Abstract

Prolonged exposure, a cognitive behavioral therapy including both in vivo and imaginal exposure to the traumatic memory, is one of several empirically supported treatments for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In this article, we provide a case illustration in which this well-validated treatment did not yield expected clinical gains for a client with PTSD and co-occurring major depression. After providing an overview of the literature, theory, and treatment protocol, we discuss the clinical cascade effect that underlying ruminative processes had on the treatment of this case. Specifically, we highlight how ruminative processes, focusing on trying to understand why the traumatic event happened and why the client was still suffering, resulted in profound emotional distress in session and in a lack of an “optimal dose” of exposure during treatment.

Exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) helps individuals to lessen their trauma-related anxiety by approaching the traumatic memory and situations that they avoid because of the trauma. A variant of exposure therapy, prolonged exposure (PE), has been shown to be efficacious for a broad range of trauma samples (e.g., Foa, Rothbaum, Riggs, & Murdock, 1991; Foa, Dancu, Hembree, Jaycox, Meadows, & Street, 1999; Foa et al., 2005; Paunovic & Ost, 2001; Resick, Nishith, Weaver, Astin, & Feuer, 2002; Rothbaum, Astin, & Marsteller, 2005; Schnurr et al., 2007). Typically, pre- to posttreatment effect sizes for PTSD severity are in the large range (Cohen's d>.8) with gains maintained over time. Further, PE also reduces co-occurring depression symptoms (e.g., Foa et al., 1999; Foa et al., 2005), with some preliminary evidence of effect sizes actually increasing with co-occurring depression (Feeny, Zoellner, Mavissakalian, & Roy-Byrne, 2009). In a recent report on the state of PTSD treatment, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) noted that following an extensive review of pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions, only exposure therapies could be considered sufficiently empirically supported (IOM, 2007).

Because Pavlovian fear conditioning is often considered the mode of acquisition in PTSD, the mechanism underlying exposure therapy has been linked to the process of extinction. Specifically, the traumatic event (an unconditioned stimuli, UCS) evoking intense fear occurs in the presence of a variety of neutral cues (e.g., time of day, sights, sounds, smells, people), which become conditioned stimuli (CSs) for activating persistent anxiety-based reactions (conditioned responses, or CRs) such as reexperiencing of the trauma memory and physiological reactivity upon exposure to nondangerous trauma-related cues. In contrast to fear acquisition, extinction learning occurs through repeatedly presenting a CS without the UCS, resulting in a diminished CR. Here, the extinction process does not erase original learning; instead, extinction results in the acquisition of an inhibitory association that suppresses activation of the CR (Bouton, 1988, 2004). Emotional processing theory (Foa & Kozak, 1986; Rachman, 1980) extends this and provides a broader theoretical framework highlighting the role of the overgeneralization of fear schemas (e.g., associations around trauma-related stimuli, responses, and meanings). Repeated and prolonged exposure provides the avenue for accessing and modifying pathological trauma-related fear schema. Accordingly, exposure therapy for PTSD involves repeatedly approaching feared but safe thoughts, images, objects, situations, or activities in order to reduce unrealistic anxiety and other reactions.

Overview of Treatment

PE (see Foa, Hembree, & Rothbaum, 2007) is an individual therapy that typically consists of nine to twelve 90- to 120-min weekly or twice weekly sessions. The initial sessions of PE focus on providing the treatment rationale and general psychoeducation, focusing on the symptoms of PTSD and the factors that maintain the disorder. The main active component of the treatment is exposure: in vivo (in life) exposure and imaginal exposure. In vivo exposure involves systematically approaching feared situations, places, and activities that the client has been avoiding since his or her trauma. Imaginal exposure involves systematically revisiting key aspects of the traumatic event. Finally, the last session involves highlighting the client's progress in treatment and a discussion of relapse prevention.

Initial Therapy Sessions

After a thorough diagnostic assessment and confirmation of a primary diagnosis of PTSD, initial therapy sessions involve providing an overview of the treatment components, the treatment rationale, psychoeducation, breathing retraining, and gathering more detailed trauma-specific information, while building rapport with the client. The purpose of these sessions is to set a strong foundation for the subsequent therapeutic work and gradually introduce exposure elements.

One of the main goals of these initial sessions is helping the client understand the rationale underlying PE, including providing general psychoeducation about the nature of PTSD and factors related to the persistence of PTSD. This discussion includes normalizing trauma-related reactions and noting that while avoidance is an effective method for managing anxiety in the short-term, it is not a successful long-term strategy, as fear persists. The clinician also describes the role of unhelpful beliefs about oneself, other people, and the world in maintaining PTSD symptoms. Finally, the clinician describes how exposure teaches that trauma reminders are not dangerous, modifies extreme and unhelpful beliefs, and that the client can successfully manage his or her anxiety. Although these conversations are largely didactic, the therapist seeks to elicit the client's own experiences in the discussion.

In Vivo Exposure

As part of the rationale for exposure, the therapist provides a detailed discussion of how in vivo exposure helps clients to learn that situations they have avoided are not dangerous, to challenge unhelpful beliefs, and to respond to these situations with less anxiety. The therapist and the client work together to create an in vivo hierarchy across a range of trauma-related, anxiety-provoking situations. This hierarchy includes situations that the client avoids because he or she perceives them as dangerous, that remind him or her of the traumatic event, or that are avoided because the client finds them less interesting or enjoyable since the trauma. During this discussion, the therapist and client pay particular attention to activities, situations, or places that dramatically impair current functioning and where the client is particularly motivated to make change. The therapist may need to address motivation issues, particularly in areas that are significantly impairing current functioning. Ideally, the hierarchy will include 15 to 20 items of varying distress levels, in order to give ample opportunity for the client to practice between two to three situations per week while moving to increasingly distressing items over the course of the treatment. Once such a hierarchy is created, the therapist and client collaboratively choose two or three items in the moderate fear range for initial homework in order to give the client situations that are challenging yet ultimately have a high likelihood of initial mastery. The client is asked to practice the situation multiple times before the next session, staying long enough for distress level to fall by 50% or for a specified period of time.

