Abstract

Approximately one-third of patients diagnosed with early stage colorectal cancer (CRC) will present with lymph node involvement (stage III) and about one-quarter with transmural bowel wall invasion but negative lymph nodes (stage II). Adjuvant chemotherapy targets micrometastatic disease to improve disease-free and overall survival. While beneficial for stage III patients, the role of adjuvant chemotherapy is unestablished in Stage II. This likely relates to the improved outcome of these patients, and the difficulties in developing studies with sufficient power to document benefit in this patient population. However, recent investigation also suggests that molecular differences may exist between stage II and III cancers and within stage II patients. Validated pathologic prognostic markers are useful at identifying stage II patients at high risk for recurrence for whom the benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy may be greater. Such high risk features include higher T stage (T4 versus T3), suboptimal lymph node retrieval, presence of lymphovascular invasion, bowel obstruction or bowel perforation, and poorly differentiated histology. However, for the majority of patients who do not carry any of these adverse features and are classified as “average risk” stage II patients, the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy remains unproven. Emerging understanding of the underlying biology of stage II colon cancer has identified molecular markers which may change this paradigm and improve our risk assessment and treatment choices for stage II disease. Assessment of microsatellite stability which serves as a marker for DNA mismatch repair system function has emerged as a useful tool for risk stratification of patients with Stage II CRC. Patients with high frequency of microsatellite instability (MSI-H) have been shown to have increased overall survival and limited benefit from 5FU based chemotherapy. Additional research is necessary to clearly define the most appropriate way to use this marker and others in routine clinical practice.

Introduction

Several studies have conclusively demonstrated the benefit of adjuvant infusional and bolus 5-FU plus oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) in patients with stage III colon cancer with improvement in disease free survival (DFS) to nearly 75% [1–7]. For stage II disease, where the typical patient with “average risk” has a 70–80% chance of cure with surgery alone, the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy remains controversial [8, 9]. The presence of traditional “high-risk” pathologic factors in stage II colon cancer can identify a subgroup of patients with a recurrence risk approximating stage III disease. Newer molecular markers can further define patient subsets with stage II disease that may benefit from adjuvant therapy. While discussing adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II colon cancer, we must consider both prognostic and predictive markers. Prognostic markers predict survival independent of treatment effect, while predictive markers predict benefit from a particular therapy. While prognostic markers have been validated in stage II disease, limited data exist for predictive markers.

Pathologic markers

T stage

The American Joint Committee of Cancer (AJCC) 7th edition staging manual classifies stage II tumors as T3 with invasion through the muscularis propria or into pericolic tissue, and T4 with invasion into adherent organs [10]. T4 tumors are subclassified into T4a (penetrating visceral peritoneum) and T4b (penetrating other organs/structures). A SEER database analysis supported the revised staging by demonstrating significant differences in 5 year relative survival rates between T3 and T4 tumors within stage II disease (T3N0 87.5%±0.4%; T4N0 71.5%±0.8%) and between T4a and T4b disease (T4a 79.6%±1%; T4b 58.4%± 1.3%) [11].

The prognostic significance of T stage was demonstrated by a pooled analysis of >3,000 stage II/III patients treated with surgery alone versus surgery plus adjuvant 5-FU based therapy [12]. A univariate analysis of prognostic factors for disease free survival (DFS) demonstrated a correlation between deeply penetrating tumors and inferior survival (hazard ratio (HR) of 1.21 for T3 and 1.81 for T4 tumors).

Early retrospective studies suggested a potential role for adjuvant external beam radiotherapy for T4 tumors with nodal involvement or penetrance into adjacent tissue [13–16]. Willett et al reported improved local control and recurrence free survival in patients with T4 tumors receiving adjuvant radiotherapy [17]. Based on these findings, Intergroup 0130 evaluated adjuvant radiotherapy (45–50.4 Gy) in T4 or T3 node positive tumors following adjuvant 5-FU chemotherapy [18]. Although closed early due to slow accrual, radiotherapy appeared to increase toxicity without improving DFS or OS. Although this study had limited power to detect meaningful differences, the routine use of radiotherapy is not recommended. For T4 tumors that extend to fixed structures such as the pelvic side wall, radiotherapy may still have a role.

Lymph Node Retrieval

An additional validated prognostic marker is the number of lymph nodes resected during curative surgery. Intergroup 0089 study was a large randomized controlled trial comparing three different 5FU based chemotherapy regimens for stage II and III CRC. A secondary analysis demonstrated a clear prognostic impact for retrieval of a greater number of lymph nodes in stage II and III colon cancer, with a greater effect in stage II disease [19, 20]. Among patients with node negative disease, OS and cancer specific survival (CSS) were improved with increased number of lymph nodes removed (p=0.005 and 0.007 respectively). A SEER database analysis demonstrated a strong correlation between increasing number of examined lymph nodes and improved survival, particularly for T3 tumors. These observations resulted in broad adoption of a minimum of 12 examined lymph nodes for proper staging of colon cancer [19, 21–27]. Bilimoria et al. evaluated the rate of adequate lymph node retrieval among stage II colon cancer patients [28]. More lymph nodes were removed during right versus left colectomies and in high versus low volume centers. A recent analysis confirmed higher percentages of adequate lymph node retrieval in NCCN centers versus SEER database centers (92 versus 58%) [29]. This prognostic marker can be improved with greater awareness by surgeons and pathologists. Our group demonstrated increased lymph node retrieval in a large community cancer network following a targeted educational initiative [30].

Additional high-risk pathologic features

Other pathologic factors associated with increased risk of recurrence in stage II disease include lymphatic and/or vascular invasion, poorly differentiated histology, and evidence of obstruction and/or perforation at presentation [12, 31–33]. Most of these factors were analyzed in series combining stage II and III tumors with the aim to draw conclusions regarding their prognostic role. Gill et al. identified histologic grade (high versus low) as an independent prognostic marker associated with worse DFS (HR=1.34; p=0.0017) [12]. An important cautionary note is that tumors with high microsatellite instability may frequently demonstrate a high grade phenotype and would be considered low risk.

