Abstract

Since the original descriptions of gain-of function mutations in anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), interest in the role of this receptor tyrosine kinase in neuroblastoma development and as a potential therapeutic target has escalated. As a group, the activating point mutations in full-length ALK, found in approximately 8% of all neuroblastoma tumors, are distributed evenly across different clinical stages. However, the most frequent somatic mutation, F1174L, is associated with amplification of the MYCN oncogene. This combination of features appears to confer a worse prognosis than MYCN amplification alone, suggesting a cooperative effect on neuroblastoma formation by these two proteins. Indeed, F1174L has shown more potent transforming activity in vivo than the second most common activating mutation, R1275Q, and is responsible for innate and acquired resistance to crizotinib, a clinically relevant ALK inhibitor that will soon be commercially available. These advances cast ALK as a bona fide oncoprotein in neuroblastoma and emphasize the need to understand ALK-mediated signaling in this tumor. This review addresses many of the current issues surrounding the role of ALK in normal development and neuroblastoma pathogenesis, and discusses the prospects for clinically effective targeted treatments based on ALK inhibition.

Keywords: neuroblastoma, ALK, tyrosine kinase receptor, targeted therapy, crizotinib, drug resistance, point mutations, small molecule inhibitors, combination treatment

1. Introduction

Identification of the anaplastic lymphoma kinase, ALK, as a therapeutic target in primary neuroblastoma represents a major research advance in this childhood cancer. The original discovery of ALK in 1994 resulted directly from investigations into the frequently observed t(2;5)(p23;q35) chromosomal rearrangement in anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), which fuses the cytoplasmic domain of ALK to the N-terminal portion of the nucleolar phosphoprotein, NPM [1]. Many other examples of aberrant ALK activation due to chromosomal rearrangement have been described in human cancers, including non-small-cell lung carcinomas (NSCLC), inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors (IMTs), diffuse large cell B-cell lymphomas and esophageal squamous cell carcinomas [2]. More recently, activating mutations of ALK were discovered in both familial and sporadic cases of neuroblastoma, an often fatal tumor that arises from neural crest cells of the noradrenergic lineage [3-6]. These findings are important because mutations in this receptor tyrosine kinase have displayed transforming potential in vivo [3] and their knockdown in neuroblastoma cells inhibits proliferation [3-6]. Thus, continued study of wild-type and mutated ALK holds considerable promise for deciphering the signaling networks that underlie neuroblastoma pathogenesis and for developing effective targeted therapies.

2. The ALK receptor tyrosine kinase

2.1. Structure

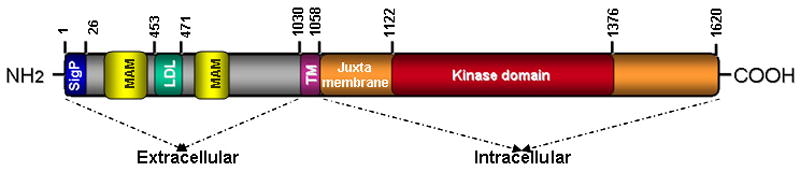

ALK has been classified as a member of the insulin receptor (IR) superfamily of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) due to its high homology with other members of this family, such as the leukocyte tyrosine kinase (LTK), the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor kinase (IGF1RK) and the insulin receptor kinase (IRK) [7]. ALK is located in humans at chromosome 2p23 and on the distal end of mouse chromosome 17 [8]. It is a single-chain 1620 amino acid (aa) transmembrane protein consisting of a 1030-aa extracellular domain, a 28-aa transmembrane-spanning domain and a 276-aa intracellular tyrosine kinase domain [9] (Fig.1). The 177-kDa polypeptide encoded by the human ALK gene undergoes post-translational modifications, such as N-glycosylation, to generate a mature protein doublet of 220 and 190 kDa [10-12]. ALK migrates as two protein isoforms: the 220-kDa full-length receptor and the truncated 140 kDa protein that results from extracellular cleavage [13]. The functional relevance of this phenomenon is not clear, although the cleavage can be inhibited by an as yet unidentified factor secreted by Schwann cells [13]

Figure 1. Domain structure of ALK.

The N-terminal, extracellular region of human ALK contains a signal peptide (aa 1-26), two MAM domains (aa 264-427 and 480-626), one LDL domain (aa 453-471) and a glycine-rich domain (aa 816–940). The transmembrane domain (TM) (aa 1030-1058) connects the extracellular and intracellular domains. The intracellular (cytoplasmic) domain contains the juxtamembrane (1058-1122) and the tyrosine kinase catalytic domains (aa 1122-1376).(SigP, signal peptide; TM, transmembrane) , not drawn to scale.

The extracellular region of ALK comprises a 26-aa N-terminal signal peptide sequence, two MAM (meprin, A-5 protein, receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase mu) domains (aa 264-427 and 480-626) that are thought to have adhesive functions, one LDLa domain that forms a binding site for LDL and calcium, and a glycine-rich region [9, 14]. This extracellular segment also contains the binding site for ligand binding [15-17] between aa 391 and 401 [2, 15]. Both the extra- and intracellular domains are connected by a 28 aa transmembrane domain, which is followed by a 64-aa juxtamembrane domain. The tyrosine kinase catalytic domain (aa 1122-1376) contains a three-tyrosine kinase motif YXXXYY represented by Tyr1278, Tyr1282 and Tyr1283 within its activation loop (A-loop); these are major sites common to kinases in the insulin receptor family whose phosphorylation regulates kinase catalytic activity. Ligand binding leads to receptor dimerization and activation via trans-autophosphorylation of these tyrosine residues [7]. In addition, other phosphorylation sites have been described in the juxtamembrane domain (aa 1093-1096) and within the cytoplasmic domain (aa 1504-1507) that serve as binding sites for IR substrate-1 and Src homology 2 domain containing (SHC) proteins involved in downstream signaling [7].

2.2. Activation of ALK

Because of the high overall sequence identity within the A-loop regions of ALK and IGF1RK/IRK, it was thought that they shared common regulatory and activation mechanisms. IGF1RK/IRK maintain their inactive states by a number of autoinhibitory mechanisms including positioning the unphosphorylated A-loop so that it prevents the access of ATP and protein substrates to the ATP-binding pocket [18, 19]. Kinase activation is regulated by the sequential phosphorylation of three major autophosphorylation sites, with the second tyrosine preferentially phosphorylated first, followed by the first tyrosine residue and lastly the third residue. In its inactive form, the A-loop occludes the ATP-binding pocket through the proximal A-loop DFG (Asp-Phe-Gly) motif (‘DFG-out” conformation) and through pseudo-substrate binding of the second A-loop tyrosine residue to the phosphoacceptor site. When these negative regulatory restraints are overcome, the A-loop undergoes a conformational change and swings outward and away from the ATP-binding pocket, allowing unimpeded access of ATP (‘DFG-in’) and peptide substrate, leading to activation. However the autoinhibitory mechanisms in ALK appear to be different from those of IGF1RK/IRK, with ALK lacking many of the negative regulatory features of the inactive IGF1RK/IRK molecule. Firstly, preferential phosphorylation of the first tyrosine residue, Tyr 1278, occurs in ALK, this residue being critical for autoactivation of the ALK kinase domain and transforming activity [20]. In fact, ALK has minimal requirement for phosphorylation of the second and third tyrosine residues [21, 22]. Secondly, ALK possesses narrower peptide substrate specificity when compared with the IGF1RK/IRK. These differences between ALK and IGF1RK/IRK were explained by two independent groups who recently reported the x-ray crystal structure of the ALK catalytic domain in its inactive conformation [21] [22]. The A-loop of ALK has a unique autoinhibitory conformation in which a short helix at the proximal A-loop restricts the mobility of the N-terminal lobe, while the distal A-loop sterically obstructs a portion of the predicted peptide-binding region. This autoinhibitory mechanism of ALK that relies on intramolecular interactions between the N-terminal β-sheet and the DFG helix prevents binding of the peptide substrate and sequesters the first tyrosine residue, Tyr 1278, so that it is inaccessible for phosphorylation [22]. A single amino acid difference in the phosphoacceptor site as well as A-loop sequence differences account for the different sequence of tyrosine phosphorylation and the unique peptide substrate specificity seen in ALK compared to the IRKs [21]. Altogether, it appears that autoinhibition of the ALK tyrosine kinase domain is achieved by mechanisms similar to that used by EGFR rather than members of the insulin receptor family.

