Abstract

Numerous membrane importers rely on accessory water-soluble proteins to capture their substrates. These substrate-binding proteins (SBP) have a strong affinity for their ligands; yet, substrate release onto the low-affinity membrane transporter must occur for uptake to proceed. It is generally accepted that release is facilitated by the association of SBP and transporter, upon which the SBP adopts a conformation similar to the unliganded state, whose affinity is sufficiently reduced. Despite the appeal of this mechanism, however, direct supporting evidence is lacking. Here, we use experimental and theoretical methods to demonstrate that an allosteric mechanism of enhanced substrate release is indeed plausible. First, we report the atomic-resolution structure of apo TeaA, the SBP of the Na+-coupled ectoine TRAP transporter TeaBC from Halomonas elongata DSM2581T, and compare it with the substrate-bound structure previously reported. Conformational free-energy landscape calculations based upon molecular dynamics simulations are then used to dissect the mechanism that couples ectoine binding to structural change in TeaA. These insights allow us to design a triple mutation that biases TeaA toward apo-like conformations without directly perturbing the binding cleft, thus mimicking the influence of the membrane transporter. Calorimetric measurements demonstrate that the ectoine affinity of the conformationally biased triple mutant is 100-fold weaker than that of the wild type. By contrast, a control mutant predicted to be conformationally unbiased displays wild-type affinity. This work thus demonstrates that substrate release from SBPs onto their membrane transporters can be facilitated by the latter through a mechanism of allosteric modulation of the former.

Keywords: binding thermodynamics, periplasmic binding protein, secondary transporter, ABC transporter, replica-exchange metadynamics

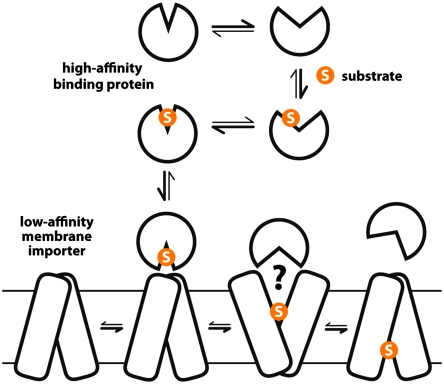

A variety of membrane transport systems rely on high-affinity, accessory binding proteins whose function is to sequester the substrate. These substrate-binding proteins (SBP) typically consist of two distinct globular domains, or lobes, separated by a deep binding cleft. Extensive structural and biophysical data (1–7) demonstrate that the binding and release mechanism of SBPs, generally referred to as “Venus flytrap,” entails an equilibrium in which the protein adopts two alternative conformations: one in which the binding cleft is open, allowing the substrate to bind, and another in which the two lobes close around the ligand, precluding its release.

SBPs have been identified in import systems driven by ATP hydrolysis (ABC) as well as by transmembrane ionic gradients (TRAP). The role of the SBP in these systems is not only to sequester the substrate but also to deliver it to the membrane transporter. Indeed, for the bacterial ATP-driven import systems of maltose, molybdate, and vitamin B12, crystal structures have revealed the SBP docked onto the perisplasmic face of the transporter domain (8–10). A widely accepted notion consistent with these structures is that ATP loading of the membrane transporter causes the SBP to revert to a conformation where the binding cleft is open, thus facilitating substrate release into a transporting pathway (11–14).

Although this mechanism is perfectly intuitive, its underlying premise has not been demonstrated directly. This premise is that the substrate-affinity of the SBP can be significantly diminished solely by stabilizing an open-like conformation, so that the substrate may be readily unloaded onto a low-affinity binding site in the transporter.

A number of experimental observations justify the need to assess this principle. For example, in the aforementioned maltose transport system, competitive binding of a nonconserved periplasmic loop from the transporter (MalG) to the SBP binding cleft is apparently associated with substrate release (10, 15). Thus, this structure does not clarify whether opening of the SBP is sufficient; in fact, it suggests the opposite. Moreover, crystallographic studies have shown that substrate-bound SBPs may exist in both the closed and open states (16–18). This implies that the binding affinity of the open state is certainly not negligible and raises the question of how much the closure step actually contributes to the total binding free energy. In fact, available biophysical studies of the open-closed equilibrium of unliganded SBPs in solution show the closed state is either marginally populated or not accessible (3, 5), indicating that domain closure involves a significant free-energy cost in the form of conformational strain.

Here, we set out to assess directly the hypothesis that induced opening of the SBP, as it probably occurs upon interaction with the membrane transporter, enhances substrate release to a significant degree, even without direct perturbation of the SBP binding cleft. Our model system is TeaA, the ectoine-specific SBP (Kd ∼ 200 nM) of the TRAP transporter TeaABC, from Halomonas elongata DSM 2581T (19). Ectoine is an aspartate derivative, used widely among halophilic bacteria as a compatible solute. Upon hyperosmotic stress, H. elongata synthesizes ectoine de novo, but it is also able to import this solute using TeaABC (20). This is the only ectoine-specific transporter in H. elongata known to be activated by osmotic stress; therefore TeaABC seems to function as a recovery system for ectoine that leaks out of the cell (21).

The TeaABC system includes a transporter (TeaC) presumed to be Na+-coupled (22) and an accessory transmembrane protein of unknown function (TeaB). These are predicted to comprise 12 and 4 transmembrane helices, respectively, by analogy with other TRAP transporters in the DctPQM family (23). The structure of TeaA, however, was recently solved in complex with ectoine, at a resolution of 1.55 Å (24). The structure is reminiscent of the SBPs of other TRAP and ABC transport systems; the characteristic α/β lobes adopt a closed conformation around the ectoine-binding cleft.

To assess the principle of allosteric modulation of the substrate affinity of this SBP, we have first resolved its atomic structure in the ligand-free state by X-ray crystallography. This structure reveals a pronounced domain rearrangement and opening of the binding cleft, relative to the substrate-bound state. Based on these structures, quantitative molecular simulation methods are then employed to elucidate the microscopic mechanism by which the conformational dynamics of TeaA is coupled to ectoine binding. This insight allows us to design a triple mutation that impairs closure of the binding protein, while not directly affecting the substrate-binding site. This mutation therefore mimics the conformational change induced upon interaction with the transporter domain, TeaC. Calorimetric analysis support the multistep binding mechanism observed in the simulations and demonstrate how the conformational modulation induced by the mutation results in a marked reduction of the apparent affinity of TeaA for ectoine. Altogether, this data provides clear support for the view that substrate release from TeaA onto TeaC may be facilitated by the latter by stabilizing an open conformation of the former.

Results

Crystal Structure of TeaA in the apo State Adopts an Open Conformation.

The apo structure of TeaA (PDB entry 3GYY) was solved from crystals grown in the absence of ectoine, diffracting to 2.2-Å resolution (Table 1). Phases were determined by molecular replacement, using as a template the structure of ectoine-bound TeaA previously determined (PDB ID code 2VPN, 1.55-Å resolution).

