Abstract

Objective

Although effective HIV prevention interventions have been developed for adolescents, few interventions have explored whether components of the intervention are responsible for the observed changes in behaviors post-intervention. This study examined the mediating role of partner communication frequency on African-American adolescent females’ condom use post-participation in a demonstrated efficacious HIV risk-reduction intervention.

Main Outcome Measures

Percent condom use in the past 60 days and consistent condom use in the past 6o days across the 12-month follow-up period.

Design

As part of a randomized controlled trial of African-American adolescent females (N=715), 15-21 years, seeking sexual health services, completed a computerized interview at baseline (prior to intervention) and again 6- and 12-month follow-up post-intervention participation. The interview assessed adolescents’ sexual behavior and partner communication skills, among other variables, at each time point. Using generalized estimating equation (GEE) techniques, both logistic and linear regression models were employed to test mediation over the 12-month follow-up period. Additional tests were conducted to assess the significance of the mediated models.

Results

Mediation analyses observed that partner communication frequency was a significant partial mediator of both proportion condom-protected sex acts (p =.001) and consistent condom use (p = .001).

Conclusion

Partner communication frequency, an integral component of this HIV intervention, significantly increased as a function of participating in the intervention partially explaining the change in condom use observed 12-months post-intervention. Understanding what intervention components are associated with behavior change is important for future intervention development.

Keywords: partner communication frequency, adolescents, condom use

In the United States, adolescents are disproportionately affected by sexual transmitted infections (STIs) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). Among adolescents, girls have particularly high rates of STIs. Recent findings from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicate that, overall, one in four girls in the U.S. has an STI; with nearly half (48%) of African-American girls detected with an STI (Forhan et al., 2008). To combat the STI epidemic among adolescent females, several efficacious STI/HIV prevention interventions have been developed for adolescent females, including African-American adolescent females (Choi et al., 2008; DiClemente et al., 2004; DiClemente et al., 2009; Ehrhardt et al., 2002; Jemmott, Jemmott, Braverman, & Fong, 2005; Jemmott, Jemmott, & O’Leary, 2007; Sales, Milhausen, & DiClemente, 2006;).

Typically, STI/HIV prevention interventions targeting adolescent females focus on increasing participants’ knowledge regarding STI/HIV transmission dynamics, condom use self-efficacy, barriers to condom use, attitudes toward condom use, intentions to use condoms, condom use skills as well as facilitating partner communication about sex and condom use (Choi et al, 2008; DiClemente et al., 2004; DiClemente et al., 2009; Ehrhardt et al. 2002; Jemmott et al, 2005; Jemmott et al, 2007). A central tenet of most interventions designed for adolescent females is the focus on improving partner communication about sex and condom use with male sex partners (Choi et al., 2008; DiClemente et al., 2004; DiClemente et al., 2009; Jemmott et al., 2005; Stanton, Ricardo, Galbraith, Feigelman, & Kaljee, 1996). The Theory of Gender and Power (TGP), a prominent theory guiding the development of two demonstrated effective interventions for African-American adolescent girls (DiClemente et al., 2004; DiClemente et al., 2009), suggests that power differentials favoring men pose health risks for women. Specifically, social norms may preclude young women from engaging in frequent communication about condom use, partner’s sexual history, prevention of pregnancy, and/or STI/HIV prevention. Thus, communication skill-building is an integral component included in most efficacious HIV interventions (Rotheram-Borus et al., 2009). Specific to females, a recent meta-analysis of HIV prevention interventions for African-American women concluded that intervention efficacy was greatest in studies that specifically targeted African-American females, used gender- and/or culturally-specific materials, addressed empowerment issues, provided skills training in condom use and negotiation of safer sex, and used role-playing to teach negotiation skills (Crepaz et, 2009). Thus, a strong emphasis on communication and negotiation strategies may be particularly salient for African-American females.

