Abstract

Mammalian DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) is essential for maintaining DNA methylation patterns after cell division. Disruption of DNMT1 catalytic activity results in whole genome cytosine demethylation of CpG dinucleotides, promoting severe dysfunctions in somatic cells and during embryonic development. While these observations indicate that DNMT1-dependent DNA methylation is required for proper cell function, the possibility that DNMT1 has a role independent of its catalytic activity is a matter of controversy. Here, we provide evidence that DNMT1 can support cell functions that do not require the C-terminal catalytic domain. We report that PCNA and DMAP1 domains in the N-terminal region of DNMT1 are sufficient to modulate E-cadherin expression in the absence of noticeable changes in DNA methylation patterns in the gene promoters involved. Changes in E-cadherin expression are directly associated with regulation of β-catenin-dependent transcription. Present evidence suggests that the DNMT1 acts on E-cadherin expression through its direct interaction with the E-cadherin transcriptional repressor SNAIL1.

INTRODUCTION

Methylation of the C-5 position of cytosine (5 mC) in CpG dinucleotides is a fundamental epigenetic mark of the double-stranded DNA molecule. This chemical modification is directly involved in the structural transitions of the chromatin fiber from open to closed conformations that occur during chromatin compaction and transcriptional repression (1,2). The specific transfer of methyl groups to form 5mC is catalyzed by members of the DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) protein family. Three classes of DNMTs have been identified in mammals: DNMT1, DNMT2 and DNMT3 (including DNMT3a, DNMT3b and DNMT3L isoforms) (3,4). All of them share homologous catalytic domains but differ in their regulatory, protein–DNA- and protein–protein-binding regions.

DNMT1 is the most abundant DNA methyltransferase in mammalian somatic cells. This protein contains a large C-terminal catalytic domain, and several regulatory motifs in the N-terminal region, including the DMAP1- and PCNA-binding domains (BAH1 and BAH2), a cysteine-rich Zn-binding region, two bromo-adjacent homology domains and a replication foci-targeting sequence (Figure 1A). DNMT1 is actually present at functional replication foci and has a strong preference for hemimethylated DNA. Therefore, it is considered to be the enzyme that is primarily responsible for the essential functions of copying and maintaining methylation patterns from the parental to the daughter strand following DNA replication (3).

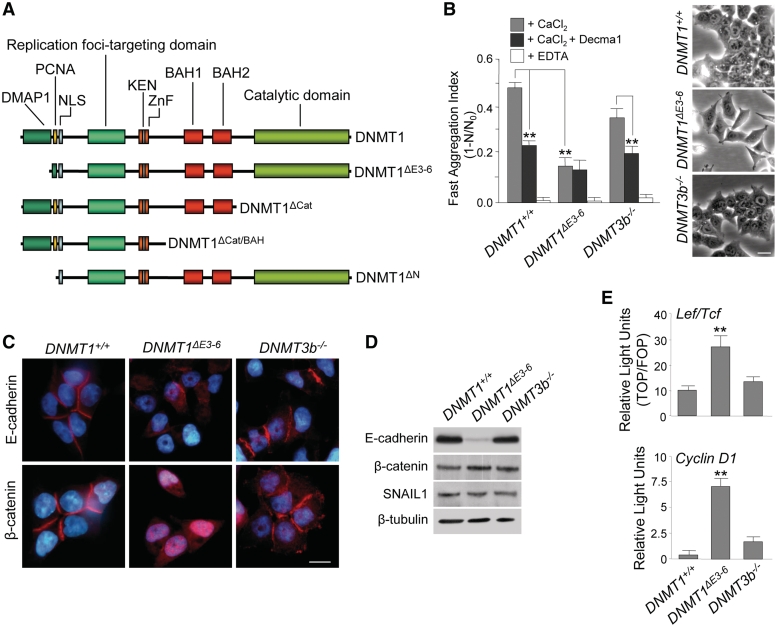

Figure 1.

Disruption of PCNA and DMAP1-binding domains of DNMT1 results in E-cadherin downregulation, nuclear translocation of β-catenin and activation of β-catenin-dependent transcriptional signaling. (A) Schematic representation of full-length DNMT1 protein domain structure and deletion mutants used in this study. DMAP1 domain, amino acids 1–120; PCNA domain, amino acids 163–174; NLS, nuclear localization signal domain, amino acids 177–205; DNA replication foci-targeting domain, amino acids 331–550; ZnF, zinc finger region, amino acids 646–692; KEN, KEN box (KENxxxR), amino acids 644–650; BAH1 and BAH2, bromo-adjacent homology domains, amino acids 755–880 and 972–1100, respectively; catalytic domain, amino acids 1139–1616. Pictures are not drawn to scale. (B) Phase-contrast images of living cultured cells (left panels) and Ca2+-dependent fast cell–cell aggregation assays in the presence or absence of a functional antibody against E-cadherin (Decma1) and the Ca2+-chelating agent EDTA (right panel). These indicate a strong reduction of cell–cell adhesiveness in human HCT116 cells lacking PCNA and DMAP1-binding domains of DNMT1 (DNMT1ΔE3−6), but not in parental cells (DNMT1+/+), or those lacking DNMT3b (DNMT3b−/−). The mean ± SD of results from three experiments are shown. **Student's t-test, P < 0.001. (C) Immunolocalization (red signal) of E-cadherin (upper panels) and β-catenin (lower panels) in HCT116 DNMT1+/+, DNMT1ΔE3−6 and DNMT3b−/− cells showing the extensive disorganization of E-cadherin cell–cell contacts and nuclear translocation of β-catenin in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells. Chromatin is counterstained with DAPI (blue signal). Bars: 10 μm. (D) Semiquantitative analysis of protein expression by immunoblot showing total levels of E-cadherin, β-catenin, and SNAIL1 in HCT116 DNMT1+/+, DNMT1ΔE3−6, and DNMT3b−/− cells. β-tubulin protein content is included as a loading control. (E) Normalized Luciferase/Renilla activities of reporter vectors transiently transfected in HCT116 DNMT1+/+, DNMT1ΔE3−6 and DNMT3b−/− cells containing either TOP multimerized promoter sequences recognized by β-catenin-Lef/Tcf complexes (upper panel), or the human cyclinD1 promoter (lower panel). The activity of both reporters is significantly higher in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells. Analyses were performed in triplicate and the mean ± SD are shown. **P < 0.001.

Consistent with this concept, it has been demonstrated that DNMT1 enzymatic activity is strictly required for genomic imprinting and X chromosome inactivation during mouse development (4). In mouse models, mutation of both copies of the Dnmt1 gene resulted in a pronounced failure to establish DNA methylation patterns in embryonic cells and subsequent embryonic lethality in mid-gestation (5). Similar experiments in HCT116 human colon cancer cells initially indicated that depletion of both full-length copies of the DNMT1 gene had no significant effect on DNA methylation or, therefore, on cell viability (6). Surprisingly, these cells exhibited only a modest reduction (<20%) in the whole genomic content of 5mC, suggesting that DNMT1 activity is either dispensable in human cells or rescued by another DNMT.

Further studies demonstrated that the original targeting mutation strategy of skipping DNMT1 gene expression in HCT116 cells actually led to a DNMT1 hypomorphyc allele with a low level of catalytic activity (20% of normal DNMT1 expression) (7,8). This hypomorph was the product of alternative splicing of the DNMT1 gene between exons 2 and 7, thus bypassing the knockout cassette that replaced exons 3, 4 and 5, and resulting in a catalytically active DNMT1 protein that lacked the PCNA and part of the DMAP-binding domains (DNMT1ΔE3−6; Figure 1A). Interestingly, the partial loss of 5mC observed in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells appeared specifically to affect highly repetitive sequences, such as pericentromeric Satellite2 and rDNA gene copies (1,9). In line with these findings, the first N-terminal region of DNMT1, encompassing the DMAP1 and PCNA domains, has been associated with specific target recognition and localization to AT-rich regions such as repetitive Line1 and satellite sequences (10,11).