Table 1.

X-ray data collection, refinement, and model statistics for apo TeaA

| Data collection | |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a (Å) | 74.7 |

| b (Å) | 65.0 |

| c (Å) | 121.5 |

| α (°) | 90 |

| β (°) | 91.5 |

| γ (°) | 90 |

| Space group | P21 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9999 |

| Resolution* (Å) | 10–2.2 (2.3–2.2) |

| Number of observed reflections* | 174,104 (21,201) |

| Number of unique reflections* | 57,867 (7,165) |

| Completeness* (%) | 97.3 (97.8) |

| I/σ* (I) | 8.03 (2.22) |

| Rmeas*,† (%) | 21.4 (90.0) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 2.2 |

| Rwork (%)† | 21.7 |

| Rfree (%)† | 28.4 |

| Number of protein atoms | 9,825 |

| Number of solvent molecules | 214 |

| Number of zinc ions | 41 |

| rmsd from ideal bond length (Å) | 0.005 |

| rmsd from ideal bond angles (°) | 0.817 |

| Average B-factor model atoms (Å2) | 34.5 |

| Wilson B-factor (Å2) | 37.4 |

| Ramachandran plot favored (%) | 97.3 |

| Ramachandran plot allowed (%) | 2.4 |

| Ramachandran plot disallowed (%) | 0.3 |

*Data in parentheses correspond to the highest-resolution shell.

†R factors are defined according to ref. 53; 2% of the total reflections were used to compute Rfree.

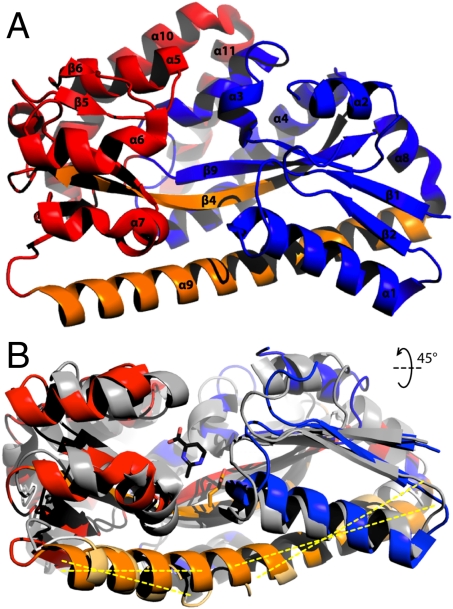

In the apo state, TeaA adopts a new open conformation that reveals a pronounced cleft between the N-terminal domain (β1-β3, β9, and α1-α4, α8) and the C-terminal domain (β5-β8, β10 and α5-α7, α10-α11) (Fig. 1A). In comparison to the ectoine-bound closed state, the N and C lobes are rotated by about 30° relative to each other, around a hinge point approximately located at position Glu121/Gly122 in β4 (Fig. 1B); this β-strand, together with helix α9, connects both domains (Fig. 1A). Residues involved in ectoine coordination in the bound structure become up to 4 Å further apart in the apo state (Fig. 2, Insets), although their conformation shows only subtle changes. Trp188, which in the closed state forms a π-π interaction with ectoine (Fig. 2B, Inset), adopts an alternate rotamer in the apo structure, so as to interact with Phe187 instead (Fig. 2A, Inset). Glu9, which together with Arg144, participates in the ionic coordination of ectoine, interacts in the apo state with one of the seven cocrystallized Zn2+ ions, present in the crystallization buffer. However, the most remarkable change in TeaA upon release of ectoine is the straightening of helix α9, which in the closed state is partially unfolded and noticeably kinked at the position of Lys247/Gly248/Leu249 (Fig. 1B). As mentioned, this long helix extends across the protein, flanking both N- and C-terminal domains and is conserved in the SBPs of other TRAP transporters (7, 22, 25).

Fig. 1.

(A) X-ray structure of the open apo-state of TeaA. The structure was solved to 2.2-Å resolution by molecular replacement, using the structure of ectoine-bound TeaA (PDB ID code 2VPN) as a template for phasing. The asymmetric unit comprises four TeaA monomers, about 250 solvent molecules and 41 Zn2+ ions. Residues 44 to 47 and 311 to 316 in the C-terminal domain are disordered. The long helix α9 and strand β4, depicted in orange, extend across TeaA, flanking both N- (blue) and C- (red) terminal domains. (B) In the open state, the flanking helix α9 (orange) is fully formed, while in the bound state it unravels around Gly248/Leu249. As the N- and C-terminal domains close around the substrate, helix α9 becomes noticeably kinked.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the apo (A) and ectoine-bound (B) structures of TeaA. Protein and substrate are represented as cartoons and sticks, respectively. Water molecules are shown as dotted spheres, and Mg2+ and Zn2+ as solid spheres in cyan and green, respectively. The apo-protein adopts an open conformation, in which the N-terminal (blue) and C-terminal (red) lobes are further away than in the ectoine-bound structure. (Insets) Architecture of the ligand-binding sites in the apo (A) and ectoine-bound (B) structure of TeaA. Ectoine-binding residues in the N domain are shown in blue, and those in the C domain in red, with ectoine in black. The dotted line indicates the distance between the Cβ atom of Trp167 and the Cε1 of Phe209 in the two structures. These atoms are about 4 Å further apart in the apo-structure compared to the ectoine-bound structure.

Calculated Free-Energy Landscapes Reproduce Expected Conformational Equilibrium.

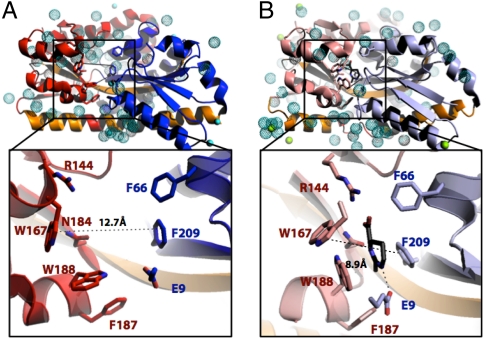

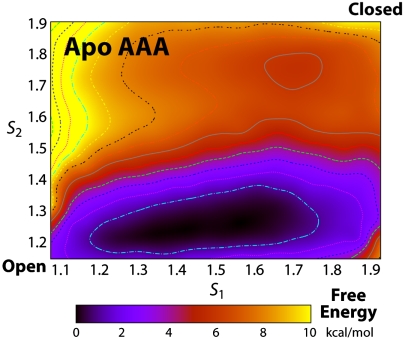

Based on the crystal structures of TeaA in the apo and ectoine-bound states, we sought to identify a mutation that would trap the protein in an open conformation, or at least impair its closure upon ectoine binding, without perturbing the binding site itself. To do so, we set out to obtain microscopic characterization of the process of substrate binding, and its influence on the conformational equilibrium of the protein, using atomically detailed molecular dynamics simulations (Fig. 3A). Specifically, we employed the bias-exchange metadynamics (BE) method (26–28), to derive quantitative information on the conformational freedom of the protein, in the form of free-energy landscapes (see Materials and Methods).

