Abstract

Despite the importance of water-soluble vitamins to metabolism, there is limited knowledge of their serum availability in fasting wildlife. We evaluated changes in water-soluble vitamins in northern elephant seals, a species with an exceptional ability to withstand nutrient deprivation. We used a metabolomics approach to measure vitamins and associated metabolites under extended natural fasts for up to seven weeks in free-ranging lactating or developing seals. Water-soluble vitamins were not detected with this metabolomics platform, but could be measured with standard assays. Concentrations of measured vitamins varied independently, but all were maintained at detectable levels over extended fasts, suggesting that defense of vitamin levels is a component of fasting adaptation in the seals. Metabolomics was not ideal for generating complete vitamin profiles in this species, but gave novel insights into vitamin metabolism by detecting key related metabolites. For example, niacin level reductions in lactating females were associated with significant reductions in precursors suggesting downregulation of the niacin synthetic pathway. The ability to detect individual vitamins using metabolomics may be impacted by the large number of novel compounds detected. Modifications to the analysis platforms and compound detection algorithms used in this study may be required for improving water-soluble vitamin detection in this and other novel wildlife systems.

Keywords: metabolomics, water-soluble vitamins, vitamin homeostasis, vitamins, fasting, fasting-adapted, northern elephant seals

1. Introduction

Most animals feed intermittently requiring a transition from absorptive to post-absorptive metabolic states. From this perspective, fasting is a necessary component of the life history of animals; be it fasting for a few hours between meals, overnight during sleep, or over months of hibernation (Castellini and Rea, 1992). Animals vary widely in their ability to withstand fasting, ranging from species that use circadian torpor to survive nightly fasts (Bartholomew and Trost, 1970; Lasiewski, 1963) to species adapted for extended high-energy fasting as part of their life history (Crocker et al. 2001). In fasting-adapted species, multiple physiological and behavioral mechanisms allow strategic use of body reserves in a way that spares vital organs and extends the fasting duration. Fasting animals may minimize energetically costly activities like locomotion and thermoregulation, thereby reducing net nutrient catabolism. In contrast, certain other species, including marine mammals and marine birds, pursue energetically expensive activities such as migration, reproduction, lactation, or development during periods of fasting (Castellini and Rea, 1992; Cherel et al., 1988).

Behavioral and physiological fasting responses have been studied in many species of wildlife, yet one aspect that has not been examined is the impact of fasting on levels of water-soluble vitamins and their availability to support metabolism. Past vitamin studies in wildlife have focused on fat-soluble vitamins (Crissey and Wells, 1999; Dierenfeld, 1989, 1994, 1999, Gelatt et al., 1999; Slifka et al., 1999), with very few concerning fasting species (Debier et al., 2002a;b; Schweigert et al., 2002; 1990). Fat-soluble vitamins can be stored and released from adipose tissue or the liver, making them available during fasting as fat is catabolized. However, water-soluble vitamins vary widely in their ability for synthesis, storage, and rates of turnover in the plasma and body (Rumsey and Levine, 1998; Scott, 1999). Plasma excesses are readily excreted in urine and thus many water-soluble vitamins are generally needed in a constant dietary supply (Robbins and Mathison, 1983). Water-soluble vitamins, therefore, may pose a potential dilemma for fasting animals. These vitamins are required as enzyme cofactors or chemical precursors for a diverse set of metabolic reactions. Ascorbic acid, riboflavin (B2) and niacin (B3) are critical in redox reactions; Pantothenic acid (B5), thiamine (B1) and biotin are essential to macronutrient metabolism; and cobalamin (B12), pyroxidine (B6) and riboflavin (B2) play key roles in the regulation of S-adenosylmethionine production and DNA synthesis. Comparison values in wildlife systems are few and often have small sample sizes (Schweigert et al., 1987; Shochat et al., 1998), therefore most of what we know about vitamin responses to fasting is from clinical studies in humans, rats, or mice. It is currently unknown how limitations in vitamin synthesis, intake, or storage interact with metabolic adaptations for fasting in wildlife.

From a biochemical perspective the factors that are most crucial in determining the turnover and availability of water-soluble vitamins in absence of nutrient input are chemical stability, interaction with enzymes of specific binding proteins, cellular compartmentalization and sequestration, the presence or absence of synthetic or regenerative pathways, and the relative number of catalytic events associated with use of the vitamin as a cofactor (Rucker and Steinberg 2002). Half-lives of vitamins in simple solutions at mammalian body temperatures are on the order of minutes to hours but can extend to months when stabilized by sequestration or binding to proteins (Smith et al. 1998). Vitamins that have daily requirements in millimolar amounts, such as ascorbate, niacin and pantothenic acid, are less chemically stable, and are involved in many metabolic reactions. For example, in addition to its role as a cofactor, niacin serves as a substrate in ribosylation reactions (Kirkland et al.2001). Vitamins required in micromolar amounts, like cobalamin are often covalently bound to transport proteins or the enzymes for which they serve as cofactors (Rucker and Steinberg 2002) and used in a comparatively limited number of enzymatic steps, hence their lower dietary requirements. In the broadest sense, it has been suggested that as vitamin metabolism is linked to cell metabolism, interspecific variation in dietary requirements of water-soluble vitamins are largely the result of differences in oxygen utilization and energy expenditure between species (Rucker and Steinberg 2002). However, to date no studies have examined the relationship of metabolic adaptation to fasting to vitamin metabolism.

Extended fasting is associated with increased emphasis on lipolysis and fatty-acid oxidation for fuel metabolism (Houser et al. 2007). Many water-soluble vitamins play important roles in fatty acid metabolism, particularly pantothenic acid, a component of coenzyme-A, required for fatty acid oxidation. It is unknown how metabolic adaptation to prioritize fatty-acid metabolism influences vitamin requirements. Similarly ascorbate is required for the synthesis of carnitine which is essential to fatty acid oxidation. Also interesting from the viewpoint of fasting are vitamins like pantothenic acid and cobalamin which cannot be synthesized endogenously and are thus dependent on dietary input but vary widely in their capacity for storage. Lastly, vitamins also play important roles as defenses against reactive oxygen species (Beckman and Ames 1998). Fasting is associated with increases in oxidative stress (Martensson 1986, Vasquez-Medina 2010) and it is unknown if this influences degradation or requirements of vitamins. It is widely assumed that fasting carnivores rely on gut microflora biosynthesis to fulfill some vitamin requirements of the host, but the scientific literature concerning this is sparse (Hooper, 2002; Said, 2004) and often contradictory. As these vitamins are required to maintain basal metabolic processes, vitamin homeostasis may impact fasting duration by acting as a limiting resource. If this is the case, it may be an important unexamined factor in shaping the reproductive, foraging, and migration patterns of animals in both fasting adapted and non-fasting adapted species.