Reduction of catalytically competent forms of DNMT1 in HCT116 cells below a 20% threshold, compared with normal DNMT1 expression, resulted in massive 5mC demethylation, loss of cell viability and cell death after mitotic catastrophe (7,8,12). Considered as a whole, these results demonstrate that, in mammals, DNMT1 catalytic activity plays an essential role in the maintenance of global DNA methylation patterns in the genome, and that the maintenance of these patterns is required for cellular viability.

Despite these observations, a potential role for DNMT1 in cell function independent of its catalytic activity has been suggested. However, there is no clear evidence for it and the matter remains controversial. In this sense, it has been shown that depletion of DNMT1 can result in activation of gene transcription by a DNA methylation-independent mechanism (13). In contrast, it has recently been claimed that catalytic DNA methyltransferase activity is required for all biological functions of DNMT1 (14). Here, we have used HCT116 cells expressing DNMT1ΔE3−6 hypomorphic alleles as a model to investigate the relevance of DMAP1, PCNA, and catalytic domains for DNMT1 function. Because the zinc finger factor SNAIL1 is the best know transcriptional repressor of the E-cadherin gene (15,16), we have specifically studied the SNAIL1-dependent downregulation of E-cadherin that takes place in these cells in comparison to parental HCT116 cells. Our results indicate that DMAP1 and PCNA domains can support biological functions of DNMT1 that are independent of its catalytic activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, expression vectors and transfections

Parental HCT116 cells (DNMT1+/+), HCT116 cells expressing an alternative spliced form of the DNMT1 gene after deletion of exons 3–6 (DNMT1ΔE3–6) (6–8), HCT116 cells lacking both copies of the DNMT3b gene (DNMT3b−/–) and HCT116 cells expressing DNMT1ΔE3–6 and also lacking both copies of DNMT3b (DKO cells) (17) were grown in DMEM under standard cell culture conditions. Two clones of DNMT1ΔE3–6 and DNMT3b−/– cells were used throughout this study. Stable transfectants of HCT116 cells expressing SNAIL1-shRNA or EGFP-shRNA were obtained using pSuperior-shRNA against SNAIL1 (18) or EGFP (19) and puromycin selection (1 μg/ml) for 3 weeks. At least four independent clones from each transfection were characterized. Samples for all different types of experiments performed throughout this study were collected in the exponential growth phase of the cell cycle of each cell line.

A cDNA corresponding to full-length DNMT1 gene-coding sequence (+1/+4851) was obtained by RT–PCR using specific oligonucleotides (Sequences of PCR primers used in this study are shown in Supplementary Table S1) from an mRNA pool purified from parental HCT116 cells, cloned in pcDNA3.1A (Invitrogen) or pRFP (Clontech) plasmids and sequenced. From these plasmids, deletion mutants of full-length DNMT1 lacking the catalytic domain (DNMT1Δcat; +1/+3494), the catalytic and both BAH domains (DNMT1ΔCat/BAH; +1/+2421) or the N-terminal region encompassing DMAP and PCNA domains (DNMT1ΔN; +1469/+4851) were generated by PCR using specific adapters. A 1226Cys>Val substitution (DNMT1mut) in the catalytic domain was also generated using standard protocols for site-directed mutagenesis.

A 1.6-kb fragment of the SNAIL1 5′ upstream sequences was amplified by PCR from a human genomic clone (Invitrogen) using specific oligonucleotides. This human 5′ upstream sequence of SNAIL1, as well as the proximal E-cadherin (a gift from Dr F Van Roy, University of Ghent, Belgium) and Cyclin D1 (a gift from Dr A Muñoz, IIB-CSIC, Madrid, Spain) promoters, or TOP/FOP constructs, containing multimerized wild-type and mutated β-catenin/Lef1-binding sites (a gift from H Clevers, Hubrecht Institute, Holland), respectively, were all cloned into pGL2 Luciferase reporter plasmid and sequenced. Luciferase activity of the aforementioned constructs was measured using the Glo-Luciferase reporter assay kit (Promega) and normalized to Renilla activity in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. In all cases, 6 × 105 cells were transiently transfected in triplicate using Lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen) with 2 μg of the aforementioned plasmids.

For the extended biomolecular fluorescence complementation assays (ExBiFC) (23), a full-length DNMT1 cDNA was cloned in the ExBiFC RFP/C-YFP plasmid and a full-length SNAIL1 cDNA was cloned in the ExBiFC CFP/N-YFP plasmid (a gift from R Brack-Werner, GSF-National Research Center for Environment and Health, Neuherberg, Germany). HCT116 cells growing on coverslips were transfected using Lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen) with 15 μg of the aforementioned plasmids.

Immunological methods

Antibodies used in this study included: mouse anti-SNAIL1 (a gift from Dr I Virtanen, University of Helsinki, Finland), mouse anti-DNMT1 (BD Pharmingen) mouse anti-β-catenin (BD Transduction), mouse anti-ABC β-catenin, detecting an active form of β-catenin dephosphorylated on Ser37 or Thr41 (Upstate), rat anti-E-cadherin (ECCD2), mouse anti-β-tubulin (Amersham) and rabbit anti-myc epitope (Sigma). The secondary antibodies used were HRP-coupled anti-rabbit, anti-mouse (Amersham) and anti-rat (Pierce), and anti-mouse, anti-rat and anti-rabbit coupled to either Cy2 or Cy3 (Jackson), as indicated.

Coimmunoprecipitation, pull down, immunoblot and immunolocalization experiments were performed essentially as described elsewhere (9,20). For immunoblots, HRP activity was detected using the ECL-chemiluminescent kit (Amersham) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Quantification of the Integrated Density of semiquantitative immunoblots was performed by using the Image J software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij).

After immunolocalization experiments or ExBiFC plasmid transfection assays, samples were analyzed at room temperature with either a fluorescence microscope (Axiophot; Zeiss) or a laser-scanning confocal microscope (TCS-SP2-AOBS; Leica) equipped with HC PL APO CS 20 × NA 0.70, HCX PL APO CS 40 × NA 1.25, and HCX PL APO Ibd BL 63 × NA 1.4 objective lenses. Images were acquired with LCS Suite version 2.61 (Leica), and were edited using the free GNU Image Manipulation Program (http://www.gimp.org).

SPLIT-TEV detection DNMT1/SNAIL1 interactions

For SPLIT-TEV assays, constructs containing the SNAG domain of SNAIL1 and either the DMAP1/PCNA or catalytic domains of DNMT1 were engineered on pBK-GCN4-N- and C-TEV plasmids as described (21). Full-length SNAIL1 and DNMT1 coding sequences were amplified by PCR and cloned in XbaI and NheI sites of the GCN4 vectors. To isolate the SNAG domain from SNAIL1, an extra NheI site was created by directed mutagenesis (22), to eliminate the C-terminal coding region beyond the SNAG domain. The same strategy was used for the DMAP1/PCNA region of DNMT1. For the catalytic domain of DNMT1, an XbaI site was introduced in full-length DNMT1 to eliminate the N-terminal region before the catalytic domain. All deoxyoligonucleotides sequences are available upon request. Constructs were checked by sequencing and western blotting.

Different combinations of SPLIT-TEV constructs were transfected into HeLa cells. In all cases, transfected combinations included the membrane-bound transcriptional activator GV (TM-GV) and its target reporter containing five GAL4 responsive elements (G5-Luc) driving a Renilla luciferase gene (G5-Luc/pTK-RL). Both plasmids were combined with different constructs including the N- or C-terminal regions of the TEV protease fused to the GCN4 coiled-coil region, to the SNAG domain from SNAIL1, to the DMAP1/PCNA or to the catalytic domain of DNMT1. Transfections were developed with Lipofectamine and luciferase activity was measured as described above.

