Children of immigrants—defined as children with at least one foreign-born parent—are a large and growing segment of the child population of the United States. Today more than one in five U.S. children has one or more foreign-born parents. Furthermore, since 1990 the children of immigrants have accounted for more than three-quarters of the growth in the size of the U.S. child population.1 Children of immigrants need not be immigrants themselves: most, in fact, are U.S. citizens by virtue of being born in the United States. In 2007, 87 percent of the children of immigrants were citizens; among the youngest of such children (those up to age five) fully 96 percent were citizens.2 Because of its size and growth, this new group of U.S. citizens warrants the attention of policy makers, researchers, and advocates who are seeking to improve the well-being of children in the United States.

Immigrant families face unique challenges as they adapt to their new country, yet they also bring with them many strengths, most notably high levels of marriage. U.S. immigration policy shapes immigrants’ family circumstances by selecting the types of immigrants permitted to come into and to remain in the United States, often on the basis of marriage and family relationships. But immigration policy does not consistently nurture these relationships: in some ways it can weaken them.

Furthermore, the nation’s acknowledged lack of a well-developed integration policy may exacerbate immigrants’ challenges and put their children’s outcomes at risk.

Children of immigrants have much in common as a result of their parents’ experiences with immigration and their status as relative newcomers. But their individual situations vary widely because of differences in their parents’ human and financial capital, legal status, social resources, and degree of assimilation, all of which are tied closely to their country or region of origin.

The majority of children of immigrants in the United States today are of Latin American origin, and more than 40 percent have parents from a single country—Mexico. Mexican immigrant families face challenges with respect to assimilation because of low parental education, poverty, and language barriers, and because a relatively high share of parents are unauthorized. In his article in this volume, Jeffrey Passel estimates that slightly more than half of Mexican children of immigrants are either unauthorized themselves or have unauthorized parents. The next largest group, about 20 percent of all children of immigrants, is those whose parents have migrated from Asia, most commonly from the Philippines, China, India, Vietnam, and Korea.3 Asian immigrant families vary widely by parental education and skills. Parents from China, India, Korea, and the Philippines tend to be highly educated, skilled professionals, while those from Vietnam and other Southeast Asian countries, such as Cambodia and Laos, generally have low education and skills.4 Although they are less dominant numerically, the children of black immigrants face special challenges because of their skin color. Most are of Caribbean origin, with parents coming from Jamaica, Haiti, and Trinidad and Tobago. Poverty and the dynamics of race in the United States combine to make some of these children especially vulnerable to negative outcomes.

In this article, we describe and discuss the implications of the living arrangements of children of immigrants, with an emphasis on three highly vulnerable groups: Mexican-origin children; Southeast Asian children (Vietnamese, Cambodian, Laotian); and black Caribbean-origin children. As noted, children in these groups face risk factors related to their parents’ low human capital, mode of entry into the United States (for example, as a refugee or unauthorized migrant), or status as a racial minority. We highlight family circumstances that may either counter or exacerbate the negative impacts of these risk factors. Although most children of immigrants live with their parents, the share varies by immigrant group and by generation. We also consider the living arrangements of youths—often foreign-born labor migrants who enter the United States alone as adolescents—who live in households with no parents. We conclude by discussing specific ways that U.S. immigration and integration policies shape immigrants’ family circumstances, and we suggest ways to alter policies to strengthen immigrant families.

[1]Why Children’s Living Arrangements Matter[end]

Children depend on their families, who are at the center of their everyday life. Although children’s families are not necessarily restricted to those who live in their households, the household is the site of daily activities and typically is the unit that provides most of their resources. Consequently, disparities in children’s outcomes are rooted in their divergent family circumstances.

Living arrangements may be particularly important in shaping the ways in which immigrants and their children are integrated into the social and economic life of the United States. Key features of living arrangements include parental marital and residential status as well as the presence or absence of grandparents, other relatives, or nonrelatives in the household. Many immigrant families are poor, face discrimination, and have limited access to resources because of their legal status, yet these problems may be offset for children to some extent by benefits associated with their household and family structures, such as living in a two-parent family. A significant finding in this regard is that children of immigrants are more likely to live in two-parent families than their co-ethnic counterparts who have native-born parents.5 Not only do two-parent families fare better economically than single-parent families, but also children living with both biological parents are less likely to experience a range of cognitive, emotional, and social problems that have long-term consequences for their well-being.6

Some children of immigrants live in extended families, though patterns of family extension vary widely by parental duration of residence in the United States. Although not specifically focused on children, some research shows that recent immigrants are more likely than more settled immigrants to live in extended families. Such arrangements more often involve lateral extension (for example, co-residence with a relative from a similar stage in the life course, such as a sibling) than vertical extension (co-residence of adults with their parents) because immigrants often leave older family members behind in the country of origin.7 Living in a laterally extended family may offer some benefits to individuals or families, though the choice of such a living arrangement may be driven more by the short-term instrumental needs of recent immigrants than by its potential long-term benefits. To the extent that extended family living arrangements are unstable or are an indirect indicator of hardship, they may not benefit children over the long run.

In what ways do children’s living arrangements influence their short-term and long-term well-being? Researchers conclude unequivocally that single-parent families have markedly higher child poverty rates than married-parent families, both for children as a whole and within different racial and ethnic groups. Cohabiting-couple families generally have child poverty rates between the two. Explanations for these differences include the number of potential adult earners in the household, the frequent failure of noncustodial parents to provide child support, and economies of scale for parents living together.8 Whether the link between family structure and family resources is causal is a matter of debate. Skeptics suggest that men and women with the greatest earning potential or resources are most likely to marry, while those with intermediate earning potential are most likely to cohabit and those with low earning potential are most likely to become single parents. Studies that make rigorous attempts to control for such self-selection into those three family types find evidence that family structure has causal effects on family income. From the point of view of children, however, the debate is largely academic. For them, what is important is that living with two married parents generally results in a higher standard of living and access to more opportunities than living in other arrangements.

The role of extended family living arrangements in child poverty is less clear, both because researchers have paid it less attention and because of analytical complexities related to different types of extension, assumptions about income pooling, and potential variation by race and ethnicity or by whether parents are native- or foreign-born. Nonetheless, by assuming that the incomes of all household members are pooled, one recent study showed that the economic standing of children living with single mothers (those with no spouse present) was substantially better when they were living in extended families than when no other adults were present in the household.9

Beyond their impact on children through economic resources, living arrangements may shape child outcomes through their influence on family stress, the availability of adult supervision and attention, and the quality of parenting.10 Burdened with both economic and time challenges, single-parent families tend to be less effective at parenting and to be subject to greater stress than two-parent families are. In addition, children in single-parent or cohabiting families must often undergo more family transitions than those in married-couple families. Extended-family living arrangements may compensate for some of the difficulties faced by single parents or other overburdened families. By providing child care or helping with household tasks, extended family members may ease family stress and ensure that children’s needs are met, thereby making child outcomes more positive. Some studies, however, indicate that parents who live with extended kin often are those least able to care for themselves and their children—and this may be the case in immigrant families. Complex living arrangements may be most common among recently arrived immigrants, who need help as they adapt to life in the United States. Extended family members may band together as a survival strategy, but such households may be unstable and provide few resources for children.11

[1]Living Arrangements of Children of Immigrants[end]

We combine five years of data (2005–09) from the Current Population Survey (CPS), a large nationally representative data set, to document the living arrangements of children under age eighteen. We emphasize two aspects of living arrangements: parental marital and residential status (married co-resident parents; cohabiting co-resident parents; single parent; no resident parents) and the presence of other adults in the household (grandparent; other relative; nonrelative). We focus first on differences in children’s living arrangements by parental nativity (whether parents are native- or foreign-born) for four racial and ethnic groups: Hispanics, Asians (including Pacific Islanders), non-Hispanic whites, and non-Hispanic blacks (see table 1).

Table 1.

