Abstract

Background

The measles virus (MV) interacts with two known cellular receptors: CD46 and SLAM. The transmembrane receptor CD209 interacts with MV and augments dendritic cell infection.

Methods

764 subjects previously immunized with measles-mumps-rubella vaccine were genotyped for 66 candidate SNPs in the CD46, SLAM and CD209 genes as part of a larger study.

Results

A previously detected association of the CD46 SNP rs2724384 with measles-specific antibodies was successfully replicated in this study. Increased representation of the minor allele G for an intronic CD46 SNP was associated with an allele dose-related decrease (978 vs. 522 mIU/ml, p = 0.0007) in antibody levels. This polymorphism rs2724384 also demonstrated associations with IL-6 (p = 0.02), IFN-α (p = 0.007) and TNF-α (p = 0.0007) responses. Two polymorphisms (coding rs164288 and intronic rs11265452) in the SLAM gene that were associated with measles antibody levels in our previous study were associated with IFN-γ Elispot (p = 0.04) and IL-10 responses (p = 0.0008), respectively, in this study. We found associations between haplotypes, AACGGAATGGAAAG (p = 0.009) and GGCCGAGAGGAGAG (p < 0.001), in the CD46 gene and TNF-α secretion.

Conclusion

Understanding the functional and mechanistic consequences of these genetic polymorphisms on immune response variations could assist in directing new measles and potentially other viral vaccine design, and in better understanding measles immunogenetics.

Key Words: Measles virus receptors, Single nucleotide polymorphisms, Measles vaccine immunity, SNP, CD46, SLAM, CD209, Replication study

Introduction

Host immune responses to the measles virus (MV) include early innate immune responses (activation of NK cells, secretion of type I interferons and other cytokines) and adaptive immune responses consisting of MV-specific humoral and cell-mediated immune (CMI) responses. Antibodies to the hemagglutinin (H) and fusion (F) proteins contribute to MV neutralization and are adequate for protection against infection [1,2]. In contrast, cellular immunity is important for the clearance of MV [3]. While MV vaccine induces both humoral and CMI responses, the duration of protective immunity is shorter than that of acquired immunity during infection with wild-type virus [2].

MV interacts with two known cellular receptors – CD46 (a complement regulatory protein) and SLAM (signaling lymphocyte activation molecule, CDw150) [4,5,6]. CD46 and SLAM act as cellular receptors for laboratory-adapted and vaccine strains [7,8,9], while wild-type MV strains preferentially utilize SLAM as a receptor [5,10]. CD209 does not support MV entry but acts as a pathogen recognition receptor [11]. SLAM is expressed on T-cell subsets, thymocytes, activated dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages, and some B cells [12,13], and when activated leads to T lymphocyte proliferation, IFN-γ secretion, and antibody production from B cells [13,14,15]. Macrophages and DCs also express the C-type lectin receptor CD209, often referred to as DC-SIGN, which interacts with MV and augments infection of DCs [11]. SLAM and CD209 molecules are both implicated in DC infection and dissemination of MV [16]. Vaccine and wild-type MV strains infect host cells through the interaction of MV H protein with the V domain of the SLAM receptor [5,17,18]. Only six SNPs have been previously identified in the SLAM gene [19]. MV binds with the CD46 receptor via two extracellular short consensus repeats (SCR1 and SCR2) and triggers the IFN-type I signaling pathway [20,21]. Expression of human CD46 in murine B cells increases MHC class II antigen presentation of both H and nucleocapsid (N) measles proteins suggesting an important role for the CD46 receptor in MV antigen presentation [22]. Notably, specific amino acid residues such as Arg59 in the MV-binding domain of CD46 receptor and Asn481 in the H protein of the MV are important for viral fusion and host cell entry [10,23]. Hence, genetic polymorphisms in the CD46 receptor may influence receptor kinetics and function, and therefore subsequent immune responses.

In previous work based on 346 subjects, we reported several specific polymorphisms in CD46 (rs11118580 and rs2724384) and SLAM (rs3796504 and rs164288) genes that demonstrated an allele dose-response decrease in MV (Edmonston vaccine strain) antibody response [24]. The mechanisms by which these SNPs influence antibody response is unclear, but they could potentially influence CD46 and SLAM expression levels or the ratios of different isoforms of these proteins [24].

We sought to replicate SNP associations found in that work by validating these associations in a new group of subjects. Associations between polymorphisms in the genes encoding CD46, SLAM and CD209 receptors and cellular immune responses to MV have not been reported in the literature. Because MV binding to these cellular receptors is the first step in infection and subsequently mounting an effective immune response, and because receptor function and kinetics are potentially influenced by specific point mutations in the MV binding domains, we hypothesized that SNPs in the CD46 and SLAM genes that influence MV binding or expression of these receptors may be associated with heterogeneity in humoral and CMI responses to measles vaccine. Thus, our follow-up study in a different population now allows us to study whether specific SNPs are reliable determinants of humoral immune responses to measles vaccine by replicating and confirming our prior findings. We examined associations between SNPs in the CD46, SLAM and CD209 genes and measures of measles vaccine-specific cellular (secreted cytokines and IFN-γ Elispot cytokine-producing cells) immunity in a cohort of 764 healthy subjects after receipt of two doses of measles vaccine.

Participants and Methods

Study Participants

Our study cohort comprised a large sample of 821 individuals from two independent age-stratified random cohorts of healthy schoolchildren and young adults from all socioeconomic strata in Rochester, Minn., USA. Between December 2006 and August 2007, we enrolled 440 healthy children (age 11–19 years) in Rochester, Minn., USA (cohort 1), as previously published [25,26,27,28,29]. 388 parents agreed to let their children join the current measles vaccine study, and from these children we obtained a blood sample. In November 2008–September 2009, we enrolled an additional 376 healthy children (age 11–22 years) in Rochester, Minn., USA (cohort 2), and from these 376 children we also obtained a blood sample. All 764 participants had written records of having received two doses of measles-mumps-rubella (MMR, Merck) vaccine containing the further attenuated Edmonston strain of MV. The Institutional Review Board of the Mayo Clinic approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from the parents of all children who participated in the study, as well as written assent from age-appropriate participants. Participant exclusions were made based on low genotype call rates (n = 19), leaving 745 subjects for final analysis.

Plaque Reduction Microneutralization Assay

Measles-specific neutralizing antibody levels (n = 744) were quantified using a high throughput fluorescence-based plaque reduction microneutralization (PRMN), as previously described [30,31]. Heat-inactivated sera were diluted four-fold from 1:4 to 1:4,096 in Opti-MEM (Gibco, Invitrogen Corporation), mixed with an equal volume of low passage challenge virus MVeGFP (kind gift from Dr. Cattaneo, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., USA). Serum/MV mixtures (50 μl) were transferred to a new 96-well plate and mixed with an equal volume of Vero cells in DMEM (Gibco, Invitrogen Corporation), containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, HyClone). The brightly fluorescent green plaques (syncytia) were scanned and counted on an automated Olympus IX71 fluorescent microscope using the Image-Pro Plus Software version 6.3 (MediaCybernetics). The 50% end point titer (neutralizing dose, ND50) was calculated using Karber's formula. The use of the 3rd WHO international measles antibody standard (3,000 mIU/ml, NIBSC code No. 97/648) enabled to converted ND50 values into mIU/ml [30].

Elispot Assay

IFN-γ Elispot responses were assessed by Elispot kits from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minn., USA), as previously described [31,32]. Briefly, one aliquot of 5 × 106 cryopreserved PBMCs was thawed, counted, and resuspended in RPMI medium with 5% FBS. Seven wells were plated with 2 × 105 PBMCs per subject; three wells were supplemented with MV (MOI of 0.5), three wells were supplemented with RPMI medium to serve as negative controls, and one well was supplemented with 5 μg/ml of PHA (Sigma). Plates were read with an ImmunoSpot S4 Pro Analyzer (CTL, Cleveland, Ohio, USA). The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) comparing the multiple observations per subject were 0.94 for the stimulated values, and 0.85 for the unstimulated values, indicating reasonably high levels of measurement reliability.

Secreted Cytokines

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) were performed to measure the level of seven [IL-2 (n = 739), IL-6 (n = 737), IL-10 (n = 740), IFN-α (n = 734), IFN-γ (n = 737), IFNλ-1 (n = 738), and TNF-α (n = 732)] cytokines secreted by PBMCs following in vitro stimulation with MV, as previously described [31]. The MOI and incubation time for each cytokine were as follows: IL-2, MOI = 0.5, 48 h; IL-6, MOI = 1.0, 72 h; IL-10, MOI = 0.5, 48 h; IFN-α, MOI = 1.0, 24 h; IFN-γ, MOI = 1.0, 72 h; IFNλ-1, MOI = 1.0, 72 h; TNF-α, MOI = 1.0, 24 h. Cytokines IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, IFN-γ, and TNF-α were measured using commercial kits from BD Biosciences (San Jose, Calif., USA), IFN-α was measured using kits from Mabtech (Cincinnati, Ohio, USA), and IFNλ-1 was measured using kits from R&D Systems. Cytokine-specific ICCs ranged from 0.65 (IL-2, unstimulated values) to 0.94 (IFN-α and IL-6, stimulated values).

Candidate Genes and SNP Selection

Using the same cohort of subjects, we have designed several other candidate gene studies, such as cytokine/cytokine receptor, vitamin A and D receptor, TLR and intracellular signaling genes and host antiviral genes that reflect separate and distinct specific aims, designed in advance for our ongoing population genetics study on measles vaccine response (submitted manuscripts) [31]. SNPs from two genes encoding MV receptors CD46 and SLAM and one gene encoding a pathogen recognition receptor CD209 (DC-SIGN or CLEC4G) were identified. SNPs within candidate genes, 5 kb upstream and downstream for each gene, were chosen based on the LD tagSNP selection algorithm [33] from the Hapmap Phase II (http://www.hapmap.org), Seattle SNPs (http://pga.mbt.washington.edu/) and NIEHS SNPs (http://egp.gs.washington.edu/), as previously described [24]. For each gene, we selected tagSNPs with a minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥0.05 and successful Illumina predictive genotyping scores based on a pair-wise linkage disequilibrium (LD) threshold of r2 ≥0.90 in both the Caucasian and African public source samples using ldSelect [33]. Additionally, a list of putative functional ‘obligate’ SNPs (coding: non-synonymous, synonymous and 5′ or 3′ untranslated regions, UTR) with a MAF ≥0.05 was provided to SNPPicker to choose in preference to other tagSNPs [unpubl. data]. A total of 66 SNPs were chosen based on this approach: SNPs belonging to CD46 gene (n = 20), SLAM SNPs (n = 23), and SNPs belonging to CD209 receptor protein (n = 23). The classification used for the description of the polymorphisms follows that described by den Dunnen and Antonarakis [34].

