One of the greatest surprises revealed when the first draft of the human genome was completed in 2003 was the total number of genes, which at ~20,500 fell well below even the most conservative of estimates.1 The numerous eukaryal genomes sequenced since then have continued to confound the common-sense notion that gene number and organismal complexity should be positively correlated, with examples such as the sponge and paramecium, both of whose gene numbers exceed that of humans. A corollary of the low human gene number is that the proportion of the genome that encodes protein, at just 2%, was also lower than expected, with the remainder largely discounted as nonfunctional, or “junk DNA.” In 2005, new light was shed on these noncoding regions of the genome when both large-scale complementary DNA sequencing and genome tiling arrays revealed that the majority of these areas were transcribed into RNA.2,3 These observations raised two fundamental questions: is the transcription of noncoding regions of the genome biologically meaningful, and could noncoding RNAs reconcile the apparent disparity between gene number and complexity? In a study reported recently in Nature, Guttman and colleagues took an important step toward answering these questions by demonstrating that knockdown of the vast majority of long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) expressed in embryonic stem (ES) cells affects gene expression patterns in a manner similar to that of knockdown of well-known ES cell regulators.4

Although functionality for noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) has long been established by their roles in the translational and spliceosomal machinery, as well as for dosage compensation by imprinting of the X chromosome by the ncRNA XIST, their widespread role has remained contentious. The presence of thousands of lncRNAs was most profoundly brought to light by the large-scale complementary DNA sequencing of the mouse genome as part of RIKEN's functional annotation of the latter, which identified more than 30,000 lncRNAs.2 Subsequent transcriptomic analyses in humans have identified a comparable number of lncRNAs, with even conservative estimates rivaling the number of annotated protein-coding genes. In support of the case for widespread biological roles for lncRNAs, microarrays targeting thousands of lncRNAs revealed dynamic expression profiles of distinct subsets of lncRNAs in various developmental systems, including ES cell differentiation.5 Similarly, in situ hybridization of hundreds of lncRNAs in the adult mouse brain revealed a remarkable degree of specificity at the tissue, cell-type, and subcellular levels.6 Combined with conservation of primary sequence and splice sites,7 as well as the growing number of functionally characterized lncRNAs in the literature, it seemed increasingly likely that lncRNAs were biologically important.8 Nevertheless, counterarguments maintained that low expression levels were inconsistent with function and that experimental artifact or spurious transcription in regions of open chromatin could reconcile the occurrence of ncRNAs in transcriptomic studies.9,10

Guttman et al. tackled head-on the question regarding the extent of lncRNA functionality. Targeting 226 lncRNAs that had previously been shown to be expressed in ES cells, the team successfully knocked down the expression of 147 lncRNAs. Microarrays were then used to assess the relative impact on global gene expression profiles 4 days after knockdown. As a result, the authors found that a staggering 93% (137 of 147) of lncRNA knockdowns have a significant effect on gene expression. In further characterizing the roles of the lncRNA knockdowns in ES differentiation, they found that 26 led to increased exit from the pluripotent state and 30 produced expression patterns similar to those of specific differentiation lineages, suggesting that these lncRNAs act as repressive regulators for such differentiation.

The molecular roles of lncRNAs described to date have been highly diverse, including roles in forming nuclear structures, regulation of alternative splicing, and directing imprinting, and are therefore unlikely to share any unifying mechanism.11,12 However, increasing evidence suggests that a significant proportion are involved in chromatin remodeling and are speculated to recruit generic chromatin-modifying complexes to specific regions in the genome.13 With this concept in mind, the authors screened antibodies against 28 chromatin complexes and found 74 lncRNAs associated with 11 different complexes. These results provide further support that many lncRNAs exert their regulatory function in trans through interaction with epigenetic modifying machinery. Nevertheless, this forms just one aspect of the diverse functional repertoire of lncRNAs. Another significant emerging theme in lncRNA function is a cis-acting role in facilitating enhancer activity. Several studies have demonstrated that enhancers are transcribed by RNA polymerase II and that this expression activates gene expression.14,15 Given the diverse biochemical characteristics of RNA, in terms of both its structural and catalytic properties, as well as the large range of lncRNAs sizes, which can range from hundreds to tens of thousands of nucleotides, it is likely that we have only begun to uncover the possible mechanisms through which lncRNAs can act.

Given the remarkable proportion of lncRNAs that impart measurable phenotypes and increasing numbers with demonstrated regulatory roles in controlling gene expression, it is opportune to reflect upon the tens of thousands of lncRNAs that have been identified to date in the mammalian transcriptome. In consideration of the high functional validation rate in ES cell–expressed lncRNAs, it is reasonable to expect that lncRNAs expressed in other biological systems will reveal similar degrees of functionality. This realization has a profound impact on the manner by which the genome imparts information to the cell and how we interpret and design genome-wide studies. In light of genome-wide association studies revealing that the majority of disease- or other phenotype-associated regions fall within noncoding areas of the genome, it is particularly pertinent to consider whether these regions encode lncRNAs or other classes of ncRNAs. Furthermore, the scarce annotation of lncRNAs in public databases means that lncRNAs are poorly represented on exome arrays. Consequently, the wide-scale deployment and application of exome arrays is likely to be premature, as their coverage of the functional components of the genome is not as comprehensive as is widely perceived.