Children’s Living Arrangements by Parental Nativity and Race/Ethnicity

| Parental marital and residential status |

Other adults in the household |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Married | Cohabit- ing |

Single | No resident parent |

Grand- parent |

Other relative |

Non- relative |

Number | |

| Children of immigrants |

55.9 | 19.7 | 21.2 | 3.3 | 8.8 | 19.9 | 3.6 | 69,819 |

| Hispanic | 52.5 | 19.6 | 24.0 | 3.8 | 8.3 | 23.0 | 4.6 | 40,393 |

| Asian | 64.8 | 20.2 | 12.4 | 2.6 | 12.8 | 16.8 | 2.0 | 11,521 |

| Black | 44.4 | 16.9 | 34.8 | 3.8 | 9.8 | 20.0 | 2.6 | 4,621 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 63.1 | 20.7 | 14.3 | 1.9 | 6.0 | 13.3 | 2.4 | 13,140 |

| Children of natives | 50.0 | 18.3 | 27.1 | 4.5 | 8.4 | 13.1 | 4.0 | 239,740 |

| Hispanic | 43.6 | 18.1 | 32.2 | 6.1 | 14.0 | 14.5 | 4.8 | 21,641 |

| Asian | 50.5 | 22.1 | 23.3 | 4.1 | 10.8 | 11.5 | 5.1 | 6,770 |

| Black | 23.9 | 11.4 | 55.3 | 9.4 | 14.7 | 15.8 | 4.3 | 33,018 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 58.0 | 20.0 | 19.0 | 3.0 | 5.9 | 12.2 | 3.7 | 174,618 |

Source: 2005-2009 March CPS

Sample: Children ages 0-17

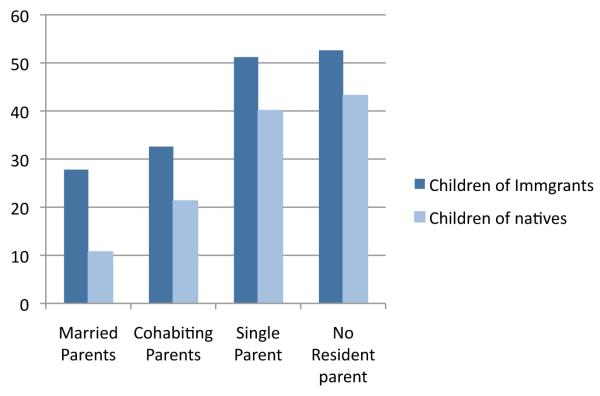

Despite differences across the broad groups, one pattern consistently emerges. Children of immigrants are considerably more likely to live with married parents than are children of natives (52 percent versus 44 percent for Hispanics; 65 percent versus 50 percent for Asians; 63 percent versus 58 percent for non-Hispanic whites; 44 percent versus 24 percent for non-Hispanic blacks). As illustrated in figure 1, the greater likelihood that children of natives will live with a single parent explains most of this difference, although such children are also slightly more likely to live in a household with no resident parents.

Figure 1.

Percent of Children Living with Single Parents

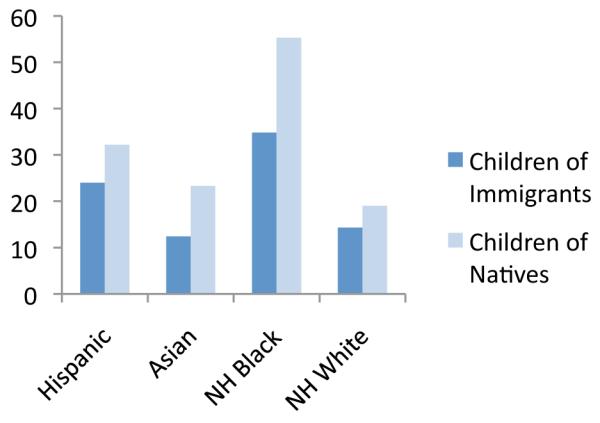

Differences by parental nativity in extended family living arrangements are less consistent across racial and ethnic groups. For example, among Hispanics and blacks, children of immigrants are less likely to live with grandparents than children of natives (8 percent versus 14 percent for Hispanics; 10 percent versus 15 percent for blacks). Among Asians and non-Hispanics, the share living with grandparents differs little by parental nativity. In contrast, as figure 2 shows, children of immigrants are much more likely to live with extended kin other than grandparents in all groups except non-Hispanic whites. Among Hispanics, for example, 23 percent of children of immigrants have other extended kin living in their households, compared with 14 percent of children of natives. On balance then, children of immigrants are more, but only slightly more, likely to live with either grandparents or other extended family members than children of natives, except among blacks (31 percent versus 29 percent among Hispanics, 19 percent versus 18 percent among non-Hispanic whites, and 30 percent versus 22 percent among Asians). Among blacks the division is equal at 30 percent.

Figure 2.

Percent of Children Living with Extended Kin other than Grandparents

Finer distinctions among immigrants’ children reveal somewhat different living arrangements by the child’s generational status (see table 2), which is based on the nativity of the child as well as his or her parents.12 Table 2 separates children with immigrant parents into three groups: the first generation, the second generation and the 2.5 generation. First-generation children were born outside the United States and had at least one foreign-born parent. Second-generation children were born in the United States and had two foreign-born parents. U.S.-born children with one foreign-born and one U.S.-born parent are the 2.5 generation. Finally, third-or-higher generation children were born in the United States and had two U.S.-born parents.

Table 2.

Children’s Living Arrangements by Race, Ethnicity, and Generational Status

| Parental marital and residential status |

Other adults in the household |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Married | Cohabit- ing |

Single parent |

No resident parent |

Grand- parent |

Other relative | Non- relative |

N | |

| Hispanic | ||||||||

| 1st generation | 51.6 | 17.7 | 23.2 | 7.5 | 5.4 | 29.6 | 6.2 | 7,099 |

| 2nd generation | 53.7 | 20.9 | 22.5 | 2.9 | 7.7 | 24.4 | 4.6 | 24,393 |

| 2.5 generation | 49.9 | 17.5 | 29.1 | 3.5 | 12.5 | 13.8 | 3.4 | 8,901 |

| 3rd+ generation | 43.6 | 18.1 | 32.2 | 6.1 | 14.0 | 14.5 | 4.8 | 21,641 |

| Asian | ||||||||

| 1st generation | 62.9 | 19.7 | 12.7 | 4.7 | 7.7 | 21.2 | 3.0 | 2,595 |

| 2nd generation | 66.5 | 20.2 | 11.4 | 1.9 | 14.9 | 16.3 | 1.5 | 6,709 |

| 2.5 generation | 60.8 | 20.7 | 16.0 | 2.5 | 11.8 | 12.1 | 2.7 | 2,217 |

| 3rd+ generation | 50.5 | 22.1 | 23.3 | 4.1 | 10.8 | 11.5 | 5.1 | 6,770 |

| Black | ||||||||

| 1st generation | 44.8 | 14.2 | 34.7 | 6.2 | 5.8 | 31.2 | 1.6 | 954 |

| 2nd generation | 48.6 | 18.0 | 30.6 | 2.8 | 10.4 | 19.6 | 2.2 | 2,250 |

| 2.5 generation | 36.6 | 16.8 | 42.6 | 4.0 | 11.2 | 13.5 | 3.9 | 1,417 |

| 3rd+ generation | 23.9 | 11.4 | 55.3 | 9.4 | 14.7 | 15.8 | 4.3 | 33,018 |

| Non-Hispanic white | ||||||||

| 1st generation | 63.7 | 19.2 | 13.1 | 4.0 | 3.1 | 19.1 | 3.1 | 2,281 |

| 2nd generation | 65.1 | 21.6 | 12.1 | 1.2 | 7.7 | 14.8 | 1.6 | 3,979 |

| 2.5 generation | 61.6 | 20.6 | 16.2 | 1.7 | 5.9 | 10.1 | 2.6 | 6,880 |

| 3rd+ generation | 58.0 | 20.0 | 19.0 | 3.0 | 5.9 | 12.2 | 3.7 | 174,618 |

Source: 2005-2009 March CPS

Sample: Children ages 0-17

In general, the share of children living with married parents declines with each generation in the United States, but first-generation children are slightly less likely to live with married parents than are second-generation children. Living with a married parent who has an absent spouse (not shown) is also particularly prevalent among first-generation children. In addition, such children are distinctive in being more likely than other children of immigrants to live in households with no resident parent. These various arrangements suggest that newly arrived immigrant families may encounter complications that reduce children’s chances of living with both parents and lead some children to live in households that provide no parental supervision. However, with the exception of first-generation Asian children (who make up 22.5 percent of Asian children of immigrants), first-generation children account for no more than 20 percent of children of immigrants in the major racial and ethnic groups.

