Abstract

Clinical mutation screening of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes for the presence of germline inactivating mutations is used to identify individuals at elevated risk of breast and ovarian cancer. Variants identified during screening are usually classified as pathogenic (increased risk of cancer) or not pathogenic (no increased risk of cancer). However, a significant proportion of genetic tests yield variants of uncertain significance (VUS) that have undefined risk of cancer. Individuals carrying these VUS cannot benefit from individualized cancer risk assessment. Recently a quantitative “posterior probability model” for assessing the clinical relevance of VUS in BRCA1 or BRCA2 that integrates multiple forms of genetic evidence has been developed. Here we provide a detailed review of this model. We describe the components of the model and explain how these can be combined to calculate a posterior probability of pathogenicity for each VUS. We explain how the model can be applied to public data and provide Tables that list the VUS that have been classified as not pathogenic or pathogenic using this method. While we use BRCA1 and BRCA2 VUS as examples, the method can be used as a framework for classification of the pathogenicity of VUS in other cancer genes.

Keywords: BRCA1, BRCA2, VUS classification, missense mutations

Introduction

Clinical mutation screening of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 breast and ovarian cancer predisposition genes (MIM#s 113705, 600185, respectively) for the presence of germline inactivating mutations is a widely used method for identifying individuals at elevated risk of breast and ovarian cancer. The criteria for genetic testing of these genes vary, but generally women with a significant family history of these cancers are offered testing. The following are possible outcomes of genetic testing:

Pathogenic mutations: Based on testing criteria, between 10% and 15% of all genetic tests yield known pathogenic mutations, often called “deleterious” mutations (See Definitions of Vocabulary) that truncate and/or inactivate BRCA1 or BRCA2 and predispose to an elevated age-specific risk of breast and ovarian cancer. These are DNA variants that take the form of nonsense mutations, small out-of-frame insertion or deletion mutations, larger gene rearrangements and splicing alterations that all truncate or remove important domains of the BRCA proteins. In addition, certain missense substitutions are considered “pathogenic” because they inactivate protein function. These mutations can be confidently predicted to disrupt the function of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 protein leading to increased risk of breast or ovarian cancer. Individuals who carry inherited pathogenic mutations in their DNA have, on average, substantially elevated age-dependent risks of breast and ovarian cancer compared to those without mutations in the general population. Women carrying pathogenic BRCA1 mutations have a 59% risk of breast cancer and a 34% risk of ovarian cancer by age 70, whereas women with BRCA2 pathogenic mutations have a 51% breast cancer and 11% ovarian cancer risk by age 80 (Antoniou, et al., 2008). These risks may vary by population but are always significantly elevated over population risks. Importantly, individuals with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and their family members can benefit from risk assessment, enhanced cancer surveillance, risk-reducing prophylactic mastectomy and oophorectomy, and counseling. Specifically, those carrying pathogenic mutations are known to be at substantially elevated risk of cancer, whereas individuals from the same families who do not carry the pathogenic mutation benefit from the knowledge that they are not at increased risk of cancer.

Not pathogenic or low clinical significance (LCS) variants: A further 80% of tests either fail to identify alterations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes or identify variants that are considered to be “not pathogenic”, often termed “neutral”, or of “low clinical significance” low clinical significance” (See Sources of Data). This group of variants includes common polymorphisms, seen in greater than 1% of alleles in the general population, and rare variants that display little or no association with breast cancer risk in families. These variants are predicted or have been shown to have no significant influence on the normal function of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 proteins.

Variants of uncertain significance (VUS): In many countries as many as 30% to 50% of variants identified during BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene testing are Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS), also referred to as unclassified variants (UVs) (Hofstra, et al., 2008). In the USA these variants may only account for 5% to 10% of alterations because of ongoing classification efforts by Myriad Genetics Laboratories Inc. VUS are mainly missense substitutions that result in single amino acid changes, but also include in-frame small deletions or insertions that change only small numbers of amino acids, silent coding alterations that may influence splicing or translation, or intronic changes of unknown influence on gene splicing. These alterations have unknown functional effects on BRCA1 and BRCA2 and cannot at this time be classified as either “Pathogenic” or “Not Pathogenic/low clinical significance”. As a result individuals found to carry these variants in their DNA and members of their families cannot benefit from risk assessment measures offered to members of families known to carry BRCA1 or BRCA2 deleterious mutations. Unfortunately, even though individual VUS are rare, the finding of a VUS is not a rare event. At present, there are hundreds of unique VUS recorded in the BRCA genes (Breast Cancer Information Core Database: http://research.nhgri.nih.gov/bic/).

Interpretation of a VUS in a patient sample

A VUS result issued by a testing laboratory means that that there was insufficient evidence to classify the alteration as either pathogenic or not pathogenic at the time of the test. Many individuals diagnosed with a VUS ask whether the finding of a VUS results from a questionable laboratory call or from technical limitations. Given the quality control measures of most diagnostic laboratories it should be made clear that a DNA alteration exists, but the clinical interpretation of that DNA alteration is unclear. A VUS finding should be considered not clinically useful and should not be factored into clinical decision making. This should remain so until further evidence emerges to shift the interpretation toward either a not pathogenic or pathogenic interpretation. Since additional information can result in reclassification of VUS as “pathogenic” or “not pathogenic”, as described below, continuous evaluation of the literature is an important component of VUS interpretation.

Information about VUS that is often not provided as part of clinical testing reports is stored in a number of different locations. The Breast Cancer Information Core (BIC) (http://research.nhgri.nih.gov/bic/) lists many of the VUS that have been identified through clinical testing or research studies and have been voluntarily reported to the BIC. Efforts are underway to update the BIC with results from testing laboratories around the world. More recently an LOVD database has been developed at Leiden University in The Netherlands (http://chromium.liacs.nl/LOVD2/cancer/home.php?select_db=BRCA1) that summarizes the findings in the scientific literature for many VUS. While this database does not attempt to interpret the results of the studies, it is particularly useful for understanding the range of functional and genetic studies that may have been applied to certain VUS for the purpose of clinical classification.

The Posterior Probability model for classification of BRCA1 and BRCA2 VUS

Multiple methods are now being applied to move interpretation of a VUS toward a conclusion. The method that has made the greatest contribution to classification of individual VUS is termed the “posterior probability model”. This method combines prior probabilities of causality derived from an evolutionary sequence conservation model (Align-GVGD) (http://agvgd.iarc.fr/) with likelihoods of causality (Easton, et al., 2007) derived from measures of associations between the VUS and cancer. Specifically, the likelihood component uses information on a) how the VUS segregates with cancer in families, b) whether the VUS is seen in combination with a known pathogenic mutation (which should be lethal for BRCA1 or cause Fanconi Anemia for BRCA2 if the VUS is pathogenic), c) the personal and family history of cancer (age of onset and cancer type) associated with the VUS, and d) the histopathology of the associated breast tumors. By combining the prior probability with the likelihood component a final or posterior probability of causality for each VUS can be calculated. While a number of assumptions are made in these calculations, and there is a degree of error associated with each component of the model, this approach has been used to classify several BRCA1 and BRCA2 VUS as pathogenic and not pathogenic. Here we explain the basis of the model, we outline how it can be applied to public datasets and provide current lists of BRCA1 and BRCA2 VUS that have been classified as pathogenic or not pathogenic by this method. This information should allow the research and clinical community to better understand and critically evaluate the interpretation of results in the literature. This should also bring greater transparency and clarity to the provision of information about VUS to patients.

A. The Multifactorial (Combined) Likelihood Model

“Segregation Analysis” within the family

Segregation analysis results in an odds or likelihood ratio that a VUS is linked to breast and/or ovarian cancer in families more than expected by chance. If most individuals in families carrying a particular VUS develop breast cancer then there is a strong likelihood that the VUS may be causing the cancer phenotype. Unfortunately, the power of this analysis is dependent on access to genotype data from large numbers of individuals, which is rarely available for BRCA1 and BRCA2 VUS. Thus, the information derived from segregation analysis for BRCA VUS interpretation is seldom conclusive. Nevertheless, it can be of great value in selected large families with multiple living affected individuals.

Co-occurrence in “trans”

Homozygosity for BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic mutations leads to embryonic lethality or Fanconi anemia, respectively Therefore, an odds or likelihood against the VUS being pathogenic can be calculated when a VUS is found to co-occur with a pathogenic mutation, if it can be demonstrated that the mutation and the VUS occur on different copies of the gene (in trans) rather than within the same copy of the gene (in cis) (Easton, et al., 2007). The use of co-occurrence data alone for classification of VUS is complicated by the existence of “hypomorphic variants” with subtle effects on protein function and on risk that may not result in embryonic lethality or Fanconi anemia.

Personal and family history

Classical cancer predisposing truncating mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 are associated with a distinct phenotype, which includes early onset of cancer in individuals and multiple cases of breast and/or ovarian cancer in families. When individuals and families with pathogenic mutations were compared to individuals and families without mutations, specific aspects of the BRCA1/BRCA2 phenotype, such as age of onset of cancer and number of cancers of different types, were associated with specific likelihoods of a pathogenic mutation being present (Goldgar, et al., 2004). This was subsequently applied to families with VUS so that each specific age of onset and cancer history combination in a family with a VUS is associated with a specific likelihood that the VUS is pathogenic (Easton, et al., 2007). Importantly, these original calculations were based on mutation data provided by Myriad Genetic Laboratories Inc. Thus, these likelihoods need to be recalibrated when family history data is derived from other testing centers that use different testing criteria.

