Abstract

The distribution of fitness effects (DFE) of new mutations is of fundamental importance in evolutionary genetics. Recently, methods have been developed for inferring the DFE that use information from the allele frequency distributions of putatively neutral and selected nucleotide polymorphic variants in a population sample. Here, we extend an existing maximum-likelihood method that estimates the DFE under the assumption that mutational effects are unconditionally deleterious, by including a fraction of positively selected mutations. We allow one or more classes of positive selection coefficients in the model and estimate both the fraction of mutations that are advantageous and the strength of selection acting on them. We show by simulations that the method is capable of recovering the parameters of the DFE under a range of conditions. We apply the method to two data sets on multiple protein-coding genes from African populations of Drosophila melanogaster. We use a probabilistic reconstruction of the ancestral states of the polymorphic sites to distinguish between derived and ancestral states at polymorphic nucleotide sites. In both data sets, we see a significant improvement in the fit when a category of positively selected amino acid mutations is included, but no further improvement if additional categories are added. We estimate that between 1% and 2% of new nonsynonymous mutations in D. melanogaster are positively selected, with a scaled selection coefficient representing the product of the effective population size, Ne, and the strength of selection on heterozygous carriers of ∼2.5.

THE increasing availability of large, genome-wide data sets on DNA sequence variability within populations has stimulated the development of statistical population genetic methods for fitting models of the evolutionary forces affecting sequence evolution and variability and estimating the parameters of the models, especially the strength of positive and purifying selection (reviewed by Eyre-Walker and Keightley 2007; Wright and Andolfatto 2008; Sella et al. 2009; Charlesworth 2011). These methods have been applied to both noncoding and coding sequences and within coding sequences to selection on codon usage at synonymous sites (Bulmer 1991; Akashi 1995; Zeng and Charlesworth 2009; Sharp et al. 2010) and nonsynonymous sites (Sawyer et al. 1987; Bustamante et al. 2002; Piganeau and Eyre-Walker 2003; Eyre-Walker et al. 2006; Loewe et al. 2006; Keightley and Eyre-Walker 2007; Boyko et al. 2008).

There is general agreement that nonsynonymous mutations are usually subject to the strongest selection pressures relative to other types of single-nucleotide mutation, and much attention has been given to the following two questions, which can in principle be answered by large-scale studies of within-species variation and between-species divergence. What is the nature of the distribution of selection coefficients against newly arising nonsynonymous mutations that have deleterious effects on fitness? What is the fraction (α) of nonsynonymous differences between two related species that have been driven to fixation by positive selection, as opposed to neutral or slightly deleterious mutations that were fixed by random genetic drift? While these questions are far from being completely answered, evidence from a variety of organisms and methods suggests that there is a wide distribution of selection coefficients against nonsynonymous mutations, with the bulk of variants found segregating in populations being only weakly deleterious (Sawyer et al. 1987; Bustamante et al. 2002; Piganeau and Eyre-Walker 2003; Eyre-Walker et al. 2006; Loewe et al. 2006; Keightley and Eyre-Walker 2007; Boyko et al. 2008; Haddrill et al. 2010). In several species of Drosophila, mice, bacteria, and some plants, there is evidence that α is of the order of 50%, whereas in hominids and some plants it is apparently much lower (Smith and Eyre-Walker 2002; Charlesworth and Eyre-Walker 2006; Welch 2006; Andolfatto 2007; Shapiro et al. 2007; Bachtrog 2008; Boyko et al. 2008; Eyre-Walker and Keightley 2009; Strasburg et al. 2009, 2011; Gossmann et al. 2010; Halligan et al. 2010; Haddrill et al. 2010; Ingvarsson 2010; Jensen and Bachtrog 2010; Slotte et al. 2010).

The rate of fixation of advantageous nonsynonymous mutations is proportional to the product of the proportion of new nonsynonymous mutations that are selectively advantageous (pa) and their rate of fixation once they arise in the population, assuming that the rate of adaptive evolution is limited by the supply of new mutations (Ohta and Kimura 1971). If the population size is large, the rate of fixation of new nonsynonymous mutations in a randomly mating population is proportional to the product of the effective population size, Ne, and their mean selective advantage in the heterozygous state, sa/2 (Ohta and Kimura 1971). For a given rate of fixation of neutral or slightly deleterious nonsynonymous mutations, α is thus controlled by the product paNesa. In several recent analyses pa and Nesa have been estimated separately by several different methods, using polymorphism and divergence data sets from Drosophila. Very disparate estimates have been obtained by these methods, ranging from a very low frequency of adaptively favorable mutations with relatively strong selective advantages (Eyre-Walker 2006; Li and Stephan 2006; Macpherson et al. 2007; Jensen et al. 2008; Jensen 2009) to a relatively high frequency with a very small mean selective advantage (Sawyer et al. 2003; Andolfatto 2007) and a mixture of strongly and weakly selected advantageous mutations (Sattath et al. 2011).

In this article, we develop a new method for dealing with this problem, in which we extend the maximum-likelihood estimation procedure of Keightley and Eyre-Walker (2007) and Eyre-Walker and Keightley (2009) for estimating the distribution of deleterious selection coefficients and α. The extended method allows the inclusion of contributions from advantageous mutations to nonsynonymous diversity, which permits pa and Nesa to be estimated simultaneously with the other parameters. A similar method was developed by Boyko et al. (2008), but they did not explore the performance of their method in any depth. However, they did note that it was very difficult to disentangle the rate and strength of advantageous mutation when applied to data from hominids. We apply our method to the data sets of Shapiro et al. (2007) and Callahan et al. (2011) on within-species variability and between-species divergence for protein-coding genes in Drosophila melanogaster and find evidence that pa is of the order of 1.5% and Nesa ∼ 5.

Our new method requires assignment of the allele corresponding to the ancestral state at each site. Using parsimony, the ancestral state would correspond to the allele found in the closest outgroup species, in this case D. simulans. However, this does not take into account the possibility of a substitution in the D. simulans lineage, nor does it consider rate variation among sites (where some sites are more constrained than others). Thus, a probabilistic approach using two different outgroups was used, in which the first step is to estimate the properties of the substitution process (the substitution rate matrix and the degree of rate variation) as well as the distances between the three species. The second step is to estimate the probability distribution for each ancestral nucleotide at each site under a probabilistic substitution model. This takes into account potential substitutions in any of the outgroups, which depend on the evolutionary distances between the species. The influence of the more distant outgroup (here D. yakuba) is smaller than that of the closer outgroup (D. simulans), but it is a strong indicator of a site being either more constrained (if the states of the two outgroups coincide) or more variable (if the outgroup states disagree).

