner age significantly under-estimate the extent of and the HIV risk associated with age mixing in this population. Future studies of the impact of sexual mixing pattern son HIV risk in sub-Saharan countries should take reporting biases into account.

Women get infected with HIV at an earlier age than men in sub-Saharan countries (1–4). While differences in male-to-female vs. female-to-male probabilities of HIV transmission may explain some of these patterns (5), age differences between male and female sexual partners can also play a key role in explaining gender differences in age at HIV infection (6–8). There are several reasons why having older sexual partners may put young women at a higher risk of HIV infection. First, the prevalence of HIV is likely higher among older partners of young women than among boys of their own age (3, 7). Second, older men are generally less likely to use condoms (9). Finally, women engaged in relationships with older partners may have more limited agency to negotiate safe-sex practices (10), and may even be particularly vulnerable to domestic violence (11–13). Age differences in sexual partnerships may be accompanied by economic asymmetries (10), which further limit women’s agency to adopt safe-sex practices. Age mixing patterns may play a key role in explaining the “uneven spread” of HIV in sub-Saharan populations: Chapman et al (6) recently found that age differences between partners were larger in the most affect southern African populations. Interventions to limit sexual mixing between younger women and older men have thus been proposed and implemented in a growing number of sub-Saharan countries (14, 15).

Despite this programmatic focus, mathematical models indicate that the population-level impact of such interventions could be limited if not accompanied by other behavioral changes (16). The conclusions of these models however build on survey data on partner’s age that have not been validated. Survey respondents are usually asked to report the age of their sexual partners (6–8, 17), but the accuracy of such reports may be limited in situations where partners are not well aware of each other’s age. This may be the casein short-term relationships or in societies where vital registration is limited. Reporting of partner’s age may also be affected by large social desirability biases: in contexts where “sugar daddies” are stigmatized as a key epidemic driver, women may be tempted to under-estimate the age of their partners during sexual behavior interviews; on the other hand, if women associate older partner age with increased resources, some men may be tempted to exaggerate their age to their potential partner(s) when they are trying to initiate a new relationship.

In this paper, we use unique data on 519 sexual relationships(including both marital and non-martial relations), collected on Likoma Island (18), in which both sexual partners were interviewed and reported their own age as well as their partner’s age. We use these data to determine the accuracy of respondents’ reports of partner’s age collected during surveys. We then test whether measurement error may have led to under-estimates of the HIV risk associated with age differences between sexual partners.

1. Data and methods

a. Data collection

The data presented here come from the second round of the Likoma Network Study, a longitudinal study of sexual networks and HIV infection conducted in Malawi. Detailed descriptions of the data collection procedures are available in (18). Briefly, during the second round of data collection, all adults aged 18—49 living in all but 2 of the island’s villages were asked to 1) complete a socioeconomic survey, 2) complete a sexual network survey during which they identified up to 5 of their most recent sexual partners, and 3) participate in HIV testing and counseling. Information on individual characteristics, sexual partnerships and HIV status were then linked to produce images of the sexual networks connecting population members as in (19).

b. Measures of age differences between partners

In the majority of sexual behavior studies conducted in sub-Saharan countries(6, 7, 17, 20, 21), the age difference between a respondent and her partner is measured indirectly by asking the survey respondent to report her partner’s age, or at least estimate the age difference between her and her partner. Specifically, a respondent may be asked to report the age of her partner in completed years or to first classify her partner(s) as younger, of the same age as or older than her. A follow-up question for partners younger or older than the respondent then asks the respondent to specify by how many years the partner is older/younger than the respondent. Sometimes, this follow-up question may provide the respondent with categorical answers to choose from: older/younger by 5 years or less, by 6–10 years, or by 11 years and more.

Age differences between sexual partners can also be established directly in situations where both partners have been interviewed during a survey. Researchers can link respondents’ reports, allowing them to compare the report of a respondent’s own age to the report of a partner’s age made by the partner himself during the survey. The age difference between partners in a sexual relationship is thus equal to the difference between respondent’s age and partner’s age. This direct approach has occasionally been used in surveys in sub-Saharan countries (e.g., the couple sample of the Demographic and Health Surveys), but unfortunately 1) it has only been used among co-residing, often marital, couples, and 2) it has not been used in conjunction with estimates of age differences based on the indirect method. As a result, the accuracy of the indirect method for measuring age differences has not been assessed.

