Abstract

The members of the Snail superfamily of zinc-finger transcription factors, including Snai1 and Snai2, are involved in essential biological processes, such as epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). While Snai1 has been investigated in a number of cancers, our knowledge on Snai2 and its role(s) in squamous cell carcinoma of oral tongue (SCCOT) is limited. In this study, we confirmed the previous observation that over-expression of Snai2 is a frequent event in SCCOT. We further demonstrated that Snai2 over-expression is associated with lymph node metastasis in two independent SCCOT patient cohorts (total n = 129). Statistical analysis revealed that Snai2 over-expression was correlated with reduced overall survival. Furthermore, over-expression of Snai2 was correlated with reduced E-cadherin expression and enhanced Vimentin expression, suggesting a functional role of Snai2 in EMT. These observations were confirmed in vitro, in which knockdown of Snai2 induced a switch from a mesenchymal-like morphology to an epithelial-like morphology in SCCOT cell lines, and suppressed the cell invasion and migration. In contrast, ectopic transfection of Snai2 led to enhanced cell invasion and migration. Furthermore, Snai2 knockdown attenuated TGFβ1-induced EMT in SCCOT cell lines. Taken together, these data suggest that Snai2 plays major roles in EMT and the progression of SCCOT, and may serve as a therapeutic target for patients at risk of metastasis.

Keywords: epithelial menschymal transition, E-cadherin, Snai2, squmous cell carcinoma

Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is a complex disease that arises at various sites. Tumors from these different sites have distinct clinical presentations and outcomes, and are associated with different genetic characteristics 1. In this study, we focused on squamous cell carcinoma of oral tongue (SCCOT), one of the most common sites for OSCCs. SCCOT is significantly more aggressive than other forms of OSCCs, with a propensity for rapid local invasion and spread 2. Despite continuous advancements in therapeutic strategies, the mortality rate of SCCOT patients has not changed significantly over the past 30 years, and patients continue to die from metastasis diseases 3–7. Recent studies have demonstrated that epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) plays a major role in cancer cell invasion and the metastasis cascade 8, 9. EMT is characterized by a spectrum of cellular and morphological changes that include loss of polarity and cell-cell adhesion, increased motility, and acquisition of the mesenchymal phenotype 10, 11. These phenotypic changes are accompanied by alterations at the molecular level including the repression of E-cadherin gene expression (one of the hallmarks of EMT). E-cadherin is a major cell-to-cell adhesion molecule and plays a crucial role in the development and maintenance of epithelial cell polarity and tissue architecture 12. The loss of E-cadherin expression has been linked to enhanced SCCOT invasiveness, metastasis, and poor prognosis 13, 14.

The members of the Snail superfamily of zinc-finger transcription factors, including Snai1 and Snai2 (human homologs of Drosophila snail and slug genes), are transcriptional repressors that have been implicated in EMT during embryonic development and tumor progression 15, 16. While a number of studies have demonstrated the roles of Snai1 in the repression of E-cadherin expression and the induction of EMT in OSCC 17–19, only a few preliminary studies have reported on Snai220. The effect of Snai2 on SCCOT progression has not been defined. The aims of this study are to examine deregulation of Snai2 in SCCOT and to investigate its roles in EMT and SCCOT progression.

Materials and Methods

Patient

Two SCCOT patient cohorts were utilized in this study. The clinical characterization of the patients is summarized in Supplementary Table 1. The cohort #1 was used for evaluating the expression of Snail family members at the mRNA level. This group consists of 53 SCCOT cases and 22 matching adjacent non-cancerous samples with microarray data generated either from our previous study 21 or downloaded from the GEO database 22–24. The cohort #2 was used for assessing gene expression at the protein level using immunohistochemical assay. This group includes 76 SCCOT patients who were diagnosed and underwent radical surgeries between 1996 and 2005 at the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Hospital of Stomatology, Sun Yat-sen University. None of the patients received any form of adjuvant therapy prior to surgery. The tumor extent was classified according to the TNM system by UICC, and the tumor grade was classified according to the WHO classification of histological differentiation. Survival was calculated based on the date of surgery and the date of the last follow-up (or death). Median duration of follow-up was 65 months (range 3–120 months). This study was approved by the ethical committee of Sun Yat-Sen University.

Pooled-analysis to extract gene expression values from existing microarray dataset

The pooled-analysis was performed as described previously. In brief, the CEL files from all datasets (53 SCCOTs and 22 normal tongue samples) were imported into the statistical software R 2.4.125 using Bioconductor 26. The pooled-analysis was performed as described 27, and the genome-wide expression pattern is presented in our previous study 21. The Robust Multi-Array Average (RMA) expression measures 28 for each microarray dataset were computed after background correction and quantile normalization. Then, expression values of the overlapping probesets between U133A and U133 Plus 2.0 arrays were extracted. Probeset-level quantile normalization was performed across all samples to make the effect sizes similar among the four datasets 27. The expression values for probesets corresponding to Snai1 gene (219408_at) and for Snai2 gene (213139_at), Snai3 (1560228_at), E-cadherin (201130_s_at and 201131_s_at), and Vimentin (201420_s_at and 1555938_x_at) were then extracted from each dataset. Relative expression level for Snai1, Snai2, Snai3, E-cadherin, and Vimentin genes for each SCCOT samples were computed as previously described 29.