Important distinctions also exist by country (or region) of origin within each broad racial or ethnic group. Children in the three specific groups that we highlight (Mexicans, Southeast Asians, and Caribbean blacks) share common disadvantages that stem from their parents’ relatively low education and income. Because of the histories and broader contexts of immigration from their countries of origin, however, the groups differ in parental legal status (for example, unauthorized versus authorized), parental work patterns, the types of communities in which they live, and their reception by the native-born population. We thus discuss the family situations and living arrangements of each group separately.

[2]Children in Mexican Immigrant Families[end]

Given the volume of immigration from Mexico, the predominance of children of immigrants among Mexican-origin children, and the comparative youth of the Mexican-origin population, children of Mexican immigrants are of special importance in shaping the future of the U.S. population. According to Census Bureau projections, the Hispanic population will account for nearly one-quarter of the nation’s total population by 2040. Jennifer Glick and Jennifer Van Hook estimate that the Mexican-origin population alone will account for 15–17 percent of the U.S. population by then.13 It is therefore important to understand the circumstances that may influence the future outcomes of today’s Mexican-origin children.

The major challenge facing Mexican immigrants and their children is their limited opportunity for economic integration, owing in large part to their low education, skills, and financial resources. On average, foreign-born Mexicans have completed eight and a half years of education, compared with about twelve years for native-born Mexicans and more than thirteen years for native-born whites.14 Together with their limited English proficiency and frequently unauthorized legal status, the low education of Mexican immigrant parents severely limits their opportunities for stable, well-paid employment.15 With the premium for education and skills especially high in today’s high-tech economy, it is no surprise that about 34 percent of Mexican children of immigrants are poor, compared with 24 percent of Mexican children of natives.16 For these reasons, many scholars and policy analysts are concerned that the Mexican-origin population may remain socially marginalized and economically disadvantaged well into the future.

For children, living in poverty increases the risk of negative outcomes, including health and developmental problems, poor academic performance, low completed education, and low earnings in adulthood. Because poverty and family structure are linked, poor children often face not only resource deficits but also other risk factors associated with single parenthood, such as high family stress, inadequate supervision, multiple family transitions, and frequent residential moves. For Mexican-origin children, however, poverty and family structure vary in a less straightforward manner. Although Mexican children of immigrants have a higher poverty rate than Mexican children of natives, they are more likely to live in two-parent families. As shown in the top panel of table 3, 56 percent of Mexican children of immigrants live with two married parents, compared with 45 percent of Mexican children of natives. When cohabitating parents are included, fully 75 percent of Mexican children of immigrants live in a two-parent family, compared with 63 percent of Mexican children of natives. The favorable family structures of children with foreign-born parents may reduce some of the risk factors typically associated with poverty.

Table 3.

Children’s Living Arrangements by Parental Nativity for Selected National-Origin Groups

| Parental marital and residential status |

Other adults in household |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Married | Cohabiting | Single parent |

No resident parent |

Grand- parent |

Other relative |

Non- relative |

N | |

| Mexican children of immigrants |

55.6 | 20.1 | 20.6 | 3.6 | 7.8 | 23.7 | 4.6 | 27,558 |

| Mexican children of natives |

45.2 | 17.7 | 30.9 | 6.2 | 14.6 | 14.2 | 4.8 | 14,806 |

| SE Asian children of immigrants |

58.4 | 20.2 | 16.1 | 5.2 | 13.3 | 23.6 | 2.3 | 1,238 |

| Cambodian | 60.0 | 11.2 | 24.1 | 4.6 | 23.3 | 23.8 | 4.1 | 278 |

| Laotian | 53.0 | 25.4 | 19.1 | 2.5 | 7.0 | 39.7 | 0.4 | 224 |

| Vietnamese | 59.2 | 21.9 | 12.8 | 6.1 | 11.5 | 19.7 | 2.2 | 736 |

| SE Asian children of natives |

49.2 | 38.9 | 11.8 | 0.0 | 10.5 | 6.4 | 1.3 | 126 |

| Black children of immigrants |

44.4 | 16.9 | 34.8 | 3.8 | 9.8 | 20.0 | 2.6 | 4,621 |

| Caribbean | 33.1 | 18.9 | 42.6 | 5.4 | 15.2 | 24.9 | 2.2 | 1,238 |

| African | 55.5 | 14.6 | 27.8 | 2.2 | 5.9 | 18.2 | 2.1 | 1,512 |

| Other black | 45.1 | 17.1 | 34.0 | 3.8 | 8.4 | 17.6 | 3.2 | 1,871 |

| Black children of natives |

23.9 | 11.4 | 55.3 | 9.4 | 14.7 | 15.8 | 4.3 | 33,018 |

Source: 2005-2009 March CPS

Sample: Children ages 0-17

Despite that initial advantage, however, Mexican-origin children increasingly face challenges related to their household and family structure as their families become more settled. In particular, the favorable two-parent family structure becomes much less common among native-born children in both the 2.5 and third generations (see table 4). That pattern suggests that as Mexican families spend more time in the United States (as indexed by generation), the strong parental bonds that protect Mexican-origin children erode. Over time, Mexican families may be more and more subject to the same forces that are increasing single parenthood among American families generally.

Table 4.

Children’s Living Arrangements by Generational Status for Selected National Origin Groups

| Parental marital and residential status |

Other adults in the household |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Married | Cohabit- ing |

Single parent |

No resident parent |

Grand- parent |

Other relative |

Non- relative |

N | |

| Mexican | ||||||||

| 1st generation | 55.3 | 18.4 | 18.4 | 7.9 | 4.4 | 32.5 | 6.4 | 4,455 |

| 2nd generation | 57.0 | 21.5 | 19.0 | 2.6 | 6.9 | 24.8 | 4.5 | 17,357 |

| 2.5 generation | 51.9 | 17.1 | 27.3 | 3.6 | 13.1 | 13.8 | 3.6 | 5,746 |

| 3rd+ generation | 45.2 | 17.7 | 30.9 | 6.2 | 14.6 | 14.2 | 4.8 | 14,806 |

| SE-Asian1 | ||||||||

| 1st generation | 59.9 | 20.2 | 13.5 | 6.4 | 7.9 | 28.7 | 5.7 | 213 |

| 2nd generation | 59.8 | 20.6 | 15.4 | 4.1 | 14.9 | 25.5 | 1.1 | 793 |

| 2.5 generation | 51.6 | 18.7 | 21.4 | 8.4 | 12.7 | 10.6 | 3.8 | 232 |

| Black Caribbean1 | ||||||||

| 1st generation | 29.1 | 18.6 | 42.3 | 10.0 | 13.5 | 43.6 | 1.3 | 177 |

| 2nd generation | 35.2 | 22.1 | 38.2 | 4.6 | 17.1 | 24.2 | 1.9 | 697 |

| 2.5 generation | 30.8 | 12.6 | 51.9 | 4.7 | 11.9 | 16.7 | 3.4 | 364 |

Source: 2005-2009 March CPS

Sample: Children ages birth to seventeen

Comparable information on the 3rd+ generation not available due to data limitations