Materials and Methods

Data

We analyzed two sets of D. melanogaster polymorphism data. The African subset of the D. melanogaster protein-coding gene sequences described by Shapiro et al. (2007) was kindly provided by Joshua Shapiro and consists of 15 D. melanogaster alleles (11 originating from Zimbabwe and 2 each originating from Botswana and Zambia) along with 1 outgroup allele from D. simulans.

The sequences of an additional outgroup, D. yakuba, were obtained through the UCSC Genome Browser (Kent et al. 2002) by aligning the D. melanogaster “base sequences” to the reference genome (version dm3) and then using the pairwise genome alignment (version vsDroYak2) to map each nucleotide to the orthologous nucleotide in D. yakuba. Of the 397 protein-coding loci, 5 had to be discarded due to ambiguous mapping to the reference genome. The remaining 392 loci were analyzed and yielded 181,415 zerofold sites that were used as nonsynonymous sites and 42,113 fourfold sites that were used as synonymous sites. A second data set, described by Callahan et al. (2011), was kindly provided by Peter Andolfatto and consists of 24 D. melanogaster alleles originating from Zimbabwe, along with D. simulans and D. yakuba outgroup alleles. The 213 protein-coding loci provide a total of 80,809 nonsynonymous (zerofold) and 19,574 synonymous (fourfold) sites. In the case of Shapiro et al. (2007), the maximum-likelihood (ML) analysis was simultaneously applied to sites where all 15 alleles were present and to sites with up to 5 missing alleles. For the Callahan et al. (2011) data set, we allowed up to 8 missing alleles from the 24 sequenced. Sites with >2 segregating alleles were excluded from the analysis.

Model

We assume that all nucleotide sites are in linkage equilibrium and that up to two variants can segregate at a site. We assume that there is a class of sites at which mutations are exclusively neutral (“neutral sites”) and a class of sites at which both advantageous and deleterious mutations can occur (“selected sites”). We assume that there are na classes of advantageous mutations. We assume intermediate dominance and independence among sites. The fitness effect of class i (i = 1 … na ) is which is the difference in fitness between the wild-type and mutant homozygotes. Fitness effects of deleterious mutations are assumed to be gamma distributed, f(sd), with scale and shape parameters a and b, respectively, and sd is the fitness difference between the wild-type and mutant homozygotes. The fraction of advantageous mutations is , and a fraction 1 – pa of mutations are deleterious.

Obtaining the unfolded site frequency spectrum

The unfolded distribution of the number of copies of the derived allele in a sample of nT alleles from a population (the unfolded site frequency spectrum, SFS) is a vector p(). Let p(sel) and p(neut) denote the vectors for selected and neutral sites, respectively. If we are dealing with simulated data, the ancestral allele is known, and thus the number of derived alleles can be determined directly. However, with real sequence data from extant species the ancestral state is unknown. If we have a close outgroup species and assume parsimony, the ancestral allele corresponds to the outgroup allele in most cases. However, substitutions between the ingroup and outgroup species, followed by mutations that cause polymorphism, can lead to a misinterpretation of low-frequency alleles as high-frequency alleles or vice versa. This can be corrected by computing the probabilities for the possible ancestral states. We therefore require a model for the substitution process between the outgroup and the ancestral sequence of the focal species, which can then be used to estimate a corrected SFS.

Estimating the substitution parameters

The substitution process between the three species (D. melanogaster, D. simulans, and D. yakuba) is modeled as a Markov process under the general time-reversible (GTR) model (Tavaré 1986), assuming rate variation among sites with a proportion of invariant sites and NR equally probable categories of rates whose means, ri, follow a gamma distribution (Yang 1994). The substitution parameters were estimated separately for synonymous and nonsynonymous sites for each data set. All sites of a given type within a data set were concatenated to one large alignment and then analyzed using Phyml (Guindon et al. 2010) under the GTR model. In addition to the substitution rate matrix and the branch lengths leading to the three species, the proportion of invariant sites and the shape parameter a of the gamma distribution of the site rates were also estimated (we use a to denote the shape parameters to avoid confusion with α, which is introduced below as the fraction of adaptive substitutions).

Probabilistic computation of the unfolded site frequency spectrum

For each site with a pair of segregating alleles in D. melanogaster (with states x and y), the probability distribution of the ancestral state A depends on the corresponding states os and oy of the outgroups (of D. simulans and D. yakuba, respectively) and on the substitution process θ (which describes the substitution rate matrix Q, the branch lengths tmel, tsim, and tyak leading to the three species, and the shape parameter a). Given these parameters, the likelihood of the ancestral state being x is defined as follows:

| (1) |

The first term on the right-hand side, L(T), is the likelihood of the tree T relating the three characters x, os, and oy, while the second term, Pr(S = {x, y}), is the probability that the ancestral state x generated the two observed alleles x and y, which depends on the substitution rates Q and is given by Hernandez et al. (2007):

| (2) |

Under a model of rate variation among sites with NR discrete rate categories of equal probability with mean rates ri, the likelihood of a tree relating the characters x, os, and oy is defined (Yang 1994) as

| (3) |

Finally, for a given rate r, the likelihood of a tree relating three species is obtained by summing over the possible states Y of the unknown internal node,

| (4) |

with L(a → b|t, Q) being the likelihood of character a being substituted by b after time t under a Markov model defined by rate matrix Q. This corresponds to the index (a, b) of the probability matrix P(t), given by (Cox and Miller 1977).

Considering only the possibilities of A being either in state x or in state y, the probabilities of the two possible ancestral states are obtained by normalizing the likelihoods:

| (5) |

The SFS is then calculated such that for each site with m alleles of type x and nT − m alleles of type y, the corresponding allele frequency p()m is increased by Pr{A = x} and is increased by Pr{A = y}.

Calculation of the population allele frequency distribution

We used the methods described by Keightley and Eyre-Walker (2007) to compute the expected distribution of the frequency of a new mutant allele subject to selection in a finite diploid population, while incorporating a step change from an equilibrium population of size N1 to a population of size N2 at a time t generations in the past, under the assumption of unidirectional mutation. This involves calculating the frequency distribution of segregating sites for an equilibrium model, assuming a population of size N1, and then applying transition matrix iteration for t generations in a population of size N2 to calculate the net numbers of segregating sites that are at different frequencies, conditioned on a mutation having occurred at each site (from ancestral to derived) at each possible generation in the past. In evaluating the likelihood of the data, we fix N1 at 100 and estimate N2 and t as parameters of the model. We have shown previously that this simple two-epoch demographic model allows the recovery of the parameters of the distribution of fitness effects (DFE) with little bias, even if the true demographic scenario is substantially more complex (Keightley and Eyre-Walker 2007; Eyre-Walker and Keightley 2009). The vector v′(s) contains the relative numbers of new mutations segregating at frequencies between 1/(2N2) and (2N2 – 1)/(2N2) for a selection coefficient s, at the time of sampling from the population. Let the sum of these relative numbers be

| (6) |

We define the frequencies at which neutrally evolving sites (s = 0) are in the ancestral and derived states at the time of sampling as f0 and f2N, respectively, which are estimated as parameters of the model. In our previous analysis (Keightley and Eyre-Walker 2007), the parameter f2N was not included, since ancestral and fixed alleles were not distinguished from one another.