Immunohistochemical analysis

Immunohistochemical staining was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embodied tissue sections. Representative sections were first stained with H&E and histologically evaluated by a pathologist. The selected sections were deparaffinized, quenched for endogenous peroxidase activity, and rehydrated as described previously 30. Sections were then blocked with 10% normal serum for 15 min at 37 °C followed by incubation with rabbit anti-Snai2 (Cell signaling, USA), mouse anti-E-cadherin (BD Bioscience, USA), or mouse anti-Vimentin (Cell signaling, USA) at a dilution of 1:100 for 16 h at 4 °C. After washing thrice in PBS, the sections were incubated with secondary antibody conjugated to biotin for 10 min at room temperature. After additional washing in PBS, the sections were incubated with streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase enzyme for 10 min at room temperature. Following final washes in PBS, antigen-antibody complexes were detected by incubation with a horseradish peroxidase substrate solution containing 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride chromogen reagent, and counterstained with hematoxylin. Slides were rinsed in distilled water, cover-slipped using aqueous mounting medium, and allowed to dry at room temperature.

The relative intensities of the completed immunohistochemical reactions were evaluated using light microscopy by 3 independent trained observers who were unaware of the clinical data. All areas of tumor cells within each section were analyzed. The non-cancerous epithelium adjacent to the tumor cells were used as an internal control for the same cases. All tumor cells in ten random high power fields were counted. Immunoreactivity was semiquantitatively evaluated on the basis of staining intensity and distribution using the immunoreactive score, where Immunoreactive score = intensity score × proportion score. The intensity score was defined as 0: negative; 1: weak; 2: moderate; or 3: strong, and the proportion score was defined as 0: negative; 1: ≤ 10%; 2: 11–50% 3: 51–80% or 4: > 80% positive cells. The immunoreactive score ranged from 0 to 12. The immunoreactivity was divided into two groups on the basis of the immunoreactive score: low immunoreactivity was defined as a total score of 0–4, and high immunoreactivity was defined as a total score >4.

Cell Culture and the treatments of cell lines

The SCC9 cell line was acquired from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), and the UM1 cell line was a gift from Dr. David Wong at UCLA School of Dentistry. These SCCOT cell lines were maintained in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (GIBCO). For functional analysis, gene specific siRNA against Snai2 (On-TargetPlus SMARTpool, Dharmacon) or control siRNA was transfected into cells using DharmaFECT Transfection Reagent 1 as described previously 31, 32. The Snai2 expression vector (pCMV6-SNAI2, OriGene Technologies, Inc) or empty vector was transfected into cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). For the induction of EMT, cells were treated with 10ng/ml TGFβ1 as described previously 33, 34.

Fluorescent immunocytochemical analysis

Cells were fixed on the slides and permeabilized as previously described 35, and then blocked with 5% BSA for 30 minutes, followed by incubation with primary antibodies (E-cadherin, BD Bioscience, USA and Vimentin, Cell signaling, USA) at 4°C for 16 h. The slides were then washed with PBS and incubated with Rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody (for Vimentin) or FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (for E-cadherin) for 1 hour at 37°C. The slides were then washed with PBS and incubated with 5μg/ml DAPI for nuclear staining. The cells were visualized for immunofluorescence with a laser scanning Zeiss microscope system (Zeiss Axivert 400C, Germany).

Western blot analysis

Western blots were performed as described previously 32 using antibodies specific to Snai2 (Cell Signaling, USA), E-cadherin (BD Biosciences, USA), Vimentin (BD Biosciences, USA), beta-actin (Sigma, USA), and a Immu-StarHRP Substrate Kit (BIO-RAD, USA).

In vitro cell migration and invasion assay

The in vitro cell migration and invasion were measured using the BD BioCoat system (BD Biosciences, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, cells were seeded in the upper chambers, and culture medium with 10% FBS was added to the lower chambers. For invasion assay, transwell inserts coated with Matrigel were used. After 24 h incubation, cells that migrated to the reverse side of inserts were stained with Diff-Quik stain kit (Polyscience, USA) and quantified.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS, Chicago, IL), Version 17.0. Spearman Correlation Coefficient was used to assess correlations among the gene expression and clinical and histopathological parameters. One-way ANOVA was used to assess the association of Sani2 expression with pN. Kaplan-Meier plots were constructed to present survival outcomes. Cox regression was used for both univariate and multivariate analysis. For multivariate analysis, grade, tumor size, pathological T-stage (pT), pathological N-stage (pN), clinical stages and the expression of Snai2, E-cadherin and Vimentin were considered as co-variates. For all statistical analyses, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The expression of snail family members at mRNA level in SCCOT

