Abstract

Behavioral variables are often used as performance indicators (PIs) of visual or internal distraction induced by secondary tasks. The objective of this study is to investigate whether visual distraction can be predicted by driving performance PIs in a naturalistic setting. Visual distraction is here defined by a gaze based real-time distraction detection algorithm called AttenD. Seven drivers used an instrumented vehicle for one month each in a small scale field operational test. For each of the visual distraction events detected by AttenD, seven PIs such as steering wheel reversal rate and throttle hold were calculated. Corresponding data were also calculated for time periods during which the drivers were classified as attentive. For each PI, means between distracted and attentive states were calculated using t-tests for different time-window sizes (2 – 40 s), and the window width with the smallest resulting p-value was selected as optimal. Based on the optimized PIs, logistic regression was used to predict whether the drivers were attentive or distracted. The logistic regression resulted in predictions which were 76 % correct (sensitivity = 77 % and specificity = 76 %). The conclusion is that there is a relationship between behavioral variables and visual distraction, but the relationship is not strong enough to accurately predict visual driver distraction. Instead, behavioral PIs are probably best suited as complementary to eye tracking based algorithms in order to make them more accurate and robust.

INTRODUCTION

Driver distraction is a widespread phenomenon and may contribute to numerous crashes [Gordon, 2009; Klauer, et al., 2006; Olson, et al., 2009]. It would, therefore, be both cost and safety beneficial if a distraction detection algorithm based on vehicle performance data available through the vehicle controller area network (CAN) could be developed.

Driver distraction can be defined as “the diversion of attention away from activities critical for safe driving toward a competing activity” [Lee, et al., 2009]. This is a very general definition where the diversion of attention can be visual, auditory, physical or cognitive and where the competing activity can be anything from mobile phone usage to daydreaming. Since this definition is impossible, or at least very difficult, to apply to large sets of naturalistic data where manual inspection is impractical and expensive, a more pragmatic and easily operationalized definition of driver distraction was used in this study. We were only interested in visual distraction, which is defined as not looking at what is classified to be relevant for driving. More specifically, a recently developed distraction warning system called AttenD [Kircher & Ahlstrom, 2009] was used to determine when a driver was considered to be attentive or distracted.

Distraction is often measured with eye movements [Donmez, et al., 2007; Kircher & Ahlstrom, 2009; Victor, et al., 2005; Zhang, et al., 2006] and even though the relationship between visual distraction and eye movements is self-evident, there are some general issues related to using eye movements as a predictor of driver distraction. Although the technical development of eye movement systems is occurring rapidly, it is still difficult to track a driver’s gaze accurately and precisely over a long period of time and with large coverage. Clothing, mascara, certain facial features, eye glasses, large head rotations and a number of other factors can impede tracking, and vibrations, sunglare and other situational factors can disturb the tracking equipment. So far, high-performance eye tracking systems typically used for research are still prohibitively expensive, and even one-camera systems, which have inferior performance, entail considerable costs. Last but not least, relying on a single sensor alone poses a risk because the sensor can fail, and then no backup data are available. One solution to this problem would be to establish additional indicators of visual distraction that are based on sensors other than eye tracking, preferably sensors that are already present in the vehicles.

Over the years, numerous PIs based on longitudinal and lateral vehicle control dynamics have been developed and refined in order to track effects of visual or internal distraction. Some of these PIs, such as headway or lateral position metrics, require advanced hardware. However, other PIs only require measures that are readily available on the CAN. Examples include steering wheel reversal rate [MacDonald & Hoffman, 1980] and throttle hold rate [Zylstra, et al., 2003].

The objective of this study is to investigate if visual distraction, as measured via eye movements, can be predicted by behavioral PIs in a naturalistic driving setting.

METHOD

This study is based on data acquired during an extended field study performed in 2008 [Kircher & Ahlstrom, 2009; Katja Kircher, et al., 2009]. All participants gave their informed consent, and the study was approved by the ethical committee for studies with human subjects in Linköping, Sweden. The main requirement for participation was to recruit non-professional drivers that regularly drove about 200 km per day, such as commuters. Further requirements were that the drivers should be at least 25 years of age and they should have held a valid driving license for at least seven years. In order to ensure good eye tracking results, the participants should not wear eye glasses, heavy mascara or be bearded.

Seven drivers participated in the study, four men and three women. Their mean age was 42 years (sd = 10.9 years), and they had held their driving license on average for 25 years (sd = 10.9 years). One participant did not report his age.