Fast cell–cell aggregation assays

Cells grown to subconfluence were incubated at 37°C in 0.25% trypsin without EDTA (Gibco) in the presence of 2 mM CaCl2 to preserve Ca2+-dependent cell–cell adhesion. Detached cells were washed in PBS, resuspended in 2 mM EDTA–PBS, and thoroughly pipetted to dissociate cell–cell contacts. Isolated cells were washed in PBS and 30 × 103 cells were plated in T24 wells (Costar) in 400 µl of either 2 mM EDTA–PBS or 2 mM CaCl2-PBS, or 2 mM CaCl2-PBS + 0.2 mg/ml of a functional antibody against E-cadherin (Decma1; Sigma). Aggregation assays were performed for 45 min at 37°C rotating at 85 rpm; the aggregation index was calculated as the ratio 1 – N/N0, where N and N0 are the numbers of particles at the end and the beginning of the experiment, respectively. Particles were counted in a Coulter Counter (Beckman). Experiments were performed in triplicate and the mean ± SD calculated.

RT–PCR and qRT–PCR analysis

Total RNA from cell lines was extracted with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and treated with DNaseI (Ambion). An amount of 2 µg of RNA were used to obtain cDNA using oligo(dT) primers and SuperScript Reverse Transcriptase (Life Technologies). An amount of 100 ng of cDNA were used for subsequent PCR experiments. Specific primers (Sequences of PCR primers used in this study are shown in Supplementary Table S1) were designed between different exons, thereby avoiding residual genomic DNA amplification, for semiquantitative or quantitative transcript detection of E-cadherin, SNAIL1, and GAPDH using TaqExpand High Fidelity (Roche) as described elsewhere (16,23,24).

ChIP assays

ChIP assays were performed as previously described (9,20). Briefly, before formaldehyde crosslinking, cells were treated with 10 mM dimethyl adipimidate (DMA) 0.25% DMSO in PBS for 45 min. Chromatin was then sheared to an average length of 0.25–1 kb. HDAC1 and DNMT1 were immunoprecipitated with the aforementioned antibodies.

DNA methylation analysis

The DNA methylation status of promoter sequences of E-cadherin and SNAIL1 genes was analyzed by bisulfite sequencing (9) and DNA restriction with a methylation-sensitive endonuclease followed by PCR. For bisulfite genomic sequencing, both strands were sequenced and at least 10 clones were analyzed per sequence. Supplementary Table S1 shows all the PCR primers used in the article.

RESULTS

Loss of E-cadherin-dependent cell–cell adhesion and transcriptional-competent nuclear translocation of β-catenin in DNMT1ΔE3–6 cells

Human HCT116 are epithelial cells showing high levels of expression of DNMT1 and DNMT3b, but not of DNMT3a or other components of the DNMT family (6,17). These cells exhibited well-formed cell–cell contacts and significant Ca2+-dependency for cell–cell adhesion in fast aggregation assays (Figure 1B). Using specific functional antibodies able to efficiently inhibit E-cadherin-mediated cell–cell adhesion (Decma1), we found that a large fraction of Ca2+-dependent cell–cell adhesion in HCT116 cells was supported by E-cadherin activity (Figure 1B). Notably, HCT116 cells exclusively expressing an alternative spliced form of the DNMT1 mRNA that lacked exons 3–6 (DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells; two different clones were used throughout this study, giving essentially equivalent results) had a scattered phenotype and presented a drastic downregulation of E-cadherin expression, which was associated with a significant loss of Ca2+-dependent cell adhesion (Figure 1B–D and Supplementary Figure S1). In parallel with E-cadherin downregulation, DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells strongly re-expressed vimentin and fibronectin, two markers associated with epithelial–mesenchymal transitions (Supplementary Figure S2). In contrast, complete suppression of DNMT3b gene expression in HCT116 cells (DNMT3b−/− cells; two different clones were used throughout this study, giving essentially equivalent results) had no statistically significant effect on E-cadherin expression or on Ca2+-dependent cell adhesion (Figure 1B–D and Supplementary Figure S1). These observations indicate that the PCNA and part of the DMAP1 domains in the N-terminal region of human DNMT1 protein (corresponding to exons 3–6 in the DNMT1 gene) are involved in regulating E-cadherin expression.

We also found that, concomitant with the downregulation of E-cadherin expression in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells, β-catenin was released from cell–cell contacts and translocated to the nucleus (Figure 1C). β-Catenin is an essential component of the E-cadherin adhesion complex. This protein is not only strictly required at the cell membrane for E-cadherin-dependent cell–cell adhesion, but also, equally importantly, is a central element of the Wnt-signaling pathway. In resting conditions, β-catenin released from cell–cell contacts is rapidly destroyed in the cytoplasm by the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway. However, upon canonical Wnt activation, β-catenin can dissociate from E-cadherin complexes in the cell membrane, and may be stabilized in the cytoplasm and translocate to the nucleus, whereupon it promotes the activation of target genes after binding to Lef/Tcf transcription factors (25). Importantly, no changes in β-catenin expression levels were observed in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells (Figure 1D). This observation indicates that nuclear-translocated β-catenin can be metabolically stabilized and transcriptionally competent in these cells. Therefore, we next investigated the ability of released β-catenin to activate Wnt/β-catenin targets by measuring the activity of exogenous TOP-Luciferase reporters, which are specifically recognized by β-catenin-Lef/Tcf complexes. As expected, DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells showed significantly greater activation of Wnt/β-catenin reporter sequences than did parental and DNMT3b−/− cells (Figure 1E). We also analyzed the activation of an exogenous reporter containing the CyclinD1 promoter, a direct gene target of activated β-catenin-Lef/Tcf complexes (26,27). Strong activation of the CyclinD1 reporter was observed in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells compared with parental DNMT1+/+ and DNMT3b−/− cells (Figure 1E). These results imply that DNMT1, but not DNMT3b, can potentially modulate Wnt/β-catenin signaling by downregulation of E-cadherin expression and the associated release of transcriptionally competent β-catenin.

