Abstract

Although the palladium-catalyzed Tsuji-Trost allylic substitution reaction has been intensively studied, there is a lack of general methods to employ simple benzylic nucleophiles. Such a method would facilitate access to “α-2-propenyl benzyl” motifs, which are common structural motifs in bioactive compounds and natural products. We report herein the palladium-catalyzed allylation reaction of toluene-derived pronucleophiles activated by tricarbonylchromium. A variety of cyclic and acyclic allylic electrophiles can be employed with in situ generated (η6-C6H5–CHLiR)Cr(CO)3 nucleophiles. Catalyst identification was performed by high throughput experimentation (HTE) and led to the Xantphos/palladium hit, which proved to be a general catalyst for this class of reactions. In addition to η6-toluene complexes, benzyl amine and ether derivatives (η6-C6H5–CH2Z)Cr(CO)3 (Z=NR2, OR) are also viable pronucleophiles, allowing C–C bond-formation alpha to heteroatoms with excellent yields. Finally, a tandem allylic substitution/demetallation procedure is described that affords the corresponding metal-free allylic substitution products. This method will be a valuable complement to the existing arsenal of nucleophiles with applications in allylic substitution reactions.

1. INTRODUCTION

The formation of carbon-carbon bonds represents one of the most fundamental and well-studied processes in organic synthesis. Nonetheless, the efficient catalytic generation of C–C bonds between sp3 hybridized carbons remains challenging.1 Although palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions have received significant recent attention, an alternative approach to such C–C bond-formations is the palladium-catalyzed Tsuji-Trost allylic substitution reaction. This reaction has been intensively studied, because it provides a variety of efficient and atom-economical methods for synthesis of natural products and bioactive targets.2

Although a broad array of stabilized or “soft” nucleophiles (those derived from conjugate acids with pKa’s < 25) has been explored, palladium-catalyzed allylic alkylations with “hard” nucleophiles (derived from conjugate acids with pKa’s > 25) have received considerably less attention. “Hard” nucleophiles used in palladium-catalyzed allylic alkylations are largely organometallic compounds such as alkyllithium and Grignard reagents.3 Their high reactivity and limited functional group tolerance, however, render the use of these hard nucleophiles in allylic substitution less attractive. One strategy to develop allylic substitution reactions with nucleophiles that are traditionally considered hard is to “soften” them by addition of an activating agent to acidify the conjugate acid. Recent advances based on this strategy were reported by Trost and coworkers with nucleophiles derived from 2-methylpyridines (Scheme 1A).4 The sp3 hybridized C–H’s of 2-methylpyridine have a pKa of 34,5 and therefore its conjugate base is classified as hard. To moderate the reactivity of the conjugate base, the pyridine nitrogen was coordinated to BF3. The resulting BF3-bound complex was deprotonated and employed in palladium-catalyzed asymmetric allylic substitution with excellent enantio- and diastereoselectivity. Interestingly, no such activation was necessary with more activated benzylic C–H’s, such as those of methylated pyrazine (Scheme 1B), pyrimidine, pyridazine, quinoxaline, and benzoimidazole pronucleophiles.4c

Scheme 1.

Palladium-catalyzed Benzylic Allylations.

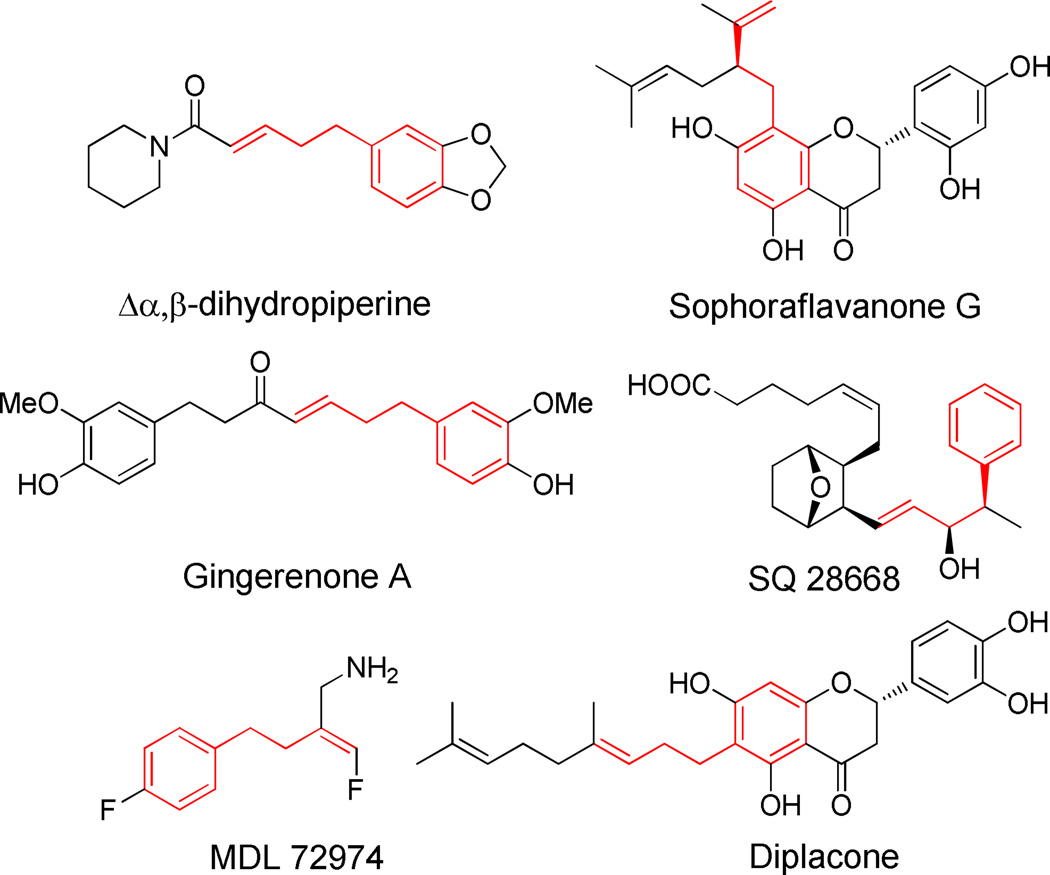

Despite the elegance and medicinal relevance of Trost’s synthesis of enantioenriched pyridine derivatives, an approach to activation of weakly acidic benzylic C–H’s for use in allylic substitution reactions is needed. Toluene, for example, with a pKa of 44±1,6 is very weakly acidic and the conjugate base of toluene has not been used in palladium catalyzed allylic substitution reactions (Scheme 1C).7–9 Yet hundreds of bioactive compounds and natural products contain the “α-2-propenyl benzyl” motif (Figure 1), with applications ranging from medicinal agents for hyperkalemia,10 Alzheimer's,11 and urinary tract diseases,12 to cosmetics,13 antibiotics14 and phytoncides15.

Figure 1.

Selected bioactive compounds and natural products containing the “α-2-propenyl benzyl” motif.

