Abstract

In this retrospective study 102 cats were analyzed for the presence of trichomonads in intestinal tissue sections using chromogenic in situ hybridization (CISH). Two intestinal trichomonad species are described in cats: Pentatrichomonas hominis and Tritrichomonas foetus. While P. hominis is considered a mere commensal, T. foetus has been found to be the causative agent of feline large-bowel diarrhea. For the detection of both agents within intestinal tissue CISH assays using three different probes were performed. In the first CISH run a probe specific for all relevant members of the order Trichomonadida (OT probe) was used. In a second CISH run all positive samples were further examined on three consecutive tissue sections using the OT probe, a probe specific for the family of Tritrichomonadidae (Tritri probe) and a newly designed probe specifically detecting P. hominis (Penta hom probe). In total, four of the 102 cats were found to be positive with the OT probe. Thereof, one cat gave a positive reaction with the P. hominis probe and three cats were positive with the T. foetus probe. All Trichomonas-positive cats were pure-bred and between 8 and 32 weeks of age. In one cat positive for T. foetus large amounts of parasites were found in the gut lumen and invading the intestinal mucosa. The species of the detected trichomonads were confirmed by polymerase chain reaction and nucleotide sequencing of a part of the 18S ribosomal RNA gene. In this study, the usefulness of CISH to detect intestinal trichomonads within feline tissue samples was shown. Additionally, the specific detection of P. hominis using CISH was established. Generally, it was shown that CISH is well suited for detection and differentiation of trichomonosis in retrospective studies using tissue samples.

Keywords: Cat, Chromogenic in situ hybridization, Trichomonads, Tritrichomonas foetus, Pentatrichomonas hominis

1. Introduction

Several trichomonad species of the phylum Parabasala are well-known pathogens in veterinary medicine. In cats two trichomonad species have received scientific attention, Tritrichomonas foetus (family Tritrichomonadidae) and Pentatrichomonas hominis (family Trichomonadidae) (Cepicka et al., 2010). P. hominis (Honigberg et al., 1968) is known to inhabit the digestive tract, mainly the large intestine, of several vertebrates such as humans, dogs, monkeys, guinea pigs and cats (Wenrich, 1944; Jongwutiwes et al., 2000). In former studies P. hominis was erroneously considered to be the causative agent of the chronic large-bowel diarrhea in cats (Romatowski, 1996; Gookin et al., 1999; Romatowski, 2000). After experimental induction of transient diarrhea in specific pathogen free cats by T. foetus it became unanimously accepted that the disease was due to T. foetus and not P. hominis (Gookin et al., 2001). T. foetus is mainly known as the causative agent of bovine trichomonosis (Parsonson et al., 1976), a venereal disease in heifers. It could be demonstrated that cattle are susceptible to infection with T. foetus isolated from cats and vice versa causing comparable lesions (Stockdale et al., 2007, 2008). A recent study suggested the recognition of genetically distinct ‘cattle genotype’ and ‘cat genotype’ of T. foetus (Šlapeta et al., 2010). Furthermore, T. foetus was found to be the same species as Tritrichomonas suis (Lun et al., 2005), and was shown to be a facultative pathogen in the large intestine of pigs (Mostegl et al., 2011).

In cats, T. foetus colonizes the ileum, caecum and colon in close proximity to the mucosal surface (Yaeger and Gookin, 2005). Although the presence of T. foetus in the feline reproductive tract is regarded as unlikely (Gray et al., 2010), there is a single report of a natural T. foetus infection in the feline uterus (Dahlgren et al., 2007). Cats affected with T. foetus were usually less than 12 months of age with only single cases ranging up to 13 years of age (Gookin et al., 1999; Gunn-Moore et al., 2007; Stockdale et al., 2009), lived in multi-cat households, and were predominantly pure-bred cats (Gookin et al., 1999, 2004). Infections of cats with T. foetus were first described in the USA (Gookin et al., 1999), but several reports followed from other countries, such as the UK (Mardell and Sparkes, 2006; Gunn-Moore et al., 2007), Germany (Gookin et al., 2003b; Schrey et al., 2009), Switzerland (Frey et al., 2009), the Netherlands (Van Doom et al., 2009), Italy (Holliday et al., 2009), Greece (Xenoulis et al., 2010), Australia (Bissett et al., 2008, 2009; Bell et al., 2010), New Zealand (Kingsbury et al., 2010), and Korea (Lim et al., 2010).