The prognostic significance of bowel obstruction was demonstrated in a pooled analysis of over 1,000 patients from two NSABP studies [33]. Patients presenting with bowel obstruction had shorter DFS (p=0.0007), with the highest incidence of bowel obstruction noted for descending colon tumors (21%). This impact was maintained when controlling for nodal involvement, age, sex, and tumor location.

Lymphatic and/or vascular invasion have been shown to correlate with increased incidence of nodal involvement and liver metastases and thus are included as a high risk feature of stage II tumors [34–38]. Ouchi and colleagues reported an increasing incidence of vascular invasion when comparing tumor samples from patients with early stage tumors, metachronous liver metastases, and synchronous liver metastases (15.4%, 75%, and 89.5%, respectively; p<0.001) [35]. Wasif et al. reported occult nodal involvement by cytokeratin stain in 23.4% of early stage colon cancers, which correlated with high histologic grade (p=0.022) and lymphovascular invasion (p<0.001) [39]. All these studies point out the high risk of lymph node involvement and development of distant metastases for tumors with lymphovascular invasion. Patients with tumors with this characteristic should be considered for adjuvant therapy.

In general, traditional pathologic features such as T4 tumors, obstruction, perforation, high grade histology, and lymphovascular invasion are poor prognostic features. However, they cannot predict for chemotherapy benefit. Molecular markers may ultimately provide prognostic and predictive information.

Molecular markers

Increasing understanding of colon cancer biology has identified potential molecular markers to risk-stratify early stage colon cancer patients. This may be most useful for patients with stage II colon cancer where adjuvant chemotherapy is debated. However, tests utilizing immunohistochemistry or gene expression analysis are costly. In addition, proper validation of markers, techniques, and cutoff values is critical.

Microsatellite instability

Microsatellites are short, tandemly repeated DNA sequences present throughout the genome. They are easily susceptible to errors of DNA replication, particularly in the presence of a defective mismatch repair (MMR) system. Thus, microsatellite stability can serve as a surrogate for normally functioning DNA MMR. In colon cancer, mutations in the MMR system lead to a high frequency of microsatellite instability (MSI). Inherited germ line mutations in MMR and the presence of MSI are found in approximately 50% of patients with a family history that fulfills the Amsterdam criteria [40–46]. These defects result most commonly from alterations of the MLH1, MSH2 or MSH6 mismatch repair genes [43, 45, 47, 48]. Loss of MLH1 expression due to methylation of its promoter has also been described in up to 15% of sporadic colon cancer [49, 50].

Tumors are classified according to the percentage of abnormal microsatellite regions present as MSI-high (MSI-H) (>30–40%), MSI-low (<30–40%) or microsatellite stable (MSS – no abnormalities) [51]. MSI-H status is present in 22% of stage II and 12% of stage III colon cancers and associated with younger age, higher T stage, lower N stage, right-sided lesions, and poorly differentiated histology [51–54]. Testing for microsatellite instability as a marker for MMR can be performed at the gene level (gold standard) or the protein level using immunohistochemistry (IHC). At the protein level, IHC is typically performed for the most common protein alterations hMLH1 and hMSH2 and due to its low cost and rapidity of the results is the recommended initial screening test [53, 55–57].

The improved prognosis of patients with MSI-H tumors was initially demonstrated by Gryfe et al [41]. Ribic et al subsequently reported improved 5 year survival among patients with stage II/III colon cancer and MSI-H tumors compared to MSI-low/MSS tumors (HR for death 0.31, p=0.004)[58]. In a multivariate analysis, MSI-H tumors were associated with improved OS (HR for death 0.61, p=0.03). Similar findings were later reported in a pooled analysis of over 7,000 early stage colon cancer patients treated with adjuvant 5-FU (HR for OS 0.65) [59]. This survival benefit was similar for stage II and III tumors and independent of treatment setting. Data from the PETACC III, EORTC 40993, and SAKK 60-00 studies similarly demonstrated improved recurrence free survival (RFS) and OS among patients with MSI-H compared with MSS tumors (HR for OS 0.45, p=0.0003). A subgroup analysis revealed a stronger effect among stage II patients (RFS: HR=0.26, p=0.004; OS:HR= 0.153, p= 0.009) compared with stage III patients (RFS: HR= 0.69, p= 0.06; OS: HR= 0.674, p= 0.09)[52, 60]. Similar observations of improved outcome among patients with MSI-H tumors regardless of other pathologic markers have been reported [41, 58, 61].

While stage II patients with MSI-H tumors have improved outcome, the role of MSI as a predictive marker is less clear. Popat et al. reported a lack of benefit from adjuvant 5-FU among patients with MSI-H tumors (HR for OS 1.24) [59]. In the analysis by Ribic et al., patients with MSI-H tumors did not benefit from adjuvant 5-FU (HR for death 2.17, p=0.10) while those with MSI-low/MSS tumors did (HR for death 0.69, p=0.02). Sargent et al. similarly reported a DFS and OS benefit for adjuvant 5-FU for patients with proficient MMR (OS: HR=0.69, p=0.047; DFS: HR=0.59, p=0.004) but not deficient MMR (OS: HR=1.26, p=0.68; DFS: HR=1.41, p=0.53) in a pooled analysis of 341 tumors from intergroup trials [62]. In vitro models also demonstrate resistance to 5-FU in MSI-H tumor samples [63, 64]. In contrast, a retrospective analysis of NSABP trials did not identify any interaction between MSI status and adjuvant chemotherapy benefit, suggesting biology rather than therapy might define outcome [65]. MSI status has also been examined as a predictor of irinotecan adjuvant therapy in stage 3 patients, with conflicting results [52, 66].