Imaginal Exposure

Imaginal exposure is a way for the client to process the emotions tied to the traumatic event, to learn that they can remember the event without severe distress, and to differentiate the memory from the initial traumatic experience. Often, the client will have experienced a number of different traumatic events, and the therapist and client will choose which events to focus on during imaginal exposure. As a general rule, the event or events that are chosen are those perceived by the client to be the worst, particularly ones that are repeatedly reexperienced with severe distress in intrusions, nightmares, or flashbacks.

During imaginal exposure, the client is asked to revisit his or her memory of the event as vividly as possible, in the present tense, with their eyes closed, while focusing on their thoughts, feelings, sensations, actions, as well as surroundings and the actions of others. In the first imaginal exposure, the therapist allows the client to approach the trauma memory at his or her own pace, without being too directive so that the client feels in control of their reliving. This allows the client to learn that the memory is not dangerous and that he or she will not fall apart in revisiting the trauma memory. The therapist monitors the client's distress and vividness, as well as noting unhelpful thoughts and beliefs for later discussion.

In order to promote extinction, the revisiting of the memory is repeated for approximately 45 to 60 min. After the imaginal exposure is complete, the therapist and client process the client's experience of the reliving for 15 to 20 min, particularly focusing on unhelpful beliefs and how the client's experience of distress changed. During processing, the therapist validates the client's experience and reinforces the client's strength and courage for beginning the work approaching the traumatic memory. For homework, the client is asked to listen to the tape of the imaginal exposure daily. The therapist explains to the client how to promote engagement with the memory (e.g., avoid listening to the tape when other people are around, when performing other activities, and at bedtime).

Subsequent Sessions

As the therapy sessions progress, focus shifts to moving up the in vivo hierarchy and recalling “hot spots” in the traumatic memory. During in vivo, particular attention is paid to providing support and facilitating successful new learning, while moving to more distressing situations and content. The focus of the imaginal exposure shifts to the most distressing aspects of the traumatic memory, identifying what are termed “hot spots.” These spots are identified as places in the narrative related to reexperiencing, where the client experiences high distress, parts of the memory where the client skips over critical but remembered details of the memory, or where there is a lack of affect for an aspect of the memory where the client experienced extreme distress at the time. The imaginal exposure sessions then shift to prolonged and repeated exposure of these hot spots.

Throughout subsequent exposures, the therapist pays particular attention to engagement with the traumatic memory, intervening when the client is not able to access trauma-related fear, termed underengagement, or is too distressed and is no longer able to tolerate this distress, termed overengagement. For example, the therapist can enhance engagement by asking probe questions to better focus the client on thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations during the event or can help the client lower engagement by shifting to revisiting in past tense or reminding the client that the memory is just a memory. Finally, as the therapy progresses, discussion of both the imaginal exposure and in vivo exposure homework assignments turns to identifying and addressing recurrent themes about oneself, other people, and the world.

Clinical Illustration1

Angela, a 48-year-old Caucasian woman, sought treatment because she was disturbed by images and thoughts of her husband's suicide that occurred approximately a year and a half earlier. She also reported crying frequently, having to force herself to leave the house to run errands, and having problems sleeping. This made her irritable, strained her relationships, particularly with her father and children, and rendered her unable to work. Prior to the suicide, her husband, Adrian, had been laid off from his 17-year job as an engineer. To further complicate the picture, the couple had assumed care of her 86-year-old widowed father, Bert, who has progressive Alzheimer's disease and had a son with acute myelogenous leukemia. Her husband's unemployment had led to a substantial drain in finances and a strain on the marriage. While out of town for a business meeting, Angela received multiple voice-mail messages from her father telling her to call home. When she finally reached him, the only thing she could make out was that Adrian was dead. When she arrived home hours later, her father told her that Adrian did not bring him his morning medication. He had called out for Adrian and heard no reply. When he walked down the stairs, he found Adrian dead, hanging in his basement workshop.

Initial Assessment

As part of our standardized procedures, Angela was assessed for PTSD using semistructured diagnostic measures (PTSD Symptom Scale–Interview [PSS-I; Foa, Riggs, Dancu, & Rothbaum, 1993]), other Axis I disorders (Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV [SCID-IV; Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon, & First, 1992]), and general functioning (Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [HRSD24; Hamilton, 1960]; Social Adjustment Scale [SAS: Weissman & Paykel, 1974]). Angela reported moderate to severe symptoms across all PTSD clusters, qualifying for a diagnosis of chronic PTSD (PSS-I=38). She noted the severity of her reexperiencing, particularly having intrusive images of her husband tying the noose and of his dead body hanging from the ceiling beams, despite the fact that she never actually saw these events. She also reported classic avoidance, including avoiding the basement and removing Adrian's things from the house, and numbing symptoms, including losing interest in things she previously enjoyed and feeling so detached from others that she felt like she was “living two lives.” In the hyperarousal cluster, Angela reported frequent irritability with her father and children, problems sleeping, and impaired concentration to the point that she could not follow the plot of 30-minute sitcoms she used to love. Despite these significant trauma-related symptoms, she reported no hypervigilance or exaggerated startle responses.

Although PTSD was her primary diagnosis, Angela also met criteria for a secondary diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD) in the moderate to severe range (HRSD24 = 31) that coincided with the onset of the trauma. There was no history of past or current suicidality (i.e., no previous ideation, no past attempts, no current intent, no current plan). Given this predominance of both PTSD and depression, we considered whether Angela's symptom profile was better accounted for by complicated grief, albeit not a DSM-IV diagnostic category. Complicated grief includes feelings of sadness, anhedonia, and guilt that are focused primarily on memories of the deceased and a preoccupation with positive thoughts and memories about “how it used to be” (see Shear, Frank, Houck, & Reynolds, 2005). Angela's symptoms did not fit, as she did not report having positive memories of her husband or yearning for him to be alive. Further, the therapeutic elements of PE are similar to those utilized in the treatment of complicated grief (Shear et al., 2005). For these reasons, the choice to utilize PE in Angela's treatment was deemed appropriate.

Course of Treatment

Angela began a 10-session weekly course of PE for PTSD and depression symptoms. One of the main issues in treatment emerged early in the first session. While being hopeful at the prospect of “not hurting anymore” and wanting to alleviate the intrusive thoughts about the suicide that “play over and over again in my head,” she reported feeling overwhelmed with emotions, including self-blame (how she “should have known”) and sadness. She sobbed repeatedly throughout her sessions. This flood of thoughts and emotions emerged not only during sessions but also when completing homework assignments, such as when practicing the breathing. Commonly, this flood of emotions focused on her own suffering or about Adrian's last moments alive: “I can see him sitting in his basement woodshop, tying the noose, thinking about the last thing he thought. It drives me crazy. That's what haunts me most.”