To broaden the scope of useful nucleophiles for the palladium-catalyzed Tsuji-Trost reaction, we set out to develop the application of toluene derivatives as precursors to benzylic nucleophiles. To achieve this goal, conditions to deprotonate toluene derivatives that are compatible with the catalyst, reagents, and products in the allylic substitution reaction would be necessary. It is known that η6-coordination of arenes to metals activates the benzylic C–H’s toward deprotonation.16,17 We hypothesized that η6-arene complexes could be reversibly deprotonated18 under palladium catalyzed allylic substitution reaction conditions and would serve as surrogates for hard benzylic organometallic reagents. Herein we report the successful application of (η6-C6H5–CH2R)Cr(CO)3 complexes as nucleophile precursors in allylic substitution reactions (Scheme 1C). This method enables the synthesis of a variety of valuable aryl-containing compounds that would be otherwise difficult to access.

2. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

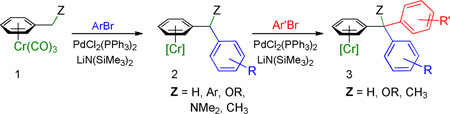

We recently disclosed the palladium-triphenylphosphine-catalyzed cross-coupling of aryl bromides and (η6-C6H5–CH2R)Cr(CO)3 complexes in the presence of LiN(SiMe3)2 to afford a broad range of di- and triarylmethanes (eq 1).18 The Cr(CO)3 fragment is easily installed simply by refluxing the arene with Cr(CO)6. After the coupling reaction, decomplexation of the chromium moiety is performed by exposure of the solution of the chromium arene complex to room light and air. On the basis of this study, we hypothesized that (η6-C6H5–CH2R)Cr(CO)3 complexes might be suitable substrates in palladium catalyzed allylic substitution reactions.

|

(1) |

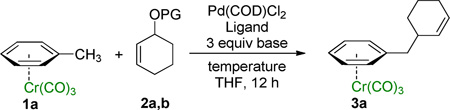

2.1. Development and Optimization of Palladium-catalyzed Allylic Substitution with (η6-C6H5–CH3)Cr(CO)3

Given that the cross-coupling of (η6-C6H5–CH3)Cr(CO)3 with aryl bromides was successfully catalyzed by palladium-triphenylphosphine complexes, which also catalyze allylic substitutions,19 we initially examined the allylic substitution reaction with the same catalyst and base. Combination of the toluene complex (η6-C6H5–CH3)Cr(CO)3 (1a) with tert-butyl cyclohex-2-enyl carbonate (2a) as the electrophilic partner, LiN(SiMe3)2 to reversibly deprotonate the toluene complex and THF solvent was performed. Heating the reaction mixture to 60 °C in THF resulted in only trace amounts of product after 12 h (Table 1, entry 1). We then turned to microscale high-throughput experimentation (HTE) techniques20 to identify an initial catalyst lead. Using 12 diverse phosphine ligands, 4 palladium precursors and 4 bases (see Supporting Information for details) revealed that the combination of 10 mol % Cl2Pd(COD) and Xantphos with 3 equiv LiN(SiMe3)2 in THF at 60 °C was the most promising combination of those examined for conversion of 1a to the corresponding allylation product 3a. Translation of this lead to laboratory scale under the same conditions afforded 3a in 39% yield (Table 1, entry 2). Decreasing the reaction temperature from 60 °C to ambient temperature and further to 0 °C indicated that conducting the reaction above or below ambient temperature proved deleterious to the yield (Table 1, entries 2–4). Combination of 1 equiv of the stronger bases LDA or n-BuLi with 3 equiv of LiN(SiMe3)2 to favor deprotonation of 1a resulted in poor yields (Table 1, entries 5–6).

Table 1.

Optimization of Allylic Substitution with 1a.a

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | PG | mol % | Ligand | Base | Temp (°C) | Yieldb (%) |

| 1 | Boc (2a) | 10 | PPh3 | LiN(SiMe3)2 | 60 | Trace |

| 2 | Boc | 10 | Xantphos | LiN(SiMe3)2 | 60 | 39 |

| 3 | Boc | 10 | Xantphos | LiN(SiMe3)2 | rt | 72 |

| 4 | Boc | 10 | Xantphos | LiN(SiMe3)2 | 0 | 39 |

| 5 | Boc | 10 | Xantphos | LiN(SiMe3)2/LDAd | rt | 29 |

| 6 | Boc | 10 | Xantphos | LiN(SiMe3)2/nBuLid | rt | <10 |

| 7 | Boc | 10 | Xantphos | LiN(SiMe3)2/NEt3e | rt | >95 |

| 8 | Boc | 5 | Xantphos | LiN(SiMe3)2/NEt3e | rt | 88c |

| 9 | Piv (2b) | 5 | Xantphos | LiN(SiMe3)2/NEt3e | rt | 96c |

Reactions conducted on a 0.1 mmol scale using 1 equiv of 1a and 2 equiv of 2 at 0.1 M.

Yield determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy of the crude reaction mixture.

Isolated yield after chromatographic purification.

Mixed bases of 3 equiv of LiN(SiMe3)2 and 1 equiv of LDA (or nBuLi).

Amine additive (1 equiv) treated with 3 equiv of LiN(SiMe3)2.

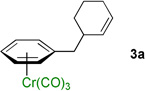

A key variable in optimizing organolithium reactions is the degree of aggregation.21 To reduce the degree of aggregation, a single equiv of NEt3 was added in combination with 3 equiv of LiN(SiMe3)2. With this mixture, 3a was formed in >95% yield (Table 1, entry 7). Under these conditions, catalyst loading could be reduced to 5 mol % (Table 1, entry 8). Switching the allylic partner from the carbonate 2a to the pivalate 2b also resulted in excellent isolated yield (96%, Table 1, entry 9). The structure of 3a was determined by X-ray diffraction (see Supporting Information) and is consistent with allylic substitution outlined in Table 1. Using these optimized conditions, we then examined various (η6-C6H5–CH2R)Cr(CO)3 complexes as nucleophile precursors.