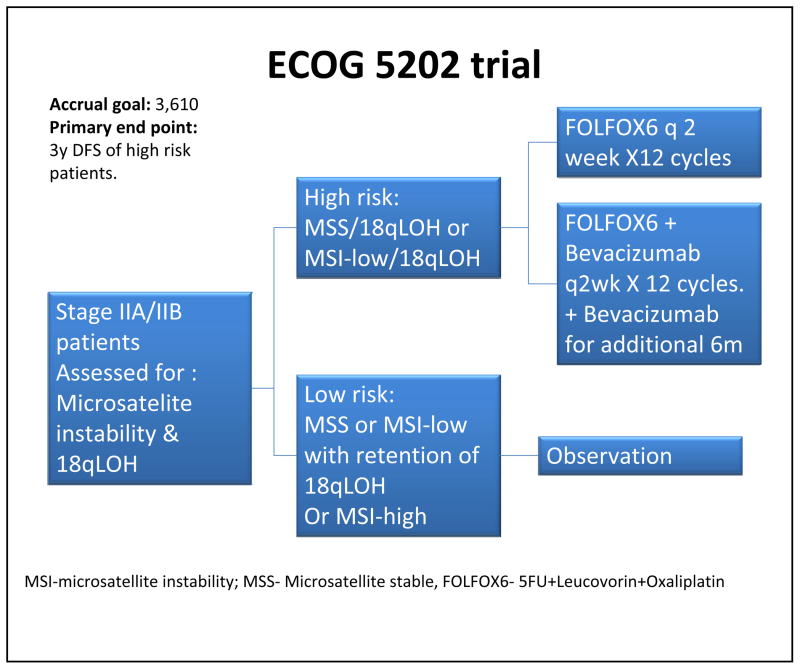

In summary, MSI status can be used in the clinic as a prognostic tool to identify a subgroup of stage II patients with improved prognosis. ECOG 5202 was a recently closed study that may provide prospective validation of MSI as a prognostic marker (Figure 1). Patients with stage 2 colon cancer underwent MSI and 18q LOH evaluation (see below) and were classified into low or high risk. High risk patients were randomized to FOLFOX or FOLFOX plus bevacizumab while low risk patients were observed. Although this design limits any predictive evaluation of MSI, the prognostic impact of MSI-H status can be assessed. However, recent reports demonstrating no benefit for the addition of bevacizumab to FOLFOX adjuvant treatment forced premature closure of ECOG 5202 [67–70]. Regarding the predictive impact of MSI status, the NCCN guidelines were recently updated to recommend MSI testing for patients with stage II colon cancer if considering fluoropyrimidine therapy only [26]. Based on the above data, patients with MSI-H stage II colon cancer without any additional high risk features would fall into the “low risk” category and may be observed without any chemotherapy. Patients with MSI-H tumors but with traditional high-risk pathologic features (i.e. lymphovascular invasion) represent a challenging subset without a clear standard of care.

Figure 1. Schema of ECOG 5202.

18qLOH – 18q Loss of heterozygosity

Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of chromosome 18 is another molecular event which can risk stratify patients with early stage colon cancer. The 18q loci contains several genes with roles in apoptosis and carcinogenesis which may be affected by LOH: DCC (Deleted in Colon Cancer), Smad4, Smad2, and Smad7 [51, 60, 71–73]. Watanabe and colleagues found 18qLOH in 49% of high risk stage II and stage III CRC samples, with significantly shorter DFS and OS compared to retained 18q (DFS 44% versus 64%, p=0.002; OS 50% versus 69%, p=0.005) [71]. Among patients with MSS tumors, 18qLOH conferred the worst prognosis. Jen et al. similarly found significantly worse 5 year survival among stage II/III patients with 18qLOH compared to those with normal chromosome 18 (HR: 2.83; p=0.008) [74]. Similar findings for a deleterious impact of 18qLOH on overall survival were reported in a large meta-analysis of 27 studies comprising over 2,000 patients with stage I-IV disease (HR=2.0) and numerous other studies [74–81].

A stage specific analysis of the PETACC 3-EORTC 40993-SAKK 60-00 trial found 18qLOH to be of greater prognostic significance in stage II compared to stage III patients and suggested Smad4 as a potential independent prognostic marker [60]. The frequency of 18q alterations among stage II and III patients was 63% and 70% respectively (p=0.04). Alazzouzi et al. examined early stage colon cancer samples for IHC expression and mutation analysis of Smad4 [82]. Tumors with high expression of Smad4 had improved OS (p<0.025) and DFS (p<0.013) compared to low-expressing tumors. Low Smad4 expression among patients receiving 5-FU based adjuvant chemotherapy was also associated with a shorter median survival (1.4 years versus >9 years) [83]. Similar reports are available from a small series by Boulay and colleagues linking Smad7 overexpression to inferior outcomes (OS HR=2.1, p=0.02) [84].

Data evaluating the predictive role of 18qLOH are limited. The analysis by Watanabe et al included 460 patients with stage III and high risk stage II colon cancer treated with adjuvant 5-FU based chemotherapy [71]. However, the lack of a control group and the small number of stage II patients limits predictive conclusions. In the UK AXIS trial, in which patients with early stage colon cancer were randomized between adjuvant 5FU via portal vein infusion and observation, tumor samples were analyzed for 18qLOH [85]. This analysis tested 18qLOH at two loci: D18S61 and D18S851. While patients with LOH at both loci or at the D18S61 locus had limited benefit from adjuvant therapy, LOH at the D18S851 locus did not influence treatment outcome [85]. This study emphasizes the need for better understanding of the significance of 18qLOH at the various loci.

Gene expression profiling

Gene expression profiling was pioneered in breast cancer, where the commercial assay Oncotype DX ® serves as a prognostic and predictive tool for patients with early stage node negative estrogen receptor positive breast cancer [86–88]. The initial analysis in colon cancer was performed by Wang and colleagues who analyzed RNA transcripts from 74 patients with stage II colon cancer and identified a 23-gene signature with 72% sensitivity and 83% specificity to predict recurrence. A scale was developed where patients with a high risk score had a 13-fold increased risk of recurrence within 3 years compared to those with a low risk score [89]. Barrier et al. reported on a 30 gene prognostic set in stage II colon cancer with 85.1% sensitivity and 67.5% specificity for recurrence prediction [90].