It was clear that therapy was one of her only emotional outlets, as she had only a few friends and was not discussing how she was doing with them. Accordingly, one of our main goals in setting up her in vivo hierarchy was to not only help her approach things she had been avoiding because they reminded her of the suicide (e.g., Adrian's possessions and the basement, where she needed to go to do laundry), but also to help reduce her isolation by increasing her social interactions and providing other avenues for specific social support (e.g., cancer and Alzheimer's caregivers' support services).

Given that many of her intrusions centered on how she imagined things might have happened (e.g., her husband tying the noose) rather than actual memories, it was challenging to decide what to target during imaginal exposure. We chose to focus on Angela's memory of learning of her husband's death and later entering his basement workshop for the first time. These two memories focused on reality, with the latter memory of going down to the basement containing images of what she imagined (i.e., Adrian hanging there). As we shifted toward hot spots in subsequent sessions, Angela suggested “imagining the last minutes of his life” as a potential hot spot. Given that we did not want to conduct exposure to an imagined scenario, we decided to focus instead on entering the basement workshop after the suicide as a hot spot. During her first and subsequent retellings of the suicide, Angela's narrative sounded similar to a police report with little elaboration of the most difficult and painful parts of the trauma. An excerpt below illustrates a typical imaginal exposure:

ANGELA: As I am entering the basement, I don't want to believe it, I know in my heart and head if I don't admit it it's not true [starts tearing]. I walk down the stairs and see his work bench [begins crying].

THERAPIST: SUDs?

ANGELA: One hundred. As I reach the bottom step … I can better see where he hung himself. His workshop is bare, the police have cleared out his work bench [crying escalates]. I imagine him sitting in his basement workshop, tying the noose, wonder about the last thing he thought. His pain is over. I don't want to live like this. I can't live with it.

Although Angela consistently reported high distress and sobbed throughout the revisiting, her narrative was missing details not only about the event itself but also about what she was thinking, feeling, and sensing during the event. Over the course of subsequent sessions, we pushed for deeper focus through reviewing the rationale for reliving, modeling revisiting with thoughts and feelings, and asking probe questions to increase thoughts and feelings. Nevertheless, she continued to show repeated distress, minimal details about her own experiences, and minimal distress reduction across sessions.

The amount of time allocated for imaginal exposure and processing was often shortened due to managing insession distress, with imaginal exposure often starting late in the session. Processing itself focused on the overarching question of why Adrian killed himself and the self-blame she still felt about how she should have known or prevented the suicide. The underlying goals were to help her accept that she would never know for sure why Adrian had killed himself and to refocus her blame appropriately. Specifically, Angela started identifying inaccurate thoughts related to self-blame and modifying them to reflect more realistic statements as in accepting her husband responsible for his own actions. Angela also began to realize that Adrian's suicide attempt was a selfish act insomuch that she was shouldering the responsibility of looking after her ailing father and son amidst financial strain. Yet, processing of the imaginal exposures often seemed counterproductive, with Angela often becoming “stuck,” going over the reasons Adrian did it or simply being upset rather than being able to integrate new or corrective information, for example, repeatedly stating, “I don't want to believe it … if I don't admit it, it's not true.”