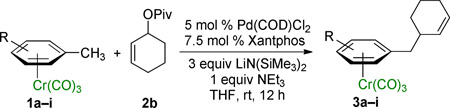

2.2. Scope of Nucleophiles in Palladium-catalyzed Allylic Substitution Reactions

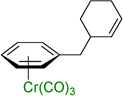

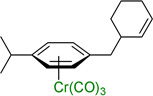

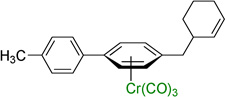

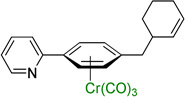

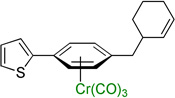

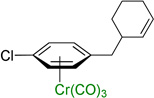

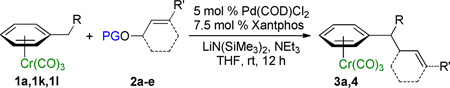

Employing the optimized conditions with the pivalate ester 2b (Table 1, entry 9) the scope of the (η6-Ar–CH2R)Cr(CO)3 pronucleophiles in the allylic substitution reaction was evaluated (Table 2). In addition to the toluene complex (entry 1) use of (η6-Ar–CH2R)Cr(CO)3 complexes bearing various substituents on the η6–arene were well tolerated. Although the p-isopropyl substituted arene was a good substrate (entry 2, 89% yield) p-methylanisole gave only trace product. In contrast, the meta isomer underwent allylation in 80% yield (entry 3). The difference between these isomeric substrates is likely due to the decreased acidity of the benzylic C–H bonds para to the methoxy. Aryl substituents on the η6-arene were good substrates. To highlight the increase in reactivity of (η6-tolyl)Cr(CO)3 compared with an unactivated tolyl group, the 4,4’-dimethylbiphenyl complex was employed. This substrate underwent allylation exclusively at the chromium-activated position (entry 4, 90% yield). Although the Cr(CO)3 moiety is known to “walk” between neighboring arenes at high temperature,22 only the monoallylation product was observed under our conditions, indicating that walking did not occur. Heteroaryl substrates containing 2-pyridyl, 2-thiophenyl, and N-pyrrolyl groups attached to the η6-tolyl group proved to be good substrates (entries 5–7, 74–80% yield). Heteroaromatic compounds are well-known for their utility in medicinal chemistry.

Table 2.

Scope of Nucleophiles in Allylic Substitution Reactions.a

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Product | Compound | Yield (%) |

| 1 |  |

3a | 96b |

| 2 |  |

3b | 89b |

| 3 |  |

3c | 80b |

| 4 |  |

3d | 90b |

| 5 |  |

3e | 77b |

| 6 |  |

3f | 80b |

| 7 |  |

3g | 74b |

| 8 |  |

3h | 45b,c |

| 9 |  |

3i | 71b |

Reactions conducted on a 0.1 mmol scale using 1 equiv of 1 and 2 equiv of 2b at 0.1 M.

Isolated yield after chromatographic purification.

Reaction time was 1.5 h.

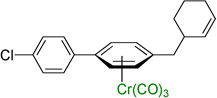

Notably, (η6-p-chlorotoluene)Cr(CO)3 complex participated in the allylic substitution to furnish the product in 45% yield (entry 8). Surprisingly, no products derived from Ar–Cl oxidative addition of (η6-p-chlorotoluene)Cr(CO)3 by palladium were observed, although η6-coordination is known to facilitate oxidative addition of chloroarene complexes.23 The chloro-substituted biphenyl derivative underwent allylic substitution to give the chloro-containing product in 71% yield (entry 9).

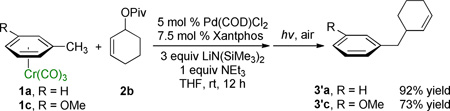

The (η6-arene)Cr(CO)3 allylic substitution product in Table 2 could be used in a variety of subsequent transformations facilitated by the chromium.17 However, the chromium-free complexes are often the desired products. Arene complexes of the type (η6-arene)Cr(CO)3 can be decomplexed simply by exposure to light and air to afford the corresponding arenes. To demonstrate the synthetic utility of this chemistry, a tandem allylic substitution/demetallation procedure was examined. With the (η6-toluene)Cr(CO)3 and 3-methoxy analogue the allylic substitution was performed to generate the new arene complex, as outlined in eq 2. The reaction mixture was then exposed to light and air by removing the septum and placing the reaction vessel on a stir plate on the windowsill (eq 2). After stirring for 3 – 6 h under light and air, the demetal-lated products were isolated in 92% (3’a) and 73% (3’c) yield.

|

(2) |

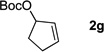

2.3. Scope of Electrophiles in Palladium-catalyzed Allylation Reactions with Arene Nucleophiles

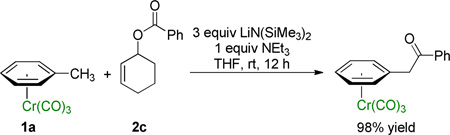

We next studied the impact of the leaving group on the allylic substitution. Varying the leaving group on 2-cyclohexen-1-ol from Boc (2a) to pivalate (2b) and benzoate esters (2c) resulted in 87–96% isolated yields of the allylation product 3a (Table 3, entries 1–3). Although the pivalate ester resulted in the highest yield, these results indicate that the reaction with this substrate class is tolerant of the nature of the leaving group. The reaction of 1a with 2c in the absence of Cl2Pd(COD)/Xantphos was performed as a control experiment. Instead of formation of the allylic substitution product 3a, PhCOCH2–(η6-C6H5)Cr(CO)3 was isolated in 98% yield as the exclusive product, which was formed from nucleophilic addition to the carbonyl group of 2c (eq 3). This result indicates that palladium-Xantphos-based catalyst changes the chemoselectivity of the reaction from carbonyl addition to allylic substitution.

Table 3.

Scope of Electrophiles in Allylic Substitution Reactions.a

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Electrophile | R | Product | Yield |

| 1 | PG = Boc (2a) | H |  |

88%b |

| 2 | PG = Piv (2b) | H | 96%b | |

| 3 | PG = Bz (2c) | H | 87%b | |

| 4 | H |  |

81%b,c | |

| 5 | Me |  |

86%b,c | |

| 6 | Ph |  |

91%b,c | |

| 7 | Me |  |

L:B = 77:23c,d L:71% yield b,e |

|

| 8 | Me | L:B = 85:15c,d L:75% yieldb,e |

||

Reactions conducted on a 0.1 mmol scale using 1 equiv of 1, an excess of LiN(SiMe3)2 and 2 at 0.1 M. (see Supporting Information for details).

Isolated yield after chromatographic purification.

PMDTA was added as an amine additive in place of NEt3.

Ratio of linear : branched (L:B) was determined by 1H NMR of the crude reaction mixture.

The regioisomers were separable by silica gel chromatography.

|

(3) |

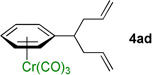

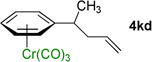

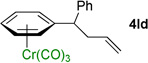

We next examined acyclic electrophiles as partners in the allylic substitution. The Boc derivative of allyl alcohol, 2d, reacted with various (η6-arene)Cr(CO)3 complexes to yield substitution products (Table 3, entries 4–6). Reaction of the (η6-toluene)Cr(CO)3 complex with BocOCH2CH=CH2 (2d) resulted in formation of the diallylation product 4ad (81% yield) when 1 equiv of 1a was treated with 6 equiv of LiN(SiMe3)2, 4 equiv of the allylic substrate (2d), and 2 equiv of N,N,N',N'',N''-pentamethyldiethylenetriamine (PMDTA) as additive in place of NEt3. When (η6-arene)Cr(CO)3 complexes derived from ethylbenzene (1k) and diphenylmethane (1l) were reacted with 2d, the monoallylation products were obtained in 86% (4kd) and 91% (4ld) yields (entries 5 and 6, respectively).