Some strategies employed in enhancing partner communication in efficacious STI/HIV prevention interventions include teaching assertive communication, participating in role-plays to practice assertive communication and negotiating risk reduction strategies with partners (i.e. condom use, STI testing, abstinence) as well as establishing and communicating sexual health boundaries to sex partners. Participants often practice communicating their sexual health choice with health educators representing male sex partners. Health educators provide constructive feedback to participants, who may practice additional communication skills building exercises. Practice is continued until participants achieve proficiency.

Although efficacious STI/HIV prevention interventions have been developed for adolescents, few have statistically explored whether components taught in the intervention (e.g., partner communication skills) are responsible for behavioral changes observed post-intervention (e.g., increase condom use). Among the few STI/HIV prevention interventions which have conducted mediation analyses to ascertain which components of the program are accounting for behavioral change, one program designed for college students (male and females) identified condom-use intentions as a mediator (Sanderson & Jemmott, 1996), one for clinic-attendees (males and females) identified self-efficacy as a mediator for females only (Fishbein et al., 2001), and one STI/HIV prevention program for African-American adult women found that self-efficacy for condom use significantly mediated the interventions effect on condom use at last sex (O’Leary, Jemmott, & Jemmott, 2008). Although all of these STI/HIV prevention programs included women and components specific to communication, partner communication was not explored as a mediator. Thus, the extent to which increases in ability to communicate with sexual partners about sexually-related topics accounts for increased protective behaviors (i.e., condom use) post-intervention has not been examined empirically.

HORIZONS, a CDC-defined Tier I evidence-based STI/HIV prevention intervention for African-American adolescent females, increased psychosocial mediators including partner communication frequency, STI/HIV prevention knowledge, and condom use self-efficacy as well as condom use over the 12-months follow-up period post-intervention (DiClemente et al., 2009). However, whether increases in psychosocial mediators explained the observed increase in condom use was not explored. Based on theoretical and empirical rationale, and to fill a gap in the prevention literature, the primary objective of the present study was to assess the mediating role of partner communication frequency on condom use among this sample of African-American adolescent females participating in the HORIZONS intervention. Identifying which components of an intervention’s curriculum are significantly associated with increased protective behaviors post-intervention is a critical step for future STI/HIV intervention development.

METHODS

Participants

From March 2002 to August 2004 African-American adolescent females, 15-21 years of age (mean=17.8 years, sd=1.7), were recruited from three sexual health clinics in downtown Atlanta, Georgia, providing sexual health services to predominantly inner-city adolescents. These clinics are the primary source of sexual health services for young, inner-city African-American females. A young African-American woman recruiter approached adolescents in the clinic waiting area, described the study, solicited participation, and assessed eligibility. Eligibility criteria included self-identifying as African-American, 15-21 years of age, and reporting vaginal intercourse in the past 60 days. Adolescents who were married, currently pregnant, or attempting to become pregnant, were excluded from the study. Adolescents returned to the clinic to complete informed consent procedures, baseline assessments, and be randomized to trial conditions. Written informed consent was obtained from all adolescents with parental consent waived for those younger than 18 due to the confidential nature of clinic services. Of the eligible adolescents, 84.4% (N=715) enrolled in the study, completed baseline assessments and were randomized to study conditions. A total of 86% (n=298) returned at the 6-month follow up for the intervention condition while 86% (n=314) returned for the control condition. At the 12-month follow up, 83% (n=289) returned for the intervention condition and 86% (n=316) returned for the control condition. Participants were compensated $50 for travel and childcare to attend intervention sessions and complete assessments. The Emory University Institutional Review Board approved all study protocols.

Study Procedures

Study Design

The study used a two-arm randomized controlled trial design. Assignment to study conditions was implemented subsequent to baseline assessment using concealment of allocation procedures, defined by protocol, and compliant with published recommendations (Schulz, 1995; Schulz, Chalmers, Hayes, & Altman, 1995; Schulz & Grimes, 2002). Prior to enrollment investigators used a computer algorithm to generate a random allocation sequence to generate group assignments which were sealed in opaque envelopes and used to execute randomization.