2.3. Normal expression

ALK is preferentially expressed in the central and peripheral nervous systems [7, 10]. In mice, in situ hybridization studies showed that ALK mRNA expression is restricted to regions in the developing brain and peripheral nervous system (thalamus, hypothalamus, midbrain, cranial ganglia, and olfactory bulb as well as the enteric nervous system and dorsal root ganglia) during embryogenesis. Levels of ALK mRNA decrease after gestation, and ALK protein levels decline postnatally, remaining at low levels in the adult animal [10, 23]. These findings are supported by immunohistochemical studies demonstrating consistently low levels of ALK in adult human CNS tissue samples [12], restricted to rare scattered neural cells, endothelial cells and pericytes in the brain [10, 12, 23].

2.4. Normal function

The normal function of the full-length ALK receptor is not entirely clear, although its predominant expression in the brain during development indicates that it likely plays an important role in the development and function of the nervous system [10, 13, 24]. Mice homozygous for a deletion of the ALK kinase domain develop normally, with no obvious anatomical abnormalities and a normal life-span [7]. However, these mice do exhibit increased basal dopaminergic signaling within the prefrontal cortex and an age-dependent increase in basal hippocampal progenitor proliferation, with concomitant enhanced performance in novel object recognition/location tests [25]. In Drosophila melanogaster, the receptor is vital for the development of visceral gut musculature, as the absence of dALK leads to loss of mesodermal founder cells responsible for gut development [26, 27].

2.5. Signaling by the wild-type ALK receptor

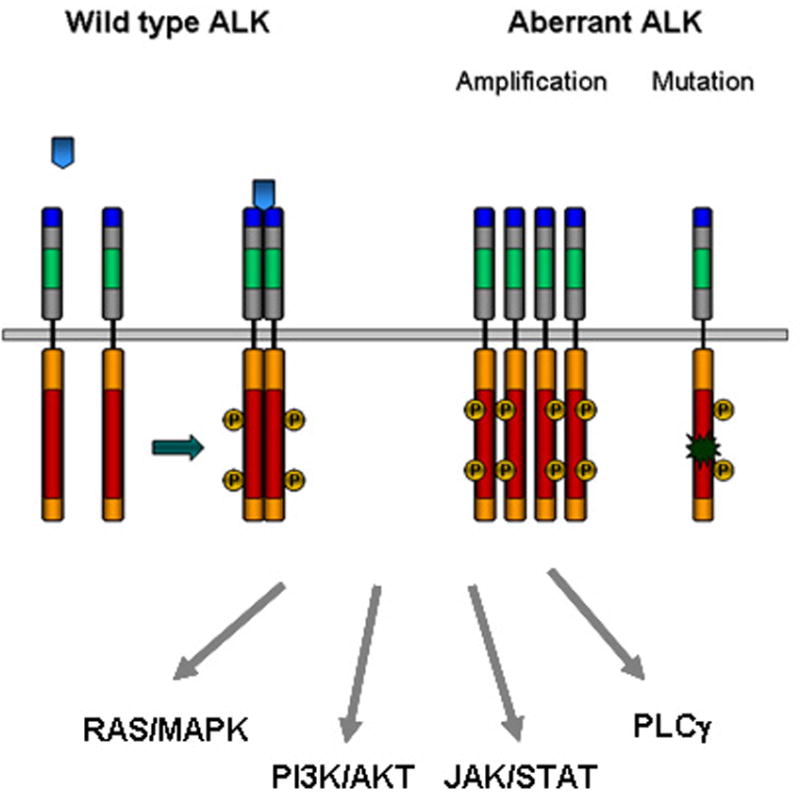

The candidate ligands of mammalian ALK reported thus far are pleiotropin (PTN) and midkine (MK) [15, 17]. These heparin-binding growth factors with roles in neural development are structurally related and their expression during embryonic development is similar to that of ALK, with high levels in the nervous system during gestation and decreased expression thereafter. Signaling by PTN and MK triggers dimerization and phosphorylation of ALK, leading to activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway and subsequent cell proliferation [16] (Fig. 2). Ligand activation of ALK has also been implicated in the inhibition of apoptosis [7] and induction of neuronal cell differentiation through the MAPK pathway [13, 28, 29]. Signaling through the PLCγ (phospholipase Cγ) pathway leading to transformation of NIH 3T3 cells has also been reported [30]. Additionally, PTN indirectly leads to tyrosine phosphorylation/activation of ALK by binding to and inactivating the receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase ζ 1 (RPTPβ/ζ) which normally serves to dephosphorylate ALK [31]. Whether PTN and MK are true ligands of ALK remain controversial, as some groups failed to reproduce the binding and activation of ALK by PTN [32] [33, 34] underscoring the need for further study of the roles of these potential ligands. In Drosophila, ALK signaling is activated upon binding of the Jeb (jelly belly) ligand, which is structurally different from either PTN or MK [27]. Binding of Jeb to dALK leads to activation of the MAPK pathway [35-37], but until mammalian counterparts of Jeb are identified, the relevance of this observation for higher organisms will remain uncertain.

Figure 2. Signaling by ALK.

ALK signaling can be activated by ligand binding (blue arrows), gene amplification or mutation. The receptor is then auto-phosphorylated, stimulating signal transduction through the indicated downstream pathways.

ALK is also thought to function as a dependence receptor, independent of activation status [38]. Caspase 3-mediated cleavage of ALK exposes a pro-apoptotic intracellular domain of ALK, resulting in increased apoptosis. Transient expression of wild-type ALK in rat-immortalized neuroblasts led to apoptotic cell death that was counteracted by antibodies binding to ALK. Thus, wild-type ALK exhibits proapoptotic activity in the absence of ligand and is anti-apoptotic when activated by ligand binding [38]. Given the broad diversity of biological processes associated with heparin-binding proteins [39], it is reasonable to predict that ALK ligands other than PTN/MK will be found. This issue has important implications for the role of ALK in neuroblastoma (see below), as dysregulation of any ALK ligand could affect tumor progression.

3. The role of ALK in neuroblastoma

During 2008, several groups reported the presence of activating ALK mutations in both familial [5, 6] and sporadic [3-6, 40] cases of neuroblastoma. These findings have catalyzed considerable efforts to understand the role of ALK-mediated signaling in neuroblastoma, as components of this pathway represent attractive candidate targets for inhibition of tumor progression.