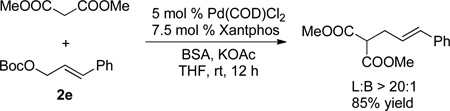

With unsymmetrical linear electrophiles derived from Boc-protected cinnamyl alcohol (2e) full consumption of (η6-PhEt)Cr(CO)3 (1k) was observed. It is well known that π-allylpalladium complexes formed from cinnamyl alcohol derivatives tend to react with carbon-based nucleophiles at the unsubstituted terminus of the π-allyl group for both steric and electronic reasons.16b Surprisingly, however, the allylation product was obtained as a mixture of regioisomers at ambient temperature with a linear : branched ratio (L:B) of 77:23 (as determined by 1H NMR of the crude reaction mixture, entry 7). Regioselectivity in palladium-catalyzed allylic substitution reactions can be influenced by the nature of the ligands,24 solvent, and counterion.25 For the purpose of comparison, we employed the stabilized nucleophile derived from dimethyl malonate under the same reaction conditions with the Xantphos-based palladium catalyst (eq 4). In this case, the linear product was obtained with excellent regioselectivity (linear : branched > 20:1, 85% yield).26 We hypothesize that the reduced regioselectivity with the nucleophile generated from (η6-ethylbenzene)Cr(CO)3 is a result of the high reactivity of the Cr(CO)3-stabilized organolithium, which led to lower selectivity. We therefore conducted the reaction at 0 °C and observed an increase in the linear : branched ratio to 85:15 (Table 3, entry 8). The linear product was separated from the branched by column chromatography and isolated in 75% yield.

|

(4) |

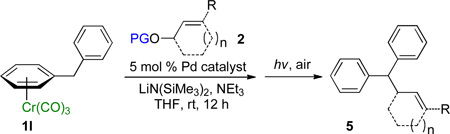

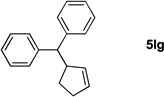

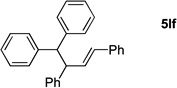

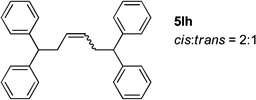

2.4. Tandem Allylation/Demetallation with Diphenylmethane Derivatives

Diarylmethane derivatives are attracting considerable attention due to their growing importance in developing pharmaceuticals,27 dye precursors,28 and applications in materials science29. Given the utility of these compounds, we investigated palladium-catalyzed allylic substitutions with (η6-C6H5CH2Ph)Cr(CO)3 (1l) with a variety of cyclic and acyclic allylic partners. The reaction mixtures were then exposed to light and air to afford metal-free diphenylmethane derivatives in a one-pot tandem fashion (Table 4).

Table 4.

Tandem Synthesis of Diphenylmethane Derivatives.a

Reactions conducted on a 0.1 mmol scale using 1 equiv of 1l, an excess of LiN(SiMe3)2 and 2 at 0.1 M. (see Supporting Information for details).

Isolated yield after chromatographic purification.

Ratio of linear / branched (L:B) was determined by 1H NMR of the crude reaction mixture. The regioisomers were separable by silica gel chromatography.

[Pd(allyl)Cl]2/1,3-bis(diphenylphosphino)propane (DPPP) was used as catalyst in place of Pd(COD)Cl2/Xantphos.

We initiated our study employing the cyclohex-2-enyl pivalate 2b. The allylic substitution was performed in THF with 1 equiv of (η6-C6H5CH2Ph)Cr(CO)3 (1l), 2 equiv of pivalate 2b and 3 equiv of LiN(SiMe3)2 (entry 1). When the allylic substitution was complete, as judged by TLC, the flask was opened to air and placed on a stir plate on the windowsill to expose the reaction mixture to sunlight. A green precipitate formed during the demetallation as the chromium was oxidized. The reaction mixture was then filtered through a pad of MgSO4 and silica, concentrated in vacuo and loaded directly onto a silica gel column. The metal free product 5lb was isolated as clear oil in 96% yield after column chromatography. The reaction of tert-butyl cyclopent-2-enyl carbonate (2g) was performed under similar conditions and provided the substitution product in 89% yield (5lg, entry 2).

Acyclic allylic alcohol derivatives were also good substrates in the allylic substitution/demetallation tandem reaction. Use of the Boc derivative of the parent allyl alcohol (2d) resulted in isolation of the substitution product in 91% yield (5ld, entry 3). Note that the reaction of diphenylmethane [Cr(CO)3-free] with allylic partners did not give substitution products, underscoring the necessity of the activating Cr(CO)3 agent. trans-1,3-Diphenylallyl acetate (2f) underwent the allylic substitution/demetallation to give 5lf in 96% isolated yield (entry 4). Reaction of 1l with a bifunctional substrate, cis-1,4-diacetoxy-2-butene (2h), gave 77% isolated yield (88% per C–C bond formation) of the diallylation product 5lh as an E/Z ratio of 1:2 (entry 5).30

Evaluation of π-geranylpalladium complex was motivated by the recent isolation of several α-geranylated toluene derivatives.31 Furthermore, α-geranylated toluene derivatives have shown interesting bioactive properties32 and are key intermediates in total synthesis of antibiotics33. Addition of the organolithium derived from (η6-C6H5CH2Ph)Cr(CO)3 (1l) to tert-butyl geranyl carbonate complex 2i exhibited good regioselectivity (L:B = 78:22) and good isolated yield of the linear product 5li (73% yield, entry 6). The carbon-carbon double bond of the products in Table 4 will facilitate subsequent functionalizations to afford a variety of diphenylmethane derivatives.

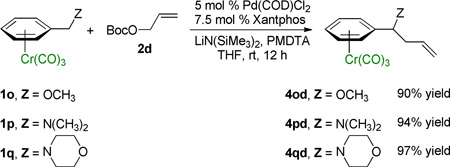

2.5. Allylation with Benzyl Amine and Ether Derivatives

Stereogenic centers alpha to heteroatoms are important in the synthesis of bioactive compounds. We therefore examined reactions of benzyl ether and amine substrates (η6-C6H5–CH2Z)Cr(CO)3 (Z=OR, NR2). Benzylamines often direct metallation to the ortho position34 as do activated (η6-C6H5–CH2Z)Cr(CO)3 complexes in the presence of strong organolithium bases (Z=NR2). Interestingly, under the reversible deprotonation conditions employed herein, (η6-C6H5–CH2Z)Cr(CO)3 complexes exhibit orthogonal chemoselectivity with metallation taking place at the benzylic C–H’s. As illustrated in eq 5, the (η6-C6H5–CH2Z)Cr(CO)3 benzyl ether (1o) and amines (1p, 1q) are excellent substrates for the allylic substitution reaction with allyl tert-butyl carbonate 2d, giving products in high yields (90–97%).

