Abstract

A common quail (Coturnix coturnix) from a private keeping died unexpectedly and showed a moderate lymphocytic infiltration of the colonic mucosa associated with numerous protozoa-like objects at the pathological examination. These organisms were further identified using chromogenic in situ hybridization (ISH) and gene sequencing. ISH was performed on paraffin embedded tissue sections and produced a positive signal using a probe specific for the 18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene of the order Trichomonadida, but remained negative with probes specific for the 18S rRNA gene of the common bird parasites Histomonas meleagridis, Tetratrichomonas gallinarum or Trichomonas gallinae. The trichomonads were found on the mucosal surface, inside the crypts and also immigrating into the lamina propria mucosae. DNA was extracted from the paraffin embedded tissue and the entire 18S rRNA gene, ITS-1 region, 5.8S rRNA gene, ITS-2 region and a part of the 28S rRNA gene were sequenced using primer walking. The acquired sequence showed 95% homology with Tritrichomonas foetus, a trichomonad never described in birds. A phylogenetic analysis of a part of the 18S rRNA gene or of the ITS-1, 5.8S and ITS-2 region clearly placed this nucleotide sequence within the family of Tritrichomonadidae. Therefore, the authors propose the detection of a putative new Tritrichomonas sp. in the intestine of a common quail.

Keywords: Coturnix coturnix, Enteritis, Chromogenic in situ hybridization, Quail, Trichomonads

Flagellate protozoa of the phylum Parabasala are of high importance in veterinary medicine infecting a wide range of animal hosts. Several trichomonad species such as Histomonas meleagridis, Trichomonas gallinae, Tetratrichomonas gallinarum and Cochlosoma anatis are well known bird pathogens (Daugschies, 2006). H. meleagridis causes necrotizing typhlohepatitis in turkeys and has been associated with mortality and reduced egg production in chickens (Esquenet et al., 2003). T. gallinarum may also cause typhlohepatitis in galliform and anseriform birds (Richter et al., 2010). T. gallinae mainly infects the family of Columbidae leading to necrotizing lesions in the upper digestive tract. C. anatis has been linked with enteritis and runting of ducklings (Daugschies, 2006).

There is only one report of an infection with a Tritrichomonas species (proposed name: Tritrichomonas gigantica) from a quail (Navarathnam, 1970). There are no further reports on this species and it is currently not listed among the valid species which need to be characterized both, morphologically and genetically. Also many other trichomonad isolates which were originally classified under the names of e.g. Tritrichomonas eberthi, Tritrichomonas anatis and Tritrichomonas anseris (Levine, 1973) were later re-classified as other trichomonads like T. gallinarum or T. gallinae (Mehlhorn et al., 2009), based on morphological and sequence analyses. For correct species identification and classification of trichomonads of the phylum Parabasala the sequence analysis of the small subunit ribosomal RNA (rRNA) proved to be a reliable method (Cepicka et al., 2010).

In this study an infection with unknown trichomonads in the intestine of a quail (Coturnix coturnix) which was found during histopathological examination, was analyzed using in situ hybridization and gene sequencing and classified using phylogenetic analysis.

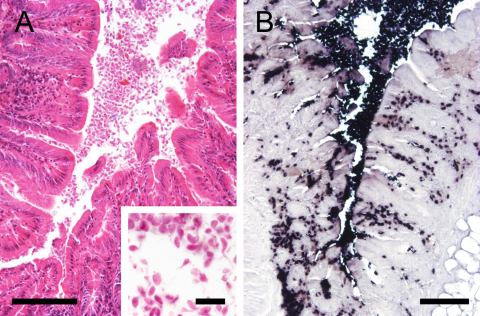

A female common quail (C. coturnix) from a private keeping died unexpectedly and was subjected to necropsy. Necropsy revealed a moderate dilatation of both cardial ventricles, hyperemia of major parenchymatous organs and some ascarid nematodes in the intestinal lumen. At standard histopathological examination there was a moderate diffuse lymphocytic infiltration of the mucosa of the large intestine associated with a large number of protozoal objects which were present within the colonic lumen but multifocally also invaded the lamina propria (Fig. 1A). In the histological slides the oval to pear-shaped protozoa had a mean size of 4–6 μm by 8–14 μm. Occasionally the proximal part of the axostyle and the parabasal body with a size of 1–2 μm and very faint single flagella could be discerned (Fig. 1A, inset). Based on these morphological criteria they were identified as trichomonads.

