Abstract

The purpose of the current study was to examine sudden gains in those receiving treatment for PTSD and whether these rapid changes were related to overall symptom reduction in a small sample of female assault survivors with PTSD undergoing prolonged exposure (PE) therapy. Sudden gains were found to occur in 52% of the sample. Among those who experienced a sudden gain, the average magnitude (12.4 points) accounted for 61% of overall symptom reduction. Importantly, treatment outcome was better for those who experienced sudden gains than those who did not. The experience of a sudden gain may result in patients becoming more fully engaged with treatment, and recognition of them may result in identifying potential process-related predictors of treatment response.

Keywords: PTSD, CBT, Sudden gains

Sudden gains in prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD

In recent years, a growing body of research has examined the phenomenon of rapid, large decreases in symptoms from one session to the next in treatment, and these reductions have been labeled “sudden gains” (Tang & DeRubeis, 1999). Although often observed clinically, these sudden gains were first identified empirically in adults receiving cognitive-behavioral treatment (CBT) for major depression (Tang & DeRubeis, 1999). Since then, others have replicated these findings, suggesting that sudden gains occur in as much as 39–46% of those receiving treatment for depression (Gaynor et al., 2003; Hardy et al., 2005; Kelly, Roberts, & Ciesla, 2005; Tang, DeRubeis, Beberman, & Pham, 2005; Tang, Luborsky, & Andrusyna, 2002; Vittengl, Clark, & Jarrett, 2005). Sudden gains occur throughout the course of treatment and are generally related to overall symptom reduction and maintenance of gains through follow-up (e.g., Hardy et al., 2005; Tang & DeRubeis, 1999).

The presence of sudden gains may be clinically meaningful in several ways (Tang & DeRubeis, 1999). First, the experience of a sudden gain may serve as an impetus towards “buy in” with the treatment model and engagement, thus potentially leading to greater benefit. Further, if therapists are attuned to and aware of these reductions insymptoms, they may beableto guide treatment towards targeting residual symptoms earlier on in the treatment protocol, allowing greater time for remaining symptom improvement. Finally, examination of the ways in which change unfolds during treatment may help to identify potential process-related predictors of treatment response, which may ultimately lead to more effective and efficient interventions (Tang & DeRubeis, 1999).

Treatment outcome research for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has grown significantly in the past two decades, and results of large-scale randomized control trials provide evidence for the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral approaches, particularly exposure based ones (see Institute of Medicine, 2007). Prolonged exposure (PE) is a specific cognitive-behavioral treatment with well-established efficacy (e.g., Devilly & Spence, 1999; Foa, Rothbaum, Riggs, & Murdock, 1991, 1999, 2005; Resick, Nishith, Weaver, Astin, & Feuer, 2002; Schnurr et al., 2007; Tarrier, Sommerfield, Pilgrim, & Faragher, 2000). In PE, patients are encouraged to recount the memory of their traumatic event (i.e., imaginal exposure) and to approach trauma-related reminders (i.e., in vivo exposure). Despite the strong empirical support for the efficacy of PE, not all patients receive benefit from the treatment. Across studies, 12–47% retain their PTSD diagnosis at the end of treatment or experience an exacerbation of symptoms post-treatment; (Foa et al., 1999, 2005; Resick et al., 2002; Schnurr et al., 2007). Further, although some studies suggest various predictors of treatment response (e.g., Ehlers et al., 1998; Jaycox, Foa, & Morral, 1998; Tarrier et al., 2000), variables such as age, gender, PTSD severity, and trauma type have not been consistently related to outcome across studies.

Even among those who do respond to the treatment, little is known about the process or mechanisms of change in PE for chronic PTSD. Though some process variables have been examined (e.g., symptom exacerbation; Foa, Zoellner, Feeny, Hembree, & Alvarez-Conrad, 2002; engagement: Jaycox et al., 1998), much remains to be learned regarding how and when symptoms change in treatment. Identification of sudden gains in PE, and any relationship between these sudden gains and treatment outcome, may be one step towards a fuller understanding of process of change in PE and factors that influence treatment response. We examined: (1) whether and when sudden gains occur in PE; (2) the proportion of total symptom severity accounted for by these sudden gains; (3) differences in treatment outcome for those who experience these gains; and (4) whether gains experienced are sustained or lost during treatment (reversal of gain).