Intervention Methods

Development of this gender- and culturally appropriate intervention is described in detail in DiClemente et al. (2009). The intervention (HORIZONS) consisted of two 4-hour group STI/HIV prevention sessions. These sessions were each co-facilitated by trained African-American women health educators, and implemented on two consecutive Saturdays with, on average, 8 participants attending each session. The intervention was based on Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1994), the Theory of Gender and Power (Wingood & DiClemente, 2000; Wingood & DiClemente, 2002), and previously published interventions for adolescent females seeking clinical services (DiClemente et al, 2004). Intervention sessions were interactive, fostered a sense of cultural and gender pride, and emphasized diverse factors contributing to adolescents’ STI/HIV risk including individual, relational, and socio-cultural factors. Special emphasis was placed on enhancing individual participants’ sexual communication and condom negotiation skills with male sex partners. Specifically, the intervention taught assertive communication skills, practice of assertive communication, and negotiating risk reduction strategies with male sex partners through role plays (i.e. condom use, STI testing, abstinence) as well as communication of sexual health boundaries to male sex partners. Also, participants practiced communicating their sexual health choice to sexual partners through role-plays with health educators. Another intervention activity focused on helping girls generate a repertoire of verbal response or “comebacks” with male sex partners who are resistant to condom use.

The enhanced usual care comparison condition was a 1-hour group session, implemented by an African-American woman health educator, consisting of a culturally and gender-appropriate STD/HIV prevention video, a question-and-answer session, and a group discussion (as detailed in DiClemente et al., 2009).

Summary of Intervention Efficacy Findings

DiClemente et al. (2009) analyzed and reported on the efficacy of the HORIZONS intervention in improving condom use across 12-month follow up period. To summarize, results suggested that over the 12-month follow-up, adolescents in the intervention reported a higher proportion of condom-protected sex acts in the 60 days preceding follow-up assessments (Mean Difference = 10.84, 95% CI 5.27-16.42; p =.0001). Adolescents in the intervention were also more likely to report consistent condom use in the 60 days preceding follow-up assessments (RR=1. 41, 95% CI 1.09, 1.80; p =.01). Finally, intervention effects were observed for psychosocial mediators. Specifically, intervention participants showed increased partner communication frequency over the 12-month period post intervention participation (Mean Difference = 0.60, 95% CI 0.01-1.20; p =.04), increased STI/HIV prevention knowledge (Mean Difference = 0.40, 95% CI 0.18-0.62; p < .001), and increased condom use self-efficacy (Mean Difference = 1.46, 95% CI 0.79-2.14; p < .001).

Data Collection

Data collection occurred at baseline, 6- and 12-months following completion of the two session group-implemented STI/HIV intervention, and consisted of an ACASI interview and self-collected vaginal swabs to assess STIs. The ACASI technology enhances data accuracy, increases participants’ comfort answering sexually explicit questions, and eliminates low literacy as a potential barrier (Turner et al., 1998; Zimmerman, Atwood & Cupp, 2006). The ACASI assessed sociodemographics, sexual history, and psychosocial constructs associated with STD/HIV–preventive behaviors. Sexual behaviors were assessed for the 60 days preceding assessments. Several strategies were used to enhance accuracy and validity of self-reported sexual behaviors, included reporting behaviors over relatively brief intervals (McFarlane & St. Lawerence, 1999), and using the Timeline Followback method, an effective method to facilitate retrospective recall of STD/ HIV sexual behaviors (Weinhardt et al., 1998). To enhance confidentiality, participants were informed that code numbers would be used on all records. To minimize potential assessment bias, ACASI monitors were blind to participants’ condition assignment. See DiClemente et al. (2009) for a detailed description of STD data collection procedures.