Pooled-analysis was performed on previously existing microarray datasets to determine the expression of Snail family members at the mRNA level in SCCOT (n=53) and normal control samples (n=22). As illustrated in Supplementary Figure 1, Snai2 is significantly over-expressed in SCCOT as compared to normal tissue. A statistically significant increase in Snai2 expression was also observed in the primary tumor tissues with lymph node metastasis (pN+) when compared to those with negative status (pN−). However, no difference in Snai1 expression was observed between normal and tumor samples, and no statistically significant difference in Snai1 expression was observed between primary tumor tissues with (pN+) or without lymph node metastasis (pN−). The expression of Snai3 was not detected in these cases.

The Snai2 protein level in SCCOT

To confirm our observation and further elucidate the role of Snai2, the expression of the Snai2 gene was examined by immunohistochemistry (IHC) in an additional SCCOT patient cohort (n = 76) (Supplementary Table 1). As illustrated in Figure 1A, in normal epithelium, Snai2 was detectable only in basal layers. In cancer cells, predominant nuclei staining of Snai2 were observed. Semi-quantitative analysis revealed that Snai2 is significantly over-expressed in SCCOTs when compared to normal tissue (Supplementary Table 2). Among 76 cases of SCCOT samples that we examined, 48 cases (63.16%) exhibited low nuclear staining for Snai2 (Figure 1B) and 28 cases (36.84%) exhibited high staining for Snai2 (Figure 1C). Furthermore, a dramatically increased nuclear staining of Snai2 was observed at the invasive front (Figure 1D and Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 1. Immunohistochemistry analyses of Snai2, E-cadherin and Vimentin expression in SCCOT.<.

br>Immunohistopathological analyses were performed as described in Material and Methods to examine the Snai2, E-cadherin, and Vimentin expression respectively on A, E, and I: adjacent normal epithelium (n = 10); B, F, and J: well differentiated primary (n = 52); C, G, and K: moderate or poor differentiated SCCOT (n = 24), D, H, L: invasive fronts of SCCOT (n = 76). Representative images of x200 magnification were presented. Scale bar = 200 μm.

Since overexpression of Snai2 has been linked to the induction of EMT, the levels of E-cadherin and Vimentin in these cases were also examined by IHC. As shown in Figure 1E, strong staining of E-cadherin was detected at the cytoplasmic membrane and the intercellular borders in the normal epithelium. Among 76 cases of SCCOT that we examined, high E-cadherin expression was observed in 34 cases (44.74%) (Figure 1F), and reduced E-cadherin expression was found in 32 cases (55.26%) (Figure 1G). SCCOT cells located at the invasive front were found to have no detectible E-cadherin staining (Figure 1H). As shown in Figure 1I, Vimentin staining was detected in the cytoplasm of the connective tissue mesenchymal cells, but not in normal epithelia cells. Of the 76 SCCOT cases, 38 (50.00%) showed negative or low cytoplasmic staining of Vimentin (Figure 1J), and 38 (50.00%) exhibited high Vimentin staining. Increased cytoplasmic staining of Vimentin was observed in the majority of SCCOT cells located in the invasive front and the de-differentiated cancer cells (Figure 1K and 1L)

Correlation among Snai2 expression, EMT markers and clinicopathological features in SCCOT

Correlations were tested among gene expression (e.g., Snai2, E-cadherin and Vimentin), clinical and pathological features for both SCCOT patient cohorts (Table 1). For patient cohort #1 (n = 53), the Snai2 mRNA level was positively correlated with pN (P<0.05) and Vimentin expression (P<0.01). For patient group #2 (n = 76), the Snai2 protein level was correlated with tumor size (P<0.01), pT stage (P<0.05), pN (P<0.05) and clinical stage (P<0.05). The expression of Snai2 significantly correlated with reduced E-cadherin expression (P<0.001) and enhanced Vimentin expression (P<0.05). It is important to note that of the 2 patient groups examined (total n = 129), correlation was consistently observed between Snai2 expression and pN. The Snai2 expression is significantly up-regulated in SCCOT cases with lymph node metastasis (pN+) as compared to those with negative status (pN−) (Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 2).

Table 1.