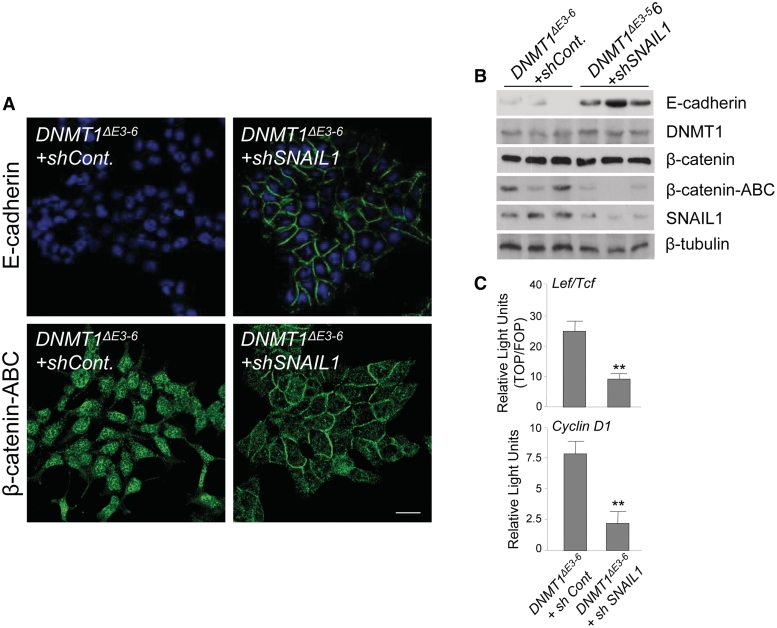

Downregulation of E-cadherin in DNMT1ΔE3–6 cells depends on SNAIL1

The zinc finger factor SNAIL1 is perhaps the most potent transcriptional repressor of the E-cadherin gene (15,16). We found a detectable level of expression of SNAIL1 protein in HCT116 DNMT1+/+ cells, and equivalent quantities in DNMT1ΔE3−6 and DNMT3b−/− cells (Figure 1D and Supplementary Figure S1). To evaluate the importance of SNAIL1 in the E-cadherin downregulation observed in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells, we designed a SNAIL1 knockdown experiment. We reasoned that if SNAIL1 is fundamental in the repression of E-cadherin and in the β-catenin nuclear translocation observed in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells, the siRNA-mediated depletion of SNAIL1 in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells should restore a phenotype similar to that of parental HCT116 DNMT1+/+ cells. Indeed, we found that siRNA-mediated depletion of SNAIL1 in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells resulted in the strong downregulation of metabolically stable, dephosphorylated forms of β-catenin (Figure 2A and B). This was associated with the almost complete nuclear exit and relocalization to cell–cell contacts of β-catenin, and re-expression of E-cadherin in the cell membrane (Figure 2A and B). Equally important, Wnt/β-catenin transcriptional targets are efficiently repressed in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells after siRNA-mediated depletion of SNAIL1 (Figure 2C). These results demonstrate that SNAIL1 is the repressor factor involved in the downregulation of E-cadherin in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells.

Figure 2.

SNAIL1 is directly involved in the regulation of E-cadherin expression and nuclear translocation of β-catenin in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells. (A) Immunolocalization analyses showing re-expression of E-cadherin and relocalization of β-catenin from the cell nucleus to newly formed cell–cell contacts after siRNA-mediated depletion of SNAIL1 in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells. Stable transfections of shRNA-EGFP or Mock vectors were performed as controls. At least three stable clones or transient transfections were analyzed. Bar: 10 μm. (B) siRNA-mediated depletion of SNAIL1 in cells expressing DNMT1ΔE3−6 by stable transfection of the corresponding shRNAs. Protein expression by immunoblot indicates that E-cadherin is re-expressed after depletion of SNAIL1. Similarly, levels of a metabolically stabilized form of β-catenin, dephosphorylated on Ser37 or Thr41 (β-catenin-ABC), are strongly reduced after SNAIL depletion in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells. No significant changes of DNMT1 protein expression levels were observed. Three different siRNA-transfected clones are represented. β-tubulin expression was used as loading control. (C) Normalized Luciferase/Renilla activities in HCT116 DNMT1ΔE3−6 control and siSNAIL1 cells, after transient cotransfection of reporter vectors containing multimerized promoter sequences recognized by β-catenin-Lef/Tcf complexes (upper) or cyclin D1 promoter (lower). Analyses were performed in triplicate and the mean ± SD are shown. **P < 0.001.

Downregulation of E-cadherin in DNMT1ΔE3–6 cells occurs at the transcription level but does not involve changes in SNAIL1 mRNA expression or in E-cadherin and SNAIL1 promoter methylation

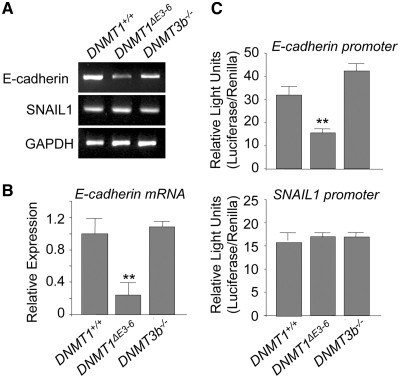

We next investigated the effect of the disruption of PCNA and DMAP1 domains in both copies of the DNMT1 gene on the activity of the E-cadherin promoter. We first examined the expression of the E-cadherin mRNA. As shown in Figure 3A and B, E-cadherin levels were significantly reduced in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells, suggesting that the E-cadherin promoter is severely repressed in these cells relative to parental DNMT1+/+ and DNMT3b−/− cells. To determine the effect of DNA methylation on this repression, we examined by bisulfite sequencing and DNA restriction with a methylation-sensitive endonuclease followed by PCR the status of CpG methylation in the E-cadherin promoter. Interestingly, no CpG methylation was detected in the endogenous E-cadherin promoter in parental HCT116 DNMT1+/+ cells, and no changes in DNA methylation status occurred in DNMT1ΔE3−6 or DNMT3b−/− cells (Supplementary Figure S3). Analysis of the activity of a non-methylated reporter containing the human E-cadherin promoter revealed that its activity was significantly diminished in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells (Figure 3C), which suggests the existence of a fast-acting molecular mechanism that efficiently represses the activity of the exogenous E-cadherin promoter in these cells. In cultured cells, the acquisition of a stable ‘de novo’ DNA methylation mark, or the reversion of previously established DNA methylation imprinting, is a long-term process requiring several rounds of DNA replication. Therefore, the above results suggest that repression of E-cadherin in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells is a DNA-methylation-independent event at the E-cadherin promoter level.

Figure 3.

Disruption of PCNA and DMAP1-binding domains of DNMT1 induces E-cadherin gene repression at the transcriptional level in the absence of changes in SNAIL1 expression. (A) Semiquantitative analysis of mRNA expression by RT–PCR of the indicated genes in HCT116 DNMT1+/+, DNMT1ΔE3−6 and DNMT3b−/− cells. A significant and repetitive reduction of E-cadherin mRNA is observed in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells. No differences are observed in total levels of SNAIL mRNA. Results shown are representative of at least three independent experiments. (B) Quantitative analysis of E-cadherin mRNA expression by qRT–PCR in HCT116 DNMT1+/+, DNMT1ΔE3−6 and DNMT3b−/− cells. Relative expression levels are normalized to actin expression. Results are representative of those from three experiments. (C) Normalized Luciferase/Renilla activities of reporter vectors transiently transfected in HCT116 DNMT1+/+, DNMT1ΔE3−6 and DNMT3b−/−, containing either the human E-cadherin promoter (upper panel) or the human SNAIL11 promoter (lower panel). Reduced E-cadherin promoter activity is observed in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells, while no changes are observed in the activity of the SNAIL1 promoter. Analyses were performed in triplicate and the mean ± SD are shown. **P < 0.001.

Analysis of DNA methylation at CpG sites revealed that the SNAIL1 promoter was equally unmethylated in parental HCT116 DNMT1+/+, as well as in DNMT1ΔE3−6 and DNMT3b−/− cells (Supplementary Figure S3). Furthermore, all these cell lines showed similar levels of SNAIL1 mRNA expression and an exogenous Luciferase reporter directed by the human SNAIL1 promoter showed similar activity in all tested cell lines (Figure 3A–C). Taken together, these observations suggest that a DNMT1/SNAIL1-dependent mechanism is responsible for the repression of the E-cadherin gene in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells and that this mechanism occurs in the absence of noticeable changes in DNA methylation. Since HCT116 DNMT1+/+, DNMT1ΔE3−6 and DNMT3b−/− cells have significantly different E-cadherin expression levels and an approximately equivalent level of expression of SNAIL1, the above results imply that the PCNA and/or DMAP1 domains of DNMT1 are implicated in the post-transcriptional regulation of SNAIL1 function. This mechanism can also efficiently modulate β-catenin-dependent transcriptional activity.