The LNS data permit estimating age differences using both the direct and indirect approaches. Each LNS respondent was asked to classify the age difference between her and her partner using the indirect method. In a subset of the relationships that includes both marital and non-marital relationships, both partners were interviewed by the study team thus also enabling direct measurement of age differences. In this paper, relationships in which the man (partner) is 6 or more years older or more than the woman (respondent) are “age-disparate” (22); relationships in which the man (partner) is 5 years older or less than the woman (respondent) are “age-homogenous”. The choice of this threshold (5 years) is due to the survey instrument used during the LNS to obtain indirect measures of partner’s age: respondents were asked to state whether their older/younger partner was 5 or fewer years, 6–10 years or more than 10 years older/younger than them. In this paper, we assess the accuracy of women’s reports of their partner’s age.

c. Statistical analyses

i. Sample selectivity

The analyses of data validity are thus based on a subset of relationships in which both partners were interviewed and agreed that they were in a relationship (23). We compare the characteristics of relationships in this analytical subset to the rest of the relationships using χ2 tests of association. Not all partners included in these analyses were tested for HIV during the LNS. We also compare the characteristics of those with known and unknown HIV status using the same approach.

ii. Accuracy of self-reports of age differences

We consider direct estimates of age differences as a “gold standard” against which we evaluate the validity of data on partner age obtained indirectly. To determine the accuracy of respondents’ reports of age differences, we assess whether relations identified as age-disparate (or age-homogenous) in this gold standard are also classified as such in the respondents’ indirect reports. The specificity of the indirect method is thus defined as the proportion of all relationships classified as age-homogenous by the direct method that are also reported as such (indirectly) by the respondent. The sensitivity of the indirect method is defined as the proportion of all relationships classified as age-disparate by the direct method that are also reported as such (indirectly) by the respondent. We also assess the accuracy of the indirect method in detecting partners more than 10 years older than the respondent.

iii. Robustness tests

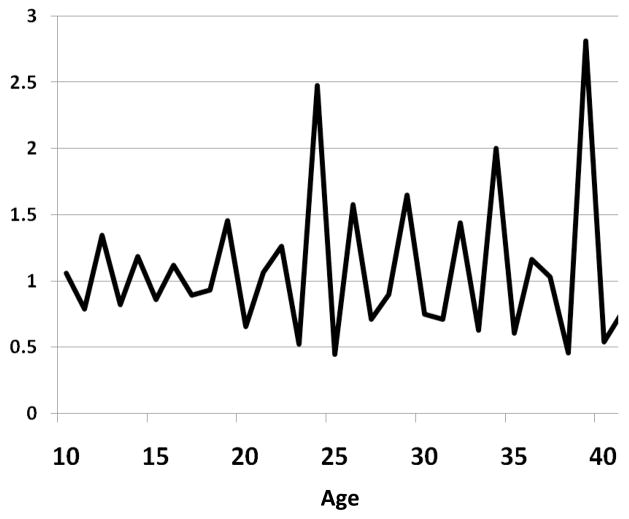

Survey respondents may misclassify some of their relations if the difference between their age and the age of their partner is close to the value of the 5-year threshold (e.g., +/− 2 years). We thus test whether the sensitivity/specificity of the indirect measures of age differences vary with the “true” age difference between partners(classified as within 0–2 years, 3–5 years or more than 5 years from the threshold). Survey respondents may also misreport their own age in demographic surveys, often because of age heaping (24–27). This may significantly confound our validation of the indirect method. In order to test the robustness of our findings to misreporting of a respondent’s own age, we employ two strategies. First, we use data from the first round of the LNS (18) to identify individuals who reported their age consistently in both survey waves, i.e., the age they reported in the second round is one or two years more than its value in the first round. Second, we consider only respondents and partners whose reported age did not end in 0 or 5. Age heaping is indeed significant in the LNS dataset (Figure 1). We then repeat our calculations of the sensitivity and specificity of the indirect method using the subset of relationships in which 1) both partners are consistent reporters, and 2) neither the respondent nor her partner have an age that ends in 0 or 5.