The most extensive evaluation of this technique was done by O’Connell et al. on 1,851 stage II/III tumor samples obtained from patients enrolled on NSABP studies (C01, C02, C04, C06) and the Cleveland Clinic [91]. The group developed a recurrence scale classifying patients into low, intermediate, and high recurrence risk and a treatment score predicting response to adjuvant 5-FU chemotherapy. The use of paraffin embedded tissue rather than fresh frozen tissue makes it easier to incorporate this assay into clinical practice. Kerr and colleagues performed an independent clinical validation of this scale in stage II colon cancer patients enrolled into the QUASAR trial where patients were randomized to receive 5FU or observation after surgical resection. The recurrence score (RS) was a strong predictor of recurrence risk (p=0.004), shorter DFS (p=0.01) and OS (p=0.04),with a linear correlation between risk of recurrence and increasing RS [92]. In a multivariate analysis, RS retained its prognostic significance (p=0.008). T stage (p=0.005) and MSI status (p<0.001) were two other independent prognostic markers identified in this analysis. In contrast, the treatment score did not predict for benefit from 5-FU (p=0.19). The reported risk of recurrence was 12% at 3 years for the low RS patients, 18% for the intermediate RS patients, and 22% for the high RS patients. Given that the cure rate for stage II patients is commonly cited as 70–80%, the clinical utility of a RS with cure ranges from 78–88% is unclear. Furthermore, since MSI and T stage were identified as independent prognostic makers, this assay may be of greater utility for patients with uninformative T stage or MSI status. Gene expression profiling is not currently recommended for routine use [26].

Guanylyl Cyclase C (GCC)

Expression of guanylyl cyclase C (GCC) in resected lymph nodes is under investigation as another prognostic marker. GCC is an interstitial tumor suppressor which is selectively expressed in normal intestinal epithelium and overexpressed in malignant gastrointestinal cells [93]. Dysregulation of GCC promotes tumorigenesis. A recent study evaluated 257 samples from patients with resected N0 colon cancer and demonstrated that the presence of GCC messenger RNA in lymph nodes was an independent negative prognostic marker (HR for recurrence= 4.66, p=0.04; HR for DFS=3.27, p=0.03) [94]. However, this initial study found GCC expression in the majority of resected lymph nodes, a fact clearly at odds with the known risk of recurrence in this patient population. Further studies are ongoing.

Selecting therapy for stage II colon cancer – practical considerations

Addition of oxaliplatin

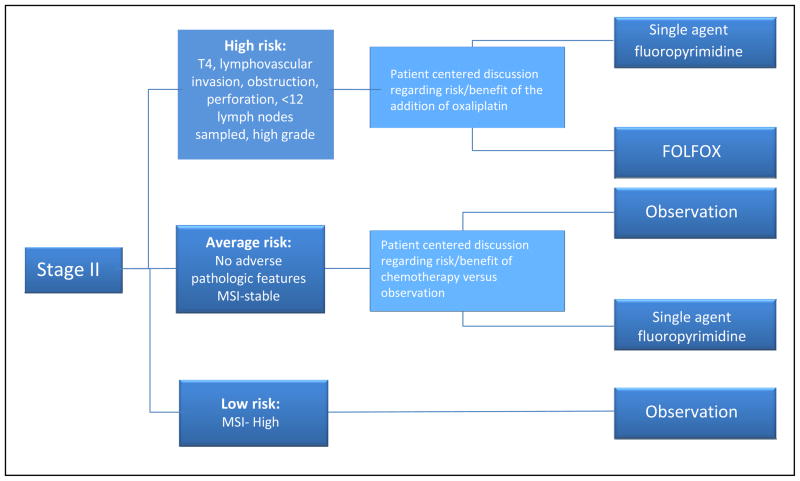

While the role of adjuvant combination chemotherapy is well established in stage III colon cancer, the benefit in stage II patients remains controversial. The MOSAIC study demonstrated improved DFS and OS for stage III patients treated with FOLFOX compared with those treated with 5FU alone (DFS HR=0.80, P = 0.003; OS HR = 0.84, P = .046 for OS), and established FOLFOX as the current standard of care for adjuvant treatment of stage III [4]. No improvement in DFS or OS was noted in 899 patients with stage II disease (DFS HR=0.84, p= 0.258; OS HR=1.00, p=0.986). A trend toward improved outcome with oxaliplatin was noted among high risk stage II patients with T4 tumors, bowel obstruction, poorly differentiated tumors, venous invasion, or less than 10 examined lymph nodes (DFS HR=0.72; OS HR=0.91, P =0.648). A 6 year update of MOSAIC stratified patients with stage II disease into high risk (T4 or <12 lymph node examined, n=503) and low risk categories (n=396) and reported no benefit for FOLFOX in the low risk group [95]. Among high risk patients the HR for DFS was 0.76 (95% CI- 0.49–1.06) and for OS 0.81 (95%: 0.52–1.26). NSABP C-07 randomized stage II/III patients to either receive bolus 5-FU/LV alone or with oxaliplatin. Similar to the MOSAIC trial, while a clear benefit for the addition of oxaliplatin was noted in stage III patients, no benefit was noted in stage II. [7]. It is clear from these data that “average risk” stage II patients (without any high risk features) do not derive additional benefit from adding oxaliplatin to 5-FU. For “high risk” stage II patients (T4 tumors, presence of lymphovascular invasion, obstruction, perforation, or limited lymph node retrieval) it is reasonable to consider FOLFOX in the adjuvant setting due to the strong trend demonstrated in the above studies (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Treatment algorithm for patients with stage II colon cancer.

