Abstract

This study charted the development of gendered personality qualities and activity interests from age 7 to age 19 in 364 first- and second-born siblings from 185 White, middle/working class families; assessed links between time in gendered social contexts (with mother, father, female peers and male peers) and gender development; and tested whether changes in testosterone moderated links between time use and gender development. Multi-level models documented that patterns of change varied across dimensions of gender and by sex and birth order and that time in gendered social contexts was generally linked to development of more stereotypical qualities. Associations between time with mother and expressivity and time with father and instrumentality were stronger for youth with slower increases in testosterone.

Gender is central in human development. Whether “it’s a girl” or “it’s a boy” is a topic of keen interest for parents-to-be, and an increasing body of work evidences differences in the ways parents treat their daughters and sons (Leaper, 2002; McHale, Crouter, & Whiteman, 2003; Ruble, Martin, & Berenbaum, 2006). Children’s gender also is marked in the world outside the home, particularly in the peer group (Leaper, 1994), and the implications of gender development are evident across the lifespan in individuals’ opportunities and choices about education, work, and family roles.

The first goal of this study was to chart the course of gender development in girls and boys across middle childhood and adolescence in two key domains: (a) gendered personality qualities, specifically, stereotypically feminine, expressive qualities such as sensitivity and kindness, and stereotypically masculine, instrumental qualities such as independence and leadership; and (b) gendered interests, including in stereotypically feminine activities such as dance and handicrafts, and stereotypically masculine activities such as sports and science. As we elaborate, these domains are central in gender development and have been linked to current and long term functioning in areas ranging from relationship quality to education achievement (Ruble et al., 2006).

Our second goal was to identify factors that explain individual differences in patterns of change. Grounding our work in an ecological perspective on the role of daily activities in development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), we focused on the amounts of time youth spend in gendered social contexts, specifically time with mother, father, and female and male peers, as these change over time, as potential correlates of the development of youth’s gendered personality qualities and interests. Gender development research also directs attention to the role of biological factors in the development of sex and individual differences. In this study we focus on the hormone, testosterone (T). To date, most researchers have focused on the role of prenatal levels of T in gender development (e.g., Berenbaum, & Hines, 1992; Hines, Golombok, Rust, Johnston, et al., 2003; Udry, 2000). We expanded on this work to study the potential role of T during the pubertal transition as a potential correlate of gender development. Then, following on work suggesting that T may set constraints on the effects of gender socialization influences (e.g., Berenbaum, & Hines, 1992; Hines et al., 2003; McHale, Shanahan, Updegraff, Crouter, & Booth, 2004; Udry, 2000), we tested whether the level or rate of increase in circulating T in early adolescence moderated the links between youth’s time in gendered social contexts and the development of their gendered personality qualities and interests.

The Development of Gendered Personality Qualities

Children’s sense of being feminine or masculine is often equated with their perceptions of their gendered personality qualities, making this a domain of interest to gender researchers (Huston, 1985). Understanding the development of qualities such as kindness and sensitivity or independence and leadership also is important because of their links with well-being and adjustment. From childhood on, stereotypically feminine, expressive qualities are important for positive social relationships (e.g., Maccoby, 1998), and stereotypically masculine, instrumental qualities, reflect experiences of self efficacy and competence that are central to psychological adjustment (e.g., Crick & Zahn-Waxler, 2003; Hoffman, Powlishta, & White, 2004).

Most research on the development of gendered personality traits is cross-sectional and suggests that boys’ and girls’ self-descriptions diverge in childhood, with sex differences persisting through adolescence as youth become increasingly aware of social definitions of gender (Ruble et al., 2006). The hypothesis that gender socialization pressures increase across the transition to adolescence (Hill & Lynch, 1983) has led researchers to focus on this developmental period, with mixed results: One study showed that sex differences in instrumentality, but not expressivity, increased from ages 11 and 12 to age 13 (Galambos, Almeida, & Petersen, 1990). Other researchers have not found a clear pattern of age-related sex differences, however (e.g., Antill, Russell, Goodnow, & Cotton, 1993). We expanded on prior work, using multi-level modeling analyses (MLM) to chart trajectories of change in expressivity and instrumentality from about age 7 to about age 19 in a sample of European American youth. Studying a relatively large sample over an extended period of time allowed us to illuminate both within-sex changes among girls and among boys as well as sex differences in patterns of change in these traits.

The Development of Gendered Interests

Gender is multi-dimensional, and its different dimensions are thought to exhibit different developmental patterns that emerge through different processes (Ruble et al., 2006). Tracking age-related changes within domains of gender thus illuminates some of the complexities of gender development (e.g., Crouter, Whiteman, McHale, & Osgood, 2007). In this study we focused on sex-typed interests as a second key domain of gender. As others have suggested, the development of gendered interests has implications for outcomes ranging from education plans and achievement, to career development and family formation (e.g., Jacobs, Lanza, Osgood, Eccles, & Wigfield, 2002).

Available data are largely cross-sectional and reveal sex differences in interests among toddlers that become more evident by early childhood (Ruble et al., 2006). Investigators have studied toy preferences as well as interests in leisure activities (sports, the arts), chores, academics, and occupations (Liben & Bigler, 2002; Edelbrock & Sugawara, 1978; Serbin, Powlishta, & Gulko, 1993). Changes over time and place in social constructions of gender, coupled with the array of interests studied, however, make it difficult to draw a unitary conclusion about the development of gendered interests (Ruble et al., 2006). Further, declines in gendered interests may emerge because interests become increasingly specialized across development (e.g. computers, not sports; drawing, not dance). Studying the “subjective value” of activities, an index that included a rating of interest as well as ratings levels of fun, utility and importance of activities, Jacobs et al. (2002) documented longitudinal declines from grade 2 to grade 12 in both girls’ and boys’ ratings of the value of math, language arts, and sports. In this study, we used an analytic approach similar to Jacobs et al. to describe changes in girls’ and boys’ interests in gendered activities from middle childhood through late adolescence.

The Social Contexts of Gender Development

From an ecological perspective, activities are both causes and consequences of development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979): Activities reflect contextually based opportunities for the development of interests and skills, social ties, and a sense of identity (Lareau, 2003; Larson & Verma, 1999; Coatsworth, Sharp, Palen, Darling, Cumsille, & Marta, 2005). Individuals’ choices about how to spend time also reflect personal dispositions and predilections (Medrich, Roizen, Rubin, & Buckley, 1982).

In keeping with these ecological ideas, gender development researchers have examined the social contexts of youth activities as both a reflection of and an impetus for gender development. Research on peer relationships documents the pervasiveness of gender segregation in middle childhood (Leaper, 1994; Maccoby, 1998), and children’s gendered interests and personality qualities have figured prominently in these discussions. In childhood, spending time with same sex peers may arise in part because of compatible interests (for instance, in rough and tumble play for boys) and personal-social qualities (for instance, expressive interpersonal styles in girls). In turn, involvement with same sex peers may promote stereotypical gender development. From a social learning perspective, children are reinforced for sex-typed behaviors and interests, and from a gender schema perspective, such experiences promote the development of cognitive constructions of self and others (Ruble et al., 2006).

