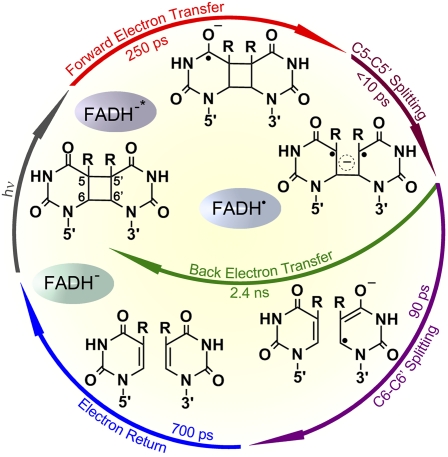

In 1949, Albert Kelner described a miraculous recovery of cells damaged by UV radiation when cells were exposed to soft sunlight (1). It was found later that an enzyme photolyase (PL) is involved in photoreactivation (2). With a paper in PNAS by Dongping Zhong, Aziz Sancar, and their colleagues (3) describing the real-time progression of the photoreactivation repair reaction observed by femtosecond time-resolved spectroscopy, the story of PL, originating 62 y ago, has come to be as complete as any research subject can be. They traced all the steps of the repair reaction, which involves electron transfer between the enzyme and DNA, the splitting of the thymine dimer on DNA, and the return of the electron back to the enzyme redox cofactor following the mechanism predicted earlier. The whole repair reaction takes less than a nanosecond to complete all the steps (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Complete photocycle of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer repair by DNA PL, with all time-resolved elementary steps of the elucidated molecular mechanism (3).

PL was identified over 50 y ago by Claud Rupert (2), and much of the subsequent work was done by Aziz Sancar (4) and his coworkers. Sancar was a student of Rupert in the early 1970s. By the end of the decade, he cloned the gene of the enzyme, purified it, and identified two chromophores of the enzyme: the light-absorbing MTHF (or sometimes HDF) and the redox cofactor FADH−. MTHF absorbs light and transfers the excitation to FADH−, which transfers an electron to the dimer, putting it on the antibonding orbital; the antibonding electron splits the dimer, after which the electron returns back to FADH. This scheme emerged by the end of the 1980s. However, neither the structure of the enzyme nor the molecular details of the hypothetical mechanism were known at that time.

The breakthrough into the molecular mechanism came in 1995, when the structure of an isolated enzyme was solved by Deisenhofer, Sancar, and coworkers (5). The structure brought the discussion of the mechanism to the atomistic level and allowed performance of the first computational studies, which provided further insights into the nature of the repair reaction.

The structure revealed, first of all, the position of two cofactors responsible for the repair reaction in the enzyme. Another feature discovered was that on the positively charged surface of the enzyme that obviously binds the DNA helix, there is an opening leading to a pocket in which the redox cofactor is located.

The conformation of the FADH− in the binding pocket of the protein was found to be unusual in that the molecule is folded in such a way that the adenine ring and that of the flavin are both exposed to the opening of the binding pocket, which extends to the surface of the protein and can communicate with the redox substrate (i.e., the thymine dimer). However, the dimer in the intact DNA structure was found to be well-folded into the interior of the helix, posing a puzzle as to how the redox cofactor can reach the substrate for an efficient electron transfer reaction. Because the structure of the complex of PL bound to the DNA was not known at that time, the field was open for hypotheses and speculations.

The structure immediately prompted molecular dynamics simulations to understand the missing pieces of the repair reaction mechanism. One theory group developed a docking algorithm that probed the rate of electron transfer between PL and DNA in complex models (6, 7). The reasoning was that the long-distance electron transfer is sensitive to the structure of the intervening medium (8), and the time scale of the electron transfer reaction was known to be in the range of 100 ps.

It was found that that the only way to understand the high rate of electron transfer was to consider structures with the dimer flipped out of the DNA helix. (Earlier, a similar hypothesis was put forward by Sancar and coworkers.) The simulations resulted in a well-defined structure in which the dimer was flipped out, sitting deep inside the binding pocket, and in hydrogen-bonded contact between the carbonyl oxygens of the dimer and the adenine moiety of FADH−. The found structure of the PL/T<>T dimer complex was intellectually appealing because it explained the presence of the deep cavity leading to FADH− cofactor, so perfectly matching the dimensions and properties of the dimer itself. Indeed, it would be surprising if nature had created such a special feature of the enzyme and not used it.