Outcome Measures

Behavioral Outcome Measures

The primary behavioral outcomes were the proportion of condom-protected sex acts and consistent condom use in the 60 days prior to 6- and 12-month assessments. Proportion of condom-protected sex acts was calculated as the number of times a condom was used during vaginal intercourse, divided by the total number of vaginal intercourse occasions. Consistent condom use was calculated by dichotomizing the proportion of condom-protected sex acts variable into consistent users (condom use 100% of the time) and inconsistent users (condom use less than 100% of the time).

Mediating Variable

Preliminary analyses were conducted to explore whether the three psychosocial mediators which increased as a function of intervention participation (STI/HIV prevention knowledge, partner communication frequency, and condom use self-efficacy) were significantly related to the behavioral outcome variables. STI/HIV prevention knowledge and condom use-self-efficacy were not significant related to either behavioral outcome variable, so the remaining analyses presented in this paper pertain only to the mediating role of partner communication frequency.

Partner communication frequency was assessed at baseline, and again at 6- and 12-month follow-up assessments by a 5-item scale that assesses adolescents’ frequency of communicating with male sex partners (Milhausen et al., 2007). Specifically, the 5 items were as follows: “In the past 60 days, how many times have you talked to your partner about.…1) condom use; 2) your partner’s sexual history; 3) preventing pregnancy; 4) protecting yourself from STIs; and 5) protecting yourself for HIV. Each item required a response based on a four-point Likert-type scale (never to a lot/seven or more times). Higher values indicate more frequent sexual communication (baseline Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83).

Planned Analysis

Our analytic plan followed the guidelines of Baron and Kenny (1986). Because we were interested in determining whether STI/HIV-associated risk behaviors were indirectly related to the HORIZONS intervention (i.e., operating through empowering women to communicate safer sexual practices with male sex partners), we tested for a significant indirect association through partner communication frequency. To do so, we estimated a series of generalized estimating equation (GEE) models to account for repeated correlated observations collected at post-baseline assessments, controlling for baseline values in each model. Specifically, to assess mediation effects for the entire 12-month follow-up period, logistic (for the dichotomous outcome of consistent condom use) and linear (for the continuous outcome of proportion condom use) GEE regression models controlled for repeated within subject measurements. These models allow for a differential number of repeated observations of study participants over the longitudinal course of a study. Initially, we estimated two separate regressions in which we regressed the partner communication frequency variable on the HORIZONS intervention variable. Next, we estimated a series of regressions in which we regressed the sexual behavior outcome (i.e., proportion of condom protected sex acts) on the HORIZONS intervention.1 Finally, we estimated a series of regressions in which we regressed the sexual behavioral outcomes on the HORIZONS intervention and the partner communication variable. For mediation to occur, significant associations must be observed for each of the first two regression models while in the third set of regressions, the effect of the HORIZONS intervention on both outcomes must be less than observed in the second set of regressions.

Using both Sobel’s test (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West & Sheets, 2002), and Goodman’s (1) test we also evaluated the significance of the indirect association between the HORIZONS intervention and condom use measures through the partner communication variable. The Sobel test, and the Goodman (1) version of the Sobel test are both appropriate tests for linear and logistic analyses (MacKinnon & Dwyer, 1993). Furthermore, following the recommendations of Shrout and Bolger (2002) to enhance confidence in the mediation effects for both linear and logistic models, we calculated the strength of mediation based on the effect ratio (indirect effect over the total effect). Analyses were performed using Stata version 11.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