3.1. ALK mutations

3.1.1. Germline mutation

Dominant mutations in ALK have been identified in approximately 50% of familial neuroblastoma [6]. Linkage analysis in families with affected members first identified a locus on chromosome 2p as being involved in hereditary neuroblastoma [41]. Further analysis identified a putative neuroblastoma gene-encoding chromosomal region at 2p23-p24. Within this large region, which also included MYCN, ALK was considered a strong candidate because of the coincident discovery of amplification and somatic mutations in primary tumors. Resequencing of ALK identified mutations in probands that segregated with disease in each family. Three distinct germline mutations have been described to date: R1275Q, R1192P and G1128A, with R1275Q being the most frequent [5, 6] (Table 1). The penetrance of the mutations is incomplete, as indicated by the variable development of neuroblastic tumors among ALK mutation carriers [5, 6].

Table 1.

ALK mutations identified in neuroblastoma

| Mutation | Tumor/cell line | Nucleotide substitution | ALK region | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1128A | T | 3383 G → C | P-loop | [6] |

| T1151M | T | 3452 C → T | Kinase domain | [4] |

| R1192P | T | 3575 G → C | β4 strand | [6] |

| R1275Q | T/C | 3824 G → A | Activation loop | [3-6, 40] |

| D1091N | T/C | 3271 G → A | Juxtamembrane domain | [4, 6] |

| M1166R | T | 3497 T → G | C helix | [6] |

| I1171N | T | 3512 T → A | C helix | [6] |

| F1174I | T | 3520 T → A | C helix | [6, 40] |

| F1174V | T/C | 3520 T → G | C helix | [3] |

| F1174C | T | 3521 T → G | C helix | [3] |

| F1174L | T/C | 3522 C→ A/G | C helix | [3, 4, 6, 40] |

| T1087I | T | 3620 C→ T | Juxtamembrane domain | [3] |

| A1234T | T | 3700 G→ A/G | Kinase domain | [4] |

| F1245V | T/C | 3733 T → G | Catalytic loop | [4, 6] |

| F1245I | T | 3733 T → A | Catalytic loop | [40] |

| F1245C | T | 3734 T → G | Catalytic loop | [4, 6] |

| F1245L | T | 3735 C→ A/G | Catalytic loop | [3, 40] |

| I1250T | T | 3749 T → C | Catalytic loop | [6] |

| R1275Q | T/C | 3824 G → A | Activation loop | [3-6, 40] |

| K1062M | T/C | 3185 A → T | Juxtamembrane domain | [3] |

| R1275L | T | 3824 G → T | Activation loop | [5] |

|

| ||||

| Y1278S | T | 3833 A → C | Kinase domain | [5] |

3.1.2. Somatic mutations

Somatic activating mutations have been identified in conserved positions in the tyrosine kinase domain in primary neuroblastoma tumors [3-6]. Altogether, 12 different residues are known to be affected by ALK mutations (Table 1) [42, 43]. The two major mutational hotspots are R1275 and F1174: the R1275Q mutation is found in both familial and sporadic neuroblastoma, while the F1174L mutation is restricted to sporadic tumors. Both types of mutations are associated with constitutive phosphorylation of ALK and that of downstream targets such as ERK, STAT3 and AKT [3-6]. These ALK variants are for the most part retained intracellularly in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi and exhibit impaired maturation with defective N-linked glycosylation [44]. Moreover, the constitutive activity of these variants does not require receptor dimerization [44]. Their oncogenic potential has been demonstrated by cytokine-independent growth [4, 43], transformation of NIH-3T3 fibroblasts in soft agar colony formation assays [3] and tumor formation in nude mice [3]. Knockdown of ALK in ALK-mutant neuroblastoma cell lines led to significant inhibition of cell proliferation and induction of cell death, further emphasizing the strong oncogenic “addiction” of these cells to mutationally activated ALK [3-6]. The third most frequent ALK mutation observed is at F1245, which is also activating in Ba/F3 cells (R. George, unpublished). All three mutations, F1174L, R1275Q and F1245C, are sensitive to inhibition by small molecule inhibitors of ALK, resulting in apoptosis and cell cycle arrest after treatment [4, 5, 7]. Subsequent studies have confirmed their oncogenic potential and suitability as therapeutic targets [40, 43].

Elucidation of the crystal structure of ALK in its inactive conformation, followed by mapping of neuroblastoma-associated mutations has yielded fresh insights into the mechanisms of aberrant ALK activation [21] [22]. In general, many of ALK residues that become mutated in neuroblastoma are thought to play structural roles in autoinhibition of ALK, which in its mutated form allows unrestricted mobility of the αC helix, phosphate-binding loop and N-terminal lobe leading to kinase activation. F1174L is located in the A-loop just distal to αC C-terminus, and the change of F1174 to Ile or Leu may relax the steric clash and facilitate side chain rotation. The R1275 residue is located in the αA-loop helix of the proximal portion of the A-loop in the DFG motif, so that the mutation at this site would likely destabilize the helix and facilitate the shift to the αC helix. Both the F1174L and R1275Q mutants show accelerated catalytic efficiency compared with wild-type ALK with R1275Q exhibiting approximately 4-fold and F1174L exhibiting approximately 8-fold higher catalytic efficiency than the wild-type enzyme. This increased catalytic efficiency is at least partly due to the enhanced ATP binding affinity of these mutations for both ATP and peptide substrate [21].

Since the original reports, analysis of larger numbers of cases has established the overall frequency of ALK point mutations in neuroblastomas as 7-8% [43, 45, 46], with a gene amplification frequency of approximately 2% [43, 45]. Although early reports suggested a correlation between mutational status and disease stage, more recent studies have shown that ALK mutations are equally distributed among the clinical stages of tumor progression [42]. Moreover, as yet, no association between ALK mutation and survival has been established. Indeed, with the exception of F1174L mutations in MYCN-amplified tumors, somatic ALK mutations do not appear to be associated with survival.

The ALK F1174L mutant, which so far has been found to be exclusively somatic, is characterized by a higher degree of catalytic efficiency [21], autophosphorylation and more potent transforming capacity than the R1275Q mutant [43]. Conceivably, the F1174 mutation also occurs in the germline but have not been reported thus far because it is embryonic lethal. This mutation appears predominantly in tumors with MYCN gene amplification, and the combination of these two genetic alterations was associated with a particularly poor outcome in a recent meta-analysis [43]. Recently, it has been reported that this mutation can accelerate MYCN-driven tumorigenesis in animal models of neuroblastoma [47, 48]. When crossed with MYCN transgenic mice, mice overexpressing ALK-F1174L in neural crest-derived cells gave rise to doubly transgenic progeny that developed aggressive neuroblastoma with 100% penetrance and a very short latency period [47]. Similarly, coexpression of ALK-F1174L and MYCN in zebrafish markedly increased the frequency of tumor formation and accelerated the time of onset [48], suggesting a cooperative oncogenic relationship between the F1174L mutation and MYCN amplification. The explanation for such an effect is unclear but may involve stabilization of MYCN by mutated ALK. ALK-F1174L was also associated with rapid and treatment-resistant tumor growth in a patient with neuroblastoma who developed progressive disease while undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy [49]. This mutation also arises as a resistance mechanism in response to inhibitor treatment in ALK-translocated cancers [50], reinforcing the idea that ALK-F1174L plays a key role in generating high-risk forms of neuroblastoma.