The test car was instrumented with an autonomous data acquisition system which logged CAN data, GPS position and video films of the forward scene and the vehicle cabin. Furthermore, the vehicle was equipped with the non-obtrusive remote eye tracker SmartEye Pro 4.0 (SmartEye AB, Gothenburg, Sweden). Two cameras observing the driver’s face were installed in the vehicle, one on the A-pillar and the other in the middle console. To ensure good eye tracking quality, the cameras were automatically recalibrated every hour based on the head model. The system logged eye movements and head movements with a frequency of 42 Hz.

Each participant drove a baseline phase lasting approximately ten days. During this time data were logged, but would-be warnings from the distraction warning system were inhibited. After the baseline phase the driver was informed that the vehicle was equipped with a distraction warning system. During the following three weeks each participant drove with AttenD activated. In both phases the participants used the car just as they would their own, without any restrictions regarding where, when or how they could drive.

Distraction Warning System

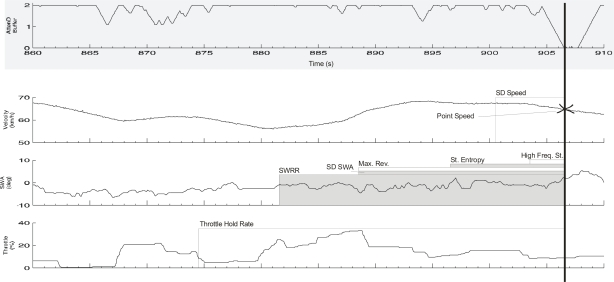

The distraction warning algorithm AttenD was developed at the Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute in cooperation with Saab Automobile AB. A short description of AttenD is included here, but detailed information can be found in Kircher and Ahlstrom [2009]. An illustration of how AttenD operates is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Example of time trace illustrating the development of the attention buffer for three consecutive one-second glances away from the field relevant for driving (FRD), marked dark gray, with half-second glances back to the FRD in between. Note the 0.1 s latency period before increasing the buffer again. A glance to the rear view mirror is exemplified between −1.8 s and 0 s, note the 1 s latency period before the buffer starts to decrease.

AttenD is based on a 3D model of the cockpit, dividing the car into different zones such as the windshield, the speedometer, the mirrors and the dashboard, and on the time the driver spends looking within these zones.

A time based attention buffer with a maximum value of two seconds is decremented over time when the driver looks away from the field relevant for driving (FRD), which is represented by the intersection between a circle of a visual angle of 90° and the vehicle windows, excluding the area of the mirrors. When the driver’s gaze resides inside the FRD, the buffer is incremented until the maximum value is reached. One-second latencies are implemented for the mirrors and the speedometer before the buffer starts decrementing. There is also a 0.1 second delay before increasing the buffer after a decrement phase. This latency is meant to reflect the adaptation phase of the eye and the mind to the new focusing distance and the driving scene. When no eye tracking but only head tracking is available, a somewhat simplified algorithm based on head direction takes over.

When the buffer reaches zero the driver is considered to be distracted, and when further conditions are met (e. g. direction indicators not activated, speed above 50 km/h, no brake activation, no extreme steering maneuvers), a warning is issued. When the buffer value is between 1.8s and 2.0s, the driver is considered to be attentive. For the AttenD algorithm, raw gaze data were used instead of fixations in order to reduce the computational complexity.

CAN Based Performance Indicators

Seven different PIs, which have been introduced in the literature as potential indicators of driver distraction, were included in this study. Each PI was calculated based on time series data from a particular time-window, see Figure 2. The size of the window is different for different PIs. In addition to the seven PIs, the speed measured at the end of each window, called point speed, was included for control purposes, since several of the other PIs depend on the point speed [Green, et al., 2007].

Figure 2.

Visualisation of the different window sizes in relation to a distraction event as defined by the AttenD algorithm. The PIs marked in grey are included in the logistic regression.

The variability in speed is an indicator of longitudinal driving behavior. Here it is represented as the standard deviation of speed, calculated in the current window (measured in km/h).