Not only are studies on wildlife serum vitamin levels rare, most published studies measure a single vitamin, or fat-soluble vitamins A and E together, at a single time point (Debier et al., 1999; Schweigert et al., 1987, 1990). This is at least partly driven by sample limitations with large sample volumes required for multiple individual analyses using standard spectrophotometric, microbiological or chromatographic methods. One method that has potential for use in studying the homeostasis of a suite of water-soluble vitamins, as well as a variety of their precursors and end products, using small sample volumes, is the use of metabolomic techniques. Metabolomics analysis allows the measurement of many small molecule metabolites in order to analyze metabolic processes by global biochemical changes between two time-points or states. This innovative approach has been increasingly used to answer physiological questions including vitamin measurement studies of humans and rats (Llorach et al., 2009; Satake et al., 2003); however it has not yet been widely applied to the realm of wildlife physiology and vitamin homeostasis. One potential limitation that complicates interpretation of these data is the detection of novel compounds, those not in the database used for analysis. Novel compounds may overlap or confound detection of standard metabolites. This limits the ability of the approach to confirm presence or absence of a compound because the detection libraries are not optimized for individual wildlife species. Nonetheless, this broad-based metabolite analysis has the potential to identify vitamins and any molecules involved in vitamin metabolism, providing a unique view of vitamin homeostasis previously undescribed in wildlife systems, as well as in fasting physiology.

Some phocid seals provide excellent systems within which to examine water-soluble vitamin homeostasis because they regularly engage in long-term fasting as part of their life history. However, to date, only two studies have investigated water-soluble vitamins in a phocid seal, the grey seal (Halichoerus grypus). These studies used single time-point measurements during fasting and demonstrated that grey seals have serum vitamin C levels similar to values found in terrestrial mammals (Schweigert, 1993; Schweigert et al., 1987). Another member of the phocidae, the northern elephant seal (Mirounga angustirostris), experiences extended fasts of up to three months during periods of reproduction and development (Costa et al., 1986; Crocker et al., 2001; Le Boeuf, 1974; Reiter et al., 1978; Thorson and Le Boeuf, 1994). Reproduction and development while fasting require significant mobilization and utilization of nutrient reserves as well as de novo synthesis of new compounds. Lactating female elephant seals synthesize one of the most energy rich milks found in nature while fasting for four weeks (Crocker et al., 2001). Weaned pups fast for up to three months while they increase hemoglobin and myoglobin concentrations, red blood cell volume, and mass-specific blood volume (Thorson and Le Boeuf, 1994), all of which are required for successful diving and foraging at sea. Weanlings also begin development of diving behavior during this time (Reiter et al., 1978). These processes utilize water-soluble vitamins as cofactors and precursor molecules required for energy metabolism, biosynthesis, and many other aspects of metabolism. This study investigated how fasting might impact the dynamics of water-soluble vitamins; we further capitalized on a metabolomics approach to assess the vitamins in the context of a broad suite of related metabolites. Our objectives were to evaluate: 1) fasting water-soluble vitamin homeostasis in a fasting adapted species, the northern elephant seal, and 2) the use of metabolomics in studying vitamin homeostasis in wildlife species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Field Procedures

Sampling procedures were conducted at Año Nuevo State Park, San Mateo County, CA, USA during the 2009 breeding season, January through April. Upon arrival at the rookery, adult females were marked with hair dye (Lady Clairol, Stamford, CT, USA) to facilitate identification. Daily surveys provided arrival and parturition dates for each female subject, as well as observations to ensure that appropriate mother-pup bonding was established. Pups were given plastic flipper tags (jumbo roto-tags; Dalton Company, Oxon, UK) at weaning and were also marked with hair dye.

Blood samples were collected from ten lactating females and ten unrelated weaned pups. Samples from females were collected five days post-partum (early lactation) and 22 days post-partum (late lactation). Samples from weaned pups were collected in the second week post-weaning (early fast) and in the sixth week post-weaning (late fast). This time frame reflects the duration of the natural fast the seals undergo at this time. Subjects were chemically immobilized using an initial intramuscular injection of 1.0 mg/kg Telazol (teletamine/zolazepam HCl) and immobilization was maintained using intravenous injections of ketamine as needed. Blood samples were taken in pre-chilled EDTA and serum vacutainers and kept on ice during field procedures. Samples were returned to the laboratory immediately after procedures and centrifuged for 25 min at 4 °C and 2000 g. Plasma or serum was extracted and frozen at −80 °C. At both time points seals were weighed with a digital scale (capacity 1000 kg, accuracy +/− 1 kg, Dyna-Link MSI-7200, Measurement Systems International, Seattle, Washington, USA) mounted to a tripod.

2.2 Vitamin analyses

Broad-scale metabolite analysis was performed by Metabolon, Inc. (Raleigh, NC, USA). Plasma (EDTA) samples were divided into two fractions for the dual portion platform. The Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS, LC-MS2) portion of the platform is based on a Waters Acquity UPLC and a Thermo-Finnigan LTQ mass spectrometer. The Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectroscopy (GC-MS) column was 5% phenyl and the temperature ramp was from 40 °C to 300 °C over a 16 min period. Peaks within the MS output were identified using Metabolon’s proprietary peak integration software; peaks which did not meet quality control limits were not included. Biochemicals were identified by comparison to library entries of 1500 commercially available purified standards, or recurrent unknown entities. Metabolites were then registered to the Metabolon’s laboratory information system for determination of their analytical characteristics. The combination of chromatographic properties and mass spectra give an indication of a match to the specific compound or an isobaric entity, another molecule of the same molecular weight. Each metabolite detected and identified off of the columns was examined for relative changes in quantity across the fasting period. This platform identified changes in levels of many water-soluble vitamin breakdown products and precursors; however, it detected no water-soluble vitamins.

Samples were subsequently analyzed for confirmation of the presence and concentration of a subset of four water-soluble vitamins using standard microbiological and colorimetric methods. The four vitamins measured were chosen to gain information on a variety of different vitamin types, as well as to focus on ones that may specifically play a crucial role in fasting physiology. Vitamins were measured in serum using Vitamin B12 Microbiological Test Kit, Pantothenic Acid Microbiological Assay, Vitamin B3 (Niacin) Microbiological Test Kit (Catalog # 30-KIF012, 30-KIF004, 30-KIF003, respectively, ALPCO, Salem, NH, USA), and Ascorbic Acid Assay Kit II (FRASC) (Catalog # K671-100, BioVision, Mountain View, CA, USA). It is important to note all vitamin concentration measurements were made in plasma and serum samples. Therefore, measured levels do not reflect whole body stores, but the level of circulating vitamins available to other tissues for utilization.

2.4 Statistics

Metabolomics data were analyzed using t-tests comparing the median scaled data between fasting periods, i.e. the early fasting period was compared to the late fasting period. All peak areas for individual metabolites were scaled to the early fast sample median. Absolute values of elephant seal vitamins were analyzed using a linear mixed effects model, with seal as a random effect subject term (SAS v 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Model residuals were examined for approximate normality and the response variable was log-transformed when necessary. Significant differences between fasting groups were assessed using post-hoc comparisons of least square means differences.

