Abstract

Informed consent is essential to ethical research and is requisite to participation in clinical research. Yet most hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) informed consent forms (ICFs) are written at reading levels that are above the ability of the average person in the US. The recent development of ICF templates by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health and the National Heart Blood and Lung Instituthas not resulted in increased patient comprehension of information. Barriers to creating Easy-to-Read ICFs that meet US federal requirements and pass Institutional Review Board (IRB) review are the result of multiple interconnected factors. The Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN) formed an ad hoc review team to address concerns regarding the overall readability and length of ICFs used for BMT CTN trials. This paper summarizes recommendations of the review team for the development and formatting of Easy-to-Read ICFs for HCT multicenter clinical trials, the most novel of which is the use of a two-column layout. These recommendations intend to guide the ICF writing process, simplify local IRB review of the ICF, enhance patient comprehension and improve patient satisfaction. The BMT CTN plans to evaluate the impact of the Easy-to-Read format compared to the traditional format on the informed consent process.

Keywords: informed consent, health literacy, hematopoietic stem cell transplant, clinical trials, readability, legibility

INTRODUCTION

Informed consent is essential to ethical research and is a required element of participation in clinical research. The process is an ongoing and dynamic exchange of information between investigators and potential participants, guided by a written informed consent form (ICF). Informed consent is meant to ensure that patients understand the study purpose, research procedures, risks and potential benefits, and the voluntary nature of participation so they can make informed choices.1, 2 The written ICF summarizes the clinical study and the rights of research participants, provides a resource for patients and their families, and serves as documentation of the patient’s agreement to participate in the study.

In response to concerns that ICFs were becoming too long, complicated and difficult to understand, the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Comprehensive Working Group on Informed Consent in Cancer Clinical Trials issued its “Recommendations for the Development of Informed Consent Documents for Cancer Clinical Trials.”1 These guidelines were accompanied by an ICF template that included all of the basic elements of informed consent, document formatting and sample plain language (hereafter referred to as Easy-to-Read) recommendations, as required by federal law (Table 1).3

Table 1.

Federally Required Elements of Informed Consent*

| 1. A statement that the study involves research, an explanation of the purposes of the research and the expected duration of the subject’s participation, a description of the procedures to be followed, and identification of any procedures which are experimental; |

| 2. A description of any reasonably foreseeable risks or discomforts to the subject; |

| 3. A description of any benefits to the subject or to others which may reasonably be expected from the research; |

| 4. A disclosure of appropriate alternative procedures or courses of treatment, if any, that might be advantageous to the subject; |

| 5. A statement describing the extent, if any, to which confidentiality of records identifying the subject will be maintained; |

| 6. For research involving more than minimal risk, an explanation as to whether any compensation and an explanation as to whether any medical treatments are available if injury occurs and, if so, what they consist of, or where further information may be obtained; |

| 7. An explanation of whom to contact for answers to pertinent questions about the research and research subjects’ rights, and whom to contact in the event of a research-related injury to the subject; and |

| 8. A statement that participation is voluntary, refusal to participate will involve no penalty or loss of benefits to which the subject is otherwise entitled and the subject may discontinue participation at any time without penalty or loss of benefits to which the subject is otherwise entitled. |

Taken from the US Department of Health And Human Services Code of Federal Regulations for the Protection of Human Subjects in Research 45 CFR 116.46 (http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/understanding/simplification-of-informed-consent-docs/page4#appendix2).

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Heart Blood and Lung Institute (NHLBI) also produced templates to facilitate the use of Easy-to-Read ICFs in cancer clinical trials. The respective templates vary in the degree to which each agency incorporates the NCI’s general recommendations for readability (outline, language and tone) and processability (incorporation of explicit information, layout, mental images, and context clues).4 This inconsistency of interpretation makes it challenging for investigators to create Easy-to-Read ICFs that also meet federal requirements and pass Institutional Review Board (IRB) review.