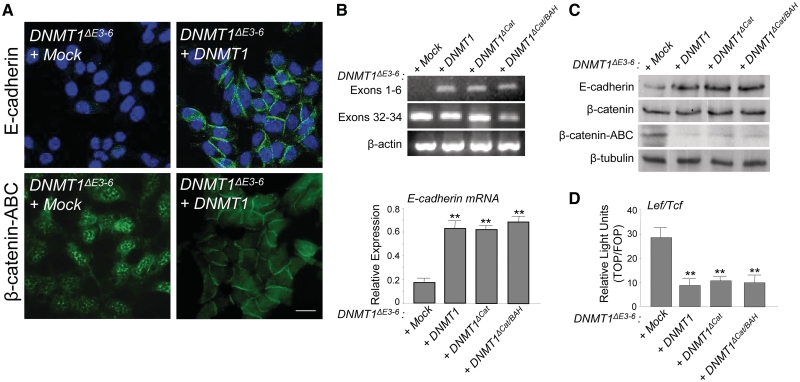

The DMAP1 and PCNA domains of DNMT1 are sufficient to restore E-cadherin expression in DNMT1ΔE3–6 cells

We next investigated the relevance of the PCNA/DMAP1 region and the requirement for the catalytic domain of DNMT1 in the DNMT1-dependent regulation of E-cadherin observed in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells. To this end, we first reintroduced a cDNA coding for full-length DNMT1, and thus PCNA and DMAP1-coding regions, into DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells. We found that expression of an exogenous full-length DNMT1 was sufficient to restore E-cadherin expression and protein localization at cell–cell contacts, and to force the relocalization of β-catenin to the cell membrane in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells (Figure 4A). By analyzing the presence of exons 1–6, which correspond to the DMAP1 and PCNA coding regions, compared with exons 32–34, which correspond to a part of the catalytic domain-coding region of the DNMT1 gene, we confirmed the absence of DMAP1 and PCNA full domains in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells, as expected, and the re-expression of both domains after full-length DNMT1 transfection (Figure 4D). Importantly, exogenous transcriptional β-catenin/Lef/Tcf targets were efficiently repressed by re-expression of full-length DNMT1 (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

PCNA and DMAP1 domains of DNMT1, but not its catalytic region, are directly involved in the regulation of E-cadherin expression and nuclear translocation of β-catenin in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells. (A) Immunolocalization analyses showing re-expression of E-cadherin and relocalization of β-catenin from the cell nucleus to newly formed cell–cell contacts after reintroduction of full-length DNMT1 in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells. At least three stable clones or transient transfections were analyzed. Bar: 10 μm. (B) Upper panel: Semiquantitative analysis of mRNA expression by RT–PCR of exons 1–6 and exons 32–34 of the DNMT1 gene in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells transfected with full-length DNMT1 cDNA (DNMT1), or deletion forms of DNMT1 cDNA lacking the catalytic domain (DNMT1ΔCat), or the catalytic and BAH domains (DNMT1ΔCat/BAH). Results are representative of two different experiments. Actin expression was used as a loading control. Lower panel: Quantitative analysis of E-cadherin mRNA expression by qRT–PCR in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells transfected with full-length DNMT1 cDNA (DNMT1), or deletion forms of DNMT1 cDNA lacking the catalytic domain (DNMT1ΔCat), or the catalytic and BAH domains (DNMT1ΔCat/BAH). Relative expression levels are normalized to actin expression. Results are representative of three different experiments and the mean ± SD are shown. **P < 0.001. (C) Semiquantitative analysis by immunoblot of E-cadherin, β-catenin and β-catenin-ABC protein expression in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells transfected with full-length DNMT1 cDNA (DNMT1), or deletion forms of DNMT1 cDNA lacking the catalytic domain (DNMT1ΔCat), or the catalytic and BAH domains (DNMT1ΔCat/BAH). Results are representative of two different experiments. β-tubulin expression was used as a loading control. (D) Normalized Luciferase/Renilla activity of reporter vector containing multimerized promoter sequences recognized by β-catenin-lef/tcf complexes in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells transiently transfected with full-length DNMT1 cDNA (DNMT1), or deletion forms of DNMT1 cDNA lacking the catalytic domain (DNMT1ΔCat), or the catalytic and BAH domains (DNMT1ΔCat/BAH). Analyses were performed in triplicate and the mean ± SD are shown. **P < 0.001.

DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells were also transfected with deletion forms of DNMT1 cDNA lacking the catalytic domain (DNMT1ΔCat), or the catalytic and BAH domains (DNMT1ΔCat/BAH) (Figure 1A). Both deletion mutants were located in the cell nucleus (Supplementary Figure S4) and efficiently restored the expression of exons 1–6 of the DNMT1 gene (Figure 4B). Taking into account the experimental design of this assay, it is assumed that the forced re-expression of exons 1–6 of DNMT1, coding for the PCNA and DMAP1 regions of the protein, resulted from the expression of the exogenous DNMT1ΔCat and DNMT1ΔCat/BAH isoforms (lacking the catalytic domain) and not from the endogenous DNMT1ΔE3−6 isoform (lacking exons 3–6). Notably, re-expression of exons 1–6 of DNMT1 in these experimental conditions was able to efficiently induce E-cadherin expression at mRNA (Figure 4B) and protein (Figure 4C) levels, promoting a significant reduction of metabolically stabilized β-catenin (Figure 4C) and a concomitant repression of exogenous Wnt/β-catenin transcriptional targets (Figure 4D). The repression activity on Wnt/β-catenin transcriptional targets can be associated to a functional sequestering of β-catenin at the cell membrane after E-cadherin re-expression. These results indicate that the catalytic domain of DNMT1 is dispensable for the regulation of E-cadherin transcription in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells. In contrast, PCNA and DMAP1 domains appear to be directly involved in the control of E-cadherin expression.

To further demonstrate the importance of DMAP1 and PCNA domains in the regulation of E-cadherin expression, we have used DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells with a combined somatic deletion of both copies of the DNMT3b gene (DNMTDKO cells). These cells exhibited a loss of Ca2+-dependent cell–cell adhesion, a drastic downregulation of E-cadherin, a nuclear translocation of β-catenin and an activation of β-catenin-dependent transcriptional activity which closely resembles the phenotype observed in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells, compared with parental HCT116 cells (Supplementary Figure S5). Strikingly, this phenotype is fully restored after reintroduction of full-length DNMT1 (Supplementary Figure S5). These results highlight the relevance of DMAP1 and PCNA domains of DNMT1 in the regulation of E-cadherin expression and β-catenin localization and transcriptional activity.

The DMAP1 and PCNA domains of DNMT1 are required to interact with SNAIL1 and can regulate the binding of SNAIL1 to the E-cadherin promoter

To gain further insight into the molecular mechanism underlying the inhibition of E-cadherin expression that takes place in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells, we investigated the potential association of SNAIL1 with the E-cadherin promoter using ChIP assays. We found that SNAIL1 is physically associated with the E-cadherin promoter in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells, but not in parental DNMT1+/+ or DNMT3b−/− cells (Figure 5A), in close agreement with E-cadherin mRNA regulation in these cell lines (Figure 3A and B). Our previous work has shown that SNAIL1 can interact and recruit the histone deacetylase modifier HDAC1 to exert its repressor activity on the E-cadherin promoter (20). Therefore, we also investigated the association of HDAC1 with the E-cadherin promoter in our cell system. As expected, HDAC1 was specifically bound to the E-cadherin promoter in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells, but not in parental DNMT1+/+ or DNMT3b−/− cells (Figure 5A). In addition, no interaction of DNMT1 with the E-cadherin promoter was detected in neither DNMT1+/+, DNMT1ΔE3−6 or DNMT3b−/− cells, but association of DNMT1 to Satellite 2 repetitive sequences occurred in DNMT1+/+ and DNMT3b−/− but not in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells (Figure 5A). These results indicate that deletion of the DMAP1 and PCNA domains of DNMT1 is sufficient to promote the recruitment of SNAIL1/HDAC1 complexes to the E-cadherin promoter in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells in a process that seems to be independent of the association of DNMT1 to this promoter region. The recruitment of Poly-comb repressors (EZH2 and Suz12) was not observed.