Fig. 3.

(A) All-atom molecular simulation model of TeaA. The system comprises the protein (and ectoine), approximately 12,000 TIP3P water molecules, 54 Na+, and 20 Cl- ions (approximately 100 mM plus counterions), enclosed in a truncated-octahedron periodic box. Glu121 is set in the protonated state. Wild-type and mutant simulation systems, in the apo or bound states, are based on the X-ray structures; these were constructed through a series of energy minimizations and constrained dynamics of the protein and its environment. (B) Conformational free-energy landscapes for the apo and ectoine-bound states, obtained from bias-exchange molecular dynamics simulations. Contours are plotted in increments of 1 kcal/mol. The statistical error in these landscapes is discussed in the SI Appendix, Supplementary Materials.

BE simulations were thus carried out for wild-type TeaA, in the apo and substrate-bound states. The resulting free-energy landscapes in each case are shown in Fig. 3. In these representations, the free energy is plotted as a function of two collective variables, or reaction coordinates, that describe the conformational state of the protein; S1 reports on the global motions of the N- and C-terminal lobes, while S2 is a specific descriptor of the degree of bending of helix α9. The apo and ectoine-bound conformations observed by X-ray crystallography correspond to S1 = S2 = 1, and S1 = S2 = 2, respectively.

This energetic analysis confirms the expectation that in the apo state the protein preferably adopts an open conformation. However, it also reveals that conformational fluctuations leading to partial closure of the N and C lobes are energetically feasible even without the substrate (reflected in the broad shallow minimum at S1 < 1.7 and S2 ∼ 1.2). Complete closure, however, entails a significant energy cost. The closed conformation seen in the ectoine-bound X-ray structure appears here to fall in a second, meta-stable minimum, whose free energy is approximately 3 kcal/mol higher than that of the open-like conformations (it is thus less than 1% probable).

In the ectoine-bound state, however, this energy landscape is drastically reshaped; as may be expected, the closed conformation becomes the most probable. Nonetheless, the computed free-energy difference relative to the semiopen conformations is only about -2 kcal/mol. Given that the binding free energy of ectoine is approximately -10 kcal/mol (Kd ∼ 200 nM 100 nM), this result implies that binding to the open conformation reflects most of the energetic gain upon association. Nonetheless, this result also suggests that by impairing the closure step (or by stabilizing the open conformation), a significant reduction in the affinity of TeaA could be in principle accomplished.

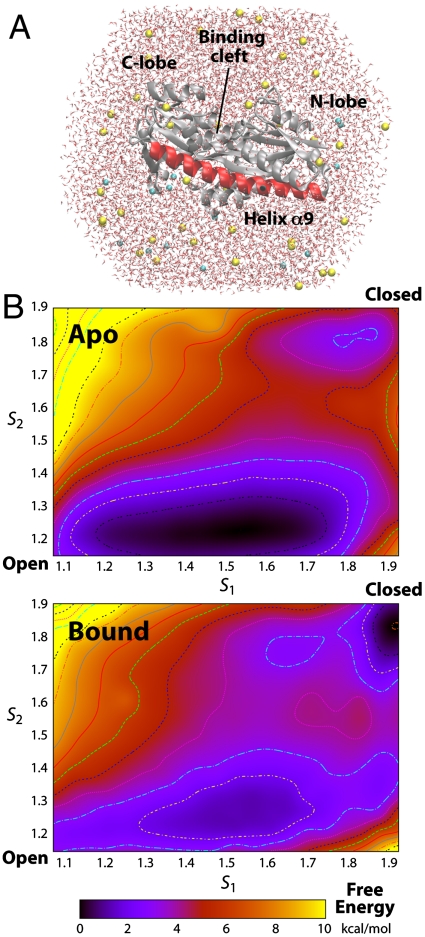

Simulations Indicate Complete Substrate Coordination Precedes Closure.

Further analysis of the BE simulation of TeaA in the presence of ectoine permits to characterize the interplay between substrate recognition and conformational change. To do so, additional collective variables are considered that describe the distance, orientation, and contacts between ectoine and the binding cleft, in addition to those pertaining to the conformational change in TeaA (see SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods). Classification of the ensemble of conformations explored during the simulation according to this expanded set of variables (via clustering, free-energy ranking and kinetic modeling) (27) reveals a pathway of connected states between a transient configuration in which ectoine is in the vicinity of the protein, but disengaged from the binding cleft, and another that corresponds to the ectoine-bound structure revealed experimentally.

The free energy along the pathway and a few representative configurations are shown in Fig. 4. In the first step, ectoine has few direct contacts with TeaA (there are approximately 14 water molecules within 4 Å; SI Appendix, Table S1), which is in an open conformation with helix α9 folded and straight. As expected the free energy decreases as the substrate enters the binding pocket and hydrophobic and electrostatic contacts are formed (e.g., with Phe66 and Glu44). These transient contacts help to orient ectoine so as to enable its interaction with the conserved Arg144, early on in the binding reaction. Transient interactions are also formed with Asn184 and Glu9, which is in this state still partially disengaged from Glu121 and is therefore more dynamic (SI Appendix, Table S1). Meanwhile, additional hydrophobic interactions with Trp167, Trp188, Phe66, and Phe209 contribute to further stabilize ectoine binding. Importantly, Trp188 is seen to change its rotamer (as seen in the X-ray structures), thus allowing ectoine to further penetrate into the binding cleft.

Fig. 4.

Microscopic mechanism of ectoine recognition by TeaA. Representative snapshots of configurational clusters along the binding reaction are depicted, highlighting the side chains involved in direct ectoine contacts as well as the fold of helix α9 and the overall protein conformation (water, ions, and most side chains are omitted for clarity). The calculated free energies of the corresponding clusters are also plotted. The connectivity between this clusters is established based on their characteristic free energy and observed transitions during the bias-exchange simulations (see SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods).

At this stage (state 3 in Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Table S1), the coordination of ectoine within the binding cleft is mostly complete, and yet TeaA remains in a semiopen conformation with helix α9 still completely folded. This is, however, a metastable state. In subsequent steps the hydrophobic side chains around ectoine become more compact, while the substrate becomes largely dehydrated; the interaction with Glu9 more persistent, as this engages the protonated Glu121 and become conformationally locked. These changes are concurrent with the closure of the N and C lobes around the binding cleft and the formation of direct interactions between them (SI Appendix, Table S1). However, the two protein domains do not fully interact until the unfolding and bending of helix α9 occurs, in the last steps. According to our analysis, the final state of the pathway (state 5 in Fig. 4), which closely resembles the ectoine-bound X-ray structure, ranks as the lowest in free energy.