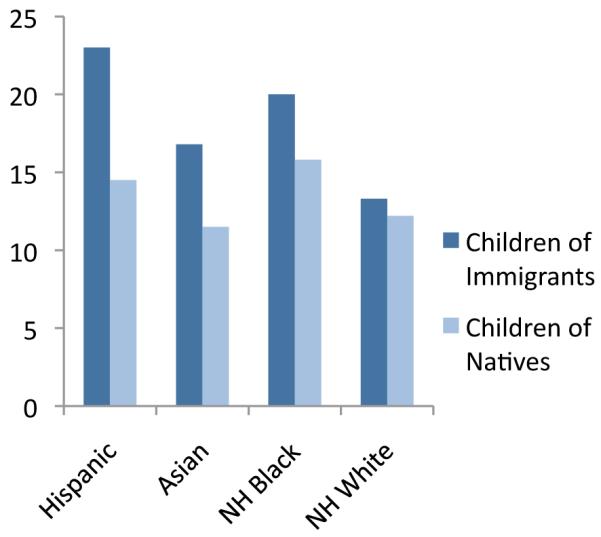

Even though Mexican children of natives are more likely to live in single-parent families than Mexican children of immigrants, they have a lower rate of poverty. That finding, however, does not mean that family structure is inconsequential. Poverty rates would be even lower for children of natives if not for their disadvantaged family structure. As illustrated in figure 3, children of natives are less likely to live in poverty regardless of family type. For example, in married-couple families, 28 percent of children of immigrants are poor, compared with 11 percent of children of natives. The explanation for this difference, in large part, is that foreign-born Mexican parents have lower human capital and earnings than do their native-born counterparts. In addition, although employment rates of foreign- and native-born Mexican men are roughly comparable, the employment rate of foreign-born Mexican women is substantially lower (56 percent) than those of their native-born (76 percent) and white counterparts (80 percent).17 Similarly, in single-parent Mexican families, children of immigrants have higher poverty rates (51 percent) than children of natives (40 percent). Still, children of natives are four times more likely to be poor if they live in a single-parent than in a married-couple family. Thus, the higher prevalence of single-parent families among Mexican children of natives suggests that economic progress is being eroded by shifts in family structure.

Figure 3.

Percentage of Mexican Children in Poverty by Parental Marital Status and Residence

Mexican immigrant families also face special challenges associated with migration itself. Mexican immigrants are predominantly labor migrants, sojourners who come to the United States temporarily to work during their early adult years (as early as late adolescence through their mid-thirties). At least initially, they maintain strong ties with their households and families in Mexico, sending remittances and visiting or even eventually returning home. Others remain permanently in the United States even though many are unauthorized. Not surprisingly these migration patterns shape children’s living arrangements. For example, the circular nature of Mexican labor migration appears to contribute to the formation of highly unstable households made up of both extended kin and non-kin. In addressing the question of why Mexican immigrants are more likely than U.S.-born Mexicans to live in extended families, Van Hook and Glick recently contrasted an explanation focused on cultural norms brought from Mexico with an explanation that stresses the use of extended family co-residence as survival strategy.18 They showed that recent immigrants live in household structures very different from those in Mexico, with considerably more lateral extension (for example, living with adult siblings) and co-residence with nonrelatives. As Mexican immigrants live longer in the United States, they are less likely to live in either of those arrangements and less likely to live with extended kin altogether. The study also found that extended family arrangements are highly unstable, with considerable turnover of household members. Although Van Hook and Glick’s research was not based on families with children, it suggests that living in an extended family may temporarily benefit Mexican children of recent immigrants by helping their parents cope with the many challenges they face when they first arrive in the United States. But such an arrangement is unlikely to be stable or to contribute to children’s long-term well-being.

One particularly troubling difficulty posed by migration is that it can separate children from their parents, either because one family member migrates first and later brings over other family members (stage migration) or because a parent is deported or deterred from the dangerous border crossing. Ethnographic accounts detail “transnational family” patterns among labor migrants from Central America and Mexico,19 whereby one or more family members (often a parent) will migrate for work leaving other family members behind. Children born in the country of origin may be left there in the care of a single parent or relative even as new U.S.-born siblings are raised in the United States, so children in both countries are living apart from one or both parents and siblings. Little is known about how many children live in these types of families, but the number may be substantial. In the United States, although most Mexican children of immigrants live with two parents, 21 percent live with only one parent. Of these “single” parents, 17 percent are married but live apart from their spouse. Although the whereabouts of these parents is unknown, they may be living in Mexico. In a study of an immigrant-sending community in central Mexico, Joanna Dreby found that 28 percent of children had one or both parents living in the United States.20 Clearly further study is warranted to learn more about how long children of immigrants remain separated from their immediate family members and how that separation affects their well-being and future integration into U.S. society. Because of the limits of cross-sectional data for studying family separations and instability, it will be necessary to build bi-national data sets that follow children and parents over time to advance research in this area.

Migration also separates children from their parents when foreign-born adolescents travel to the United States alone in search of work. Among foreign-born Mexicans aged twelve to seventeen, fully 12 percent live in U.S. households with no resident parent.21 These youths are highly likely to live with relatives other than parents or grandparents (62 percent), such as siblings, cousins, or aunts and uncles, or in households that do not include family members (27 percent). Because they are rarely enrolled in school and are subject to limited supervision, youth living apart from their parents are at high risk of negative short-term outcomes (such as unmet health care needs or drug and alcohol abuse) and negative long-term outcomes (such as limited education and skill development).22 Yet few studies provide information on the circumstances of Mexican children who live apart from their parents. Researchers know little about the stability of their living arrangements or about whether living with extended kin is protective for these vulnerable youth.

Yet another risk factor for Mexican children of immigrants is the mixed legal status of their family members. Almost half of Mexican children of immigrants live in families where the children are citizens and the parents are not. (The comparable share for children of Asian immigrants is 13 percent; for children of European immigrants, 14 percent).23 Beyond lacking U.S. citizenship, many of the parents in Mexican mixed-status families are unauthorized, especially those who have immigrated relatively recently. Using data from 2004, Jeffrey Passel showed that the majority of Mexico-born U.S. residents who entered the country after 1990 were unauthorized, with figures ranging from 70 percent during 1990–94 to 85 percent during 2000–04.24 Although the citizen children of unauthorized parents are on an equal legal footing with all citizen children, their parents’ unauthorized status affects them adversely in many ways. Unauthorized parents typically work in unstable, low-wage jobs that do not carry health benefits. Thus, Mexican children of unauthorized parents are more likely to be poor than other Mexican children of immigrants. In addition, as Passel notes in his article in this volume, unauthorized parents often fail to take advantage of public benefit programs for which their children qualify, because they fear deportation. These hardships may be intensified by unstable living arrangements and periods of separation from one or both parents. Researchers as yet know little about the family situations of children with unauthorized parents and should make that topic a high priority for future work.

The lives of children in mixed-status families would become especially difficult if U.S. citizenship laws changed. One particularly disturbing recent development has been the mounting criticisms of birthright citizenship, which grants citizenship to all persons born in the United States as stated in the 14th amendment of the U.S. Constitution. If the United States denied citizenship to the U.S.-born children of unauthorized immigrants, as some have advocated, this could jeopardize child well-being and Mexicans’ prospects for social integration. Jennifer Van Hook and Michael Fix projected the size of the unauthorized population if all children with an unauthorized mother were denied legal status.25 Their mid-level estimates suggest that within four decades, the unauthorized population would be 72% higher than the number under current law, and 15% of the unauthorized would be third-or-higher generation Americans. Because infants would be the first to lose U.S. citizenship, children would be disproportionately affected. By 2050, the share of all U.S. children who would be unauthorized would more than double, mostly likely exceeding 5%. In all likelihood, most of these children would be Hispanic or Mexican origin.

[2]Children in Southeast Asian Immigrant and Refugee Families[end]

Refugees come to the United States under very different circumstances than do Mexican labor migrants. Many flee their countries of origin from stressful and sometimes dangerous situations without advance planning and may be ill-prepared for life in the United States. Unlike labor migrants, however, they and their children are legally resident in the United States and receive settlement assistance from the federal government.