The well-defined structure determined in simulations suggested another intriguing feature of the electron transfer reaction by which the repair electron is passed from FADH− to the thymine dimer on DNA. The dimer was found to be most strongly coupled to the adenine moiety of FADH−. As a matter of fact, the structure of the complex suggested the FADH− cofactor is bent in the binding pocket in such a way as if to extend a hand (i.e., adenine moiety) to a possible binding partner. The problem, however, is that the initial location of the electron to be sent for the repair mission, even after excitation of FADH−, is still on the flavin part of the molecule. The simulation of the repair reaction suggested that the adenine can be used as a virtual stepping stone for the superexchange coupling between the dimer and the flavin. Superexchange, also known as tunneling, is a typical mechanism that nature uses to transfer electrons over long distances (8).

Thus, by the end of the 1990s, theory suggested much needed refinement of the picture, offering detailed predictions of the structure and mechanism of electron transfer. In addition, theory suggested some details of the dimer-splitting reaction itself (9). The ball was now in the experimental court.

The next major breakthrough came almost 5 y later, at the end of 2004. The group of Carell, Essen and coworkers (10) in Germany solved the structure of PL bound a stretch of DNA containing thymine dimer. The DNA is clearly seen as locally melted; the dimer is flipped out, sitting deep in the pocket of the redox cofactor, forming hydrogen bonds between carbonyl oxygens of the dimer and the adenine moiety of FADH−, precisely as theory predicted (6, 7), matching with atomic detail the predicted structure. It has been clearly confirmed that the adenine is playing an important role in binding, but is it also playing a role in the electron coupling between the donor and the dimer, as one theory predicted (6, 7), or the direct coupling is more important, as suggested by the another theory (11)? The crystal structure alone cannot answer this question. And what about the details of the dimer-splitting reaction itself?

A paper in PNAS by Zhong, Sancar, and their coworkers (3) appears to be putting all the remaining dots over the “i”s in the story of PL repair. Following the steps of their initial studies (12), and also early work of Bob Stanley's group at Temple University (13), they used femtosecond spectroscopy to monitor in real time all steps of the repair reaction, and by mutation of the key residues, they answer some essential questions posed previously.

The initial electron transfer to the dimer is seen to take 250 ps, for T<>T dimer, accelerating for U/T substitution; the ring opening occurs in two extremely fast steps, the first in less than a few picoseconds and the second on the 90-ps time scale. After the dimer is split, the electron returns back to FADH cofactor on the time scale of about 700 ps. Obviously, the back-reaction is slow on the time scale of dimer splitting, which allows the splitting repair to occur with high efficiency. Using different wavelengths of time-resolved spectra, Zhong, Sancar, and their coworkers (3) were able to monitor different components of the reaction, differentiating the donor, acceptor, and repair intermediates of the reaction.

The reaction is a direct transfer of the electron from FADH− to the dimer, forming a biradical state of the system (one on FADH• and another of the T<>T•−), and the data clearly show this. The reaction is so fast that, obviously, no side product is formed, despite the potential of the system to initiate other chemical modifications.

The reaction is sped up by the U/T substitution. The latter takes less space, and the dimer can bind more tightly; in addition, the redox potential of uracil is higher. The substitution can be made on a 3′-, or 5′-thymine, changing coupling to adenine. The results show that it is the distance and orientation, and hence the coupling to adenine, that are more sensitive to the reaction rate. Thus, adenine is involved; electron transfer appears to occur via an adenine intermediate step (i.e., the electron first jumps on adenine and only then to the dimer). However, if FADH− is excited without the dimer being bound, the excitation stays on the flavin, and does not go to adenine, indicating that the reduced state of adenine is higher in energy than that of the excited FADH−. How can that be?

One possibility is that the PL binding changes redox potential of the adenine moiety significantly and, after excitation, the electron jumps to adenine and then to the dimer; however, this is unlikely because the structure of FADH cofactor does not change significantly and, given the distance from the dimer, the electronic system of the adenine should not change much. The second possibility is that the electron passes adenine via quantum tunneling. In one quantum mechanical transition, it jumps from FADH− to the dimer, passing adenine as a tunneling medium. It is only wave properties of the electron that make possible such nonclassic transitions. It appears that it is this type of transition that takes place in the repair reaction. It is remarkable that such subtle wave and quantum properties of matter are at the basis of many fundamental biological mechanisms.