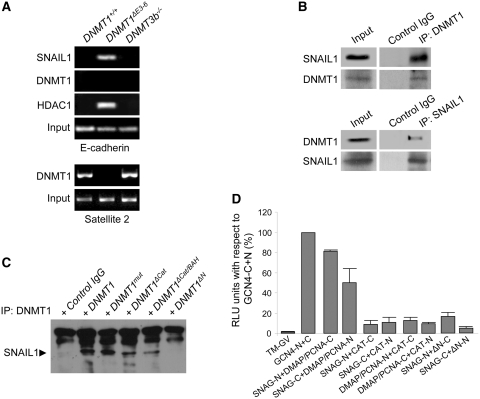

Figure 5.

The DMAP and PCNA domains of DNMT1 are required to interact with SNAIL1 and can regulate the association of SNAIL1 with the E-cadherin promoter. (A) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis of the interaction of SNAIL1, DNMT1 and HDAC1 with the E-cadherin promoter in HCT116 DNMT1+/+, DNMT1ΔE3−6 and DNMT3b−/− cells, showing strong association of SNAIL1 and HDAC1 specifically in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells. Association of DNMT1 with Satellite 2 repetitive sequences (lower panels) was used as control. Results are representative of two experiments. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation analysis showing the interaction of SNAIL1 and DNMT1 in protein extracts of HCT116 cells after independent immunoprecipitation of either endogenous DNMT1 (upper panels) or endogenous SNAIL1 (lower panels). Results are representative of three experiments. (C) Pull-down assays showing the interaction of endogenous SNAIL1 with exogenously expressed full-length DNMT1 or deletion lacking the catalytic domain (DNMT1ΔCat), the catalytic and both BAH domains (DNMT1ΔCat/BAH) or the N-terminal region encompassing DMAP and PCNA domains (DNMT1ΔN). A 1226Cys>Val substitution (DNMT1mut) in the catalytic domain was also used. Results are representative of two different experiments. (D) Demonstration of a direct interaction of the SNAG domain of SNAIL1 with the DMAP1/PCNA domains of DNMT1 by the SPLIT-TEV method. The graph shows the relative luciferase activity of different combinations of construct transfections as indicated. As a positive control for full reporter activation to compare different experiments, a combination of the N- and C-terminal regions of the TEV protease fused to the GCN4 coiled-coil region in the presence of the membrane-bound transcriptional activator GV (TM-GV) was considered as 100% luciferase activity (GCNA4-N+C). On the opposite, luciferase activity in the presence of the membrane-bound transcriptional activator GV but in the absence of TEV activity was considered as background level (TM-GV). Combinations of either N- or C-terminal constructs of the SNAG domain of SNAIL1 with either N- or C-terminal constructs of DMAP1/PCNA domains, but not with the catalytic (CAT) domain, of DNMT1 showed a significant and strong activation of the luciferase activity reporter. The mean ± SEM of three different experiments performed in triplicate is represented.

In this context, we hypothesized that DNMT1 could bind SNAIL1 to alter the association of this repressor with the E-cadherin promoter and/or to inhibit the formation of SNAIL1/HDAC complexes. To test this, we performed a series of coimmunoprecipitation assays, which showed that endogenous DNMT1 and SNAIL1 can be associated in vivo (Figure 5B). As expected, the interaction of DNMT1 and SNAIL1 was disrupted in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells (Supplementary Figure S6). Further assays, using different mutant forms of DNMT1 to pull-down endogenous SNAIL1, showed that the DMAP1/PCNA region of DNMT1 is required to interact with SNAIL1. Thus, an exogenous full-length form of DNMT1, as well as mutant forms of DNMT1 lacking the catalytic domain (DNMT1ΔCat), or the catalytic and both BAH domains (DNMT1ΔCat/BAH), but containing the DMAP1 and PCNA domains, and a 1226Cys>Val substitution (DNMT1mut) in the catalytic domain (Figure 1A), were all able to bind to SNAIL1 (Figure 5C). In contrast, a mutant DNMT1 form lacking the N-terminal region containing DMAP1 and PCNA domains (DNMT1ΔN) was unable to interact with SNAIL1 in these assays (Figure 5C).

To further study the interaction between DNMT1 and SNAIL1, we used the SPLIT-TEV method (21). In this technique, domains of interest are tagged as fusion proteins to either the N- or C-terminal regions of the TEV protease. TEV activity is restored only if interaction of tagged domains takes place. Once activated, reconstituted TEV protease can then operate on the second branch of the SPLIT-TEV method, namely, an exogenous transcription factor that is anchored to the cell membrane through a TEV target sequence (TM-GV). This exogenous transcription factor directs the synthesis of Luciferase from a GAL4 artificial promoter. Once TEV protease is reconstituted, membrane-bound TM-GV is released and the activity of the released transcription factor is measured as luciferase activity.

In agreement with the results described above, we found a positive interaction in the SPLIT-TEV assay when full-length SNAIL1 and DNMT1 proteins were tested (data not shown). Therefore, we next studied the specific interaction of the SNAG domain from SNAIL1 with either the DMAP1/PCNA or the catalytic (CAT) domains of DNMT1 (Figure 5D). We found that SNAG and DMAP1/PCNA domains can strongly interact with each other, using either the N- or the C-terminal constructs (Figure 5D). In contrast, none of these domains showed significant interactions with the CAT domain (Figure 5D). We also found that a DNMT1 construct lacking the N-terminal DMAP1 and PCNA domains (DNMT1ΔN) was also unable to bind the SNAG domain (Figure 5D). These results demonstrate that the SNAG domain of SNAIL1 can physically interact with the PCNA/DMAP1 domains of DNMT1.

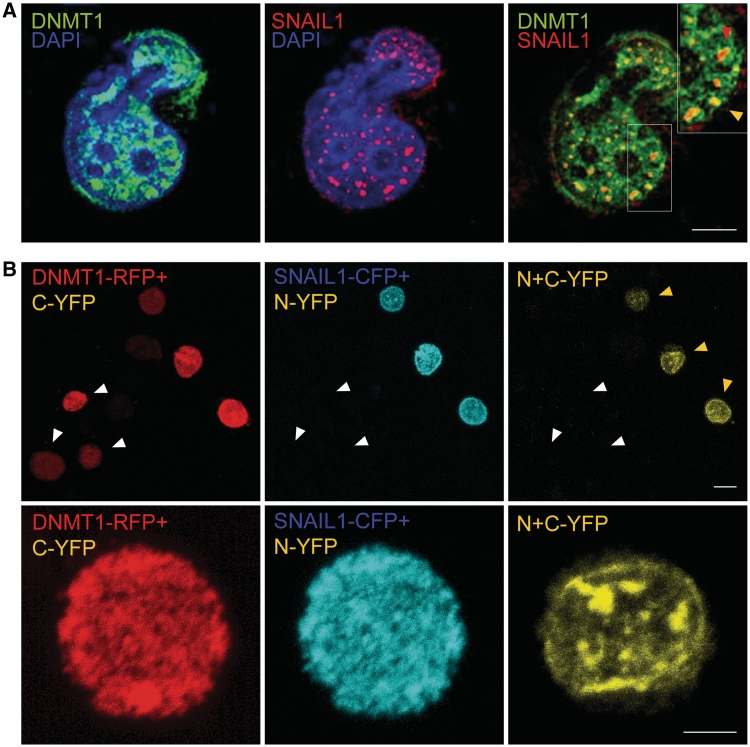

Consistent with these results, confocal microscopy immunolocalization assays also indicated that DNMT1 and SNAIL1 can co-localize in discrete positions in the cell nucleus of DNMT1+/+ cells (Figure 6A) but not in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells (Supplementary Figure S6). To further demonstrate the co-localization of DNMT1 and SNAIL1 in the nuclear compartment, a set of extended biomolecular fluorescence complementation assays (ExBiFC) (28) were performed in HCT116 cells. In this experimental approach, proteins under study are tagged either with red fluorescent protein (RFP) fused to the C-terminal fragment of the yellow fluorescent protein (C-YFP) (here, full-length DNMT1) or with cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) fused to the N-terminal of YFP (N-YFP) here, SNAIL1. Co-localization of both target proteins is revealed by a unique YFP emission. Our results have consistently shown that exogenously transfected DNMT1 (revealed as RFP emission) and SNAL1 (revealed as CFP emission)-tagged proteins were homogenously distributed in the nuclear compartment, but co-localization of both proteins mainly occurred in discrete locations (Figure 6B and an additional example is shown in Supplementary Figure S7A). Interestingly, no YFP emission was detected when a mutant DNMT1 form lacking the DMAP1 and PCNA domains (DNMT1ΔN) was assessed (Supplementary Figure S7b). The described interaction between DNMT1 and SNAIL1 was not restricted to cancer cells, but it was also observed by co-immunoprecipitation experiments in human embryonic kidney cells (Supplementary Figure S8). Overall, the above observations strongly suggest that DNMT1 and SNAIL1 can interact to form a macromolecular complex in the cell nucleus.