3. Results

The dual-platform metabolomics analysis of elephant seal plasma detected no water-soluble vitamins. However, decreases in the niacin metabolites kyneurinine and tryptophan (in lactating females only) were detected, as well as a decrease in threonate, a metabolite of vitamin C, in the weaned pups. Trigonelline, a third niacin metabolite, was detected in both female and weaned pup samples with no significant changes across the fast. Additionally, alpha-tocopherol (Vitamin E) was detected in both age classes; however neither vitamin A nor any of its metabolites were detected. Changes in the vitamin-related metabolites in elephant seal plasma are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Metabolomics median scaled values for each of the groups, lactating female elephant seals and weaned pup elephant seals.

| Female Elephant Seals | Elephant Seal Pups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL/EL | t | p | LF/EF | t | p | |

| Ascorbate (Vitamin C) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Threonate (Vitamin C break-down product) | 0.98 | -0.11 | 0.92 | 0.49 | 4.59 | 0.0013 |

| Pantothenic acid (Vitamin B5) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Riboflavin (Vitamin B2) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Pyridoxate (Vitamin B6 break-down product) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Trigonelline (Niacin break-down product) | 0.97 | −0.13 | 0.90 | 0.77 | −1.17 | 0.27 |

| Alpha-tocopherol (Vitamin E) | 1.02 | −0.36 | 0.73 | 1.03 | 1.36 | 0.21 |

| Kynurenine (Niacin precursor) | 0.50 | −6.67 | <0.0001 | 0.72 | −4.68 | 0.0012 |

| Tryptophan (Niacin precursor) | 0.72 | −5.13 | 0.0006 | 0.83 | −0.11 | 0.92 |

LL/EL = the ratio of late lactation to early lactation values, LF/EF = the ratio of late fast to early fast values, p = p-value, bold values indicate significant differences, ‘-’ = not detected.

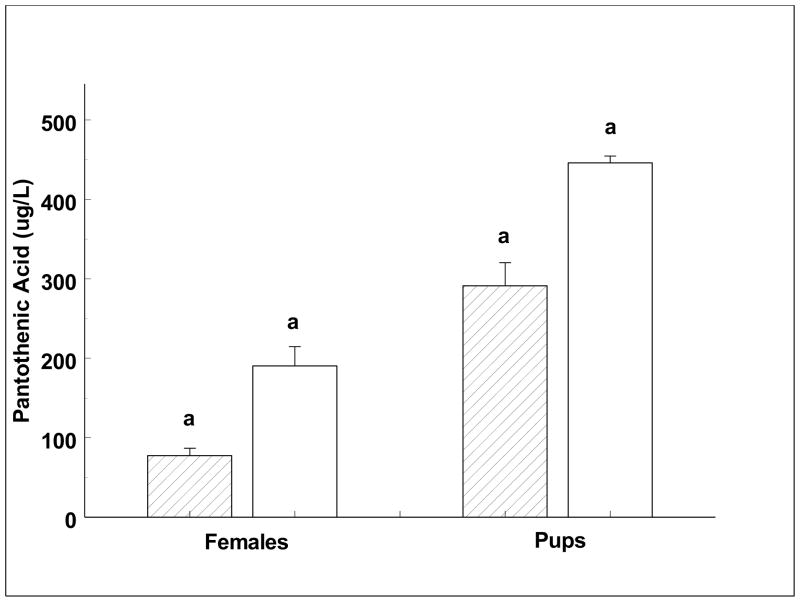

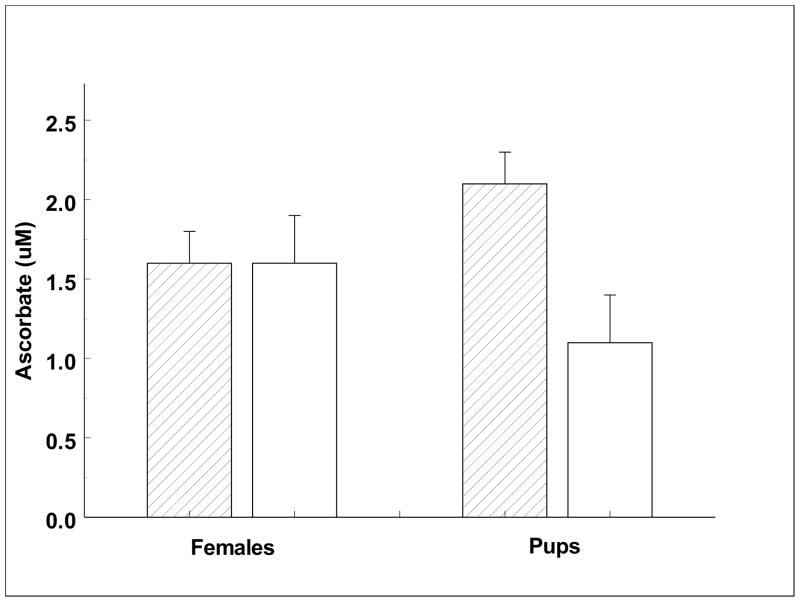

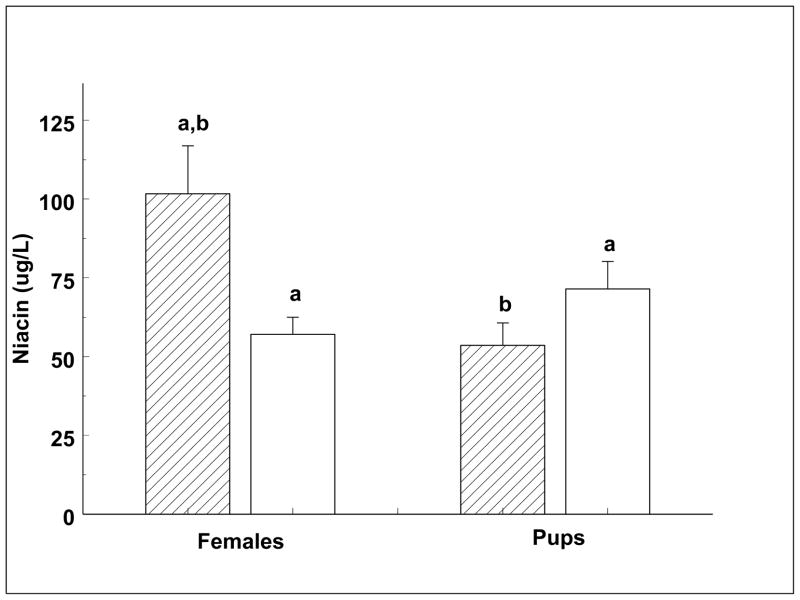

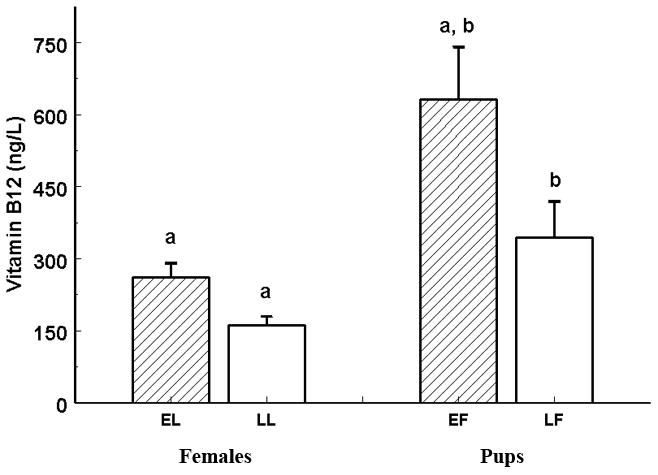

Absolute concentrations of a subset of four vitamins assayed using standard microbiological and colorimetric methods are shown in Table 2, with individual vitamin changes shown in Figures 1–4. Pantothenic acid measurements increased significantly across the females’ and the weaned pups’ fast (Fig. 1). Mean pup pantothenic acid concentrations were significantly greater than female values (Fig. 1). Ascorbate values were low when compared to other species and measurements did not change significantly between any time points. However, the pups showed a trend of decreasing in serum ascorbic acid concentrations across the fast (p = 0.09; Fig. 2). Niacin decreased significantly across the fast in adult females between early and late lactation (Fig. 3). Weaned pups showed no significant change in niacin levels across the fast. Early lactation females had a significantly higher niacin concentration than pups across the fast (Fig. 3). Vitamin B12 decreased significantly across the females’ and weaned pups’ fast (Fig. 4). Serum vitamin B12 concentrations were significantly greater at weaned pups’ early fast time point than that of females’ at either time point (Fig. 4).