3.2. Gene amplification and copy number gain

Besides its propensity to undergo point mutation, ALK is amplified in about 2% of neuroblastoma cases [43, 45]. Miyake et al.[32], first reported ALK amplification in 2002, in conjunction with MYCN amplification in neuroblastoma cell lines, with corroboration of this phenomenon in several later studies [4-6, 51]. It has become abundantly clear that ALK amplification occurs almost exclusively with MYCN amplification and may affect as many as 7-15% of primary neuroblastomas with an amplified MYCN gene [4, 43]. By contrast, ALK amplification and mutation are seldom observed within the same tumor [5, 43]. So far, ALK amplification has not been shown to have an independent correlation with aggressive disease when MYCN status is taken into consideration.

Copy number gains appear to be more common than either mutation or amplification, occurring in about 15-20% of cases [43, 45]. These largely involve either whole chromosome 2 or areas of chromosome 2p, rather than focal gain of ALK and again, are accompanied by amplification of MYCN [43]. Chromosome 2p gains including the ALK locus are associated with significantly increased ALK expression correlating with poor survival [5, 43, 52]. A multivariate analysis that included the competing covariates of MYCN status, disease stage, patient age and ALK expression showed that ALK expression was significantly associated with a poorer outcome in one of three independent data sets [43].

3.3. ALK overexpression in the absence of mutation or amplification/copy number gain

ALK is often overexpressed in the absence of discernible mutation or amplification, but the biological and clinical significance of this observation is unclear. Lamant et al. reported both RNA and protein overexpression of the full-length ALK receptor in 22 (92%) of 24 primary neuroblastomas, which did not correlate with patient outcome [53]. Other groups have subsequently reported high ALK expression and strong activation of downstream targets in neuroblastoma tumors despite the absence of ALK amplification or mutation [40, 54]. Passoni et al [52] have addressed this issue, concluding that both the mutated and wild-type receptor kinases possess oncogenic activity in neuroblastoma cells, but that the wild-type receptor requires a critical threshold of expression to achieve oncogenic activation. Indeed, in their study, constitutive phosphorylation/activation was consistently observed in cells with high expression of ALK, irrespective of whether they harbored the mutated or wild-type receptor, while cells with low expression of wild-type ALK lacked activation altogether. Also, cells overexpressing wild-type ALK were responsive to treatment with the ALK inhibitors [52]. Knockdown of ALK expression in several cell lines overexpressing an apparently wild-type ALK led to a striking decrease in cell proliferation [5, 6]. Additionally, in another study, primary neuroblastomas with elevated expression of wild-type ALK had similar clinical and molecular phenotypes as those of tumors with elevated ALK expression due to point mutations [55]. These intriguing results suggest that the high levels of ALK expression are paramount in regulating neuroblastoma cell proliferation and point to the existence of mechanisms other than mutation and amplification that not only regulate the level of expression of ALK, but may also have a role in malignant transformation and progression in neuroblastoma.

3.4. ALK signaling in neuroblastoma

Although a trove of valuable information has been published on NPM-ALK signaling, much less is known about signaling mediated by the mutated/amplified full-length ALK receptor. ALK fusion proteins lead to cell growth and survival through the activation of three major pathways: JAK-STAT, PI3K-AKT or RAS-MAPK pathways, depending on tissue context and cellular localization (Fig. 2). In neuroblastoma cell lines with ALK amplification the constitutively activated ALK forms a stable complex with hyperphosphorylated ShcC, a Src homology 2 domain-containing adaptor protein [32], resulting in deregulation of the responsiveness of the MAPK pathway to growth factors [54]. Inhibition of binding of ALK to ShcC significantly impairs the survival, differentiation and motility of neuroblastoma cells with activated ALK by blocking the MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways and inducing apoptosis [54]. Mice lacking both ShcB and ShcC display a significant loss of sympathetic neurons, suggesting that these adaptors are involved in sympathetic development and survival. Similarly, gain-of-function ALK mutations signal through the MAPK and AKT pathways, while involvement of the STAT pathway is rare in neuroblastoma [3-6]. Now that ALK mutations constitute a tractable target in neuroblastoma, it will be crucial to investigate the physiological and pathophysiological relevance of ALK-interacting proteins as well as molecules that are transcriptionally modulated by aberrant ALK activation. Otherwise it will be difficult to select candidate signaling nodes for the development of clinical therapeutics.

4. Current therapeutic options for ALK-positive neuroblastomas

4.1. Small molecule inhibitors

ALK inhibitors have been based on homology models of the insulin receptor kinase as well as high-throughput screening and the vast majority targets the ATP binding site of the catalytic domain.

The first ALK inhibitor to enter clinical trials was crizotinib (PF-2341066), an orally bioavailable, 2,4-pyrimidinediamine derivative, ATP-competitive, dual inhibitor of MET and ALK [56]. Crizotinib binds to the inactive conformation of both MET and ALK [50, 57] and has shown striking efficiency against ALK-rearranged tumors, both in mouse models and in the clinic [58, 59]. In early phase clinical testing, for example, at a mean treatment duration of 6.4 months, the overall response rate was 57% in 82 patients with EML4-ALK positive non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [59]. A phase III clinical trial of crizotinib is underway (NCT00932893, ClinicalTrials .gov) and the inhibitor is expected to be on the market in 2012 [60]. This compound is also being tested in a pediatric trial for the treatment of neuroblastoma and other solid tumors bearing ALK/mutations and rearrangements (NCT00939770, ClinicalTrials.gov). In vitro studies have shown that crizotinib is more potent in neuroblastoma cell lines with ALK amplification or the R1275Q mutation than in lines expressing the F1174L mutation [42]. Similarly, crizotinib treatment causes complete and sustained regression of xenografts harboring the R1275Q mutation, but does not inhibit the growth of F1174L-positive tumors [42]. By contrast, neuroblastoma cell lines bearing the F1174L mutation and Ba/F3 cells transduced with ALK-F1174L are very sensitive to TAE684, (5-chloro-2,4 diaminophenylpyrimidine) [4] and CRL151104A, a pyridine ATP-competitive inhibitor (ChemBridge Research Labs and St Jude Children’s Research Hospital) [7].

TAE684 was identified by screening of a kinase-targeted small-molecule library against Ba/F3 cells expressing oncogenic kinases, specifically NPM-ALK [61]. This agent is especially selective for ALK because the orthomethoxy group of TAE684 projects into a small groove located between the side chains of residues L258 and M259 of the NPM-ALK kinase domain; bulkier amino acids at the L258 position (which are seen in other kinases) would lead to a steric clash with TAE684. Treatment of neuroblastoma cells harboring the F1174L and the R1275Q ALK mutations induces rapid inhibition of phosphorylated ALK and its downstream signaling, leading to apoptosis and cell cycle arrest [4, 62].