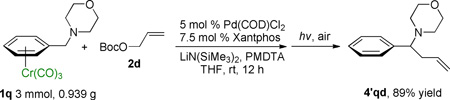

The scalability of this method was demonstrated by a tandem allylic substitution/demetallation reaction of benzyl morpholine (1q) on a 3 mmol scale, which afforded the metal-free organic product in 89% yield (eq 6).

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

2.6. Allylation at Multiple Benzylic Sites

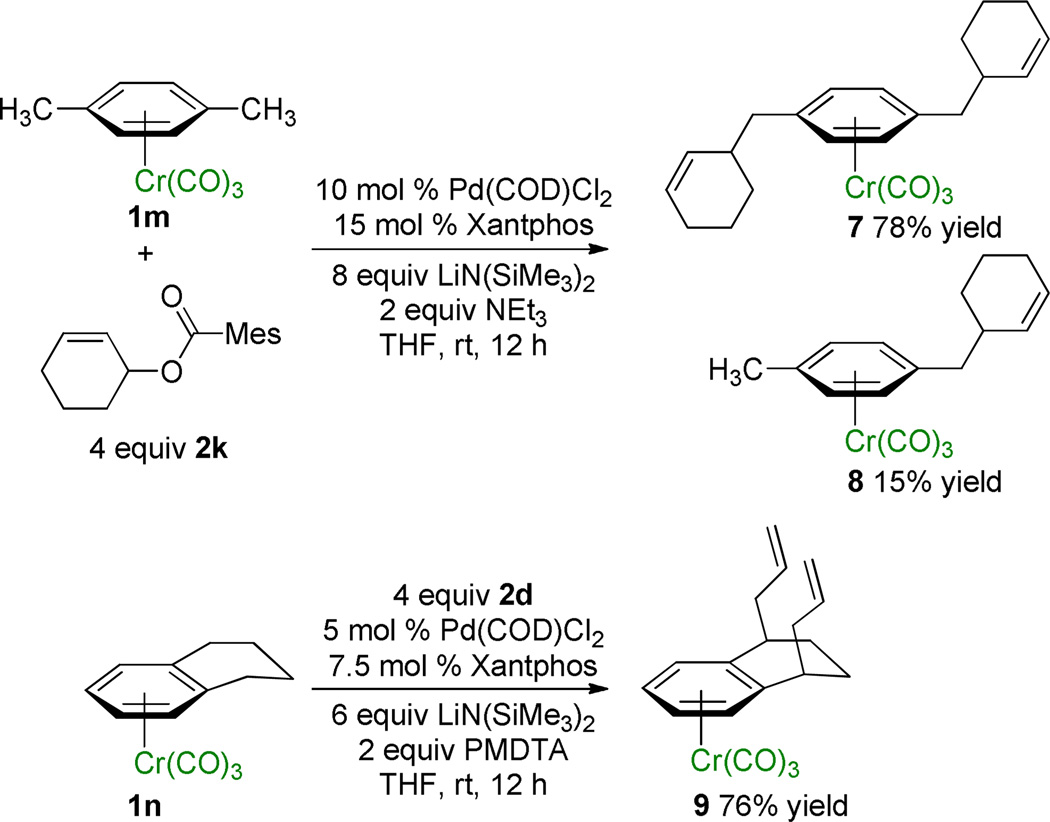

Having demonstrated that diallylation could occur on a single benzylic methyl group (Table 3, entry 4), we explored the possibility of activation of multiple benzylic positions in (η6-arene)Cr(CO)3 complexes of p-xylene and tetralin (Scheme 2). Subjecting (η6-p-xylene)Cr(CO)3 (1m) to allylation conditions with a sterically hindered allylic partner, cyclohex-2-enyl mesitoate (2k), furnished the diallylation product 7 in 78% isolated yield.

Scheme 2.

Allylation at Multiple Benzylic Sites.

In the case of (η6-tetralin)Cr(CO)3 (1n) we were somewhat concerned that after the first allylation, the newly formed 2-propenyl moiety would hinder deprotonation of the second benzylic center by the bulky base, LiN(SiMe3)2. As shown in Scheme 2, however, the double allylation proceeded smoothly at ambient temperature and the cis-diallylation product 9 was isolated in 76% yield.17,18 Presumably this approach could be coupled with ring closing metathesis to afford bicyclic scaffolds.

2.7. Internal vs. External Attack of (η6-Ar–CH2Li)Cr(CO)3 on π-Allyl Palladium Intermediate

One significant difference between “hard” and “soft” nucleophiles in allylic substitution reactions is their distinct mechanistic pathways. Nucleophiles classified as “soft” undergo external attack on the π-allyl ligand35 and the net process of the allylic substitution is stereoretentive (via double inversion). In contrast, “hard” nucleophiles undergo addition to the metal center of the π-allyl complex (i.e., transmetallation) followed by reductive elimination to form the new C–C bond.36 This latter mechanism results in an overall inversion of configuration in the allylic substitution.

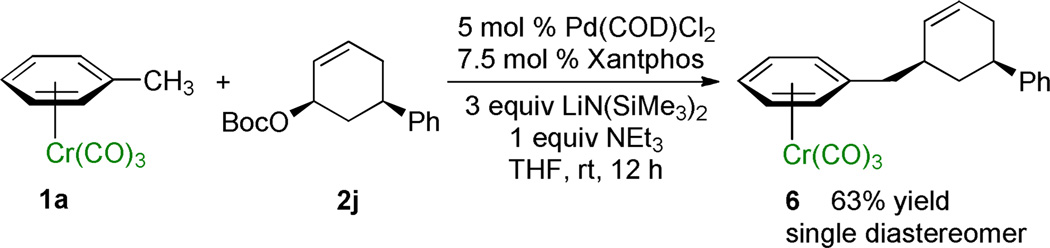

To determine whether the conjugate bases of the (η6-arene)Cr(CO)3 complexes behave as “soft” or “hard” nucleophiles in the palladium catalyzed allylic substitution, (η6-toluene)Cr(CO)3 complex 1a was reacted with the cis-disubstituted stereochemical probe 2j (Scheme 3). In the allylic substitution with 2j the product cis-6 was obtained in 63% isolated yield as a single diastereomer, as determined by comparison of the splitting patterns and coupling constants with related products by 1H NMR spectroscopy (see Supporting Information for details). Formation of cis-6 indicates that the reaction occurs predominantly via external attack of the “soft” conjugate base derived from (η6-toluene)Cr(CO)3 on the palladium-bound π-allyl ligand. The observed double inversion is consistent with the ability of the Cr(CO)3 moiety to stabilize benzyl anions by delocalization of the negative charge onto the chromium to “soften” the nucleophilicity of the organolithium.16,17

Scheme 3.

Allylic Substitution with Retention of Configuration.