The likelihood function uses an allele frequency probability vector for neutral sites, v(0), which has elements as follows:

| (7) |

For the class of sites that are subject to selection, we use transition matrix methods to calculate , the vector of expected numbers of new mutations segregating at frequencies from 1/(2N2) to (2N2 – 1)/(2N2), by integrating over the distribution of deleterious mutational effects, f(sd), and including advantageous mutations with na classes of selective effects weighting the overall contributions of advantageous and deleterious mutations by pa and 1 – pa, respectively. This vector is used to calculate a probability vector of frequencies of segregating and fixed mutations, v(s), which is used in the likelihood calculations. Elements of the vector of numbers of segregating selected mutations (elements 1 . . . 2N2 –1) are scaled in an identical manner to those for neutral mutations, to satisfy the requirement that Σv′(0)i/Σv′(s)i = Σv(0)i/Σv(s)i. For segregating selected mutations, the elements of v(s) are therefore scaled by the conditional number of neutral segregating mutations:

| (8) |

Let u(Na, s)/u(Na, 0) be the ratio of the fixation probability for a selected mutation of fitness effect s to the fixation probability for a neutral mutation, in a population of effective and census size Na (Fisher 1930). Then multiplying this by f2N gives the fraction of sites with selection coefficient s that have become fixed for the derived allele over the whole time since the split from the ancestral species. The expected frequency of selected sites that are fixed for the derived allele, averaged over the contributions of mutations with different selection coefficients (including all classes of advantageous mutations and deleterious mutations), is therefore

| (9) |

where the overbar indicates the mean over the distribution of s. Under the assumption that neutral and selected-site divergence is dominated by fixations that occurred prior to any recent change in population size (the signature of which manifests itself in a departure of the neutral site SFS from its neutral expectation), it is appropriate to assume that Na is the ancestral population size, N1, in Equation 9. However, if there has been a change in population size many generations ago (i.e., t ≫ N2), the SFS may contain essentially no information from which to estimate N1s. We therefore apply an approximation, such that Na is a weighted average of N1 and N2, as described by Eyre-Walker and Keightley (2009, Equation 1). If the population size change was very recent, then Na → N1; if the size change was ancient, then Na → N2.

Finally, the frequency of ancestral selected alleles is

| (10) |

and includes the frequency of sites that never experienced a new mutation and negatively selected mutations that became eliminated from the population.

Parameter inference by ML

The function for the likelihood of the site frequency spectra data was similar to that described by Keightley and Eyre-Walker (2007), with some simplifications. Let p(sel) and p(neut) be SFS vectors for selected and neutral sites, respectively, whose elements are the numbers of sites having a number of derived alleles from 0 to nT, where nT is the number of alleles in the sample. We assume that the observed SFSs are binomial samples from the allele frequency distributions v(s). We calculate v(s) and v(0) as functions of the model parameters (i.e., for a single class of advantageous mutations: a, b, N2, t, f0, f2N). For the selected sites, the log likelihood is

| (11) |

where b(i|nT, q) is the binomial probability of observing i derived alleles in a sample of nT alleles, if the expected derived allele frequency is q. Note that the summations in Equation 11 are to nT and 2N2 rather than to nT – 1 and 2N2 – 1, respectively, as in Keightley and Eyre-Walker (2007), because in that article we did not distinguish between sites fixed for ancestral and derived alleles, as is the case here. For neutral sites, the log likelihood (log Lneut) was calculated using Equation 11, replacing p(sel) with p(neut) and v(s) with v(0). The overall log likelihood was log Lsel + log Lneut. Log likelihood was maximized using the simplex algorithm (Nelder and Mead 1965; Press et al. 1992), as described in Keightley and Eyre-Walker (2007), and convergence was checked by starting the simplex multiple times with random starting values.

The fraction of substitutions driven to fixation by adaptive evolution (α) can be estimated from the relation

| (12) |

Similarly, the rate of adaptive substitution scaled by the rate of neutral substitution is

| (13) |

Simulations

To assess the accuracy of estimation of pa and sa and potential bias, we analyzed simulated data sets generated by sampling from expected gene frequency vectors computed by the transition matrix method (see Keightley and Eyre-Walker 2007 for details). Various data sets of 15 alleles (the number of alleles available in the smaller of the two D. melanogaster data sets that we subsequently analyze) were simulated with between 1250 and 50,000 synonymous and nonsynonymous bases that are subject to mutation during the simulation process. We simulated a single class of advantageous mutational effects, with different combinations of values for pa and sa, together with a gamma distribution of negative fitness effects with shape parameter b = 0.5, a mean fitness effect for deleterious mutations E(sd) = −0.1, and a constant population size of N = 100. The ML estimation procedure was then used to estimate the parameters as described above. The simulated parameter values were used to initialize the procedure to minimize the estimation time and to avoid converging to incorrect local minima. For each data set with these combinations of number of sites, sa and pa, 1000 simulation replicates were performed. We found that the distribution of parameter estimates is highly skewed, so we present the median and the 25% and 75% quantiles to describe the distribution of estimates.

To investigate the effects of linkage on parameter estimation, another set of simulations was performed using the SFS_code software (Hernandez 2008). For each run, 1.2 × 107 nucleotide sites were simulated, divided into unlinked loci of 30, 300, 3000, or 30,000 nucleotides within which linkage was complete. The simulations were performed using 100 ancestral individuals with a speciation event immediately after a burn-in phase, resulting in two populations of 100 individuals, which each evolved independently for 4000 generations. For each combination of parameter values, 100 runs of the simulation for each of the four locus lengths were performed.

Results

Simulations with unlinked loci

Simulations were performed to investigate the conditions under which the parameters modeling positively selected mutations can be estimated with confidence and when there is likely to be bias. In the model presented here, adaptive mutations are described by two parameters, the fraction of a single class of positively selected mutations, pa, and their selection strength, sa.

