Abstract

Hebbian synaptic plasticity, such as hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP), is thought to be important for particular types of learning and memory. It involves changes in the expression and activity of a large array of proteins, including cell adhesion molecules. The integrin class of cell adhesion molecules has been extensively studied in this respect, and appear to have a defined role in consolidating both structural and functional changes brought about by LTP. With the use of integrin inhibitors, it has been possible to identify a critical time window of several minutes after LTP induction for the participation of integrins in LTP. Altering the interactions of integrins with their ligands during this time compromises structural changes involving actin polymerisation and spine enlargement that could be required for accommodating new AMPA receptors (AMPARs). After this critical window of structural remodelling and plasticity, integrins “lock-in” and stabilise the morphological changes, conferring the requisite longevity for LTP. Genetic manipulations targeting integrin subtypes have helped identify the specific integrin subunits involved in LTP and correlate alterations in plasticity with behavioural deficits. Moreover, recent studies have implicated integrins in AMPAR trafficking and glycine receptor lateral diffusion, highlighting their multifaceted functions at the synapse.

Keywords: Cell adhesion molecules, Integrin, Hebbian plasticity, LTP, Homeostatic synaptic scaling, Actin

1. Introduction

The activity-dependent modification of synaptic efficacy, termed synaptic plasticity, underpins the capacity of neuronal networks to adapt to changes in external stimuli, and to process and transmit information. Many forms of plasticity have been described, from short-term (ranging from milliseconds to several minutes) (Zucker and Regehr, 2002) to long-term (ranging from hours to years) (Citri and Malenka, 2008), all of which involve changes in synaptic efficacy in a discrete number of synapses. The two most extensively studied forms of long-term plasticity, LTP and long-term depression (LTD), which are thought to represent the cellular correlate of learning and memory, can have different mechanisms of expression depending on the neuronal circuits in which they operate (Citri and Malenka, 2008). Other forms of plasticity act on a much broader regulatory scale. For example, homeostatic synaptic plasticity serves as a negative feedback mechanism in response to global changes in neuronal network activity, resulting in a compensatory and uniform scaling of all synaptic strengths (Pozo and Goda, 2010; Turrigiano, 2008).

The mechanisms by which neurons translate transient changes in stimuli into long-term changes in synaptic efficacy are varied, and can include alterations in presynaptic release probability and postsynaptic responsiveness. Regardless, they usually always involve progressive steps engaging a discrete collection of proteins and signalling events. For example, LTP is commonly divided into two phases: an early phase lasting 1–2 h (E-LTP), which relies on posttranslational modifications and glutamate receptor trafficking, and a later phase (L-LTP), which is dependent on transcription and translation (Abraham and Williams, 2008). Induction of E-LTP requires NMDA receptor (NMDAR) activation and elevation of [Ca2+]i, followed by protein kinase activation, AMPAR phosphorylation and insertion into the postsynaptic membrane; in some cases, E-LTP may also accompany increased presynaptic glutamate release probability. L-LTP appears to entail structural changes requiring local protein synthesis, protease activation and proteolytic cleavage, actin polymerisation and growth of spines, in conjunction with synthesis and insertion of adhesion molecules to stabilise synaptic contacts (Citri and Malenka, 2008; Abraham and Williams, 2008).

Many cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) have a well established role in the development and maintenance of synaptic structures. Moreover, it is now well appreciated that they also have an important role in the activity-dependent functional changes in synaptic efficacy in the mature brain. CAMs that have been demonstrated to play key roles in synaptic plasticity include neurexins and neuroligins (Dahlhaus et al., 2010), Ephs and ephrins, immunoglobulin superfamily adhesion molecules, cadherins (Dalva et al., 2007) and integrins (Dityatev et al., 2010).

The purpose of this article is to review the literature to date on the regulation of synaptic plasticity by the integrins. This class of CAMs are heterodimers consisting of one of eighteen α and one of eight β subunits, which associate into 24 different combinations, and interact with extracellular matrix proteins or counter receptors on adjacent cells. The integrins are bidirectional, allosteric signalling molecules capable of activating intracellular signalling pathways in response to changes in the extracellular environment (outside-in signalling) or altering cell adhesion as a consequence of intracellularly generated stimuli (inside-out signalling). They have well established roles in a large variety of cellular processes including cell survival, cell proliferation, cell motility, transcription and cytoskeletal organisation (Berrier and Yamada, 2007; Hynes, 2002; Legate et al., 2009). Given their involvement in many basic cellular processes, it is not surprising that most integrin subunits are broadly expressed in many tissues. Although none of the subunits is neural specific, a subset is also expressed in the brain at moderate levels, and a few are enriched at synapses (Table 1). Accumulating evidence suggests that the integrins play important roles in synaptic plasticity, particularly in LTP consolidation (Chan et al., 2003, 2006; Huang et al., 2006; Staubli et al., 1998), albeit other functions have also been described (Charrier et al., 2010; Chavis and Westbrook, 2001; Cingolani and Goda, 2008; Cingolani et al., 2008).