Throttle hold rate is another indicator of longitudinal driving behavior which is based on the observation that speed adaptation is diminished when the driver is distracted [Zylstra, et al., 2003]. Throttle hold rate is based on the position of the accelerator pedal (measured in per cent) according to Green et al. [2007]. If the throttle position deviated with less than 0.2% in a one-second wide sliding window, a throttle hold was marked at this particular window location. The throttle hold rate is then determined as the percentage of throttle hold instances within the current PI window. Note that two different windows are used to calculate the throttle hold rate; a shorter window which determines if there are pedal movements or not, and a longer window which determines the percentage of throttle holds.

Increased steering wheel activity has been linked to visually and cognitively distracting tasks, and a variety of steering wheel metrics have been proposed for quantifying this activity. They range from simple indicators such as the standard deviation of steering wheel angle [Liu & Lee, 2006] to more advanced metrics such as steering wheel reversal rate, high frequency steering and steering entropy. Steering wheel reversal rate (SWRR) measures the number of steering wheel reversals per minute. The steering wheel angle signal is filtered with a 2nd order Butterworth low pass filter (cut-off frequency = 0.6 Hz) before reversals that are larger than 1° are extracted according to Östlund et al. [2005]. Max steering wheel reversal is calculated alongside SWRR and is defined as the largest steering wheel reversal, measured in degrees, within the current window. High frequency steering is sensitive to variations in both primary and secondary task load [McLean & Hoffmann, 1971], and is calculated as the total power in the frequency band 0.35 – 0.6 Hz. The power spectral density of the steering wheel signal is estimated with the fast Fourier transformation and the power in the considered frequency band is calculated by numerical integration. Steering entropy represents the predictability of steering wheel movements [Boer, et al., 2005]. The steering wheel signal is down-sampled to 4 Hz and the residuals from a one-step prediction based on autoregressive modeling are used to determine the entropy. During visual distraction, corrective actions result in a less predictable steering profile and consequently a higher entropy.

Data Processing

All data preparation and processing was carried out using Matlab 7.9, except for the logistic regression and the evaluation which were carried out using SPSS 17.0. The driving behavior based PIs were calculated for each distraction event, i. e. when AttenD gave a warning (treatment) or would have given a warning (baseline), and for each attentive event, that is, when the attention buffer exceeded 1.8 seconds across the complete duration of the time window in question. In cases where several warnings occurred consecutively, and where the buffer did not reach its maximum value in between, only the first distraction event was used for the analyses. Similarly, only one attentive event was allowed between two occurrences in which the buffer value dropped below 1.8 s, and the PI window was centered in this interval. Data windows representing attentive events were not allowed to overlap with the windows resulting from distraction events. Also, the location of the largest attentive windows governed the location of the shorter windows, so that the number of windows was the same regardless of window size.

Several of the PIs that were used can be computed with different parameters, which can influence their outcome. Typical examples include cut-off frequencies for different filters, the gap size in SWRR and the choice of model order in steering entropy. In this study, parameter values suggested in the literature were used for all parameters except window size. To find an optimal window size, the PIs were calculated using sizes in the range from 2 – 40 seconds, and the size giving the largest difference between attentive and distracted was selected. T-tests were used to analyze this difference, and the optimization was carried out using data from the baseline dataset.

A logistic regression, based exclusively on the driving performance related PIs, was calculated. Based on the resulting values each event was classified as either “distracted” or “attentive”. The PIs were entered stepwise (floating forward selection), with the inclusion condition of a p-value below 0.05, and with an exclusion criterion of a p-value above 0.10. The classification threshold was set to 0.5, and the maximum number of iterations was set to 20.

The baseline dataset was used to determine the coefficients in the logistic regression equation. By doing so it was ensured that the training set was not influenced by any distraction warnings. The treatment dataset, produced by the same participants at a different point in time, was used to validate the coefficients. The possibility of splitting the baseline dataset in two subsets for (i) determination and (ii) evaluation of the coefficients was rejected, in order to avoid the risk of too few data points in each set for some of the participants.

The sensitivity and specificity of the classifier was evaluated using contingency tables, indicating the percentage of correctly and incorrectly classified events, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, indicating how the selection of the classification threshold would influence the percentage of correct classifications.