Trichomonads in cats can be diagnosed by examination of fecal smears, after cultivation (Gookin et al., 2003a; Hale et al., 2009), or by species-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays on fecal samples targeting a part of the 18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene (Gookin et al., 2002, 2007). Another newly described method for diagnosing trichomonads directly within formalin-fixed and paraffin wax-embedded tissue sections is fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) specific for a part of the 18S rRNA. With this technique the correlation of the presence of the protozoan organism with tissue lesions can easily be assessed. However, the auto-fluorescence of blood cells, which are within the size range of trichomonads, is the main disadvantage of the FISH technique (Gookin et al., 2010). Chromogenic in situ hybridization (CISH) does not display this disadvantage and has been shown to be a reliable method for detecting trichomonads (Mostegl et al., 2010), and T. foetus in particular (Mostegl et al., 2011), within formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue sections.

In this study, formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded intestinal tissue sections of 102 cats were examined retrospectively, using three different CISH probes specific for all trichomonads, all members of the family Tritrichomonadidae or P. hominis to assess the involved species, the quantity of parasite cells and the associated lesions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cat specimen

In total 102 intestinal formalin-fixed and paraffin wax-embedded tissue sections of cats (55 male, 45 female and 2 of unknown sex) from the archive of the Institute of Pathology and Forensic Veterinary Medicine were used. Included were 96 samples of cats obtained at necropsy and 6 biopsy or organ samples which were examined between 1997 and 2010. All chosen cats suffered from diarrhea and were between 4 weeks and 2 years of age. Represented breeds were European shorthair (n = 67), Persian (n = 7), European longhair (n = 4), Siamese, Maine Coon, British shorthair (each n = 3), Ragamuffin, Burmese (each n = 2), Exotic shorthair, Bengal, Oriental shorthair, Norwegian Forest Cat, Ragdoll, Abyssinian (each n = 1) and 5 cats of unknown breed. All but one tissue sample included small and large intestine, with the exceptional case comprising only small intestinal tissue. At conventional histological examination of the intestine presence of trichomonad-like organisms was registered in only two of the cases (cat 2 and cat 4).

2.2. P. hominis probe design

A CISH oligonucleotide probe for the specific detection of P. hominis was designed (Penta hom probe). First, homology studies comprising all 18S rRNA sequences of P. hominis available in GenBank were performed using the Sci Ed Central (Scientific & Educational software, Cary NC, USA) software package. A region of complete homology in all P. hominis sequences was chosen as probe. The selected Penta hom probe sequence was 5′-GTG AAC GTT GAA ACG TAG GGA CAT TGC TGT CCA ATT CCG-3′. Subsequently, the probe sequence was subjected to the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST; www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast.cgi) to search against the GenBank and exclude unintentional cross-reactivity. The Penta hom probe was synthesized and labeled with digoxigenin (Eurofins MWG Operon, Ebersberg, Germany). Afterwards, it was tested on a formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded protozoal culture containing P. hominis. Negative results were achieved with other protozoal cultures including Histomonas meleagridis, Hypotrichomonas acosta, Monocercomonas colubrorum, Tetratrichomonas gallinarum, Trichomonas gallinae, Trichomitus batrachorum, Tritrichomonas augusta and T. foetus (Mostegl et al., 2010). To rule out further cross-reactivity the probe was tested on various embedded cultures and tissue samples including several species of other protozoan parasites, fungi, bacteria and viruses as listed in Mostegl et al. (2010).

2.3. Chromogenic in situ hybridization

Two CISH runs were performed on the feline formalin-fixed and paraffin wax-embedded tissue sections including small and large intestine. In the first run an oligonucleotide probe (order Trichomonadida (OT) probe) specific for all known trichomonads (Mostegl et al., 2010) was used. All positive samples were subjected to a second CISH run, performed on three consecutive tissue sections using the OT probe, a probe specific for the family of Tritrichomonadidae (Tritri probe) (Mostegl et al., 2011) and the newly designed Penta hom probe.