Figure 1.

Age heaping in the Likoma Network Study. The data series represents the ratio of the number of individuals reporting age x to the sum of the number of people reporting age x+1 and age x−1. Values significantly larger than 1 can be observed for ages ending in 0 and 5 (particularly at ages 25, 35 and 40). This is indicative of age heaping.

iv. Age-disparate relationships and HIV risk

Because the LNS is based on a partner tracing design (18), we are able to assess the prevalence of HIV among partners of survey respondents. Among all relationships with an HIV-positive partner, we estimate the frequency of age-disparate vs. age-homogenous relationships according to both the indirect and direct approaches to measuring age differences between partners. We test for systematic differences between the two measures using Fisher’s exact χ2 test of association (two-sided). This comparison provides an indication of the extent of bias in indirect estimates of the relative risk of HIV infection associated with age-disparate relations.

2. Results

a. Descriptive statistics

i. Characteristics of relationships included in analysis

The analysis focuses on 519 relationships reported by both the female and the male partner during the LNS. Table 1 describes the characteristics of these included relationships. Relationships reported by younger respondents were as likely to be included as those reported by older respondents, but relationships of HIV-infected respondents were slightly less likely to be included (33.5% vs 27.8%, p=0.1). Non-marital and dissolved relationships were less likely to be included than ongoing marital relationships. However, the probability of inclusion did not vary according to indirect measurements of the age difference between a respondent and her partner: 33.5%of the age-homogenous relationships and 34.2% of the age-disparate relationships (p=0.83) were thus included in the analysis.

Table 1.

Sample selectivity. In parentheses, we show the % of all relationships in a given category that were included in the analysis. Notes: the p-values are based on χ2 tests of association.

| Relationships included in the analysis (N=519) | p-value | Partners tested for HIV (N=376) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of the respondent | ||||

| < 25 years | 206(31.6) | 0.88 | 153(74.3) | 0.45 |

| ≥ 25 years old | 313(31.3) | 223(71.3) | ||

| HIV status of the respondent | ||||

| Not infected | 390(33.5) | 0.10 | 305(76.3) | 0.45 |

| Infected | 62(27.8) | 47(72.3) | ||

| Relationship type | ||||

| Non-marital | 126(15.3) | <0.01 | 88(69.8) | 0.43 |

| Marital | 392(47.8) | 288(73.5) | ||

| Relationship status | ||||

| Dissolved | 161(16.8) | <0.01 | 254(71.5) | 0.39 |

| Ongoing | 355(51.8) | 121(75.2) | ||

| Self-reported classification of partner’s age | ||||

| 5 or fewer years older | 431(33.5) | 0.83 | 319(73.7) | 0.11 |

| 6 or more years older | 79(34.2) | 52(65.0) |

ii. Characteristics of partners with known HIV status

Only 376 out of 519 partners (72.5%) participated in HIV testing. There were however few differences between tested and non-tested partners. In particular, partners of HIV infected respondents were not significantly more likely to be tested for HIV during the study than partners of HIV negatives. Participation in HIV testing appeared slightly higher among partners less than 5 years or older than the respondents, but this difference was not significant (p=0.11).

iii. Indirect and direct measures of age differences between partners

Six respondents refused to answer the question about the age of their male partner (6/519, 1.1%). Respondents (indirectly) reported that 15.6% (80/513) of the included relationships involved partners older than them by more than 5 years, and 2.5% (13/513) included partners older than them by more than 10 years.