Correlations among clinical and histopathological features of primary SCCOT#

| sex | age | tumor size | grade | pT | pN | C stage | E-cad | Vim | Snai2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient cohort #1 (n = 53) | ||||||||||

| sex | 0.06 | na | na | 0.08 | −0.24 | −0.08 | 0.23 | −0.17 | −0.23 | |

| age | na | na | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.17 | −0.09 | −0.05 | ||

| tumor size | na | na | na | na | na | na | na | |||

| grade | na | na | na | na | na | na | ||||

| pT | 0.05 | 0.59* | 0.03 | −0.55* | −0.71* | |||||

| pN | 0.50* | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.28* | ||||||

| C stage | 0.02 | −0.30 | −0.37* | |||||||

| E-cad | 0.02 | 0.06 | ||||||||

| Vim | 0.67* | |||||||||

| Snai2 | ||||||||||

| Patient cohort #2 (n = 76) | ||||||||||

| sex | −0.10 | 0.19 | −0.05 | 0.33* | 0.03 | 0.22 | 0.12 | −0.36* | −0.05 | |

| age | −0.09 | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.11 | −0.05 | −0.20 | ||

| tumor size | 0.03 | 0.71* | 0.09 | 0.44* | −0.13 | −0.06 | 0.28* | |||

| grade | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.10 | −0.26* | 0.23 | 0.18 | ||||

| pT | 0.28* | 0.65* | −0.15 | 0.06 | 0.31* | |||||

| pN | 0.77* | −0.39* | 0.21 | 0.23* | ||||||

| clinical stage | −0.26* | 0.11 | 0.25* | |||||||

| E-cad | −0.53* | −0.30* | ||||||||

| Vim | 0.27* | |||||||||

| Snai2 | ||||||||||

Spearman correlation coefficients were presented.

The expression levels of Snai2, E-cadherin and Vimentin for Patient cohort #1 were based on the relative mRNA level. The expression levels of Snai2, E-cadherin and Vimentin for Patient cohort #2 were generated from semi-quantitative immunohistochemical analysis.

pT: pathological T-stage; pN: pathological N-stage; C stage: clinical stage.

p < 0.05. The p values were computed using Fisher’s transformed z-score test.

na: data not available.

The prognostic value of Snai2 deregulation for SCCOT patients

As illustrated in Figure 2, a striking difference in prognosis was observed between the high Snai2 expression group (5-year survival rate < 50%) and the low Snai2 expression group (5-year survival rate > 70%). The differences in survival were also observed when patients were grouped based on the expression of E-cadherin or Vimentin (Supplementary Figure 3). As illustrated in Table 2, univariate analysis indicated that grade, tumor size, pathological T-stage, lymph node metastasis, clinical stage, Snai2, Viemntin and E-cadherin were all significant prognostic factors for patients with SCCOT. Multivariate analysis showed that E-cadherin, and to a lesser extent Vimentin, were independent prognostic factors for SCCOT patients (p = 0.01, and p = 0.062, respectively). However, Snai2 appears not to be an independent prognostic factor.

Figure 2. The effects of Snai2 on the prognosis SCCOT patients.

Kaplan-Meier plots of overall survival in patient groups defined by the expression levels of Snai2. The differences in survival rates are statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Table 2.

The effects of clinical and pathohistological parameters on prognosis*

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95%CI | p value | HR | 95%CI | p value | ||

| Gender | Female | 1 | |||||

| Male | 1.117 | 0.516 – 2.421 | 0.779 | ||||

| Age | ≤ 55 | 1 | |||||

| > 55 | 0.948 | 0.452 – 1.987 | 0.887 | ||||

| Grade | Well | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Mediate | 2.342 | 1.074 – 5.128 | 0.033 | 1.715 | 0.524 – 3.289 | 0.254 | |

| Poor | 3.278 | 0.767 – 14.925 | 0.108 | 1.852 | 0.320 – 10.753 | 0.492 | |

| Tumor Size | ≤ 4 cm | 1 | 1 | ||||

| > 4cm | 3.257 | 1.517 – 6.993 | 0.002 | 2.262 | 0.507 – 10.101 | 0.285 | |

| pT | pT1-2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| pT3-4 | 3.509 | 1.658 – 7.407 | 0.001 | 1.066 | 0.248 – 4.587 | 0.932 | |

| pN | Negative | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Positive | 5.848 | 2.469 – 13.889 | <0.001 | 1.525 | 0.283 – 8.227 | 0.624 | |

| Clinical stage | I–II | 1 | 1 | ||||

| III–IV | 6.894 | 2.381 – 20.000 | <0.001 | 5.952 | 0.697 – 50.000 | 0.103 | |

| Snai2 | Low | 1 | 1 | ||||

| High | 2.506 | 1.190 – 5.291 | 0.015 | 1.256 | 0.450 – 3.509 | 0.664 | |

| Vimentin | Low | 1 | 1 | ||||

| High | 4.695 | 1.901 – 11.628 | 0.001 | 3.145 | 0.944 – 10.526 | 0.062 | |

| E-cadherin | High | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Low | 15.152 | 3.597 – 62.500 | <0.001 | 9.709 | 1.718 – 55.556 | 0.010 | |

Analysis was done with Cox proportional hazard regression. HR: hazard ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