Although the extent of gender segregation in children’s peer groups has been well-documented, there is less direct evidence of its implications for gender development (Leaper, 1994). One study of preschoolers found that same sex play predicted increases in sex-typed social behavior over a period of six months (Martin & Fabes, 2001). Youth become more involved with other-sex peers by adolescence (Richards, Crowe, Larson, & Swarr, 1998), but little is known about the correlates of same and other-sex peer involvement during this time. In a paper based on a subset of the current sample, we reported that time with male peers at about age 10 was a negative predictor of girls’ and boys’ stereotypically feminine academic interests (in language arts) at age 12, controlling for age 10 interests, but we found no links between time with either male or female peers and youth’s gendered personality qualities (McHale, Kim, Whiteman, & Crouter, 2004). We expanded on this work in the present study, using a more powerful analytic technique, a longer time frame, and a larger sample, to examine how changes in youth’s time with male and female peers are linked to changes in youth’s gendered interests and personality qualities from about age 7 to about age 19.

Parents also are important agents of gender socialization (Leaper, 2002). Most research on parental influences is grounded in social learning ideas and focuses on parents as role models and sources of reinforcement. From an ecological perspective, spending time with a parent of the same or other sex provides children with opportunities to observe gendered interests, personal-social qualities, and other behaviors of women and men. Consistent with a gender schema perspective, allocations of time to activities with a parent of the same or other sex also may foster the development of cognitive constructions about social roles. Prior research shows that children’s time with parents is, in fact, gendered: Beginning in infancy, children spend more time with their mothers than their fathers; by early adolescence, mothers spend more time with girls and fathers with boys (Montemayor & Brownlee, 1988); and, consistent with the gender intensification hypothesis, the latter pattern of same-sex parent-offspring involvement becomes more pronounced across the transition to adolescence (Crouter, Manke, & McHale, 1995). We know little, however, about how time with mother and father is linked to gender development. In our prior report we showed that (controlling for age 10 characteristics) girls’ time with mother at age 10 was a positive predictor of language arts grades at age 12, and time with father was a positive predictor of math grades, but a negative predictor of interest in language arts; time with father also predicted increases in girls’ instrumental personality qualities. In contrast, there were not significant associations for boys (McHale, Kim, et al., 2004). We expanded on this work in the current study.

Our prior work also revealed that family influences are not reducible to dyadic experiences with mother or with father. Instead, in a series of reports we have shown that youth’s position in the sibling constellation of a family has implications for their development, such that older and younger siblings exhibit different developmental trajectories in domains ranging from gender attitudes, to family relationships, to adjustment problems (Crouter, et al., 2007; Kim, McHale, Osgood & Crouter, 2006; Shanahan, McHale, Osgood & Crouter, 2007). These patterns suggest that younger siblings’ development may be shaped by the experiences of firstborns; this may be, in part, because both parents and younger sibling learn from firstborns’ experiences. In the face of early interest in the topic (e.g., Brim, 1958), gender development researchers have paid little attention to the role of siblings. In this study, therefore, we expanded on prior work to examine within-family differences in the development of gendered personality characteristics and interests of first-versus second-born siblings.

Bio-Social Processes in Gender Development

The biological bases of individual differences in gender development have been a focus of increasing interest (Ruble et al., 2006). “Experiments of nature” (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) provide insights into the role of abnormal levels of prenatal androgens (male hormones) in gender development (e.g., Berenbaum & Hines, 1992), and more recent studies have examined the role of prenatal T in gender development within general population samples. Hines et al. (2002), for example, reported that prenatal T was positively related to parents’ reports of girls’, but not boys’ stereotypically masculine play activities in a large sample of preschoolers. In a study of young adults, Udry (2000) found that women who had been exposed to higher prenatal T reported less gender stereotypical personal-social qualities. This study also documented the moderational role of prenatal T: At low levels of T, mothers’ encouragement of femininity was linked to more stereotypical development, but at high levels of T, mothers’ encouragement was unrelated to gender development.

We know less about the role of post-natal T in gender development. Existing research shows that boys and girls are similar in their levels of T in early childhood, but that T levels rise and begin to diverge in middle childhood, with boys’ levels rising more steeply than girls’, and levels for both reaching a peak in later adolescence (Buchanan, Eccles, & Becker, 1992). Based on their review of the literature on the role of T in adolescence, Buchanan et al. (1992) proposed that young adolescents’ behavior is affected by the rapid rate of increase in T at this developmental period; once T levels off and youth become acclimated to higher levels, psychological and social influences may again become more important behavioral influences. In our prior work we found evidence for the role of T in early adolescence. T levels moderated the longitudinal links between girls’ self-rated feminine interests and their time spent in stereotypically feminine activities (dance, handicrafts) measured using a daily diary procedure, such that interests and activities were linked only among girls with low T levels (McHale, Shanahan et al., 2004). Consistent with Udry’s conclusions, we interpreted this finding to mean that high T levels may set constraints on the effects of socialization experiences like activity involvement. Although Buchanan et al.’s analysis implied that the rate of increase in T may be the important factor at the transition to adolescence, we were not able to test this hypothesis in our earlier work. Accordingly, in this study, we built on prior work to examine the role of T in early adolescence in the development of girls’ and boys’ gendered personality qualities and interests, testing the hypotheses that higher levels and/or faster increases in T would set constraints on socialization influences such that the link between youth’s time in gendered social contexts and the development of gendered traits and interests would be stronger for youth who showed lower levels and/or rates of increase in T.

Overview of Study Goals

In sum, this study was directed at two goals. First, we charted the course of the development of girls’ and boys’ gendered personality qualities (expressivity and instrumentality) and their gendered activity interests from about age 7 to about age 19. Second, we assessed factors that explained individual differences in patterns of change. To address the latter goal we measured the links between changes in youth’s gendered qualities and changes in the (gendered) social contexts of their daily activities, specifically, their time spent with mothers, fathers, and female and male peers, and we examined bio-social processes in gender development, testing whether T levels and rates of increase across early adolescence moderated the links between youth’s time spent in gendered social contexts and the development of their gendered qualities and interests.

Methods

Participants

The sample included mothers, fathers, and 364 youth who were first- or second-born siblings from 185 families that participated in a longitudinal study of family relationships. Families were recruited via letters sent home from schools in 16 districts of a northeastern state. These letters described the study and criteria for participation: always married parents with a firstborn child in the fourth or fifth grade and at least one sibling, one to three years younger. Interested families returned a postcard to the project office. Of those families who returned postcards to us and who met our criteria, over 90% agreed to participate.