Table 1.

Localisation of integrin subunits in the hippocampal formation.

| Integrin subunit | Pairing with | Cellular localisation | Subcellular localisation | Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β1 | α1–11, αV | Pyramidal neurons, granule cells, glial cells | Apical dendrites | IHC | Grooms et al. (1993) |

| ISH | Pinkstaff et al. (1998) | ||||

| ISH | Pinkstaff et al. (1999) | ||||

| RT-PCR | Chan et al. (2003) | ||||

| IF | Shi and Ethell (2006) | ||||

| FACS | Cahoy et al. (2008) * | ||||

| β3 | αV, αIIb | Pyramidal neurons, granule cells | Synaptic | IF | Chavis and Westbrook (2001) |

| RT-PCR | Chan et al. (2003) | ||||

| IF, SB | Shi and Ethell (2006) | ||||

| IHC | Kang et al. (2008) | ||||

| β5 | αV | Pyramidal neurons, glial cells | Synaptic | ISH | Pinkstaff et al. (1999) |

| RT-PCR | Chan et al. (2003) | ||||

| IF, SB | Shi and Ethell (2006) | ||||

| FACS | Cahoy et al. (2008) * | ||||

| β8 | αV | Granule cells, glial cells | Presynaptic, dendritic spines | IHC, SB, EM | Nishimura et al. (1998) |

| FACS | Cahoy et al. (2008) * | ||||

| α3 | β1 | Pyramidal neurons | Apical dendrites | ISH | Pinkstaff et al. (1999) |

| RT-PCR, IHC | Chan et al. (2003) | ||||

| FACS | Cahoy et al. (2008) * | ||||

| α5 | β1 | Pyramidal neurons, granule cells | Apical dendrites | ISH | Pinkstaff et al. (1999) |

| IHC | Bi et al. (2001) | ||||

| RT-PCR | Chan et al. (2003) | ||||

| α8 | β1 | Pyramidal neurons, interneurons | Dendritic spines | IHC, EM | Einheber et al. (1996) |

| ISH | Pinkstaff et al. (1999) | ||||

| αV | β1,β3, β5, β6, β8 | Pyramidal neurons, granule cells, glial cells | Dendrites | ISH | Pinkstaff et al. (1999) |

| RT-PCR | Chan et al. (2003) | ||||

| FACS | Cahoy et al. (2008) * | ||||

| IHC | Kang et al. (2008) |

IHC = immunohistochemistry, ISH = in situ hybridisation, RT-PCR = reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, IF = immunofluorescence, SB = subcellular fractionation, FACS = fluorescent-activated cell sorting, EM = electron microscopy

refers to the full forebrain.

2. Integrins as regulators of Hebbian synaptic plasticity

2.1. RGD peptides

The well established function of integrins in cell–cell and cell–matrix adhesion provided the impetus for investigating whether these CAMs play a role in the synaptic structural changes associated with LTP (Lee et al., 1980). Early studies made use of peptides containing the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) sequence found in extracellular matrix proteins, such as fibronectin, and recognised by many integrin subtypes, including those present in neurons (Ruoslahti, 1996). Application of RGD peptides to acute hippocampal slice preparations compromised LTP, which after an initial robust potentiation, decayed back to baseline levels in 15–30 min, while the baseline transmission was not affected (Staubli et al., 1990). These results provided the first evidence that the integrins targeted by RGD peptides have a role in stabilising LTP. Later studies confirmed these results, illustrating a dose-dependency of RGD peptides and the reversibility of the effects (Xiao et al., 1991). Furthermore, peptides carrying the sequence (Gly-Ala-Val-Ser-Thr-Ala), derived from the fibronectin binding site of integrins, showed the same effects as RGD peptides on LTP stabilisation, indicating that integrin-matrix recognition events are required for the switch of potentiation into a non-decremental state (Bahr et al., 1997). RGD peptides administered 1–10 min after LTP induction also reduced LTP stabilisation, providing further proof that the effects were independent of LTP induction (Bahr et al., 1997; Staubli et al., 1998). If applied 25 min after LTP induction, RGD peptides were however unable to disrupt LTP. Therefore, there appears to be a defined time window of 10–25 min after induction in which integrins are responsible for LTP stabilisation (Staubli et al., 1998). LTP was also disrupted with the disintegrins echistatin and triflavin, RGD containing peptides from snake venom with a much higher affinity to integrins than short synthetic RGD peptides (Kd ~ 1 nM–0.1 μM) (Chun et al., 2001). As opposed to integrins, NCAM and L1, which belong to the immunoglobulin superfamily of adhesion molecules, are required at an earlier stage of LTP development and stabilisation, because LTP is reduced by compounds that interfere with NCAM and L1 interactions only if used within 10 min from LTP induction (Luthl et al., 1994).