Informed Consent Challenges in Transplant

Decisions regarding complex and potentially curative procedures such as hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) can be particularly challenging for patients.5 Stress caused by disease severity, the urgency to move ahead with treatment, and persistent cognitive effects of chemotherapy and radiation conditioning regimens may reduce patients’ ability to fully take in and comprehend the information provided to them.6–10 It is important to address these factors during the informed consent process, as the literature shows that fully informed patients are more likely to adhere to the treatment regimen.11–12

The literature also shows that shortening the length of the consent form can improve patient understanding and retention.4, 13–14 In the NCI, NIH, and NHLBI literature and ICF templates, formal recommendations on ICF length are not addressed. We do note that length is quite challenging and in a HCT multicenter clinical trial, required information regarding patient involvement, risks and side effects can add great length to a consent form. Inconsistency among IRBs regarding the required study information and formatting can also contribute to excessively long and complicated ICFs.15 The priority should be given to legibility and readability recommendations over length, as these factors can reduce the reader’s cognitive effort and improve their ability to locate important information within the document.

Easy-to-Read Informed Consent Forms

Individuals at all literacy levels prefer and better understand ICFs written in plain language.16–17 The use of readability and processability suggestions from the literature has been associated with improved health outcomes and acceptance of information, reduces overall anxiety in patients, and makes the consent document less frightening to the study participants.4,18–19 A study by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group found that an Easy-to-Read ICF was associated with higher patient satisfaction compared to a standard ICF format.16 In addition, higher satisfaction was positively associated with greater comprehension among patients.16

We present recommendations for developing Easy-to-Read ICFs with a two-column design for HCT clinical trials including readability guidelines to enhance patient comprehension and satisfaction with the consent process. These recommendations are intended to: (1) simplify the process for ICF development by investigators who write consent forms1; (2) reduce the burden associated with review of the ICF by local IRBs which oversee research projects and consent forms at their institutions20; (3) enhance the research participant’s understanding of the consent form1; and (4) improve patient satisfaction with the informed consent process16.

METHODS

The Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN) is a national clinical trials network focusing on issues in HCT. It is funded through two divisions at the NIH: the NHLBI and the NCI. The BMT CTN Data Coordinating Center (DCC) is a collaboration of the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR), the National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP) and the EMMES Corporation, a contract research organization. The BMT CTN formed an ad hoc Informed Consent Form Review Team (Team) to address concerns regarding overall readability and document length of ICFs used for BMT CTN trials. The Team included members of the DCC, members of the NMDP Patient Services department, and experts in health services research and biomedical ethics.

Areas of expertise among Team members included IRB participation, research ethics, clinical research, health services research, medically underserved populations, health education, and patient advocacy. The objective was to (1) evaluate the current format of BMT CTN informed consent forms for the inclusion of federally-required basic elements for informed consent and evidence-based readability and processability recommendations; (2) develop an Easy-to-Read ICF template that reflects all required basic elements and readability recommendations for BMT CTN clinical trials; and (3) issue a formal recommendation for the development of future BMT CTN ICFs.

The Team performed a literature search on the topics of adult literacy, patient education and readability, informed consent, and pediatric assent development; sources included the NIH Office of Human Subjects Research, the US Department of Health and Human Services, the US Department of Education, the Institute of Medicine and national peer-reviewed journals. Sample clinical trial consent and assent forms from cancer treatment clinics were also reviewed for completeness, readability, length and format.