Data collection began in 1995/1996. The data for the current study were drawn from the first, second, third, sixth, and seventh years of the study (termed times 1- 5 in this paper), the years in which the data of interest were collected; there was no attrition from our target sample over the course of this study period. At time 1, firstborns averaged 10.86 years of age (SD = .54; range = 9.64 -- 12.59) and secondborns averaged 8.27 years (SD = .94; range = 6.05 -- 10.30); at time 5, firstborns averaged 17.36 years of age (SD = .80; range, 15.52 – 19.02) and secondborns averaged 14.77 years (SD = 1.17, range, 12.03 – 17.40). The age range of siblings and multiple points of data collection meant that we had at least n = 15 youth at each year of age from about age 7 (i.e., age 6.5 to 7.5 years) to age 19 (i.e., age 18.5 to 19.5 years) who provided data for the analyses. Sibling dyads were divided almost equally among the four possible sex constellations, such that about half the sample was female. At time 1, the average mother and father had completed some college, M = 14.57, SD = 2.15; M = 14.67, SD = 2.40 years of education for mothers and fathers, respectively (a score of 12 indicates high school graduate, 14 indicates some college, 16 indicates college graduate), and mothers’ and fathers’ education levels were correlated, r = .56. Further, all fathers and approximately 90% of mothers were employed. Families ranged in size from 4 to 9 members (including mother and father), with about half of the sample including children younger than the two target siblings. Reflecting the demographics of their small cities, towns, and rural communities in which they resided, families were predominantly White and working and middle class. Although not representative of U.S. families, the sample comes close to capturing the racial background of families from the region (> 94% White), but comparisons with 2000 census data suggest that these families were somewhat more affluent than the average household in the region.

Procedures

We used three data collection procedures. First, we conducted home interviews with mothers, fathers and both siblings each year. At the beginning of these interviews, informed consent/assent was obtained, and families received an honorarium for participation ($100 at times 1-3; $200 at times 4 and 5). Then, family members were questioned separately about their personal qualities and family relationship experiences.

Our second procedure involved collection of saliva samples from youth and parents. At times 2, 3 and 5, family members completed a separate informed consent form and were paid an extra $25 for participation in this part of the study. Family members provided saliva samples during the home interviews (expectorating 5 mls of saliva through a plastic straw into a 20 ml sample collection vial) and upon rising on the two mornings following the home interview and samples were refrigerated immediately after collection. After the second morning collection, samples were sent to the project office where they aliquoted and stored at -80° C until assayed. Because a range of factors, such as phase of the menstrual cycle, vigorous exercise, and smoking may affect T levels (Booth, Mazur, & Dabbs 1993), family members also completed a brief questionnaire each time they provided a saliva sample.

The third data collection procedure was directed at obtaining information about youth’s daily activities. Specifically, during the three to four weeks following the home interviews each year, we conducted 7 evening telephone interviews (5 on weekday evenings, 2 on weekend evenings). During these calls, youth reported on their daily activities outside of school. During each call, youth were asked how many times they had participated in a list of about 70 activities (e.g., play sports, do handicrafts, watch TV) from the time they woke up that morning until the time of the call. For each activity reported, youth were asked how long the activity had lasted and with whom they had engaged in that activity. Calls were scheduled in the evenings so that they could report on almost all their activities during the day.

Measures

Gendered personal social qualities (expressivity and instrumentality) were measured with the Antill Trait Questionnaire (Antill, Russell, Goodnow, & Cotton, 1993), a 12-item measure on which youth used a 5-point scale to rate how well particular traits (e.g., gentle and helpful versus competitive and adventurous) described them. For this sample, across all times and across siblings, Cronbach’s alphas averaged .74 for expressivity and .60 for instrumentality, and cross-time (stability) correlations averaged r = .37 for expressivity, and r = .47 for instrumentality.

Gendered activity interests were measured by a measure adapted from Huston, McHale, and Crouter (1985). Parents (at Time 1) and youth (at each time point) used a 4-point scale to rate their interest in the same activities on which youth reported in the phone interviews. The socially constructed nature of gendered qualities means that these may vary across time and place. Accordingly, to categorize activities as stereotypically feminine and masculine, we used our data from parents, testing for sex differences in their ratings at time 1. Activities were classified as feminine if there were significant differences favoring mothers, and masculine if significant sex differences favored fathers. Feminine activities included dance, handicrafts, music, read, write, gymnastics, art, garden, swim, play card/board games, hike, go for walk, activities with pets or animals, religious activities, and language arts; masculine activities included sports, build, hunt, fish, watch T.V., social studies, math, and science. Cross time stability coefficients averaged r = .51 for feminine and r = .65 for masculine interests.

Time spent with mothers, fathers and with male and female peers was measured via data from the telephone interviews. We aggregated youth reports across all activities and across all 7 calls to create measures of the time in minutes youth reported spending with mother, with father, with one or more female peers and with one or more male peers. To assess inter-reporter reliability we calculated the correlations between the two siblings’ reports of their time in shared activities. These data suggested that, even without training, youth reports were correlated rs > .56. Stability coefficients averaged r = .30 for time with mother, r = .27 for time with father, r = .39 for time with female peers, and r = .35 for time with male peers.

Testosterone levels were based on the average of two morning saliva samples. Samples were assayed for salivary T using a double antibody radioimmunoassay for total serum T (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Webster, TX) as modified by Granger, Schwartz, Booth, and Arentz (1999) for use with saliva (see McHale, Shanahan et al., 2004 for detailed description of the assay procedure and reliability checks). For this sample, none of the factors assessed in the daily questionnaire (e.g., medication, menstrual stage) were linked to T level so these were not included as controls (McHale, Shanahan et al., 2004). Scores for T were skewed, however, and so a square-root transformation was used in the analyses.

Background and Control Factors

Parents provided information on family background characteristics at Time 1 (i.e., education, work hours, occupations, and incomes). Further, at Times 1-3 mothers rated firstborns’ pubertal development and at Times 4 and 5 youth rated their pubertal development using the 5-item Pubertal Development Scale developed by Petersen, Crockett, Richards, and Boxer (1998).

Results

Analysis Plan

To examine the developmental course and correlates of gendered personal social qualities and interests, we used an MLM strategy. This approach allowed us to take into account the nested nature of our data (i.e., individuals over time; within-family dependencies). Another advantage of MLM is that it provides for the use of unbalanced data; it is not necessary for time points to be equally spaced or for every individual to be assessed at the same points in time, and individuals can differ in age at the first point of data collection. This feature of MLM allowed us to use youth age as our index of time despite age differences among youth at each time of assessment. Choosing year of assessment as the time metric, in contrast, would have obscured the developmental patterns of interest. In the analyses, the time variable (i.e., youth’s age) was centered at age 13 (the approximate mean age across all youth, across all times of measurement). A further strength of MLM is that it provides for missing data (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002; Schafer, 1997); across all persons, variables, and time points only about 6% of participants’ scores were missing, meaning that our analyses provide good estimates of the phenomena of interest.

We began by estimating 3-level models, one for each gender development measure (i.e., expressivity, instrumentality, feminine and masculine interests) using the mixed procedure in SAS software Version 9.1. At Level 1 (within-individuals over time), we included age polynomials (i.e., linear, quadratic, and cubic terms) to describe patterns of change in gendered qualities as well as the time-varying covariates of interest (i.e., time with mother, with father, with female peers, with male peers).