3. SUMMARY AND OUTLOOK

We have developed the first general method for palladium-catalyzed allylic substitution with the conjugate bases of toluene derivatives. Key to the success of our method is the activation of the arene’s benzylic C–H’s by η6-coordination to tricarbonylchromium. Also very important was the HTE approach to identify the Xantphos/Pd(COD)2Cl2 combination as an excellent catalyst for this allylic substitution reaction. Mechanistic studies indicate that (η6-toluene)Cr(CO)3 derivatives behave as “soft” or stabilized nucleophiles. They attack the palladium π-allyl complex externally, leading to a net double inversion in the allylic substitution. The (η6-arene)Cr(CO)3 derivatives are reversibly deprotonated by LiN(SiMe3)2 under mild conditions allowing for the in situ generation of the nucleophilic organolithium intermediates.

The synthetic significance of this method is that it enables the application of a variety of benzylic nucleophiles in palladium catalyzed allylic substitution reactions and provides access to allylation products that are otherwise difficult to prepare. The method is general in that a range of nucleophiles, derived from (η6-arene)Cr(CO)3 complexes, can be readily employed with structurally diverse allylic alcohol derivatives bearing OAc, OBz, OBoc, or OPiv leaving groups. A tandem allylic substitution/demetallation procedure has been developed for the one-pot synthesis of diarylmethane derivatives, which are increasing in their importance. We believe this method will be a valuable complement to the existing arsenal of nucleophiles with applications in allylic substitution reactions. Identification of catalysts for asymmetric palladium-catalyzed allylic substitution reactions is underway.37

4. EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Representative procedures are described herein. Full experimental details and characterization of all compounds are provided in the Supporting Information.

General Methods

All reactions were performed under nitrogen using oven-dried glassware and standard Schlenk or vacuum line techniques. Air- and moisture sensitive solutions were handled under nitrogen and transferred via syringe. THF was freshly distilled from Na/benzophenone ketyl under nitrogen. Unless otherwise stated, reagents were commercially available and used as purchased without further purification. Chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich or Acros, and solvents were purchased from Fisher Scientific. The progress of reactions was monitored by thin-layer chromatography using Whatman Partisil® K6F 250 µm precoated 60 Å silica gel plates and visualized by short-wave ultra-violet light as well as by treatment with ceric ammonium molybdate (CAM) stain. Silica gel (230–400 mesh, Silicycle) was used for air-flashed chromatography. The 1H NMR and 13C{1H} NMR spectra were obtained using a Brüker AM-500 Fourier-transform NMR spectrometer at 500 and 125 MHz, respectively. Chemical shifts are reported in units of parts per million (ppm) downfield from tetramethylsilane (TMS) and all coupling constants are reported in hertz. The infrared spectra were obtained ion KBr plates using a Perkin-Elmer Spectrum 100 Series FTIR spectrometer. The masses of chromium-complexes were recorded with electrospray + (ES+) HRMS methods, and [M]+ or [M-(CO)3]+ (unless otherwise stated) was confirmed by the presence of the characteristic chromium isotope pattern. Chromium-decomplexed masses were recorded with chemical ionization + (CI+) HRMS methods.

Cautionary Note

Care should be taken to avoid direct exposure of reaction mixtures to bright light, as arene tricarbonylchromium complexes can decompose in solution under bright light and air.

General Procedure A. Synthesis of (η6-toluene)Cr(CO)3 Derivatives

A solution of Cr(CO)6 (1.10 g, 5.0 mmol), arene (1.2 – 5 equiv), and THF (3 mL) in 1,4-dioxane (8 mL) was heated under reflux (oil bath temp = 120 °C) under a nitrogen atmosphere for 3 – 5 days. The yellow–orange solution was allowed to cool, and completion of the reaction was verified by the absence of solid Cr(CO)6 on the sides of the flask (from sublimation) after refluxing subsided. After cooling to rt, the solution was filtered through Celite, and then evaporated under reduced pressure. The yellow product was either recrystallized from diethyl ether and hexanes or purified by column chromatography eluting with EtOAc/hexanes.

General Procedure B. Pd-catalyzed Allylic Substitution with (η6-arene-CH2Z)Cr(CO)3-based Nucleophiles

An oven-dried reaction vial equipped with a stir bar was charged with (η6-arene-CH2Z)Cr(CO)3 (0.10 mmol). To the reaction vial was added LiN(SiMe3)2 (50.2 mg, 0.30 mmol, 3 equiv) under a nitrogen atmosphere followed by 0.5 mL of dry THF, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 5 min. A solution of Pd(COD)Cl2 (1.43 mg, 0.0050 mmol) and Xantphos (4.34 mg, 0.0075 mmol) in 0.5 mL THF was taken up by syringe and added to the reaction vial. After stirring for 5 min, the allylic electrophile (0.2 mmol, 2 equiv) was added to the reaction followed by NEt3 (14 µL, 0.1 mmol, 1 equiv). The reaction mixture was stirred for 12 h at rt. The reaction mixture was quenched with two drops of H2O, diluted with 3 mL of ethyl acetate, and filtered over a pad of MgSO4 and silica. The pad was rinsed with additional ethyl acetate and the solution was concentrated in vacuo. The crude material was loaded onto a silica gel column and purified by flash chromatography.

General Procedure C. Tandem Allylic Substitution/Demetallation

The reaction was conducted according to General Procedure B described above. After 12 h, the reaction was quenched with two drops of H2O, diluted with 10 – 20 mL of diethyl ether, and the solution was exposed to sunlight by placing it on the windowsill and stirring for 3 – 6 h. The demetallation step was monitored until TLC showed complete consumption of the (η6-arene)Cr(CO)3 product. During this time, a green precipitate formed as the chromium was oxidized. The reaction mixture was then filtered through a pad of MgSO4 and silica, concentrated in vacuo and loaded directly onto a silica gel column.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the NSF (CHE-0848467 and 0848460) for partial support of this research. We also thank the NIH for the purchase of a Waters LCTOF-Xe Premier ESI mass spectrometer (Grant No. 1S10RR23444-1) and NSF for an X-ray diffractometer (CHE–0840438).