CISH was performed in accordance with a previously published protocol (Chvala et al., 2006). Briefly, 3 μm thin formalin fixed and paraffin embedded tissue sections were dewaxed and rehydrated. In a first step the slides were treated with 2.5 μg/ml proteinase K (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) diluted in Tris-buffered saline for 30 min at 37 °C for proteolysis. After the treatment the tissue slides were rinsed in distilled water to remove the proteinase K and dehydrated in alcohol (95% and 100%), followed by air-drying. The slides were incubated over night at 40 °C with the hybridization mixture, 100 μl of which was composed of 50 μl formamide, 20 μl 20× standard saline citrate buffer (SSC), 12 μl distilled water, 10 μl dextran sulfate (50%, w/v), 5 μl boiled herring sperm DNA (50 mg/ml), 2 μl Denhardt's solution and 1 μl OT, Tritri or Penta hom probe, respectively, at a concentration of 20 ng/ml. On the second day, the slides were washed in decreasing concentrations of SSC (2× SSC, 1× SSC and 0.1× SSC; 10 min each) for removal of unbound probe. Afterwards the sections were incubated with anti-digoxigenin-AP Fab fragments (Roche) (1:200) for 1 h at room temperature. The hybridized probe was visualized using the color substrates 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-inodyl phosphate (BCIP) and 4-nitro blue tetrazolium chloride (NBT) (Roche). After 2 h of incubation the color development was stopped using TE buffer (pH 8.0). In a last step the slides were counterstained in haematoxylin and mounted under coverslips using Aquatex (VWR International, Vienna, Austria).

2.4. Polymerase chain reaction and nucleotide sequencing

The cases that yielded a positive CISH signal were confirmed by partial sequencing of the 18S rRNA gene. DNA was extracted from the paraffin embedded tissue and a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was conducted as detailed by Mostegl et al. (2011). The primer pair described in that paper flanks a region of 234 bp of the 18S rRNA gene that can be used to differentiate between various trichomonad species including T. foetus and P. hominis. The resulting sequence was subjected to BLAST search for identification of the present trichomonad species.

3. Results

In total, four of 102 cats were found positive with the OT probe.

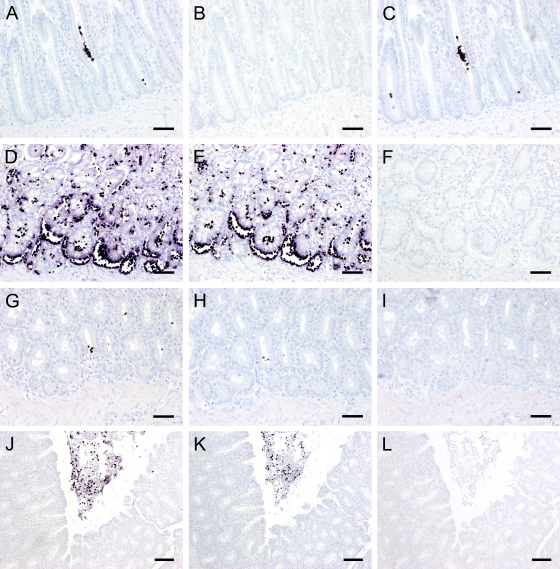

Cat 1, a male Siamese of eight weeks, had been necropsied after suffering from anorexia and pasty diarrhea. At microscopic examination a moderate dilation of mucosal crypts with occasional accumulation of luminal eosinophilic material was found in small intestinal samples. The leukocytic infiltration of the mucosa was within the normal range. Large intestine was not available in this case. With the CISH of the small intestine using the OT probe scattered trichomonads stained dark purple within the crypts (Fig. 1A). No positive signal could be detected when the Tritri probe was used (Fig. 1B). CISH with the Penta hom probe stained trichomonads in these crypts which had also a positive reaction with the OT probe (Fig. 1C), suggesting the presence of P. hominis. This was confirmed by partial sequencing of the 18S rRNA gene yielding a sequence with 100% similarity only to published P. hominis sequences.

Fig. 1.