Fig. 1.

Hematoxylin–eosin (HE) staining and chromogenic in situ hybridization (ISH) of the colon of a quail. (A) In the HE staining large amounts of parasite-like objects are visible in the gut lumen. Bar = 100 μm. Inset: trichomonads are oval to pear-shaped with a discernible axostyle and parabasal body. Bar = 30 μm. (B) In the ISH using the OT probe distinct black signals corresponding to the parasite-like objects can be seen in the intestinal lumen, crypts and lamina propria mucosae. Bar = 100 μm.

The small intestine showed no signs of inflammation and harbored only very few of the above described trichomonads. Additionally, there were distinct mucosal lymphatic follicles in the proventriculus.

To further classify these protozoa a chromogenic in situ hybridization (ISH) was conducted. Four different oligonucleotide probes (Table 1) were used which were specific for a part of the 18S rRNA gene of (I) all relevant members of the order Trichomonadida (OT probe) (Mostegl et al., 2010), (II) T. gallinarum (Tetra gal probe) (Richter et al., 2010), (III) H. meleagridis (Histom probe) (Liebhart et al., 2006) or (IV) T. gallinae (Tricho gal probe). For the design of the Tricho gal probe an alignment of all available 18S rRNA sequences of T. gallinae was carried out. A probe sequence homologuous for all aligned sequences was chosen. This sequence was further analyzed using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast.cgi) to exclude unintentional cross-reactivity. Subsequently, the probe was synthesized and labeled with digoxigenin (Eurofins MWG Operon, Ebersberg, Germany). Afterwards the probe was tested analogous to the protocols for chromogenic ISH of the above mentioned probes (Chvala et al., 2006) on sections of a formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded culture of T. gallinae. Additionally, a variety of other trichomonads were used to exclude cross-reactivity, namely H. meleagridis, Hypotrichomonas acosta, Monocercomonas colubrorum, Pentatrichomonas hominis, T. gallinarum, Trichomitus batrachorum, Tritrichomonas foetus and Tritrichomonas augusta (Mostegl et al., 2010). Furthermore, a number of other common pathogens including protozoa, fungi, bacteria and viruses as listed by Mostegl et al. (2010) were tested negative with the new probe.

Table 1.

List of in situ hybridization probes used with name of probe, nucleotide sequence, probe concentration and publication of the original description.

| Probe name | Nucleotide sequence and length | Concentration | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|

| OT | 5′-TTG CGG TCG TAG TTC CCC CAG AGC CCA AGA ACT-3′ (40 nt) | 20 ng/ml | Mostegl et al. (2010) |

| Tetra gal | 5′- T CAC CGC ACT GGA AAG GTG CGA TCC TAT TCA CAA TGG-3′ (35 nt) | 20 ng/ml | Richter et al. (2010) |

| Histom | 5′-CCA ACT ACG TTA AAA ATT ATA AGA GTA GCT TTT CAT T-3′ (40 nt) | 20 ng/ml | Liebhart et al. (2006) |

| Tricho gal | 5′-T CGG TAC GGT GGA AAA CCG TAC CCC TAT CCA CAA TAC-3′ (29 nt) | 20 ng/ml | This paper |

In the ISH using the OT probe the parasite-like objects detected in the HE staining revealed strong positive signals (Fig. 1B). The trichomonads were easily discernible due to their intensive black to purple staining. The protozoa were found in large amounts in the intestinal lumen, on the gut surface, inside the crypts and in the lamina propria mucosae. All other probes (Tetra gal, Tricho gal and Histom-2) did not show any positive signal suggesting the presence of an unusual trichomonad species in this bird.