Based on this review, the Team created an Easy-to-Read Informed Consent Form Fact Sheet outlining the rationale for a proposed novel format. The Fact Sheet describes five elements of Recommended Readability Guidelines for Informed Consent Forms and was used to update proposed ICFs for the BMT CTN. The updated ICFs incorporate the recommended format, which features a two-column layout, reorganized information sections, and increased spacing between lines of text. The Team further refined and adapted the new ICFs through a series of discussions with BMT CTN investigators, NMDP’s Patient Services, and The EMMES Corporation Clinical Trial Support Services. Feedback from research sites and IRBs was also considered in the process. The recommendations do not address specialized issues related to genetic testing, bio-specimen banking or the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Regulations.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The following recommendations provide guidance for Easy-to-Read ICFs for HCT multicenter clinical trials. Five elements related to readability and processability are addressed including: layout, organization, typography, plain language, and “what to avoid” (Table 2). ICF writing teams should first reference the NCI consent template as the primary document source.21 Second, writers should create a standardized outline incorporating the federally required elements of informed consent and emphasize plain language appropriate for HCT clinical trials (Table 1). Last, the writing team should implement an annual review process to evaluate the most recent versions of consent templates from the NIH, NCI, and NHLBI to ensure BMT CTN ICFs reflect best practices.

Table 2.

Recommended Readability Guidelines for Informed Consent Forms

| Layout | |

|

|

|

| |

| Organization | |

|

|

|

| |

| Typography | |

|

|

|

| |

| Plain Language | |

|

|

|

| |

| Avoid | |

|

|

Layout

Text layout is an important design factor that affects legibility, reading performance and information processing, including the search for specific information within a text.22–23 It generally refers to the presentation of information and graphics on the page, including spacing between lines (leading) and the width of columns of text.23 The lines of text should be no more than 5 inches running horizontally across a page or 30–50 characters and spaces.23–24 Recommended leading for body text is approximately 120% of the point size (1–2 points larger).25 In addition, the left margins should be justified and the right margins should be left ragged. It also is important to include a generous amount of white space in the document to reduce the appearance of clutter, make it appear more inviting, and to give the reader’s eyes a rest between sections of text.23 Addressing legibility concerns within a text can minimize stress and improve reading performance.22

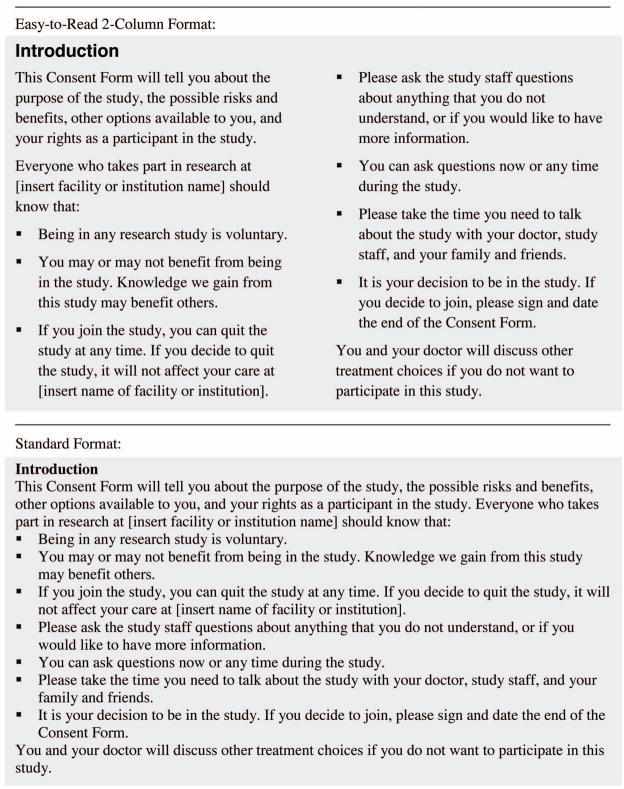

The ability to locate information within a text is an essential consideration in the design and layout of ICFs. A strategy for locating information in text is the use of a two-column format. Compared to reading comprehension, locating information in text requires a series of distinct cognitive operations that are dependent on text features. 26 A two-column text layout is central to the process of locating information within a text because readers can more effectively identify target words.22, 24 The moderate line widths utilized in this format shorten the “jump” the eye must make from the end of one line to the beginning of the next.22–23 Two-column formatting also helps readers keep their place as they read and has been established as more familiar and generally easier to process.4, 22–23 Newspapers and magazines have used this format for years because it makes the document more readable.27 The two-column format is a simple solution for adhering to line length guidelines while simultaneously shortening the overall length of the document (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Easy-to-Read 2-Column Format Versus Standard Format for Informed Consent Forms