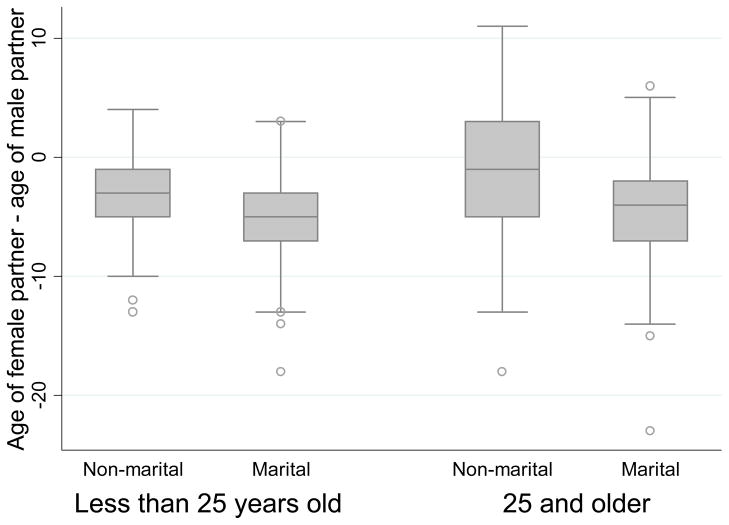

Direct measures of age differences indicate that the median age difference between a woman and her partner was 4 years (Figure 2). Figure 2 shows how the distribution of directly measured age differences varied by age of the respondent and marital status of the relationship. The median age difference was significantly smaller in non-marital relationships than in marriages. Among women more than 25 years old, the median age difference with non-marital partners was 1 year, whereas it was 5 years with spouses (p < 0.01). Among women less than 25 years, non-marital partners were on average 3 years older than them, whereas spouses were on average 5 years older (p < 0.01). More than 40% of the non-marital partners of women aged more than 25 were actually with partners younger than them.

Figure 2.

Age differences between partners, direct estimates

b. Accuracy of indirect measures of age differences in sexual relationships

Respondents were accurate in identifying age-homogenous relationships, but not in identifying age-disparate relationships. The specificity of the indirect measure of age differences was 89.1% (95% CI = 85.1—92.1, see table 2), but its sensitivity was 24.3% (95% CI = 18.2 – 31.3). Furthermore, younger respondents were significantly less accurate than older respondents in identifying age-disparate relations. Respondents less than 25 years old correctly classified only 8 out of 57 (14.0%) of their age-disparate relationships vs. 35 out 120 (29.2%) among respondents aged 25 and older.

Table 2.

Accuracy of respondents’ reports of their partner’s age. Notes: Specificity = # of relations reported as age homogenous by the respondent/# of true age homogenous relationships; Sensitivity = # of relations reported as age disparate by the respondent/(# true number of age disparate relations.

| Partner classified as more than 5 years older | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All relations | Consistent age reporters | Age heaping | ||||

| Estimate (n/N) | 95% CI | Estimate (n/N) | 95% CI | Estimate (n/N) | 95% CI | |

| Specificity | ||||||

| All relations | 89.0(299/336) | 85.1–92.1 | 91.3(105/115) | 84.6–95.7 | 89.0(194/218) | 84.1–92.8 |

| Respondent < 25 years old | 89.7(131/146) | 83.6–94.1 | 88.9(48/54) | 77.4–95.8 | 90.8(99/109) | 83.8–95.5 |

| Respondent ≥ 25 years old | 88.4(168/190) | 83.0–92.6 | 93.4(57/61) | 84.0–98.2 | 87.2(95/109) | 79.4–92.8 |

| Sensitivity | ||||||

| All relations | 24.3(43/177) | 18.2–31.3 | 16.1(5/31) | 5.5–33.7 | 22.1(23/104) | 14.6–31.3 |

| Respondent < 25 years old | 14.0(8/57) | 6.3–25.8 | --a | --a | 10.8(4/37) | 3.0–25.4 |

| Respondent ≥ 25 years old | 29.2(35/120) | 21.2–38.2 | --a | --a | 28.4(19/67) | 18.0–40.7 |

| Partner classified as more than 10 years older | ||||||

| Specificity | ||||||

| All relations | 98.3(453/461) | 96.6–99.2 | 98.6(140/142) | 95.0–99.8 | 99.0(284/287) | 97.0–99.8 |

| Sensitivity | ||||||

| All relations | 9.6(5/52) | 3.2–21.0 | --a | --a | 8.6(3/35) | 1.9–23.0 |

The number of cases available for analysis was less than 20 and these cells were thus excluded from the analyses