Recently, the repertoire of ALK inhibitors was enriched by the addition of three novel compounds, two of which are being tested in early phase clinical trials [63-65]. CH5424802 (Chugai Pharmaceuticals Ltd) is a potent, selective, orally available ALK inhibitor identified from high-throughput screening against multiple RTK targets [63]. This benzo[b]carbazole derivative derived from a novel chemical scaffold exhibited potent antitumor activity against cancers with a wide range of ALK gene alterations, including NSCLC cells expressing EML4-ALK and ALCL cells expressing NPM-ALK. Importantly, CH5424802 inhibited ALK L1196M, the gatekeeper mutation that commonly confers resistance to kinase inhibitors, as well as the growth of the EML4-ALK L1196M mutant, recently identified in NSCLC patients who had relapsed after treatment with crizotinib [66]. CH5424802 compound inhibited the growth of neuroblastoma cells expressing amplified ALK both in vitro and in vivo models. The in vitro inhibitory activity in neuroblastoma cells expressing the F1174L mutation was shown to be comparable to that of wild-type ALK. However, the effect of this inhibitor on in vivo models of ALK mutated neuroblastoma is not yet clear [63]. This compound is now in phase I/II clinical trials for patients with ALK-positive NSCLC. ASP3026 (Astellas Pharma) was identified in a chemical compound screen using an ALK kinase inhibition assay aimed at EML4-ALK [64]. It inhibited ALK kinase activity in vitro at an IC50 of 3.5 nmol/L, and showed more selective ALK inhibition in a tyrosine kinase panel than did crizotinib. ASP3026 inhibited the growth of NSCLC cells expressing the EML4-ALK variant 3, both in vitro and in xenograft models. Researchers at Cephalon Inc. have also identified and characterized a highly potent, selective and orally active ALK inhibitor, CEP-28122 [65]. This compound inhibits recombinant ALK with an IC50 of 3 nM and tyrosine phosphorylation of NPM-ALK in ALCL mouse xenografts. Similar effects were observed in EML4-ALK-positive NCI-H2228 and NCI-H3122 tumor xenografts [65]. The latter two ALK inhibitors could be promising alternatives to crizotinib in patients with neuroblastoma, however, as yet, there are no published reports of their activity against neuroblastoma associated ALK mutations.

Another promising class of lead compounds is a series of novel 3,5-diamino-1,2,4-triazole benzylureas, which were developed through cell-based structure-activity relationship studies. Specifically, compounds 15a and 23a potently inhibited the growth and survival of neuroblastoma cell lines containing the F1174L mutation [67]. These potent ATP–competitive ALK inhibitors may ultimately be developed into first-line drugs for treatment of neuroblastoma.

4.2. ALK-directed immunotherapy

Immunotherapy with monoclonal antibodies targeting receptor tyrosine kinases, administered either as monotherapy or in combination with small molecule kinase inhibitors has been highly effective and widely used as treatment for malignancies such as breast and lung cancer [68, 69]. ALK would be an ideal target for antibody-based therapy given its abundant expression on the cell surface of almost all NB tumor cells and its restricted distribution normal tissues. Carpenter et al. [70] have reported that treatment of neuroblastoma cell lines with ALK-specific monoclonal antibodies induced enhanced immune cell-mediated cytotoxicity with resultant inhibition of cell proliferation and cell death. These effects were enhanced by treatment with crizotinib that induced accumulation of ALK on the cell surface, thus increasing the accessibility of antigen for antibody binding. If validated in vivo, this treatment strategy may provide a novel ALK-based option for cases of neuroblastoma that constitutively express this RTK.

4.3. RNA interference as a therapeutic modality

Targeting ALK by RNA interference is another potentially useful approach with certain advantages over conventional drug treatment, including proven efficacy against both wild-type and mutated transcripts and high sequence-specificity. A major obstacle to this modality is the specific, effective and nontoxic delivery of siRNA to its target cells. Currently, human applications of this technology are limited to targets within the liver, a natural site of accumulation of the delivery system. In a recent study DiPaolo et al. [71] took advantage of GD2, a disialoganglioside extensively expressed on tumors of neuroectodermal origin, including neuroblastoma, to direct nanoparticles carrying ALK siRNA to the tumor site. The special anti-GD(2)-targeted liposomal formulation of nanoparticles that carry ALK-directed siRNA had low plasma clearance, increased siRNA stability, and improved binding, uptake and silencing of ALK compared to free ALK-siRNA The anti-GD(2)-targeted nanoparticles were specifically and efficiently delivered to GD(2)-expressing NB cells and induced cell death in target cells. Intravenous injection of the targeted ALK-siRNA liposomes into neuroblastoma xenografts showed gene-specific antitumor activity with no side effects. Although still a long way away from the clinic, these preliminary results have the potential to be developed into therapies for children with neuroblastoma.

4.4. HSP90 inhibition

An alternative approach to targeting ALK would be to interfere with its protein stability and activation state. The heat shock proteins 90 (HSP90) and 70 (HSP70) are chaperones critical for folding, stabilization and degradation of many oncogenic kinases, including ALK [72]. Hence, perturbation of HSP90 structure would be expected to affect the stability and degradation of its bound substrates. Indeed inhibition of HSP90 in ALCL cells with 17-allylamino,17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-AAG) led to a rapid decrease in NPM-ALK expression and phosphorylation and was associated with rapid HSP70-assisted proteasomal degradation of NPM-ALK [72, 73]. Importantly, NPM-ALK/HSP complex formation depended largely on interaction with the kinase part of the fusion protein and not on the partner protein moiety, suggesting that HSP90 inhibitors may be effective in neuroblastomas with genetic aberrations in the kinase domain [73]. 17-AAG or geldanamycin, and its derivatives have also been shown to affect ALK activity by increasing the proteasome-mediated degradation of the ALK protein [73]. IPI-504, a novel HSP90 inhibitor, is undergoing phase II testing, having shown promising antitumor activity against EML4-ALK-translocated lung cancer [74-76].

4.5. Combination therapy of ALK-activated neuroblastomas

Research on targeted therapeutics against mutant receptor tyrosine kinases has been tempered by the observation that only a subset of patients respond to inhibition with disease regression, and even for these patients, the majority will develop resistant disease. Moreover, targeting a single genetic aberration may be sufficient to block tumor growth, as in the case of BCR-ABL in chronic myeloid leukemia, but once a tumor has acquired additional aberrations, this strategy generally becomes ineffective, leaving the patient with static disease that begins to progress once treatment is stopped[77]. Thus the cytotoxicity of ALK inhibitors could be significantly enhanced by targeting the critical downstream pathways that mediate ALK signaling. In addition, combinations of ALK inhibitors with other modalities that inhibit ALK such as anti-ALK antibodies, RNA interference or heat shock protein inhibitors could offer alternative treatment regimens. Such rational combinations may also prolong the duration of response and may delay or prevent the inevitable emergence of resistance seen with RTK inhibitors.

4.6. Resistance to ALK inhibitors

Although effective in patients with ALK-translocated cancers; crizotinib and other kinase inhibitors invariably lose their potency due to the emergence of drug resistance. Two groups have recently reported the development of secondary mutations after initial successful therapy with crizotinib [50, 66]. In the first case, a lung cancer patient with an EML4-ALK tumor translocation, after an initial response to crizotinib, relapsed within 5 months and became resistant to the drug. Deep sequencing of the patient’s tumor specimen revealed two new amino acid substitutions C1156Y and L1196M in the kinase domain [66]. Both mutations, when expressed together with EML4-ALK rendered Ba/F3 cells independent of IL-3 and conferred resistance to crizotinib. L1196 in the ALK crystal structure corresponds to threonine 315 in ABL and 790 in EGFR and is located at the bottom of the ATP-binding pocket. Each of these positions is the site of the most frequently acquired mutations that confer resistance to the inhibitors of those kinases. The presence of amino acids with bulky side chains at this “gatekeeper” position, such as methionine, may interfere with the binding of the kinase inhibitor.