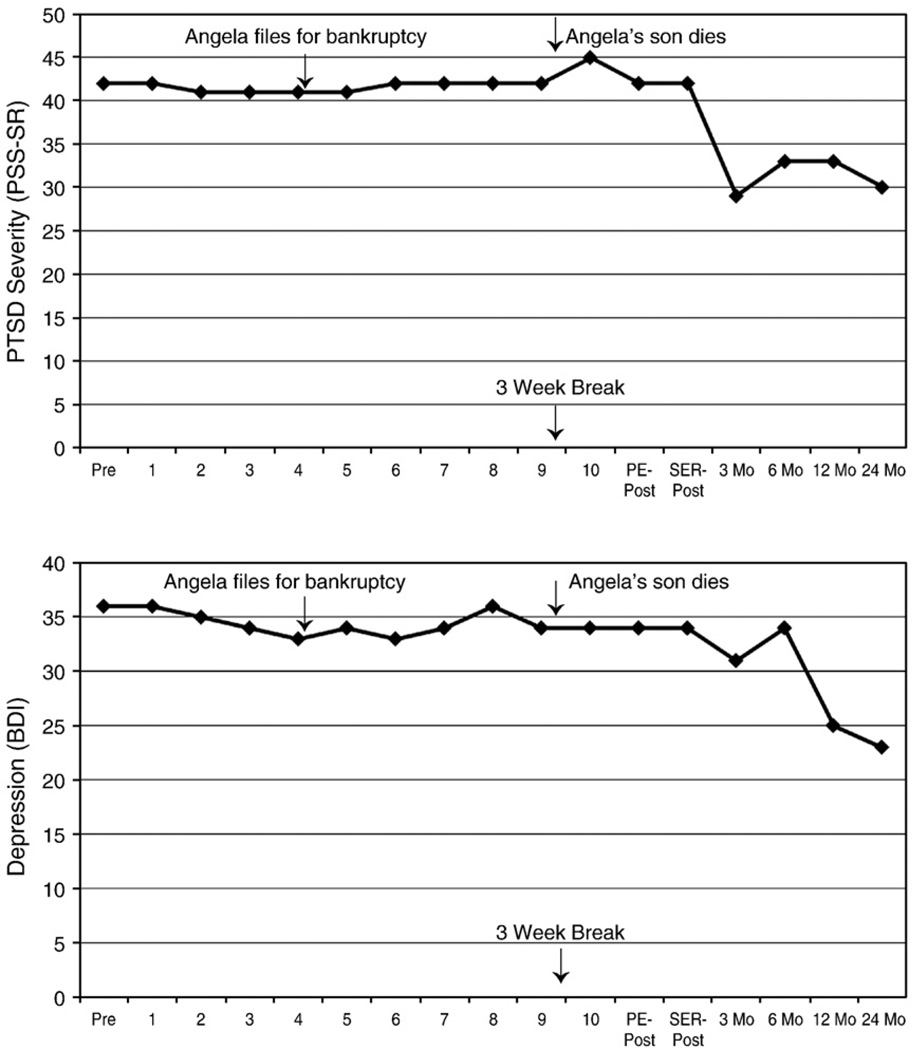

Although Angela was experiencing some moderate success with moving up her in vivo hierarchy in the areas of decreasing avoidance of Adrian's possessions and the basement, she had made little progress toward increasing her support outside of therapy. Related, she was reporting a high degree of stress in regard to her son's worsening leukemia, taking care of her father, and potentially filing for bankruptcy. These stressors competed for Angela's attention when there was very little to give from the onset. As a result, her life continued to be quite chaotic. In many respects, her therapy sessions were her only reprieve from the stress of caring for her ailing son and father. She was unable to take basic steps to increase support around these areas. At mid-treatment, neither her PTSD nor depression symptoms had shown any reduction (see in-session data in Fig. 1). Nevertheless, Angela and her therapist had developed a strong working alliance, and Angela remained thoroughly committed to therapy. Angela's in-session distress and frequent crying had also not abated. One of the most confusing aspects was initially deciding whether or not Angela's in-session distress and frequent crying were productive or counterproductive. Often the thoughts and emotions expressed were completely in line with the issues being addressed at the time. These thoughts tended to focus on why Adrian committed suicide: “I can't fathom why he did it. I can't let go of these questions.” It seemed like the second she sat down for each session, the floodgate of tears would open and her thoughts would run wild. This high level of affect in the room made it very difficult not only to manage time within the session, often not getting to things on the agenda or shortening them considerably, most notably during imaginal exposure, but also made it very difficult for Angela to listen and integrate important information during the session. For Angela, homework tapes of the sessions were very difficult and drew her focus not toward new learning but again dwelling on the past and her current suffering. Consistently seeing this response pattern, it became clear that her thoughts in session reflected more of a ruminative response style than successful emotional processing of aspects of the trauma. Over time, the persistence of the sobbing and lack of symptom improvement were clear markers that successful emotional processing was not occurring.

Figure 1.

Self-reported PTSD severity (PTSD Symptom Scale-Self-Report (PSS-SR; Foa, Cashman, Jaycox, & Perry, 1997) and depression (Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961) from pretreatment, Sessions 1–10, posttreatment following 10 sessions of PE, posttreatment following 10 weeks of sertraline (SER), to 2-year follow-up.

One hypothesis we had was that these rumination processes were functioning as a form of avoidance, both in terms of helping her avoid her own distressing feelings about her husband's suicide and also, on a more general level, of preventing an adequate amount of time and repetitions in the imaginal exposure and processing. Accordingly, we reviewed the rationale for exposure and discussed with Angela the role of avoidance of emotions about the trauma in maintaining PTSD and decreasing this avoidance as critical to the treatment. Specifically, we discussed how some of her thoughts perpetuate her rumination and act as barriers in processing his suicide. Angela became confused, saying that it feels like the suicide is the only thing she thinks about, so how could she be avoiding it. We discussed the difference between her thoughts about what Adrian was thinking before he committed suicide and her feelings over her loss. Even this discussion took up much of the session and left little time for imaginal exposure and processing. Thus, at subsequent sessions, we sought to increase the amount of time spent on exposure by starting earlier in the session.

These shifts made a brief impact in that Angela was able to address some of her unhelpful beliefs, particularly that she caused him to be depressed and kill himself. She realized that she had done a number of things to help Adrian and that he did not communicate to her that he was in crisis. She also began to explore her feelings of betrayal by him: “Who was this person?” “How many years did he lie to me? … This is not man that I married.” Rather than a ruminative examination of how and why Adrian committed suicide, this was the first sign of Angela confronting her feelings about his suicide. Despite these brief gains, in subsequent sessions, Angela again returned to rumination about why Adrian had taken his life and her own suffering. Angela's progress was also set back by her son's losing battle with cancer. Tragically, Angela's son died while she was in treatment with us. This led to her cancelling the next three sessions, thus delaying the final session.

Posttreatment and Follow-up

At posttreatment, the same interviewer, who was blind to the treatment Angela received, conducted the assessment. Angela's PTSD and depression symptoms had not improved (see Fig. 1). She was still reporting that her “mind automatically goes to” the suicide, replaying “the morning she found out” and her “interpretation of his last moments” over and over again in her head.

Because she did not respond to PE, Angela was offered free treatment with sertraline, under the direction of our staff psychiatrist. She was titrated up to 200 mg/day and remained on this dose through our follow-up assessments. Unfortunately, her PTSD symptoms and depression remained stable. We proposed to Angela that she explore outside referrals to address underlying ruminative processes and enhancing social support; finally, our psychiatrist informed her of medication augmentation strategies.

Contributing Factors in Lack of Improvement

When thinking of Angela's case, a number of factors combined together to contribute to the lack of improvement following both PE and sertraline, including inadequate exposure, strong in-session emotions, underlying ruminative processes, and ongoing stressors. Most notably, Angela may not have received an adequate “dose” of exposure, with the preponderance of treatment sessions focusing on addressing Angela's distress rather than planning and conducting in vivo and imaginal exposure. At times, only 20 minutes of a 2-hour session were devoted to imaginal exposure and, when exposure occurred, more often than not there was little or no true emotional engagement with the memory of the trauma. Thus, we do not know whether or not Angela would have improved if more optimal exposure had been given.

One of the key factors that made delivering more optimal exposure difficult was Angela's strong display of emotion and crying from the very start of almost every treatment session. As clinicians, we are often trained to follow the affect, feel the need to alleviate distress, and want to provide a warm and supportive environment for approaching traumatic memories. Thus, there is often a strong clinical pull to manage and address in-session affect. To further complicate the picture, the content of the therapeutic conversation surrounding this affect often mirrored clinically appropriate content, often focusing on why Adrian killed himself. Even in the context of imaginal exposure, Angela's high affective expression appeared on the surface to indicate emotional engagement with the trauma memory. Consequently, initially, there was the impression that Angela was working to engage with her feelings surrounding the suicide. In the early sessions, the only clues for the therapist that things were going amiss were somewhat higher-than-usual affect and the inability to appropriately manage time within the session. In the later sessions, upon awareness of an ongoing pattern, we conceptualized the intense crying as avoidance of more distressing thoughts and emotions associated with the trauma. We labeled it as such in session and returned to the treatment rationale that avoidance prevents emotional processing. We discussed with the client why crying was counterproductive and encouraged her to experience emotions other than sadness. Despite this, Angela was still unable to move beyond the tears in session and remained stuck.