Pathology profile

Statistical weighting can be applied to histopathologic characteristics of tumors from VUS carriers based on characteristics commonly observed in tumors containing known pathogenic BRCA-gene mutations. Specifically, a high proportion of breast tumors with pathogenic BRCA1 mutations are high grade and are negative for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2/neu expression. Similarly, BRCA2 mutant tumors are moderate to high grade and are more likely to display tubule formation (Bane, et al., 2009; Lakhani, et al., 2002). Ovarian tumors in both BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers tend to be ER positive and high grade with serous histology (Chenevix-Trench, et al., 2006; Spurdle, et al., 2008). By comparing the frequency of these and other characteristics in tumors from carriers and non-carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic mutations, a series of likelihoods in favor of the variant being pathogenic have been estimated (Chenevix-Trench, et al., 2006; Spurdle, et al., 2008). Here we show the odds associated with a combination of ER status, tumor grade and cytokeratin status for BRCA1 breast tumors (Table 1). For example, while breast tumors in a BRCA1 VUS carrier that are ER negative and grade 2 or 3 provide evidence in favor of the variant being pathogenic, all other combinations of ER and Grade provide evidence against the variant being cancer-associated. In contrast, ER status and grade offer little predictive power for BRCA2 VUS. Only tubule formation has proven useful for classification of VUS, with a tubule formation score of three associated with odds of 1.2:1 in favor of pathogenicity and a score <3 associated with odds of 2:1 against pathogenicity (Chenevix-Trench, et al., 2006; Spurdle, et al., 2008). Importantly, because individual tumor characteristics may not be conditionally independent, LRs for each individual tumor characteristic should not be combined in an integrated evaluation of a particular VUS (Goldgar, et al., 2008). Instead a single estimate based on the known tumor characteristics, such as that shown for ER status and grade above, should be used. Because some of these estimates are based on small numbers of tumors, efforts at refining and/or establishing the likelihood estimates associated with these and other characteristics of BRCA1 mutant breast tumors such as cytokeratin 5/6, EGFR and TP53 status are underway using tumor information from large numbers of known BRCA1 carriers and non-carriers from the Breast Cancer Association Consortium (BCAC) and Consortium for Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2 (CIMBA). In the future, mutation, expression, miRNA or methylation profiles associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 status may also prove useful for VUS classification.

Table 1. Frequencies of pathology characteristics in breast tumors from 600 BRCA1 carriers diagnosed under age 60 and 258 tumors from sporadic cases diagnosed under age 60.

| Characteristic | BRCA1 tumors (%) | Control Tumors (%) | LR (BRCA1 path) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ER +ve | 9.6 | 67.2 | 0.14 |

| ER +ve Grade 1 | 0.6 | 13.0 | 0.05 |

| ER +ve Grade 2 | 3.5 | 25.0 | 0.14 |

| ER +ve Grade 3 | 5.1 | 28.0 | 0.18 |

| ER −ve, Grade 1 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 0.97 |

| ER −ve, Grade 2 | 9.0 | 4.7 | 1.93 |

| ER −ve, Grade 3 | 80.0 | 27.0 | 2.95 |

| ER−ve, CK5/6−ve, CK14 −ve | 20.9 | 24.0 | 0.87 |

| ER−ve, CK5/6+ve, CK14 −ve | 13.4 | 2.4 | 5.58 |

| ER−ve, CK5/6−ve, CK14 +ve | 12.4 | 4.8 | 2.58 |

| ER−ve, CK5/6+ve, CK14 +ve | 43.8 | 1.6 | 27.38 |

Calculation of multifactorial likelihood estimates

To determine the overall likelihood ratio (or odds ratio) for pathogenicity vs. non-pathogenicity for a particular VUS, the LRs for the VUS from each independent component of the model (which may be composed of multiple families, tumors, etc., each contributing to the overall LR for that component) are multiplied together. These calculations are also often conducted on a log scale where Log odds for each category are added. Using this approach, such odds/likelihood ratios from manuscripts or separate studies can be combined to generate updated likelihood ratios, provided that the datasets are independent.

Likelihood of pathogenicity = LR Co-occurrence × LR Pathology × LR Segregation × LR cancer history

*Where LR is likelihood ratio or odds of pathogenicity

B. The sequence-based Prior Probability model

A number of “in silico” methods based on orthologous protein sequence alignments are available for predicting the influence of variants on protein activity. Examples include Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant (SIFT) (available at: http://blocks.fhcrc.org/sift/SIFT.html), and Polymorphism Phenotyping (PolyPhen). These methods are based on the notion that phylogenetic conservation of protein sequence throughout evolution reflects the requirement for certain amino acids for protein activity.

Recently, the Align-GVGD algorithm (http://agvgd.iarc.fr/agvgd_input.php) was developed to account for the extent of the physicochemical change in an amino acid residue in a VUS and the extent of the evolutionary conservation of the amino acid residue in that position (Tavtigian, et al.). Using this method, variants within specific functional domains of BRCA1 (N-terminal RING finger domain (amino acids 1-102) and C-terminal BRCT domains and coiled coil domain (amino acids 1396-1863)) and BRCA2 DNA binding domain (amino acids 2400-3190) are graded by the structural/chemical impact of the variants and the evolutionary conservation of the mutated amino acid residues. These Align-GVGD grades (C0, C15, C25, C35, C45, C55, and C65; in which a C0 variant occurs in a poorly conserved amino acid and a C65 variant occurs in an amino acid fully conserved from pufferfish through humans) have been correlated with specific probabilities of cancer causality (prior probabilities) and validated relative to the personal and family cancer history LR estimates described above (Tavtigian, et al., 2008). Thus, a variant in a defined functional domain with a C65 grade is assigned a prior probability of 0.81 (81% chance of being pathogenic) (Table 2). In contrast, the estimated prior probability for a variant in a key domain with a C0 grade was originally 0.00 (95%CI 0.00-0.06) (Tavtigian, et al., 2008). However, because a prior of 0.00 cannot be used in a Bayesian calculation, and in the interest of making the prior probabilities slightly more conservative, these VUS are assigned a prior probability of 0.03 (3% chance of being deleterious), which is the midpoint of the confidence interval. For example, a query for the BRCA2 VUS D2723H on the AlignGVGD website yields a Prediction Grade of C65 equating to a prior probability of pathogenicity of 0.81, meaning that the variant is fully conserved from sea urchin to human, is predicted to have a substantial functional impact and has a high probability of being pathogenic (Table 2) (Tavtigian, et al., 2008). VUS located outside of the key functional domains are all attributed a grade of C0 and a lower probability of pathogenicity of 0.02. Originally the prior probabilities of these variants were estimated at 0.00 (95%CI 0.00-0.04) (Easton, et al., 2007), but for the reasons given above we have again assigned the prior probability at the midpoint of the confidence interval.

Table 2. Prior probabilities associated with VUS from defined functional domains# graded by Align-GVGD.

| Align-GVGD grade | Prior Probability | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| C65 | 0.81 | (0.61-0.95) |

| C35-C55 | 0.66 | (0.34-0.93) |

| C15-C25 | 0.29 | (0.09-0.56) |

| C0 | 0.03 | (0.00-0.06) |

| Outside functional domains | 0.02 | (0.00-0.04) |

| Splicing consensus site alteration | 0.96 | (0.91-1.00) |

| Intronic variants outside the consensus dinucleotides | 0.26 | (0.15-0.39) |

BRCA1 BARD1 binding (amino acids 1-102) and BRCT domains and coiled coil domain (amino acids 1396-1863), BRCA2 DNA binding domain (amino acids 2400-3190). CI: Confidence Interval

VUS located in consensus dinucleotides at exon/intron boundaries (nucleotide +1/+2 or −1/−2 relative to an exon) are attributed specific prior probabilities of 1.0 (95%CI 0.91-1.0). However, a prior probability of 0.96 reflecting the midpoint of the estimate is more commonly applied. These variants are expected to alter the consensus splice site activity and to uniformly disrupt protein function either through truncation or in-frame deletion of large regions of the encoded proteins (Easton, et al., 2007). Intronic variants outside the donor or acceptor dinucleotide have been attributed a prior probability of 0.26 (0.15–0.39 95% CI), which is the midpoint of the estimate derived from available data (Easton, et al., 2007). Efforts are ongoing to assign prior probabilities to other variants in exons and introns that may have influence on splicing. This will be somewhat dependent on standards defined by detailed laboratory based splicing studies. An added complication is that intronic and exonic variants may also influence gene expression through effects on splicing regulation that lead to partial effects on splicing of alleles. Whether partial effects on splicing have influences on cancer risk equivalent to truncating mutations remains to be determined In addition, VUS in other domains that become functionally characterized over time will be attributed higher prior probability scores.

Importantly, each probability shown in Table 2 has associated wide 95% confidence intervals. Because these confidence intervals allow for substantial variation in prior probability within each Align-GVGD grade, an IARC Working Group on VUS (Plon, et al., 2008) noted that the probabilities should not be used in isolation to predict the causality or pathogenicity of a VUS. Instead these prior probabilities should be combined with likelihood estimates to derive posterior probabilities of pathogenicity for VUS.

C. Posterior Probability model

The sequence based “prior probability” and the “combined likelihood” estimates can be used to calculate the “posterior probability” of a VUS being pathogenic. Similarly, all other independent lines of evidence that can be expressed mathematically as likelihood ratios can be integrated with the prior probability to generate a posterior probability of pathogenicity for each variant. The posterior probability on a scale of 0 to 1.00 is calculated using Bayes theorem by first determining the “Posterior Odds of pathogenicity” and then generating the final “Posterior probability of pathogenicity” as shown in the box below.

Posterior Odds = Likelihood ratio × [prior probability/(1-prior probability)]

Posterior Probability of Pathogenicity = Posterior Odds / (Posterior Odds + 1)

Essentially, the term prior probability/(1-prior probability) represents the initial odds ratio in favor of a given VUS being pathogenic vs. not pathogenic before any of the model components are added. For example, if the prior probability from Align-GVGD is 0.8 and the combined LR from all other sources is 100 (odds of 100:1 in favor of pathogenicity) then the Posterior odds are 100 × 0.8/0.2 = 400:1 in favor of the VUS being pathogenic and the Posterior Probability of causality is: 400/401 = 1.00. Using this approach, publically available multifactorial likelihood estimates (Easton, et al., 2007) can be readily combined with the prior probabilities available through the Align-GVGD website (http://agvgd.iarc.fr/) (Tavtigian, et al.) to calculate ”posterior probabilities” for BRCA1 and BRCA2 VUS.

Based upon the numerical value of the posterior probability calculations, The IARC Working Group on VUS introduced a clinical translation step, summarized in Table 3, involving a five-tier classification scheme (Plon, et al., 2008). Class 1 and 2 are likely not pathogenic; Class 3 remains a true VUS; Class 4 and 5 are treated as pathogenic for clinical purposes. A Clinical Working Group affiliated with the IARC group further proposed how these levels of predicted pathogenicity might be used to counsel patients about cancer surveillance and when it is reasonable to use a VUS as a marker for predictive testing in at-risk relatives. In brief, when a Class 1 or 2 variant is identified, the variant can be excluded from further consideration, but the proband and family members must be counseled on the basis of family history of cancer which could result from a pathogenic mutation in another predisposition gene. When a Class 3 variant is identified, the same approach should be taken, and the variant cannot be used for determining whether additional family members are at risk. In cases where an effect on protein function in a functional assay, or high prior probabilities based on Align-GVGD are known, counseling may lean towards a more aggressive approach to risk management. When a Class 4 or Class 5 variant is identified the individual must be considered a carrier of a fully pathogenic mutation. High-risk surveillance involving frequent screening for breast and ovarian cancer or prevention options such as prophylactic oophorectomy and/or mastectomy, while accounting for the age of the individual, should be recommended. In addition, genetic testing of all at-risk relatives for the Class 4 or 5 variant should be recommended.