For species identification PCR assays followed by gene sequencing analyses were performed on DNA extracted from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded intestinal tissue sections. First, two published primer pairs (PP) PP3 (Mostegl et al., 2010) and PP8 (partly based on Mostegl et al., 2011) (Table 2), able to amplify a sequence within the 18S rRNA gene specific for trichomonads, were used. According to the BLAST analysis data three different T. foetus sequences (accession nos. M81842, AF466751 and AY055800) were chosen for their high homology and used for all further alignments. Based on the conducted alignment a primer walking was carried out with 11 newly designed primer pairs (Table 2). All newly designed primer pairs were analyzed via BLAST prior to usage to exclude unintentional cross-reactivity. The primer walking was designed to amplify the entire 18S rRNA and 5.8S rRNA genes including the internal transcribed spacer regions (ITS) 1 and 2 and a part of the 28S rRNA gene.

Table 2.

Name, sequence and previous publication of primers used for primer walking in this study; all primers were designed on a Tritrichomonas foetus sequence with the GenBank accession number: M81842.

| Primer pair | Forward sequence | Reverse sequence | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|

| PP1 | 57F: 5′-TTG ATA CTT GGT TGA TCC TGC-3′ | 217R: 5′-CAG AAT TAC TGC TGC TAT CC-3′ | This paper |

| PP2 | 154F: 5′-ACA CGC TCA GAA TCT ACT TG-3′ | 408R: 5′-CGT GGA TAT AGT CGC TAT CT-3′ | This paper |

| PP3 | 331F: 5′-GGT AGG CTA TCA CGG GTA AC-3′ | 578R: 5′-ACT YGC AGA GCT GGA ATT AC-3′ | Mostegl et al. (2010) |

| PP4 | 451F: 5′-GGT GGT AAT GAC CAG TTA CA-3′ | 711R: 5′-CAT ACT GCG CTA AGT CAT TC-3′ | This paper |

| PP5 | 553F: 5′-GCT GCG GTA ATT CCA GCT CT-3′ | 830R: 5′-CCC TCT AGG TAG ATG CTT TC-3′ | This paper |

| PP6 | 690F: 5′-AGG AAT GAC TTA GCG CAG TA-3′ | 964R: 5′-CCC AAG AAC TAT GAT TTC TC-3′ | This paper |

| PP7 | 909F: 5′-ACA GGG GCT TGT CCT TTT AT-3′ | 1192R: 5′-TCG CTC GTT ATC TGA ATC AA-3′ | This paper |

| PP8 | 1064F: 5′-AAC TTA CCA GGA CCA GAT GT-3′ | 1357F: 5′-CAG CAT CTC TTT GAT CCT AAC A-3′ | Based on Mostegl et al. (2011) |