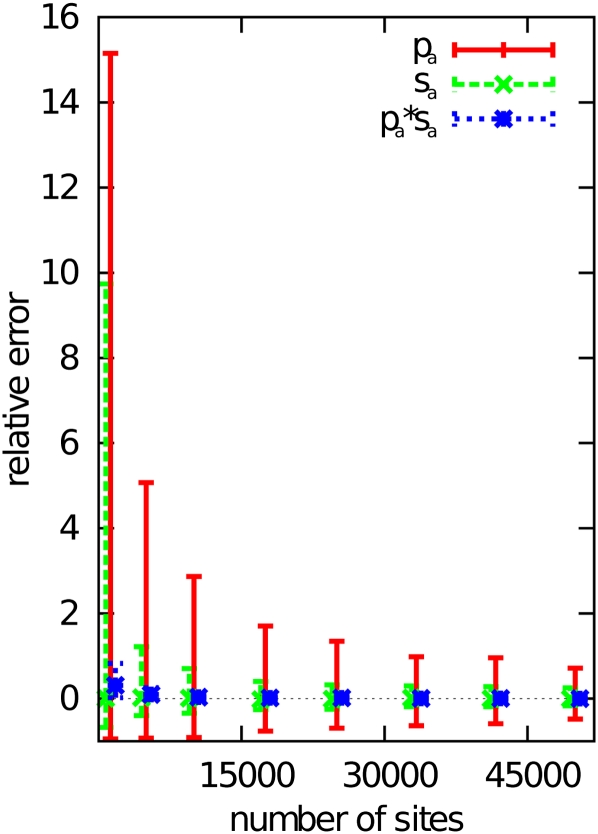

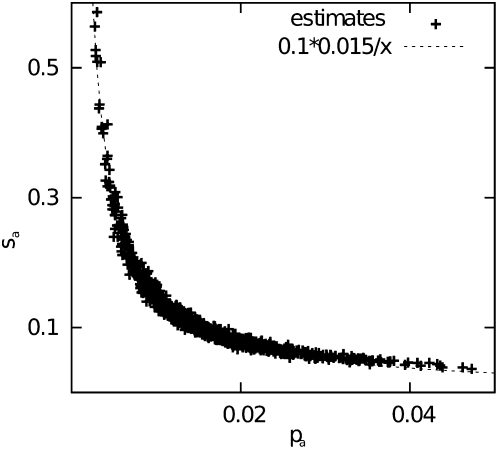

Figure 1 shows the estimation accuracy of these parameters as a function of the number of sites subject to mutation, for simulated values of pa = 0.015 and sa = 0.1 (giving Nsa = 10), which are similar to the values estimated from the analysis of D. melanogaster data sets (see below). The plot suggests that the median of the estimates for both parameters can be estimated accurately, even for small numbers of sites. However, if the number of sites is small (<10,000 sites), the variances of the estimates become very high, and a single estimate can be an over- or underestimate by a factor of ≥10. For larger numbers of sites, however (≥25,000 nucleotides), the variance of the estimates becomes much smaller and allows for estimation of the parameters with high confidence. Remarkably, it appears that the product of the two parameters can be estimated accurately and with low variance, even when only a small number of sites is available. This is illustrated in Figure 2, which shows the correspondence between the estimated values of pa and sa. Each point corresponds to the estimates obtained from one run of the simulation with 25,000 sites. It can be seen that most points are very close to the L-shaped curve, which would be expected if the product of the two parameters was constant at 0.015 × 0.1. The parameters of the gamma distribution of negatively selected mutations [i.e., the shape parameter b and the mean effect E(s)] are estimated with high precision: for ≥10,000 sites simulated, mean estimates are at most 1% different from expectation, and even for as few as 2500 sites, the estimates deviate by <10% from the simulated values.

Figure 1.

Relative error (estimated value divided by the true, simulated value) when estimating pa, sa, and their product pasa from simulated data plotted against the number of nucleotides subject to mutation. The bars indicate the interval between the 25% and the 75% quantile, with the point or line representing the median. The simulation parameters were pa = 0.015 and sa = 0.1.

Figure 2.

Correspondence between pa and sa estimates from simulations of 25,000 sites with simulated values of pa = 0.015 and sa = 0.1. The thin, dashed lines indicates the L-shaped curve that would be expected if the product pasa was constant at 0.015 × 0.1.

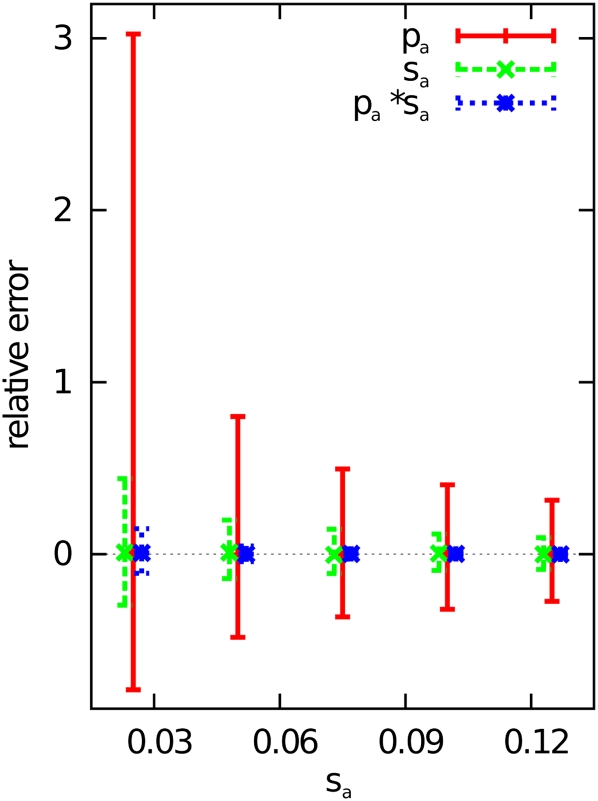

The accuracy of parameter estimation is shown as a function of the selection strength sa in Figure 3, again on the basis of simulations using 25,000 sites. This suggests that the accuracy of estimation of both pa and sa increases as the simulated value of sa is increased. Interestingly, this effect is stronger for pa. A likely reason for this behavior is that, if adaptive mutations are strongly selected, the resulting signal in the SFS (increased amounts of high-frequency nonsynonymous alleles) is easier to distinguish from random noise.

Figure 3.

Relative error when estimating pa, sa, and the product pasa from simulated data plotted against the selection strength sa. The bars indicate the interval between the 25% and the 75% quantile, with the point or line representing the median. The simulation parameters were pa = 0.015 and N = 25,000 (number of nucleotides subject to mutation).