Ultimately, we initially confused emotional engagement with an underlying ruminative process and did not identify that this was occurring quickly enough in the therapeutic process. Rumination in PTSD is not uncommon, particularly repetitive “Why?” or “Why me?” questions, and is actually an early predictor of the development and maintenance of chronic PTSD (e.g., Michael, Halligan, Clark, & Ehlers, 2007). As is often the case with rumination, Angela showed a repetitive focus on her own suffering and on understanding the cause of this suffering with contemplative questions focusing on why this happened to her and why she was still suffering, often with the same thoughts coming up each session. This inward focus not only served to perpetuate the severity and duration of her depression but also impaired her ability to process other information during therapy itself. This was most noticeable in Angela being fatigued by the intense affect even before starting imaginal exposure and consequently not having the necessary resources to either engage in the exposure or process it afterwards. Rumination may serve to maintain PTSD because abstract thinking leads to a persistence of negative mood and arousal (Ehring, Szeimies, & Schaffrick, 2009; Moore, Zoellner, & Mollenholt, 2008), which is consistent with our conceptualization of rumination as a form of avoidance for Angela.

Moderate to severe co-occurring depression is also very common (Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes & Nelson, 1995), so much so that some have considered PTSD more of a distress disorder akin to depression (e.g., Watson, 2005). One possibility, of course, is that we diagnosed her wrong and should have started with more depression-oriented treatment such as cognitive therapy (e.g., Teasdale, Fennell, Hibbert, & Amies, 1984), behavioral activation (e.g., Dimidjian et al., 2006), interpersonal psychotherapy (e.g., Elkin et al., 1989), or even a more rumination-focused intervention (e.g., McEvoy & Perini, 2009). Yet, given that the focus of her depression was on the traumatic event and her intrusions and ruminations centered on the suicide, clinically, it made sense to directly address the trauma.

These ruminative processes had a cascade effect on imaginal exposure, affecting the duration and lack of repetitions necessary for extinction, the content of the imaginal exposure itself, and finally her processing of the imaginal exposure. As discussed in emotional processing theory, therapeutically it is important to access underlying emotions and also integrate corrective information during exposure (Foa & Kozak, 1986). Yet, although Angela's trauma narrative showed strong affect, there was little content about what she was thinking or feeling in the narrative, and, even when the therapist probed for this, there was little change in this content. For example, when she described going down to the basement for the first time, she would often say, in the midst of sobs, “… and then I imagined him hanging there,” without any information about what she had visualized, what was going through her head, or the feelings she was experiencing at that time. To further complicate matters, if anything, the homework tapes of her imaginal exposures functionally served more as a cue to start ruminative processes rather than promote successful emotional processing. While she was incredibly compliant with listening to her tapes, Angela frequently reported having to stop the tape a number of times due to intense intrusive thoughts of his suicide, which we addressed in session as avoidance. Angela also showed little or no within- or between-session distress reduction on her homework. Most likely, the homework repetitions were not effective because the content of the imaginal exposure tapes was largely repeating for her the experience of her own distress rather than anything corrective or therapeutic. Thus, it would have been more beneficial to have Angela listen to only select portions of the imaginal exposure tape or listen to other sessions that did not include extended crying.

It may be, as well, that the reason we were not getting good content in the imaginal exposure was that we picked the wrong area of focus. Generally, we have a bias against having clients make up or elaborate on aspects of the trauma memory that they did not experience themselves, often having individuals skip or “fast forward” through parts that they do not know or remember. This is due to an underlying assumption that the fundamental nature of memory is reconstructive (i.e., why make up and reify something that is unknown) and that having a client imagine what might have happened is not necessary for accessing pathological fear schemas. In fact, making up something directly contradicts accepting that some things are going to remain unknown. This was the case for Angela; she was never going to know the reason why her husband committed suicide. Nevertheless, even in the midst of the therapy, we wondered if we made a mistake of not having her generate and process her images of what she thought her husband's last moments were like. She told us this on several occasions—most notably when we picked her trauma hot spot. This type of “imagined” imaginal exposure has been done successfully in the treatment of traumatic grief where often events are not directly experienced (Shear et al., 2005), is routinely done in other anxiety disorders such as obsessive-compulsive disorder where imaginal exposure occurs to unlikely, hypothetical consequences (see Foa & Kozak, 1986), and has been done successfully in the treatment of PTSD as well (E. Foa & L. Hembree, personal communication, September, 21, 2009). Alternatively, we could have incorporated more of what she imagined into the discussion of the processing after the imaginal exposure. In some ways, we may have missed directly going after the “monster in the room” for Angela and should have had her exposure focus on what she imagined her husband's last moments were like. It is possible that this shift may have facilitated emotional processing that we were not successful at obtaining solely by having her focus on her images at the time when she went down to the basement.

Even if these factors might have been remedied, Angela was going through an incredible amount of life stress during the course of therapy, including being the primary care provider for her ailing father, financial bankruptcy, and ultimately the death of her son from leukemia, with very little social support around her. Clearly, ongoing life stress perpetuates both PTSD and depression, as does a lack of social support (Brewin, Andrews, & Valentine, 2000; Cohen, Hammen, Henry, & Daley, 2004; Ozer, Best, Lipsey, & Weiss, 2003). Significant ongoing life stressors are common in individuals with PTSD (e.g., Kessler et al., 2005) and, in a brief protocol, are not the therapeutic focus as they can shift focus away from the trauma. With Angela, these stressors affected her ability to attend sessions regularly and also complete homework assignments aimed at supporting her during her stress. In some respects, this wasn't the time for focusing on the suicide of her husband; however, at the onset of therapy, neither the bankruptcy nor the death of her son was on the horizon. Therapy for Angela was the only place where she was able to “let her guard down.” Despite our best efforts, we were unable to help her connect with others outside of therapy for support. This is actually surprising in that she worked hard on her other in vivo homework tasks; yet, Angela reported feeling like she was just keeping her “head above the water” and didn't have the energy to reach out to others. Accordingly, probably one of the biggest functions of therapy for Angela was social support through this difficult time, helping her to function and have an outlet for her distress.