5FU/LV-5 - fluorouracil and leucovorin; FOLFOX- 5FU, leucovorin and oxaliplatin; MSI – microsatellite instability; 18qLOH – loss of heterozygosity of chromosome 18q.

Single agent fluoropyrimidine vs. no treatment

Whether or not fluoropyrimidine monotherapy improves outcome in “average-risk” stage II colon cancer remains unproven. The QUASAR study was the largest study to evaluate the role of adjuvant 5-FU compared with observation alone in 2,963 stage II patients with colon and rectal cancer (71% and 29% respectively). Adjuvant 5-FU decreased the risk of recurrence compared to observation alone (relative risk (RR) for colon cancer=0.78, p=0.004; RR for rectal cancer =0.68, p=0.004) [96]. The relative risk of death from any cause was improved for treated patients with stage II colon cancer (0.84; p=0·046), which translated into an absolute survival improvement of 3.6%. Other studies evaluating 5-FU based therapy in stage II colon cancer have had smaller sample sizes, necessitating sub-group analyses with limited power (Table 2) [4, 5, 11, 83–85]. Thus, meta-analyses have been conducted [4, 15, 86, 87]. The IMPACT B2 analysis pooled 5 randomized clinical trials evaluating 5-FU based therapy to observation in the adjuvant setting [1]. The analysis included 1,016 stage II patients followed for a median of 5.75 years. No significant improvement in event free survival (EFS) (HR=0.83, 90%CI 0.72 to 1.07) or OS (HR=0.86, 90% CI 0.68 to 1.07) was noted in treated patients compared with controls. Similarly, the Cochrane Collaboration analysis evaluated 18 studies comparing various adjuvant chemotherapy regimens to observation in over 8,000 patients with stage II colon cancer and detected no survival improvement with treatment (HR=0.96; 95% CI 0.87–1.05) but a small improvement in DFS (HR of 0.83, 95% CI: 0.75–0.91) [97].

Average-Risk Patients

For patients without any high-risk pathologic features (i.e. T4 tumors, lymphovascular invasion, obstruction, perforation, <12 lymph nodes examined), observation or single agent fluoropyrimidine is appropriate. Oxaliplatin only increases toxicity in this patient population and is not recommended [26]. The survival benefit of single agent fluoropyrimidine in this setting is at most 5%. A sample size of over 9,000 patients would be required to reliably detect this difference in a clinical trial [98]. Physicians should discuss with patients disease natural history, life expectancy, and benefit from adjuvant therapy (Figure 2).

MSI-H tumors

Current data support avoiding adjuvant chemotherapy in stage II patients with MSI-H tumors without high risk pathologic features. No data exist regarding the role of FOLFOX in this patient population, and conflicting data exist regarding the utility of irinotecan. Further study is warranted. Whether or not to recommend adjuvant therapy for stage II patients with MSI-H tumors and other high-risk features (i.e. lymphovascular invasion) remains a subject of debate.

The elderly

Despite a median age of 71 for colon cancer, the elderly are underrepresented in clinical trials [99]. Schrag et al performed a SEER database pooled analysis of 3,151 Medicare stage II colon cancer patients (aged 65–75) [9]. There was no difference in five year survival between treated and untreated patients (78% versus 75% respectively). A subgroup analysis by age of the QUASAR study included approximately 20% of patients (663) 70 years and older and did not show any decreased recurrence rate with adjuvant chemotherapy in this group (HR=1.13) [96]. The ACCENT database included patient information from six international adjuvant chemotherapy trials combining 5FU with oxaliplatin or irinotecan. A pooled analysis also did not demonstrate any benefit for adjuvant chemotherapy in older individuals (HR for OS: 1.14; HR for DFS: 1.11) [100]. A similar trend was noted in the MOSAIC study which reported limited benefit from adjuvant FOLFOX in patients >65 years of age with stage II and III colon cancer [4, 101]. In contrast, in a pooled analysis of over 3,000 stage II/III, Sargent et al. noted similar benefit in elderly patients and the group as a whole without significant differences in toxicity [102]. Similar findings were later reported by Fata and colleagues [103].

Treatment decision-making for elderly patients with stage II colon cancer must be individualized with careful attention to the patient’s functional status, life expectancy and risk of treatment related morbidity. It is clear that combination chemotherapy provides less benefit in this group of patients, although for the fit elderly with reasonable life expectancy, combination therapy could be considered.

Summary

Adjuvant therapy for stage II colon cancer remains a topic of debate, primarily for “average-risk” patients without clear pathologic risk factors. As our knowledge of underlying biology expands, molecular markers will play a more prominent role in our decision-making. To date, MSI-H status has emerged as the marker most closely linked to improved outcome and limited benefit from adjuvant fluoropyrimidine therapy. Much work still remains to be done to improve our ability to risk-stratify patients and improve outcomes while limiting toxicity. Ongoing prospective studies and enhanced participation in clinical trials is critical for continued progress in this field.

Table 1.

Major prospective studies and meta-analyses evaluating 5-FU based adjuvant therapy for stage II colon cancer

| Study | Number of patients with stage II colon | Treatments | Recurrence | Overall survival (OS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quasar [96] | 2963 | 5FU/leucovorin observation | RR for recurrence of colon = 0.78 (p=0.004)* RR for recurrence of rectal =0.68 (p=0.004)* |

RR for death for colon cancer=0.84 (0.046) RR for death for rectal cancer=0.77 (p=0.05) |

| NCCTG (1989)[104] | 36 35 33 |

Surgery alone (control) Levamisole alone 5FU+Levamisole |

Control vs Levamisole: p=0.43 Control vs. Levamisole +5FU: p=0.26 |

Control vs Levamisole: p=0.43 Control vs. Levamisole +5FU:p=0.26 |

| INT-0035[8] | 159 159 |

Observation 5FU+Levamisole |

RR for recurrence=0.69 (p=0.10) | No significant difference |

| NACCP (2001)[105] | 235 233 |

Observation 5FU+Levamisole |

RFS=65% RFS=71% |

OS=70% OS=78% |

| Francini et al. [106] | 60 59 |

Observation 5FU+folic acid |

DFS=77% DFS=83% |

OS=86% OS=89% |

| Glimelius et al**. [107] | 1135 | Observation 5FU±folic acid±Levamisole |

No difference | No difference |

| IMPACT B2** [1] | 509 507 |

Observation 5FU+Leucovorin |

EFS=73% EFS=76% |

OS=80% OS=82% |

| Cochrane Review** [97] | 8,642 | Observation Adjuvant chemotherapy | Relative risk for recurrence=0.83 | Relative risk= 0.96 |

achieving statistical significance p<0.05.