Linkage effects

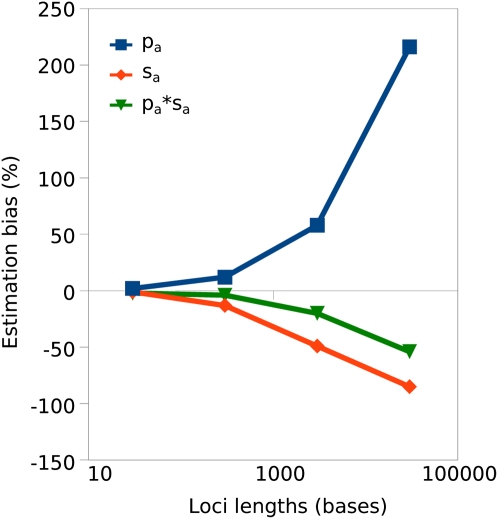

In a second set of simulations, the effect of linkage on parameter estimation was investigated. We used the program SFS_code (Hernandez 2008) to generate data in which the genome was split into varying numbers of unlinked loci within which linkage was complete. The results suggest that for many short loci (30 or 300 nucleotides), the simulated parameters can be estimated with little bias (Figure 4). For unlinked loci of longer length (e.g., 3000 nucleotides), pa tends to become overestimated and sa underestimated. The underestimation of sa may be due to two effects. First, there may be Hill–Robertson interference undermining selection on advantageous mutations linked to other advantageous mutations and to deleterious mutations. Second, genetic hitchhiking can drag neutral genetic variants to high frequency (Fay and Wu 2000). These high-frequency–derived mutations will give the appearance in the SFS of additional slightly advantageous mutations, and this will lead to overestimation of pa and consequent underestimation of sa. They may also distort the neutral SFS, leading to problems in correctly inferring the true demography. For loci of length <1000 bases, however, the extent of the bias observed is relatively modest; the complete linkage within loci assumed here is in any case likely to greatly exaggerate the effect of linkage compared with the typical situation for a Drosophila or mammalian gene (see McVean and Charlesworth 2000; Kaiser and Charlesworth 2009).

Figure 4.

Extent of estimation bias (as percentage of deviation from simulated parameter values) for simulations including linkage plotted against the lengths of loci within which linkage was complete. As x-axis values increase, the overall amount of linkage in the system therefore increases. Parameters of the simulation were θ = 4Nμ = 10−3, Nsd = −100, b = 0.3, pa = 0.1, Nsa = 10.

Analysis of two D. melanogaster data sets

We applied the ML method to polymorphism data sets of D. melanogaster protein-coding genes of Shapiro et al. (2007), consisting of 15 alleles from African flies, and of Callahan et al. (2011), consisting of 24 alleles sampled from Zimbabwe. The results from the two data sets are very similar (Tables 1 and 2). Under a constant population size model, the inclusion of a single class of positively selected mutations greatly increases the log likelihood (i.e., by 48 and 212 log-likelihood units, respectively, for the Shapiro et al. and Callahan et al. data sets). This model includes only two additional parameters (sa and pa); thus there is clearly a better fit to the data than that of the deleterious mutations-only model. If population size change is allowed, including adaptive mutations also significantly increases the log likelihood (by 65 and 148 log-likelihood units, respectively).

Table 1. ML parameter estimates and changes in log likelihood under models with constant or changing population sizes and with or without adaptive mutations from analysis of the Shapiro et al. (2007) data set.

| Model | N2/N1 | t/N2 | NeE(sd) | b | f0 | f2N | pa | Nesa | Δ log L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant population, no adaptation | — | — | −3 × 108 | 0.11 | 0.82 | 0.08 | 0 | — | 0 |

| Constant population, adaptation | — | — | −699 | 0.45 | 0.81 | 0.08 | 0.88% | 4.4 | 47.8 |

| Population size change, no adaptation | 0.6 | 3.1 | −2 × 106 | 0.14 | 0.83 | 0.08 | 0 | — | 8.8 |

| Population size change, adaptation | 0.5 | 3.1 | −372 | 0.54 | 0.83 | 0.08 | 0.96% | 4.5 | 73.5 |

Table 2. ML parameter estimates and changes in log likelihood under models with constant or changing population sizes and with or without adaptive mutations from analysis of the Callahan et al. (2011) data set.

| Model | N2/N1 | t/N2 | NeE(sd) | b | f0 | f2N | pa | Nesa | Δ log L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant population, no adaptation | — | — | −3 × 1015 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.09 | 0 | — | 0 |

| Constant population, adaptation | — | — | −103 | 1.36 | 0.79 | 0.08 | 2.10% | 4.9 | 211.8 |

| Population size change, no adaptation | 8.0 | 0.02 | −3 × 1015 | 0.05 | 0.53 | 0.09 | 0 | — | 94.3 |

| Population size change, adaptation | 5.5 | 0.02 | −363 | 0.70 | 0.60 | 0.08 | 1.80% | 5.7 | 242.0 |

The best-fitting models indicate changes in population size. Interestingly, for the data set of Callahan et al. (2011), a relatively large, quite recent increase (5.5-fold with adaptive mutations) is inferred, whereas for the African data set of Shapiro et al. (2007), a 50% decrease is found, which could be indicative of population admixture. This contrasts with the 20-fold increase in population size reported by Keightley and Eyre-Walker (2007) from an analysis of a similar data set, but using a folded SFS and assuming that no adaptive mutations contribute to polymorphism. This is presumably a consequence of the presence of high-frequency alleles that are not distinguished from low-frequency alleles in the folded SFS. However, if there are no adaptive mutations, simulation results indicate that similar results are obtained by analyzing either the folded or the unfolded SFS (Keightley and Eyre-Walker 2007). In addition, including selection on synonymous sites, which we have ignored here, has been shown to remove the signature of population expansion in the Zimbabwe population of D. melanogaster (Zeng and Charlesworth 2009), so that it is likely that ignoring population expansion could be justified. For both data sets, there were only negligible increases in log likelihood if two classes of advantageous mutational effects are included.

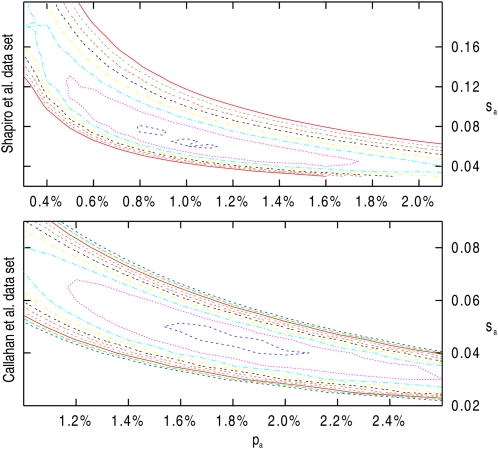

Under the best-fitting model (with population size change), the estimated percentage of sites under positive selection is pa = 0.96%, with a mean selection strength Nesa = 4.5 for the Shapiro et al. data set. For the Callahan et al. data set, the results suggest slightly higher frequencies of adaptive mutations with stronger effects, i.e., pa = 1.8% and Nesa = 5.7. Under the constant population size model, estimates are similar (pa = 0.88% and Nesa = 4.4 for Shapiro et al. and pa = 2.1% and Nesa = 4.9 for Callahan et al.). The variances of the adaptive mutation parameter estimates are relatively high, but they covary strongly. This is shown in plots of the log-likelihood landscape as a function of pa and sa around their ML estimates (Figure 5). The parameter estimates corresponding to a difference of 2 log-likelihood units from the maximum-likelihood estimates suggest that pa could be between 0.3% and 2.1% and Nesa could be between 2.3 and 13.5. A similar analysis of the Callahan et al. data set provides ∼95% confidence intervals for pa of 1.1–2.5% and for Nesa of 4.0–9.1, which are narrower than those obtained for the Shapiro et al. data set. This can possibly be explained by the higher number of alleles in this data set (24 as opposed to 15). Although the support limits are fairly wide for both parameters, the likelihood landscape clearly follows a “1/x” curve, indicating the high interdependence of the two parameters that we have observed in the simulations (see Figure 2).