Table 3. Proposed classification for DNA sequence variants and correlation of clinical recommendation with probability that any given alteration is deleterious.

| Class | Definition | Posterior Probability | Clinical Testing | Surveillance recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Definitely pathogenic | >0.99 | Test at-risk relatives for the variant | Full high-risk surveillance |

| 4 | Likely pathogenic | 0.95-0.99 | Test at-risk relatives for the variant | Full high-risk surveillance |

| 3 | Uncertain | 0.05-0.949 | Do not use as predictive testing in at-risk relatives | Counsel based on family history and other risk factors |

| 2 | Likely not pathogenic | 0.001-0.049 | Do not use as predictive testing in at-risk relatives | Counsel as if no mutation detected |

| 1 | Not Pathogenic | <0.001 | Do not use as predictive testing in at-risk relatives | Counsel as if no mutation detected |

Adapted from Plon et al., 2008.

Application of the Posterior Probability Model

The multifactorial model has been applied to many BRCA1 and BRCA2 VUS for which family and/or pathology data are available. Some of the results from these analyses can be found scattered across a large number of publications. However, it is quite challenging to screen the scientific and medical literature in order to determine whether a specific VUS has actually been classified. In addition, some results from posterior probability model analyses and/or the information needed for assessment of VUS using the posterior probability model are often accessible to only a small number of researchers actively working to classify VUS and are not available to other researchers, patients and clinical care providers.

To simplify this process we have screened the current literature for results derived from correct applications of the multifactorial likelihood or posterior probability models to VUS in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Tables 4 and 5 display the current lists of BRCA1 and BRCA2 missense variants and small insertions and deletions that have been classified as Class 1 and 2 (Not pathogenic/likely not pathogenic) or Class 4 and 5 (likely pathogenic/pathogenic) using the posterior probability model. We do not show Class 3 or VUS.

Table 4. BRCA1 VUS Classified as Class 1, 2 or Class 4, 5.

| BRCA1 exon | Codon | HGVS: protein level | BIC: DNA level | HGVS: DNA level | Odds in favor of causality | Reference | Prior Probability of being deleterious | Posterior Probability of being deleterious | IARC Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | M18T | p.Met18Thr | 172T>C | c.53T>C | 31.61 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.66 | 0.98 | 4 |

| 2 | L22S | p.Leu22Ser | 184T>C | c.65T>C | 38.88 | Sweet et al., 2010 | 0.81 | 0.99 | 5 |

| 3 | T37K | p.Thr37K | 229C>A | c.110C>A | 634.47 | Sweet et al., 2010 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 3 | C39R | p.Cys39Arg | 234T>C | c.115T>C | 34.60 | Sweet et al., 2010 | 0.81 | 0.99 | 5 |

| 3 | C44S | p.Cys44Ser | 249T>A | c.130T>A | 149.60 | Sweet et al., 2010 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 3 | C44Y | p.Cys44Tyr | 250G>A | c.131G>A | 83.48 | Sweet et al., 2010 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 3 | K45Q | p.Lys45Gln | 252A>C | c.133A>C | 0.03 | Sweet et al., 2010 | 0.03 | 8.00×10−4 | 1 |

| 5 | C61G | p.Cys61Gly | 300T>G | c.181T>G | 1285.43 | Spearman et al., 2008 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 5 | D67Y | p.Asp67Tyr | 318G>T | c.199G>T | 9.38×10−5 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.03 | 2.90×10−6 | 1 |

| 7 | Y105C | p.Tyr105Cys | 433A>G | c.314A>G | 5.15×10−6 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.05×10−7 | 1 |

| 7 | I124V | p.Ile124Val | 489A>G | c.370A>G | 6.80×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.39×10−4 | 1 |

| 7 | N132K | p.Asn132Lys | 515C>A | c.396C>A | 8.13×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.66×10−4 | 1 |

| 7 | P142H | p.Pro142His | 544C>A | c.425C>A | 5.04×10−5 | Chenevix-Trench et al., 2006 | 0.02 | 1.03×10−6 | 1 |

| 7 | E143K | p.Glu143Lys | 546G>A | c.427G>A | 5.35×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.09×10−5 | 1 |

| 8 | Q155E | p.Gln155Glu | 582C>G | c.463C>G | 1.91×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 3.89×10−5 | 1 |

| 8 | Y179C | p.Tyr179Cys | 655A>G | c.536A>G | 8.50×10−11 | Spurdle et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 1.73×10−12 | 1 |

| 9 | S186Y | p.Ser186Tyr | 676C>A | c.557C>A | 3.83×10−10 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 7.82×10−12 | 1 |

| 9 | V191I | p.Val191Ile | 690G>A | c.571G>A | 7.69×10−6 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.57×10−7 | 1 |

| 11 | L246V | p.Leu246Val | 855T>G | c.736T>G | 2.60×10−5 | Tavtigian et al., 2006 | 0.02 | 5.31×10−7 | 1 |

| 11 | A280G | p.Ala280Gly | 958C>G | c.839C>G | 3.76×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 7.67×10−5 | 1 |

| 11 | M297I | p.Met297Ile | 1010G>A | c.891G>A | 3.11×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 6.34×10−5 | 1 |

| 11 | P334H | p.Pro334His | 1120C>A | c.1001C>A | 1.34 | Spearman et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 2 |

| 11 | P334L | p.Pro334Leu | 1120C>T | c.1001C>T | 1.33×10−5 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 2.71×10−7 | 1 |

| 11 | Q356R | p.Gln34Arg | 1186A>G | c.1067A>G | <1.00×10−10 | Tavtigian et al., 2006 | 0.02 | <2.04×10−12 | 1 |

| 11 | D369del | p.Asp369del | 1225del3 | c.1105_1107del | 3.00×10−4 | Easton et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 6.13×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | D369N | p.Asp369Asn | 1224G>A | c.1105G>A | 2.78×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 5.68×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | D420Y | p.Asp420Tyr | 1377G>T | c.1258G>T | 0.01 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.66×10−4 | 1 |

| 11 | N473S | p.Asn473Ser | 1537A>G | c.1418A>G | 1.65×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 3.37×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | F486L | p.Phe486Leu | 1575T>C | c.1456T>C | 9.13×10−11 | Spurdle et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 1.86×10−12 | 1 |

| 11 | R496H | p.Arg496His | 1606G>A | c.1487G>A | 9.20×10−5 | Tavtigian et al., 2006 | 0.02 | 1.88×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | R496C | p.Arg496Cys | 1605C>T | c.1486C>T | 0.04 | Chenevix-Trench et al., 2006 | 0.02 | 8.91×10−4 | 1 |

| 11 | R504H | p.Arg504His | 1630G>A | c.1511G>A | 5.21×10−5 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.06×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | N550H | p.Asn550His | 1767A>C | c.1648A>C | 8.00×10−11 | Spurdle et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 1.63×10−12 | 1 |

| 11 | E597K | p.Glu597Lys | 1908G>A | c.1789G>A | 3.40×10−9 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 6.92×10−11 | 1 |

| 11 | A622V | p.Ala622Val | 1984C>T | c.1865C>T | 1.00×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 2.12×10−5 | 1 |

| 11 | D642H | p.Asp642His | 2043G>C | c.1924G>C | 6.87×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.40×10−5 | 1 |

| 11 | K654Q | p.Lys654Gln | 2079A>C | c.1960A>C | 0.34 | Osorio et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 6.86×10−3 | 2 |

| 11 | L668F | p.Leu668Phe | 2121C>T | c.2002C>T | 9.52×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.94×10−4 | 1 |

| 11 | D693N | p.Asp693Asn | 2196G>A | c.2077G>A | 1.00×10−10 | Tavtigian et al., 2006 | 0.02 | 2.04×10−12 | 1 |

| 11 | N723D | p.Asn723Asp | 2286A>G | c.2167A>G | 1.55×10−8 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 3.17×10−10 | 1 |

| 11 | E736A | p.Glu736Ala | 2326A>C | c.2207A>C | 0.48 | Spearman et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 9.62×10−3 | 2 |

| 11 | V772A | p.Val772Ala | 2434T>C | c.2315T>C | 9.40×10−6 | Tavtigian et al., 2006 | 0.02 | 1.92×10−7 | 1 |

| 11 | Q804H | p.Gln804His | 2531G>C | c.2412G>C | 0.02 | Chenevix-Trench et al., 2006 | 0.02 | 4.46×10−4 | 1 |

| 11 | N810Y | p.Asn810Tyr | 2547A>T | c.2428A>T | 1.14×10−11 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 2.33×10−13 | 1 |

| 11 | K820E | p.Lys820Gln | 2577A>G | c.2458A>G | <1.00×10−10 | Tavtigian et al., 2006 | 0.02 | <2.04×10−12 | 1 |

| 11 | T826K | p.Thr826Lys | 2596C>A | c.2477C>A | 9.97×10−8 | Spurdle et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 2.03×10−9 | 1 |

| 11 | R841W | p.Arg841Trp | 2640C>T | c.2521C>T | 1.12×10−10 | Goldgar et al., 2004 | 0.02 | 2.29×10−12 | 1 |

| 11 | E842G | p.Glu842Gly | 2644A>G | c.2525A>G | 2.11×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 4.30×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | Y856H | p.Tyr856His | 2685T>C | c.2566T>C | 8.80×10−3 | Tavtigian et al., 2006 | 0.02 | 1.80×10−4 | 1 |

| 11 | K862E | p.Lys862Glu | 2703A>G | c.2584A>G | 4.86×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 9.91×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | R866C | p.Arg866Cys | 2715C>T | c.2596C>T | 8.00×10−13 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.63×10−14 | 1 |

| 11 | P871L | p.Pro871Leu | 2731C>T | c.2612C>T | <1.00×10−10 | Tavtigian et al., 2006 | 0.02 | <2.04×10−12 | 1 |