Method

Participants

Participants were female survivors of sexual assault or non-sexual assault who were enrolled in a treatment outcome study and received PE (n = 23). Among these women, 72.7% experienced a sexual assault. Mean time since assault was 8.57 years (SD = 10.08). Participants were recruited via referrals from medical professionals, local victim assistance agencies, and media advertisements in two large metropolitan areas. Exclusion criteria included no PTSD or PTSD not primary; a primary diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, unstable bipolar disorder, or current alcohol/ drug dependence; or an ongoing relationship with the perpetrator of the assault.

On average, participants were 29.57 years of age (SD = 9.09). Participants were Caucasian (78.3%) and African American (21.7%). Half of the sample (50%) had an annual household income of $20,000 or less and 34.8% were working full time at the time of the pre-treatment assessment.

Measures

PTSD Symptom Scale-Self-Report (PSS-SR; Foa, Riggs, Dancu, & Rothbaum, 1993)

The PSS-SR was used to assess the severity of DSM-IV (APA, 1994) PTSD symptoms. The PSS-SR has high internal consistency (α = .91) and excellent interrater reliability for PTSD severity (r = .97) (Foa et al., 1993). Cronbach’s alpha at pre-treatment was .70.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

The BDI (Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961) is a 21-item self-report measure assessing depression severity. The BDI demonstrated moderately high correlations with clinician ratings of depression in a sample of female assault survivors, ranging from .62 to .66 (Foa et al., 1993). Cronbach’s alpha was .92.

Social Adjustment Scale (SAS)

The SAS (Weissman & Paykel, 1974) is a semi-structured interview used to assess an individual’s functioning in six domains (e.g., work, social, family) over the past two weeks. The SAS has high internal consistency (r = .74) and test–retest reliability (Edwards, Yarvis, Mueller, Zingale, & Wagman, 1978). For the current study, the global score was used as a measure of overall functioning.

Utility of Techniques Inventory (UTI; Foa et al., 2002)

The UTI is a measure of homework adherence in which items (i.e., “How often did you do in vivo exercises since the last session?”) are answered on a five point scale from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“more than 7 times”). The UTI was completed at the beginning of each treatment session N as a report of homework completed between session N-1 and session N.

Prolonged Exposure (PE) Therapy (Foa, Hembree, & Rothbaum, 2007)

PE consists of psychoeducation, breathing retraining, repeated imaginal exposure to the target traumatic event, and encouragement to systematically confront feared and avoided trauma-related reminders (i.e., in vivo exposure). An orientation to the treatment is initiated in session one, psychoeducation regarding common reactions to trauma and in vivo exposure are introduced at session two, and imaginal exposure is initiated in session three. Throughout the remainder of treatment, each session consists of a review of in vivo and imaginal exposure completed as homework, conducting and processing of imaginal exposure, and planning for the next week’s homework.

Treatment integrity

Ratings for treatment integrity were based on Foa et al. (2005). Trained raters reviewed 10% of treatment session videotapes for essential treatment components and found that PE therapists completed 94% of all essential components. There were no violations to the treatment protocol observed.

Procedure

Study eligibility was determined through an initial evaluation conducted by experienced independent evaluators, which included the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1995) to confirm or rule-out a primary diagnosis of PTSD, and the SAS (Weissman & Paykel, 1974). Participants also completed a series of self-reports at intake, which included the PSS-SR (Foa et al., 1993) and the BDI (Beck et al., 1961). Data for the current study were taken from a larger randomized clinical trial for PTSD, details of which are provided elsewhere (Feeny, Zoellner, Mavissakalian, & Roy-Byrne, 2009). Self-report measures, including the PSS-SR and the UTI, were completed prior to every session, before the session began. Participants also completed assessments at post-treatment and follow-up at, on average, 4.35 months (SD = 4.79) post-treatment. These assessments included the same battery of measures as the pre-treatment assessment.