Level 2 in the models (between-individuals or within-families) included individual-level time invariant characteristics that varied across siblings (youth sex and birth order). We also tested the cross-level interactions between these factors and each of the time polynomials to determine whether boys versus girls or first- versus secondborns differed in their patterns of change. In addition, we included the cross-time means for each individual on the time-varying explanatory variables (e.g., time with mother) so that we could document how changes in gendered qualities were linked to changes in the social contexts of youth activities. That is, because the (cross-time) mean coefficients reflect all between-individual variation, controlling for this variation limits the time-varying version of the variable at Level 1 to explaining within individual variation over time beyond stable individual differences (Jacobs et al., 2002; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). We also included 2 measures of T at Level 2, T at age 13 (the intercept) and rate of change in T (slope). Because we only collected saliva samples at three points in time we could not treat T as a time varying covariate at Level 1. Instead, to obtain the T rate of change index, we first ran a series of MLMs to estimate the growth curve of T. Including random linear and fixed quadratic terms provided the best fitting model for the T growth curve, and we took the residual scores on the linear slope to create the change in T index. Finally, similarly to the T factors, we included two control indices of puberty, level at age 13 and the rate of change. We used this strategy for two reasons: First, we needed to avoid a multi-collinearity problem due to the high correlation between pubertal development and age, r = .79. By taking variances in the level and rate of pubertal development, we were able to create controls that were not related to age. Further, pubertal development data were available for all five time points for firstborns, but only at two time points for secondborns. Given that boys and girls differ in pubertal development timing, in preliminary models we tested the interactions between youth sex and both puberty level and change. None of these interactions were significant so we excluded these interaction terms from the final models (Aiken & West, 1991).

Level 3 (between-families) included a family level variable common to both siblings, parent education. We included only parent education as a control at level 3 because, unlike other family demographic indices (income, parent work hours), parent education did not vary across time in this sample.

In these analyses, time-varying indices of the social contexts of youth time use were group-mean centered, i.e., centered at each individual’s cross-time mean. When the (cross-time) means were entered at Level 2, these were centered at the sample means (Kreft, Leeuw, & Aiken, 1995). In these analyses, sex and birth order were effect coded (-1 = girl and firstborn and 1 = boy and secondborn); in the case of significant interactions, as a series of follow-up slope tests, we re-ran the same models treating boys and secondborns as the reference groups (i.e., dummy coding instead of effect coding to provide for clearer interpretation). To follow up significant interactions between two continuous variables, i.e., between youth time use and T scores, we followed Aiken and West’s (1991) recommendations, comparing groups at 1 SD above and below the mean.

For each index of gender development, we begin by describing the overall growth curves from about age 7 to age 19 and whether and how these were moderated by sex or birth order. Next, we report on the links between youth’s time spent in gendered social contexts and gender development in each domain, and we describe findings pertaining to the role of T in gender development. As noted, we control for parent education and youth pubertal development in these analyses.

The Development of Expressivity

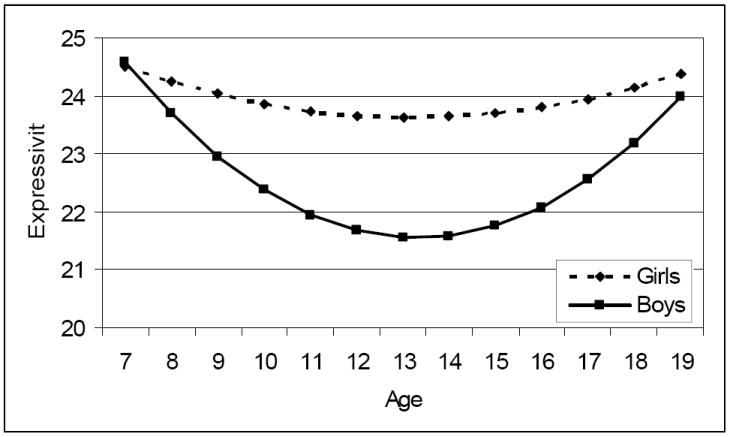

The best fitting growth curve model included random linear and fixed quadratic terms, γlinear = -.036, SE = .033, t = -1.07, NS and γquadratic = .048, SE = .010, t = 5.04, p < .001, respectively. The first step in the analyses revealed a significant sex difference at the intercept, indicating that girls reported more expressive qualities than boys at age 13, γgender = - 1.040, SE = .146, t = -7.12, p < .001. A significant sex by quadratic term interaction, γinteraction = .027, SE = .010, t = 2.78, p < .01, in combination with follow-up tests, revealed further, that girls showed no significant change over time, but that the quadratic pattern for boys was positive and significant, γboys = .076, SE = .014, t = 5.41, p < .001. As Figure 1 shows, boys declined in qualities like sensitivity and kindness from middle childhood through early adolescence but then increased until about age 19. Consistent with the gender intensification hypothesis were the decline in boys’ feminine qualities in early adolescence and a significant sex difference at age 13.

Figure 1.

Growth Curves for Expressivity

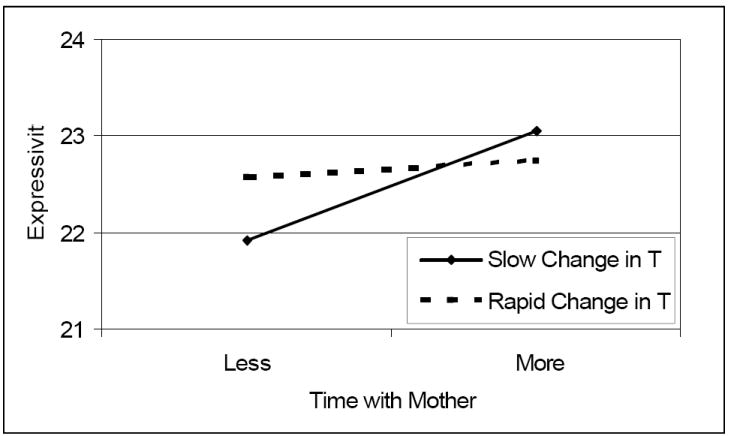

Next we tested whether the development of expressivity was linked to youth’s time in gendered social contexts. These analyses revealed only one significant effect: The cross-time average of youth’s time with mother was positively related to youth expressivity, γmother = .001, SE = .001, t = 2.17, p < .05. In other words, youth who spent more time with their mothers, on average, reported higher levels of expressivity, on average. There were no main effects for T level or rate of change, but, as Figure 2 shows, the predicted interaction between changes in T and maternal time was significant: Time with mother was positively related to expressivity, but only for youth who showed slower rates of increase in T, γinteraction = -.003, SE = .001, t = -1.94, p < .05. Among control variables, pubertal development at age 13 was positively and significantly linked to expressivity, γlevel = .236, SE = .439, t = 2.18, p < .01, but parent education was not.

Figure 2.