| 11 | G890V | p.Gly890Val | 2788G>T | c.2669G>T | 2.00×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 4.08×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | V920A | p.Val920Ala | 2878T>C | c.2759T>C | 1.02 | Spurdle et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 2 |

| 11 | I925L | p.Ile925Leu | 2892A>C | c.2773A>C | 1.6×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 3.26×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | M1008I | p.Met1008Ile | 3143G>A | c.3024G>A | 9.6×10−7 | Tavtigian et al., 2006 | 0.02 | 1.96×10−8 | 1 |

| 11 | M1008V | p.Met1008Val | 3141A>G | c.3022A>G | <1.00×10−10 | Tavtigian et al., 2006 | 0.02 | <2.04×10−12 | 1 |

| 11 | R1028H | p.Arg1028His | 3202G>A | c.3083G>A | 4.90×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 9.98×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | E1038G | p.Gln1038Gly | 3232A>G | c.3113A>G | <1.00×10−10 | Tavtigian et al., 2006 | 0.02 | <2.04×10−12 | 1 |

| 11 | S1040N | p.Ser1040Asn | 3238G>A | c.3119G>A | <1.00×10−10 | Tavtigian et al., 2006 | 0.02 | <2.04×10−12 | 1 |

| 11 | I1044V | p.Ile1044Val | 3249A>G | c.3130A>G | 1.15×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 2.34×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | P1099L | p.Pro1099Leu | 3415C>T | c.3296C>T | 1.52×10−9 | Spurdle et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 3.09×10−11 | 1 |

| 11 | S1101N | p.Ser1101Asn | 3421G>A | c.3302G>A | 3.10×10−7 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 6.32×10−9 | 1 |

| 11 | K1109N | p.Lys1109Asn | 3446A>C | c.3327A>C | 1.51×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 3.07×10−5 | 1 |

| 11 | S1140G | p.Ser1140Gly | 3537A>G | c.3418A>G | 2.90×10−4 | Tavtigian et al., 2006 | 0.02 | 5.92×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | D1155H | p.Asp1155His | 3582G>C | c.3463G>C | 3.50×10−4 | Chenevix-Trench et al., 2006 | 0.02 | 7.14×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | K1183R | p.Lys1183Arg | 3667A>G | c.3548A>G | <1.00×10−10 | Tavtigian et al., 2006 | 0.02 | <2.04×10−12 | 1 |

| 11 | Q1200H | p.Gln1200His | 3719G>C | c.3600G>C | 0.35 | Osorio et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 7.09×10−3 | 2 |

| 11 | R1203Q | p.Arg1203Gln | 3727G>A | c.3608G>A | 1.79×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 3.65×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | E1214K | p.Glu1214Lys | 3759G>A | c.3640G>A | 3.38×10−8 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 6.89×10−10 | 1 |

| 11 | P1238L | p.Pro1238Leu | 3832C>T | c.3713C>T | 9.52×10−7 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.94×10−8 | 1 |

| 11 | V1247I | p.Val1247Ile | 3858G>A | c.3739G>A | 1.23×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 2.51×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | E1250K | p.Glu1250Lys | 3867G>A | c.3748G>A | 1.00×10−5 | Tavtigian et al., 2006 | 0.02 | 2.04×10−7 | 1 |

| 11 | S1266T | p.Ser1266Thr | 3916G>C | c.3797G>C | 5.56×10−5 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.13×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | I1275V | p.Ile1275Val | 3942A>G | c.3823A>G | 1.62×10−5 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 3.31×10−7 | 1 |

| 11 | R1347G | p.Arg1347Gly | 4158A>G | c.4039A>G | <1.00×10−10 | Tavtigian et al., 2006 | 0.02 | <2.04×10−12 | 1 |

| 11 | T1349M | p.Thr1349Met | 4165C>T | c.4046C>T | 2.16×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 4.42×10−5 | 1 |

| 11 | M1361L | p.Met1361Leu | 4200A>C | c.4081A>C | 9.62×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.96×10−4 | 1 |

| 13 | H1402Y | p.His1402Tyr | 4323C>T | c.4204C>T | 6.06×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.03 | 1.87×10−4 | 1 |

| 13 | E1419Q | p.Glu1419Gln | 4374G>C | c.4255G>C | 4.93×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.03 | 1.52×10−4 | 1 |

| 13 | R1443G | p.Arg1443Gly | 4446C>G | c.4327C>G | <0.02 | Carvalho et al., 2007 | 0.03 | <6.18×10−4 | 1 |

| 14 | N1468H | p.Asn1468His | 4521A>C | c.4402A>C | 2.97×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.03 | 9.18×10−5 | 1 |

| 14 | #R1495M | p.Arg1495Met | 4603G>T | c.4484G>T | 1.25×106 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 1 |

| 15 | S1512I | p.Ser1512Ile | 4654G>T | c.4535G>T | <1.00×10−10 | Tavtigian et al., 2006 | 0.03 | <3.09×10−12 | 1 |

| 15 | V1534M | p.Val1534Met | 4719G>A | c.4600G>A | 2.39×10−9 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.03 | 7.40×10−11 | 1 |

| 15 | D1546N | p.Asp1546Asn | 4755G>A | c.4636G>A | 5.60×10−3 | Tavtigian et al., 2006 | 0.03 | 1.73×10−4 | 1 |

| 15 | D1546Y | p.Asp1546Tyr | 4755G>T | c.4636G>T | 9.19×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.03 | 2.84×10−5 | 1 |

| 16 | L1564P | p.Leu1564Pro | 4810T>C | c.4691T>C | 3.30×10−3 | Tavtigian et al., 2006 | 0.03 | 1.02×10−4 | 1 |

| 16 | S1613G | p.Ser1613Gly | 4956A>G | c.4837A>G | <1.00×10−10 | Tavtigian et al., 2006 | 0.03 | <3.09×10−12 | 1 |

| 16 | P1614S | p.Pro1614Ser | 4959C>T | c.4840C>T | 2.27×10−9 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.03 | 7.03×10−11 | 1 |

| 16 | M1628T | p.Met1628Thr | 5002T>C | c.4883T>C | 1.60×10−4 | Tavtigian et al., 2006 | 0.03 | 4.95×10−6 | 1 |

| 16 | P1637L | p.Pro1637Leu | 5029C>T | c.4910C>T | 2.03×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.03 | 6.27×10−5 | 1 |

| 16 | M1652I | p.Met1652Ile | 5075G>A | c.4956G>A | 4.80×10−4 | Osorio A et al., 2007 | 0.03 | 1.48×10−5 | 1 |

| 16 | M1652T | p.Met1652Thr | 5074T>C | c.4955T>C | 2.68×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.29 | 1.10×10−4 | 1 |

| 16 | F1662S | p.Phe1662Ser | 5104T>C | c.4985T>C | 5.21×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.03 | 1.61×10−4 | 1 |

| 17 | E1682K | p.Glu1682Lys | 5163G>A | c.5044G>A | 3.15×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.03 | 9.76×10−5 | 1 |

| 17 | T1685A | p.Thr1685Ala | 5172A>G | c.5053A>G | 107.00 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.66 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 17 | T1685I | p.Thr1685Ile | 5173C>T | c.5054C>T | 140.00 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 17 | V1688del | p.Val1688del | 5181del3 | c.5181_5183delGTT | 268.00 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 17 | M1689R | p.Met1689Arg | 5185T>G | c.5066T>G | 46.00 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.66 | 0.989 | 4 |

| 18 | R1699Q | p.Arg1699Gln | 5215G>A | c.5096G>A | 142.00 | Chenevix-Trench et al., 2006 | 0.66 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 18 | R1699W | p.Arg1699Trp | 5214C>T | c.5095C>T | 4.00×104 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 18 | G1706A | p.Gly1706Ala | 5236G>C | c.5117G>C | 2.55×10−5 | Lovelock et al., 2006 | 0.66 | 4.95×10−5 | 1 |

| 18 | G1706E | p.Gly1706Glu | 5236G>A | c.5117G>A | 589.00 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 18 | A1708E | p.Ala1708Glu | 5242C>A | c.5123C>A | 2.11×1012 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 18 | S1715R | p.Ser1715Arg | 5262A>C | c.5143A>C | 45.00 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.81 | 0.99 | 5 |

| 19 | T1720A | p.Thr1720Ala | 5277A>G | c.5158A>G | 1.11×10−11 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.03 | 3.44×10−13 | 1 |

| 20 | G1738R | p.Gly1738Arg | 5331G>A | c.5212G>A | 114.00 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 20 | R1751Q | p.Arg1751Gln | 5371G>A | c.5252G>A | 6.67×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.03 | 2.06×10−4 | 1 |

| 21 | L1764P | p.Leu1764Pro | 5410T>C | c.5291T>C | 350.00 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.29 | 0.99 | 5 |

| 21 | I1766S | p.Ile1766Ser | 5416T>G | c.5297T>G | 139.00 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.66 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 21 | M1775K | p.Met1775 Lys | 5443T>A | c.5324T>A | 235.00 | Tischkowitz et al., 2008 | 0.66 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 21 | M1775R | p.Met1775Arg | 5443T>G | c.5324T>G | >1000 | Carvalho et al., 2007 | 0.66 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 21 | P1776H | p.Pro1776His | 5446C>A | c.5327C>A | 1.04 | Spearman et al., 2008 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 2 |

| 22 | C1787S | p.Cys1787Ser | 5478T>A | c.5359T>A | 2032.80 | Goldgar et al., 2004 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 22 | G1788V | p.Gly1788Val | 5482G>T | c.5363G>T | 7054.00 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 23 | V1804D | p.Val1804Asp | 5530T>A | c.5411T>A | 1.21×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.03 | 3.74×10−5 | 1 |

| 24 | V1838E | p.Val1838Glu | 5632T>A | c.5513T>A | 3973.97 | Spurdle et al., 2008 | 0.66 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 24 | I1858L | p.Ile1858Leu | 5691A>C | c.5572A>C | 2.25×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.03 | 6.97×10−5 | 1 |

| 24 | P1859R | p.Pro1859Arg | 5695C>G | c.5576C>G | 3.35×10−5 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.03 | 1.04×10−6 | 1 |

VUS shown to result in aberrant gene splicing

GenBank Reference BRCA1 U14680.1

Nucleotide numbering in “HGVS: DNA level” reflects cDNA numbering with +1 corresponding to the A of the ATG translation initiation codon in the reference sequence, according to journal guidelines (www.hgvs.org/mutnomen). The initiation codon is codon 1.