This series of events underscore the dynamical nature of the binding process when viewed at the microscopic level, whereby initial local structural adaptations facilitate recognition prior to larger-scale conformational changes. More specifically, these insights suggest that mutations that increase the stability of helix α9 should not have a major effect on the ability of TeaA to coordinate ectoine. However, by hindering the last steps of the binding reaction, such mutation will preclude some of the energetic gain upon binding; that is, the binding affinity of TeaA would be diminished.

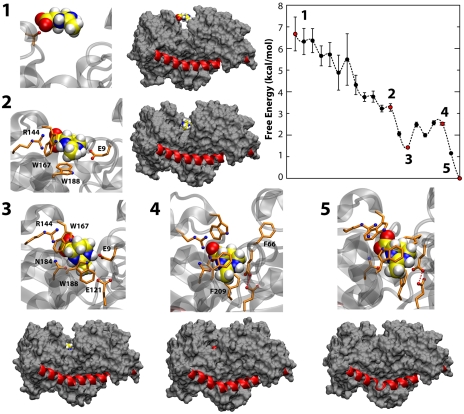

A Triple-Alanine Mutation in α9 Biases TeaA Toward the Open Conformation.

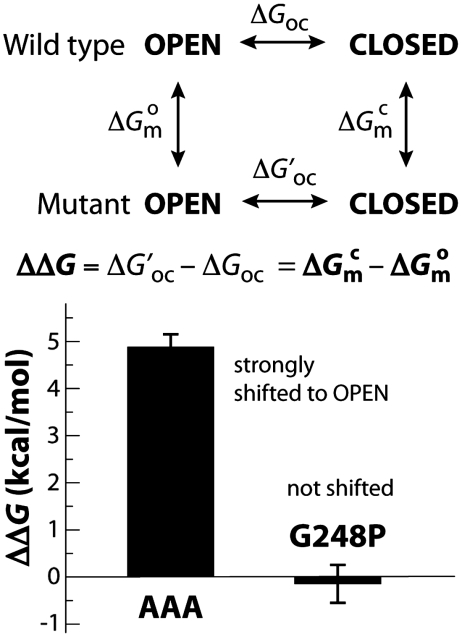

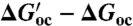

Among all natural amino acids, alanine has the greatest propensity to form α-helical segments (29, 30). Therefore, we reasoned that a triple mutation of G248, L249, and S250 to alanine should hinder the bending of helix α9 upon ectoine binding; by stabilizing the open conformation of TeaA, the mutation would thus mimic the presumed allosteric effect of TeaBC, the membrane transporter. To examine and substantiate this hypothesis further, we first carried BE molecular dynamics simulations of the apo AAA mutant, analogous to those presented above for the wild type. The corresponding free energy as a function of S1 and S2 is shown in Fig. 5. This landscape clearly shows that closed conformations with a kinked helix α9 are much more disfavored in the mutant than in the wild type (4–5 kcal/mol), relative to those in which the helix is straight and the N and C lobes are open. A second type of calculation, using the so-called alchemical free-energy perturbation method, confirmed this marked shift in the intrinsic conformational dynamics of TeaA. Here, the free-energy cost or gain upon triple mutation (and back to wild type) was computed for the apo/open and bound/closed states (Fig. 6). The agreement between the resulting ΔΔG (approximately 5 kcal/mol) and the BE metadynamics calculation implies great confidence in the prediction that this triple mutant will be strongly biased toward the open conformation. Indeed, the bias imposed by the mutation (toward the open state) is comparable in magnitude with that by substrate binding (toward the closed state). This indicates that the closed conformation captured by ectoine-bound X-ray structure would not be normally attainable for the mutant and that closure of the N and C domains upon ectoine binding would be, at most, transient. In summary, the calculations support the notion that the conformational bias imposed on TeaA by the triple helix mutation is, at least qualitatively, reminiscent of that presumed for the membrane transporter. From this energetic analysis, we also anticipate that the binding affinity of the mutant will be significantly reduced.

Fig. 5.

Conformational free-energy landscape for apo TeaA after triple Ala mutation of G248, L249, and S250 in helix α9, computed as those in Fig. 3. Contours are plotted in increments of 1 kcal/mol.

Fig. 6.

Shift in the open-to-closed equilibrium of TeaA upon mutation of helix α9. The change upon mutation in the free-energy difference between the closed and open conformations ( ) is equivalent to the difference in the “free energy of mutation” of each of these states (

) is equivalent to the difference in the “free energy of mutation” of each of these states ( ); these differences may be computed using alchemical-perturbation free-energy calculations (see SI Appendix, Supplementary Material). The calculated ΔΔG values for the G248A/L249A/S250A (AAA) and G248P mutants can be interpreted as an estimate of the conformational bias induced by the mutation, relative to the wild type.

); these differences may be computed using alchemical-perturbation free-energy calculations (see SI Appendix, Supplementary Material). The calculated ΔΔG values for the G248A/L249A/S250A (AAA) and G248P mutants can be interpreted as an estimate of the conformational bias induced by the mutation, relative to the wild type.

TeaA Has a Much Diminished Binding Affinity if Biased Toward the Open State.

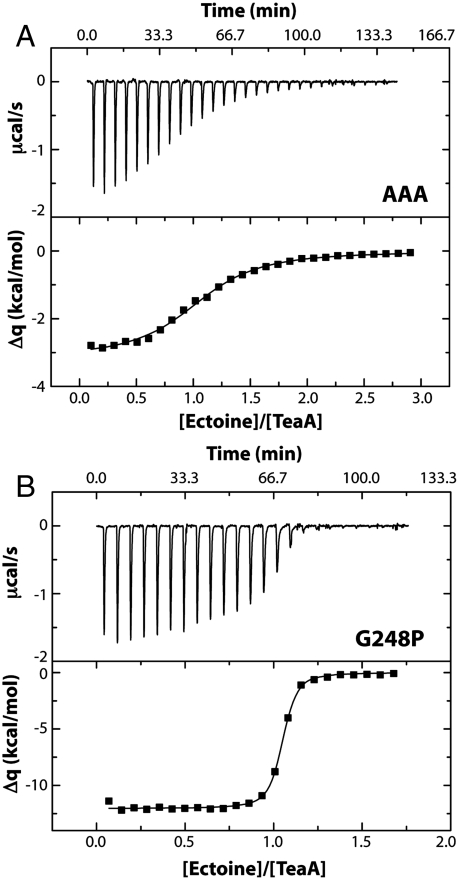

To conclusively assess whether a significant inhibition of the TeaA affinity for ectoine may be induced allosterically, isothermal tritration calorimetry measurements were carried out for the triple-Ala mutant, and compared with analogous calorimetric titrations for the wild type, reported previously (24); the data is given in Table 2. The AAA mutant exhibits a significantly lower affinity (100-fold), with a dissociation constant Kd of 10-5 M-1 (Table 2). A typical titration is shown in Fig. 7A. The characteristic saturation behavior observed for the wild type (24) is not observed here. The enthalpy change is negative, but its numeric value is markedly lower than in the wild type (i.e., ΔΔH ∼ 8 kcal/mol). Importantly, this change in the enthalpy of binding translates only in part to the total binding free energy, ΔΔG ∼ 2.3 kcal/mol. This is because the entropy change upon binding is more positive in the mutant, and therefore TΔΔS ∼ 6 kcal/mol (see also SI Appendix, Supplementary Materials). This enthalpy-entropy compensation may seem surprising, because the mutation is far from the ectoine-binding cleft. However, inspection of the computed free-energy landscapes in Figs. 3 and 5 indeed suggests that the ectoine-bound state will be more conformationally variable in the mutant than in the wild type, precisely because the fully closed state (in which the enthalpy of the protein-substrate complex is maximally optimized) cannot be achieved. In summary, this calorimetric analysis is consistent with the simulated conformational effect of the triple Ala mutation of helix α9; it also demonstrates that the binding affinity of TeaA in an open-like conformation is much weakened, possibly to a similar extent as that required for ectoine release onto the transporter domain.