The specificity of indirect reports increased when we sought to identify partners who are more than 10 years older than the respondent. The sensitivity of these reports, on the other hand, deteriorated further. Only 5 out of 52 (9.7%) age-disparate relationships identified as such by the direct method were also correctly classified by the indirect method. In robustness tests, the sensitivity and specificity of indirect measures were similar in analyses based on the subset of relationships between consistent respondents, or on the subset of relationships without age heaping.

c. Are misclassifications due to the thresholds imposed on respondents’ reports of partner age?

We found that respondents’ accuracy in classifying age-homogenous relations did not vary with the age difference between partners (table 3). On the other hand, their ability to correctly identify age-disparate relations increased sharply with the age difference between partners. Respondents were more likely to misclassify relations with partners 6–7 years older than they were to misclassify relations with partners more than 7 years older than them (p=0.05). The sensitivity of the indirect method was highest among relations with partners more than 10 years older than the respondent. Even in such relationships however, only one third of all age-disparate relationships were correctly classified as such by the respondent.

Table 3.

Accuracy of respondents’ reports of their partner’s age, by “true” age difference between a respondent and her partner. Notes: the p-values are based on χ2 tests of association

| Specificity | Sensitivity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age difference between partners | Estimate (n/N) | p-value | Estimate (n/N) | p-value |

| 0–2 years of the 5-year threshold | 88.2(142/161) | 0.82 | 15.7(11/70) | 0.05 |

| 3–5 years of the 5-year threshold | 90.3(121/134) | 25.5(14/55) | ||

| More than 5 years from the 5-year threshold | 87.8(36/41) | 34.6(18/52) | ||

d. Misclassifications and HIV risk in age-disparate relationships

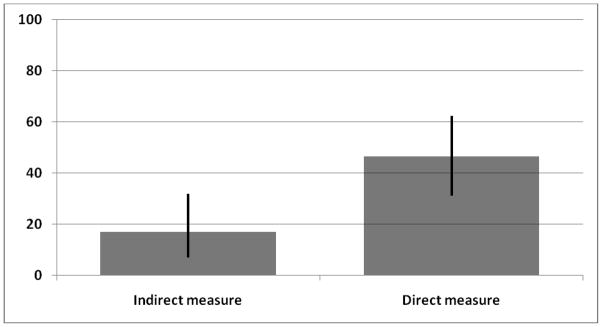

There were 43 relations between respondents and an HIV-infected male partner. According to indirect measures of age differences between partners, only 7 of these relations were age-disparate (Figure 4, 16.3%). According to direct measures however, this proportion was much higher since 20 of these relations were age-disparate (46.5%, p < 0.01).

3. Discussion

The analyses presented here indicate that the accuracy of indirect estimates of age differences between partners – on which most assessments of the epidemiological importance of age mixing for HIV spread are based – is limited. We used a study design allowing comparison of indirect measures of age differences between partners with direct measures relying on partners’ reports of their own age. We showed that women on Likoma engage in more age-disparate relationships than they reported during the survey. As a result, respondents’ reports of their partners’ ages lead to under-estimating the impact of age-disparate relationships on HIV infection risks. Whereas it initially appeared that only 1 in 6 relationships between a woman and an HIV-infected male partner was age-disparate (according to women’s report of age differences between partners), direct measures of partner age indicated that this proportion was actually closer to 1 in 2. We found that younger women were even less accurate than older respondents in identifying age-disparate relationships. Patterns of age mixing could thus play an even greater role than previously thought (7) in explaining the disproportionate HIV burden among female youth in similar populations (3).