Taken together, the above data are consistent with a model in which integrins are specifically involved in LTP stabilisation. However, recent findings provide a more complex picture. Application of RGD peptides to cultured hippocampal neurons increases the number and length of dendritic spines, while decreasing the number of F-actin clusters (Shi and Ethell, 2006). These effects are partially blocked by function blocking antibodies against integrins (ITG) β1/β3, and appear to be mediated by a NMDAR and CaMKII pathway, which is suggestive of a possible role for integrins in the structural changes associated with LTP. Furthermore, the importance of NMDAR and Ca2+ signalling in the integrin-dependent spine structural changes is highlighted by the finding that application of RGD peptides increases NMDAR phosphorylation and NMDAR-mediated synaptic responses (Bernard-Trifilo et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2003). Notably, all prior studies that employed RGD peptides in acute slices to investigate the role of integrins in LTP have reported no effects of these peptides on baseline synaptic responses (e.g. Bahr et al., 1997). However, later studies have shown that infusion of the same peptides results in an increase in both the slope and amplitude of AMPAR-dependent postsynaptic potentials (Kramar et al., 2003). The reason for this apparent discrepancy is not clear.

RGD peptides have been valuable in probing the synaptic function of integrins on fast time scales (minutes). However, it is worth-while noting that some studies have reported integrin-independent effects of these compounds. For example, RGD peptides can induce apoptosis by directly binding intracellular pro-caspase-3 (Buckley et al., 1999), and in hippocampal pyramidal neurons, they might increase synaptic NMDAR currents by directly interacting with NMDARs under certain experimental conditions (Cingolani et al., 2008). It is therefore necessary to employ alternative methods, such as function blocking antibodies and genetic manipulations of integrin expression (see below), to validate that integrins are indeed responsible for the synaptic effects of RGD peptides.

2.2. Function blocking antibodies

Several integrin subunits involved in the consolidation of LTP have been identified using function blocking antibodies. Infusion of antibodies against ITGα5, but not ITGαV or ITGα2 resulted in a similar decay of LTP as observed with RGD peptides (Chun et al., 2001). Function blocking antibodies were also used to identify specific roles in LTP stabilisation for ITGα3 (Kramar et al., 2002) and ITGβ1 (Kramar et al., 2006). Although anti-ITGα3 antibodies induced a small and not statistically significant reduction in LTP levels, subsequent low frequency stimulation could revert LTP more efficiently in slices treated with anti-ITGα3 antibodies (Kramar et al., 2002). Application of neutralising antibodies against ITGβ1 produced a rapid decline of LTP induced by theta burst stimulation (TBS) to baseline levels within 10–15 min and also prevented TBS-induced actin polymerisation associated with LTP consolidation (Kramar et al., 2006). Collectively, these findings suggest that without α3β1 integrins, LTP remains in some sort of unconsolidated state that is vulnerable to disruption.

2.3. Genetic disruption of integrin function in mice

Mutant mice deficient in the expression of specific integrin subunits have helped to identify which integrins are involved in synaptic plasticity, and importantly, such mice have also provided a means to correlate any effects on LTP with behavioural changes. Single heterozygote mice confirmed a role for ITGα3, but not ITGα5 or ITGα8 in LTP; however, in triple heterozygote mice (ITGα3/+;ITGα5/+;ITGα8/+), LTP was more markedly reduced than in ITGα3/+ mice (Chan et al., 2003). This suggests that integrin subunits are able to compensate for each other to some degree. Reduced pair-pulse facilitation (PPF) was observed in double ITGα3/+;ITGα5/+ and in triple ITGα3/+;ITGα5/+;ITGα8/+ heterozygotes, indicating a possible increase in presynaptic release probability associated with perturbation of α subunit expression. A number of behavioural tests revealed deficits only in triple ITGα3/+;ITGα5/+;ITGα8/+ heterozygous animals: hippocampal-dependent spatial memory was impaired while amygdala-dependent cued and contextual fear conditioning, the latter being also dependent on hippocampal function, were intact. Therefore, a reduction in ITGα3, ITGα5 and ITGα8 expression appears to affect a specific subset of hippocampal processes.