Chromogenic in situ hybridization (CISH) of intestinal tissue sections of four cats using three different oligonucleotide probes. (A, D, G and J) OT probe specific for the order Trichomonadida; (B, E, H and K) Tritri probe specific for the family of Trichomonadidae; (C, F, I and L) Penta hom probe specific for Pentatrichomonas hominis. Positively stained trichomonads are dark purple. (A–C) CISH of cat 1; (A and C) trichomonads (P. hominis) are present within the intestinal crypt lumina. (D–F) CISH of cat 2; (D and E) large amounts of trichomonads (T. foetus) are present within the intestinal crypts and immigrating into the lamina propria mucosae. (G–I) CISH of cat 3; (G and H) scattered trichomonads (T. foetus) are visible within the intestinal crypts. (J–L) CISH of cat 4; (J and K) large amounts of positively stained trichomonads (T. foetus) are found within the gut lumen. (A–I) Bar = 80 μm. (J–L) Bar = 150 μm. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

Cat 2, a male Persian of four months of age, underwent necropsy due to inanition and diarrhea. The microscopic examination of the large intestine showed moderate crypt hyperplasia and mild crypt dilation in the mucosa. Approximately 10% of crypts were filled predominately with eosinophils and fewer neutrophils. About one third of crypts were filled with large amounts of parasite-like objects especially in basal areas. In the lamina propria neutrophils were mildly increased and there were acute superficial petechiae in the mucosa. By CISH of the large intestine with the OT probe abundant strongly stained trichomonads, not only present within the crypt lumen but also invading the lamina propria mucosae, were found (Fig. 1D). CISH with the Tritri probe also detected large amounts of dark purple stained trichomonads within the crypts and immigrating into the lamina propria mucosae (Fig. 1E). No positively stained protozoal parasites were detected with the Penta hom probe (Fig. 1F), indicating the presence of T. foetus. In the small intestine single parasites were identified between crypt epithelium and lamina propria. However, no histopathological changes were evident in the examined areas. Nucleotide sequencing confirmed the presence of T. foetus in the intestinal samples by yielding a sequence identical to corresponding published sequences only from T. foetus.

Cat 3, a female Ragamuffin of four months of age, was subjected to necropsy with the tentative diagnosis of feline parvoviral infection. During the standard histopathological examination no evidence for a parvovirus infection was found. In the small intestine a mild crypt dilation and mild increase in mucosal lamina propria lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils and eosinophils was present. The large intestinal mucosa showed a mild crypt dilation with moderate amounts of mucus. The leukocytic infiltration was normal in the examined slides. With CISH of the small and large intestine using the OT probe scattered positively stained trichomonads were detected within the crypts (Fig. 1G). With the Tritri probe the same protozoal organisms were found to be positive (Fig. 1H). There were no positive signals with the Penta hom probe (Fig. 1I), suggesting the presence of T. foetus. This was confirmed by PCR with the resulting amplicon having a nucleotide sequence that was 100% similar to corresponding regions of published T. foetus sequences.

Several intestinal samples of cat 4, a female Persian cat of eight months of age, were submitted by a veterinarian due to enteritis completely resistant to therapeutic approaches. The microscopic examination of the colon showed a mild crypt dilation and mild increase of lamina propria neutrophils. In the gut lumen along the mucosal surface there were large amounts of parasite-like objects intermingled with large amounts of mucus, many neutrophils, some desquamated epithelial cells and erythrocytes and few eosinophils and macrophages. The CISH with the OT probe showed positive staining of the parasite-like objects present in the gut lumen (Fig. 1J). The same picture was observed when the intestinal sample was analyzed using the Tritri probe (Fig. 1K). No positively stained parasites were found with the Penta hom probe (Fig. 1L), indicating the presence of T. foetus. This result could be confirmed by PCR and nucleotide sequencing producing a sequence identical to those published for T. foetus. In the small intestine no protozoa were detected by CISH although there were mildly increased lamina propria neutrophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells.

Taken together, four of 102 cats were found positive for trichomonads. Thereof, three cats were found to be positive with the OT and the Tritri probe (two cats after necropsy, one organ submission) suggesting the presence of T. foetus, and in one cat (after necropsy) the OT and the Penta hom probe gave positive signals indicating the detection of P. hominis.