Nucleotide numbering in “BIC-DNA level” refers to the original nomenclature for BRCA1 and BRCA2 before adoption of HGVS standards where BRCA1 +119 and BRCA2 +228 correspond to the A of the ATG translation initiation codons in the reference sequence.

Table 5. BRCA2 VUS Classified as Class 1, 2 or Class 4, 5.

| BRCA2 exon | Codon | HGVS: protein level | BIC: DNA level | HGVS: DNA level | Odds in favor of causality | Reference | Prior Probability of being deleterious | Posterior Probability of being deleterious | IARC Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | R18H | p.Arg18His | 281G>A | c.53G>A | 0.01 | Spurdle et al., 2008 | 0.03 | 3.50×10−4 | 1 |

| 3 | Y42C | p.Tyr42Cys | 353A>G | c.125A>G | 5.96×10−17 | Goldgar et al., 2004 | 0.02 | 1.22×10−18 | 1 |

| 3 | N56T | p.Asn56Thr | 395A>C | c.167A>C | 1.50×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 3.06×10−6 | 1 |

| 3 | A75P | p.Ala75Pro | 451G>C | c.223G>C | 4.55×10−7 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 9.28×10−9 | 1 |

| 6 | P168T | p.Pro168Thr | 730C>A | c.502C>A | 1.55×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 3.16×10−5 | 1 |

| 10 | N319T | p.Asn319Thr | 1184A>C | c.956A>C | 0.02 | Farrugia et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 4.01×10−4 | 1 |

| 10 | S326R | p.Ser326Arg | 1206C>A | c.978C>A | 0.03 | Spearman et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 5.83×10−4 | 1 |

| 10 | N372H | p.Asn372His | 1342C>A | c.1114C>A | 1.00×10−7 | Farrugia et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 2.04×10−9 | 1 |

| 10 | P375S | p.Pro375Ser | 1351C>T | c.1123C>T | 3.17×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 6.48×10−5 | 1 |

| 10 | S384F | p.Ser384Phe | 1379C>T | c.1151C>T | 2.08×10−2 | Chenevix-Trench et al., 2006 | 0.02 | 4.24×10−4 | 1 |

| 10 | E462G | p.Glu462Gly | 1613A>G | c.1385A>G | 1.44×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 2.93×10−6 | 1 |

| 10 | A487E | p.Ala487Glu | 1688C>A | c.1440C>A | 0.17 | This manuscript | 0.02 | 3.52×10−3 | 2 |

| 10 | K513R | p.Lys513Arg | 1766A>G | c.1538A>G | 9.26×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.89×10−4 | 1 |

| 10 | N517S | p.Asn517Ser | 1778A>G | c.1550A>G | 1.28 | Spearman et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 2.54×10−2 | 2 |

| 10 | C554W | p.Cys554Trp | 1890T>G | c.1662T>G | 1.94×10−5 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 3.96×10−7 | 1 |

| 10 | T582P | p.Thr582Pro | 1972A>C | c.1744A>C | 1.10×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 2.24×10−5 | 1 |

| 10 | N588D | p.Asn588Asp | 1990A>G | c.1762A>G | 1.52 | Spearman et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 3.00×10−2 | 2 |

| 10 | G602R | p.Gly602Arg | 2032G>A | c.1804G>A | 4.95×10−5 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.01×10−7 | 1 |

| 10 | K607T | p.Lys607Thr | 2048A>C | c.1820A>C | 0.26 | Spurdle et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 5.28×10−3 | 2 |

| 10 | T630I | p.Thr630Ile | 2117C>T | c.1889C>T | 5.95×10−6 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.21×10−7 | 1 |

| 11 | P655R | p.Pro655Arg | 2192C>G | c.1964C>G | 3.36×10−3 | Goldgar et al., 2004 | 0.02 | 6.86×10−5 | 1 |

| 11 | D806H | p.Asp806His | 2644G>C | c.2416G>C | 3.92×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 8.00×10−5 | 1 |

| 11 | V894I | p.Val894Ile | 2908G>A | c.2680G>A | 4.10×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 8.36×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | L929S | p.Leu929Ser | 3014T>C | c.2786T>C | 3.63×10−3 | Spearman et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 7.41×10−5 | 1 |

| 11 | D935N | p.Asp935Asn | 3031G>A | c.2803G>A | 2.59×10−5 | Spurdle et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 5.29×10−7 | 1 |

| 11 | N987I | p.Asn987Ile | 3188A>T | c.2960A>T | 3.63×10−3 | Spearman et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 7.41×10−5 | 1 |

| 11 | L1019V | p.Leu1019Val | 3283C>G | c.3055C>G | 3.50×10−7 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 7.14×10−9 | 1 |

| 11 | N1102Y | p.Asn1102Tyr | 3532A>T | c.3304A>T | 4.00×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 8.30×10−5 | 1 |

| 11 | S1172L | p.Ser1172Leu | 3743C>T | c.3515C>T | 1.54×10−5 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 3.15×10−7 | 1 |

| 11 | R1190W | p.Arg1190Trp | 3796C>T | c.3568C>T | 5.32×10−6 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.09×10−8 | 1 |

| 11 | G1194D | p.Gly1194Asp | 3809G>A | c.3581G>A | 3.16×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 6.46×10−5 | 1 |

| 11 | N1228D | p.Asn1228Asp | 3910A>G | c.3682A>G | 2.68×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 5.48×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | C1265S | p.Cys1265Ser | 4021T>A | c.3793T>A | 0.04 | Chenevix-Trench et al., 2006 | 0.02 | 8.81×10−4 | 1 |

| 11 | D1280V | p.Asp1280Val | 4067A>T | c.3839A>T | 1.40×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 2.86×10−5 | 1 |

| 11 | V1306I | p.Val1306Ile | 4144G>A | c.3916G>A | 3.36×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 6.85×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | I1349T | p.Ile1349Thr | 4274T>C | c.4046T>C | 4.31×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 8.80×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | D1352Y | p.Asp1352Tyr | 4282G>T | c.4054G>T | 2.12 | Spearman et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 4.14×10−2 | 2 |

| 11 | T1354M | p.Thr1354Met | 4289C>T | c.4061C>T | 3.94×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 8.03×10−5 | 1 |

| 11 | C1365Y | p.Cys1365Tyr | 4322G>A | c.4094G>A | 6.67×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.36×10−4 | 1 |

| 11 | Q1396R | p.Gln1396Arg | 4415A>G | c.4187A>G | 4.39×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 8.95×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | D1420Y | p.Asp1420Tyr | 4486G>T | c.4258G>T | 0.01 | Spearman et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 1.02×10−4 | 1 |

| 11 | K1434I | p.Lys1434Ile | 4529A>T | c.4301A>T | 2.00 | Spearman et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 4.05×10−2 | 2 |

| 11 | F1524V | p.Phe1524Val | 4798T>G | c.4570T>G | 1.02×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 2.08×10−5 | 1 |

| 11 | G1529R | p.Gly1529Arg | 4813G>A | c.4585G>A | 8.13×10−9 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.66×10−10 | 1 |

| 11 | K1690N | p.Lys1690Asn | 5298A>C | c.5070A>C | 9.52×10−6 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.94×10−7 | 1 |

| 11 | S1733F | p.Ser1733Phe | 5426C>T | c.5198C>T | 7.52×10−9 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.53×10−10 | 1 |

| 11 | S1760A | p.Ser1760Ala | 5506T>G | c.5278T>G | 0.60 | Spurdle et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 1.21×10−2 | 2 |

| 11 | G1771D | p.Gly1771Asp | 5540G>A | c.5312G>A | 7.52×10−6 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.53×10−7 | 1 |

| 11 | P1819S | p.Pro1819Ser | 5683C>T | c.5455C>T | 5.88×10−6 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.20×10−7 | 1 |

| 11 | L1904V | p.Leu1904Val | 5938C>G | c.5710C>G | 1.02×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 2.09×10−5 | 1 |

| 11 | H1918Y | p.His1918Tyr | 5980C>T | c.5752C>T | 2.82×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 5.75×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | I1929V | p.Ile1929Val | 6013A>G | c.5785A>G | 2.55×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 5.21×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | R2034C | p.Arg2034Cys | 6328C>T | c.6100C>T | 2.80×10−4 | Spearman et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 5.71×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | N2048I | p.Asn2048Ile | 6371A>T | c.6143A>T | 1.56×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 3.19×10−5 | 1 |

| 11 | H2074N | p.His2074Asn | 6448C>A | c.6220C>A | 1.54×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 3.13×10−6 | 1 |

| 11 | R2108H | p.Arg2108His | 6551G>A | c.6323G>A | 1.82×10−11 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 3.72×10−13 | 1 |

| 11 | N2113S | p.Asn2113Ser | 6566A>G | c.6338A>G | 5.72×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.17×10−11 | 1 |

| 11 | T2250A | p.Thr2250Ala | 6976A>G | c.6748A>G | 9.95×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 2.03×10−5 | 1 |

| 11 | G2274V | p.Gly2274Val | 7049G>T | c.6821G>T | 0.60 | Chenevix-Trench et al., 2006 | 0.02 | 1.17×10−2 | 2 |

| 12 | I2285V | p.Ile2285Val | 7081A>G | c.6853A>G | 1.27×10−8 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 2.60×10−10 | 1 |

| 12 | D2312V | p.Asp2312Val | 7163A>T | c.6935A>T | 2.66×10−5 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 5.43×10−7 | 1 |

| 13 | R2318Q | p.Arg2318Gln | 7181G>A | c.6953G>A | 0.13 | Chenevix-Trench et al., 2006 | 0.02 | 2.65×10−3 | 2 |

| 14 | A2351G | p.Ala2351Gly | 7280C>G | c.7052C>G | 1.38 | Spearman et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 2.74×10−2 | 2 |

| 14 | G2353R | p.Gly2353Arg | 7285G>C | c.7513G>C | 0.03 | This manuscript | 0.02 | 6.12×10−4 | 1 |

| 14 | Q2384K | p.Gln2384Lys | 7378C>A | c.7150C>A | 1.64×10−5 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 3.34×10−7 | 1 |

| 14 | L2396F | p.Leu2396Phe | 7416G>T | c.7150C>A | 9.00×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 1.84×10−4 | 1 |