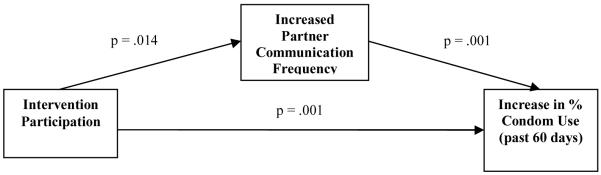

HORIZONS intervention participants, relative to comparison group participants, had significantly higher partner communication frequency scores (11.7 versus 10.9; p=0.04), higher proportion of condom-protected sex acts in the past 60 days (60.7% versus 51.2%; p=0.034), and more consistent condom use in the 60 days prior to assessments (40.9% versus 30.8%; p=0.020) over the entire 12-month follow-up period. Mediation analyses established that partner communication frequency was a significant partial mediator of both condom use measures: proportion condom-protected sex acts (exp (b) = 1.01, S.E. = .003, p =.001; Sobel = 2.18, p = .029; Goodman = 2.14, p = .032; See Figure 1) and consistent condom use (OR = .074, 95% CI, .016 - .131, p = .001; Sobel = 2.05, p = .041; Goodman = 2.00, p = .046; See Figure 2). For the proportion condom-protected sex acts, mediation analysis identified a total effect of the HORIZONS intervention of 11.7%. Mediation analysis determined that a relatively small portion, 8.26%, of the total effect was mediated through partner communication frequency. The ratio of indirect to direct effect was 0.09. For the consistent condom use, mediation analysis identified a total effect of the HORIZONS intervention odds ratio of 1.41 of which a relatively small portion, 12.24%, was mediated through partner communication frequency. The ratio of indirect to direct effect was 0.14.

Figure 1.

GEE linear regression mediation of percent condom use over a 12-month follow-up by partner communication frequency.

Note: Sobel mediation test coefficient = 2.18, p = .029; Goodman mediation test coefficient = 2.15, p = .032.

Figure 2.

GEE logistic regression mediation of consistent condom use over a 12-month follow-up by partner communication frequency.

Note: Sobel mediation test coefficient = 2.05, p = .041; Goodman mediation test coefficient = 2.00, p = .046.

DISCUSSION

Findings indicate that the increase in HORIZONS participants’ partner communication frequency across the 12-month follow-up period post-intervention partially explains the increase in two key measures of condom use among these young women in the same time frame. Thus, the intervention, which includes multiple activities designed to increase partner sexual communication frequency, positively impacted young women’s partner communication behavior which, in turn, increased their condom use with male sex partners.

Although the increase in partner communication frequency was significantly associated with the observed increase in condom use, partner communication frequency was not solely accountable for participants’ increased condom use as it only explains a portion of the effect. Thus, not surprisingly, other aspects of the intervention may also account for the increase in condom use. Condom use is a complex behavior, further complicated by its dyadic nature, making it unreasonable to assume that one factor alone (i.e., partner communication frequency) would independently account for the increase in condom use. Instead, it is more likely that the synergy of programmatic activities, focusing on enhancing adolescents’ prevention knowledge, changing their attitudes and perceived peer norms regarding the adoption of HIV/STI preventive behaviors, and their behavioral skills, including partner communication frequency and condom use skills, may collectively better account for the observed increase in condom use post-intervention.

That partner communication frequency played a significant role in the observed increased of condom use is encouraging and reinforces the utility of emphasizing activities promoting more frequent sexual communication with male sex partners in STI/HIV prevention interventions for young women. According to Social Cognitive Theory, simply performing a behavior on multiple occasions (i.e., more frequent partner sexual communication) can make an individual feel more self-efficacious to perform that behavior in the future (Bandura, 2004). Furthermore, according to the Theory of Gender and Power (Wingood & DiClemente, 2002), the act of frequently engaging a sexual partner in communication about sexually-protective behaviors may empower young women to insist on their partner’s use of condoms during sex.