Operational definition of sudden gains & analytic plan

Tang and DeRubeis (1999) established three primary criteria for identifying sudden gains in treatment, which were utilized for the current study. First, to establish that the gains were large in absolute terms, sudden gains were defined as clinically significant reductions in PTSD symptoms between any session N and session N + 1 (see Tang & DeRubeis, 1999). Using guidelines proposed by Jacobson and Truax (1991), we computed reliable clinically significant change in PTSD symptoms based on the 2- to 3-week test–retest reliability (.83) and standard deviation (10.54) originally reported for the PSS-SR (Foa et al., 1993), which yielded a standard error of the difference between two administrations of the measure of 6.15 (Devilly & Foa, 2001). Thus, only those reductions of at least seven points on the PSS-SR were identified for consideration as sudden gains. Secondly, to meet criteria as a sudden gain, the magnitude of the gain must be large, representing a reduction of at least 25% of the pre-gain session symptom severity score. The third criterion proposed by Tang and DeRubeis (i.e., gains should be large relative to symptom fluctuations before and after the gain) involves comparing the mean score of three pre-gain sessions to the mean score of the gain session and two post-gain sessions, to assess for significant differences in the means. Although this criterion has been criticized elsewhere, for uniformity with previous sudden gain investigations we opted to include this criterion, using critical values of t(4) = 2.78, p = .05 (or t (3) = 3.19, p = .05, in cases where only 2 pre-or post-gain sessions were available). Sudden gains occurred when all three conditions described above were met.

For our primary analyses evaluating main effects and interaction of time (pre- and post-treatment) × group (sudden gains and no sudden gains), we followed Jaccard and Guilamo-Ramos’ (2002a, 2002b) guidelines for single degree of freedom contrasts. To evaluate whether sudden gains were sustained during the remainder of treatment, we evaluated reversal of sudden gains using Tang and DeRubeis (1999) method in which they considered a reversal to be present when a patient experienced an increase in reported symptoms of at least 50% of the improvement originally experienced during the sudden gain. For all analyses, missing data were handled using the last observation carried forward method where possible. Those with missing data did not differ significantly with regard to any of the demographic or psychological variables of interest in this study.

Results

Occurrence of sudden gains

Evaluating reductions in symptoms for sudden gains revealed that reductions of at least 7 points on the PSS-SR were observed in 42 of 207 between session intervals (20%). These observed reductions in symptoms were found for 83% of patients (n = 19). When these 42 observations were analyzed to examine magnitude of the reduction, 10 of 42 observed reductions in symptoms did not exceed 25% of the pre-gain severity score, leaving 32 of 42 (76%) remaining. After evaluating whether these gains were large relative to pre-gain and post-gain symptom fluctuation, 15 of the 32 potential observations (47%) remained.

Overall, a total of 15 sudden gains were experienced by 12 of the 23 (52%) participants, only two of whom experienced multiple sudden gains during the course of treatment (one person experienced two gains and one person had three gains during treatment). Sudden gains occurred throughout treatment, with 8 of 15 gains between sessions 3–5 (4 of those 8 were reported at session 3, before initiation of imaginal exposure) and 7 of 15 gains between sessions 7–9. The mean magnitude of sudden gain was 12.4 points on the PSS-SR (SD = 4.47), accounting for 61% of overall symptom reduction among those who experienced a sudden gain in treatment.