Figure 5.

Contour plots of the log likelihood for the Shapiro et al. (top) and Callahan et al. (2011) (bottom) data as functions of pa and sa. The highest isoline is shown in dark blue and corresponds to −41,132.9 log-likelihood units for the Shapiro et al. (2007) data and to −25,702.6 for the Callahan et al. (2011) data. The following isolines indicate decreasing log likelihoods in intervals of 1 unit in the order purple, cyan, yellow, black, orange, gray, and red .

Under the best-fitting model, estimates of the proportion of adaptive substitutions from Equation 12 are α = 0.74 (for the Shapiro et al. data set) and α = 0.95 (for the Callahan et al. data set). These are higher than the estimates obtained using the unfolded SFS of 0.52 for the Shapiro et al. data set (Eyre-Walker and Keightley 2009) and 0.84 for the Callahan et al. data set. The increases in α are probably due to the fact that Eyre-Walker and Keightley (2009) assumed that advantageous mutations are strongly selected and contributed little to amino acid polymorphism. In the current method, advantageous mutations can contribute to polymorphism, which reduces the estimate of the contribution from effectively neutral mutations. As a consequence, advantageous mutations contribute proportionally more amino acid substitutions. A similar pattern was observed by Boyko et al. (2008).

Discussion

Our study was motivated by two factors. First, we wished to estimate the rate and fitness effects of advantageous mutations, since both these parameters are fundamental for our understanding of evolutionary adaptation. Second, whole-genome sequencing of multiple individuals sampled from natural populations promises to produce data that will make estimation of these parameters more tractable. Observations of excesses of amino acid substitutions over predictions based on standing polymorphism have provided evidence of widespread adaptive protein evolution in many species (Smith and Eyre-Walker 2002; Charlesworth and Eyre-Walker 2006; Welch 2006; Andolfatto 2007; Shapiro et al. 2007; Bachtrog 2008; Strasburg et al. 2009, 2011; Haddrill et al. 2010; Halligan et al. 2010; Ingvarsson 2010; Slotte et al. 2010). Under an additive model, the rate of adaptive substitution is largely determined by the product of the mutation rate to beneficial alleles and their average selection coefficient (sa), since the fixation probability of a new advantageous mutation is proportional to sa. This relationship constrains estimates of the rate and strength of adaptive evolution and makes inference strongly depend on the information used in the analysis. Sawyer et al. (2003) fitted a model to divergence and diversity data, in which a proportion of selected sites were assumed to be under strong negative selection, with other sites taking the strength of selection from a normal distribution. Under this model they inferred that amino acid substitutions are overwhelmingly a consequence of positive selection, but that the strength of selection on advantageous mutations is very weak. Andolfatto (2007) used an approach based on a comparison of nucleotide divergence and diversity and inferred a relatively high proportion of moderately beneficial amino acid mutations in D. melanogaster (i.e., Nesa somewhat above the nearly neutral range, implying sa of the order of 10−5). In contrast, Eyre-Walker (2006) and Macpherson et al. (2007) have inferred that the strength of selection acting upon advantageous mutations is strong (Nesa of the order of ≥100). Eyre-Walker (2006) assumed that the correlation between nucleotide diversity and recombination rate was due to selective sweeps, whereas Macpherson et al. (2007) inferred the strength of selection from an analysis of genome-wide heterogeneity in diversity levels in Drosophila. Recently, Sattath et al. (2011) suggested that these conflicting results can be resolved. By analyzing the pattern of diversity around synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions, they inferred that two classes of effects of adaptive mutations, with effects of ∼0.5% and ∼0.01%, best explain polymorphism and divergence data in Drosophila. Under this model the class of larger-effect mutations is responsible for most selective sweeps. The discrepancy between these results principally arises because the different approaches consider different scales over which an adaptive fixation event is expected to reduce nucleotide diversity in the genome (Sella et al. 2009).

In the simulations, we first evaluated the performance of our inference procedure using data generated under the same model as employed in the analysis. We inferred that a modest amount of data (≤10,000 sites) are needed to estimate the product of the proportion of adaptive mutations (pa) and sa, which is closely related to the proportion of adaptive substitutions (α, Equation 12). However, the two parameters are strongly negatively correlated, such that data can typically be explained nearly as well by high values of sa and low values of pa and vice versa. The reason for this is that the ratio α/(1 – α) is equal to paλa/(1 – pa )λd ≈ paλa /λd, where λa and λd are the fixation probabilities of advantageous and deleterious mutations relative to the neutral value, respectively. Provided that α and λd are accurately estimated, paλa is thus strongly determined, and λa is proportional to sa. Obtaining accurate estimates of pa and sa separately requires of the order of ≥105 sites. Furthermore, parameters for weakly selected advantageous mutations are difficult to disentangle from parameters for mildly deleterious mutations, even in very large data sets. Whereas estimating the proportion or relative rate of adaptive substitutions (α or ωa, respectively), which are functions of the product of pa and sa, largely depends on the frequency of sites that are fixed for the derived allele, separately estimating pa and sa depends on the presence of high-frequency polymorphisms (i.e., adaptive mutations that are on their way to fixation). Alleles at these frequencies are expected to be uncommon; hence there is the need for genome-wide scale data for accurate inference.

We then investigated the effect of linkage on parameter inference. This is expected to potentially lead to biased parameter estimates, because selection on advantageous mutations will tend to change the frequencies of blocks of linked sites and can lead to excesses of high-frequency neutral and deleterious polymorphisms over neutral expectation (Fay and Wu 2000). We employed the SFS_code software developed by Hernandez (2008) and were able to make qualitative predictions about the nature of biases expected. Consistent with previous results on the effects of linkage on estimates of α (Eyre-Walker and Keightley 2009), we found that, provided that linkage is not too tight, the product of sa and pa is reasonably unbiased (Figure 4). However, we also found that linkage tends to lead to underestimation of sa and overestimation of pa. Presumably, increased linkage increases the effect of Hill–Robertson interference, so the effectiveness of selection on individual positively selected alleles is reduced, and hence estimates of sa are decreased. Furthermore, hitchhiking generates high-frequency alleles that can distort both the neutral and the selected SFSs. Due to the limitations of the model and computing time, we are unable to make a quantitative prediction of the amount of bias expected for a real data set (for example, the Drosophila data set that we have analyzed here). To do so would require a more comprehensive simulation of an entire chromosome, with realistic distributions of sites subject to selection and amounts of recombination (at least on a scale Ner, where r is the recombination rate between sites). However, it is likely that the scenarios investigated in Figure 4 represent much tighter linkage than is realistic for Drosophila, since we simulated loci with no intragenic recombination, and so will overestimate the probable effects of linkage in a natural population of flies.