Conditional homozygous knockout of ITGβ1 in CA1 pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus using floxed ITGβ1/CaMKII-cre mice decreased postsynaptic AMPAR responses under basal conditions and LTP, while presynaptic parameters were not affected (Chan et al., 2006). Interestingly, behavioural tests revealed specific deficits in hippocampal-dependent working memory, while spatial memory was unaffected. Although ITGβ1 is likely to be the major subunit for ITGα3, ITGα5 and ITGα8 in the hippocampus (Hynes, 2002), ITGα3/+;ITGα5/+;ITGα8/+ mice showed behavioural deficits (see above) that are different from those of ITGβ1 conditional knockout mice. Such divergent results may reflect the differences arising from global reduction in ITGα3, ITGα5 and ITGα8 versus a more specific ablation of ITGβ1 mainly in CA1 pyramidal neurons.

In another study (Huang et al., 2006), floxed ITGβ1 mice were also crossed with emx1 (empty spiracles homolog 1)-cre mice resulting in an earlier developmental reduction of ITGβ1 in hippocampal neurons (and glial cells) than that obtained with CaMKII-cre mice. This early ablation of ITGβ1 also resulted in LTP deficits. In addition, PPF was increased at short interpulse intervals and the rate of blockade of synaptic NMDAR currents by the open channel blocker MK-801 was delayed, denoting a decrease in release probability. Moreover, the size of the synaptic responses declined more readily during high and low frequency stimulation (HFS and LFS) in ITGβ1 mutants, suggestive of a limited availability of releasable synaptic vesicles or impaired mobilisation of vesicles into the releasable pool in these mutant mice. Importantly, differences were also observed in the size of NMDAR-mediated responses across a range of stimulation frequencies, which could conceivably account for the observed LTP deficits upon loss of ITGβ1. In contrast, analysis of synaptic transmission in CaMKII-cre;(f)β1/(f)β1 mice did not reveal any abnormalities in PPF or in response to HFS; however, deficits were observed with LFS. Because differences in synaptic transmission in response to LFS are generally indicative of changes in the reserve vesicle pool, these data suggest that, in CaMKII-cre;(f)β1/(f)β1 mice, the reserve vesicle pool size or alternatively the mobilisation of vesicles from the reserve to the releasable pool, is significantly reduced. As mentioned above, similarly to emx1-cre;(f)β1/(f)β1 mice, CaMKII-cre;(f)β1/(f)β1 mice also exhibit deficits in LTP, suggesting that the requirement of ITGβ1 for LTP is not secondary to some unspecified developmental role for ITGβ1. Like CaMKII-cre;(f)β1/(f)β1 mice, CaMKII-cre;(f)α3/(f)α3 mice exhibit deficits in LTP and working memory, but not spatial memory (Chan et al., 2007). In contrast, CaMKII-cre;(f)α8/(f)α8 mice do not show any memory deficits (Chan et al., 2010), but still have reduced LTP. These observations seem to suggest differential functions for α3β1 and α8β1 integrins.

2.4. What role do integrins play in LTP?

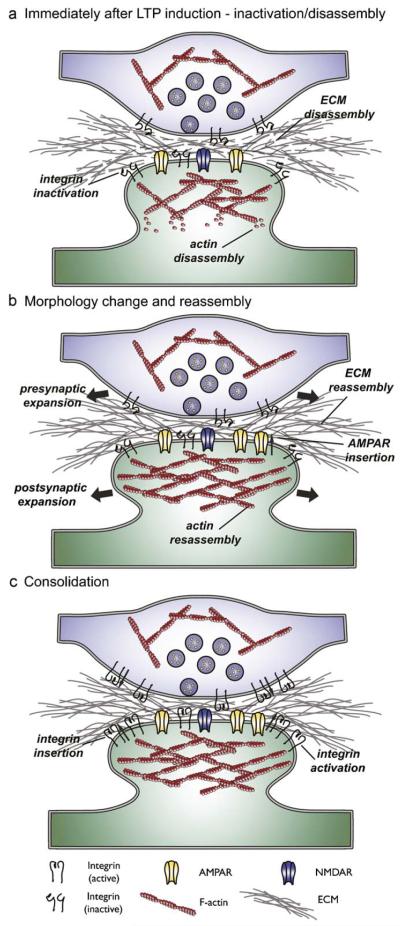

The limited temporal window of effectiveness of RGD peptides in impairing LTP (Bahr et al., 1997; Staubli et al., 1998), combined with their lack of effect on baseline transmission (but see Kramar et al., 2003) and LTP induction points to the existence of a cryptic RGD binding motif that is only revealed for a short period of time after tetanic stimulation. This is consistent with a role of integrins in stabilising new synaptic structures associated with the transition into long-term consolidation of LTP. Studies using function blocking antibodies or genetic disruption of specific integrin subunits are also consistent with this model, showing a steady decline in LTP after an apparently normal initial potentiation and without effects on baseline synaptic transmission (Table 2). Importantly, integrins have also been shown to drive actin polymerisation after LTP induction, which appears to be necessary for LTP consolidation (Kramar et al., 2006). Collectively, these observations lead to the following proposal for integrin function in LTP: LTP induction results in the disassembly of actin filaments and synaptic adhesive contacts (including those mediated by integrins), which allows for the physical expansion of dendritic spines and the accommodation of new AMPARs into the postsynaptic membrane. This new configuration is then stabilised through integrin-mediated re-assembly of actin networks and adhesive contacts (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Effects of integrin disruption related to Hebbian plasticity.