Meta-analyses.

RR-relative risk; 5FU- 5 fluorouracil; RFS- recurrence free survival; EFS- event free survival; OS- overall survival.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Efrat Dotan, Department of medical oncology, Fox Chase Cancer Center.

Steven J. Cohen, Gastrointestinal Medical Oncology, Fox Chase Cancer Center.

References

- 1.Efficacy of adjuvant fluorouracil and folinic acid in B2 colon cancer. International Multicentre Pooled Analysis of B2 Colon Cancer Trials (IMPACT B2) Investigators. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(5):1356–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Connell MJ, et al. Controlled trial of fluorouracil and low-dose leucovorin given for 6 months as postoperative adjuvant therapy for colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(1):246–50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.1.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolmark N, et al. Clinical trial to assess the relative efficacy of fluorouracil and leucovorin, fluorouracil and levamisole, and fluorouracil, leucovorin, and levamisole in patients with Dukes’ B and C carcinoma of the colon: results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project C-04. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(11):3553–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.11.3553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andre T, et al. Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(19):3109–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engstrom PF, Benson AB, 3rd, Saltz L. Colon cancer. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2003;1(1):40–53. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2003.0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haller DG, et al. Phase III study of fluorouracil, leucovorin, and levamisole in highrisk stage II and III colon cancer: final report of Intergroup 0089. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(34):8671–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.5686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuebler JP, et al. Oxaliplatin combined with weekly bolus fluorouracil and leucovorin as surgical adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II and III colon cancer: results from NSABP C-07. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(16):2198–204. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moertel CG, et al. Intergroup study of fluorouracil plus levamisole as adjuvant therapy for stage II/Dukes’ B2 colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(12):2936–43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.12.2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schrag D, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy use for Medicare beneficiaries with stage II colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(19):3999–4005. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Joint Committee on Cancer, C., IL. AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook. AJCC Cancer staging Manual. (7) 2010

- 11.Gunderson LL, et al. Revised TN categorization for colon cancer based on national survival outcomes data. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):264–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.0952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill S, et al. Pooled analysis of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy for stage II and III colon cancer: who benefits and by how much? J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(10):1797–806. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duttenhaver JR, et al. Adjuvant postoperative radiation therapy in the management of adenocarcinoma of the colon. Cancer. 1986;57(5):955–63. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860301)57:5<955::aid-cncr2820570514>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amos EH, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy for locally advanced colon cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 1996;3(5):431–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02305760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kopelson G. Adjuvant postoperative radiation therapy for colorectal carcinoma above the peritoneal reflection. I. Sigmoid colon. Cancer. 1983;51(9):1593–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830501)51:9<1593::aid-cncr2820510907>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kopelson G. Adjuvant postoperative radiation therapy for colorectal carcinoma above the peritoneal reflection. II. Antimesenteric wall ascending and descending colon and cecum. Cancer. 1983;52(4):633–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830815)52:4<633::aid-cncr2820520410>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willett CG, et al. Postoperative radiation therapy for high-risk colon carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(6):1112–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.6.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martenson JA, Jr, et al. Phase III study of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy compared with chemotherapy alone in the surgical adjuvant treatment of colon cancer: results of intergroup protocol 0130. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(16):3277–83. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berger AC, et al. Colon cancer survival is associated with decreasing ratio of metastatic to examined lymph nodes. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(34):8706–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.8852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Voyer TE, et al. Colon cancer survival is associated with increasing number of lymph nodes analyzed: a secondary survey of intergroup trial INT-0089. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(15):2912–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong JH, et al. Number of nodes examined and staging accuracy in colorectal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(9):2896–900. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tepper JE, et al. Impact of number of nodes retrieved on outcome in patients with rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(1):157–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leibl S, Tsybrovskyy O, Denk H. How many lymph nodes are necessary to stage early and advanced adenocarcinoma of the sigmoid colon and upper rectum? Virchows Arch. 2003;443(2):133–8. doi: 10.1007/s00428-003-0858-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Law CH, et al. Impact of lymph node retrieval and pathological ultra-staging on the prognosis of stage II colon cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2003;84(3):120–6. doi: 10.1002/jso.10309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joseph NE, et al. Accuracy of determining nodal negativity in colorectal cancer on the basis of the number of nodes retrieved on resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10(3):213–8. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engstrom PF, et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: colon cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7(8):778–831. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Compton CC, Greene FL. The staging of colorectal cancer: 2004 and beyond. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54(6):295–308. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.6.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bilimoria KY, et al. Impact of tumor location on nodal evaluation for colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(2):154–61. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajput A, et al. Meeting the 12 lymph node (LN) benchmark in colon cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102(1):3–9. doi: 10.1002/jso.21532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curley B, et al. Assessing the impact of a targeted educational initiative on colorectal cancer lymph node retrieval: A Fox Chase Cancer Center Partners’ quality initiative. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(supple; abstr 6524):15s.