Genotyping Methods

Sixty-six SNPs from three candidate genes were included in the two custom Illumina GoldenGate SNP panels (Illumina Inc., San Diego, Calif., USA) for 1,536 and 768 SNPs as part of a larger measles vaccine immunogenetic study [31]. Samples included 764 potentially eligible subjects with adequate DNA, a Coriel trio of CEPH controls (mother: NA10859, father: NA10858, daughter: NA11875) run in duplicate for each of the nine plates, and 13 wells without DNA. The replicate and inheritance data were used to review clustering. All SNPs had Illumina design scores >0.4, and all DNA samples were genotyped following the manufacturer's protocol, as previously described [25,35].

Genotype calls were made using the Genotyping module of BeadStudio 2 application. Illumina 10% GenCall scores >0.4 and SNP call rates >95% were used as laboratory quality control thresholds. Of the 66 SNPs considered, 3 failed the laboratory quality assurance because of failure to amplify, poor clustering, or low call rates. An additional 8 SNPs were excluded due to low MAF (<0.01), yielding a total of 55 SNPs available for analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical methods described herein are similar to those carried out for our previous genetic association publications [25,31,35]. The following outcomes were examined: seven measures of MV-specific in vitro cytokine secretion (IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, IFN-α, IFN-γ, IFNλ-1, and TNF-α, each reported in pg/ml); a measure of CMI via MV-specific IFN-γ cell frequencies (evaluated as a count variable using Elispot); and levels of neutralizing antibody levels (measured in mIU/ml). Assessments of cytokine secretion resulted in five recorded values per outcome prior to stimulation with MV and five values after stimulation. In contrast, CMI resulted in three recorded values prior to stimulation and three after stimulation. For descriptive purposes, a single response measurement per individual was obtained for each outcome by subtracting the median of the multiple unstimulated values from the median of the multiple stimulated values. Assessments of antibody levels resulted in only one recorded value per individual. Data based on these summary measures were descriptively summarized across individuals using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and medians and quartiles for continuous variables.

Observed genotypes were used to estimate allele frequencies for each SNP and departures from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) were assessed using either a Pearson goodness-of-fit test or, for SNPs with a MAF <5%, a Fisher exact test [36]. Estimates of pair-wise LD based on the D-prime statistic were obtained using Haploview software version 3.32 [37].

SNP associations with immune response outcomes were individually evaluated using linear regression models. Separate analyses were carried out for each outcome of interest. Simple linear regression was used for measles antibody levels, which had only one measured value per individual. Repeated measures approaches were implemented for the cytokine secretion and CMI variables, simultaneously modeling the multiple observed measurements. This was achieved by including the genotype variable in the regression model, together with a variable representing stimulation status. The resulting covariate reflecting the genotype-by-stimulation status interaction was then tested for statistical significance. These repeated measures models are similar to paired t-tests, in that they compare differences between the two stimulation states within each individual among groups of individuals defined by their SNP genotypes. In these models, we allowed for within-subject correlations without imposing any constraints on the nature of the correlations, using an unstructured within-person variance-covariance matrix. Tests of association assumed an ordinal SNP effect using simple tests for trend.

To further explore genomic regions containing statistically significant single-SNP effects for one or more outcomes of interest, we performed post-hoc haplotype analyses. Posterior probabilities of all possible haplotypes for an individual, conditional on the observed genotypes, were estimated using an expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm, similar to the method outlined by Schaid et al. [38]. This information was used to define haplotype design variables that reflected the number of each of the haplotypes that were expected to be carried by each subject. Analyses were performed on these haplotype design variables using the simple least squares regression approach for antibody levels and the repeated measures approach for the cytokine secretion described above. Because of the imprecision involved in estimating the effects of low-frequency haplotypes, we considered only those occurring with an estimated frequency of >1%. Differences in immune response among common haplotypes were first assessed globally and simultaneously tested for statistical significance using a multiple degree-of-freedom test. Following these global tests, we examined individual haplotype effects. The following were performed in the spirit of Fisher's protected least significant difference test; individual associations were not considered statistically significant in the absence of global significance. Each design variable (and, for the cytokine data, stimulation status and the corresponding interaction term) was included in a separate regression analysis, effectively comparing immune response levels for the haplotype of interest against all others combined. Due to phase ambiguity, haplotype-specific medians and interquartile ranges could not be calculated. Thus, descriptive summaries were represented using the t-statistics corresponding to the haplotype main effect term for antibody levels or the haplotype-by-stimulation status interaction term for cytokine secretion.

All of the association analyses described above were adjusted for age at enrollment, race, gender, age at first measles vaccination, age at second measles vaccination, and cohort status (cohort 1 vs. cohort 2) in order to account for their potential impact on the measured immune responses. Data transformations were used to correct for data skewness in all linear regression models. An inverse normal transformation was used for all CMI outcome variables, and a log transformation was used for the antibody response measure. Because many of these SNPs have not previously been examined with regard to measles immune response, we considered all results with uncorrected p values <0.05 as potentially worthy of additional follow-up. However, formal statistical significance was determined after consideration of the number of statistical tests using a Bonferroni correction. All statistical tests were two-sided and, unless otherwise indicated, all analyses were carried out using the SAS software system (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, N.C., USA).

Results

Characteristics of Study Participants

The demographic characteristics of the study subjects are presented in table 1. The median age of the study cohort was 15 years. The majority of the cohort was Caucasian (n = 598, 80.3%) with 56% males; 11.9% (n = 89) were African-Americans, and all subjects were vaccinated with the age-recommended two doses of MMR vaccine. The median age at the first and second immunization was 15 months and 5 years, respectively. Median values (25th, 75th percentiles) for all laboratory measures of measles vaccine immunity results (neutralizing antibodies, IFN-γ Elispot, IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, IFN-α, IFN-γ, IFNλ-1, and TNF-α) are indicated in table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study population (n = 745)

| Median age at enrollment, years (IQR) | 15.0 (13.0; 17.0) |

| Median age at first measles immunization months (IQR) | 15.0 (15.0; 16.0) |

| Median age at second measles immunization years (IQR) | 5.0 (4.0; 11.0) |

| Median time from second measles immunization to enrollment, years (IQR) | 7.5 (5.6; 9.2) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 417 (56.0) |

| Female | 328 (44.0) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Non-white | 147 (19.7) |

| White | 598 (80.3) |

| Cohort, n (%) | |

| Cohort 1 | 372 (49.9) |

| Cohort 2 | 373 (50.1) |

IQR = Interquartile range within first to third quartile.

Table 2.

Immunological variables of the study subjects

| Antibody, mIU/ml (n = 744) | 846.0 (418.0; 1,772.2) |

| IFN-γ Elispot, SFC per 2 × 105 cellsa (n = 707) | 36 (12; 69) |

| Cytokine responseb pg/ml | |

| IL-2 (n = 739) | 37.5 (20.5; 64.2) |

| IL-6 (n = 737) | 354.5 (248.1; 461.4) |

| IL-10 (n = 740) | 18.1 (11.3; 28.3) |

| IFN-α (n = 734) | 551.3 (272.8; 1,025.3) |

| IFN-γ (n = 737) | 67.1 (34.9; 119.7) |

| IFNX-1 (n = 738) | 34.0 (14.1; 73.5) |

| TNF-α (n = 732) | 13.6 (9.2; 18.8) |

All results are in median (IQR within first to third quartile).

IQR = Interquartile range; SFC = spot-forming cells.

Elispot response is defined as the subject-specific median MV-stimulated response (measured in triplicate) minus the median unstimulated response (also measured in triplicate).

Cytokine response is defined as the subject-specific median measles-stimulated response (measured in five replicates) minus the median unstimulated response (also measured in five replicates).

Associations between SNPs in CD46 and CD209 Genes and Humoral Responses

Because our study subjects were racially diverse, genotyping data were analyzed for the combined cohort of subjects (n = 745), and in addition separately for the Caucasian (n = 598) and African-American (n = 89) subgroups. Significant associations were found between two intronic SNPs (D′ = 0.01) located in the CD46 gene and measles-specific neutralizing antibody levels (table 3). Augmented representation of the minor allele G for an intronic SNP (rs2724384) of the CD46 gene was associated with an allele dose-related decrease (978 vs. 522 mIU/ml, p = 0.0007) in measles-specific antibody response. This result for rs2724384 was consistent with the data obtained in our prior measles vaccine study [24]. No associations were observed between the other 11 SNPs in the CD46 and SLAM genes and measles antibodies that were statistically significant in our previous study. The occurrence of heterozygous genotype AG for an intronic SNP (rs11118516, not previously examined) of the CD46 gene was associated with an increase in median antibody levels (1,069 vs. 807 mIU/ml, p = 0.016) compared with wild-type GG. We found associations between three promoter SNPs (rs8112310, p = 0.033; rs735239, p = 0.039, D′ = 0.87, and rs12611071, p = 0.044) located in the CD209 (DC-SIGN) gene on chromosome 19 and variations in measles antibody levels.

Table 3.