Comparing those who experienced sudden gains vs. those who did not

Pre- and post-treatment comparisons

We compared those who experienced a sudden gain to those who did not on demographic and psychosocial variables. At the beginning of treatment, the two groups did not differ on any demographic variables (i.e., age, race, relationship status, employment, years of education, and income). For psychosocial factors, there were no differences between groups on self-reported PTSD (PSS-SR) or global functioning (SAS) at pre-treatment. There was a significant difference between groups on BDI scores at pre-treatment, with those who experienced a sudden gain reporting less severe depression than those who did not (t (21) = 2.48, p < .05, partial η2 = .23), though both groups reported mild to moderate depression symptoms on average (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Pre- and Post-treatment PTSD, depression, and functioning in those with and without sudden gain.

| Measure | Mean (SD)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Sudden gains (n = 12) | No sudden gains (n = 11) | |

| Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale (PSS-SR) | ||

| Pre-Treatment | 30.25 (6.77) | 31.18 (7.92) |

| Post-Treatment | 9.92 (6.30) | 21.75 (11.09) |

| Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) | ||

| Pre-Treatment | 17.31 (7.17) | 27.18 (11.59) |

| Post-Treatment | 6.03 (6.08) | 15.82 (6.92) |

| Social Adjustment Scale (SAS) | ||

| Pre-Treatment | 4.25 (1.14) | 4.88 (1.17) |

| Post-Treatment | 2.58 (.79) | 3.09 (.94) |

Note. N = 23 (12 with sudden gains and 11 without sudden gains on the PSS-SR), except SAS where N = 21 (12 with sudden gains and 9 without sudden gains).

We next conducted a series of single degree of freedom contrasts to evaluate whether those who experienced a sudden gain benefited from treatment to the same degree as those who did not experience a sudden gain. As can be seen in Table 2, both the sudden gains group and the no-sudden gains group experienced significant reductions in PTSD symptoms from pre- to post-treatment, however this effect was stronger for those who experienced sudden gains. Depression and functioning improved over time for both the sudden gains and no-sudden gains groups.

Table 2.

Single degree of freedom contrasts for PTSD, depression, and functioning.

| Measure & Contrast | Parameter value | SE | 95% Lower CI | 95% Upper CI | t | p | Partial h2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSS-SR | |||||||

| 1. Pre-Post for SG | 20.33 | 3.68 | 12.67 | 27.99 | 5.52 | <.001 | .59 |

| 2. Pre-Post for No SG | 9.44 | 3.85 | 1.43 | 17.44 | 2.45 | .02 | .22 |

| 3. IC: Pre, Post by SG, No SG | 10.89 | 5.44 | −.18 | 21.98 | 2.05 | .05 | .17 |

| BDI | |||||||

| 1. Pre-Post for SG | 11.28 | 3.27 | 4.48 | 18.09 | 3.45 | <.01 | .36 |

| 2. Pre-Post for No SG | 11.36 | 3.42 | 4.25 | 18.47 | 3.32 | <.01 | .35 |

| 3. IC: Pre, Post by SG, No SG | −.08 | 4.73 | −9.92 | 9.77 | −.02 | .99 | .00 |

| SAS | |||||||

| 1. Pre-Post for SG | 1.67 | .37 | .90 | 2.43 | 4.54 | <.001 | .52 |

| 2. Pre-Post for No SG | 1.67 | .42 | .78 | 2.55 | 3.94 | .001 | .45 |

| 3. IC: Pre, Post by SG, No SG | .00 | .56 | −1.17 | 1.17 | .00 | 1.00 | .00 |

Note. Pre = pre-treatment, Post = post-treatment, SG = sudden gain, SE = standard error, CI = confidence interval, IC = interaction contrast.