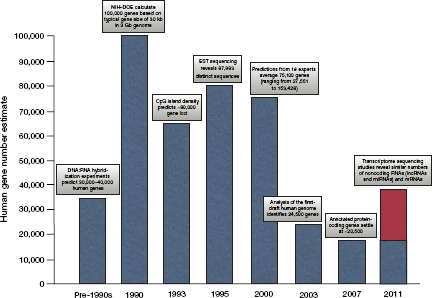

The traditional definition of a gene is a sequence of DNA that occupies a specific location on a chromosome and determines a particular characteristic of an organism. In light of the rapidly expanding proportion of lncRNAs that are functional, it is clear that the gene number of ~20,500 announced in 2007, when it was defined as including only protein-coding genes, no longer serves as a meaningful count of functional genetic loci. Indeed, the predominantly protein-centric view of genes may soon be overturned as the number of functional noncoding genes can by most reasonable measures be anticipated to outnumber protein-coding genes in the near future. Because lncRNAs often show remarkably specific expression profiles, both temporally and spatially, it is unlikely that transcriptomic sequencing efforts to date will have mapped the true breadth of noncoding expression in the genome. Therefore, earlier estimates of gene numbers may ultimately prove to have been on the mark after all (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The rise and fall (and rise) of human gene counts. Estimates of human gene numbers have varied dramatically over the past few decades.16 The considerable variation in gene counts can be accounted for largely by differences in gene definition. Earlier estimates involving hybridization and expressed sequence tag (EST) sequences did not discriminate between coding and noncoding RNAs, whereas the stricter definition of gene counts introduced in 2007 considered only protein-coding genes. Further apparent disagreement in gene numbers arises as a result of genes being defined as independent loci versus distinct sequences. When we consider the introduction of noncoding RNAs as genes, the number of distinct loci returns to early estimates of ~30,000–40,000. lncRNA, long noncoding RNA; mRNA, messenger RNA; miRNA, microRNA; NIH–DOE, National Institutes of Health–Department of Energy.

From a therapeutic perspective, the expansion of gene numbers provides a wealth of new opportunities. A preponderance of new technologies are becoming available that provide generic approaches to targeting specific RNAs. Indeed, given the specificity of ncRNA expression, their targeting may also be harnessed to yield more specific outcomes. Although the task ahead of dissecting the function of thousands of new genes is daunting, having a substantially more complete picture of the regulatory architecture underpinning our normal function and development will herald a new era in understanding the molecular basis of disease and offer the potential of a world of new therapeutic possibilities.

References

- Pennisi E. Genetics. Working the (gene count) numbers: finally, a firm answer. Science. 2007;316:1113. doi: 10.1126/science.316.5828.1113a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carninci P, Kasukawa T, Katayama S, Gough J, Frith MC, Maeda N.et al. (2005The transcriptional landscape of the mammalian genome Science 3091559–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J, Kapranov P, Drenkow J, Dike S, Brubaker S, Patel S.et al. (2005Transcriptional maps of 10 human chromosomes at 5-nucleotide resolution Science 3081149–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman M, Donaghey J, Carey BW, Garber M, Grenier JK, Munson G.et al. (2011lincRNAs act in the circuitry controlling pluripotency and differentiation Nature 477295–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinger ME, Amaral PP, Mercer TR, Pang KC, Bruce SJ, Gardiner BB.et al. (2008Long noncoding RNAs in mouse embryonic stem cell pluripotency and differentiation Genome Res 181433–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer TR, Dinger ME, Sunkin SM, Mehler MF., and, Mattick JS. Specific expression of long noncoding RNAs in the mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:716–721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706729105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponjavic J, Ponting CP., and, Lunter G. Functionality or transcriptional noise? Evidence for selection within long noncoding RNAs. Genome Res. 2007;17:556–565. doi: 10.1101/gr.6036807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinger ME, Amaral PP, Mercer TR., and, Mattick JS. Pervasive transcription of the eukaryotic genome: functional indices and conceptual implications. Brief Funct Genomic Proteomic. 2009;8:407–423. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elp038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MB, Amaral PP, Schlesinger FJ, Dinger ME, Taft RJ, Rinn JL.et al. (2011The reality of pervasive transcription PLoS Biol 9e1000625discussion e1001102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bakel H, Nislow C, Blencowe BJ., and, Hughes TR. Most “dark matter” transcripts are associated with known genes. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000371. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral PP, Clark MB, Gascoigne DK, Dinger ME., and, Mattick JS. lncRNAdb: a reference database for long noncoding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D146–D151. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer TR, Dinger ME., and, Mattick JS. Long noncoding RNAs: insights into function. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:155–159. doi: 10.1038/nrg2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick JS, Amaral PP, Dinger ME, Mercer TR., and, Mehler MF. RNA regulation of epigenetic processes. Bioessays. 2009;31:51–59. doi: 10.1002/bies.080099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TK, Hemberg M, Gray JM, Costa AM, Bear DM, Wu J.et al. (2010Widespread transcription at neuronal activity-regulated enhancers Nature 465182–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ørom UA, Derrien T, Beringer M, Gumireddy K, Gardini A, Bussotti G.et al. (2010Long noncoding RNAs with enhancer-like function in human cells Cell 14346–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertea M., and, Salzberg SL. Between a chicken and a grape: estimating the number of human genes. Genome Biol. 2010;11:206. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-5-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]