Interaction Between Time with Mother and Expressivity by Rate of Change in Testosterone

The Development of Instrumentality

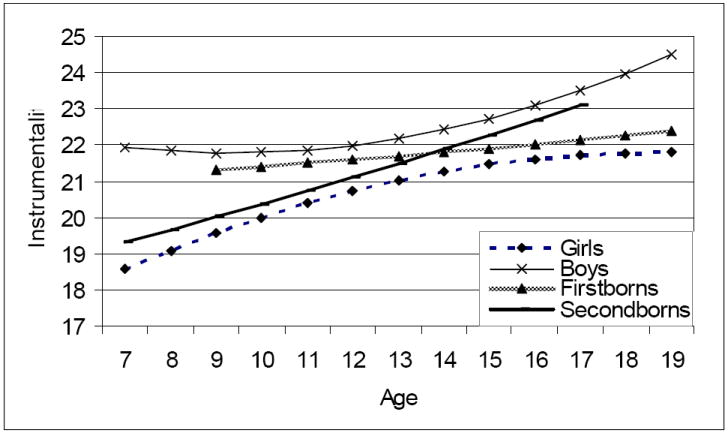

We used the same approach to study the development of stereotypically masculine qualities such as leadership and independence. The best fitting growth curve model included random linear, γlinear = .246, SE = .033, t = 7.37, p < .001, and fixed quadratic terms, γquadratic = - .028, SE = .009, t = -2.94, p < .01. The analyses revealed a significant sex difference at the intercept, indicating that boys reported more instrumental qualities at age 13, γgender = .580, SE = .162, t = 3.59, p < .001 (see Figure 3). There also were significant sex by quadratic age term and birth order by linear age term interactions, γsex interaction = .026, SE = .009, t = 2.77, p < .01, γbirth interaction = .140, SE = .048, t = 2.89, p < .01. Follow-up tests revealed that quadratic pattern for boys was positive at trend level, γboy quadratic = .029, SE = .017, t = 1.870 p <.10, and the linear effect was positive and significant, γboy linear = .215, SE = .059, t = 3.63, p < .001, indicating that boys’ instrumentality increased over time. For girls, the quadratic effect was not significant but the linear effect was positive and significant, γgirl linear = .270, SE = .058, t = 4.64, p < .001: Like boys, girls showed increases in instrumentality over time. Finally, follow-ups for the birth order interaction indicated that secondborns, γsecondborn linear = .382, SE = .067, t = 5.72, p < .001, but not firstborns, showed significant linear increases in instrumentality.

Figure 3.

Growth Curves for Instrumentality

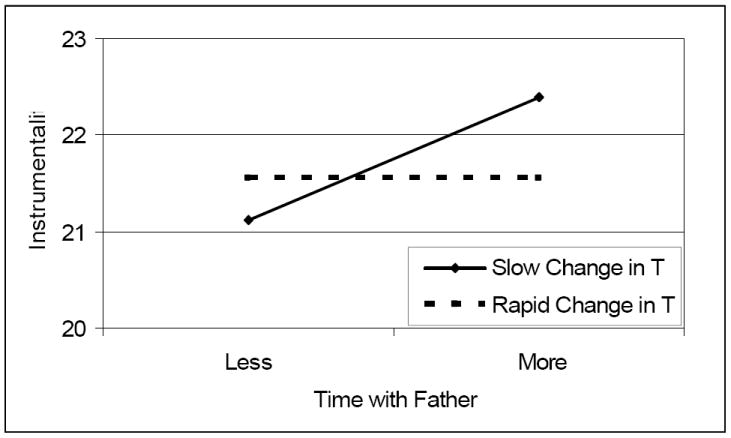

The second step in the analyses revealed two significant predictors of change in instrumentality: For both girls and boys, the cross-time averages of time with male peers and time with female peers were both linked to higher levels of instrumentality, γmale peers = .003, SE = .001, t = 4.56, p < .001 and γfemale peers = .003, SE = .001, t = 4.64, p < .001, respectively. In other words, youth who spent more time with male peers or with female peers, on average, reported higher levels of instrumentality, on average. As with the findings for expressivity, the results revealed no main effects for T level or rate of change, but there was a significant interaction between rate of change in T and youth time with fathers, γinteraction = -.004, SE = .002, t = -2.13, p < .05: Consistent with our prediction, the link between socialization experiences, i.e., time with father, and instrumentality was stronger for youth who showed slower rates of increase in T (see Figure 4). Among control variables, parental education was positively related to instrumentality.

Figure 4.

Interaction Between Time with Father and Instrumentality by Rate of Change in Testosterone

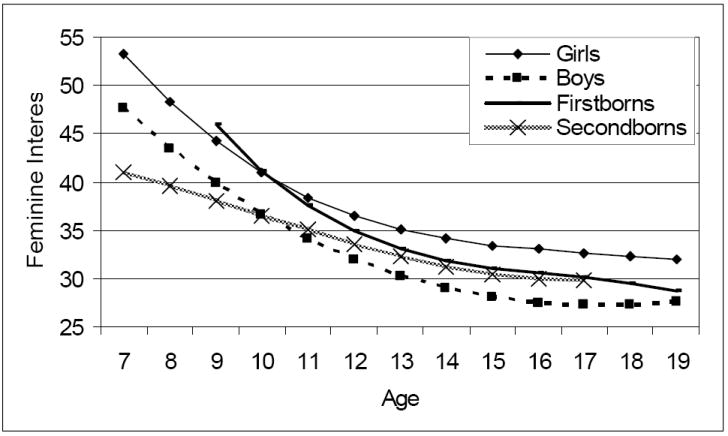

The Development of Feminine Activity Interests

Base-line null model tests revealed no estimable variance at the family level (Level 3). Thus, instead of 3-level models, we report results of 2-level models for the development of feminine interests. The overall growth curve included random linear, fixed quadratic, and fixed cubic terms indicating that feminine interests declined across time for the sample as a whole, γlinear = -1.358, SE = .079, t = -17.12, p < .001, γquadratic = .072, SE = .013, t = 5.48, p < .001 and γcubic = .090, SE = .004, t = 2.36, p < .05, respectively (see Figure 5). This analysis also revealed a significant sex difference, γgender = -2.431, SE = .247, t = -9.83, p < .001, indicating that girls reported more feminine interests at age 13. There was also a significant sex by age linear term interaction, γinteraction = -.305, SE = .158, t = -1.93, p < .05. Follow-up tests showed that the linear terms were significant for both girls and boys, though the effect for boys was stronger, suggesting that boys’ decline was steeper than girls’, γboys = -1.485, SE = .117, t = -12.65, p < .001, and γgirls = -1.180, SE = .113, t = -10.48, p < .05, respectively. This analysis also revealed a significant quadratic by birth order effect, γinteraction = -.105, SE = .035, t = -2.97, p < .01, and a significant cubic by birth order effect, γinteraction = .021, SE = .008, t = 2.54, p < .01. Follow-up tests revealed that the quadratic effects were significant for both firstborns and secondborns, though stronger for firstborns, γfirstborn = .312, SE = .054, t = 5.73, p < .001, γsecondborn = .102, SE = .045, t = 2.26, p < .05, respectively, and that the cubic effect was significant for firstborns, γfirstborn = -.032, SE = .014, t = -2.29, p < .05, but not secondborns. To clarify this pattern, as a follow-up step, we re-ran this analysis, setting the intercept at age 10. Although there was no birth order difference at age 13, at age 10 firstborns reported stronger feminine interests than secondborns, γbirth order = -4.60, SE = .744, t = -6.19, p < .001. Taken together these findings suggest that youth’s interests decline over time, somewhat more sharply for boys and firstborns as compared to girls and secondborns, but that the declines level off in middle adolescence; for firstborns however, there is an additional directional change in later adolescence (the cubic effect) when feminine interests once again decline.