In-session comparisons

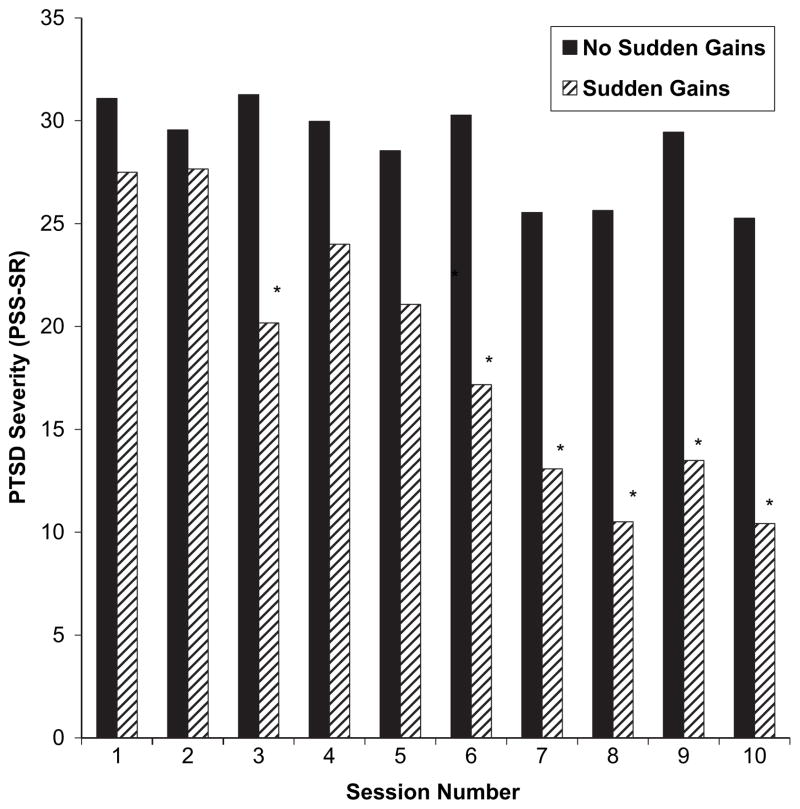

We also compared the self-reported PTSD symptom severity scores (PSS-SR) for those who experienced a sudden gain to those who did not at each session. As seen in Fig. 1, significant differences between these groups initially emerged at session 3 and continued from sessions 6–10, when the PTSD severity scores were significantly lower for the sudden gain group than for those who did not experience a sudden gain (Session 1: ns; Session 2: ns; Session 3: t(21) = 3.19, p < .01, Cohen’s d = .1.34; Session 4: ns; Session 5: ns; Session 6: t(21) = 3.62, p < .01, Cohen’s d = 1.53; Session 7: t(21) = 3.21, p < .01, Cohen’s d = 1.35; Session 8: t(21) = 4.41, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.84; Session 9: t(21) = 4.65, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.96; Session 10: t(21) = 3.87, p < .01, Cohen’s d = 2.17). Significant differences between these groups emerge relatively early in treatment and remain, particularly towards the end of treatment.

Fig. 1.

Self-reported PTSD severity scores (PSS-SR) of the patients who experienced sudden gains compared with those who did not. *p < .01.

Reversal of sudden gains

We examined the presence of reversals of gains (i.e., defined as an increase in reported symptoms of at least 50% of the improvement originally experienced during the sudden gain). Only two of 12 patients who experienced a sudden gain experienced a reversal of the gain before the end of treatment. Nonetheless, these participants experienced a 36% and 53% reduction in self-reported PTSD symptom severity from pre- to post-treatment respectively, though their post-treatment scores were more similar to those not experiencing a sudden gain.

Relationship between sudden gains and treatment adherence

Finally, we examined whether sudden gains were associated with better exposure homework adherence (UTI). There was no strong association (r = .37, ns).

Discussion

Similar to previous studies showing that sudden gains occur in a portion of individuals receiving treatment for depression and social phobia (Gaynor et al., 2003; Hardy et al., 2005; Hofmann, Schulz, Meuret, Moscovitch, & Suvak, 2006; Kelly et al., 2005; Tang et al., 2002, 2005; Vittengl et al., 2005), results of the current study suggest that sudden gains also occur among those who receive exposure therapy for PTSD. Indeed, approximately half of these women with chronic, assault-related PTSD reported sudden, relatively large improvements in their symptoms. Further, those who experienced such sudden gains had lower PTSD severity at post-treatment, which is also consistent with other investigations (Hardy et al., 2005; Tang & DeRubeis, 1999). The frequency of these gains and their association with treatment outcome suggests that the experience of sudden gains is clinically meaningful.