Associations between SNPs in the CD46, SLAM and CD209 genes and humoral immune response to measles vaccine in the combined, Caucasian and African-American study subjects

| Gene | SNP ID | Location/function | Geno-typea | n | Median antibody titer mIU/ml (IQR)b | p valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined cohort of subjects (n = 745) | ||||||

| CD46 | rs2724384* | intron | AA | 450 | 978 (440; 1,957) | 0.0007 |

| AG | 264 | 736 (402; 1,630) | ||||

| GG | 30 | 522 (274; 706) | ||||

| CD46 | rs11118516 | intron | GG | 647 | 807 (405; 1,723) | 0.0161 |

| GA | 92 | 1,069 (500; 2,296) | ||||

| AA | 1 | 4,505 (4,505; 4,505) | ||||

| CD209 | rs8112310 | flanking 3′ UTR | TT | 505 | 803 (401; 1,650) | 0.0333 |

| TA | 224 | 954 (433; 2,087) | ||||

| flanking 5′ UTR |

AA AA | 0 |

– |

– |

||

| CD209 | rs735239 | 360 | 962 (428; 1,929) | 0.0395 | ||

| AG | 314 | 759 (400; 1,638) | ||||

| GG | 67 | 800 (460; 1,635) | ||||

| CD209 | rs12611071 | flanking 5′ UTR | CC | 509 | 800 (400; 1,638) | 0.0444 |

| CA | 199 | 1,059 (477; 2,209) | ||||

| AA | 35 | 712 (279; 2,272) | ||||

| Caucasian subgroup (n = 598) | ||||||

| CD46 | rs2724384* | intron | AA | 344 | 996 (464; 1,943) | 0.0008 |

| AG | 227 | 782 (401; 1,638) | ||||

| GG | 27 | 533 (274; 706) | ||||

| CD209 | rs12611071 | 3′ intergenic | CC | 454 | 801 (401; 1,683) | 0.0303 |

| CA | 131 | 1,185 (523; 2,119) | ||||

| AA | 13 | 645 (329; 2,849) | ||||

| CD209 | rs8112310 | flanking 3′ UTR | TT | 450 | 803 (402; 1,685) | 0.0497 |

| TA | 139 | 1,059 (451; 2,008) | ||||

| AA | 0 | – | ||||

| African-American subgroup (n = 89) | ||||||

| CD46 | rs11118516 | intron | GG | 76 | 619 (268; 1,947) | 0.0028 |

| GA | 13 | 1,690 (848; 4,120) | ||||

| CD209 | rs4804805 | flanking 5′ UTR | AA AA | 0 64 | 1,059 (446; 2,546) | 0.0042 |

| AG | 21 | 279 (193; 531) | ||||

| GG | 4 | 1,025 (365; 1,735) | ||||

| CD209 | rs7252229 | intron | GG | 45 | 510 (251; 928) | 0.0394 |

| GC | 36 | 1,481 (532; 2,786) | ||||

| CC | 8 | 1,263 (349; 2,519) | ||||

| CD209 | rs735239 | flanking 5′ UTR | AA | 68 | 914 (334; 2,380) | |

| AG | 20 | 533 (199; 1,382) | 0.0419 | |||

| GG | 1 | 327 (327; 327) | ||||

A = Adeninę; C = cytosine; G = guanine; T = thymine; IQR = interquartile range.

A total of 55 SNPs were examined; only those found to be statistically significant (p < 0.05) were included in the table. SNP rs8112310 in the combined cohort and in the Caucasian subgroup displayed violations of H WE (p = 8.5488E−07 and p = 0.0012, respectively).

Values are presented as homozygous major allele/heterozygous/homozygous minor allele.

Values are median levels (IQR) in mIU/ml as measured by PRMN assay.

Test for trend p value from the analysis of covari-ance adjusting for age, gender, race and age of immunization. The p values are adjusted for age, gender, race (when necessary), age at the first and second MMR and cohort status (cohort 1 vs. cohort 2) using analysis of covariance methodology.

Previously reported SNP associated with measles antibodies [24].

As expected, in both the Caucasian and African-American subjects we observed reproduced associations (already identified in the combined cohort of study subjects) for the intronic SNPs in the CD46 gene rs2724384 (p = 0.0008 in the Caucasian subgroup) and rs11118516 (p = 0.003 in the African-American subgroup), and these minor alleles were associated with an allele dose-related decrease and increase, respectively, in antibody levels. Two out of the three SNPs found in the combined cohort (CD209 gene promoter rs8112310, p = 0.050, and rs12611071, p = 0.030) demonstrated associations with measles vaccine-induced humoral immune response in the Caucasian subgroup.

Associations between SNPs in the CD209 and SLAM Genes and Cellular (IFN-γ Elispot) Responses

No significant associations were observed with polymorphisms in the CD46, SLAM and CD209 genes and measles-specific IFN-γ Elispot responses in the combined cohort of subjects following measles vaccine (table 4). However, analysis of the Caucasian subjects revealed three potential associations (p ≤ 0.05) between SNPs belonging to the CD209 gene (rs8105572, p = 0.016; rs11881682, p = 0.022, and rs7252229, p = 0.047, D′ ≥ 0.87) and IFN-γ Elispot responses after measles vaccination. Intronic SNP rs7252229 in the CD209 gene was associated with antibody levels in African-American subjects (p = 0.039) and was also associated with MV-specific IFN-γ Elispot immune response in Caucasian subjects (p = 0.047). Importantly, we found an association between a coding SNP (rs164288) located in the SLAM gene and measles IFN-γ Elispot responses in African-American subjects. Specifically, major allele G for a synonymous SNP in exon 3 (rs164288, Thr→Thr at amino acid 210) of the SLAM receptor gene was associated with variations in IFN-γ Elispot responses (p = 0.038). However, we did not find any AA genotype in our African-American cohort. The previous finding (in our earlier study) [24] of an allele dose-response relationship with measles antibody levels for this coding SNP rs164288 in the SLAM gene strengthens our finding. This provides evidence for the potential role of this coding SNP in cross-regulation of humoral and IFN-γ Elispot immune responses after measles vaccine.

Table 4.

Associations between SNPs in CD46, SLAM and CD209 genes and IFN-7 Elispot immune responses to measles vaccine in the combined, Caucasian and African-American study subjects

| Gene | SNPID | Location/function | Genotypea | n | Median SFC per 2 × 105 PBMCs (IQR)b | p valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined cohort of subjects (n = 745) | ||||||

| None | ||||||

| Caucasian subgroup (n = 598) | ||||||

| CD209 | rs8105572 | in tron | GG | 435 | 36 (12; 69) | 0.0166 |

| GA | 125 | 36 (19; 73) | ||||

| AA | 0 | – | ||||

| CD209 | rs11881682 | flanking 5′ UTR | GG | 412 | 37 (12; 69) | 0.0224 |

| GA | 139 | 36 (18; 75) | ||||

| AA | 12 | 25 (19; 61) | ||||

| CD209 | rs7252229 | in tron | GG | 434 | 37 (12; 69) | 0.0471 |

| GC | 117 | 38 (19; 73) | ||||

| CC | 11 | 23 (18; 83) | ||||

| African-American subgroup (n = 89) | ||||||

| SLAM | rs164288* | coding | GG | 70 | 29 (5; 49) | 0.0375 |

| Thr210Thr | GA | 17 | 10 (2; 20) | |||

| AA | 0 | – | ||||

A = Adeninę; C = cytosine; G = guanine; SFC = spot-forming cells.

A total of 55 SNPs were examined; only those found to be statistically significant (p < 0.05) were included in the table.

Values are presented as homozygous major allele/heterozygous/homozygous minor allele.

Values are median levels (IQR) in SFC per 2 × 105 PBMCs as measured by IFN-γ Elispot.

Test for trend p value from the repeated measures analysis of covariance adjusting for age, gender, race and age of immunization. The p values are adjusted for age, gender, race (when necessary), age at the first and second MMR and cohort status (cohort 1 vs. cohort 2) using analysis of covariance methodology.

Previously reported SNP associated with measles antibodies [24],

Associations between SNPs in the CD46, SLAM and CD209 Genes and Measles-Specific Cytokine Secretion

We found 66 potential associations (p ≤ 0.05) with variations in MV-specific IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, IFN-α, IFN-γ, IFNλ-1, and TNF-α secretion levels (table 5). Twenty-two associations (p ≤ 0.01) with cytokine secretion were detected. No significant associations with measles-specific IL-2 secretion were found with polymorphisms in the CD46, SLAM or CD209 genes in both the combined cohort of subjects and in the subgroup of Caucasian subjects. In the subgroup of African-Americans, augmented representation of minor allele C for intronic SNP in the CD46 gene (rs2724382) was associated with an allele dose-related decrease in median IL-2 levels (15 vs. 29 pg/ml, p = 0.012).

Table 5.

Associations between SNPs in CD46, SLAM and CD209 genes and secreted cytokine immune responses to measles vaccine in the combined, Caucasian and African-American study subjects

| Secreted cytokine/Gene | SNPID | Location/function | Genotyp ea | n | Median, pg/ml (IQR)b | p valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-2 | ||||||

| Combined cohort of subjects (n = 745) | ||||||

| None | ||||||

| Caucasian subgroup fn = 598) | ||||||

| SLAM | rs2295614 | flanking 5′ UTR | TT | 514 | 42.4 (23.3; 66.8) | 0.0303 |

| TA | 76 | 34.4 (19.0; 65.9) | ||||

| AA | 2 | 31.5 (17.7; 45.3) | ||||

| African-American subgroup (n = 89) | ||||||

| CD46 | rs2724382 | intron | GG | 33 | 28.9 (16.8; 67.6) | 0.0117 |

| GC | 44 | 31.1 (15.3; 46.4) | ||||

| CC | 11 | 15.2 (8.4; 36.6) | ||||

| CD209 | rs8112310 | flanking 3′ UTR | TT | 24 | 25.3 (11.8; 48.6) | 0.0170 |

| TA | 62 | 30.1 (15.6; 52.8) | ||||

| AA | 0 | – | ||||

| CD46 | rs2796268 | flanking 5′ UTR | AA | 28 | 32.8 (15.3; 82.1) | 0.0282 |

| AG | 45 | 30.6 (17.2; 43.4) | ||||

| GG | 15 | 15.4 (11.3; 36.6) | ||||

| CD209 | rs4804806 | flanking 5′ UTR | GG | 33 | 36.6 (18.5; 59.2) | 0.0297 |

| GA | 37 | 22.7 (12.3; 50.6) | ||||

| AA | 18 | 29.0 (15.2; 35.1) | ||||

| CD46 | rs2724385 | intron | AA | 40 | 27.2 (13.9; 51.9) | 0.0331 |

| AT | 44 | 27.9 (15.9; 46.4) | ||||

| TT | 4 | 44.1 (33.8; 75.2) | ||||

| SLAM | rs3766362 | intron | AA | 30 | 15.7 (11.3; 46.6) | 0.0381 |

| AT | 38 | 29.0 (17.0; 52.8) | ||||

| TT | 20 | 36.7 (22.8; 47.7) | ||||

| SLAM | rs6704124 | intron | GG | 52 | 25.6 (12.2; 43.2) | 0.0412 |

| GA | 30 | 29.8 (17.0; 52.8) | ||||

| AA | 6 | 43.6 (18.5; 65.6) | ||||

| IL-6 | ||||||

| Combined cohort of subjects (n = 745) | ||||||

| CD46 | rs2796267 | flanking 5′ UTR | AA | 270 | 359.3 (257.6; 479.8) | 0.0006 |