Finally, Angela was part of a clinical trial that shifted treatment after 10 sessions to sertraline if the therapy had not been effective. We are not sure that additional sessions of PE at the time would have been effective, though extending the number of sessions for nonresponders often affords a benefit for some patients (Foa et al., 2005). We doubt this extension would have been helpful unless we were better able to more effectively intervene with her ruminative thinking. The choice of shifting over to a serotonergic agent as a second-tier intervention is entirely appropriate (Davidson et al., 2001; Simon et al., 2008); and, given Angela's co-occurring major depression, ruminative processes, and ongoing stressors, it was reasonable to believe that she might have benefited substantially from the medication. This clinical trial allowed the clinical shift, with the psychotherapist continuing to be available for booster sessions if needed, but did not allow for combined PE and sertraline treatment. Even if combined treatment would have been available, at present, we still do not know if combined treatment for PTSD affords any additive benefit (see Foa, Franklin, & Moser, 2002). Further, given PE integrity issues, the trial did not allow the therapist to divert from protocol and directly target her rumination via teaching other therapeutic techniques. Given the death of her son, a continued focus on the suicide of her husband most likely would not have been the main therapeutic focus.

Research and Clinical Implications

Clinically, this case highlights the importance of repeated assessment and monitoring of symptoms and distress within and between sessions and the understanding of typical patterns of recovery. From previous research, we know patterns of fear extinction (see Jaycox, Morral, & Foa, 1998) and typical symptom recovery patterns during prolonged exposure (see Foa, Zoellner, Feeny, Hembree, & Alvarez-Conrad, 2002). These patterns can be important hallmarks from which therapists can judge their own clients' trajectory. Neither was Angela's fear diminishing within or between sessions, nor was there symptom reduction across sessions, where expected. If we hadn't been systematically monitoring these outcomes, we most likely would not have been alerted to problems and would not have tried to make therapeutic adjustments nearly as quickly. Yet, these are fairly gross indicators of therapeutic problems and, particularly in a time-limited treatment, knowledge of early indicators of potential treatment dropout or failure may help to mitigate these problems. At the present time, several studies (e.g., Blanchard et al., 2003; Taylor et al., 2001; van Minnen & Hagenaars, 2002) have shown that pretreatment symptom severity predicts poorer outcomes. Yet, this information has only limited clinical utility. In recent years, there has been a call for more psychotherapy process research, that is, identifying key processes of change during psychotherapy, as a key means to enhance our current psychotherapies (Weisz et al., 2000). This research is in its infancy in PTSD treatment. Understanding the shape of change and points of divergence between treatment responders and nonresponders can identify important transition points, revealing what therapists are doing to facilitate this transition and what is changing in patients (e.g., Laurenceau, Feldman, Strauss, & Cardaciotto, 2007).

At a basic process level, better understanding what are necessary and optimal parameters of imaginal exposure and subsequent processing of the exposure in PTSD may yield important clinical benefits. As recently suggested by Craske and colleagues (2008), “A major gap in the translation from basic science to clinical practice is theoretically driven research directly comparing different schedules of exposure trials” (p. 19). Quite simply, we do not know how long imaginal exposure needs to be conducted or how many sessions need to occur for individuals to benefit. For Angela, her brief (20–30 min) imaginal exposures and eight imaginal exposure sessions were not sufficient. A one-size-fits-all approach of the typical 45–60 min exposure duration over the course of 7 to 10 imaginal exposure sessions may be too much for some and too little for others. We are just starting to understand these parameters, with some preliminary evidence showing that not all patients need exposure at this duration (e.g., 30 min may suffice) or number of sessions (e.g., 3–5 sessions may be possible; Basoglu, Livanou, Salcioglu, 2003; van Minnen & Foa, 2006). Yet, even here, we do not know the vital question of who is most likely to benefit from longer or shorter length of exposure or number of treatment sessions.

The role of co-occurring depression itself is another process factor that warrants focus both as a potential moderator and mediator of treatment outcome in PTSD. The presence of MDD is not sufficient to abandon exposure therapy for chronic PTSD, and this case should not be interpreted as an example of how exposure therapy for co-occurring depression does not work. In PTSD, we know that depression frequently co-occurs (e.g., Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005; Kessler et al., 1995), depression improves with exposure therapy (e.g., Foa et al., 1999; Foa et al., 2005), and those with MDD may actually show larger effect sizes with this treatment than those without MDD (Feeny et al., 2009). Thus, for the majority of clients, depression co-occurring with PTSD is common, and both PTSD and depression symptoms will improve with prolonged exposure. Yet, the co-occurrence of PTSD and MDD is also associated with more functional impairment, higher severity of psychiatric medical illness, and lower quality of life than when PTSD or MDD occur in isolation (e.g., Campbell et al., 2007). There is no doubt that the severity of her co-occurring depression made therapy more difficult, most notably in the areas of rumination, in-session distress, and lack of social support.

Clinically, we initially had great difficulty in identifying Angela's ruminative processes. It is relatively common to see both intrusions and rumination in individuals with chronic PTSD (e.g., Michael et al., 2007; Reynolds & Brewin, 1999; Williams & Moulds, 2007). In Angela's case, she had cued and uncued thoughts and images of the trauma that would then trigger a circular pattern of rumination about understanding why her husband killed himself and her own suffering. Some of our difficulty may solely have been that this is something typically seen and usually abates on its own over time. Thus, we did not pay a lot of attention to it initially, until it persisted over the course of therapy. The other, more insidious issue was that, clinically, Angela's rumination resembled what we want in successful emotional processing insomuch that her emotive presentation indicated that she was emotionally connected with the memory and appeared to be trying to process and integrate it. The difference was that her process had a persistent quality that never led to any resolution for her. Very little research to date has been done in understanding perseverative cognitive processes in individuals with chronic PTSD, differentiating these processes from intrusions or examining a functional relationship between intrusions and ruminatory processes. Ultimately, identifying ruminative processes and interrupting these processes may have facilitated exposure. Specifically, it may have helped to place a greater emphasis on cultivating awareness of Angela's thought patterns so that she could catch herself when she began ruminating. This sort of “attention training” has been proposed as a useful tool for increasing attentional control and flexibility to reduce the negative impact of perseverative thought, such as rumination, on processing of new, more adaptive information (see McEvoy & Perini, 2009; Papageorgiou & Wells, 2003). That said, alternatively, if we had been able to process other aspects of Angela's experience aside from the exclusive focus on the sobbing, this may have also promoted attentional flexibility and reduced perseveration.