The effects of Snai2 on EMT in SCCOT cell lines

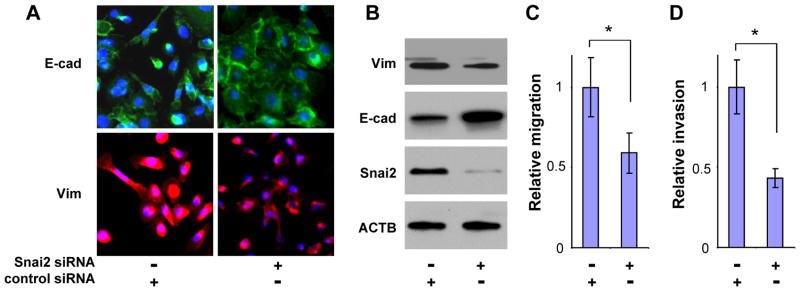

UM1 is a SCCOT cell line that expresses high levels of Snai2 and exhibits the mesenchymal phenotype (low E-cadherin expression, high Vimentin expression, Supplementary Figure 4). When UM1 cells were treated with Snai2-specific siRNA, the cells were switched from a mesenchymal-like morphology to an epithelial-like morphology (Figure 3A and Supplementary Figure 5). This morphological change was accompanied by increased E-cadherin expression and reduced Viemtnin expression (Figure 3A, 3B and Supplementary Figure 6), as well as reduced cell migration and invasion (Figure 3C and 3D). Similar results were observed in additional cell lines (Supplementary Figure 7A). When SCCOT cells were treated with Snai1-specific siRNA, enhanced E-cadherin expression and reduced Viemtnin expression were also observed (Supplementary Figure 7B).

Figure 3. Knock-down of Snai2 restores the epithelial phenotype in UM1 cells.

UM1 cells were transitely transfected with Snai2 specific siRNA or control siRNA. Fluorescent immunocytochemistry analyses were performed to detect the expression of E-cadherin (green) and Vimentin (red) in the intact cells (A). The expression of Snai2, E-cadherin and Vimentin were also measured by Western blots (B). Cell migration (C) and invasion (D) were significantly reduced when cells were treated with Snai2 specific siRNA. Data represents at least 3 independent experiments with similar results. * indicates p < 0.05.

SCC 9 is a SCCOT cell line that exhibits the epithelial phenotype and can undergo EMT upon TGFβ1-treatment (Supplemental Figure 8). As illustrated in Figure 4A, when SCC9 cells were pre-treated with Snai2 specific siRNA, the TGFβ1-induced down-regulation of E-cadherin was blocked. The TGFβ1-induced up-regulation of Vimentin was also partially attenuated. Similar results were observed in additional cell lines (Supplementary Figure 7C). The knockdown of Snai2 also blocked the TGFβ1-induced cell migration and invasion activities in SCC9 cells (Figure 4B and 4C). Furthermore, ectopic transfection of Snai2 led to reduced E-cadherine expression and enhanced Vimentin expression (Figure 4D), and these expressional changes were accompanied by enhanced cell migration (Figure 4E) and invasion (Figure 4F).

Figure 4. Enhanced expression of Snai2 induces EMT in SCC 9 cells.

SCC 9 cells were treated with siRNA specific to Snai2 or control siRNA. The cells were then treated with TGFβ1 for the induction of EMT (as illustrated in Supplementary Figure 5). The expression of EMT markers (E-cadherin and Vimentin) (A) and the cell migration (B) and invasion (C) were measured. SCC9 cells were transiently transfected with a Snai2 expression vector (Snai2 pcDNA), or an empty vector. The expression of E-cadherin and Vimentin (D), and the cell migration (E) and invasion (F) were measured. * indicates p < 0.05.

Discussion

Cancer cells can de-differentiate through activation of specific biological pathways associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), thereby gaining the ability to migrate and invade. Recently, a number of EMT regulators have been described, such as microRNA-200 family 36, ZEB family 37 and Snail family 15, 16. The members of Snail family of transcription factors are zinc-finger transcriptional repressors. There are three known members of Snail family genes in the human genome: Snai1, Snai2 and Snai3. A number of in vitro studies suggested that Snai1 contributes to EMT by repressing E-cadherin expression 17, 33, 38, 39. However, several recent in vivo studies demonstrated that Snai1 expression is limited in OSCC, and its deregulation may not be directly associated with metastasis in OSCCs 40, 41. Based on our pooled-analysis of the existing mRNA microarray dataset on SCCOTs, no statistical significant difference in Snai1 expression was observed between SCCOT samples and the normal control samples, or between SCCOT samples with or without lymph node metastasis (Supplementary Figure 1A). This is in agreement with the previous in vivo observations on OSCCs 40, 41. Furthermore, among the cell lines we tested, only 1386Ln exhibits detectable Snai1 expression (Supplementary Figure 4B). In addition, Snai3 expression was not detectable in our samples.