| AG | 343 | 353.8 (236.4; 458.3) | ||||

| GG | 123 | 341.2 (245.2; 446.9) | ||||

| CD46 | rsllll8516 | intron | GG | 640 | 361.2 (253.7; 469.7) | 0.0133 |

| GA | 92 | 305.4 (206.7; 401.0) | ||||

| AA | 1 | 348.1 (348.1; 348.1) | ||||

| CD46 | rs2724384* | intron | AA | 447 | 348.4 (245.8; 458.0) | 0.0275 |

| AG | 260 | 365.5 (253.5; 470.1) | ||||

| GG | 30 | 381.6 (269.5; 498.4) | ||||

| CD46 | rs41316827 | intron | CC | 710 | 354.6 (248.4; 461.4) | 0.0493 |

| CA | 26 | 348.5 (221.0; 469.5) | ||||

| AA | 1 | 332.2 (332.2; 332.2) | ||||

| Caucasian subgroup (n = 598) | ||||||

| CD46 | rs2796267 | flanking 5′ UTR | AA | 203 | 356.2 (254.6; 469.5) | 0.0042 |

| AG | 281 | 351.3 (240.2; 457.6) | ||||

| GG | 107 | 351.5 (218.4; 454.9) | ||||

| African-American subgroup (n = 89) | ||||||

| CD46 | rsllll8516 | intron | GG | 75 | 348.9 (247.8; 462.4) | 0.0012 |

| GA | 13 | 295.5 (224.9; 303.5) | ||||

| AA | 0 | – | ||||

| CD46 | rs2796267 | flanking 5′ UTR | AA | 45 | 358.9 (287.6; 479.8) | 0.0180 |

| AG | 34 | 304.3 (230.9; 418.9) | ||||

| GG | 9 | 286.1 (269.5; 295.5) | ||||

| CD209 | rs4804806 | flanking 5′ UTR | GG | 33 | 364.9 (269.8; 480.9) | 0.0254 |

| GA | 37 | 318.4 (230.7; 399.8) | ||||

| AA | 18 | 321.9 (247.8; 436.0) | ||||

| SLAM | rs2753260 | intron | AA | 51 | 340.2 (262.5; 477.6) | 0.0313 |

| AC | 32 | 314.3 (227.8; 382.1) | ||||

| CC | 5 | 358.9 (238.7; 370.6) | ||||

| IL-10 | ||||||

| Combined cohort of subjects (n = 745) | ||||||

| None | ||||||

| Caucasian subgroup (n = 598) | ||||||

| CD209 | rsl2611071 | flanking 5′ UTR | CC | 452 | 17.8 (11.9; 28.2) | 0.0246 |

| CA | 129 | 19.8 (12.4; 30.2) | ||||

| AA | 13 | 21.4 (17.4; 29.6) | ||||

| African-American subgroup (n = 89) | ||||||

| SLAM | rsl 1265452* | intron | GG | 31 | 12.1 (7.4; 22.2) | 0.0008 |

| GA | 31 | 13.3 (7.4; 28.6) | ||||

| AA | 26 | 13.9 (7.9; 26.2) | ||||

| SLAM | rs2089088 | intron | AA | 66 | 10.9 (7.4; 20.6) | 0.0232 |

| AC | 18 | 22.2 (12.8; 35.0) | ||||

| CC | 4 | 16.4 (10.1; 31.2) | ||||

| IFN-α | ||||||

| Combined cohort of subjects (n = 745) | ||||||

| CD46 | rs2724384* | intron | AA | 445 | 506.4 (244.5; 935.1) | 0.0068 |

| AG | 259 | 618.9 (321.8; 1,197.4) | ||||

| GG | 30 | 657.3 (344.5; 1,338) | ||||

| CD46 | rs41318019 | flanking 3′ UTR | GG | 645 | 567.2 (273.4; 1,047.4) | 0.0330 |

| GC | 87 | 509.9 (272.8; 846.6) | ||||

| CC | 2 | 262.5 (1.5; 523.5) | ||||

| CD46 | rsllll8516 | intron | GG | 637 | 559.3 (275.2; 1,025.3) | 0.0401 |

| GA | 92 | 491.2 (244.3; 1,028.8) | ||||

| AA | 1 | 210.2 (210.2; 210.2) | ||||

| CD209 | rs7250738 | flanking 5′ UTR | AA | 677 | 550.2 (264.4; 1,018.0) | 0.0427 |

| AG | 51 | 581.5 (393.3; 1,245.8) | ||||

| GG | 6 | 876.2 (271.9; 1,678.0) | ||||

| Caucasian subgroup (n = 598) | ||||||

| CD46 | rs2724384* | intron | AA | 338 | 545.8 (242.1; 955.7) | 0.0016 |

| AG | 223 | 661.9 (332.6; 1,220.6) | ||||

| GG | 27 | 703.0 (243.5; 1,338) | ||||

| CD46 | rsllll8516 | intron | GG | 521 | 593.9 (290.4; 1,093.5) | 0.0072 |

| GA | 62 | 679.1 (281.6; 1,012) | ||||

| AA | 1 | 210.2 (210.2; 210.2) | ||||

| CD46 | rs2724382 | intron | GG | 201 | 459.1 (225.1; 941.9) | 0.0084 |

| GC | 272 | 638.6 (328.2; 1,091.2) | ||||

| CC | 115 | 678.9 (312.6; 1,186.3) | ||||

| CD46 | rs2796268 | flanking 5′ UTR | AA | 196 | 462.4 (223.5; 963.9) | 0.0133 |

| AG | 269 | 639.6 (329.6; 1,101.5) | ||||

| GG | 118 | 670.4 (295.4; 1,156.1) | ||||

| CD46 | rs2796267 | flanking 5′ UTR | AA | 201 | 480.7 (219.3; 919.6) | 0.0148 |

| AG | 279 | 639.6 (328.2; 1,093.5) | ||||

| GG | 107 | 722.0 (282.5; 1,230.1) | ||||

| CD46 | rs7144 | 3′ UTR | AA | 204 | 462.4 (223.5; 951.7) | 0.0185 |

| AG | 271 | 639.6 (328.2; 1,101.5) | ||||

| GG | 113 | 661.9 (312.6; 1,156.1) | ||||

| CD209 | rsl2611071 | flanking 5′ UTR | CC | 448 | 591.9 (269.4; 1,051.6) | 0.0288 |

| CA | 127 | 581.5 (324.6; 1,093.5) | ||||

| AA | 13 | 969.6 (839.4; 1,678.0) | ||||

| African-American subgroup (n = 89) | ||||||

| SLAM | rsl7385878 | flanking 3′ UTR | GG | 47 | 293.6 (199.1; 535.4) | 0.0163 |

| GA | 35 | 450.6 (212.2; 805.2) | ||||

| AA | 6 | 621.8 (515; 1,109.3) | ||||

| SLAM | rs2295614 | flanking 5′ UTR | TT | 79 | 400.1 (212.2; 608.7) | 0.0253 |

| TA | 8 | 437.0 (241.5; 722.8) | ||||

| AA | 1 | 1,571.2 (1,571.2; 1,571.2) | ||||

| CD209 | rs4804805 | flanking 5′ UTR | AA | 63 | 293.6 (195.1; 546.9) | 0.0260 |