RESULTS

The seven participants provided 1644 attention windows and 1808 distraction windows during the baseline phase, according to the described procedure and specification. Corresponding figures for the treatment phase were 1931 attention windows and 1881 distraction windows, respectively. The number of attention and distraction windows differed widely between participants both in the baseline phase and in the treatment phase (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of attention and distraction cases and the mileage driven.

| Baseline dataset | Treatment dataset | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant | Attention cases | Distraction cases | Quota | Mileage (km) | Attention cases | Distraction cases | Quota | Mileage (km) |

| 1 | 219 | 182 | 1.20 | 1047 | 470 | 241 | 1.95 | 1987 |

| 2 | 277 | 277 | 1 | 3138 | 318 | 348 | 0.91 | 2299 |

| 3 | 38 | 89 | 0.43 | 708 | 90 | 203 | 0.44 | 833 |

| 4 | 210 | 58 | 3.62 | 2137 | 461 | 158 | 2.92 | 4450 |

| 5 | 764 | 1044 | 0.73 | 4290 | 346 | 684 | 0.52 | 3117 |

| 6 | 72 | 131 | 0.55 | 890 | 104 | 152 | 0.68 | 1679 |

| 7 | 64 | 25 | 2.56 | 710 | 142 | 95 | 1.48 | 3169 |

| total | 1644 | 1808 | 0.91 | 12920 | 1931 | 1881 | 1.03 | 17534 |

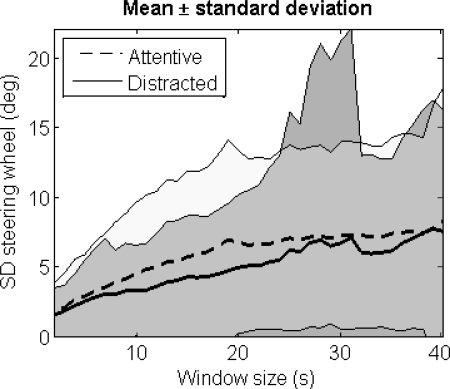

For each window size (2 – 40 seconds in 1 second intervals) and each PI, means were compared between the attentive and the distracted states using t-tests. For all PIs, a number of window sizes existed that yielded significant differences in the mean value between attentive and distracted. See Figure 3 and Figure 4 for an example plot of the standard deviation of the steering wheel angle. Even though the means do differ significantly for several window sizes (Figure 3), it is notable that the standard deviations for the two driver states overlap markedly (Figure 4). The window sizes, means, standard deviations and p-values for the optimal windows for each PI are presented in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Mean values of standard deviation of the steering wheel angle for attentive and distracted drivers (baseline data), plotted as a function of window size. The shaded areas represent the 95% confidence interval.

Figure 4.

Mean values of standard deviation of the steering wheel angle for attentive and distracted drivers (baseline data), plotted as a function of window size. The shaded areas represent the standard deviation.

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviation for each PI, where the selected window size is chosen based on the minimum p-value from a t-test between the groups distracted and attentive. The results were obtained from the baseline dataset.

| PI | Win size (s) | Mean attentive | Mean distracted | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD Speed (km/h) | 6 | 1.2±1.1 | 1.6±12.0 | <0.001 |

| SD Steering Wheel Angle (deg) | 18 | 6.1±6.0 | 4.3±4.3 | <0.001 |

| SWRR (rev/min) | 25 | 0.4±0.1 | 0.4±0.1 | <0.001 |

| Max Reversal (deg) | 18 | 18.5±20.6 | 12.7±15.3 | <0.001 |

| High Frequency Steering (deg2) | 3 | 9.7±18.6 | 8.6±30.1 | 0.03 |

| Steering Entropy (bits) | 10 | 1.37±0.12 | 1.38±0.13 | 0.04 |

| Throttle Hold Rate (%) | 32 | 0.82±0.08 | 0.81±0.08 | 0.01 |

The logistic regression on the 3452 baseline cases showed that steering entropy provided the highest explanation of variance, followed by SWRR, standard deviation of steering wheel angle and point speed (see Table 3). The variance explained did not change much when new variables were entered, and no variables were removed in the process. The resulting logistic regression coefficients are presented in Equation 1. Setting the threshold to 0.5 resulted in a sensitivity of 0.76, a specificity of 0.79 and 77.5 % correct classifications.

Table 3.