Table 2.

Thermodynamics of ectoine binding to TeaA and its mutants at 25 °C

| TeaA | Stoichiometry | Dissociation constant Kd [M] | Free energy change ΔG [kcal/mol] | Enthalpy change ΔH [kcal/mol] | TΔS [kcal/mol] | Entropy change [cal/(mol K)] |

| Wild type* | 1.0 | 1.9 × 10-7 | −9.2 | −11.5 | −2.4 | −7.9 |

| G249P mutant | 1.02 ± 0.05 | (6.3 ± 1.5) × 10-8 | −9.8 ± 0.2 | −12.1 ± 0.2 | −2.3 ± 0.2 | −7.6 ± 0.8 |

| AAA mutant | 1.05 ± 0.07 | (1.0 ± 0.1) × 10-5 | −6.8 ± 0.1 | −3.3 ± 0.1 | 3.6 ± 0.1 | 12 ± 0.5 |

*According to the data previously reported in ref. 24, rounded and errors omitted. A detailed discussion of the results can be found in the main text and in SI Appendix, Supplementary Materials.

Fig. 7.

Calorimetric titrations at 25 °C of (A) 117 μM TeaA mutant AAA by adding 28 × 5 μl 5 mM ectoine in 50 mM sodium phosphate at pH 7.3; and (B) 42 μM TeaA mutant G248P by adding 23 × 4 μl 1 mM ectoine, same medium.

The AAA Mutation in α9 Does Not Perturb the Structure of the Substrate-Binding Site.

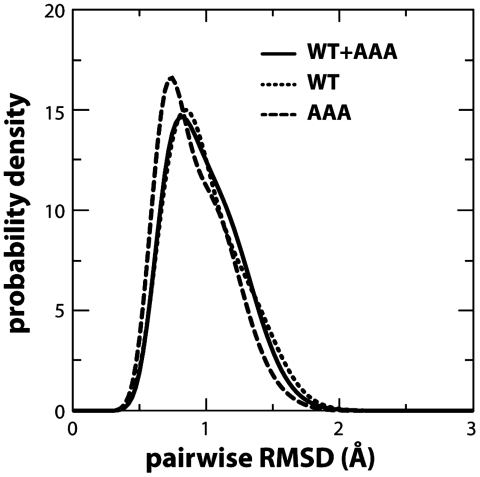

To rule out that the proposed allosteric effect of the AAA mutation is instead caused by a direct perturbation of the binding cleft, we prepared two additional molecular dynamics simulations of wild-type and mutant TeaA in the apo state and carried them out continuously up to 1 μs each. As shown in Fig. 8, the simulations reveal no statistically significant variation either the structure or the dynamics of the binding site upon mutation. This result is consistent with the fact that the hinge in α9 affected by the mutation is more than 10 Å away from the binding site; as mentioned, helix α9 flanks both the N- and C-terminal lobes but is itself not part of the architecture of the binding cleft (Fig. 2).

Fig. 8.

Structural dynamics of the binding cleft in unbiased 1-microsecond simulations of wild-type TeaA and its AAA mutant. The protein conformations obtained in each simulation (snapshots taken at 20-ps intervals) were combined in a single ensemble and clustered based on pairwise similarity according to a global descriptor, namely the rmsd of the complete Cα trace of the protein (the cutoff difference within each cluster is 1 Å). Only clusters with a significant population (> 10%) were analyzed further. The variability of the structure of the binding cleft across all the snapshots in each cluster was then quantified, now using a local descriptor. This descriptor is the pairwise rmsd of a substructure that includes only the protein residues involved in ectoine coordination (N, C, Cα, Cβ, and Cγ atoms). Note that this local descriptor is not correlated with the global one used for clustering a priori, because the binding-cleft structure is defined by < 5% of the total number of residues in the protein. The curve in the plot labeled WT + AAA is a histogram of these rmsd values, combining all the pairs in each of the clusters. The characteristic variability in the binding-cleft structure among simulation snapshots is 0.97 ± 0.27 Å. To assess whether the AAA mutation has a direct influence on the structure of the binding cleft, the distribution was recomputed after removing from the analysis all the snapshots from the AAA simulation (labeled WT), or from the wild-type simulation (labeled AAA). As the figure demonstrates, these distributions are not significantly different from the one above. On average, the characteristic variability in the binding-cleft structure becomes 0.99 ± 0.28 Å and 0.91 ± 0.26 Å, respectively. In conclusion, this analysis shows that the AAA mutation does not directly perturb the structure of the binding cleft, even though it influences the global conformational dynamics of the protein (Fig. 5).

A Proline Mutant in α9 Is Conformationally Unbiased and Thus Has Wild-Type Affinity.

To further rule out that the AAA mutation in helix α9 somehow alters the structure of the binding site, we set out to evaluate a second mutant at this position whose effect on the substrate affinity ought to be only marginal. Specifically, we substituted Gly248 for proline; like glycines, prolines are known to facilitate the reversible bending of α-helices during protein function. We therefore reasoned that the bending of helix α9 upon ectoine binding would be unhindered by this substitution, in contrast to the AAA mutant. Thus, analysis of this mutant enables us to assess the possibility of a structural perturbation of the binding pocket.

The theoretical and experimental analyses of this control mutant are squarely consistent with the conclusions drawn in the previous sections. As shown in Fig. 6, free-energy perturbation calculations analogous to those carried out for the AAA mutant show that the open-to-closed equilibrium in G248P TeaA is only marginally biased toward the closed state. Accordingly, the measured binding affinity of this mutant is essentially unchanged (approximately threefold stronger), as are the individual thermodynamic parameters (Fig. 7B and Table 2). These results validate the notion that localized substitutions in helix α9 have a negligible effect on the structure of the binding cleft and therefore that the influence of these substitutions on the binding affinity is allosteric.

Discussion

ABC and TRAP import systems are distinct structurally and mechanistically but share a crucial dependence on accessory high-affinity binding proteins (SBPs), whose function is to capture the substrate from solution and to deliver it to the membrane transporter.