Table 2.

Mean absolute values of northern elephant seal serum vitamin concentrations.

| EL | LL | p | EF | LF | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascorbate (Vitamin C) (ug/mL) | 0.284 | 0.282 | 0.97 | 0.361 | 0.279 | 0.090 |

| Pantothenic acid (Vitamin B5) (ug/L) | 77.7 | 190.4 | <.0001 | 291.5 | 446.1 | 0.0056 |

| Niacin (Vitamin B3) (ug/L) | 101.7 | 57.1 | 0.0028 | 53.6 | 71.5 | 0.18 |

| Vitamin B12 (ng/L) | 261.6 | 161.1 | 0.0006 | 631.7 | 344 | <.0001 |

EL = early lactation, LL = late lactation, EF = early fast, LF = late fast, p= p-value, bold values indicate significant differences.

Fig. 1.

Serum pantothenic acid concentrations of lactating females and weaned pups across their respective fasts.

Diagonal fill = early lactation or early fast. No fill = late lactation or late fast. Like letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Serum vitamin B12 concentrations of lactating females and weaned pups across their respective fasts.

Diagonal fill = early lactation or early fast. No fill = late lactation or late fast. Like letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Serum ascorbate concentrations of lactating females and weaned pups across their respective fasts.

Diagonal fill = early lactation or early fast. No fill = late lactation or late fast. There were no significant differences (p < 0.05) found.

Fig. 3.

Serum niacin concentrations of lactating females and weaned pups across their respective fasts. Niacin concentrations varied between fasting groups (p < 0.01).

Diagonal fill = early lactation or early fast. No fill = late lactation or late fast. Like letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

4.1 Vitamins

The metabolomics platform detected no water-soluble vitamins in the northern elephant seal plasma; in order to confirm these results, the absolute concentrations of a subset of four water-soluble vitamins were measured using alternate methods. All four vitamins were detected within measurement ranges of commercially available assay kits. Water-soluble vitamin serum concentrations in northern elephant seals changed independently of each other; they did not all consistently decrease across their extended natural fasts. Water-soluble vitamin concentrations also showed different patterns across the fast between the two age classes for only one out of four vitamins measured. This indicates that despite smaller body reserves and the constraints of development, northern elephant seal pups are capable of maintaining vitamin homeostasis while fasting almost as well as lactating females. The differences seen are most likely due to the increased levels of energy expenditure, and potential loss of vitamins in the milk. The similar pattern of serum vitamin concentration changes between lactating females and weaned pups, along with the fact that the females had smaller changes in each case, may also indicate tighter regulation of water-soluble vitamins during a period of fasting.

Most surprisingly, pantothenic acid (vitamin B5) serum concentrations increased across the natural fasts in seals of both age classes. Pantothenic acid cannot be produced in animals; its de novo biosynthesis is restricted to microorganisms and plants, while mammals must obtain it through diet (Ottenhof et al., 2004). Pantothenic acid is the universal precursor for coenzyme A (CoA) and acyl carrier protein, co-factors essential for key metabolic and energy-yielding pathways of all living cells (Kleinkauf, 2000). CoA mediates acyl transfer reactions in over 70 enzymatic pathways and is found in the diverse pathways of cholesterol synthesis, heme synthesis, amino acid catabolism, and acetylcholine synthesis (Ryter and Tyrrell, 2000; Smith and Song, 1996), and is a crucial substrate in the beta-oxidation of fatty acids (O’Brien and Frerman, 1977). As a key factor in lipid metabolism, the primary source of energy during the extended natural fasts of northern elephant seals, pantothenic acid is of particular interest to this study. In cases of pantothenic acid deficiency, CoA levels are not altered. This suggests an effective conservation of pantothenic acid potentially by a recycling mechanism that utilizes degradation products of pantothenic acid-containing molecules (Tahiliani and Beinlich, 1991). The increased levels of pantothenic acid seen in the seals may represent increased demand for the vitamin to support increased rates of nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA) release with the progression of the fast (Houser et al., 2007; McDonald and Crocker, 2006). This may be particularly important to lactating females as they direct more of their fat stores towards milk production. By comparison, plasma pantothenic acid in lactating dairy cows is only 7.5% of the average serum concentrations measured in lactating elephant seals (Dubeski and Owens, 1993). The fat content of cow’s milk is on average 3.67% (Barbano et al., 1992), which is relatively low compared to the 15–55% fat content of northern elephant seals milk (Riedman and Ortiz, 1979). It follows that lactating seals mobilize greater quantities of fat to support milk production, potentially requiring higher demands for a vitamin which functions prominently in fat metabolism. The highest levels of pantothenic acid were found in suckling pups, suggesting efficient placental and milk transfer of this vitamin. This difference is consistent with the reported increased need for pantothenic acid in developing young (Unna and Richards 1942).

The effects of diabetes and fasting on pantothenic acid metabolism have been studies in rats (Reibel et al. 1981). These studies found that both fasting and diabetes resulted in increased hepatic uptake and reduced muscle uptake of pantothenic acid, shifting the large muscle store of the vitamin to the liver where it was available to support energy metabolism for fasting. The shift may allow muscle storage of pantothenic acid to supplement the low storage capacity of the liver for the vitamin during nutrient deprivation. This same study also found reduced excretion of pantothenic acid during fasting, suggesting a regulatory mechanism to conserve whole-body levels. This reduced excretion is consistent with increases we found in absence of dietary input.

No significant difference in serum ascorbate levels were observed between early and late in the fast in either lactating females or weaned pups, suggesting the potential for endogenous biosynthesis of ascorbate in northern elephant seals. Ascorbate can be synthesized de novo by most animals, with the exception of several species including humans, other primates, guinea pigs (Burns, 1957; Burns et al., 1956), some fish (Halver et al., 1969), bats (Birney et al., 1976), and many passeriform birds (Chaudhuri and Chatterjee, 1969). This finding was in contrast to a previous study (Moore, 1980), a PhD thesis that suggested northern elephant seals cannot synthesize ascorbate. Moore measured gulonolactone oxidase activity in marine mammal livers to determine the presence of ascorbate biosynthesis. Activity in northern elephant seal samples (n=2) was comparable to the activity found in accepted non-synthesizers; however, samples were opportunistically collected without quality controls, in some cases from deceased specimens. For instance, time between animal death and sampling, and time between sampling and assays were unknown. The plasma half-life of ascorbate in humans was found to be approximately 7 to 14 days (Rumsey and Levine, 1998), though it decreases with increasing total turnover (Kallner et al., 1979). Based on modeling derived from radiolabelled ascorbate flux measurements, estimates have been made that 2.6 – 4.1% of ascorbate is lost from a theoretical total body pool per day (Rumsey and Levine, 1998). With a conservative estimate of 2% ascorbate loss per day, by 50 days with no ascorbate replacement, an animal should theoretically have extremely depleted or no ascorbate stores. Yet, after six weeks of fasting for the weaned pups, and between day five and day 22 fasting for the lactating females, the seals did not significantly reduce plasma levels. This suggests a capacity for ascorbate synthesis in elephant seals. Increased age may be negatively correlated with amount of ascorbate synthesized, as is seen in some animals such as rats (Lykkesfeldt, et al., 1998), however that was not seen in this study.