Figure 6.

DNMT1 and SNAIL1 can interact in the cell nucleus. (A) Direct immunofluorescence analysis of the colocalization of SNAIL1 and DNMT1 in the nucleus of HCT116 cell. SNAIL1 (red signal) is distributed in discrete spots in the cell nucleus, and colocalizes with DNMT1 (green signal; arrow) in specific locations (yellow signal; arrow heads). The insert shows an enlarged view of the area of the region demarcated by the white square. Images are of 0.1-μm-thick sections in the z-plane obtained by confocal microscopy. Bar: 5 μm. (B) Extended biomolecular fluorescence complementation assays (ExBiFC) to demonstrate the interaction of DNMT1 and SNAIL1 in the cell nucleus. DNMT1 was tagged with red fluorescent protein (RFP) fused to the C-region of the yellow fluorescent protein (C-YFP) while SNAIL1 was tagged with cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) fused to the N-region of YFP (N-YFP). Both constructs were expressed in HCT116 cells. Interaction of DNMT1-RFP and SNAIL1-CFP entailed the association of C- and T-regions of YFP and was revealed by the yellow emission of the whole protein. Upper panels: Only cells expressing DNMT1-RFP+C-YFP and SNAIL1-CFP+N-YFP showed the emission of N+C-YFP (yellow arrowheads). Cells expressing DNMT1-RFP+C-YFP but not SNAIL1-CFP+N-YFP did not show yellow emission (white arrowheads). Bars: 10 μm. Lower panels: Enlarged images showing cells expressing DNMT1-RFP+C-YFP and SNAIL1-CFP+N-YFP. Both tagged proteins showed a homogeneous distribution pattern in the cell nucleus. In contrast, the yellow emission corresponding to the N+C-YFP fusion was located in discrete regions of the nuclear compartment. Bars: 5 μm.

DISCUSSION

The existence of functional roles for DNMT1 independent of its catalytic activity as a DNA methylating enzyme is a provocative but difficult to prove hypothesis. The ideal aprioristic system to analyze the non-catalytic function of DNMT1 (and, by extension, of any other enzyme) is a knockin of a catalytically inactive enzyme. However, for this approach to be unequivocally informative the complete elimination of the endogenous full-length enzyme is formally required, since all the non-catalytic domains of the endogenous protein can unmask the effects of the non-catalytic domains of the exogenous mutant protein. Unfortunately, such an approach is unattainable in the case of DNMT1, since deletion of this protein inevitably results in cell death and this effect is not reversed by the introduction of non-catalytic domains of DNMT1. In these conditions, the use of a cell line expressing a mutant form of DNMT1 lacking PCNA and DMAP1 domains can be consider as a valid system to investigate the role of both domains in different cellular processes. Herein, we have specifically investigated the SNAIL1-dependent regulation of E-cadherin, an event that occurs in a DNA methylation-independent context in these cells.

We have shown that disruption of the PCNA and DMAP1 domains of DNMT1 protein in human HCT116 cells induces significant repression of the E-cadherin gene. We have demonstrated that SNAIL1 is required for E-cadherin repression in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells. A strong interaction of SNAIL1 with the E-cadherin promoter, associated with transcriptional repression, is induced in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells. E-cadherin repression in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells promotes β-catenin nuclear translocation and activation of β-catenin-dependent transcription, indicating that DNMT1 is a potential modulator of Wnt/β-catenin signaling and may be directly involved in epithelial–mesenchymal transitions.

E-cadherin downregulation in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells occurs in the absence of changes in the DNA methylation patterns of E-cadherin or SNAIL1 promoters. Modulation of gene activity through DNMT1 in the absence of changes in the pattern of DNA methylation has been described in other cell systems (28,29). The basis for this mechanism of gene repression mediated by DNMT1 is the interaction with, and recruitment of, histone modifiers, such as HDACs, to specific DNA sequences, and the subsequent shift of chromatin structure to a closed, inactive conformation. Consistent with this explanation, our previous work indicated that SNAIL1 interacts with HDAC1/2 to repress the E-cadherin promoter (20). Similarly, we have reported here that HDAC1, in parallel with SNAIL1, is associated with the E-cadherin promoter in DNMT1ΔE3−6 cells, but not in DNMT1+/+ or DNMT3−/− cells, in which E-cadherin is strongly expressed.

Taken as a whole, these observations are consistent with a model in which DNMT1 can modulate the activity of the E-cadherin promoter in a DNA methylation-independent manner. This could happen by direct interaction with SNAIL1 through the N-terminal region, which would thereby prevent the association of this transcriptional repressor with the E-cadherin promoter. It could also result from the interaction with HDAC1/2, which would prevent association of these chromatin modifiers with SNAIL1 and, consequently, with the E-cadherin promoter. It is even possible that both of these actions are combined in a dual mechanism. Thus, the presence of DNMT1 in epithelial cells may be associated with E-cadherin expression and cell survival, while N-terminal or complete deletion of DNMT1 is associated with E-cadherin loss and subsequent activation of epithelial–mesenchymal transition or cell death programs. This is highly consistent with the central role of E-cadherin in the two processes.

Interestingly, the expression of mouse Dnmt1 isoforms resulting from alternative splicing in the N-terminal region of the Dnmt1 gene, corresponding to exons 2–4, is a relatively common phenomenon that occurs during muscle differentiation (30) and oogenesis (31), as well as in germinal (32,33) and somatic (34) adult tissues. Isoforms of human DNMT1 affecting exons 2–4 have also been detected in adult cells and tissues (35,36). In this context, it is reasonable to speculate that alternative splicing that affects N-terminal exons of the DNMT1 gene in mammals and thereby accurately controls PCNA and DMAP1 domain expression can be an important element in the regulation of DNMT1 function. In the same way, proteins interacting with the DMAP1 and PCNA domains of DNMT1 may have important roles in regulating DNMT1 activity.

In conclusion, the results presented here indicate that DNMT1 can have biological functions in the cell nucleus that are independent of its enzymatic activity. These functions are achieved mainly through the establishment of a broad network of interactions with different nuclear factors. In support of this, we report a novel mechanism by which DNMT1 can maintain active gene expression of E-cadherin after inhibitory binding to a complex of SNAIL1 containing repressor proteins. Our results highlight the importance of DNMT1 activity in the absence of DNA methylation, enlarging the concept of epigenetic modes of gene expression regulation.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

MEC (SAF2008-00609 to J.E.); MEC (SAF2007-63051 and Consolider CSD2007-00017); EU (MRTN-CT-2004-005428 to A.C.); MEC (SAF2004-07729, Consolider CSD2006-49); EU (FP7-CANCERDIP-2007-200620 to M.E.); MEC (SAF2010-19152 to J.R.). M.E. is an ICREA Research Professor. J.E. is a Ramon y Cajal Program researcher (MICIIN). Funding for open access charge: Consolider CSD2006-49 (Grant of the Spanish Science Governmental Department).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr M. Rossner (Max-Planck-Institute of Experimental Medicine, Goettingen, Germany) for the availability and advice with the SPLIT-TEV technique, and Vanesa Santos and Ana Villar-Garea for their excellent technical collaboration.