4. Discussion

In this study the suitability of the CISH technique for the detection of trichomonads in intestinal samples of cats was investigated. Three different CISH probes were shown to successfully detect trichomonads in cats. The OT (Mostegl et al., 2010) and the Tritri probe (Mostegl et al., 2011) had been shown in a previous study to identify trichomonads and particularly T. foetus in pigs. The third newly designed Penta hom probe was found to be suitable to specifically detect P. hominis in the intestine of cats. No background staining was observed using these three probes. Additionally, it was shown that the CISH method with the described probes is not only a reliable technique in necropsy samples but also for analyzing biopsy samples. The specificity of the probes in the routinely processed diagnostic material had been further confirmed by PCR and sequencing of the amplification products. Compared to the recently published FISH technique for trichomonad identification and localization (Gookin et al., 2010), CISH has the advantage of not displaying any auto-fluorescence of red blood cells, which are in the size range of trichomonads and have been mentioned to be a big disadvantage in detecting trichomonads especially in birds. However, previous studies indicated that CISH is a convenient method of visualizing trichomonads in various bird species (Richter et al., 2010; Amin et al., 2011). The sensitivity of the technique is considered good, as (1) it proofed to stain each single trichomonad cell in paraffin-embedded culture samples (Mostegl et al., 2010, 2011) and (2) it revealed trichomonad infections in cases which would not have been diagnosed by histological examination alone.

In previous investigations intestinal trichomonosis in cats has been primarily found in young, pure-bred cats, which lived in multi-cat households. Unfortunately, in none of the 102 examined cats information about the housing conditions was available. In total, only 4 of the 102 cats were found positive for trichomonads. Interestingly, all positive cases were pedigree cats. In accordance with literature findings, this observation may point to a higher susceptibility of pure-bred cats for this parasitosis (Kuehner et al., 2011). In one of the four trichomonad positive cats (cat 1, Siamese, 8 weeks of age) P. hominis was found. The amount of protozoan parasites was small and apart from a mild crypt distension there were no pathological lesions in this case. This would be in line with other reports, postulating that P. hominis were a mere commensal in the intestine of cats (Levy et al., 2003).

In the three other cats positive for trichomonads, an infection with T. foetus was identified. In cat 3 (Ragamuffin, 16 weeks of age) only scattered T. foetus cells were present within the intestinal crypt lumen and there were only very mild pathological lesions suggesting also other causes than the present trichomonads to be responsible for the clinical signs. In both, cat 2 (Persian, 16 weeks of age) and cat 4 (Persian, 32 weeks of age) large amounts of T. foetus were visualized, with the difference that in cat 4 the organisms were present exclusively in the gut lumen, while in cat 2 the parasites were also found in the crypt lumina and immigrating into the lamina propria mucosa. These differences in tissue localization of the trichomonads are also reflected by variable degrees of colonic lesions, which were more pronounced in case 2. Although the small number of positive cases is far from drawing reliable conclusions, it is tempting to assume that the severity of histological lesions is directly correlated with the number and location of the parasites.

As the amount of trichomonads was quite small in two of the positive samples, it also is not unlikely that low-grade infestations might have escaped detection by examining only one colonic section per animal. Trichomonads are very fragile and easily washed away during tissue processing. It has been shown in prior studies that a minimum of 6 tissue sections needs to be examined in coproscopically proven positive animals in order to have a ≥95% confidence interval that the parasites will be identified in at least one section (Yaeger and Gookin, 2005). While CISH is probably inarguably better at finding trichomonads than routine light microscopy, also this method still relies on trichomonads being retained in the biopsy specimen and thus examination of several sections, preferably different tissue locations is recommended for future studies.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Karin Fragner and Klaus Bitterman for their excellent technical support. Positive and negative control samples for probe testing were kindly provided by Prof. Jaroslav Kulda and Prof. Michael Hess. This work was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) grant P20926.