Refugees admitted to the United States in recent decades have increasingly come from diverse countries of origin.26 Yet much of what scholars know about the living arrangements of children in refugee families comes from studies of the children of immigrants from Southeast Asia and Indochina— largely because Southeast Asian refugees have been in residence in the United States longer than most of their contemporary counterparts. The three major Southeast Asian refugee groups in the United States are the Vietnamese (whose arrival between 1970 and 2000 resulted in a tenfold increase in the Asian foreign-born population), Cambodians, and Laotians.27 Refugees from Laos include former Hmong guerillas, a group that fought on behalf of the U.S. government during the Vietnam War, as well as their descendants. In addition to their larger numbers, Vietnamese refugees differ from their counterparts from Cambodia and Laos in other important ways. For example, although children were over-represented in refugee movements from all three countries, Cambodian and Laotian refugee groups brought with them more children than did the earlier Vietnamese groups.28 Similarly, because Vietnamese refugee families fled to the United States earlier, their families have a greater share of second-generation children.29

Many studies of Southeast Asian immigrants base their discussion of living arrangements on the circumstances of the refugees’ flight from conflicts and the ensuing implications for both their mode of entry and their situation after arrival. The refugee experience poses a range of challenges for Southeast Asian children of immigrants through its influence on household characteristics. Parental social and economic attributes, for example, differ for children in refugee and non-refugee families, with other Asian immigrants tending to be more highly skilled and better educated than Southeast Asian refugees.30 According to Rubén Rumbaut’s study of children in San Diego, children in Southeast Asian refugee groups were less likely than other children to have parents who graduated from college. They were also the least likely to live in families that owned their own home.31 Human capital also varies among the refugee groups, with families from Cambodia and Laos more disadvantaged than those from Vietnam. Rumbaut finds that parental schooling and home ownership rates are much lower among Cambodians and Laotians than among the Vietnamese. Other studies find parental human capital lowest among the Laotian Hmong refugees, many of whom were poor rural farmers before migrating to the United States.32

Other characteristics of Southeast Asian refugee parents depend on when they arrived in the United States. Earlier refugee cohorts from Vietnam, for example, had more schooling when they arrived than did more recent arrivals.33 That disparity has important implications for child well-being among the Vietnamese because recent Southeast Asian refugee cohorts arrive with a greater number of children than earlier cohorts.34

The unique context of Southeast Asian refugee immigration also has implications for the family characteristics of the children, some of which pose significant challenges. First, a relatively high share of Southeast Asian children of immigrants lives in nontraditional family structures because of the death of family members, as a result either of war or of the hardships of life in refugee camps.35 Cambodian refugee households suffered the worst effects. As observed by Nga Nguy, many Cambodian immigrants had spouses who were killed or simply taken away by Khmer Rouge guerillas before they arrived in the United States.36 More than a third of all Cambodian refugees are estimated to have lost either a family member or a close friend.37

Family deaths naturally diminished the likelihood that children would live in two-parent families. Rumbaut, for example, finds that Cambodian youths are less likely than other immigrant youths to live with two parents. Studies of Hmong and other Laotian youths report similar findings. According to the Youth Development Study in Minnesota, most Hmong youths live in households missing either one or two parents because they died before migrating; about two-thirds live in families without a biological father.38 A significant number of Laotian immigrants to the United States also arrived as single parents having lost their partners to conflict.39

Consequently Southeast Asian children of immigrants are more likely to live in single-parent families than their Asian counterparts overall (16 percent versus 12 percent for all Asians). They are, however, with the exception of Cambodian-origin children, less likely to live with a single parent than either Mexican or Caribbean black children of immigrants. As table 3 shows, about 16 percent of Southeast Asian children of immigrants live in single-parent families (24 percent for Cambodians), compared with 21 percent of Mexican and 43 percent of Caribbean black children of immigrants. Thus, although the significance of pre-migration parental mortality for family structure may have declined, the high prevalence of single-parent families among Southeast Asian immigrants suggests that their family structure is also a product of other social determinants.

Family structure among Southeast Asian youths is determined by the absence not only of Southeast Asian fathers but also of American fathers of children born outside the United States. For example, Jeremy Hein maintains that a significant number of first-generation Vietnamese and Cambodian children who arrived in the United States with only their mothers and siblings had fathers who were American soldiers.40 Because many of these fathers also died during the wars in their respective countries, only a few of their children were reunited with their fathers after arriving in the United States.

As another consequence of their war experiences, Cambodian immigrants created complex networks of extended-family relationships that foster family cohesion across fragmented households. Hein finds that these networks involve attaching isolated individuals and fragmented families to other families through friendship, fictive kinship, or marriage. It is not unusual for these households to contain multiple generations, as well as married siblings or friends who are unrelated to other household members but nonetheless considered part of the family. Among Vietnamese refugees, inter-state mobility after arrival in the United States also complicates household structures. According to Nazli Kibria, many Vietnamese refugees migrate from one U.S. state to another to live with friends and other kin, thus creating new households that allow them to pool resources to combat poverty.41 Hmong household relationships too are often highly complex. Estimates from the 2000 census indicate that the Hmong are more likely than the rest of the U.S. population to live in households that include grandchildren, parents, siblings, and other kin members.42

Table 3 shows that the likelihood of living with a grandparent varies considerably by country of origin among Southeast Asian children of immigrants, from a high of 23 percent for Cambodians to a low of 7 percent for Laotians. All Southeast Asian children, however, are highly likely to live in households with relatives other than grandparents. Combining grandparents and other relatives, fully 37 percent live in households with relatives other than their parents. Almost half of Cambodian children live in complex family households. Southeast Asian refugees are, therefore, highly likely to have siblings, other relatives, and nonrelatives within their households who help provide childcare and with whom they share resources.43 Nonetheless, the share of other relatives in their households is roughly comparable to that of Caribbean black children of immigrants and only somewhat higher than that of Mexican children of immigrants.

Southeast Asian children also have larger families than do other immigrant groups. Among Southeast Asians, Hmong families are the largest and also the youngest.44 Southeast Asian families are large for several reasons.45 The first is their fertility, which exceeds that of all other immigrants except Mexicans. The second is their desire to retain the characteristics of traditional Southeast Asian families after arriving in the United States. For example, Hmong immigrant families, like families in their country of origin, are formed early in the life course because of early marriage among females and the importance of childbearing.46 As many as half of Hmong girls in California are estimated to marry before age seventeen.47 Zha Blong Xiong and Arunya Tuicomepee report that the Hmong have higher teen birth rates than blacks, Latinos, and other Asians.48 Not surprisingly, their analysis also shows that families consisting of married couples with children are more prevalent among the Hmong than among the U.S. population overall, again reflecting the importance of early marriage and childbearing among Hmong adolescents.

Studies about the possible effects of Southeast Asian childbearing patterns on socioeconomic outcomes report mixed findings. For example, the high fertility of Southeast Asians has been linked with an increased risk of welfare dependency.49 And findings show that large family size is associated with low labor force participation among females. Yet according to many studies, the link between early childbearing and low educational attainment is smaller among Hmong teenage mothers than among their non-Hmong counterparts.50

Southeast Asian youths who immigrate to the United States by themselves are especially vulnerable, particularly when they live in households with no parents present. As table 3 shows, 5.2 percent of Southeast Asian children (and 6.1 percent of Vietnamese children) live without parents. Some of these unaccompanied youths arrive in the United States either as orphans or having been sent by parents to establish initial ties to facilitate future immigration through family reunification preferences.51 Many of these children must make significant life-course transitions, such as their first employment experience, without their parents.52 Despite such known vulnerabilities, however, only a few studies have systematically examined the living arrangements of unaccompanied refugee youths from Southeast Asia. A 1988 study found that many resettled within new U.S. families after arriving in the United States.53 Similar patterns have been found in more recent refugee groups.54

Research on the implications of these living arrangements for children’s outcomes focuses on unaccompanied Southeast Asian refugee youths in American foster families—finding, for example, that they have lower grades than their counterparts in ethnic foster families.55 Unaccompanied siblings within the same foster family face other difficulties. For example, Mary Ann Bromley found that youths whose oldest sibling was their “household head” before immigrating to the United States have trouble adjusting when their sibling is replaced as household head by their foster father.56 She also maintains that unaccompanied refugee youths in American families are likely to feel isolated and have symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, although these feelings generally disappear as their stay in the United States lengthens. When they transition to independent living, older unaccompanied youths in foster care face many practical difficulties, such as taking care of themselves and finding employment to meet their expenses.57

[2]Children in Black Caribbean Families[end]

As U.S. immigration flows have become more diverse, the black foreign-born population has grown larger. Now one of the nation’s fastest-growing immigrant groups, black immigrants, particularly those from the Caribbean, have drawn attention from scholars and social commentators for their economic success despite their disadvantaged racial origins.58 Nevertheless, research and policy attention to the living arrangements of their children is generally limited—and at odds with the “success story” often told about black immigrants. Recent studies suggest that the children of black immigrants are more likely than other children to face several types of familial vulnerabilities that have significant implications for their well-being. For example, among all children of immigrants, the children of black immigrants are the least likely to live with two married parents; they are highly likely to live in single-parent families or with grandparents rather than parents.59 In addition, they live in less favorable familial circumstances as they assimilate. As their generational status increases, they are more likely than children in other immigrant groups to continue to live in socioeconomically vulnerable household contexts, such as in single-mother households.