REFERENCES

- 1.Espada J, Ballestar E, Santoro R, Fraga MF, Villar-Garea A, Nemeth A, Lopez-Serra L, Ropero S, Aranda A, Orozco H, et al. Epigenetic disruption of ribosomal RNA genes and nucleolar architecture in DNA methyltransferase 1 (Dnmt1) deficient cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2191–2198. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Espada J, Esteller M. DNA methylation and the functional organization of the nuclear compartment. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2009;21:238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bestor TH. The DNA methyltransferases of mammals. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:2395–2402. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.16.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen T, Li E. Structure and function of eukaryotic DNA methyltransferases. Curr. Top Dev. Biol. 2004;60:55–89. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(04)60003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li E, Bestor TH, Jaenisch R. Targeted mutation of the DNA methyltransferase gene results in embryonic lethality. Cell. 1992;69:915–926. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90611-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhee I, Jair KW, Yen RW, Lengauer C, Herman JG, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Baylin SB, Schuebel KE. CpG methylation is maintained in human cancer cells lacking DNMT1. Nature. 2000;404:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/35010000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egger G, Jeong S, Escobar SG, Cortez CC, Li TW, Saito Y, Yoo CB, Jones PA, Liang G. Identification of DNMT1 (DNA methyltransferase 1) hypomorphs in somatic knockouts suggests an essential role for DNMT1 in cell survival. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:14080–14085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604602103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spada F, Haemmer A, Kuch D, Rothbauer U, Schermelleh L, Kremmer E, Carell T, Langst G, Leonhardt H. DNMT1 but not its interaction with the replication machinery is required for maintenance of DNA methylation in human cells. J. Cell Biol. 2007;176:565–571. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200610062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Espada J, Ballestar E, Fraga MF, Villar-Garea A, Juarranz A, Stockert JC, Robertson KD, Fuks F, Esteller M. Human DNA methyltransferase 1 is required for maintenance of the histone H3 modification pattern. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:37175–37184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404842200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Araujo FD, Croteau S, Slack AD, Milutinovic S, Bigey P, Price GB, Zannis-Hadjopoulos M, Szyf M. The DNMT1 target recognition domain resides in the N terminus. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:6930–6936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009037200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suetake I, Hayata D, Tajima S. The amino-terminus of mouse DNA methyltransferase 1 forms an independent domain and binds to DNA with the sequence involving PCNA binding motif. J. Biochem. 2006;140:763–776. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvj210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen T, Hevi S, Gay F, Tsujimoto N, He T, Zhang B, Ueda Y, Li E. Complete inactivation of DNMT1 leads to mitotic catastrophe in human cancer cells. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:391–396. doi: 10.1038/ng1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milutinovic S, Brown SE, Zhuang Q, Szyf M. DNA methyltransferase 1 knock down induces gene expression by a mechanism independent of DNA methylation and histone deacetylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:27915–27927. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312823200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Damelin M, Bestor TH. Biological functions of DNA methyltransferase 1 require its methyltransferase activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:3891–3899. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00036-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Batlle E, Sancho E, Franci C, Dominguez D, Monfar M, Baulida J, Garcia De Herreros A. The transcription factor snail is a repressor of E-cadherin gene expression in epithelial tumour cells. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2000;2:84–89. doi: 10.1038/35000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cano A, Perez-Moreno MA, Rodrigo I, Locascio A, Blanco MJ, del Barrio MG, Portillo F, Nieto MA. The transcription factor snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2000;2:76–83. doi: 10.1038/35000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rhee I, Bachman KE, Park BH, Jair KW, Yen RW, Schuebel KE, Cui H, Feinberg AP, Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, et al. DNMT1 and DNMT3b cooperate to silence genes in human cancer cells. Nature. 2002;416:552–556. doi: 10.1038/416552a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olmeda D, Jorda M, Peinado H, Fabra A, Cano A. Snail silencing effectively suppresses tumour growth and invasiveness. Oncogene. 2006 doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caplen NJ, Parrish S, Imani F, Fire A, Morgan RA. Specific inhibition of gene expression by small double-stranded RNAs in invertebrate and vertebrate systems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:9742–9747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171251798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng L, Baumann U, Reymond JL. An efficient one-step site-directed and site-saturation mutagenesis protocol. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bolos V, Peinado H, Perez-Moreno MA, Fraga MF, Esteller M, Cano A. The transcription factor Slug represses E-cadherin expression and induces epithelial to mesenchymal transitions: a comparison with Snail and E47 repressors. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:499–511. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perez-Moreno MA, Locascio A, Rodrigo I, Dhondt G, Portillo F, Nieto MA, Cano A. A new role for E12/E47 in the repression of E-cadherin expression and epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:27424–27431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100827200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shtutman M, Zhurinsky J, Simcha I, Albanese C, D'Amico M, Pestell R, Ben-Ze'ev A. The cyclin D1 gene is a target of the beta-catenin/LEF-1 pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:5522–5527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tetsu O, McCormick F. Beta-catenin regulates expression of cyclin D1 in colon carcinoma cells. Nature. 1999;398:422–426. doi: 10.1038/18884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peinado H, Ballestar E, Esteller M, Cano A. Snail mediates E-cadherin repression by the recruitment of the Sin3A/histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1)/HDAC2 complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:306–319. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.1.306-319.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wehr MC, Laage R, Bolz U, Fischer TM, Grunewald S, Scheek S, Bach A, Nave KA, Rossner MJ. Monitoring regulated protein-protein interactions using split TEV. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:985–993. doi: 10.1038/nmeth967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robertson KD, Ait-Si-Ali S, Yokochi T, Wade PA, Jones PL, Wolffe AP. DNMT1 forms a complex with Rb, E2F1 and HDAC1 and represses transcription from E2F-responsive promoters. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:338–342. doi: 10.1038/77124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rountree MR, Bachman KE, Baylin SB. DNMT1 binds HDAC2 and a new co-repressor, DMAP1, to form a complex at replication foci. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:269–277. doi: 10.1038/77023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aguirre-Arteta AM, Grunewald I, Cardoso MC, Leonhardt H. Expression of an alternative Dnmt1 isoform during muscle differentiation. Cell Growth Differ. 2000;11:551–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mertineit C, Yoder JA, Taketo T, Laird DW, Trasler JM, Bestor TH. Sex-specific exons control DNA methyltransferase in mammalian germ cells. Development. 1998;125:889–897. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.5.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaudet F, Talbot D, Leonhardt H, Jaenisch R. A short DNA methyltransferase isoform restores methylation in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:32725–32729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakai Y, Suetake I, Itoh K, Mizugaki M, Tajima S, Yamashina S. Expression of DNA methyltransferase (Dnmt1) in testicular germ cells during development of mouse embryo. Cell Struct. Funct. 2001;26:685–691. doi: 10.1247/csf.26.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin MJ, Lee TL, Hsu DW, Shen CK. One-codon alternative splicing of the CpG MTase Dnmt1 transcript in mouse somatic cells. FEBS Lett. 2000;469:101–104. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01254-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsu DW, Lin MJ, Lee TL, Wen SC, Chen X, Shen CK. Two major forms of DNA (cytosine-5) methyltransferase in human somatic tissues. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:9751–9756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bonfils C, Beaulieu N, Chan E, Cotton-Montpetit J, MacLeod AR. Characterization of the human DNA methyltransferase splice variant Dnmt1b. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:10754–10760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.10754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.