| Integrin | Manipulation | Effects | Unaffected | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RGD peptides | ||||

| RGD | RGDS(1 mM) | ↓E-LTP stabilisation (15–30 min to baseline) |

Baseline responses, induction | Staubli et al. (1990) |

| RGD | GRGDSP, RGDS (0.05–10 mM), 60–90 min before TBS |

↓E-LTP stabilisation (decays over 40 min), dose-dependancy (0.08, 0.35 and 1.0 mM), washout (+90min) |

Baseline responses, induction | Xiao et al. (1991) |

| RGD | GAVSTA (mimics matrix binding domain of RGDS-binding integrins), GRGDSP, RGDS (0.2–1 mM)* |

GAVSTA (0.8–1 mM 50–90 min before TBS): ↓E-LTP stabilisation (decays over 40 min), GRGDSP (0.5 mM 1 min after TBS): ↓E-LTP stabilisation (decays over 80–~120 min), RGDS (1 mM 10 min after TBS): ↓E-LTP stabilisation (decays over ~60 min) |

GAVSTA: baseline responses, postsynaptic burst responses, NMDAR EPSP, GRGDSP: baseline responses |

Bahr et al. (1997) |

| RGD | GRGDSP (0.5–2.0 mM)* | ↓E-LTP stabilisation (GRGDSP before 25 min post TBS) |

Baseline responses, initial potentiation, postsynaptic burst responses |

Staubli et al. (1998) |

| RGD | GRGDNP (β1 > β3,1 mM), GPenGRGDSPCA (β3 > β1, 1 mM), trifavin (10 μM), echistatin (1,5, 10 μM)* |

↓E-LTP stabilisation (GRGDNP, GPenGRGDSPCA, echistatin, triflavin) |

Baseline responses | Chun et al. (2001) |

| Function blocking antibodies | ||||

| ITGα5 | Anti-α2, α5, αV, β1 (non-function blocking) (0.05–0.2 mg/ml)* |

↓E-LTP stabilisation (anti-α5) | Baseline responses | Chun et al. (2001) |

| ITGα3 | Anti–α3 (0.2 mg/ml)* | ↓E-LTP stabilisation (with 5Hz stim) |

Baseline responses | Kramar et al. (2002) |

| ITGβ1 | Anti-β1 (0.2 mg/ml)* | ↓E-LTP stabilisation (correlation with actin polymerisation) |

Kramar et al. (2006) | |

| ITGβ1, ITGβ3 | GRGDTP (0.5 mM), anti-β1 (10 μg/ml), anti-β3 (10 μg/ml) |

↓ in the GRGDTP induced increase in dendritic spine elongation/number and decreased F-actin cluster number with anti-β1/β3 application |

Shi and Ethell (2006) | |

| Genetic disruption | ||||

| ITGα3, ITGα5 and ITGα8 | Single and combined heterozygotes |

↓E-LTP stabilisation (α3, α3;α5, α3;α8, α3;α5;α8) ↓PPF (α3;α5, α3;α5;α8), ↓ spatial memory (α3;α5;α8) |

I/O (ITGα3), cued and contextual fear conditioning (α3/α5/α8) |

Chan et al. (2003) |

| ITGβ1 | CaMKII-cre × f(β1)/f(β1) mice | ↓AMPAR transmission, ↓E-LTP stabilisation, ↓working memory |

PPF, postsynaptic burst responses, cued and contextual fear conditioning, spatial memory |

Chan et al. (2006) |

| ITGβ1 | Emx1-cre × f(β1)/f(β1) mice CaMKII-cre × f(β1)/f(β1) mice |

Emx1-cre × f(β1)/f(β1): ↑PPF (short intervals), ↓NMDAR input–output curve, ↓HFS responses, ↓LFS responses, ↓E-LTP stabilisation, CaMKII-cre × f(β1)/f(β1): ↓LFS responses, ↓E-LTP stabilisation |

Emx1-cre × f(β1)/f(β1): input–output curve, CaMKII-cre × f(β1)/f(β1): baseline responses, PPF, HFS responses |

Huang et al. (2006) |

| ITGα3 | CaMKII-cre × f(α3)/f(α3) mice | ↓E-LTP stabilisation, ↓working memory |

Input–output curve, PPF, postsynaptic burst responses, mGluR-LTD, spatial memory |

Chan et al. (2007) |

| ITGα8 | CaMKII-cre × f(α8)/f(α8) mice | ↓E-LTP stabilisation | Input–output curve, PPF, LTD (LFS), spatial memory, working memory |

Chan et al. (2010) |

Within manipulation column indicates local pressure injection of compounds. All studies used acute hippocampal slice preparations, except Shi and Ethell (2006) where dissociated hippocampal neurons preparations were studied.