Unlike Snai1, the role of Snai2 in OSCC has not been investigated extensively. Our pooled-analysis of the existing mRNA microarray dataset demonstrated that Snai2 is over-expressed in SCCOT when compared to the normal control samples. Furthermore, a statistically significant increase in Snai2 expression was observed in SCCOT cases with lymph node metastasis when compared to cases without metastasis. We further confirmed this association of Sani2 overexpression and lymph node metastasis in a second SCCOT patient cohort based on IHC analysis. In addition, we also found that the overexpression of Sani2 correlates with advanced clinical stage and reduced overall survival. Furthermore, we observed a high level of Snai2 expression in the invasion front of the primary cancer. More importantly, the over-expression of Snai2 is associated with reduced E-cadherin expression and increased Vimentin expression. These results indicate that Snai2 may suppress the E-cadherin expression and induce EMT in SCCOT, which in turn contribute to invasion and metastasis.

To explore the functional relevance of Snai2 in SCCOT progression, we confirmed the roles of Snai2 in EMT in a set of in vitro experiments. Using the siRNA-based knockdown of the Snai2 gene, we were able to switch the SCCOT cells from a mesenchymal-like morphology to an epithelial-like morphology. This switch was accompanied by increased E-cadherin expression, decreased Vimentin expression, and reduced cell invasion and migration. In contrast, ectopic transfection of Snai2 led to reduced E-cadherin expression, enhanced Vimentin expression, and enhanced cell invasion and migration. We further demonstrated that knock-down of Snai2 can block the TGFβ1-induced EMT in SCCOT. Interestingly, Snai2 knock-down also leads to redistribution of E-cadherin from cytoplasmic to adherens junctions. These results suggest that Snai2 regulates EMT not only by repressing E-cahderin expression but also regulating the subcellular localization of E-cadherin in SCCOT.

The relative contributions of Snai1 and Snai2 to the induction of EMT are still unclear. Complementary roles of Snai1 and Sani2 have been previously proposed. While Snai1 is believed to initiate EMT by regulating the expression of basement membrane proteins, E-cadherin, and matrix metalloproteinase activities 33, 42, 43, Snai2 maintains the mesenchymal phenotype by sustaining the repression of E-cadherin 44. However, in some cancer types (e.g., bladder cancer), Snai2 appears to trigger EMT, whereas Snai1 acts later to complete the process by enhancing cell motility and initiating the switch from cytokeratin to Vimentin expression 45. Collaborative roles of Snai1 and Snai2 have also been suggested in skin cancer cell lines 46. In OSCC, both Snai1 and Snai2 have been showed to mediate TGFβ1-induced induction of MMP9 expression, suppression of E-cadherin expression, and enhancement of cell invasion 20, 33. Our knockdown experiment also confirmed that both Snai1 and Snai2 regulate E-cadherin expression in vitro (Supplementary Figure 7A and 7B). However, no apparent change in Snai1 protein level and slight down-regulation of Snai1 mRNA was observed in SCCOT cell lines treated with TGFβ1, whereas Snai2 was significantly up-regulated (data not shown). The TGFβ1-induced up-regulation of Snai2 was accompanied by dramatic down-regulation of E-cadherin expression (data not show). Similar observations were reported by other SCCOT cell lines 43. These observations further illustrate the different roles of Snail family members in different cancer types, and Snai2 may serve as a novel therapeutic target for metastatic SCCOT. It is possible that in SCCOT, Snai2 is responsible for both initiating and maintaining EMT. Furthermore, the observed differences in in vitro studies may be cell line specific. It is possible that the cell lines we tested here (or the cell line used in the previous study) may have specific mutation(s) that dictates the effects of Snai1 and Snai2 in EMT. More in-depth functional analysis will be needed to fully evaluate the potential differential effects of Snai1 and Snai2 in EMT, as well as to assess the feasibility of utilizing Snai2 as biomarkers or therapeutic target for SCCOT patients at risk of metastasis. Nevertheless, our results suggest that Snai2 plays an important role in EMT and the progression of SCCOT.

While our retrospective analysis revealed a striking difference in the 5-year survival rate between the high Snai2 expressing patient group (< 50%) and the low Snai2 expressing patient group (> 70%), Snai2 appears not to be an independent prognostic factor. This may be due to the apparent correlation between enhanced Snai2 expression and EMT (characterized by reduced E-cadherin expression and enhanced Vimentin expression), which is associated with metastasis and disease progression. This is in agreement with the observed statistically significant increases in Snai2 expression in SCCOT cases with lymph node metastasis. These observations suggest that to achieve optimized prognostic assessment, it is important to integrate Snai2 with EMT-related markers (e.g., E-cadherin and Vimentin), as well as clinical and pathohistological parameters. Additional studies with larger sample sizes will be needed to fully explore the prognostic values of these markers.