| PP9 | 1279F: 5′-AGC AAT AAC AGG TCC GTG AT-3′ | 1445R: 5′-ACA AGG GAT TCC TGG TTC AT-3′ | This paper |

| PP10 | 1327F: 5′-GCG CTA CAA TGT TAG GAT CA-3′ | 1548R: 5′-CGC AAG GTC CGA TAA TTT CA-3′ | This paper |

| PP11 | 1506F: 5′-CTC CTA CCG ATT GGA TGA CT-3′ | 1744R: 5′-GTG TAA GAA GCC AAG ACA TC-3′ | This paper |

| PP12 | 1596F: 5′-CAA GGT AAC GGT AGG TGA AC-3′ | 1897R: 5′-AAA TTA ATA TGG GTT ACT GT-3′ | This paper |

| PP13 | 1753F: 5′-ACG TTG CAT AAT GCG ATA AG-3′ | 2031R: 5′-TCG GTC GCA CTT ACT AAG AG-3′ | This paper |

For PCR three 10 μm thick formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue sections were used. After dewaxing with xylene, washing with ethanol and air-drying, DNA was extracted with the Nexttec Clean Column Kit (Nexttec, Leverkusen, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. All PCR reactions included 10 μl HotMasterMix (5Prime, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), 0.4 μM of each primer, 2 μl template DNA and distilled water to a volume of 25 μl. The PCR reaction was started with a denaturation step at 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 60 °C for 30 s (except for PP2, PP3, PP4, PP5, and PP11 with 58 °C) and elongation at 72 °C for 1 min, followed by a final elongation step at 72 °C for 10 min. No positive control was used. The negative control was a PCR mixture containing distilled water instead of template DNA. 10 μl of the PCR reaction was analyzed on a 2% Tris acetate–EDTA–agarose gel. Subsequent to staining with ethidium bromide the gel was visualized with the BioSens gel documentation system (GenXpress, Wiener Neudorf, Austria). PCR products showing the estimated size were sequenced in both directions according to Bakonyi et al. (2004), except that the DNA purification step was performed using the DyeEx 2.0 Spin Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) instead of ethanol precipitation. The forward and reverse sequences were aligned and combined resulting in a consensus sequence. In a final step the acquired partial sequences (excluding outer primer regions) were compiled to the entire18S rRNA gene, ITS-1 region, 5.8S rRNA gene, and ITS-2 region sequence.

In total a sequence of 1982 bp was generated. This sequence included the entire 18S rRNA gene, ITS-1 region, 5.8S rRNA gene, ITS-2 region and a part of the 28S rRNA gene. The BLAST analysis showed the highest homologies of ∼95% with T. foetus sequences (M81842, AF466749, AF466750, AF466751, U17509, AY055799, AY055800). The generated sequence has been submitted to the GenBank with the accession number JF927156.

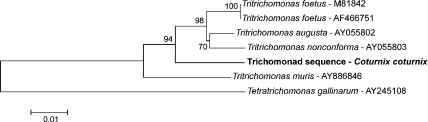

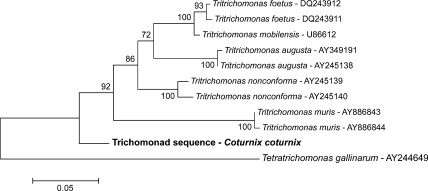

Based on the fact that the majority of sequences found in the GenBank either contain the 18S rRNA gene or the ITS-1, 5.8S rRNA and ITS-2 region, two phylogenetic analyses were conducted with the respective sequences. Both phylogenetic analyses were carried out using the MEGA4 program (Tamura et al., 2007) applying the neighbor-joining method (Saitou and Nei, 1987). A bootstrap analysis of 1000 replicates was used to test the stability of the achieved trees. The nucleotide substitution model of Kimura-2-parameter was used to calculate the genetic distance between each pair of sequences.

In the phylogenetic analysis based on the part of the 18S rRNA (Fig. 2) the trichomonad sequence of the quail was placed within the family of Tritrichomonadidae supported by a bootstrap value of 94. The phylogenetic tree of the ITS-1, 5.8S, ITS-2 region (Fig. 3) displayed the unknown trichomonad sequence near the family of Tritrichomonadidae but not in the same close relationship as the 18S rRNA gene tree depicted.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of the trichomonad sequence acquired in this study (written in bold) based on the nucleotide sequence of the 18S rRNA gene. The tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree of the trichomonad sequence acquired in this study (written in bold) based on the nucleotide sequence of the ITS-1 region, 5.8S rRNA gene and ITS-2 region. The tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method.

Taken together, this work presents a necropsy case of a common quail which showed a severe colonization of the large intestine with trichomonads as an incidental finding at histopathological examination. The invading intestinal parasites were positive with a chromogenic ISH for Trichomonadida but negative in similar assays for known avian trichomonads. Therefore, the presence of a newly not yet described trichomonad species had to be considered. Subsequent gene sequence analyses of rRNA genes revealed a similarity of 95% with a sequence of T. foetus, a trichomonad found in cattle, pigs and cats. No T. foetus-like sequence has ever been reported from birds. There is only one report of a tritrichomonad infection (with a species originally named Tritrichomonas gigantica) in a common quail (Navarathnam, 1970). However, neither an isolate nor sequence data are available from this species. Also, the morphologic variations detected for T. gigantica may lead to the assumption that more than one trichomonad species was included in this original description. There have been no other studies confirming the validity of this species and its existence may be considered doubtful. However it cannot be excluded that the present study and the earlier report relate to the same organism.