Fig. 1.

Model of how integrins might consolidate LTP. (A) Synapse immediately after the induction of LTP, showing the presynaptic axon terminal (top, blue) filled with synaptic vesicles, and the postsynaptic compartment (bottom, green) with ionotrophic glutamate receptors at the cell surface and actin cytoskeleton, both of which are normally stabilised by integrin interactions with the extracellular matrix. LTP induction results in the disengagement of integrins, and disassembly of both the postsynaptic actin network and ECM. (B) Morphological changes and reassembly after LTP induction: disengagement of integrins, and depolymerisation of the postsynaptic actin network allows for the physical expansion of the postsynaptic compartment (which is associated with a concurrent expansion of the presynaptic terminal), and accommodates the insertion of AMPARs into the postsynaptic membrane. Integrin signalling then controls the polymerisation of the actin cytoskeleton. ECM is reassembled. (C) Consolidation: after a period of instability new integrins are inserted and engage with the ECM to stabilise the new synaptic morphology and function. See text for details. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

2.5. Different integrins, different roles?

Studies to date provide some evidence that different integrin subunits have distinct roles in synaptic function. Mice heterozygous for the ITGα3 null allele show deficits in LTP but not PPF (Chan et al., 2003). In contrast, as discussed earlier, α3/+;α5/+ mice have deficits in both LTP and PPF, while α3/+;α8/+ mice show normal PPF (Chan et al., 2003). This suggests that ITGα5 may be more involved in some aspects of presynaptic function. Notably, these studies of integrin mutants have involved recordings in hippocampal slices that assess synaptic transmission from a population of synapses from single cells or, in case of extracellular recordings, from population of neurons. Establishing the potential functional specialisations of different integrin subtypes would require a better understanding of how different integrin subtypes are expressed amongst neuronal populations. Moreover, for single cells, it would be important to know whether all synapses express the same complement of integrins; if they are heterogeneously present, then it would be of interest to determine the underlying basis for the differential expression of integrin subtypes at each synapse.

A recent study has provided clear evidence of separate roles for different integrin subunits at individual synapses (Charrier et al., 2010). Inhibition of either ITGβ1 or ITGβ3 with function blocking antibodies has opposing actions on the synaptic dwell time of glycine receptors in cultured spinal cord inhibitory neurons. Whereas antibodies against ITGβ1 make glycine receptors more mobile in and outside synapses, antibodies against ITGβ3 have the peculiar effect to increase glycine receptor mobility at extrasynaptic sites and decrease it at synapses. As a consequence, inhibition of ITGβ1 adhesion reduces the synaptic dwell time of glycine receptors and synaptic glycine currents, whereas inhibition of ITGβ3 adhesion produces the exact opposite effects. Such opposing activities of ITGβ1 and ITGβ3 may be used by neurons to fine-tune inhibitory synaptic tone to modulate network excitability (Charrier et al., 2010). It would be of great interest to identify the physiological extracellular ligands of ITGβ1 and ITGβ3 that function under such conditions.

3. Conclusions and future directions

Integrins have a wide range of roles in a variety of cellular systems (Berrier and Yamada, 2007; Hynes, 2002; Legate et al., 2009). In this review, we have outlined an important function for integrins in regulating the ability of neurons to adjust synaptic strength in response to activity. In particular, we have focused on the role of integrins in Hebbian plasticity, such as LTP. Taken together, it appears that ITGβ1, ITGα3, ITGα5 and ITGα8 all have important roles in the stabilisation of LTP, possibly through the consecutive disassembly and reassembly of adhesive and cytoskeletal elements which may provide a secure new configuration for the long term incorporation of new AMPARs.

Recent work has identified a role for ITGβ3 in another form of synaptic plasticity called homeostatic synaptic scaling, a compensatory mechanism used by neurons to scale up the abundance of synaptic AMPARs in response to chronic activity deprivation (Cingolani and Goda, 2008; Cingolani et al., 2008). It appears that, under basal conditions, ITGβ3 stabilises AMPARs at the postsynaptic membrane as these receptors are selectively endocytosed upon disruption of ITGβ3-ECM interactions. Importantly, neurons lacking ITGβ3 are unable to scale up synaptic AMPARs in response to chronic activity deprivation. These studies provide a first comprehensive description of how integrins regulate AMPAR trafficking and homeostatic synaptic plasticity. It will be of interest to ascertain whether ITGβ3 is also involved in other forms of synaptic plasticity, or whether distinct integrins mediate different types of synaptic plasticity. For example, ITGβ1 could be mainly involved in Hebbian-type plasticity whereas ITGβ3 might play a preferential role in homeostatic plasticity.