References

- Amin A., Liebhart D., Weissenböck H., Hess M. Experimental infection of turkeys and chickens with a clonal strain of Tetratrichomonas gallinarum induces a latent infection in the absence of clinical signs and lesions. J. Comp. Pathol. 2011;144:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell E.T., Gowan R.A., Lingard A.E., McCoy R.J., Šlapeta J., Malik R. Naturally occurring Tritrichomonas foetus infections in Australian cats: 38 cases. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2010;12:889–898. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissett S.A., Gowan R.A., O’Brien C.R., Stone M.R., Gookin J.L. Feline diarrhoea associated with Tritrichomonas cf. foetus and Giardia co-infection in an Australian cattery. Aust. Vet. J. 2008;86:440–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2008.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissett S.A., Stone M.L., Malik R., Norris J.M., O’Brien C., Mansfield C.S., Nicholls J.M., Griffin A., Gookin J.L. Observed occurrence of Tritrichomonas foetus and other enteric parasites in Australian cattery and shelter cats. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2009;11:803–807. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepicka I., Hampl V., Kulda J. Critical taxonomic revision of parabasalids with description of one new genus and three new species. Protist. 2010;161:400–433. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chvala S., Fragner K., Hackl R., Hess M., Weissenböck H. Cryptosporidium infection in domestic geese (Anser anser f. domestica) detected by in-situ Hybridization. J. Comp. Pathol. 2006;134:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren S.S., Gjerde B., Pettersen H.Y. First record of natural Tritrichomonas foetus infection of the feline uterus. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2007;48:654–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2007.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey C.F., Schild M., Hemphill A., Stünzi P., Müller N., Gottstein B., Burgener I.A. Intestinal Tritrichomonas foetus infection in cats in Switzerland detected by in vitro cultivation and PCR. Parasitol. Res. 2009;104:783–788. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-1255-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gookin J.L., Birkenheuer A.J., Breitschwerdt E.B., Levy M.G. Single-tube nested PCR for detection of Tritrichomonas foetus in feline feces. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002;40:4126–4130. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.11.4126-4130.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gookin J.L., Breitschwerdt E.B., Levy M.G., Gager R.B., Benrud J.G. Diarrhea associated with trichomonosis in cats. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1999;215:1450–1454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gookin J.L., Foster D.M., Poore M.F., Stebbins M.E., Levy M.G. Use of a commercially available culture system for diagnosis of Tritrichomonas foetus infection in cats. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2003;222:1376–1379. doi: 10.2460/javma.2003.222.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gookin J.L., Levy M.G., Mac Law J., Papich M.G., Poore M.F., Breitschwerdt E.B. Experimental infection of cats with Tritrichomonas foetus. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2001;62:1690–1697. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2001.62.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gookin J.L., Stauffer S.H., Levy M.G. Identification of Pentatrichomonas hominis in feline fecal samples by polymerase chain reaction assay. Vet. Parasitol. 2007;145:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gookin J.L., Stebbins M.E., Adams E., Burlone K., Fulton M., Hochel R., Talaat M., Poore M., Levy M.G. Prevalence and risk of T. foetus infection in cattery cats (Abstract) J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2003;17:380. [Google Scholar]