Figure 5.

Growth Curves for Feminine Activity Interests

The second step in the analyses revealed three significant effects: Changes in feminine interests were positively related to changes in time with mother, γmother = .001, SE = .0005, t = 2.81, p < .01, and changes in time with father, γfather = .001, SE = .0005, t = 2.69, p < .01, but negatively related to changes in time with female peers, γfemale = -.001, SE = .0004, t = -2.10, p < .05. In other words, decreases in time with mother and father were linked to decreases in feminine interests, but increases in time with female peers were linked to decreases in feminine interests. No effects of T were significant. Among control variables, there was a significant positive effect for pubertal development at age 13, γpuberty = 2.479, SE = .738, t = 3.36, p < .001.

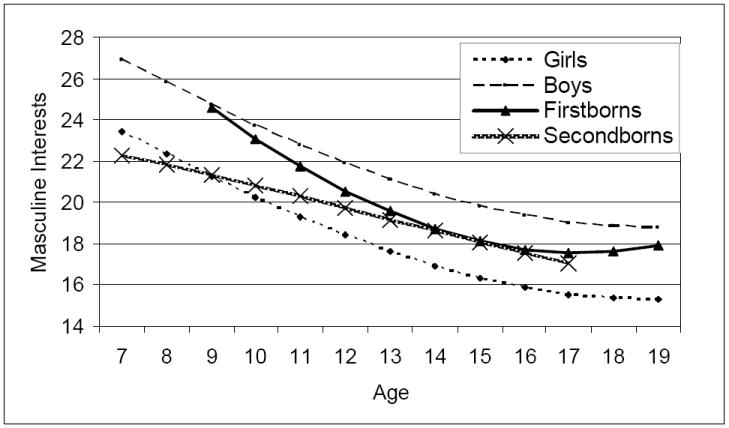

The Development of Masculine Activity Interests

The overall growth curve for masculine activity included random linear, fixed quadratic, and fixed cubic terms, γlinear = -.732, SE = .052, t = -13.98, p < .001, γquadratic = .017, SE = .009, t = 1.80, NS and γcubic = .009, SE = .003, t = 3.42, p < .001, respectively (see Figure 6). This analysis revealed an overall sex difference, γgender = 1.740, SE = .120, t = 14.46, p < .001, with boys reporting more masculine interests than girls at age 13. There also were significant interactions between birth order and both the linear, γlinear interaction = .175, SE = .054, t = 3.24, p < .01, and the quadratic age terms, γquadratic interaction = -.047, SE = .021, t = -2.426, p < .05. As was the case for feminine interests, follow-up tests revealed that the patterns of change for secondborns were muted relative to those of firstborns: The linear effect was significant for both first and secondborns, though stronger for firstborns, γfirstborn = -.913, SE = .085, t = -10.70, p < .001, than secondborns γsecondborn = -.562, SE = .067, t = -8.42, p < .001, and the quadratic effect was significant for firstborns, γfirstborn = .095, SE = .030, t = 3.16, p < .001, but not secondborns. To clarify these results we re-ran the analyses, setting the intercept at age 10: Although there was not a birth order difference at age 13, firstborns reported stronger masculine interests at age 10, γbirth order = -2.26, SE = .421, t = -5.38, p < .001. Taken together these findings suggest that firstborns’ interests start at a higher level and decline more steeply than secondborns. Firstborns’ decline levels off, however, by late adolescence (a time at which we do not have data for secondborns).

Figure 6.

Growth Curves for Masculine Activity Interests

In the next step, one significant effect of youth’s time use emerged: Changes in time with father were positively related to changes in masculine interests, γfather = .001, SE = .0003, t = 2.91, p < .01: As time with father decreased or increased, so too did masculine interests. No significant effects of T emerged in these analyses. Nor were any of the controls variables significant.

Exploratory Analysis of Gender Neutral Interests

Given the findings for feminine and masculine interests, we conducted an additional analysis, using the same analytic approach but focused on gender-neutral interests (e.g., ride bike) to determine whether or not declines in interests were limited to gendered activities. The results showed the same pattern of decline over time in gender-neutral activities (results available from the first author).

Discussion

We expanded on prior cross-sectional and short term longitudinal studies to chart the course of gender development in the domains of sex stereotypical personality qualities and interests from middle childhood through adolescence. In addition, we studied both social and biological factors that might explain individual differences in youth’s developmental patterns. Our results yielded a four-part take home message. First, findings were consistent with analyses that highlight the multi-dimensional nature of gender: Different dimensions of gender showed distinct developmental patterns and had distinct correlates. Such results underscore the importance of careful definition and operationalization of gender in future research (Ruble et al., 2006). Second, consistent with an ecological perspective on the role of daily activities in development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), the analyses revealed links between the gendered social contexts of youth’s time use and their gender development. Most results were consistent with the hypothesis, grounded in social learning and gender schema theories, that time with females would be linked to stereotypically feminine development, and time with males, with stereotypically masculine development. Third, our study expanded on prior work to examine the potential role of T in gender development in middle childhood and adolescence. The analyses revealed two parallel moderation effects and were consistent with the hypothesis that more rapid increases in T levels set constraints on socialization influences (Buchanan et al., 1993). Our work also expanded on prior research to document this effect in both girls and boys. Fourth, our within-family comparisons of firstborns’ versus secondborns’ gender development revealed sibling differences on three of the four gender development measures. Most child development research is grounded in an implicit assumption that developmental patterns will be similar for all children in a family, but our findings highlight the significance of children’s position in the sibling constellation. Below, we elaborate on these conclusions, and taking into account the limitations of this study, highlight the implications of our findings for understanding gender development.

The Development of Gendered Personality Qualities and Interests

Our analyses of the development of gendered personality traits revealed different patterns for expressive versus instrumental qualities. For girls, the findings revealed no changes over time in expressivity, but significant linear increases in instrumentality. The pattern for girls’ instrumentality is consistent with the idea from gender schema theory that gender role orientations become increasingly flexible across middle childhood. In contrast, the gender intensification hypothesis holds that children will become more stereotypical in early adolescence, and the observed declines in boys’ expressivity were consistent with this pattern. Boys’ instrumentality was relatively stable in middle childhood and early adolescence, but increased in mid to late adolescence. Our data only allowed us to chart the development of personality qualities until age 19, but the observed patterns suggest that much more could be learned about gender and personality by following youth into adulthood.

These findings differ from results of an earlier, two-year study of sex-typed personality characteristics in which sex differences in instrumentality but not expressivity increased between ages 11 and 13 (Galambos, et al., 1990). In addition to a different design and analytic approach, the data for that study were collected about a decade earlier than ours, and more recent efforts to promote achievement and self confidence in young adolescent girls may be responsible for the observed increases in girls’ instrumentality in early adolescence. With respect to expressivity, Galambos et al. (1990) found no changes in sex differences in early adolescence. Our data, however, suggest that discerning the nature of sex differences in expressivity requires studying youth over a longer span of time. Boys’ “recovery” of (or willingness to admit to) qualities such as sensitivity and kindness in later adolescence underscores the importance of studying gender development into adulthood.