Angela also displayed a high level of in-session distress; frequently crying throughout the course of the sessions. In the treatment of chronic PTSD, the presence of distress itself is not necessarily anything out of the ordinary. In fact, higher levels of initial distress during exposure are more often associated with better treatment outcome (e.g., Foa, Riggs, & Gershuny, 1995; Jaycox et al., 1998) than not (Rauch, Foa, Furr, & Fillip, 2004; van Minnen & Hagenaars 2002). Pertinent to the case of Angela, Rauch et al. (2004) found that higher peak anxiety in subsequent sessions was related to higher posttreatment severity. Thus, again, it is the persistence that may be the marker of worse outcome rather than the presence itself. Clinically, high levels of client distress are difficult for therapists to ignore and yet may be counterproductive to attend to at the expense of therapeutic components of the treatment. When high levels of distress do not lessen over multiple sessions, the therapist may also feel helpless in his or her ability to reduce the client's distress, leading the therapist to devote more attention to the client's distress to “put out the fire” and to veer off of the treatment protocol to do this. Rather than allowing the client's strong emotional presentation to co-opt the therapy sessions, the therapist may need to assume a more active role in structuring the session, particularly early on in therapy. It also may be helpful to describe this pattern of attending to the distress at the expense of other therapy elements as a form of avoidance to the client in order to work together to address the problem. In Angela's case, one intervention was making sure to start imaginal exposure earlier rather than later in the session. Further, using her breathing skills or directly teaching distress tolerance skills (e.g., engaging in pleasurable activities) may have also been quite beneficial to her. Even then, it may be difficult for a therapist to push the client to engage more fully with the trauma memory when the client is already upset. Here, understanding the underlying theory can often help, providing good rubrics for when and how to promote engagement or titrate down the distress (see Foa et al., 2007).

Finally, Angela's case reminds us of the role of ongoing factors that may impact treatment: namely, other stressful events and lack of related social support. Often the lives of trauma survivors are chaotic and the therapist has to choose carefully, particularly with a limited number of sessions, which stressful events to attend to and which ones to not. Major events such as the death of a child need to be addressed and will influence the course of any therapy; others often pull the focus away from the trauma and derail the therapy unnecessarily. As seen with Angela, when conducting in vivo exposure with a patient who suffers from co-occurring depression, the therapist targets not only areas where the client is avoiding because of fear but also areas to increase activity and social support to help address loss of interest and detachment from others commonly seen in PTSD; this is akin to what is typically done in behavioral activation protocols (Jacobson, Martell, & Dimidjian, 2001). Although we know that ongoing life stressors and lack of support are some of the strongest predictors of the development of chronic PTSD (Brewin et al., 2000; Ozer et al., 2003), we know very little about how these factors impact the course of PTSD treatment. Further process research will yield important information about how these factors affect what goes on in sessions and ultimately how they affect dropout, recovery, and maintenance of therapeutic gains.

Summary and Future Directions

None of us likes it when our clients fail to improve over the course of therapy. They plague our thoughts and remain with us not only for the prolonged suffering of our client but also for the unanswered questions of “what if” that we will never be able to answer. We know in our heads that we will not be able to help everyone, but in our hearts that is our desire. Cases such as Angela's remind us of this; and yet, in many respects, these cases also have the potential to help future clients. This includes not only helping other individuals like Angela but also helping in treatment development and refinement.

In the treatment of chronic PTSD, we are fortunate to have a number of empirically supported treatment options that afford strong and durable treatment gains for many trauma survivors. Nevertheless, a number of patients drop out (e.g., 20.6%; Hembree et al., 2003); and, even among treatment completers, a number of patients continue to meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD (e.g., 35% of completers; Foa et al., 1999). Thus, there is clearly room for improvement. Angela helps us begin to do this, by informing not only our clinical work but also by informing areas of future research. We need to move beyond the “does it work” question to the broader question of “for whom and under what circumstances does it work.” Angela was stuck dwelling in her past, focusing on why the trauma happened and her own suffering. This ruminative style not only served to sustain her own distress but also had a cascade effect on the course of the therapy. Ultimately, she helps us to begin to understand the complicated relationship between PTSD and co-occurring depression and also helps point us to the intricate relationship between intrusive memories and related ruminative processes.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Afsoon Eftekhari, Ph.D., and Joshua McDavid, M.D., for their clinical insights and expertise in the treatment of this case. This manuscript was support by the following grants: R01MH066347 (PI: Zoellner) and F31MH084605 (PI: Echiverri).

Footnotes

Details about the case have been modified to protect the identity of the client.

References

- Basoglu M, Livanou M, Salcioglu E. A single session exposure treatment for traumatic stress in earthquake survivors with an earthquake simulator. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:788–790. doi: 10.1176/ajp.160.4.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Ward C, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:53–63. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard E, Hickling E, Malta L, Jaccard J, Devineni T, Veazey C, et al. Prediction of response to psychological treatment among motor vehicle accident survivors with PTSD. Behavior Therapy. 2003;34:351–363. [Google Scholar]