| AG | 21 | 550.3 (430.5; 1,173.4) | ||||

| GG | 4 | 506.6 (301.7; 636.0) | ||||

| SLAM | rs5002947 | flanking 3′ UTR | GG | 35 | 293.6 (162.5; 608.7) | 0.0396 |

| GA | 45 | 400.1 (253.5; 580.9) | ||||

| AA | 8 | 621.8 (488.8; 1,141.3) | ||||

| CD46 | rs41317049 | intron | AA | 80 | 417.5 (243.5; 659.4) | 0.0480 |

| AC | 7 | 321.8 (202.2; 498.1) | ||||

| CC | 0 | – | ||||

| IFN-γ | ||||||

| Combined cohort of subjects (n = 745) | ||||||

| SLAM | rs2295614 | flanking 5′ UTR | TT | 628 | 68.7 (36.9; 120.5) | 0.0128 |

| TA | 101 | 58.9 (23.5; 118.2) | ||||

| AA | 5 | 70.4 (13.1; 75.9) | ||||

| CD46 | rs2796267 | flanking 5′ UTR | AA | 270 | 63.6 (35.2; 123.3) | 0.0174 |

| AG | 343 | 66.7 (32.4; 112.2) | ||||

| GG | 123 | 76.4 (40.7; 131.4) | ||||

| Caucasian subgroup (n = 598) | ||||||

| None | ||||||

| African-American subgroup (n = 89) | ||||||

| CD209 | rs4804806 | flanking 5′ UTR | GG | 33 | 62.2 (26.0; 109.2) | 0.0007 |

| GA | 37 | 53.4 (31.1; 75.4) | ||||

| AA | 18 | 49.6 (14.4; 136) | ||||

| CD46 | rs2796268 | flanking 5′ UTR | AA | 28 | 46.6 (29.1; 133.1) | 0.0012 |

| AG | 45 | 62.8 (42.5; 97.8) | ||||

| GG | 15 | 38.9 (6.4; 69.5) | ||||

| CD46 | rs2724382 | intron | GG | 33 | 48.2 (28.2; 115.4) | 0.0072 |

| GC | 44 | 62.0 (34.5; 97.2) | ||||

| CC | 11 | 56.0 (6.2; 135.3) | ||||

| SLAM | rs2295614 | flanking 5′ UTR | TT | 79 | 57.3 (25.5; 105.2) | 0.0158 |

| TA | 8 | 61.4 (47.8; 101.9) | ||||

| AA | 1 | 70.4 (70.4; 70.4) | ||||

| CD46 | rs2796267 | flanking 5′ UTR | AA | 45 | 60.1 (30.1; 115.4) | 0.0204 |

| AG | 34 | 61.5 (26.1; 96.7) | ||||

| GG | 9 | 50.5 (24.5; 59.0) | ||||

| CD46 | rs2724385 | intron | AA | 40 | 56.2 (17.6; 82.3) | 0.0358 |

| AT | 44 | 61.5 (39.4; 118.8) | ||||

| TT | 4 | 60.6 (13.6; 167.0) | ||||

| CD46 | rs!7006738 | intron | GG | 63 | 57.3 (26.0; 97.8) | 0.0473 |

| GA | 23 | 61.3 (28.2; 139.3) | ||||

| AA | 2 | 32.5 (3.5; 61.4) | ||||

| IFNλ-1 | ||||||

| Combined cohort of subjects (n = 745) | ||||||

| SLAM | rs2295614 | flanking 5′ UTR | TT | 629 | 33.1 (14.2; 72.4) | 0.0027 |

| TA | 101 | 39.9 (14.2; 87.5) | ||||

| AA | 5 | 51.5 (−2.8; 126.8) | ||||

| CD46 | rs2724382 | intron | GG | 266 | 32.0 (12.6; 69.6) | 0.0443 |

| GC | 341 | 33.3 (14.8; 73.5) | ||||

| CC | 131 | 40.3 (17.1; 86.7) | ||||

| Caucasian subgroup (n = 598) | ||||||

| CD209 | rsl2611071 | flanking 5′ UTR | CC | 452 | 37.5 (15.0; 73.1) | 0.0027 |

| CA | 127 | 44.5 (22.6; 85.7) | ||||

| AA | 13 | 73.0 (36.2; 137.7) | ||||

| SLAM | rs2295614 | flanking 5′ UTR | TT | 512 | 39.3 (17.0; 76.2) | 0.0083 |

| TA | 76 | 40.6 (16.8; 91.1) | ||||

| AA | 2 | 188.8 (51.5; 326.1) | ||||

| CD209 | rs7248637 | 3′ UTR | GG | 492 | 38.7 (16.5; 75.7) | 0.0465 |

| GA | 92 | 40.2 (21.3; 86.0) | ||||

| AA | 6 | 71.2 (61.2; 163.9) | ||||

| African-American subgroup (n = 89) | ||||||

| SLAM | rs!7385878 | flanking 3′ UTR | GG | 47 | 13.1 (3.0; 24.9) | 0.0198 |

| GA | 35 | 25.6 (−5.7; 48.8) | ||||

| AA | 6 | 42.0 (21.5; 64.3) | ||||

| TNF-α | ||||||

| Combined cohort of subjects (n = 745) | ||||||

| CD46 | rs2724384* | intron | AA | 444 | 13.0 (8.5; 18.5) | 0.0007 |

| AG | 258 | 14.6 (10.1; 18.8) | ||||

| GG | 30 | 16.8 (11.0; 22.9) | ||||

| CD46 | rs7144 | 3′ UTR | AA | 264 | 12.8 (8.4; 17.6) | 0.0020 |

| AG | 339 | 14.0 (9.3; 18.8) | ||||

| GG | 129 | 15.2 (10.7; 20.9) | ||||

| CD46 | rs2724385 | intron | AA | 192 | 14.0 (10.1; 20.3) | 0.0030 |

| AT | 357 | 14.1 (9.1; 18.8) | ||||

| TT | 182 | 12.9 (8.8; 16.9) | ||||

| CD46 | rs2796268 | flanking 5′ UTR | AA | 251 | 12.9 (8.3; 18.3) | 0.0048 |

| AG | 337 | 13.9 (9.4; 18.8) | ||||

| GG | 138 | 14.9 (10.5; 20.4) | ||||

| CD46 | rs2724382 | intron | GG | 263 | 12.9 (8.4; 17.9) | 0.0143 |

| GC | 340 | 14.0 (9.3; 18.8) | ||||

| CC | 129 | 15.0 (10.6; 20.4) | ||||

| Caucasian subgroup (n = 598) | ||||||

| CD46 | rs2724384* | intron | AA | 337 | 13.1 (8.9; 18.2) | 2.3104E−05 |

| AG | 223 | 15.2 (10.3; 18.9) | ||||

| GG | 27 | 17.6 (11.0; 22.9) | ||||

| CD46 | rs7144 | 3′ UTR | AA | 204 | 13.1 (8.6; 17.3) | 0.0003 |

| AG | 271 | 14.2 (9.7; 18.9) | ||||

| GG | 112 | 15.3 (10.8; 20.7) | ||||

| CD46 | rs2796268 | flanking 5′ UTR | AA | 196 | 12.9 (8.4; 17.4) | 0.0005 |

| AG | 269 | 14.2 (10.0; 18.8) | ||||

| GG | 117 | 15.3 (10.7; 20.4) | ||||

| CD46 | rs2724382 | intron | GG | 201 | 13.0 (8.5; 17.1) | 0.0013 |

| GC | 272 | 14.6 (10.0; 18.9) | ||||

| CC | 114 | 15.3 (10.7; 20.4) | ||||

| CD46 | rs2724385 | intron | TT | 145 | 15.0 (10.6; 20.9) | 0.0013 |

| TA | 283 | 14.7 (9.5; 18.8) | ||||

| AA | 158 | 12.9 (8.9; 16.5) | ||||

| CD46 | rs2796267 | flanking 5′ UTR | AA | 200 | 12.8 (8.9; 17.8) | 0.0135 |

| AG | 279 | 14.6 (10.2; 18.8) | ||||

| GG | 107 | 15.5 (9.8; 20.4) | ||||

| African-American subgroup (n = 89) | ||||||

| SLAM | rsl0489635 | intron | GG | 77 | 11.8 (7.7; 18.1) | 0.0115 |

| GA | 11 | 7.4 (1.5; 13.4) | ||||

| AA | 0 | – | ||||

| CD46 | rsllll8516 | intron | GG | 75 | 11.6 (6.4; 17.4) | 0.0135 |

| GA | 13 | 10.3 (8.0; 16.5) | ||||

| AA | 0 | – | ||||

| CD46 | rsl7006738 | intron | GG | 63 | 10.3 (5.7; 17.0) | 0.0215 |

| GA | 23 | 13.9 (8.7; 18.8) | ||||

| AA | 2 | 23.4 (10.1; 36.6) | ||||

| CD209 | rs2287886 | flanking 5′ UTR | GG | 41 | 12.3 (8.0; 17.4) | 0.0236 |

| GA | 40 | 11.7 (6.0; 17.9) | ||||

| AA | 7 | 9.1 (7.4; 13.4) | ||||

A = Adeninę; C = cytosine; G = guanine; T = thymine; IQR = interquartile range.

A total of 55 SNPs were examined; only those found to be statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05) were included in the table. SNP rs8112310 (p = 1.1972E−07) displayed violations of HWE.

Values are presented as homozygous major allele/heterozygous/homozygous minor allele.

Values are median levels (IQR) in pg/ml as measured by ELISA.

Test for trend p value from the analysis of covariance adjusting for age, gender, race and age of immunization. The p values are adjusted for age, gender, race (when necessary), age at the first and second MMR and cohort status (cohort 1 vs. cohort 2) using analysis of covariance methodology.

Previously reported SNP associated with measles antibodies [24],

For the inflammatory cytokine IL-6, we replicated associations for the promoter SNP (rs2796267) in the CD46 gene in the combined cohort of subjects (p = 0.0006) and in our Caucasian (p = 0.004) subgroup. Analysis in the African-American subgroup revealed one significant association between SNP (rs11118516, p = 0.001) belonging to the CD46 gene and measles-specific IL-6 secretion levels.

SNP associations with measles-specific IL-10 secretion levels were also examined. No significant associations with measles-specific IL-10 secretion were found with polymorphisms in the CD46, SLAM or CD209 genes in either the combined cohort or in the cohort of Caucasian subgroup subjects. However, in African-Americans intronic SNP (rs11265452, p = 0.0008) in the SLAM gene was associated with measles-specific IL-10 secretion levels. Pair-wise LD analysis found rs11265452 to be linked to rs2089088 (D′ = 0.91) that was associated (p = 0.023) with variations in IL-10 secretion. This intronic SNP (rs11265452) in the SLAM gene was previously suggested as being associated with measles vaccine-induced antibody levels [24].

Further, we examined SNP associations with measles-specific IFN-α secretion levels (table 5). Increased representation of minor allele A for an intronic SNP rs2724384 of the CD46 gene was associated (already identified in our previous measles vaccine study) [24] with an allele dose-related increase (p = 0.007) in IFN-α levels in the combined cohort of study subjects. Similarly, increased representation of minor allele A for an intronic SNP of the CD46 gene (rs11118516) was marginally associated with an allele dose-related decrease in IFN-α levels (p = 0.040). As expected, in our Caucasian subgroup we observed reproduced associations for intronic SNPs in the CD46 gene (rs2724384, p = 0.002; rs2724382, p = 0.008, D′ = 0.99, and rs11118516, p = 0.007). The minor alleles of two additional CD46 promoter SNPs (rs2796268 and rs2796267, D′ = 0.77) were associated with an increase in MV-specific IFN-α secretion (p < 0.015). None of these SNPs replicated their associations with IFN-α response in African-American subjects, while SLAM promoter SNPs (rs17385878, p = 0.016, and rs2295614, p = 0.025, D′ = 0.19) were marginally associated with an increase (two-fold and four-fold for rs17385878 and rs2295614, respectively) in IFN-α levels in an allele dose-dependent manner.