These results are consistent with Wilson’s (1999) suggestion that rapid reductions of symptoms may likely be a common phenomenon across various forms of psychopathology. That sudden gains occurred in approximately half of the sample is noteworthy and may suggest that this is a relatively common pattern of symptom improvement in CBT for PTSD. Indeed, though clinicians may worry about sudden symptom worsening with exposure therapy (Foa et al., 2002), what seems more characteristic of symptom change is just the opposite: sudden, large improvements in PTSD symptoms.

Notably, gains were distributed over the course of treatment with approximately one half of all gains occurring during early treatment (reported at sessions 3–5) and one half reported in later treatment (sessions 7–9), and it is possible that there may be important differences between these groups. Among those who experienced early sudden gains, 50% of early gains were reported before the initiation of imaginal exposure. Thus, for this group, change may have been mediated by the initiation of breathing retraining, psychoeducation, or in vivo exposure, though mediated change via breathing retraining seems unlikely (see Taylor et al., 2003). This is also consistent with other research that suggests that imaginal exposure is not necessary for change in treatment for PTSD (e.g., Bryant, Moulds, Guthrie, Dang, & Nixon, 2003). For those who reported sudden gains later in treatment, it is possible they may have responded more to repeated imaginal exposure or a shift in focus to “hot spots” in the traumatic memory (Foa et al., 2007). These late occurring sudden gains should be reassuring to clinicians who may begin to wonder as treatment proceeds whether clients will actually respond to exposure therapy.

A particular strength of the current study lies in the examination of a range of psychopathology and functioning measures in relation to sudden gains. We found that PTSD, depression, and functioning all improved with time. Importantly, however, we found that those who experienced a sudden gain had a greater reduction in PTSD symptoms than those who did not. Thus, regardless of whether a patient experienced a sudden gain, their symptoms improved with treatment over time, yet the experience of a sudden gain was related to a more dramatic improvement in PTSD severity. This is consistent with examinations of the sudden gain phenomenon in the depression literature (e.g., Hardy et al., 2005; Tang & DeRubeis, 1999).

Interestingly, there were no differences in pre-treatment PTSD severity between those experiencing sudden gains and those who did not; yet, individuals who experienced sudden gains reported lower initial depression than those who did not, with the effect size being relatively large. Indeed, the presence of more severe depression, and not overall symptom severity, may actually inhibit the likelihood of experiencing a sudden gain in treatment for PTSD. Those who have more severe depression may have a more difficult time engaging with the demands of treatment, thus limiting the benefits they receive. Further, those with severe depression may have a negative attributional style (e.g., Miller & Norman, 1979) that is less amenable to change than for those with less severe depression (e.g., Dobson & Shaw, 1986), resulting in a decreased likelihood of experiencing a rapid reduction in symptoms.

In-session data revealed that, at session three (after initiation of in vivo exposure) and between sessions 6 and 10, there were significant differences between those who experienced a sudden gain and those who did not, with sudden gainers reporting fewer PTSD symptoms. Overall, this suggests stability of the gains over time. This is clinically meaningful, in that the gains that are made are maintained over the duration of treatment. Indeed, only two patients experienced a “reversal” of their sudden gain, suggesting that these sudden reductions in symptoms do not appear to be fleeting or false but rather real, stable improvements in symptoms that relate to treatment outcome for those who experience them.

Clinical implications

For the client, the experience of a sudden gain in treatment could have a significant impact on the course of subsequent treatment sessions. The experience of a sudden gain may bolster important process variables such as therapeutic alliance, confidence in therapeutic approach, and motivation for compliance with treatment (e.g., Tang & DeRubeis, 1999). Knowledge of the presence of sudden gains may help clinicians to identify the active elements in “critical sessions” that precede sudden gains, which may increase the overall efficiency of their interventions (Busch, Kanter, Landes, & Kohlenberg, 2006).