Most studies on the living arrangements of children of black immigrants focus on the largest such group—Caribbean immigrants—in part because they arrived earlier than black immigrants from other regions.60 Recent estimates indicate that more than half of all black children of immigrants have Caribbean-origin parents.61 We thus confine our review of the research to the children of black Caribbean immigrants.

Household living arrangements among black Caribbean immigrants are influenced by gender disparities in Caribbean immigration to the United States. Specifically, there are more female than male Caribbean immigrants and this has influenced the sex composition of adults in immigrant families.62 Caribbean-origin children of immigrants, especially those from the English-speaking Caribbean, are more likely to live in female-headed families than are children in many other immigrant groups.63 Some scholars suggest that the high prevalence of single-parent families among Caribbean immigrants also reflects the influence of pre-migration familial norms unique to the Caribbean region. The higher prevalence of female-headed households among Caribbean than non-Caribbean immigrants in South Florida, for example, reflects the higher prevalence of such families in Caribbean countries of origin.64 At the same time, female-headed households among Caribbean immigrants sometimes result from shifts in who is designated as household head. Such shifts may arise from the post-immigration economic influence of women in families accompanied by husbands or fathers during their initial migration to the United States.65

Table 3 compares the family structures of black children of immigrants from the Caribbean and from Africa. Caribbean-origin youth are considerably less likely to live with married parents (33 percent) than their counterparts whose parents migrated from Africa (55 percent). They are more likely than any other group shown in table 3 except black children of native-born Americans to live in a single-parent family (43 percent compared with 55 percent).

The prevalence of single-parent families among Caribbean immigrants varies by group and by state of residence. Sherri Grasmuck and Ramon Grosfoguel maintain, for example, that in New York, Dominican immigrants have more female-headed households than do Jamaicans or Haitians.66 But in both California and Florida, Rumbaut finds that the children of Jamaican and Haitian immigrants are the most likely to live in father-absent families.67 Regardless of place of residence, however, Caribbean children in single-parent families fare worse than their counterparts in two-parent families. Among Caribbean immigrants in Southern Florida, for example, children in single-parent families were found to have lower GPAs, as well as lower math and reading scores, than those in two-parent families.68 In addition, Mary Waters’ work among Caribbean youths in New York indicates that children in female-headed single-parent families generally have working mothers whose ability to supervise them is constrained by their limited access to networks of extended family members and friends.69

Among Caribbean immigrants, single-parent households are sometimes temporary family arrangements associated with sequential patterns of family migration in which females initially migrate with their children to be followed by their spouses.70 Indeed, our analysis of the CPS data shows that among all black children of immigrants living in single-parent households, roughly one in five has a married parent living elsewhere. Stage migration patterns may thus separate members of black immigrant families, much as they do Mexican immigrant families. Even when the “married-but-apart” group is added to the “married” category, however, the resulting share is substantially lower than that among other children of immigrants. Moreover, evidence suggests that a large share of the U.S.-born children of Caribbean immigrants lives in female-headed single-parent families. Waters, for example, notes a high prevalence of female single-parent households among second-generation black Caribbean children of immigrants,71 suggesting that the high prevalence of single-parent living arrangements among Caribbean families cannot be explained simply by sequential migration patterns and traditional or home country familial norms. The persistence of single-parent families across generations suggests post-immigration influences that are yet to be examined systematically.

Extended family members who remain in the Caribbean generally play a crucial role in the residential patterns of these children. Parents sometimes send children back to their country of origin to keep them from being socialized negatively by their peers or to influence their developmental trajectories. Once back in the Caribbean, children usually live in nonparent households headed by extended-family members.72 Likewise, when limited resources prevent the entire family from immigrating, siblings left behind live with extended family members.73 These children, who are generally very young, are raised in nonparent households until their early teenage years, when they are reunited with their parents in the United States.74 Post-migration changes in households also have social implications for the integration of newly arriving Caribbean teenagers into the family. Extended separation between parents and their children may be especially stressful for children whose parents divorce or remarry, or both, in their absence, especially when children have to live with new step-parents.75 Consequently the reunification of Caribbean children and their immigrant parents in the United States after long separation is often associated with elevated parent-child conflict.76

[1]Immigration and Immigrant Integration Policy and Child Well-being[end]

Immigration policy shapes the laws and practices that affect the national origins, numbers, and characteristics of those who come to live in the United States, including admissions, refugee, and border policies. Immigrant integration policy involves the laws and practices concerning the settlement and incorporation of immigrants and their children. Despite the wide diversity of the challenges that face immigrants and their families because of their unique patterns of immigration and integration, it is possible to identify some ways to alter U.S. immigration and integration policies to help sustain the pre-existing strengths of a broad range of immigrant families.

[2]Immigration Policy[end]

Since 1965, U.S. immigration policy has been guided by principles that promote the reunification of immigrants with their children and other relatives living abroad. In practice, however, policy often violates these principles. Sometimes, it serves to separate rather than support immigrant families. One issue requiring policy makers’ attention is that legal immigrants to the United States must often wait several years before their spouses and children may legally join them. Relatives of U.S. citizens and legal permanent residents (LPRs) are permitted to immigrate to the United States under the “family reunification” provisions of the Immigration and Nationality Act. However, long backlogs for some family reunification admission categories, including the spouse and minor children of legal permanent residents, contribute to extended periods of family separation. Backlogs are partially a consequence of inadequate staffing. Doris Meissner and Donald Kerwin argue that the office of Citizenship and Immigration Services (CIS) is understaffed and ill-prepared for the inevitable periodic surges in applications.77 They acknowledge that serious efforts have been made during the past decade to reduce backlogs, but contend that some of the apparent successes have come about by redefining the backlog rather than reducing the waiting time for applicants. According to Meissner and Kerwin, reductions in the backlog (made possible by surges in funding and staffing) tend to be offset by increases in the number of applications as word gets out that wait times have become shorter.

Backlogs are also attributable to the mismatch between admission policy and the demand for visas. Under the family reunification criteria, immediate relatives of U.S. citizens and legal immigrants are eligible for admission to the United States. Current admission criteria grant unlimited numbers of visas to minor children and spouses of U.S. citizens, meaning that they may be admitted as soon as their case has been approved. But the spouses and minor children of legal permanent residents must usually wait several years after their application is approved before they are issued an immigration visa, because the number of visas available to minor children and spouses of LPRs is limited by numerical annual caps that are applied equally to all countries regardless of demand for immigrant visas. The caps, devised to prevent single countries from dominating immigration flows, place unrealistic restrictions on countries with large numbers of potential immigrants to the United States, such as Mexico, China, India, and the Philippines. In 2006, an LPR sponsoring a spouse or a minor child had to wait about six years between applying and being admitted, and the wait has been estimated to be much longer for Mexicans.78 Immigrants qualifying for other visa categories, such as unmarried adult children, often have an even longer wait (for example, fifteen years for Mexicans).

During the waiting period between application and admission, prospective immigrants must remain outside the United States. If authorities discover that they have lived in the United States illegally for more than one year, admission is denied and they are not allowed to immigrate for ten more years.79 Meanwhile, young children living outside the United States spend critical childhood years separated from their immigrant parent(s) and sometimes even “age out” of the admission category for which they were initially eligible (because they are no longer minor children). Thus, children who turn twenty-two while waiting for admission must find alternative legal pathways—and may endure even longer waiting periods—if they wish to join their parents in the United States. If children are finally reunited with their parents, interpersonal problems may arise as these families negotiate their new lives together and older children born outside the United States must contend with new U.S.-born siblings.