Average serum concentration was 0.3 ug/mL ascorbate, only 1.7 – 10% of typical human values (Dhariwal et al., 1991) and 7.2% of average values for the dairy cow, Bos primigenius (Dubeski and Owens, 1993). Values were dramatically lower (~3%) than those reported for fasting grey seals (Schweigert et al. 1987). The mean serum ascorbate concentration in the seals was only 15% of the accepted level for marginal ascorbate deficiency and 7% for scurvy in humans (Gey et al., 1987). Despite stable values across the fast, the low values may reflect a lower synthetic capacity in this species. Initially it seems surprising that ascorbate, a well known anti-oxidant (Carr and Frei, 1999), would be found at such low concentrations in an animal with a high potential to exhibit oxidative stress. Ascorbate has the ability to protect an organism from reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are commonly formed in organisms subject to hypoxia and ischemia associated with breath holding (Christou et al., 2003; Row et al., 2003) and as a result of fasting (Martensson, 1986; Sorensen et al., 2006). Both breath holding and fasting are key components of elephant seal life history. During reproduction and molting northern elephant seals abstain completely from food while on land and they exhibit apneas averaging six to eight minutes, and can even maintain breath holds up to 25 min that approximate mean diving durations (Blackwell and Boeuf, 1993). Breath holds may be an adaptive trait lowering the metabolism and evaporatory water loss of the animal (Lester and Costa, 2006), but which may increase the quantity of free radicals harmful to body tissues. However, it was recently determined that northern elephant seals’ tissue and systemic indices show no increases of oxidative damage over prolonged fasts (Vazquez-Medina et al., 2010), possibly due to increases in antioxidant enzyme expression and activity levels. These features may reduce the need for ascorbate in an anti-oxidant role and allow maintenance of unusually low plasma levels.

Threonate, an ascorbate break-down product, was detected using metabolomics and did not change for females but decreased over the fast for the weaned pups. This difference may reflect variation in ascorbate turnover in lactating female and developing pups. L-Threonate can improve the proliferation of osteoblasts and enhance production of mineralized nodules and collagenous protein (Fay and Verlangieri, 1991; Rowe et al., 1999). This may be indicative of bone formation and growth in the weaned pups over their developmental fast.

Total serum niacin content (nicotinic acid and nicotinamide) decreased across the lactating females’ fast, while remaining stable across the weaned pups’ fast. Niacin’s primary metabolic role is the precursor of the nicotinamide moiety of the nicotinamide nucleotide coenzymes, NAD and NADP. These function as electron carriers in a vast variety of redox reactions (Bender, 1992), including those in glycolysis and the citric acid cycle. As seen in the rat, each tissue and organ appears to synthesize its own pyridine nucleotides using the precursors niacinamide and nicotinic acid (Henderson and Gross 1979). Niacin is produced by animals from the precursor tryptophan, an essential amino acid (Machlin, 1991). There are a variety of dietary, drug, and disease factors that reduce the conversion of tryptophan to niacin (McCormick, 1988), including a decreased concentration of available free tryptophan. Tryptophan is included in the category of essential amino acids that may limit milk-protein synthesis (Mepham et al., 1976). This may be an important feature that differentiates the niacin production between fasting females and weaned pups. Females may commit available tryptophan for milk production reducing its availability for niacin synthesis, while the weaned pups do not have this obligate output decreasing their free tryptophan levels and thus niacin production. Indeed, tryptophan was measured using the metabolomics platform and was found to decrease in the lactating females and remain stable across the weaned pups’ fast, providing further evidence that lactation constrains niacin production.

Kynurenine, an intermediate in the process of niacin production from tryptophan was detected using the metabolomic analysis and was found to decrease in both age groups of elephant seals over the fast. This implies variation in the rate of production of niacin from tryptophan in the weaned pups. In pups, tryptophan remained stable, kynurenine decreased, and niacin remained stable, suggesting that niacin demand may decrease across the fast resulting in reduced commitment of tryptophan to niacin synthesis. In females, tryptophan, kynurenine, and niacin each decreased, suggesting that the decrease in the first precursor subsequently affects the production of each following metabolite. However, trigonelline, a breakdown product of nicotinic acid (Joshi and Handler, 1960), was stable in both the weaned pups and the lactating females, suggesting consistent degradation of nicotinic acid across their fasts.

Serum vitamin B12 declined significantly over the fast in both lactating females and weaned pups. Average concentrations ranged widely from 161.1 ng/l in late lactation females to 631.7 ng/l in early fasting weaned pups. Levels were similar to the range of normal human values (Zhang et al., 2003) but exceeded by up to 200% the average concentrations measured in dairy cows (Dubeski and Owens, 1993). Seal serum concentrations were 14–57% of average normal rat concentrations but overlapped with serum concentrations in vitamin B12-deprived rats (Frenkel et al., 1973). The literature reflects a wide variation in ‘normal’ versus ‘deficient’ levels in different mammalian species. Similar to pantothenic acid, vitamin B12 cannot be produced endogenously by any known animal. Its de novo synthesis is restricted to some bacteria and Archaea, including most enteric bacteria (Lawrence and Roth, 1996). Vitamin B12 is required for DNA synthesis associated with the production of new erythrocytes in animals (Koury and Ponka, 2004), such as would be expected in a developing pup. A vitamin B12 deficiency results in ineffective erythropoiesis, where red blood cells undergo apoptosis before reaching maturity (Koury and Ponka, 2004). Vitamin B12 is the best stored of all water-soluble vitamins, with enough stores to last three to five years in a normal replete human subject (Scott, 1999). In the rat, vitamin B12 was found to be stored in the liver, pancreas, and kidneys, though if the animal is saturated with the vitamin, less storage is seen in the liver and pancreas (Harte et al. 1952). However, despite this storage ability, serum B12 decreases in fasting weaned pups. This may reflect the substantial use of this vitamin in a developing animal with its requirements of new cell synthesis and during the abbreviated lactation period. This suggests the seals lack the ability to accumulate body stores and that enteric replacement either does not occur or is insufficient to keep up with demand. Serum B12 also decreases in fasting lactating females, which is not surprising given that the World Health Organization recommends that humans increase their vitamin B12 intake during lactation as it is transferred through the milk to the infant (Allen 1994).

It is interesting to note that the dual-platform analysis detected the fat-soluble vitamin alpha-tocopherol, vitamin E, in all four groups and these data are included in Table 1 for comparison. Vitamin A (retinol), which has been previously measured in northern elephant seals (C. Debier, pers. comm.), was not detected. Previous analysis of captive cetaceans, sea lions, harbor seals and walrus were not able to detect serum carotenoids (Slifka et al., 1999), a vitamin A precursor, which may be indicative of our findings as well.