For IFN-γ we found two SNP associations with variations in MV-specific secretion in promoter SNPs belonging to the SLAM (rs2295614, p = 0.013) and CD46 (rs2796267, p = 0.017) genes in the combined cohort of subjects. None of these SNPs and their associations with IFN-γ response could be replicated in a race-specific analysis of Caucasian subjects; however, these two SNPs replicated their associations with IFN-γ response in an allele dose-dependent manner in the African-American subgroup (SLAM rs2295614, p = 0.016, and CD46 rs2796267, p = 0.020). In addition, the minor allele for rs4804806 positioned in the promoter region of the CD209 gene was associated (p = 0.0007) with an allele dose-related decrease in IFN-γ secretion levels, a significant mediator of immune (and inflammatory) responses. Two CD46 SNPs (rs2796268, p = 0.001, and rs2724382, p = 0.007, D′ = 0.97) were significantly associated with variations in measles-specific IFN-γ secretion.

SNP associations with MV-specific INFλ-1 secretion were also examined (table 5). Cytokine INFλ-1, also known as IL-29, is a recently described cytokine that is linked to both the type I IFNs and IL-10 and displays strong anti-viral activity [39]. Specifically, increased carriage of major allele T for rs2295614 (p = 0.003) located in the 5′ UTR region of the SLAM gene was associated with a dose-related increase (1.5-fold) in INFλ-1 levels in the combined cohort. Of note, in the combined sample we reproduced the association of an intronic SNP rs2724382 (p = 0.04) in the CD46 gene (already identified in the African-American subjects with an increased IFN-γ secretion), and this minor allele was associated with an allele dose-related increase in INFλ-1 secretion. Promoter SNP rs2295614 in the SLAM gene was also associated with INFλ-1 response (4.8-fold increase, p = 0.008) in an allele dose-dependent manner in our Caucasian subgroup. Furthermore, increased carriage of the minor allele of the promoter SNP (rs12611071, p = 0.003) in the CD209 (DC-SIGN) gene was also associated with an allele dose-related increase (1.9-fold) in INFλ-1 secretion in our Caucasians. The African-American subgroup demonstrated an association with the promoter SNP rs17385878 (p = 0.020) of the SLAM gene (already identified in the African-American subjects with increased IFN-α secretion in an allele dose-dependent manner), and this minor allele A was associated with an allele dose-related increase in INFλ-1 secretion.

Finally, for TNF-α, another proinflammatory cytokine, we found nine potential (p ≤ 0.01) SNP associations with variations in measles-specific production and three of them were in promoter SNPs, belonging to the CD46 gene (table 5). The combined cohort demonstrated associations (range of p values: 0.0007–0.0048) between minor alleles of four SNPs (rs2724384, rs7144, rs2724385, and rs2796268) located in the CD46 gene and variations in TNF-α secretion, while these are not independent associations since these SNPs are in LD with each other (D′: 0.97–0.99). Further, pair-wise LD analysis found rs2796268 to be linked to rs2724382 (D′ = 0.99) and was associated (p = 0.014) with variations in TNF-α secretion levels. The Caucasian subgroup demonstrated significant associations for these SNPs (rs2724384, p < 0.0001; rs7144, p = 0.0003; rs2796268, p = 0.0005; rs2724382, p = 0.001, and rs2724385, p = 0.001) of the CD46 gene (already identified in the combined cohort) with measles-specific TNF-α secretion. None of these SNP associations were found in the African-American subjects. Race-specific analyses in the African-American subgroup revealed four potential associations (range of p values: 0.012–0.024) in intronic or UTR SNPs belonging to the SLAM gene (rs10489635), two SNPs (rs11118516 and rs17006738, D′ = 0.66) belonging to the CD46 gene, and one additional SNP (rs2287886) belonging to the CD209 gene and MV-specific TNF-α secretion levels.

Associations between CD46 Haplotypes and Measles-Specific TNF-α Secretion

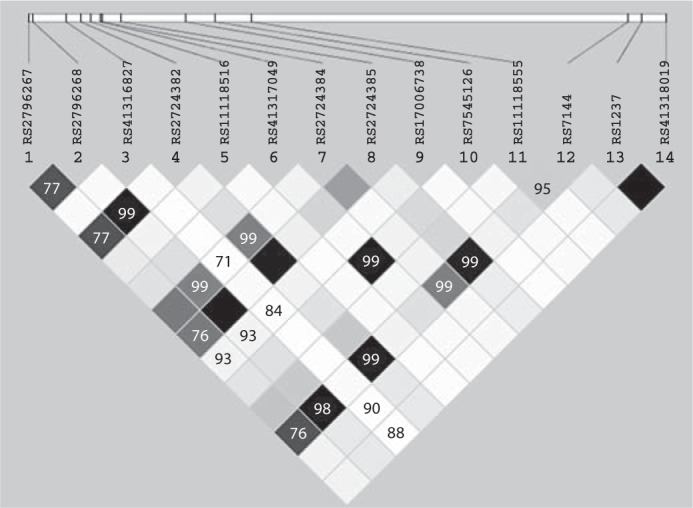

We also identified seven CD46 haplotypes with frequencies ≥1% in the Caucasian subgroup (table 6). A haplotype analysis revealed significant associations between TNF-α secretion and the CD46 haplotypes (global p value = 0.007). The CD46 haplotype AACGGAATGGAAAG was significantly associated (p = 0.009) with lower (t-statistic: −2.61) measles-specific TNF-α secretion, while the GGCCGAGAGGAGAG haplotype was significantly associated (p < 0.001) with elevated (t-statistic: 4.81) TNF-α secretion. The Haploview output of variants genotyped within the CD46 gene and their ordinary haplotypes associated with measles-specific TNF-α secretion are shown in figure 1.

Table 6.

CD46 haplotype associations with measles-specific TNF-a cytokine secretion in the Caucasian study subjects

| CD46 haplotypea | Frequency | Test statistic (haplotype t statistic) | p valueb |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| allele | global | |||

| AACGGAAAAGAAAG | 0.056 | −0.69 | 0.493 | 0.007 |

| AACGGAATGGAAAG | 0.294 | −2.61 | 0.009 | |

| AACGGCATGAAAAG | 0.123 | −0.21 | 0.835 | |

| AGCCGAAAGGAGCC | 0.059 | 1.16 | 0.248 | |

| GACGAAATGGAAAG | 0.051 | −1.21 | 0.225 | |

| GGCCGAAAGGTGAG | 0.123 | −0.81 | 0.418 | |

| GGCCGAGAGGAGAG | 0.227 | 4.81 | <0.001 | |

CD46 genetic variants fromleft to right: rs2796267, rs2796268, rs41316827, rs2724382, rsllll8516, rs41317049, rs2724384, rs2724385, rsl7006738, rs7545126, rsllll8555, rs7144, rsl237, rs41318019. Haplotype effects are estimated using the haplotype t-statistic, which reflects the direction and relative magnitude of the estimated haplotypic effect on the cytokine measure. Allele p values compare individual haplotypes to all other haplotypes combined.

One degree-of-freedom ordinal p value from the repeated measures regression analysis adjusting for age, gender, race, age at the first and second MMR vaccine and cohort status (cohort 1 vs. cohort 2).

Fig. 1.

Haplotype block structure of the CD46 gene region in the Caucasian subgroup subjects. Three intronic (rs2724384, rs2724382 and rs2724385, D′ ≥ 0.99) and three 3′ UTR/5′ UTR (rs7144, rs2796268 and rs2796267, D′ ≥ 0.76) SNPs from the CD46 gene were associated with TNF-α secretion. The LD block structure was analyzed using Haploview software, version 3.32. The r2 color scheme is: white (r2 = 0), shades of grey (0 < r2 < 1), black (r2 = 1).

Discussion

An earlier study performed with twins demonstrated that antibody response to measles vaccine has a very high heritability of 89% [40]. Previous studies have demonstrated that polymorphisms at the HLA, cytokine/cytokine receptor, measles CD46 and SLAM receptor, TLR and intracellular signaling genes and other candidate immune response genes are associated with significant variations in both humoral and CMI responses to measles vaccine [24,31,41,42,43,44]. Genetic variations that influence immune responses to measles vaccine may also differ across racial groups. In this regard, replication studies in diverse populations are critical for better understanding the significance of reported associations, and for identification of causative genetic variants and functionally relevant SNP alleles.

The protective pathway by which humoral and CMI responses develop to live MV is a multi-step procedure: MV must first interact with its cellular receptors (CD46 and SLAM) and also trigger TLRs or viral sensors like the cytoplasmic RIG-1-like helicases generating innate immune responses. Following antigen processing and presentation by class I and class II HLA molecules, cytokine/cytokine receptor gene activation takes place, with production of cytokines to stimulate Th1, Th2 and Th17 immune responses [45,46,47,48]. MV also targets CD209 (DC-SIGN) to augment DCs infection and also uses CD209 for viral transmission and immune suppression [11]. Understanding the genetic and molecular mechanisms influencing immune responses to measles vaccine cannot be obtained without a clear understanding of the contribution of genetic variants of CD46, SLAM and CD209 receptor genes at the beginning of the pathway leading to immunity. To date, however, such data are incomplete.

An earlier study of 346 Caucasian subjects demonstrated that the presence of specific SNPs in the MV receptor binding region of the SLAM gene was associated with measles-specific antibodies [24]. In particular, a non-synonymous SNP in exon 7 (rs3976504, in LD with rs164288) of the SLAM gene was associated with lower antibody levels following measles vaccine (p = 0.01) [24]. In addition, we reported that the presence of homozygous genotype for SNP (rs12076998) positioned 33 base pairs upstream of the MV-binding domain (exon 1) of the SLAM gene was associated with lower antibody levels [24]. We also reported associations between three intronic SNPs in the CD46 gene and measles antibody levels (p ≤ 0.01) [24]. Notably, an allele dose-related decrease (40%) in MV antibody response was observed with increased representation of minor allele C for an intronic SNP (rs11118580) of the CD46 gene. While the precise mechanism is still unclear, this SNP (rs11118580) may play an important function in the CD46 gene regulation [47,48].