- 31.Newland RC, et al. Pathologic determinants of survival associated with colorectal cancer with lymph node metastases. A multivariate analysis of 579 patients. Cancer. 1994;73(8):2076–82. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940415)73:8<2076::aid-cncr2820730811>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Compton CC, et al. Prognostic factors in colorectal cancer. College of American Pathologists Consensus Statement 1999. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124(7):979–94. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-0979-PFICC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolmark N, et al. The prognostic significance of tumor location and bowel obstruction in Dukes B and C colorectal cancer. Findings from the NSABP clinical trials. Ann Surg. 1983;198(6):743–52. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198312000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brodsky JT, et al. Variables correlated with the risk of lymph node metastasis in early rectal cancer. Cancer. 1992;69(2):322–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920115)69:2<322::aid-cncr2820690208>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ouchi K, et al. Histologic features and clinical significance of venous invasion in colorectal carcinoma with hepatic metastasis. Cancer. 1996;78(11):2313–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19961201)78:11<2313::aid-cncr7>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Talbot IC, et al. Invasion of veins by carcinoma of rectum: method of detection, histological features and significance. Histopathology. 1981;5(2):141–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1981.tb01774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Minsky BD, et al. Resectable adenocarcinoma of the rectosigmoid and rectum. II. The influence of blood vessel invasion. Cancer. 1988;61(7):1417–24. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880401)61:7<1417::aid-cncr2820610723>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horn A, Dahl O, Morild I. Venous and neural invasion as predictors of recurrence in rectal adenocarcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34(9):798–804. doi: 10.1007/BF02051074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wasif N, et al. Predictors of occult nodal metastasis in colon cancer: results from a prospective multicenter trial. Surgery. 2010;147(3):352–7. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fishel R, et al. The human mutator gene homolog MSH2 and its association with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer. Cell. 1993;75(5):1027–38. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90546-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gryfe R, et al. Tumor microsatellite instability and clinical outcome in young patients with colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(2):69–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001133420201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leach FS, et al. Mutations of a mutS homolog in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Cell. 1993;75(6):1215–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90330-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Papadopoulos N, et al. Mutation of a mutL homolog in hereditary colon cancer. Science. 1994;263(5153):1625–9. doi: 10.1126/science.8128251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bronner CE, et al. Mutation in the DNA mismatch repair gene homologue hMLH1 is associated with hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer. Nature. 1994;368(6468):258–61. doi: 10.1038/368258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu B, et al. Analysis of mismatch repair genes in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer patients. Nat Med. 1996;2(2):169–74. doi: 10.1038/nm0296-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bapat BV, et al. Family history characteristics, tumor microsatellite instability and germline MSH2 and MLH1 mutations in hereditary colorectal cancer. Hum Genet. 1999;104(2):167–76. doi: 10.1007/s004390050931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilson PM, Ladner RD, Lenz HJ. Predictive and prognostic markers in colorectal cancer. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2007;1(6):237–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parsons R, et al. Hypermutability and mismatch repair deficiency in RER+ tumor cells. Cell. 1993;75(6):1227–36. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90331-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kane MF, et al. Methylation of the hMLH1 promoter correlates with lack of expression of hMLH1 in sporadic colon tumors and mismatch repair-defective human tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1997;57(5):808–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Markowitz SD, Bertagnolli MM. Molecular origins of cancer: Molecular basis of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(25):2449–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Winder T, Lenz HJ. Molecular predictive and prognostic markers in colon cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tejpar S, et al. Microsatellite instability (MSI) in stage II and III colon cancer treated with 5FU-LV or 5FU-LV and irinotecan (PETACC 3-EORTC 40993-SAKK 60/00 trial) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15s. suppl; abstr 4001. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Laghi L, Bianchi P, Malesci A. Differences and evolution of the methods for the assessment of microsatellite instability. Oncogene. 2008;27(49):6313–21. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thibodeau SN, Bren G, Schaid D. Microsatellite instability in cancer of the proximal colon. Science. 1993;260(5109):816–9. doi: 10.1126/science.8484122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aaltonen LA, et al. Incidence of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer and the feasibility of molecular screening for the disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(21):1481–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805213382101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marcus VA, et al. Immunohistochemistry for hMLH1 and hMSH2: a practical test for DNA mismatch repair-deficient tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23(10):1248–55. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199910000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hampel H, et al. Screening for the Lynch syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer) N Engl J Med. 2005;352(18):1851–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ribic CM, et al. Tumor microsatellite-instability status as a predictor of benefit from fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(3):247–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Popat S, Hubner R, Houlston RS. Systematic review of microsatellite instability and colorectal cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(3):609–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roth AD, et al. Stage-specific prognostic value of molecular markers in colon cancer: Results of the translational study on the PETACC 3-EORTC 40993-SAKK 60-00 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15s. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.3452. suppl; abstr 4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Samowitz WS, et al. Microsatellite instability in sporadic colon cancer is associated with an improved prognosis at the population level. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10(9):917–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sargent DJ, et al. Confirmation of deficient mismatch repair (dMMR) as a predictive marker for lack of benefit from 5-FU based chemotherapy in stage II and III colon cancer (CC): A pooled molecular reanalysis of randomized chemotherapy trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008 May 20;26 suppl; abstr 4008. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meyers M, et al. Role of the hMLH1 DNA mismatch repair protein in fluoropyrimidinemediated cell death and cell cycle responses. Cancer Res. 2001;61(13):5193–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carethers JM, et al. Mismatch repair proficiency and in vitro response to 5- fluorouracil. Gastroenterology. 1999;117(1):123–31. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70558-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim GP, et al. Prognostic and predictive roles of high-degree microsatellite instability in colon cancer: a National Cancer Institute-National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Collaborative Study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(7):767–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.8172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bertagnolli MM, et al. Microsatellite instability predicts improved response to adjuvant therapy with irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin in stage III colon cancer: Cancer and Leukemia Group B Protocol 89803. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(11):1814–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wolmark N, et al. A phase III trial comparing mFOLFOX6 to mFOLFOX6 plus bevacizumab in stage II or III carcinoma of the colon: Results of NSABP Protocol C-08. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(18s):Abstract LBA4. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Allegra CJ, et al. Phase III Trial Assessing Bevacizumab in Stages II and III Carcinoma of the Colon: Results of NSABP Protocol C-08. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(1):11–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.0855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Van Cutsem E. Lessons from the adjuvant bevacizumab trial on colon cancer: what next? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Roche . Roche provides results on Avastin in adjuvant colon cancer. 2010. Press release Roche Basel. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Watanabe T, et al. Molecular predictors of survival after adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(16):1196–206. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104193441603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fearon ER, et al. Identification of a chromosome 18q gene that is altered in colorectal cancers. Science. 1990;247(4938):49–56. doi: 10.1126/science.2294591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shibata D, et al. The DCC protein and prognosis in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(23):1727–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612053352303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jen J, et al. Allelic loss of chromosome 18q and prognosis in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(4):213–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407283310401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Popat S, Houlston RS. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the relationship between chromosome 18q genotype, DCC status and colorectal cancer prognosis. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(14):2060–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Martinez-Lopez E, et al. Allelic loss on chromosome 18q as a prognostic marker in stage II colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 1998;114(6):1180–7. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70423-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Iino H, et al. Molecular genetics for clinical management of colorectal carcinoma. 17p, 18q, and 22q loss of heterozygosity and decreased DCC expression are correlated with the metastatic potential. Cancer. 1994;73(5):1324–31. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940301)73:5<1324::aid-cncr2820730503>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ogunbiyi OA, et al. Confirmation that chromosome 18q allelic loss in colon cancer is a prognostic indicator. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(2):427–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lanza G, et al. Chromosome 18q allelic loss and prognosis in stage II and III colon cancer. Int J Cancer. 1998;79(4):390–5. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980821)79:4<390::aid-ijc14>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jernvall P, et al. Loss of heterozygosity at 18q21 is indicative of recurrence and therefore poor prognosis in a subset of colorectal cancers. Br J Cancer. 1999;79(5–6):903–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bertagnolli MM, et al. Presence of 18q loss of heterozygosity (LOH) and disease-free and overall survival in stage II colon cancer: CALGB Protocol 9581. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15s. (supple; abstr 4012) [Google Scholar]