Although efficacious STI/HIV prevention interventions have increased condom use among adolescent female participants, very few have systematically explored which of the theoretically-derived conceptual components of the intervention might be responsible for the observed intervention effects (i.e., increase in condom use). The few that have conducted mediation analyses have identified condom use intentions and condom use self-efficacy as mediators (Fishbein et al, 2001; O’Leary et al., 2008; Sanderson & Jemmott, 1996), but these studies did not explicitly examine the potential mediating role of partner communication on condom use, which for empirical and theoretical reasons may be especially instrumental in increasing condom use among young women as women have to negotiate condom use regardless of their intentions or self-efficacy to correctly use condoms. Indeed, although the HORIZONS intervention increased STI/HIV prevention knowledge and self-efficacy to use condoms, these factors were not significantly associated with condom use post-intervention. Thus, simply increasing STI knowledge or self-efficacy to correctly use a condom alone may not be sufficient for behavior change among young women as they offer no mechanism by which the gains can be translated into actual condom use, a partner-dependent behavior.

Knowing which components of an intervention’s curriculum are significantly associated with increased protective behaviors is important for future STI/HIV intervention development. Whether they are newly designed or adaptations of past programs, interventionists will benefit from knowing the specific topic areas/conceptual components that are critical to include in prevention programming, especially programs targeting specific groups or populations. This is particularly important as many STI/HIV interventions, in order to be disseminated in communities, will need to be less time-intensive to accommodate participants’ schedules and attention spans. Furthermore, having a clear understanding of efficacious intervention components is especially beneficial for resource-constrained communities not capable of implementing lengthy multi-session interventions. Thus, knowing the core elements to include for behavior change becomes vital when time and resources are scarce.

Limitations

The present study is not without limitations. The findings may not be applicable to African-American adolescent females with different sociodemographic characteristics or risk profiles, as this was a high-risk, sexually active population recruited from sexual health clinics. The fact that these young women were seeking services for sexual health related issues may further differentiate them from young women who may not feel capable of seeking sexual health services. Furthermore, the findings may not be applicable to adolescent females from other ethnic/racial groups or to adolescent males. Additionally, the findings may not be generalizable to other STI/HIV interventions, even those including partner communication components. However, a strength of the HORIZONS intervention is that the HIV prevention messages were tailored to be gender and culturally specific to ensure its appropriateness and acceptability for young African-American women. Reviews of effective HIV prevention programs highlight that the most effective programs are those that are tailored towards specific audiences and not for a “general population” (Crepaz et al, 2009; Rotheram-Borus et al, 2009).

Conclusion

Effective STI/HIV prevention programs, capable of being widely disseminated, are urgently needed for African-American young women as they remain disproportionately burdened by STIs and HIV. Despite the fact that efficacious STI/HIV interventions have been developed for African-American adolescent females, the mechanisms underlying program efficacy are rarely explored. Identifying components responsible for driving intervention efficacy, such as partner communication frequency, has the potential to benefit future intervention efforts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by a grant, number K01 MH085506, from the National Institute of Mental Health to the first author, and grant number R01 MH061210, from the National Institute of Mental Health to the third author, and with additional support from the grant P30 A1050409 from the Emory Center for AIDS Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/hea.

The first two sets of regressions were all statistically significant and indicated that the Horizons intervention was associated with the communication variable and with the sexual outcome measures, thus conforming to the Baron and Kenny criteria for mediation analyses. These regression results are available in DiClemente et al. (2009).