Both phylogenetic analyses placed the obtained trichomonad species either within or in close relation to the family of Tritrichomonadidae. This result strongly suggests the detection of an as yet undescribed Tritrichomonas species in the intestine of a common quail. Since no unfixed tissue material is available from this bird a complete species description including morphological analysis and cultivation of the trichomonads was not possible. The large numbers of luminal and invading protozoa associated with a diffuse lymphocytic infiltration of the colonic mucosa indicate a pathogenic potential of the parasites. Further studies on quail trichomonads are needed to determine whether this case presented only an aberrant infection of a single animal, or if the newly described tritrichomonas are inherent parasites of quails.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Jolanta Kolodziejek for helping with the phylogenetic analyses and Karin Fragner and Klaus Bittermann for their excellent technical support. Cultured samples of different trichomonad species serving as positive controls were kindly provided by Prof. Jaroslav Kulda, Charles University Prague, and Prof. Michael Hess, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna. This work was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) grant P20926.

References

- Bakonyi T., Gould E.A., Kolodziejek J., Weissenböck H., Nowotny N. Complete genome analysis and molecular characterization of Usutu virus that emerged in Austria in 2001: comparison with the South African strain SAAR-1776 and other flaviviruses. Virology. 2004;328:301–310. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepicka I., Hampl V., Kulda J. Critical taxonomic revision of parabasalids with description of one new genus and three new species. Protist. 2010;161:400–433. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chvala S., Fragner K., Hackl R., Hess M., Weissenböck H. Cryptosporidium infection in domestic geese (Anser anser f. domestica) detected by in-situ hybridization. J. Comp. Pathol. 2006;134:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugschies A. Protozoeninfektionen des Nutzgeflügels. In: Schnieder T., editor. Veterinärmedizinische Parasitologie. Parey; Stuttgart, Germany: 2006. pp. 576–580. [Google Scholar]

- Esquenet C., De Herdt P., De Bosschere H., Ronsmans S., Ducatelle R., Van Erum J. An outbreak of histomoniasis in free-range layer hens. Avian Pathol. 2003;32:305–308. doi: 10.1080/0307945031000097903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine N.D. Burgess; MN: 1973. Protozoan Parasites of Domestic Animals and of Man. p. 94. [Google Scholar]

- Liebhart D., Weissenböck H., Hess M. In-situ hybridization for the detection and identification of Histomonas meleagridis in tissues. J. Comp. Pathol. 2006;135:237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlhorn H., Al-Quraishy S., Aziza A., Hess M. Fine structure of the bird parasites Trichomonas gallinae and Tetratrichomonas gallinarum from cultures. Parasitol. Res. 2009;105:751–756. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1451-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostegl M.M., Richter B., Nedorost N., Maderner A., Dinhopl N., Kulda J., Liebhart D., Hess M., Weissenböck H. Design and validation of an oligonucleotide probe for the detection of protozoa from the order Trichomonadida using chromogenic in situ hybridization. Vet. Parasitol. 2010;171:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostegl M.M., Richter B., Nedorost N., Maderner A., Dinhopl N., Weissenböck H. Investigations on the prevalence and potential pathogenicity of intestinal trichomonads in pigs using in situ hybridization. Vet. Parasitol. 2011;178:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarathnam E.S. A new species of Tritrichomonas from the caecum of the bird Coturnix coturnix Linneaus. Riv. Parassitol. 1970;31:9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter B., Schulze C., Kämmerling J., Mostegl M., Weissenböck H. First report of typhlitis/typhlohepatitis caused by Tetratrichomonas gallinarum in three duck species. Avian Pathol. 2010;39:499–503. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2010.518137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N., Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Dudley J., Nei M., Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]