ABC transporters consist of two membrane-embedded subunits, which adopt alternate orientations with respect to one another. This change is driven by a tandem of nucleotide-binding domains, which bind and hydrolyze ATP on the cytosolic side. Substrate release from the SBP occurs at the other side of the membrane, after association of the binding protein with the transporter. The substrate is released into a crevice that is formed between the transmembrane domains in the outward-facing state of the transporter (14). TRAP transporters are likely to function as monomers, although by analogy with other secondary transporters, they probably consist of two structural repeats also capable of adopting outward and inward-open conformations. Na+ binding and release at either side of the membrane, rather than ATP, is believed to drive transport; however, the SBP most likely releases its substrate also into a pore formed between the repeats (22).

A basic question pertaining to the overall mechanism of SBP-dependent transporters is how substrate release from the high-affinity binding protein is triggered. That is to say, by which mechanism is the affinity of the SBP sufficiently reduced that the transporter domain can out-compete the SBP. A widely accepted and intuitive mechanism is that SBPs are forced into a conformation that is unable to retain the bound substrate when the associated transporter adopts an outward-facing state. Indeed, SBPs in ABC and TRAP transporters share a two-lobe architecture, with the binding cleft in between, and are known to undergo a transition from (mostly) open to (mostly) closed conformations upon substrate binding. It is therefore reasonable that substrate release would be facilitated when an SBP adopts an open-like conformation that preserves the contact interface with the outward-facing transporter.

The premise of this hypothetical allosteric mechanism is that the binding affinity of open-like states of SBPs is sufficiently weak. To our knowledge, however, this intuitive concept has not been conclusively demonstrated yet. A previous study of the Escherichia coli maltose binding protein demonstrated that bulky sequence substitutions in the “hinge” region between the two lobes strengthen its binding affinity, presumably because they bias the conformational dynamics of the protein toward the closed state (31–33). More recently, synthetic antibodies designed to select the closed state were reported to have a similar effect (34). However, the observed reduction in maltose affinity that could be accomplished through these approaches was modest. Moreover, the outward-facing crystal structure of the maltose transporter MalG in complex with this SBP shows that maltose release requires a periplasmic loop in MalG to “scoop” the substrate out of the binding cleft in the SBP. Importantly, this loop appears to be a unique feature of MalG, as it is not conserved in other ABC importers, and thus it is reasonable to question whether the maltose binding protein is in fact a representative case. Analysis of the SBP entries in the Protein Data Bank is also not conclusive, because structures of isolated, substrate-loaded SBPs have been reported in both open and closed states (16–18); and because in crystal structures of SBPs in complex with membrane transporters (other than the maltose system) the substrate is unfortunately absent. Thus, whether or not substrate release from high-affinity SBPs results from a conformational bias imposed by their associated membrane transporters clearly requires further investigation.

In this article we provide compelling evidence in support of the hypothesis that substrate release from SBPs can be indeed facilitated allosterically. We have specifically studied TeaA, the periplasmic binding protein of the TRAP ectoine-import system in Halomonas elongata. We first determined its atomic structure in the unliganded state, by X-ray crystallography. The structure reveals the expected opening of the binding cleft, relative to the ectoine-bound state that was reported previously. Less expected is the refolding of helix α9, which in the bound state is unwound around Gly248 and sharply bent. Among the TRAP-transporter SBPs of known structure, this is a distinct feature of TeaA; other SBPs, such as UehA or SiaP, also display a distortion of this helix in the substrate-bound state but not extensive unfolding (35, 36).

The structures of apo and ectoine-bound TeaA were then used as the basis for a quantitative simulation-based analysis of the conformational dynamics of the protein and the mechanism of substrate recognition. To validate our approach, we have illustrated how the computed conformational free-energy landscape of apo TeaA is drastically reshaped upon ectoine binding (Fig. 3). In the apo state, open-like conformations are by far the most probable, although the protein is still able adopt a closed conformation, albeit less frequently. This is consistent with theoretical and experimental studies for the maltose, ribose, and vitamin B12 SBPs (3, 37–39). The presence of ectoine in the binding cleft reverses this balance, and cleft opening is seen to have a very significant energy cost. The results of these “control” calculations are consistent with the conformational preferences reflected in the X-ray structures of TeaA and are also in keeping with modern views on the role of conformational dynamics in molecular recognition (40, 41).

Further analysis of our simulations suggested that substrate recognition occurs in two major steps (Fig. 4). After the first step, most of the ectoine-protein interactions are formed while TeaA remains in a semiopen conformation (SI Appendix, Table S1). The most prominent among these involves the conserved Arg144, which appears to be key to anchor the ligand. The second step involves the unwinding and bending of helix α9, as the N and C lobes close around the binding cleft, forming direct contacts with each other (SI Appendix, Table S1).

Close inspection of the ITC titrations of wild-type TeaA (24) and the wild-type-like G248P mutant reveals signs of a slow conformational change upon binding. Specifically, we noted that the time required for reaching thermal equilibration upon substrate addition increases toward the end of the titrations, both in the wild type (see figure 2 in ref. 24) and in G248P (Fig. 7B) but not in the AAA mutant (Fig. 7A). For example, the time constant of the decay in the last observable binding signals in the TeaA G248P titrations ranges between 20 and 40 s (see example in SI Appendix, Fig. S1), while in the AAA mutant the signal decay is always faster than the detection time. This broadening of the signal, revealed when the concentration of the apo protein becomes sufficiently small, indicates that the binding kinetics is slow and not diffusion-limited. A plausible explanation for this observation is that the complete binding reaction includes at least two steps, one of which corresponds to a rate-limiting conformational change.

It is worth noting that although fast single-step kinetics are common among SBPs, slow binding rates are not unprecedented, particularly in TRAP systems. Specifically, stopped-flow fluorescence measurements have demonstrated multistep processes also in DctP (42) and RRC01191 (43) the binding proteins for decarboxylate and pyruvate, respectively, in Rhodobacter capsulatus. The data were interpreted as indicating that these SBPs mostly adopt a closed conformation in the apo state, with substrate binding requiring a rare transition to the open state. However, the X-ray structure of apo TeaA (and of other SBPs too), and the simulations thereof, clearly show that open-like conformations are characteristic of the unliganded state. We therefore propose that, at least for TeaA, the slow binding rate is primarily due to the closure step after substrate recognition, which is hampered by the concomitant partial unfolding of helix α9. (Other factors may also contribute; for example, reorientation of Trp188 is required for correct ectoine coordination within the binding cleft). Consistently, the aforementioned SiaP displays simple bimolecular association kinetics (35), probably because the change in α9 upon substrate binding is less pronounced.

In any case, the specific insights derived for TeaA from the simulations and the ITC experiments enabled us to design a triple-alanine substitution that hinders the closure of the binding cleft, without perturbing its ability to coordinate ectoine. Independent calculations of the conformational free-energy landscape of the mutant protein (Fig. 5) and of the free energy of mutation (Fig. 6) clearly showed that the mutation induces a strong bias (4–5 kcal/mol) toward open-like conformations, by precluding the unwinding of helix α9. We therefore postulate that this mutation mimics the restraining effect presumably imposed on TeaA by the membrane transporter TeaC, in its outward-facing conformation.