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. Procedures, full characterization of new compounds and crystallographic data for 3a. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.(a) Cardenas DJ. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003;42:384. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Netherton MR, Fu GC. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2004;346:1525. [Google Scholar]; (c) Frisch AC, Beller M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:674. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Rudolph A, Lautens M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:2656. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Jana R, Pathak TP, Sigman MS. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1417. doi: 10.1021/cr100327p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Trost BM, Van Vranken DL. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:395. doi: 10.1021/cr9409804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Trost BM, Crawley ML. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:2921. doi: 10.1021/cr020027w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Trost BM. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:5813. doi: 10.1021/jo0491004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Trost BM, Machacek MR, Aponick A. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006;39:747. doi: 10.1021/ar040063c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Trost BM, Fandrick DR. Aldrichim. Acta. 2007;40:59. [Google Scholar]; (f) Lu Z, Ma S. Angew. Chem.. Int. Ed. 2008;47:258. doi: 10.1002/anie.200605113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Castanet Y, Petit F. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979;34:3221. [Google Scholar]; (b) Keinan E, Roth Z. J. Org. Chem. 1983;48:1769. and references therein. [Google Scholar]; (c) Shukla KH, DeShong P. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:6283. doi: 10.1021/jo8010254. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Trost BM, Thaisrivongs DA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:14092. doi: 10.1021/ja806781u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Trost BM, Thaisrivongs DA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:12056. doi: 10.1021/ja904441a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Trost BM, Thaisrivongs DA, Hartwig J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:12439. doi: 10.1021/ja205523e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dewick PM. Essentials of Organic Chemistry: For Students of Pharmacy, Medicinal Chemistry and Biological Chemistry. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bordwell FG, Bares JE, Bartmess JE, Drucker GE, Gerhold J, McCollum GJ, Van Der Puy M, Vanier NR, Matthews WS. J. Org. Chem. 1977;42:326. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Although metal-catalyzed benzylic allylation reaction of toluene has never been reported, a few toluene analogues bearing electron-withdrawing groups (cyano, carbonyl, nitro, etc.) on benzylic or para- position have been reported to undergo metal-catalyzed allylation reactions. Benzyl cyanides (nucleophile stabilized by cyano group): Tsuji J, Shimizu I, Minami I, Ohashi Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23:4809. Tsuji J, Shimizu I, Minami I, Ohashi Y, Sugiura T, Takahashi K. J. Org. Chem. 1985;50:1523. Minami I, Ohashi Y, Shimizu I, Tsuji J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:2449. Ikeda I, Gu X-P, Okuhara T, Okahara M. Synthesis. 1990:32. Nowicki A, Mortreux A, Agbossou-Niedercorn F. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:1617. Benzyl carbonyls (nucleophile stabilized by carbonyl group): Suzuki O, Hashiguchi Y, Inoue S, Sato K. Chem. Lett. 1988:291. Suzuki O, Inoue S, Sato K. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1989;62:239. Gravel D, Benoit S, Kumanovic S, Sivaramakrishnan H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:1407. Gravel D, Benoit S, Kumanovic S, Sivaramakrishnan H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:1403. Trost BM, Schroeder GM, Kristensen J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002;41:3492. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020916)41:18<3492::AID-ANIE3492>3.0.CO;2-P. Yan X-X, Liang C-G, Zhang Y, Hong W, Cao B-X, Dai L-X, Hou X-L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:6544. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502020. Lebeuf R, Hirano K, Glorius F. Org. Lett. 2008;10:4243. doi: 10.1021/ol801644f. Trost BM, Xu J, Schmidt T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:18343. doi: 10.1021/ja9053948. Zhao Y, Zhou Y, Liang L, Yang X, Du F, Li A, Zhang H. Org. Lett. 2009;11:555. doi: 10.1021/ol802608r. Para-nitrotoluenes: Waetzig SR, Tunge JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:14860. doi: 10.1021/ja077070r. Kim IS, Ngai M-Y, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:6340. doi: 10.1021/ja802001b.

- 8.Non-metal-catalyzed allylation of toluene derivatives (3 examples) with several allyl bromides via radical process (yield average: 61%): Tanko JM, Sadeghipour M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999;38:159. Struss JA, Sadeghipour M, Tanko JM. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:2119.

- 9.Non-metal-catalyzed allylation of toluene derivatives with allyl bromide via arene η6-coordination to organometallic fragment: Fe: Moulines F, Astruc D. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1989:614. Martinez V, Blais J-C, Astruc D. Org. Lett. 2002;4:651. doi: 10.1021/ol0172875. Martinez V, Blais J-C, Astruc D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003;42:4366. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351795. Cr: Hata T, Koide H, Taniguchi N, Uemura M. Org. Lett. 2000;2:1907. doi: 10.1021/ol0001057. Ru: Pigge FC, Fang S, Rath NP. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:2251.

- 10.Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Preventive and/or Remedy for Hyperkalemia Containing EP4 Agonist. EP1782829 (A1) Patent. 2007

- 11.Merrell Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Use of (E)-2-(p-Fluorophenethyl)-3-Fluoroallylamine in the Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease. EP0642338 (B1) Patent. 1997

- 12.Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Preventive and/or Remedy for Lower Urinary Tract Diseases Containing EP4 Agonist. EP1782830 (A1) Patent. 2007

- 13.(a) Unilever Home and Personal Care USA, Division of Conopco, Inc. Cosmetic Compositions Containing Sophora Alopecuroides L. Extracts. US2006/110341 (A1) Patent. 2006; (b) Gupta SK. New Ubiquitin-Proteasome Regulating Compounds and Their Application in Cosmetic and Pharmaceutical Formulations. US2006/269494 (A1) Patent. 2006

- 14.(a) Kouznetsov V, Urbina J, Palma A, Lopez S, Devia C, Enriz R, Zacchino S. Molecules. 2000;5:428. [Google Scholar]; (b) Vargas LY, Castelli MV, Kouznetsov VV, Urbina JM, Lopez SN, Sortino M, Enriz RD, Ribas JC, Zacchino S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2003;11:1531. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00605-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gomez-Barrio A, Montero-Pereira D, Nogal-Ruiz JJ, Escario JA, Muelas-Serrano S, Kouznetsov VV, Mendez LYV, Gonzalez JMU, Ochoa C. Acta Parasitol. 2006;51:73. [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Kang TH, Jeong SJ, Ko WG, Kim NY, Lee BH, Inagaki M, Miyamoto T, Higuchi R, Kim YC. J. Nat. Prod. 2000;63:680. doi: 10.1021/np990567x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chi YS, Jong HG, Son KH, Chang HW, Kang SS, Kim HP. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2001;62:1185. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00773-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sohn HY, Son KH, Kwon CS, Kwon GS, Kang SS. Phytomedicine. 2004;11:666. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.For books: Kündig EP. Topics in Organometallic Chemistry. Vol. 7. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag; 2004. Transition Metal Arene π-Complexes in Organic Synthesis and Catalysis. Hartwig JF. Organotransition Metal Chemistry: From Bonding to Catalysis. Sausalito, CA: University Science Books; 2010. For reviews: Kalinin VN. Usp. Khim. 1987;56:1190. [Russ. Chem. Rev.1987, 56, 682] Rosillo M, Dominguez G, Perez-Castells J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1589. doi: 10.1039/b606665h. For recent reports on asymmetric benzylic deprotonation of (η6-arene)Cr(CO)3: Koide H, Hata T, Uemura M. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:1929. doi: 10.1021/jo011052p. and references therein. Castaldi MP, Gibson SE, Rudd M, White AJP. Chem.–Eur. J. 2006;12:138. doi: 10.1002/chem.200501031. and references therein. For early reports on benzylic deprotonation of (η6-arene)Cr(CO)3 under mild conditions: Kalinin VN, Cherepanov IA, Moiseev SK. Metalloorg. Khim. 1991;4:177. [Organomet. Chem. USSR1991, 4, 94] Kalinin VN, Cherepanov IA, Moiseev SK. J. Organomet. Chem. 1997;536–537:437. Density functional theory calculations: Merlic CA, Walsh JC, Tantillo DJ, Houk KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:3596. Merlic CA, Miller MM, Hietbrink BN, Houk KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:4904. doi: 10.1021/ja000600y. Merlic CA, Hietbrink BN, Houk KN. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:6738. doi: 10.1021/jo010620y.