Importantly, birth order effects qualified our conclusions about the development of stereotypically masculine personality qualities: Although the linear coefficients for both were positive, secondborns, but not firstborns, showed significant increases in instrumentality over time. Within the field of social psychology, there is a large literature that has sought to identify birth order differences in personality qualities. Findings are not consistent, but have highlighted the authority-orientation of firstborns (e.g., toward achievement, but also toward conformity). In contrast, Sulloway (1996) describes laterborns as “born to rebel” given that their needs and interests are not well-served by a status quo that proscribes power and privilege for firstborns. Secondborns’ development of the “adventurous,” “brave,” and “independent” qualities that comprise instrumentality may be consistent with Sulloway’s conceptualization. Importantly, prior work has not focused on the development of personality characteristics. Our findings of no birth order differences at age 13 coupled with differences in patterns of change suggest that birth order differences in personality are best studied in a developmental framework. For gender development researchers, an important point is that characteristics marked as stereotypical within a gender frame may have a different valence within another frame (e.g., that independence and adventurousness mark “rebellion”), and thus that gender development may be better understood within a larger framework of socialization influences. These birth order differences require replication, but again, they call into question the assumption that studying one child in a family is sufficient for understanding how family socialization processes work.

Turning to the development of gendered interests, our results were consistent with Jacobs et al.’s (2002) findings of linear declines in subjective values for a range of gendered activities. In the face of significant overall sex differences, both the girls and boys in our sample showed the same pattern of cross-time declines in interest in stereotypically feminine and masculine interests (and in an exploratory step, in gender- neutral interests, as well). These findings are consistent with Jacobs et al.’s conclusions that youth’s subjective evaluations of activities are grounded in an increasingly specialized focus, as ability levels, opportunities, and resources motivate youth to make choices about the interests and activities they will pursue. They also are consistent with the idea that hanging out and socializing with peers replaces involvement in constructive activities in adolescence (Larson & Verma, 1999).

Birth order also played a role in patterns of change in gendered interests. In part these differences were due to the fact that we studied firstborns until age 19, when additional directional changes in developmental patterns became evident (e.g., the significant cubic effect for firstborns’ feminine interests); the findings for firstborns underscore the importance of studying gender development into adulthood. The more pronounced change patterns for firstborns also can be attributed, however, to their higher levels of interest in both masculine and feminine activities in middle childhood: We found birth order differences in interests favoring firstborns at age 10 but differences at age 13 were not significant. As a period of “industry” (Erikson, 1959), middle childhood is a time when children explore a range of activities (Lareau, 2003). Although parents may have the time and resources to encourage their first child’s awakening interests in a broad range of activities, limits to social and economic capital, and what they learn from experiences with their first child may mean that parents encourage specialization more quickly in laterborns. Secondborns may collaborate in this process, following their older sisters’ and brothers’ example and specializing in their interests at a younger age. Most research on the role of the family in gender socialization has examined family member influences in isolation, focusing, for example, on mother-child communication or father-child play patterns. A family systems perspective, in contrast, highlights direct and indirect influences across multiple subsystems in the family and reminds us that family influences are likely to be complex and multifaceted (Whitechurch & Constantine, 1992).

Individual Differences in the Development of Gendered Personality Qualities and Interests

In addition to the sex and birth order differences we have discussed, our analyses also were directed at social and biological factors that explained individual differences in the development of gendered personality qualities and interests. Most of our findings were consistent with a gender socialization hypothesis, that time with females would be linked to the development of stereotypically feminine qualities and that time with males would be linked to the development of stereotypically masculine qualities. Our results also showed that social factors were more consistently linked to gender development than were the measures of biological influences, i.e., age 13 level and rate of change in T.

Consistent with the ecological emphasis on the role of daily activities in development, we found that youth’s time spent with mothers was a significant correlate of stereotypically feminine traits and interests: The cross time average of time with mother was linked to the cross-time average of expressivity for youth with slower rates of change in T, and time with mother was a significant time-varying correlate of feminine interests meaning that as time with mother increased or decreased, so too did feminine interests. These findings did not emerge in our prior short term study, but the longitudinal scope and analytic approach we used here provided a more powerful lens through which to discern these associations. Importantly, the correlational design of this study means that we can not draw inferences about direction of effect: Time with mother may be linked to feminine qualities and interests because mothers model and reinforce these qualities as a social learning perspective holds; consistent with a gender schema perspective, it also is possible that offspring who see themselves as having feminine qualities and interests choose to spend more time with their mothers. An advantage to the analytic approach we used is that, in the case of the time-covarying relations between youth’s interests and maternal time, we can rule out stable third variables (e.g., family demographics, stable parental attitudes) as explanations for observed linkages. A direction for future research will be the use of cross-lagged designs to illuminate temporal precedence in the links between youth’s gendered qualities and time use.

The findings for masculine traits and interests also underscored the importance of daily activities. The results were consistent with both social learning and gender schema ideas in that time with father was a significant time-varying covariate of masculine interests and time with male peers was linked to instrumentality; time with father also was also positively related to instrumentality, but only for youth who exhibited slower rates of increase in T. These linkages did not emerge in our prior study, but our longitudinal scope and analytic approach enhanced our ability to detect these effects.

Three findings were inconsistent with a gender socialization hypothesis. First, similarly to time with male peers, the results indicated that time with female peers was positively related to instrumentality. These results also are a reminder that qualities defined as gendered have valence in other domain: The agentic traits that comprise instrumentality have been linked to positive youth adjustment (Crick & Zahn-Waxler, 2003; Hoffman et al., 2004). As such, our findings may mean that girls and boys who are better adjusted and get along better with their peers (whether male or female) have more instrumental traits. Two other inconsistent findings emerged for feminine interests: similarly to time with mother, changes in time with father were positively related to changes in feminine interests, and time with female peers was negatively related to feminine interests. As noted, normative declines in activity interests across adolescence may reflect an increasing interest in hanging out and socializing with peers. In contrast, many of the feminine activity interests that we studied involve solitary and even intellectual pursuits (e.g., reading, the arts, playing musical instruments) that may be supported by parental involvement. Thus, when youth spend more time with peers, they may be less interested in feminine activities. Also, it is possible that youth who have stronger feminine interests spend less time with peers and more time with parents.

Turning to the role of T, we found no main effects for circulating T levels or rates of increase, but two parallel interaction effects reached significance: Time with mother was positively linked to expressive qualities and time with father was positively related to instrumental qualities, but only for youth who showed slower rates of increase in T. These patterns are consistent with the idea that more rapid rises in T set constraints on the operation of socialization influences (Buchanan et al., 1992). Given that only two of 16 interactions reached significance, these findings should be viewed cautiously. On the other hand, these effects were predicted, and as Raine (2002) argued, the difficulty of documenting bio-social interactions means that Type II error is higher than in other kinds of research. In combination with our prior findings, the results suggest that the role of T in adolescent gender development may merit further study.