The second report of ALK resistance to crizotinib involved identification of the F1174L mutation in a patient with inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) bearing the RANBP2-ALK translocation, who had relapsed after initially successful therapy with crizotinib [50]. When F1174L is in cis with ALK translocation, it increases ALK phosphorylation, cell growth, downstream signaling and blocks apoptosis in Ba/F3 cells coexpressing RANBP2-ALK with F1174L. The structurally different ALK inhibitor TAE684 and the HSP90 inhibitor 17-AAG effectively inhibited the growth of Ba/F3 cells expressing these two ALK variants. Based on the ALK crystal structure, the authors suggest that the F1174L mutation may very effectively destabilize the αC helix in the activation loop and promote the active conformation. Thus, the crystal structure of ALK in the active confirmation, and of the F1174L mutant in particular, will likely facilitate the development of the second-generation inhibitors that would effectively target these resistance mutants.

One of the mechanisms by which cancer cells with activated mutant kinases evade treatment with kinase inhibitors is to switch to alternative signaling pathways. Thus, it was reported recently that NSCLC cells with MET gene amplification develop resistance to crizotinib by overexpressing the EGFR receptor [78]. Although a similar finding has not been reported for ALK, it remains a definite possibility, as increased expression of this receptor was recently detected in an ALK-mutated neuroblastoma cell line made resistant to crizotinib [79]. If constitutive expression of the EGFR receptor represents a mechanism of stable resistance to ALK inhibitors, it would indicate the feasibility of predicting resistance mechanisms that are likely to emerge in patients treated with newer generations of ALK inhibitors.

5. Unanswered questions

One of the most intriguing questions in ALK biology is the normal function of the ALK receptor during development and in adult life. The failure of ALK knockout mouse models to reveal significant phenotypes [7, 25] has been frustrating, indicating that other research avenues will need to be explored to understand the normal function of ALK. One possibility is that in normal development ALK functions as a dependence receptor, mediating the programmed cell death of neurons in the sympathetic nervous system. In the context of ALK activation, however, neuroblasts may not undergo apoptosis but hyperproliferate instead, leading to tumor formation. Although pleotrophin and midkine are thought to be important ligands for ALK, the relevance of their interaction with the kinase needs to be addressed, particularly the notion that different ligands may be utilized in different developmental contexts. Indeed, efforts to identify new ALK ligands, such as the “Jeb-like” protein, and understand their normal functions as well as their possible roles in neuroblastoma development need to be accelerated.

Mutations and amplifications of the ALK gene represent only a small fraction of neuroblastoma cases. What about the rest? Intriguingly, knockdown of ALK in neuroblastoma cells bearing the wild-type copy of this gene leads to apoptosis and cell death [5,52], implying a wider role for the kinase in this disease. Moreover, many neuroblastoma cell lines expressing single copies of ALK show phosphorylation of the receptor in the absence of point mutations [4]. Whether phosphorylated, non-mutated and non-amplified ALK contributes significantly to the pathogenesis of neuroblastoma, and the mechanism of this contribution, remain fascinating questions for future studies.

Recent efforts to establish transgenic animal models of ALK F1174L-MYCN driven neuroblastomas are encouraging, as they may help to define more precisely the role of mutant ALK in neuroblastoma development and could provide useful tools for therapeutic testing. Even so, a number of important issues must be considered before these findings can be translated into the clinic. For example, do activating mutations other than F1174L cooperate with MYCN during neuroblastoma pathogenesis, and, if so, to what extent? Although the exact link between MYCN and ALK remains to be elucidated, targeting ALK with shRNA inhibited cell growth in tumor lines with concomitant MYCN amplification, suggesting that ALK inhibition may provide an effective targeting strategy against MYCN-amplified tumors.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sydney Kimmel Translational Research Scholar Award (REG), 1 R01 CA148688-01A1 (REG), Friends for Life Neuroblastoma Fund (AA).