Long waits for legal admission may also encourage illegal immigration. As the Independent Task Force on Immigration and America’s Future argues, “The system’s multiple shortcomings have led to a loss of integrity in legal immigration processes. These shortcomings contribute to unauthorized migration when families choose illegal immigration rather than waiting unreasonable periods for legal entry.”80 Guillermina Jasso and her colleagues find that about half of LPRs are not new arrivals but had been living (most illegally) in the United States.81 In 2005 (the last year estimates were made available), the backlog included 3.1 million approved LPR applications. If half of these cases were living illegally in the United States in 2005, that would imply that about 14 percent of the estimated 10.5 million unauthorized residents at that time had been approved for legal admission but remained unauthorized because of the long waiting lists.82

Reducing immigration backlogs could improve children’s lives. At the very least, adequate staffing could reduce waiting times within existing immigration law. Some observers argue further that minor children and spouses of LPRs should be treated like the minor children and spouses of citizens and be admitted immediately without a wait. Still others have proposed legislation to reduce the backlog by allowing LPRs, like citizens, to bring in their spouses and children, but not their parents.83 All these measures are likely to shorten the time that legal immigrants are separated from their spouses and children living abroad and could also reduce the size of the unauthorized population.

Another immigration policy issue with important implications for immigrant families is the deportation of unauthorized immigrants. About five million children in the United States have at least one unauthorized parent. Nearly one in three children of immigrant parents (and half of all foreign-born children) has at least one unauthorized parent.84 In the past decade, the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement stepped up workforce raids and deportations of unauthorized workers. The number of unauthorized immigrants arrested at workplaces increased from 500 in 2002 to 3,600 in 2006. Often the unintended victims of these raids and arrests are the children of the immigrants. Indeed, U.S. courts have ruled that having a citizen child is not sufficient cause to prevent deportation of parents who are not authorized to reside and work in the United States. In several case studies on the impact of workforce raids on children, Randy Capps and his colleagues found that the arrest and deportation of unauthorized workers often resulted in family separation and financial hardship for children of immigrants.85 For every 100 unauthorized workers arrested, about 50 children were in their care. Following a workforce raid, unauthorized immigrant parents were often held overnight while their children were placed in the care of neighbors, babysitters, and relatives. Single parents or parents who were the sole caregiver of children were often released on the same day. Frequently, however, one of the parents was held (some for several months) while the other was released on bond to care for children but not permitted to work. Despite assistance from family members, community organizations, and churches, these families experienced great financial hardship and emotional stress. Although the number of children directly affected by workforce raids now appears to be low compared with the overall number of children of immigrants, the effects could spread if deportation efforts are increased.

[2]Immigrant Integration Policy[end]

The successful economic and social integration of today’s immigrant families is key to the future well-being of the nation’s children. Of particular concern is the increase in the share of immigrant children living with single parents across generations. But developing policies that reduce the levels of marital dissolution and nonmarital childbearing for this population is extremely difficult. Researchers and policy makers do not know how to reduce these behaviors in the broader U.S. population, let alone among the children and grandchildren of immigrants. To some degree, declines in marriage rates and increases in single parenthood may be inevitable among immigrant families as they acculturate, because divorce and single parenthood have become increasingly commonplace in U.S. society. Nonetheless, it is clear that both marital dissolution and nonmarital childbearing are strongly associated with economic hardship—both because economic disadvantage leads to fewer marriages and greater marital instability and because single parenthood reduces the number of earners in children’s households. The successful economic integration of immigrant families is therefore critical to efforts to reduce the prevalence of single-parent families among second- and third-generation children and to reduce the negative consequences of living in a single-parent household. Measures to reduce poverty among all children of immigrants, regardless of their living arrangements, are of central importance.

Unlike many other countries with large immigrant populations, the United States has no explicit immigrant integration policy or programs. If anything, the U.S. government has weakened its support for immigrant families over the past three decades, as is evident in the steady withdrawal of social welfare benefits for noncitizens since the early 1980s and in the welfare reforms of 1996 that tied eligibility for federal welfare benefits to citizenship.86 Welfare reform led to substantial reductions in receipt of welfare among noncitizens and was also associated with increases in food insecurity among immigrant families and their children.87 Nor were the effects of welfare reform limited to noncitizens. Even though U.S.-born children of immigrants remained eligible for welfare benefits, their rates of participation in welfare programs, especially the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (formerly the Food Stamp program), decreased faster than did those of children of citizens. Some accounts suggest that the decrease in participation was attributable to immigrants’ confusion about eligibility, their worry that applying for benefits would jeopardize their ability to naturalize or sponsor relatives for immigration, or their fear of bringing attention to other unauthorized immigrants living in the household.88 Although some observers believe that immigrants should not receive economic support, accumulating evidence suggests that immigrants are unlikely to be drawn to the United States because of its welfare benefits. Nor are they especially “welfare-prone” or deterred from working because of the availability of welfare benefits.89 On the basis of that evidence, we suggest that more attention and resources should be directed toward immigrant settlement. Legal immigrants and their children should be granted greater access to the social safety net regardless of citizenship status. At the very least, immigrant parents need accurate information about social welfare benefits for which they and their children are eligible.

[1]Conclusion[end]

Children with immigrant parents are a rapidly growing part of the U.S. child population, and they are here to stay. Their health and development, educational attainment, and future social and economic integration will play a defining role in the nation’s future. Immigrant families have many strengths—in particular, high levels of marriage and commitment to family life—that clearly benefit their children and offset to some extent potential negative impacts of other risk factors. But despite their strengths, these families are vulnerable because of the separations and economic insecurities inherent in the migration process, the stresses of forging a new life in the United States, and the lack of an explicit U.S. immigrant integration policy. In facing these challenges, immigrant families reshape and adapt themselves through extended family living arrangements, social support networks of kin and non-kin, and family networks that extend beyond national boundaries.

Quite apart from immigration, children’s living arrangements in the United States have been changing rapidly in response to a rapid rise over the past several decades in nonmarital births, cohabitation, and marital dissolution. Despite rising rates of female employment, the growth of single parenthood resulting from these changes has led to a striking inequality in children’s life chances, with children in two-parent families having access to far more economic resources and parental time than children in families with only one, or, even worse, no parent.90 Differences in the living arrangements of children of immigrants by generational status suggest that as immigrant families spend more time in the United States, their family patterns progressively mirror those of the general population. The nation should pay special heed to how this aspect of immigrants’ Americanization heightens the vulnerability of their children.

Contributor Information

Nancy S. Landale, Professor of Sociology and Demography at The Pennsylvania State University.

Kevin J. A. Thomas, Assistant Professor of African and African American Studies, Sociology, and Demography at The Pennsylvania State University.

Jennifer Van Hook, Professor of Sociology and Demography at The Pennsylvania State University..

Endnotes

- 1.Fortuny Karina, Chaudry Ajay. Children of Immigrants: Immigration Trends. Urban Institute; Washington: 2009. Fact Sheet No. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ibid.

- 3.Authors’ calculations, 2005-2009 Current Population Surveys.

- 4.Zhou Min, Xiong Yang Sao. The Multifaceted American Experiences of the Children of Asian Immigrants: Lessons for Segmented Assimilation. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2005;28(no. 6):1119–52. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oropesa Ralph Salvador, Landale Nancy S. Immigrant Legacies: Ethnicity, Generation, and Children’s Familial and Economic Lives. Social Science Quarterly. 1997;78(no. 2):399–416. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amato Paul R. The Impact of Family Formation Change on the Cognitive, Social and Emotional Well-Being of the Next Generation. Future of Children. 2005;15(no 2):75–96. doi: 10.1353/foc.2005.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Hook Jennifer, Glick Jennifer E. Immigration and Living Arrangements: Moving Beyond Economic Need versus Acculturation. Demography. 2007;44(no. 2):225–49. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas Adam, Sawhill Isabel. For Love or Money? The Impact of Family Structure on Family Income. Future of Children. 2005;15(no 2):57–74. doi: 10.1353/foc.2005.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davidson Pamela R. Diversity in Living Arrangements and Children’s Economic Well-being in Single-Mother Households. In: Arrighi Barbara A., Maume David J., editors. Child Poverty in America Today. Praeger Publishers; Westport, Conn.: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amato The Impact of Family Formation Change on the Cognitive, Social and Emotional Well-Being of the Next Generation. (see note 5) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Glick Jennifer E., Van Hook Jennifer. Through Children’s Eyes: Families and Households of Latino Children in the United States. In: Rodríguez Havidán, Sáenz Rogelio, Menjívar Cecelia., editors. Latina/os in the United States: Changing the Face of América. Springer; New York: 2008. pp. 72–86. [Google Scholar]

- 12.The CPS provides information on the birthplace of the child and the child’s mother and father even if the child does not live with his/her parents.