Conclusions

The overarching purpose of this study was to illuminate processes of gender development from middle childhood through adolescence. Our study’s focus on specific domains of gender, longitudinal scope and within-family design, detailed information on youth’s daily activities, and biomarker data allowed for new insights into gender development patterns and their correlates. Our focus on a local and relatively homogeneous sample limited sources of between-family variance and sample attrition, but also means that our results are not generalizable to youth from families of different structures or ethnicities. Given the social construction of gender, studying the implications of cultural factors in gender development is an important direction for research. Finally, the trajectories of gender development that we uncovered direct attention to early adulthood as a time of continued change in gendered interests and personality. Gender is central in human development across the lifespan, and patterns of change and their correlates require continued investigation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Matt Bumpus, Kelly Davis, Doug Granger, Heather Helms, Julia Jackson-Newsom, Marni Kan, Wayne Osgood, Lilly Shanahan, Cindy Shearer, Kimberly Updegraff, Shawn Whiteman, and Megan Winchell for their help in conducting this study and the participating families for their time and insights about their family lives. This work was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, RO1-HD32336, Ann C. Crouter and Susan M. McHale, Co-Principal Investigators.

Contributor Information

Susan M. McHale, The Pennsylvania State University

Ji-Yeon Kim, University of Hawaii at Manoa.

Aryn M. Dotterer, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Ann C. Crouter, The Pennsylvania State University

Alan Booth, The Pennsylvania State University.

References

- Aiken L, West S. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Antill J, Russell G, Goodnow J, Cotton S. Measures of children’s sex-typing in middle childhood. Australian Journal of Psychology. 1993;45:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Berenbaum SA, Hines M. Early androgens are related to childhood sex-typed toy preferences. Psychological Science. 1992;3:203–206. [Google Scholar]

- Booth A, Mazur A, Dabbs J. Endogenous testosterone and competition: The effects of fasting. Steroids. 1993;58:348–350. doi: 10.1016/0039-128x(93)90036-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brim O. Family structure and sex role learning by children: A further analysis of Helen Koch’s data. Sociometry. 1958;21:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan CM, Eccles JS, Becker JB. Are adolescents the victims of raging hormones? Evidence for activational effects of hormones on moods and behavior in adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:62–107. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Sharp EH, Palen L, Darling N, Cumsille P, Marta E. Exploring adolescent self-defining activities and identity experiences across three countries. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2005;29:361–370. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Zahn-Waxler C. The development of psychopathology in Females and males: current progress and future challenges. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:719–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouter A, Manke B, McHale S. The family context of gender intensification in early adolescence. Child Development. 1995;66:317–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, Whiteman SD, McHale SM, Osgood WD. The development of gender attitude traditionality across middle childhood and adolescence. Child Development. 2007;78:911–926. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelbrock C, Sugawara A. Acquisition of sex-typed preferences in preschool-aged children. Developmental Psychology. 1978;14:614–623. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Childhood and society. New York: Norton; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Galambos N, Almeida D, Petersen A. Masculinity, femininity and sex role attitudes in early adolescence: Exploring gender intensification. Child Development. 1990;61:1905–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger DA, Schwartz EB, Booth A, Arentz M. Salivary testosterone determination in studies of child health and development. Hormones and Behavior. 1999;36:18–27. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1998.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JP, Lynch ME. The intensification of gender-related role expectations during early adolescence. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Petersen A, editors. Girls at puberty: Biological and psychosocial perspectives. New York: Plenum; 1983. pp. 201–228. [Google Scholar]

- Hines M, Golombok S, Rust J, Johnston K, Golding J the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children Study Team. Testosterone during pregnancy and gender role behavior of preschool children: A longitudinal population study. Child Development. 2002;73:1678–1687. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman ML, Powlishta KK, White KJ. An examination of gender differences in adolescent adjustment: The effect of competence on gender role differences in symptoms of psychopathology. Sex Roles. 2004;50:795–810. [Google Scholar]

- Huston A. The development of sex-typing: Themes from recent research. Developmental Review. 1985;5:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Huston TL, McHale SM, Crouter AC. Changes in the marital relationship during the first year of marriage. In: Gilmour R, Duck S, editors. The emerging field of personal relationships. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1985. pp. 109–132. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JE, Lanza S, Osgood DW, Eccles JS, Wigfield A. Changes in children’s self competence and values: Gender and domain differences across grades one through twelve. Child Development. 2002;73:509–527. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JY, McHale SM, Crouter AC, Osgood DW. Longitudinal linkages between sibling relationships and adjustment in middle childhood and adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:960–973. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreft IGG, Leeuw J, Aiken LS. The effect of different forms of centering in hierarchical linear models. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1995;30:1–21. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3001_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Verma S. How children and adolescents spend time across the world: Work, play and developmental opportunities. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;126:701–736. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lareau A. Unequal childhoods: Class, race, and family life. University of California Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Leaper C. Exploring the consequences of gender segregation on social relationships. In: Leaper C, editor. New Directions for child development The development of gender relationships. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Leaper C. Parenting girls and boys. In: Bornstein M, editor. Handbook of parenting. Vol. 1. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 189–225. [Google Scholar]

- Liben LS, Bigler RS. The developmental course of gender differentiation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2002;67(2) Serial No 269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. The two sexes: Growing apart and coming together. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Martin CL, Fabes RA. The stability and consequences of young children’s same-sex peer interactions. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37(3):431–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Crouter AC, Whiteman SD. The family contexts of gender development in childhood and adolescence. Social Development. 2003;12:125–148. [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Kim JY, Whiteman SD, Crouter AC. Links between sex-typed activities in middle childhood and gender development in early adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:868–881. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.5.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Shanahan L, Updegraff KA, Crouter AC, Booth A. Developmental and individual differences in girls’ sex-typed activities from middle childhood through middle adolescence. Child Development. 2004;75:1575–1593. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medrich EA, Roizen JA, Rubin V, Buckley S. The serious business of growing up: A study of children’s lives outside school. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Montemayor R, Brownlee Fathers, mothers, and adolescents: Gender based differences in parental roles during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1987;16:281–291. doi: 10.1007/BF02139095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen A, Crockett L, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1988;17:117 – 133. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models. 2. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Richards MH, Crowe PA, Larson R, Swarr A. Developmental patterns and gender differences in the experience of peer companionship during adolescence. Child Development. 1999;69:154–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruble DN, Martin CL, Berenbaum SA. Gender development. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology, vol 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 6. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. pp. 858–932. [Google Scholar]

- Serbin LA, Powlishta KK, Gulko J. The development of sex-typing in middle childhood. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1993;52(2) Serial No. 232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan L, McHale SM, Crouter AC, Osgood DW. Warmth with mothers and fathers from middle childhood through adolescence: Within and between family comparisons. Developmental. Psychology. 2007;43:551–563. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulloway FJ. Born to rebel: Birth order, family dynamics, and creative lives. New York: Pantheon Books; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Udry JR. Biological limits of gender construction. American Sociological Review. 2000;65:443–457. [Google Scholar]

- Whitchurch GG, Constantine LL. Systems theory. In: Boss PG, Doherty WJ, LaRossa R, Schumm WR, Steinmetz SK, editors. Sourcebook of family theories and methods: A contextual approach. New York: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 325–352. [Google Scholar]