Crucially, microcalorimetric analysis of this triple-alanine mutant revealed a 100-fold reduction in the affinity for ectoine, relative to the wild type (Fig. 7 and Table 2). In other words, simulations and experiments demonstrate that a membrane transporter could significantly enhance substrate release from its accessory high-affinity SBP solely by restricting its dynamical range to open-like conformations. In TeaA in particular, the effective binding affinity of this conformationally biased state seems to be sufficiently weakened to allow the outward-facing transporter to compete for the substrate.

Lastly, it should be noted that computations and experiments on a second mutant of helix α9 (glycine to proline) provided results that are both mutually supportive as well as consistent with the allosteric mechanism outlined above (Figs. 6 and 7 and Table 2). Specifically, free-energy calculations analogous to those carried out for the triple-alanine substitution predicted a negligible effect on the conformational equilibrium of TeaA, with respect to the wild type. Consistent with this, the thermodynamics of ectoine binding to this mutant are essentially unchanged.

Materials and Methods

Protein Crystallization, Data Collection, and Processing.

TeaA was synthesized and purified as previously described (24). Protein crystallization was achieved using the sitting-drop vapor-diffusion method after 6 mo incubation with mother liquor containing 100 mM Tris pH 8.0, 50 mM zinc acetate and 30% PEG[w/v] 3350. After flash-freezing the crystals in liquid nitrogen a dataset to 1.8 Å was collected in the X10SA beamline at the SLS. Data were processed and scaled with XDS and XSCALE (44) in the space group P21.

Structure Determination and Refinement.

The structure of apo-TeaA was solved by molecular replacement with PHASER (45), using the structure of the ectoine-bound TeaA as a template (24). However, each its two domains had to be used as separate search models to obtain a solution in PHASER. The Rfree and Rwork of the initial model were 39% and 34%, respectively. The model was further improved by iterative rounds of manual model building in COOT (46) and refinement in PHENIX (47). By using NCS restraints, TLS refinement, and SA the Rfree and Rwork could be improved to 22 and 28%, respectively. NCS restraints were imposed as strict for the main chain and loose for the side chains over the whole molecule except for residues 41 to 49. For simulated annealing in PHENIX, the starting temperature was 5,000 K; it was reduced by a cooling rate of 100 K/cycle to the final temperature of 300 K. For TLS refinement the protein was separated into seven groups, which were defined by TLSMD (48).

Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Free-Energy Calculations.

Three types of computer-simulation analyses were carried out, in every case based on an all-atom molecular dynamics simulations of TeaA and its substrate in solution (Fig. 3A): (i) bias-exchange metadynamics simulations of wild-type TeaA in the apo and ectoine-bound states, and of the triple Ala mutant of helix α9 (AAA) in the apo state; (ii) free-energy perturbation analysis of the AAA and the G248P mutations in the apo and ectoine-bound states; and (iii) unbiased, 1-microsecond simulations of apo TeaA, for the wild type and AAA mutant. The computations in i were carried out with GROMACS4/PLUMED (49, 50), to derive the conformational free-energy landscapes in Figs. 3 and 5; in total, these amount to approximately 1.5 microseconds of biased sampling time. The calculations in ii were carried out with NAMD 2.7 (51), to quantify the conformational influence of the AAA and G28P mutations, shown in Fig. 6; these simulations amount to approximately 300 ns in total. Lastly, the 1-microsecond trajectories in (3), also calculated with GROMACS4, were used to assess whether the AAA mutation directly influences the structure of the binding cleft (Fig. 8).

All calculations were carried out at a constant temperature of 298 K and a constant pressure of 1 bar, using the CHARMM22/CMAP force field (52); parameters for ectoine were obtained ab initio (see SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Short-range electrostatic and Lennard-Jones interactions were cut off at 1 nm; the PME method was used to treat long-range electrostatic interactions. A detailed description of the simulations and analysis thereof is provided in SI Appendix, Supplementary Materials section.

Microcalorimetry.

Microcalorimetric titrations were carried out at 25 °C employing a MicroCal MCS ITC instrument; all solutions were vacuum degassed. Because ectoine is zwitterionic, the ionic strength of the cell solutions was constant during the titrations. The heat of the dilutions, determined by carrying out suitable reference titrations, was therefore very low and could be neglected. The titrations were analyzed using a single-site model and evaluated with MicroCal software. The ectoine affinities are expressed as dissociation constants Kd (equal to the reciprocal association constant). The corresponding thermodynamic parameters, calculated according to the equation ln(1/Kd) = (ΔH - TΔS)/RT, refer to concentrations and represent apparent values characteristic of the applied medium. Protein concentrations have been determined employing the BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

See Author Summary on page 19457.