- 13.Glick Jennifer E., Van Hook Jennifer. Migration Between Mexico and the United States: Binational Study. US Commission on Immigration Reform; 1998. The Mexican-Origin Population of the United States in the Twentieth Century. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duncan Brian, Hotz V. Joseph, Trejo Stephen J. Hispanics in the U.S. Labor Market. In: Tienda Marta, Mitchell Faith., editors. Hispanics and the Future of America. National Academies Press; Washington: 2006. pp. 228–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Telles Edward E., Ortiz Vilma. Generations of Exclusion: Mexican Americans, Assimilation, and Race. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Authors’ calculations from the 2005-2009 Current Population Surveys.

- 17.Duncan, Hotz, Trejo Hispanics in the U.S. Labor Market. (see note 13)

- 18.Van Hook Jennifer, Glick Jennifer. Immigration and Living Arrangements: Moving Beyond Economic Need versus Acculturation. Demography. 2007;44(no. 2):225–49. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menjívar Cecilia, Abrego Leisy. Parents and Children across Borders: Legal Instability and Intergenerational Relations in Guatemalan and Salvadoran Families. In: Foner Nancy., editor. Across Generations: Immigrant Families in America. New York University Press; New York: 2009. pp. 160–89. [Google Scholar]; Dreby Joanna. Negotiating Work and Family over the Life Course: Mexican Family Dynamics in a Binational Context. In: Foner Nancy., editor. Across Generations: Immigrant Families in America. New York University Press; New York: 2009. pp. 189–212. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ibid.

- 21.Authors’ calculations from the 2005-2009 Current Population Surveys.

- 22.Oropesa Ralph Salvador, Landale Nancy S. Why Do Immigrant Youth Who Never Enroll in U.S. Schools Matter? An Examination of School Enrollment among Mexicans and Non-Hispanic Whites. Sociology of Education. 2009;82:240–66. doi: 10.1177/003804070908200303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fortuny Karina, Chaudry Ajay. Children of Immigrants: Immigration Trends. Urban Institute; Washington: 2009. Fact Sheet No. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Passel Jeffrey. “Unauthorized Migrants: Numbers and Characteristics,” Background Briefing Prepared for Task Force on Immigration and America’s Future”. Jun, 2005.

- 25.Van Hook Jennifer, Fix Michael. 2010. No citation available yet.

- 26.Martin David A. A New Era for US Refugee Resettlement. Colombia Human Rights Law Review. 2004;36:299–322. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Min, Xiong Yang Sao. The Multifaceted American Experiences of the Children of Asian Immigrants: Lessons for Segmented Assimilation. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2005 November;28(no. 6):1119–52. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hein Jeremy. From Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia: A Refugee Experience in the United States. Twayne Press; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rumbaut Ruben. Passages to Adulthood: The Adaptation of Children of Immigrants in Southern California. In: Hernandez Donald., editor. Children of Immigrants: Health, Adjustment, and Public Assistance. National Academy Press; Washington: 1999. pp. 478–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waters Mary, Eschbach Karl. Immigration and Ethnic and Racial Inequality in the United States. Annual Review of Sociology. 1995;21:419–46. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rumbaut Ruben. Passages to Adulthood: The Adaptation of Children of Immigrants in Southern California. (see note 25)

- 32.Swartz Teresa, Lee Jennifer C., Mortimer Jeyland T. Achievements of First-Generation Hmong Youth: Findings from the Youth Development Study. CURA Reporter. 2003 Spring:15–21. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gold Steve. Migration and Family Adjustment: Continuity and Change among Vietnamese in the United States. In: McAddo Harriette Pipes., editor. Family Ethnicity: Strength in Diversity. Sage Publications; 1998. pp. 300–14. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rumbaut Ruben. Passages to Adulthood: The Adaptation of Children of Immigrants in Southern California. (see note 25)

- 35.Kim Rebecca. Ethnic Differences in Academic Achievement between Vietnamese and Cambodian Children: Cultural and Structural Explanations. Sociological Quarterly. 2002;43(no. 2):213–35. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguy Nga. The Khmer Institute; Dec, 1999. Obstacles to the Educational Success of Cambodians in America. www.khmerinstitute.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hein From Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia: A Refugee Experience in the United States. (see note 24)

- 38.Swartz, Lee, Mortimer Achievements of First-Generation Hmong Youth: Findings from the Youth Development Study. (see note 28)

- 39.More LJ. Laotian American Families. In: Lee Evelyn., editor. Working with Asian Americans: A Guide for Clinicians. Guilford Press; 1997. pp. 136–52. others. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hein From Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia: A Refugee Experience in the United States. (see note 24)

- 41.Kibria Nazli. Household Structure and Family Ideologies: The Dynamics of Immigrant Economic Adaptation among Vietnamese Refugees. Social Problems. 1994;41(no. 1):81–96. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiong Zha Blong, Tuicomepee Arunya. Hmong Families in America in 2000: Continuity and Change. In: Thao Bo, Schein Louisa, Niedzweicki Max., editors. Hmong 2000 Census Publication: Data and Analysis. Hmong National Development, Inc. & Hmong Cultural and Resource Center; 2006. pp. 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hernandez Donald, Denton Nancy, Mcartney Suzanne. Family Circumstances of Children in Immigrant Families. In: Lansford Jennifer E., Deater-Deckard Kirby, Bornstein Marc H., editors. Immigrant Families in Contemporary America. Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 9–29. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang Kou. The Hmong in America: Twenty-Five Years of the U.S. Secret War in Laos. Journal of Asian American Studies. 2001;4(no. 2):165–174. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kahn Joan R. Immigrant and Native Fertility during the 1980s: Adaptation and Expectations for the Future. International Migration Review. 1994;28(no. 3):501–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hutchison Ray, McNall Miles. Early Marriage in a Hmong Cohort. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1994;56(no. 3):579–90. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hein From Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia: A Refugee Experience in the United States. (see note 28)

- 48.Xiong Zha Blong, Tuicomepee Arunya. Hmong Families in America in 2000: Continuity and Change. In: Thao Bo, Schein Louisa, Niedzweicki Max., editors. Hmong 2000 Census Publication: Data and Analysis. Hmong National Development, Inc. & Hmong Cultural and Resource Center; 2006. pp. 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rumbaut Ruben, Weeks John. Fertility and Adaptation: Indochinese Refugees in the United States. International Migration Review. 1986;20(no. 2):428–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Swartz, Lee, Mortimer Achievements of First-Generation Hmong Youth: Findings from the Youth Development Study. (see note 28)

- 51.Hein From Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia: A Refugee Experience in the United States. (see note 24)

- 52.Ibid.

- 53.Bromley Mary Ann. Identity as a Central Adjustment Issue for the Southeast Asian Refugee Minor. Childcare Quarterly. 1988;17(no. 2):104–14. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Geltman Paul L. The ‘Lost Boys of Sudan’: Functional and Behavioral Health of Unaccompanied Refugee Minors Resettled in the United States. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159(no. 6):585–91. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.6.585. others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Piwowarczyk Linda A. Our Responsibility to Unaccompanied and Separated Children in the United States: A Helping Hand. Boston University Public Interest Law Journal. 2005;263:263–96. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bromley Identity as a Central Adjustment Issue for the Southeast Asian Refugee Minor. (see note 49)

- 57.Bates Laura. Sudanese Refugee Youth in Foster Care: The ‘Lost Boys’ in America. Child Welfare. 2005;84(no. 5):631–48. others. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Model Suzanne. West Indian Immigrants: A Black Success Story? Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brandon Peter D. The Living Arrangements of Children in Immigrant Families in the United States. International Migration Review. 2002;36(no. 2):416–36. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gordon April. The New Diaspora—African Immigration to the United States. Journal of Third World Studies. 1998;15(no.1):79–103. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kent Mary M. Immigration and America’s Black Population. Population Reference Bureau; Washington: 2007. [Google Scholar]