Footnotes

Conflict of interests None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Morris SW, Kirstein MN, Valentine MB, Dittmer KG, Shapiro DN, Saltman DL, et al. Fusion of a kinase gene, ALK, to a nucleolar protein gene, NPM, in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Science. 1994;263:1281–4. doi: 10.1126/science.8122112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiarle R, Voena C, Ambrogio C, Piva R, Inghirami G. The anaplastic lymphoma kinase in the pathogenesis of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:11–23. doi: 10.1038/nrc2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Y, Takita J, Choi YL, Kato M, Ohira M, Sanada M, et al. Oncogenic mutations of ALK kinase in neuroblastoma. Nature. 2008;455:971–4. doi: 10.1038/nature07399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.George RE, Sanda T, Hanna M, Frohling S, Luther W, 2nd, Zhang J, et al. Activating mutations in ALK provide a therapeutic target in neuroblastoma. Nature. 2008;455:975–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janoueix-Lerosey I, Lequin D, Brugieres L, Ribeiro A, de Pontual L, Combaret V, et al. Somatic and germline activating mutations of the ALK kinase receptor in neuroblastoma. Nature. 2008;455:967–70. doi: 10.1038/nature07398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosse YP, Laudenslager M, Longo L, Cole KA, Wood A, Attiyeh EF, et al. Identification of ALK as a major familial neuroblastoma predisposition gene. Nature. 2008;455:930–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webb TR, Slavish J, George RE, Look AT, Xue L, Jiang Q, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase: role in cancer pathogenesis and small-molecule inhibitor development for therapy. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:331–56. doi: 10.1586/14737140.9.3.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathew P, Morris SW, Kane JR, Shurtleff SA, Pasquini M, Jenkins NA, et al. Localization of the murine homolog of the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (AlK) gene on mouse chromosome 17. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1995;70:143–4. doi: 10.1159/000134080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmer RH, Vernersson E, Grabbe C, Hallberg B. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase: signalling in development and disease. Biochem J. 2009;420:345–61. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwahara T, Fujimoto J, Wen D, Cupples R, Bucay N, Arakawa T, et al. Molecular characterization of ALK, a receptor tyrosine kinase expressed specifically in the nervous system. Oncogene. 1997;14:439–49. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris SW, Naeve C, Mathew P, James PL, Kirstein MN, Cui X, et al. ALK, the chromosome 2 gene locus altered by the t(2;5) in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, encodes a novel neural receptor tyrosine kinase that is highly related to leukocyte tyrosine kinase (LTK) Oncogene. 1997;14:2175–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pulford K, Lamant L, Morris SW, Butler LH, Wood KM, Stroud D, et al. Detection of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and nucleolar protein nucleophosmin (NPM)-ALK proteins in normal and neoplastic cells with the monoclonal antibody ALK1. Blood. 1997;89:1394–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Degoutin J, Brunet-de Carvalho N, Cifuentes-Diaz C, Vigny M. ALK (Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase) expression in DRG neurons and its involvement in neuron-Schwann cells interaction. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:275–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li R, Morris SW. Development of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) small-molecule inhibitors for cancer therapy. Med Res Rev. 2008;28:372–412. doi: 10.1002/med.20109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stoica GE, Kuo A, Powers C, Bowden ET, Sale EB, Riegel AT, et al. Midkine binds to anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and acts as a growth factor for different cell types. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35990–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205749200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Powers C, Aigner A, Stoica GE, McDonnell K, Wellstein A. Pleiotrophin signaling through anaplastic lymphoma kinase is rate-limiting for glioblastoma growth. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:14153–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112354200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stoica GE, Kuo A, Aigner A, Sunitha I, Souttou B, Malerczyk C, et al. Identification of anaplastic lymphoma kinase as a receptor for the growth factor pleiotrophin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16772–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010660200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hubbard SR, Wei L, Ellis L, Hendrickson WA. Crystal structure of the tyrosine kinase domain of the human insulin receptor. Nature. 1994;372:746–54. doi: 10.1038/372746a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munshi S, Kornienko M, Hall DL, Reid JC, Waxman L, Stirdivant SM, et al. Crystal structure of the Apo, unactivated insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor kinase. Implication for inhibitor specificity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38797–802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205580200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tartari CJ, Gunby RH, Coluccia AM, Sottocornola R, Cimbro B, Scapozza L, et al. Characterization of some molecular mechanisms governing autoactivation of the catalytic domain of the anaplastic lymphoma kinase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:3743–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706067200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee CC, Jia Y, Li N, Sun X, Ng K, Ambing E, et al. Crystal structure of the ALK (anaplastic lymphoma kinase) catalytic domain. Biochem J. 2010;430:425–37. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bossi RT, Saccardo MB, Ardini E, Menichincheri M, Rusconi L, Magnaghi P, et al. Crystal structures of anaplastic lymphoma kinase in complex with ATP competitive inhibitors. Biochemistry. 2010;49:6813–25. doi: 10.1021/bi1005514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vernersson E, Khoo NK, Henriksson ML, Roos G, Palmer RH, Hallberg B. Characterization of the expression of the ALK receptor tyrosine kinase in mice. Gene Expr Patterns. 2006;6:448–61. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hurley SP, Clary DO, Copie V, Lefcort F. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase is dynamically expressed on subsets of motor neurons and in the peripheral nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 2006;495:202–12. doi: 10.1002/cne.20887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bilsland JG, Wheeldon A, Mead A, Znamenskiy P, Almond S, Waters KA, et al. Behavioral and neurochemical alterations in mice deficient in anaplastic lymphoma kinase suggest therapeutic potential for psychiatric indications. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:685–700. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loren CE, Englund C, Grabbe C, Hallberg B, Hunter T, Palmer RH. A crucial role for the Anaplastic lymphoma kinase receptor tyrosine kinase in gut development in Drosophila melanogaster. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:781–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loren CE, Scully A, Grabbe C, Edeen PT, Thomas J, McKeown M, et al. Identification and characterization of DAlk: a novel Drosophila melanogaster RTK which drives ERK activation in vivo. Genes Cells. 2001;6:531–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Souttou B, Carvalho NB, Raulais D, Vigny M. Activation of anaplastic lymphoma kinase receptor tyrosine kinase induces neuronal differentiation through the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9526–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007333200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Motegi A, Fujimoto J, Kotani M, Sakuraba H, Yamamoto T. ALK receptor tyrosine kinase promotes cell growth and neurite outgrowth. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:3319–29. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piccinini G, Bacchiocchi R, Serresi M, Vivani C, Rossetti S, Gennaretti C, et al. A ligand-inducible epidermal growth factor receptor/anaplastic lymphoma kinase chimera promotes mitogenesis and transforming properties in 3T3 cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:22231–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111145200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perez-Pinera P, Zhang W, Chang Y, Vega JA, Deuel TF. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase is activated through the pleiotrophin/receptor protein-tyrosine phosphatase beta/zeta signaling pathway: an alternative mechanism of receptor tyrosine kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28683–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704505200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miyake I, Hakomori Y, Shinohara A, Gamou T, Saito M, Iwamatsu A, et al. Activation of anaplastic lymphoma kinase is responsible for hyperphosphorylation of ShcC in neuroblastoma cell lines. Oncogene. 2002;21:5823–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gouzi JY, Moog-Lutz C, Vigny M, Brunet-de Carvalho N. Role of the subcellular localization of ALK tyrosine kinase domain in neuronal differentiation of PC12 cells. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5811–23. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dirks WG, Fahnrich S, Lis Y, Becker E, MacLeod RA, Drexler HG. Expression and functional analysis of the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene in tumor cell lines. Int J Cancer. 2002;100:49–56. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Englund C, Loren CE, Grabbe C, Varshney GK, Deleuil F, Hallberg B, et al. Jeb signals through the Alk receptor tyrosine kinase to drive visceral muscle fusion. Nature. 2003;425:512–6. doi: 10.1038/nature01950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Varshney GK, Palmer RH. The bHLH transcription factor Hand is regulated by Alk in the Drosophila embryonic gut. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351:839–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee HH, Norris A, Weiss JB, Frasch M. Jelly belly protein activates the receptor tyrosine kinase Alk to specify visceral muscle pioneers. Nature. 2003;425:507–12. doi: 10.1038/nature01916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mourali J, Benard A, Lourenco FC, Monnet C, Greenland C, Moog-Lutz C, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase is a dependence receptor whose proapoptotic functions are activated by caspase cleavage. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6209–22. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01515-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muramatsu T. Midkine and pleiotrophin: two related proteins involved in development, survival, inflammation and tumorigenesis. J Biochem. 2002;132:359–71. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a003231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caren H, Abel F, Kogner P, Martinsson T. High incidence of DNA mutations and gene amplifications of the ALK gene in advanced sporadic neuroblastoma tumours. Biochem J. 2008;416:153–9. doi: 10.1042/bj20081834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Longo L, Borghini S, Schena F, Parodi S, Albino D, Bachetti T, et al. PHOX2A and PHOX2B genes are highly co-expressed in human neuroblastoma. Int J Oncol. 