| 14 | K2411T | p.Lys2411Thr | 7460A>C | c.7232A>C | 8.40×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.03 | 2.60×10−4 | 1 |

| 14 | R2418G | p.Arg2418Gly | 7480A>G | c.7252A>G | 1.13 | Spearman et al., 2008 | 0.03 | 3.38×10−2 | 2 |

| 14 | N2436I | p.Asn2436Ile | 7535A>T | c.7307A>T | 7.60×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.03 | 2.34×10−4 | 1 |

| 14 | K2446E | p.Lys2446Glu | 7564A>G | c.7336A>G | 1.27 | Walker et al., 2010 | 0.03 | 3.78×10−2 | 2 |

| 14 | K2472T | p.Lys2472Thr | 7643A>C | c.7415A>C | 5.26×10−6 | Spurdle et al., 2008 | 0.03 | 1.63×10−7 | 1 |

| 15 | T2515I | p.Thr2515Ile | 7772C>T | c.7544C>T | 2.08×10−3 | Spurdle et al., 2008 | 0.03 | 6.43×10−5 | 1 |

| 16 | P2589H | p.Pro2589His | 7994C>A | c.7766C>A | 1.48 | This manuscript | 0.03 | 0.04 | 2 |

| 17 | G2609D | p.Gly2609Asp | 8054G>A | c.7826G>A | 4.12 | This manuscript | 0.81 | 0.95 | 4 |

| 17 | W2626C | p.Trp2626Cys | 8106G>C | c.7878G>C | 48.14 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 17 | I2627F | p.Ile2627Phe | 8107A>T | c.7879A>T | 1046.43 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.29 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 17 | L2647P | p.Leu2647Pro | 8168T>C | c.7940T>C | 4.58 | Farrugia et al., 2008 | 0.81 | 0.95 | 4 |

| 17 | L2653P | p.Leu2653Pro | 8186T>C | c.7958T>C | 24.06 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.81 | 0.99 | 5 |

| 17 | #R2659K | p.Arg2659Lys | 8204G>A | c.7976G>A | 3311.30 | Farrugia et al., 2008 | 0.29 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 18 | #E2663V | p.Glu2663Val | 8216A>T | c.7988A>T | 233.00 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 18 | D2665G | p.Asp2665Gly | 8222A>G | c.7994A>G | 3.40×10−4 | This manuscript | 0.81 | 1.45×10−3 | 2 |

| 18 | M2676T | p.Met2676Thr | 8255T>C | c.8027T>C | 0.96 | This manuscript | 0.03 | 0.03 | 2 |

| 18 | L2688P | p.Leu2686Pro | 8285T>C | c.8057T>C | 4.00 | This manuscript | 0.81 | 0.95 | 4 |

| 18 | A2717S | p.Ala2717Ser | 8377G>T | c.8149G>T | 1.60×10−4 | Spurdle et al., 2008 | 0.03 | 4.95×10−6 | 1 |

| 18 | T2722R | p.Thr2722Arg | 8393C>G | c.8165C>G | 93.50 | Farrugia et al., 2008 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 18 | D2723H | p.Asp2723His | 8395G>C | c.8167G>C | 5.62×1011 | Farrugia et al., 2008 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 18 | #D2723G | p.Asp2723Gly | 8396A>G | c.8168A>G | 31.31 | Walker et al., 2010 | 0.81 | 0.99 | 5 |

| 18 | K2729N | p.Lys2729Asn | 8415G>T | c.8187G>T | 1.64×10−3 | Farrugia et al., 2008 | 0.03 | 5.04×10−5 | 1 |

| 18 | G2748D | p.Gly2748Asp | 8471G>A | c.8243G>A | 2493.78 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 18 | A2770T | p.Ala2770Thr | 8536G>A | c.8308G>A | 0.49 | Chenevix-Trench et al., 2006 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2 |

| 19 | R2787H | p.Arg2787His | 8588G>A | c.8360G>A | 1.31 | This manuscript | 0.03 | 0.04 | 2 |

| 20 | R2842H | p.Arg2842His | 8753G>A | c.8525G>A | 6.35×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.29 | 2.59×10−4 | 1 |

| 20 | E2856A | p.Glu2856Ala | 8795A>C | c.8567A>C | 3.89×10−11 | This manuscript | 0.03 | 1.20×10−12 | 1 |

| 20 | Q2858R | p.Gln2858Arg | 8801A>G | c.8573A>G | 0.62 | Spurdle et al., 2008 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 2 |

| 21 | R2888C | p.Arg2888Cys | 8890C>T | c.8662C>T | 8.03×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.03 | 2.48×10−5 | 1 |

| 21 | V2908G | p.Val2908Gly | 8951T>G | c.8723T>G | 3.91×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.66 | 7.54×10−3 | 2 |

| 22 | E2947K | p.Glu2947Lys | 9067G>A | c.8839G>A | 1.21 | Walker et al., 2010 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 2 |

| 22 | K2950N | p.Lys2950Asn | 9078G>T | c.8850G>T | 4.23×10−3 | Spurdle et al., 2008 | 0.66 | 8.14×10−3 | 2 |

| 22 | D2965H | p.Asp2965His | 9121G>C | c.8893G>C | 1.15 | This manuscript | 0.03 | 0.03 | 2 |

| 22 | V2969M | p.Val2969Met | 9133G>A | c.8905G>A | 3.56×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.03 | 1.10×10−5 | 1 |

| 22 | R2973C | p.Arg2973Cys | 9145C>T | c.8917C>T | 1.76×10−4 | Farrugia et al., 2008 | 0.03 | 5.44×10−6 | 1 |

| 24 | R3052Q | p.Arg3052Gln | 9383G>A | c.9155G>A | 2.82×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.66 | 5.45×10−3 | 2 |

| 24 | R3052W | p.Arg3052Trp | 9382C>T | c.9154C>T | 9376.00 | Farrugia et al., 2008 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 5 |

| 24 | P3063S | p.Pro3063Ser | 9415C>T | c.9187C>T | 0.73 | This manuscript | 0.03 | 0.02 | 2 |

| 24 | V3079I | p.Val3079Ile | 9463G>A | c.9235G>A | 6.47×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.03 | 2.00×10−5 | 1 |

| 25 | Y3092C | p.Tyr3092Cys | 9503A>G | c.9275A>G | 6.03×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.81 | 0.03 | 2 |

| 25 | D3095E | p.Asp3095Glu | 9513C>G | c.9285C>G | 22.59 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.66 | 0.98 | 4 |

| 25 | Y3098H | p.Tyr3098His | 9520T>C | c.9292T>C | 3.46×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.03 | 1.07×10−5 | 1 |

| 25 | N3124I | p.Asn3124Ile | 9599A>T | c.9371A>T | 7.23 | This manuscript | 0.81 | 0.97 | 4 |

| 26 | D3170G | p.Asp3170Gly | 9737A>G | c.9509A>G | 1.30×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 2.64×10−5 | 1 |

| 26 | C3198R | p.Cys3198Arg | 9820T>C | c.9592T>C | 1.80×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 3.68×10−6 | 1 |

| 27 | K3326X | p.Lys3326X | 10204A>T | c.9976A>T | 1.00×10−7 | Farrugia et al., 2008 | 0.02 | 2.04×10−9 | 1 |

| 27 | T3349A | p.Thr3349Ala | 10273A>G | c.10045A>G | 4.50×10−6 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.02 | 9.19×10−8 | 1 |

VUS shown to result in aberrant gene splicing

GenBank Reference BRCA2 NM_000059.3

Nucleotide numbering in “HGVS: DNA level” reflects cDNA numbering with +1 corresponding to the A of the ATG translation initiation codon in the reference sequence, according to journal guidelines (www.hgvs.org/mutnomen). The initiation codon is codon 1.

Nucleotide numbering in “BIC-DNA level” refers to the original nomenclature for BRCA1 and BRCA2 before adoption of HGVS standards where BRCA1 +119 and BRCA2 +228 correspond to the A of the ATG translation initiation codons in the reference sequence.

In Table 4 a total of 24 BRCA1 missense variants considered pathogenic and 96 considered not pathogenic are shown. Similarly in Table 5, 15 BRCA2 missense variants considered pathogenic and 98 considered not pathogenic are presented. We also collected data on classification of intervening sequence variants (IVS) or intronic splicing variants using the posterior probability model. In Table 6, we display 20 IVS considered Class1/2 or neutral and 20 IVS considered Class 4/5 or pathogenic. The variants classified as Class 4 or 5 in Table 6 likely result in splicing aberrations. The most recent reference for the likelihood estimates for each variant is provided in the Tables since results from older manuscripts may have been updated through the availability of additional data. Where possible, modifications have been made in the likelihood estimates to correct for inaccuracies. This is particularly important when considering the use of Pathology Data. Until recently likelihood estimates included data from loss of heterozygosity (LOH) studies in tumors carrying VUS (Chenevix-Trench, et al., 2006; Spearman, et al., 2008). However, it is now appreciated that tumors containing known pathogenic mutations can exhibit loss of the mutant instead of the wildtype allele (Beristain, et al.; Hofstra, et al.; Spurdle, et al.). For these reasons, LOH data are not included in Likelihood and posterior probability model calculations.