This replication study validates the strongest associations between SNPs and measles-induced humoral (neutralizing antibodies) immunity discovered in our previous work with a new cohort of subjects. This is the first study to investigate associations between genetic polymorphisms in the two cellular receptors for MV (CD46 and SLAM) and a pathogen recognition receptor CD209, and variations in cellular (IFN-γ Elispot and secreted cytokines) immunity induced after measles vaccination.

Specifically, our results demonstrate that the association of the CD46 intronic SNP rs2724384 with measles-specific antibodies was replicated. Importantly, SNP rs2724384 in the CD46 gene appears to be an important SNP significantly associated (p = 0.0007) with lower MV-specific neutralizing antibody levels in an allele dose-related manner. This result is consistent with the data obtained in our previous measles vaccine humoral immunity study, where the levels of MV-specific IgG titer in serum were examined by using an enzyme immunoassay (Enzygnost, Dade Behring, Marburg, Germany) [24]. The previous finding of an association between this intronic SNP (rs2724384) in the CD46 gene and measles antibodies in a cohort of Caucasian subjects strengthens our confidence that the reported association is not a false positive due to chance alone [24]. Also, an allele dose-related decrease in MV-induced IFN-α responses was observed with increased carriage of the minor allele for this SNP rs2724384 in the CD46 gene in both our combined cohort (p = 0.006) and in the Caucasian subgroup (p = 0.001). The same intronic CD46 SNP, rs2724384, was observed to be associated with TNF-α (p = 0.0006) and IL-6 (p = 0.027) secretion in the combined cohort of subjects. This suggests that rs2724384 in the CD46 gene may also play a role in measles vaccine-induced immune responses and may have functional consequences regarding measles viral immunity.

A coding polymorphism (rs164288, Thr→Thr at amino acid 210 in the Ig-like C2-type extracellular domain of the molecule) in the SLAM gene was associated with measles-specific IFN-γ Elispot responses in African-American subjects. The prior discovery of an allele dose-response relationship with measles antibodies for this coding SNP rs164288 in the SLAM gene suggests a role for this polymorphism in controlling cross-regulation of vaccine-specific humoral and CMI responses [24]. Besides acting as a MV receptor, SLAM is involved in lymphocyte activation, cell proliferation, antigen binding, and trans-membrane receptor activity [7,8,9]. Recent studies have demonstrated that engagement of the SLAM receptor augments antigen-specific lymphocyte proliferation and Th0/Th1 cytokine secretion profile (specifically, strong upregulation of IFN-γ), in a CD28-independent manner [49]. Another polymorphism (rs11265452) was also found in the SLAM gene associated with measles-specific IL-10 production in the African-American subgroup. An earlier finding of an association between this intronic SNP (rs11265452) in the SLAM gene and variations in measles antibodies provides evidence for a potential involvement of this specific SNP in cross-regulation of antibody and cytokine secretion patterns [24]. In this regard, human IL-10 is known to suppress cytokine secretion of Th1 cells and the activity of macrophages; however, IL-10 is also known to stimulate plasma cells, increasing antibody secretion [50]. These and additional cross-regulation cytokine secretion patterns found in our study cohorts offer further evidence that these genetic determinants are implicated in the mechanisms underlying inter-individual differences in measles vaccine-induced immune responses.

In the current study, several SNPs were found in the MV binding domain of the CD46, SLAM and cellular pathogen recognition receptor CD209 genes (and some of these SNPs were associated in an allele dose-related manner). Our data show associations between promoter (rs11881682) and intronic (rs8105572 and rs7252229) SNPs in the CD209 gene and measles-specific IFN-γ Elispot responses in Caucasian subjects. De Witte et al. [11] demonstrated that CD209 (DC-SIGN), as an attachment receptor, augments CD46/SLAM (CDw150)-mediated MV infection of DCs, whereas only DC-SIGN, but not SLAM receptor, is involved in the MV infection of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [16]. These observations indicate that CMI responses to MV infection (or live MV immunization) may also be influenced by genetic polymorphisms in the CD209. Although these SNPs in the CD46, SLAM and CD209 genes are not associated or are not in LD with recognized polymorphisms in the coding or promoter sequences of respective genes, associations can potentially be mediated through noncoding polymorphisms that have an effect on gene expression [51].

Our results offer evidence for associations of variants in promoter and intronic regions of CD46, SLAM and CD209 genes with MV-specific secreted cytokine responses, such as IFN-γ Elispot, IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, IFN-α, IFN-γ, IFNλ-1, and TNF-α. The most significant associations were observed with the CD46 gene (range of p values: 0.00002–0.001). We identified a polymorphism in the CD46 intronic region (rs2724382 that is in LD with rs2724384, D′ = 0.99) that was associated with secretion of several cytokines, such as IL-2, IFN-α, IFN-γ, IFNλ-1, and TNF-α, suggesting that Th1/proinflammatory immune responses to MV may be influenced by polymorphisms in the CD46 gene. In addition to CD46 SNPs, our study identified genetic variants within the SLAM gene. In our study, rs2753260 that is in LD with rs11265452 (D′ = 0.80), rs11265452, and rs2089088, all of which are in pair-wise LD in the SLAM gene, emerge as significantly associated with variations in measles-induced IL-6 and IL-10 secretion, respectively, in African-Americans. In addition, we identified an individual promoter SNP (rs4804806) in the CD209 gene that appears to influence measles-induced IFN-γ and IL-2 secretion levels in African-American subjects. Additional studies are required to validate these genetic associations and exclude the likelihood of false-positive associations. Understanding the functional and mechanistic consequences of these genetic variations on immune response variations could assist in directing new vaccine design and generate new hypotheses applicable to developing new measles vaccine candidates (i.e. ‘vaccinomics – the application of immunogenomics and immunogenetics to understanding the biologic basis of vaccine response’ [47,48]).

The strengths of our study include a large sample size (764 subjects) with documented measles vaccine coverage, a population-based study approach, and a comprehensive analysis of measles vaccine virus-specific genotype-phenotype associations. Humoral and CMI laboratory measurements reflected measles vaccination and not disease, since our study subjects were residents of Rochester, Minn., USA, a community where no case of wild-type MV infection had been registered during their lifetimes. We observed statistically significant higher antibody levels (p = 0.02), higher IFN-γ Elispot responses (p < 0.001), higher IL-6 secretion (p = 0.02), and lower IL-2 secretion (p < 0.001) in cohort 1 subjects compared to cohort 2 subjects. We accounted for the possible confounding effects of cohort status by including it as an adjustment term in all association models. We also accounted for waning immunity phenomenon in our statistical association models and, thus, we do not expect variation in the timing of the evaluation to bias any of our association results. Our analysis was performed on cohorts of Caucasian and African-American subjects and a combined cohort of Caucasian, African-American and other subjects, allowing for validation of suggested associations in a race-specific manner. The study was carried out within the guidelines of the NCI-NHGRI (National Human Genome Research Institute) Working Group on Replication in Association Studies and other expert reviews [52]. A clear message from these reviews is to perform replication studies in a population as closely matched to the discovery cohort as possible [53,54,55].

Limitations of our study include a relative under-representation of African-American subjects (n = 89). Our results can not be applied to Hispanic or other ethnic groups that we did not study. It is possible that critical associations may have been missed because of the limits in power resulting from a small African-American subgroup of study subjects. Thus, we reported all tests that reached the 0.05 level of significance. This led to another limitation. We examined a total of 55 SNPs, each on a set of 9 immune response outcomes and across 3 racial groups, for a total of 1,485 statistical tests. Assuming independent tests for association, one would expect 74 associations to be statistically significant based just on chance alone (at p = 0.05). We found 82 such associations across the measures of MV-induced immunity. Further, many of these associations were replicated across two separate cohorts – increasing confidence in our findings. In addition, our subjects were studied several years after their second dose of MMR. This is appropriate as our studies are clinically focused and center on understanding genetic associations with long-term immunity – the ‘type’ of immunity that does or does not protect against disease when exposed later in life.

In conclusion, we have shown a strong relationship including validation between polymorphisms in the CD46, SLAM and CD209 genes influencing humoral and CMI responses after two doses of measles vaccine. Our previously detected association of the CD46 SNP rs2724384 with measles-specific antibodies was successfully replicated in this study. Furthermore, this polymorphism (rs2724384) demonstrated associations with measles-specific IL-6, IFN-α and TNF-α responses. Five SNPs, not previously reported, were identified in the CD209 gene and were significantly associated with measles-specific antibodies. We also found a coding polymorphism (rs164288) in the SLAM gene demonstrating associations with measles-specific antibody and IFN-γ Elispot responses in two separate studies. A polymorphism (rs11265452) in the SLAM gene previously associated with measles antibody levels demonstrated an association with measles-specific IL-10 secretion in this study. We identified associations between haplotypes in the CD46 gene and measles-specific TNF-α secretion. Causal functional genetic variations responsible for these replicated associations need to be identified in future studies. Future studies should also examine the possibility that multigenic SNP interactions across the CD46, SLAM and CD209 and additional genes may be involved in the genetics of measles vaccine immune response. These data will improve our understanding of the genetic determinants of measles vaccine immunity and may lead to novel vaccination strategies as well as possible new adjuvants and vaccines.

Disclosures

Dr. Poland is the chair of a safety evaluation committee for novel non-measles vaccines undergoing clinical studies by Merck Research Laboratories. Dr. Jacobson serves on a Safety Review Committee for a post-licensure study of Gardasil for Kaiser-Permanente.