Description of the contribution of each variable entered into the logistic regression. The Wald statistic is given for entering.

| Step | PI | Wald stat. (enter) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | % Correct total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Constant | 7.8 | 100 | 0 | 52.4 |

| 1 | Steering entropy | 842.0 | 75.7 | 76.8 | 76.2 |

| 2 | SWRR | 16.3 | 75.6 | 78.8 | 77.1 |

| 3 | SD StwA | 5.4 | 75.7 | 78.5 | 77.0 |

| 4 | Point speed | 11.6 | 76.3 | 78.8 | 77.5 |

| (1) |

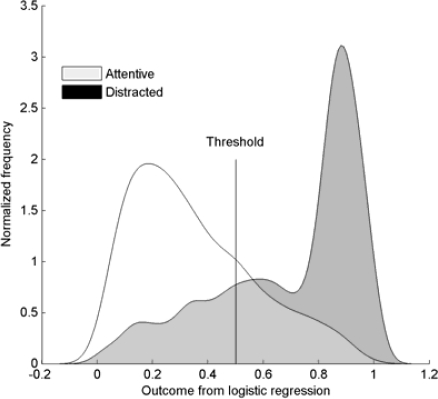

Distributions of the attentive and distracted groups for the treatment data are illustrated in Figure 5. Clearly there is an overlap between the two distributions, and depending on where the threshold is set, the classification results differ. A ROC curve is presented in Figure 6, showing the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity for different threshold values. Setting the threshold to 0.5, the percentage of correct classifications is 76.2 %, with a sensitivity of 0.77 and a specificity of 0.76. The area under the ROC curve is 0.84.

Figure 5.

Distribution of the outcome from the logistic regression for attentive and distracted drivers (treatment data).

Figure 6.

ROC Curve for the distracted/attentive classification of the baseline data. The area under the curve is 0.84.

DISCUSSION

In the present study steering entropy in conjunction with SWRR, standard deviation of steering wheel angle and point speed, allowed a classification of attentive and distracted events with an accuracy of 76 %. This result can be interpreted in many different ways. One should keep in mind that our results cannot be compared directly with other studies where driving behavior PIs were used to assess distraction. Usually driving performance data are compared for baseline driving without distraction and driving in a distracted condition, which is operationalized by the introduction of obligatory secondary tasks. In our case, however, the drivers themselves decided when to engage in distracting behavior, and their eye movements are used as indicators for visual distraction. We have, therefore, made an attempt to operationally define distracted behavior in a more objective manner, and to link driving performance data to naturalistic distraction.

If we consider for the moment that AttenD is the gold standard of driver distraction classification, we found that the driver behavior based parameters predicted distraction much better than chance, but not nearly as good as AttenD. This implies that driver performance data are a useful complement to eye tracking data, but that they cannot be used as reliably on their own. However, it is quite possible that AttenD does not provide perfect information about attentive and distracted phases. It probably has some misses and false alarms for visual distraction, and it will surely miss internal distraction, which is also assumed to influence driver behavior [Green, et al., 2007; Östlund, et al., 2005]. During internal distraction the driver’s scanning activity is often reduced, which means that the windows classified as attentive in the current study may also contain internal distraction cases. An enhancement of the algorithm, which incorporates the detection of internal distraction, should mitigate this problem. As discussed elsewhere [Kircher & Ahlstrom, 2009], it is likely that more advanced eye movement indicators will be necessary to achieve this goal.

The PIs that were significant and therefore included in the logistic regression were steering entropy, SWRR, standard deviation of steering and the current speed. Most of these have previously been identified as accurate PIs of visual and/or internal distraction. For example, steering entropy was recommended in the HASTE project [Östlund, et al., 2004] and steering wheel reversal rate was found to be the metric of choice in the AIDE project [Östlund, et al., 2005]. Point speed was also included in the final logistic regression equation, showing that the driving speed in itself is related to the occurrence of distraction events. It is a bit surprising that only lateral PIs were significant, especially since throttle hold was highly recommended in the SAVE-IT project [Green, et al., 2007].

The t-tests showed significant differences between attentive and distracted drivers for all of the optimized PIs. The standard deviation of speed increased during visually distracted driving. Speed variation is influenced by voluntary speed changes due to the road environment, by the interaction with other road users and by involuntary changes due to loss of speed control. Speed variation, therefore, is a cumbersome PI to comprehend and explain. In fact, headway metrics are generally preferred to speed variables when trying to assess longitudinal driving performance [Östlund, et al., 2005]. Such metrics, however, were not available in the current data set.

The throttle hold rate decreased with visual distraction, a result which agrees with those of Zylstra et al. [2003] but contradicts those of Green et al. [2007]. Steering wheel activity is usually higher during visual distraction [Boer, et al., 2005; Engström, et al., 2005; Green, et al., 2007; Östlund, et al., 2005] and our results support these findings in four out of five PIs. The standard deviation of steering wheel angle, however, decreased with visual distraction, and this is something that we cannot explain.