- 17.Uemura M. Organic Reactions. Vol. 67. New York: Wiley; 2006. p. 217. [Google Scholar]

- 18.When 1H NMR deprotonation studies were conducted in THF with 1 equiv each of 1l and LiN(SiMe3)2, 1l exhibited approximately 50% deprotonation. Under similar conditions 1a exhibited 10% deprotonation. See McGrew GI, Temaismithi J, Carroll PJ, Walsh PJ. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:5541. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000957.

- 19.Early reports on palladium-triphenylphosphine catalyzed allylic substitution reactions: Atkins KE, Walker WE, Manyik RM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1970:3821. Hata G, Takahashi K, Miyake A. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Comm. 1970:1392. Trost BM, Fullerton TJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:292. Recent report by our group: Hussain MM, Walsh PJ. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:1834. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905399.

- 20.(a) Dreher SD, Dormer PG, Sandrock DL, Molander GA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9257. doi: 10.1021/ja8031423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dreher SD, Lim S-E, Sandrock DL, Molander GA. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:3626. doi: 10.1021/jo900152n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sandrock DL, Jean-Gerard L, Chen C-Y, Dreher SD, Molander GA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:17108. doi: 10.1021/ja108949w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Molander GA, Argintaru OA, Aron I, Dreher SD. Org. Lett. 2010;12:5783. doi: 10.1021/ol102717x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Molander GA, Trice SLJ, Dreher SD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:17701. doi: 10.1021/ja1089759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Gossage RA, Jastrzebski JTBH, van Koten G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:1448. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jones AC, Sanders AW, Bevan MJ, Reich HJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:3492. doi: 10.1021/ja0689334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gessner VH, Daschlein C, Strohmann C. Chem.–Eur. J. 2009;15:3320. doi: 10.1002/chem.200900041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Traylor TG, Stewart KJ, Goldberg MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:4445. [Google Scholar]; (b) Traylor TG, Stewart KJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986;108:6977. [Google Scholar]; (c) Traylor TG, Goldberg MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:3968. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Early reports on Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling of (η6-chloroarene)Cr(CO)3 compounds: Villemin D, Schigeko E. J. Organomet. Chem. 1985;293:C10. Carpentier JF, Castanet Y, Brocard J, Mortreux A, Petit F. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:4705. Carpentier JF, Castanet Y, Brocard J, Mortreux A, Petit F. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:2001. Uemura M, Nishimura H, Hayashi T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:107. Uemura M, Nishimura H, Kamikawa K, Nakayama K, Hayashi Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:1909. Uemura M, Nishimura H, Hayashi T. J. Organomet. Chem. 1994;473:129. Carpentier JF, Finet E, Castanet Y, Brocard J, Mortreux A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:4995.

- 24.(a) You S-L, Zhu X-Z, Luo Y-M, Hou X-L, Dai L-X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:7471. doi: 10.1021/ja016121w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pretot R, Pfaltz A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998;37:323. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980216)37:3<323::AID-ANIE323>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Trost BM, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:4545. [Google Scholar]; (b) Butts CP, Filali E, Lloyd-Jones GC, Norrby P-O, Sale DA, Schramm Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9945. doi: 10.1021/ja8099757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bravo-Altamirano K, Montchamp J-L. Org. Lett. 2006;8:4169. doi: 10.1021/ol061828e. Usui I, Schmidt S, Breit B. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1453. doi: 10.1021/ol9001812. In these papers, only linear products were reported without mentioning branched products.

- 27.(a) Cavallini G, Massarani E, Nardi D, Mauri L, Barzaghi F, Mantegazza P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1959;81:2564. [Google Scholar]; (b) Attwood D. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1976;28:407. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1976.tb04643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tobe A, Yoshida Y, Ikoma H, Tonomura S, Kikumoto R. Arzneim. Forsch., Drug. Res. 1981;31–2:1278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ohizumi Y, Takahashi M, Tobe A. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1982;75:377. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1982.tb08797.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Hattori H, Yamamoto S, Iwata M, Takashima E, Yamada T, Suzuki O. J. Chromatogr.-Biomed. 1992;581:213. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(92)80274-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Li JJ, Johnson DS, Sliskovic DR, Roth BD. Contemporary Drug Synthesis. Wiley-Interscience; 2004. p. 221. (ZYRTEC®) [Google Scholar]

- 28.(a) Oster G, Nishijima Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1956;78:1581. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bomberger DC, Gwinn JE, Boughton RL. Wastes from Manufacture of Dyes and Pigments. Washington, DC: US EPA-600/2-84-lll, US. Government Printing Office; [Google Scholar]

- 29.Randall D, Lee S. The Polyurethanes Book. New York: Wiley; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bouquillon S, Muzart J. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2001:3301. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zima A, Hosek J, Treml J, Muselik J, Suchy P, Prazanova G, Lopes A, Zemlicka M. Molecules. 2010;15:6035. doi: 10.3390/molecules15096035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murakami S, Kijima H, Isobe Y, Muramatsu M, Aihara H, Otomo S, Baba K, Kozawa M. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1990;42:723. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1990.tb06568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.(a) Van Tamelen EE, Carlson JG, Russell RK, Zawacky SR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981;103:4615. [Google Scholar]; (b) Van Tamelen EE, Zawacky SR, Russel RK, Carlson JG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:142. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kim MB, Shaw JT. Org. Lett. 2010;12:3324. doi: 10.1021/ol100929z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ortho-palladation: Cope AC, Friedrich EC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968;90:909. Dupont J, Consorti CS, Spencer J. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2527. doi: 10.1021/cr030681r. Vicente J, Saura-Llamas I, Palin MG, Jones PG, Ramirez de Arellano MC. Organometallics. 1997;16:826. Ortho-arylation: Daugulis O, Lazareva A. Org. Lett. 2006;8:5211. doi: 10.1021/ol061919b.

- 35.Trost BM, Verhoeven TR. J. Org. Chem. 1976;41:3215. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsushita H, Negishi E. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Comm. 1982:160. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trost ligands have proved successful in a range of asymmetric allylic substitution reactions of cycloalkenyl substrates. We employed (R, R)-DACH-phenyl Trost ligand in place of Xantphos as ligand for the reaction of 1a with the benzoate ester 2c. However, no desired allylic substitution product was observed. PhCOCH2–(η6-C6H5)Cr(CO)3 was isolated in 96% yield as the exclusive product. We then switched the allylic partner from 2c to carbonate 2a, but we did not observe any desired allylic substitution product from either (R, R)-DACH-phenyl Trost ligand or (R, R)-DACH-naphthyl Trost ligand under the reaction conditions.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.