Table 6. Classification of BRCA1 and BRCA2 candidate splicing variants as Class 1, 2 or Class 4, 5.

| Gene | Exon | Codon | HGVS: protein level | HGVS: DNA level | BIC: DNA level | Odds in favor of causality | Reference | Prior Probability of being deleterious | Posterior Probability of being deleterious | IARC Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1 | 3 | IVS2-11delT | c.81-11delT | 200-11delT | 1.32×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.26 | 4.62×10−5 | 1 | |

| BRCA1 | 3 | IVS2-13C>G | c.81-13C>G | 200-13C>G | 8.58×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.26 | 3.01×10−4 | 1 | |

| BRCA1 | 5 | IVS5+3A>G | c.212+3A>G | 331+3A>G | 1417.00 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.26 | 1.00 | 5 | |

| BRCA1 | 6 | IVS6+7G>A | c.301+7G>A | 420+7G>A | 1.79×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.26 | 6.27×10−5 | 1 | |

| BRCA1 | 7 | IVS6-1G>C | c.302-1G>C | 421-1G>C | 72.00 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 5 | |

| BRCA1 | 7 | IVS6-3C>G | c.302-3C>T | 421-3C>G | 225.00 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.26 | 0.99 | 5 | |

| BRCA1 | 9 | IVS8-17G>T | c.548-17G>T | 667-17G>T | 9.09×10−7 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.26 | 3.19×10−7 | 1 | |

| BRCA1 | 9 | IVS9+4A>G | c.593+4A>G | 712+4A>G | 0.02 | Whiley et al., 2011 | 0.26 | 0.01 | 2 | |

| BRCA1 | 12 | IVS11-1G>A | c.4097-1G>A | 4216-1G>A | 24.00 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 5 | |

| BRCA1 | 12 | IVS11-11T>C | c.4097-11T>C | 4216-11T>C | 1.54×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.26 | 5.42×10−4 | 1 | |

| BRCA1 | 12 | IVS12+10G>C | c.4185+10G>C | 4304+10G>C | 1.25×10−3 | Easton et al., 2008 | 0.26 | 4.37×10−4 | 1 | |

| BRCA1 | 13 | IVS13+1G>A | c.4357+1G>A | 4476+1G>A | 4.82×106 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 5 | |

| BRCA1 | 15 | IVS15+1G>A | c.4675+1G>A | 4794+1G>A | 6109.20 | Whiley et al., 2011 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 5 | |

| BRCA1 | 16 | IVS15-7C>T | c.4676-7C>T | 4795-7C>T | 0.01 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.26 | 2.80×10−3 | 2 | |

| BRCA1 | 17 | IVS16-20A>G | c.4987-20A>G | 5106-20A>G | 5.62×10−7 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.26 | 1.97×10−7 | 1 | |

| BRCA1 | 17 | IVS17+1G>A | c.5074+1G>A | 5193+1G>A | 196.00 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 5 | |

| BRCA1 | 18 | IVS17-9A>T | c.5075-9A>T | 5194-9A>T | 4.59×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.26 | 1.61×10−3 | 2 | |

| BRCA1 | 18 | IVS18+1G>T | c5152+1G>T | 5271+1G>T | 1.12×107 | Spurdle et al., 2008 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 5 | |

| BRCA1 | 19 | IVS18-13A>G | c.5153-13A>G | 5272-13A>G | 1.47×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.26 | 5.17×10−5 | 1 | |

| BRCA1 | 19 | IVS18-1G>C | c.5153-1G>C | 5272-1G>C | 24.00 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 5 | |

| BRCA1 | 19 | IVS18-6C>A | c.5153-6C>A | 5272-6C>A | 2.56×10−5 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.26 | 9.01×10−6 | 1 | |

| BRCA1 | 20 | IVS19-12G>A | c.5194-12G>A | 5313-12G>A | 1.85×105 | Whiley et al., 2011 | 0.26 | 1.00 | 5 | |

| BRCA1 | 20 | IVS20+1G>A | c.5277+1G>A | 5396+1G>A | 4.31×1011 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 5 | |

| BRCA1 | 22 | IVS21-8C>T | c.5333-8C>T | 5452-8C>T | 3.19×10−3 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.26 | 1.12×10−3 | 2 | |

| BRCA1 | 23 | IVS23+5G>C | c.5467+5G>C | 5586G>C | 0.13 | Whiley et al., 2011 | 0.26 | 0.04 | 2 | |

| BRCA2 | 6 | IVS5-2A>G | c.476-2A>G | 704-2A>G | 22.00 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 5 | |

| BRCA2 | 6 | IVS6+1G>T | c.516+1G>T | 744+1G>T | 1.10 | Whiley et al., 2011 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 4 | |

| BRCA2 | 9 | IVS8-12delTA | c.791delTA | 910-12delTA | 0.01 | Spearman et al., 2008 | 0.26 | 2.80×10−3 | 2 | |

| BRCA2 | 12 | IVS11-20T>A | c.6842-20T>A | 7070-20T>A | 7.76×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.26 | 2.73×10−4 | 1 | |

| BRCA2 | 13 | IVS13+1G>C | c.7007+1G>C | 7235+1G>C | 2.45 | Whiley et al., 2011 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 4 | |

| BRCA2 | 15 | IVS14-14T>G | c.7436-14T>G | 7664G>C | 0.02 | Whiley et al., 2011 | 0.26 | 6.98×10−3 | 2 | |

| BRCA2 | 16 | IVS15-1G>A | c.7618-1G>A | 7846-1G>A | 93.20 | Whiley et al., 2011 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 5 | |

| BRCA2 | 19 | IVS19+1G>A | c.8487+1G>A | 8715+1G>A | 21.00 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 5 | |

| BRCA2 | 21 | IVS20-16C>G | c.8633-16C>G | 8861-16C>G | 0.01 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.26 | 2.12×10−3 | 2 | |

| BRCA2 | 21 | IVS21+4A>G | c.8754+4A>G | 8982+4A>G | 36.00 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.26 | 0.93 | 4 | |

| BRCA2 | 22 | IVS22+1G>T | c.8953+1G>T | 9181+1G>T | 14.06 | Whiley et al., 2011 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 5 | |

| BRCA2 | 23 | P3039P | p.Pro3039Pro | c.9117G>A | 9345G>A | 146.00 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 5 |

| BRCA2 | 25 | IVS24-1G>C | c.9257-1G>C | 9485-1G>C | 55.00 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 5 | |

| BRCA2 | 25 | IVS25+9A>C | c.9501+9A>C | 9729+9A>C | 6.44×10−4 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.26 | 2.26×10−4 | 1 | |

| BRCA2 | 27 | IVS26-20C>T | c.9649-20C>T | 9877-20C>T | 3.29×10−5 | Easton et al., 2007 | 0.26 | 1.16×10−5 | 1 |

GenBank Reference BRCA1 U14680.1

GenBank Reference BRCA2 NM_000059.3

Nucleotide numbering in “HGVS: DNA level” reflects cDNA numbering with +1 corresponding to the A of the ATG translation initiation codon in the reference sequence, according to journal guidelines (www.hgvs.org/mutnomen). The initiation codon is codon 1.

The data are also presented in an online BRCA1/BRCA2 variant LOVD classification database (http://brca.iarc.fr/LOVD). This database lists all missense variants that have been classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic (Class 4/5) and not pathogenic or likely not pathogenic (Class 1/2) using the posterior probability classification model and the same nomenclature as described here. The LOVD database will be updated and expanded as additional data become available from family studies. Here we add to the data shown in the LOVD database by presenting results for intronic variants, a subset of which disrupt splicing of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes (Table 6).

Limitations of the Posterior Probability Model

It is important to realize that there are a number of assumptions incorporated into the posterior probability model. Because of this there is the possibility that a VUS can be misclassified. For example, under the prior probability model derived from evolutionary sequence comparisons, mutations in residues conserved throughout orthologs from sea urchin to human have a much greater probability of cancer causality than mutations in poorly conserved residues. Thus, mutations in amino acids that appear to be poorly conserved, but actually have been specifically selected in certain species (gain of function), may be inappropriately assigned low prior probabilities, which often results in classification as Class 3 VUS due to limiting data from the likelihood components of the model. For this reason, the IARC working group required that other data (family, pathology or functional) had to be combined with the prior probability derived from sequence analysis before a VUS could be assigned a specific Class. Likewise, the likelihood estimates based on personal and family history are currently specific to the population screened by Myriad Genetic Laboratories in the USA before 2006. Inclusion of personal and family history data from other centers or countries depend upon re-estimation of the likelihood ratios for each phenotypic category. The posterior probability model is also limited by the availability of family data. Many VUS are found in a very small number of families, which do not generate sufficient genetic information to allow these VUS to be assigned to Class 1/2 or Class 4/5. To address this problem ENIGMA (Evidence-based Network for the Interpretation of Germline Mutant Alleles) was formed (www://enigmaconsortium.org). This worldwide consortium is focused on combining information from around the world to classify VUS. In particular the focus is on collecting information on families with specific VUS and on tumor pathology with the intent of evaluating these data and potentially classifying VUS using the posterior probability model.

Other methods for characterizing VUS

Alternative family and pathology based likelihood models

A number of other family and pathology based methods for classification of VUS are being developed. For instance other groups have developed independent likelihood-based models for evaluation of VUS identified in specific countries (Gomez Garcia, et al., 2009; Mohammadi, et al., 2009). These approaches are promising but for the moment are based on limited amounts of data. Others have used pathology data to assign pathology-based likelihood estimates. These estimates are based on very small numbers of tumors and should be applied with caution (Spearman, et al., 2008; Sweet, et al., 2010). Importantly ENIGMA is undertaking a very large study focused on re-evaluation of pathology characteristics for BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumors, which should lead to more robust likelihood estimates.

Functional assays

The development of functional assays for classification of BRCA1 and BRCA2 VUS is an area of intense activity. One approach that is focused on the BRCT domains of BRCA1 involves measuring the transcriptional activity of the domains when containing VUS. This method has been extensively cross validated and exhibits high sensitivity and specificity (Lee, et al., 2010). Recently, a computational model was developed to derive likelihood estimates for the results of this functional assay which allow the incorporation of functional assay data into the overall multifactorial likelihood and the posterior probability models (Iversen, et al., 2011). Likewise, a DNA repair assay that measures the influence of VUS located in the BRCA2 DNA binding domain on the homologous recombination activity of BRCA2 has been developed (Farrugia, et al., 2008). This assays exhibits 100% sensitivity and specificity for known pathogenic and not pathogenic variants in the DNA binding domain and may be useful for classification of VUS. Another interesting approach is the development of mouse embryonic stem cells (ES) cells that are deficient in Brca1 or Brca2 and can be used as a host to express human BRCA1 and BRCA2 VUS. Using this approach cells containing functionally proficient VUS survive while cells expressing VUS that have defective function either do not survive or survive but exhibit characteristics of BRCA1 and BRCA2 deficient cells such as sensitivity to DNA damaging agents, chromosomal instability and centrosome amplification (Chang, et al., 2009; Kuznetsov, et al., 2008).

Each of these approaches will provide important information for the classification of BRCA1 or BRCA2 VUS. It is important to note that it is still unclear how different activities of BRCA1 and BRCA2 measured in vitro are related to their tumor suppressive functions in vivo. Thus, extensive validation relative to a panel of variants classified using the posterior probability model, as was done for the BRCA1 transcriptional assay and the BRCA2 DNA repair assays, is critical for establishing the clinical utility of the results obtained. Furthermore, integration of multiple functional data sources will require detailed analysis to determine whether results from different assays are independent. Interestingly, both assays have identified variants with partial functional effects. Whether the reduced activity associated with these VUS is directly correlated with intermediate risk of cancer remains to be determined.