Data deposition: The structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 3GYY).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1112534108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Felder CB, Graul RC, Lee AY, Merkle HP, Sadee W. The Venus flytrap of periplasmic binding proteins: an ancient protein module present in multiple drug receptors. AAPS PharmSci. 1999;1:7–26. doi: 10.1208/ps010202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dwyer MA, Hellinga HW. Periplasmic binding proteins: A versatile superfamily for protein engineering. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:495–504. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang C, Schwieters CD, Clore GM. Open-to-closed transition in apo maltose-binding protein observed by paramagnetic NMR. Nature. 2007;449:1078–U1012. doi: 10.1038/nature06232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quiocho FA. Atomic structures of periplasmic binding-proteins and the high-affinity active-transport systems in bacteria. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1990;326:341–352. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1990.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bermejo GA, Strub MP, Ho C, Tjandra N. Ligand-free open-closed transitions of periplasmic binding proteins: the case of glutamine-binding protein. Biochemistry. 2010;49:1893–1902. doi: 10.1021/bi902045p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu BCH, Vogel HJ. A structural and functional analysis of type III periplasmic and substrate binding proteins: Their role in bacterial siderophore and heme transport. Biol Chem. 2011;392:39–52. doi: 10.1515/BC.2011.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer M, Zhang QY, Hubbard RE, Thomas GH. Caught in a TRAP: Substrate-binding proteins in secondary transport. Trends Microbiol. 2010;18:471–478. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollenstein K, Frei DC, Locher KP. Structure of an ABC transporter in complex with its binding protein. Nature. 2007;446:213–216. doi: 10.1038/nature05626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hvorup RN, et al. Asymmetry in the structure of the ABC transporter-binding protein complex BtuCD-BtuF. Science. 2007;317:1387–1390. doi: 10.1126/science.1145950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oldham ML, Khare D, Quiocho FA, Davidson AL, Chen J. Crystal structure of a catalytic intermediate of the maltose transporter. Nature. 2007;450:515–521. doi: 10.1038/nature06264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Locher KP. Structure and mechanism of ATP-binding cassette transporters. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009;364:239–245. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moussatova A, Kandt C, O’Mara ML, Tieleman DP. ATP-binding cassette transporters in Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:1757–1771. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rees DC, Johnson E, Lewinson O. ABC transporters: The power to change. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:218–227. doi: 10.1038/nrm2646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davidson AL, Dassa E, Orelle C, Chen J. Structure, function, and evolution of bacterial ATP-binding cassette systems. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2008;72:317–364. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00031-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cui J, Qasim S, Davidson AL. Uncoupling substrate transport from ATP hydrolysis in the Escherichia coli maltose transporter. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:39986–39993. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.147819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duan X, Hall JA, Nikaido H, Quiocho FA. Crystal structures of the maltodextrin/maltose-binding protein complexed with reduced oligosaccharides: Flexibility of tertiary structure and ligand binding. J Mol Biol. 2001;306:1115–1126. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharff AJ, Rodseth LE, Quiocho FA. Refined 1.8-A structure reveals the mode of binding of beta-cyclodextrin to the maltodextrin binding protein. Biochemistry. 1993;32:10553–10559. doi: 10.1021/bi00091a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsumoto N, et al. Crystal structures of open and closed forms of cyclo/maltodextrin-binding protein. FEBS J. 2009;276:3008–3019. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tetsch L, Kunte HJ. The substrate-binding protein TeaA of the osmoregulated ectoine transporter TeaABC from Halomonas elongata: Purification and characterization of recombinant TeaA. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;211:213–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grammann K, Volke A, Kunte HJ. New type of osmoregulated solute transporter identified in halophilic members of the bacteria domain: TRAP transporter TeaABC mediates uptake of ectoine and hydroxyectoine in Halomonas elongata DSM 2581(T) J Bacteriol. 2002;184:3078–3085. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.11.3078-3085.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kunte HJ. Osmoregulation in bacteria: Compatible solute accumulation and osmosensing. Environ Chem. 2006;3:94–99. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mulligan C, Fischer M, Thomas GH. Tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic (TRAP) transporters in bacteria and archaea. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2011;35:68–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forward JA, Behrendt MC, Wyborn NR, Cross R, Kelly DJ. TRAP transporters: A new family of periplasmic solute transport systems encoded by the dctPQM genes of Rhodobacter capsulatus and by homologs in diverse gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5482–5493. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5482-5493.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuhlmann SI, Terwisscha van Scheltinga AC, Bienert R, Kunte HJ, Ziegler C. 1.55 Å structure of the ectoine binding protein TeaA of the osmoregulated TRAP-transporter TeaABC from Halomonas elongata. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9475–9485. doi: 10.1021/bi8006719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berntsson RPA, Smits SHJ, Schmitt L, Slotboom DJ, Poolman B. A structural classification of substrate-binding proteins. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2606–2617. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piana S, Laio A. A bias-exchange approach to protein folding. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:4553–4559. doi: 10.1021/jp067873l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marinelli F, Pietrucci F, Laio A, Piana S. A kinetic model of Trp-cage folding from multiple biased molecular dynamics simulations. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ensing B, De Vivo M, Liu ZW, Moore P, Klein ML. Metadynamics as a tool for exploring free energy landscapes of chemical reactions. Acc Chem Res. 2006;39:73–81. doi: 10.1021/ar040198i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang J, Spek EJ, Gong Y, Zhou H, Kallenbach NR. The role of context on alpha-helix stabilization: Host-guest analysis in a mixed background peptide model. Protein Sci. 1997;6:1264–1272. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rohl CA, Fiori W, Baldwin RL. Alanine is helix-stabilizing in both template-nucleated and standard peptide helices. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3682–3687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marvin JS, Hellinga HW. Manipulation of ligand binding affinity by exploitation of conformational coupling. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:795–798. doi: 10.1038/nsb0901-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Telmer PG, Shilton BH. Insights into the conformational equilibria of maltose-binding protein by analysis of high affinity mutants. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34555–34567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Millet O, Hudson RP, Kay LE. The energetic cost of domain reorientation in maltose-binding protein as studied by NMR and fluorescence spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:12700–12705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2134311100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rizk SS, et al. Allosteric control of ligand-binding affinity using engineered conformation-specific effector proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:437–442. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muller A, et al. Conservation of structure and mechanism in primary and secondary transporters exemplified by SiaP, a sialic acid binding virulence factor from Haemophilus influenzae. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22212–22222. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603463200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lecher J, et al. The crystal structure of UehA in complex with ectoine-A comparison with other TRAP-T binding proteins. J Mol Biol. 2009;389:58–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bucher D, Grant BJ, Markwick PR, McCammon JA. Accessing a hidden conformation of the maltose binding protein using Accelerated Molecular Dynamics. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1002034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ravindranathan KP, Gallicchio E, Levy RM. Conformational equilibria and free energy profiles for the allosteric transition of the ribose-binding protein. J Mol Biol. 2005;353:196–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kandt C, Xu ZT, Tieleman DP. Opening and closing motions in the periplasmic vitamin B-12 binding protein BtuF. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13284–13292. doi: 10.1021/bi061280j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kar G, Keskin O, Gursoy A, Nussinov R. Allostery and population shift in drug discovery. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boehr DD, Nussinov R, Wright PE. The role of dynamic conformational ensembles in biomolecular recognition. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:789–796. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walmsley AR, Shaw JG, Kelly DJ. The mechanism of ligand binding to the periplasmic C4-dicarboxylate binding protein (DctP) from Rhodobacter capsulatus. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:8064–8072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas GH, Southworth T, Leon-Kempis MR, Leech A, Kelly DJ. Novel ligands for the extracellular solute receptors of two bacterial TRAP transporters. Microbiology. 2006;152:187–198. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28334-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kabsch W. Automatic processing of rotation diffraction data from crystals of initially unknown symmetry and cell constants. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:795–800. [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCoy AJ. Solving structures of protein complexes by molecular replacement with Phaser. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2007;63:32–41. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906045975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bahar M, et al. SPINE workshop on automated X-ray analysis: A progress report. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:1170–1183. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906032197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: Building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Painter J, Merritt EA. Optimal description of a protein structure in terms of multiple groups undergoing TLS motion. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:439–450. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906005270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hess B, Kutzner C, van der Spoel D, Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: Algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J Chem Theor Comput. 2008;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bonomi M, et al. PLUMED: A portable plugin for free-energy calculations with molecular dynamics. Comput Phys Commun. 2009;180:1961–1972. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Phillips JC, et al. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J Comp Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mackerell AD, Feig M, Brooks CL. Extending the treatment of backbone energetics in protein force fields: Limitations of gas-phase quantum mechanics in reproducing protein conformational distributions in molecular dynamics simulations. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1400–1415. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Diederichs K, Karplus PA. Improved R-factors for diffraction data analysis in macromolecular crystallography. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:269–275. doi: 10.1038/nsb0497-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]