2008;33:985–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wood AC, L M, Haglund EA, Attiyeh EF, Pawel B, Courtright J, Plegaria J, Christensen JG, Maris JM, Mosse YP. Inhibition of ALK mutated neuroblastomas by the selective inhibitor PF-02341066. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15s. suppl; abstr 10008b. [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Brouwer S, De Preter K, Kumps C, Zabrocki P, Porcu M, Westerhout EM, et al. Meta-analysis of neuroblastomas reveals a skewed ALK mutation spectrum in tumors with MYCN amplification. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;16:4353–62. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mazot P, Cazes A, Boutterin MC, Figueiredo A, Raynal V, Combaret V, et al. The constitutive activity of the ALK mutated at positions F1174 or R1275 impairs receptor trafficking. Oncogene. 30:2017–25. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weiser D, L M, Rappaport E, Carpenter E, Attiyeh EF, Diskin S, London WB, Maris JM, Mosse YP. Stratification of patients with neuroblastoma for targeted ALK inhibitor therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schulte JH, Bachmann HS, Brockmeyer B, Depreter K, Oberthur A, Ackermann S, et al. High ALK Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Expression Supersedes ALK Mutation as a Determining Factor of an Unfavorable Phenotype in Primary Neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5082–92. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.George R, L W, Ahmad Z, Cullis E, Webber H, Rodig S, Pearson A, Chesler L. The ALK-F1174L mutation accelerates MYCN-driven tumorigenesis in a murine transgenic neuroblastoma model[abstract]. Proceedings of the 102nd Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research; 2011 Apr 2-6; Orlando, Florida. Philadelphia (PA). AACR; 2011. Abstract nr 4757. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu S, L J, Shin J, Perez-Atayde A, Kutok J, Rodig S, Neuberg D, Guo F, Helman D, Feng H, Stewart R, Wang W, George R, Kanki J, Look A. Activated ALK accelerates the onset of neuroblastoma in MYCN-transgenic zebrafish [abstract]. Proceedings of the 102nd Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research; 2011 Apr 2-6; Orlando, Florida. Philadelphia (PA). AACR; 2011. Abstract nr 4296. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martinsson T, Eriksson T, Abrahamsson J, Caren H, Hansson M, Kogner P, et al. Appearance of the novel activating F1174S ALK mutation in neuroblastoma correlates with aggressive tumor progression and unresponsiveness to therapy. Cancer Res. 2011;71:98–105. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sasaki T, Okuda K, Zheng W, Butrynski J, Capelletti M, Wang L, et al. The neuroblastoma-associated F1174L ALK mutation causes resistance to an ALK kinase inhibitor in ALK-translocated cancers. Cancer Res. 2010;70:10038–43. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.George RE, Attiyeh EF, Li S, Moreau LA, Neuberg D, Li C, et al. Genome-wide analysis of neuroblastomas using high-density single nucleotide polymorphism arrays. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Passoni L, Longo L, Collini P, Coluccia AM, Bozzi F, Podda M, et al. Mutation-independent anaplastic lymphoma kinase overexpression in poor prognosis neuroblastoma patients. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7338–46. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lamant L, Pulford K, Bischof D, Morris SW, Mason DY, Delsol G, et al. Expression of the ALK tyrosine kinase gene in neuroblastoma. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1711–21. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65042-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Osajima-Hakomori Y, Miyake I, Ohira M, Nakagawara A, Nakagawa A, Sakai R. Biological role of anaplastic lymphoma kinase in neuroblastoma. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:213–22. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62966-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schulte JH, Bachmann HS, Brockmeyer B, De Preter K, Oberthuer A, Ackermann S, et al. High ALK receptor tyrosine kinase expression supersedes ALK mutation as a determining factor of an unfavorable phenotype in primary neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zou HY, Li Q, Lee JH, Arango ME, McDonnell SR, Yamazaki S, et al. An orally available small-molecule inhibitor of c-Met, PF-2341066, exhibits cytoreductive antitumor efficacy through antiproliferative and antiangiogenic mechanisms. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4408–17. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Timofeevski SL, McTigue MA, Ryan K, Cui J, Zou HY, Zhu JX, et al. Enzymatic characterization of c-Met receptor tyrosine kinase oncogenic mutants and kinetic studies with aminopyridine and triazolopyrazine inhibitors. Biochemistry. 2009;48:5339–49. doi: 10.1021/bi900438w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Christensen JG, Zou HY, Arango ME, Li Q, Lee JH, McDonnell SR, et al. Cytoreductive antitumor activity of PF-2341066, a novel inhibitor of anaplastic lymphoma kinase and c-Met, in experimental models of anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:3314–22. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Solomon B, Maki RG, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1693–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rodig SJ, Shapiro GI. Crizotinib, a small-molecule dual inhibitor of the c-Met and ALK receptor tyrosine kinases. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;11:1477–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Galkin AV, Melnick JS, Kim S, Hood TL, Li N, Li L, et al. Identification of NVP-TAE684, a potent, selective, and efficacious inhibitor of NPM-ALK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:270–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609412103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McDermott U, Iafrate AJ, Gray NS, Shioda T, Classon M, Maheswaran S, et al. Genomic alterations of anaplastic lymphoma kinase may sensitize tumors to anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3389–95. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sakamoto H, Tsukaguchi T, Hiroshima S, Kodama T, Kobayashi T, Fukami TA, et al. CH5424802, a selective ALK inhibitor capable of blocking the resistant gatekeeper mutant. Cancer Cell. 19:679–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kuromitsu S, M M, S I, Kondoh Y, Shindoh N, Soga T, Furutani T, Konagai S, Sakagami H, Nakata M, Ueno Y, Saito R, Sasamata M, M H, Kudou M. Anti-tumor activity of ASP3026, - A novel and selective ALK inhibitor - [abstract]. Proceedings of the 102nd Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research; Orlando, Florida Philadelphia (PA). 2011. Abstract nr 2821. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheng M, Q M, G D, Ott G, Lu L, Wan W, Albom M, Angeles T, Aimone L, Cristofani F, Machiorlatti R, Abele C, Ator M, Dorsey B, I G, Ruggeri B AACR; 2011. Identification and preclinical characterization of CEP-28122, a highly potent and selective orally active inhibitor of anaplastic lymphoma kinase, in lymphoma and non-small cell lung cancer models [abstract]. Proceedings of the 102nd Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research; Orlando, Florida Philadelphia (PA). 2011. Abstract nr 3574. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Choi YL, Soda M, Yamashita Y, Ueno T, Takashima J, Nakajima T, et al. EML4-ALK mutations in lung cancer that confer resistance to ALK inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1734–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Deng X, Wang J, Zhang J, Sim T, Kim ND, Sasaki T, et al. Discovery of 3,5-Diamino-1,2,4-triazole Ureas as Potent Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase Inhibitors. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2011;2:379–84. doi: 10.1021/ml200002a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stoffel A. Targeted therapies for solid tumors: current status and future perspectives. BioDrugs. 2010;24:303–16. doi: 10.2165/11535880-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Martinelli E, Troiani T, Morgillo F, Rodolico G, Vitagliano D, Morelli MP, et al. Synergistic antitumor activity of sorafenib in combination with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors in colorectal and lung cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4990–5001. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carpenter E, H E, Chow A, Christensen J, Maris J, Mosse Y. Mechanisms of resistance to small molecule inhibition of anaplastic lymphoma kinase in human neuroblastoma [abstract]. Proceedings of the 102nd Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research; 2011 Apr 2-6; Orlando, Florida. Philadelphia (PA). AACR; 2011. Abstract nr 742. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Di Paolo D, Brignole C, Pastorino F, Carosio R, Zorzoli A, Rossi M, et al. Neuroblastoma-targeted Nanoparticles Entrapping siRNA Specifically Knockdown ALK. Mol Ther. 2011 doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bonvini P, Gastaldi T, Falini B, Rosolen A. Nucleophosmin-anaplastic lymphoma kinase (NPM-ALK), a novel Hsp90-client tyrosine kinase: down-regulation of NPM-ALK expression and tyrosine phosphorylation in ALK(+) CD30(+) lymphoma cells by the Hsp90 antagonist 17-allylamino,17-demethoxygeldanamycin. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1559–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bonvini P, Dalla Rosa H, Vignes N, Rosolen A. Ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of nucleophosmin-anaplastic lymphoma kinase induced by 17-allylamino-demethoxygeldanamycin: role of the co-chaperone carboxyl heat shock protein 70-interacting protein. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3256–64. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sequist LV, Gettinger S, Senzer NN, Martins RG, Janne PA, Lilenbaum R, et al. Activity of IPI-504, a novel heat-shock protein 90 inhibitor, in patients with molecularly defined non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4953–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.8338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen Z, Sasaki T, Tan X, Carretero J, Shimamura T, Li D, et al. Inhibition of ALK, PI3K/MEK, and HSP90 in murine lung adenocarcinoma induced by EML4-ALK fusion oncogene. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9827–36. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Normant E, Paez G, West KA, Lim AR, Slocum KL, Tunkey C, et al. The Hsp90 inhibitor IPI-504 rapidly lowers EML4-ALK levels and induces tumor regression in ALK-driven NSCLC models. Oncogene. 2011 doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Engelman JA, Settleman J. Acquired resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors during cancer therapy. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:73–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McDermott U, Pusapati RV, Christensen JG, Gray NS, Settleman J. Acquired resistance of non-small cell lung cancer cells to MET kinase inhibition is mediated by a switch to epidermal growth factor receptor dependency. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1625–34. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Carpenter ELHE, Chow AK, Christensen JG, Maris JM, Mosse YP. Mechanisms of resistance to small molecule inhibition of anaplastic lymphoma kinase in human neuroblastoma. AACR Annual Meeting Proceedings. 2011 Abstract #742. [Google Scholar]