These analyses suffer from several limitations however. First, they are only based on a selective sub-sample of the relationships reported during the study. We are not able to assess the validity of the reports of age differences in relationships where the male partner was not interviewed or tested for HIV during the study. Second, our indirect measure of the age difference between partners was based on broad categories rather than on continuous measures of partner’s age. As a result it prevents a more detailed assessment of the correlation between respondent’s reports of their partner’s age and the actual age of the partner. It also forced us to adopt an arbitrary definition of age-disparate versus age-homogenous mixing. Rather than focusing on broad classifications of age differences between partners, future studies should seek to measure the accuracy of reports of exact partner age. Third, our gold standard (partner’s reports of their own age) is admittedly imperfect. In the absence of systematic birth registration, individuals may not even accurately report their own age. We showed however that the specificity and sensitivity of the indirect method were similar in relationships between consistent age reporters as well as in the subset of relationships without age heaping. But unfortunately, we have no means of independently confirming a respondent’s own age. Future assessments of indirect measures of age differences in sexual partnerships could be conducted in demographic surveillance sites (28), where the quality of data on age is potentially higher.

Despite these caveats, our research on the reporting of partner age in surveys of sexual behaviors conducted in sub-Saharan populations has important implications. First, it suggests that the preventive benefits associated with effective behavioral change communications aiming to reduce age differences between partners may have been under-estimated. If age-disparate relations are more common and account for a larger proportion of all the relationships through which women are possibly exposed to HIV, the epidemiological benefits of preventing age-disparate sexual mixing could be larger than initially thought. This should be re-assessed in mathematical models that account for possible measurement error. Second, it indicates that future research on the impact of age mixing (and other sexual mixing patterns)on HIV transmission should be based on rigorous study designs that allow more objective measurements of mixing patterns than current measurements based solely on reports by survey respondents. Taking respondents’ reports at face value leads to erroneous inferences about the relative contribution of various risk factors to HIV spread (29). It could thus contribute to misguided policies and interventions, or to lack of support for promising interventions.

Figure 3.

Proportion of HIV-infected partners who are more than 5 years older than the respondent, by method for measurement of age differences between partners (N = 43). The thicker vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals. The difference between the indirect and direct measures was significant at the .01 significance level using Fisher’s exact test (two-sided).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support for this research through NIH grants RO1 HD044228, RO1 HD/MH41713 and R01HD053781, and funding through two PARC/Boettner/PSC Pilot Grants by the Population Aging Center(P30-AG-012836) and the Population Studies Center (R24-HD-044964), University of Pennsylvania.

Footnotes

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Stéphane Helleringer, Email: sh2813@columbia.edu.

Hans-Peter Kohler, Email: hpkohler@pop.upenn.edu.

James Mkandawire, Email: jnrnurse@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Pettifor AE, Rees HV, Kleinschmidt I, et al. Young people’s sexual health in South Africa: HIV prevalence and sexual behaviors from a nationally representative household survey. AIDS. 2005 Sep 23;19(14):1525–34. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000183129.16830.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heuveline P. HIV and population dynamics: a general model and maximum-likelihood standards for east Africa. Demography. 2003 May;40(2):217–45. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glynn JR, Carael M, Auvert B, et al. Why do young women have a much higher prevalence of HIV than young men? A study in Kisumu, Kenya and Ndola, Zambia. AIDS. 2001 Aug;15( Suppl 4):S51–60. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taha TE, Dallabetta GA, Hoover DR, et al. Trends of HIV-1 and sexually transmitted diseases among pregnant and postpartum women in urban Malawi. AIDS. 1998 Jan 22;12(2):197–203. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199802000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray RH, Wawer MJ, Brookmeyer R, et al. Probability of HIV-1 transmission per coital act in monogamous, heterosexual, HIV-1-discordant couples in Rakai, Uganda. Lancet. 2001 Apr 14;357(9263):1149–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapman R, White RG, Shafer LA, et al. Do behavioural differences help to explain variations in HIV prevalence in adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa? Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2010 May;15(5):554–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregson S, Nyamukapa CA, Garnett GP, et al. Sexual mixing patterns and sex-differentials in teenage exposure to HIV infection in rural Zimbabwe. Lancet. 2002 Jun 1;359(9321):1896–903. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08780-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelly RJ, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, et al. Age differences in sexual partners and risk of HIV-1 infection in rural Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003 Apr 1;32(4):446–51. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200304010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luke N. Confronting the ‘sugar daddy’ stereotype: age and economic asymmetries and risky sexual behavior in urban Kenya. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2005 Mar;31(1):6–14. doi: 10.1363/3100605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luke N. Age and economic asymmetries in the sexual relationships of adolescent girls in sub-Saharan Africa. Stud Fam Plann. 2003 Jun;34(2):67–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2003.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Nduna M, et al. Factors associated with HIV sero-status in young rural South African women: connections between intimate partner violence and HIV. Int J Epidemiol. 2006 Dec;35(6):1461–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jewkes R, Levin J, Penn-Kekana L. Risk factors for domestic violence: findings from a South African cross-sectional study. Soc Sci Med. 2002 Nov;55(9):1603–17. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jewkes RK, Levin JB, Penn-Kekana LA. Gender inequalities, intimate partner violence and HIV preventive practices: findings of a South African cross-sectional study. Soc Sci Med. 2003 Jan;56(1):125–34. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.PSI--Cross-generational sex. 2010 [cited 2010 August 5th]; Available from: http://www.psi.org/our-work/healthy-lives/interventions/cross-generational-sex.