4.2 Exogenous sources of non-synthesized vitamins

We hypothesize that gut microflora plays an integral part in providing certain water-soluble vitamins to its host, in this case the northern elephant seal. Current literature describing the role of gut microflora as a potential source of vitamins for animal hosts is yet unclear. Rumen bacteria can provide vitamins and other nutrients to ruminants (Bechdel et al. 1928) and intestinal or fecal bacteria provide vitamins to coprophagic rodents (Barnes and Fiala, 1958). However, in order for seals, or other non ruminant or coprophagic animals, to absorb vitamins produced by enteric bacteria, the bacteria must release vitamins into their surroundings and must be located early enough in the digestive tract for absorption to take place. While it has been documented that intestinal microflora can produce vitamins, few studies provide direct evidence of their contribution to the host organism as a vitamin source is often lacking. Only biotin (Oppel, 1942), folate (Russell, 1986), potentially vitamin B12 (Hill, 1997), and vitamin K, a fat-soluble vitamin (Conly et al., 1994) have any documented evidence indicating a potential role of gut microflora production. Gut microflora is a possible exogenous source for water-soluble vitamins in northern elephant seals; this potential source could explain how serum concentrations did not drop to undetectable amounts, or indeed how some increased, over the fasting period.

An alternate hypothesis of a vitamin source is the sand that the seals haul out on. Northern elephant seals are known to ingest sand while on shore (personal observations). The bacteria or insects in the sand may provide the water-soluble vitamins necessary for the animals, as similarly suggested for bats subsisting solely on fruit which utilize bacteria on the fruit surface for vitamin B12 (Robbins et al., 1950; van Tonder et al., 2007).

4.3 Processing limitations

The metabolomics method used was a rapid, non-targeted approach using an LC-MS and GC-MS based platform in order to identify and quantify large numbers of metabolites. It is useful for gross assessments of metabolic processes (e.g. “shotgun” analysis) and can be tailored for specific metabolites and pathways. The dual-platform process used here (LC/MS and GC/MS2) was not optimal for detecting water-soluble vitamins in elephant seal plasma. Though, it was surprising that water-soluble vitamins were undetectable using this platform in northern elephant seals, despite the detection of all water-soluble vitamins by the same platform previously in humans and rats using the same method (Llorach et al., 2009; Satake et al., 2003). However, the lack of compound detection using this method does not necessarily indicate absence of the compound. Detection of target metabolites may be masked by overlapping peaks of other compounds or their presence may be below the detection limits of the method used. The fact that the subset of water-soluble vitamins was detected and measured in the elephant seal serum with more standard methods indicates that these vitamins were not absent but were either masked by the presence of other compounds or at concentrations below the detection threshold of the platform. Indeed, while many of the vitamins existed at low concentrations compared to average human values, pantothenic acid was consistently measured at higher than average human concentrations using alternative measurement methods, yet was not detected with the dual-platform process. Detection of vitamins in the elephant seals’ plasma may have been compromised due to masking by unknown metabolites that overlap with vitamin peaks in some way that prevents detection by the platform algorithms. Over 70 unknown compounds were detected in elephant seal plasma (Crocker and Houser, unpublished data). This suggests that the number of novel compounds found in wildlife systems may limit the usefulness of the current detection algorithms and column characteristics to detect specific compounds until the number of known compounds is increased. A metabolomics approach optimized for vitamin analysis would be informative in continuing investigations, particularly since there is a potential that brominated nicotine compounds originating in the marine mammals’ diets may mask B-vitamins in chromatographic and mass spectrometry analyses (J. Newman, pers. comm).

A useful advantage to metabolomics is the ability to detect substances that may not otherwise be easily measured. For instance, in previous studies on northern elephant seals there was insufficient tryptophan present for detection in plasma (Houser and Crocker, 2004), and in milk analysis tryptophan is destroyed by acid hydrolysis (McKenzie, 1970). For this reason tryptophan was likely not measured in pinniped milk (Davis et al., 1995); however, it was detected in the present study and its relative changes were measured across the fast using metabolomics. There are potentially numerous compounds whose measurements are limited with standard techniques and the metabolomics method may be able to detect them using the small sample volumes obtainable from many wildlife systems.

5. Conclusions

The present study determined that a subset of water-soluble vitamins vary in concentration but are maintained at detectable levels in a fasting-adapted species, the northern elephant seal, over a natural, extended fast. The vitamins were largely undetected using a dual-platform metabolomics analysis involving liquid and gas chromatography and mass spectrometry. Detection of these compounds can likely be improved by identification of interfering metabolites and optimization of LC-MS and GC-MS methods for targeted compound detection.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded through grant # IOS-0818018 from the National Science Foundation and grant #1R01 HL091767 from the National Institute for Health. Additional support was provided by the American Museum of Natural History, Lerner-Gray Grant for Marine Research, and the Dr Earl H. Myers and Ethel M. Myers Oceanographic and Marine Biology Trust. We thank the field support crew and volunteers from SSU and UCSC (B. Kelso, A. Norris, M. Tift, N.M. Teutschel, and others), the Año Nuevo Rangers for logistical support, and Clairol, Inc. for providing marking solutions. All work was conducted under NMFS Marine Mammal permit #786-1463 and all procedures were approved by the Sonoma State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Cory D. Champagne, Email: champagn@biology.ucsc.edu.

Melinda A. Fowler, Email: mfowler@biology.ucsc.edu.

Dorian H. Houser, Email: biomimetica@cox.net.

Daniel E. Crocker, Email: crocker@sonoma.edu.

References

- Allen LH. Vitamin B12 metabolism and status during pregnancy, lactation and infancy. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1994;352:173–86. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-2575-6_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbano DM, Lynch JM, Bauman DE, Hartnell GF, Hintz RL, Nemeth MA. Effect of a prolonged-release formulation of N-methionyl bovine somatotropin (sometribove) on milk composition. J Dairy Sci. 1992;75:1775–1793. doi: 10.3168/jds.s0022-0302(92)77937-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes RH, Fiala G. Effects of the prevention of coprophagy in the rat. J Nutr. 1958;65:103. doi: 10.1093/jn/65.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechdel SI, Honeywell HE, Dutcher R Adams, Knutsen MH. Synthesis of vitamin B in the rumen of the cow. J Biol Chem. 1928;80:231–238. [Google Scholar]

- Bender DA. Nutritional biochemistry of the vitamins. Cambridge University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew GA, Trost CH. Temperature regulation in the Speckled Mousebird, Colius striatus. Condor. 1970;72:141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Beckman KB, Ames BN. The free radical theory. Physiol Revs. 1998;78(2):547–581. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.2.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birney EC, Jenness R, Ayaz KM. Inability of bats to synthesise L-ascorbic acid. Nature. 1976;260:626–628. doi: 10.1038/260626a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell SB, Boeuf BJ. Developmental aspects of sleep apnoea in northern elephant seals, Mirounga angustirostris. J Zool. 1993;231:437–447. [Google Scholar]