Limitations, future directions, and conclusion

Several caveats regarding these findings should be noted. First, the sample in the present study was limited to female assault survivors. Whether sudden gains occur among other trauma survivors in treatment for PTSD or within other treatments for PTSD is unknown. Further, this was a small sample of women enrolled in a small open clinical trial. Future research should attempt to replicate these results in a larger sample. Another related limitation of the current study is that we did not examine potential mediators of the sudden gain. Due to the small sample size and the preliminary nature of this study, we chose not to examine a mediational model. Previous studies of the sudden gain phenomenon have examined cognitive changes in sessions preceding the report of gains as one possible pathway through which symptom improvement occurs. Future research should more closely examine the process factors that precede sudden gains to further elucidate the mechanisms through which sudden gains occur.

The current study is among the first to examine sudden gains in a cognitive-behavioral treatment for PTSD and, thus, is significant in advancing forward both the literature on sudden gains in treatment as well as the literature on process of change in treatments for PTSD. Identifying sudden gains, as well as understanding the factors that may influence the emergence of sudden gains, is important to our overall knowledge of the process of change in psychotherapy. Ultimately, the occurrence of sudden gains is just one potential pattern of change in treatment (Hayes, Laurenceau, & Cardaciotto, 2008; Vittengl et al., 2005). Hayes et al. (2008) have suggested that examining the shape of change is critical to fully understanding the ways in which symptom improvements occur, as these changes may not be evident when examining simple pre- to post-treatment designs. Thus, future research should more explicitly examine the shape of change in CBT for PTSD. Overall, the study of process of change in psychotherapy is experiencing a reemergence, but very little research to date has examined change in treatment for PTSD from a process perspective (Foa et al., 2002; Nishith, Resick, & Griffin, 2002). A better understanding of how and when change occurs may lead to improvements in our current treatment approaches and methods for enhancing current interventions to be effective for a broader range of patients or those who are treatment resistant.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by a grant to Norah Feeny and Lori Zoellner from the Anxiety Disorders Association of America. We would like to thank the study psychiatrists Joshua McDavid, M.D. and Nora McNamara, M.D. In addition, we would like to acknowledge the contributions of study coordinators, therapists, and evaluators at each site: University of Washington: Frank Angelo, Bryan Cochran, Seiya Fukuda, Sally Moore, Shireen Rizvi, Angela Stewart, Anika Trancik, Stacy Shaw Welch, and Shree Vigil; Case Western Reserve University: Carla Arlien, Susan Baab, Alyssa Birge, Shoshana Kahana, Victoria Miller, Maryjean Starr, Sheridan Stull, and Kristen Walter.