The major part of the DNA PL repair mechanism is now resolved both structurally and dynamically with unprecedented resolution. Some questions still remain, however. The superexchange/tunneling mechanism is convincing, but not without a question: Is there a more direct way to probe it? The back-transfer is slow: Why? Is it because of the Marcus inverted region slow-down effect or because the splitting reaction is initiated so quickly that the electron, as soon as it arrives to the dimer, is locked in a state that prevents back-transfer until the reaction is completely finished? Otherwise, the dimer would be left without the electron in an ill-defined state requiring high energy.

The repair of T<>T dimers is obviously only one, and the simplest, example of DNA repair. The most closely related system is the 6-4 pyrimidine dimer repair (14). This is already a much more complicated problem, because the reversal reaction involves much more complicated chemistry. However, as in the case of PL, a single electron manages to accomplish the incredible repair job. The crystal structure of the 6-4 repair enzyme was recently solved by the Carell group in Germany (15). However, much mechanistic work is yet to be done.

Much excitement in the field is fueled by an unexpected evolutionary connection of the PL repair enzyme to human cryptochromes, enzymes involved in regulation of the molecular clock of the organism (4). Obviously, a similar degree of detail in resolution of this process as in the PL story would be highly desirable. Much exciting work obviously lies ahead. The quantum aspect of these biological systems that manipulate individual electrons using their fundamental wave properties is most intriguing.

Remembering Erwin Schrödinger (16), it is hard not to be impressed by the molecular machines, such as PL; thinking of enzymes as individual cogs of some complicated mechanical system, the founder of quantum mechanics described them as follows:

…and the single cog is not of coarse human make, but is the finest masterpiece ever achieved along the lines of the Lord's quantum mechanics.

Acknowledgments

Work in my group is supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 054052 and National Science Foundation Grant 0646273 (to A.S.).

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 14831 of issue 36 in volume 108.

References

- 1.Kelner A. Effect of Visible Light on the Recovery of Streptomyces Griseus Conidia from Ultra-violet Irradiation Injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1949;35:73–79. doi: 10.1073/pnas.35.2.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rupert CS, Goodgal SH, Herriott RM. Photoreactivation in vitro of ultraviolet-inactivated Hemophilus influenzae transforming factor. J Gen Physiol. 1958;41:451–471. doi: 10.1085/jgp.41.3.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Z, et al. Dynamics and mechanism of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer repair by DNA photolyase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:14831–14836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110927108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sancar A. Structure and function of DNA photolyase and cryptochrome blue-light photoreceptors. Chem Rev. 2003;103:2203–2237. doi: 10.1021/cr0204348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park HW, Kim ST, Sancar A, Deisenhofer J. Crystal structure of DNA photolyase from Escherichia coli. Science. 1995;268:1866–1872. doi: 10.1126/science.7604260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stuchebrukhov AA, Antony J, Medvedev DM. Theoretical study of electron transfer between the photolyase catalytic cofactor FADH(-) and DNA thymine dimer. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:1057–1065. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medvedev D, Stuchebrukhov AA. DNA repair mechanism by photolyase: Electron transfer path from the photolyase catalytic cofactor FADH(-) to DNA thymine dimer. J Theor Biol. 2001;210:237–248. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2001.2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray HB, Winkler JR. Long-range electron transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3534–3539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408029102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrison CB, O'Neil LL, Wiest O. Computational studies of DNA photolyase. J Phys Chem A. 2005;109:7001–7012. doi: 10.1021/jp051075y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mees A, et al. Crystal structure of a photolyase bound to a CPD-like DNA lesion after in situ repair. Science. 2004;306:1789–1793. doi: 10.1126/science.1101598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prytkova TR, Beratan DN, Skourtis SS. Photoselected electron transfer pathways in DNA photolyase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:802–807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605319104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kao YT, Saxena C, Wang L, Sancar A, Zhong D. Direct observation of thymine dimer repair in DNA by photolyase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16128–16132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506586102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacFarlane AW, 4th, Stanley RJ. Cis-syn thymidine dimer repair by DNA photolyase in real time. Biochemistry. 2003;42:8558–8568. doi: 10.1021/bi034015w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J, et al. Dynamics and mechanism of repair of ultraviolet-induced (6-4) photoproduct by photolyase. Nature. 2010;466:887–890. doi: 10.1038/nature09192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maul MJ, et al. Crystal structure and mechanism of a DNA (6-4) photolyase. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:10076–10080. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schrödinger E. What Is Life? Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 1944. [Google Scholar]