- Burns JJ. Missing step in man, monkey and guinea pig required for the biosynthesis of L-ascorbic acid. Nature. 1957;180:553. doi: 10.1038/180553a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JJ, Peyser P, Moltz A. Missing step in guinea pigs required for the biosynthesis of L-ascorbic acid. Science. 1956;124:1148. doi: 10.1126/science.124.3232.1148-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr A, Frei B. Does vitamin C act as a pro-oxidant under physiological conditions? FASEB J. 1999;13:1007. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.9.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellini MA, Rea LD. The biochemistry of natural fasting at its limits. Cell Mol Life Sci (CMLS) 1992;48:575–582. doi: 10.1007/BF01920242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri C, Chatterjee IB. L-Ascorbic acid synthesis in birds: Phylogenetic trend. Science. 1969;164:435. doi: 10.1126/science.164.3878.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherel Y, Robin JP, Le Maho Y. Physiology and biochemistry of long-term fasting in birds. Can J Zool. 1988;66:159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Christou K, Markoulis N, Moulas AN, Pastaka C, Gourgoulianis KI. Reactive oxygen metabolites (ROMs) as an index of oxidative stress in obstructive sleep apnea patients. Sleep Breathing. 2003;7:105–109. doi: 10.1007/s11325-003-0105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conly JM, Stein K, Worobetz L, Rutledge-Harding S. The contribution of vitamin K2 (menaquinones) produced by the intestinal microflora to human nutritional requirements for vitamin K. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:915–923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa DP, Le Boeuf BJ, Huntley AC, Ortiz CL. The energetics of lactation in the northern elephant seal, Mirounga angustirostris. J Zool Ser A. 1986;209:21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Crissey SD, Wells R. Serum alpha-and gamma-tocopherols, retinol, retinyl palmitate, and carotenoid concentrations in captive and free-ranging bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) Comp Biochem Physiol B. 1999;124:391–396. doi: 10.1016/s0305-0491(99)00137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker DE, Williams JD, Costa DP, Le Boeuf BJ. Maternal traits and reproductive effort in Northern elephant seals. Ecology. 2001;82:3541–3555. [Google Scholar]

- Davis TA, Nguyen HV, Costa DP, Reeds PJ. Amino acid composition of pinniped milk. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 1995;110:633–639. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(94)00162-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debier C, Kovacs KM, Lydersen C, Mignolet E, Larondelle Y. Vitamin E and vitamin A contents, fatty acid profiles, and gross composition of harp and hooded seal milk through lactation. Can J Zool. 1999;77:952–958. [Google Scholar]

- Debier C, Pomeroy PP, Baret PV, Mignolet E, Larondelle Y. Vitamin E status and the dynamics of its transfer between mother and pup during lactation in grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) Can J Zool. 2002a;80:727–737. [Google Scholar]

- Debier C, Pomeroy PP, Van Wouwe N, Mignolet E, Baret PV, Larondelle Y. Dynamics of vitamin A in grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) mothers and pups throughout lactation. Can J Zool. 2002b;80:1262–1273. [Google Scholar]

- Dhariwal KR, Hartzell WO, Levine M. Ascorbic acid and dehydroascorbic acid measurements in human plasma and serum. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54:712. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/54.4.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierenfeld ES. Vitamin E deficiency in zoo reptiles, birds, and ungulates. J Zoo Wildlife Med. 1989;20:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Dierenfeld ES. Vitamin E in exotics: Effects, evaluation and ecology. J Nutr. 1994;124:2579S–2581S. doi: 10.1093/jn/124.suppl_12.2579S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierenfeld ES. Vitamin E: Metabolism, sources, unique problems in zoo animals, and supplementation. In: Fowler ME, Miller ER, editors. Zoo and wild animal medicine. Current therapy 4. W.B. Saunders Co; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: 1999. pp. 568–571. [Google Scholar]

- Dubeski PL, Owens FN. Plasma levels of water soluble vitamins in various classes of cattle. Research report P (USA) 1993 [Google Scholar]

- Fay MJ, Verlangieri AJ. Stimulatory action of calcium L-threonate on ascorbic acid uptake by a human T-lymphoma cell line. Life Sci. 1991;49:1377. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90388-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel EP, Kitchens RL, Johnston JM. The effect of vitamin B12 deprivation on the enzymes of fatty acid synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:7540–7546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelatt TS, Arendt T, Murphy MS, Siniff DB. Baseline Levels of Selected Minerals and Fat-Soluble Vitamins in Weddell Seals (Leptonychotes weddellii) from Erebus Bay, McMurdo Sound, Antarctica. Mar Pollut Bull. 1999;38:1251–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Gey KF, Brubacher GB, Stahelin HB. Plasma levels of antioxidant vitamins in relation to ischemic heart disease and cancer. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987;45:1368. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/45.5.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halver JE, Ashley LM, Smith RR. Ascorbic acid requirements of coho salmon and rainbow trout. Trans Am Fisher Soc. 1969;98:762–771. [Google Scholar]

- Harte RA, Chow BF, Barrows L. Storage and elimination of vitamin B12 in the rat. J Nutr. 1952;49:669. doi: 10.1093/jn/49.4.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson LM, Gross CJ. Transport of niacin and niacinamide in perfused rat intestine. J Nutr. 1979;109:646–653. doi: 10.1093/jn/109.4.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill MJ. Intestinal flora and endogenous vitamin synthesis. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1997;6:S43. doi: 10.1097/00008469-199703001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper LV, Midtvedt T, Gordon JI. How host-microbial interactions shape the nutrient environment of the mammalian intestine. Annu Rev Nutr. 2002;22:283–307. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.011602.092259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houser DS, Champagne CD, Crocker DE. Lipolysis and glycerol gluconeogenesis in simultaneously fasting and lactating northern elephant seals. Am J Physiol. 2007;293:R2376. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00403.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houser DS, Crocker DE. Age, sex, and reproductive state influence free amino acid concentrations in the fasting elephant seal. Physiol Biochem Zool. 2004;77:838–846. doi: 10.1086/422055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi JG, Handler P. Biosynthesis of trigonelline. J Biol Chem. 1960;235:2981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallner A, Hartmann D, Hornig D. Steady-state turnover and body pool of ascorbic acid in man. Am J Clin Nutr. 1979;32:530. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/32.3.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland JB, Rawling JM. Niacin. In: Rucker R, Suttie JW, McCormick DM, Machlin LJ, editors. Handbook of Vitamins. M Dekker; New York: 2001. pp. 211–252. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinkauf H. The role of 4′-phosphopantetheine in the biosynthesis of fatty acids, polyketides and peptides. Biofactors. 2000;11:91–92. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520110126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koury MJ, Ponka P. New insights into erythropoiesis: The roles. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:105–131. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasiewski RC. Oxygen consumption of torpid, resting, active, and flying hummingbirds. Physiol Zool. 1963;36:122–140. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence JG, Roth JR. Evolution of coenzyme B (12) synthesis among enteric bacteria: Evidence for loss and reacquisition of a multigene complex. Genetics. 1996;142:11–24. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Boeuf BJ. Male-male competition and reproductive success in elephant seals. Am Zool. 1974;14:163–176. [Google Scholar]