- 15.Clark S, Bruce J, Dude A. Protecting young women from HIV/AIDS: the case against child and adolescent marriage. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2006 Jun;32(2):79–88. doi: 10.1363/3207906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hallett TB, Gregson S, Lewis JJ, Lopman BA, Garnett GP. Behaviour change in generalised HIV epidemics: impact of reducing cross-generational sex and delaying age at sexual debut. Sex Transm Infect. 2007 Aug;83( Suppl 1):i50–4. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.023606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrison A, Cleland J, Frohlich J. Young people’s sexual partnerships in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: patterns, contextual influences, and HIV risk. Stud Fam Plann. 2008 Dec;39(4):295–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00176.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helleringer S, Kohler HP, Chimbiri A, Chatonda P, Mkandawire J. The Likoma Network Study: Context, data collection, and initial results. Demogr Res. 2009;21:427–68. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2009.21.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helleringer S, Kohler HP. Sexual network structure and the spread of HIV in Africa: evidence from Likoma Island, Malawi. AIDS. 2007 Nov 12;21(17):2323–32. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328285df98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ott MQ, Barnighausen T, Tanser F, Lurie MN, Newell ML. Age-gaps in sexual partnerships: seeing beyond ‘sugar daddies’. AIDS. 2011 Mar 27;25(6):861–3. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834344c9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katz I, Low-Beer D. Why has HIV stabilized in South Africa, yet not declined further? Age and sexual behavior patterns among youth. Sex Transm Dis. 2008 Oct;35(10):837–42. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31817c0be5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leclerc-Madlala S. Age-disparate and intergenerational sex in southern Africa: the dynamics of hypervulnerability. AIDS. 2008 Dec;22( Suppl 4):S17–25. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000341774.86500.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helleringer S, Kohler HP, Kalilani-Phiri L, Mkandawire J, Armbruster B. The reliability of sexual partnership histories: implications for the measurement of partnership concurrency during surveys. AIDS. 2011 Dec 6; doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283434485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zelnik M. Age heaping in the United States census: 1880–1950. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1961 Jul;39:540–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stockwell EG, Wicks JW. Age heaping in recent national censuses. Soc Biol. 1974 Summer;21(2):163–7. doi: 10.1080/19485565.1974.9988102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feeney G. A technique for correcting age distributions for heaping on multiples of five. Asian Pac Cens Forum. 1979;5(3):12–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heitjan DF, Rubin DB. Inference from Coarse Data Via Multiple Imputation with Application to Age Heaping. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1990 Jun;85(410):304–14. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanser F, Hosegood V, Barnighausen T, et al. Cohort Profile: Africa Centre Demographic Information System (ACDIS) and population-based HIV survey. Int J Epidemiol. 2008 Oct;37(5):956–62. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Minnis AM, Steiner MJ, Gallo MF, et al. Biomarker validation of reports of recent sexual activity: results of a randomized controlled study in Zimbabwe. Am J Epidemiol. 2009 Oct 1;170(7):918–24. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]