In summary, our results demonstrate that Snai2 deregulation is a frequent event in SCCOT, and is associated with disease progression. One of its major roles in SCCOT progression is promoting EMT which will enhance cancer cell migration, invasion and metastasis. Additional studies will be needed to fully explore the molecular mechanisms that contribute to the deregulation of Snai2 in SCCOT, and its potential as a biomarker and a novel therapeutic target for SCCOT patients at risk of metastasis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Natural Science Grant of China (81072223 and 30700952), and NIH PHS grants (CA135992, CA139596, DE014847) and supplementary funding from UIC CCTS (UL1RR029879). We thank Ms. Katherine Long for her editorial assistance.

Abbreviation

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- OSCC

oral squamous cell carcinomas

- pN

pathological N-stage

- pT

pathological T-stage

- SCCOT

squamous cell carcinoma of oral tongue

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: None declared.

References

- 1.Timar J, Csuka O, Remenar E, Repassy G, Kasler M. Progression of head and neck squamous cell cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2005;24:107–27. doi: 10.1007/s10555-005-5051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franceschi D, Gupta R, Spiro RH, Shah JP. Improved survival in the treatment of squamous carcinoma of the oral tongue. Am J Surg. 1993;166:360–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80333-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Layland MK, Sessions DG, Lenox J. The influence of lymph node metastasis in the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, oropharynx, larynx, and hypopharynx: N0 versus N+ Laryngoscope. 2005;115:629–39. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000161338.54515.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham MJ, Johnson JT, Myers EN, Schramm VL, Jr, Thearle PB. Cervical lymph node metastasis after local excision of early squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Am J Surg. 1986;152:361–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(86)90305-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ho CM, Lam KH, Wei WI, Lau SK, Lam LK. Occult lymph node metastasis in small oral tongue cancers. Head Neck. 1992;14:359–63. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880140504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuen AP, Lam KY, Chan AC, Wei WI, Lam LK, Ho WK, Ho CM. Clinicopathological analysis of elective neck dissection for N0 neck of early oral tongue carcinoma. Am J Surg. 1999;177:90–2. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00294-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sano D, Myers JN. Metastasis of squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:645–62. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9082-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, Eaton EN, Ayyanan A, Zhou AY, Brooks M, Reinhard F, Zhang CC, Shipitsin M, Campbell LL, Polyak K, et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:704–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1420–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI39104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Acloque H, Thiery JP, Nieto MA. The physiology and pathology of the EMT. Meeting on the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:322–6. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halbleib JM, Nelson WJ. Cadherins in development: cell adhesion, sorting, and tissue morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3199–214. doi: 10.1101/gad.1486806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu LK, Jiang XY, Zhou XX, Wang DM, Song XL, Jiang HB. Upregulation of vimentin and aberrant expression of E-cadherin/beta-catenin complex in oral squamous cell carcinomas: correlation with the clinicopathological features and patient outcome. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:213–24. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, Zhang J, Fan M, Zhou Q, Deng H, Aisharif MJ, Chen X. The expression of E-cadherin at the invasive tumor front of oral squamous cell carcinoma: immunohistochemical and RT-PCR analysis with clinicopathological correlation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107:547–54. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barrallo-Gimeno A, Nieto MA. The Snail genes as inducers of cell movement and survival: implications in development and cancer. Development. 2005;132:3151–61. doi: 10.1242/dev.01907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nieto MA. The snail superfamily of zinc-finger transcription factors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:155–66. doi: 10.1038/nrm757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higashikawa K, Yoneda S, Tobiume K, Taki M, Shigeishi H, Kamata N. Snail-induced down-regulation of DeltaNp63alpha acquires invasive phenotype of human squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9207–13. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Onoue T, Uchida D, Begum NM, Tomizuka Y, Yoshida H, Sato M. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition induced by the stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXCR4 system in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. Int J Oncol. 2006;29:1133–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bauer K, Dowejko A, Bosserhoff AK, Reichert TE, Bauer RJ. P-cadherin induces an epithelial-like phenotype in oral squamous cell carcinoma by GSK-3beta-mediated Snail phosphorylation. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1781–8. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joseph MJ, Dangi-Garimella S, Shields MA, Diamond ME, Sun L, Koblinski JE, Munshi HG. Slug is a downstream mediator of transforming growth factor-beta1-induced matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression and invasion of oral cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2009;108:726–36. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ye H, Yu T, Temam S, Ziober BL, Wang J, Schwartz JL, Mao L, Wong DT, Zhou X. Transcriptomic dissection of tongue squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Donnell RK, Kupferman M, Wei SJ, Singhal S, Weber R, O’Malley B, Cheng Y, Putt M, Feldman M, Ziober B, Muschel RJ. Gene expression signature predicts lymphatic metastasis in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Oncogene. 