- Lester CW, Costa DP. Water conservation in fasting northern elephant seals (Mirounga angustirostris) J Exp Biol. 2006;209:4283–4294. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorach R, Urpi-Sarda M, Jauregui O, Monagas M, Andres-Lacueva C. An LC-MS-Based Metabolomics Approach for Exploring Urinary Metabolome Modifications after Cocoa Consumption. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:5060–5068. doi: 10.1021/pr900470a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykkesfeldt J, Hagen TM, Vinarsky V, Ames BN. FASEB J. 1998;12:1183–1189. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.12.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machlin LJ. Handbook of vitamins. M. Dekker; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Martensson J. The effect of fasting on leukocyte and plasma glutathione and sulfur amino acid concentrations. Metabolism. 1986;35:118–121. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(86)90110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DB. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. 6. 1988. Niacin; pp. 370–375. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald BI, Crocker DE. Physiology and behavior influence lactation efficiency in northern elephant seals (Mirounga angustirostris) Physiol Biochem Zool. 2006;79:484–496. doi: 10.1086/501056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie HA. Milk Proteins: Chemistry and Molecular Biology. New York: Academic Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Mepham B, Peters AR, Davis SR. Uptake and metabolism of tryptophan by the isolated perfused guinea-pig mammary gland. Biochem J. 1976;158:659–662. doi: 10.1042/bj1580659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore LB. PhD Thesis. University of California; Berkeley: 1980. Ascorbic acid biosynthesis in certain marine mammals. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien WJ, Frerman FE. Evidence for a complex of three beta-oxidation enzymes in Escherichia coli: induction and localization. J Bacteriol. 1977;132:532–540. doi: 10.1128/jb.132.2.532-540.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppel TW. Studies of biotin metabolism in man. Part 1: The excretion of biotin in human urine. Am J Med Sci. 1942;204:856–875. [Google Scholar]

- Ottenhof HH, Ashurst JL, Whitney HM, Saldanha SA, Schmitzberger F, Gweon HS, Blundell TL, Abell C, Smith AG. Organisation of the pantothenate (vitamin B5) biosynthesis pathway in higher plants. Plant J. 2004;37:61–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reibel DK, Wyse BW, Berkich DA, Palko WM, Neely JR. Effects of diabetes and fasting on pantothenic acid metabolism in rats. Am J Physiol. 1981;240:E597–E601. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1981.240.6.E597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter J, Stinson NL, Le Boeuf BJ. Northern elephant seal development: the transition from weaning to nutritional independence. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 1978;3:337–367. [Google Scholar]

- Riedman M, Ortiz CL. Changes in milk composition during lactation in the Northern elephant seal. Physiol Zool. 1979;52:240–249. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins CT, Mathison GW. Wildlife feeding and nutrition. Academic Press; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins WJ, Hervey A, Stebbins ME. Studies on Euglena and vitamin B12. Bull Torrey Bot Club. 1950:423–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Row BW, Liu R, Xu W, Kheirandish L, Gozal D. Intermittent hypoxia is associated with oxidative stress and spatial learning deficits in the rat. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1548–53. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200209-1050OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe DJ, Ko S, Tom XM, Silverstein SJ, Richards DW. Enhanced production of mineralized nodules and collagenous proteins in vitro by calcium ascorbate supplemented with vitamin C metabolites. J Periodontol. 1999;70:992–999. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.9.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucker RB, Steinberg FM. Vitamin Requirements relationship to basal metabolic need and function. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2002;30(2):86–89. [Google Scholar]

- Rumsey SC, Levine M. Absorption, transport, and disposition of ascorbic acid in humans. J Nutr Biochem. 1998;9:116–130. [Google Scholar]

- Russell RM, Krasinski SD, Samloff IM, Jacob RA, Hartz SC, Brovender SR. Folic acid malabsorption in atrophic gastritis; Possible compensation by bacterial folate synthesis. Gastroenterology. 1986;91:1476–1482. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)90204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryter SW, Tyrrell RM. The heme synthesis and degradation pathways: role in oxidant sensitivity Heme oxygenase has both pro-and antioxidant properties. Free Radical Biol Med. 2000;28:289–309. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Said HM. Recent advances in carrier-mediated intestinal absorption of water-soluble vitamins. Annu Rev Physiol. 2004;66:419–446. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.144611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satake M, Dmochowska B, Nishikawa Y, Madaj J, Xue J, Guo Z, Reddy DV, Rinaldi PL, Monnier VM. Vitamin C metabolomic mapping in the lens with 6-deoxy-6-fluoro-ascorbic acid and high-resolution 19F-NMR spectroscopy. Invest Ophthalmol Visual Sci. 2003;44:2047. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweigert FJ. Effects of fasting and lactation on blood chemistry and urine composition in the grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) Comp Biochem Physiol A. 1993;105:353–357. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(93)90220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweigert FJ, Luppertz M, Stobo WT. Fasting and lactation effect fat-soluble vitamin A and E levels in blood and their distribution in tissue of grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) Comp Biochem Physiol A. 2002;131:901–908. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(02)00026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweigert FJ, Stobo WT, Zucker H. Ascorbic acid concentrations in serum and urine of the grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) on Sable Island. Int J Vitamin Nutr Res. 1987;57:233–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweigert FJ, Stobo WT, Zucker H. Vitamin E and fatty acids in the grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) J Comp Physiol B. 1990;159:649–654. [Google Scholar]

- Scott JM. Folate and vitamin B12. Proc Nutr Soc. 1999;58:441–448. doi: 10.1017/s0029665199000580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shochat E, Robbins CT, Parish SM, Young PB, Stephenson TR, Tamayo A. Nutritional investigations and management of captive moose. Zoo Biol. 1998;16:479–494. [Google Scholar]

- Slifka KA, Bowen PE, Stacewicz-Sapuntzakis M, Crissey SD. A survey of serum and dietary carotenoids in captive wild animals. J Nutr. 1999;129:380–390. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.2.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JL, Canham JE, Kirkland WD, Wells PA. Effect of Intralipid, amino acids, container, temperature, and duration of storage on vitamin stability in total parenteral nutrition admixtures. J Parenteral Enteral Nutr. 1998;12:478–483. doi: 10.1177/0148607188012005478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CM, Song WO. Comparative nutrition of pantothenic acid. J Nutr Biochem. 1996;7:312–321. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen M, Sanz A, Gomez J, Pamplona R, Portero-Otin M, Gredilla R, Barja G. Effects of fasting on oxidative stress in rat liver mitochondria. Free Radical Res. 2006;40:339–347. doi: 10.1080/10715760500250182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahiliani AG, Beinlich CJ. Pantothenic acid in health and disease. Vitamins Hormones. 1991;46:165. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(08)60684-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorson PH, Le Boeuf BJ. Elephant seals: population ecology, behavior, and physiology. University of California Press; Berkeley: 1994. Developmental aspects of diving in northern elephant seal pups; pp. 271–289. [Google Scholar]

- Unna K, Richards GV. Relationship between pantothenic acid requirement and age in the rat. J Nutr. 1942;23:545–553. [Google Scholar]

- van Tonder SV, Metz J, Green R. Vitamin B12 metabolism in the fruit bat (Rousettus aegyptiacus). The induction of vitamin B12 deficiency and its effect on folate levels. Br J Nutr. 2007;34:397–410. doi: 10.1017/s0007114575000463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Medina JP, Crocker DE, Forman HJ, Ortiz RM. Prolonged fasting does not increase oxidative damage or inflammation in a naturally adapted mammal, the northern elephant seal. J Exp Biol. 2010;213:2524–2530. doi: 10.1242/jeb.041335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SM, Willett WC, Selhub J, Hunter DJ, Giovannucci EL, Holmes MD, Colditz GA, Hankinson SE. Plasma folate, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, homocysteine, and risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:373–380. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.5.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]