The results change noticeably if the design parameters that are used to calculate the PIs are changed. In this study, we used parameters that have been suggested in the literature (see references in the section about CAN based PIs). An exception is the window size which was optimized for the current data set. It is therefore possible that the discrepancies between our results and previously published findings are due to the differing window size used for the computation of the PIs. This parameter can clearly influence the outcome. For example, in plots similar to Figure 3 and Figure 4, it can be seen that results can change from significant to insignificant and even be reversed with the alteration of a single parameter, namely window size. The same figure provides evidence that even though the results reach significant levels, the data variability within groups is much greater than the average difference between the groups.

A common feature in many earlier studies that investigate the effect of secondary tasks on behavioral PIs is that the PIs are calculated based on data from the entire time period of the secondary task. This means that corrective actions that are performed within the time extent of the task are reflected in the PI. This also means that the changes that were found in those studies may not be useful in a real-time algorithm for distraction detection. In this study we have taken a predictive point of view, meaning that data from the past are used to predict the present state of the driver. This may be another reason why some results deviate from the literature.

It is sometimes stated that a single PI can be used to indicate a driver’s state and that data fusion of several PIs has the potential to make this classification more accurate and more robust [Y. Liang, et al., 2007; Y. L. Liang, et al., 2007]. In this study, we found that steering entropy was the PI that gave the best discrimination between visually distracted drivers and attentive drivers with 76.2 % correct classifications. By adding more PIs, the percentage of correct classifications increased marginally to 77.5%. This result supports the finding by Zhang et al. [2006] who found that many visual distraction PIs are highly intercorrelated. However, neither the study by Zhang et al. [2006] nor this study have taken full advantage of modern data fusion methodology. Logistic regression is the current standard for computing binary predictions, but more advanced techniques such as support vector machines are available. Similarly, a floating forward selection method was used for feature selection in this study, but stochastic optimization techniques such as genetic algorithms would probably be more suitable. Such approaches could also be employed to improve the optimization of design parameters for the PIs. Finally, using several data sources is not only useful to boost performance, but also to increase the robustness of the system.

For the current classification, only those cases in which the driver was distracted or fully attentive, respectively, were selected. There are, however, many in-between situations, where the AttenD buffer is below 1.8 s, but not down at zero. These cases are not included in the analysis, but it would be interesting to investigate how the obtained equation would sort the data in between distraction and full attention. This issue is left for future studies.

It is common practice to use different data sets when training and testing a classifier [Theodoridis & Koutroumbas, 2003]. In this study, baseline data were used for training (optimization of window size and determination of logistic regression coefficients) and treatment data were used for evaluation. As mentioned above, this was done to ensure that the training set was not influenced by the distraction warnings given in the treatment phase. The small number of attentive and distracted events of some participants did not allow dividing the baseline set in order to both determine and evaluate the coefficients of the logistic regression on baseline data only. Also, a split between participants was not seen as feasible, as the number of participants was small. The risk that possible outliers would affect the computations adversely was considered too big. There are a number of limitations with the used approach. Firstly, the same participants are included in both sets. This means that we have not validated the suggested parameters and coefficients for interparticipant variability in a proper manner. Secondly, the drivers may have behaved differently in the treatment phase where they are warned every time AttenD judges them to be distracted. It has to be noted, though, that the windows included in the evaluation only contain data from before the warnings. This means that there was no immediate influence of a warning on the sampled driving performance. Also, other analyses have shown that long-term behavioral changes in the treatment phase were limited [K. Kircher, et al., 2009].

Due to time and budget constraints the number of participants in the study was rather small. One way to deal with the small number of participants would be to homogenize the study population as much as possible. However, since one of the underlying objectives of the study was to evaluate methodology and equipment, large variation between the participants was chosen in order to cover a larger range of situations which were expected to cause problems (the inclusion criteria mentioned in the methodology section were mainly defined to facilitate good eye tracking results).

CONCLUSION

It can be concluded that a relationship between behavioral variables and the AttenD algorithm exists, and it is likely that both eye movements and driving behavior contributes to the detection of driver distraction. It has been shown that PIs that show significant differences in hindsight are not necessarily qualified predictors. Further research is needed on the validation of distraction detection algorithms, and further driving behavior based PIs should be investigated as to their usefulness for real-time distraction detection.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Swedish Road Administration for supporting parts of the project under the IVSS-program (Intelligent Vehicle Safety Systems). Special thanks go to Arne Nåbo and Fredrich Claezon at Saab, and SmartEye AB for support with the eye tracker.