Organization

Proper organization improves document readability and processability. Important information, such as the purpose of the study and what is expected of the reader, should be near the beginning of the document.17, 28 Writers should present information in sections (often referred to as “chunking”), introduced by headers that clearly identify and describe each of the elements to be discussed, even if the sections repeat information.29 Headers should be simple and spaced close to the related text. Limit lists to three to five items, as few people can remember more than seven independent items.17

Typography

To improve readability, the Serif fonts (e.g. Garamond, Times New Roman) should be used for body text. The Serif fonts are generally easier to read because the tiny strokes (serifs) help the reader’s eyes track horizontally across the line of text.30 The Sans Serif fonts (e.g. Arial, Verdana) are appropriate for titles and headers. These fonts contrast with the font of the body text and help the title and header stand out on the page.30 Printed material should not have more than two font styles on any one page.23 To ensure maximum readability, use a text size of 11–13 points; most readers can read 12-point text.30 Text size varies among fonts even when the same point size is used.

Plain Language

Plain language is communication your audience can understand the first time they read or hear it.31 Examples of plain language for HCT specialized terminology are provided in Table 3. There are several methods for developing written materials in plain language. First, write at an eighth-grade reading level or lower.4, 14, 17–18, 23, 27, 32 Many word processing programs now offer the option to show readability statistics including the Flesch-Kincaid Reading Level and the proportion of passive sentences. Second, use the active voice, or “write the way we talk” (Table 3). Third, repeat the message(s) in the document. This gives the reader multiple opportunities to understand the message.17, 23 Fourth, use familiar words, provide sufficient information and organize the content well.23 Fifth, include graphics to help make complex information easier to understand.21 If the audience is racially and/or ethnically diverse, use culturally relevant images that are meaningful to them.30 When the text is easy to read (written at an eighth grade level or lower) and is coupled with simple graphics, a stronger message is created because each element helps explain the other. However, graphics should only be used when they can be reproduced well and are clear.23 Visuals that draw the reader’s eye to important points are an effective form of emphasis.33 For example, arrows directing the reader to the next page or a graphic placed alongside core messages help the reader navigate the document. Sixth, use short, simple and direct sentences. Last, break up longer sentences into bulleted lists to increase white space.

Table 3.

Plain Language Examples of Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Specialized Terminology

| Specialized Term | Plain Language Example |

|---|---|

| Hematopoietic cells | Hematopoietic cells are cells that can make blood. These cells are collected from bone marrow, the bloodstream (peripheral blood) or the umbilical cord after a baby is born. Transplant using hematopoietic cells is called hematopoietic cell transplant, or HCT. |

| Allogeneic stem cell transplant | An allogeneic transplant uses blood-making cells from a family member or an unrelated donor. The collected cells will replace the abnormal blood cells in the patient. |

| Autologous stem cell transplant | An autologous transplant uses stem cells, or blood-making cells, collected from the patient. The collected cells will replace the abnormal blood cells in the patient. |

| Conditioning regimen | A conditioning regimen is a treatment that uses a combination of chemotherapy and sometimes radiation to destroy cancer cells and help donor cells start to grow in your bone marrow. Depending on the combination used, each treatment (or “conditioning regimen”) can have a different intensity or strength. |

| Myeloablative | High intensity treatment is a combination of chemotherapy that uses stronger or higher amounts of drugs and sometimes radiation. This is also called “myeloablative conditioning.” |

| Prognosis | An idea of how your disease might develop, with or without treatment. |

| Remission | Remission is a stage when you do not have any signs or symptoms of disease after treatment. |

| Graft-versus-Host Disease | Graft-versus-Host Disease (GVHD) is a medical condition that can become very serious and may cause death. GVHD is a common development after allogeneic stem cell transplant. It happens when the donor cells attack and damage your tissues after transplant. |