The increased availability of data on genetic variation in human populations has been the impetus behind the development of a large field of research activity directed at assigning pathogenicity to different alleles of cancer genes. The method detailed here emerged in this context. Ultimately, models such as the ones presented here may incorporate data from large scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and thus be able to assess risk contribution in a continuous, rather than discrete (high versus low risk), manner. This continuum may include frequent variants with small effect, low frequency variants with moderate effect and even rarer variants with large effects. We anticipate that the extension of this model to other genes will be gradual. The main impetus for evaluating variants in additional genes will be when variants become relevant in clinical practice, likely as results from a multi-gene predisposition panels. However, when extending to other genes, the inability of the model to account for high de novo mutation rates will have to be considered.

Summary

VUS will continue to be a challenge for the medical community. The multiplicity of publications focused on efforts to classify VUS highlights the lack of universally accepted reporting standards for VUS and the challenges presented by trying to establish pathogenicity or absence of pathogenicity with current methodology. Reclassification of any VUS as neutral or pathogenic will require ongoing integration of new data and modeling that incorporates multiple independent lines of evidence. Here we describe a posterior probability model that utilizes several sources of information for the purpose of VUS classification and provide Tables showing 59 pathogenic BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants and 214 non-pathogenic BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants that were classified by this method. In addition we describe ongoing efforts to classify VUS using data collected through ENIGMA and by functional assays. Systematic application of the posterior probability method is expected to increase the number of classified deleterious and neutral variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 in the near future. This article was written primarily to assist health care providers in understanding the challenges and issues in dealing with VUS and to collate new information for the BRCA1 and BRCA2 VUS for which there is emerging evidence for or against pathogenicity. It is our hope that the lists of classified VUS may assist health care providers and patients in medical decision making when faced with a VUS finding.

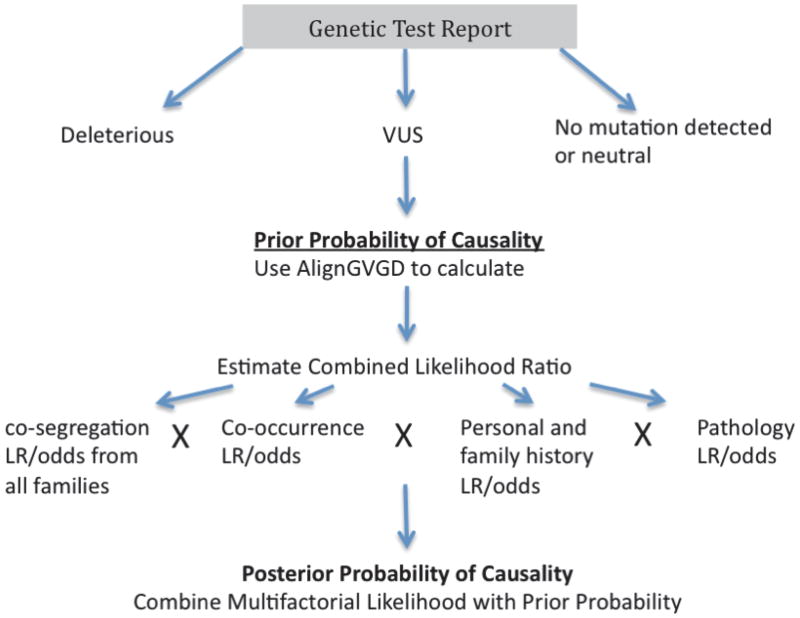

Figure 1.

Method for Determination of Posterior Probability of Causality for each VUS.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an NIH specialized program of research excellence (SPORE) in breast cancer award to the Mayo Clinic (CA116201), NIH grant R01 CA116167.

Appendix

Sources of Data

Mutation nomenclature website http://www.lovd.nl/mutalyzer/

The Breast Cancer Information Core (BIC) listing of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations http://research.nhgri.nih.gov/bic/

Literature database summarizing information on UV/VUS classification http://chromium.liacs.nl/LOVD2/cancer/home.php?select_db=BRCA1

Align-GVGD sequence based analysis identifying the Classification Class of each VUS http://agvgd.iarc.fr/

Results of multifactorial analyses of unclassified variants http://brca.iarc.fr/LOVD/

Leiden Open Variant Database (LOVD) displaying classified BRCA1 and BRCA2 VUS http://brca.iarc.fr/LOVD

ENIGMA (Evidence-based Network for the Interpretation of Germline Mutant Alleles) www://enigmaconsortium.org

Definitions of vocabulary

-

“deleterious” is short for “evolutionarily deleterious” and is most applicable to the output from alignment-based missense substitution prediction algorithms such as PolyPhen and Align-GVGD.

“damaging” is short for “damages protein function” and is most applicable to the output from functional assays.

“pathogenic” refers to disease causality.

These three terms should NOT be used interchangeably!

-

In Table 3 from Plon et al (Human Mutation 29: 1282-1291, 2008), The following definitions are used:

IARC Class 2 is “likely not pathogenic of little clinical significance”

IARC Class 1 is “not pathogenic or of no clinical significance”

Thus “not pathogenic” should be used instead of words like “neutral” or “benign” or “polymorphism”.

-

(3) Uncertain vs. unclassified

“Uncertain” implies that an analysis has been done, and the variant has a posterior probability between 5% and 95%.

“Unclassified” is the state of a variant before any effort at classification.

References

- Antoniou AC, Cunningham AP, Peto J, Evans DG, Lalloo F, Narod SA, Risch HA, Eyfjord JE, Hopper JL, Southey MC, et al. The BOADICEA model of genetic susceptibility to breast and ovarian cancers: updates and extensions. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(8):1457–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bane AL, Pinnaduwage D, Colby S, Reedijk M, Egan SE, Bull SB, O'Malley FP, Andrulis IL. Expression profiling of familial breast cancers demonstrates higher expression of FGFR2 in BRCA2-associated tumors. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2009;117(1):183–91. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0087-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beristain E, Guerra I, Vidaurrazaga N, Burgos-Bretones J, Tejada MI. LOH analysis should not be used as a tool to assess whether UVs of BRCA1/2 are pathogenic or not. Familial cancer. 2010;9(3):289–90. doi: 10.1007/s10689-009-9318-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S, Biswas K, Martin BK, Stauffer S, Sharan SK. Expression of human BRCA1 variants in mouse ES cells allows functional analysis of BRCA1 mutations. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(10):3160–71. doi: 10.1172/JCI39836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenevix-Trench G, Healey S, Lakhani S, Waring P, Cummings M, Brinkworth R, Deffenbaugh AM, Burbidge LA, Pruss D, Judkins T, et al. Genetic and histopathologic evaluation of BRCA1 and BRCA2 DNA sequence variants of unknown clinical significance. Cancer Res. 2006;66(4):2019–27. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton DF, Deffenbaugh AM, Pruss D, Frye C, Wenstrup RJ, Allen-Brady K, Tavtigian SV, Monteiro AN, Iversen ES, Couch FJ, et al. A systematic genetic assessment of 1,433 sequence variants of unknown clinical significance in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 breast cancer-predisposition genes. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(5):873–83. doi: 10.1086/521032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrugia DJ, Agarwal MK, Pankratz VS, Deffenbaugh AM, Pruss D, Frye C, Wadum L, Johnson K, Mentlick J, Tavtigian SV, et al. Functional assays for classification of BRCA2 variants of uncertain significance. Cancer Res. 2008;68(9):3523–31. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldgar DE, Easton DF, Byrnes GB, Spurdle AB, Iversen ES, Greenblatt MS. Genetic evidence and integration of various data sources for classifying uncertain variants into a single model. Hum Mutat. 2008;29(11):1265–72. doi: 10.1002/humu.20897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldgar DE, Easton DF, Deffenbaugh AM, Monteiro AN, Tavtigian SV, Couch FJ. Integrated evaluation of DNA sequence variants of unknown clinical significance: application to BRCA1 and BRCA2. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75(4):535–44. doi: 10.1086/424388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez Garcia EB, Oosterwijk JC, Timmermans M, van Asperen CJ, Hogervorst FB, Hoogerbrugge N, Oldenburg R, Verhoef S, Dommering CJ, Ausems MG, et al. A method to assess the clinical significance of unclassified variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes based on cancer family history. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11(1):R8. doi: 10.1186/bcr2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstra RM, Spurdle AB, Eccles D, Foulkes WD, de Wind N, Hoogerbrugge N, Hogervorst FB. Tumor characteristics as an analytic tool for classifying genetic variants of uncertain clinical significance. Hum Mutat. 2008;29(11):1292–303. doi: 10.1002/humu.20894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen ES, Jr, Couch FJ, Goldgar DE, Tavtigian SV, Monteiro AN. A computational method to classify variants of uncertain significance using functional assay data with application to BRCA1. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2011;20(6):1078–88. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov SG, Liu P, Sharan SK. Mouse embryonic stem cell-based functional assay to evaluate mutations in BRCA2. Nat Med. 2008;14(8):875–81. doi: 10.1038/nm.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakhani SR, Van De Vijver MJ, Jacquemier J, Anderson TJ, Osin PP, McGuffog L, Easton DF. The pathology of familial breast cancer: predictive value of immunohistochemical markers estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, HER-2, and p53 in patients with mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(9):2310–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MS, Green R, Marsillac SM, Coquelle N, Williams RS, Yeung T, Foo D, Hau DD, Hui B, Monteiro AN, et al. Comprehensive analysis of missense variations in the BRCT domain of BRCA1 by structural and functional assays. Cancer Res. 2010;70(12):4880–90. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi L, Vreeswijk MP, Oldenburg R, van den Ouweland A, Oosterwijk JC, van der Hout AH, Hoogerbrugge N, Ligtenberg M, Ausems MG, van der Luijt RB, et al. A simple method for co-segregation analysis to evaluate the pathogenicity of unclassified variants; BRCA1 and BRCA2 as an example. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:211. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plon SE, Eccles DM, Easton D, Foulkes WD, Genuardi M, Greenblatt MS, Hogervorst FB, Hoogerbrugge N, Spurdle AB, Tavtigian SV. Sequence variant classification and reporting: recommendations for improving the interpretation of cancer susceptibility genetic test results. Hum Mutat. 2008;29(11):1282–91. doi: 10.1002/humu.20880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]