Our approach has several other limitations, some of which that are intrinsic to the information used in the analysis and some that might be overcome with further work. We have implicitly assumed that variation is maintained under mutation, selection, and drift balance and disregarded the possibility that other processes, such as migration and balancing selection, maintain variation. We have fitted multiple categories of sa, but in principle a distribution of sa could be fitted to the model. However, it is doubtful whether the information would be sufficient to estimate parameters of a distribution in practice. We have fitted a gamma distribution of negatively selected mutational effects. Although this distribution can take a wide variety of shapes, it is always unimodal and may fail to model more complex distributions adequately. However, if we fit a distribution with n discrete bins, we have shown that this model is capable of adequately fitting complex distributions (e.g., mixtures of gamma and beta distributions), the only limitation being the amount of data available (A. Kousathanas and P. D. Keightley, unpublished data). We have used the relatively simple demographic model of a step change in population size. However, selection parameters are recovered with little bias, even if the true scenario is substantially more complex (Keightley and Eyre-Walker 2007; Eyre-Walker and Keightley 2009). In our analysis, we have assumed that synonymous sites evolve neutrally, an assumption that is violated for this data set (Zeng and Charlesworth 2009). We have also assumed that the mutation rates for synonymous and nonsynonymous sites are equal, an assumption that is also violated, since they differ significantly in GC content. These departures from the model assumptions will presumably partially cancel each other, since the higher GC content of synonymous sites implies that they have a higher mutation rate than nonsynonymous sites. However, the net effect is uncertain.

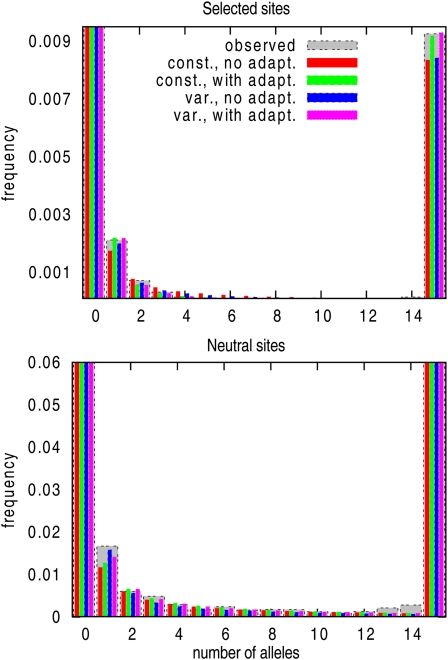

Our analysis of two extensive data sets of D. melanogaster protein-coding gene sequences of Shapiro et al. (2007) and Callahan et al. (2011) revealed clear differences in the fit among the different models. The best-fitting model included adaptive mutations and a modest change in recent effective population size. Whether or not population size change was included in the model had little influence on estimates of adaptive mutation parameters. We obtained similar results for the two data sets, suggesting that ∼1.5% of amino acid mutations are adaptive with an average selection strength Nesa ∼ 5. The inclusion of adaptive mutations led to very significant increases in likelihood (reported in Tables 1 and 2) and resulted in a substantially better fit. Figure 6 shows the fit of the inferred SFSs to the true SFSs for selected and neutral sites for the data set from Shapiro et al. (2007). The two models that include adaptive mutations (Figure 6, green and purple bars) give the best fit to the selected SFSs, and only the model that additionally includes population size change (Figure 6, green bars) also fits the neutral SFS. It should be noted, however, that parameter inference requires substantial amounts of data. The simulations together with the likelihood plot for the real data (which is indicative of the variances, Figure 5) clearly show that the product pasa can be estimated quite accurately from small data sets, but disentangling pa from sa can be done with high confidence only from larger data sets. The consistency among the two D. melanogaster data sets used here indicates that they are sufficiently large to get reasonably accurate estimates. But larger data sets from whole-genome sequencing of samples of individuals from natural populations will improve the accuracy of the estimates and shed more light on the role of adaptive mutations in molecular evolution.

Figure 6.

Fit of the expected SFS (thin, colored bars) for selected and neutral sites to the observed SFS (thick, gray bar) for the Shapiro et al. (2007) data set. For illustration purposes, only the subset of genes with 15 alleles is used, and the parameters to generate the expected SFS have been estimated from this subset.

Software availability

The method is available via P. D. Keightley’s website, http://homepages.ed.ac.uk/eang33/. Source files for the project have been deposited in sourceforge http://sourceforge.net/.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joshua Shapiro and Peter Andolfatto for providing Drosophila polymorphism data and Kai Zeng for providing the alignments to D. yakuba. A.S. was supported by a fellowship for prospective researchers from the Swiss National Science Foundation. P.D.K. acknowledges support from grants from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) of the United Kingdom and the Wellcome Trust. B.C. acknowledges support from grants from the BBSRC.

Literature Cited

- Akashi H., 1995. Inferring weak selection from patterns of polymorphism and divergence at “silent” sites in Drosophila DNA. Genetics 139: 1067–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andolfatto P., 2007. Hitchhiking effects of recurrent beneficial amino acid substitutions in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Genome Res. 17: 1755–1762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachtrog D., 2008. Similar rates of protein adaptation in Drosophila miranda and D. melanogaster, two species with different current effective population sizes. BMC Evol. Biol. 8: 334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyko A. R., Williamson S. H., Indap A. R., Degenhardt J. D., Hernandez R. D., et al. , 2008. Assessing the evolutionary impact of amino acid mutations in the human genome. PLoS Genet. 4: e1000083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulmer M., 1991. The selection-mutation-drift theory of synonymous codon usage. Genetics 129: 897–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante C. D., Nielsen R., Sawyer S. A., Olsen K. M., Puruggannan M. D., et al. , 2002. The cost of inbreeding in Arabidopsis. Nature 416: 531–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan B., Neher R. A., Bachtrog D., Andolfatto P., Shraiman H., 2011. Correlated evolution of nearby residues in Drosophilid proteins. PLoS Genet. 7: e1001315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth B., 2011. Molecular population genomics: a brief history. Genet. Res. 92: 397–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth J., Eyre-Walker A., 2006. The rate of adaptive evolution in enteric bacteria. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23: 1348–1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox D. R., Miller H. D., 1977. The Theory of Stochastic Processes. Chapman & Hall, London [Google Scholar]