Avoid

The reading cues provided by word shapes are lost with stylized text formats.17 Such formats include: large blocks of print (too few paragraph breaks), text that is underlined or italicized, or text in all capitals. Avoid the unnecessary use of professional jargon, acronyms, symbols and abbreviations. Shorter words (less than three syllables) are generally easier to understand. If there is not an appropriate substitute for an unfamiliar term, follow it with an example using common words.17

Examples of BMT CTN HCT multicenter clinical trial ICFs in traditional and Easy-to-Read formats are available online (S1, S2).

DISCUSSION

Patients’ ability to understand most ICFs and participate in the decision-making process is impacted by their level of health literacy.34 In Healthy People 2010, the US Department of Health and Human Services defined health literacy as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”35 The National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NALS) found that 21% of US adults are functionally illiterate and an additional 27% have marginal literacy.36–37 Federal requirements state that information must be understandable to participants, yet studies indicate that most oncology ICFs are complicated to the point that the average person in the US is likely to find them difficult to read.38

Despite efforts to improve the process of informed consent in cancer research, a significant proportion of study participants do not fully comprehend the research to which they consented.39 Problems with written ICFs persist due to increasingly complicated protocols that are often randomized to complex treatment arms.40 Additional challenges are presented by HCT multicenter clinical trials in which the procedures, therapies and possible toxicities are difficult to explain at the “layman” level.23, 40 Many IRB-approved ICFs are written at a twelfth grade reading level or higher, although the average reading ability of US adults is at or below the eighth-grade level.36, 40–41

Well-designed consents foster the use and retention of meaningful information and enhance the quality of patient-physician interactions.1, 4, 13–14, 16 Easy-to-Read ICFs ensure that decisions about medical care are made in a collaborative manner between patient and physician.42 The patient-physician interaction plays a key role in clinical trial enrollment. A study by Wright et al. found that discussions of consent issues between patients and clinical research associates positively correlated with the patient’s decision to enter a clinical trial.43

Study teams should proactively approach IRBs or IRB offices to collaborate on effecting changes in ICFs. IRBs could approve template, layout, and other suggestions in this paper prior to individual IRB meetings for more general aspects of the ICF, while study specific language (specific risks, benefits, goals of studies, etc.) would be written on a study-by-study basis. Following this process would reduce the burden on IRBs while simultaneously increasing consistency and quality of consent materials. For study teams, greater uniformity is achieved and they need not worry about individual IRB boards requiring different changes to the same text. Finally, all would benefit, including research participants, from an ICF that more effectively conveys information regarding the study.

The Readability Guidelines for ICFs suggested in this paper will lower the reading level, shorten the document length, and improve patient satisfaction in HCT consent documents. The BMT CTN is working to identify opportunities for educational interventions among protocol staff and IRB members to facilitate the use of Easy-to-Read ICFs in clinical trials. Educational interventions may include: samples of both traditional and Easy-to-Read ICFs, examples of plain language for specialized terminology, and references from the literature on improving document readability. BMT CTN plans to conduct a randomized, controlled trial (RCT) to: 1) identify barriers to implementing an Easy-to-Read ICF in multicenter clinical trials, 2) evaluate the effectiveness of the two-column ICF format, and 3) determine whether the Easy-to-Read ICF lessens anxiety during the informed consent process. Incorporating current readability and processability recommendations from the literature will help to improve ICFs until RCT results are available.4, 18–19

Future research initiatives should evaluate the quality of translated Easy-to-Read ICFs. Investigators may also want to consider multi-media approaches to improving the informed consent process. However, a written Easy-to-Read ICF serves as an informational resource and documents the patient’s agreement to participate in the study. There is a need for the development of templates for consent to genetic testing and/or the collection of bio-specimens. At this time, the NCI provides suggested language for bio-specimen and genetic testing ICFs; however, no templates exist for this area of research at the NCI, NIH or NHLBI.