- Bouton M. Context and ambiguity in the extinction of emotional learning: Implications for exposure therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1988;26:137–149. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(88)90113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton M. Context and behavioral processes in extinction. Learning & Memory. 2004;11:485–494. doi: 10.1101/lm.78804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin C, Andrews B, Valentine J. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:748–766. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell D, Felker B, Liu C, Yano E, Kirchner J, Chan D, et al. Prevalence of depression-PTSD comorbidity: Implications for clinical practice guidelines and primary care-based interventions. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:711–718. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0101-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A, Hammen C, Henry R, Daley S. Effects of stress and social support on recurrence in bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;82:143–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske M, Kircanski K, Zelikowsky M, Mystkowski J, Chowdhury N, Baker A. Optimizing inhibitory learning during exposure therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46:5–27. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JR, Rothbaum BO, van der Kolk B, Sikes CR, Farfel GM. Multicenter, double blind comparison of sertraline and placebo in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:475–485. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimidjian S, Hollon S, Dobson K, Schmaling K, Kohlenberg R, Addis M, et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:658–670. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehring T, Szeimies A, Schaffrick C. An experimental analogue study into the role of abstract thinking in trauma-related rumination. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47:285–293. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkin I, Shea M, Wattkins J, Imber S, Sotsky S, Collins J, et al. NIMH treatment of depression collaborative research program: General effectiveness of treatments. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1989;46:971–983. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110013002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeny N, Zoellner L, Mavissakalian M, Roy-Byrne P. What would you choose? Sertraline or prolonged exposure in community and PTSD treatment seeking women. Depression & Anxiety. 2009;26:724–731. doi: 10.1002/da.20588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa E, Cashman L, Jaycox L, Perry K. The validation of a self-report measure of PTSD: The PTSD Diagnostic Scale. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:445–451. [Google Scholar]

- Foa E, Dancu C, Hembree E, Jaycox L, Meadows E, Street G. A comparison of exposure therapy, stress inoculation training and their combination for reducing PTSD in female assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:194–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa E, Franklin M, Moser J. Context in clinic: How well do cognitive-behavioral therapies and medications work in combination? Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52:987–997. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01552-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa E, Hembree E, Cahill S, Rauch S, Riggs D, Feeny N, et al. Randomized trial of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder with and without cognitive restructuring: Outcome at academic and community clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:953–964. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa E, Hembree E, Rothbaum B. Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: Emotional processing of traumatic experiences: Therapist guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Foa E, Kozak M. Emotional processing of fear: exposure to corrective information. Psychological Bulletin. 1986;99:20–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa E, Riggs D, Dancu C, Rothbaum B. Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1993;6:459–473. [Google Scholar]

- Foa E, Riggs D, Gershuny B. Arousal, numbing, and intrusion: Symptom structure of PTSD following assault. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:116–120. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa E, Rothbaum B, Riggs D, Murdock T. Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in rape victims: A comparison between cognitive-behavioral procedures and counseling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:715–723. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.5.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa E, Zoellner L, Feeny N, Hembree E, Alvarez-Conrad J. Is imaginal exposure related to an exacerbation of symptoms? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:1022–1028. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurological and Neurosurgical Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hembree E, Foa E, Dorfan N, Street G, Kowalski J, Xin T. Do patients drop out prematurely from exposure therapy for PTSD? Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16:555–562. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000004078.93012.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Treatment of PTSD: An assessment of the evidence. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N, Martell C, Dimidjian S. Behavioral activation treatment for depression: Returning to contextual roots. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice. 2001;8:255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Jaycox L, Morral A, Foa E. The influence of emotional engagement and habituation on outcome of exposure therapy for PTSD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:185–192. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas K, Walters E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Chiu W, Demler O, Walters E. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson C. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurenceau J, Feldman G, Strauss J, Cardaciotto L. Change is not always linear: The study of nonlinear and discontinuous patterns of change in psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:715–724. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy P, Perini S. Cognitive behavioral group therapy for social phobia with or without attention training: A controlled trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:519–528. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael T, Halligan S, Clark D, Ehlers A. Rumination in posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2007;24:307–317. doi: 10.1002/da.20228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore S, Zoellner L, Mollenholt N. Are expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal associated with stress-related symptoms? Behavior Research and Therapy. 2008;46:993–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer E, Best S, Lipsey T, Weiss D. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(1):52–73. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou C, Wells A. An empirical test of a clinical metacognitive model of rumination and depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27:261–273. [Google Scholar]

- Paunovic N, Ost L. Cognitive behavioral therapy vs. exposure therapy in treatment of PTSD in refugees. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2001;29:1183–1197. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachman S. Emotional processing. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1980;18:51–60. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(80)90069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch S, Foa E, Furr J, Fillip J. Imagery vividness and perceived anxious arousal in prolonged exposure treatment for PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17:461–465. doi: 10.1007/s10960-004-5794-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick P, Nishith P, Weaver T, Astin M, Feuer C. A comparison of cognitive processing therapy, prolonged exposure, and a waiting condition for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in female rape victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:867–879. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds M, Brewin C. Intrusive memories in depression and posttraumatic stress disorder. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1999;37:201–215. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum B, Astin M, Marsteller F. Prolonged Exposure versus Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) for PTSD rape victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:607–616. doi: 10.1002/jts.20069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr P, Friedman M, Engel C, Foa E, Shea M, Chow B, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in women: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;297:820–830. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear K, Frank E, Houck P, Reynolds C. Treatment of complicated grief: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:2601–2608. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon NM, Connor KM, Lang AJ, Rauch S, Krulewicz S, LeBeau RT, et al. Paroxetine CR augmentation for posttraumatic stress disorder refractory to prolonged exposure therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69:400–405. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID I): History, rationale, and description. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49:624–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Koch W, Fecteau G, Fedoroff I, Thordarson D, Nicki R. Posttraumatic stress disorder arising after road traffic collisions: Patterns of response to cognitive-behavioral therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;63:541–551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale J, Fennell M, Hibbert G, Amies P. Cognitive therapy for major depressive disorder in primary care. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1984;144:400–406. doi: 10.1192/bjp.144.4.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Minnen A, Foa E. The effect of imaginal exposure length on outcome of treatment for PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19:1–12. doi: 10.1002/jts.20146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Minnen A, Hagenaars M. Fear activation and habituation patterns as early process predictors of response to prolonged exposure treatment in PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2002;15:359–367. doi: 10.1023/A:1020177023209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D. Rethinking the mood and anxiety disorders: A quantitative hierarchical model for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:522–536. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman M, Paykel E. The depressed woman: A study of social relationships. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz J, Hawley K, Pilkonis P, Woody S, Follette W. Stressing the (other) three Rs in the search for empirically supported treatments: Review procedures, research quality, relevance to practice and the public interest. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2000;7:243–258. [Google Scholar]

- Williams A, Moulds M. An investigation of the cognitive and experiential features of intrusive memories in depression. Memory. 2007;15:912–920. doi: 10.1080/09658210701508369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]