- Eyre-Walker A., 2006. The rate of adaptive evolution at the molecular level. Trends. Evol. Ecol. 21: 569–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre-Walker A., Keightley P. D., 2007. The distribution of fitness effects of new mutations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8: 610–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre-Walker A., Keightley P. D., 2009. Estimating the rate of adaptive molecular evolution in the presence of slightly deleterious mutations and population size change. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26: 2097–2108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre-Walker A., Woolfit M., Phelps T., 2006. The distribution of fitness of new deleterious amino acid mutations in humans. Genetics 173: 891–900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay J. C., Wu C.-I., 2000. Hitchhiking under positive Darwinian selection. Genetics 155: 1405–1413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher R. A., 1930. The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. Clarendon Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- Gossmann T. I., Song B.-H., Windsor A. J., Mitchell-Olds T., Dixon C. J., et al. , 2010. Genome wide analyses reveal little evidence for adaptive evolution in many plant species. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27: 1822–1832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S., Dufayard J., Lefort V., Anisimova M., Hordijk W., et al. , 2010. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 59: 307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddrill P. R., Loewe L., Charlesworth B., 2010. Estimating the parameters of selection on nonsynonymous mutations in Drosophila pseudoobscura and D. miranda. Genetics 185: 1381–1396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halligan D. L., Oliver F., Eyre-Walker A., Harr B., Keightley P. D., 2010. Evidence for pervasive adaptive protein evolution in wild mice. PLoS Genet. 6: e1000825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez R. D., 2008. A flexible forward simulator for populations subject to selection and demography. Bioinformatics 24: 2786–2787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez R. D., Williamson S. H., Bustamante C. D., 2007. Context dependence, ancestral misidentification, and spurious signatures of natural selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 248: 1792–1800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingvarsson P. K., 2010. Natural selection on synonymous and nonsynonymous mutations shapes patterns of polymorphism in Populus tremula. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27: 650–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen J. D., 2009. On reconciling single and recurrent hitchhiking models. Genome Biol. Evol. 1: 320–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen J. D., Bachtrog D., 2010. Characterizing recurrent positive selection at fast-evolving genes in Drosophila miranda and Drosophila pseudoobscura. Genome Biol. Evol. 2: 371–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen J. D., Thornton K. R., Andolfatto P., 2008. An approximate Bayesian estimator suggests strong, recurrent selective sweeps in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 4: e1000198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser V. B., Charlesworth B., 2009. The effects of deleterious mutations on evolution in non-recombining genomes. Trends Genet. 25: 9–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keightley P. D., Eyre-Walker A., 2007. Joint inference of the distribution of fitness effects of deleterious mutations and population demography based on nucleotide polymorphism frequencies. Genetics 177: 2251–2261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent W. J., Sugnet C. W, Furey T. S., Roskin K. M., Pringle T. H., et al. , 2002. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 12: 996–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. P., Stephan W., 2006. Inferring the demographic history and rate of adaptive substitution in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2: 1580–1589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewe L., Charlesworth B., Bartolomé C., Nöel V., 2006. Estimating selection on non-synonymous mutations. Genetics 172: 1079–1092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson J. M., Sella G., Davis J. C., Petrov D. A., 2007. Genomewide spatial correspondence between nonsynonymous divergence and neutral polymorphism reveals extensive adaptation in Drosophila. Genetics 177: 2083–2099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVean G. A. T., Charlesworth B., 2000. The effects of Hill-Robertson interference between weakly selected mutations on patterns of molecular evolution and variation. Genetics 155: 929–944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelder J. A., Mead R., 1965. A simplex method for function minimization. Comput. J. 7: 308–313 [Google Scholar]

- Ohta T., Kimura M., 1971. On the constancy of the evolutionary rate of cistrons. J. Mol. Evol. 1: 18–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piganeau G. V., Eyre-Walker A., 2003. Estimating the distribution of fitness effects from DNA sequence data: implications for the molecular clock. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 10335–10340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press W. H., Teukolsky S. A., Vetterling W. T., Flannery B. P., 1992. Numerical Recipes in C, Ed. 2 Cambridge University Press, Cambridge/London/New York [Google Scholar]

- Sattath S., Elyashiv E., Kolodny O., Rinott Y., Sella G., 2011. Pervasive adaptive protein evolution apparent in diversity patterns around amino acid substitutions in Drosophila simulans. PLoS Genet. 7: e1001302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer S. A., Dykhuizen D. E., Hartl D. L., 1987. Confidence interval for the number of selectively neutral amino acid polymorphisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84: 6225–6228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer S., Kulathinal R. J., Bustamante C. D., Hartl D. L., 2003. Bayesian analysis suggests that most amino acid replacements in Drosophila are driven by positive selection. J. Mol. Evol. 57: S154–S164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sella G., Petrov D. A., Przeworski M., Andolfatto P., 2009. Pervasive natural selection in the Drosophila genome? PLoS Genet. 5: e1000495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro J. A., Huang W., Zhang C., Hubisz M. J., Lu J., et al. , 2007. Adaptive genetic evolution in the Drosophila genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 2271–2276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp P. M., Emery L. R., Zeng K., 2010. Forces that influence the evolution of codon bias. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 365: 1203–1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotte T., Foxe J. P., Hazzouri K. M., Wright S. I., 2010. Genome-wide evidence for efficient positive and purifying selection in Capsella grandiflora, a plant species with a large effective population size. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27: 1813–1821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith N. G. C., Eyre-Walker A., 2002. Adaptive protein evolution in Drosophila. Nature 415: 1022–1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasburg J. L., Scotti-Saintagne C., Scotti I., Lai Z., Rieseberg L. H., 2009. Genomic patterns of adaptive divergence between chromosomally differentiated sunflower species. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26: 1341–1355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasburg J. L., Kane N. C., Raduski A. R., Bonin A., Michelmore R., et al. , 2011. Effective population size is positively correlated with levels of adaptive divergence among annual sunflowers. Mol. Biol. Evol. 285: 1569–1580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavaré S., 1986. Some probabilistic and statistical problems on the analysis of DNA sequences. Lect. Math Life Sci. 17: 57–86 [Google Scholar]

- Welch J. J., 2006. Estimating the genome-wide rate of adaptive protein evolution in Drosophila. Genetics 173: 821–837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S. I., Andolfatto P., 2008. The impact of natural selection on the genome: emerging patterns in Drosophila and Arabidopsis. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 39: 193–213 [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., 1994. Maximum likelihood phylogenetic estimation from DNA sequences with variable rates over sites: approximate methods. J. Mol. Evol. 39: 306–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng K., Charlesworth B., 2009. Estimating selection intensity on synonymous codon usage in a nonequilibrium population. Genetics 183: 651–662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]