- 82.Alazzouzi H, et al. SMAD4 as a prognostic marker in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(7):2606–11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Alhopuro P, et al. SMAD4 levels and response to 5-fluorouracil in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(17):6311–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Boulay JL, et al. SMAD7 is a prognostic marker in patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2003;104(4):446–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Barratt PL, et al. DNA markers predicting benefit from adjuvant fluorouracil in patients with colon cancer: a molecular study. Lancet. 2002;360(9343):1381–91. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11402-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sotiriou C, Pusztai L. Gene-expression signatures in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(8):790–800. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0801289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Paik S, et al. A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, nodenegative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(27):2817–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Paik S, et al. Gene expression and benefit of chemotherapy in women with nodenegative, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(23):3726–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang Y, et al. Gene expression profiles and molecular markers to predict recurrence of Dukes’ B colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(9):1564–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Barrier A, et al. Stage II colon cancer prognosis prediction by tumor gene expression profiling. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(29):4685–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.O’Connell MJ, et al. Relationship between tumor gene expression and recurrence in four independent studies of patients with stage II/III colon cancer treated with surgery alone or surgery plus adjuvant fluorouracil plus leucovorin. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(25):3937–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.9538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kerr D, et al. A quantitative multigene RT-PCR assay for prediction of recurrence in stage II colon cancer: Selection of the genes in four large studies and results of the independent, prospectively designed QUASAR validation study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15s. (suppl; abstr 4000) [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lin JE, et al. Guanylyl cyclase C in colorectal cancer: susceptibility gene and potential therapeutic target. Future Oncol. 2009;5(4):509–22. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Waldman SA, et al. Association of GUCY2C expression in lymph nodes with time to recurrence and disease-free survival in pN0 colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2009;301(7):745–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Teixeira L, et al. Efficacy of FOLFOX4 as adjuvant therapy in stage II colon cancer (CC): A new analysis of the MOSAIC trial according to risk factors. J Clin Oncol. 2101;28(15s):abstr 3524. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Quasar Collaborative, G., et al., . Adjuvant chemotherapy versus observation in patients with colorectal cancer: a randomised study. Lancet. 2007;370(9604):2020–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61866-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Figueredo A, Coombes ME, Mukherjee S. Adjuvant therapy for completely resected stage II colon cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3):CD005390. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005390.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Benson AB, 3rd, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(16):3408–19. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pallis AG, et al. EORTC Elderly Task Force experts’ opinion for the treatment of colon cancer in older patients. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36(1):83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jackson McCleary NA, et al. Impact of older age on the efficacy of newer adjuvant therapies in >12,500 patients (pts) with stage II/III colon cancer: Findings from the ACCENT Database. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15s):2009. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.6638. (suppl; abstr 4010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Andre T, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(23):2343–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sargent DJ, et al. A pooled analysis of adjuvant chemotherapy for resected colon cancer in elderly patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(15):1091–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fata F, et al. Efficacy and toxicity of adjuvant chemotherapy in elderly patients with colon carcinoma: a 10-year experience of the Geisinger Medical Center. Cancer. 2002;94(7):1931–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Laurie JA, et al. Surgical adjuvant therapy of large-bowel carcinoma: an evaluation of levamisole and the combination of levamisole and fluorouracil. The North Central Cancer Treatment Group and the Mayo Clinic. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7(10):1447–56. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.10.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Taal BG, Van Tinteren H, Zoetmulder FA. Adjuvant 5FU plus levamisole in colonic or rectal cancer: improved survival in stage II and III. Br J Cancer. 2001;85(10):1437–43. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Francini G, et al. Folinic acid and 5-fluorouracil as adjuvant chemotherapy in colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 1994;106(4):899–906. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90748-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Glimelius B, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in colorectal cancer: a joint analysis of randomised trials by the Nordic Gastrointestinal Tumour Adjuvant Therapy Group. Acta Oncol. 2005;44(8):904–12. doi: 10.1080/02841860500355900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]