In summary, the challenge now is to further define the roles that individual integrins play at synapses. This includes whether separate integrins have distinct functions in different types of plasticity, whether they have specific pre- or postsynaptic roles, and how such cellular functions of integrins may relate to changes in plasticity and behaviour. Moreover, which molecular mechanisms are activated by integrins to bring about these modifications at the level of the individual synapse need to be clarified, as well as the specific ECM alterations that target individual integrins to initiate the changes.

Acknowledgements

Research in the authors’ laboratory is supported by the Medical Research Council and by grants from the Royal Society International Joint Projects scheme and the European Union Seventh Framework Programme under grant agreement no. HEALTH-F2-2009-241498 (“EUROSPIN” project).

References

- Abraham WC, Williams JM. LTP maintenance and its protein synthesis-dependence. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2008;89:260–268. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahr BA, Staubli U, Xiao P, Chun D, Ji ZX, Esteban ET, Lynch G. Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser-selective adhesion and the stabilization of long-term potentiation: pharmacological studies and the characterization of a candidate matrix receptor. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:1320–1329. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-04-01320.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard-Trifilo JA, Kramar EA, Torp R, Lin CY, Pineda EA, Lynch G, Gall CM. Integrin signaling cascades are operational in adult hippocampal synapses and modulate NMDA receptor physiology. J. Neurochem. 2005;93:834–849. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrier AL, Yamada KM. Cell–matrix adhesion. J. Cell. Physiol. 2007;213:565–573. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi X, Lynch G, Zhou J, Gall CM. Polarized distribution of alpha5 integrin in dendrites of hippocampal and cortical neurons. J. Comp. Neurol. 2001;435:184–193. doi: 10.1002/cne.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley CD, Pilling D, Henriquez NV, Parsonage G, Threlfall K, Scheel-Toellner D, Simmons DL, Akbar AN, Lord JM, Salmon M. RGD peptides induce apoptosis by direct caspase-3 activation. Nature. 1999;397:534–539. doi: 10.1038/17409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahoy JD, Emery B, Kaushal A, Foo LC, Zamanian JL, Christopherson KS, Xing Y, Lubischer JL, Krieg PA, Krupenko SA, Thompson WJ, Barres BA. A transcriptome database for astrocytes, neurons, and oligodendrocytes: a new resource for understanding brain development and function. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:264–278. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4178-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CS, Chen H, Bradley A, Dragatsis I, Rosenmund C, Davis RL. Alpha8-integrins are required for hippocampal long-term potentiation but not for hippocampal-dependent learning. Genes Brain Behav. 2010;9:402–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00569.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CS, Levenson JM, Mukhopadhyay PS, Zong L, Bradley A, Sweatt JD, Davis RL. Learning and Memory. Vol. 14. Cold Spring Harbor; NY: 2007. Alpha3-integrins are required for hippocampal long-term potentiation and working memory; pp. 606–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CS, Weeber EJ, Kurup S, Sweatt JD, Davis RL. Integrin requirement for hippocampal synaptic plasticity and spatial memory. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:7107–7116. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-18-07107.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CS, Weeber EJ, Zong L, Fuchs E, Sweatt JD, Davis RL. Beta 1-integrins are required for hippocampal AMPA receptor-dependent synaptic transmission, synaptic plasticity, and working memory. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:223–232. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4110-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charrier C, Machado P, Tweedie-Cullen RY, Rutishauser D, Mansuy IM, Triller A. A crosstalk between beta1 and beta3 integrins controls glycine receptor and gephyrin trafficking at synapses. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13:1388–1395. doi: 10.1038/nn.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavis P, Westbrook G. Integrins mediate functional pre- and postsynaptic maturation at a hippocampal synapse. Nature. 2001;411:317–321. doi: 10.1038/35077101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun D, Gall CM, Bi X, Lynch G. Evidence that integrins contribute to multiple stages in the consolidation of long term potentiation in rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2001;105:815–829. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani LA, Goda Y. Differential involvement of beta3 integrin in pre- and postsynaptic forms of adaptation to chronic activity deprivation. Neuron. Glia Biol. 2008;4:179–187. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X0999024X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani LA, Thalhammer A, Yu LM, Catalano M, Ramos T, Colicos MA, Goda Y. Activity-dependent regulation of synaptic AMPA receptor composition and abundance by beta3 integrins. Neuron. 2008;58:749–762. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citri A, Malenka RC. Synaptic plasticity: multiple forms, functions, and mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:18–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlhaus R, Hines RM, Eadie BD, Kannangara TS, Hines DJ, Brown CE, Christie BR, El-Husseini A. Overexpression of the cell adhesion protein neuroligin-1 induces learning deficits and impairs synaptic plasticity by altering the ratio of excitation to inhibition in the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 2010;20:305–322. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalva MB, McClelland AC, Kayser MS. Cell adhesion molecules: signalling functions at the synapse. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:206–220. doi: 10.1038/nrn2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dityatev A, Schachner M, Sonderegger P. The dual role of the extracellular matrix in synaptic plasticity and homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010;11:735–746. doi: 10.1038/nrn2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einheber S, Schnapp LM, Salzer JL, Cappiello ZB, Milner TA. Regional and ultrastructural distribution of the alpha 8 integrin subunit in developing and adult rat brain suggests a role in synaptic function. J. Comp. Neurol. 1996;370:105–134. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960617)370:1<105::AID-CNE10>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grooms SY, Terracio L, Jones LS. Anatomical localization of beta 1 integrin-like immunoreactivity in rat brain. Exp. Neurol. 1993;122:253–259. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Shimazu K, Woo NH, Zang K, Muller U, Lu B, Reichardt LF. Distinct roles of the beta 1-class integrins at the developing and the mature hippocampal excitatory synapse. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:11208–11219. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3526-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang WS, Choi JS, Shin YJ, Kim HY, Cha JH, Lee JY, Chun MH, Lee MY. Differential regulation of osteopontin receptors CD44 and the alpha(v) and beta(3) integrin subunits, in the rat hippocampus following transient forebrain ischemia. Brain Res. 2008;1228:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.06.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramar EA, Bernard JA, Gall CM, Lynch G. Alpha3 integrin receptors contribute to the consolidation of long-term potentiation. Neuroscience. 2002;110:29–39. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00540-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramar EA, Bernard JA, Gall CM, Lynch G. Integrins modulate fast excitatory transmission at hippocampal synapses. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:10722–10730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210225200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramar EA, Lin B, Rex CS, Gall CM, Lynch G. Integrin-driven actin polymerization consolidates long-term potentiation. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:5579–5584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601354103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KS, Schottler F, Oliver M, Lynch G. Brief bursts of high-frequency stimulation produce two types of structural change in rat hippocampus. J. Neurophysiol. 1980;44:247–258. doi: 10.1152/jn.1980.44.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legate KR, Wickstrom SA, Fassler R. Genetic and cell biological analysis of integrin outside-in signaling. Genes Dev. 2009;23:397–418. doi: 10.1101/gad.1758709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B, Arai AC, Lynch G, Gall CM. Integrins regulate NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic currents. J. Neurophysiol. 2003;89:2874–2878. doi: 10.1152/jn.00783.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthl A, Laurent JP, Figurov A, Muller D, Schachner M. Hippocampal long-term potentiation and neural cell adhesion molecules L1 and NCAM. Nature. 1994;372:777–779. doi: 10.1038/372777a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura SL, Boylen KP, Einheber S, Milner TA, Ramos DM, Pytela R. Synaptic and glial localization of the integrin alphavbeta8 in mouse and rat brain. Brain Res. 1998;791:271–282. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkstaff JK, Detterich J, Lynch G, Gall C. Integrin subunit gene expression is regionally differentiated in adult brain. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:1541–1556. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-05-01541.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkstaff JK, Lynch G, Gall CM. Localization and seizure-regulation of integrin beta 1 mRNA in adult rat brain. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1998;55:265–276. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozo K, Goda Y. Unraveling mechanisms of homeostatic synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2010;66:337–351. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruoslahti E. Integrin signaling and matrix assembly. Tumour Biol. 1996;17:117–124. doi: 10.1159/000217975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Ethell IM. Integrins control dendritic spine plasticity in hippocampal neurons through NMDA receptor and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-mediated actin reorganization. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:1813–1822. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4091-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staubli U, Chun D, Lynch G. Time-dependent reversal of long-term potentiation by an integrin antagonist. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:3460–3469. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03460.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staubli U, Vanderklish P, Lynch G. An inhibitor of integrin receptors blocks long-term potentiation. Behav. Neural Biol. 1990;53:1–5. doi: 10.1016/0163-1047(90)90712-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano GG. The self-tuning neuron: synaptic scaling of excitatory synapses. Cell. 2008;135:422–435. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao P, Bahr BA, Staubli U, Vanderklish PW, Lynch G. Evidence that matrix recognition contributes to stabilization but not induction of LTP. Neuroreport. 1991;2:461–464. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199108000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RS, Regehr WG. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2002;64:355–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.092501.114547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]