2005;24:1244–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toruner GA, Ulger C, Alkan M, Galante AT, Rinaggio J, Wilk R, Tian B, Soteropoulos P, Hameed MR, Schwalb MN, Dermody JJ. Association between gene expression profile and tumor invasion in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2004;154:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2004.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ziober AF, Patel KR, Alawi F, Gimotty P, Weber RS, Feldman MM, Chalian AA, Weinstein GS, Hunt J, Ziober BL. Identification of a gene signature for rapid screening of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5960–71. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.R_Development_Core_Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, Hornik K, Hothorn T, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu T, Ye H, Chen Z, Ziober BL, Zhou X. Dimension reduction and mixed-effects model for microarray meta-analysis of cancer. Front Biosci. 2008;13:2714–20. doi: 10.2741/2878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Irizarry RA, Bolstad BM, Collin F, Cope LM, Hobbs B, Speed TP. Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu X, Wang A, Lo Muzio L, Kolokythas A, Sheng S, Rubini C, Ye H, Shi F, Yu T, Crowe DL, Zhou X. Deregulation of manganese superoxide dismutase (SOD2) expression and lymph node metastasis in tongue squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:365. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang A, Liu X, Sheng S, Ye H, Peng T, Shi F, Crowe DL, Zhou X. Dysregulation of heat shock protein 27 expression in oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:167. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu X, Jiang L, Wang A, Yu J, Shi F, Zhou X. MicroRNA-138 suppresses invasion and promotes apoptosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Lett. 2009;286:217–22. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu X, Yu J, Jiang L, Wang A, Shi F, Ye H, Zhou X. MicroRNA-222 Regulates Cell Invasion by Targeting Matrix Metalloproteinase 1 (MMP1) and Manganese Superoxide Dismutase 2 (SOD2) in Tongue Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cell Lines. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2009;6:131–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun L, Diamond ME, Ottaviano AJ, Joseph MJ, Ananthanarayan V, Munshi HG. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 promotes matrix metalloproteinase-9-mediated oral cancer invasion through snail expression. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:10–20. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diamond ME, Sun L, Ottaviano AJ, Joseph MJ, Munshi HG. Differential growth factor regulation of N-cadherin expression and motility in normal and malignant oral epithelium. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:2197–207. doi: 10.1242/jcs.021782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang L, Liu X, Kolokythas A, Yu J, Wang A, Heidbreder CE, Shi F, Zhou X. Down-regulation of the Rho GTPase signaling pathway is involved in the microRNA-138 mediated inhibition of cell migration and invasion in tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:505–12. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gregory PA, Bracken CP, Bert AG, Goodall GJ. MicroRNAs as regulators of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3112–8. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.20.6851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmalhofer O, Brabletz S, Brabletz T. E-cadherin, beta-catenin, and ZEB1 in malignant progression of cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:151–66. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9179-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takkunen M, Ainola M, Vainionpaa N, Grenman R, Patarroyo M, Garcia de Herreros A, Konttinen YT, Virtanen I. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition downregulates laminin alpha5 chain and upregulates laminin alpha4 chain in oral squamous carcinoma cells. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;130:509–25. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0443-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yokoyama K, Kamata N, Hayashi E, Hoteiya T, Ueda N, Fujimoto R, Nagayama M. Reverse correlation of E-cadherin and snail expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells in vitro. Oral Oncol. 2001;37:65–71. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwock J, Bradley G, Ho JC, Perez-Ordonez B, Hedley DW, Irish JC, Geddie WR. SNAI1 expression and the mesenchymal phenotype: an immunohistochemical study performed on 46 cases of oral squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Clin Pathol. 10:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6890-10-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Franz M, Spiegel K, Umbreit C, Richter P, Codina-Canet C, Berndt A, Altendorf-Hofmann A, Koscielny S, Hyckel P, Kosmehl H, Virtanen I, Berndt A. Expression of Snail is associated with myofibroblast phenotype development in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Histochem Cell Biol. 2009;131:651–60. doi: 10.1007/s00418-009-0559-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haraguchi M, Okubo T, Miyashita Y, Miyamoto Y, Hayashi M, Crotti TN, McHugh KP, Ozawa M. Snail regulates cell-matrix adhesion by regulation of the expression of integrins and basement membrane proteins. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:23514–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801125200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qiao B, Johnson NW, Gao J. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in oral squamous cell carcinoma triggered by transforming growth factor-beta1 is Snail family-dependent and correlates with matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 expressions. Int J Oncol. 2010;37:663–8. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hotz B, Arndt M, Dullat S, Bhargava S, Buhr HJ, Hotz HG. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition: expression of the regulators snail, slug, and twist in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4769–76. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Savagner P, Yamada KM, Thiery JP. The zinc-finger protein slug causes desmosome dissociation, an initial and necessary step for growth factor-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1403–19. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olmeda D, Montes A, Moreno-Bueno G, Flores JM, Portillo F, Cano A. Snai1 and Snai2 collaborate on tumor growth and metastasis properties of mouse skin carcinoma cell lines. Oncogene. 2008;27:4690–701. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.