Supplementary Material

BMT CTN Traditional Informed Consent Form Example (S1) p. 23–44

BMT CTN Easy-to-Read Informed Consent Form Example (S2) p. 45–65

Acknowledgments

The Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network is supported in part by grant #U01HL069294 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Comprehensive Working Group on Informed Consent in Cancer Clinical Trials for the National Cancer Institute: Recommendations for the Development of Informed Consent Documents for Cancer Clinical Trials. [Accessed 3/19/2010];NCI, NIH Publication No. 98–4355. 1998 Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/understanding/simplification-of-informed-consent-docs.

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services Office for Human Research Protections. OHRP Informed Consent Frequently Asked Questions. 2008 November; Retrieved July 1, 2010, from http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/informconsfaq.html.

- 3.45 CFR 46. 116: Protection of Human Subjects; Revised 6/18/1991.

- 4.Tait A, Voepel-Lewis T, Malviya S, Philipson S. Improving the readability and processability of a pediatric informed consent document: Effect on parents’ understanding. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:347–352. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.4.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox K. Informed consent and decision-making: patients’ experiences of the process of recruitment to phases I and II anti-cancer drug trials. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;46(1):31–38. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Witte T, Hermans J, Vossen J, et al. Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for patients with myelodysplastic syndromes and secondary acute myeloid leukaemias: a report on behalf of the Chronic Leukaemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Br J Haematol. 2000;110(3):620–630. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foltz A, Sullivan J. Reading level, learning presentation preference, and desire for information among cancer patients. J Cancer Educ. 1996;11(1):32–38. doi: 10.1080/08858199609528389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Socie G, Stone JV, Wingard JR, et al. Long-term survival and late deaths after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(1):14. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907013410103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens PE, Pletsch PK. Ethical issues of informed consent: mothers’ experiences enrolling their children in bone marrow transplantation research. Cancer Nurs. 2002;25(2):81–87. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200204000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiss B, Hart G, McGee DE, D’Estelle S. Health status of illiterate adults: relation between literacy and health status among persons with low literacy skills. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1992;5:257–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singer DA, Donnelly MB, Messerschmidt GL. Informed consent for bone marrow transplantation: identification of relevant information by referring physicians. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1990;6(6):431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Wagner C, Semmler C, Good A, Wardle J. Health literacy and self-efficacy for participating in colorectal cancer screening: The role of information processing. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75(3):352–357. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beardsley E, Jefford M, Mileshkin L. Longer consent forms for clinical trials compromise patient understanding: so why are they lengthening? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(9):13–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.3341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis T, Holcombe R, Berkel H, et al. Informed consent for clinical trials: a comparative study of standard versus simplified forms. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(9):668–674. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.9.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berger O, Gronberg BH, Sand K, Kaasa S, Loge JH. The length of consent documents in oncological trials is doubled in twenty years. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(2):379. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coyne CA, Xu R, Raich P, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an easy-to-read informed consent statement for clinical trial participation: a study of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(5):836–842. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doak C, Doak L, Root J. Teaching Patients with Low Literacy Skills. Philadelphia: JB Lippencott Company; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis T, Williams M, Marin E, Parker RM, Glass J. Health literacy and cancer communication. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52(3):134–149. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.52.3.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute for Healthcare Advancement. Health Literacy: Bridging Research and Practice. La Habra, CA: Institute for Healthcare Advancement; 2009. [Accessed 8/1/09.]. Available at: http://www.iha4health.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burman WJ, Reves RR, Cohn DL, Schooley RT. Breaking the camel’s back: multicenter clinical trials and local institutional review boards. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(2):152–157. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-2-200101160-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simplification of Informed Consent Documents. National Cancer Institute, US National Institutes of Health; [Accessed 9/10/2010.]. Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/understanding/simplification-of-informed-consent-docs/page3. [Google Scholar]