REFERENCES

- Boer E, Rakauskas M, Ward NJ, Goodrich MA. Steering entropy revisited. Paper presented at the 3rd Int Driving Symposium on Human Factors in Driver Assessment; Rockport, Maine. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Donmez B, Boyle LN, Lee JD. Safety implications of providing real-time feedback to distracted drivers. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2007;39(3):581–590. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engström J, Johansson E, Östlund J. Effects of visual and cognitive load in real and simulated motorway driving. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour. 2005;8(2):97–120. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon CP. Crash Studies of Driver Distraction. In: Regan MA, Lee JD, Young KL, editors. Driver Distraction: Theory, effect and mitigation. London: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group; 2009. pp. 281–304. [Google Scholar]

- Green PE, Wada T, Oberholtzer J, Green PA, Schweitzer J, Eoh H. How do distracted and normal driving differ: An analysis of the ACAS naturalistic driving data. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute; 2007. (Technical Report Technical report). [Google Scholar]

- Kircher K, Ahlstrom C. Issues related to the driver distraction detection algorithm AttenD. Paper presented at the 1st International Conference on Driver Distraction and Inattention.2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kircher K, Kircher A, Ahlstrom C. Results of a Field Study on a Driver Distraction Warning System. Linköping, Sweden: VTI (Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute); 2009. (Technical report No. 639A). [Google Scholar]

- Kircher K, Kircher A, Claezon F. Distraction and drowsiness. A field study. Linköping: VTI; 2009. (VTI Report Technical report). [Google Scholar]

- Klauer SG, Dingus TA, Neale VL, Sudweeks J, Ramsey D. The impact of driver inattention on near-crash/crash risk: An analysis using the 100-car naturalistic driving study data. Washington DC: NHTSA; 2006. (Technical Report Technical report). [Google Scholar]

- Lee JD, Young KL, Regan MA. Defining Driver Distraction. In: Regan MA, Lee JD, Young KL, editors. Driver Distraction: Theory, effect and mitigation. London: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group; 2009. pp. 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y, Lee JD, Reyes ML. Nonintrusive detection of driver cognitive distraction in real time using Bayesian networks. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board. 2007;2018:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Liang YL, Reyes ML, Lee JD. Real-time detection of driver cognitive distraction using support vector machines. Ieee Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems. 2007;8(2):340–350. [Google Scholar]

- Liu BS, Lee YH. In-vehicle workload assessment: Effects of traffic situations and cellular telephone use. Journal of Safety Research. 2006;37(1):99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2005.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald WA, Hoffman ER. Review of relationships between steering wheel reversal rate and driving task demand. Human Factors. 1980;22(6):733–739. [Google Scholar]

- McLean JR, Hoffmann ER. Analysis of Drivers’ Control Movements. Human Factors. 1971;13(5):407–418. [Google Scholar]

- Olson RL, Hanowski RJ, Hickman JS, J B. Driver distraction in commercial vehicle operations. 2009. (Technical report No. FMCSA-RRT-09-042).

- Theodoridis S, Koutroumbas K. Pattern recognition. 2nd ed. San Diego, USA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Victor TW, Harbluk JL, Engström J. Sensitivity of eye-movement measures to in-vehicle task difficulty. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour. 2005;8(2):167–190. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Smith MRH, Witt GJ. Identification of real-time diagnostic measures of visual distraction with an automatic eye-tracking system. Human Factors. 2006;48(4):805–821. doi: 10.1518/001872006779166307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zylstra B, Tsimhoni O, Green PA, Mayer K. Driving performance for dialing, radio tuning, and destination entry while driving straight roads. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute; 2003. (Technical Report Technical report). [Google Scholar]

- Östlund J, Nilsson L, Carsten O, Merat N, Jamson H, Jamson S. HMI and Safety-Related Driver Performance. 2004. (Technical report). (No. GRD1/2000/25361 S12.319626) Human Machine Interface And the Safety of Traffic in Europe Project (HASTE)

- Östlund J, Peters B, Thorslund B, Engström J, Markkula G, Keinath A, et al. Driving performance assessment - methods and metrics. 2005. (Technical report). Adaptive Integrated Driver-Vehicle Interface Project (AIDE).