- Gookin J.L., Stebbins M.E., Hunt E., Burlone K., Fulton M., Hochel R., Talaat M., Poore M., Levy M.G. Prevalence of and risk factors for feline Tritrichomonas foetus and Giardia infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42:2707–2710. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2707-2710.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gookin J.L., Stone M.R., Yaeger M.J., Meyerholz D.K., Moisan P. Fluorescence in situ hybridization for identification of Tritrichomonas foetus in formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded histological specimens of intestinal trichomonosis. Vet. Parasitol. 2010;172:139–143. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray S.G., Hunter S.A., Stone M.R., Gookin J.L. Assessment of reproductive tract disease in cats at risk for Tritrichomonas foetus infection. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2010;71:76–81. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.71.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn-Moore D.A., McCann T.M., Reed N., Simpson K.E., Tennant B. Prevalence of Tritrichomonas foetus infection in cats with diarrhoea in the UK. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2007;9:214–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale S., Norris J.M., Šlapeta J. Prolonged resilience of Tritrichomonas foetus in cat faeces at ambient temperature. Vet. Parasitol. 2009;166:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday M., Deni D., Gunn-Moore D.A. Tritrichomonas foetus infection in cats with diarrhoea in a rescue colony in Italy. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2009;11:131–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honigberg B.M., Mattern C.F., Daniel W.A. Structure of Pentatrichomonas hominis (Davaine) as revealed by electron microscopy. J. Protozool. 1968;15:419–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1968.tb02151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongwutiwes S., Silachamroon U., Putaporntip C. Pentatrichomonas hominis in empyema thoracis. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2000;94:185–186. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(00)90270-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsbury D., Marks S., Cave N., Grahn R. Identification of Tritrichomonas foetus and Giardia spp. infection in pedigree show cats in New Zealand. N. Z. Vet. J. 2010;58:6–10. doi: 10.1080/00480169.2010.65054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehner K.A., Marks S.L., Kass P.H., Sauter-Louis C., Grahn R.A., Barutzki D., Hartmann K. Tritrichomonas foetus infection in purebred cats in Germany: prevalence of clinical signs and the role of co-infection with other enteroparasites. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2011;13:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy M.G., Gookin J.L., Poore M., Birkenheuer A.J., Dykstra M.J., Litaker R.W. Tritrichomonas foetus and not Pentatrichomonas hominis is the etiologic agent of feline trichomonal diarrhea. J. Parasitol. 2003;89:99–104. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2003)089[0099:TFANPH]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S., Park S.-I., Ahn K.-S., Oh D.-S., Ryu J.-S., Shin S.-S. First report of feline intestinal trichomoniasis caused by Tritrichomonas foetus in Korea. Korean J. Parasitol. 2010;48:247–251. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2010.48.3.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lun Z.-R., Chen X.-G., Zhu X.-Q., Li X.-R., Xie M.-Q. Are Tritrichomonas foetus and Tritrichomonas suis synonyms? Trends Parasitol. 2005;21:122–125. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardell E.J., Sparkes A.H. Chronic diarrhoea associated with Tritrichomonas foetus infection in a British cat. Vet. Rec. 2006;158:765–766. doi: 10.1136/vr.158.22.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostegl M.M., Richter B., Nedorost N., Maderner A., Dinhopl N., Kulda J., Liebhart D., Hess M., Weissenböck H. Design and validation of an oligonucleotide probe for the detection of protozoa from the order Trichomonadida using chromogenic in situ hybridization. Vet. Parasitol. 2010;171:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostegl M.M., Richter B., Nedorost N., Maderner A., Dinhopl N., Weissenböck H. Investigations on the prevalence and potential pathogenicity of intestinal trichomonads in pigs using in situ hybridization. Vet. Parasitol. 2011;178:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsonson I.M., Clark B.L., Dufty J.H. Early pathogenesis and pathology of Tritrichomonas foetus infection in virgin heifers. J. Comp. Pathol. 1976;86:59–66. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(76)90028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter B., Schulze C., Kämmerling J., Mostegl M., Weissenböck H. First report of typhlitis/typhlohepatitis caused by Tetratrichomonas gallinarum in three duck species. Avian Pathol. 2010;39:499–503. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2010.518137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romatowski J. Pentatrichomonas hominis infection in four kittens. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2000;216:1270–1272. doi: 10.2460/javma.2000.216.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romatowski J. An uncommon protozoan parasite (Pentatrichomonas hominis) associated with colitis in three cats. Feline Pract. 1996;24:10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Schrey C., Mundhenk L., Gruber A., Henning K., Frey C. Tritrichomonas foetus as a cause of diarrhoea in three cats. Kleintierpraxis. 2009;54:93–96. (in German. Abstract in English) [Google Scholar]

- Šlapeta J., Craig S., McDonell D., Emery D. Tritrichomonas foetus from domestic cats and cattle are genetically distinct. Exp. Parasitol. 2010;126:209–213. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockdale H., Rodning S., Givens M., Carpenter D., Lenz S., Spencer J., Dykstra C., Lindsay D., Blagburn B. Experimental infection of cattle with a feline isolate of Tritrichomonas foetus. J. Parasitol. 2007;93:1429–1434. doi: 10.1645/GE-1305.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockdale H.D., Dillon A.R., Newton J.C., Bird R.C., BonDurant R.H., Deinnocentes P., Barney S., Bulter J., Land T., Spencer J.A., Lindsay D.S., Blagburn B.L. Experimental infection of cats (Felis catus) with Tritrichomonas foetus isolated from cattle. Vet. Parasitol. 2008;154:156–161. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockdale H.D., Givens M.D., Dykstra C.C., Blagburn B.L. Tritrichomonas foetus infections in surveyed pet cats. Vet. Parasitol. 2009;160:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.10.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Doom D.C.K., De Bruin M.J., Jorritsma R.A., Ploeger H.W., Schoormans A. Prevalence of Tritrichomonas foetus among Dutch cats. Tijdschr. Diergeneeskd. 2009;134:698–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenrich D.A. Morphology of the trichomonad flagellates in man and of similar forms in monkeys, cats, dogs, and rats. J. Morphol. 1944;74:189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Xenoulis P.G., Saridomichelakis M.N., Read S.A., Suchodolski J.S., Steiner J.M. Detection of Tritrichomonas foetus in cats in Greece. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2010;12:831–833. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaeger M.J., Gookin J.L. Histologic features associated with Tritrichomonas foetus-induced colitis in domestic cats. Vet. Pathol. 2005;42:797–804. doi: 10.1354/vp.42-6-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]