Footnotes

Portions of this paper were previously presented at the 2007 Kent State University Applied Psychology Forum, “PTSD Across the Lifespan”.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA, Moulds ML, Guthrie RM, Dang ST, Nixon RDV. Imaginal exposure alone and imaginal exposure with cognitive restructuring in treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(4):706–712. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch AM, Kanter JW, Landes SJ, Kohlenberg RJ. Sudden gains and outcome: a broader temporal analysis of cognitive therapy for depression. Behavior Therapy. 2006;27(1):61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devilly GJ, Foa B. The investigation of exposure and cognitive therapy: comment on Tarrier et al. (1999) Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(1):114–116. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devilly GJ, Spence H. The relative efficacy and treatment distress of EMDR and a cognitive-behavior trauma treatment protocol in the amelioration of posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1999;13:131–157. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(98)00044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson KS, Shaw BF. Cognitive assessment with major depressive disorders. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1986;10(1):13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards DW, Yarvis RM, Mueller DP, Zingale HC, Wagman WJ. Test-taking and the stability of adjustment scales: can we assess patient deterioration? Evaluation Quarterly. 1978;2(2):275–291. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, Clark DM, Dumore E, Jaycox L, Meadows E, Foa EB. Predicting response to exposure treatment in PTSD: the role of mental defeat and alienation. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1998;11:457–471. doi: 10.1023/A:1024448511504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeny NC, Zoellner LA, Mavissakalian MR, Roy-Byrne PP. What would you choose? Sertraline or prolonged exposure in community and PTSD treatment-seeking women. Depression & Anxiety. 2009;26(8):724–731. doi: 10.1002/da.20588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders-patient edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2) New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Dancu CV, Hembree EA, Jaycox LH, Meadows EA, Street GP. A comparison of exposure therapy, stress inoculation training, and their combination for reducing posttraumatic stress disorder in female assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67(2):194–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree EA, Cahill SP, Rauch SAM, Riggs DS, Feeny NC, et al. Randomized trial of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder with and without cognitive restructuring: outcome at academic and community clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:953–964. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree EA, Dancu CV. Prolonged exposure (PE) manual – Revised version. University of Pennsylvania; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree EA, Rothbaum BO. Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: Emotional processing of traumatic experiences (Therapist Guide) New York: Oxford; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Riggs DS, Dancu CV, Rothbaum BO. Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1993;6:459–473. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Rothbaum BO, Riggs D, Murdock T. Treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder in rape victims: a comparison between cognitive-behavioral procedures and counseling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:715–723. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.5.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Zoellner LA, Feeny NC, Hembree EA, Alvarez-Conrad J. Does imaginal exposure exacerbate PTSD symptoms? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(4):1022–1028. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaynor ST, Weersing VR, Kolko DJ, Birmaher B, Heo J, Brent DA. The prevalence and impact of large sudden improvements during adolescent therapy for depression: a comparison across cognitive-behavioral, family, and supportive therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(2):386–393. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy GE, Cahill J, Stiles WB, Ispan C, Macaskill N, Barkham M. Sudden gains in cognitive therapy for depression: a replication and extension. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(1):59–67. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AM, Laurenceau J-P, Cardaciotto L. Methods for capturing the process of change. In: Nezu AM, Nezu CM, editors. Evidence-based outcome research. Oxford: University Press; 2008. pp. 335–358. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Schulz SM, Meuret AE, Moscovitch DA, Suvak M. Sudden gains during therapy of social phobia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(4):687–697. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: An assessment of the evidence. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Guilamo-Ramos J. Analysis of variance frameworks in clinical child and adolescent psychology: advanced issues and recommendations. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002a;31(1):278–294. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3102_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Guilamo-Ramos J. Analysis of variance frameworks in clinical child and adolescent psychology: issues and recommendations. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002b;31(1):130–146. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3101_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59(1):12–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaycox LH, Foa EB, Morral AR. Influence of emotional engagement and habituation on exposure therapy for PTSD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66(1):185–192. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MAR, Roberts JE, Ciesla JA. Sudden gains in cognitive behavioral treatment for depression: when do they occur and do they mater? Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller IW, Norman WH. Learned helplessness in humans: a review and attribution theory method. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86:93–119. [Google Scholar]

- Nishith P, Resick PA, Griffin MG. Pattern of change in prolonged exposure and cognitive-processing therapy for female rape victims with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(4):880–886. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Nishith P, Weaver TL, Astin MC, Feuer CA. A comparison of cognitive-processing therapy with prolonged exposure and a waiting condition for the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in female rape victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(4):867–879. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, Engel CC, Foa EB, Shea MT, Chow BK, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in women: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;297(8):820–830. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang TZ, DeRubeis RJ. Sudden gains and critical sessions in cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:894–904. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang TZ, DeRubeis RJ, Beberman R, Pham T. Cognitive changes, critical sessions, and sudden gains in cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(1):168–172. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang TZ, Luborsky L, Andrusyna T. Sudden gains in recovering from depression: are they also found in psychotherapies other than cognitive-behavioral therapy? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(2):444–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarrier N, Sommerfield C, Pilgrim H, Faragher B. Factors associated with outcome of cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000;38:191–202. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Thordarson DS, Maxfield L, Fedoroff IC, Lovell K, Ogrodniczuk J. Comparative efficacy, speed, and adverse effects of three PTSD treatments: exposure therapy, EMDR, and relaxation training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(2):330–338. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vittengl JR, Clark LA, Jarrett RB. Validity of sudden gains in acute phase treatment of depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(1):173–182. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Paykel ES. The depressed woman: A study of social relationships. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT. Rapid response to cognitive behavior therapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1999;6:289–292. [Google Scholar]