REFERENCES

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory and exercise of control over HIV infection. In: DiClemente RJ, Peterson J, editors. Preventing AIDS: Theories and Methods of Behavioral Interventions. Plenum Publishing Corp; New York, NY: 1994. pp. 25–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Health Promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior. 2004;31(2):143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC . Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance, 2008. Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta, GA: US: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Choi K-H, Hoff C, Gregorich SE, Grinstead O, Gomez C, Hussey W. The efficacy of female condom skills training in HIV risk reduction among women: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:1841–1848. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, Marshall KJ, Aupont LW, Jacobs ED, Mizuno Y, Kay LS, et al. The efficacy of HIV/STI behavioral interventions for African American females in the United States: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;19(2):190–203. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.139519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Harrington KF, Lang DL, Davies SL, Hook EW, III, et al. Efficacy of an HIV prevention intervention for African American adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292(2):171–179. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Rose ES, Sales JM, Lang DL, Caliendo AM, et al. Efficacy of STD/HIV sexual risk-reduction intervention for African American adolescent females seeking sexual health services: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163(12):1112–1121. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt AA, Exner TM, Hoffman S, Silberman I, Leu C-S, Miller S, et al. A gender-specific HIV/STD risk reduction intervention for women in a health care setting: Short- and long-term results of a randomized clinical trial. AIDS Care. 2002;14:147–161. doi: 10.1080/09540120220104677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Hennessy M, Kamb M, Bolan GA, Hoxworth T, Iatesta M, et al. Using intervention theory to model factos influencing behavior change: Project Respect. Evaluation and the Health Professions. 2001;24:363–384. doi: 10.1177/01632780122034966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forhan S, Gottlieb SL, Sternberg MR, Xu F, Datta SD, Berman S. Prevalence of Sexually Transmitted Infections and Bacterial Vaginosis among Female Adolescents in the United States: Data from the National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (NHANES), 2003-2004; Paper presented at the National STD Prevention Conference; Chicago, IL. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jemmott J,B, Jemmott LS, Braverman PK, Fong GT. HIV/STD risk reduction interventions for African American and Latino adolescent girls at an adolescent medicine clinic: A randomized control trial. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159:440–449. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.5.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB, III, O’Leary A. Effects on sexual risk behavior and STD rate of brief HIV/STD prevention interventions for African American women in primary care settings. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1034–1040. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.020271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Evaluation Review. 1993;17:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane M, St. Lawrence JS. Adolescents’ recall of sexual behavior: consistency of self-report and the effects of variation in recall duration. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;25(3):199–206. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milhausen RR, Sales JM, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Salazar LF, Crosby RA. Validation of a partner communication scale for use in HIV prevention intervention. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention in Children and Youth. 2007;8(1):11–33. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary A, Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB. Mediation analysis of an effective sexual risk-reduction intervention for women: The importance of self-efficacy. Health Psychology. 2008;27(2, Suppl):S180–S184. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Flannery D, Rice E, Adamson DM, Ingram B. Common factors in effective HIV prevention programs. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13:399–408. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9464-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales JM, Milhausen RR, DiClemente RJ. A decade in review: Building on the experiences of past adolescent STI/HIV interventions to optimize future prevention efforts. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2006;82:431–436. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.018002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson CA, Jemmott JB. Moderation and mediation of HIV-prevention interventions: Relationship status, intentions, and condom use among college students. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1996;26(23):2076–2099. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz KF. Subverting randomization in controlled trials. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;274:1456–1458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Empirical evidence of bias: Dimensions of methodological quality associated with treatment effects in controlled trials. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;273:408–412. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Blinding in randomized trials: Hiding who got what. Lancet. 2002;359:696–700. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07816-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and non experimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton BF, Li X, Ricardo I, Galbraith J, Feigelman S, Kaljee L. A randomized, controlled effectiveness trial of an AIDS prevention program for low-income African-American youths. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 1996;150:363–372. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290029004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers S, Lindberg L, Pleck J, Sonenstein F. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Maisto S, Carey KB, Cohen MM, Wickramasinghe SM. Reliability of the Timeline Follow-back Sexual Behavior interview. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1998;20(1):25–30. doi: 10.1007/BF02893805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Application of the Theory of Gender and Power to examine HIV related exposures, risk factors and effective interventions for women. Health Education and Behavior. 2000;27:539–565. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. The theory of gender and power: A social structural theory for guiding the design and implementation of public health interventions to reduce women’s risk of HIV. In: DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler M, editors. Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research: Strategies for Enhancing Public Health. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2002. pp. 313–347. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman RS, Atwood KA, Cupp PK. Improving the validity of self-reports for sensitive behaviors. In: Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ, Salazar LF, editors. Research Methods in Health Promotion. Jossey-Bass, Inc; San Francisco, CA: 2006. pp. 260–288. [Google Scholar]