Acknowledgements

We thank the parents and children who participated in this measles vaccine study. We acknowledge the efforts of the research fellows and nurses from the Mayo Vaccine Research Group. We thank V. Shane Pankratz, PhD, and Matthew J. Phan, BS, for their assistance with the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grants AI 33144 (to G.A.P.), AI 48793 (to G.A.P.), and 5UL1RR024150-03 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health, and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

References

- 1.Bouche FB, Ertl OT, Muller CP. Neutralizing B cell response in measles. Viral Immunol. 2002;15:451–471. doi: 10.1089/088282402760312331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moss WJ, Griffin DE. Global measles elimination. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:900–908. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Permar SR, Klumpp SA, Mansfield KG, Kim WK, Gorgone DA, Lifton MA, Williams KC, Schmitz JE, Reimann KA, Axthelm MK, Polack FP, Griffin DE, Letvin NL. Role of CD8(+) lymphocytes in control and clearance of measles virus infection of rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 2003;77:4396–4400. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.7.4396-4400.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andres O, Obojes K, Kim KS, ter Muelen V, Schneider-Schaulies J. CD46- and CD150-independent endothelial cell infection with wild-type measles viruses. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:1189–1197. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18877-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu EC, Lorio C, Sarangi F, Khine AA, Richardson CD. CDw150(SLAM) is a receptor for a lymphotropic strain of measles virus and may account for the immunosuppressive properties of this virus. Virology. 2001;279:9–21. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manchester M, Naniche D, Stehlet T. CD46 as a measles receptor: form follows function. Virology. 2000;274:5–10. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorig RE, Marcil A, Chopra A, Richardson CD. The human CD46 molecule is a receptor for measles virus (Edmonston strain) Cell. 1993;75:295–305. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80071-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naniche D, Varior-Krishnan G, Cervoni F, Wild TF, Rossi B, Rabourdin-Combe C, Gerlier D. Human membrane cofactor protein (CD46) acts as a cellular receptor for measles virus. J Virol. 1993;67:6025–6032. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6025-6032.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yanagi Y, Ono N, Tatsuo H, Hashimoto K, Minagawa H. Measles virus receptor SLAM (CD150) Virology. 2002;299:155–161. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider U, von Messling V, Devaux P, Cattaneo R. Efficiency of measles virus entry and dissemination through different receptors. J Virol. 2002;76:7460–7467. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.15.7460-7467.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Witte L, Abt M, Schneider-Schaulies S, van Kooyk Y, Geijtenbeek TB. Measles virus targets DC-SIGN to enhance dendritic cell infection. J Virol. 2006;80:3477–3486. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.7.3477-3486.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castro AG, Hauser TM, Cocks BG, Abrams J, Zurawski S, Churakova T, Zonin F, Robinson D, Tangye SG, Aversa G, Nichols KE, De Vries JE, Lanier LL, O'Garra A. Molecular and functional characterization of mouse signaling lymphocytic activation molecule (SLAM): differential expression and responsiveness in Th1 and Th2 cells. J Immunol. 1999;163:5860–5870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Punnonen J, Cocks BG, Carballido JM, Bennett B, Peterson D, Aversa G, De Vries JE. Soluble and membrane-bound forms of signaling lymphocytic activation molecule (SLAM) induce proliferation and Ig synthesis by activated human B lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1997;185:993–1004. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.6.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aversa G, Carballido J, Punnonen J, Chang CC, Hauser T, Cocks BG, De Vries JE. SLAM and its role in T cell activation and Th cell responses. Immunol Cell Biol. 1997;75:202–205. doi: 10.1038/icb.1997.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henning G, Kraft MS, Derfuss T, Pirzer R, Saint-Basile G, Aversa G, Fleckenstein B, Meinl E. Signaling lymphocytic activation molecule (SLAM) regulates T cellular cytotoxicity. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:2741–2750. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200109)31:9<2741::aid-immu2741>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Witte L, de Vries RD, van der Vlist M, Yuksel S, Litjens M, de Swart RL, Geijtenbeek TB. DC-SIGN and CD150 have distinct roles in transmission of measles virus from dendritic cells to T-lymphocytes. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000049. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ono N, Tatsuo H, Tanaka K, Minagawa H, Yanagi Y. V domain of human SLAM (CDw150) is essential for its function as a measles virus receptor. J Virol. 2001;75:1594–1600S. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.4.1594-1600.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tatsuo H, Ono N, Tanaka K, Yanagi Y. SLAM (CDw150) is a cellular receptor for measles virus. Nature. 2000;406:893–897. doi: 10.1038/35022579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrand V, Li C, Romeo G, Yin L. Absence of SLAM mutations in EBV-associated lymphoproliferative disease patients. J Med Virol. 2003;70:131–136. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casasnovas JM, Larvie M, Stehle T. Crystal structure of two CD46 domains reveals an extended measles virus-binding surface. EMBO J. 1999;18:2911–2922. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.11.2911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manchester M, Eto DS, Valsamakis A, Liton PB, Fernandez-Munoz R, Rota PA, Bellini WJ, Forthal DN, Oldstone MB. Clinical isolates of measles virus use CD46 as a cellular receptor. J Virol. 2000;74:3967–3974. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.3967-3974.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerlier D, Trescol-Bi'mont MC, Varior-Krishnan G, Naniche D, Fugier-Vivier I, Rabourdin-Combe C. Efficient major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted presentation of measles virus relies on hemagglutinin-mediated targeting to its cellular receptor human CD46 expressed by murine B cells. J Exp Med. 1994;179:353–358. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erlenhofer C, Duprex WP, Rima BK, ter Meulen V, Schneider-Schaulies J. Analysis of receptor (CD46, CD150) usage by measles virus. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:1431–1436. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-6-1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhiman N, Poland GA, Cunningham JM, Jacobson RM, Ovsyannikova IG, Vierkant RA, Wu Y, Pankratz VS. Variations in measles vaccine-specific humoral immunity by polymorphisms in SLAM and CD46 measles virus receptors. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:666–672. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ovsyannikova IG, Dhiman N, Haralambieva IH, Vierkant RA, O'Byrne MM, Jacobson RM, Poland GA. Rubella vaccine-induced cellular immunity: evidence of associations with polymorphisms in the Toll-like, vitamin A and D receptors, and innate immune response genes. Hum Genet. 2010;127:207–221. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0763-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ovsyannikova IG, Haralambieva IH, Dhiman N, O'Byrne MM, Pankratz VS, Jacobson RM, Poland GA. Polymorphisms in the vitamin A receptor and innate immunity genes influence the antibody response to rubella vaccination. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:207–213. doi: 10.1086/649588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haralambieva IH, Dhiman N, Ovsyannikova IG, Vierkant RA, Pankratz VS, Jacobson RM, Poland GA. 2′-5′-Oligoadenylate synthetase single-nucleotide polymorphisms and haplotypes are associated with variations in immune responses to rubella vaccine. Hum Immunol. 2010;71:383–391. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dhiman N, Haralambieva IH, Kennedy RB, Vierkant RA, O'Byrne MM, Ovsyannikova IG, Jacobson RM, Poland GA. SNP/haplotype associations in cytokine and cytokine receptor genes and immunity to rubella vaccine. Immunogenetics. 2010;62:197–210. doi: 10.1007/s00251-010-0423-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pankratz VS, Vierkant RA, O'Byrne MM, Ovsyannikova IG, Poland GA. Associations between SNPs in candidate immune-relevant genes and rubella antibody levels: a multigenic assessment. BMC Immunol. 2010;11:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-11-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haralambieva IH, Ovsyannikova IG, Vierkant RA, Poland GA. Development of a novel efficient fluorescence-based plaque reduction microneutralization assay for measles immunity. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:1054–1059. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00008-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ovsyannikova IG, Haralambieva IH, Vierkant RA, Pankratz VS, Jacobson RM, Poland GA. The role of polymorphisms in Toll-like receptors and their associated intracellular signaling genes in measles vaccine immunity. Hum Genet. 2011;130:547–561. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-0977-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ryan JE, Ovsyannikova IG, Poland GA. Detection of measles virus-specific IFN-gamma-secreting T-cells by ELISPOT. In: Kalyuzhyny AE, editor. Handbook of ELISPOT: Methods and Protocols. Totowa: Humana Press Inc; 2005. pp. 207–217. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carlson CS, Eberle MA, Rieder MJ, Yi Q, Kruglyak L, Nickerson DA. Selecting a maximally informative set of single-nucleotide polymorphisms for association analyses using linkage disequilibrium. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:106–120. doi: 10.1086/381000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.den Dunnen JT, Antonarakis SE. Nomenclature for the description of human sequence variations. Hum Genet. 2001;109:121–124. doi: 10.1007/s004390100505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haralambieva IH, Dhiman N, Ovsyannikova IG, Vierkant RA, Pankratz VS, Jacobson RM, Poland GA. Oligoadenylate synthetase single-nucleotide polymorphisms and haplotypes are associated with variations in immune responses to rubella vaccine. Hum Immunol. 2010;71:383–391. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weir BS: Genetic Data Analysis II: Methods for Discrete Population Genetic Data, ed 2. Sinauer Associates, Inc. 1996, pp 98–99.

- 37.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schaid DJ, Rowland CM, Tines DE, Jacobson RM, Poland GA. Score tests for association between traits and haplotypes when linkage phase is ambiguous. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:425–434. doi: 10.1086/338688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jordan WJ, Eskdale J, Boniotto M, Rodia M, Kellner D, Gallagher G. Modulation of the human cytokine response by interferon lambda-1 (IFN-lambda1/IL-29) Genes Immun. 2007;8:13–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tan PL, Jacobson RM, Poland GA, Jacobsen SJ, Pankratz SV. Twin studies of immunogenicity – determining the genetic contribution to vaccine failure. Vaccine. 2001;19:2434–2439. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00468-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Poland GA, Ovsyannikova IG, Jacobson RM, Vierkant RA, Jacobsen SJ, Pankratz VS, Schaid DJ. Identification of an association between HLA class II alleles and low antibody levels after measles immunization. Vaccine. 2001;20:430–438. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00346-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ovsyannikova IG, Pankratz VS, Vierkant RA, Jacobson RM, Poland GA. Human leukocyte antigen haplotypes in the genetic control of immune response to measles-mumps-rubella vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:655–663. doi: 10.1086/500144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]