- 22.dos Santos Lonsdale M, Dyson M, Raynolds L. Reading in examination-type situations: the effects of text layout on performance. J Research Reading. 2006;29(4):433–453. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayer G, Villaire M. Health Literacy in Primary Care: A Clinician’s Guide. 1. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foster J. A study of the legibility of one- and two-column layouts for BPS publications. Bull Br Psychol Soc. 1970;23:113–114. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ralph J. A geriatric visual concern: the need for publishing guidelines. J Am Optom Assoc. 1982;53(1):43–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guthrie J, Kirsch I. Distinctions between reading comprehension and locating information in text. J Edu Psychol. 1987;79(3):220–227. [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Maine CDC Institutional Review Board. [Accessed 8/12/2009.];Suggestions on Improving the Readability of a Consent Form. Available at: http://www.maine.gov/dhhs/boh/IRB/IRB%20intranet/readguid.pdf.

- 28.Hartley J. Designing instructional and informational text. In: Jonassen DH, editor. Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. pp. 917–947. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guidelines for Writing Informed Consent Documents. National Institutes of Health, Office of Human Subjects Research; 2006. [Accessed 8/12/2009.]. Available at: http://ohsr.od.nih.gov/info/sheet6.html. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Southern Institute on Children and Families. The Health Literacy Style Manual. Columbia, SC: Covering Kids and Families; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31.The Plain Language Action and Information Network (PLAIN) [Accessed 3/8/2010.];What is plain language? Available at: http://www.plainlanguage.gov/whatisPL/index.cfm.

- 32.Hammerschmidt D, Keane M. Institutional Review Board (IRB) review lacks impact on readability of consent forms for research. Am J Med Sci. 1992;304(6):348–351. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199212000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. [Accessed 8/16/2009.];Clear and Simple: Developing Effective Print Materials for Low-Literate Readers. NCI, NIH Publication No. 95–3594, 1994. Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/aboutnci/oc/clear-and-simple/page1.

- 34.Raich PC, Plomer KD, Coyne CA. Literacy, comprehension, and informed consent in clinical research. Cancer Invest. 2001;19(4):437–445. doi: 10.1081/cnv-100103137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2000. [Accessed 8/12/09.]. Available at: http://www.health.gov/communication/literacy/quickguide/factsbasic.htm#one. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirsch I, Jungeblut A, Jenkins L, Kolstad A. Adult Literacy in America: A First Look at the Results of the National Adult Literacy Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, US Dept. of Education; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, et al. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, US Dept. of Education; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharp SM. Consent documents for oncology trials: does anybody read these things? Am J Clin Oncol. 2004;27(6):570–575. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000135925.83221.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flory J, Emanuel E. Interventions to improve research participants’ understanding in informed consent for research: a systematic review. JAMA. 2004;292(13):1593–1601. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.13.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grossman SA, Piantadosi S, Covahey C. Are informed consent forms that describe clinical oncology research protocols readable by most patients and their families? J Clin Oncol. 1994;12(10):2211–2215. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.10.2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silverman H, Hull SC, Sugarman J. Variability among institutional review boards’ decisions within the context of a multicenter trial. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(2):235. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200102000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Appelbaum PS, Lidz CW, Meisel A. Informed Consent: Legal Theory and Clinical Practice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wright J, Whelan T, Schiff S, et al. Why cancer patients enter randomized clinical trials: exploring the factors that influence their decision. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(21):4312–4318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

BMT CTN Traditional Informed Consent Form Example (S1) p. 23–44

BMT CTN Easy-to-Read Informed Consent Form Example (S2) p. 45–65